Abstract

Background

A strong association between epilepsy and onchocerciasis endemicity has been reported. We sought to document the epidemiology of epilepsy in onchocerciasis-endemic villages of the Ntui Health District in Cameroon and investigate how this relates to the prevalence of onchocerciasis.

Methods

In March 2022, door-to-door epilepsy surveys were conducted in four villages (Essougli, Nachtigal, Ndjame, and Ndowe). Ivermectin intake during the 2021 session of community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) was investigated in all participating village residents. Persons with epilepsy (PWE) were identified through a two-step approach: administration of a 5-item epilepsy screening questionnaire followed by clinical confirmation by a neurologist. Epilepsy findings were analyzed together with onchocerciasis epidemiological data previously obtained in the study villages.

Results

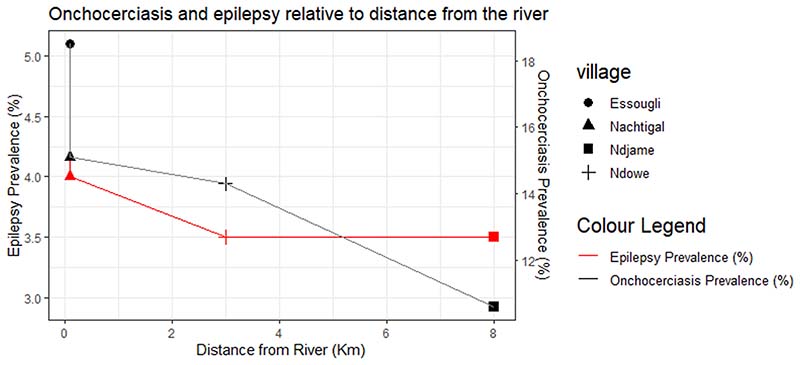

We surveyed 1663 persons in the four study villages. The 2021 CDTI coverage for all study sites was 50.9%. Overall, 67 PWE were identified (prevalence of 4.0% (IQR: 3.2–5.1) with one new-onset case during the past 12 months (annual incidence of 60.1 per 100,000 persons). The median age of PWE was 32 years (IQR: 25–40), with 41 (61.2%) being females. The majority (78.3%) of PWE met the previously published criteria for onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy (OAE). Persons with a history of nodding seizures were found in all villages and represented 19.4% of the 67 PWE. Epilepsy prevalence was positively correlated with onchocerciasis prevalence (Spearman Rho = 0.949, p = 0.051). Meanwhile, an inverse relationship was observed between distance from the Sanaga river (blackfly breeding site) and the prevalence of both epilepsy and onchocerciasis.

Conclusion

The high epilepsy prevalence in Ntui appears to be driven by onchocerciasis. It is likely that decades of CDTI have likely contributed to a gradual decrease in epilepsy incidence, as only one new case occurred in the past year. Therefore, more effective elimination measures are urgently needed in such endemic areas to curb the OAE burden.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Onchocerciasis, Sanaga River, Cameroon, Ivermectin coverage, Nodding syndrome

1. Introduction and background

Epilepsy is one of the most prevalent neurological conditions worldwide and the recent adoption by the World Health Organization (WHO) of the Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP) for epilepsy and other neurological diseases [1] highlights the importance and urgency of implementing control measures globally. However, there is an obvious disparity in the geographical distribution of cases, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) experiencing a greater burden of epilepsy than high-income countries (HICs) [2]. Indeed, a meta-analysis estimated epilepsy prevalence at 8.75 per 1000 in LMICs as opposed to 5.18 per 1000 in HICs [3]. In Sub-Saharan Africa specifically, the median epilepsy prevalence is 1.4% [4]; notwithstanding, epilepsy prevalence rates above 7% have been reported in some communities [5,6]. A previous study found an annual incidence of epilepsy of 171 per 100,000 persons in some areas in Cameroon [7]. In these areas, the treatment gap reportedly remains high (80%) which is likely related to the high levels of stigma [8,9]. Among other causes, parasitic infections such as malaria, toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis, and onchocerciasis constitute the most important risk factors for epilepsy in tropical Africa [4,10–12].

In general, it has been observed that onchocerciasis-endemic communities tend to have high epilepsy prevalence [13] and that the epilepsy burden declines once optimal onchocerciasis prevention measures are instituted [14–17]. The pathophysiological mechanisms of onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy (OAE) are still unknown, but there are suggested hypotheses about the possible direct passage of the Onchocerca volvulus parasite or its derived substances into the central nervous system under certain conditions [18].

