Abstract

The hippocampus hosts the continuous addition of new neurons throughout life—a phenomenon named adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN). Here we revisit the occurrence of AHN in more than 110 mammalian species, including humans, and discuss the further validation of these data by single-cell RNAseq and other alternative techniques. In this regard, our recent studies have addressed the long-standing controversy in the field, namely whether cells positive for AHN markers are present in the adult human dentate gyrus (DG). Here we review how we developed a tightly controlled methodology, based on the use of high-quality brain samples (characterized by short postmortem delays and ≤ 24h of fixation in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde), to address human AHN. We review that the detection of AHN markers in samples fixed for 24 h required mild antigen retrieval and chemical elimination of autofluorescence. However, these steps were not necessary for samples subjected to shorter fixation periods. Moreover, the detection of labile epitopes (such as Nestin) in the human hippocampus required the use of mild detergents. The application of this strictly controlled methodology allowed reconstruction of the entire AHN process, thus revealing the presence of neural stem cells, proliferative progenitors, neuroblasts, and immature neurons at distinct stages of differentiation in the human DG. The data reviewed here demonstrate that methodology is of utmost importance when studying AHN by means of distinct techniques across the phylogenetic scale. In this regard, we summarize the major findings made by our group that emphasize that overlooking fundamental technical principles might have consequences for any given research field.

Keywords: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis, human, immunohistochemistry, antigen retrieval, autofluorescence

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) encompasses the functional integration of new dentate granule cells (DGCs) into the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit throughout life (Zhao et al., 2006). The continuous addition of new neurons confers the adult brain with an extraordinary reserve of plasticity. Indeed, AHN participates in hippocampal-dependent learning (Sahay et al., 2011; Shors et al., 2001) and mood regulation (Hill et al., 2015), and it has been proposed to play a role in memory loss (Akers et al., 2014). The occurrence of AHN is widespread among the > 120 mammalian species in which it has been assessed (see Table 1 for a complete list), including rodents (Altman, 1963), shrews (Gould et al., 1997), sheep (Brus et al., 2013), bats (Chawana et al., 2014; Chawana et al., 2016; Chawana et al., 2020; Gatome et al., 2010), elephants (Patzke et al., 2014), non-human primates (Franjic et al., 2022; Gould et al., 1999; Hao et al., 2022; Kohler et al., 2011), and humans (Boldrini et al., 2018; Eriksson et al., 1998; Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Knoth et al., 2010; Manganas et al., 2007; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Spalding et al., 2013; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). There may be a few exceptions: two studies did not find evidence of AHN in northern minke whales or in harbor porpoises (Patzke et al., 2015), nor in a small number of echolocating microbats captured from the wild (Amrein et al., 2007). However, these results lack further replication to date. Although AHN has been extensively characterized in rodents, technical and ethical aspects may have limited the pace of discoveries in the human AHN field. In this regard, although a few studies failed to detect markers of neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus (Dennis et al., 2016; Franjic et al., 2022; Sorrells et al., 2018), most literature available supports the occurrence of AHN in our species (Boldrini et al., 2018; Eriksson et al., 1998; Knoth et al., 2010; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Spalding et al., 2013; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021; Tobin et al., 2019; W. Wang et al., 2022) (see Table 2 for an extended list). This review addresses the potential overlooking of technical considerations that, in our view, lie behind most controversial aspects and ambiguities related to AHN studies in humans (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021).

Table 1.

List of studies addressing the occurrence of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) in distinct mammalian species. Thymidine- H3: Tritiated thymidine. Aβ: Amyloid-β. AHN: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis. BrdU: 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine. CB: Calbindin. CA3: Cornu Ammonis 3. CNP: 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. CR: Calretinin. DCX: Doublecortin. DG: Dentate gyrus. DGC: Dentate granule cell. ETNPPL: Ethanolamine-phosphate phospholyase. GCL: Granule cell layer. GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein. HMGB2: High-mobility group protein B2. IPC: Intermediate Progenitor Cell. MCM2: Minichromosome Maintenance Complex Component 2. ML: Molecular layer. n-3 PUFAS: n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. NeuN: Neuronal nuclear antigen. NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate. NOS: Nitric oxide synthase. NSC: Neural stem cell. NSE: Neuron-specific enolase. PCNA: Proliferating cell nuclear antigen. PH3: Phospho-Histone H3. PSA-NCAM: Polysialylated-neuronal cell adhesion molecule. RGL: Radial glia-like. RNA: Ribonucleic acid. RNR: Ribonucleotide reductase. S100β: S100 calcium-binding protein β. SGZ: Subgranular zone. Sc-RNA seq: Single-cell RNA sequencing. Sn-RNA seq: single-nucleus RNA sequencing. Sox2: SRY-Box transcription factor 2. TOAD: Turned On After Division. TUC-4: Turned On After Division/Ulip/ CRMP-4. TuJ1: Neuron-specific class III β-tubulin. This table was constructed after performing a manual search of studies that included the following terms (and their combination thereof) in the PubMed database: “Adult hippocampal neurogenesis”, “mammal”, “wild mammals”, “cetacean”, “non-human primate”, “old world primate”, “new-world primate”, “non-placental mammal”, “marsupialia”, “carnivore”, “herbivore”, “primate”, “chiroptera”, “artiodactyla”, “domestic animal”, “eulipotyphla”, “afrosoricida”, “scandentia”, “macroscelidae”, “hyracoidea”, “rodentia”, “rodents”, “didelmorphia”, “pig”, “sheep”, “bat”, “fox”, “mole”, “shrew”, “rabbit”, “wild rodent”, “vole”, “marine mammal”, “prosimian”, “sirenia”, “elephant”, “swine”, “canis”, “bovine”, “ovine”, “felis”, “dolphin”, “whale”, and “seal”. Studies not focused on the hippocampal region or that examined only human subjects were manually excluded.

| INFRACLASS | ORDER | SPECIES | REFERENCE | CONCLUSIONS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marsupialia | Dasyuromorphia | Fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) | (Harman, Meyer, & Ahmat, 2003) | The occurrence of AHN was demonstrated using thymidine-H3. Stress and age reduced the number of newly generated DGCs. | |

| Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) | (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. | |||

| Placental mammals | Eulipotyphla | Hedgehog (Erinaceus concolor) | (Bartkowska et al., 2010) | Presence of DCX+ and Ki-67+ cells in the SGZ and GCL. No colocalization between DCX and glial markers such as vimentin or GFAP. | |

| Mole (Talpa europaea) | |||||

| African giant rat (Cricentomys gambianus) | (Olude, Olopade, & Ihunwo, 2014) | Presence of DCX+ and Ki-67+ cells in the DG. Adults presented lower cell numbers than juveniles. | |||

| (Lavenex, Steele, & Jacobs, 2000) | BrdU incorporation in the DG. No seasonal differences in cell proliferation rate or in total neuron number were observed. | ||||

| Yellow-pine chipmunks (Neotamias amoenus) | (Barker, Wojtowicz, & Boonstra, 2005) | Gray squirrels showed three times the density of Ki-67+ proliferating cells in the DG than chipmunks, which have simple food storage strategies. Both species showed similar density of immature DCX+ neurons. The number of Ki-67+ proliferative cells in gray squirrels and the density of DCX+ immature neurons in chipmunks decreased with age. | |||

| Red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) Cape mole-rats (Georychus capensis) | |||||

| (Wan, Tu, Zhang, Jiang, & Yan, 2019) | BrdU+ cells positive for Ki67, Sp8, and DCX in the adult SGZ. These cell populations peaked at the late gestational stages in comparison to non-pregnant females. | ||||

| (Ormerod & Galea, 2001) | Incorporation of thymidine-H3 and BrdU in the DG. Higher density of proliferative cells in the GCL and the hilus in reproductively inactive females compared to active females. This density correlated negatively with serum estradiol levels. Higher rates of cell survival in the GCL and the hilus in reproductively active females. | ||||

| Prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) | (Fowler, Liu, Ouimet, & Wang, 2002) | BrdU incorporation in the DG of females. | |||

| Yellow necked wood mouse (Apodemus flavicollis) Long-tailed wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) | (Amrein, Slomianka, Poletaeva, Bologova, & Lipp, 2004) | AHN was demonstrated in the 4 species, which showed distinct onset of age-driven decrease in AHN. | |||

| Bank vole (Myodes glareolus) | |||||

| Pine vole (Microtus duodecimcostatus) | |||||

| Ultrastructural identification of thymidine-H3-labeled mitotic neuronal precursors in the GCL of rats and mice. | |||||

| (Altman, 1963) | Identification of a proliferative region in the adult rat DG. | ||||

| (Zhu et al., 2003) | Morphological characterization of RNR+ proliferative cells, which do not express markers of differentiated neurons or glial cells, except a fraction that co-expressed GFAP. Colocalization between BrdU and RNR in proliferative cells. | ||||

| (Dawirs, Teuchert-Noodt, Hildebrandt, & Fei, 2000) | Presence of BrdU+ proliferative cells in the DG throughout adult life and aging, despite a decline during juvenile life. | ||||

| (Dawirs, Hildebrandt, & Teuchert-Noodt, 1998) | BrdU incorporation. Haloperidol increased DGC proliferation. | ||||

| Namaqua rock mouse (Micaelamys namaquensis) | (Cavegn et al., 2013) | The numbers of Ki-67+ and DCX+ cells are similar for all the species with a habitat in southern Africa. Lower proliferation but higher neuronal differentiation in rodents from the southern African habitat compared to those from European environments. | |||

| Red veld rat (Aethomys chrysophilus) | |||||

| Highveld gerbil (Tatera brantsii) | |||||

| Spiny mouse (Acomys spinosissimus) Pygmy fieldmice (Apodemus microps) | |||||

| Long-tailed wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) | (Hauser, Klaus, Lipp, & Amrein, 2009) | No effect of voluntary running and environmental changes on the number of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons. | |||

