Abstract

Background

Patients with Gaucher disease (GD) have a high risk of fragility fractures. Routine evaluation of bone involvement in these patients includes radiographs and repeated dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). However, osteonecrosis and bone fracture may affect the accuracy of DXA.

Purpose

To assess the utility of DXA and radiographic femoral cortical thickness measurements as predictors of fragility fracture in patients with GD with long-term follow-up (up to 30 years).

Material and Methods

Patients with GD aged ≥16 years with a detailed medical history, at least one bone image (DXA and/or radiographs), and minimum 2 years follow-up were retrospectively identified using three merged UK-based registries (Gaucherite study [enrollment 2015-2017], Clinical Bone Registry [enrollment 2003-2006] and Mortality Registry [enrollment 1993-2019]). Cortical thickness index (CTI) and canal-to-calcar ratio (CCR) were measured by two independent observers; inter-/intra-observer reliability was calculated. The fracture-predictive value of DXA/CTI/CCR and cut-off values were calculated using the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves; statistical differences were assessed using univariable/multivariable analysis.

Results

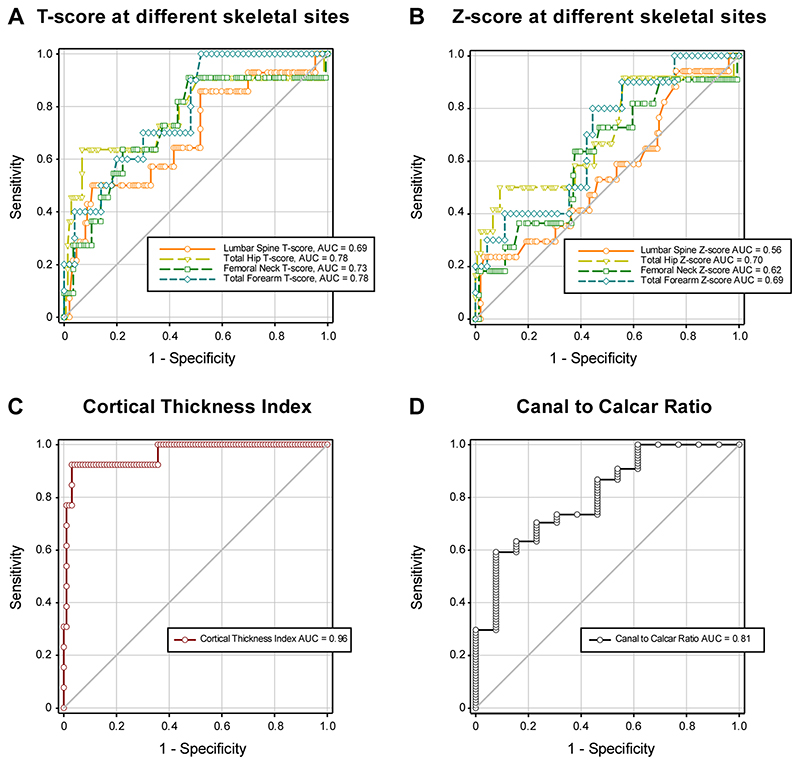

Bone imaging of 247 patients (123M:124F, baseline median age 39 years [IQR 27-50]) was reviewed. The median follow-up period was 11 years [IQR 7-19; range 2-30]. Thirty-five patients had fractures before or at first bone imaging, 23 after first bone imaging, and 189 remained fracture-free. Inter/intra-observer reproducibility for CTI/CCR measurements was substantial (0.96-0.98). In the 212 patients with no baseline fracture, CTI (cut-off ≤ 0.50) predicted future fractures with higher sensitivity and specificity (AUC 0.96 [95% CI 0.84-0.99]; sensitivity/specificity 92%/96%) than DXA T-score at total hip (AUC 0.78 [95% CI 0.51-0.91]; sensitivity/specificity 64%/93%), femoral neck (AUC 0.73 [95% CI 0.50-0.86]; sensitivity/specificity 64%/73%), lumbar spine (AUC 0.69 [95% CI 0.49-0.82]; sensitivity/specificity 57%/63%) and forearm (AUC 0.78 [95% CI 0.59-0.89]; sensitivity/specificity 70%/70%).

Conclusion

Radiographic cortical thickness index ≤ 0.50 was a reliable independent predictor of fracture risk in Gaucher disease.

Introduction

Gaucher disease (GD) is an ultra-rare, autosomal recessive disorder due to impaired lysosomal β-glucocerebrosidase activity. It causes glycosphingolipid accumulation and pathologic activation of monocytes/macrophages mainly in the bone marrow, liver, and spleen (1). GD has protean manifestations and is typically classified into three main types, based on the absence (type 1) or presence of neurological involvement (type 2 and 3) (1).

Bone manifestations are frequent in GD, commonly including bone pain, medullary infarction, osteonecrosis at multiple skeletal sites, Erlenmeyer flask deformity (i.e., metaphyseal flaring), lytic lesions, osteopenia/osteoporosis, and fragility fractures (2). Palliative measures such as splenectomy were the only treatments available until the 1990s. Current therapies include macrophage-targeted enzyme (glucocerebrosidase) replacement and substrate (glucosylceramide) reduction therapy; they improve bone mineral density (BMD) and decrease the frequency of osteonecrosis (1–3).

Assessment of bone involvement in GD requires serial radiography, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), and MRI (2). As in the general population, a DXA Z-score ≤1.0 at the lumbar spine predicts fracture risk in GD type 1 (4–6). However, inappropriate bone mineral density readings may occur in patients with GD with underlying skeletal involvement and delay the timely initiation of bone-strengthening fracture prophylaxis (2, 7, 8).

The cortical thickness index (CTI) and canal-to-calcar ratio (CCR) use radiographs to determine proximal femoral characteristics; they can be used to estimate, respectively, the cortical thinning and the intramedullary canal widening caused by osteoporosis (lower CTI and higher CCR indicate bone loss) (9, 10). CTI is an easy-to-measure, validated tool for assessing the fracture risk in osteoporotic or non-osteoporotic individuals aged ≥ 50 years and in older adults undergoing hemiarthroplasty (11, 12). Since its measurement does not rely on intact femoral head/neck, CTI is unlikely affected by other features of GD such as osteonecrosis and bone fracture where DXA readings may lead to inaccurate findings. We therefore reviewed the medical records and bone imaging of patients with GD who underwent comprehensive imaging-based bone evaluations and recorded the incidence, location, and timing of fragility fractures. To confirm whether CTI represents a useful alternative to DXA for the detection of fracture risk, we compared the ability of CTI to predict fracture in patients with GD with those of DXA measurements (spine, hip, or radius). Our aim was to assess the utility of DXA and radiographic femoral cortical thickness measurements as predictors of fragility fracture in patients with GD with long-term follow-up (up to 30 years).