Particularly in Cameroon, previous surveys have suggested a strong association between epilepsy and onchocerciasis [6,19–22]. However, these past studies often focused on onchocerciasis foci located along the Mbam River, a tributary of the Sanaga. Although the Sanaga river (the longest river in Cameroon) also harbors several blackfly breeding sites which render the surrounding villages endemic for onchocerciasis as well as OAE [23], few studies have been done in villages along its banks. In a bid to identify breeding sites in the Sanaga river where vector control activities can be implemented to reduce onchocerciasis transmission and epilepsy prevalence/incidence, we initiated a project in selected villages along this river [24]. In the present paper, we report the baseline findings regarding the epilepsy situation in the study villages and how this relates to the onchocerciasis endemicity levels prior to implementing vector control measures.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and population

The study was conducted in March 2022 in the Ntui Health District, a known onchocerciasis focus in Cameroon with blackfly breeding sites along the Sanaga river [25]. In a previous hospital-based survey in the suburban city of Ntui by our team, we suggested the occurrence of onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy (OAE) in this area [23]. Four rural villages were selected for this study based on distance from the river: two of them were first-line villages, that is, bordering fast-flowing segments of the Sanaga river (Essougli, Nachtigal) while the other two villages were located a little further inland from the river (Ndjame ≈ 8 km, Ndowe ≈ 5 km); see Fig. 1. All study villages have a tropical climate and forest landscape, with rainfall levels estimated at 1700– 1850 mm per year [26]. Annual community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) has been conducted in the Ntui Health District for over two decades, although therapeutic coverage is often sub-optimal (<80%). The main activity is agriculture, with fewer individuals involved in fishing, manual work, or white-collar jobs. All individuals residing in the villages for at least six months were eligible to participate in the study.

Fig. 1. Map of the study area in the Ntui Health District.

There are two riverside villages (Nachtigal and Essougli) and two inland villages (Ndjame and Ndowe). The Nachtigal dam (under construction) is located upstream of the two riverside study sites.

2.2. Study design and procedures

We conducted cross-sectional community-based door-to-door surveys in each of the study villages. This approach is considered the gold standard for epidemiological studies on epilepsy [27]. A few weeks prior to the data collection phase, the research team met with the administrative and health authorities of the study area as well as the traditional chiefs to explain the purpose of the study to them and obtain their collaboration. They were also asked to sensitize the villagers to be available in their homes for the upcoming door-to-door study, with precise dates as per the agreed planning.

The research team that was deployed for fieldwork consisted of neurologists (LN, MKM, LNN), a physician trained in epilepsy (CA), a research physician/clinical epidemiologist (JNSF), and a field researcher (JNTN). These researchers were teamed up with the community health workers of each village, who served as local guides to introduce the research teams to the different homes. In each village, households were visited one after the other and given a unique identification code by the investigators. In case a household was found to be empty, a second visit was planned either on the same day or the following day. The signed informed consent of the household head or his/her representative was obtained, after which we administered the survey questionnaire. One adult member was the main respondent to the questionnaire in each household, with further inputs from other household members if required.

Identification of epilepsy cases was done in two steps: firstly, we obtained information about all the household members (age, sex, ivermectin intake during the last CDTI campaign, and responses to a validated 5-item epilepsy screening questionnaire [28]). The second step was reserved only for households where at least one member responded affirmatively to any one of the five epilepsy screening questions. For such individuals (termed “suspected cases of epilepsy” or SCE), a second more detailed questionnaire was administered by the neurologists followed by a thorough physical examination when possible, to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of epilepsy including nodding seizures (involuntary repetitive head bobbing to the chest, a typical feature of OAE). We also asked questions on the approximate financial expenses for epilepsy care, as well as the treatment options chosen by PWE and their families. The geographical information system (GIS) coordinates of the homes of all confirmed persons with epilepsy (PWE) were obtained using a Garmin GPSMAP78 device. All data were collected on paper forms.

2.3. Data processing and analysis

At the end of each survey day, the filled paper forms were cross-checked by the clinical epidemiologist, and any inconsistencies were resolved by discussing with the rest of the team or by returning to the household in question the following day as needed. The verified data were then entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, cleaned, and analyzed using R version 4.0.2. Epilepsy direct cost was estimated by summing up the expenses related to epilepsy care including the purchase of treatment and transport to the health facility; these were used to calculate the mean direct cost for all PWE. Other continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile range (IQR) and compared across groups using non-parametric statistical tests. As for categorical variables, we expressed them as percentages and compared them using the Chi-squared test or Fischer exact test as appropriate.

We investigated the performance of the 5-item epilepsy screening questionnaire in identifying PWE in our study population. Finally, we applied the epidemiological OAE criteria [29] on all confirmed PWE in order to confirm whether an important proportion of epilepsy in the study villages could be related to onchocerciasis. For all analyses, a two-sided p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethical considerations

This study received the ethical approval of the institutional review board of the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board (Ref: IRB2021-03) and a research permit for the project was granted by Cameroon’s Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation (Ref: 000144/MINRESI/B00/C00/C10/C13). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. All collected data were treated with absolute confidentiality.