| Stella wood mouse (Hylomyscus stella) Rwenzori striped mouse (Hybomys lunaris) Emin’s pouched rat (Cricetomys emini) | (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of KI-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. | |||

| Beecroft’s flying squirrel (Anomalurus beecrofti) | |||||

| Target rat (Stochomys longicaudatus) | |||||

| Yellow-spotted brush-furred rat (Lophuromys flavopunctatus) | |||||

| Natal mjultimammate rat (Mastomys natalesis) | |||||

| Lesser egyptian jerboa (Jaculus jaculus) | |||||

| Arabian spinny mouse (Acomys dimidiatus) Cairo spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus) Wagner’s gerbil (Gerbillys dasyurus) King jird (Meriones libycus) | |||||

| Libyan jird (Meriones libycus) | |||||

| Asian garden dormouse (Eliomys melanurus) Cape ground squirrel (Xerus inauris) | |||||

| Carnivora | |||||

| Feliform banded mongoose (Mungos mungo) | (Pillay et al., 2021) | DCX+ neurons located at the inner border of the GCL and within the SGZ in both species. DCX+ neurons exhibited apical dendrites that traversed the GCL to enter the ML. | |||

| Asian small-clawded otter (Aonyx cinerea) Harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus) | (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of DCX+ cells with processes that extend into the ML and GCL. | |||

| Nothern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) | |||||

| Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) | |||||

| Chiroptera | Pallas’s long-tongued bat (Glossophaga soricina) Seba’s short-tailed bat (Carollia perspicillata) | ||||

| Pale spear-nosed bat (Phyllostomus discolor) | |||||

| Egyptian slit-faced bat (Nycteris thebaica) | |||||

| Cyclops roundleaf bat (Hipposideros cyclops) Sundevall’s roundleaf bat (Hipposideros caffer) Pseudoromicia rendalli (Neoromicia rendalli) Guinean pipistrelle bat (Pipistrellus guineensis) | (Amrein, Dechmann, Winter, & Lipp, 2007) | AHN was studied by means of the expresion of Ki-67, MCM2, DCX and NeuroD. AHN was present in Chaerephon pumila, Mops condylurus and Hipposideros caffer. In Glossophaga soricina, Carollia perspicillata, Phyllostomus discolor, Nycteris macrotis, Nycteris thebaica, Hipposideros cyclops, Neoromicia rendalli, Pipistrellus guineensis, and Scotophilus leucogaster, no positive cells were detected. Not all the antigens were recognized in all species. | |||

| White-bellied house bat (Scotophilus leucogaster) | |||||

| Little free-tailed bat (Chaerephon pumila) | |||||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| (Chawana et al., 2020) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the DG of adult Egyptian fruit bats from three distinct environments: primary rainforest, subtropical woodland, and fifth-generation captive- bred. No differences in the numbers of proliferative cells, despite higher numbers of immature neurons in wild-caught bats. | ||||

| Trident leaf-nosed bat (Asellia tridens) | (Chawana et al., 2014) | AHN was studied after euthanasia and perfusion following capture. Abundant number of DCX + cells in the DG in animals euthanized and perfused within 15 min of capture. Dramatic drop of AHN between 15 and 30 min post-capture, and absence of DCX+ neurons 30 min post-capture. | |||

| Kuhl’s pipistrelle (Pipistrellus kuhlii) | |||||

| (Chawana et al., 2014) | |||||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML and GCL. | ||||

| Afrosoricida | Hedgehog tenrec (Echinops tefairi) | (Alpar et al., 2010) | Higher numbers of BrdU+ and DCX+ cells in the SGZ of younger than in aged animals. Gradual decrease of AHN with aging. | ||

| (Patzke, Kaswera, Gilissen, Ihunwo, & Manger, 2013) | Presence of DCX+ cells with strongly labeled proceses, presumably axons and dendrites, in the SGZ and GCL. | ||||

| Hottentot golden mole (Amblysomus hottentotus) | (Patzke, LeRoy, et al., 2014) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | |||

| Primate | Prosimians | Demidoffs dwarf galago (Galagoides dmidoff), Bosman’s potto (Perodicticus potto) and Ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) Gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) | (Fasemore et al., 2018) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. | |

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of Ki-67+ proliferative cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| (Royo et al., 2018) | First evidence of the occurrence of AHN in prosimian primates. Increased number of newborn DGCs after n-3 PUFA supplementation for 21 months. | ||||

| Old World Primates | Vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) | (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||

| Olive baboon (Papio anubis) | |||||

| Snow monkey (Macaca fuscata) | (Tonchev, Yamashima, Zhao, Okano, & Okano, 2003) | Incorporation of BrdU and DCX expression in control monkeys. Ischemic damage increased the number o1 BrdU-labeled cells. Newly generated cells expressed Musashi1, Nestin, βIII-tubulin, TUC-4, DCX, Hu, NeuN, S100β, or GFAP. | |||

| (Tonchev & Yamashima, 2006) | BrdU incorporation in the adult DG. Ischemia increased the density of BrdU+ cells. BrdU+ newly generatec cells showed neuronal features 79 days after the insult. Adult-born cells remained in the SGZ and showed immature progenitor phenotype. | ||||

| (Kohler, Williams, Stanton, Cameron, & Greenough, 2011) | Protracted DGC maturation in non-human primates over a minimum of 6 months. Expression βIII-tubulin. DCX, NeuN. Delayed dendritic arborization, and acquisition of mature cell body morphology. | ||||

| Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) | (Ngwenya, Peters, & Rosene, 2006) | Maturation sequence of adult primate DGCs is similar to that of adult rodents. BrdU+ cells expressed TUC- 4. Maturation lasts a minimum of 5 weeks. | |||

| (Franjic et al., 2022) | Reconstruction of the entire AHN trajectory, from RGL cells to mature DGCs in the adult rhesus monkey Profiling of 36,107 hippocampal nuclei using sn-RNA seq. | ||||

| Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) | (Hao et al., 2022) | Profiling of 207,785 cells from the adult macaque hippocampus using sc-RNA seq. Reconstruction of the whole AHN trajectory including a heterogeneous pool of RGLs, IPCs and neuroblasts. Identification of HMGB2 as a novel IPC marker. Differences with rodent AHN. | |||

| New World Primates | Common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) | (Gould, Tanapat, McEwen, Flugge, & Fuchs, 1998) | Production of new neurons in the DG of adult monkeys. Social stress-driven reduction in the number of proliferative cells. | ||

| (Marlatt et al., 2011) | BrdU incorporation and presence of DCX+ immature neurons. Unchanged numbers of BrdU+ or DCX+ cells after 2 weeks of isolation and social defeat stress. | ||||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| Squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) | (Lyons et al., 2010) | BrdU incorporation in the DG. Increase in AHN after exposure to intermittent social separation and newpair formation. AHN positively correlated with the expression of genes involved in survival and integration of newly generated DGCs, as well as with enhanced spatial learning performance. | |||

| Macroscelidea | (Slomianka et al., 2013) | Captured sengis show fewer immature DCX+ cells without changes in proliferative PCNA+ cells than other murid species from the same habitat. | |||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) (Patzke, LeRoy, et al., 2014) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| Hyracoidea | Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) | (Patzke, LeRoy, et al., 2014) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ. The processes of the latter cells extended into the ML. | ||

| (Patzke et al., 2015) | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ and GCL. The processes of these cells extended into the ML. | ||||

| Artiodactyla | Pig (Sus scrofa) | (Franjic et al., 2022) | Reconstruction of the whole AHN trajectory from RGL cells to mature DGCs in the young adult pig. Profiling of 36,851 hippocampal nuclei using sn-RNA seq. | ||

| Swedish farm sheep (Ovis aries) | |||||

| (Brus et al., 2013) | BrdU incorporation and expression of DCX, NeuN, Sox2 and S100β. Longer maturation process than that in rodents and similar to that in non-human primates. | ||||

| Greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) | |||||

| Blue wildbeest (Connochaetes taurinus) Black wildbeest (Connochaetes gnou) Arabian camel (Camelus dromedarius) Affrican buffalo (Syncerus caffer) | |||||

| Nyala (Tragelaphus angasii) | |||||

| Common eland (Taurotragus oryx) Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) Blesbok (Damaliscus pygargus) Springbok (Antidorcas marsumalis) Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana) | |||||

| Simitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) | |||||

| Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) | |||||

| Sand gazelle (Gazella marica) River hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) | |||||

| Domestic pig (Susscrofa) | |||||

| Sirenia | West indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) | ||||

| Cetacea | Northern minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) | Small hippocampus size of cetaceans compared to that of other mammals. Lack of DCX+ cells in Northern minke whale and Harbour porpoise. | |||

| Scandentia | Tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) | (Gould, McEwen, Tanapat, Galea, & Fuchs, 1997) | Incorporation of BrdU in the SGZ. 3 weeks after injection, BrdU+ NSE+ cells with neuronal morphology were incorporated to the GCL. Presence of Vimentin+ RGL cells with their processes extending into the GCL were observed in the SGZ. Negative and positive regulation of AHN by stress and NMDA receptor activation, respectively. | ||

Table 2.