Material and Methods

Study cohort

A consecutive sampling strategy was used: patients with GD enrolled in the three UK-based registries ([Gaucherite study [Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03240653], enrollment 2015-2017, n=250); Clinical Bone Registry, enrollment 2003-2006, n=100; Mortality Registry, enrollment 1993-2019, n=52], details in Appendix E1) (13, 14), were screened to meet the following eligibility criteria: age ≥16 years; detailed medical history (defined as having complete data on demographic/clinical characteristics; GD characteristics [i.e., GD diagnosis date; known GD-specific treatment status; known splenectomy status]; fracture status, including fracture date); at least one bone image (DXA and/or radiographs); minimum follow-up of 2 years. Duplicate patients’ data were merged into one master case. Exclusion criteria consisted of: age <16 years; incomplete medical history and/or lack of at least one bone image and/or adequate radiographs and/or had features altering the femoral anatomy (i.e., hip replacement/internal fixation; osteonecrosis complicated by subsequent femoral neck fracture/collapse of the joint surface and severe arthritis) that technically prevented the measurement of geometric parameters on both femoral sides (Figure 1). Skeletal survey (pelvis, femoral and spine radiographs) and DXA are part of the agreed investigative protocol for diagnosis and management of patients with GD, irrespective of particular symptoms, enrolled at the UK specialist centers. These protocols prevented systematic loss of data in our study. Epidemiological data from 222 of the participants were previously included in a study describing the Gaucherite cohort enrollment (13) and a separate analysis of global skeletal features of GD (14), whereas in this manuscript we report on the clinical outcome of fragility fracture on a larger patient number, and we include new radiographic measurements.

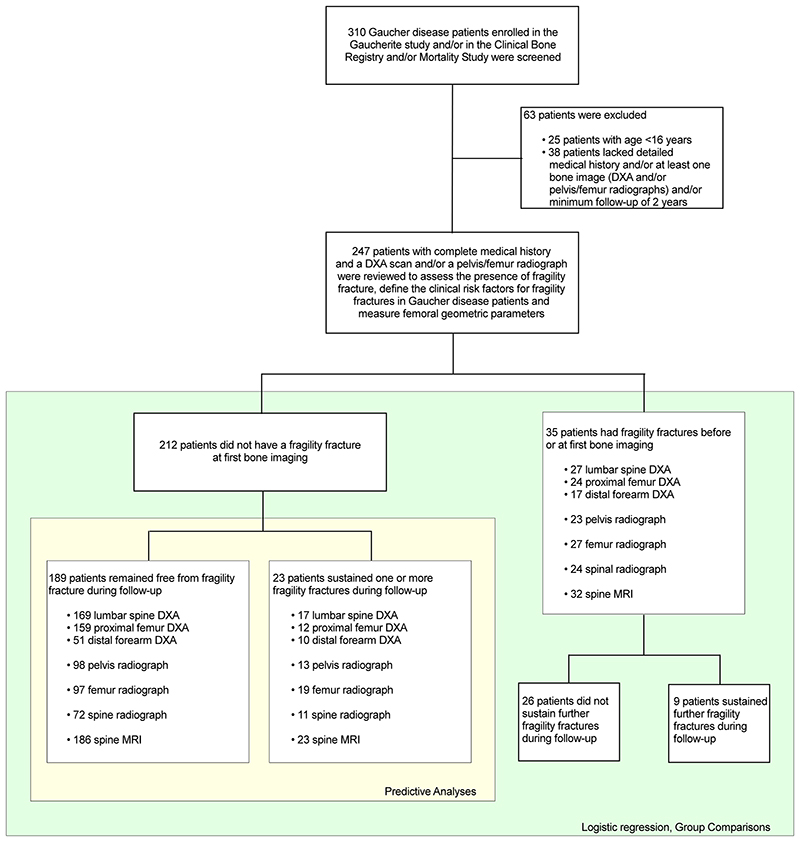

Figure 1. Strobe flow chart shows patient selection.

DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Written informed consent was obtained from every participant; ethical approval from a national ethics review committee (UK National Health Service Research and Development) was obtained. Data from deceased patients was captured and analyzed according to the approved procedure for this group within the Gaucherite project.

Radiographic parameters and inter- and intra-observer reliability

Radiographs available on the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) and those previously converted into digital images were anonymized before review. Digitization used the VIDAR’s DiagnosticPRO Edge film digitizer (VIDAR) for Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) and VIDAR ClinicalExpress software, in compliance with Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) 3.0 standards; DICOM image files were imported in PACS or exported to CD (15).

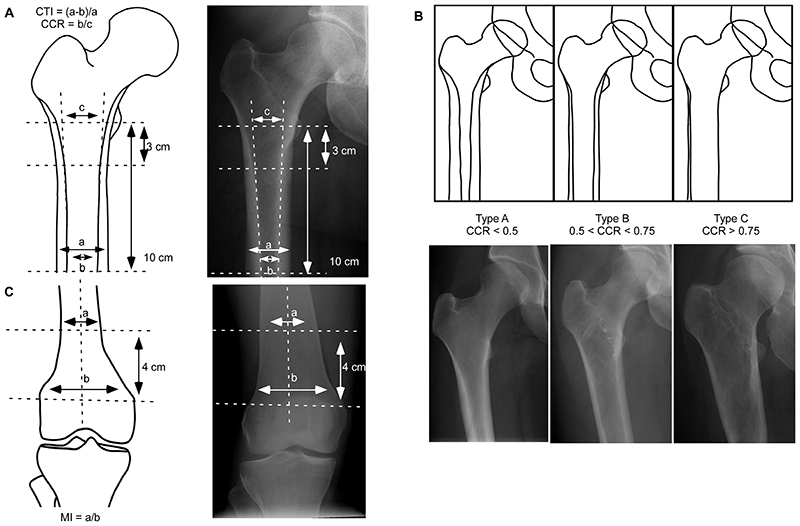

Femoral geometry was measured by an orthopedic surgeon specialist and rheumatologist (HS, with 7 years of experience) and an internal medicine specialist expert in bone disease (SD, with 10 years of experience): as previously described (9), CTI was defined as the ratio of cortical width minus endosteal width to cortical width at a level of 10 cm below the minor trochanter, and the CCR was defined as the ratio between the intramedullary canal isthmus and the calcar isthmus; Figure 2A and Table E1 (online). Based on CCR measurements, femoral morphology was classified corresponding to Dorr type A (CCR<0.50), B (0.50<CCR<0.75) and C (CCR>0.75) (9); Figure 2B and Table E1 (online). Erlenmeyer flask deformity was defined by measuring the metaphyseal index (MI=ratio of the width of diametaphysis 4 cm from the physeal plate divided by the physeal plate width; Figure 2C and Table E1 [online]) (16).

Figure 2. Radiographic measurements.

(A) The CTI is defined as the ratio of cortical width (a) minus endosteal width (b) to cortical width at a level of 10 cm below the minor trochanter. The CCR is defined as the ratio between the intramedullary canal isthmus (b) and the calcar isthmus (c). (B) Dorr classification of the proximal femoral morphology: type A (CCR<0.50) is defined by thick cortices producing a narrow and funnel shape diaphyseal canal, type B (0.50<CCR<0.75) exhibits bone loss proximally and widening of the diaphyseal canal, and type C (CCR>0.75) is characterized by seriously thin cortices resulting in a wide cylindrical shape femoral canal. (C) The metaphyseal index is defined as the ratio of the width of diametaphysis 4 cm from the physeal plate divided by the physeal plate width. Radiographs from (A) a 43-year-old woman with Gaucher disease type 1 and no history of fragility fracture, splenectomy nor osteonecrosis; (B, left panel) and (C) a 29-year-old woman with Gaucher disease type 1 and no history of fragility fracture, splenectomy nor osteonecrosis (right panel); (B, central panel) a 42-year-old woman with Gaucher disease type 1 and prior splenectomy, with no history of fragility fracture nor osteonecrosis; (B, right panel) a 43-year-old woman with Gaucher disease type 1 and history of prior splenectomy, osteonecrosis of the left femoral head, and fragility fracture. CTI=cortical thickness index; CCR=canal to calcar ratio; MI=metaphyseal index.

