Abstract

Although Klinefelter syndrome (KS) is common, it is rarely recognised in childhood, sometimes being identified with speech or developmental delay or incidental antenatal diagnosis. The only regular feature is testicular dysfunction. The postnatal gonadotropin surge (mini-puberty) may be lower but treatment with testosterone needs prospective studies. The onset of puberty is at the normal age and biochemical hypogonadism does not typically occur until late-puberty. Testosterone supplementation can be considered then or earlier for clinical hypogonadism.

The size at birth is normal, but growth acceleration is more rapid in early and mid-childhood with adult height greater than mid-parental height. Extreme tall stature is unusual. The incidence of adolescent gynaecomastia (35.6%) is not increased compared with typically developing boys. It can be reduced or resolved by testosterone supplementation potentially preventing the need for surgery.

Around two-thirds require speech and language therapy or developmental support and instituting therapy early is important. Provision of psychological support may be helpful to ameliorate these experiences and provide opportunities to develop strategies to recognise, process and express feelings and thoughts. KS boys are at increased risk of impairment in social cognition and less accurate in perceptions of social emotional cues.

The concept of likely fertility problems needs introduction alongside the regular reviews of puberty and sexual function in adolescents. Although there is now greater success in harvesting sperm through techniques such as testicular sperm extraction, it is more successful in later adolescence than earlier. In-vitro maturation of germ cells is still experimental.

Introduction

This review presents the contemporary approach to the provision of support for boys and adolescents with Klinefelter syndrome (KS) and their parents from practitioners who have a special interest in their clinical care and research.

Getting the diagnosis

Although KS is common, 47,XXY being present in around one in 600 males, not only it is rarely recognised in childhood and adolescence, the majority are actually never diagnosed. Major congenital abnormalities are unusual. Some boys are identified by antenatal diagnosis, usually unexpectedly, but others may not present until later on account of developmental, speech and language delay, or sometimes unusual behavioural patterns. Much has been written about the effect on speech and development, and growth and puberty variations from follow-up studies of newborn-identified individuals from the 1970s to 1990s which provide an unbiased overview on account of the recruitment by population screening [1–4]. A recent review is available with more specific information [5].

Communicating the diagnosis

On first encounter with the parents it is important to establish a rapport and set out a balanced overview of the condition, ideally using the genetic shortcut ‘XXY’ or the abbreviation ‘KS’ which families prefer. Use of the term ‘variant’ rather than ‘abnormality’ acknowledges that the majority of KS boys and men function pretty normally. Reassurance that their son will not necessarily develop all the features of the syndrome is really valuable. Many parents worry about explaining the diagnosis to the wider network of family, friends, nursery and school, as most people have never heard of KS. Discussions of KS outwith the immediate family are not usually necessary or helpful, unless it is relevant for medical or educational purposes. Most KS boys grow up happily within the family environment and do not look or behave differently. Guiding the parents that their son should be incorporated into the family routines, doing normal things on a day to day basis without constant referring to KS is important, and as potentially socially vulnerable individuals, encouragement, love, care and individual attention from a supportive family are the most important elements of their upbringing.

Infancy and early childhood

Growth

The size at birth of KS boys is not different from the population, but growth acceleration is more rapid in early and mid-childhood resulting in upward height centile shifts and by mid-childhood, many boys end up on a centile greater than their mid-parental height [1]. Extreme tall stature is unusual and if not present by school entry, then it is not going to be an issue, thus parents can be reassured. Boys with other X aneuploidy variants of KS (48,XXXY 48,XXYY) may grow even taller, but this may depend on the presence of other congenital skeletal variations. 49,XXXXY and its variants may also be associated with reduced height [6].

