Abstract

Objective

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) and its receptor VEGFR2 drive angiogenesis in a number of pathologies, including diabetic retinopathy, wet age-related macular degeneration and cancer. Studies suggest roles for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) in this process although the nature of this involvement remains elusive. Here, we set to establish the role of the HSPG Syndecan-4 (SDC4) in pathological angiogenesis.

Approach and Results

We report that angiogenesis is impaired in mice null for SDC4 in models of neovascular eye disease and tumor development. Our work demonstrates that SDC4 is the only syndecan whose gene expression is upregulated during pathological angiogenesis and is selectively enriched on immature vessels in retinas from diabetic retinopathy patients. Combining in vivo and tissue culture models, we identified SDC4 as a downstream mediator of functional angiogenic responses to VEGFA. We found that SDC4 resides at endothelial cell (EC) junctions, interacts with VE-Cadherin and is required for its internalization in response to VEGFA. Finally, we show that pathological angiogenic responses are inhibited in a model of wet age-related macular degeneration by targeting SDC4.

Conclusions

We show that SDC4 is a downstream mediator of VEGFA-induced VE-Cadherin internalization during pathological angiogenesis and a potential target for anti-angiogenic therapies.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Cadherin, Vascular Endothelial growth factor, Syndecan, vascular permeability

Subject terms: Angiogenesis, Animal Models of Human Disease, translational studies, cell biology/structural biology, vascular disease

Graphic Abstract.

Abbreviations

- CNV

Choroidal neovascularization

- DMBA

7,12-Dimethylbenz(a)anthracene

- EC

Endothelial Cell

- eGFP

Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein

- Erk

Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- HS

Heparan Sulfate

- HSPG

Heparan Sulfate Proteogylcan

- HUVECs

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells

- Lectin GS-II

Lectin GS-II from Griffonia simplicifolia

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- OIR

Oxygen Induced Retinopathy

- rtPCR

Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SDC

Syndecan

- TPA

Phorbol Ester

- VE-Cadherin

Vascular Endothelial Cadherin

- VEGFA

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A

- VEGFR2

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2

- WT

Wild-Type

Introduction

Angiogenesis is a critical developmental process and an essential component of physiological tissue regeneration 1. In the pathogenesis of neovascular eye diseases, cancer and inflammatory disorders, new blood vessel formation is a key feature and significant efforts have been made to control this process for therapeutic benefit 2–6 The pro-angiogenic cytokine vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and its receptor VEGFR2 regulate angiogenesis in these pathologies; promoting endothelial cell (EC) survival, proliferation and migration 7. The movement of ECs during new vessel growth depends on the remodeling of EC junctions and VEGFA has a crucial role in regulating the junctional concentration of vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-Cadherin) 8–12. The presence of a heparin binding domain on the most biologically active isoform of VEGFA, VEGFA164/165, is suggestive of a role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) in angiogenesis, particularly in facilitating the engagement of ligand with receptor 13, 14. For this reason the four-member syndecan family of HSPGs have been proposed to have roles in this process 15. Syndecans consist of a short cytoplasmic domain, a single-pass transmembrane domain and a larger extracellular core protein which is substituted with predominantly HS chains. Numerous interactions with these sugars and bioactive molecules such as growth factors and extracellular matrix molecules have been reported 16–19. Recent studies have shown syndecan-2 (SDC2) forms a tri-molecular complex with VEGFA165 and VEGFR2 leading to enhanced signaling. In contrast, syndecan-4 (SDC4), the family member most closely related to SDC2, has no impact on VEGFA signaling. This difference was linked to enhanced 6-O-sulfation on SDC2 HS chains which is determined by unique sequence motifs contained in the extracellular core protein of SDC2 20 Several studies have identified a pro-angiogenic role for SDC4 in response to stimuli such as FGF2 and Prostaglandin E2 and adult Sdc4-/- mice exhibit defects in the development of fetal vessels in the placental labyrinth and in angiogenesis during granulation tissue formation after wounding 21–25. All of which, is suggestive of a functional requirement for SDC4 in new blood vessel formation.

Here, we set out to elucidate the function of SDC4 in VEGFA-driven pathological angiogenesis using a variety of disease models. We found that Sdc4-/- animals are protected in both murine models of neovascular eye disease and skin tumor models. SDC4 gene expression, unlike that of other family members, increases during pathological angiogenesis but not during developmental angiogenesis in mice, and is selectively expressed on immature blood vessels in retinas of diabetic retinopathy patients. Functional assays, such as VEGFA-induced ex vivo sprouting and cell migration demonstrate a strong requirement for SDC4, although VEGFR2 signaling in response to VEGFA is normal in Sdc4-/- null ECs. We show that SDC4 acts downstream of VEGFA/VEGFR2, and is required for efficient VE-Cadherin trafficking away from EC junctions in response to VEGFA. Finally, we demonstrate that targeting SDC4/VE Cadherin interaction in a pre-clinical model of Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration leads to inhibition of pathological angiogenesis. These findings identify SDC4 as an important regulator of VE-Cadherin trafficking in VEGFA-driven junctional reorganization, an essential component of pathological angiogenesis, and as such has the potential to be targeted for therapeutic benefit.

Materials and Methods

Please see the Major Resources Table and additional Materials and Methods in the Supplemental Material

Experimental animals

Sdc4-/- mice (on a C57BL/6J background)22 were obtained from the Centre for Animal Resources and Development (CARD, Kunamoto University, Japan) with the kind permission of Professor Tetsuhito Kojima (Nagoya University, Japan). All adult mice were used at an age between 5-8 weeks at an average weight of 25 g. Unless stated male mice were used since sex differences in the responses measured are negligible. As appropriate, age-matched control mice were littermates or C57BL/6J wild-type mice purchased from Charles River. Unless stated male animals were used in these studies, since the differences between males and females in the models used is negligible. Animals were housed and treated in Accordance with UK Home Office Regulations and all experiments were approved by the UK Home Office according to the Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 (ASPA) and by the National Animal Ethics Committee of Finland.

Developmental angiogenesis mouse model

Neonatal WT, Sdc4+/- and Sdc4-/- littermates (both male and female) were euthanized at P6 and retinal flat mounts were prepared for lectin GS-II staining. Briefly, retinas were washed extensively in PBS, blocked in 3% BSA followed by overnight staining with lectin GS-II-Alexa594 and an anti-αSMA-alexa488 antibody (1:150, Sigma, in-house conjugated) in 0.5% triton in PBS. Retinas were imaged using confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss LSM 700) with 10× objective. The rate of developmental angiogenesis at P6 was determined by measuring the diameter of vasculature via the optic nerve to the tips of the blood vessels. Two measurements per retina were taken and an average was calculated.

Oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model

Neonatal mice (both male and female) at P7 were exposed to 75% oxygen for 5 days with their nursing mothers. At P12, they were returned to normoxia. Animals were euthanized at P12 to determine the area of vaso-obliteration or at P17 to determine the rate of retinal revascularization and pre-retinal neovascularization 26, 27. As postnatal weight gain has been shown to affect outcome in the OIR model 28, only weight matched (±1 g) pups were used in each experiment. Analysis of retinal vasculature was done as previously described 29. Briefly, eyes were enucleated, fixed with 4% PFA for one hour and retinas dissected. Flat mount retinas were blocked in 10% normal goat serum and 10% fetal bovine serum for 2 hours, incubated overnight with isolectin GS-IB4 (1:100). Briefly, retinas were imaged using confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss LSM 700) with 10× objective. Pre-retinal neovascular tufts were readily distinguished from the superficial vascular plexus by focusing just above the inner limiting membrane. Areas of vascular obliteration and pathological neovascularization (neovascular tufts) were quantified using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV) mouse model

WT and Sdc4-/- 6 week old male mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 0.15 ml of a mix of Domitor and Ketamine and pupils dilated with topical administration of 1 % Tropicamide and 2.5 % Phenylephrine. Three burns per eye were be made by laser photocoagulation (680 nm; 100 μm spot diameter; 100 ms duration; 210 mW). Only burns that produced a bubble, indicating the rupture of the Bruch’s membrane, were counted in the study. At day 7 after the laser injury, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was performed to measure the area of CNV lesion. The area of lesion was then quantified using Imaris Software (Bitplane) and expressed as number of pixels. Additionally, at the end of the experiment (day 7) mice were culled, choroid-RPE tissue dissected, flat-mounted and stained with lectin GS-II. Confocal images were then acquired using a PASCAL laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) followed by volumetric analysis with Imaris software (Bitplane).

B16F1 melanoma tumor model

B16F1 mouse melanoma cells were obtained from HPA Laboratories (UK) and 5x107 cells/ml in 100 μl of PBS were injected sub-cutaneously into the left flank of 6 week old male WT and Sdc4-/- mice (n=12 per group). Mice were left for 7 or 14 days prior to sacrifice by cervical dislocation. A longitudinal incision was made from the chest to the genital area, skin was peeled and pinned down and tumors were revealed. Photographs were taken with a digital camera and tumors excised using scalpel and tweezers. Samples were then weighed on a precision balance and diameter measured using a ruler. Samples were then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C.

Skin tumor induction

Sdc4-/- and C57BL/6 WT male mice were treated with DMBA and TPA to induce skin tumors according to the established protocol30–32. In brief, the backs of 8 week old mice were shaved and 24 h later 50 μg DMBA (7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene) (Sigma, Dorset, UK) in 200 μl acetone was applied topically on the shaved area of the dorsal skin. After a week, the back skin of the mice was treated twice a week with 5 μg TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) (Sigma) in 200 μl acetone for 21 weeks. Tumors (1 mm in diameter or larger) were counted twice a week. The fur excluding tumors was carefully shaved every two weeks.