All measurements were independently performed by the observers (HS and SD) twice, at least four weeks apart without knowledge of previous measurements, BMD, and clinical status. The measurements were done using a DICOM viewer measurement tool. Disagreements were settled by consensus; agreement was quantified with the concordance correlation coefficient. Suspected fragility fractures (defined as a positive history of fracture occurring after minimal trauma; e.g. a fall from standing height or less, or non-identifiable trauma) (17) were verified by medical history review by three consultants in inherited metabolic disorders (TMC, PD, UR; all with >20 years of experience in lysosomal disorders). Targeted evaluation of skeletal imaging (spine MRI, thoracic/lumbar radiographs) was carried by a trained/experienced plain film image analyst specializing in osteoporosis and vertebral fractures (DDGC, with >5 years of experience) and a medical student (OB, in-training) to ensure maximal coverage of subclinical/undiagnosed vertebral fractures.

A detailed description of DXA and other bone disease assessments is provided in Appendix E1.

Statistical analysis

Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) was used to evaluate the reliability of radiographic indices (18); cut-off values for qualitative ratings of agreement: poor (CCC<0.90), moderate (0.90<CCC<0.95), substantial (0.95<CCC<0.99), almost perfect (CCC>0.99) (19). Logistic regression was used to evaluate the impact of clinical risk factors for fractures. Comparison between groups (fracture-free; fracture sustained before or at first bone imaging; fracture sustained after first bone imaging) was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis One-Way analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test, and with Pearson’s chi-squared test. Multivariable analysis was conducted on log2 transformed data: (dependent variables) BMD and radiographic measurements; (independent variables) age, sex, splenectomy, GD-specific treatment, and fracture (fracture-free; fracture sustained before or at first bone imaging; fracture sustained after first bone imaging). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis estimated the sensitivity/specificity, and optimal cut-off values (highest sensitivity/specificity) of DXA/CTI/CCR in predicting fracture risk in patients who did not have fragility fracture at the first bone imaging. The areas subtended by the ROC curves were compared using ROCCOMP. The incidence of fractures and number at risk were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The clinical utility index (CUI), which considers occurrence for case-finding ([CUI+] = sensitivity x positive predictive value), screening ([CUI-] = specificity x negative predictive value) and discriminatory ability, was used to calculate the clinical utility of CTI for fracture prediction in patients without a fracture at baseline (cut-off values: excellent [≥ 0.81], good [≥ 0.64], satisfactory [≥ 0.49], poor [< 0.49]) (20).

The statistical tests were performed using NCSS software (v21.0.2; NCSS, LCC); the null hypothesis was rejected when the p-value was ≤ .05. DC (Biostatistician with >13 years of experience in data science) reviewed the statistical analysis.

Results

Characteristics of study cohort

Of the 310 patients with GD assessed for eligibility, 63 were excluded because did not meet all criteria for inclusion. The final study cohort comprised 247 patients with GD (123M:124F, median age 39 years [ IQR, 27-50]; 227 GD type 1 and 20 GD type 3): 35 (14%) had sustained one/multiple fragility fractures at first bone imaging (9 refractured during follow-up), 23 (9%) sustained one/multiple fragility fractures after the first bone imaging, and 189 (77%) remained fracture-free during follow-up (Table 1 and 2; Figure 1). Baseline DXA and pelvis/hip radiograph were available, respectively, in 228 (115M:113M) and 134 patients (65M:69F). Two-hundred and twenty-six patients (113M:113F) also underwent a follow-up radiograph (n=89) or MRI of the spine (n=216). While we found no difference in the male/female proportion between fracture-free and fracture groups in the subsets of patients with available DXA (P=.25) and pelvis/hip radiographs (P=.39) at baseline, patients with fracture by the time of first DXA (median age 49 [IQR, 39-56]) and pelvis/hip radiograph (median age 49 [40-56]) were older compared with fracture-free patients with baseline DXA (median age 36 [IQR, 27-48]; P<.001) and pelvis/hip radiograph (median age 39 [IQR 25-48]; P=.002). Additional description of the study cohort is provided in Appendix E1.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristic of the study cohort of patients with Gaucher disease by fracture status at the time of baseline imaging.

| Clinical variables | All | Fracture-free | Fracture before or at first bone imaging | Fracture after first bone imaging | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 247 (123M:124F) |

189 (101M:88F) |

35 (13M:22F) |

23 (9M:14F) |

- |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 39 (27 to 50) (n=247) |

34 (25 to 48) (n=189) |

49 (41 to 62) (n=35) |

42 (34 to 57) (n=22) |

<.001 (1≠0)‡ |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 24.1 (21.6 to 27.4) (n=242) |

24.2 (21.6 to 27.6) (n=187) |

24.1 (22.1 to 26.1) (n=33) |

22 (21.3 to 26.7) (n=22) |

.52 |

| MENOPAUSE | |||||

| No | 91 (73%) | 72 (82%) | 10 (45%) | 9 (64%) | .001+ |

| Yes | 33 (27%) | 16 (18%) | 12 (55%) | 5 (36%) | |

| Age at menopause, years, median (IQR) | 45.9 (39.5 to 48.9) (n=27) | 47.7 (37.7 to 52.4) (n=14) | 44.9 (39.3 to 46) (n=9) | 44.4 (33.7 to 51.2) (n=4) | .50 |

| HORMONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY STATUS, N% | |||||

| Untreated | 27 (82%) | 13 (81%) | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) | .48+ |

| Treated | 6 (18%) | 3 (19%) | 3 (25%) | - | |

| HRT therapy length, years, median (IQR) | 7.9 (6.8 to 17.2) | 8.5 (7 to 15.7) | 7.2 (6.1 to 21.6) | - | .83 |

| ALCOHOL INTAKE | |||||

| < 14 units/week | 211 (85%) | 163 (86%) | 30 (86%) | 18 (78%) | .59+ |

| ≥ 14 units/week | 36 (15%) | 26 (14%) | 5 (14%) | 5 (22%) | |

| SMOKING STATUS | |||||

| Non-smoker | 163 (66%) | 123 (65%) | 25 (71%) | 15 (66%) | .78+ |

| Ex-smoker | 40 (16%) | 33 (17.5%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Current smoker | 44 (18%) | 33 (17.5%) | 7 (20%) | 4 (17%) | |

Continuous variables presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables presented as number (%). Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA test;

Dunn’s post hoc test (0=fracture-free; 1= fracture sustained before or at first bone imaging; 2=fracture sustained after first bone imaging);

Chi-square test; #Mann-Whitney test. Note: denominators for the “menopause” category are only female patients.

