Abstract

This paper will explore the concept of ‘fail safe’ ethics in the FEM PrEP trial, and the practice of research and ethics on the ground. FEM-PrEP examined the efficacy of PrEP in African women after promising outcomes in research conducted with MSM. This was a hugely optimistic time and FEM-PrEP was mobilised using rights-based ethical arguments that women should have access to PrEP.

This paper will present data collected during an ethnographic study of frontline research workers involved in FEM-PrEP. During our discussions, ‘fail-safe’ ethics emerged as concept that encapsulated their confidence that their ethics could not fail. However, in 2011, FEM-PrEP was halted and deemed a failure. The women involved in the study were held responsible because contrary to researcher’s expectations they were not taking the oral PrEP being researched.

This examination of FEM-PrEP will show that ethical arguments are increasingly deployed to mobilise, maintain and in some cases stop trials in ways which, at times, are superseded or co-opted by other interests. While promoting the interests of women, rights-based approaches are argued to indirectly justify the continuation of individualised, biomedical interventions which have been problematic in other women-centred trials. In this examination of FEM-PrEP, the rights-based approach obscured: ethical concerns beyond access to PrEP; the complexities of power relationships between donor and host countries; the operations of the HIV industry in research-saturated areas and the cumulative effect of unfilled expectations in HIV research and how this has shaped ideas of research and ethics.

Keywords: failure, fieldworkers, PrEP, women, Africa

Introduction

If we knew the science would work I don’t think that we would be doing this [research] …but the ethics part of this [FEM-PrEP] is absolutely fail-safe.

(FEM-PrEP Community Interviewer, June 2009)

This paper will explore the concept of ethics as being ‘fail-safe’, as described in the quote above. This quote was obtained during an ethnographic examination of frontline research workers involved in the FEM-PrEP study. The key questions asked of these frontline research workers were focused on capturing their various perspectives and positions on what constituted ethics. During these discussions, the description of ethics as being fail-safe emerged as an important concept. The Oxford English Dictionary provides two definitions of the term fail-safe (Oxford English Dictionary 2015). Fail-safe refers to causing a piece of machinery to revert to a safe condition in the event of a breakdown or malfunction – which prevents or mitigates unsafe consequences in the event of mechanical or systematic failure. The term fail-safe also refers to something that is unlikely or unable to fail. It is argued that, taken together, both definitions of fail-safe provide a means of understanding the increasing role and value attached to ethics and, in the case of the FEM-PrEP trial, a certain confidence in its conduct as being motivated by the pursuit of what is perceived as a human right pushed forward by an infallible system beyond scrutiny or improvement. Furthermore, the international advocates for the clinical trial of FEM-PrEP may have felt that as its ethics was unquestionably right that there no need to operate beyond the existing framework because to be ‘fail-safe’ was also to be fail-proof.

When in April 2011, the FEM-PrEP study was halted, it was widely described as a failure by the international media (Mascolini 2012). The discussion of ‘fail-safe’ ethics among the FEM-PrEP frontline research workers in western Kenya took on greater meaning in light of this event. This paper will consider the roles that ethics has played in the accounts of failure and success of the FEM-PrEP trials, and argue that the ethics of research practice as discussed before, during and after the trial are by no means absolute, and that a full consideration of the range of views and positions of ethics can be valuable in fortifying the integrity of the research and its outcomes.

The FEM-PrEP study was an investigation of the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in African women from 2009 to 2011. It is one of a number of high-profile HIV research projects in the last ten years, aimed at women and conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa, which have been considered a failure (Montgomery 2012, McNeil 2015, Susser 2015). In all cases, the ethical arguments in support of research into the transmission of the HIV virus have been centred on the rights of women to have access to these pharmaceutical products. For instance, in the case of FEM-PrEP it was argued that it would be unethical to withhold PrEP from African women, as they were disproportionately affected by HIV (FHI 2011, Haire and Kaldor 2013, Hankins and Dybul 2013). Notwithstanding this argument, it has been suggested that promoting other forms of ethical concerns, such addressing economic injustice and solely focusing on access to pharmaceutical products has also obscured the political and commercial interests that are vested exclusively on a biomedical and individualised approach to treating and preventing HIV (Petryna, Andrew, and Arthur 2006, Rosengarten and Michael 2009, Kenworthy and Bulled 2013). Yet, neither the strength of these counterarguments, or the apparent failure of FEM-PrEP have altered the dominant ethical position – or direction – on its availability (Hankins and Dybul 2013, Cowan and Macklin 2014).

It is argued here that because access to PrEP has been positioned almost exclusively as a human right, with all the accompanying hopes and expectations of a cure for HIV, the concept of access and subsequent interventions surrounding PrEP have become ‘immune’ to failure, even when the women involved in testing the drug suggested that meeting their basic needs and material concerns were their priority. There are a number of powerful arguments underpinning access to PrEP. To summarise, the typical expression of this argument is that if the most high risk populations of HIV infection — including African women and men who have sex with men — have consistent access to PrEP and are able to use it correctly then it will dramatically reduce levels of transmission. The perception is that this can completely alter the face of the epidemic which has become a humanitarian crisis (Lange 2005). On this assumption, the argument was proposed that these populations have a human right to access to PrEP (Hankins and Dybul 2013).

Rights-based arguments for PrEP

This rights-based approach, which became popular in development programmes in the late 1990s and early 2000s, was interpreted differently by various organisations, and what it means in practice is the subject of ongoing debate (Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall 2004). Often it adopts a two-pronged approach that focuses on being grounded and integrated into community capacity building programmes that enables people (e.g. women) to claim their rights. It also seeks to hold government agencies accountable for ensuring that these rights are protected for vulnerable populations, and that once made explicit their obligations are fulfilled. Therefore, having identified women as disproportionately affected by HIV, this rights-based approach has provided the ethical basis for justifying the premium placed on the women-centred programmes in HIV/AIDS and has supported arguments that women have a right to PrEP (Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall 2004, Cornwall, Harrison and Whitehead 2007).

