Abstract

Lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) is the sole enzyme known to degrade neutral lipids in the lysosome. Mutations in the LAL-encoding LIPA gene lead to rare lysosomal lipid storage disorders with complete or partial absence of LAL activity. This review discusses the consequences of defective LAL-mediated lipid hydrolysis on cellular lipid homeostasis, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. Early detection of LAL deficiency (LAL-D) is essential for disease management and survival. LAL-D must be considered in patients with dyslipidemia and elevated aminotransferase concentrations of unknown etiology. Enzyme replacement therapy, sometimes in combination with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), is currently the only therapy for LAL-D. New technologies based on mRNA and viral vector gene transfer are recent efforts to provide other effective therapeutic strategies.

LAL-mediated lipid hydrolysis

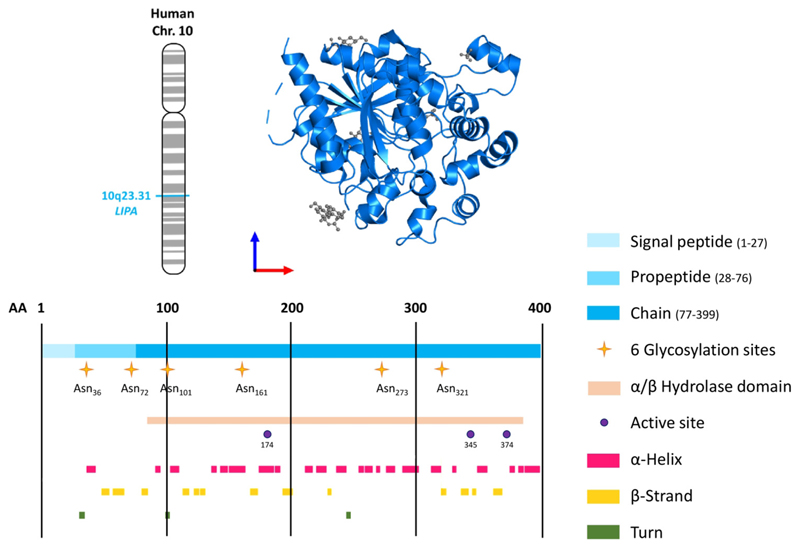

Upon receptor-mediated endocytosis, lipoprotein-associated cholesteryl esters (CEs) (see Glossary), triacylglycerols (TGs), diacylglycerols, monoacylglycerols, and retinyl esters are transported by endosomes to the lysosome, where they undergo hydrolysis by LAL at pH 3.9–5 to generate fatty acids (FAs), free cholesterol (FC), glycerol, and retinol [1]. LAL, encoded by the LIPA gene, is expressed by all cells except erythrocytes. LAL is a 399 amino acid protein of the α/β hydrolase fold family with a classical catalytic triad (Ser-174, Asp-345, His-374) cotranslationally glycosylated with mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) glycans [2]. Its crystal structure closely resembles that of the evolutionarily related gastric lipase [3] (Figure 1). The extent to which cytosolic lipid droplets (LDs) are degraded by LAL in the lysosome by lipophagy [4] is still elusive but likely depends on the nutritional state and cell type.

Glossary.

- Adeno-associated virus (AAV)

a small virus lacking pathogenicity but with mild immune response, making it an attractive candidate for creating viral vectors for gene therapy.

- Cholesteryl ester (CE)

neutral storage form of cholesterol in the core of a lipid droplet, a lipoprotein particle, or in the lysosome of lysosomal acid lipase-deficient cells.

- Cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD)

former name of the late-onset (childhood or adulthood) form of LAL deficiency.

- Dried-blood spot (DBS)

assay to diagnose lysosomal acid lipase deficiency.

- Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT)

treatment of enzymatic deficiencies or malfunctions by exogenous proteins.

- Fatty acid (FA)

a monocarboxylic acid with saturated or unsaturated aliphatic carbon chains.

- Free cholesterol (FC)

unesterified, free form of cholesterol.

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)

transplantation of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells, usually derived from bone marrow, into patients with dysfunctional or depleted bone marrow. In LAL-D, HSCT corrects lysosomal enzyme deficiency by engraftment of donor cells with the active enzyme.

- High-density lipoprotein (HDL)

smallest and densest lipoprotein with anti-atherosclerotic properties; critical for reverse cholesterol transport.

- Lipid droplet (LD)

a cytosolic organelle for transient lipid storage.

- Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

one of the five major groups of lipoproteins that predominantly transport cholesterol in the circulation; involved in the development of atherosclerosis.

- Low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)

important for the uptake of LDL (and VLDL-remnant) particles from the circulation.

- Lysosomal acid lipase (LAL)

an enzyme that hydrolyzes fatty acid-glycerol esters and cholesteryl esters in the lysosome at acidic pH.

- Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D)

a rare autosomal-recessive lysosomal storage disorder caused by a mutation in the LIPA gene.

- Mannose-6-phosphate (M6P)

tag bound by the M6P receptor to direct secreted proteins (e.g., LAL) from the Golgi to the lysosome.

- Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC)

lysosomal storage disease caused by mutations in the NPC1 and NPC2 genes.

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

a reversible condition characterized by >5% hepatic steatosis without inflammation and alcohol abuse.

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

subtype of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that also involves hepatic inflammation.

- Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)

transcription factor that regulates hepatic lipid metabolism and fatty acid oxidation.

- Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (PGC1α)

tissue-specific coactivator that enhances the activity of many nuclear receptors.

- Sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)

transcription factors that control endogenous fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis.

- Transcription factor EB (TFEB)

a transcription factor that controls lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy.

- Triacylglycerol (TG)

a major lipid class of dietary lipids; neutral lipid stored in the core of lipid droplets and lipoproteins that accumulates in lysosomes of lysosomal acid lipase-deficient cells.

- Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)

liver-derived plasma lipoprotein that transports lipids (predominantly triacylglycerols) from the liver to non-hepatic tissues.

- Wolman disease (WD)

former name of the early-onset (infant) form of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency.

Figure 1. Structure of human lysosomal acid lipase (LAL).

Upper panel: chromosomal location of the human LIPA gene and structure of the human LAL protein (residues 22–399, PDB 6v7n) viewed from the front. Lower panel: structural features of human LAL (Uniprot: P38571; 399 amino acids) including the six glycosylation sites, the α/β hydrolase fold, the active triad (Ser-174, Asp-345, His-374) [3], α-helices, and β-strands.

LAL may be released, at least from macrophages, upon fusion of the lysosome with the plasma membrane and act extracellularly in a lysosome-like environment (acidic synapse) [5], thereby participating in the degradation of modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [6]. LAL can also be secreted via the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi secretory pathway and subsequently reabsorbed by M6P receptor-mediated endocytosis. This phenomenon not only provides a treatment strategy for patients with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) but also explains a less severe phenotype of tissue-specific LAL-D mice [7,8].

This article summarizes the latest preclinical research findings on LAL-D, emphasizing the challenges in studying the secreted protein and underscoring the existing gaps in knowledge. Additionally, it aims to raise clinicians’ awareness of this rare disease by highlighting the diagnostic challenges and outlining current diagnostic procedures and criteria.