Table 2. Disease characteristic of the study cohort of patients with Gaucher disease by fracture status at the time of baseline imaging.

| Clinical variables | All | Fracture-free | Fracture before or at first bone imaging | fFacture after first bone imaging | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENZYME REPLACEMENT THERAPY/SUBSTRATE REDUCTION THERAPY STATUS, N % | |||||

| N | 247 (123M:124F) |

189 (101M:88F) |

35 (13M:22F) |

23 (9M:14F) |

- |

| GENOTYPE, N % | - | ||||

| Homozygous N370S/N370S | 39 (16%) | 34 (18%) | 3 (8.5%) | 2 (9%) | |

| Homozygous L444P/L444P | 16 (6%) | 9 (5%) | 3 (8.5%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Homozygous other/other | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | - | 1 (4.5%) | |

| Heterozygous N370S/L444P | 41 (17%) | 30 (16%) | 8 (23%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Heterozygous N370S/other | 100 (40%) | 79 (42%) | 13 (37%) | 8 (35%) | |

| Heterozygous L444P/other | 19 (8%) | 13 (7%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Heterozygous other/other | 28 (11%) | 21 (11%) | 6 (17%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS | |||||

| Type of GD, n % | |||||

| Type 1 | 227 (92%) | 177 (94%) | 31 (89%) | 19 (83%) | .14+ |

| Type 3 | 20 (8%) | 12 (6%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Age at disease presentation, years, median (IQR) | 16.7 (5.7 to 33.8) (n=243) |

17.9 (6.1 to 33.8) (n=187) |

13.9 (5.3 to 34.5) (n=33) |

13.7 (3.4 to 35.2) (n=23) |

.71 |

| SPLENECTOMY STATUS, N % | |||||

| Intact spleen | 178 (72%) | 150 (79%) | 18 (51%) | 10 (43%) | <.001 + |

| Splenectomy | 69 (28%) | 39 (21%) | 17 (49%) | 13 (57%) | |

| Age at splenectomy, years, median (IQR) | 18.5 (7.9 to 27) (n=69) |

24.9 (11.6 to 35.2) (n=39) |

16 (5.9 to 25.4) (n=17) |

11.7 (5.8 to 219) (n=13) |

.09 |

| ENZYME REPLACEMENT THERAPY/SUBSTRATE REDUCTION THERAPY STATUS, N % | |||||

| Untreated | 104 (42%) | 73 (39%) | 16 (46%) | 15 (65%) | .04 |

| Treated | 143 (58%) | 116 (61%) | 19 (54%) | 8 (35%) | |

| ERT/SRT treatment length, years, median (IQR) | 9 (3.5 to 14.8) | 9.2 (3.3 to 14.1) | 7.5 (3.4 to 14.8) | 10.9 (5.4 to 16.2) | .58 |

| AVERAGE ERT DOSE, U/KG/2WK | |||||

| ≤30 U/kg/2wk | 79 (57%) | 60 (53%) | 14 (74%) | 5 (62.5%) | .07+ |

| >30 U/kg/2wk | 34 (24%) | 32 (28%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Missing | 27 (19%) | 21 (19%) | 4 (21%) | 2 (25%) | - |

| BONE TREATMENT STATUS, N % | |||||

| Untreated | 186 (75%) | 148 (78%) | 21 (60%) | 17 (74%) | .07+ |

| Treated | 61 (25%) | 41 (22%) | 14 (40%) | 6 (26%) | |

| Bone treatment length, years, median (IQR) | 4.7 (2.2 to 8.1) | 5.0 (2.2 to 8.4) | 4.6 (1.7 to 6.7) | 3.4 (2.4 to 14.9) | .30 |

| BONE DISEASE | |||||

| Age at first fracture, years, median (IQR) | 46.2 (30.3 to 61.02) (n=58) |

- | 44.7 (29.2 to 58.7) (n=35) |

48.3 (34.6 to 61.9) (n=23) |

.37# |

| BONE INFARCTION | |||||

| Absence of osteonecrosis | 124 (50%) | 110 (58%) | 10 (29%) | 4 (17%) | <.001 + |

| Presence of osteonecrosis | 123 (50%) | 79 (42%) | 25 (71%) | 19 (83%) | |

| MODELING DEFORMITY | |||||

| Absence of Erlenmeyer flask | 55 (38%) | 40 (41%) | 6 (22%) | 9 (47%) | .14+ |

| Presence of Erlenmeyer flask | 88 (62%) | 57 (59%) | 21 (78%) | 10 (53%) | |

| DEGENERATIVE DISEASE | |||||

| Absence of osteoarthritis hip | 158 (64%) | 124 (66%) | 20 (57%) | 14 (61%) | .60+ |

| Presence of osteoarthritis hip | 89 (36%) | 65 (34%) | 15 (43%) | 9 (39%) | |

| Absence of osteoarthritis knee | 144 (58%) | 122 (65%) | 12 (34%) | 10 (43%) | .001+ |

| Presence of osteoarthritis knee | 103 (42%) | 67 (35%) | 23 (66%) | 13 (57%) | |

| ORTHOPEDIC PROCEDURE | |||||

| Absence of hip replacement | 215 (87%) | 173 (92%) | 26 (74%) | 16 (70%) | .001 + |

| Presence of hip replacement | 32 (13%) | 16 (8%) | 9 (26%) | 7 (30%) | |

| Absence of knee replacement | 245 (99%) | 187 (99%) | 35 (100%) | 23 (100%) | .73+ |

| Presence of knee replacement | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | - | - | |

| BONE PAIN | |||||

| Yes | 101 (46%) | 73 (43%) | 15 (45%) | 13 (68%) | .12+ |

| No | 119 (54%) | 95 (57%) | 18 (55%) | 6 (32%) | |

Continuous variables presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables presented as number (%). Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA test;

Chi-square test; #Mann-Whitney test.

Risk factors for fragility fracture

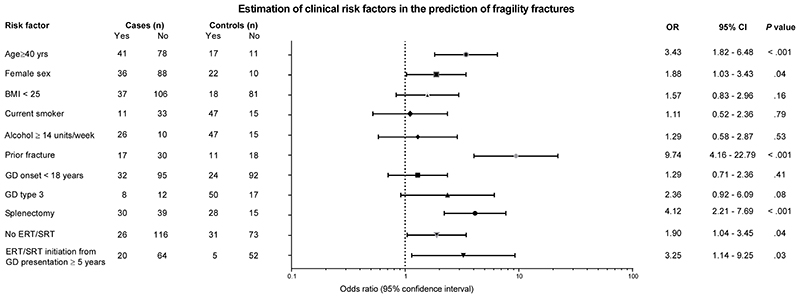

Putative risk factors for fragility fracture were investigated by logistic regression (Figure 3). The following characteristics were associated with fracture risk: age ≥40 years (OR 3.43 [95% CI 1.82-6.48], P=.001), female sex (OR 1.88 [95% CI 1.03-3.43], P=.04), previous fragility fracture (OR 9.74 [95% CI 4.16-22.79], P<.001), splenectomy (OR 4.12 [95% CI 2.21-7.69], P<.001), lack of exposure to GD-specific therapies (OR 1.89 [95% CI 1.4-3.44], P=.04), and > 5 years interval between presentation of GD to starting treatment (OR 3.25 [95% CI 1.14-9.25], P=.03).

Figure 3. Clinical risk factors for fractures in patients with Gaucher disease.

