Abstract

Molecular catch bonds are ubiquitous in biology and essential for processes like leukocyte extravasion1 and cellular mechanosensing2. Unlike normal (slip) bonds, catch bonds strengthen under tension. The current paradigm is that this feature provides ’strength-on-demand’3, thus enabling cells to increase rigidity under stress1,4,5,6. However, catch bonds are often weaker than slip bonds because they have cryptic binding sites that are usually buried7,8. Here we show that catch bonds render reconstituted cytoskeletal actin networks stronger than slip bonds, even though the individual bonds are weaker. Simulations show that slip bonds remain trapped in stress-free areas, whereas weak binding allows catch bonds to mitigate crack initiation by moving to high-tension areas. This ‘dissociation-on-demand’ explains how cells combine mechanical strength with the adaptability required for shape change, and is relevant to diseases where catch bonding is compromised7,9, including focal segmental glomerulosclerosis10 caused by the α-actinin-4 mutant studied here. We surmise that catch bonds are key to creating life-like materials.

Here we exploit the actin-binding protein α-actinin-4 and its K225E point mutant, associated with the heritable disease kidney focal segmental glomerulosclerosis type 110, to identify the role of catch bonds in the mechanical properties of actin networks. Actin is a key determinant of cell mechanics, together with other cytoskeletal proteins. To isolate the role of catch bonds in actin mechanics, we reconstituted actin networks from purified components. We first characterized the binding affinity of the two protein variants for actin filaments in the absence of mechanical load. Co-sedimentation of the crosslinkers with actin filaments revealed that the K255E mutant has a nearly 10-fold higher affinity (15.55 ± 0.04 μM-1) for actin than wild type α-actinin-4 (1.95 ± 0.04 μM-1, Figure 1e and Extended Data Figure 1). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching measurements of crosslinker dissociation confirmed that wild type α-actinin-4 has a substantially lower bond lifetime than the mutant (Extended Data Figure 2), consistent with prior measurements in cells11.

Figure 1. Single-molecule measurements of actin filament binding reveal catch bonding for wild type α-actinin-4 but not the K255E mutant.

a, Each monomer of the dimeric crosslinker α-actinin-4 (red) has two weak binding sites for actin filaments (green) and one strong binding site (white) that needs to be activated by force for the wild type (WT) protein (red), whereas it is always exposed for the K255E mutant (blue). The force-induced shape transition is exaggerated for clarity. b, The lifetime of a catch bond first rises and then decreases with increasing force, while a constitutively active variant that acts as a regular slip bond shows a decreasing lifetime. The schematic shows a simplified limit, in which the catch and slip bond lifetimes become equal at high force. c, Single-molecule force spectroscopy assay, where a crosslinker-coated and an actin-coated bead are trapped using optical tweezers. d, Example trace illustrating the approach-and-retract protocol to establish bonds between the crosslinkers and actin filaments (top panel). An increase in the force while retracting indicates the presence of a tether (green), and the lifetime is measured until the instant the tether breaks (ti, tj, bottom panel). e, Actin association affinity ka of α-actinin-4 (red) and K255E (blue) measured in a co-sedimentation assay. Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error extracted from fitting the fraction of bound crosslinkers at 6 independent samples with different actin concentrations assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Extended Data Figure 1a-c). f, Average lifetime of tethers as a function of applied force, as measured by optical tweezers (see panel d). The lifetime of wild type α-actinin-4 (red) initially rises, peaks at a force of ~4 pN, and then decreases, as expected for a catch bond. The K255E mutant shows an overall decreasing lifetime, typical of a slip bond. Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error. Numbers of data points per bin in Figure 1f are: 14, 13, 12, 18, 6, 4, 4 for WT, and 3, 9, 9, 10, 13, 13, 10, 7 for the K255E mutant. Affinity and force spectroscopy data were obtained at 25 °C.

Based on crystal structures, it has previously been speculated that force activates a cryptic actin-binding site of α-actinin-4, thus behaving like a catch bond12. It was furthermore proposed that the cryptic actin binding site is constitutively exposed by the K255E point mutation, increasing the binding affinity of α-actinin-4 but also abrogating its catch bond behavior (Figure 1a, b)11,13. To directly test this idea, we tethered single α-actinin-4 molecules to polystyrene beads via DNA handles, and probed their binding to fluorescently tagged actin filaments, which fully coated another set of beads (Figure 1c). Using optical tweezers, we trapped an α-actinin-4-coated bead and an actin-coated bead, as verified by simultaneous fluorescence imaging, (Extended Data Figure 3b) and performed bead approach-retraction cycles. When we detected a force increase upon retraction, which indicated a binding event, we subsequently maintained the tether at a pre-set force until the force suddenly dropped to zero and the beads separated (Figure 1d), indicating forced crosslinker unbinding. The bond lifetime for the wild type α-actinin-4 showed a load dependence consistent with catch bond behavior: short lifetimes at low loads, peaking at an intermediate load (around 4 pN), and decreasing for further increasing loads (Figure 1f, red data). By contrast, the K255E point mutant showed slip bond behavior, with a lifetime higher than the wild type variant at low loads, consistent with the biochemical data (Figure 1e, and Extended Data Figure 1 and 2), and monotonically decreasing for increasing tensions (Figure 1f, blue data). The single-molecule data provide direct proof of earlier speculations that α-actinin-4 forms weak catch bonds whilst the K255E point mutant forms strong slip bonds11,13.