This paper argues that this ethical argument operates as a device which not only curtails the discussion of any other practical, logistical and ethical concerns but it also acts as a ‘fail-safe’ device, which ensures that, even in cases such as FEM-PrEP where one of the targeted populations for PrEP did not adhere to the trial researching the efficacy of the drug, resulting in the study being halted before completion, the investments and roll-out of PrEP continue to be justified because the dominant rights-based ethical arguments underpinning PrEP override such events.

While rights-based ethical arguments can be regarded as a means of promoting and protecting individual rights and re-politicising programmes through government involvement, they are increasingly playing an instrumentalised role in research, in facilitating individual-centred biomedical interventions – which raise ethical concerns and challenges other than and beyond a right to access (Meier, Brugh and Halima 2012). Not all observers of rights-based approaches in practice are convinced that they promote and protect individual rights, arguing instead that they are a form of ‘Emperor’s new clothes’ used by the international donors and funders to further their interests and neo-colonial relationships with those in the Global South (Uvin 2002, Harper and Parker 2014). These ideas will be examined further in this paper.

The paper begins by providing some background information to FEM-PrEP by focusing on some of the expectations of the trial, based on the results on a previous prophylaxis study among men who have sex with men (MSM). Next, I will present my data, first by explaining my methods, and then by exploring the accounts of the fieldworkers and other frontline research workers involved in the day-to-day function of FEM-PrEP. Rather than taking ideas of failure and ethics as objective accounts, this discussion of FEM-PrEP is interested in exploring these concepts from the different vantage points of some of the actors involved in the trial. I intend to present some of the different ethical positions presented before, during and after the conduct of the FEM-PrEP study with the aim of elucidating some of the interests that those ethical positions promote. Examination of the FEM-PrEP study will show that ethical arguments are increasingly deployed to mobilise, maintain and in some cases stop trials in ways which, at times, are superseded or co-opted by other interests.

Background

The International AIDS Society Conference in Cape Town in 2009 was a defining moment in the history of HIV research and intervention. It was at this meeting that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) cemented its position as one of the key HIV prevention approaches. PrEP uses anti-retrovirals (ARVs) and is taken by a HIV negative person prior to HIV exposure to limit infection. At the conference, the interim results of the iPrEx study (also known as the Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men trial) were shared. The study, which was a double blind placebo controlled trial, started in June of 2007 and involved 2499 participants in six countries (Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, South Africa, Thailand and United States). The iPrEx study was the first trial to report that PrEP, in the form of a pill, was effective in treating HIV infections and reducing HIV infection risk in men who had sex with men (MSM).

However, even before the iPrEx trial results were announced, policymakers, at the conference, contemplated how quickly it could be incorporated into the arsenal of the HIV prevention strategies (Kenworthy and Bulled 2013). For instance, Stephen Becker, of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, warned of consequences of an approach that relied on ‘wait[ing] until clinical proof of concept [that PrEP is effective] has occurred’ (Cairns 2009). He urged the audience that comprised research scientists, patient communities, practitioners and social scientists that ‘[W]e need to investigate delivery channels, how we engage with policymakers, and how we will market these approaches now’ [emphasis added] (Cairns 2009). The clinical success of PrEP represented a ‘defining moment in the global AIDS response’ (Karim and Karim 2011) shaping expectations for the future successes and plans for its rapid inclusion in the HIV prevention arsenal. However, these hopes predated the demonstrations of clinical success and in the meantime it was argued that other high risk groups also urgently needed PrEP (FHI 2011).

When the iPrEx results were reported in November of 2010, it was a mere formality which justified the preceding excitement. The study found that daily use of the antiretroviral drug combinations emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir 300 mg (FTC/TDF), also known as Truvada, provided 99% protection against HIV infection in MSMs, when taken seven days a week. It had demonstrated a reduction in infections among MSM trial participants who took a daily dosage of Truvada as a preventative treatment: 44% overall and 92% among those with biological evidence of regimen adherence (Grant et al. 2010). The study team argued that: ‘[W]e showed that such subjects with a high risk of exposure to HIV can be mobilized to participate in prevention initiatives and that preexposure prophylaxis is effective for slowing the spread of HIV in this population’ (Grant et al. 2010, 9).

This was a hugely optimistic time in the research of HIV (Cohen 2011). iPrEx was heralded as a success and was seen to be responsible for drastically raising the level of expectation of how PrEP could change the HIV treatment as prevention landscape. Even before its completion, there were arguments that the ethical course of action would be to see PrEP as a human right for groups deemed to be at high risk of HIV transmission including sex workers, young women people and injecting drug-users (Grant et al. 2010, Hankins and Dybul 2013). In Sub-Saharan Africa, women have long been argued to not only be of the highest risk of infection (Heise and Elias 1995, Annan 2002), and also that a targeted approach on women was also the key to HIV eradication (FHI 2011). These arguments have underpinned numerous HIV strategies on the continent (Heise and Elias 1995, Montgomery 2012) and were once again mobilised in the case of extending the iPrEx study to African women, this time supported by a rights-based approach where women’s access to ARVs was not seen as merely a development issue or an issue of national concern, but also as a matter of social justice and dignity, requiring international accountability and responsibility (FHI 2011).