Testicular function

The hypogonadism in KS may start as early as fetal life or infancy due to the higher prevalence of underdeveloped genitalia and cryptorchidism, reduced germ cell number in testicular biopsies, smaller testicular size, and studies have suggested a blunted testosterone surge during mini-puberty, the rise in gonadotropins over the first 2-3 months of infancy [7, 8]. However, due to the lack of general understanding about mini-puberty in infants, it is unclear if any hypogonadism in KS boys has management implications. Studies in this area are few. Davis et al reported improved body composition in infants randomly assigned to early testosterone treatment [9]. Another study reported higher scores on standardized developmental assessments in multiple cognitive domains at 3 and 6 years of age in boys who received a course of testosterone to treat a micropenis [10]. However, this retrospective study lacked blinding and randomization thereby limiting the generalizability of these findings. The reports of cognitive and behavioural benefits in males with KS treated with testosterone need to be replicated with prospective studies. Hence, the current evidence is insufficient to support the routine use of testosterone during infancy in KS [11]. Referral to a paediatric endocrinologist should be considered if micropenis is present. British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes guidelines recommend three injections of testosterone 25mg - 0.1ml at monthly intervals, or topical 1-2% testosterone cream as the usual treatment choices [12]. If cryptorchidism or inguinal hernia is noted, the infant should be referred to paediatric urology.

Speech and developmental delay

Around two-thirds of KS boys will require speech and language therapy or developmental support, but it is important to be aware of their needs and institute therapy as early as possible [1–5]. For those boys who require help, the amount of input required is entirely dependent on the level of need, and is of the same extent as would be required for chromosomally typical children, and thus no treatment approaches are unique to KS boys. This is important to stress as some therapists may cite inexperience and a lack of knowledge about specific treatments for KS.