3. Results

3.1. Study villages and participants

Overall, we surveyed 1663 individuals in 273 households. Given that we encountered empty households (despite repeated visits) or refusals to participate in 11 households, we estimate that the surveyed population represents 96.1% (273/284 households) of the inhabitants in these villages. Median household size was 5 (IQR: 4 – 8), and Ndowe village had the highest proportion of immigrant households (that is, families who are not natives of the village but moved in for residence) (see Table 1). The mean number of PWE per household was higher among native households compared to immigrant households: 0.27 vs 0.06, Mann-Whitney U p-value = 0.023. Furthermore, native households were more likely to have at least one person with epilepsy compared to immigrant households (55/239 vs 2/34; χ2 = 4.301, p-value = 0.038).

Table 1. Household characteristics in the study villages.

| Number of households | Essougli | Nachtigal | Ndjame | Ndowe | P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 70 | n = 96 | n = 88 | n = 19 | 273 | ||

| Native household: n (%) | 60 (85.7%) | 88 (91.7%) | 84 (95.5%) | 7 (36.8%) | <0.001 | 273 |

| Immigrant household: n (%) | 10 (14.3%) | 8 (8.3%) | 4 (4.6%) | 12 (63.2%) | <0.001 | 273 |

| Duration of stay for immigrants, in years: Median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0 – 10.0) | 6.0 (4.8 – 13.8) | 3.0 (2.5 – 21.5) | 6.5 (3.3 – 12.8) | 0.897 | 30 |

| Household size: Median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0 – 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0 – 7.0) | 6.0 (4.0 – 9.0) | 5.0 (4.0 – 8.0) | 0.254 | 273 |

| Activity of household head | 0.240 | 273 | ||||

| Farming | 68 (97.1%) | 90 (93.8%) | 83 (94.3%) | 18 (94.7%) | ||

| Fishing | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Builder | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Chief | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Commerce | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | ||

| Craftsman | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Nurse | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Pastor | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Transportation/driver | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Mean number of PWE per household (SD) | 0.27 (0.54) | 0.24 (0.52) | 0.23 (0.45) | 0.21 (0.92) | 0.952 | 273 |

| Household with at least one PWE: n (%) | 16 (22.9%) | 21 (21.9%) | 19 (21.6%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.385 | 273 |

| Mean number of PWE in households having at least one PWE (SD) | 1.19 (0.40) | 1.14 (0.48) | 1.05 (0.23) | NA | 0.452 | 56 |

IQR: Interquartile range; SD: Standard deviation; PWE: Person with epilepsy; N: Number of participants included in the analysis for the variable being described; NA: Not applicable (only one household with PWE was identified in Ndowe, hence impossible to calculate the mean).

The overall median age of the village residents was 20 years (IQR: 8–39). There were almost equal proportions of males (50.9%) and females (49.1%). Persons with epilepsy were found in all four study sites, with no significant differences in epilepsy prevalence across the villages (Table 2). The overall ivermectin coverage for the July 2021 CDTI session was 50.9% for all study villages, with Ndowe village having the lowest coverage (Table 2). The most frequent reasons for not taking ivermectin (n = 757) included: age below 5 years at the time of CDTI for 269 (35.5%); absent/unavailable during CDTI for 155 (20.5%); claims that ivermectin was not distributed to their household for 109 (14.4%); fear of side effects for 93 (12.3%); and systematic refusal for 74 (9.8%). The exhaustive list of reasons given is available in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2. Participants characteristics in the study villages.

| Nº participants | Essougli | Nachtigal | Ndjame | Ndowe | P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 390 | N = 577 | N = 580 | N = 116 | 1663 | ||

| Age in years: Median (IQR) | 25.0 (12.0–43.0) | 19.0 (7.8–38.0) | 18.0 (7.0–39.0) | 17.0 (6.8–33.0) | 0.001 | 1658 |

| Gender: n (%) | 0.598 | 1663 | ||||

| Female | 183 (46.9%) | 279 (48.4%) | 296 (51.0%) | 59 (50.9%) | ||

| Male | 207 (53.1%) | 298 (51.6%) | 284 (49.0%) | 57 (49.1%) | ||

| CDTI coverage in 2021: n (%) | 191 (52.2%) | 264 (47.9%) | 316 (57.0%) | 36 (31.0%) | <0.001 | 1587 |

| Suspected epilepsy: n (%) | 21 (5.4%) | 26 (4.5%) | 21 (3.6%) | 4 (3.5%) | 0.570 | 1663 |

| Confirmed epilepsy: n (%) | 20 (5.1%) | 23 (4.0%) | 20 (3.5%) | 4 (3.5%) | 0.627 | 1663 |

IQR: Interquartile range; CDTI: Community-directed treatment with ivermectin; N: Number of participants included in the analysis for the variable being described.