In the overall study sample (123M:124F, median age 39 years [IQR 27-50]), logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between fragility fracture and potential risk factors. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence interval. BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; ERT=enzyme replacement therapy; GD=Gaucher disease; IQR=interquartile range; OR=odds ratio; SRT=substrate reduction therapy.

DXA findings

When compared with those without fracture, patients who sustained fragility fractures during follow-up had lower BMD and T-score at lumbar spine (median BMD 1.0 [IQR, 0.9 to 1.1)] and 0.9 [IQR, 0.8 to 1.1], P=.048; median T-score -0.8 [IQR, -1.6 to 0.3] and -1.7 [IQR, -2.7 to -0.7], P=.04), total hip (median BMD 0.9 [IQR, 0.9 to 1.1] and 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9), P=.002; median T-score -0.3 [IQR, -0.9 to 0.6] and -1.6 [IQR, -2.3 to -0.5], P=.007), femoral neck (median BMD 0.8 [IQR, 0.8 to 1.0] and 0.7 [IQR, 0.6 to 0.8], P=.02; median T-score -0.5 [IQR, -1.2 to 0.4] and -1.4 [IQR, -2.2 to -0.7], P=.047), and total forearm (median BMD 0.6 [IQR, 0.5 to 0.6] and 0.5 [IQR, 0.4 to 0.6], P=.048; median T-score -0.9 [IQR, -1.7 to 0.3] and -2.0 [IQR, -3.1 to -1.0], P=.007) (Figure E2A-D and Table E1, both online; Kruskal-Wallis). However, when imputing BMD measurements in multivariable models using fracture group, age (40 < vs. ≥ 40 years), sex, splenectomy, and Gaucher-specific treatment as independent variables, no BMD measurement emerged as significant for fragility fracture (P values range=0.09-0.99); on the contrary, we found interactions between fracture group with splenectomy and Gaucher-specific treatment for lumbar spine and total hip BMD (P=.01 and P=.03, respectively), and between fracture group with age and splenectomy for total forearm (P=.04), indicating that multiple factors influence BMD in GD and that BMD was not linearly associated with fragility fracture in this condition (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable analysis of variance of bone mineral density, cortical thickness index and canal to calcar ratio by clinical risk factors.

| Clinical risk factors | BMD Spine | BMD Total Hip | BMD Femoral Neck | BMD Total Forearm | CTI | CCR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-Ratio | P value | F-Ratio | P value | F-Ratio | P value | F-Ratio | P value | F-Ratio | P value | F-Ratio | P value | |

| (A) Fracture | 2.45 | .09 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.42 | .66 | 0.00 | >.99 | 4.80 | .01 | 3.77 | .03 |

| (B) Sex | 0.60 | .44 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| (C) Age < or ≥ 40 years | 2.04 | .16 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 1.62 | .21 | 0.55 | .46 |

| (D) Splenectomy | 1.94 | .17 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.33 | .57 | 0.07 | .80 |

| (E) Gaucher-specific treatment | 1.08 | .30 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| AB | 0.23 | .79 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.45 | .64 | 3.29 | .05 | 0.08 | .92 | 0.39 | .68 |

| AC | 0.62 | .54 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.67 | .52 | 0.00 | >.99 | 1.69 | .19 | 0.55 | .58 |

| AD | 0.76 | .47 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 3.57 | .04 | 0.50 | .61 | 0.20 | .82 |

| AE | 0.54 | .58 | 0.00 | >.99 | 2.27 | .11 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.63 | .53 | 0.51 | .60 |

| ABC | 0.65 | .52 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 3.28 | .05 | 0.04 | .96 | 0.01 | .99 |

| ABD | 1.46 | .24 | 2.18 | .12 | 1.40 | .25 | 1.12 | .34 | 1.95 | .15 | 0.67 | .52 |

| ABE | 0.60 | .55 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.04 | .96 | 0.14 | .87 | 0.18 | .84 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ACD | 0.91 | .41 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 3.71 | .04 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ACE | 0.55 | .58 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.05 | .95 | 0.01 | >.99 |

| ADE | 4.68 | .01 | 3.47 | .03 | 2.84 | .06 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.51 | .60 | 0.96 | .39 |

| ABCD | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ABCE | 0.01 | .99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ABDE | 0.20 | .82 | 0.23 | .80 | 0.40 | .67 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ACDE | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

| ABCDE | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 | 0.00 | >.99 |

BMD=bone mineral density; CCR=canal to calcar ratio; CTI=cortical thickness index.

Intra- and inter-observer agreement

One-hundred and thirty-five patients (65M:69F) had adequate hip radiographs with at least one femur available for analysis. For both CTI and CCR measurements, CCC for intra- and inter-observer agreement (Table E2 [online]) was 0.96-0.98 (substantial).

Femoral radiographic parameters

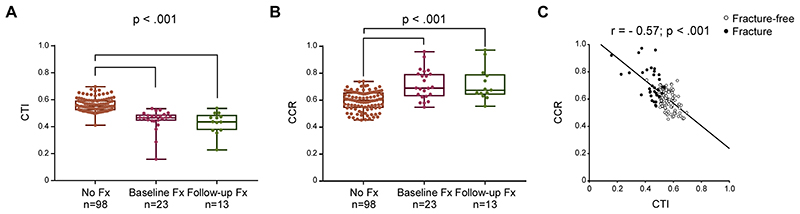

The proximal femurs were categorized into shapes (Dorr type A [13/134], B [108/134], C [13/134]): none of the patients in the fractured group had a Dorr type A (Table E1 [online]). In the overall study sample the median CTI was 0.53 (IQR 0.50-0.59) and lower (P<.001) in those with fracture at baseline (median CTI 0.47 [IQR, 0.44-0.49]) and during follow-up (median CTI 0.44 [0.37-0.49]) when compared with patients without fractures (median CTI 0.55 [IQR, 0.52-0.59]); Figure 4A. The median CCR was 0.63 (IQR, 0.56-0.67) in the overall study sample and was greater (P<.001) in those with fracture at baseline (median CCR 0.69 ([IQR, 0.63-0.79]) and during follow-up (median CCR 0.68 ([IQR, 0.64-0.79]) compared with those who remained fracture-free (median CCR 0.60 [IQR, 0.54 to 0.66]); Figure 4B. There was a negative correlation between CTI and CCR (r=-0.57, P<.001); Figure 4C. When imputing in multivariable models age (40< vs. ≥ 40 years), sex, splenectomy, Gaucher-specific treatment as additional independent variables, CTI and CCR was significant only for fragility fracture (P=.01 and P=.03, respectively; Table 3), thereby confirming that CTI and CCR were associated principally with fragility fracture without confounding effects.

Figure 4. Cortical thickness index and canal to calcar ratio in patients with Gaucher disease.