Mid-childhood

Hypogonadism

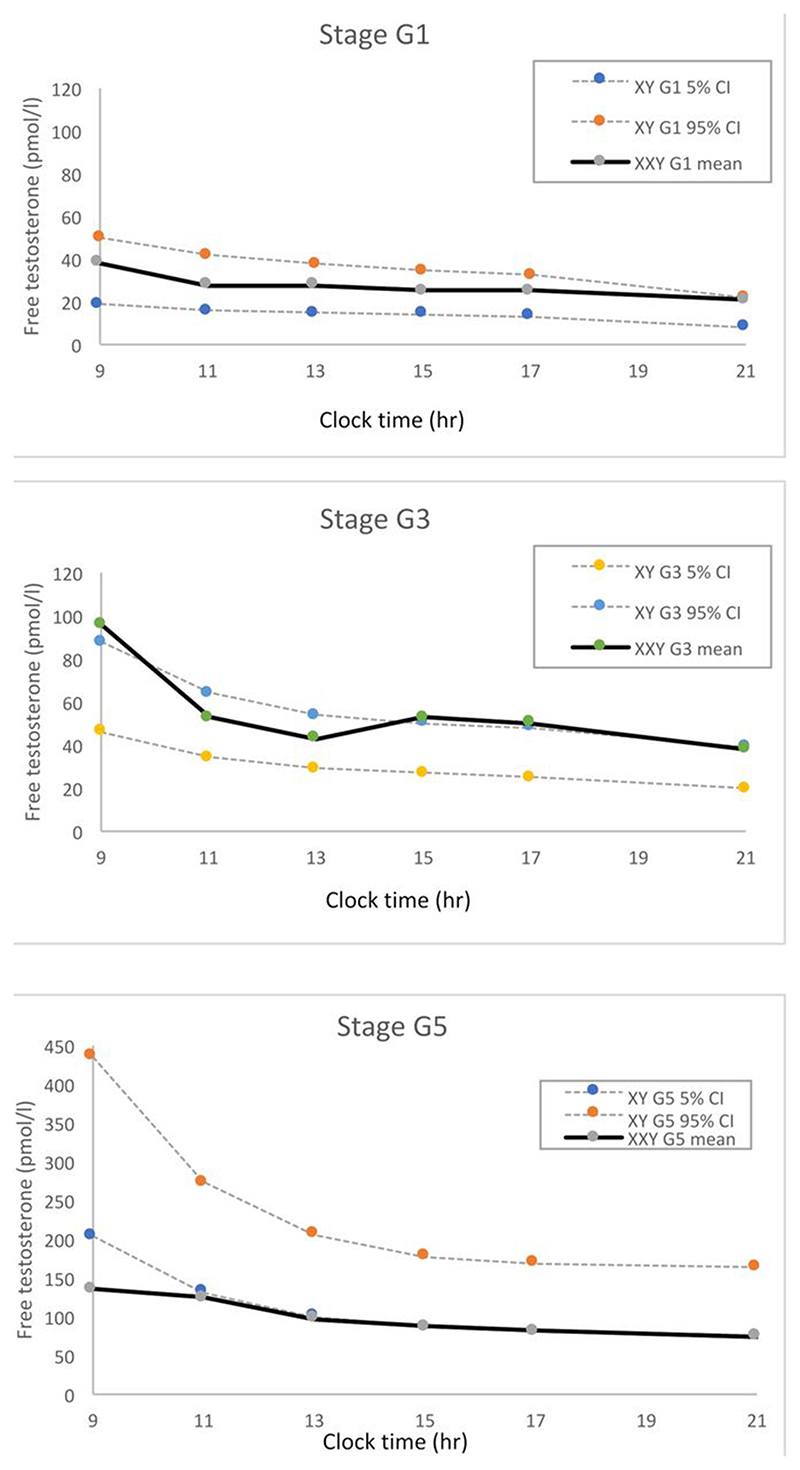

Studies of gonadal function in mid-childhood have not shown any abnormality so there is no clear rationale for testosterone supplementation then (Figure) [1,13–16].

Figure.

Diurnal variation profiles 09.00-21.00h of free testosterone concentrations, measured in saliva. Unpublished data from 10 XXY boys (52 diurnal profiles) and 13 XY boys at Tanner stage G1, 6 XXY boys (10 diurnal profiles) and 25 XY boys at Tanner stage G3, and 11 XXY boys (20 diurnal profiles) and 13 XY boys at Tanner stage G5. XXY and XY boys were recruited by newborn population screening [1] and the mean testosterone concentrations in the XXY boys are compared with the 95% confidence intervals (CI) from XY controls by pubertal stage based on data from [40]. The plasma testosterone equivalent is approximately 10 times higher (regression equation for conversion: salivary free testosterone (pmol/l) = 9.8 plasma testosterone (nmol/l) + 34.5 [40]).

Education and behaviour

Most KS boys do not fall into the category of requiring significant educational support, but the subtleties of specific learning defects, particularly in receptive and expressive language, may cause frustration and the inability of a boy to explain himself clearly and as quickly as others may lead to temper tantrums and anger outbursts. Clear parenting guidelines and professional support are valuable at this age. Social skills often take longer to develop, with boys feeling isolated, preferring their own company. Family guidance and encouragement is key here. Those with more severe difficulties and associated comorbidities will benefit from multidisciplinary community paediatric services and CAMHS input.

Adolescence

Hypogonadism

The principal concerns in the second decade are around the treatment of hypogonadism, if present, with testosterone, and the assessment of fertility prospects and possibly its preservation.

The clinical onset of puberty is not delayed in KS boys, a frequent misunderstanding. Early testicular enlargement occurs at the same age and to the same initial extent as typical boys. Although the gonadotropins FSH and LH rise at the start of puberty, testosterone is usually within the pubertal stage-related range (Figure) [1,5,13–16].

Hypogonadism can be defined biochemically or clinically (Table 1). Biochemical hypogonadism (Table 2) does not typically occur until late puberty, at around age 14 years and Tanner stage 5 [1]. Here the usual accelerated nocturnal rise in testosterone is blunted (Figure). Thus assessment of hypogonadism can only be made accurately by measuring the testosterone concentration in the morning (8 am to 9 am) when it is at its highest on account of the significant diurnal variation in late puberty (Figure). Afternoon blood samples are not useful diagnostically.

