Abstract

Nucleic acid catalysts (ribozymes, DNA- and XNAzymes) cleave target (m)RNAs with high specificity but have shown limited efficacy in clinical application. Here we report on the in vitro evolution and engineering of a highly specific modular RNA endonuclease XNAzyme, FR6_1, composed of 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acid (FANA). FR6_1 overcomes activity limitations of previous DNA- and XNAzymes and can be retargeted to cleave highly structured full-length (>5 kb) BRAF and KRAS mRNAs at physiological Mg2+ concentrations with allelic selectivity for tumour-associated (BRAF V600E and KRAS G12D) mutations. Phosphorothioate-FANA modification enhances FR6_1 biostability and enables rapid KRAS mRNA knockdown in cultured human adenocarcinoma cells with a G12D-allele-specific component provided by in vivo XNAzyme cleavage activity. These results provide a starting point for the development of improved gene silencing agents based on FANA or other XNA chemistries.

Introduction

Nucleic acids are not only at the heart of the genetic apparatus of all life, but have great potential as a source of powerful therapeutic agents. The unity of genotype and phenotype within the same nucleic acid molecule enables in vitro evolution at the molecular level, allowing the discovery of RNA- and DNA-based ligands (aptamers) and catalysts (ribo- and deoxyribozymes, “DNAzymes”) directly from random sequence repertoires for a wide variety of applications1–3. Of particular interest among these are RNA endonucleases, such as the archetypal “hammerhead” (RNA)4, “10-23” and “8-17” (DNA) motifs5,6, which form a modular structure comprising a central catalytic core flanked by guide sequences or substrate-binding arms with complementarity to target RNA, which can be modified to reprogram cleavage specificity. These modular endonucleases can be directed to cleave RNAs of interest, providing a route to synthetic regulators of gene expression1, biosensors7, molecular computers8,9 and nanoscale machines10, and potentially as programmable, highly specific gene silencing agents. Notable examples of clinical evaluation include variants of the hammerhead ribozyme11,12 and the 10-23 DNAzyme, in particular “hgd40” targeting an RNA encoding a master transcription factor of type-2 immune responses (GATA-3), reported to show some efficacy in reducing inflammation in psoriasis, asthma and COPD13–15, and “Dz13” targeting c-Jun mRNA, explored as a cytotoxic agent in a range of neoplasias16. However, despite the promise of simple and programmable gene silencing agents that - unlike CRISPR Cas-based reagents - could be produced by solid-phase chemical synthesis and delivered exogenously, they have so far failed to have significant clinical impact despite persistent efforts for over 20 years17–20, underscoring the need for new, improved strategies for RNA-cleaving catalysts.

In general, susceptibility to nuclease degradation, dependency on unphysiological concentration of metal ion cofactors, poor substrate accessibility within structured target RNAs and poor intracellular delivery are thought to represent the main obstacles to successful use of oligonucleotide catalysts in vivo. Among these, the dependency on divalent metal ions for both folding and catalysis is a particular challenge. In the case of the 10-23 DNAzyme, folding of the active conformation of the catalytic core has been reported to be negligible at intracellular levels of free Mg2+ (0.5-1 mM)21, and to be further inhibited by ATP22, precluding efficient RNA cleavage activity inside cells. Indeed, detailed studies of observed knockdown of intracellular mRNA by 10-23 and its derivatives have attributed its activity to an antisense effect mediated by RNase H (triggered by Watson-Crick pairing of binding arms to the target RNA), rather than catalytic activity of the DNAzyme23. Similarly, mutational studies showed that in vivo activity of 10-23 appears to be independent from catalysis24; in the case of the “Dz13” variant, G-rich sequences spanning the substrate-binding arms and core were found to be responsible for its cytotoxic activity and not an active catalytic core25,26.

Nonetheless, DNAzymes that retain activity under quasi-physiological conditions or in the absence of Mg2+ have been reported27–29. However, RNA cleavage is typically measured using short DNA substrates with a single embedded ribonucleotide, and activity on all-RNA substrates is much reduced. To address this issue, introduction of amino acid side-chain functionalities have been explored, either as co-factors30 or incorporated into modified nucleobases31–32. Addition of hairpin domains34 or presentation of catalysts in nucleic acid nanotechnology architectures35,36 also seem promising, and additionally offer reduced susceptibility to nucleases for improved biostability. Notably, partial modification of DNA with alternative backbone and sugar congeners – also known as “xeno nucleic acids” (XNAs)37 - commonly used to boost siRNA and antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) bio- and thermodynamic stability for target strand invasion, such as 2’-O-methyl-RNA (2OMe-RNA), locked nucleic acid (LNA) and 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acids (FANA)38–40, can also improve RNA-cutting ribozymes and DNAzymes41–48, including a recently-described FANA- and TNA-modified variant of 10-23 (“X10-23”) that showed enhanced RNA cleavage and intracellular knockdown activity49–51. However, in such medicinal chemistry iterations, modifications must be evaluated iteratively, post-selection, and typically cannot be evaluated at all positions due to cost and time imitations. Selection of fully-modified XNA catalysts (“XNAzymes”) enabled through polymerase engineering52–54, provides an alternative approach to discover novel RNA endonucleases directly from random sequence repertoires in multiple XNA chemistries55,56, including 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acids (FANA)56,57.

Here we report the de novo selection and characterization of an RNA endonuclease XNAzyme, FR6_1, entirely composed of 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acids (FANA), that displays modularity (“programmability” to alternative RNA targets) and efficient catalytic activity on long, structured (m)RNA targets at physiological concentrations of Mg2+ ions. We report specific cleavage of mutant KRAS and BRAF oncogene mRNAs with single-nucleotide precision, and rapid allele-specific mRNA knockdown of G12D KRAS mRNA upon transfection into live cultured adenocarcinoma cells, and demonstrate that – unlike gene silencing effects observed with 10-23 DNAzymes – RNA knockdown is not exclusively mediated by antisense-type effects but that a significant contribution is made by XNAzyme catalysis inside cells, in particular at low concentrations.

Results

Selection of an RNA endonuclease XNAzyme from degenerate FANA libraries

We and others had previously isolated RNA endonuclease XNAzymes composed of FANA56,57, but these required significant (>20 mM) concentrations of Mg2+ ions ([Mg2+])for comparatively modest catalytic turnover. Furthermore, these were non-modular, i.e., could not easily be adapted to cleave alternative RNA targets without substantial loss of activity57. We therefore reinitiated XNAzyme selections55, starting from two diverse libraries of semi-random all-FANA oligomers synthesized using engineered polymerase D4K58, comprising either a fully-random N40 sequence, or an N20 random ‘core’ sequence flanked by two regions complementary to a 40-nucleotide subgenomic RNA segment from Ebola Zaire (Residues 16062-16101: NC_002549.1)59 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In this selection strategy, the RNA substrate serves as a primer for DNA-templated FANA synthesis and thus is covalently linked to FANA library sequences enabling efficient size-selection for RNA cleavage by Urea-PAGE and reverse transcription of FANA sequences back to DNA using engineered reverse transcriptase RT52158. The polyclonal round 6 pool showed robust cleavage activity and deep sequencing of cDNA and analysis of the most abundant sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1b) suggested that the selection had converged on a common motif (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The most abundant sequence, “FR6_1” was found to be capable of cleavage in both cis and trans (as a bimolecular reaction), and was chosen for more detailed characterization (Fig. 1). The potential for FR6_1 as an antiviral will be explored elsewhere.

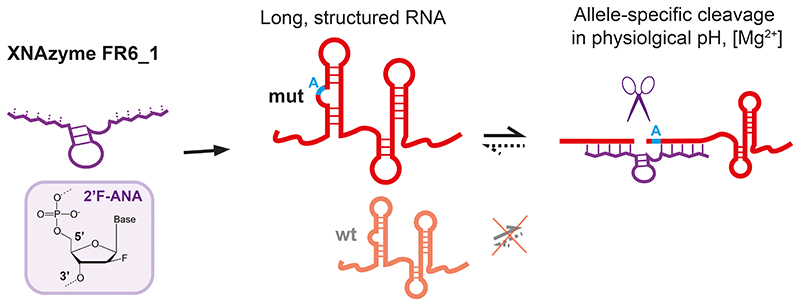

Figure 1. FR6_1 is an RNA endonuclease XNAzyme composed of 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acids (FANA).

(a) Sequence and putative secondary structure of XNAzyme “FR6_1” selected to target RNA “Sub_Ebo” (residues 16062-16101 of the Ebola Zaire virus genome). FANA nucleotides are shown in purple, RNA in black. Cleavage site is denoted by (▼). Dashed lines denote termini of version used for reactions in trans (“FR6_1B”), which also included an additional FANA-G between residues 4 and 5 as shown. Numbering is based on the parental FR6_1 sequence. (b) Urea-PAGE gel showing substrate RNA Sub_Ebo (1 uM) incubated with or without XNAzyme FR6_1B (5 uM) in trans (1 h, 17 °C, 10 mM Mg2+). “T1” and “-OH” indicate hydrolysis of RNA Sub_Ebo with RNase T1 (cleaves at guanine residues) or alkaline conditions, respectively, as reference. (c) Pre-steady state bimolecular reaction of substrate RNA Sub_Ebo (1 uM) with XNAzyme FR6_1B (5 uM)(37 °C, pH 8.5, 25 mM Mg2+). Error bars show standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three independent replicates. (d) Urea-PAGE gel showing FR6_1B (10 nM) performing multiple turnovers of Sub_Ebo (1 uM) RNA cleavage. Normalised activity of FR6_1B (5 uM) on Sub_Ebo RNA (1 uM) in varying (e) concentrations of MgCl2 or (f) pH, showing that FR6_1 retains the majority of its function at physiological Mg2+ and pH (dashed red lines).