The five questions for screening epilepsy had a Cronbach alpha value of 0.87. Among the positively screened study participants who were evaluated by a neurologist, the sensitivity of the 5-item screening tool was 98.5% (95% CI: 92–100), and the specificity of 99.6% (95% CI: 99–100). However, when considering the individual questions, the highest sensitivity was found with Question 1 (91.0%), while the highest specificity was found with Question 4 (100%); see Supplementary Material S2. The screening tool had its optimal Cronbach alpha value of 0.97 only when questions 1, 2, and 3 were kept. Overall, the positive predictive value of the 5-item screening tool in our study was 91.7% (95% CI: 83–97).

3.2. Description of persons with epilepsy

The 5-item screening tool identified 72 participants (4.3%) who were suspected to have epilepsy (SCE). More detailed information could be obtained for 69 of these SCEs; for the remaining three, it was impossible to obtain further details because they were absent and no one else in the household was knowledgeable enough to provide the required information. Of the 69 SCE for whom detailed information could be obtained, the neurologists concluded that 67 of them had epilepsy, giving an overall epilepsy prevalence of 4.0% (95% CI: 3.2–5.1). Of the two SCEs who were not confirmed to have epilepsy, one was diagnosed with alcohol-induced seizures (provoked, hence not epilepsy), while the other was diagnosed as having a psychiatric problem without epilepsy. Of note, for the 67 confirmed PWE, the investigators were able to meet the PWE in person in 47/67 (70.1%) of cases, while for 20 (29.9%) of them, the information was provided by a close relative which permitted the confirmation of the epilepsy diagnosis in the absence of the SCE.

The overall median age of PWE was 32 years (IQR: 25 – 40), with significantly older cases in Ndjame village (Table 3). The majority of cases (n = 41, representing 61.2%) were females. The gender-specific prevalence of epilepsy was 25/846 (3.0%) for males and 42/817 (5.1%) for females; p = 0.030. The median age at seizure onset was 12 years (IQR: 8 – 15), range: 2 – 71 years. Only one PWE (10-year-old boy residing in Essougli village) reported seizure onset within the last 12 months (incidence: 1/1663 or 60.1 per 100,000 persons per year). Of the 67 confirmed PWE, 54 (78.3%) fulfilled the epidemiological criteria for OAE. Furthermore, 49 (73.1%) PWE had dropped out of school following seizure onset. Only 35/67 (52.2%) of the identified PWE took anti-seizure medications (ASM) regularly. The ivermectin coverage for the 2021 session among PWE was 55.4%, similar to the coverage among those without epilepsy (50.7%); p = 0.582.

Table 3. Characteristics of persons with epilepsy.

| Essougli | Nachtigal | Ndjame | Ndowe | P-value | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 20 | N = 23 | N = 20 | N = 4 | |||

| Age in years: Median (IQR) | 29.5 (25.8 – 35.2) | 31.0 (24.0 – 33.5) | 38.5 (31.5 – 45.2) | 28.5 (24.5 – 31.5) | 0.055 | 67 |

| Gender: n (%) | 0.864 | 67 | ||||

| Female | 11 (55.0%) | 15 (65.2%) | 12 (60.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Male | 9 (45.0%) | 8 (34.8%) | 8 (40.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Education level: n (%) | 0.738 | 66 | ||||

| None | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Primary | 18 (90.0%) | 19 (86.4%) | 16 (80.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Secondary | 2 (10.0%) | 3 (13.6%) | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Specific diagnosis: n (%) | 0.325 | 67 | ||||

| Nodding Seizures | 2 (10.0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 5 (25.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Other forms of epilepsy | 18 (90.0%) | 18 (78.3%) | 15 (75.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| History of nodding seizures: n (%) | 0.429 | 67 | ||||

| In the past | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Ongoing | 1 (5.0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Never | 18 (90.0%) | 18 (78.3%) | 15 (75.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Age at seizure onset: Median (IQR) | 12.5 (8.8 – 15.0) | 10.0 (8.0 – 14.5) | 13.5 (10.0 – 16.2) | 13.0 (10.5 – 14.0) | 0.494 | 67 |

| Seizure frequency per month: Median (IQR) | 0.30 (0.00 – 2.00) | 2.00 (0.30 – 4.00) | 2.00 (1.00 – 4.3) | 0.00b (0.00 – 0.00) | 0.002 | 67 |