LAL regulation and regulatory role of LAL-derived lipids

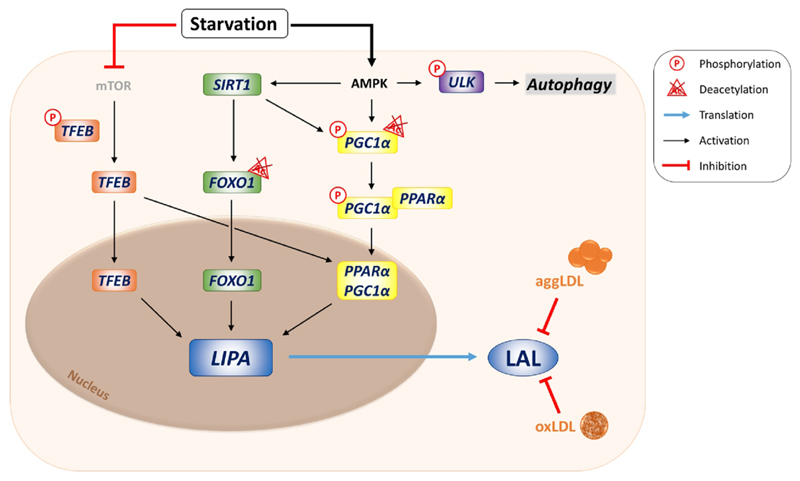

Lysosomes are unable to store any degradation products; therefore, their catabolic machinery (including LAL) and export mechanisms are constantly active. LAL is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level (Figure 2). Upon starvation, sirtuin 1 deacetylates forkhead box protein O1, which migrates to the nucleus and promotes LIPA transcription [9]. Moreover, transcription factor EB (TFEB) activates LIPA expression directly and indirectly via the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)–peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) cascade [10]. LAL does not rely on any cofactor for its enzymatic activity. At the post-transcriptional level, LAL is inhibited in macrophages by oxidized or aggregated LDL, probably by increasing lysosomal pH.

Figure 2. Transcriptional regulation of lysosomal acid lipase (LAL).

Upon nutrient starvation, mTOR inhibition results in the dephosphorylation of transcription factor EB (TFEB), which either directly or indirectly activates LIPA transcription via the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)–PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) cascade. Nutrient deprivation also activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), leading to activation of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), phosphorylation of PGC1α, and phosphorylation of the Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase (ULK1), the latter further activating the autophagic machinery. SIRT1 deacetylates PGC1α and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1), which initiate LIPA transcription in the nucleus together with TFEB. In macrophages, modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles like aggregated (agg) or oxidized (ox) LDL inhibit enzymatic activity of the LAL protein, presumably via raising lysosomal pH.

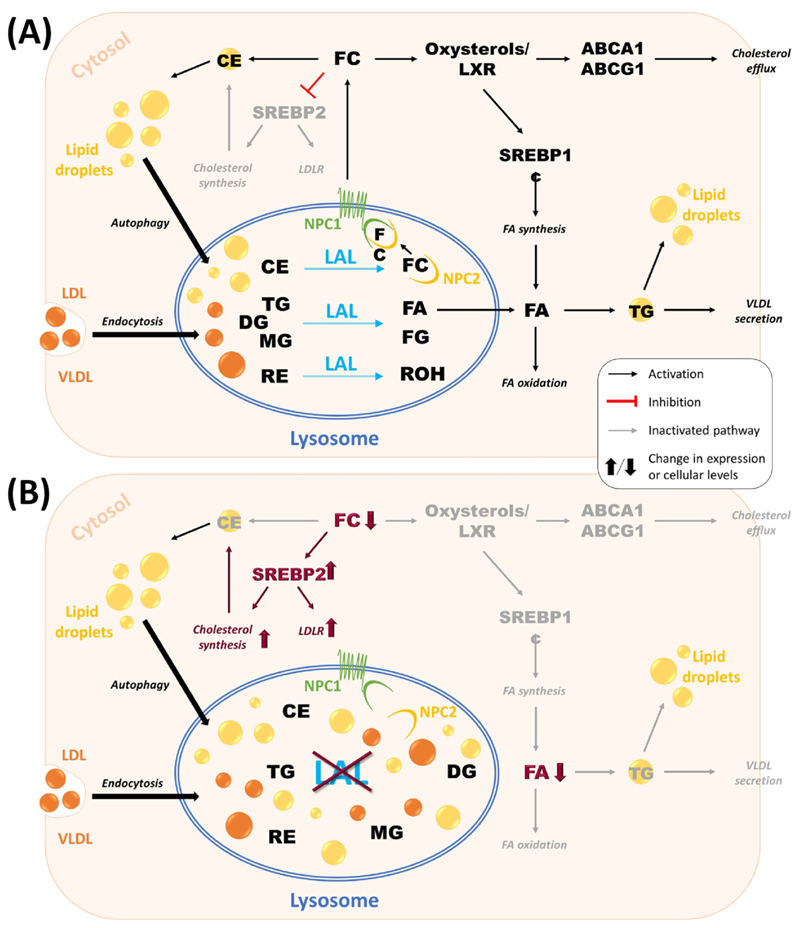

FA and FC, as the major hydrolytic products of LAL-mediated lipid degradation, serve as energy substrates, signaling molecules, and precursors for the biosynthesis of membranes, sterols, bile acids, and vitamin D (Figure 3, Key figure). In mouse models of LAL-D, impaired lysosomal FA release to the cytosol inactivates PPARγ, reduces the interaction of FA with PPARα and PGC1α, and diminishes peroxisomal FA oxidation [11,12].

Figure 3. The role of lysosomal acid lipase (LAL)-mediated lipid hydrolysis in cellular lipid homeostasis.

(A) In hepatocytes, low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis and cytosolic lipid droplets delivered via autophagy are essential sources of triacylglycerols (TGs) and cholesteryl esters (CEs) for lysosomal lipolysis by LAL. In addition, LAL hydrolyzes diacylglycerols (DGs), monoacylglycerols (MGs), and retinyl esters (REs) into free cholesterol (FC), fatty acids (FAs), free glycerol (FG), and retinol (ROH). FAs can either be used for FA oxidation and signaling pathways or become re-esterified to TG for very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion or storage in cytosolic lipid droplets. FC is exported from the lysosome via Niemann–Pick disease type C (NPC) 1 and 2 proteins and is further used for signaling pathways, storage in lipid droplets, or secretion in HDL particles. (B) Consequences of LAL-D on cellular lipid homeostasis. Absent or dysfunctional LAL results in accumulation of neutral lipids within the lysosome, leading to reduced availability of FC and FA for metabolic pathways. Diminished intracellular FA concentrations activate endogenous FA synthesis to maintain VLDL secretion. In turn, decreased availability of FC activates de novo cholesterol synthesis and stimulates LDL receptor (LDLR) expression to increase intracellular cholesterol concentrations. Abbreviation: SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein.

Whereas the exact mechanism of lysosomal FA export remains unclear, lysosomal FC export occurs via Niemann–Pick disease type C (NPC) 1 and 2 proteins. Once in the cytosol, FC interacts with sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) 2 to harness low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-mediated cholesterol uptake and repress HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of de novo cholesterol synthesis. Various cell types, including hepatocytes and macrophages, can efflux FC to high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) via ATP-binding cassette A1. In addition, FC is partially esterified to CE, which is secreted by hepatocytes in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles. In LAL-D, CE remains entrapped inside lysosomes, eventually increasing endogenous FA and cholesterol synthesis as well as VLDL secretion, and ultimately resulting in dyslipidemia [13].