Women need PrEP too

Although Truvada did not contain any chemical properties tailored exclusively for women, the iPrEx study was renamed and rebranded to reflect its exclusive focus on African women, it became FEM-PrEP. Heralded as having the potential to be the ‘the ultimate female controlled method’ (Rosengarten and Michael 2009, 1054), the expectation was that FEM-PrEP would ‘answer important questions on the character of PrEP by obtaining data on its multiple contingencies and subjecting these to a risk/benefit calculus’ (Rosengarten and Michael 2009, 1054). The FEM-PrEP trial was conducted with the expectation that ‘PrEP’s identity was settled and, with that, specific sorts of policy, programmes and so on are likely to follow’ (Rosengarten and Michael 2009, 1054). Its trial was designed to assess whether a daily dose of Truvada was as safe and effective at preventing HIV infection among high-risk women as the MSM in the iPrEx study. Women were defined as being ‘high risk’ of HIV infection if they had had sex at least once in the past fortnight or had had sex with more than one sexual partner in the past month (FHI 2011). FEM-PrEP was a Phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled trial that was conducted in Bondo, western Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania. In these locations, 2120 women were assigned to receive either Truvada or a placebo containing no active drug, for approximately a year, with monthly clinic visits for approximately 14 months. Participants who acquired HIV, or became pregnant during the conduct of FEM-PrEP, stopped taking the study pill but were monitored in the trial for another 12 months.

The international FEM-PrEP study team have argued that the FEM-PrEP participants were asked to regularly adhere to the study product of either an investigational HIV prevention drug or a placebo (Corneli et al. 2015). At their monthly study visit, participants were reminded that the trial aimed to determine the effectiveness of the oral PrEP in HIV prevention. The trial participants were also counselled at each study visit to use HIV risk reduction methods of known effectiveness, such as condoms and partner reduction, because it was not known whether FTC/TDF could prevent HIV acquisition and because they may have been randomised to the placebo, which could not protect against HIV. Yet, despite these terms and conditions apparently being made explicit throughout the conduct of the trial it was closed early, in April 2011. Although 100% of the women disclosed that they were using some form of contraception – which was provided free by the study – 9% became pregnant during the study. Across all the sites there were 56 new infections of HIV (equally distributed across Truvada and the placebo arm). Given the enormous expectations of this trial, these results were hugely disappointing, so much so, that less than one year after the successful results of iPrEx were officially published, the FEM-PrEP study findings were deemed a failure (Mascolini 2012, Carins 2013).

There were a number of reasons presented for its failure, which are worthy of further examination before presenting the data from my work with the frontline research workers involved in FEM-PrEP. These explanations have been presented by the funders and international institutions that promoted FEM-PrEP. In the aftermath of the trial’s premature closure it became clear that this result was due to participants not taking the pill. This prompted a shift in how these vulnerable women, at high-risk of the disease, were discussed and the further roll-out of PrEP has been justified.

Making sense of failure

Discussing FEM-PrEP as a failure is a subject of ongoing debate as many argue that in the cases where women did adhere to the study protocol, the drug was shown to be effective at reducing HIV transmission (Walker and Burton 2008, Horn 2012, Corneli et al. 2015). Therefore, under these circumstances the study was in fact a success. In addition, there are those who argue that not only was the conduct of FEM-PrEP a success, including the oversight and monitoring of the study, and its rights-based approach in extending the PrEP to women were some of the ways in which it was seen to have been successful (Cowan and Macklin 2014, Corneli et al. 2015).

However, for those who adhere to the view that the FEM-PrEP study failed, the lack of adherence to the study protocol, on the part of the African women study participants, was regarded as the main explanation (Horn 2012). A number of possible reasons for why this failure took place have been proposed. These include suggestions that participants were not interested in the trial per se but rather that the trial represented a means of gaining access to scarce material benefits (Mascolini 2012) and regular HIV tests (Carins 2013) during their participation. An additional explanation was, unlike the male participants in the iPrEx trial, that the women in these contexts were unaccustomed to taking medication and for that reason found adhering to a trial which required that they take a pill, consistently, every day for a year too demanding (Wong, Parker et al. 2013, Corneli et al. 2015).

Having presented some of the background literature on how FEM-PrEP has been discussed and understood in the literature, the method of data collection in my work will be explained before presenting frontline research workers’ insights on the study.

Methods

The findings presented in this article are based on qualitative and ethnographic examinations of fieldworkers and other frontline research workers involved in biomedical research projects in western Kenya 2007 and 2011.

FEM-PrEP was one of five studies examined and only the data from that project are presented in this paper. During the fieldwork, which mostly occurred before the final results of FEM-PrEP were known, the everyday practices of locally recruited frontline research workers such as fieldworkers, community liaison officers and interviewers were examined. These members of staff were Kenyan, mainly from Bondo or the surrounding area and were usually recruited in close proximity to the research clinic.

While it is difficult to anonymise the institutions involved, information pertaining to the individual members of staff has been removed to protect their identities. The operations of FEM-PrEP in western Kenya represented only one location in the trial’s conduct. Their findings presented here should not be seen to be specific only to this location, and can be regarded as being of general relevance to the conduct of similar trials elsewhere.

Research methods

This study involved several different methods, including observations, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. Frontline research workers were accompanied during their working day. This involved observing data collection interactions between staff and research participants. While their roles varied, the close proximity of frontline research workers to participants was a common feature of their work. In seeking to capture their views on their work and ethics, this article accepts that there are numerous ways to perceive, understand and discuss these concepts (Stanley and Wise 1993). Within this interpretative approach, informants’ accounts of ethics are not treated as ‘right’ or ‘true’ but rather as valuable insights of particular views and positions on ethics.

In addition to being observed, frontline research workers were involved in focus group discussions (FGDs). These were employed to illuminate some of the dominant themes in relation to the research question. FGDs served as an introduction to the aims of my work and were used only with research staff. All FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed and were approximately 90 minutes in length. Among the FEM-PrEP staff, there are two FGDs held with junior researchers such as community interviewers, involving eight members of staff in total. Additionally, in-depth interviews were used to gain further insights into some of the broad themes that emerged from the FGDs and observations. I conducted eight in-depth interviews with a range of both junior and senior staff, ranging from 45 minutes to 3 hours. During this type of interview, particular attention was given to contrasting views to those expressed in FGDs and to gaining deeper and more nuanced accounts. In addition, when the results of FEM-PrEP were announced I arranged for a 45 minute Skype conversation with four members of the research team. This was primarily to capture their feelings on the results of the FEM-PrEP after they had been publicised.