Table 1. Classification of hypogonadism in Klinefelter syndrome.

Biochemical hypogonadism

|

Clinical hypogonadism

|

Table 2. Assessment of hypogonadism at each time point.

| Infancy |

| 4-8 weeks |

| Testosterone, FSH, LH |

| Mid-puberty (age 13 yr +) |

| 8 am Testosterone, FSH, LH |

| Late puberty (age 15 yr +) |

| 8 am Testosterone, FSH, LH, inhibin |

| On testosterone gel |

| 4-6 hr after application |

| Testosterone, FBC, FSH, LH |

| Sustanon/testosterone enantate injections |

| Pre-injection (trough) level |

| Testosterone, FSH, LH, FBC, LFT |

| Testosterone undecanoate (Nebido) injections |

| Peak level 4 weeks after injection AND pre-injection (trough) level |

| Testosterone, FSH, LH, FBC, LFT |

Clinical hypogonadism (Table 1) is also a reason to consider testosterone supplementation in KS boys as typical full virilisation may not occur. One manifestation and reason for intervention include increasing adiposity, the occurrence of a central deposition of fat particularly on the hips and abdomen, often described as a ‘beer-belly’ [1]. Low muscle tone and reduced power may be subjectively improved by testosterone substitution. It can be difficult to determine whether symptoms of lethargy and a lack of motivation are due to testosterone insufficiency, or just part of the syndrome. In such cases a trial of testosterone supplementation can be considered.

Gynaecomastia

From a review by Butler of all 191 published cases, the incidence of gynaecomastia in KS boys (35.6%) is not increased compared with typically developing boys and enlarges to the same extent, but its persistence into adulthood may result from the absence of the late pubertal rise of testosterone and the consequent hypogonadism [17]. Consequently, testosterone supplementation in a physiological incremental approach starting with transdermal gel 10-20mg each morning has been shown to reduce or resolve the development of gynaecomastia potentially preventing the need for surgical intervention later on [17]. It is most effective when treatment is started at the first appearance of breast tissue enlargement.

Growth spurt

The magnitude of the adolescent growth spurt in height is the same in KS boys as in typically growing boys [1,15]. Thus it is possible to predict with confidence that the adult height of a boy whose height is within the normal centile range at the start of puberty will not become excessive. Those with tall parents and whose heights are above three standard deviations in late childhood, if concerned about extreme tall stature, may benefit from rapidly escalating doses of intramuscular testosterone (Sustanon® or testosterone enantate) once the clinical onset of puberty is documented, monitoring height and bone age [3].

Psychological support

The constellation of the developmental variations of KS can have implications for clinical care. Language problems can disrupt understanding of content, meaning, and may impact on outcomes of clinical discussions. Confusion can lead to misunderstandings of information, increased anxiety and non-compliance with treatment. Provision of psychological support is important as part of a multi-disciplinary approach to promoting lifespan health, wellbeing and, importantly, supporting endocrine and fertility discussions. KS males are reported to be increased risk to impairments in social cognition and less accurate in perceptions of social emotional cues, whilst simultaneously experiencing increased emotional arousal in parallel with decreased ability to identify and verbalise their emotions [18,19]. This array of difficulties may affect managing, coping with, and verbalising feelings and concerns, with a potential to be exacerbated by receptive and expressive language problems.

These features, often in parallel with literal interpretation of language and problems with social communication may impede understanding and be a barrier to externalising and discussion with family and partners. This can, in turn, contribute to feelings of panic and misunderstandings during interactions, with significant impact on relationships and can extend to clinical encounters.

Provision of psychological support may be helpful to ameliorate these experiences and provide opportunities to develop strategies to recognise, process and express feelings and thoughts [20]. This may aid understanding, beneficial in reducing stress, anxiety and promote understanding of clinical discussions, treatment and informed decision making.