VE-Cadherin internalization assay

Cells were serum starved for 3 hours prior to incubation for 1 hour at 4 °C in the presence of an anti-VE-Cadherin antibody (clone BV13, eBioscience) conjugated in-house to Alexa555. Unbound antibody was washed away using serum free medium. 30 ng/ml of VEGFA was added to cells for 5 min at 37 °C to allow internalization of VE-Cadherin and bound antibody. For analysis of internalized VE-Cadherin, cell surface bound antibody was removed using an acid wash (glycine 25 mM, 3% BSA in PBS, pH 2.7). Cells were washed 3X with ice cold PBS and fixed with 4 % PFA, 0.25 % glutaraldehyde prior to analysis by confocal microscopy.

Proximity ligation assay

Proximity ligation assay or PLA is a technique that allows the identification in situ of spots in which 2 proteins are in close proximity (less than 40 μm). The PLA experiments were performed as per manufacturer’s instructions (Duolink, Sigma Aldrich). Cells were treated as indicated in the results section. Following treatments, medium was taken off, cells were washed in PBS at RT, fixed in 4 % PFA for 15 min at RT. After a 5 min wash in PBS, PFA was quenched by incubating cells with 0.1 M NH4CL for 10 min at RT.

Evans blue permeability assay

6-8 week old male mice were anesthetized by i.m. injection of 1 ml/kg ketamine (40 mg) and xylazine (2 mg) in saline solution. The back skin was shaved using an electric razor. Mice then received Evans Blue dye (0.5 % in PBS, 5 μl per g bodyweight) i.v. through the tail vein. Afterwards, 50 μl of PBS containing either 100 ng of VEGFA or 100 μg of Bradykinin or PBS alone were injected s.c. in the mouse dorsal skin. After 90 min animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Dorsal skin was removed and injected sites were cut out as circular patches using a metal puncher (~8 mm in diameter). Samples were then incubated in 250μl of formamide at 56 °C for 24 h to extract Evans Blue dye from the tissues. The amount of accumulated Evans Blue dye was quantified by spectroscopy at 620 nm using a Spectra MR spectrometer (Dynex technologies Ltd., West Sussex, UK). Results are presented as the optical density at 620 nm (OD620) per mg tissue and per mouse.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. and sample sizes are reported in each figure legend. Each experiment on animals was performed on at least two independent litters of a given genotype. Data were plotted and analyzed for statistical significance using Prism 6 (Graphpad software Inc.). Welch’s t-test was used when two independent groups were compared. Parametric statistical tests (two-tailed t-test and one- or two-way ANOVA) were used to compare the averages of two or more groups. Normality and variance were not tested to determine whether the applied parametric tests were appropriate. Bonferroni post-hoc test was used when we were interested in a set number of planned comparisons (i.e. Control vs Mutant(s)). Tukey post-hoc test was used when wanting to make unplanned pairwise comparisons (i.e. time-points). Spearman’s rank correlation test was conducted to test correlation between multiple variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

SDC4 is dispensable for vascular development but essential for pathological angiogenesis

As with other syndecan family members, adult Sdc4-/- animals show no abnormalities and are phenotypically comparable to wild-type (WT) littermates which is suggestive of normal development. In accordance with this hypothesis and in keeping with a recent study 20, we observed no major differences in postnatal retinal vascular development between WT, Sdc4+/- and Sdc4-/- P6 neonates (Fig. 1 A and B). This was also reflected by the absence of any differences in the number of arteries and veins between the genotypes (Fig. S1 A). Analysis of parameters such as vessel size (Fig. S1 B and C), density (Fig. S1 D), and pericyte coverage (Fig. S1 E) in additional adult vascular beds (skin, muscle and connective tissue, Fig. S1 F) confirmed that Sdc4-/- animals developed a normal vascular network indicating that angiogenesis during development was not affected in Sdc4-/- mice.

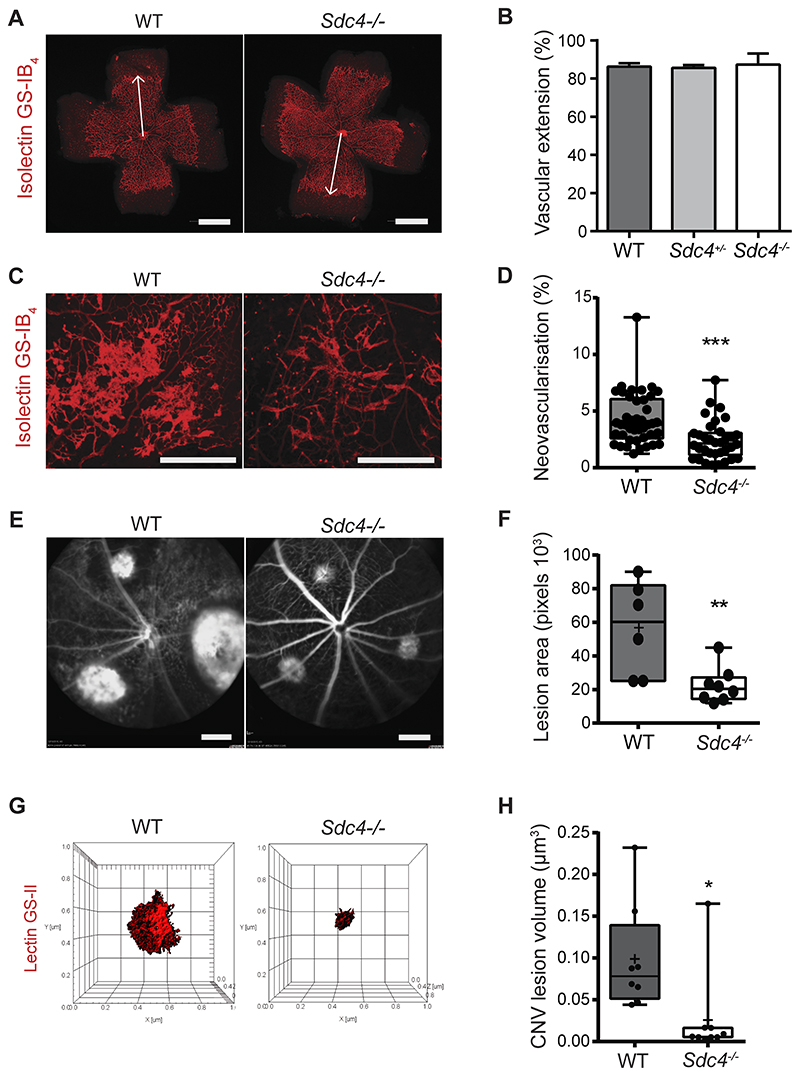

Figure 1. Pathological angiogenesis in murine models of neovascular eye disease requires SDC4.

Developmental retinal angiogenesis in Sdc4-/- mice proceeds at the same rate as WT. A, Micrographs comparing retinal micro-vessel formation between Sdc4-/- and WT p6 neonates (Scale bar, 1 mm). B, Retinas were stained with isolectin GS-IB4, and the distance between the optical nerve and the angiogenic front (arrows) was measured and the extent of retinal angiogenesis between WT, Sdc4+/- and Sdc4-/- p6 neonates compared (n=10-15 animals/genotype). C, Neovascular tuft formation in response to OIR is reduced in Sdc4-/- p17 neonates. Representative micrographs of retinas stained with isolectin GS-IB4 (scale bar = 500μm). D, Quantification of neovascular tufts (~40 eyes/group). E, Micrographs showing Sdc4-/- animals exhibit less angiogenesis in the laser induced CNV model as evident from reduced lesion area (n=6-8 animals/group, Scale bar = 2.4 mm). F, Densitometry measurements of CNV lesions comparing responses between WT and Sdc4-/- animals. G, Staining of CNV lesions with lectin GS-II followed by 3D confocal reconstruction. H, CNV lesion volume was calculated using Imaris Bitplane software on the basis of lectin GS-II staining. n=5-6 animals for each group. Centre line, median. Plus sign, mean. Error bars indicate min and max values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P<0.001.

We next examined whether angiogenic responses in disease models were affected by genetic deletion of SDC4. Oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) is a hypoxia-driven angiogenesis model that recapitulates features of diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity33. OIR was performed on 7-day old WT and Sdc4-/- pups by exposing them to hyperoxia (75 % O2 for 5 days) leading to the abolition of the retinal vasculature, before being returned to normoxia which stimulates a neovascular response. Exposure to oxygen led to a comparable loss in retinal vasculature in both Sdc4-/- and WT control littermates (Fig. S2 A and B); however, upon return to normoxic conditions it was evident that the formation of neovascular tufts (a hallmark of pathological angiogenesis) was significantly reduced (~ 40% decrease) in the retinas of Sdc4-/- mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1 C and D). In contrast, the physiological neovascular response associated with hypoxia in Sdc4-/- animals was only slightly increased as determined by smaller avascular areas in these animals 5 days post-hyperoxia compared to Wt littermates (Fig. S2 C and D). We next investigated whether neovascularization was also attenuated in Sdc4-/- mice in the laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV) model which mimics neovascular (‘wet’) age-related macular degeneration 34. Laser photocoagulation was performed on the eyes of 6-week old WT and Sdc4-/- littermates to stimulate a neovascular response in the choroid. Areas of CNV measured 7 days after injury by fluorescein angiography were found to be significantly smaller in the eyes of Sdc4-/- mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1 E and F). CNV lesions were predominantly composed of ECs on the basis of lectin GS-II staining and we confirmed the reduction in lesion volume (~80% decrease) in Sdc4-/- mice using 3D confocal reconstruction (Fig. 1 G and H). Together, this data highlights the requirement for SDC4 in promoting vessel growth in two models of neovascular eye disease.