The observation that catch bonds are weaker than slip bonds raises the question whether they also form weaker networks. To test the strength of crosslinked actin networks, we co-polymerized actin with either crosslinker between the cone and plate of a rheometer and linearly increased the mechanical load (shear stress) in time by rotating the cone until the network ruptured, while recording the resulting network deformation (strain, Figure 2a). We first dissected the effect of the bond lifetime on network rupturing by measuring networks crosslinked by the mutant slip bonds at either high or low temperature (25°C for low bond lifetime and 10°C for high bond lifetime). The high temperature was chosen such that K255E had the same bond lifetime as the wild type α-actinin-4 actin network at low temperature (Extended Data Figure 4a-d). Consistent with intuition, we find that weaker linkers yield weaker networks (rupture stresses of 6.5 ± 0.5 Pa and 8.1 ± 1.1 Pa at 25 °C and 10 °C, respectively, Figure 2b). At the same time, the weaker networks are more deformable, meaning that they reach a much larger strain before rupturing (129 ± 10% and 63 ± 4% at 25 °C and 10 °C, respectively, Figure 2b). So how about the catch bonds, which have a lower bond lifetime than the mutant slip bonds at the same temperature but exhibit a different load dependence? Strikingly, networks crosslinked by the α-actinin-4 catch bonds at 10 °C were more deformable than either of the slip bond networks (rupture strain of 221 ± 16%) yet also stronger (rupture stress of 24.5 ± 2.7 Pa, Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Catch bonds simultaneously enhance the mechanical strength and the deformability of cytoskeletal actin networks.

a, Scheme of rheology experiments to characterize actin network mechanics. We measure the shear deformation γ of actin networks crosslinked either with α-actinin-4 or with K255E by linearly increasing the shear stress σ in time with a stress rate of 2.0 mPa/s. b, Representative examples of the shear strain γ as function of the shear stress σ for α-actinin-4 (red), K255E (blue), both at 10 °C, and for K255E at an elevated temperature (25°C, dark blue) where its lifetime matches that of wild type α-actinin-4 at 10°C (Extended Data Figure 4c-d). The white circles indicate the rupture points (see Supplementary Methods). The top panel shows the average rupture stress and the right panel the average rupture strain for each condition. Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error (N=4 independent samples for each condition). c, Actin networks are modelled as 1D arrays of reversible linkers that stochastically exchange between a bound and freely diffusing state. The applied load (σ) linearly increases in time and is shared over all bound linkers proportionally to the distance to the nearest neighbors li. d, The total number of unbinding events per bond nu as a function of applied stress (see Supplementary Methods), showing the same crosslinker dependence as the rheology experiments. The Data in the top and right panel are presented as mean values +/- the standard error (N=100 independent simulations for each condition).

How can catch bonds escape the trade-off between strength and deformability that is inherent in normal (slip) bonds? To answer this question, we developed a minimal model where the crosslinked actin network was represented by an array of N reversible bonds sharing a load σ (Figure 2c, see Supplementary Methods and detailed explanation in the SI). We assumed nearest-neighbor load sharing (Supplementary Methods Eq. 2), as it provides a simple yet accurate way to model crack initiation in viscoelastic materials, which is the rate-limiting step of rupturing (Extended Data Figure 5)14,15. We used idealized Bell-Evans force-dependent unbinding kinetics to capture the catch or slip bond behavior (Figure 1b, Supplementary Methods Eq. 1), and allowed for unbound linkers to rebind at a random new location16. This bond turnover is proportional to network deformability (see SI). We chose our parameters in accordance to the force spectroscopy and biochemical data, such that the catch bonds are weaker at low force (see Supplementary Table 1 for all parameters). Strikingly, the simulations also showed that weak catch bonds collectively make networks that are stronger than slip bond networks (rupturing at nearly twice the stress, Figure 2d), yet more deformable (with 10-fold more bond turnovers before rupturing, Figure 2d). This difference persisted when including partially bound crosslinkers to account for the fact that α-actinin is a homodimer (Extended Data Figure 6d, Supplementary Note 1). The model also confirmed the experimental observation that simply decreasing the bond lifetime while retaining a slip bond response results in weaker networks (Figure 2d).