Gender incongruence

The incidence of gender incongruence and gender dysphoria is not increased in KS males [21].

Education

KS can have a significant impact on cognitive, social and emotional development and wellbeing. The generalised breadth and range of subjects in the curriculum up to and including GCSE years may be particularly challenging and social communication problems may cause upset and difficulties ‘joining in’ with peers.

Short-term working auditory memory and auditory processing difficulties have been reported in KS and may impact significantly on accessing the curriculum, particularly with traditional forms of teaching such as speaking, listening and writing where more time to process and record information may be required [18]. Written support from paediatricians and psychologists can be valuable at this point, providing anticipatory and advisory guidance including provision of one-to-one support, small group settings and extra time in exams. Additional guidance for educators to aid learning and memory can be valuable: provision of tailored materials such as visuals, bullet points, shorter sentences and practical experiences.

Post 16 education and higher education may provide opportunities to study fewer, specialised, subjects creating perhaps increased opportunities to demonstrate niche abilities during these later educational years. In these settings, psychological and educational guidance for provision of reasonable adjustments, accessing appropriate assistances such as Disabled Students Allowance and careers guidance is very valuable to aid positive transitions between school, college and beyond into employment, protecting self-esteem and building confidence. A choice of practical, non-academic careers can alleviate the pressure of standard learning processes. Similarly, written support and guidance for employers may be helpful in some workplace settings.

Fertility

Previous studies of the infant and young testis have shown normal architecture and the presence of germ cells, although there appears to be a reduction in their number [22]. When puberty commences most of the developing tubules are Sertoli cell only and in response presumably to the high gonadotropins, a disordered testicular architecture develops with hyalinisation of the seminiferous tubules. It is possible to see a significant degree of initial testicular growth, in some KS boys up to 12 ml, but subsequent involution and reduction in size occurs, usually measuring 3-5ml in older adolescents and adults. On account of the normal pubertal prostatic development, ejaculation occurs but the semen is azoospermic in over 90% [23]. For those adolescents who are sexually active, contraception should still be advised.

It is wise to introduce the concept of likely fertility problems during the teenage years alongside the need for regular reviews of puberty and sexual function [24]. Although there is now much greater success in sperm harvesting through newer techniques such as testicular sperm extraction (TESE) or microscopic testicular sperm extraction (mTESE), the optimal timing of this process is unclear. The largest meta-analysis of sperm retrieval in KS patients suggested a success rate of 44%, with age, testosterone, FSH and testicular volume having no significant relationship with outcome [25]. This contrasts with the initial studies which indicated that success was less likely in men aged over 35 years and that started an interest in attempting sperm retrieval in younger patients [26]. However, there is increasing evidence that fertility preservation should not be offered to adolescents younger than 16 years because of lower retrieval rates for germ cells by mTESE compared with those for adolescents and adults between 16 and 30 years [26,27].

Many young adult males with KS are emotionally less mature than their counterparts and the concept of fertility estimation and the emotional consequences of knowing they are going to be infertile needs very careful counselling and preparation. The balance of carrying out a surgical sperm retrieval at the right time must be measured against the potential psychological distress caused if no sperm is found. The counselling process is important as some KS males may have a reduced capacity to understand complex explanations. Points for discussion are best presented in a simple structured way backed up by a written version. Once a young adult with KS is mature enough to make this decision, mTESE can be considered if azoospermia on serial semen analysis is demonstrated.