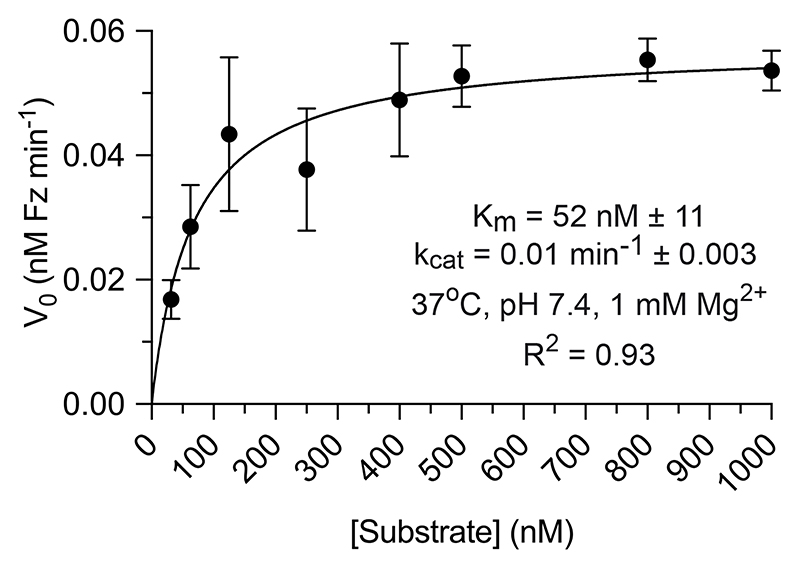

Specificity and characterization of a truncated version of XNAzyme FR6_1

We had previously found that using DNA parameters enable broadly correct for FANA secondary structure prediction56,60. By these criteria, FR6_1 forms a catalytic core involving a 17 nt stem loop structure with a three-nucleotide unpaired bulge at the RNA cleavage site, flanked by substrate-binding arms (Fig. 1a). Although unrelated to previously identified FANA RNA endonucleases56,57 or other nucleic acid catalysts at the sequence level, the FR6_1 architecture is reminiscent of the canonical “8-17” DNAzyme5, whose catalytic core contains analogous ‘core stem’ and ‘bulge loop’ structures, albeit in reverse orientations. We had previously observed a similar architecture in AR17_5, an XNAzyme composed of arabino nucleic acid (ANA)56 but found that 8-17 is inactive when converted into an FANA or ANA backbone56. FR6_1 could be truncated (yielding “FR6_1B”) by deleting substrate-binding arm residues 1-4 and 34-44, and adding a 5’ FANA-G in order to form [8 + 8] Watson-Crick complementarity with its substrate RNA, “Sub_Ebo” (Fig. 1a) and was found to catalyze site-specific cleavage (Fig. 1b) with a pseudo first-order rate constant (kobs) of 0.08 min-1 ± 0.02 (Fig. 1c). FR6_1B demonstrated multiple turnover catalysis (Fig. 1d), with Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Extended Data Fig. 1). To explore the cleavage mechanism of FR6_1B, we examined the chemistry of RNA products using mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 2a), and an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) after hydrolysis and phosphatase treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2b), which were consistent with the presence of a terminal 2’,3’ cyclic phosphate, suggesting a transesterification pathway similar to other RNA-cleaving catalysts61 including the classic 10-23 and 8-17 DNAzymes62, as well as the previously described “FR17_6” FANA XNAzyme56. Consistent with a transesterification involving deprotonation of the 2’hydroxyl group of the ribose at the cut site for in-line attack, methylation of this group by substitution with a 2’-O-Methyl-RNA residue in a modified substrate rendered it uncleavable (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The above catalysts are obligate metalloenzymes, as indeed are most nucleic acid enzymes. Although Mg2+ remains a specific requirement for FR6_1B activity (Supplementary Fig. 2d,e), the XNAzyme showed a much-reduced dependence on Mg2+ ions, retaining 65 – 80 % of full activity at physiological levels of free Mg2+ (0.5 – 1 mM)(Fig. 1e), in buffers mimicking intracellular conditions63 (Supplementary Fig. 2f) and across a broad pH range (4.5-9.5)(Fig. 1f). Monovalent cations appear to be unnecessary for activity (Supplementary Fig. 2d).

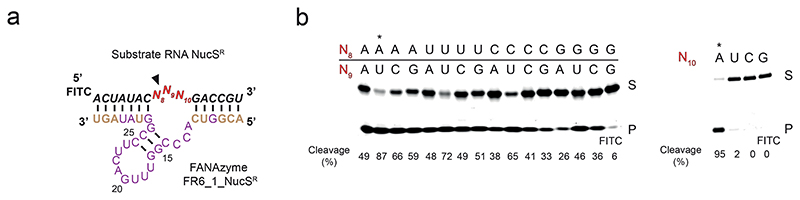

Next we probed cleavage specificity of FR6_1 by altering the substrate-binding arms (yielding “FR6_1_NucSR”) to fit a panel of previously-described RNA substrates (variants of “NucSR”)56 covering all nucleotide combinations at the three unpaired positions opposite the catalytic core and proximal to the cleavage site (Extended Data Fig. 2). This showed that FR6_1 is able to cleave almost all dinucleotide combinations at the cleavage site (positions 8 and 9 in Extended Data Fig. 2a), although with a preference for U at position 9, and poor cleavage of a GG dinucleotide at positions 8 and 9 (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Cleavage also showed a strong preference for an A at position 10 (one nucleotide downstream of the cut site)(Extended Data Fig. 2b).

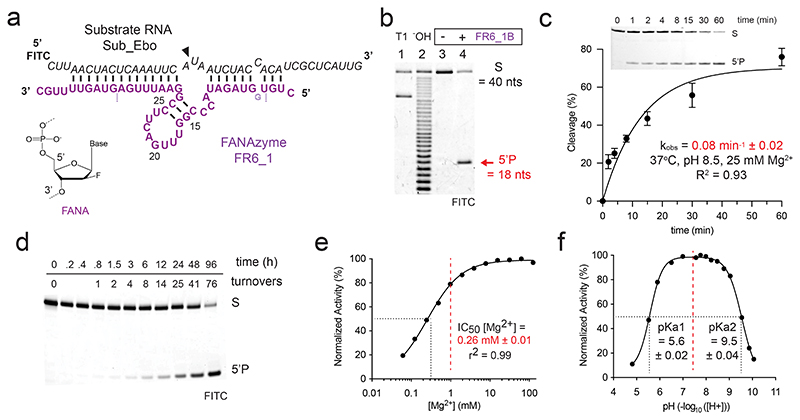

Reprogramming XNAzyme FR6_1 to cleave alternative RNA targets

Encouraged by the fact that FR6_1 substrate-binding arms could be both truncated and altered to fit variant substrates (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 2) without significant loss of activity, we explored FR6_1 modularity to target alternative RNA sequences (Fig. 2). We first targeted two sites in the mRNA of the KRAS oncogene (NCBI NM_004985.5) so that in each case the catalytic core was positioned for cleavage in a five-nucleotide motif (5’ - CA^UAA, with ^ representing the site of cleavage). The resulting XNAzymes, “FR6_1_KRas84” and “FR6_1_KRas166” (Fig. 2a,b), target KRAS mRNA nucleotides 430 - 452 and 677 – 699, respectively, and perform site-specific RNA cleavage activity with reaction rates only 3-fold slower than the parent XNAzyme under quasi-physiological conditions on 30 nt all-RNA substrates (kobs FR6_1_KRas84 = 0.4 h-1; FR6_1_KRas166 = 0.6 h-1; FR6_1 = 1.5 h-1) (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2. FR6_1 is a modular XNAzyme and can be re-programmed to alternative RNA targets.

Sequences and putative secondary structures of XNAzyme FR6_1 variants reprogrammed to target (a) human KRAS mRNA residues 426 - 455 (“Sub_KRas84”), (b) human KRAS mRNA residues 677 - 699 (“Sub_KRas166”), (c) human BRAF mRNA residues 2012 - 2038 (“Sub_BRaf600”) and (d) human KRAS residues 213 – 242 (“Sub_KRas12”). Urea-PAGE gels and graphs show bimolecular pre-steady state reactions of the XNAzymes shown (5 uM) with their cognate substrate RNA (1 uM). Incubation times for reactions shown in Urea-PAGE gels were (a & b) 17 h, (c & d) 20 h (25 °C, pH 8.5, 25 mM Mg2+). XNAzymes (c) FR6_1_BRaf600 and (d) FR6_1KRas12 demonstrate the potential for allele-specific targeting, with an obligate requirement for the BRAF c.1799T>A [V600E] or KRAS c.35G>A [G12D] versions of their substrate RNAs, respectively. Data and fits are shown for each re-targeted XNAzyme (black circles and solid black lines) in comparison with the parent FR6_1 cleaving its substrate (Sub_Ebo) under the same conditions (grey squares and dashed grey lines). Error bars show standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three independent replicates. All reactions were performed in quasi-physiological conditions (37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+) unless stated otherwise.

Next, we explored the potential of FR6_1-derived XNAzymes for allele-specific RNA cleavage. Given the strict requirement for A in the RNA substrate to be positioned one nucleotide downstream from the cleavage site (Extended Data Fig. 2), we chose disease-associated RNAs involving c.G,C,U>A point mutations, which are frequently found in the ClinVar database64 (30% of all single nucleotide variations). Specifically, we engineered XNAzymes (“FR6_1_KRas12” and “FR6_1_BRaf600”) to target two oncogenic mutations occurring in a range of malignancies65, KRAS codon 12 c.35G>A [G12D] or BRAF codon 600 c.1799T>A [V600E], which were found to be capable of cleaving all-RNA substrates (“Sub_KRas12” or “Sub_BRaf600”) under quasi-physiological conditions with a strict allelic preference (for KRAS 12D or BRAF V600E) with no cleavage observed for either KRAS or BRAF wild-type sequences (Fig. 2c,d). However, the single-nucleotide targeting specificity resulted in a trade-off in catalytic rates under quasi-physiological conditions, which were reduced (kobs FR6_1_KRas12 = 0.15 h-1), particularly in the case of the BRAF mutation (FR6_1_BRaf600 = 0.05 h-1), presumably due to the target sites differing from the preferred CA^UAA sequence: in RNA substrate Sub_BRaf600 [V600E] this sequence is CA^GAG and in RNA substrate Sub_KRas12 [G12D] it is CU^GAU - i.e. in both cases, the residues directly flanking the cut sites are less favorable combinations than in the parental enzyme-substrate complex (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 2).

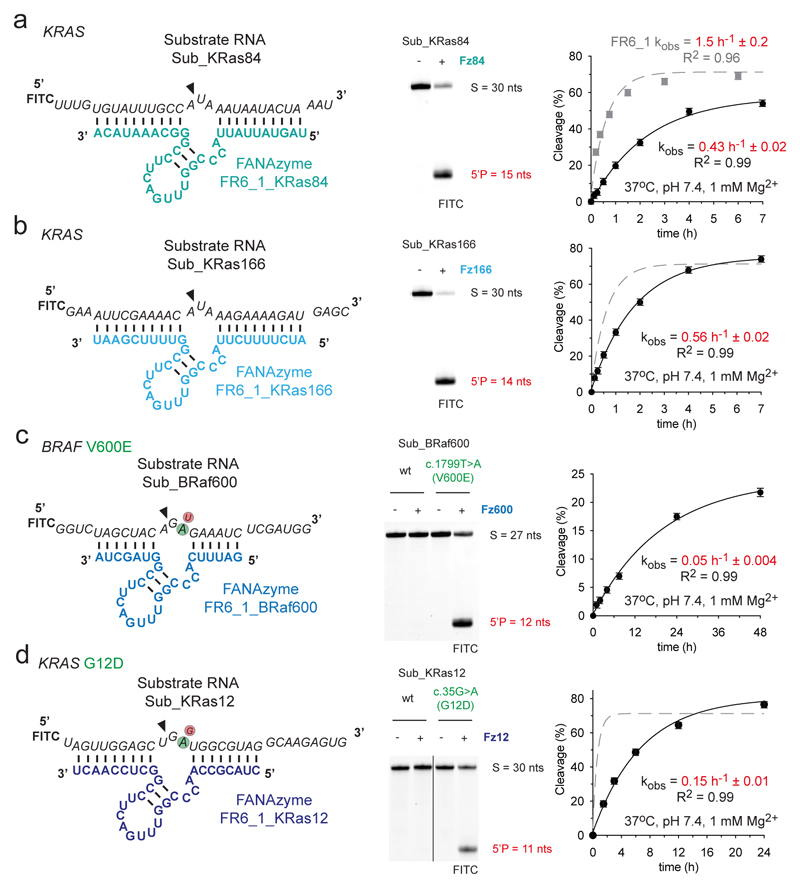

Development of a biostable XNAzyme capable of mutation-specific targeting of KRAS G12D RNA

Preferential cleavage in some sequence contexts over others is a common feature of many RNA-cleaving nucleic acid enzymes, including naturally occurring ribozymes. Next, we wondered if it would be possible to enhance catalytic activity of a retargeted allele-specific XNAzyme by screening and in vitro evolution, and focused on the FR6_1_KRas12 XNAzyme (Fig. 2d). First, we simply screened all possible transition mutations of putative catalytic core residues (Supplementary Fig. 3a), in order to identify invariant and mutation-tolerant positions. This screen informed the synthesis of a ‘spiked’ FANA library based on the sequence of FR6_1_KRas12 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). on which we performed six rounds of selection for cleavage an RNA substrate comprising KRAS residues 213 - 242 (equivalent to Sub_KRas12 [G12D]) in cis, under quasi-physiological conditions (37°C, 1 mM Mg2+, pH 7.4). Deep sequencing of the selection pool identified six recurring XNAzyme mutations represented across the ten most abundant clones (Supplementary Fig. 3c): fC10fA, fA11G, fC12fG, fC14fA, fC22fU and fG28fU (numbering according to the original FR6_1, Fig. 1a). The most abundant clone, containing all six mutations (“Resel1”, Supplementary Fig. 3c) was chosen for further study and a version of this XNAzyme was chemically synthesized, “FR6_1_KRas12B” (Fig. 3a). The mutations introduced by the re-selection appear to modifty Watson-Crick-Franklin base-pairing between the parental FR6_1 XNAzyme and its RNA substrate (Fig. 1a), at residues flanking the putative stem-loop catalytic core, potentially allowing the formation of an additional FANA x FANA base-pair (fA14 x fU28)(Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Reselection and modification of an FR6_1 variant yields a biostable allele-specific XNAzyme targeting KRAS G12D RNA.