To identify the mechanism behind the remarkable mechanical advantage of catch bonds, we quantified the steady state distributions of the load per individual crosslinker (Figure 3a). At a given macroscopic load, the average force per bond was only slightly higher for the catch bonds compared to the slip bonds (respectively 0.241 ± 0.003 and 0.223 ± 0.001, mean ± standard error). However, the distribution of forces for catch bonds was much narrower than for the slip bonds, meaning that slip bond networks contain substantially more bonds that bear high loads (Figure 3a) and therefore fracture more readily. As bond load and bond-bond distance are directly proportional in our simple model (Supplementary Methods Eq. 2), this means slip bond networks exhibit larger gaps than catch bond networks. To test whether suppression of large gaps by catch bonding is a potential mechanism to prevent crack initiation, we ablated adjacent bonds and simulated the network stability as a function of the gap size. Notably, gaps twice as large were required to rupture networks of catch bonds compared to slip bonds (Extended Data Figure 5d). These findings suggest that catch bonds ‘dissociate-on-demand’ from low-stress areas thanks to their shorter lifetime at lower loads, freeing up crosslinkers that can rebind in high-stress areas and hence prevent the initiation of cracks (Figure 3b). Simulations also showed that the mechanical advantage of catch bonds over slip bonds was indeed lost when the catch bonds are immobile (Extended Data Figure 6c).

Figure 3. Minimal model suggest that catch bonds strengthen networks by redistributing to tense areas.

a, The distribution of forces per bond f measured at steady state in 1D simulations. The average bond force (vertical lines, 0.241 ± 0.003 and 0.223 ± 0.001, mean ± standard error) is larger for catch bonds (red) than for slip bonds (blue), but the force distribution of the former is much narrower: bonds carrying normalized forces higher than 1 are more than two orders of magnitude more likely for slip than for catch bonds. b, Self-assembly mechanism explaining the mechanical advantage of weak catch bonds (red, left) over strong slip bonds (blue, right). The thickness of the colored arrows codes for the on- and off-rate of the linkers. 1. Catch bond linkers in low tension areas rapidly unbind, increasing the pool of unbound linkers (2). As a result, there is increased binding everywhere in the network (3), at the expense of only the linkers in low tension areas. The net result is that the force distribution homogenizes, preventing crack initiation. By contrast, slip bonds preferentially localize in low-stress areas.

As crosslinker rebinding is important for the mechanism, we next investigated how the mechanical advantage of catch bonding depends on the ratio between crosslinker binding and unbinding rate. We find that in case of slow binding compared to unbinding, slip bonds provide stronger networks than catch bonds (Extended Data Figure 7a): in this regime, catch bond-induced dissociation strongly decreases the bound fraction, thereby weakening the network. By contrast, when binding is fast compared to unbinding, increased dissociation barely affects the bound fraction as crosslinkers rapidly rebind. Therefore, catch bonds provide stronger networks only when the binding rate is fast compared to the unbinding rate (Extended Data Figure 7a), which is the relevant situation for real actin networks crosslinked by α-actinin-4 (Extended Data Figure 1d) and also appears to be the relevant regime in cells given the strong co-localization of α-actinin-4 with the actin cytoskeleton8,11. To experimentally test these predictions, we performed rupturing experiments on actin networks where we tuned the unbinding rate by changing the temperature. Consistent with the model’s prediction, decreasing the temperature from 25 °C to 10 °C (and hence decreasing the unbinding rate) resulted in steeper increases in the rupture stress for the α-actinin-4 catch bonds than for the K255E slip bonds (Extended Data Figure 7b).

Our model predicts that catch bonding triggered by network stress is key to explain the increased strength of the wild α-actinin-4 crosslinkers. To test whether the loads exerted on the network were indeed sufficient to activate the catch bonds, we determined the crosslinker unbinding time from the network mechanics at different levels of shear stress, using a small oscillatory stress at different frequencies to measure the viscoelastic response time. This assay provides the characteristic network relaxation time, which is directly proportional to the crosslinker unbinding time (Supplementary Note 2)17. The network relaxation time in case of wild type α-actinin-4 crosslinkers increased with increasing shear stress, followed by a decrease at the highest stress levels, consistent with catch bonding (Extended Data Figure 4h). For the K255E crosslinkers, the stress relaxation time was larger than for the catch bonds at low shear stress but similar at high stress (Extended Data Figure 4h). These findings confirm the single molecule data (Figure 1f) at the network level and show that macroscopically applied stresses above 5 Pa indeed activate strong binding for wild type α-actinin-4, whereas the K255E mutant behaves like a conventional slip bond, being strongest at small loads.