Future experimental considerations

By mid-puberty most of the testicular damage has already occurred and germ cells are reduced or totally absent [28]. This is believed to be due to a massive loss of spermatogonial stem cells in the early pubertal period. However, the lack of longitudinal data make it impossible to determine the trajectory of germ cell loss in individual patients. Whilst cryopreservation of prepubertal testicular tissue to preserve spermatogonial stem cells is becoming more common (e.g. those facing cancer treatment), this is not a straightforward option for boys with KS [29]. This is due to the uncertainties whether germ cells are present within the tissue and their potential to undergo spermatogenesis. Whilst they may be present in tissues obtained from prepubertal patients, the majority of these germ cells are likely to be aneuploid (XXY) and unlikely to be viable for subsequent use in transplantation or in-vitro spermatogenesis. In addition, the potential for XX or XY spermatogonia to spontaneously lose the extra X chromosome resulting in focal spermatogenesis at puberty is unknown and removing testicular tissue in prepuberty may negatively impact on this [30]. As a result, current guidelines produced by European Academy of Andrology recommend against performing a testicular biopsy in prepuberty, instead focusing on maximising the potential for obtaining viable sperm by performing mTESE in young adulthood [24]. This situation may change in the future should effective methods for in-vitro spermatogenesis be developed that could be applied to germ cells obtained from KS patients. At the time of writing, there is only experimental evidence in mouse models of chromosome loss [31].

Into adult life

We know from population mortality and morbidity studies that there is no significant lowering of life expectancy in KS males, however higher risk areas include osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and breast cancer [32,33]. Lifelong follow-up is important not only from the endocrine and metabolic perspective but also for emotional, psychological and fertility support. Only recently have specialist services for KS adults been established, such as our UCLH KF-Xtra clinic, a multi-disciplinary team transitioning KS boys seamlessly from childhood and adolescence to adult services to provide lifelong care. This approach can produce benefits both for quality of life, physical well-being and also research.

Testosterone treatment and metabolic care

Testosterone therapy is the mainstay of treatment for KS men with benefits including reduced fat mass, improved muscle strength, bone density, libido and mood [34,35]. Current formulations of testosterone include testosterone gels (topical daily application), weekly to monthly mixed testosterone esters given either by subcutaneous or intramuscular injections and three monthly testosterone undecanoate (Table 3). No data exist to guide optimal formulation and dosing in KS adults. Testosterone gels, in metered pumps, allow self-administration, easy dose titration, minimising fluctuation in testosterone levels and can be a helpful when introducing therapy. Intramuscular treatment requires administration by healthcare staff so patients often find the long-acting formulation convenient, and can be useful where compliance is an issue. Three-four weekly injections lead to greater fluctuations in testosterone levels which can be problematic, in particular on mood variation and energy. More frequent, lower dose self-administered subcutaneous injections can be considered as well [36]. Monitoring of therapy includes an assessment of the testosterone concentration, full blood count, haematocrit and prostate specific antigen (PSA) in relevant subjects. Polycythaemia is the most frequent side-effect encountered, particularly with long-acting testosterone [35].

Table 3. Types and dosages of testosterone suitable at each age.

| Intramuscular or subcutaneous |

| Infancy or toddler (for micropenis) Sustanon® or testosterone enantate 25mg (0.1ml) for 3 injections at monthly intervals. Course can be repeated if required |

| Puberty Sustanon® or testosterone enantate 50mg (0.2ml) IM/SC once clinical signs of puberty evident, escalation at 6-12 monthly intervals to full dose 250mg 3-4 weekly |

| Post puberty Sustanon® or testosterone enantate 250mg 3-4 weekly IM or 100mg every 7-10 days SC Testosterone undecanoate (Nebido®) 1000mg IM 10-14 weekly |

| Transdermal |

| Puberty Testosterone 2% gel (Tostran®) 10mg daily once clinical signs of puberty evident. May be more effective if administered in morning if gynaecomastia present. Dose escalation at 6-12 monthly intervals to full dose (product dependent) |

| Post puberty Adult dose (Tostran® 60mg, Testavan® 69mg, Testogel® 40mg) titrated to clinical effect and to achieve 4-6 hour post administration plasma testosterone concentration in mid-upper male range |

KS is associated with an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidaemia and an approximate doubling of risk for cardiovascular disease [37]. Whilst the exact mechanisms responsible remain to be elucidated, data regarding a modifying influence of testosterone therapy are conflicted in hypogonadal men [35,38]. Education regarding healthy lifestyle choices, careful surveillance and appropriate interventions to actively manage cardiovascular risk therefore remains essential.