Within the whole cohort of 247 patients studied, 134 patients had adequate hip radiographs available for analysis (98 [50M:48F; median age 38 years, IQR 25-48] who remained fracture-free during follow-up; 23 [11M:12F; median age 50 years, IQR 40-56] with fracture before or at first bone imaging; and 13 [4M:9F; median age 40 years, IQR 22-53] who sustained a fracture after first bone imaging). Analysis of differences between groups indicated that patients with GD who sustained fragility fractures before or at first bone imaging (Baseline Fx) or after the first bone imaging (Follow-up Fx) had a smaller (A) CTI (Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA on Ranks test: P<.001) and larger (B) CCR (Kruskal-Wallis One-Way ANOVA on Ranks test: P<.001) compared with patient who remained free from fracture (No Fx). Boxes include the data between first and third quartiles, the central bar indicates the median and the whiskers show minimum and maximum values. The dots represent all patients. In the overall study sample, the cortical thickness index was negatively correlated to (C) canal to calcar ratio (r=-0.57, P<.001). The correlation between continuous variables was assessed with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. (o) Fracture-free; (•) Fracture. CCR=canal to calcar ratio; CTI=cortical thickness index; Fx=fracture; GD=Gaucher disease; IQR=interquartile range.

Fragility fracture prediction

ROC curve analyses were done in patients without a fracture at baseline. The AUC predicting fracture at any skeletal site for DXA T-score (Figure 5A) was 0.69 ([95% CI 0.49-0.82]; sensitivity/specificity 57%/63%; cut-off value -1.20) for lumbar spine; 0.78 ([95% CI 0.51-0.91]; sensitivity/specificity 64%/93%; cut-off value -1.60) for total hip; 0.73 ([95% CI 0.50-0.86]; sensitivity/specificity 64%/73%; cut-off value -1.20) for femoral neck; and 0.78 ([95% CI 0.59-0.89]; sensitivity/specificity 70%/70%; cut-off value -1.50) for forearm. Similar results are shown for the Z-scores at relevant sites (Figure 5B). In contrast, the CTI showed excellent prediction of future fracture at any skeletal site (Figure 5C), with an AUC of 0.96 [95% CI 0.84-0.99; sensitivity/specificity 92%/97%; cut-off value ≤0.50)]. The CCR gave an AUC of 0.81 [95% CI 0.64-0.90; sensitivity/specificity 62%/85%; cut-off value ≥0.68)]; Figure 5D.

Figure 5. Performance of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, cortical thickness index and canal to calcar ratio as biomarkers of fragility fracture in patients with Gaucher disease.

In patients with Gaucher disease with no fracture at baseline, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to assess the performance in the prediction of future fragility fractures of (A) T-score at lumbar spine (n=149 [82M:67F] fracture-free; n=14 [6M:8F] follow-up fracture), total hip (n=147 [82M:65F] fracture-free; n=11 [5M:6F] follow-up fracture), femoral neck (n=144 [80M:64F] fracture-free; n=11 [5M:6F] follow-up fracture), and total forearm (n=50 [21M:29F] fracture-free; n=10 [4M:6F] follow-up fracture); and Z-score at lumbar spine (n=155 [84M:71F] fracture-free; n=17 [7M:10F] follow-up fracture), total hip (n=150 [82M:68F] fracture-free; n=12 [6M:6F] follow-up fracture), femoral neck (n=150 [86M:68F] fracture-free; n=11 [5M:6F] follow-up fracture), and total forearm (n=45 [18M:27F] fracture-free; n=10 [4M:6F] follow-up fracture); and (C and D) CTI and CCR (n=98 [50M:48F] fracture-free during follow-up; n=13 [4M:9F] follow-up fracture). AUC=area under the curve; CCR=canal to calcar ratio; CTI=cortical thickness index; IQR=interquartile range.

We further compared the performance of ROC curves in predicting future fracture at any skeletal site in a subset of patients that did not have a fracture at baseline and for whom DXA and radiographic parameters were available (paired analysis with pairwise deletion). Comparison of the ROC curves showed that femoral neck T-score (most commonly used in clinical practice as part of the FRAX Tool) (21) had lower fracture prediction (AUC=0.71; P=.054) than CTI (AUC=0.96). The same was seen for DXA T-score at lumbar spine (AUC=0.62; P=.045) and total forearm (AUC= 0.69; P=.005), and Z-score from all skeletal sites (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for cortical thickness index and T-and Z-scores at different skeletal sites.

| TEST VARIABLE 1 | TEST VARIABLE 2 | ROC CURVE AREA COMPARISON |

|---|---|---|

|

CORTICAL THICKNESS INDEX Sample Size 0=77; Sample Size 1 = 10 AUC=0.96; SE=0.04; 95% CI=0.89 to 1.03 |

LUMBAR SPINE T-SCORE Sample Size 0=70; Sample Size 1=8 AUC=0.62; SE=0.12; 95% CI=0.39 to 0.86 |

CTI vs. LUMBAR SPINE T-SCORE Area Difference=0.34; SE=0.12 95% CI=0.10 to 0.57; P=.005 |

|

LUMBAR SPINE Z-SCORE Sample Size 0=70; Sample Size 1=9 AUC=0.58; SE=0.11; 95% CI=0.37 to 0.80 |

CTI vs. LUMBAR SPINE Z-SCORE Area Difference=0.38; SE=0.10 95% CI=0.18 to 0.58; P=.001 |

|

|

TOTAL HIP T-SCORE Sample Size 0=69; Sample Size 1=7 AUC=0.73; SE=0.14; 95% CI=0.46 to 1.00 |

CTI vs. TOTAL HIP Z-SCORE Area Difference=0.23; SE=0.1495% 95% CI: -0.03 to 0.49; P=.09 |

|

|

TOTAL HIP Z-SCORE Sample Size 0: 68; Sample Size 1 =8 AUC=0.68; SE=0.13; 95% CI=0.42 to 0.93 |

CTI vs. TOTAL HIP Z-SCORE Area Difference=0.28; SE=0.12 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.52; P=.02 |

|

|

FEMORAL NECK T-SCORE Sample Size 0=69; Sample Size=1=7 AUC=0.71; SE=0.13; 95% CI=0.45 to 0.96 |

CTI vs. FEMORAL NECK T-SCORE Area Difference=0.25; SE=0.13 95% CI: -0.004 to 0.51; P=.05 |

|

|

FEMORAL NECK Z-SCORE Sample Size 0=68; Sample Size 1=8 AUC=0.63; SE=0.13; 95% CI=0.38 to 0.87 |

CTI vs. FEMORAL NECK Z-SCORE Area Difference=0.33; SE=0.11 95% CI: 0.11 to 0.56; P=.004 |

|

|

TOTAL FOREAM T-SCORE Sample Size 0=35; Sample Size 1=7 AUC=0.69; SE=0.12; 95% CI=0.47 to 0.92 |

CTI vs. TOTAL FOREAM T-SCORE Area Difference=0.30; SE=0.09 95% CI=0.08 to 0.45; P=.005 |

|

|

TOTAL FOREAM Z-SCORE Sample Size 0=30; Sample Size 1=7 AUC=0.66; SE=0.13; 95% CI=0.40 to 0.92 |

CTI vs. TOTAL FOREARM Z-SCORE Area Difference=0.30; SE=0.09 95% CI=0.11 to 0.48; P=.002 |

Paired Analysis with pairwise deletion to compare receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for cortical thickness index and T- and Z-score at different skeletal sites. Sample size 0 refers to patients with Gaucher disease who remained fracture-free during follow-up; Sample size 1= refers to patients with Gaucher disease who sustained a fragility fracture after the first bone imaging. AUC=area under the under the curve; CI=confidence interval; CTI=cortical thickness index; SE=standard error.