(a) Sequence and putative secondary structure of XNAzyme “FR6_1_KRas12B” (Fz12B) reselected to target RNA “Sub_KRas12[G12D]”, comprising human KRAS RNA residues 213 – 242 bearing the G12D (c.35G>A) mutation. FANA residues in the catalytic core differing from FR6_1 are shown in gold. FANA-phosphorothioate modifications are denoted by (*). Circled bases denote mutations in the substrate or XNAzyme that enable (green) or abolish (red) RNA cleavage. (b) Urea-PAGE gel (17 h) and (c) graph showing bimolecular pre-steady state reactions of RNA Sub_KRas12 [wild-type (wt), or G12D] (1 uM) with enzymes (5 uM): data and fits are shown for Fz12B (black circles and solid black line) and an analogous DNAzyme “10-23_KRasC” (see Supplementary Fig. 4) (cyan triangles and solid cyan line) cleaving Sub_KRas12 [G12D], and the parent FR6_1 cleaving its cognate RNA substrate (Fig. 1a, 2a) for reference (Dashed grey line). (d) Urea-PAGE gel showing cleavage of Sub_KRas12[G12D] RNA (1 uM) by Fz12B (5 uM) or 10-23_KRasC (5 uM) in buffers mimicking intracellular conditions63 (See Supplementary Table 2)(2 h). Differences in product size are due to 10-23_KRasC cleaving one residue downstream compared with Fz12B. (e) Urea-PAGE gel and graph showing biostability of Fz12B with FANA-phosphorothioate (PS) modifications (black circles) or without (grey squares), and 10-23_KRasC (cyan triangles) in 90% human serum at 37 °C. All cleavage reactions shown were performed in quasi-physiological conditions (37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+) unless stated otherwise.

Investigating cleavage of longer, more realistic KRAS mRNA substrates by FR6_1_KRas12B, we observed a clear correlation between increased FANA arm length and cleavage activity on progressively longer RNAs with increasing secondary structure (Extended Data Fig. 3a-c); FANA arm lengths shorter than 10 apparently have insufficient strand-invasion capability on structured RNA under quasi-physiological conditions. FR6_1_KRas12B was therefore also synthesized with extended [10 + 10] substrate-binding arms (hereafter referred to as Fz12B).

Fz12B was found to retain a clear allelic specificity for cleavage of the c.35G>A [G12D] KRAS RNA substrate over the wild-type KRAS RNA (90% vs 15% cleavage, respectively, after 17 h) (Fig. 3b) with a five-fold improved single-turnover rate constant under quasi-physiological conditions (kobs = 0.75 h-1 ± 0.07)(Fig. 3c). Despite the extended substrate-binding arms, Fz12B was also found to retain a comparable capacity for multiple turnover catalysis as FR6_1 (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 3d).

In order to benchmark the FR6_1 XNAzyme to the classic “10-23” / “8-17” family of DNAzymes5,6, we designed a series of DNAzymes targeted to the same KRAS RNA target (Supplementary Fig. 4a-f) and screened their RNA cleavage activity and allelic specificity (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Among these, DNAzyme “10-23_KRasC” (Supplementary Fig. 4c) was a close functional analogue of FR6_1_KRas12B, capable of specifically cleaving the c.35G>A [G12D] KRAS RNA substrate with only minimal activity on the wild-type substrate (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Under favorable conditions for 10-23 DNAzymes (pH 8.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 17 °C), the catalytic rates of 10-23_KRasC and Fz12B were comparable (Supplementary Fig. 4h)(kobs = 0.12 h-1 vs 0.23 h-1, respectively). However, under quasi-physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 37 °C)(Fig. 3c) and in a series of buffer systems designed to mimic cytoplasmic conditions of low free [Mg2+] with chelating amino acids63 (Fig. 3d), 10-23_KRasC showed little to no activity, whereas Fz12B retained robust RNA cleavage activity. Consistent with this and our characterization of FR6_1 described above, Mg2+ and pH titration experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4i,j) revealed the strikingly lower dependency of the XNAzyme on Mg2+ and high pH compared with the analogous DNAzyme. Furthermore, the reselected Fz12B was found to require approximately 5-fold lower [Mg2+] than the parent FR6_1 (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 4j), with activity detectable even at < 10 nM Mg2+.

As FANA polymers display only modestly improved resistance to cellular nucleases, we also sought to improve the Fz12B biostability by modification of the (three 5’ and 3’) terminal residues with FANA phosphorothioate linkages (FANA-PS), which significantly reduce degradation by serum exonucleases66. Indeed, serum half-life of the FANA-PS-modified Fz12B at 37°C (16 h)(Fig. 3d) was increased by >10-fold compared with a FANA-only version or the DNAzyme 10-23KRasC (both ~ 1 h), without affecting XNAzyme activity.

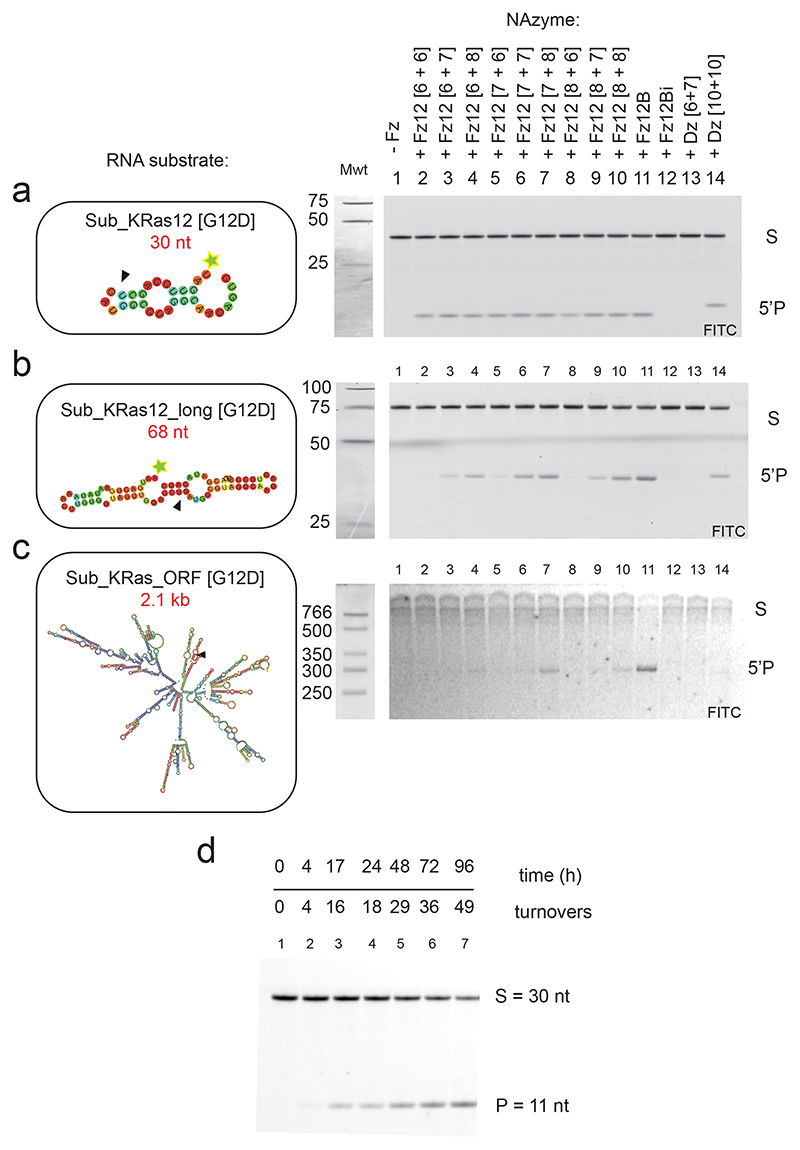

Capacity of the KRAS-targeting XNAzyme to cleave long, structured mRNA

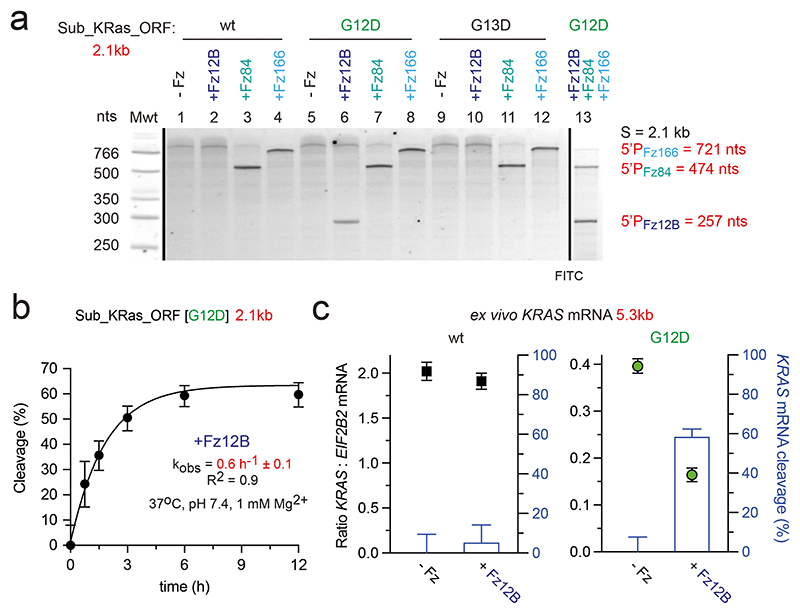

DNA- and XNAzyme activity is commonly measured on short synthetic RNA substrates. However, these poorly recapitulate in vivo targets, which are long (often multi kb), highly structured mRNAs. Next, we sought to test XNAzyme activity on realistic mRNA targets under quasi-physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 37 °C). To this end, we prepared 5’-FITC-labelled 2.1 kb versions of the KRAS transcript (“Sub_KRas_ORF”) encoding the full open reading frame (ORF) and untranslated regions, analogous to the wild-type KRAS mRNA, as well as two variants bearing the KRAS c.35G>A [G12D] and KRAS c.38G>A [G13D] mutations, respectively. As previously, Fz12B showed allele-specific cleavage of only the KRAS c.35G>A [G12D] transcript, as judged by a 5’ cleavage product of the expected size (257 nt), but did not cleave either wild-type or other mutant KRAS transcripts (c.38G>A [G13D])(Fig. 4a). In contrast, XNAzymes specific for alternative sites in the KRAS mRNA (FR6_1_KRas84 /FR6_1_KRas166; without allelic specificity (Fig. 2a,b)) yielded cleavage products of the expected size (474 nt and 721 nt, respectively) on all three KRAS mRNA substrates (Fig. 4a). Finally, we performed a one pot cleavage reaction comprising all three XNAzymes (Fz12B / FR6_1_KRas84 / FR6_1_KRas166) observing all three expected cleavage products indicating that a cocktail of XNAzymes do not interfere with each other and may - in future - be combined to jointly target KRAS (or other) mRNA targets. The single-turnover rate constant of FR6_1_KRas12B on the 2.1 kb RNA Sub_KRas_ORF [G12D] under quasi-physiological conditions (kobs = 0.6 h-1 ± 0.1) (Fig. 4b), determined by digital droplet qRT-PCR (ddPCR) (with multiplexed primer and probe sets for the target site in KRAS exon 2 and a non-target site in exon 4), compares favorably with the rate constant determined using the short 30 nt Sub_KRas12 [G12D] RNA substrate (kobs = 0.75 h-1 ± 0.07)(Fig. 3c). Indeed, turnover rates of all three KRAS-targeting XNAzymes on the 2.1 kb synthetic transcript appear to be broadly similar (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 4. KRAS-targeting XNAzymes can invade and cleave long, structured mRNA in quasi-physiological conditions.