Conclusions

The approach to supporting KS boys and adolescents is age dependent, and needs multi-agency input. Provision of an accurate picture of the condition in contrast with internet search findings is important for reassurance. The report in this journal of the outcome of the KS boys identified in the Edinburgh newborn population screening study presents a balanced perspective on the range of functioning and lifestyles of KS adults, and this can help guide parents when KS is diagnosed [39]. Although the information in this review may benefit those in whom KS is already recognised, how do we address the issue of the 75% of KS males who remain unidentified? Discussions around population genetic screening and prospective identification continue, but this has many ethical and financial considerations.

References

- 1.Ratcliffe SG, Butler GE, Jones M. Edinburgh study of growth and development of children with sex chromosome abnormalities IV. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1990;26(4):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Sex Chromosome Abnormalities Found Among 34,910 Newborn Children: Results From a 13-year Incidence Study in Arhus, Denmark. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1990;26(4):209–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart DA, Bailey JD, Netley CT, Park E. Growth, development and behavioural outcome from mid-adolescence to adulthood in subjects with chromosome aneuploidy: the Toronto study. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1990;26(4):131–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson A, Bender B, Linden MG, Salbenblatt JS. Sex chromosome aneuploidy: the Denver study. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1990;26(4):59–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis S, Howell S, Wilson R, et al. Advances in the Interdisciplinary Care of Children with Klinefelter Syndrome. Adv Pediatr. 2016;63(1):15–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottesen AM, Aksglaede L, Garn I, et al. Increased Number of Sex Chromosomes Affects Height in a Nonlinear Fashion: A Study of 305 Patients With Sex Chromosome Aneuploidy. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 May;152A(5):1206–1212. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JL, Samango-Sprouse C, Lahlou N, et al. Early androgen deficiency in infants and young boys with 47,XXY Klinefelter syndrome. Horm Res. 2005;64(1):39–45. doi: 10.1159/000087313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aksglaede L, Davis SM, Ross JL, Juul A. Minipuberty in Klinefelter syndrome: Current status and future directions. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184(2):320–326. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis SM, Reynolds RM, Dabelea DM, et al. Testosterone Treatment in Infants With 47,XXY: Effects on Body Composition. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(12):2276–2285. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samango-Sprouse C, Stapleton EJ, Lawson P, et al. Positive effects of early androgen therapy on the behavioral phenotype of boys with 47,XXY. American journal of medical genetics Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2015;169(2):150–157. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flannigan R, Patel P, Paduch DA. Klinefelter Syndrome. The Effects of Early Androgen Therapy on Competence and Behavioral Phenotype. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6(4):595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. https://www.bsped.org.uk/media/1987/revised-bsped-testosterone-guideline-v3.pdf .