Findings

Involving women in FEM-PrEP

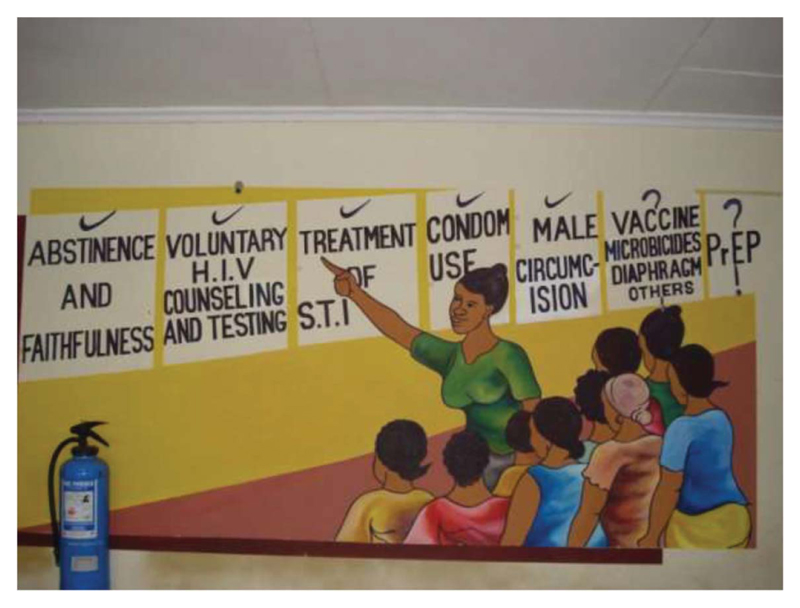

During my time examining the views and position of the frontline research workers involved in FEM-PrEP, I noticed a mural on the wall of the research clinic’s waiting area. It was painted to help explain the study to its participants. The painting depicted a member of the study team, an African woman, explaining a number of biomedical interventions that were important in the treatment and prevention of HIV. The women study participants are shown a number of features such as voluntary testing and counselling, which had all been successful. The role of vaccines, microbicides and PrEP were presented as being unknown. The mural conveyed the rationale for testing PrEP and that its focus was to be on women. It was a pictorial representation of the idea that these biomedical interventions were moving in a linear progression towards eliminating HIV. The involvement and co-operation of African women was essential in answering some of the unknown questions posed by interventions such as PrEP and microbicides.

The idea that women were vital to the reduction of HIV transmission on the African continent was a consistent message conveyed through a number of international agencies. As discussed earlier in the paper, the focus on women as targets for PrEP was also seen to be the most ethical course of action as informed by a rights-based approach. During the everyday conduct of the trial, these arguments were frequently enlisted to mobilise women to participate in the trial. In the following quote, one of the community interviewers provides a valuable insight into how the value of the drug Truvada, the pharmaceutical name for FEM-PrEP was explained to women in that area:

So [in this] culture, when you talk of gender empowerment … you [as a woman] can’t go to a man and say ‘I want to have sex with you today’. That’s abnormal.

But when I speak to them [the study participants] I ask them, ‘Why is it that when you ask for sex, [although] you are a human being, it is abnormal?’ ‘When a man asks [for sex], a man who is also a human being, then it’s normal?’ ‘We [are] now talking about the right of being a human being, and [this culture is] taking that from women’

Like in that forum when we say we want to empower women to be using Truvada whenever they have sex, so that they can have sex even if men doesn’t want to use condoms, that they are taken care of. The culture here is really different to what happens in Europe. Women can ask if they want sex and if they say no to sex it’s no problem. Here we are somehow behind and I explain that Truvada gives them the same rights as European women… (Community Interviewer, Face-to-face interview, July 2009)

From this quote it becomes clear that testing Truvada, in the FEM-PrEP study, is justified and explained using a variety of concepts including gender empowerment and racial equality. Women’s rights to have the drug is made explicit. FEM-PrEP is described by this community interviewer in discussions with African women as having the potential to provide them with the opportunity to realise their human rights and align their current position with those enjoyed by women in developed countries, such as those in Europe. Hence, a great deal is expected of the FEM-PrEP. In another quote, a different community interviewer describes FEM-PrEP as a weapon to use against abusive men. The discussion between the community interviewer and community members unfolds as follows:

Oh like the PrEP thing … Like I say to them … ‘We know the interventions that the government have in place for preventions … those that are available are men controlled. For you to use them in our culture here, you have to ask permission from our men.’ So, I was trying to encourage them that, if this thing [FEM-PrEP] works then women will have their silaha. I used the term silaha… Silaha is a weapon. ‘You’ll have your silaha, your weapon. When your husband beats you sometimes you have to take it without a weapon … Same sometimes with sex … yes? If it works [FEM-PrEP] it would be weapon against those beatings… ‘

Yeah you know women are very funny people to work with. So in one of our baraza [community meetings] one said ‘OK when I have used my silaha against my husband, can I have children from a man who is beaten up?’ I said ‘You are not meant to kill him just protect yourself… being fertile is very important here. Another woman said ‘What if my husband doesn’t beat me? Do I still have need for a weapon?’ (Community Interviewer, Face-to-face interview, June 2009)

Taken together these two quotes, obtained from separate face-to-face interviews, with community interviewers provide a number of important insights into how the ethical imperative underpinning FEM-PrEP – which is that women had a right to the drug – was practised and explained to African women. It meant that FEM-PrEP, tested in a context where it was assumed that women were made vulnerable by gender violence, unequal treatment, and without access to women-centred interventions, is presented as a means of not only mitigating that vulnerability but also, based mainly on a European image of an independent woman, could enable African women to realise their human rights and be empowered individuals. In this way, these discussions reveal some of the imaginations of both African women and their inherent vulnerabilities alongside those of their empowered and sexually liberated European counterparts. This insight is important, in illuminating which idea, or rather who is the human is being envisaged in the concept of human rights, and rights-based approaches in interventions aimed at African women. In this context, FEM-PrEP is promised to enable African women to do numerous things but it is also clear that the women trial participants were not entirely convinced by the claims being made or the types of outcomes that were described as possible. The types of questions, asked by the women in their exchange with the community interviewer, can be interpreted as challenging some of the assumptions about the nature of their relationships and priorities. However, it was not only the assumptions that were being called into question, in the accounts obtained from frontline research workers, the ‘HIV industry’ in this context revealed the economic disparities and injustices which, for many frontline workers, laid at the heart of the FEM-PrEP participants actions.