(a) Urea-PAGE gel showing reactions of RNA Sub_KRas_ORF [wt, G12D or G12D] (1 uM) with XNAzymes (5 uM) FR6_1_KRas12B (Fz12B), FR6_1_KRas84 (Fz84), FR6_1_KRas166 (Fz166), or a cocktail of all three XNAzymes (6 h). (b) Graph showing bimolecular pre-steady state reaction of RNA Sub_KRas_ORF [G12D] (1 uM) with Fz12B (2.5 uM) analysed by digital droplet qRT-PCR (ddPCR) with multiplexed primer and probe sets for the target site in KRAS exon 2 and a non-target site in exon 4. Error bars show ddPCR total error of three independent replicates. (c) Graphs showing ddPCR assay for reaction between XNAzyme Fz12B (2.5 uM) and ex vivo KRAS mRNA in total RNA purified from (left graph) RKOKRAS wt/wt or (right graph) RKOKRAS G12D/G12D cells (200 ng/ul)(12 h, 37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+), analysed using multiplexed primer and probe sets for the target site in KRAS exon 2 and a non-target reference gene, EIF2B2. On both graphs, ratios of wt KRAS:EIF2B2 (black squares) and G12D KRAS:EIF2B2 (green circles) are plotted on left y-axis and the difference between samples incubated with Fz12B or buffer alone (i.e. KRAS mRNA cleavage, blue bars) is plotted on the right y-axis). All cleavage reactions shown were performed in quasi-physiological conditions (37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+).

Finally, we tested XNAzyme activity ex vivo on total cellular RNA to exclude the possibility that mRNA modifications or the presence of other cellular RNA could interfere with XNAzyme-mediated cleavage and to explore whether XNAzyme reaction rates on real transcripts would be sufficient to outpace the in vivo turnover rate of KRAS mRNA (estimated at ~0.25 h-1)67. KRAS mRNA cleavage by FR6_1_KRas12B (2.5 μM) in the context of total RNA (200 ng/μl)(including the full (5.3 kb) KRAS mRNA transcript) from RKO colon carcinoma cells (RRID: CVCL_0504) homozygous for either wild-type KRAS or the c.35G>A [G12D] was determined by quantifying cDNA using ddPCR (Fig. 4c). Consistent with previous results, KRAS mRNA cleavage (after 12 h under quasi-physiological conditions) was only observed with total RNA derived from the KRAS G12D cell line, but not from KRAS wild-type cells (Fig. 4c).

Identification of an inactive XNAzyme control

Heteroduplex formation of ≥6 base-pairs between both FANA and DNA oligonucleotides and RNA targets recruit cellular RNase H for cleavage within the heteroduplex, enabling ‘antisense’-mediated gene silencing’68–70. Indeed, the bulk of previously observed in vivo activity of 10-23 DNAzymes are now attributed to RNase H recruitment21–24. In order to distinguish bona fide XNAzyme catalysis-mediated effects from potential ‘antisense’ activity, we engineered a catalytically-inactive variant of the FR6_1_KRas12B (Fz12B) XNAzyme. A mutation screen of the catalytic core (Supplementary Fig. 3a) revealed mutations that abolish XNAzyme activity, including fG27fA, predicted to be involved in base-pairing within the catalytic core, and confirmed not to reduce substrate binding (Supplementary Fig. 6). We therefore synthesized the inactive [fG27fA] mutant version of Fz12B (including the FANA-PS modifications), “FR6_1_KRas12Bi” (Fz12Bi), as an inactive control for in vivo experiments.

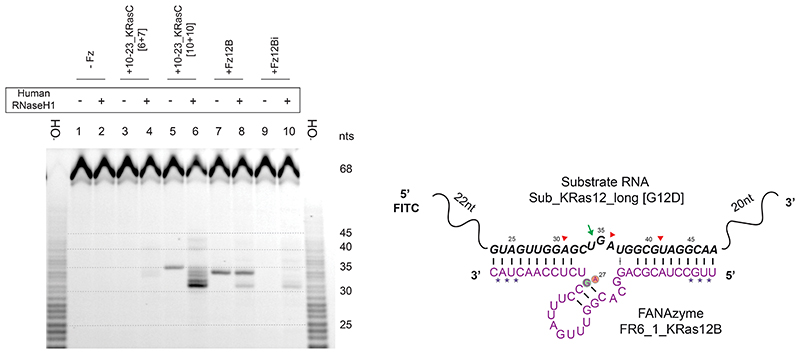

Capacity of the KRAS-targeting XNAzyme and inactive control to trigger RNase H

Next, we investigated the extent and potential sites of RNase H-mediated cleavage of substrate RNA in vitro using both the 30 nt Sub_KRas12 RNA and a longer 68 nt version Sub_KRas12_long (Supplementary Fig. 7, Extended Data Fig. 4). Again, DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC was included as a benchmark. However, the original 10-23_KRasC has shorter binding arms ([6+7]) than those of Fz12B ([10+10]), and was found to be unable to invade and cleave the more structured 68 nt substrate under quasi-physiological conditions (Extended Data Fig. 3). Therefore, a version of 10-23_KRasC with [10+10] arms was also synthesized. We then mapped patterns of RNAse H-mediated cleavage triggered by different XNA- and DNAzymes. RNase H-mediated cleavage patterns by active Fz12B and the inactive Fz12Bi were identical between wild-type and G12D Sub_KRas12 RNA (Supplementary Fig. 7a), and consistent with the Sub_KRas12_long [G12D] substrate (Supplementary Fig. 7b) and with expected complementarity formed between the Fz12B substrate-binding arms and their RNA targets. In addition, we observed an RNase H cleavage site close to the XNAzyme’s cleavage site (+2) unique to the inactive Fz12Bi, despite the lack of predicted complementarity in this region. This suggests that the inactive Fz12Bi has similar, or potentially enhanced, capacity to trigger RNase H-mediated antisense effects compared to the active XNAzyme Fz12B, thus providing a stringent control for in vivo gene silencing experiments and the disentanglement of the respective contributions of RNase H and XNAzyme-mediated cleavage to overall RNA knockdown (see below).

Interestingly, although E.coli RNase H data suggested a broadly similar capacity of XNAzyme Fz12B and DNAzyme 10-23KRasC to trigger RNase H (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), when a human RNase H1 assay was used instead (Extended Data Fig. 4), the Fz12B XNAzyme appeared to induce less RNase H1-mediated cutting than the analogous DNAzyme. Although a more detailed study would be needed to quantify differences in DNA- and FANA-mediated RNase H activation, this is broadly consistent with previous observations that whilst chimeric FANA-DNA oligonucleotides enhance RNase H1 activity in vivo compared with DNA, fully-FANA and phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides appear to reduce it68. Although the 10-23KRasC [6+7] DNAzyme was, by itself, unable to cleave these RNA substrates in the assay conditions, induction of RNase H activity is clearly apparent (Supplementary Fig. 7b, Extended Data Fig. 4), suggesting that RNase H, at least in vitro, may enhance binding to structured RNA substrates, enabling RNase H-, but not DNAzyme-mediated catalysis.

