The Covid-19 pandemic has shaken the world. Aside from its direct consequences through the disease process itself, the outbreak has had a devastating social and economic impact. In the UK, numbers of hospital admissions and deaths due to the disease peaked in April [1]. Strict social distancing measures have contributed to a decline in reported cases [2], which has been followed by a gradual re-opening of society. However, the number of positive test results has risen over the last two months. What does this tell us about the nature of the current “second wave”, and how should we respond?

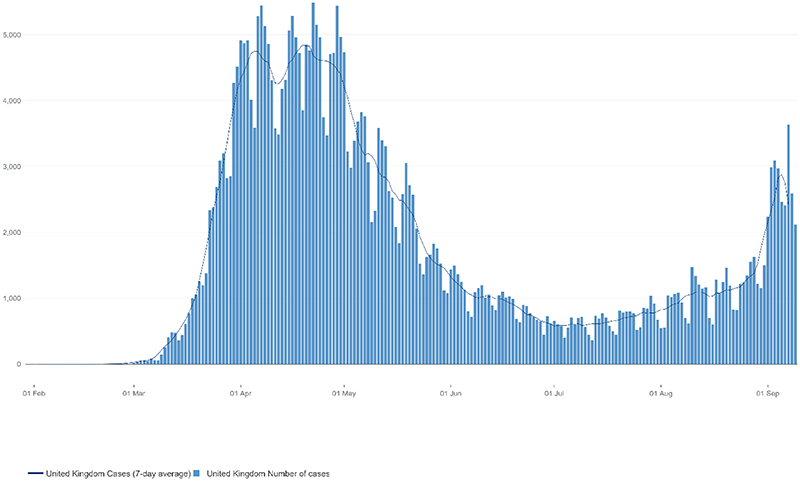

The present scale of the infection is nowhere near as bad as it was in the late spring. Comparisons of the number of positive test results are misleading if conducted across the whole history of the pandemic. The raw numbers of positive test results in the UK (Figure 1) show that the current number is around one-third to one-half of that at the peak in mid-April. However, the testing conditions have varied considerably across the course of the pandemic. In April, government-administered tests were mostly available to those in hospitals and care settings. At that point in the pandemic, Golding et al estimate that the number of positive tests represented around 7-10% of the total number of infections in the UK [3]. Modelling of infection incidence by Birrell et al [4] tells a similar story: incidence in England peaked on March 23rd at 352,000 (95% credible interval 279,000 to 454,000), while the number on July 31st was 3,200 (95% credible interval 1,700 to 5,800). Community-based surveys by the Office of National Statistics reported 148,000 people (95% credible interval: 94,000 to 222,000) in England had COVID-19 at any given point between 27th April and 10th May [5], but only 27,100 people (95% credible interval: 19,300 to 36,700) in England and Wales had COVID-19 at any given point between 19th and 25th August [6]. Additionally, the burden of positive test results is increasingly being seen in younger people, who are less susceptible to severe illness [7].

Figure 1.

Number of people with at least one lab-confirmed positive COVID-19 test result, by specimen date. Individuals who tested positive more than once are only counted once, on the date of their first positive test. Taken from https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/cases

On the other hand, there is mounting evidence that the rise in numbers of positive tests represents a real rise in the number of those infected. Data collected by Riley et al on 120,000 to 160,000 individuals in England showed stable levels of community infection in May and June, but increasing levels of infection in July and August, with most recent figures suggesting a doubling time for infections of 7.7 (95% credible interval 5.5 to 12.7) days [8]. Although this is less than the doubling time around the time of lockdown in late March, which has been estimated at 2.8 (95% credible interval 2.6 to 3.0) days [9], the situation needs to be handled carefully.

Steps taken to move closer towards “normal” life (such as the re-opening of schools) have both short- and long-term consequences. In the short term, it is expected that the number of infections rises at each step due to increased social contact. Once social networks have been established (or re-established), the long-term consequences of viral transmission patterns in the new social network can be observed. An effective response system based on testing, contact tracing and household quarantine can be effective for controlling viral spread in a second wave [10]. Adherence to such control measures is critical for reversing the upturn in positive cases. Given that current levels of infection are relatively low, the absolute impact of a temporary increase in infection rates is likely manageable. If we see a sustained increase in positive test numbers in the absence of additional steps towards “normal” life, then further action will be necessary until control is achieved.

In summary, the current Covid-19 situation in the UK is nowhere near as bad as it was at the peak of the outbreak. While we can perhaps meaningfully compare positive test numbers today to those from one day ago, or even one week ago, it is not appropriate to compare to those from four months ago. However, the rising numbers of positive test results are a real cause for concern, and even more so if they are sustained beyond the phase of adaption to re-opening of society. Adherence to government policies that reduce viral spread is necessary to ensure that the second wave is controlled while balancing a return towards normality.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark J. Ponsford and David Smith for reading and commenting on this article.

Funding

Stephen Burgess is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant Number 204623/Z/16/Z). Dipender Gill is supported by the Wellcome Trust 4i Programme (203928/Z/16/Z) and British Heart Foundation Research Centre of Excellence (RE/18/4/34215) at Imperial College London. The sponsors had no role in the content of the manuscript or the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Contributorship statement: All authors conceived of this manuscript together and contributed to the original draft. All authors drafted the manuscript and have approved of the final submitted version.

Competing interest statement: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: DG is employed part-time by Novo Nordisk, outside of and unrelated to the submitted work.

Patient and Public Involvement: Patients and members of the public were not involved in the creation of the article.

Dissemination declaration: We plan to disseminate these findings with the general public on publication.

Data sharing

The manuscript does not contain primary data.

References

- 1.UK Government. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK: Healthcare. 2020. Available from https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/healthcare.

- 2.Chu DK. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to- person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golding N, et al. Reconstructing the global dynamics of under-ascertained COVID-19 cases and infections. medRxiv. 2020:2020.07.07.20148460. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01790-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birrell P, et al. Report on Nowcasting and Forecasting – 6th August 2020. 2020 Available from https://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/now-casting/report-on-nowcasting-and-forecasting-6th-august-2020/

- 5.Office of National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey pilot: England, 14 May 2020. 2020. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/england14may2020.

- 6.Office of National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey pilot: England and Wales, 4 September 2020. 2020. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/englandandwales4september2020.

- 7.Public Health England. Weekly Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Surveillance Report. Week 35. 2020 Available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/912973/Weekly_COVID19_Surveillance_Report_week_35_FINAL.PDF.

- 8.Riley S, et al. Resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 in England: detection by community antigen surveillance. medRxiv. 2020:2020.09.11.20192492 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jit M, et al. Estimating number of cases and spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using critical care admissions, United Kingdom, February to March 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(18):2000632. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aleta A, et al. Modelling the impact of testing, contact tracing and household quarantine on second waves of COVID-19. Nature Human Behaviour. 2020;4:964–971. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0931-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript does not contain primary data.