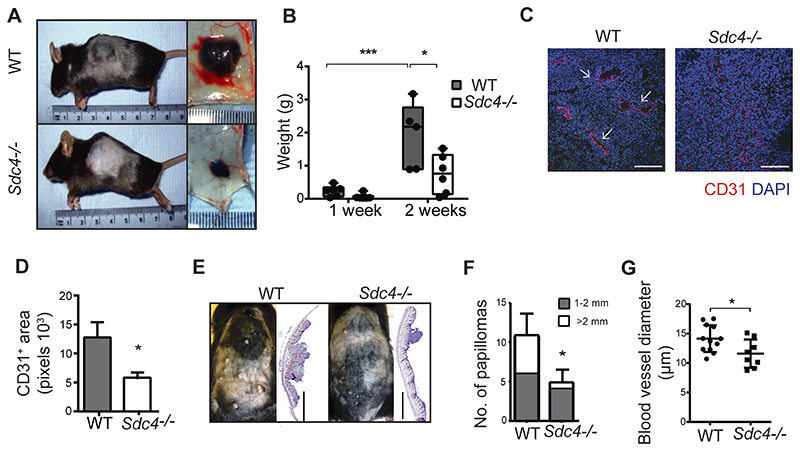

Angiogenic defects are not restricted to ocular disease models in Sdc4-/- mice

We next set out to establish whether the angiogenic defects observed in Sdc4-/- mice were restricted to ocular neovascularization or would extend to angiogenic-driven tumor development models. In the first instance, we injected B16F1 melanoma cells (which express SDC4, Fig. S3 A) into the flank of WT and Sdc4-/- mice. Animals were sacrificed after 2 weeks and both tumor volume and tumor weight were significantly reduced in the Sdc4-/- mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 2 A and B, Fig. S3 B). Critically, immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections for EC specific markers CD31 and Podycalyxin revealed vascular structures, with in many cases, a well-defined lumen (white arrows in Fig. 2 C and D, Fig. S3 C and D), whereas in tumors from Sdc4-/- mice, ECs failed to organize into tubules and were more sparsely distributed (Fig. 2 C and D, Fig. S3 C and D). We next tested whether this was also the case in a model of epidermal papilloma formation induced by two stage treatment with DMBA and TPA, the progression of which, is angiogenesis-dependent 30, 35. At the end point of 19-weeks, WT animals had on average 2.4 times more tumors than Sdc4-/- mice and the incidence of large tumors was 6-fold higher (Fig. 2 E and F). In the DMBA/TPA model, tumor angiogenesis takes place first by increased blood vessel density and later, during papilloma formation, by increased blood vessel diameter. Histochemical staining for the EC marker CD31 revealed smaller blood vessel lumens in tumors formed in Sdc4-/- mice compared to WT (Fig. 2 G and Fig. S3 E). Together this data provides compelling evidence that the role of SDC4 in pathological angiogenesis is not restricted to neovascular eye disease, but also extends to tumor development.

Figure 2. Tumor angiogenesis is impaired in Sdc4-/- animals.

A, Micrographs of B16F1 melanomas from WT and Sdc4-/- animals showing reduced tumor volume as quantified in B, (n=5-6 mice/group). C, Tumor vessels (arrowheads) appear in WT sections but are not obvious in B16F1 melanomas from Sdc4-/- mice (Ki-67, blue; CD31 red, scale bar, 100 μm), D, quantification of tumor vessel coverage (n=5/group, 3 images/animal). E, Papilloma formation is reduced in Sdc4-/- mice in the DBMA/TPA model. Micrographs of animals (left) and sections of skin (right, H&E stained) from WT and Sdc4-/- animals at week 19 (scale bar, 2 mm). F, Reduced size of papillomas at end of the experiment (n=7 mice/group). G, Tumor sections from WT and Sdc4-/- animals were immuno-stained for the EC marker CD31and vessel width was measured. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

SDC4 is upregulated during pathological angiogenesis

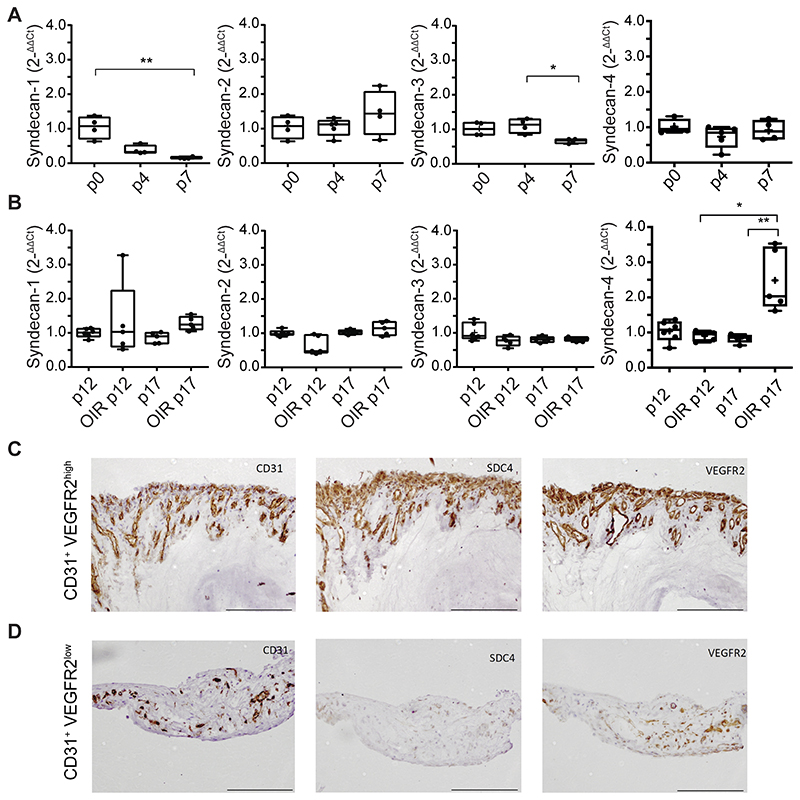

To understand further the role of SDC4 in pathological angiogenesis, we next compared syndecan gene expression in both the context of developmental and pathological angiogenesis in the murine retina. During the early stages of murine postnatal development, angiogenesis occurs in the eye leading to the formation of a superficial retinal vascular plexus and in C57BL/6 mice this occurs during the first 8 days after birth. Quantitative rtPCR was performed on retinal mRNA from day P0, 4, and 7 neonates to measure the expression of SDC1, -2, -3 and -4 during development. SDC1 and -3 showed downregulated expression over time, whereas SDC2 and -4 remained unchanged (Fig. 3 A). Next, we examined the transcript profile of syndecans in a murine model of retinal pathological neovascularization. When pups were subjected to OIR, we detected a marked increase in SDC4 gene expression in retinas at P17, the time point at which neovascularization peaks, whereas the expression of the other 3 syndecans remained stable (Fig. 3 B). Interestingly, this was also the case in both the laser CNV model and in B16F1 melanomas. SDC4 gene expression was upregulated in retinas 7 days post laser injury as compared to control retinas (Fig. S4 A). This was also the case when SDC4 gene expression was analyzed in B16F1 melanomas (7 days post injection), when compared to B16F1 cells in culture (Fig. S4 B). These increases in gene expression were not a characteristic of the other SDC family members, the exception being SDC3 in the B16F1 melanoma model, which according to previous studies, could be immune cell derived36.

Figure 3. SDC4 expression is upregulated during pathological angiogenesis.

A, Syndecan gene expression profile during early stages of murine retinal angiogenesis. Eyes were enucleated on postnatal day 0, 4 and 7, mRNA extracted and quantified by qPCR. B, Syndecan gene expression in neonates subjected to OIR (P12 vaso-obliteration phase, P17 angiogenic phase) and in untreated controls. Centre line, median. Plus sign, mean. N=4-6 animals for each group. Error bars indicate min and max values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (C, and D,) Consecutive sections of human proliferative diabetic retinopathy membrane stained for CD31 marker of blood vessels), VEGFR2 (marker of new immature vessels), and SDC4. Regions of high VEGFR2 expression on ECs have correspondingly high levels of Sdc4 expression C, and this is not the case on sections where there is low VEGFR2 expression D,. Scale bar, 200 μm. Images are representative of n=6 patients.

To investigate whether SDC4 was upregulated in a human disease setting, we analyzed its expression in the retinal neovascular membranes that develop in human diabetic retinopathy patients. Neovascular membranes were collected from type I diabetes patients suffering from retinopathy, who had either already developed or had threatening tractional retinal detachment due to fibro-vascular proliferation. These tissue samples represented the end stage of the disease, but still contained regions with active pathological angiogenesis. Histological analysis of adjacent tissue sections revealed SDC4 expression predominantly associated with blood vessels (CD31+ areas). Moreover, immunostaining for VEGFR2 (a marker of pathological immature blood vessels) and CD31 revealed that SDC4 expression strongly correlated with CD31+/VEGFR2high blood vessels, whereas only moderate expression was detected in CD31+/VEGFR2low areas (Fig. 3 C and D, Fig. S4 C). We conclude from this that, at least in the context of neovascular eye disease, SDC4 expression positively correlates with newly formed, immature blood vessels during pathological angiogenesis in both murine models and in human neovascular disease.