Our experiments and 1D simulations together suggest that catch bonds strengthen actin networks by being able to redistribute to tense regions under load. However, these simple simulations lack an explicit polymer network. We therefore decided to probe bond redistribution by realistic 3D-simulations of actin networks18–21 (Figure 4a, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Table 2). These simulations contain explicit filaments and capture the main features of actin network mechanics while allowing for microscopic force measurements that are not experimentally tractable. We simulated strain ramps on networks connected by either catch or slip bonds (Supplementary Video 1, Figure 4b and Extended Data Figure 8a). It is well-known that stress is mostly carried by a small subset of tense filaments in actin networks20, so we analyzed how effective catch and slip bond crosslinkers were at connecting these tense filaments. Strikingly, we found that catch bonds formed up to 80% more links between pairs of highly tensed filaments than slip bonds (Figure 4c, Extended Data Figure 8e-f), despite binding less on average (Extended Data Figure 8c). Furthermore, this preferential binding to stressed actin filaments increased as the bulk shear stress was raised (Supplementary Video 2). These findings directly verify the catch bond redistribution to high-stress areas as predicted by the 1D model.

Figure 4. Detailed actin network simulations confirm catch bond network strengthening via dissociation-on-demand.

a, Schematic of actin network simulations. Actin filaments (F-actins, cyan) are simplified into serially connected cylindrical segments. Crosslinkers are simplified into two arm segments connected by elastic hinges. Yellow: crosslinkers binding to two F-actins to form a functional crosslink. Red: inactive crosslinkers bound to one F-actin. Bending (κb) and extensional (κs) stiffnesses govern the mechanical behaviors of these segments (see Supplementary Table 2). b, Schematic showing how the network (30×30×1 μm) is deformed by linearly increasing shear strain by fixing the bottom of the network and displacing the top in the +x direction. c, Ratio of catch and slip-bond crosslinkers in color as a function of the tension in the two filaments they connect, derived from two simulations at 10 Pa stress (one with catch bonds and one with slip bonds). Color scale: percentage relative enrichment of catch bonds over slip bonds bound between a pair of actin filaments for varying tension on filament 1 (vertical axis) and on filament 2 (horizontal axis). Specifically, the color scale is defined as when ncatch > nslip (shown in red) and when nslip > ncatch (shown in blue) where ncatch and nslip are the number of resp. catch and slip bond linkers connecting two filaments. Compression is reported as negative tension. 10x10 tension bins are used, and the distribution was smoothed using bicubic interpolation. The tension spacing is chosen such that each bin includes 10% of the filaments (Extended Data Figure 8b), is the same for the x- and y-axis and is only displayed on the y-axis for esthetic reasons. The simulations show that catch bonding linkers preferentially connect two high-tension filaments whereas slip bonding linkers are enriched on low-tension filament pairs.

Our work reveals a new role for catch bonds in the cytoskeleton, namely to simultaneously increase its mechanical strength and its deformability. Contrary to the common intuition that catch bonds provide strength-on-demand, our model shows that they make strong networks because dissociation-on-demand enables them to redistribute to tense areas and thus postpone crack initiation. This mechanism likely also applies to living cells, as α-actinin-4 is mobile inside the actin cortex and was recently observed to increase its bond lifetime upon mechanical stress in living cells22. Force sensors for α-actinin 4 analogous to those available for other proteins23 could be developed and resolved with single-molecule resolution to directly visualize the load-dependent redistribution for catch and slip bonds in both reconstituted actin networks and living cells.

Our findings also suggest a molecular mechanism to explain the low mechanical stability of kidney cells in patients afflicted by heritable disease kidney focal segmental glomerulosclerosis type 1, where α-actinin-4 carries the point mutation K255E and is known to cause podocyte fragility10,24. A similar mechanism may possibly apply to other diseases where loss of catch bonding leads to tissue failure, such as Von Willebrand disease 2B7,9. In this work we focused on the implications of catch bonds for network strength, but the generality of our model implies that this same mechanism can also apply to catch bonds in cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesions1,2, as dissociation-on-demand reduces friction whilst simultaneously minimizing the risk of complete cell detachment. Therefore, our results suggest that catch bonds are widespread in the cytoskeleton and at cellular interfaces to break this deformability/strength trade-off, and it would be interesting to investigate force-dependent binding of more crosslinkers and adhesins, such as filamin and IgSF CAMs. Finally, our findings offer a cell-inspired route to create hydrogel materials that are strong yet sufficiently deformable for applications in regenerative medicine25. Recent years have seen a surge of theoretical and experimental work in the polymer community to create tougher hydrogels, for instance by the inclusion of stiff elements into the hydrogel26–28. However, these approaches have largely focused on preventing crack propagation, rather than crack initiation. Preventing crack propagation works well to absorb a finite amount of mechanical energy but offers limited advantage in case of constant stress. For future work, it would be interesting to combine mitigation strategies for both crack initiation and propagation. Synthetic analogues of catch bonds have recently been discovered and provide an excellent starting point towards highly dynamic yet strong biomimetic materials29,30.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. High-speed co-sedimentation measurements of the affinity of α-actinin-4 (WT) and K255E crosslinkers for actin filaments.