| Seizure during the past week: n (%) | 5 (25.0%) | 20 (43.5%) | 11 (57.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.437 | 65 |

| Family history of epilepsya: n (%) | 15 (75.0%) | 17 (73.9%) | 11 (55.0%) | 4 (100%) | 0.296 | 67 |

| Burn scars: n (%) | 5 (41.7%) | 6 (30.0%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.426 | 47 |

| Traumatic wound scars: n (%) | 7 (58.3%) | 10 (50.0%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.517 | 47 |

| Leopard skin: n (%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.69%) | 0 (0%) | 0.020 | 47 |

| Anti-seizure treatment: n (%) | 0.951 | 67 | ||||

| Anti-seizure medications (ASM) | 15 (75.0%) | 17 (73.9%) | 17 (85.0%) | 4 (100%) | ||

| Traditional treatment only | 0(0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| ASM and traditional treatment | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| None | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (17.4%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| ASM compliance: n (%) | 0.209 | 62 | ||||

| Regular | 11 (55.0%) | 12 (63.2%) | 8 (42.1%) | 4 (100%) | ||

| Irregular | 6 (30.0%) | 7 (36.8%) | 10 (52.6%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Never | 3 (15.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.26%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Ever taken ivermectin: n (%) | 13 (65.0%) | 15 (65.2%) | 15 (83.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.019 | 65 |

| Ivermectin use before seizure onset: n (%) | 3 (15.8%) | 5 (21.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.876 | 60 |

| Fulfil OAE criteria: n (%) | 15 (75.0%) | 20 (87.0%) | 16 (80.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.685 | 67 |

IQR: Interquartile range; ASM: Anti-seizure medications; N: Number of participants included in the analysis for the variable being described;

Family history of epilepsy defined as the occurrence of epilepsy in a first-degree relative.

All four PWE in Ndowe had <1 seizure per year, as they all took anti-seizure medications daily.

Considering PWE from all villages combined, the median seizure frequency per month was 1.0 (IQR: 0.2 – 4.0); range: 0 – 25. The most frequent seizure type at the time of the survey was generalized tonic-clonic seizures, reported by 55 (82.1%) PWE; this was followed by absence seizures in 16 (23.9%), nodding seizures in 10 (14.9%), focal seizures with altered consciousness in 3 (4.5%), focal seizures with conserved consciousness in 2 (3.0%), and atonic seizures in 2 (3.0%). In addition to the 10 PWE currently experiencing nodding seizures, three other PWE reported nodding seizures in the past bringing the number of PWE with a history of nodding seizures to 13 (19.4%).

3.3. Management of epilepsy and economic cost of care

Fifty-seven PWE (85.1%) reported ever taking anti-seizure medications (ASM), with or without traditional medicine; however, only 35 (52.2%) of all PWE took their medication on a regular (daily) basis. Two types of medication were frequently used by PWE who took ASM: Phenobarbital in 23/57 (40.4%) of them, and carbamazepine in the remaining 34/57 (59.6%). In addition, 3 (5.3%) reported also taking valproate for their seizures.

The mean direct cost of epilepsy was 3505 ± 3180 XAF per PWE and per month. This cost was distributed across three main categories: cost of ASM (2465 ± 2419 XAF), cost of traditional medicine (212 ± 1222 XAF), and cost of transport to purchase treatment every month (827 ± 932 XAF).

3.4. Relationship between epilepsy and onchocerciasis

Based on the prevalence of onchocerciasis which we obtained in the four study villages during a previous survey [25], we found a strong correlation between epilepsy prevalence and onchocerciasis prevalence, with borderline statistical significance: Spearman Rho = 0.949, p = 0.051 (see Supplementary Material S3). Furthermore, we observed a trend whereby the distance of the village from the Sanaga river (blackfly breeding site) was inversely related to the prevalence of both onchocerciasis (Spearman Rho = –0.949, p = 0.051) and epilepsy (Spearman Rho = –0.889, p = 0.111); see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Onchocerciasis and epilepsy prevalence relative to distance from the Sanaga river.

4. Discussion

Our survey found an epilepsy prevalence of 4.0% which is significantly higher than the median 1.4% prevalence reported in the SSA region [4]. Such high epilepsy prevalence, with over three-quarters of the PWE meeting the OAE criteria, confirm previous findings by Morin et al. of the frequent occurrence of OAE in the Ntui area [23]. Interestingly, at least one case with nodding seizures was identified in each village but no participant with Nakalanga syndrome was found in our study population. This is consistent with previous findings from endemic communities in the Mbam valley in Cameroon where only one case of Nakalanga syndrome was found after surveying five villages [30], suggesting that although onchocerciasis transmission persists in Cameroonian communities, the infectious context (for instance: O. volvulus parasitic levels and chronicity of infection) may be enough just to trigger seizures, but not suffice to induce Nakalanga features in the affected individuals. Indeed, the reported community microfilarial loads in our study sites are rather low (values below 2 were reported [25]), supporting ongoing onchocerciasis transmission but with few parasites in circulation.