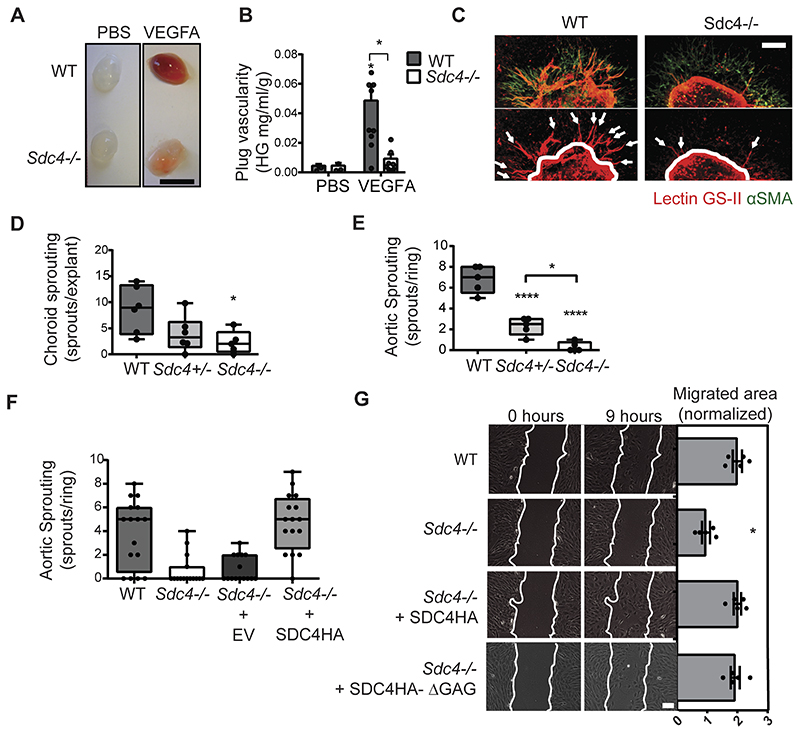

Angiogenic responses to VEGFA require SDC4

As the principal driver of angiogenesis in the models described above is VEGFA, we therefore wanted to explore whether responsiveness to VEGFA was a factor in the phenotypes we observed in Sdc4-/- animals. WT and Sdc4-/- mice were injected with Matrigel containing VEGFA which triggered an angiogenic response in WT mice as evidenced by plug hemoglobin content. In contrast, an angiogenic response was notably reduced in VEGFA-containing plugs from Sdc4-/- mice (Fig. 4 A and B). We next adopted a more reductive approach in which tissue explants from both choroid membranes and aortas from Sdc4-/-, Sdc4+/- and WT littermates were embedded in a collagen I matrix and exposed to VEGFA. In both cases, significantly more angiogenic sprouts emerged from WT, compared to Sdc4-/- explants (Fig. 4 C to E). Interestingly, explants from heterozygous (Sdc4+/-) mice exhibited an intermediate phenotype indicating that the angiogenic response to VEGFA associated with SDC4 is subject to gene dosage effects. WT levels of angiogenic sprouting was restored in Sdc4-/- null aortic rings transduced with lentiviruses to re-express full length SDC4 (Fig. 4 F), confirming the requirement of SDC4 for this response. Of importance, angiogenic responses to an alternative pro-angiogenic factor FGF2 were comparable between WT and Sdc4-/- animals, in both the Matrigel plug and the aortic ring assays (Fig. S5 A to C).

Figure 4. Functional angiogenic responses to VEGFA are impaired in Sdc4-/- explants and ECs.

A, Matrigel supplemented with PBS or VEGFA (50 ng) was injected subcutaneously in the flank of WT or Sdc4-/- mice. Images are representative of plugs extracted 7 days post-injection. Scale bar, 1 cm. B, Plug vascularity was expressed as the amount of haemoglobin released from the plugs per ml of Matrigel and normalized for the plug weight. n=5-6 animal for each group (2 plugs per animal). C, Fragments (1 mm2) of choroid were dissected from adult WT, Sdc4+/- and Sdc4-/- littermates and cultured as explants in VEGFA-containing medium. Explants were stained with lectin GS-II (red) and anti-αSMA (green) after 7 days in culture and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 10x objective. Arrows show angiogenic sprouts. Scale bar, 100 μM. D, Sprouting was quantified by manually counting the number of sprouts per explant. n=5-6 animal for each group, 10 explants per animal. E, Quantification of sprout formation from aortic ring explants (n=5-6 animal for each group, 15-20 rings per animal). F, Sdc4-/- aortic rings were lentivirally transduced to express either eGFP (EV) or SDC4 (SDC4), n=3 animals per group, 5-6 explants per animal. G, Sdc4-/- MLECs were lentivirally transduced to express either SDC4 or SDC4ΔGAG, and the migration of these cells compared to WT and Sdc4-/- in scratch wound migration assays. Cells were serum starved prior to the addition of VEGFA (10 ng/ml) and images at 0 hours and 9 hours are shown. Scale bar, 200 μm. Migrated area was calculated by subtracting the final scratch area from the initial scratch area using ImageJ. n=3-4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001.

On the basis of these results, we hypothesized that endothelial SDC4 could be involved in the specific regulation of VEGFA-dependent EC responses. To this end, we analyzed EC migration by light microscopy and observed that while primary Sdc4-/- lung ECs were able to migrate in a growth factor-rich environment (FBS), albeit slightly less than WT ECs, their migratory response to VEGFA stimulation was negligible (Fig. S4 D and E). We further demonstrated that EC migration in response to VEGFA could be restored in Sdc4-/- ECs upon re-expression of full length SDC4 (Fig. 4 G) and, interestingly, also by a mutant form of SDC4 lacking the glycosaminoglycan chains (SDC4HA-ΔGAG), suggesting that GAG chains were not required for this function. These data suggest that the pro-angiogenic role of SDC4 in pathological neovascularization is linked to defective EC responses to VEGFA.

SDC4 resides at EC junctions and is redistributed in response to VEGFA

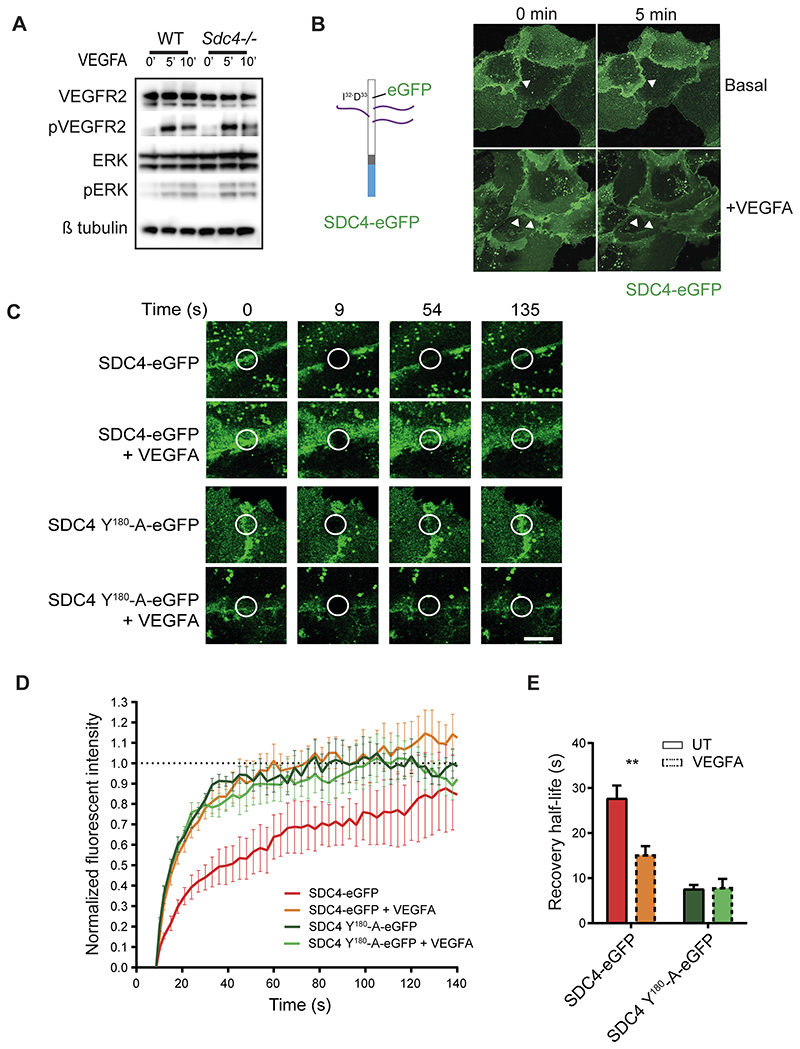

Previous studies have indicated that SDC4 does not impact on VEGFR2/VEGFA signaling 20. To confirm this, we looked at VEGFR2 phosphorylation in response to VEGFA in primary lung ECs from WT and Sdc4-/- mice and observed no differences (Fig. 5 A). This was also true of the downstream signaling kinase Erk1/2 which was also phosphorylated to the same extent in WT and Sdc4-/- ECs in response to VEGFA (Fig. 5 A). We also measured cell surface expression of VEGFR2 in WT and Sdc4-/- cells and found this to be the same (Fig. S5 F).

Figure 5. SDC4 acts down stream of VEGFA/VEGFR2 signaling.