a, b, supernatant resulting from a high-speed centrifugation of a mixture of actin filaments and crosslinkers was run on an SDS-page gel. The bands on the bottom show the α-actinin-4 (WT) or K255E (resp. a and b, molecular weight ~ 100 kDa in both cases), while the bands on the top show actin (42 kDa). Each labeled column contained a different actin concentration as indicated. Some lanes were kept empty as spacers. The crosslinker concentration was fixed at 0.1 μM. A single measurement was performed per condition. c, The fraction of bound crosslinkers, as determined from the co-sedimentation assay, as a function of the actin concentration was fit to the equation: where Ka is the affinity of the crosslinker. d, Consistent with the high affinity of both crosslinkers, SDS-page gels of supernatant resulting from a high-speed centrifugation of a crosslinked actin network at the concentration used in all our experiments (48 μM actin together with 0.48 μM crosslinker) does not show any measurable fraction of unbound crosslinkers. A single measurement was performed per condition.

Extended Data Figure 2. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching measurements reveal that α-actinin-4 crosslinkers are more dynamic than the K255E mutant.

Example fluorescence recovery curves of α-actinin-4 (a) and K255E (b) in the presence of 48 μM actin show full recovery of both proteins after photobleaching at time t=0, but with different timescales. The solid lines represent exponential fits to the data (see Supplementary Methods). c, Average recovery time for α-actinin-4 (red) and for K255E (blue), with the standard error on basis of 5 measurements of different locations within the same sample per condition. Measurements were performed at 25 °C.

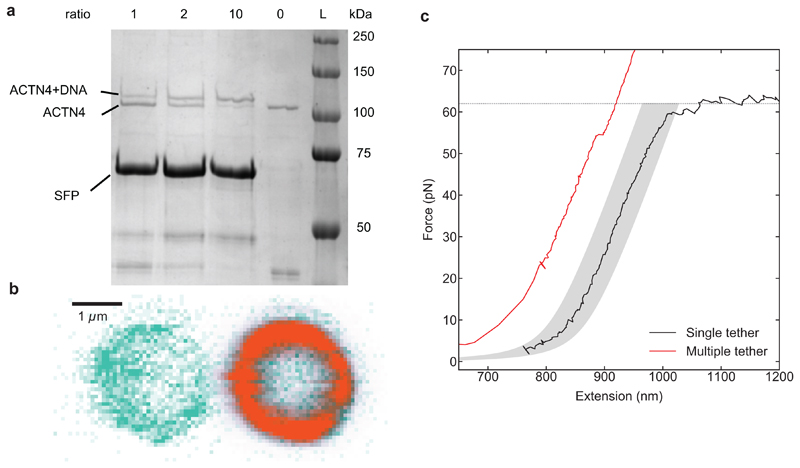

Extended Data Figure 3. Generation and classification of α-actinin-4/actin tethers.

a, DNA was coupled to α-actinin-4 (WT or K255E) using an SFP synthase-mediated reaction. Because α-actinin-4 is a homodimer, the yBBr tag used for coupling is present in both monomers. To favour DNA attachment to only one monomer, we performed coupling reactions with several DNA titrations, and the coupling yields were quantified using SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. The DNA:α-actinin-4 molar ratios are indicated above each lane. At a molar ratio of 1:1, most of the α-actinin-4 is uncoupled, i.e. most dimers will be either not coupled or have only one monomer coupled to DNA. A single measurement was performed per condition. b, Concurrent confocal fluorescence images of a trapped bead coated with α-actinin-4 (left) and a trapped bead coated with actin filaments (right). The bead’s autofluorescence is depicted in green, and the fluorescent emission of Alexa Fluor 647-tagged actin is depicted in orange. In total, 36 images have been taken of 4 independent samples. This image shows representative examples. c, Force-extension curves showing the overstretching regime of a single dsDNA tether (black), and a case where the two beads are linked by multiple tethers, which yields a shorter contour length and higher forces without unzipping (red). Variability in bead radii and actin layer thickness results in force-extension curves that can be shifted along the Extension axis, from the theoretical 850 nm by ±30 nm. Grey area: ”single-tether region”. Tethers with a force-extension curve within this area that broke in a single step were regarded as single tethers and hence included in measuring the force-dependent lifetime.

Extended Data Figure 4. Nonlinear and temperature-dependent rheology of actin networks crosslinked by α-actinin-4 or K255E.