The PWE identified during our survey in 2022 were older compared to those recruited by Morin et al. during a previous survey in Ntui in 2018 [23] (median ages of 32 vs 25 years). While this could be due to a selection bias (Morin et al. did not conduct a door-to-door study), it could also be that the several years of CDTI have gradually decreased OAE incidence in the younger age groups resulting in a cohort age shift among PWE as the previously identified cases grow older. A similar phenomenon was described among PWE in onchocerciasis foci in Northern Uganda [15] and the Mbam valley of Cameroon [6]. This explanation is further supported by the low epilepsy incidence (60.1 per 100,000 persons per year) observed in our study sites in 2022, owing most likely to onchocerciasis control activities for more than two decades. Furthermore, with increasing access to ASM, PWE in Cameroon are now expected to live longer and grow older in contrast with the situation two decades ago [31].

A family history of epilepsy was frequently reported among PWE in our study. While genetics certainly play a role in the susceptibility to develop epilepsy, the occurrence of several epilepsy cases within a given household in onchocerciasis-endemic villages could also be due to increased exposure to blackflies if the household resides close to breeding sites. For instance, the four PWE in Ndowe all came from the same household, in a location close to the river. Indeed, our study as well as previous research [5,19] demonstrate that communities residing closer to the river tend to have more epilepsy cases.

Regarding epilepsy treatment, the proportion of PWE having access to regular ASM in this study (52.2%) was lower than the 60.9% found earlier in other villages of the Mbam and Sanaga river valleys [30]. Furthermore, in the North-West region of Cameroon, Angwafor et al. reported that although ASM was taken by 85% of PWE, most were receiving inappropriate treatment or were non-adherent, hence the high treatment gap of 80% [8]. This attests to the wide treatment gap that still exists in Cameroonian villages, contributing to poor seizure control and unfavorable prognosis of epilepsy in such settings [31]. The provision of cheap/free ASMs would go a long way to improve the quality of life of PWE in these villages.

The monthly direct cost of epilepsy was estimated at 3,505 XAF (≈ 6.6 USD), with over 70% used to purchase ASM. As the majority of residents depend on subsistence farming for a living, it is often difficult to afford the care of PWE consistently. Persons with epilepsy are also confronted with significant stigma and high school drop-out rates (73.1% in our study), which further compounds the precarious state of their households [32]. It is therefore important to consider epilepsy in such settings as a disease of poverty and implement appropriate interventions that would go beyond just treating seizures, but also facilitating the socio-professional rehabilitation of PWE [33].

The 50.9% therapeutic coverage of the 2021 CDTI session in our study population, similar to the 54.2% coverage obtained in these same villages without using a door-to-door approach [25], falls way below the optimal threshold of 85% needed to rapidly achieve onchocerciasis elimination [34]. This may be indicative of regular sub-optimal coverage rates over the years, explaining why onchocerciasis transmission persists in these villages despite more than two decades of annual mass treatment with ivermectin. The reported CDTI coverage is also lower than what was previously found in other villages of Cameroon [6,35]; this could be due to high levels of systematic non-adherence to CDTI (9.8% of all non-adherent persons among our participants), concurring with previous findings from Cameroonian villages [35]. Such persons who systematically deny ivermectin treatment constitute a threat to achieving onchocerciasis elimination since they could remain infected and serve as parasitic reservoirs that will keep population infection rates above zero. It is expedient that more effective onchocerciasis elimination programs be deployed and sustained in these villages where OAE persists, as this would curb the epilepsy burden [14]. Indeed, the fact that less than one-fifth of the identified PWE had received ivermectin prior to their first seizure suggests that they could have been heavily infected with O. volvulus during their childhood which may have eventually triggered their seizures later in life [21].

Our study is not void of limitations. Although we used a door-to-door approach, some village residents were not seen by the research team and some PWE were unavailable for a physical examination by the neurologist. Furthermore, the fact that for many households the information about all household members was provided by only one individual may have affected the accuracy of such data as the “exact age of other household members”.

5. Conclusion

We found a high prevalence of epilepsy in all study four study villages, with epidemiological and clinical features of PWE that are consistent with OAE. The lower-than-expected annual incidence of epilepsy recorded in these villages in 2022 suggests that mass treatment with ivermectin for onchocerciasis elimination may have played a role in preventing new cases of OAE during recent years. A comprehensive approach may be required to address the wide treatment gap among PWE and ensure their psychosocial well-being in the community. Quelling the observed high OAE prevalence warrants that CDTI be strengthened and supplemented with alternative approaches such as vector control to accelerate onchocerciasis elimination prospects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to various scientific collaborators who worked on the project, the population in the study villages, as well as all the local authorities and volunteers for their participation.