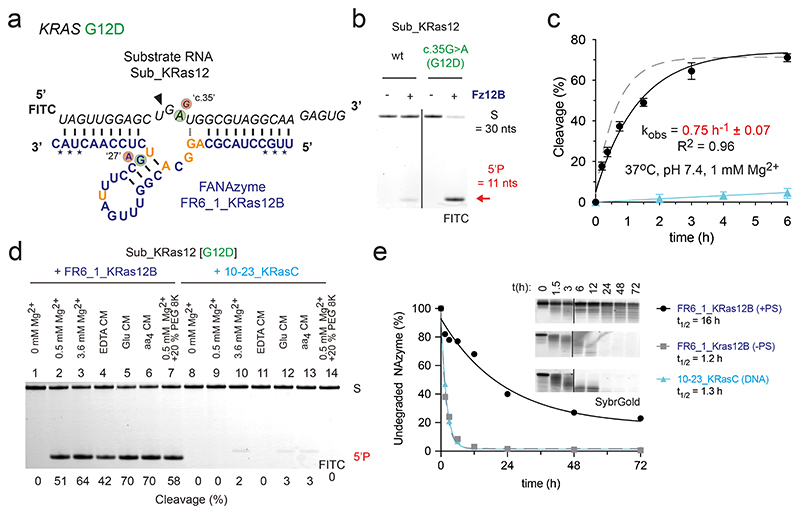

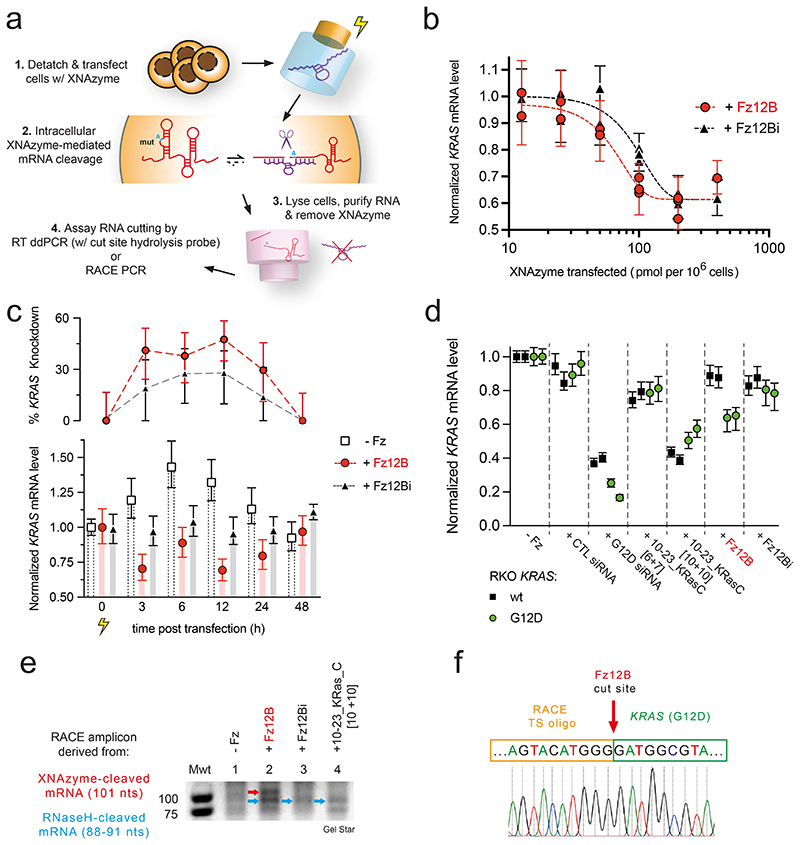

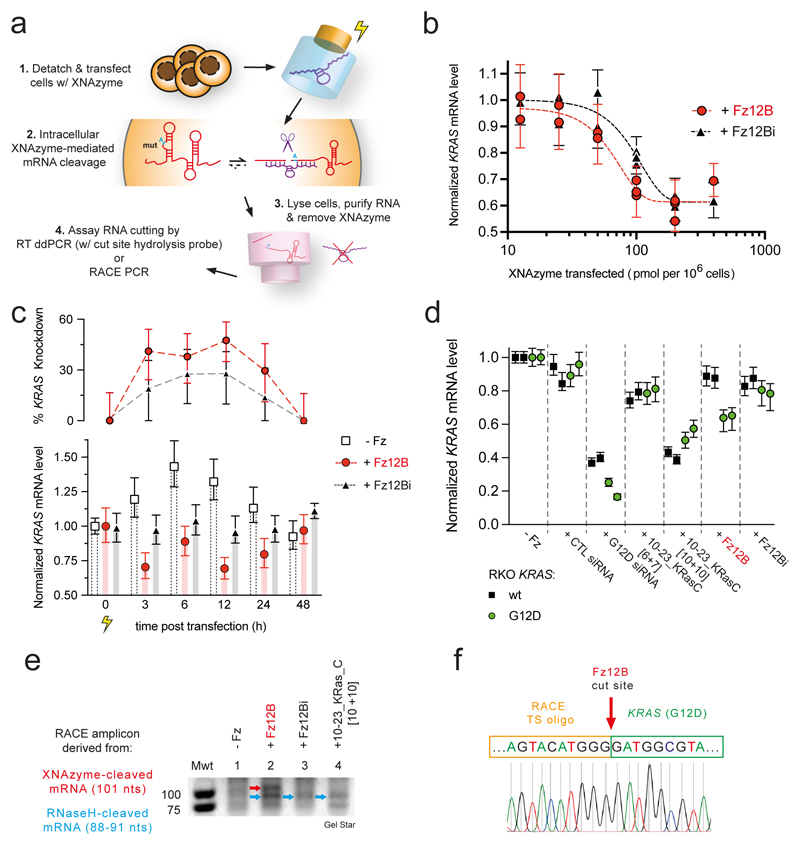

Activity and specificity of the KRAS-targeting XNAzyme inside live cells

Having established that Fz12B was able to invade and cleave native structured versions of KRAS [G12D] mRNA under quasi-physiological conditions with allelic specificity and a sufficient catalytic rate to outpace KRAS mRNA turnover (Fig. 3, 4), we sought to establish whether bona fide XNAzyme activity and KRAS mRNA knockdown could be detected in vivo in RKO colon carcinoma cells71 engineered to be homozygous for the KRAS G12D (c.35G>A) mutation (RKO KRASG12D/G12D)(Fig. 5a,b)(‘Onco-Ref’, AccuRef / Applied StemCell, USA). To this end, we transfected a range of concentrations of either active XNAzyme Fz12B or the catalytically inactive Fz12Bi control. After transfection, cells were returned to culture and KRAS mRNA levels - relative to cells transfected with buffer alone - were determined by a multiplex ddPCR assay (with an in-sample reference, EIF2B2)(Fig. 5a), following rigorous RNA extraction and purification to prevent XNAzyme carryover activity (Supplementary Fig. 8). KRAS mRNA knockdown dose response relationships were observed for both the active XNAzyme and the inactive control (baseline RNase H recruitment), but with different inflection points: At their respective half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50), the active XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12B requires approximately half the dose (IC50 = 60 pmol/106 cells) compared with the inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi (EC50 = 100 pmol/106 cells)(Fig. 5b). This suggests that while – as expected from in vitro RNase H recruitment experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7, Extended Data Fig. 4) – an antisense-type mechanism is a component of the observed KRAS mRNA knockdown, XNAzyme catalytic activity contributes significantly (ca. 50%) to the total RNA knockdown effect. Indeed, an active XNAzyme is necessary to achieve a knockdown effect at lower doses.

Figure 5. The KRAS G12D-targeting XNAzyme retains catalytic activity inside RKO cells and performs G12D-specific mRNA knockdown.

(a) Scheme outlining XNAzyme transfection and measurement of intracellular XNAzyme-mediated mRNA knockdown. (b) Dose response curves showing G12D mutant KRAS mRNA levels (relative to reference EIF2B2 mRNA and normalized to cells transfected with buffer alone) in RKO KRASG12D/G12D colon carcinoma cells 3 h after transfection with XNAzyme “FR6_1_KRas12B” (Fz12B)(red circles and dashed red line) or the catalytically inactive mutant “FR6_1_KRas12Bi” (Fz12Bi)(black triangles and dashed black line). (c) Time course of G12D mutant KRAS mRNA knockdown in RKO KRA G12D/G12D cells following transfection with buffer alone (white squares and bars), XNAzyme Fz12B (red circles and bars) or inactive Fz12Bi (black triangles and grey bars)(100 pmol / 106 cells). (d) Wild-type (wt) (black squares) or G12D mutant (green circles) KRAS mRNA levels (relative to reference EIF2B2 mRNA and normalized to cells transfected with buffer alone) in homozygous RKO KRASwt/wt or RKO KRASG12D/G12D cells, respectively, 3 h after transfection with XNAzyme Fz12B, inactive Fz12Bi or DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC (with short [6+7] or long [10+10] substrate-binding arms)(90 pmol / 106 cells), or 6 h after transfection with KRAS-specific siRNA (targeted to the same region of KRAS G12D, or control siRNA (2 pmol / 106 cells). Each datum represents an independent biological replicate and error bars show ddPCR total error. (e) Detail of agarose gel showing amplicons from 5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5’ RACE PCR) reactions templated by cDNA derived from RKO KRAS G12D/G12D cells 3 h after transfections with XNAzyme or DNAzyme as shown. Red arrow indicates band TA cloned and (f) Sanger sequenced, revealing sequence derived from 3’ product of XNAzyme-mediated cleavage of KRAS mRNA (cf. Fig. 3a), appended to a RACE template switching oligo (see Supplementary Fig. 9 for further details).

Next, we sought to determine the duration of intracellular XNAzyme activity. This time, RKO KRASG12D/G12D were transfected with a single concentration (100 pmol/106 cells) of active FR6_1_KRas12B, inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi, or buffer control, and cells harvested for mRNA quantification by ddPCR at regular time points up to 48 h (Fig. 5c). Although the buffer-only condition revealed that the transfection workup appears to trigger a temporary increase in KRAS mRNA levels (up to 1.4-fold after 6 h), the active XNAzyme consistently induced a greater relative knockdown of KRAS mRNA (peaking at ~50% at 12 h) than the catalytically inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi (~25% at 12 h)(Fig. 5c). Active XNAzyme-dependent KRAS knockdown was observed up to 24 h, but disappears by 48 h (Fig. 5c), broadly consistent with FR6_1_KRas12B biostability (Fig. 3e).

Next, to examine the specificity of the XNAzyme-mediated knockdown, we transfected isogenic RKO KRASG12D/G12D and RKO KRASwt/wt cells with (90 pmol / 106 cells) active Fz12B, inactive Fz12Bi, buffer control, as well as DNAzymes 10-23_KRasC [6+7], 10-23_KRasC [10+10], and (2 pmol / 106 cells) two siRNA controls comprising an siRNA targeting the same region of the KRAS G12D mRNA, or a negative control siRNA. Cells were incubated for 3 h (DNA- / XNAzyme), or 6 h (siRNA), and mRNA was extracted and quantified by ddPCR (Fig. 5d). The KRAS G12D siRNA successfully knocked down KRAS mRNA in both KRASG12D/G12D cells (~80 %) and KRASwt/wt cells (~65%)(Fig. 5d) indicating modest allelic specificity (1.23x). In contrast, and consistent with previous results, KRAS mRNA knockdown (~40 %) was only observed when active XNAzyme Fz12B was transfected into KRASG12D/G12D cells at the above dose (Fig. 5d) with little to no knockdown in KRASwt/wt cells (~10%), or with catalytically inactive Fz12Bi in either genetic background. This strongly suggests that the observed knockdown in KRASG12D/G12D cells is due to intracellular XNAzyme-mediated KRAS mRNA cleavage (with at least 3x allelic specificity) and not an antisense-mediated effect. KRAS knockdown (~50%) was also observed with DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC [10+10] but in both KRASG12D/G12D and KRASwt/wt cells (Fig. 5d), inconsistent with its cleavage specificity and inability to invade full-length KRAS transcript (in the absence of RNase H)(Extended Data Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 7) indicating an antisense or alternative non-specific effect. Indeed, a very modest knockdown (~20%) was also apparent with 10-23_KRasC [6+7], but again without allelic specificity (Fig. 5d), correlating with relative RNase H recruitment by 10-23_KRasC [6+7] vs 10-23_KRasC [10+10] (Supplementary Fig. 7, Extended Data Fig. 4).

Finally, we sought to elaborate XNAzyme-mediated knockdown in an alternative cell line (Extended Data Fig. 5). The pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line, PANC-172, is heterozygous for the KRAS G12D (c.35G>A) mutation, allowing us to examine whether the allele-specific mRNA targeting by Fz12B could be performed within the same cell, using ddPCR assays for total KRAS mRNA and the ratio of G12D vs wt KRAS mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Fz12B-mediated knockdown of total KRAS mRNA followed a dose-response relationship (Extended Data Fig. 5c), with 10-20 fold lower amounts of XNAzyme required in comparison with RKO cells (Fig. 5b). Inactive Fz12Bi appeared to induce similar (or higher) levels of knockdown in PANC-1 (Extended Data Fig. 5c), possibly reflecting the slightly higher capacity for RNase H recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 7). In PANC-1 cells, whilst total KRAS mRNA is reduced by both active and inactive XNAzymes, at all doses the inactive was found to skew the ratio of G12D : wt KRAS mRNA (2.0 in buffer controls) toward a higher proportion of G12D (2.25-2.5 with Fz12Bi), whilst the active XNAzyme maintained or reduced it (Extended Data Fig. 5c). These observations suggest two components of overall knockdown activity: 1) an RNase H-mediated effect that induces an equal degree of knockdown in both mutant and wild-type mRNA alleles (but is more efficient in the inactive XNAzyme) and 2) in the case of the active XNAzyme, an accompanying allele-specific activity that specifically knocks down only the G12D KRAS mRNA (summarised in Extended Data Fig. 5d).

Detection of XNAzyme cleavage products by RACE PCR and Sanger sequencing

To further confirm that the observed G12D-specifc KRAS mRNA knockdown was due to XNAzyme activity (rather than a potential unknown effect), we sought to directly detect the KRAS mRNA (3’) cleavage products from RKO cells using 5’ RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends) PCR (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Although challenging (presumably due to the high GC content and secondary structure of the KRAS mRNA 5’ terminus, and the transient half-life of cleaved mRNA fragments), RACE amplicons of the expected molecular weight (Supplementary Fig. 9b) derived from FR6_1_KRas12B XNAzyme-mediated cleavage of KRAS G12D mRNA in RKO KRASG12D/G12D cells were observed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. 9c) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 9d) to derive from KRAS mRNA 5’ termini with the expected post-cleavage cut site sequence. In contrast, RACE PCR amplicons when RKO KRASG12D/G12D cells were treated with the inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi, or the DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC [10+10], only contained sequences corresponding to putative RNase H1-mediated cleavage sites (Supplementary Fig. 9b,c,d, 8d) again supporting our observation of significant RNase H recruitment and non-allele-specific knockdown.