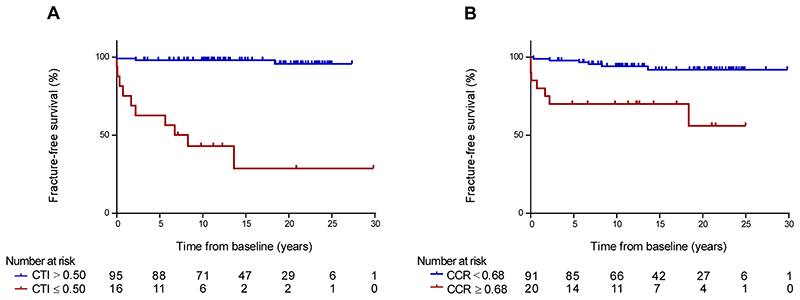

Log-rank analysis of Kaplan-Meier survival in a subset of 111 patients with adequate hip radiographs and no fracture at first bone imaging, showed better fracture-free survival in patients with CTI at baseline above 0.50 (HR 0.04 [95% CI 0.01-0.21], log-rank P<.001; Figure 6A) and with CCR at baseline below 0.68 (HR 0.15 [95% CI 0.03-0.69], log-rank P<.001; Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Fracture-free survival analysis of cortical thickness index and canal to calcar ratio in patients with Gaucher disease.

Within the 212 patients with Gaucher disease who were fracture-free at baseline, 111 patients had adequate hip radiographs available for fracture-free survival analysis (98 [50M:48F; median age 38 years, IQR 25-48] remained fracture-free during follow-up and 13 [4M:9F; median age 40 years, IQR 22-53] who sustained a fracture after first bone imaging). (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of fracture-free survival of patients with Gaucher disease with CTI at baseline below and above 0.50 (log-rank test P<.001). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of fracture-free survival of patients with Gaucher disease with CCR at baseline below and above 0.68 (log-rank test P<.001). CCR=canal to calcar ratio; CTI=cortical thickness index; IQR=interquartile range.

To explore the qualitative and quantitative accuracy of CTI in predicting which patients with GD will have fragility fractures, we calculated its clinical utility: this confirmed excellent predictive performance of the CTI (clinical utility index=96.4) (20).

Discussion

Prevention of fragility fractures is an unmet need in patients with GD (2). DXA is currently recommended for estimating the BMD in patients with GD, despite potential pitfalls associated with previous fractures and/or the coexistence of osteonecrosis, where osteosclerosis interferes with the measurement (2, 7, 8, 22, 23); however, the utility of other radiographic parameters to assess the bone status is unknown. Our study showed that femoral thinning (CTI ≤ 0.50) occurred in patients with GD with fragility fractures (P=.01); as a strong predictor (AUC 0.96) of this complication, it performed better than DXA carried out at various sites (T-score at total hip [AUC 0.78], femoral neck [AUC 0.73], lumbar spine [AUC 0.69], and forearm [AUC 0.78].

Here we provide a detailed characterization of the extent of the bone manifestations (incidence, location, and timing of fragility fractures) in a substantial cohort of patients with GD with long-term follow-up. Fragility and vertebral fractures, either incident or subsequent, were evident in 24% and 16% of the patients, respectively; and well within the range of previously reported prevalence (4, 14, 24). As in the general population, in GD we confirm that age, female sex and previous fragility fracture were the strongest risk factors for fractures (25); other risk factors included prior splenectomy, absence of Gaucher-specific therapies and delayed initiation of treatment, as seen in a large population of Gaucher patients enrolled in the International Collaborative Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry (ICGG) (24).

We additionally evaluated the relative ability of DXA and CTI/CCR measurements to predict the fracture in GD. Commensurate with findings reported from the ICCG Registry (4), we found that 60% of patients had osteopenia or osteoporosis as defined by DXA. The accuracy of DXA-measurements in predicting osteoporotic fractures resembled that reported in the general population, with an AUC derived from the total hip (AUC 0.78) greater than that from femoral neck (0.73) or lumbar spine (AUC 0.69) (5, 6). Notably in the forearm, which best reflects cortical bone mineralization, the performance of DXA was similar to that in the total hip - AUC values fell short of those expected of an informative clinical marker (26). Discordance in the accuracy of DXA at different sites may simply reflect inaccurate findings in the DXA reading (due to osteonecrosis and bone fracture) and/or a different pattern of bone under-mineralization in GD, affecting for example, cortical rather than trabecular bone. We therefore recommend caution in the use of bone density measurements in GD, and that if DXA is the only available option, then it is best done at multiple sites for predicting the risk of fracture.

Given the disappointing utility of DXA in GD, we investigated the value of the CTI and other simple geometrical parameters obtained from radiographs for predicting future fracture. CTI is known to correlate with bone quality and to predict complications in the general population (9, 10). We found that thinner femoral cortices and adverse Dorr type were far stronger predictors of fragility fractures than DXA-derived measurements in GD.

Key strengths of the work include the duration of the observation period (up to 30 years); the wide range and completeness of data recorded that allows robust statistical analysis; and the systematic approach used to identify incidental fractures. This latter point is particularly relevant to comparisons with other registry studies, where the data submitted depend on the cooperation of individual investigators: lack of clarity in the definition of bone events such as fracture and variation in the assessment as well as data fragmentation reduce the value of such studies (4, 27, 28).

Our study also has some limitations. First, we used a retrospective/opportunistic design. This design allowed us to capitalize on all available data extracted from real-world medical records. However, a potential bias may be introduced by uneven distribution of imaging among patients. In particular, those without symptoms may be less likely to undergo radiological examination and thus be underrepresented in our study cohort: however, patients in the Gaucherite and mortality cohorts were under the care of specialist centers with established national protocols for regular imaging and review. Second, our study included only a few subsequent fractures, which prevented a meaningful sub-group analysis of risk factors for spine compared with appendicular fractures and the different duration of follow-up among patients. Third, there is a possible underestimation of the prevalence of vertebral fracture in those patients who missed a thoracolumbar radiograph and in whom only a lumbar spine MRI was available. Fourth, not all the information about medication for osteoporosis was available. Finally, we recognize that dramatic changes affecting the anatomy of the femur (i.e., after hip surgery or severe osteonecrosis) preclude determination of the femoral geometric parameters since they rely on the ability to construct straight lines along the axes of the femoral shafts.

In conclusion, this study shows that a CTI ≤ 0.50 has optimal accuracy in predicting the bone health status and the risk of fracture in Gaucher disease (sensitivity of 92%; specificity of 96%). Since cortical thickness is readily measured on standard Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) workstations, we propose its routine use in clinical practice to evaluate the fracture risk in patients with this disease. Studies are now warranted to determine if patients with GD and thin femoral cortices would benefit from therapeutic intervention with bone-active treatments as a rigorously documented clinical management stratagem. Finally, we ask if CTI can be used to monitor disease progression and/or response to treatment in Gaucher patients worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Summary statement.

Reduced femoral cortical thickness index predicts future fragility fractures in Gaucher disease better than dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Key results.

-

▪

This retrospective cohort study in 247 patients with Gaucher disease with a median followup period of 11 years (range: 2-30) showed that femoral cortical thinning (cortical thickness index [CTI] ≤ 0.50) predicted fragility fractures (P=.01) independently of age, sex, fracture status, splenectomy, and delayed enzyme replacement therapy.