List of studies addressing the occurrence of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) in humans. ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. AD: Alzheimer’s disease. BP: Bipolar disorder. CJD: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. DLB: Dementia with Lewy Bodies. FTD: Fronto-temporal dementia. HD: Huntington’s disease. HIE: Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. LWB: Lewy body dementia. MD: Major depression. MDD: Major depressive disorder. MDD/TCA: MDD with tricyclic antidepressant. MDD/SSRI: MDD with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. MND: Motor Neuron Disease. MS: Multiple sclerosis. MTLE: Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PD: Parkinson’s disease. PDD: Parkinson’s disease with dementia. PD-MCI: Parkinson’s disease mild cognitive impairment. PD-NCI: Parkinson’s disease non-cognitive impairment. SZ: Schizophrenia. TLE: Temporal lobe epilepsy. EM: electron microscopy. ICH: immunohistochemistry. ISH: in-situ hybridization. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. PLI: polarized light imaging. qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction. snRNA-seq: single nucleus RNA sequencing. AHN: adult hippocampal neurogenesis. DGCs: dentate granule cells. DG: dentate gyrus. DMSO: Dimethyl sulfoxide. F: female. GCL: granule cell layer. gw: gestational weeks. HSV: Hue, Saturation and Value. M: male. NPCs: neural progenitor cells. NSCs: neural stem cells. PBS: phosphate saline buffer. PFA: Paraformaldehyde. PMD: post-mortem delay. SGZ: subgranular zone. SVZ: subventricular zone. AQ4: Aquaporin-4. Ascl1: Achaete-Scute family BHLH transcription factor 1. ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4. BLBP: Brain lipid-binding protein. BrdU: bromodeoxyuridine. CB: calbindin. CR: calretinin. DCX: doublecortin. EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor. GAD1: Glutamate Decarboxylase 1. GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein. Hopx: homeodomain-only protein homeobox. Iba1: Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1. MAP2: Microtubule-associated protein 2. MBP: Myelin basic protein. MCM2: Minichromosome Maintenance Complex Component 2. METTL7B: methyltransferase-like protein 7B. MHCII: major histocompatibility complex II. NeuN: Neuronal nuclear antigen. NeuroD1: Neuronal Differentiation 1. NF1A: Nuclear Factor I A. NG2: neural-glial antigen 2. Olig2: oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2. OP18: Stathmin. PAX6: Paired box 6. PCNA: proliferating cell nuclear antigen. PH3: Phospho-histone 3. PLP: proteolipid protein. Prox1: Prospero Homeobox 1. PSA-NCAM: Polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule. pTau: phospho-Tau. S100β: S100 calcium-binding protein β. Sox1: SRY-Box Transcription Factor 1. Sox2: SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2. STMN1: Stathmin1. Tuj1: Neuron-specific class III β-tubulin. Tbr2: T-box brain protein 2. This table was constructed after performing a manual search of studies that included the following terms (and their combination thereof) in the PubMed database: “Adult hippocampal neurogenesis”, “Human”, and “New neurons”. Studies not focused on the human hippocampal region or that examined only other species were manually excluded.

| Study | Methods | Subject Information | Tissue | PMD | Markers | Main results | Tissue processing | Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Eriksson et al., 1998) | IHC | Undisclosed sex (64.4 ± 2.9 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | BrdU, CB, NSE, GFAP, NeuN | Incorporation of BrdU into the adult human DG. | 4% PFA for 24 h, sectioning on a sliding microtome. | Total number of BrdU+ cells was determined in 5-7 sections from each subject. A semi-automatic image analysis system was used to estimate areas. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Blümcke et al., 2001) | IHC | Controls (embryonic, postnatal and adult tissue), undisclosed age and sex. 11F/16M TLE (8 mo–46 y) | Biopsy (TLE and Controls) and postmortem (Controls) | PMD controls (12 h– 3 d) | Nestin, Vimentin, Tuj1, Ki67, MAP1b/5, MAP2a-d, NF, NeuN, S100β, GFAP, Calbindin, CD68, CD45. | Increased neurogenesis in pediatric TLE patients. Delay in hippocampal maturation in a subgroup of TLE patients. | 4% PFA for 24 h (biopsy) or formalin (undisclosed concentration) for ≥ 2 w (autopsies). Vibratome sectioning. Antigen retrieval for Ki67, MAP2a-d and Tuj1. | Positive cells were quantified in 5 regions of interest per DG using a semi-automated imaging analysis software. The same software was used to calculate the hippocampus area. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Höglinger et al., 2004) | IHC | 2F/1M Controls (87.7±6.7 y), 2F/1M PD-NCI (71.3±4.9 y), and 2F/3M PD-MCI (85.6±5 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (31.5±7.2 h), PD-NCI (25.1±8.2 h), and PD-MCI (19.4±5.9 h) | Nestin, β-III Tubulin | The presence of Nestin+ and β-III Tubulin+neural precursor cells is reduced in the SGZ of PD patients. | Tissue was dissected, fixed and frozen (undisclosed time and fixative). Sectioned in freezing microtome. | Cells were counted in the GCL and SGZ using a semiautomatic stereology system (ExploraNova Mercator) in regularly spaced sections. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Jin et al., 2004) | IHC, WB | 3F/8M Controls (46.09±7.4 y), 1F/8M/4 undisclosed AD (76.22±3.2 y) | Post-mortem | PMD Controls (5–12 h) and AD (9–20 h) | DCX, PSA-NCAM, TUC4, NeuroD1 | Increased expression of immature neuron markers in AD patients, measured by means of WB. | Frozen samples (WB), or 4% PFA (unknown fixation time) followed by paraffin embedding. | No quantifications are presented. |

| (Boekhoorn et al., 2006) | IHC | 4F/6M Controls (67.1±2.3 y) and 5F/4M AD (66.2±2.0 y) | Post-mortem | PMD Controls (9.7 h) and AD (5.1 h) | DCX, Ki67, GFAP | Comparison of optimal pH conditions during antigen retrieval for Ki67 detection. Unaltered number of Ki67+ and DCX+ cells in the DG of presenile AD cases. | 10% formalin for 30-646 d. Paraffin-embedding and microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval was performed for Ki67. | Ki67+ cells were counted in 3-4 sections of each subject. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. For DCX and GFAP, a semi-quantitative approach was used. |

| (Reif et al., 2006) | IHC | 15 Controls (48±10 y), 15 SZ (44±13 y), 15 BP (42±12 y), and 15 MDD (46±9 y). Sex of the subjects is not reported. | Post-mortem | PMD Controls (23±9 h), SZ (33±14 h), BP (32±16 h), and MDD (24±11 h) | Ki67 | Reduced number of Ki67+ cells in SZ patients. | Frozen sections fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min. | Ki67+ cells were counted in the GCL of 7 sections per patient. Cell densities (cells/mm) were reported. |

| (Manganas et al., 2007) | Magnetic resonance spectros copy | 5 healthy subjects (M, F). Three preadolescent (8–10 y) and 3 adolescent (14– 16 y). | Living humans | Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-NMR) | Identification of NSCs in the adult human hippocampus. The presence of NSCs decreases with age. | - | Quantification of the signal amplitude (ppm). |

| (Monje et al., 2007) | IHC | Controls (10 mo–63 y) and Cancer (10 mo–61 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls and Cancer (<24 h) | DCX, Ki67, Olig2, CD68, CD20, CD3 | AHN impairments and increased inflammation after cranial radiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy. | Undisclosed fixation protocol and duration. Embedding in paraffin. | The number of cells positive for each marker/total granule cell nuclei present in DG was reported. |

| (Verwer et al., 2007) | IHC, WB, RT-qPCR | 5F/2M Controls (55–93 y), 15F/9M neurodegenerative diseases (AD, PiD, PSP, LBD, NAD, PD) (57–94 y), and 18F/11M Epilepsy (5–69 y) | Biopsy (Epilepsy) and post-mortem (AD, PiD, PSP, LBD, NAD, PD and Controls) | PMD (9–48 h). | DCX, NeuN, GFAP | Presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the hippocampus of AD patients. | Formalin-fixed tissue (undisclosed fixation time). | Semi-quantitative evaluation by means of a cellular profile scoring. |

| (Li et al., 2008) | IHC and ISH | 9F/6M Controls (83.6±7.4 y) and 7F/7M AD (79.4±10.9 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (2.6±0.6 h) and AD (2.4±0.6 h) | MAP2 | Reduced expression of MAP2a,b (mature forms) in the DG of AD patients, which suggests impaired neuronal differentiation. | Fixation in 4% PFA for 24-48 h. | Optical density was measured. |

| (Y. W. Liu et al., 2008) | IHC, WB, RT-PCR | 5F/10M Controls (18–78 y) and 15F/9M TLE (13–57 y) | Biopsy (Blümcke et al.) and post-mortem (Controls) | PMD controls (4.45–18.5 h) | DCX, PCNA, MCM2, PSA-NCAM, Tuj1, NeuN Reelin, CR, CB | The expression of DCX is increased in the hippocampus and temporal cortex of TLE patients. Co-expression of DCX and PCNA, Tuj1 and NeuN. | Perfusion/immersion in 15% formalin (undisclosed duration). | DCX+ cells along the GCL were counted using the Stereoinvestigator software. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported |

| (Boldrini et al., 2009) | IHC | 3F/4M Controls (17–53 y), 1F/4M MDD (29–62 y), 1F/2M MDD/TCA (28–61 y), and 2F/2M MDD/SSRI (24–61 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (9.5–22 h), MDD (4–22 h), MDD/TCA (9–19 h), MDD/SSRI (6–24 h) | Nestin, Ki67, NeuN, GFAP | Decreased number of NPCs with age. Increased number of NPCs in females. Antidepressant treatment increases the number of NPCs. | Frozen tissue, fixed in 4% PFA for 1w and sectioning in a freezing microtome. | Total number of cells positive for each marker was determined using the optical dissector and fractionator methods. The number of cells x 103 was shown. |