Rheological measurements of wild type (red) and K255E mutant (light blue) α-actinin-4 crosslinking actin networks at 10 °Cand of K255E mutant crosslinked actin networks at 25 °C(dark blue). a-c, The storage (triangles) and loss moduli (circles) were measured using small amplitude oscillatory shear. The moduli are shown as a function of frequency (a) and as a function of the frequency normalized by the frequency at which the loss modulus peaks (b). Both curves are measured at 10 °C. Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error indicated by bars and shaded regions on basis of 4 independent samples per condition. The collapses in b and c show that the crosslinker unbinding kinetics, but not the network structure, is significantly different for the different conditions (see Main Text). d, The stress relaxation frequency was extracted from Extended Data Figure 4a,c using Supplementary Methods Eq. 4-7. Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error on basis of 4 independent samples per condition. e, Representative example curves of the differential storage modulus at 0.5 Hz (top) and of the strain rate (bottom) are plotted against the applied shear stress. We define the rupture strain as the data point where K' peaks. f-g, We apply a semiflexible polymer network model to fit the frequency-dependent differential elastic modulus as a function of prestress (see Supplementary Methods). h, Thus, we extract the crosslinker bound lifetime as a function of stress for both α-actinin-4 (red) and the K255E mutant (blue) at 25 °C. The shaded areas represent the error on basis of the fits. The bound lifetime of the mutant is significantly longer at low stress, but the lifetimes of both types become similar at high stress as the bound lifetime of the wild type increases. The abrupt decay of bound lifetime in the K255E-crosslinked network when the stress reaches 5 Pa is due to network fracturing. i, the fitted K’ shows quantitative agreement with the measured K’ for both catch and slip bonds.

Extended Data Figure 5. Fracturing in the minimal 1D crosslinker model.

a, Time trace of the bound number of catch bonds (red) and slip bonds (blue) in a network undergoing a linearly increasing stress (see Supplementary Table 1 for parameters). As the catch bonds have faster dynamics than the slip bonds, a larger spread in the bound fraction is observed. After a long time of steady state fluctuations, the networks suddenly fracture as the number of linkers rapidly goes to 0. b, c, Kymographs showing at which positions there are bonds (red for catch bonds, blue for slip bonds) or no bonds (white). At steady state, linkers continuously bind and unbind (-1000 to approximately -300 steps). Cracks can spontaneously initiate and propagate through the network (the last ~300 steps of the simulation) for both catch and slip bonds in a similar manner. d, The fraction of 1D-networks that rupture when a gap of varying ablation length lablate is introduced for both catch (red) and slip bonds (blue). Inset: schematic of the ablation simulation.

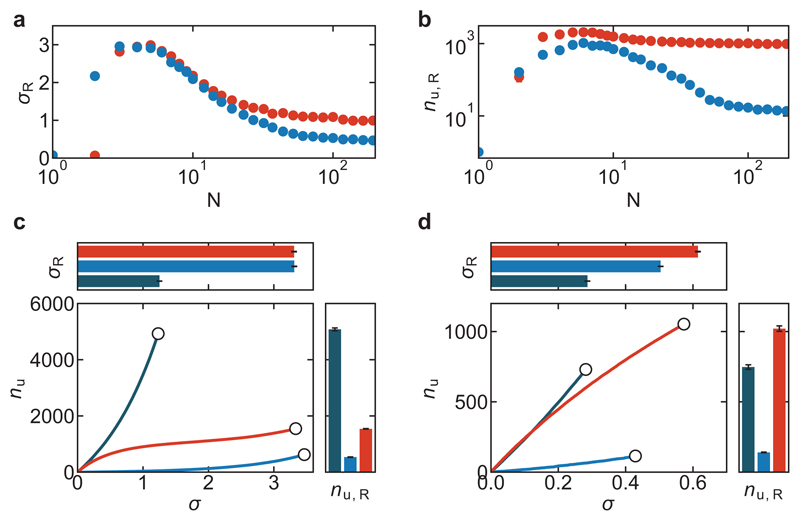

Extended Data Figure 6. Simulations show that catch bonds only provide a mechanical advantage over slip bonds when they are mobile and present in sufficiently large numbers.

The system size dependence of the rupture stress (a) and bond turnover at the point of rupture (b) reveals that catch bonds (red) are only stronger than slip bonds (blue) for networks larger than ~10 bonds, emphasizing that the increased network strength by catch bonding is an emergent property (Supplementary Note 1). Each data point is the average of 10 repeats and the standard errors are smaller than the symbol size. c, Catch bond-induced network strengthening is not observed when crosslinkers are immobile and rebind in the same location from which they unbound. The bond turnover as a function of stress reveals catch bonds (red) cause more dynamic materials (right), but do not enhance strength (top) compared to strong slip bonds (light blue) and are less dynamic than networks consisting of weak slip bonds (dark blue). Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error on basis of 100 independent simulation runs per condition. d, We also considered a three-state model where linkers are doubly bound, singly bound or unbound (Supplementary Note 1). Similar to the two-state model, the bond turnover as a function of stress reveals that networks of catch bonds (red) are stronger and more deformable than networks of strong slip bonds (light blue) or weak slip bonds (dark blue). Data are presented as mean values +/- the standard error on basis of 5 independent simulation runs per condition.