A, Western blots of either WT or Sdc4-/- MLEC lysates harvested at different time points after VEGFA stimulation. Levels of phoshpo-VEGR2 and Erk1/2 were assayed. B, The complete coding sequence of eGFP was inserted into murine SDC4 between I32 and D33 and cloned into lentiviral expression vectors (diagram). Fluorescence confocal images of transfected HUVECS showing SDC4-eGFP localizes to EC junctions, and this is altered by VEGFA stimulation. Images correspond to the first and last of a 5 minute time lapse video (see Supplemental Movies 1 and 2). Cells were stimulated as indicated. C, Confocal images of FRAP of HUVECs expressing SDC4-eGFP or SDC4 Y180-A-eGFP at the time points indicated in the presence or absence of VEGFA stimulation. FRAP and image capture were performed using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 63x objective. D, Quantification of fluorescence recovery of Sdc4-eGFP and E, plots of the half-life of recovery for each of the treatments. n=3, **p<0.01.

In order to understand the role of SDC4 in ECs during angiogenesis, we examined its localization in HUVECs. We expressed an eGFP tagged form of SDC4 in ECs (eGFP inserted between I32 and D33 of murine SDC4 cDNA, Fig. 5 B), and observed a pool of SDC4-eGFP localized to EC junctions (Fig. 5 B, white arrows). Interestingly, stimulation of these transfected HUVECs with VEGFA led to a substantial redistribution of SDC4-eGFP (Fig. 5 B, Supplemental movies 1 and 2) which was not the case in unstimulated cells. To explore this further we used fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) to measure the kinetics of diffusion of SDC4-eGFP with and without VEGFA stimulation. We performed photo-bleaching of SDC4-eGFP at EC-EC contacts and observed the rate of recovery of fluorescence both under basal and VEGFA-stimulated conditions. Recovery of SDC4-eGFP fluorescence was significantly enhanced by the addition of VEGFA (Fig. 5 C to E), suggesting that the addition of VEGFA alters the functional status of SDC4. Previous studies have shown that phosphorylation of SDC4 at Y180 by Src kinase is essential for regulating the trafficking of integrins in fibroblasts37. To this end, we asked whether phosphorylation of this residue was important for the VEGFA stimulated response observed above with Sdc4-eGFP. We generated a mutant form of Sdc4-eGFP in which Y180 of SDC4 was mutated to an Alanine to make it nonphosphorylatable (SDC4(Y180-A)-eGFP). Interestingly, recovery of SDC4(Y180-A)-eGFP fluorescence was as rapid as SDC4-eGFP treated with VEGFA, regardless of whether they were treated with VEGFA or not (Fig. 5 C to E). Enhanced fluorescence recovery rates are often associated with molecules dissociating from a complex, so these results suggest that VEGFA stimulates the disassociation of SDC4 from a molecular complex at EC junctions and that this association requires SDC4 to be phosphorylated at Y180. Taken together, these data indicate that not only is a pool of SDC4 resident at EC junctions, but its function is driven by VEGFA signaling.

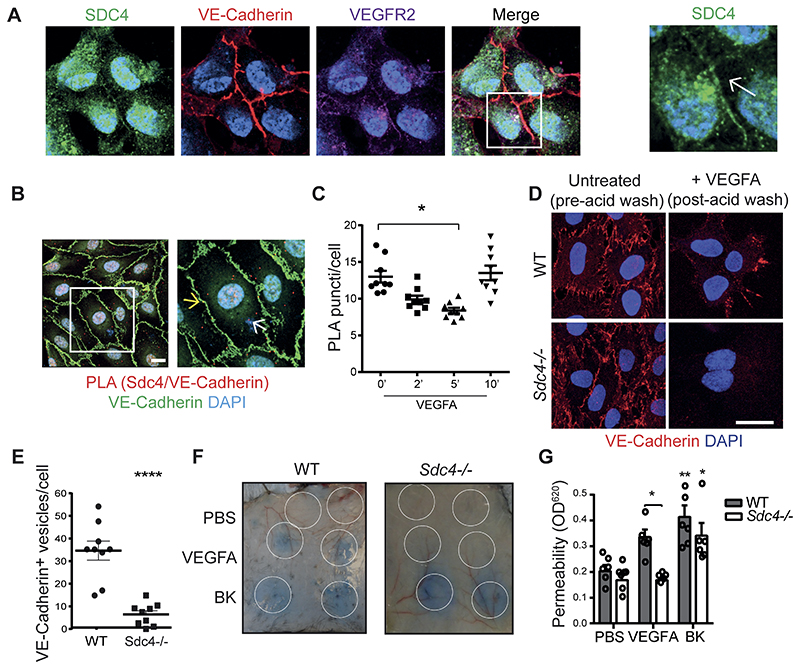

SDC4 is required for VEGFA-induced VE-Cadherin internalization and hyper-permeability

We further explored the enrichment of SDC4 at EC cell-cell contacts, this time in untransfected cells. Here, consistent with our earlier observation in cells expressing Sdc4-eGFP, we found a pool of SDC4 at EC junctions co-localizing with both VE-Cadherin and VEGFR2 (Fig. 6 A). We next performed Proximity Ligation Assays (PLA) on SDC4 and VE-Cadherin and detected interactions between these two molecules under basal conditions (Fig. 6 B). This interaction declined after 2 and 5 mins following VEGFA treatment and recovered after 10 minutes (Fig. 6 C). We confirmed an interaction between SDC4 and VE-Cadherin by performing immuno-precipitation experiments with HA-tagged forms of SDC4 expressed in HUVECs. VE-Cadherin was detectable in anti-HA immuno-precipitates from cells expressing SDC4HA or SDC4HA-ΔGAG, suggesting that SDC4 GAG chains are not required for this interaction. Interestingly, more VE-Cadherin was present in immuno-precipitates from cells expressing SDC4HA-Y180-F a phosphomimetic, compared to the nonphosphorylatable form SDC4HA-Y180-A (Fig. S6 A). Furthermore, less VE-Cadherin was evident in immuno-precipitates from SDC4HA transduced cells following treatment with VEGFA (Fig. S6 B). Collectively, this data suggests that phosphorylated SDC4 interacts with VE-Cadherin, and that treatment with VEGFA leads to dephosphorylation of SDC4 and the disruption of this interaction.

Figure 6. SDC4 is required for efficient VE-Cadherin redistribution at EC junctions in response to VEGFA.

A, Immunofluorescence staining for endogenous SDC4 (green) shows co-localization with VE-Cadherin (red) and VEGFR2 (purple) at EC junctions. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, Confocal micrographs of HUVECs showing proximity ligation puncti on the cell surface (red dots) between SDC4 and VE-Cadherin (nuclei, blue; VE-Cadherin, green). An example of junctional punctum (yellow arrow) and a non-junctional punctum (white arrow) is shown on the right hand micrograph. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, Quantification of SDC4/VE-Cadherin PLA puncta on the cell surface over time after VEGFA stimulation (10ng/ml). D, MLECs from WT and Sdc4-/- mice were washed with PBS and incubated with anti-VE-Cadherin antibody at 4 °C for 1 hour. Unbound antibody was washed away and cells stimulated with VEGFA (30 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C to promote VE-Cadherin internalization. Cells were then subjected to an acid wash to remove cell surface antibody. VE-Cadherin (red), DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. E, Images of MLECs treated with VEGFA and acid-washed were analyzed on Imaris software and VE-cadherin+ vesicles were counted and divided by the number of nuclei in the field of view. n=3. Images are representative of one experiment where 9 images per condition were analyzed F, Evans blue was injected into the tail vein of WT and Sdc4-/- mice, followed by subcutaneous injections of PBS, VEGFA (100 ng) or Bradykinin (BK, 100 μg). Images show the local extravasation of the dye from underneath the skin 90 minutes post-injection, white circles indicate the approximate injection area. G, Skin punches corresponding to the injection sites were collected and Evans blue extracted in formamide overnight. Permeability was quantified by measuring the optical density at 620 nm of the skin extracts and values were normalized on the basis of tissue weight. n=6-8 animals per condition. Data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P<0.0001. Statistical comparisons were made between PBS and treatments within the same genotype unless otherwise indicated.

This led us to postulate that SDC4 could play a role in the regulation of VEGFA-induced VE-Cadherin internalization and tested this hypothesis in an antibody-feeding assay. We found that primary Sdc4-/- ECs displayed reduced VE-Cadherin internalization following exposure to VEGFA compared to WT ECs (Fig. 6 D and E). Additionally, cell surface biotinylation experiments revealed that whilst in WT cells biotinylated cell surface VE-Cadherin is reduced after VEGFA treatment, this was not the case with Sdc4-/- MLECs (Fig. S6 C). In line with this observation, newly-formed blood vessels in retinas from Sdc4-/- OIR mice had fewer intracellular VE-cadherin+ vesicles compared to WT vasculature, whereas VE-cadherin immunostaining was more discontinuous and VE-Cadherin+ vesicles were more abundant (Fig. S7). Expression of SDC4HA, and SDC4HA-Y180-F all restored VE-Cadherin internalization responses to VEGFA in Sdc4-/- MLECs, which was not the case in SDC4HA-Y180-A transduced cells (Fig. S8). Since VEGFA-dependent endocytosis of VE-Cadherin from the EC adherens junctions is a known to trigger of vascular permeability in vivo 38, we next measured the leakage of albumin-bound Evans blue from the dermal microvasculature in response to VEGFA and bradykinin (a known vasodilator) in WT and Sdc4-/- animals. Results showed that vascular leakage in response to VEGFA was significantly reduced in Sdc4-/- animals (Fig. 6 F and G). Together, our data identifies a novel association between SDC4 and VE-Cadherin that is modulated by VEGFA. We further reveal that SDC4 is required for VEGFA-induced VE-Cadherin internalization and hyper-permeability.