| (Mattiesen et al., 2009) | IHC | 7F/12M Controls (35–81 y) and 9F/13M HIE (35–85 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls and HIE (0–5 d) | PCNA, TUC4, CR | Increased AHN and apoptosis after HIE. Aging did not impact on the number of proliferating or apoptotic cells in control subjects. | Formalin fixation (undisclosed time and concentration) and embedding in paraffin. | The number of cells positive for each marker was counted manually. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Crews et al., 2010) | IHC, qRT-PCR, WB | 3F/2M Controls (87±4.6 y), 3F/4M Early AD (86.1±1.7 y), and 4F/3M Severe AD (80±1.9 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (9.5±3.5 h), early AD (11.8±2.8 h), and severe AD (8.2±0.8 h) | BMP6, DCX, Sox2 | Increase in the expression of BMP6 and reduction in the number of DCX+ and Sox2+ cells in AD patients. | Formalin (undisclosed concentration) or 4% PFA (undisclosed duration). Vibratome sectioning. | The number of cells positive for each marker was counted in every sixth section and were multiplied by the reference volume. Total number of cells was reported. |

| (D’Alessio et al., 2010) | IHC | 3F/2M Controls (45.8±14 y) and 6F/3M TLE (40.1±6 y) | Biopsy (Blümcke et al.) and post-mortem (Controls) | PMD not reported. | DCX | Reduced number of DCX+ cells in patients with TLE. | Formalin for 5 d (undisclosed concentration) and embedding in paraffin. Microtome sectioning. | The number of cells positive for each marker was determined by computerized image analysis. Ten fields per section were evaluated. Cell densities (cells/field) were reported. |

| (Geha et al., 2010) | IHC | 3F/2M Surgical Controls (25–66 y), 2F/3M Autopsy Controls (31–64 y), and 6F/4M TLE (22–35 y) | Biopsy (epilepsy and surgical controls) and post-mortem (controls) | PMD not reported | Ki67, MCM2, Mib-1, Tuj1, MAP2, NeuN, Calretinin, GFAP, Nestin, Olig2, NG2. | Fixation time affects the detection of cell cycle- related proteins. Patients with TLE show increased numbers of Ki67+ cells in the SGZ, which acquire glial phenotypes. | Formalin-zinc (formalin 5%; zinc 3g/L; sodium chloride 8g/L) for 3 mo (post-mortem) or 16 h (surgical), and embedding in paraffin. | Cells were counted manually for each of the 10 tissue blocks that made up each hippocampal resection. Cell densities (cells/mm2 or cells/cm2) were reported. |

| (Hong et al., 2010) | IHC | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | DCX, p-TAU (PS396, PT231, PT205). | Co-localization between DCX and p-Tau in patients with AD. | Undisclosed fixation procedure. Freezing microtome sectioning. | - |

| (Knoth et al., 2010) | IHC, ISH, WB | 28F/22M adult (1 d–100 y) and fetal (11,20, and 40 gw) Controls | Post-mortem | PMD: 1–60 h | DCX, PCNA, Ki67, MCM2, Sox2, Nestin, TUC4, Tuj1 Prox1, PSA-NCAM, GFAP, Calretinin, NeuN. | Human AHN shares features identified in rodents. Mild decrease of AHN with age. | Formalin fixation (undisclosed duration and concentration). Paraffin embedding. | DCX+ cells were counted manually in 3 sections of the anterior hippocampus of each patient. The average number of positive cells/mm2 per 3 sections was given. |

| (Lucassen et al., 2010) | IHC | 3F/7M Controls (48–85 y) and 3F/7M MD (45–84 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (4–19.15 h) and MD (4–28 h) | MCM2, PH3 | Reduction in the number of MCM2+ cells in MD patients. | 4% Formaldehyde for 4-5 w and embedding in paraffin. | The number of cells positive for each marker was quantified in 5-6 sections. Cell densities (cells/μm2) were reported. |

| (Johnson et al., 2011) | IHC | 5F/3M Controls (71–101 y) and 3F/5M LBD (75–84 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (12–84 h) and LBD (51–96 h) | PCNA, GFAP, Musashi, DCX, Nestin, α-synuclein, Aβ | Loss of Musashi and GFAP. Increase in PCNA in the SGZ and GCL, and in the number of DCX+ cells in the GCL of patients with LBD. | Undisclosed fixation protocol. Embedding in paraffin. Microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | The percentage of stained area was analyzed in 5 random images of each region. In addition, DCX+ cells were counted in the whole DG. Data were represented as the percentage of stained area per total area measured. |

| (Low et al., 2011) | IHC | 1F/7M Controls (32–81 y) and 5F/9M HD (35–75 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (9–24 h) and HD (3–24 h) | PCNA, Bcl-2, MCM2, Musashi | No differences in SGZ proliferation between control subjects and HD patients. | Perfusion and 24 h fixation with 15% formalin. Microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | Cells were counted manually. Cell density was reported as average number of positive cells per 50 μm, per μm2, and per mm of hippocampal section. |

| (Winner et al., 2012) | IHC | 3F/3M Controls (86.00±10 y) and 1F/5M LBD (81.0±9.1 y). | Post-mortem | PMD controls (12.8±7.2 h) and LBD (9.5±3.1 h) | Sox2, α-synuclein, DCX | Increased α-synuclein and decreased numbers of Sox2+ cells in patients with LBD. | Fixation in 4% PFA (undisclosed duration). | The optical dissector method was used to count positive cells. The reference volume was determined using Stereoinvestigator MicroBrightField software. 3 systematically sampled sections (10 images per section) were analyzed to estimate the average number of immunolabeled cells/mm2. |

| (Boldrini et al., 2012) | IHC | 7F/5M Controls (41.8±14.6 y), 6F/6M MDD (43.6±13.3 y), 4F/2M MDD/TCA (46.2±17.1 y), and 2F/2M MDD/SSRI (38.8 ± 13.8 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (15.3±4.8 h), MD (16.0±5.9 h), MD/TCA (12.1±5.2 h), and MD/SSRI (15.8±7.5 h) | Ki67, Nestin, PECAM, Collagen IV | Decreased number of Nestin+ cells with age. SSRI treatment increases the number of Nestin+ cells in the DG of MD patients. | 4% PFA (undisclosed duration) and freezing. Freezing microtome sectioning. | The number of positive cells, area occupied by capillaries, and the volume and length of the DG, CA1 and parahippocampal gyrus were calculated using the optical dissector and fractionator methods. Total number of cells was reported. |

| (Perry et al., 2012) | IHC | 13F/8M Controls (80.9±8.5 y) and 13F/7M AD (81.2±7 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | Musashi, Nestin, PSA-NCAM, DCX, Tuj1, ChAT | Reduced immunoreactivity of Musashi and ChAT, and increased immunoreactivity of Nestin+ and PSA NCAM+ in AD. Higher levels of DCX in the GCL of AD patients. No changes in Tuj1. | 4% Formaldehyde for 4 w and embedding in paraffin. Microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval | A threshold was established to detect immunopositive signal. The integrated optical density was reported. |

| (Epp et al., 2013) | IHC | 4F/8M Controls (46.8±3.49 y), 5F/7M MDD (42.83±2.92 y), and 6F/6M MDD- psychosis (41.5±3.47 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | DCX, p21, NeuN | Increased number of DCX+/NeuN cells in patients with depression. | Frozen tissue, cryosectioned and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15 or 45 min. | The number of cells was counted in the GCL and SGZ of each section. Cell densities (cells/mm2) or the total number of NeuN cells per subject within the region of interest were reported. |

| (Spalding et al., 2013) | C14 dating | 32F/88M Controls (16–92 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | C14 incorporation | Mild decrease in AHN with aging. 700 new neurons are added daily to the human DG. | Frozen tissue. Homogenized for nuclei isolation. | The rate of new neurons added into the human DG was calculated by retrospectively birth dating cells (ΔC14) and a mathematical model based on cell death rate, and the fractions of renewing and non-renewing cells. |

| (Ernst et al., 2014) | IHC, WB | 4 (undisclosed sex) Controls (20–71 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | DCX, PSA-NCAM, MAP2, IdU, caspase-3 | Expression of immature neuron markers, as well as IdU incorporation in the SGZ. | Frozen tissue, sectioned by cryostat and fixed in 2% formaldehyde for 10 min. For IdU, formalin-fixed (undisclosed protocol) and embedding in paraffin sections were used. Antigen retrieval. | Undisclosed. |

| (Gomez-Nicola et al., 2014) | IHC | 5F/5M Controls for CJD variant (20–35 y), 4F/5M Controls for AD (58–79 y), 5F/5M CJD variant(20–34 y), and 5F/5M AD (58–76 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | Ki67, Sox2, CR | Increased number of Ki67+ and CR+, but no changes in that of Sox2+ cells in patients with AD and CJD variant. Decreased numbers of these cell populations in aged controls. | Formalin-fixation (undisclosed protocol) and embedding in paraffin. Antigen retrieval. | The number of positive cells was counted in 4-5 fields per DG sample using ImageJ. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Bayer et al., 2015) | IHC | 6F/22M Controls (17–41 y) and 8F/12M heroin users (17–45 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (2.4 d) and heroin users (2.6 d) | Musashi, Nestin, Ki67, CR, GFAP, NeuN, Tuj1, DCX | Reduced number of Musashi+ and Nestin+ progenitor and proliferating cells in heroin users. | Fixation in 4% formaldehyde for 48 h-5 y, embedding in paraffin and microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | The number of positive cells was counted manually in at least 3 fields of the GCL, SGZ and CA4. Total cell numbers, percentage of positive cells/total cell numbers, and cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (D’Alessio et al., 2015) | IHC | 4F/4M Controls (23-60 y) and 7F/9M TLE (22–51 y) | Biopsy (Blümcke et al.) and post-mortem (Controls) | PMD not reported | Nestin | Reduced number of Nestin+ cells in patients with epilepsy. | Formalin-fixation (undisclosed concentration) for 5 d, embedding in paraffin and microtome sectioning. | The number of Nestin+ cells, mean gray value and reactive area (px2) were determined along the GCL in 10 fields per section. |