Extended Data Figure 7. Catch bonding is only effective when the bond lifetime is high.

a, Simulations of the rupture stress as a function of the bond lifetime , keeping fixed (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1), shows that catch bonds (red) are only stronger than slip bonds (blue) when the binding rate is high. b, Consistent with the simulations, enhancing the bond lifetime in experiments by decreasing the temperature from 25 °C(light) to 10 °C(dark) increases the rupture stress more steeply for wild type α-actinin-4 (red) than for K255E (blue). The error bars represent the standard error (N=4 independent samples for each condition).

Extended Data Figure 8. Actin network simulations.

a, Stress-strain curve of the simulated catch (red) and slip bond (blue) actin networks. The black circles indicate the yielding points of both networks (see Supplementary Methods). b, Distribution of tension on actin filaments in networks for simulated catch bond (red) and slip bond (blue) with 10 Pa stress. c, The polymer network simulation predicts that the average number of active crosslinkers per filament at 10 Pa is lower for catch bonds than for slip bonds, in line with the 1D simulations (panel a) and the catch bond’s lower bond lifetime. d, The average number of crosslinkers as a function of the filament tension shows that slip bonds are mainly enriched on low-tension filaments. The tension on the x-axis is binned such that each bin contains 10% of the filaments. e-f, Similar plots as Fig. 3d but then for the catch (d, red) and slip bond (e, blue) simulations separately: the active crosslinkers are binned according to tension acting on pairs of filaments (tension on filament 1 on x-axis, tension on filament 2 on y-axis) connected by the crosslinkers. 10x10 bins are used, and the distribution was smoothed using bicubic interpolation. The tension spacing along the x- and y-axis is non-uniform, such that each bin includes 10% of the filaments. These plots show that both catch and slip bonds preferentially connect tense filaments, likely because of geometrical reasons and/or because filament tension resulted from having more crosslinkers bound. However, catch bonds localize more strongly to tense filaments than slip bonds (Fig. 3d) because they bind less to the rest of the network due to their higher off-rate in the absence of force and therefore redistribute to the tense filaments (Fig. 3e).

Extended Data Figure 9. Confocal fluorescence images of crosslinked actin networks.

10% of the actin monomers were labeled with Alexafluor-647. At a 1:100 crosslinker:actin molar ratio, the actin networks studied in this work are isotropic and spatially uniform, for both wild type (a) and K255E α-actinin-4 (b). We do not observe any discernable structure because the mesh size is ~200 nm, which is on the order of the diffraction limit, indicating that filaments are isotropically crosslinked rather than bundled. c, For comparison, actin bundle clusters were observed at a 1:25 α-actinin-4:actin molar ratio. The color coding was inverted for all images to improve the visual contrast between bundles and background. Scale bars are 20 μm. 10 images were taken of different locations within the same sample per condition and all images had similar results per condition.

Extended Data Figure 10. Fracturing occurs within the actin network, not at the rheometer-network interface.

The rheology of wild type α-actinin-crosslinked actin networks was compared in the presence (dark green) or absence (light green) of a Polylysine-coated surface on both the bottom and top plate of the rheometer (see Supplementary Methods). a) a frequency sweep at zero prestress shows that the linear rheology is unaffected by changing the rheometer-network interface. The storage (triangles) and loss moduli (circles) were measured as a function of frequency using small amplitude oscillatory shear. b) the network rupture strain and c) rupture stress (bottom) are not significantly affected by the addition of Polylysine at the rheometer-network interface. The error bars representing the standard error (N=4 independent samples for each condition).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Martin van Hecke and Celine Alkemade for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Pieter Rein ten Wolde, Kees Storm, Wouter Ellenbroek, Chase Broedersz, David Brueckner and Mareike Berger for fruitful discussions. We thank William Brieher and Vivian Tang from the University of Illinois for the kind gift of purified α-actinin-4 (wild type and the K255E point mutant) and their plasmids, Marjolein Kuit-Vinkenoog and Jeffrey den Haan for actin and further purification of α-actinin-4, and Vanda Sunderlíková for design, mutagenesis, cloning and purifying of the α-actinin-4 constructs used in the single molecule experiments. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the following sources: research program of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (S.J.T., A.R. and M.J.A.), ERC Starting Grant (335672-MINICELL) (G.K. and Y.M.). “BaSyC – Building a Synthetic Cell” Gravitation grant (024.003.019) of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (G.K. and L.B.), and support from the National Institutes of Health (1R01GM126256) (T.K. and W.J.).