- 13.Salbenblatt JA, Bender BG, Puck MH, Robinson A, Faiman C, Winter JS. Pituitary-gonadal function in Klinefelter syndrome before and during puberty. Pediatr Res. 1985;19(1):82–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198501000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topper E, Dickerman Z, Prager-Lewin R, et al. Puberty in 24 patients with Klinefelter syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 1982;139(1):8–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00442070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aksglaede L, Skakkebaek NE, Almstrup K, Juul A. Clinical and biological parameters in 166 boys, adolescents and adults with nonmosaic Klinefelter syndrome: a Copenhagen experience. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(6):793–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis SM, Rogol AD, Ross JL. Testis Development and Fertility Potential in Boys with Klinefelter Syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015;44(4):843–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler G. Incidence of gynaecomastia in Klinefelter syndrome adolescents and outcome of testosterone treatment. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(10):3201–3207. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rijn S, Swaab H, Aleman A, Kahn RS. X Chromosomal effects on social cognitive processing and emotion regulation: A study with Klinefelter men (47,XXY) Schizophr Res. 2006 Jun;84(2-3):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rijn S, Swaab H. Emotion regulation in adults with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY): Neurocognitive underpinnings and associations with mental health problems. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(1):228–238. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Rijn S, de Sonneville L, Swaab H. The nature of social cognitive deficits in children and adults with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) Genes Brain Behav. 2018;17(6):e12465. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreukels BPC, Köhler B, Nordenström A dsd-LIFE group. Gender Dysphoria and Gender Change in Disorders of Sex Development/Intersex Conditions: Results From the dsd-LIFE. Study J Sex Med. 2018;15(5):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Saen D, Vloeberghs V, Gies I, et al. When does germ cell loss and fibrosis occur in patients with Klinefelter syndrome? Hum Reprod. 2018;33(6):1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deebel NA, Bradshaw AW, Sadri-Ardekani H. Infertility considerations in klinefelter syndrome: From origin to management. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Dec;34(6):101480. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2020.101480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zitzmann M, Aksglaede L, Corona G, et al. European academy of andrology guidelines on Klinefelter Syndrome Endorsing Organization: European Society of Endocrinology. Andrology. 2021;9(1):145–167. doi: 10.1111/andr.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corona G, Pizzocaro A, Lanfranco F, et al. Sperm recovery and ICSI outcomes in Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(3):265–275. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramasamy R, Fisher ES, Ricci JA, et al. Duration of microdissection testicular sperm extraction procedures: relationship to sperm retrieval success. J Urol. 2011;185(4):1394–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franik S, Hoeijmakers Y, D'Hauwers K, et al. Klinefelter syndrome and fertility: sperm preservation should not be offered to children with Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(9):1952–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deebel NA, Galdon G, Zarandi NP, et al. Age-related presence of spermatogonia in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26(1):58–7. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goossens E, Jahnukainen K, Mitchell RT, et al. Fertility preservation in boys: recent developments and new insights. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(3):hoaa016. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oates RD. The natural history of endocrine function and spermatogenesis in Klinefelter syndrome: what the data show. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(2):266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galdon G, Deebel NA, Zarandi NP, Pettenati MJ, Kogan S, Wang C, Swerdloff RS, Atala A, Lue Y, Sadri-Ardekani H. In Vitro Propagation of XXY Undifferentiated Mouse Spermatogonia: Model for Fertility Preservation in Klinefelter Syndrome Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Dec 24;23(1):173. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow AJ, Higgin CD, Schomaker MJ, et al. Mortality in patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome in Britain: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6516–6522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebæk NH, Gravholt CH. Morbidity in Klinefelter Syndrome: A Danish Register Study Based on Hospital Discharge Diagnoses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1254–1260. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, Cunningham G, Dobs A, et al. Long-term testosterone gel (AndroGel) treatment maintains beneficial effects on sexual function and mood, lean and fat mass, and bone mineral density in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(5):2085–98. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Balsells MM, Murad MH, Lane M, et al. Adverse Effects of Testosterone Therapy in Adult Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2560–75. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Figueiredo MG, Gagliano-Jucá T, Basaria S. Testosterone Therapy With Subcutaneous Injections: A Safe, Practical, and Reasonable Option. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Feb 17;107(3):614–626. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang-Feng M, Hong-Li X, Xue-Yan W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetes in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a longitudinal observational study. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones DB, Billet JS, Price WH, et al. The effect of testosterone replacement on plasma lipids and apolipoproteins. Eur J Clin Invest. 1989;19(5):438–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1989.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ratcliffe S. Long-term outcome in children of sex chromosome abnormalities. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80(2):192–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler GE, Walker RF, Walker RV, Teague P, Riad-Fahmy D, Ratcliffe SG. Salivary testosterone levels and the progress of puberty in the normal boy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1989 May;30(5):587–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1989.tb01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]