| (Ekonomou et al., 2015) | IHC | 5F/7M Braak-Tau stages 0-II (80.3±8.4 y), 8F/3M Braak-Tau stages III-IV (88.9±8.2 y), and 1F/4M Braak-Tau stages V-VI (86.8±5.3 y) | Post-mortem | PMD Braak-Tau stages 0–II (12–28 h), Braak-Tau stages III-IV (7–27 h), and Braak-Tau stages V-VI (9.5–33 h) | HuC/HuD, Nestin, PCNA, GFAP, Iba1 | Reduced number of HuC/HuD+ cells in patients at Braak-Tau V-VI stages. Increased presence of DCX+ cells in patients with dementia at advanced Braak-Tau stages. | Undisclosed fixation protocol. Paraffin embedding. Antigen retrieval. | The hippocampus area was measured on each section. Cell densities (cells/mm) were reported. |

| (Allen et al., 2016) | IHC | 3F/13M Controls (21–81 y) and 5F/5M SZ (55-75 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (10–50 h) and SZ (12.5–72 h) | Ki67, NeuN | Reduced number of Ki67+ cells in patients with SZ. | Frozen tissue, fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at 4°C. | The density of Ki67+ (number of cells/mm2) within the SGZ, GCL and hilus was calculated in 3 slides per case. Stereoinvestigator was used to measure the area on each section. |

| (Dennis et al., 2016) | IHC | 9F/14M Controls (0.2–59 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (15–90 h) | Ki67, DCX, Tuj1, Olig2, EGFR, GFAP, PCNA | Marked decrease in proliferation and neuroblasts with age. Among the proliferating cell population, only microglial cells were identified | 15-20% formalin-fixation for 2-3 w. Paraffin embedding. Antigen retrieval. | Ki67+, DCX+ and PCNA+ cells were counted within the entire SVZ and SGZ of each section. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Galan et al., 2017) | IHC | 1F/3M Controls (69.50±11.38 y) and 4F/5M ALS (65.60±15.94 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls and ALS (5±2 h) | Ki67, PCNA, GFAPδ, PSA-NCAM, DCX, Tuj1, GFAP, TDP43 | Proliferation and PSA- NCAM+ markers in the SGZ were decreased in patients with ALS. | Undisclosed fixation protocol. Paraffin embedding and vibratome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | Cells were counted in ~10 fields for each marker. Cell densities (cells/500 μm2) were reported. |

| (Mathews et al., 2017) | qPCR, IHC | 4F/22M Controls for qPCR and 1F/4M Controls for IHC (18–88 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (9–51 h) | Ki67, DCX, GFAPδ, GFAP, Tbr2 | Reduced DCX and Ki67 mRNA expression with aging. | Dissected and fresh frozen tissue (qPCR). Formalin-fixed (undisclosed fixation protocol) and embedded in paraffin (IHC). | 3 randomly selected areas of the hilus were photographed for visual analysis. No cell density values were reported. |

| (Oreja-Guevara et al., 2017) | IHC | 1M Control (undisclosed age) and 1M MS (27 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | GFAPδ, Musashi, Sox2, Pax6, NG2, Ki67, PCNA, Iba1, CD68, MHCII, Tuj1, DCX, PSA-NCAM, MBP, AQ4, Nestin, Olig | Low numbers of NSCs, intermediate progenitors and proliferation. Early AHN impairments in MS. | Fixation in 4% PFA (undisclosed time), paraffin embedding, and microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | 8 random images from each section were analyzed. Cell densities (cells/mm2 or cells/mm) were reported. |

| (J. Liu et al., 2018) | IHC | 5 Developmental Controls (12–13 gw), 6F/9M Adult Controls (28–75 y), and 20F/22M Epilepsy (8–76 y) | Biopsy (epilepsy) and post-mortem (Controls and epilepsy) | PMD not reported | Nestin, DCX, Musashi, Tuj1, NeuN, GFAPδ, MAP2, Olig2, MCM2, AQ4, GS, ZnT3, CD34 | Increased densities of Nestin+ cells in patients with epilepsy. | Formalin-fixed (undisclosed protocol) and embedding in paraffin. | Semiquantitative evaluation of the number of Nestin+ cells. No cell density values were reported. |

| (Le Maitre et al., 2018) | IHC | 6F/11M Controls (24–78 y) and 1F/17M Alcohol consumers (30–67 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (11.25–84.5 h) and Alcohol consumers (5.25–64 h) | NeuN, DCX, Sox2, Ki67 | Reduction of AHN markers in alcohol consumers. | Flash-frozen tissue, fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15-30 min and cryosectioned. | Positive cells for each marker were counted along the entire length of the GCL in the DG, in 5 sections/case. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Boldrini et al., 2018) | IHC | 11F/17M Controls (14–79 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (4–26 h) | PSA-NCAM, Sox2, Nestin, Ki67, DCX, NeuN, GFAP | Preserved numbers of intermediate progenitors and immature neurons, and decrease in quiescent progenitors throughout aging. | Flash-frozen tissue, fixed in 4% PFA (undisclosed duration) and microtome sectioning. | 10-12 sections per subject were analyzed along the rostro-caudal axis of the hippocampus. The optical dissector with fractionator approach was used with Stereoinvestigator software to estimate total cell numbers in the selected region |

| (Cipriani et al., 2018) | IHC | 39 Controls (13 gw–72 y) and 5 AD (74–89 y). Undisclosed sex. | Post-mortem | PMD controls (4–72 h, 27 subjects undisclosed) and AD (3–23 h) | Nestin, GFAP, DCX, Ki67, MCM2, Sox2, Pax6, Tbr2, Vimentin, Tuj1. | Reduction of RGL, proliferative, and DCX+ cells in the adult human DG. | Frozen tissue was fixed in 4% PFA (undisclosed duration), embedded in paraffin and cryosectioned. | Semiquantitative analysis. No cell densities or numbers were reported. |

| (Sorrells et al., 2018) | IHC, EM | 13F/24M Controls (14 gw–77 y) and 11F/11M Epilepsy (3m–64 y) | Biopsy (epilepsy) and post-mortem (controls) | PMD controls (<48h) | Ascl1, BLBP, DCX, BrdU, GFAP, Hopx, Ki67, MCM2, Nestin, NeuN, NeuroD, Olig2, Pax6, Prox1, PSA-NCAM, Sox1, Sox2, Tbr2, Tuj1, Vimentin, Iba1 | Absence of AHN markers in the adult human DG. | Perfusion with 4% PFA, fixation in either 4% PFA or 10% formalin (undisclosed duration). Additional fixation in 4% PFA for 2 days. | Quantification of 3-5 images across a minimum of 3 randomly selected sampled sections for each age. The DG was subdivided into subregions of interest (GCL, hilus and ML). Cell densities (cells/mm2) and total cells/section were reported. |

| (Stepien et al., 2018) | IHC | 2F/6M Controls (64±10.95 y), 7F/7M Non-hemorrhagic stroke (70±6.03 y), and 2F/6M Hemorrhagic stroke (64.75±12.23 y) | Post-mortem | PMD not reported | GFAP, PH3 | Presence of neural stem cells and NPCs observed in the DG and SVZ. Increased number of PH3+ cells in patients with hemorrhagic stroke. | Undisclosed fixation protocol and embedding in paraffin. Rotary microtome sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | Quantitative analysis was performed using the CellSens software. Cells were counted in the DG and SVZ. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Tartt et al., 2018) | IHC, ISH, RNAsco pe | 5 Controls, 5 antidepressant-treated, and 5 untreated subjects with MDD (19–67 y). Undisclosed sex. | Post-mortem | PMD control, antidepressant-treated, and untreated MDD patients (6–27 h) | DCX, NF, Sox2, PSA-NCAM, NeuN | Detection of AHN markers by means of RNAscope. | Flash-frozen tissue. Undisclosed fixation protocol. | Cells expressing DCX mRNA were quantified in 3 sections of the anterior-mid DG. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Gatt et al., 2017) | IHC | 15 Controls (80.47±8.48 y) and 41 LBD/PDD (79.98±5.32 y). Sexes were equally represented (52% F 48% M). | Post-mortem | PMD controls (34.26±17.32 h) and LBD/PDD (36.30±25.5149.95±21.57 h) | DCX | Increased presence of DCX+ immature neurons in the SGZ of patients with LBD/PDD. Higher expression of DCX in patients treated with SSRI. Higher DCX expression corelated with higher cognitive scores. | Undisclosed fixation protocol. Paraffin-embedded tissue. Antigen retrieval. | DCX+ cells were counted throughout the entire DG. Cell densities (cells/mm) were reported. |

| (Gomez-Pinedo et al., 2019) | IHC | 4 (undisclosed sex) Controls and 5F/7M MND (ALS or ALS-FTD) (37–87 y). | Post-mortem | PMD controls and ALS (2–6 h) | PCNA, Ki67, GFAPδ, PSA-NCAM, DCX, Tuj1, Iba1, Nestin | Decrease in the proliferative and neurogenic activity, and number of GFAPδ+ cells and neuroblasts in patients with ALS. | Samples were fixed with 10% formalin-(undisclosed time), embedded in paraffin, and microtome sectioned. Antigen retrieval. | The number of cells was determined in 5 slides per patient with 32 fields/slide (CA1, CA2, CA3 and DG). ImageJ was used to measure optical density. The relative number of inclusions was divided by the mean number of neurons per field (cells/mm2). |