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.M. and G.H.K. conceived and designed the study. M.J.A. and S.J.T. designed the optical tweezer experiments. M.J.A., A.R. and L.B. performed the optical tweezer experiments. M.J.A. and A.R. analyzed the optical tweezer experiments. Y.M. performed and analyzed all other experiments and designed and simulated the 1D model. W.J. and T.K designed, performed and analyzed the actin network simulations. Y.M., M.J.A, T.K. S.J.T. and G.H.K. wrote the manuscript with input from W.J., A.R. and L.B. All authors approved the final version.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Marshall BT, et al. Direct observation of catch bonds involving cell-adhesion molecules. Nature. 2003;423:190–3. doi: 10.1038/nature01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu B, Chen W, Evavold BD, Zhu C. Accumulation of Dynamic Catch Bonds between TCR and Agonist Peptide-MHC Triggers T Cell Signaling. Cell. 2014;157:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbanga BL, Iyer BVS, Yashin VV, Balazs AC. Tuning the Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Grafted Nanoparticle Networks through the Use of Biomimetic Catch Bonds. Macromolecules. 2016;49:1353–1361. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas WE, Trintchina E, Forero M, Vogel V, Sokurenko EV. Bacterial Adhesion to Target Cells Enhanced by Shear Force. Cell. 2002;109:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang DL, Bax NA, Buckley CD, Weis WI, Dunn AR. Vinculin forms a directionally asymmetric catch bond with F-actin. Science (80-) 2017;357:1–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrie RJ, Koo H, Yamada KM. Generation of compartmentalized pressure by a nuclear piston governs cell motility in a 3D matrix. Science (80-) 2014;345:1062–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.1256965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yago T, et al. Platelet glycoprotein Ibα forms catch bonds with human WT vWF but not with type 2B von Willebrand disease vWF. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3195–3207. doi: 10.1172/JCI35754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo T, Mohan K, Iglesias Pa, Robinson DN. Molecular mechanisms of cellular mechanosensing. Nat Mater. 2013;12:1064–71. doi: 10.1038/nmat3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Zhang C-Z, Zhang X, Springer TA. A mechanically stabilized receptor-ligand flex-bond important in the vasculature. Nature. 2010;466:992–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng D, DuMontier C, Pollak MR. Mechanical challenges and cytoskeletal impairments in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Physiol Physiol. 2018;314:F921–F925. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00641.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrlicher AJ, et al. Alpha-actinin binding kinetics modulate cellular dynamics and force generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:201505652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505652112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribeiro EDA, et al. The structure and regulation of human muscle α-Actinin. Cell. 2014;159:1447–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao NY, et al. Stress-Enhanced Gelation: A Dynamic Nonlinearity of Elasticity. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110:018103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.018103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulla Y, Oliveri G, Overvelde JTB, Koenderink GH. Crack Initiation in Viscoelastic Materials. Phys Rev Lett. 2018;120 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.268002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulla Y, Koenderink GH. Crosslinker mobility weakens transient polymer networks. Phys Rev E. 2018;98:062503 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulla Y, Wierenga H, Alkemade C, ten Wolde PR, Koenderink GH. Frustrated binding of biopolymer crosslinkers. Soft Matter. 2019:3036–3042. doi: 10.1039/c8sm02429d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulla Y, Mackintosh FC, Koenderink GH. Origin of Slow Stress Relaxation in the Cytoskeleton. Phys Rev Lett. 2019;122:218102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.218102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung W, Murrell MP, Kim T. F-actin cross-linking enhances the stability of force generation in disordered actomyosin networks. Comput Part Mech. 2015;2:317–327. 2015 24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim T. Determinants of contractile forces generated in disorganized actomyosin bundles. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim T, Hwang W, Lee H, Kamm RD. Computational Analysis of Viscoelastic Properties of Crosslinked Actin Networks. PLOS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak M, Zaman MH, Kamm RD, Kim T. Interplay of active processes modulates tension and drives phase transition in self-renewing, motor-driven cytoskeletal networks. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10323. 2016 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseini K, Sbosny L, Poser I, Fischer-Friedrich E. Binding Dynamics of α-Actinin-4 in Dependence of Actin Cortex Tension. Biophys J. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grashoff C, et al. Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature. 2010;466:263–266. doi: 10.1038/nature09198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng D, et al. Disease-causing mutation in α-actinin-4 promotes podocyte detachment through maladaptation to periodic stretch. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:1517–1522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717870115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosales AM, Anseth KS. The design of reversible hydrogels to capture extracellular matrix dynamics. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:15012. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivera J, et al. Toughening mechanisms of the elytra of the diabolical ironclad beetle. Nature. 2020;586:543–548. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, et al. Visible-light-assisted multimechanism design for one-step engineering tough hydrogels in seconds. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4694. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18145-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Bailey JB, Subramanian RH, Groisman A, Tezcan FA. Hyperexpandable, self-healing macromolecular crystals with integrated polymer networks. Nature. 2018;557:86–91. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0057-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Manyes S, Liang J, Szoszkiewicz R, Kuo T-L, Fernández JM. Force-activated reactivity switch in a bimolecular chemical reaction. Nat Chem. 2009;1:236–242. doi: 10.1038/nchem.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dansuk KC, Keten S. Self-strengthening biphasic nanoparticle assemblies with intrinsic catch bonds. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.