LAL-D: epidemiology and disease presentation

Subtypes of LAL-D: early-onset (infant) and late-onset (adult) LAL-D

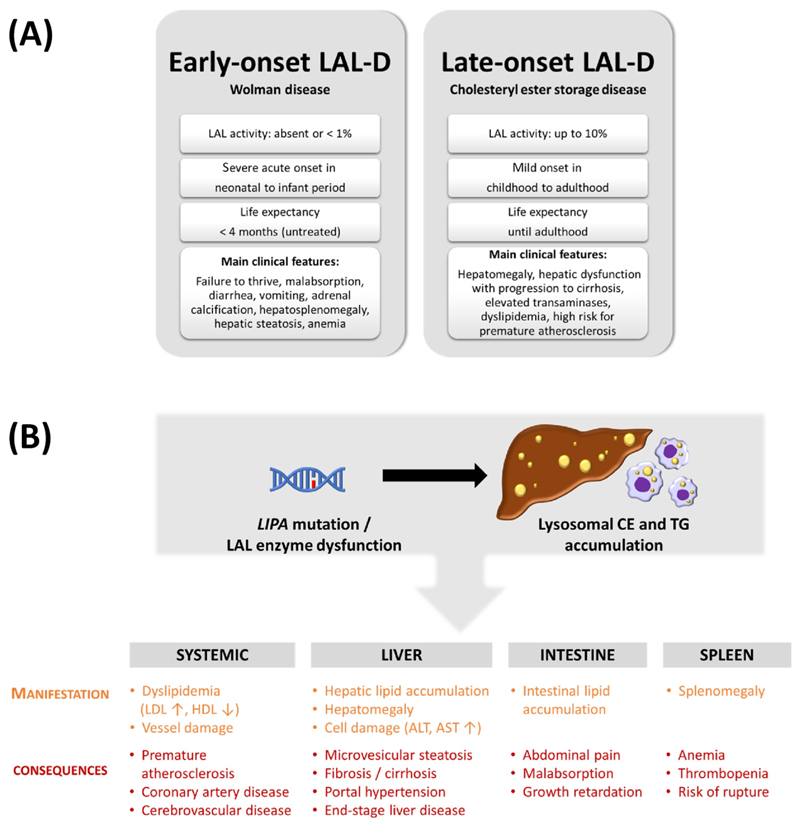

Mutations in the LIPA gene lead to LAL-D, a rare autosomal-recessive lysosomal storage disorder with major symptoms (see Clinician’s corner). LAL-D has two clinical manifestations of varying severity. Infants with early-onset LAL-D – formerly called Wolman disease (WD) [14] – have ≤1% LAL activity, whereas patients with childhood- or adult-onset LAL-D – formerly called cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD) – retain up to 10% enzymatic activity [15]. Both conditions share genetic, enzymatic, and clinical features (OMIM278000), including ectopic lysosomal lipid accumulation pre-dominantly in the liver, intestine, spleen, adrenal glands, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and macrophages [13] (Figure 4A), but the genotype-to-phenotype correlation has not been fully elucidated.

Clinician's corner.

LAL-D is an autosomal recessive-inherited condition caused by mutations in the LIPA gene. LAL is the sole enzyme responsible for the degradation of various neutral lipid species in lysosomes. Thus, loss of LAL activity causes lysosomal lipid accumulation of cholesteryl esters and triacylglycerols in cells and tissues throughout the body and typically results in liver disease in affected individuals.

Patients with early-onset (infantile) LAL-D (formerly called Wolman disease; residual LAL activity <1 %) die within the first few months of life, if left untreated. Early diagnosis is paramount for survival, and clinicians must be aware that LAL-D is a life-threatening disease that should be considered when patients present with dyslipidemia and liver abnormalities of unknown etiology. Patients with late-onset (childhood or adulthood) LAL-D (formerly called cholesteryl ester storage disease; up to 10% residual enzymatic activity) present with a discordant and unspecific clinical picture, including hepatomegaly, dyslipidemia, and increased aminotransferase (AST and ALT) concentrations, which complicates the diagnosis.

Rapid, cost-effective, and minimally invasive dried-blood spot testing is today’s gold standard for the diagnosis of LAL-D. Although the unspecific LAL inhibitors lalistat-1 and -2 also inhibit a variety of intracellular neutral lipid hydrolases, they can be used in LAL-D diagnosis because samples are assayed at acidic pH.

Reduced LAL activity was reported in individuals suffering from various forms of fatty liver disease. The connection between LAL-D and the development of premature atherosclerosis, however, is controversial. Genome-wide association studies identified LIPA as a risk locus for coronary artery disease. However, the increased rather than decreased LIPA expression in monocytes/macrophages from carriers of LIPA risk alleles raises the question of how altered LAL activity affects atherosclerosis.

Given the effects of statins on the upregulation of LDL receptors at the plasma membrane of hepatocytes, resulting in increased uptake of lipoprotein particles that remain entrapped in the lysosomes of LAL-D patients, their use remains controversial and is unlikely to provide benefit to LAL-D patients. Despite several limitations, such as incompatibility with egg proteins, formation of anti-drug antibodies and/or neutralizing antibodies, (bi) weekly intravenous infusions, lifelong treatment, and exorbitant costs, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with human recombinant LAL protein (sebelipase alfa, Kanuma®) is currently the most effective treatment for early-onset LAL-D patients. Multimodal therapy (dietary substrate reduction, ERT, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) has yielded promising results, with the prospect of discontinuation of ERT. Development of mixed peripheral leukocyte chimerism may present a limitation of this approach.

Figure 4. Main characteristics of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D).

(A) Biochemical and clinical characteristics of early- and late-onset LAL-D. (B) Clinical consequences of LAL-D. Mutations in the LIPA gene leading to enzymatic dysfunction of LAL cause lysosomal accumulation of neutral lipids, predominantly in liver and macrophages. Summary of systemic, hepatic, intestinal, and splenic symptoms associated with LAL-D. Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CE, cholesteryl ester; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triacylglycerol.

Characteristic clinical features of early-onset LAL-D include vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly, fatty liver, thickening of the small intestine, and enlargement of abdominal lymph nodes, stipple-like calcification of enlarged adrenal glands, and anemia [15]. Without timely diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis for LAL-D in infancy is poor with a median life expectancy of about 4 months [16].

Patients with late-onset LAL-D exhibit an extraordinarily wide variety of phenotypes, ranging from first symptom appearance during childhood, often reaching a fulminant course in early adolescence [17] to a diagnosis of LAL-D at age 80 years [18]. As the symptoms are largely unspecific, this may lead to a high rate of misdiagnosis [13,19] with no clear prognosis of life expectancy. The most common manifestations include elevated aminotransferases, dyslipidemia with low HDL levels, hepatosplenomegaly, occasional gastrointestinal disturbances, and impaired neuron myelination.