| (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019) | IHC | 4F/9M Controls (43–87 y) and 19F/26M AD (52–97 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (3–38 h) and AD (2.5–10 h) | DCX, PH3, GFAP, Prox1, Tau, NeuN, CR, CB, Tuj1, PSA-NCAM, Aβ | Persistence of AHN markers in neurologically healthy control subjects, mild decrease in AHN with aging, and sharp decrease in AD patients. | Fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h. Vibratome sectioning. Mild and optimized antigen retrieval (limited number of microwave cycles avoiding boiling, 20 min in a commercial citrate buffer at 80°C). | The number of cells was estimated using the physical dissector method adapted to confocal microscopy. Cells were counted on 5–20 stacks of images obtained from 10 sections/subject. The number of cells was divided by the reference volume of the GCL in each image. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Seki et al., 2019) | IHC | 6M Controls (16–49 y) and 4F/8M Epilepsy (9–43 y) | Biopsy | PSA-NCAM, Ki67, HuB, DCX, GFAP | Reduced numbers of Ki67+/HuB+/DCX+ cells in the adult DG. | Fixed in 4% PFA for 3 d and frozen; cryostat sectioning. Antigen retrieval. | The number of cells positive for each marker in the GCL was counted in 2-5 sections/subject. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Tobin et al., 2019) | IHC | 3F/3M Controls (79–93 y) and 11F/1M AD (85–99 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (4.92–20.17 h) and AD (4.42–43.55 h) | DCX, PCNA, Nestin, Sox2, Ki67 | Persistence of AHN markers during aging and AD patients. AHN correlated with cognitive scores. | Undisclosed fixation method. Paraffin embedding. Antigen retrieval. | Cell counts were calculated in 2-4 sections/subject using the optical fractionator workflow of StereoInvestigator. Cell densities (cells/mm3) or total cell numbers were reported. |

| (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020) | IHC | 4F/9M Controls (43–87 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (3–38 h) | DCX, NeuN, PSA-NCAM, MAP2, CB, Prox1, CR, PH3, GFAP, Tuj1, Tau, S100β | Reduced expression of NeuN in DCX+ cells as compared to fully mature DGCs. | 4% PFA for 24 h and vibratome sectioning. Mild and optimized antigen retrieval (limited number of microwave cycles avoiding boiling, 20 min in a commercial citrate buffer at 80°C). | A modified physical dissector method coupled to confocal microscopy was used to quantify cell densities inside a reference volume. The number of cells was divided by the reference volume of the GCL in each image. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021) | IHC | 5F/10M Controls (43–87 y), 6F/6M ALS (48–80 y), 2F/4M HD (47–72 y), 6M DLB (62–89 y), 1F/2M PD (73–82 y), and 2F/4M FTD (56–87 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (3–38 h), ALS (5–12 h), HD (6–17 h), DLB (3–10 h), PD (5–10 h), and FTD (3.5–12 h) | S100β, DCX, Nestin, Sox2, PH3, HuC/HuD, PSA-NCAM, CR, NeuN, CB, Iba1, pTau, Tau3R, UEA1, htt, pTDP43, α-synuclein | In patients with neurodegenerative diseases, adult-born DGCs show abnormal morphological development and changes in the expression of differentiation markers. Ratio of quiescent to proliferating hippocampal neural stem cells shifts, and homeostasis of the neurogenic niche is altered. | Samples were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h, included in 10% sucrose-4% agarose and vibratome-sectioned. Mild and optimized antigen retrieval (limited number of microwave cycles avoiding boiling, 20 min in a commercial citrate buffer at 80°C). | The number of cells was estimated by using the physical dissector method adapted to confocal microscopy. Cells were counted on 5–20 stacks of images obtained from 5-10 sections/subject. The number of cells was divided by the reference volume of the GCL in each image. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported.). |

| (Franjic et al., 2022) | IHC; snRNA-seq | 2F/4M Controls for snRNA-seq (44–79 y), 3F/3M Controls for IHC (38–76 y), and 3F/11M AD for IHC (61–89 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (2–26.1 h) and AD (8–28 h) | DCX, GAD1, METL7B | Absence of AHN transcriptomic and histological signatures. | Frozen tissue for snRNA-seq. Fresh tissue for IHC, fixed with 4% PFA/PBS (undisclosed duration) followed by 30% sucrose/PBS. High intensity antigen retrieval (20 min in citrate buffer pH 6 at 95°C) for DCX. No antigen retrieval for PSA-NCAM detection. | Undisclosed quantification protocol. |

| (Ammothum kandy et al., 2022) | IHC | 3F/6M Controls (21–56 y) and 12F/6M TLE (20–56 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls and TLE (6–23 h) | Arc, DCX, c-fos, Ki67, GAD65/67 GFAP, Iba1, Prox1, PSA-NCAM, S100ß, Tuj1, GluR2/3 | Longer duration of epilepsy is associated with a sharp decline in neuronal production. | Fixation in 4% PFA (12 h per mm of tissue thickness) and microtome sectioning. | Quantifications were performed manually on Zeiss blue software. The GCL boundaries were determined using the DAPI channel. Cells were counted in the whole section. Cell densities (cells/mm3) were reported. |

| (Wang et al., 2022) | snRNA-seq, IHC | 2F/4M Controls (52–92 y) | Post-mortem | PMD controls (5–22.7 h) | PCNA, PAX6, Sox2, ETNPPL, NEUROD1, STMN1, STMN2, CB, Ki67, DCX, NeuN, Ascl1, HES6, Prox1, NNAT. | Presence of AHN transcriptomic and histological signatures such as proliferative NSCs, and immature neuron markers. | Blocks were either frozen in liquid nitrogen (snRNA-seq) or fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C (IHC). Sectioned by cryostat. Antigen retrieval. | No quantification protocol reported. Images obtained by confocal microscopy and analyzed with ImageJ software. Cell densities (cells/mm2) were reported. |

| (Zhou et al., 2022) | snRNA-seq, IHC, in vitro slice culture | Sn-RNAseq: 0–2 y, 3M/1F; 3–6 y, 2M/2F; 13–18 y, 2M/2F; 40–60 y, 4M/1F; 86–92 y, 2M/3F; AD, 73–88 y, 4M/4F; and matched controls, 73–88 y, 6M/2F. IHC: 16M/8F (20 gw– 64 y) Slice culture: 5M/5F (2-61 y) | Biopsy (slice culture) and Post-mortem | PMD sn-RNAseq: 2.3–44 h. IHC: 5.9–43 h. | ATF4, CB, Caspase 3, DCX,Iba1, Math3, Ki67, NeuN, NEUROD1, NFIA, OLIG2, OP18, Prox1, S100β, STMN1, Tbr2. | Presence of immature neurons and proliferative progenitors in the human DG. In vitro EdU incorporation. Low-frequency proliferation and extended maturation. Decreased number of immature DGCs in patients with AD. | Blocks were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for 24–48 h and cryoprotected. Forty- μm sections obtained in a frozen sliding microtome. A small proportion of the blocks was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Incubation with 0.5% NaBH4 for 30 min. Antigen retrieval with target-retrieval solution (DAKO). | PROX1+ DGCs or DAPI+ cells Were counted by semi-automated nuclear staining quantification using Fiji. SGZ and GCL were delineated using Prox1 staining. No quantification protocol reported for other cell counts. |

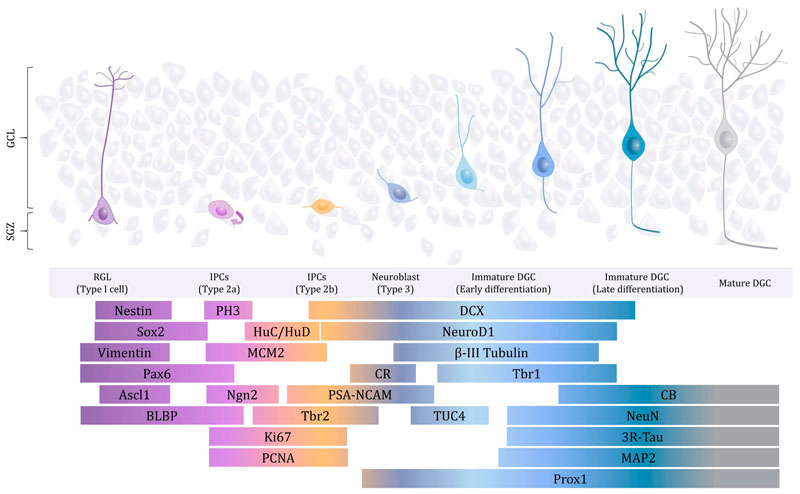

AHN has various sequential stages (Fig. 1) (Kempermann et al., 2004). Two main strategies, namely the birthdating of newly generated proliferative cells (Altman, 1963) and the detection of specific cell markers (Kempermann et al., 2004), have been used to thoroughly characterize AHN. This process relies on the presence of radial glia-like (RGL) neural stem cells (NSCs) in the dentate gyrus (DG) germinative matrix, namely the subgranular zone (SGZ). NSCs give rise to transit-amplifying progenitors and neuroblasts, which show a high proliferative capacity and expand neurogenic cell populations while progressively becoming committed to the neuronal lineage. In contrast, NSCs are mostly quiescent, a phenomenon proposed to be accentuated in aged individuals to preserve the pluripotency of these cells throughout life (Bottes et al., 2021; Harris et al., 2021). Neuroblasts are characterized by an immature neuronal morphology and the expression of proteins related to the cytoskeleton and cell plasticity, such as Doublecortin (DCX) and Polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM). After exiting the cell cycle, newborn neurons go through sequential differentiation stages before becoming fully mature. Throughout their maturation, DGCs progressively occupy deeper positions in the granule cell layer (GCL) and show not only more complex dendritic morphologies but also the presence of functional dendritic spines and axons (Zhao et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the main stages encompassed by adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN). The expression of Nestin, SRY-box 2 (Sox2), Vimentin, Paired box 6 (Pax6), Achaete-Scute family BHLH transcription factor 1 (Ascl1), Brain lipid-binding protein (BLBP), Phospho-Histone 3 (PH3), Human neuronal proteins C and D (HuC/D), Minichromosome maintenance protein 2 (MCM2), Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2), T-box brain protein 2 (Tbr2), Ki67, Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), Doublecortin (DCX), Neurogenic differentiation 1 (NeuroD1), β-III Tubulin, Calretinin (CR), Polysialic acid-neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM), Prospero Homeobox 1 (Prox1), T-box brain protein 1 (Tbr1), Turned On After Division/Ulip/ CRMP-4 (TUC-4), Calbindin (CB), Neuronal nuclei (NeuN), Three-repeated Tau (3RTau), and Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) is shown. GCL: Granule cell layer. SGZ: Subgranular zone. RGL: radial glia-like. IPCs: Intermediate progenitor cells. DGC: dentate granule cell.