The HIV industry

Western Kenya is home to a large number of HIV-related activities undertaken by numerous organisations ranging from international research institutions involving American and European academic institutions, to international development agencies, national government initiatives and local community initiated programmes. These efforts are often uncoordinated and conducted without consultation with the other activities in the area and, at times, without national and/or local government knowledge. One of the appeals is an infrastructure that is conducive to the smooth running of research: there is a long history of research being conducted, a large labour pool of educated multi-lingual people and a population with high rates of HIV infection and transmission in this area. These factors have continued to justify the ongoing research presence in this area, which in turn produces different forms of employment for the local population, and seasoned participants. However, in interviews and discussions, the constant presence of research was often mentioned as something that undermined the goals of specific projects because the study populations were harder to mobilise behind research ideas. One of the clinicians in the study argues that study participants feel the following:

‘Why, why in Kenya? Why always in Bondo District? Why not in the US? Why not in Europe?’ At least for FEM-PrEP we’ve been saying the countries where this study is being conducted [are] in Africa. But yeah like they [women study participants] think that they’re the guinea pigs for whites and that is hard to change. For us and them we can say that yes they fund us but the head of the study is a local Kenyan woman…That has meant a lot for us to say it’s a study for Kenyan women headed by a Kenyan woman…This is very different to the other studies around here and we say that and take pride in that… (Research clinician, Face-to-face interview, June 2009)

In this quote, the clinician draws attention to the fact that the great research presence had produced scepticism and suspicion among many members of the local population about the aims of research. The following discussion with community interviewers is useful in that it not only presents their views on the practice and legacy of HIV research in the area but also how this shapes the relationship with their trial participants. What becomes clear in their account is that they often share some the disillusionments with research that are expressed by their trial participants, often seeing the profit motives by pharmaceutical companies as the reason for research rather than discourse of ethics or empowerment. Furthermore, this exchange between community interviewers is valuable because they argue that in the absence of being motivated by the explicit aims and ethics of HIV research, it becomes important to fulfil other outcomes and ethical concerns in the conduct of their work. These include improving the health infrastructure by having a tangible physical space paid for by the research, which will remain after the trial has been completed; having good working relationships with the community; and ensuring that the trial participants are being treated fairly. In discussion with community interviewers (CIs) they explained that:

CI 2: They [women study participants] say, ‘You, you people you come here, you cheat us and then you go and leave us here. You use us and dump us.’

CI 3: They have valid point but it’s not right that they are being used by us, and treated unethically…but most organizations or researches don’t come and give back results and don’t act in ways which are ethical according to them…

CI 4: Even us sometimes we have sat back and wondered you know, ‘Should we [be] giving more to our participants?’

CI 1: The pharmaceutical company is going to make so much money. Where is the profit going to? Inasmuch as it’s going to improve… health … empowers women, alleviate hunger or whatever the community is going to pay for this.

CI 3: Yeah. I agree…there should be some tangible benefit that a research participant gets or the community gets from the research …Maybe construction of a hospital or something like that in the community.

PK: What about the [research] clinic here?

CI 2: Yes…The researches have been here for so long and now thank God we have something to show to the community to say it is being left behind!

CI 4: If we knew the science would work I don’t think that we would be doing this [research] …for that part I can’t say how this are going to be…but the ethics part of this [FEM-PrEP] is absolutely fail-safe…the clinic is here and we have treated the women fairly…the science part is not clear because that benefits the pharmaceutical companies first and us and these women second….

CI 1: Yes, every couple of years there’s a new something that will cure HIV…mobilising the community behind that becomes difficult but when we can show them that we are listening and considering their needs, then the science part is not the main point because in the community that is hardly ever their main concern…

(Community Interviewers, FGD, June 2009)

This extract from a FGD held with community interviewers is insightful for a number of reasons. It makes clear what their markers of ethical conduct were and how, for them, the fail-safe device operated. The discussion demonstrates that ideas of the right-based ethical approach, which was used to justify the conduct of FEM-PrEP was not interpreted as being as significant as other ideas of ethical conduct, such as developing the local healthcare infrastructure and fair benefit for research participation. Furthermore, the community interviewers were sceptical about who they saw as being the beneficiaries of this trial, and HIV research more generally. The pharmaceutical companies whose drugs were being tested in this area were deemed to make the most profit and this undermined the confidence of some of those on the frontline that such trials were intended to benefit the study participants. In this way, they regarded these trials not necessarily as empowering and promoting the human rights of women but, rather, in overlooking the complexities of their everyday lives held the potential to further disempower them. They felt that the women should be supported more in gaining more material benefits from these trials if not individually then certainly at a community-level.

While these arguments from the frontline workers are not incompatible with the rights-based approach, they suggest that prioritising women’s access to HIV drugs was not seen as the primary means of their empowerment but rather that practical and material concerns were of utmost importance. For this reason, the community interviewers and frontline workers in general regarded the everyday conduct of the FEM-PrEP trial to be ethical. They felt that it contributed to the local healthcare infrastructure and through their own actions; they ensured that they assisted women in addressing some of the financial problems they faced often from their own income. In this way, the ethics of the trial were fail-safe because even if the pill was shown to be ineffective, the tangible evidence of their interpretation of ethics (the research clinic, the material benefits given to participants) meant that for them it had succeeded even if this occurred through their own personal interventions and not through the design of the study. This idea was expressed in interviews both during and after the trial was halted. So that while the study was deemed by some to have been a failure, and the frontline research workers I spoke to were disappointed with the outcome, they also expressed views that they felt that they had acted in accordance to their ethics. For this reason, the trial could also be considered a success.