Due to insufficient data, the exact prevalence of LAL-D remains unknown and varies widely by geographical location and ethnicity, with a lower risk of LAL-D in the East and South Asian, Finnish, and Ashkenazi populations [20] and a higher risk in Caucasians and Hispanics. The overall prevalence of LAL-D was initially estimated to range from 1:40 000 to 1:300 000 individuals [13]. However, the number of diagnosed LAL-D cases is much lower than predicted likely due to misdiagnosis, as the clinical manifestations of LAL-D (Figure 4B) overlap with other disorders, such as Niemann–Pick disease type B or C, Gaucher disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), familial hypercholesterolemia, and Fredrickson type 2b hyperlipoproteinemia. Numerous examples of incidental diagnoses in asymptomatic patients [21,22], misdiagnoses [18,22], and inconsistent epidemiological and estimated prevalence [20,23] illustrate the discrepancy in accurately determining disease prevalence.

LIPA mutations in LAL-D

To date, 98 disease-causing and 22 predicted pathogenic mutations in the LIPA gene have been described in infant and adult LAL-D patients [20], with the c.894G>A exon 8 splice junction mutation (E8SJM) representing the most common variant (about 50% of all reported cases). Since this mutation encodes an enzyme with 2–4% residual activity, it is found only in adult LAL-D, with allele frequencies highest in Caucasians and Hispanics (approximately 1:300 each), translating to a predicted late-onset LAL-D prevalence of 1:130 000 in these populations. Because of early lethality, even fewer cases of infantile LAL-D are reported. To date, the null-mutations on exon 8, E8SJM-3 (c.892C>T) and E8SJM+1 (c.894+1G>A), have been identified most frequently in patients with early-onset LAL-D [24].

LAL-D diagnosis and screening

Diagnosis is particularly difficult in late-onset LAL-D due to lack of pathognomonic symptoms and shared pathology with other diseases (Figure 4B). When autosomal dominant inheritance can be excluded, the screening criteria recommend a rapid, cost-effective, and minimally invasive dried-blood spot (DBS) testing [25] as the gold standard for unequivocal diagnosis of LAL-D (< 5% of mean normal enzymatic activity) [13]. For DBS results between 5 and 10% mean normal enzymatic activity, repeated testing and molecular sequencing should be done before a definite diagnosis is made. DBS results >10% mean normal activity should be reported as ‘not affected’ [25]. The pharmacological inhibitor lalistat-2, which is routinely used to impede residual LAL activity in DBS assays, has recently been shown to additionally inhibit neutral lipases [26]. However, this lack of selectivity for LAL should not affect the diagnosis since the assay is performed at an acidic pH with a substrate that is unlikely to be cleaved by any other enzyme [27].

Several screening studies were conducted in populations predicted to be enriched in undiagnosed LAL-D patients, such as clinical manifestations of familial hypercholesterolemia without autosomal dominant inheritance and known genetic basis, or liver disease with chronically elevated transaminases of unknown etiology. Whereas some studies failed, others identified at least one LAL-D patient and led to additional LAL-D diagnoses by cascade screening of first relatives [28–31], justifying screening strategies through cost-effective DBS tests.

Model systems for LAL-D research

Pharmacological LAL inhibitors for in vitro studies

Pharmacological inhibition of LAL by lalistat-1 and -2 has been widely used to study enzyme function in vitro and to diagnose LAL-D in DBS assays. However, the doses of lalistat-1/2 most commonly used in preclinical research additionally inhibit a variety of neutral lipid hydrolases, including the major intracellular TG and CE hydrolases [26].

Mouse models for in vivo studies

Systemic LAL-D mice phenotypically resemble late-onset LAL-D based on their life expectancy of 1 year, despite complete loss of LAL activity [32,33]. In mice, HDL is the major cholesterol-carrying lipoprotein particle, and as chow diet contains only about 0.02% cholesterol, apolipoprotein B-CE burden is strongly attenuated in LAL-D mice compared to humans, which may reflect on the phenotype severity. Comparable to humans, LAL-D mice accumulate massive CE and TG and exhibit inflammation in multiple organs, rendering LAL-D mice an indispensable model to investigate the consequences of LAL-D. It has been shown in mice that LAL is involved in the supply of FA for thermogenesis [34,35] and endothelial cell proliferation in adipose tissue [36]. LAL affects VLDL secretion and insulin sensitivity [37], bile acid metabolism, gut microbiota and intestinal nutrient absorption [38], placental lipid homeostasis [39], and tumor development [12,40,41]. Results on whether overexpression of LAL in the liver has a beneficial effect on hepatic inflammation and steatosis are controversial [42,43]. A particular challenge in in vivo research is the ability of LAL as a secreted lysosomal enzyme to be taken up by some but not all [7,8,36] enzyme-deficient cells, which may lead to correction of LAL-D in certain tissue-specific LAL-D mouse models.

Preclinical studies addressing the role of LAL in atherosclerosis are scarce. Mice lacking LAL on the Ldlr-deficient background die within days of being fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet, whereas Lipa/ApoE-double knockout mice already develop plaques when fed chow diet and were not challenged with dietary cholesterol [44,45]. Recombinant human LAL reduced atherosclerosis in Ldlr-deficient mice, but the long-term effects of increased LAL activity on atherogenesis remain to be elucidated. The advantages and limitations of LAL-D mouse models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Advances and limitations of current LAL-D mouse models.

| Mutation/genotype | Advantages | Limitations | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Lipa KO; systemic LAL-D | Secretion and uptake of LAL into other cells/tissues excluded | Reflect early-onset (genetically) and later-onset (phenotypically) LAL-D | [32,33] |

| Liver-specific LIPA Tg; AAV-induced overexpression of human LIPA in hepatocytes | Allows studying the role of LAL in hepatocytes | No attenuation of steatosis and minor effects on neutral lipid composition | [42,43] |

| Liver-specific LIPA Tg; expression of human LIPA in hepatocytes | Human and murine LAL are functionally interchangeable | Human LAL is secreted into the circulation and affects distant organs | [103] |

| Myeloid-specific LIPA Tg; expression of human LIPA in myeloid cells of Lipa KO mice | Allows examining macrophage-specific LIPA expression in LAL-D | Other cells may take up secreted LAL to attenuate the phenotype | [104] |

| Adipose-specific LIPA Tg; expression of human LIPA in adipocytes | Beneficial LAL activation in obesity by reactivating thermogenesis | Lack of information on LAL protein levels or enzymatic activity | [35] |

| Hepatocyte-specific Lipa KO; LAL-D in hepatocytes | Consequences of LAL-D in hepatocytes | Effects of Kupffer cells and stellate cells not assessed | [7,8] |

| Endothelial cell-specific Lipa KO; LAL-D in endothelial cells of adult mice | Role of endothelial LAL in adipose tissues | Endothelial LAL deleted in various tissues; effect of factors released by endothelial cells due to lipoprotein processing unknown | [36] |

| Lipa/Ldlr DKO; systemic LAL-D on Ldlr KO background | Atherosclerotic backgrounds allow studying the consequences of LAL-D on | Die within days of being fed a high-fat diet | [44,45] |

| Lipa/ApoE DKO; systemic LAL-D on ApoEKO background | atherosclerosis | Develop plaques when fed chow; mice were not challenged with dietary fat | [44,45] |

The role of LAL in metabolic disease

LAL activity in atherosclerosis

Late-onset LAL-D patients often suffer from dyslipidemia, accelerated atherosclerosis, and early cardiovascular events leading to premature death if not outpaced by liver failure [19]. Whether cardiovascular disease develops secondarily as a consequence of dyslipidemia or whether molecular mechanisms at the cellular level disrupt vascular lipid and immune homeostasis and cause atherogenesis is unclear. Genome-wide association studies identified LIPA as a risk locus for coronary artery disease [46–48]. Risk alleles were not associated with reduced hepatic LIPA expression or plasma lipid levels, but paradoxically with elevated LIPA expression in monocytes and macrophages [31,49]. It remains controversial whether this translates to increased LAL protein expression and activity, and aggravation of atherosclerosis [49–51].