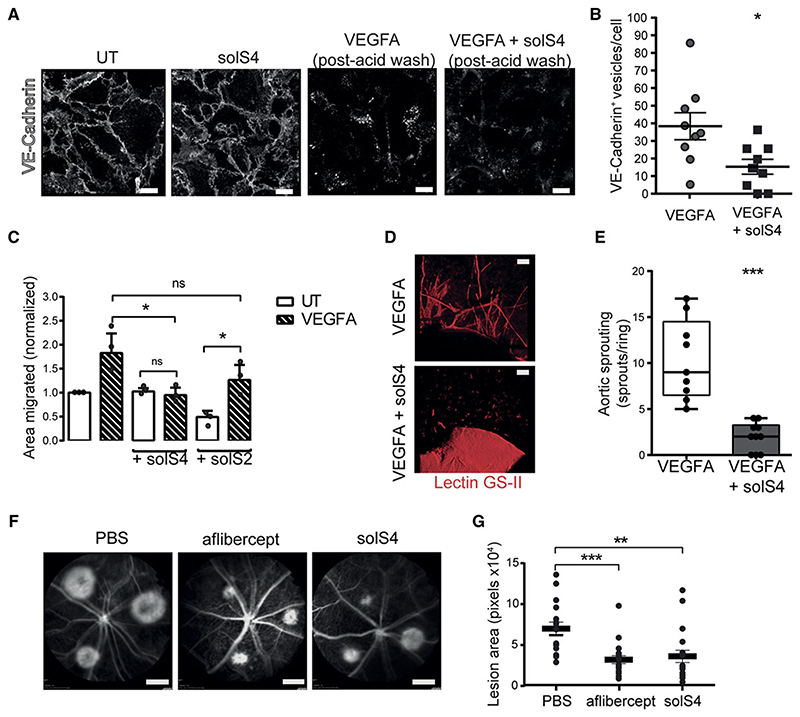

Soluble SDC4 reduces VEGFA induced VE-Cadherin internalization in a pre-clinical model of wet AMD

Lastly, we explored whether a soluble form of SDC4 (referred to as solS4, corresponding to the complete ectodomain of SDC4) could interfere with its pro-angiogenic role, in particular by disrupting the SDC4/VE-cadherin interaction. Using antibody-feeding approaches, we found that addition of solS4 to a monolayer of WT ECs prevented VEGFA-driven VE-Cadherin internalization (Fig. 7 A and B). Moreover, incubation of HUVECs with solS4 led to a reduction in PLA puncti between SDC4 and VE-Cadherin at EC junctions (Fig. S9 A), indicating that it may be disrupting the SDC4/VE-Cadherin complex. In addition, solS4 treatment also abolished VEGFA-driven EC migration. This is in contrast to ECs pre-treated with soluble SDC2 (solS2), the syndecan most structurally similar to SDC4, which maintained responsiveness to VEGFA (Fig. 7 C). As was the case with Sdc4-/- primary ECs, no impact on VEGFA signaling was observed in ECs stimulated with VEGFA in the presence or absence of solS4 (Fig. S9 B and C).We also observed reduced sprouting when aortic explants where treated with solS4 (Fig. 7 D and E). We next assessed whether solS4 could be therapeutically beneficial as an anti-angiogenic compound, by testing its efficacy in the laser-induced CNV model in comparison to Aflibercept (Eylea®, Regeneron), one of the current standard therapies for neovascular AMD patients. We found that a single injection of solS4 at day 0 post-laser injury reduced the angiogenic response at day 7 by almost 50% compared to vehicle (PBS) control, achieving similar anti-angiogenic activity to that of Aflibercept (Fig. 7 F and G). Altogether, these results indicate that delivery of solS4 decreases VE-Cadherin internalization, EC migration and reduces pathological angiogenesis in a pre-clinical murine model of neovascular AMD.

Figure 7. The extracellular core protein of SDC4 (solS4) inhibits VEGFA induced VE Cadherin internalization in vitro and choroidal neovascularization in vivo.

A, Confocal images of VE-Cadherin antibody ‘washout’ experiments. WT MLECs were washed with PBS and incubated with anti-VE-Cadherin antibody at 4 °C for 1 hour. Unbound antibody was washed away and cells stimulated with VEGFA (30 ng/ml) for 10 min with or without SolS4 (3.5 nM) at 37 °C to promote VE-Cadherin internalization followed by acid washing. VE-Cadherin (white). Scale bar, 20 μm. B. Images of MLECs treated with VEGFA and acid-washed were analyzed on Imaris software and VE-cadherin+ vesicles were counted and divided by the number of nuclei in the field of view. 9 images per condition were analyzed. n=3 Scale bar, 20 μm. C. HUVECs were scratched and incubated in serum-free media with or without VEGFA (20 ng/ml) and with or without SolS4 or solS2 (3.5 nM) for 16 hours. Migrated area was calculated by subtracting the final scratch area to the initial scratch area using ImageJ. n=3. D, Micrographs of C57BL6 murine aortic rings embedded in Collagen I and cultured as explants in VEGFA-containing medium with or without solS4 (3.5 nM) for 7 days. E, Manual quantification of angiogenic sprouts. (n=4, 5-15 rings/condition). Scale bar, 10 μm. F, Fundus fluorescein angiograms of WT animals at day 7 post laser induced CNV. Intravitreal injection of 1 μl of either PBS, Aflibercept (10 μg) or solS4 (100 ng) were performed at day 0 directly after laser burns were applied. Scale bar, 2.4 mm. G, The CNV lesion areas were quantified using ImageJ, each dot represents the average of 3 lesions per eye. n=7-9 animals per condition. Data are means and error bars indicate SEM in B, C and G and min and max values in E. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P<0.001.

Discussion

In this work we have performed detailed analysis of both post-natal and adult micro-vasculature in Sdc4-/- animals and found that vascular development is not affected by genetic deletion of SDC4. However, we showed in multiple murine disease models (diabetic retinopathy, wet AMD, melanoma and epidermal carcinogenesis) that SDC4 is required for robust pathological angiogenesis. This difference can be explained by SDC4 being differentially expressed during these two chronologically-distinct processes. In fact, our data reveals that SDC4 was the only syndecan member which was upregulated in models of pathological angiogenesis and importantly, its expression correlated with immature, pathological vessels formed in the retinas of diabetic retinopathy patients. The existence of hypoxia- 39 and inflammation-related regulatory elements (i.e. NF-κB 40 within the Sdc4 promoter region supports the concept that the expression and activity of this proteoglycan is driven by responses to hypoxia and inflammation, concomitant with pathological scenarios and important pro-angiogenic stimuli.

In the in vivo models described in this study, the primary driver of angiogenesis is VEGFA. We therefore explored the responses of Sdc4-/- cells and tissues in VEGFA stimulated angiogenesis assays (e.g. VEGFA-induced cell migration, tissue explant sprout formation) and found them to be impaired. This suggests that the defects we observed are linked to the angiogenic pathways driven by VEGFA. Importantly, normal angiogenic responses could be restored when SDC4 was expressed in Sdc4-/- cells and tissues. Our initial hypothesis was that SDC4 was acting as co-receptor between VEGFA and VEGFR2 through its HS chains. Recent studies suggest that this is the case for SDC4, VEGFC and VEGFR3 during pathological lymphangiogenesis 41. However, we discounted this hypothesis since, consistent with other studies, we observed no reduction in either phosphorylation of VEGFR2 or major signaling kinases downstream of this receptor (Erk1/2) in Sdc4-/- ECs treated with VEGFA. These findings are in agreement with the observation that VEGFA signaling requires SDC2, not SDC4, owing to differences in the levels of 6-O-sulphation on the HS chains of these molecules 20.

An excess of SDC4 achieved either by genetic means or via exogenous addition within proteo-liposomes leads to increased angiogenesis and improved therapeutic outcomes in models of ischemic injury and myocardial infarction23, 25, 42. These findings support the idea that upregulation of SDC4 expression is an important component in angiogenic responses. Furthermore, silencing of SDC4 leads to an attenuation of angiogenic responses in cell-based assays 43. Pro-angiogenic roles for SDC4 have been reported, particularly, in augmenting FGF2 signaling 23, 25, 42. The relationship between HS and FGF2 is well established and it is likely that SDC4 HS, when in abundance in these models, is responsible for enhanced FGF2 driven cellular responses. Both 2-O and 6-O sulphated HS can promote FGF2 signaling 44–47 whereas there is a distinct requirement for 6-O sulphation on HS chains for promoting the VEGFR2/VEGFA interaction20. The more promiscuous HS binding requirements of FGF2 mean there is likely to be redundancy in the system and other HSPGs could be the source of the HS required to engage FGF2 in Sdc4-/- animals which may explain the lack of developmental angiogenic defects in these mice. In common with other studies we did not observe an effect on FGF2 induced angiogenesis in Sdc4-/- animals 20. Collectively this suggests that, in the absence of SDC4, VEGFA/VEGR2 signaling is unperturbed and this led us to speculate that SDC4 may have a role in pathological angiogenesis and is regulated by the VEGFA/VEGFR2 axis.