Discussion

The chemical or structural features of different nucleic acid chemistries that may provide for optimal XNAzyme (or modified DNAzyme) activity at physiological [Mg2+] as well as enabling invasion and cleavage of structured (m)RNA targets, while minimizing non-specific antisense effects, remain an active area of investigation. Our work begins to outline relevant parameters and pitfalls in the elaboration of potent and specific gene silencing agents based on XNA- or DNAzyme activity. Among these, the higher thermodynamic stability of FANA-RNA compared DNA-RNA heteroduplexes certainly improves RNA target binding and strand invasion. Indeed, FANA has previously been shown to improve the activity of siRNA73, ASOs66,74 and DNAzymes49. Additionally, the even higher thermodynamic stability of FANA x FANA homoduplexes75,76 compared with DNA x DNA or RNA x RNA, due to the involvement of the 2’F group in favorable inter-residual pseudo-hydrogen bonds and increased backbone rigidity derived from the non-canonical O4’-endo (east) conformation of the fluorinated arabinose sugar77, may stabilize the catalytic core and reduce the need for counter-ions for folding or holoenzyme assembly. Indeed, this is consistent with the observed emergence of an additional FANA base-pair (in Resel 1 (Supplementary Fig. 3c) / FR6_1_Kras12B (Fig. 3a)) upon re-selection of the FR6_1 catalytic core in low magnesium conditions. This bodes well for future improvement of XNAzymes utilizing an increasing range of XNA backbone chemistries that display even more stable duplex formation and biostability54, although in our case simple phosphorothioate modifications of XNAzyme 5’ and 3’ ends was sufficient to impart a significant (~24 h) in vivo half-life. Furthermore, parameters such as biostability, rigidity and strong substrate binding may have to be balanced against catalytic turnover, as a multi-turnover catalytic cycle necessarily involves release of cleaved RNAs and excessive rigidity and RNA binding would likely lead to product inhibition. On this parameter spectrum, FANA appears to occupy a favorable position as shown by the superior performance of FANAzymes compared to engineered equivalent DNAzyme benchmarked under physiological conditions.

Other considerations may include the propensity of a given chemistry to recruit RNase H activity and / or trigger innate immunity (via pattern recognition receptors such as TLR9 and the cGAS-STING pathway78,79). FANA ASOs appear not to trigger such DNA-sensing mechanisms68, however as observed previously69, and again here, both DNA and FANA share a potent ability to trigger RNase H mediated antisense effects. Whilst desirable from the perspective of achieving maximal target mRNA knockdown, antisense effects appear to lack the single nucleotide specificity of the knockdown effected by XNAzyme-mediated RNA cleavage.

Indeed, due to the capacity of the FR6_1 XNAzyme for allele-selective mRNA cleavage, we were able to separate the contributions of XNAzyme-mediated RNA cleavage to RNA knockdown from the antisense effect. Thus while both effects contribute to overall knockdown, allelic discrimination accessible via XNAzyme-mediated RNA cleavage may be beneficial where very high specificity is required. Indeed, we would argue that is may be the key advantage of XNAzymes and oligonucleotide catalysts in general over competing gene silencing strategies such as ASOs or siRNAs or CRISPRi80. Should an antisense effect be completely undesirable, alternative nucleic acid chemistries that do not recruit RNase H are available for development including chemistries validated in licensed nucleic acid drugs such as 2’F-, 2’OMe- and methoxyethyl-RNAs as well as phosphorothioate modifications.

The RNase H recruitment assays show the pitfalls of simplistic assumptions regarding the mechanistic basis of observed in vivo knockdown activity without rigorous controls51. Furthermore, we also encountered methodological pitfalls that can equally conspire to produce ‘false positives’. Typically, mRNA quantification involves removal of genomic DNA by DNase treatment, as part of the workup. However, due to the increased resistance of FANA to degradation, standard DNase treatment fails to fully remove XNAzymes (or indeed modified DNAzymes) from a sample (Supplementary Fig. 8a) and these continue to perform RNA cleavage in both the buffer and incubation conditions used in the DNase step (Supplementary Fig. 8a), as well as those of the subsequent RT 1st strand synthesis reaction (Supplementary Fig. 8b). This leads to sequence specific cleavage of target RNA and an apparent sequence specific knockdown of RNA levels i.e., a false positive due to this ex vivo activity. Moreover, due to the high thermodynamic stability FANA x RNA heteroduplexes, FANA containing XNAzymes (and DNAzymes51) can have an inhibitory effect on RT-PCR, independently of catalytic activity. This results in an apparent lower level of RNA as quantified by ddPCR (Supplementary Fig. 8c) and again suggests an apparent RNA target knockdown, another false positive. This effect can be observed even in negative (unreacted) controls and in samples analyzed by Urea-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 8d) and confirmed for absence of RNA cleavage. In order to obtain reliable results, we therefore developed a meticulous workflow involving silica-based column RNA purification with rigorous wash steps to fully remove FANA oligomers from total RNA (Supplementary Fig. 8d), enabling bona fide measurements of XNAzyme-mediated in vivo RNA cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 8c), confirmed by RACE PCR (positive control reactions in Supplementary Fig. 9c).

The FANA XNAzyme, FR6_1 is a modular XNAzyme that - akin to the classic “10-23” DNAzyme - can be reprogrammed to different RNA targets although with some remaining sequence biases that required reselection for optimal activity. Its catalytic power is the best reported to date for an XNAzyme56,57 or FANA-modified catalyst49 and unlike previously-described DNA- and XNAzymes it shows high allele-specific RNA endonuclease activity on long, structured RNA targets under physiological conditions. Although, the ability of the FANA chemistry to recruit RNase H clearly induced a substantial antisense-type effect, we were able to conclusively show that XNAzyme RNA endonuclease activity contributes significantly to the gene knockdown effect (especially at low concentrations), providing a benchmark for the development of more potent XNAzyme-based gene silencing strategies. Such improvements may come from more judicious choice of target RNA sequences as well as further evolutionary improvement or re-selection of XNAzymes for maximal catalytic activity in the intracellular milieu, as well as the use of XNAzyme cocktails targeting the same RNA. Future work should also include an extension of XNAzyme technology to a wider range of chemistries e.g., comprising both backbone and base modifications32 in order to access more diverse catalytic mechanisms. Such approaches should benefit from an expanded toolbox of synthetic genetics with an ever-increasing range of chemistries and engineered polymerases and reverse transcriptases for their synthesis, replication and evolution. These tools may aid in unlocking the unquestionable potential of oligonucleotide catalysts for clinical applications both as precision biosensors81 and therapeutics.

Methods

Preparation of XNA, DNA and RNA oligonucleotides

All oligonucleotide sequences used in the study are shown in Supplementary Table 1. DNA, RNA, and 2’-O-Methyl-RNA- and LNA-modified DNA or RNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA technologies (Belgium) or Sigma-Aldrich / Merck (USA), except synthetic KRAS transcripts (“Sub_KRas_ORF”)(see below). FANA and phosphorothioate-modifed FANA oligonucleotides were prepared either by solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry (by Sigma-Aldrich / Merck (USA)) or enzymatically, using RNA primers, DNA templates, triphosphates of FANA (faNTPs)(Metkinen Chemistry, Finland), and polymerase D4K as described previously2,7. For characterization experiments, single-stranded XNAzymes were prepared by synthesis with RNA primer “P2_Ebo” and appropriate 3’ biotinylated DNA template (e.g. “FR6_1_KRas12temp”), enabling subsequent capture and elution from streptavidin magnetic beads (Dynabeads MyOne C1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and removal of the RNA primer by hydrolysis, as described previously7. All oligonucleotides were purified by denaturing urea-PAGE and ethanol-precipitated from filtrates of freeze-thawed gel mash. Prior to initiation of reactions or transfection into cells, all XNA libraries, XNAzymes or DNAzymes were annealed in nuclease-free water (Qiagen, Germany) by incubation at 80 °C for 60 s, then cooled to room temperature for 5 min.

Partial alkaline hydrolysis of RNA substrates for use as electrophoresis size standards was performed by incubation at 65 °C in 20 mM sodium hydroxide (pH 12) for 4 min, then neutralized with 1M Tris pH 7. Partial RNase T1 digestion was achieved by incubation at 55 °C in 0.1 U/ul RNase T1 (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, USA) in 30 mM sodium acetate (pH 5) for 10 min, then stopped in 7 M urea 1.5 mM EDTA.

Preparation of synthetic KRAS transcripts

Long (2.1 kb) 5’ fluorophore-labelled RNAs encoding the complete (wild-type) KRAS ORF and UTRs (“Sub_KRas_ORF”) were using prepared using an SP6 transcription kit (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using a human KRAS ORF cDNA clone (in plasmid pCMV6-XL6)(Cat. No. SC109374, Origene, USA) linearized with XmaI (NEB, USA) as template, and a FITC-AG transcription starter (IBA Life Sciences, Germany). Mutations c.35G>A [G12D] or c.38G>A [G13D] were introduced into the KRAS plasmid using a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using primers “Quik_G35A_Fw” and “Quik_G35A_Rev”, or “Quik_G38A_Fw” and “Quik_G38A_Rev”, respectively.

RNA endonuclease XNAzyme selections

A broadly similar ‘X-SELEX’ strategy was used for XNAzyme selection as described previously2,7. Briefly, single-stranded FANA libraries with RNA substrates covalently attached for cleavage in cis (see Figs. S1 and S4) were prepared using unbiotinylated DNA templates (“N40libtemp_Ebo” and “N20libtemp_Ebo” for Ebola RNA selections, “FR6_1libtemp_KRas12” for KRAS RNA re-selection), and 5’ biotinylated DNA-RNA primer (“P1_Ebo” for Ebola RNA selections, “P1_KRas12” for KRAS RNA re-selection).

For Ebola RNA selections, reactions were performed at 17 °C in high magnesium selection buffer (30 mM EPPS pH 8.5, 150 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 U/ul RNasein RNase inhibitor (Promega, USA)). 0.5-1 nmol of each library was incubated at 10 uM for 64 h in round 1; in subsequent rounds 10-50 pmol selection pools were prepared and reacted at 1 uM, for sequentially decreasing times, settling on 6 h in rounds 5 and 6. The two libraries (N40 and N20) were initially selected separately, then pooled after round 4. For KRAS RNA re-selection, reactions were performed at 37 °C in quasi-physiological buffer (30 mM EPPS pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 U/ul RNasein). 400 pmol library was incubated at 10 uM for 1 h in round 1; in subsequent rounds 10–50 pmol selection pool were prepared and reacted at 1 uM, for 10 min in rounds 2-6. Reactions were stopped by addition of PAGE gel loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue) and separated by Urea-PAGE. Self-cleaved library members were extracted from the appropriate region of the gel as described above and a futher incubation with streptavidin beads was performed to further deplete uncleaved RNA-XNAs7.