Infiltrating macrophages contribute significantly to the elevated LIPA expression detected in diseased arteries. The presence of extracellular LAL in atherosclerotic tissue [6] might potentiate lipid uptake by macrophage scavenger receptors, consequently leading to foam cell formation [5,52]. Moreover, increased lysosomal lipoprotein processing may exceed their cholesterol trafficking capacity, leading to disrupted lysosomal acidification and eventual arrest of the lysosomal machinery [52]. Re-acidification of lysosomes by nanoparticles could counteract the increase in lysosomal pH and thus represent a new therapeutic strategy for defective lysosomal function in atherosclerosis [53]. Lysosomal TG hydrolysis was also identified as a key driver of alternative macrophage activation [54], although the mechanisms described are controversial [55]. Further studies are required to delineate the consequences of elevated LAL expression on inflammation and macrophage function.

In contrast, loss of LAL in macrophages may negatively impact atherosclerosis through reduced oxysterol availability, which blunts liver X receptor-mediated signaling, leading to decreased cholesterol efflux [56,57], reverse cholesterol transport [58], and efferocytosis [57]. LAL may also influence immune response regulation [59,60] and lipid mediator synthesis [61]. Smooth muscle cells also participate in the cellular lipid storage in atheromata and have an even more pronounced pro-atherogenic phenotype due to their inherently low LAL abundance [62]. The interplay between lipoproteins and LAL in macrophages and smooth muscle cells and the effects on atherogenesis have been described elsewhere [31,52].

LAL activity in NAFLD

NAFLD encompasses a range of liver pathologies characterized by increased liver fat content without alcohol abuse, including liver steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [63]. DBS-LAL activity is decreased in adult NAFLD [64,65] and even more so in NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis [66,67]. In pediatric patients with NAFLD, decreased LAL activity was also associated with the severity of liver fibrosis [68].

Reduced DBS-LAL activity correlates with splenomegaly and fewer white blood cells and platelets in NAFLD and cirrhotic patients [69,70]. A cross-sectional study reported lower DBS-LAL activity in NAFLD patients with and without cirrhosis compared to patients with alcohol-related liver disease after platelet count adjustment. Of note, platelet but not leukocyte LAL activity was reduced in NAFLD patients [71]. Larger studies are needed to prove the potential of DBS-LAL activity as a noninvasive marker of NAFLD severity.

Therapeutic strategies

Therapeutic strategies depend on disease severity, with early-onset LAL-D requiring immediate treatment. The deterioration of the patients’ general condition by therapies limited to dietary fat reduction, parenteral nutrition, transfusions to correct anemia, and drug treatment of the patients’ acute condition suggest that these strategies are unsuccessful [16].

Pharmacological interventions

Late-onset LAL-D is usually characterized by elevated hepatic and circulating cholesterol levels, which became a therapeutic target. To improve cholesterol excretion, bile acid sequestrants combined with dietary fat reduction were among the first interventions in these patients. However, this therapy led to limited improvements [72] and the dose often could not be increased due to poor tolerability [21].

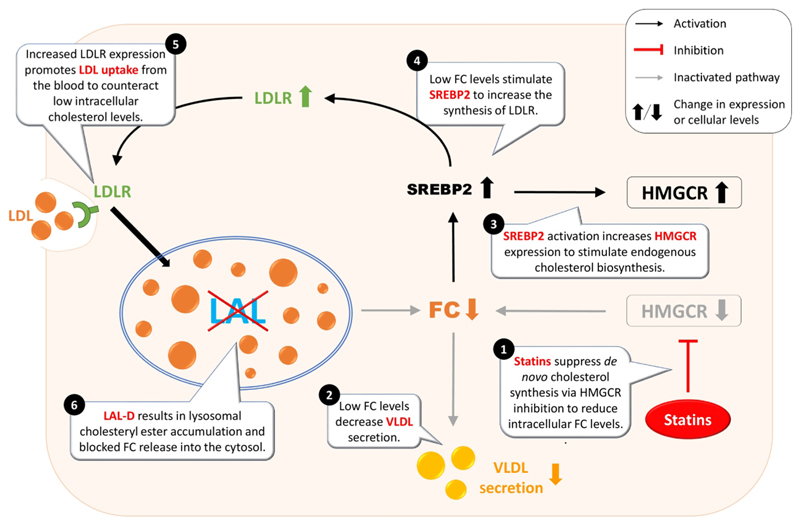

Statins, inhibitors of the rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis, entered the therapeutic field of late-onset LAL-D soon after bile acid sequestrants. Most but not all [73] early studies using lovastatin showed a reduction in circulating LDL-cholesterol without worsening of liver function; a combination therapy with bile acid sequestrants had an additive effect on lowering plasma lipids [74]. The use of statins, however, may come at a price. By partially blocking de novo cholesterol synthesis, reduced cytosolic FC levels lead to a compensatory elevation in LDLR expression [75,76]. Endocytosed lipoprotein-derived CEs remain entrapped in the lysosomes of LAL-D patients, creating a vicious circle that attenuates the circulating cholesterol load but exacerbates hepatic lipid deposition [13] (Figure 5). A retrospective literature study failed to identify a single LAL-D patient treated with statins without worsening liver pathology on consecutive liver biopsies [19]. In contrast, normalization of lipid profile and liver enzymes after almost two decades of statin therapy has recently been reported [77]. Considering that even siblings suffering from late-onset LAL-D may respond differently to statins [72], their use remains controversial [13,19,78] and is unlikely to be beneficial for all LAL-D patients [13,19].

Figure 5. Potential problems of statin treatment in lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) patients.

In addition to the enzymatic dysfunction and the associated accumulation of cholesteryl esters in the lysosome but lower intracellular concentrations of free cholesterol (FC) in LAL-D, statin treatment further reduces the intracellular availability of FC. This creates a vicious cycle in which the cell tries in vain to maintain cholesterol homeostasis. ① Statin treatment inhibits de novo cholesterol synthesis through blocking the rate-limiting enzyme HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR). ② Reduced cholesterol availability attenuates very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion and lowers circulating cholesterol levels. ③ Decreased cellular cholesterol levels also lead to activation of sterol-regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) and compensatory upregulation of HMGCR to sustain cellular cholesterol homeostasis, but this is inhibited by statins. ④ In addition, activation of SREBP2 results in increased low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) synthesis, causing ⑤ increased clearance of LDL from the circulation and uptake of LDL by the liver. ⑥ Endocytosed LDL remains entrapped within the lysosome and exacerbates hepatic lipid deposition and liver disease in LAL-D.