We demonstrated that SDC4 localizes to EC cell-cell contacts and co-localizes with the junctional protein VE-Cadherin. This is in keeping with recent proteomic studies in which SDC4 was found to be associated with EC junctional proteins 48. EC adherens junctions are a complex assemblage of both junctional and cytoskeletal proteins and many of the molecules involved also constitute focal adhesion complexes, in which SDC4 is a known component 49. Furthermore, numerous studies have identified roles for SDC4 in cytoskeletal rearrangements and changes in the actin cytoskeleton in a variety of cell types, including ECs 43. The disassembly of these structures is a critical early step in angiogenesis 50 and we showed that ECs null for SDC4 exhibited defective VE-Cadherin internalization away from junctions in response to VEGFA stimulation. This was also reflected in defective vascular permeability responses in vivo. Our data revealed that under basal conditions SDC4 is in complex with VE-Cadherin, and this complex is disrupted rapidly following VEGFA stimulation. The presence of SDC4 in this complex is clearly an important precursor for efficient VE-Cadherin trafficking since when SDC4 is absent (e.g. in Sdc4-/- animals or ECs) this process was inhibited substantially. The phosphorylation status of SDC4, specifically on residue Y180, is also important in regulating this process. Mutant forms of SDC4 in which this residue is mutated to Alanine did not complex effectively with VE-Cadherin and failed to restore efficient VE-Cadherin trafficking in Sdc4-/- ECs. Conversely, phosphomimetic mutants complexed with VE-Cadherin were capable of restoring VEGFA driven VE-Cadherin internalization. We therefore speculate that in response to VEGFA, SDC4 is dephosphorylated leading to a disruption of the SDC4/VE-Cadherin complex. Phosphorylation of this residue by c-SRC is an important control point of integrin trafficking 37 and it is not inconceivable that this may also be linked to the findings reported here, since β1 integrin activation state influences VE-cadherin localization 51, 52. Moreover, the expression of SDC4 is required for the expression of junctional Cadherin-11 in fibroblasts 53 and in calcium signaling 54. These studies, in conjunction with our findings suggests that SDC4 may be involved with other members of the Cadherin family in other cell types.

Our studies indicate that SDC4 is essential for efficient VE-Cadherin internalization in response to VEGFA and we show that the delivery of soluble SDC4 inhibits this process. This is in contrast other reported observations in which thrombin-cleaved fragments of both SDC3 and SDC4 extracellular core protein promote EC junctional reorganization in cultured ECs55. Regulatory sequences within syndecan extracellular core proteins have been identified in all 4 syndecan family members and they can impact on EC behaviour56. The soluble form of SDC4 used in this study comprises the entire extracellular core protein. A possible explanation for the disparity in these observations is that fragments of SDC4 ectodomain may have different properties to the full-length version. In addition, there may also be possible synergism between SDC4 and SDC3 ectodomain fragments, the full length of which can also modulate angiogenesis57.

We also show that soluble SDC4 can reduce both VEGF-driven angiogenesis and hyper-permeability in vivo. Neovascularization and subsequent vascular leakage from angiogenic blood vessels is an important and exacerbating factor in neovascular eye disease 58. Furthermore, angiogenesis blocking strategies are in use for the treatment of a number of tumors. The most common therapeutic options involve targeting VEGFA either using antibodies or receptor-mimicking recombinant proteins. Although successful, these therapies are not without limitations, particularly with regard to patient non-response in ophthalmic indications and a significant side-effect profile when administered systemically in treating cancer 59, 60. We demonstrate that SDC4 acts downstream of the VEGFA/VEGFR2 axis and application of a solSDC4 while disrupting the SDC4/VE-cadherin interaction has negligible impact on the phosphorylation status of key signaling kinases within ECs. Potentially therefore at least in the instances where anti-angiogenic therapies are administered systemically, fewer adverse effects might be observed in targeting SDC4/VE-Cadherin, particularly as SDC4 seems only to be upregulated on ECs during pathological scenarios. The rationale for targeting SDC4 for therapeutic benefit has been demonstrated in other disease models. Antibodies against SDC4 have been shown to block SDC4 dimerization in response to IL-1ß stimulation, and these have a positive impact in models of inflammatory arthritis61. Furthermore, use of recombinant proteins derived from SDC4 binding partners have also proven efficacious in disease models. The Ig1 and 2 repeats from the protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor sigma (PTPRρ) have also been shown to inhibit signaling of this receptor resulting in improved outcomes in collagen-induced arthritis models62. Whether these reagents could be used to target pathological angiogenesis remains unexplored, but strongly support the idea that SDC4 could be targeted for therapeutic benefit in disease settings.

Taken together, our study identifies SDC4 as an essential regulatory component in VEGFA-induced VE-cadherin internalization from EC junctions during pathological angiogenesis. We believe these results provide significant further insight into the molecular events controlling neovascularization and hyper-permeability responses in diseases. The formation of abnormal blood vessels is a feature of cancer, neovascular eye diseases and chronic inflammatory conditions, which implies that SDC4 blocking strategies may have the potential to be applied in these contexts to either improve or offer a more selective alternative to existing therapies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Syndecan-4 null mice are protected in models of neovascular eye diseases and skin tumor models due to defective angiogenesis.

Syndecan-4 expression is upregulated during pathological angiogenesis in mice and is selectively enriched in immature blood vessels in the retinas of diabetic retinopathy patients.

A pool of Syndecan-4 resides at endothelial cell junctions, and has no role in VEGFA/VEGFR2 signaling, but rather, is downstream of this interaction.

Syndecan-4 null animals and cells show inefficient VEGFA-induced VE-Cadherin internalization and this is reflected in vivo by aberrant vascular permeability responses to VEGFA.

a). Acknowledgements

GDR, JRW, EC and TAHJ designed the experiments; GDR, JRW, EC, TAHJ, MV, HU-J interpreted the results; GDR and JRW wrote the manuscript; GDR performed choroid and aortic ring assay, matrigel plug assay, lentivirus production (JRW and SA designed and generated the cDNAs), cell migration assay, VE-Cadherin internalization assay, permeability assay, immunofluorescence staining, vascular bed staining, SDS-Page and western blotting, flow cytometry analysis; EC, GDR, SEL performed the laser induced CNV and in conjunction with MV and HU-J performed the analysis of neonatal retinal development; MV, HU-J performed the OIR experiments and analysis of human PDR membranes. MV, UM, LP and TAHJ performed two-stage carcinogenesis model and analyses. We thank Marianne Karlsberg and Terhi Tuomola for practical support.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The data and reagents that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

b). Sources of funding

JRW and GDR gratefully acknowledge funding from Arthritis Research UK (Grant No. 19207 and 21177), Fight for Sight (Grant No. 1558/59), Barts and The London Charity (Grant No. MGU0313), Queen Mary Innovations, William Harvey Research Foundation, The Macular Society and the Dunhill Medical Trust (Grant No. RPGF1906\173). TAHJ, MV and HU-J gratefully acknowledge funding from the Academy of Finland, Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Instrumentarium Research Foundation, Diabetes Wellness Foundation (DWF), Pirkanmaa Hospital District Research Foundation, Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. JWB is a NIHR Research Professor.