The history of human adult hippocampal neurogenesis

As in the rodent AHN field (Altman, 1963), birthdating strategies were initially used to assess the occurrence of AHN in humans. In 1998, Eriksson et al. observed that the peripheral administration of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) results in the uptake of this molecule into discrete proliferative cells of the human DG, thereby supporting the occurrence of AHN in our species (Eriksson et al., 1998). That pioneering study showed that, several weeks/months after BrdU administration, BrdU-labeled cells express neuronal markers. In 2014, Eriksson’s results were further confirmed by Ernst et al. (Ernst et al., 2014), who used a different thymidine analog (5-Iodo-2’-deoxyuridine, IdU) and also observed the incorporation of this molecule into the adult human DG. Their results were further corroborated by a novel methodology, developed by Frisen’s group, to measure the incorporation of C14 into the brain (Spalding et al., 2013). Their studies determined that ~700 new neurons per hemisphere are added daily to the human DG.

In recent decades, numerous studies have used immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess the occurrence of AHN in the human brain. Most of this work (see Table 2) systematically reported the presence of cells positive for AHN markers throughout human life (Boldrini et al., 2018; Cipriani et al., 2018; Eriksson et al., 1998; Knoth et al., 2010; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Spalding et al., 2013; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). In this regard, despite decreasing throughout physiological aging, AHN remains detectable until the ninth decade of life (Boldrini et al., 2009; Knoth et al., 2010; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). Paradoxically, other studies failed to detect cells positive for such markers in the same region (Sorrells et al., 2018), although some of the authors of the aforementioned publication affirmed the existence of human AHN in previous studies (Galan et al., 2017). Given the specific conditions required to perform and validate IHC results on human tissue (Boekhoorn et al., 2006; Flor-Garcia et al., 2020), technical aspects need, more than ever, to be carefully dissected and taken into consideration when addressing these seemingly contradictory results. Indeed, an exhaustive revision of the literature available reveals that tissue processing methodologies differed markedly across the studies (see Table 2). Moreover, several articles do not disclose the criteria used to validate antibodies signal on human tissue, tissue fixation protocols, detailed antigen retrieval procedures, cell counting methods, etc. In this regard, studies by our group quantitatively demonstrate that the fixation time, type of fixative, tissue pre-treatment, and IHC protocols dramatically limit the extent to which AHN markers are visible in the human brain (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021), as will be further discussed throughout this review.

Critical steps to study human AHN by IHC

Tissue fixation

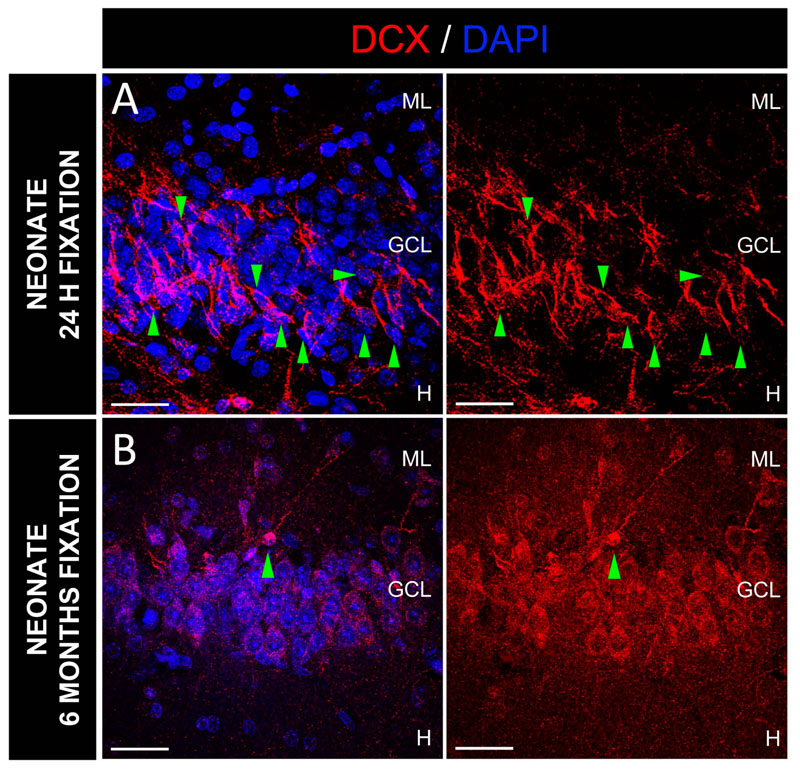

Our studies (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021) demonstrate that prolonged fixation impedes the visualization of numerous AHN markers in the human hippocampus. Most of the antibodies used to detect these markers show optimal performance in samples fixed for ≤ 24 h in 4% freshly prepared PFA at 4°C (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019). The use of samples fixed for such short periods allows reconstruction of the main stages encompassed by human AHN, thereby enabling visualization of mature and immature neurons at distinct stages of differentiation (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021), proliferative cells (Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021), and NSCs (Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021) in the adult human DG until at least the ninth decade of life.

To determine whether the performance of antibodies used to detect AHN markers on human brain tissue depends on the duration of tissue fixation, we obtained the whole hippocampus from several neurologically healthy control subjects (61–87 years of age). Subsequently, we divided these hippocampi into several fragments. Each fragment was fixed for a different period (namely, 1, 2, 6, 12, 24, or 48 h) in 4% freshly prepared PFA at 4°C. We next compared, for each subject, the numbers of DCX+ and PSA-NCAM+ immature neurons that were detected upon distinct fixation times (Extended Data Fig. S2 of (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019)). One hour of fixation rendered excessively fragile samples, which also showed diminished signal intensity. Conversely, fixation times between 2 and 12 h increased tissue robustness and allowed smooth vibratome tissue sectioning and the unambiguous observation of DCX+ and PSA-NCAM+ immature neurons. The specific signal detected in these samples was accompanied by very low background intensity. Importantly, no tissue pre-treatment was needed to detect DCX+ or PSA-NCAM+ DGCs in samples fixed up to 12 h. Conversely, prolonged fixation (≥ 24 h) increased background intensity and masked antibody-specific signal, thereby impeding the detection of positive cells. The antigen masking caused by moderate fixation times (24-48 h) was easily reversed by applying mild antigen retrieval, sodium borohydride (NaBH4) incubation, and autofluorescence elimination, as will be discussed in the next sections of this review. The optimized protocols developed by our group (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020) demonstrate the importance of the mildness of the antigen retrieval step. Despite the public availability of these protocols and data, high-intensity antigen retrieval protocols were applied in recent studies, thereby leading to the observation of an unspecific DCX signal (Franjic et al., 2022; Sorrells et al., 2021) (Table 2), as our own experiments predicted (Fig. 4C in (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020)).

Post-mortem delay (PMD)

The PMD, also referred to as the post-mortem interval or the delay to fixation, can be defined as the time elapsed between exitus and sample immersion in fixative. It should not be confounded with the fixation time (namely the time during which a sample is immersed in a fixative). Despite legal issues that unavoidably lengthen the PMD, several studies recommend the use of samples with the shortest PMD possible (de Ruiter, 1983; Eymin et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 2016; Sorensen, 1984). In general terms, proteins and ribonucleic acid (RNA) may be sensitive to post-mortem degradation (Perrett et al., 1988). In fact, several authors (Kempermann et al., 2018; Lucassen, Fitzsimons, et al., 2020; Lucassen, Toni, et al., 2020) pointed to prolonged PMDs as the cause for the putative absence of AHN markers in the human DG reported by Sorrells et al. (Sorrells et al., 2018).

However, subsequent research revealed that, although certain proteins may show particularly rapid post-mortem degradation (Boekhoorn et al., 2006; Sorensen, 1984; Terstege et al., 2022), especially in certain regions of the brain (Siew et al., 2004), the immunodetection of most proteins and enzymes is moderately resistant to this phenomenon (Blair et al., 2016; Ritchie et al., 1986; Schut et al., 2017; Y. Wang et al., 2000). For instance, although NR2A and NR2B subunits appear to be rapidly degraded after death (Y. Wang et al., 2000), most subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors are stable at ~18 h PMD. Studies performed by Boekhoorn et al. (Boekhoorn et al., 2006) and Terstege et al. (Terstege et al., 2022) suggested enhanced susceptibility of DCX to post-mortem degradation. These authors observed that, in rat samples with artificially induced prolonged PMDs (≥ 8 h), DCX staining disappears from the dendrites and is restricted to the soma and nucleus of immature DGCs. Terstege et al. reported that this phenomenon is accentuated in aged animals (Terstege et al., 2022). DCX is detected in the human DG at prolonged PMD intervals (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). Our quantitative and qualitative data reveal the stability not only of the number of DCX+ immature neurons in the human DG but also dendritic staining with this marker up to at least 38 h PMD. These results suggest putative interspecies differences in either the sensitivity of DCX protein to degradation or the binding capacity of distinct anti-DCX antibodies to their respective epitopes. However, these hypotheses lack further experimental evidence.