Given the confidence of these community interviewers that their ideas of ethics were being enacted in FEM-PrEP, it is also interesting to consider why some of the study participants did not take the study pill. It became clear that the numerous uncoordinated research activities in this area had other practical implications for the running of FEM-PrEP. In particular, one of the main concerns expressed during the conduct of the trial was the possibility of women double or co-enrolling in studies occurring concurrently. In the following quote one of the research nurses explains this concern:

I think the biggest challenge that we are facing now is having a lot of research work being conducted…Just within the same region.

So um… one of the fears, one of the concerns in FEM-PrEP is double or co-enrolment where one participant comes to this clinic, we get to enrol her in our study where we have an intervention, and it’s some product that is taken orally and then they go to another study and maybe they’re given a vaccine or… they are given another intervention and since… in most cases if it is going to be a clinical trial then it’s going to be blinded.

Yeah so for both studies I mean nobody will know who’s taking what

Research Nurse, face-to-face interview

In another quote, one of the community interviewers explains the research context in which FEM-PrEP was being conducted, the competition between institutions and the potential for women to double-enrol, and how they might protect themselves if that was the case. He explains as follows:

… there is another PrEP trial it’s not very far from here… then there is going to be another one by CDC-KEMRI. Just next in the neighbouring district. So it’s very easy for those [women] who really want to [double enrol], they just cross and go. I mean it’s not like you’ll take 10 hours to get to that place. It’s just a few kilometres…

Maybe your meals when you go there you’re taken care of. When you come to this side [FEM-PrEP] your transport is taken care of, you’re also compensated …so there may be motivation for one to want to join two studies. I can understand it but I worry for the women… I think if they are double-enrolling they won’t take two pills… I think they won’t take any of the drugs being given to them just in case…

Community interviewer, face-to-face interview

The value of this quote is that it provides an alternative explanation for why the study participants may not have taken the study pills. The extent to which double-enrolling did occur was outside the remit of my work but in this alternative explanation there is a different account of the women involved in the study. Here they are presented as resourceful, pragmatic and able to discern which trials had the best benefits to suit their needs. From this account it was not that they could not take the study pills, as has been reported elsewhere, but rather that they did not want to take them. Therefore, in their own way, one interpretation of their actions is that they demonstrated that they were empowered by their own motivations, which were generally material or health care related. They made decisions based on their own self-interest and priorities. In this sense, the goal to empower women was successful, but on their own terms.

Discussion/conclusion

The FEM-PrEP study encapsulates many of the features of contemporary research, however, it was conducted with such high hopes of success that it gained international attention even before it began. FEM-PrEP has been described as: ‘the ultimate female controlled method’ a ‘performance’ and its rights-based approach as ‘Emperor’s new clothes’. Amidst the drama and discourses of failure, success and ethics, and away from the world stage where FEM-PrEP was played out, I sought to provide an account of the views of frontline research workers employed in the practices of research, and ethics of this study.

On the ground, those involved in the trial raised a number of important issues which can inform the way in which this and other similar studies are understood. They have described the everyday realities of research as something that operates with multiple motives, agendas and expectations from all the different actors involved. However, from the outset, the expectations of this trial not only shaped its conduct but also how its outcome was assessed.

The role of expectations in producing ideas of failure in HIV research

Both in the mural, presented in Figure 1, and the accounts provided by frontline research workers in western Kenya, reservations and questions were openly expressed about the possible outcome of the FEM-PrEP trial. These more muted responses to FEM-PrEP were in contrast to the high hopes and expectations discussed at the level of international scientists and activists about PrEP. For while many operating at the international level treated the results of the PrEP trials as a foregone conclusion and urged that it be deployed without delay as a frontline treatment and prevention for HIV (Cairns 2009), from the accounts of those in the field, frontline research workers were more open to the idea they were conducting research and there was the possibility of an uncertain outcome.

Figure 1. Women’s role in reducing transmission of HIV.

Photograph taken by Patricia Kingori, May 2009.

There are a number of possible explanations for what appears to be a disparity between the frontline research workers based in the field and the international community, but one explanation could be the difference in contextual experience of conducting research on the ground. From the accounts obtained from frontline workers, FEM-PrEP was conducted in an area that was saturated with HIV research. This continual experience of research has shaped how FEM-PrEP was viewed. For members of the local population who may have witnessed many studies promise great things and then not deliver on those expectations, research projects and their ethical promises were not taken at face-value and were not assessed using the same criteria as found by those operating at an international level.

Scholars in the field of the Sociology of Expectation, such as Geels and Smit (2000), explain that while raising expectations has the strategic function of mobilising resources and garnering support for research, it does this at the expense of creating promise– disappointment cycles among targeted groups. Over time, these cycles produce fatigue and disillusionment with the aims of research when the anticipated aims are not met. Furthermore, successive disappointments based on inflated expectations in the field of HIV, might result in lasting damage to the credibility of researchers and professional groups in mobilising community groups and study populations (Michael and Brown 2003). The cumulative effects of such promise–disappointment cycles in the field of HIV are rarely explored (Rhodes, Bernays Terzić 2009). Furthermore, the role of ethics and the ethical implications in the strategic deployment of anticipatory and promissory rhetoric for patient groups and study populations has received scarce attention (Brown, Rip Van Lente 2003, Rosengarten and Michael 2009).