FANA reverse transcription was performed using polymerase RTI521L, as described previously2,7, with 5’ biotinylated primer “RT_Ebo”. First-stand cDNA was isolated using streptavidin beads, eluted by incubation in nuclease-free water for 2 min at 80 °C, then amplified by a two-step nested PCR strategy using OneTaq Hot Start master mix (NEB, USA). The first ‘out-nested’ PCRs used 0.5 uM forward primer “dP2_Ebo” (for Ebola RNA selections) or “dP2_KRas12” (For KRAS RNA re-selection), and 0.5 uM reverse primer “RT_Ebo_out”, cycling conditions were 94 °C for 1min, 20–35 x [94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s], 72 °C for 2 min. Following the first PCR, primers were digested using ExoSAP (Ambion/Life Technologies, USA), which was then heat inactivated, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Second step (‘in-nest’) PCRs used using 1 ul of unpurified out-nest PCR product as template in a 50 ul reaction with 0.5 uM forward primer “dP2_Ebo” (for Ebola RNA selections) or “dP2_KRas12” (For KRAS RNA re-selection), and 0.5 uM reverse primer “RT_Ebo_in”, cycling conditions as above. Reactions were analysed by electrophoresis on 4% NGQT-1000 agarose (Thistle Scientific, UK) gels containing GelStar stain (Lonza, Switzerland). Bands of appropriate size were purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified DNA was used as the polyclonal template for either sequencing library PCR (see below) or preparative PCR (‘in-nest’ PCR scaled up to 500 ul) for generation of DNA templates for XNA synthesis. Single-stranded DNA templates were isolated using streptavidin beads and ethanol-precipitated before further use.

Deep sequencing

XNAzyme selection pools were deep sequenced using a Miseq system (Illumina, USA) following preparation of sequencing libraries by PCR to append adapter sequences, as described previously2,7, using 0.1 uM forward primers of the series “P5_P2_Ebo” (for Ebola RNA selections), or “P5_P2_Kras12” (for KRAS RNA re-selection), and 0.1 uM reverse primer “P3_RT_Ebo_in”. Data was analyzed using the cloud-based Galaxy server8. The 50 (for Ebola RNA selection) or 10 (for KRAS RNA re-selection) most abundant sequences were aligned using ClustalW 1.83 in MacVector (MacVector, Inc., USA).

Single-turnover XNAzyme and DNAzyme reactions in trans

PAGE-purified XNAzymes or DNAzyme and all-RNA substrates were annealed separately as described above and reacted in quasi-physiological buffer (30 mM EPPS pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2) at 37 °C, or high magnesium selection buffer (30 mM EPPS pH 8.5, 150 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl2) at 17 °C, unless stated otherwise in figure legends. In pH titration experiments, reactions were performed in 150 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2 plus 50mM buffer as follows: MES (pH 5.0 – 6.0), EPPS (pH 6.5–8.75), CHES (pH 9.0– 10.0) or CAPS (pH 10.25–11.0). For characterization of bivalent metal ion requirements, reactions were performed in 30 mM EPPS pH 8.5, 150 mM KCl, with MgCl2 substituted by chlorides of the Irving-Williams series (100 uM-10mM). Reactions were stopped by addition of PAGE gel loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue) and separated by Urea-PAGE. Fluorophore-labelled RNA substrates were visualized using a Typhoon Trio (GE Heathcare, USA) or FLA-5000 scanner (Fujifilm, Japan) and quantified using ImageQuant TL (GE Heathcare) or Fiji9. Reactions with 5’ fluorophore-labelled synthetic KRAS transcript (“Sub_KRas_ORF”) were analysed by both Urea-PAGE and RT-ddPCR (see below).

Pseudo first-order reaction rates (kobs) under single-turnover pre-steady-state (Km/kcat) conditions were determined from time courses with 5 uM catalyst and 1 uM substrate; samples were taken and reactions stopped at appropriate intervals by snap-freezing on dry ice in excess PAGE gel loading buffer, or (in the case or reactions with Sub_KRas_ORF) buffer RLT (Qiagen, Germany). Quantification data from three independent replicates per time course were fit using Prism 9 (GraphPad), as described previously2.

Multiple-turnover XNAzyme reactions in trans

For multiple turnover reactions, 1 uM RNA substrate was reacted with 10 nM XNAzyme in high magnesium selection buffer or quasi-physiological buffer. Michaelis-Menten kinetics for XNAzyme FR6_1 were determined by obtaining the initial velocity (V0) from a simple linear regression of data from the first 10-20% of the cleavage reaction with a series of 9 concentrations of the RNA substrate Sub_Ebo (20 nM, 31.3 nM, 62.5 nM, 125 nM, 250 nM, 400 nM, 500 nM, 800 nM, 1000 nM)[S] with 10 nM FR6_1 [E], in triplicate; kcat and KM were then determined by a non-linear least squares fit of a plot of V0 versus [S] to the Michael-Menten equation:

| (1) |

XNAzyme substrate binding

XNAzyme “FR6_1_KRas12” or the inactive [27G>A] mutant “FR6_1_KRas12i”, and RNAs “Sub_KRas12 [wt]” or “Sub_KRas12 [G12D]” were annealed separately in 10mM EPPS pH7.4 at 80 °C for 60 s, then cooled to room temperature over 5 min. XNAzymes (1 - 64 nM) and RNA (1 nM) were mixed and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C in quasi-physiological buffer. Samples were mixed with glycerol (10% v/v final) and analyzed by non-denaturing PAGE using 10% acrylamide Tris-Borate EDTA gels (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, USA). Values for the concentration required to form half of the total complex (C50) were determined by non-linear regression using Prism 9 (GraphPad).

Mass spectrometry

1 uM “Sub_Ebo” RNA was reacted with XNAzyme “FR6_1” under high magnesium selection conditions (20 h, 17 °C) and the 5’ RNA cleavage product purified by Urea-PAGE, extracted from macerated gel using a 0.22 uM centrifugal filter (Corning, USA) as described previously7 and ethanol precipitated. The cleavage product was resuspended in nuclease-free water and analysed by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry using an Ultraflex III TOF-TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonik, Germany) in positive ion mode as described previously2. Expected masses were calculated using the Mongo Oligo Mass Calculator v.2.06. The 5’ “6FAM” (6-Carboxyfluorescien)(IDT, USA) has a mass of 537.5 Da.

Phosphatase assay

PAGE-purified Sub_EBo 5’ cleavage product was incubated in 10 mM glycine pH 2.5 or pH 8.5 (30 min, room temperature), then treated with rAPid alkaline phosphatase (Roche, Switzerland) in manufacturer’s buffer (30 min, 37 °C), before heat inactivation (2 min, 75 °C) and addition of PAGE gel loading buffer. The presence or absence of cleavable (2’ or 3’ monophosphate) or non-cleavable (2’,3’-cyclic) terminal phosphate was determined by Urea-PAGE electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA).

Biostability assay

PAGE-purified XNAzymes FR6_1_KRas12B (including FANA-phosphorothioate (PS) modifications), FR6_1_KRas12 (without PS modifications) and DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC were annealed in nuclease-free water (Qiagen, Germany) by incubation at 80 °C for 60 s, cooled to room temperature for 5 min, then incubated (at 5 uM final) at 37 °C in 95 % human serum (Sigma-Aldrich / Merck) for 72 h. Samples were taken and reactions stopped at appropriate intervals by snap-freezing on dry ice in excess PAGE gel loading buffer. The proportion of undegraded full-length catalyst was determined by Urea-PAGE; gels were stained with SYBR Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and imaged as described above.

RNase H assays

E.coli RNase H assays were performed by incubating co-annealed 1 uM substrate (either Sub_KRas12 [wt] or [G12D], or Sub_KRas12_long [G12D]) and 5 uM active XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12B, inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi, or DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC ([6+7] and [10+10] versions) with 0.05 unit/uL E.coli RNase H (NEB, USA) in NEB RNase H buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT, 3 mM MgCl2), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (20 min at 37 °C). Human RNase H assays were performed using co-annealed 0.25 uM substrate and 0.25 uM enzyme, 0.01 ug/ul recombinant human RNase H1 (RayBiotech, USA) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2 (1 h at 37 °C). Reactions were stopped by the addition of an excess of PAGE loading buffer and snap-frozen on dry ice.

Cell culture and XNAzyme transfection

Onco-Ref RKO (human colon carcinoma) cells (RRID: CVCL_0504) homozygous for KRAS G12D (c35G>A)(Cat. No. ASE-8036) or wild-type (Cat. No. ASE-8051) were obtained from AccuRef / Applied StemCell (USA) and cultured in McCoy’s 5a medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. PANC-1 (human pancreatic adenocarcinoma) cells (RRID: CVCL_0480) heterozygous for KRAS G12D (c35G>A) were obtained from ATCC, USA and cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

XNAzymes (FR6_1_KRas12B or inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi), DNAzymes (10-23_KRasC [6+7] or [10+10] versions), siRNA (DsiRNA_KRas12 or negative control DsiRNA (Cat. No. 51-01-14-04, IDT, USA)), or buffer alone, were transfected into cells growing at ~60% confluency (detached using 0.25% trypsin EDTA) using a Neon electroporation system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA); 800,000 cells were used per transfection with 10 ul Neon tips and 2 x 20 ms pulses of 1400V.

mRNA quantification by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

Total cell RNA from in vivo experiments, and Sub_KRas_ORF RNA in vitro reactions, was extracted and purified using RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Germany), with on-column DNase digestion according to the manufacturer’s instructions, plus 3 additional column washes using buffer RPE (Cat. No. 1018013, Qiagen, Germany) in order to fully remove FANA oligos. ~1 ug of total cellular RNA was reverse transcribed per 20 ul reaction using iScript RT (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), with random primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1ul of the RT reaction (~50 ng cDNA) was used in a 20ul emulsion PCR for cDNA quantification by Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR), prepared using ddPCR Supermix, Droplet Generation Oil and a QX-200 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), according to the manufacturers instructions. Details of the primer and probe sets used are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Data were analysed using Quantasoft Analysis Pro software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) and Prism 9.2.0 (Graphpad Software, USA). KRAS mRNA levels measured using the KRAS exon 1-2 TaqMan assay were normalized to either the eIF2B2 reference assay or the KRAS exon3-4 set, as appropriate, and in the case of transfection experiments, to data from contemporary cells transfected with buffer alone.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) PCR

5’ RACE PCR was performed using a SMARTer RACE kit (Takara Bio, Japan), with modifications following the method of Picelli et al.6; cDNA was synthesized from 250 ng total RNA per 10 ul RT reaction, purified as described above from RKO cells transfected with 100 pmol / 106 cells XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12B, inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi, DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC[10+10], or buffer alone, using the 12 uM template-switching “TS_oligo” (see Supplementary Table 1) and SMARTScribe Reverse Transcriptase (Takara Bio, Japan). To provide positive control RACE PCR reactions for reference, RT reactions were also performed with 10 ng synthetic KRAS transcript (Sub_KRas_ORF) purified from reactions with or without XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12B (in the absence of RNase H), or inactive FR6_1_KRas12Bi or DNAzyme 10-23_KRasC[10+10] in the presence of human RNase H1 (performed as described in “RNase H assays” above).

cDNA was amplified by a two-step nested PCR strategy using OneTaq Hot Start master mix (NEB, USA). The first ‘out-nested’ PCRs used 0.25 uM forward primer “TS_PCR1” and 0.25 uM reverse primer “KRas_RACE_1”, with 2 ul RT reaction as template per 35 ul PCR. Cycling conditions were 94 °C for 1min, 25 x [94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s], 72 °C for 2 min. Following the first PCR, primers were digested using ExoSAP (Ambion/Life Technologies, USA), which was then heat inactivated, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Second step (‘in-nest’) PCRs used 1 ul of unpurified out-nest PCR product as template in a 50 ul reaction with 0.25 uM forward primer “TS_PCR2” and 0.25 uM reverse primer “KRas_RACE_2”. Cycling conditions were 94 °C for 1min, 15 (transcript reactions) or 25 (total RNA reactions) x [94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s], 72 °C for 2 min. Reactions were analysed by electrophoresis on 4% NGQT-1000 agarose (Thistle Scientific, UK) gels containing GelStar stain (Lonza, Switzerland). Bands were purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany) and cloned using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A selection of colonies were used to start cultures for plasmid miniprep (Qiagen, Germany) and subsequent Sanger sequencing (Source Bioscience, UK).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Steady-state kinetics of FR6_1 XNAzyme-catalysed RNA cleavage under quasi-physiological conditions.