In line with our results that moderate PMDs are compatible with the study of most AHN markers in the human brain using IHC, recent work performed on 556 post-mortem human brains (6–279 h PMD) showed no significant correlation between brain pH, a widely used tissue quality indicator, and the PMD (Robinson et al., 2016). Another study (Blair et al., 2016) elegantly analyzed the intra-individual effects of artificially increasing PMDs. Those authors reported unchanged immunostaining profiles for most of the proteins studied after ≥ 50 h PMD, although degradation patterns were observed for several proteins by means of western blot (Blair et al., 2016). These carefully controlled experiments question the generalized notion that extended PMD is detrimental per se for the study of the human brain using IHC. Nevertheless, the results by Boekhoorn et al. (Boekhoorn et al., 2006) and others (Terstege et al., 2022), together with the fact that the sensitivity of a particular protein to post-mortem degradation cannot be predicted, indicate that performing adequate controls for each protein of interest and reporting individual PMDs should be mandatory in research protocols or scientific studies. Moreover, the use of materials with the shortest PMD possible is recommended when studying novel or putatively labile molecules (Robinson et al., 2016), and when setting up and validating new methodologies, such as single-cell (sc) or single-nucleus (sn) RNA-seq (Kalinina & Lagace, 2022).

Autofluorescence elimination

The aged human brain is particularly enriched in a lipid pigment named lipofuscin (Glees & Hasan, 1976). Neurons accumulating lipofuscin show a characteristic granular morphology that has been described under transmitted light, fluorescence, and electron microscopy (Glees & Hasan, 1976). The presence of lipofuscin granules in the human brain increases with age but starts to be observed during the first decade of life (Goyal, 1982). Indeed, immature and newly generated neurons exhibit less lipofuscin than their developmentally generated counterparts (Ernst et al., 2014; Roeder et al., 2022; Spalding et al., 2013).

In addition to the presence of abundant lipofuscin granules, brain tissue shows a great amount of primary background fluorescence (autofluorescence). It has been known for several decades that the autofluorescence of cell and tissue components depends on the fixative used and fixation time, as well as on excitation wavelength (Del Castillo et al., 1989). In particular, aldehyde fixation causes higher autofluorescence than methanol or ethanol/acetic acid (Del Castillo et al., 1989). Autofluorescence related to aldehyde fixation is attributed to the formation of Schiff’s bases between amines released upon cell death and the aldehydes present in the fixative solution (Willingham, 1983). Importantly, Schiff’s bases show high autofluorescence capacity. In fact, the intense autofluorescence observed in the human brain compromises the visualization and signal specificity of numerous antibodies. Several strategies have been used to decrease or eliminate autofluorescence in this tissue. Clancy et al. showed that a 30-min immersion of free-floating brain tissue sections in a sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 0.1%) solution reduces background fluorescence by ~30% (Clancy & Cauller, 1998), as this compound neutralizes Schiff’s bases by reducing the amine-aldehyde compounds into their corresponding non-fluorescent salts (Clancy & Cauller, 1998; Willingham, 1983). We (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021) and others (Boldrini et al., 2018; Boldrini et al., 2009) have successfully subjected such samples to NaBH4 incubation when studying human AHN. In particular, our data revealed that a 30-min incubation with a 0.5% solution of NaBH4 reduces background autofluorescence by ~40% (Fig. 4E – F in (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020)) and is therefore optimal for the visualization of several AHN markers in the human DG (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021).

Other reagents, such as Sudan black (Baschong et al., 2001; Kajimura et al., 2016), are useful to remove autofluorescence from human brain tissue. In particular, the use of commercial solutions of Sudan Black (such as the Autofluorescence Eliminator reagent (EMD Millipore)) reduces background and lipofuscin granule intensity in human DG samples, thereby facilitating the identification of AHN markers (Fig. 5 in (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020)). Other strategies, such as the use of LED lamps to quench fluorophores, have been assayed to eliminate autofluorescence in predominantly non-mitotic tissues such as the human brain (Sun et al., 2017).

In our hands, the most effective strategy to remove autofluorescence from aldehyde-fixed human brain samples combines a 30-min incubation with a 0.5% solution of NaBH4 before IHC with a brief (5-min) incubation with a commercial solution of Sudan Black (Autofluorescence Eliminator reagent (EMD Millipore)) at the end of the IHC protocol (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). Importantly, none of these steps should be confounded with antigen-retrieval protocols, aimed at unmasking antibody-specific signal and which are further discussed below.

Antigen retrieval

Although some epitopes are unaffected by the PMD (Bowers et al., 2003), epitope masking might unavoidably occur after prolonged aldehyde fixation. This process prevents antibodies from detecting and binding the antigens they have been raised against. To unmask epitopes that are especially sensitive to the fixation process, distinct antigen retrieval protocols can be applied to increase the specificity of the signal detected (Smith & Lippa, 1995). We and others have observed that antigen retrieval protocols are necessary to detect only certain antigens and under specific fixation conditions (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2022a, 2022b). In this regard, the detection of DCX in samples fixed for ≤ 12 h does not require the application of antigen retrieval protocols (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019). In contrast, samples fixed for 24-48 h, need to be subjected to a mild heat-mediated citrate buffer antigen retrieval protocol (HC-AR) (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019). The mildness of the latter step is crucial to increase the intensity of the specific signal without affecting that of the background (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020). Conversely, our studies show that the application of a harsh antigen retrieval approach cause the appearance of an unspecific antibody signal (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020). We have optimized an antigen retrieval protocol to achieve high-quality performance on human DG samples (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). This protocol consists of exposing brain samples immersed in a commercial citrate buffer-based solution to short and strictly controlled microwave radiation cycles, followed by a subsequent 20-min incubation in a water bath. Given that aggressive antigen retrieval may lead to lack of signal specificity, our results show that finely adjusting the characteristics of antigen retrieval protocols is an essential step required to perform rigorous AHN studies (Fig. 4C in (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020)).

Other authors have reported that, depending on the duration of tissue fixation, distinct antigen retrieval conditions are optimal for the detection of particular epitopes. In general, long fixation times require high-intensity antigen retrieval (increased heating duration and/or use of lower pH values (Taylor et al., 1994)). For instance, it has been proposed that the detection of the proliferation marker Ki-67 is optimal when antigen retrieval is performed at low pH (Shi et al., 1995), whereas standard pH 6.0 is suboptimal for samples fixed for longer than 24 h (Munakata & Hendricks, 1993). In fact, Boekhoorn et al. (Boekhoorn et al., 2006) compared the adequacy of antigen retrieval under distinct pH conditions, namely pH 1.0 (0.1 M HCL), pH 3.0 (0.01 M citrate buffer), pH 6.0 (0.01 M citrate buffer) and pH 9.0 (0.01 M Tris)), to detect Ki-67+ signal in the human DG. Those authors concluded that the lowest pH renders the highest quality signal on human adult hippocampal tissue. Similar systematic studies are, therefore, needed to optimize antigen retrieval protocols for each antibody intended to be used on human brain samples.

The immunohistochemistry protocol

Antibody signal validation

The validation of primary and secondary antibodies is essential to assess any biological process using IHC. Moreover, given discrepant results reported in the literature, unambiguous signal validation gains further relevance in the context of AHN studies. Although an antibody is theoretically designed to target a protein of interest in a particular species, some antibodies produce unspecific staining, high background, or artifactual detection of other proteins (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020). Moreover, determining whether an observed signal is indeed specific is not straightforward. Despite inter-species differences, a general recommendation to validate a new antibody in a given species is to compare the signal obtained with that described in rodents (whenever this information is available). In this regard, the subcellular distribution of the signal observed should be, a priori, similar in both species (for instance, a microtubule-associated protein is expected to label cytoplasmic structures). Also, the same cell types are expected to be either positive or negative for that marker in both species. In this respect, morphological criteria can be used to identify cell types. However, evaluation of the co-expression of other markers that have been validated previously is advised whenever possible (Flor-Garcia et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021; Terreros-Roncal et al., 2021). If unexpected cell types appear to show positive staining, further validation with alternative methods (see below) might be required. In particular, in the case of AHN makers, widespread signal is not expected to be observed in non-neurogenic regions of the brain, although there might be exceptions. In this regard, observations of staining with anti-DCX antibodies in non-neurogenic regions have been used to refute the occurrence of human AHN (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2022; Sorrells et al., 2021). This assumption overlooks two important considerations: first, the existence of DCX+ neurons in non-neurogenic regions of the mouse brain is compatible with the occurrence of rodent AHN and there is no evidence supporting the opposite in humans. Second, a recent study revealed that the DCX+ signal observed in the macaque cortex is not only unspecific but also artifactual (Liu et al., 2020). This finding thus calls for caution when interpreting DCX+ signal in non-neurogenic regions of the primate brain (Terreros-Roncal et al., 2022b).

To assess the specificity of a given antibody, distinct strategies, such as the use of synthetic blocking peptides that mimic the antigen recognition domain by antibodies (Liu et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019), can be tested. For instance, the pre-adsorption of an anti-DCX antibody with a specific blocking peptide causes the disappearance of the DCX+ signal by both dot-blot and IHC (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019), thereby confirming the authenticity of the DCX signal detected in the human DG. Strikingly, the incubation of anti-DCX antibodies with hippocampal extracts causes the DCX+ signal to disappear in macaque cortices but not in the hippocampi of this animal (Liu et al., 2020). These results question the specificity of certain anti-DCX antibodies used in previous studies (Sorrells et al., 2018), as they might detect other proteins that potentially share structural properties with DCX in some regions of the primate brain (Liu et al., 2020).