From the accounts of frontline research workers, it is clear that FEM-PrEP was conducted in contexts with extensive experience of HIV research and also the promise– disappointment research cycles that have accompanied this field. Women in the study were told that the pill would empower them, improve their human rights and give them parity with European women. However, it was clear from the study results that these promises were not accepted. Hence, in FEM-PrEP, one expression of the promise– disappointment cycle was that other motivations for being involved in research became apparent among the research participants eager to cease the opportunity of the temporary access to material benefits available during the conduct of this trial and other trials occurring at the same time. For the research staff, having employment was important but it emerged in these interviews that they were not motivated by being involved in a project that produced profits for pharmaceutical companies. While some, at least publicly, promoted the idea that the pill could transform the view of women in keeping with the rights-based approach advocated by the trial, they also formulated their own markers of what constituted an ethical trial. Their idea of ethics included being part of a study that left something tangible behind for the local community and developed the local health infrastructure. It was important that the study was fair and extended some of the profits being made by the pharmaceutical companies to the women and which provided them with a means to improve their lives. The daily operations of FEM-PrEP met these expectations of ethical conduct as described by the frontline workers in this study and for this reason those interviewed were confident of ethical conduct and described it as ‘fail-safe’, whether the science worked or not their ethics was in place and could not fail. While these women had no control over the international machinery which governed the ethics and design of the PrEP trials, they were seeking economic justice through their participation in trials such as FEM-PrEP. Therefore, regardless of the outcome of the trial, their short-term basic needs were met and to this end, these women were successful.

However, it is not only these ethics of the frontline research staff which were ‘fail-safe.’ The ending of FEM-PrEP and its apparent failure has done little to reduce the momentum of PrEP and the right-based approach has also been deemed to have provided a justification beyond reproach (Kenworthy and Bulled 2013). PrEP continues to be advocated for and researched on African women who are argued to have a right to PrEP to be empowered in the fight against HIV, despite other ‘failures’ such as the VOICE trial.

The VOICE trial (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic), which cost close to $100 million was another PrEP funded trial by US National Institute for Health (NIH) aimed African women and, like FEM-PrEP, it was deemed a failure (Susser 2015). In February of this year, the VOICE trial team reported that blood tests discovered that only three of every ten women took PrEP in the study (Marrazzo et al. 2015, McNeil 2015). Ariane van der Straten, a researcher who led follow-up interviews with over 300 women argued that: ‘No one expected they would go to such contortions to appear being adherent when they were not.’ She said that ‘One gave hers [PrEP] to a friend working as a prostitute. Another stockpiled them for later, to take if they were found to work’ (McNeil 2015). In this way, like FEM-PrEP, the women research participants who were considered to be disempowered exerted their own agenda onto the conduct of these trials having not accepted their aims and motivations at face-value. As a result, their actions were interpreted as being responsible for the failure of these studies and the scientific aims and ethical justifications were deemed legitimate (Dai et al. 2015).

In including the VOICE trial as another example, it becomes clear that having been brought into the study to legitimise the ethical conduct of PrEP research, African women have been perceived to be responsible for its failure. These explanations, while proposing that there was a failure, have through their focus, placed the emphasis for these failures in the social world and in particular on the context and the women involved (Kenworthy and Bulled 2013). Implicit in this position are a number of assumptions, which include the idea that the social and scientific worlds are two distinct silos that can be demarcated. There is also the idea that it is only the social world that disrupts science but not that science can cause disruption to the social world (Susser 2015). Yet, we have heard that through research-saturation and the operations of the numerous competing institutions in the HIV industry that science can disrupt the social world, through its inflated promises and ideas of ethics in numerous ways.

Failure as situated in the social realm not only frames responsibility but types of research and the accounts they produce. McGoey (2010) argues that one of the consequences of positioning the source of failure outside of the science, is that it acts to legitimatise the methodology and the ethical imperative proposed to justify the trial. In the FEM-PrEP trial a rights-based approach justified its framing of the problem and then the subsequent research on women. When the study was halted it was described as being due to the actions of women acting outside of the study protocol. This left the methodology and the ethics unexplored and further legitimised the conduct of future research on women. Hence, the international machinery of the PrEP clinical trials and implementation was enabled to revert back to a safe condition in the aftermath of events such as FEM-PrEP and VOICE confident in its conduct as being motivated by the pursuit of human rights which pushed forward an infallible system beyond failure. The rights-based position operated as a fail-safe device, which foreclosed critiques of the framing of the answers to HIV prevention on the African sub-continent solely along biomedical lines and have allowed, access to PrEP to be considered the priority for African women at risk of HIV. However, the frontline research workers and the African women involved had other competing priorities which they ensured were achieved during the course of the trial. In this way, ethics has acted as a fail-safe device for numerous actors in providing a means to have their motivations and agendas served through the practice of science.

Acknowledgements

The author would to thank the frontline research workers for giving of their time and sharing their valuable experiences and insights. The author would also like to thank the two reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. Responsibility for the arguments made in the article remains, however, with the author alone.

Funding

The data presented in this article were generously supported by the Wellcome Trust Society and Ethics Funding Scheme (WT080546MF).

Footnotes

Ethics Approval

This study of frontline research workers involved gaining multi-institutional ethics approval. Ethical approval was sought from seven different institutions, which included the author’s UK-based academic institutions and national ethical boards in the respective countries. Furthermore, permission was sought from frontline workers and their line managers (e.g. Principal Investigators) involved in research projects, and in the case of FEM-PrEP also from FHI 360, one of the funders of the trial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- The Oxford English Dictionary. Simpson J, Weiner E. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Annan K. The New York Times. The New York Times Company; New York: 2002. In Africa, AIDS Has a Woman’s Face. [Google Scholar]

- Brown N, Rip A, Van Lente H. Expectations in & about Science and Technology Expectations Workshop. Routledge; Utrecht: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns G. The Perils of Success: What if the New Prevention Methods Work? NAM aidsmap. 2009. [last accessed 1st September, 2015]. http://cms.nam.org.uk/site/print/page/1435889/

- Carins G. Magical Thinking? FEM-PrEP Trial may have Failed Because Participants used Testing as Prevention. NAM aidsmap. 2013. [last accessed 1st September, 2015]. http://www.aidsmap.com/Magical-thinking-FEM-PrEP-trial-may-have-failed-because-participants-used-testing-as-prevention/page/2695635/

- Cohen J. Anti-HIV Pills Powerfully Protect Uninfected Heterosexuals. Science Mag. 2011. [last accessed 1st September, 2015]. http://news.sciencemag.org/health/2011/07/anti-hiv-pills-powerfully-protect-uninfected-heterosexuals .