Funding

This project is part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union (grant number TMA2020CDF-3152-SCONE) awarded to JNSF.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

JNSF and AKN conceived and designed the study. LN, JNSF, CA, LNN, JNTN, and MKM were involved in the fieldwork and data collection. JNSF cleaned and analyzed the data. JNSF wrote the first draft and all authors critically reviewed, corrected, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board (Ref: IRB2021-03) and a research permit for the project was granted by Cameroon’s Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation (Ref: 000144/MINRESI/B00/C00/C10/C13). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all persons described in this paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Leonard Ngarka, Email: leonard.ngarka@brainafrica.org.

Joseph Nelson Siewe Fodjo, Email: jsieweking@gmail.com.

Calson Ambomatei, Email: calsonambomatei@yahoo.com.

Wepnyu Yembe Njamnshi, Email: wepnyu.njamnshi@brainafrica.org.

Julius Ndi Taryunyu Njamnshi, Email: njamjulius@gmail.com.

Leonard N. Nfor, Email: nfor.leonard@gmail.com.

Michel K. Mengnjo, Email: mengnjomichel@yahoo.com.

Availability of data and material

The datasets for our study findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].WHO. World Health Assembly Adopts the Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and Other Neurological Disorders 2022-2031 [Internet] [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://worldneurologyonline.com/article/who-world-health-assembly-adopts-the-intersectoral-global-action-plan-on-epilepsy-and-other-neurological-disorders-2022-2031/