-

▪

CTI was a stronger predictor of future fractures (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC] 0.96) than dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, performed at various sites (T-score at total hip [AUC 0.78], femoral neck [AUC 0.73], forearm [AUC 0.78], and spine [AUC 0.69]).

Acknowledgments

We thank clinicians, specialist nurses and support staff for their continued assistance, the Picture Archiving and Communication System teams that facilitated downloading of radiological images.

Funding

This work was supported by a Stratified Medicine Program award, Gaucherite: MR/K015338/1 from the UK Medical Research Council (2013-2019) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (grant number IS-BRC-1215-20014) that in part supported SD and KP. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

List of abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- BMD

bone mineral density

- CCC

Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient

- CCR

canal to calcar ratio

- CTI

cortical thickness index

- DXA

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- GD

Gaucher disease

- OR

odds ratio

- ROC

receiver-operating characteristic

Footnotes

Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03240653

Author contributions

SD, KEP, PD and TMC conceived and designed the study. Data were collected by SD, HS, DDGC, OB, KP, UR, FJ, TMC, PD and KEP, analyzed by SD, HS, DDGC and OB, and interpreted by all authors. DC reviewed the statistical analysis. SD and HS created the figures. SD and KEP verified the underlying data. All other authors contributed to the implementation of the study and to the preparation of the report. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

SD reports speaker fees from Takeda and travel support from Sanofi Genzyme and Takeda outside of the submitted work; and has been recently employed by Chiesi (after the submission of this manuscript). PD reports research grant support from Sanofi Genzyme and Takeda; speaker fee from Sanofi Genzyme and Takeda outside of the submitted work; and is a member of European Board of the International Collaborative Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry (ICGG), which is sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme, and of the Gaucher Outcome Survey Board Member, which is sponsored by Takeda. TMC reports research grant support from Sanofi and Takeda; consulting and speaker fees from Avrobio, Sanofi Genzyme, and Takeda; travel support from Sanofi Genzyme; and advisory board fees from Sanofi Genzyme outside of the submitted work. UR reports research grant support from Amicus, Intrabio, and Takeda; consulting and speaker fees, and travel support from Amicus, Sanofi Genzyme, and Takeda outside of the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

MRC Gaucherite Consortium:

TM Cox, FM Platt, S Banka, A Chakrapani, PB Deegan, T Geberhiwot, DA Hughes, S Jones, RH Lachmann, S Santra, R Sharma, and A Vellodi

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are held by the University of Cambridge under a Medical Research Council approved Data Management Policy. Restrictions apply and data are not publicly available: applications from bona fide organizations will be considered by the University of Cambridge and clinical governance of Cambridge University NHS Foundation Trust Hospitals and subject to approval by the Gaucherite Consortium Management Committee. Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

References

- 1.Roh J, Subramanian S, Weinreb NJ, Kartha RV. Gaucher disease - more than just a rare lipid storage disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2022;100:499–518. doi: 10.1007/s00109-021-02174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes D, Mikosch P, Belmatoug N, et al. Gaucher Disease in Bone: From Pathophysiology to Practice. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:996–1013. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenstrup RJ, Kacena KA, Kaplan P, et al. Effect of enzyme replacement therapy with imiglucerase on BMD in type 1 Gaucher disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:119–126. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Hangartner T, Weinreb NJ, Taylor JS, Mistry PK. Risk factors for fractures and avascular osteonecrosis in type 1 Gaucher disease: a study from the International Collaborative Gaucher Group (ICGG) Gaucher Registry. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1839–1848. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leslie WD, Tsang JF, Caetano PA, Lix LM. Effectiveness of bone density measurement for predicting osteoporotic fractures in clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:77–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie WD, Lix LM. Comparison between various fracture risk assessment tools. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox TM, Aerts JM, Belmatoug N, et al. Management of non-neuronopathic Gaucher disease with special reference to pregnancy, splenectomy, bisphosphonate therapy, use of biomarkers and bone disease monitoring. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:319–336. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0779-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drelichman G, Fernandez EN, Basack N, et al. Skeletal involvement in Gaucher disease: An observational multicenter study of prognostic factors in the Argentine Gaucher disease patients. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:E448–E453. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorr LD, Faugere MC, Mackel AM, Gruen TA, Bognar B, Malluche HH. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone. 1993;14:231–242. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sah AP, Thornhill TS, LeBoff MS, Glowacki J. Correlation of plain radiographic indices of the hip with quantitative bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0348-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nash W, Harris A. The Dorr type and cortical thickness index of the proximal femur for predicting peri-operative complications during hemiarthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2014;22:92–95. doi: 10.1177/230949901402200123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen BN, Hoshino H, Togawa D, Matsuyama Y. Cortical Thickness Index of the Proximal Femur: A Radiographic Parameter for Preliminary Assessment of Bone Mineral Density and Osteoporosis Status in the Age 50 Years and Over Population. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018;10:149–156. doi: 10.4055/cios.2018.10.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Amore S, Page K, Donald A, et al. In-depth phenotyping for clinical stratification of Gaucher disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:431. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-02034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deegan PB, Pavlova E, Tindall J, et al. Osseous manifestations of adult Gaucher disease in the era of enzyme replacement therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:52–60. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182057be4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gitlin JN, Narayan AK, Mitchell CA, et al. A comparative study of conventional mammography film interpretations with soft copy readings of the same examinations. J Digit Imaging. 2007;20:42–52. doi: 10.1007/s10278-006-1046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter A, Rajan PS, Deegan P, Cox TM, Bearcroft P. Quantifying the Erlenmeyer flask deformity. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:905–909. doi: 10.1259/bjr/33890893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonjour JP, Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Importance of preclinical studies in the development of drugs for treatment of osteoporosis: a review related to the 1998 WHO guidelines. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:379–393. doi: 10.1007/s001980050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45:255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride GB. A proposal for strength-of-agreement criteria for Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient. National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research (NIWA); [Accessed June 1, 2021]. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell AJ. Sensitivity x PPV is a recognized test called the clinical utility index (CUI+) Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:251–252. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link TM. Osteoporosis imaging: state of the art and advanced imaging. Radiology. 2012;263:3–17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biegstraaten M, Cox TM, Belmatoug N, et al. Management goals for type 1 Gaucher disease: an expert consensus document from the European working group on Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2018;68:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deegan P, Khan A, Camelo JS, Jr, Batista JL, Weinreb N. The International Collaborative Gaucher Group GRAF (Gaucher Risk Assessment for Fracture) score: a composite risk score for assessing adult fracture risk in imiglucerase-treated Gaucher disease type 1 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:431. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01656-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan J, Upadhye S, Worster A. Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. CJEM. 2006;8:19–20. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500013336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoolack CEM, Aerts JMFG, Aymé S, Manuel J. Limitations of drug registries to evaluate orphan medicinal products for the treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinreb NJ, Kaplan P. The history and accomplishments of the ICGG Gaucher registry. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(Suppl 1):S2–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are held by the University of Cambridge under a Medical Research Council approved Data Management Policy. Restrictions apply and data are not publicly available: applications from bona fide organizations will be considered by the University of Cambridge and clinical governance of Cambridge University NHS Foundation Trust Hospitals and subject to approval by the Gaucherite Consortium Management Committee. Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.