- Corneli AL, McKenna K, Perry B, Ahmed K, Agot K, Malamatsho F, Skhosana J, Odhiambo J, Van Damme L. The Science of Being a Study Participant: FEM-PrEP Participants’ Explanations for Overreporting Adherence to the Study Pills and for the Whereabouts of Unused Pills. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(5):578–584. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A, Harrison E, Whitehead A. Gender Myths and Feminist Fables: The Struggle for Interpretive Power in Gender and Development. Development and Change. 2007;38(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan EA, Macklin R. Is Preexposure Prophylaxis Ready for Prime Time use in HIV Prevention Research? AIDS. 2014;28(3):293–295. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JY, Hendrix CW, Richardson BA, Kelly C, Marzinke M, Chirenje ZM, Marrazzo JM, Brown ER. Pharmacological Measures of Adherence and Risk of HIV Acquisition in the VOICE Study. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015:333. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv333. j(iv) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FHI. FHI Statement on the FEM-PrEP HIV Prevention Study. fhi360. 2011. [Last accessed 1st September, 2015]. http://www.fhi360.org/news/fhi-statement-fem-prep-hiv-prevention-study .

- Geels FW, Smit WA. Failed Technology Futures: Pitfalls and Lessons from a Historical Survey. Futures. 2000;32(9-10):867–885. [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, Goicochea P, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men who Have Sex With Men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haire B, Kaldor JM. Ethics of ARV Based Prevention: Treatment-as-Prevention and PrEP. Developing World Bioethics. 2013;13(2):63–69. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins CA, Dybul MR. The Promise of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis With Antiretroviral Drugs to Prevent HIV Transmission: A Review. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8(1):50–58. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835b809d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper I, Parker M. The Politics and Anti-Politics of Infectious Disease Control. Medical anthropology. 2014;33(3):198–205. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2014.892484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL, Elias C. Transforming AIDS Prevention to Meet Women’s Needs: A Focus on Developing Countries. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(7):931–943. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00165-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn T. Poor Adherence Crippled PrEP Efficacy in Women’s Study. AIDSMeds. 2012. [Last accessed 1st September, 2015]. http://www.aidsmeds.com/articles/hiv_prep_women_1667_22021.shtml .

- Karim SSA, Karim QA. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis: A Defining Moment in HIV Control. The Lancet. 2011;378(9809):e23–e25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy NJ, Bulled N. From Modeling to Morals: Imagining the Future of HIV PREP in Lesotho. Dev World Bioeth. 2013;13(2):70–78. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange JMA. We Must Not Let Protestors Derail Trials of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(9):e248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, Palanee T, et al. Tenofovir-Based Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascolini M. Poor Adherence May Explain FEM-PrEP Failure to Find Protection from HIV with Truvada; 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McGoey L. Profitable Failure: Antidepressant Drugs and the Triumph of Flawed Experiments. History of the Human Sciences. 2010;23(1):58–78. doi: 10.1177/0952695109352414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil GD. The New York Times. The New York Times Company; New York: 2015. A Failed Trial in Africa Raises Questions About How to Test HIV Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- Meier BM, Brugh KN, Halima Y. Conceptualizing a Human Right to Prevention in Global HIV/AIDS Policy. Public Health Ethics. 2012;5(3):263–282. doi: 10.1093/phe/phs034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael M, Brown N. Dys-Topias and Dys-Tropias: Futures and Performativities in Xenotransplantation; The annual British Sociology Association Conference; University of York. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery CM. Making Prevention Public: The Co-production of Gender and Technology in HIV Prevention Research. Social Studies of Science. 2012;42(6):922–944. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamu-Musembi C, Cornwall A. What is the ‘Rights-based Approach’ all about?: Perspectives from International Development Agencies, IDS Working Paper 234. 2004

- Petryna A, Andrew L, Arthur K. Global Pharmaceuticals: Ethics, Markets, Practices. Duke University Press; Durham, N.C: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Bernays S, Terzić KJ. Medical Promise and the Recalibration of Expectation: Hope and HIV Treatment Engagement in a Transitional Setting. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(6):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarten M, Michael M. The Performative Function of Expectations in Translating Treatment to Prevention: The Case of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(7):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarten M, Michael M. Rethinking the Bioethical Enactment of Medically Drugged Bodies: Paradoxes of Using Anti-HIV Drug Therapy as a Technology for Prevention. Science as Culture. 2009;18(2):183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L, Wise S. Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. Routledge; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Susser I. Al Jazeera America. Al Jazeera Media Network; New York: 2015. Blame Research Design for Failed HIV Study. [Google Scholar]

- Uvin P. On High Moral Ground: The Incorporation of Human Rights by the Development Enterprise. Praxis: The Fletcher Journal of Development Studies. 2002;17:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Walker BD, Burton DR. Toward an AIDS Vaccine. Science. 2008;320(5877):760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1152622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Parker C, Ahmed K, Agot K, Skhosana J, 2, Odhiambo J, 3, Makatu S, et al. Participant Motivation for Enrolling and Continuing in the FEM-PrEP HIV Prevention Clinical Trial; Seventh International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis. 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Kuala Lumpur. 2013. [Google Scholar]