- [2].Beghi E. The Epidemiology of Epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54:185–91. doi: 10.1159/000503831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S, Patten SB, Kwon C-S, Dykeman J, et al. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology. 2017;88:296–303. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ba-Diop A, Marin B, Druet-Cabanac M, Ngoungou EB, Newton CR, Preux P-M. Epidemiology, causes, and treatment of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1029–44. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Colebunders R, Carter JY, Olore PC, Puok K, Bhattacharyya S, Menon S, et al. High prevalence of onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy in villages in Maridi County, Republic of South Sudan: A community-based survey. Seizure. 2018;63:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Siewe Fodjo JN, Tatah G, Tabah EN, Ngarka L, Nfor LN, Chokote SE, et al. Epidemiology of onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy in the Mbam and Sanaga river valleys of Cameroon: impact of more than 13 years of ivermectin. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7 doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Angwafor SA, Bell GS, Ngarka L, Otte W, Tabah EN, Nfor LN, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy and associated factors in a health district in North-West Cameroon: A population survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;121:108048. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Angwafor SA, Bell GS, Ngarka L, Otte WM, Tabah EN, Nfor LN, et al. Epilepsy in a health district in North-West Cameroon: Clinical characteristics and treatment gap. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;121:107997. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Njamnshi AK, Angwafor SA, Tabah EN, Jallon P, Muna WFT. General public knowledge, attitudes, and practices with respect to epilepsy in the Batibo Health District. Cameroon Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kamuyu G, Bottomley C, Mageto J, Lowe B, Wilkins PP, Noh JC, et al. Exposure to Multiple Parasites Is Associated with the Prevalence of Active Convulsive Epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Garcia HH, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Angwafor SA, Bell GS, Njamnshi AK, Singh G, Sander JW. Parasites and epilepsy: Understanding the determinants of epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;92:235–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Owolabi LF, Adamu B, Jibo AM, Owolabi SD, Imam AI, Alhaji ID. Neurocysticercosis in people with epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and strength of association. Seizure. 2020;76:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Colebunders R, Njamnshi AK, Menon S, Newton CR, Hotterbeekx A, Preux P-M, et al. Onchocerca volvulus and epilepsy: A comprehensive review using the Bradford Hill criteria for causation. Bennuru S, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0008965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gumisiriza N, Kaiser C, Asaba G, Onen H, Mubiru F, Kisembo D, et al. Changes in epilepsy burden after onchocerciasis elimination in a hyperendemic focus of western Uganda: a comparison of two population-based, cross-sectional studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1315–23. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gumisiriza N, Mubiru F, Siewe Fodjo JN, Mbonye Kayitale M, Hotterbeekx A, Idro R, et al. Prevalence and incidence of nodding syndrome and other forms of epilepsy in onchocerciasis-endemic areas in northern Uganda after the implementation of onchocerciasis control measures. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:12. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-0628-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Siewe Fodjo JN, Remme JHF, Preux P-M, Colebunders R. Meta-analysis of epilepsy prevalence in West Africa and its relationship with onchocerciasis endemicity and control. Int Health. 2020;12:192–202. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Siewe Fodjo JN, Ukaga CN, Nwazor EO, Nwoke MO, Nwokeji MC, Onuoha BC, et al. Low prevalence of epilepsy and onchocerciasis after more than 20 years of ivermectin treatment in the Imo River Basin in Nigeria. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8 doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hadermann A, Amaral L-J, Van Cutsem G, Siewe Fodjo JN, Colebunders R. Onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy: an update and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2023;39:126–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2022.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boussinesq M, Pion SD, Ngangue D, Kamgno J. Relationship between onchocerciasis and epilepsy: a matched case-control study in the Mbam Valley, Republic of Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:537–41. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Boullé C, Njamnshi AK, Dema F, Mengnjo MK, Siewe Fodjo JN, Bissek A-C-Z-K, et al. Impact of 19 years of mass drug administration with ivermectin on epilepsy burden in a hyperendemic onchocerciasis area in Cameroon. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:114. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chesnais CB, Nana-Djeunga HC, Njamnshi AK, Lenou-Nanga CG, Boullé C, Bissek A-C-Z-K, et al. The temporal relationship between onchocerciasis and epilepsy: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1278–86. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chesnais CB, Bizet C, Campillo JT, Njamnshi WY, Bopda J, Nwane P, et al. A second population-based cohort study in Cameroon confirms the temporal relationship between onchocerciasis and epilepsy. Open Forum. Infect Dis. 2020:ofaa206. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morin A, Guillaume M, Ngarka L, Tatah GY, Siewe Fodjo JN, Wyart G, et al. Epilepsy in the Sanaga-Mbam valley, an onchocerciasis-endemic region in Cameroon: electroclinical and neuropsychological findings. Epilepsia Open. 2021:epi4.12510. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fodjo JNS, Vieri MK, Ngarka L, Njamnshi WY, Nfor LN, Mengnjo MK, et al. BMJ Open. Vol. 11. British Med J Publish Group; 2021. ‘Slash and clear’ vector control for onchocerciasis elimination and epilepsy prevention: a protocol of a cluster randomised trial in Cameroonian villages; e050341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Siewe Fodjo JN, Ngarka L, Njamnshi WY, Enyong PA, Zoung-Kanyi Bissek A-C, Njamnshi AK. Onchocerciasis in the Ntui Health District of Cameroon: epidemiological, entomological and parasitological findings in relation to elimination prospects. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15:444. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05585-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hendy A, Krit M, Pfarr K, Laemmer C, De Witte J, Nwane P, et al. Onchocerca volvulus transmission in the Mbam valley of Cameroon following 16 years of annual community-directed treatment with ivermectin, and the description of a new cytotype of Simulium squamosum. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:563. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-05072-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bharucha N, Odermatt P, Preux P-M. Methodological Difficulties in the Conduct of Neuroepidemiological Studies in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42:7–15. doi: 10.1159/000355921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Diagana M, Preux PM, Tuillas M, Ould Hamady A, Druet-Cabanac M. Dépistage de l’épilepsie en zones tropicales: validation d’un questionnaire en Mauritanie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2006;99:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Colebunders R, Siewe Fodjo JN, Hopkins A, Hotterbeekx A, Lakwo TL, Kalinga A, et al. From river blindness to river epilepsy: Implications for onchocerciasis elimination programmes. Hübner MP, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Siewe Fodjo JN, Ngarka L, Tatah G, Mengnjo MK, Nfor LN, Chokote ES, et al. Clinical presentations of onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy (OAE) in Cameroon. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;90:70–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kamgno J, Pion SDS, Boussinesq M. Demographic impact of epilepsy in Africa: results of a 10-year cohort study in a rural area of Cameroon. Epilepsia. 2003;44:956–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.59302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].O’Neill S, Irani J, Siewe Fodjo JN, Nono D, Abbo C, Sato Y, et al. Stigma and epilepsy in onchocerciasis-endemic regions in Africa: a review and recommendations from the onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy working group. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8:34. doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Siewe Fodjo JN, Dekker MCJ, Idro R, Mandro MN, Preux P-M, Njamnshi AK, et al. Comprehensive management of epilepsy in onchocerciasis-endemic areas: lessons learnt from community-based surveys. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8 doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Burnham G, Mebrahtu T. Review: The delivery of ivermectin (MectizanR) Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:A26–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kamga G-R, Dissak-Delon FN, Nana-Djeunga HC, Biholong BD, Ghogomu SM, Souopgui J, et al. Audit of the community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) for onchocerciasis and factors associated with adherence in three regions of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:356. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2944-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for our study findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.