Ezetimibe, an inhibitor of NPC1-like 1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption, is considered efficient and safe in reducing LDL-cholesterol levels, and has been used in treatment of LAL-D patients as a combination therapy with statins [77,79,80], replacing the less well-tolerated bile acid sequestrants. The clinical results of a single patient treated with ezetimibe as monotherapy for substrate reduction suggested that there may be no additive beneficial effect of statin use in late-onset LAL-D patients [79]. However, further studies are required to support these findings.

Liver transplantation

Several case reports described the necessity of liver transplantation in adult LAL-D patients, resulting in immediate normalization of the lipoprotein profile and partial rescue of the systemic phenotype due to cross-correction (i.e., LAL secretion from healthy hepatocytes and LAL uptake by peripheral enzyme-deficient cells). Successful engraftment and almost complete recovery were reported in individual cases with up to 8 years of follow-up [81]. However, liver-transplanted patients showed continued lipid deposition in peripheral tissues, progression of vascular lipid accumulation, renal failure, and in some cases a paradoxical recurrence of LAL-D pathology in allografts, leading to lethal outcomes [17]. These data suggest that restoring liver LAL activity is not enough for ameliorating systemic pathology.

Enzyme replacement therapy

Treatment options for LAL-D drastically changed with the development of human recombinant LAL protein (sebelipase alfa, Kanuma®) as enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) [82]. This glycoprotein is likely taken up by mannose and M6P receptors [83,84], but the detailed tissue biodistribution has not yet been reported. In patients with late-onset LAL-D, the most striking effects were a normalization of liver transaminase levels and a marked decrease in LDL-cholesterol [83,85] that persisted for at least 5 years [86]. Despite reductions in liver volume, steatosis, and fibrosis, the results were inconsistent and in individual cases even displayed worsening of fibrosis and lobular inflammation on subsequent biopsies [87,88]. Survival rates in early-onset LAL-D patients were very high for at least 5 and up to at least 10 years of ERT [89,90] with main improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, growth, and transaminase levels. Early initiation of ERT is vital for favorable outcomes [89], given that hepatic pathology occurs already in fetuses affected by LAL-D [91]. A clinical study is currently recruiting patients to address the safety and efficacy of in utero LAL delivery (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04532047).

Adverse effects of mild to moderate severity were reported in almost all treated patients, whereas severe side effects were rare and more frequent in younger populations [86–88,90]. Anti-drug antibodies [87] were particularly common in patients with early-onset LAL-D, who frequently developed neutralizing antibodies that required dose adjustment [90,92]. Additional limitations of ERT include egg allergies, repeated intravenous infusions [(bi)weekly hospital visits, 2 h intravenous administration], likely a lifetime treatment [83], and exorbitant costs [93].

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Initial HSCTs were largely unsuccessful, presumably because of liver toxicity by chemotherapeutics during the conditioning [94,95]. The long turnover time of tissue macrophages (>1 year for liver macrophages) [96] may have prevented favorable outcomes. Nevertheless, four patients survived beyond the first year of life [95,97,98] with remarkable improvements at the time of the last available report. Another four patients on multimodal therapy (dietary substrate reduction, ERT, followed by HSCT) also showed promising results albeit all but one developed substantial mixed peripheral leukocyte chimerism; these continued to be treated with ERT on less frequent and much lower doses than before HSCT [99]. Although future studies are needed to guarantee the safety of above-average LAL expression, the inclusion of gene therapy-treated autologous transplants in a multimodal treatment regimen may provide the best clinical outcomes for LAL-D patients. This combination should avoid graft rejection and ensure immunogenic tolerance of ERT, with the prospect of discontinuing ERT once the condition has stabilized [99,100].

Alternative treatments in the future

Vector-based therapies in LAL-D mice may represent a great hope for future therapeutic strategies. One-time adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated gene therapy has been proposed as a viable treatment alternative [101] and may help to target LIPA expression in multiple organs where ERT is less effective, at least in later-onset LAL-D. In addition, mRNA technology could be an effective tool for incorporating an active LAL protein into the cell. Biodistribution of both lipid- and polymer-based nanocarriers has already resulted in preferential biodistribution and expression in major organs for which mRNA-based drugs show promise [102]. LIPA mRNA sequence might be engineered to achieve increased protein expression and specific localization. Further development of safe and efficient nanocarriers for effective in vivo delivery of high levels of enzymatically active LAL to hepatocytes and/or macrophages remains to be adequately explored. Acidic nanoparticles as drug delivery vehicles to restore lysosomal pH [53] should be further developed to entrap LAL and introduce it into dysfunctional lysosomes. This approach may provide a therapeutic opportunity through combined lysosomal acidification followed by functional lipid hydrolysis by LAL.

Concluding remarks

LAL is vital as the sole neutral lipid hydrolase in lysosomes and its complete deficiency is fatal. Patients with residual LAL activity of >5% are more prone to develop NAFLD, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and atherosclerosis. It is of the utmost importance that clinicians be aware of LAL-D as a differential diagnosis for selected patients. Cost-effective DBS testing of LAL activity should be performed whenever individuals present with dyslipidemia (i.e., elevated LDL cholesterol, decreased HDL cholesterol) and liver abnormalities like hepatomegaly and elevated aminotransferases of unknown etiology. Future studies are needed to evaluate DBS-LAL activity as a potential biomarker for NAFLD (see Outstanding questions). Despite the proven efficacy and tolerability of ERT, serious side effects and exorbitant costs argue for seeking new treatment strategies. Future improvements in mRNA- and vector-based technologies, as well as nanoparticle delivery of LAL to lysosomes for enhanced lipid degradation will open therapeutic opportunities that may hold the key to better treatments for LAL-D with long-lasting effects.

Outstanding questions.

Which cells and tissues are capable of secreting LAL, and which cells can take up the secreted enzyme in active form?

Why is LAL-D cross-correction after liver transplantation unsuccessful despite profound hepatocyte LAL activity, and why do some patients experience LAL-D recurrence in the allograft?

Do LIPA risk alleles for coronary artery disease with increased LIPA expression in macrophages translate into increased LAL activity? Does increased LIPA expression in monocytes and macrophages lead to increased atherosclerosis, and what are the consequences of increased LAL activity in other cells? In which direction and to what extent can extracellular LAL-mediated degradation of modified LDL affect atherogenesis?

Do cardiovascular diseases develop secondarily as a consequence of dyslipidemia in LAL-D or do molecular mechanisms at the cellular level disrupt vascular lipid and immune homeostasis and cause atherogenesis in LAL-D patients?

What is the definitive role of LAL in NAFLD? Can LAL activity determined by dried blood spot tests be used as a noninvasive marker of NAFLD severity?

What is the potential of alternative technologies based on mRNA, acidic nanoparticles, or viral vectors for delivering LAL in its active form to all affected tissues, and could they represent new, effective, and affordable therapies for LAL-D with fewer side effects than the current enzyme replacement therapy?

Highlights.

Mutations in the LIPA gene cause LAL deficiency (LAL-D), a rare autosomal-recessive multiorgan condition with fatal outcome if residual lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) activity is below 1%.