References

- 1.Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayson GC, Kerbel R, Ellis LM, Harris AL. Antiangiogenic therapy in oncology: Current status and future directions. Lancet. 2016;388:518–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amadio M, Govoni S, Pascale A. Targeting vegf in eye neovascularization: What’s new? A comprehensive review on current therapies and oligonucleotide-based interventions under development. Pharmacological Research. 2016;103:253–269. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teleanu RI, Chircov C, Grumezescu AM, Teleanu DM. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic strategies for cancer treatment. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019;9 doi: 10.3390/jcm9010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. Vegf receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaengel K, Niaudet C, Hagikura K, Lavina B, Muhl L, Hofmann JJ, Ebarasi L, Nystrom S, Rymo S, Chen LL, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor s1pr1 restricts sprouting angiogenesis by regulating the interplay between ve-cadherin and vegfr2. Developmental cell. 2012;23:587–599. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentley K, Franco CA, Philippides A, Blanco R, Dierkes M, Gebala V, Stanchi F, Jones M, Aspalter IM, Cagna G, et al. The role of differential ve-cadherin dynamics in cell rearrangement during angiogenesis. Nature cell biology. 2014;16:309–321. doi: 10.1038/ncb2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Ehling M, Kato K, Kanai K, van Lessen M, Frye M, Zeuschner D, Nakayama M, Vestweber D, Adams RH. Integrin beta1 controls ve-cadherin localization and blood vessel stability. Nature communications. 2015;6:6429. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao J, Ehling M, Marz S, Seebach J, Tarbashevich K, Sixta T, Pitulescu ME, Werner AC, Flach B, Montanez E, et al. Polarized actin and ve-cadherin dynamics regulate junctional remodelling and cell migration during sprouting angiogenesis. Nature communications. 2017;8:2210. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmeliet P, Lampugnani MG, Moons L, Breviario F, Compernolle V, Bono F, Balconi G, Spagnuolo R, Oosthuyse B, Dewerchin M, et al. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the ve-cadherin gene in mice impairs vegf-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashikari-Hada S, Habuchi H, Kariya Y, Kimata K. Heparin regulates vascular endothelial growth factor165-dependent mitogenic activity, tube formation, and its receptor phosphorylation of human endothelial cells. Comparison of the effects of heparin and modified heparins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:31508–31515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson CJ, Mulloy B, Gallagher JT, Stringer SE. Vegf165-binding sites within heparan sulfate encompass two highly sulfated domains and can be liberated by k5 lyase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:1731–1740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie M, Li JP. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan - a common receptor for diverse cytokines. Cellular signalling. 2019;54:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexopoulou AN, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR. Syndecans in wound healing, inflammation and vascular biology. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2007;39:505–528. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couchman JR. Transmembrane signaling proteoglycans. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2010;26:89–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gondelaud F, Ricard-Blum S. Structures and interactions of syndecans. The FEBS journal. 2019;286:2994–3007. doi: 10.1111/febs.14828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afratis NA, Nikitovic D, Multhaupt HA, Theocharis AD, Couchman JR, Karamanos NK. Syndecans - key regulators of cell signaling and biological functions. The FEBS journal. 2017;284:27–41. doi: 10.1111/febs.13940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corti F, Wang Y, Rhodes JM, Atri D, Archer-Hartmann S, Zhang J, Zhuang ZW, Chen D, Wang T, Wang Z, et al. N-terminal syndecan-2 domain selectively enhances 6-o heparan sulfate chains sulfation and promotes vegfa165-dependent neovascularization. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1562. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echtermeyer F, Streit M, Wilcox-Adelman S, Saoncella S, Denhez F, Detmar M, Goetinck P. Delayed wound repair and impaired angiogenesis in mice lacking syndecan-4. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;107:R9–r14. doi: 10.1172/JCI10559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishiguro K, Kadomatsu K, Kojima T, Muramatsu H, Nakamura E, Ito M, Nagasaka T, Kobayashi H, Kusugami K, Saito H, et al. Syndecan-4 deficiency impairs the fetal vessels in the placental labyrinth. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:539–544. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1081>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie J, Wang J, Li R, Dai Q, Yong Y, Zong B, Xu Y, Li E, Ferro A, Xu B. Syndecan-4 over-expression preserves cardiac function in a rat model of myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corti F, Finetti F, Ziche M, Simons M. The syndecan-4/protein kinase cα pathway mediates prostaglandin e2-induced extracellular regulated kinase (erk) activation in endothelial cells and angiogenesis in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12712–12721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das S, Monteforte AJ, Singh G, Majid M, Sherman MB, Dunn AK, Baker AB. Syndecan-4 enhances therapeutic angiogenesis after hind limb ischemia in mice with type 2 diabetes. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:1008–1013. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, Kostyk SK, D’Amato R, Sullivan R, D’Amore PA. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1994;35:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vähätupa M, Jääskeläinen N, Cerrada-Gimenez M, Thapa R, Järvinen T, Kalesnykas G, Uusitalo-Järvinen H. Oxygen-induced retinopathy model for ischemic retinal diseases in rodents. J Vis Exp. 2020 doi: 10.3791/61482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stahl A, Chen J, Sapieha P, Seaward MR, Krah NM, Dennison RJ, Favazza T, Bucher F, Lofqvist C, Ong H, et al. Postnatal weight gain modifies severity and functional outcome of oxygen-induced proliferative retinopathy. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:2715–2723. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vahatupa M, Prince S, Vataja S, Mertimo T, Kataja M, Kinnunen K, Marjomaki V, Uusitalo H, Komatsu M, Jarvinen TA, Uusitalo-Jarvinen H. Lack of r-ras leads to increased vascular permeability in ischemic retinopathy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57:4898–4909. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filler RB, Roberts SJ, Girardi M. Cutaneous two-stage chemical carcinogenesis. CSH Protoc. 2007;2007:pdb.prot4837. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May U, Prince S, Vahatupa M, Laitinen AM, Nieminen K, Uusitalo-Jarvinen H, Jarvinen TA. Resistance of r-ras knockout mice to skin tumour induction. Scientific reports. 2015;5:11663. doi: 10.1038/srep11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vahatupa M, Pemmari T, Junttila I, Pesu M, Jarvinen TAH. Chemical-induced skin carcinogenesis model using dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and 12-o-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (dmba-tpa) Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2019 doi: 10.3791/60445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vähätupa M, Järvinen TAH, Uusitalo-Järvinen H. Exploration of oxygen-induced retinopathy model to discover new therapeutic drug targets in retinopathies. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:873. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossniklaus HE, Kang SJ, Berglin L. Animal models of choroidal and retinal neovascularization. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2010;29:500–519. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Losada J, Balmain A. Stem-cell hierarchy in skin cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2003;3:434–443. doi: 10.1038/nrc1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arokiasamy S, Balderstone MJM, De Rossi G, Whiteford JR. Syndecan-3 in inflammation and angiogenesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:3031. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan MR, Hamidi H, Bass MD, Warwood S, Ballestrem C, Humphries MJ. Syndecan-4 phosphorylation is a control point for integrin recycling. Dev Cell. 2013;24:472–485. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gavard J, Gutkind JS. Vegf controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the beta-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of ve-cadherin. Nature cell biology. 2006;8:1223–1234. doi: 10.1038/ncb1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujita N, Hirose Y, Tran CM, Chiba K, Miyamoto T, Toyama Y, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Hif-1-phd2 axis controls expression of syndecan 4 in nucleus pulposus cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014;28:2455–2465. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okuyama E, Suzuki A, Murata M, Ando Y, Kato I, Takagi Y, Takagi A, Murate T, Saito H, Kojima T. Molecular mechanisms of syndecan-4 upregulation by tnf-alpha in the endothelium-like eahy926 cells. Journal of biochemistry. 2013;154:41–50. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johns SC, Yin X, Jeltsch M, Bishop JR, Schuksz M, El Ghazal R, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Alitalo K, Fuster MM. Functional importance of a proteoglycan coreceptor in pathologic lymphangiogenesis. Circulation research. 2016;119:210–221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang E, Albadawi H, Watkins MT, Edelman ER, Baker AB. Syndecan-4 proteoliposomes enhance fibroblast growth factor-2 (fgf-2)-induced proliferation, migration, and neovascularization of ischemic muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117885109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cavalheiro RP, Lima MA, Jarrouge-Bouças TR, Viana GM, Lopes CC, Coulson-Thomas VJ, Dreyfuss JL, Yates EA, Tersariol ILS, et al. Coupling of vinculin to factin demands syndecan-4 proteoglycan. Matrix Biol. 2017;63:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kariya Y, Kyogashima M, Suzuki K, Isomura T, Sakamoto T, Horie K, Ishihara M, Takano R, Kamei K, Hara S. Preparation of completely 6-o-desulfated heparin and its ability to enhance activity of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25949–25958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pye DA, Vives RR, Turnbull JE, Hyde P, Gallagher JT. Heparan sulfate oligosaccharides require 6-o-sulfation for promotion of basic fibroblast growth factor mitogenic activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22936–22942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.22936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maccarana M, Casu B, Lindahl U. Minimal sequence in heparin/heparan sulfate required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23898–23905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jastrebova N, Vanwildemeersch M, Lindahl U, Spillmann D. Heparan sulfate domain organization and sulfation modulate fgf-induced cell signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26842–26851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kostelnik KB, Barker A, Schultz C, Mitchell TP, Rajeeve V, White IJ, Aurrand-Lions M, Nourshargh S, Cutillas P, Nightingale TD. Dynamic trafficking and turnover of jam-c is essential for endothelial cell migration. PLoS biology. 2019;17:e3000554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woods A, Couchman JR. Syndecan 4 heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a selectively enriched and widespread focal adhesion component. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:183–192. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dejana E, Giampietro C. Vascular endothelial-cadherin and vascular stability. Current opinion in hematology. 2012;19:218–223. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283523e1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pulous FE, Grimsley-Myers CM, Kansal S, Kowalczyk AP, Petrich BG. Talin-dependent integrin activation regulates ve-cadherin localization and endothelial cell barrier function. Circulation research. 2019;124:891–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hakanpaa L, Kiss EA, Jacquemet G, Miinalainen I, Lerche M, Guzmán C, Mervaala E, Eklund L, Ivaska J, Saharinen P. Targeting β1-integrin inhibits vascular leakage in endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E6467–e6476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722317115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gopal S, Multhaupt HAB, Pocock R, Couchman JR. Cell-extracellular matrix and cell-cell adhesion are linked by syndecan-4. Matrix Biol. 2017;60-61:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gopal S, Sogaard P, Multhaupt HA, Pataki C, Okina E, Xian X, Pedersen ME, Stevens T, Griesbeck O, Park PW, Pocock R, et al. Transmembrane proteoglycans control stretch-activated channels to set cytosolic calcium levels. The Journal of cell biology. 2015;210:1199–1211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jannaway M, Yang XY, Meegan JE, Coleman DC, Yuari SY. Thrombin-cleaved syndecan-3/-4 ectodomain fragments mediate endothelial barrier dysfunction. Plos One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Rossi G, Whiteford JR. Novel insight into the biological functions of syndecan ectodomain core proteins. Biofactors. 2013;39:374–382. doi: 10.1002/biof.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Rossi G, Whiteford JR. A novel role for syndecan-3 in angiogenesis. F1000Res. 2013;2:270. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-270.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soubrane G. Macular edema of choroidal origin. Developments in ophthalmology. 2017;58:202–219. doi: 10.1159/000455282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadda SR, Guymer R, Mones JM, Tufail A, Jaffe GJ. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor use and atrophy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Systematic literature review and expert opinion. Ophthalmology. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaszai J, Schmidt MHH. Trends and challenges in tumor anti-angiogenic therapies. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8091102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Godmann L, Bollmann M, Korb-Pap A, Konig U, Sherwood J, Beckmann D, Muhlenberg K, Echtermeyer F, Whiteford J, De Rossi G, et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of syndecan-4 dimerisation reduces interleukin (il)-1 receptor trafficking and signalling. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:481–489. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doody KM, Stanford SM, Sacchetti C, Svensson MND, Coles C, Mitakidis N, Kiosses WB, Bartok B, Fos C, Cory E, Sah RL, et al. Targeting phosphatasedependent proteoglycan switch for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.