Michaelis-Menten curve determined for the cleavage of Sub_Ebo RNA by the FR6_1 XNAzyme under quasi-physiological conditions (37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Evaluation of RNA substrate cleavage site preferences by the FR6_1 XNAzyme.

(a) Sequence of “FR6_1_NucSR”, a variant of XNAzyme FR6_1 retargeted to cleave RNA substrate “NucSR”(see reference (56)) by changing FANA residues shown in brown. (b) Urea-PAGE gels showing reactions of FR6_1_NucSR (5 uM) with all possible variants of RNA substrate NucSR (1 uM) at positions 8, 9 and 10 (shown in red in (a))(24 h, 17 °C, 10 mM Mg2+).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Engineering the KRAS G12D-targeting XNAzyme to invade long RNA substrates.

(a-c) Urea-PAGE gels showing activity of variants of XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12 (“Fz12”)(1.25 uM) with alternative length substrate-binding arms as indicated, and FR6_1_KRas12B (“Fz12B”)(which has 10 + 10, partially FANA-PS modified binding arms, see Fig. 3), on alternative length RNA substrates (0.25 uM): (a) Sub_KRas12 (30 nt), (b) Sub_KRas12_long (68 nt) and Sub_KRas_ORF (2.1kb), a synthetic transcript comprising the full KRAS ORF and UTRs (1.5 h, 37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+). (d) Urea-PAGE gel showing Fz12B (10 nM) performing multiple turnover catalysis of Sub_KRas12 [G12D] (1 uM) RNA cleavage (37 °C, pH 7.4, 1 mM Mg2+). Substrate secondary structure diagrams were generated using RNAfold (Methods reference 3).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Characterisation of RNase H1-dependent RNA cleavage induced by active and inactive XNAzymes and DNAzymes.

Urea-PAGE gel showing assays of human RNase H1-mediated cleavage of RNA substrate Sub_KRas12_long [G12D], induced by XNAzyme FR6_1_KRas12B (“Fz12B”), catalytically-inactive FR6_1_KRas12B[G27A] (“Fz12Bi”), or DNAzymes 10-23_KRasC [6 + 7] or 10-23_KRasC [10 + 10]. Sequences and putative secondary structures of Fz12B and target RNA show deduced locations of cleavage sites mediated by RNase H (red arrows) or the FANAzyme alone (green arrow). Note that partial alkaline hydrolysis of the RNA substrate (-OH) and XNAzyme-mediated cleavage produce 5’ RNA products that terminate in 3’ cyclic phosphate, whereas RNase H-mediated cleavage produces 3’ OH termini; the resulting difference in PAGE mobility has been taken in account when deducing cleavage sites.

Extended Data Fig. 5. The KRAS Gl2D-targeting XNAzyme performs G12D-specific mRNA knockdown inside PANC-l cells.

Example droplet digital RT-qPCR (ddPCR) multiplex assays (see Supplementary Table 3) of (a) total KRAS mRNA (channel 1, blue) and reference EIF2B2 mRNA (channel 2, green), and (b) KRAS alleles G12D (c.35G>A) mRNA (channel 1, blue) and wild-type (wt) mRNA (channel 2, green), in RKO cells (homozygous for either G12D or wt KRAS) or PANC-1 cells (heterozygous for G12D and wt KRAS). Together, these results show that the baseline level of total KRAS expression in PANC-1 cells was ~3-fold higher than in RKO KRASG12D/G12D, with the G12D allele mRNA transcribed at approximately twice the level of the wild-type KRAS mRNA. (c) Dose response curves showing (bottom graph) total KRAS mRNA levels (relative to reference EIF2B2 mRNA and normalised to cells transfected with buffer alone (yellow circles)) and (top graph) ratio of G12D : wt KRAS mRNA, in PANC-1 cells 3 h after transfection with XNAzyme “FR6_1_KRas12B” (Fz12B)(red circles and dashed line) or the catalytically inactive mutant “FR6_1_KRas12Bi” (Fz12Bi)(black triangles and dashed line) at the concentrations shown. Each datum represents an independent biological replicate and error bars show ddPCR total error. (d) Chart showing proposed interpretation of data from (c); levels of G12D (blue bars) and wt (green bars) KRAS mRNA are equally reduced by RNase H-mediated knockdown (represented as dashed blue and green bars) induced by both the active and inactive XNAzymes (although to a greater degree by the inactive XNAzyme). In the case of the inactive XNAzyme, due to the unequal baseline transcription of G12D and wt KRAS mRNA, this causes an increase in the ratio of G12D : wt KRAS mRNA. With the active XNAzyme - in addition to this effect - allele-specific XNAzyme-mediated knockdown (represented as dashed purple bar) reduces the level of G12D, but not wt KRAS mRNA, maintaining (or reducing) of the baseline ratio of G12D: wt KRAS mRNA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Matthew Watson (Sigma-Aldrich / Merck) for synthesis of FANA oligonucleotides, Dr. Lukas Stadler for assistance with preliminary experiments on delivery of FANA, and members of the Holliger and Taylor groups for discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (A.I.T., C.J.K.W., S.-Y.P.-C., P.H., program no. MC_U105178804), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (INTENSIFY BB/M005623/1 to P.H. and A.I.T.), the AMGEN Scholars programme (C.J.K.W.), the Wellcome Trust (M.D., PhD studentship) and a Wellcome Trust / Royal Society Sir Henry Dale Fellowship to A.I.T. (215453/Z/19/Z).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.I.T. and P.H. conceived the project. A.I.T. designed and conducted experiments and analysed data with C.J.K.W., M.D and S.-Y.P.-C. A.I.T and P.H. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files, except raw sequencing reads, which are available in the NCBI SRA repository, BioProject ID SAMN28955451.

References

- 1.Micura R, Hobartner C. Fundamental studies of functional nucleic acids: aptamers, riboswitches, ribozymes and DNAzymes. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:7331–7353. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00617c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma L, Liu J. Catalytic Nucleic Acids: Biochemistry, Chemical Biology, Biosensors, and Nanotechnology. iScience. 2020;23:100815. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.100815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng H, Latifi B, Muller S, Luptak A, Chen IA. Self-cleaving ribozymes: substrate specificity and synthetic biology applications. RSC Chemical Biology. 2021 doi: 10.1039/d0cb00207k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haseloff J, Gerlach WL. Simple RNA enzymes with new and highly specific endoribonuclease activities. Nature. 1988;334:585–591. doi: 10.1038/334585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santoro SW, Joyce GF. A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4262–4266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulhammer D, Famulok M. Characterization and divalent metal-ion dependence of in vitro selected deoxyribozymes which cleave DNA/RNA chimeric oligonucleotides. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;269:188–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M, Chang D, Li Y. Discovery and Biosensing Applications of Diverse RNA-Cleaving DNAzymes. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:2273–2283. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poje JE, et al. Visual displays that directly interface and provide read-outs of molecular states via molecular graphics processing units. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2014;53:9222–9225. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahan-Hanum M, Douek Y, Adar R, Shapiro E. A library of programmable DNAzymes that operate in a cellular environment. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1535. doi: 10.1038/srep01535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng H, Li XF, Zhang H, Le XC. A microRNA-initiated DNAzyme motor operating in living cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14378. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usman N, Blatt LM. Nuclease-resistant synthetic ribozymes: developing a new class of therapeutics. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;106:1197–1202. doi: 10.1172/JCI11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow PK, et al. An open-label, phase 2 trial of RPI.4610 (angiozyme) in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:4098–4104. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purath U, et al. Efficacy of T-cell transcription factor-specific DNAzymes in murine skin inflammation models. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;137:644–647.:e648. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garn H, Renz H. GATA-3-specific DNAzyme - A novel approach for stratified asthma therapy. European journal of immunology. 2017;47:22–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greulich T, et al. A GATA3-specific DNAzyme attenuates sputum eosinophilia in eosinophilic COPD patients: a feasibility randomized clinical trial. Respir Res. 2018;19:55. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0751-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khachigian LM. Deoxyribozymes as Catalytic Nanotherapeutic Agents. Cancer Res. 2019;79:879–888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi JJ. Resurrecting DNAzymes as Sequence-Specific Therapeutics. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:139fs120. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fokina AA, Stetsenko DA, François J-C. DNA enzymes as potential therapeutics: towards clinical application of 10-23 DNAzymes. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2015;15:689–711. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1025048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fokina AA, Chelobanov BP, Fujii M, Stetsenko DA. Delivery of therapeutic RNA-cleaving oligodeoxyribonucleotides (deoxyribozymes): from cell culture studies to clinical trials. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2017;14:1077–1089. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2017.1266326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J. RNA-Cleaving DNAzymes: Old Catalysts with New Tricks for Intracellular and In Vivo Applications. Catalysts. 2018;8:550. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cieslak M, Szymanski J, Adamiak RW, Cierniewski CS. Structural rearrangements of the 10-23 DNAzyme to beta 3 integrin subunit mRNA induced by cations and their relations to the catalytic activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:47987–47996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Victor J, Steger G, Riesner D. Inability of DNAzymes to cleave RNA in vivo is due to limited Mg2+ concentration in cells. European Biophysics Journal. 2017;113:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00249-017-1270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young DD, Lively MO, Deiters A. Activation and deactivation of DNAzyme and antisense function with light for the photochemical regulation of gene expression in mammalian cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:6183–6193. doi: 10.1021/ja100710j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivory L, et al. The DNAzymes Rs6, Dz13, and DzF have potent biologic effects independent of catalytic activity. Oligonucleotides. 2006;16:297–312. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.16.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodchild A, et al. Cytotoxic G-rich oligodeoxynucleotides: putative protein targets and required sequence motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4562–4572. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dass CR, Choong PF. Sequence-related off-target effect of Dz13 against human tumor cells and safety in adult and fetal mice following systemic administration. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:51–60. doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geyer CR, Sen D. Evidence for the metal-cofactor independence of an RNA phosphodiester-cleaving DNA enzyme. Chemistry & biology. 1997;4:579–593. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carrigan MA, Ricardo A, Ang DN, Benner SA. Quantitative analysis of a RNA-cleaving DNA catalyst obtained via in vitro selection. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11446–11459. doi: 10.1021/bi049898l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasprowicz A, Stokowa-Sołtys K, Jeżowska-Bojczuk M, Wrzesiński J, Ciesiołka J. Characterization of Highly Efficient RNA-Cleaving DNAzymes that Function at Acidic pH with No Divalent Metal-Ion Cofactors. ChemistryOpen. 2017;6:46–56. doi: 10.1002/open.201600141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth A, Breaker RR. An amino acid as a cofactor for a catalytic polynucleotide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:6027–6031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollenstein M, Hipolito CJ, Lam CH, Perrin DM. A self-cleaving DNA enzyme modified with amines, guanidines and imidazoles operates independently of divalent metal cations (M2+) Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:1638–1649. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Liu E, Lam CH, Perrin DM. A densely modified M2+-independent DNAzyme that cleaves RNA efficiently with multiple catalytic turnover. Chemical Science. 2018;9:1813–1821. doi: 10.1039/c7sc04491g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]