Early diagnosis is key in early-onset LAL-D, and the rapid, cost-effective, and minimally invasive dried-blood spot test is today’s gold standard for diagnosis.

Despite several limitations, enzyme replacement therapy with human recombinant LAL protein is currently the most effective treatment for LAL-D. Gene-therapy-treated autologous transplants in combination with dietary fat reduction and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may provide the best clinical outcomes for patients by avoiding graft rejection and ensuring immunogenic tolerance of LAL.

Although commonly used concentrations inhibit a number of intracellular neutral lipid hydrolases, lalistat1 or -2 can still be used in LAL-D diagnosis as samples are assayed at acidic pH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (SFB F73, P32400, DP-iDP DOC 31, DK-MCD W1226, P30882), the Province of Styria, the City of Graz, and the PhD program ‘Molecular Medicine’ of the Medical University of Graz.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

No interests are declared.

References

- 1.Zechner R, et al. Cytosolic lipolysis and lipophagy: two sides of the same coin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:671–684. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zschenker O, et al. Systematic mutagenesis of potential glycosylation sites of lysosomal acid lipase. J Biochem. 2005;137:387–394. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajamohan F, et al. Crystal structure of human lysosomal acid lipase and its implications in cholesteryl ester storage disease[S] J Lipid Res. 2020;61:1192–1202. doi: 10.1194/jlr.RA120000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh R, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haka AS, et al. Macrophages create an acidic extracellular hydrolytic compartment to digest aggregated lipoproteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4932–4940. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakala JK, et al. Lysosomal enzymes are released from cultured human macrophages, hydrolyze LDL in vitro, and are present extracellularly in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1430–1436. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000077207.49221.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leopold C, et al. Hepatocyte-specific lysosomal acid lipase deficiency protects mice from diet-induced obesity but promotes hepatic inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864:500–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pajed L, et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of lysosomal acid lipase leads to cholesteryl ester but not triglyceride or retinyl ester accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:9118–9133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lettieri Barbato D, et al. FoxO1 controls lysosomal acid lipase in adipocytes: implication of lipophagy during nutrient restriction and metformin treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e861. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel R, et al. Induction of lysosomal biogenesis in atherosclerotic macrophages can rescue lipid-induced lysosomal dysfunction and downstream sequelae. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1942–1952. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan HWS, et al. Lysosomal inhibition attenuates peroxisomal gene transcription via suppression of PPARA and PPARGC1A levels. Autophagy. 2019;15:1455–1459. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1609847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao T, et al. Critical role of PPARy in myeloid-derived suppressor cell-stimulated cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1529–1543. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiner Z, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency - an under-recognized cause of dyslipidaemia and liver dysfunction. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramov A, et al. Generalized xanthomatosis with calcified adrenals. AMA J Dis Child. 1956;91:282–286. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1956.02060020284010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pericleous M, et al. Wolman's disease and cholesteryl ester storage disorder: the phenotypic spectrum of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:670–679. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones SA, et al. Rapid progression and mortality of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency presenting in infants. Genet Med. 2016;18:452–458. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein DL, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency allograft recurrence and liver failure-clinical outcomes of 18 liver transplantation patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;124:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisciotta L, et al. Cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD) due to novel mutations in the LIPA gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein DL, et al. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: review of the findings in 135 reported patients with an underdiagnosed disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1230–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter A, et al. The global prevalence and genetic spectrum of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: a rare condition that mimics NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2019;70:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iverson SA, et al. Asymptomatic cholesteryl ester storage disease in an adult controlled with simvastatin. Ann Clin Biochem. 1997;34:433–436. doi: 10.1177/000456329703400418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasche C, et al. A novel variant of lysosomal acid lipase in cholesteryl ester storage disease associated with mild phenotype and improvement on lovastatin. J Hepatol. 1997;27:744–750. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Angel G, et al. Large-scale functional LIPA variant characterization to improve birth prevalence estimates of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:2007–2020. doi: 10.1002/humu.23837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson RA, et al. Mutations at the lysosomal acid cholesteryl ester hydrolase gene locus in Wolman disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2718–2722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukacs Z, et al. Best practice in the measurement and interpretation of lysosomal acid lipase in dried blood spots using the inhibitor Lalistat 2. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;471:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradic I, et al. Off-target effects of the lysosomal acid lipase inhibitors Lalistat-1 and Lalistat-2 on neutral lipid hydrolases. Mol Metab. 2022;61:101510. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton J, et al. Anew method for the measurement of lysosomal acid lipase in dried blood spots using the inhibitor Lalistat 2. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1207–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sustar U, et al. Early discovery of children with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency with the Universal Familial Hypercholesterolemia Screening Program. Front Genet. 2022;13:936121. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.936121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chora JR, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: a hidden disease among cohorts of familial hypercholesterolemia? J. Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:477–484.:e472. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pullinger CR, et al. Identification and metabolic profiling of patients with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:716–726.:e711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Besler KJ, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: a rare inherited dyslipidemia but potential ubiquitous factor in the development of atherosclerosis and fatty liver disease. Front Genet. 2022;13:1013266. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.1013266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du H, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse lysosomal acid lipase gene: long-term survival with massive cholesteryl ester and triglyceride storage. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1347–1354. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du H, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase-deficient mice: depletion of white and brown fat, severe hepatosplenomegaly, and shortened life span. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:489–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duta-Mare M, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase regulates fatty acid channeling in brown adipose tissue to maintain thermogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018;1863:467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamblin C, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase drives adipocyte cholesterol homeostasis and modulates lipid storage in obesity, independent of autophagy. Diabetes. 2021;70:76–90. doi: 10.2337/db20-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer AW, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase promotes endothelial proliferation in cold-activated adipose tissue. Adipocyte. 2022;11:28–33. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2021.2013416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radovic B, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase regulates VLDL synthesis and insulin sensitivity in mice. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1743–1752. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3968-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sachdev V, et al. Impaired bile acid metabolism and gut dysbiosis in mice lacking lysosomal acid lipase. Cells. 2021;10:2619. doi: 10.3390/cells10102619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuentzel KB, et al. Defective lysosomal lipolysis causes prenatal lipid accumulation and exacerbates immediately after birth. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:10416. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase promotes cholesterol ester metabolism and drives clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression. Cell Prolif. 2018;51:e12452. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao T, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase, CSF1R, and PD-L1 determine functions of CD11c+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e156623. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.156623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopresti MW, et al. Hepatic lysosomal acid lipase overexpression worsens hepatic inflammation in mice fed a Western diet. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100133. doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li F, et al. Hepatic lysosomal acid lipase drives the autophagy-lysosomal response and alleviates cholesterol metabolic disorder in ApoE deficient mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2021;1866:159027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.159027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du H, Grabowski GA. Lysosomal acid lipase and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15:539–544. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200410000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du H, et al. Reduction of atherosclerotic plaques by lysosomal acid lipase supplementation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:147–154. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000107030.22053.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wild PS, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies LIPA as a susceptibility gene for coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:403–412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.IBC 50K CAD Consortium et al. Large-scale gene-centric analysis identifies novel variants for coronary artery disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coronary Artery Disease (C4D) Genetics Consortium. A genome-wide association study in Europeans and South Asians identifies five new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Reilly MP. LIPA Variants in genome-wide association studies of coronary artery diseases: loss-of-function or gain-of-function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1015–1017. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris GE, et al. Coronary artery disease-associated LIPA coding variant rs1051338 reduces lysosomal acid lipase levels and activity in lysosomes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1050–1057. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans TD, et al. Functional characterization of lipa (lysosomal acid lipase) variants associated with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:2480–2491. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dubland JA, Francis GA. Lysosomal acid lipase: at the crossroads of normal and atherogenic cholesterol metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:3. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, et al. Use of acidic nanoparticles to rescue macrophage lysosomal dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Autophagy. 2022;19:886–903. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2022.2108252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang SC, et al. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:846–855. doi: 10.1038/ni.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura M, et al. Fatty acid oxidation in macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:216–217. doi: 10.1038/ni.3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ouimet M, et al. Autophagy regulates cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells via lysosomal acid lipase. Cell Metab. 2011;13:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viaud M, et al. Lysosomal cholesterol hydrolysis couples efferocytosis to anti-inflammatory oxysterol production. Circ Res. 2018;122:1369–1384. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowden KL, et al. LAL (lysosomal acid lipase) promotes reverse cholesterol transport in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1191–1201. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li F, Zhang H. Lysosomal acid lipase in lipid metabolism and beyond. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:850–856. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yvan-Charvet L, et al. Immunometabolic function of cholesterol in cardiovascular disease and beyond. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:1393–1407. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlager S, et al. Lysosomal lipid hydrolysis provides substrates for lipid mediator synthesis in murine macrophages. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40037–40051. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dubland JA, et al. Low LAL (lysosomal acid lipase) expression by smooth muscle cells relative to macrophages as a mechanism for arterial foam cell formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:e354–e368. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.316063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown GT, Kleiner DE. Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Metabolism. 2016;65:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baratta F, et al. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. eBioMedicine. 2015;2:750–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shteyer E, et al. Low serum lysosomal acid lipase activity correlates with advanced liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:312. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baratta F, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase activity and liver fibrosis in the clinical continuum of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2019;39:2301–2308. doi: 10.1111/liv.14206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gravito-Soares M, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase: can it be a new non-invasive serum biomarker of cryptogenic liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:78–88. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selvakumar PK, et al. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity - a potential role in the pathogenesis of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatric patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Angelico F, et al. Severe reduction of blood lysosomal acid lipase activity in cryptogenic cirrhosis: a nationwide multicentre cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2017;262:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, et al. Platelet count may impact on lysosomal acid lipase activity determination in dried blood spot. Clin Biochem. 2017;50:726–728. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferri F, et al. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity in blood and platelets is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00116. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glueck CJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of treatment of pediatric cholesteryl ester storage disease with lovastatin. Pediatr Res. 1992;32:559–565. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Bisceglie AM, et al. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: hepatopathology and effects of therapy with lovastatin. Hepatology. 1990;11:764–772. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yokoyama S, McCoy E. Long-term treatment of a homozygous cholesteryl ester storage disease with combined cholestyramine and lovastatin. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:291–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01799650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levy R, et al. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: complex molecular effects of chronic lovastatin therapy. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1005–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ginsberg HN, et al. Suppression of apolipoprotein B production during treatment of cholesteryl ester storage disease with lovastatin Implications for regulation of apolipoprotein B synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:1692–1697. doi: 10.1172/JCI113259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cameron SJ, et al. A case of abdominal pain with dyslipidemia: difficulties diagnosing cholesterol ester storage disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2628–2633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Block RC, Razani B. Options to consider when treating lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1280–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Di Rocco M, et al. Long term substrate reduction therapy with ezetimibe alone or associated with statins in three adult patients with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0768-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tadiboyina VT, et al. Treatment of dyslipidemia with lovastatin and ezetimibe in an adolescent with cholesterol ester storage disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2005;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sreekantam S, et al. Successful long-term outcome of liver transplantation in late-onset lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2016;20:851–854. doi: 10.1111/petr.12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burton BK, et al. A Phase 3 trial of sebelipase alfa in lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1010–1020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Balwani M, et al. Clinical effect and safety profile of recombinant human lysosomal acid lipase in patients with cho lesteryl ester storage disease. Hepatology. 2013;58:950–957. doi: 10.1002/hep.26289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coutinho MF, et al. Mannose-6-phosphate pathway: a review on its role in lysosomal function and dysfunction. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valayannopoulos V, et al. Sebelipase alfa over 52 weeks reduces serum transaminases, liver volume and improves serum lipids in patients with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malinova V, et al. Sebelipase alfa for lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: 5-year treatment experience from a phase 2 open-label extension study. Liver Int. 2020;40:2203–2214. doi: 10.1111/liv.14603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burton BK, et al. Sebelipase alfa in children and adults with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: final results of the ARISE study. J Hepatol. 2022;76:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Burton BK, et al. Long-term sebelipase alfa treatment in children and adults with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022;74:757–764. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Demaret T, et al. Sebelipase alfa enzyme replacement therapy in Wolman disease: a nationwide cohort with up to ten years of follow-up. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:507. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-02134-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vijay S, et al. Long-term survival with sebelipase alfa enzyme replacement therapy in infants with rapidly progressive lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: final results from 2 open-label studies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:13. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01577-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Desai PK, et al. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: pathologic changes in an affected fetus. Am J Med Genet. 1987;26:689–698. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jones SA, et al. Survival in infants treated with sebelipase Alfa for lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: an openlabel, multicenter, dose-escalation study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:25. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0587-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Recommendation CCDEC. CADTH Canadian Drug Expert Committee Recommendation: Sebelipase alfa (Kanuma - Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc): Indication: Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. CADTH Common drug reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Krivit W, et al. Wolman disease successfully treated by bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:567–570. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tolar J, et al. Long-term metabolic, endocrine, and neuropsychological outcome of hematopoietic cell transplantation for Wolman disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:21–27. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gramatges MM, et al. Pathological evidence of Wolman's disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation despite correction of lysosomal acid lipase activity. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:449–450. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stein J, et al. Successful treatment of Wolman disease by unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:663–666. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jayakumar I, et al. Successful matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for infantile Wolman disease. Pediatr Hematol Oncol J. 2023;8:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Potter JE, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a new paradigm of treatment in Wolman disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:235. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01849-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lum SH, et al. Outcome of haematopoietic cell transplantation in children with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: a study on behalf of the EBMT Inborn Errors Working Party. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41409-023-01918-4. Published online February 14, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lam P, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of rscAAVrh74. miniCMV.LIPA gene therapy in a mouse model of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;26:413–426. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zadory M, et al. Current knowledge on the tissue distribution of mRNA nanocarriers for therapeutic protein expression. Biomater Sci. 2022;10:6077–6115. doi: 10.1039/d2bm00859a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Du H, et al. Hepatocyte-specific expression of human lysosome acid lipase corrects liver inflammation and tumor metastasis in lal-/- mice. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2379–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yan C, et al. Macrophage-specific expression of human lysosomal acid lipase corrects inflammation and pathogenic phenotypes in lal-/- mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:916–926. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]