Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance is impacting treatment decisions for, and patient outcomes from, bacterial infections worldwide, with particular threats from infections with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumanii, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Numerous areas of clinical uncertainty surround the treatment of these highly resistant infections, yet substantial obstacles exist to the design and conduct of treatment trials for carbapenem-resistant bacterial infections. These include the lack of a widely acceptable optimised standard of care and control regimens, varying antimicrobial susceptibilities and clinical contraindications making specific intervention regimens infeasible, and diagnostic and recruitment challenges. The current single comparator trials are not designed to answer the urgent public health question, identified as a high priority by WHO, of what are the best regimens out of the available options that will significantly reduce morbidity, costs, and mortality. This scenario has an analogy in network meta-analysis, which compares multiple treatments in an evidence synthesis to rank the best of a set of available treatments. To address these obstacles, we propose extending the network meta-analysis approach to individual randomisation of patients. We refer to this approach as a Personalised RAndomised Controlled Trial (PRACTical) design that compares multiple treatments in an evidence synthesis, to identify, overall, which is the best treatment out of a set of available treatments to recommend, or how these different treatments rank against each other. In this Personal View, we summarise the design principles of personalised randomised controlled trial designs. Specifically, of a network of different potential regimens for life-threatening carbapenem-resistant infections, each patient would be randomly assigned only to regimens considered clinically reasonable for that patient at that time, incorporating antimicrobial susceptibility, toxicity profile, pharmacometric properties, availability, and physician assessment. Analysis can use both direct and indirect comparisons across the network, analogous to network meta-analysis. This new trial design will maximise the relevance of the findings to each individual patient, and enable the top-ranked regimens from any personalised randomisation list to be identified, in terms of both efficacy and safety.

Introduction

Broad-spectrum multidrug resistance is impacting treatment decisions for, and patient outcomes from, bacterial infections worldwide, particularly in Asia and southern Europe. Infections with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumanii, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the clearest threat, with multiple documented mechanisms of carbapenem resistance.1 Many of these mechanisms co-occur with resistance to multiple antibiotic classes and are spread by mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, which facilitate their spread. This mechanism leads to mosaic patterns of resistance, requiring personalisation of antibiotic therapy guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Numerous areas of clinical uncertainty surround the treatment of these highly resistant infections, particularly because in-vitro data (eg, from hollow-fibre models) suggest that antibiotic combinations might be synergistic2 or antagonistic.3 The situation is made more complex by a lack of standardisation of in-vitro pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK–PD) models and dose-optimisation methods for single-antibiotic drug development programmes,4 recently highlighted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (North Bethesda, MD, USA).5,6 There is further lack of clarity on the relationship between in-vitro data and clinical outcomes for combination therapies. Outstanding questions, highlighted in recent reviews,7–11 include whether high-dose carbapenems might overcome low-level resistance, whether old, potentially toxic drugs, (such as colistin) are more effective in combination with other drugs, and whether alternative drugs synergistically increase antimicrobial potency (for example, polymyxin B plus zidovudine).12

Randomised controlled trials provide the most robust evidence regarding the relative effectiveness of different therapeutic options.13 However, despite the plethora of questions, there are few randomised trials in carbapenem-resistant infections to provide clear answers. Clinical practice is currently guided by retrospective observational cohort studies, such as the INCREMENT study, where combination therapy was associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients at high risk of infection.14 The challenges of doing randomised controlled trials are illustrated by the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval in 2018 of plazomicin on the basis of the CARE trial, which screened 2000 adults and randomly assigned only 39 over 2 years.15 Of note, the parallel trial of plazomicin versus meropenem (EPIC), for complicated urinary tract infection recruited 609 adults but had 0·2% mortality overall,16 compromising extrapolation to more serious infections. One of the largest trials in carbapenem-resistant infections to date randomised 406 adults to colistin monotherapy or colistin plus meropenem.17 Although overall the trial found no evidence of benefit from colistin plus meropenem, clinical failures by 14 days were numerically lower in the combination group (risk ratio 0·93 [95% CI 0·83–1·03]). A further challenge for comparative clinical efficacy studies is the future pipeline of antibiotics active against carbapenem-resistant infections.18 The great majority of compounds currently in phase 1 trials are active only against specific pathogens or resistance mutations, making broader comparisons of efficacy even more problematic.

In a traditional two-arm or multiarm trial, eligible patients are randomly assigned between control and all intervention regimens. There is no accepted optimal standard of care regimen that can be used as a control regimen for carbapenem-resistant infections. Moreover, any specific regimen might be contraindicated or unavailable for many patients with carbapenem-resistant infections for different reasons, greatly restricting eligibility and recruitment. For example, the antimicrobial susceptibility of the infecting organism or the patient’s condition (eg, renal impairment) might contraindicate either the control or intervention regimen.

These factors make it hard to find any two specific regimens that most patients meeting other inclusion criteria could be randomly assigned to, even though physicians might have many questions regarding an individual patient’s treatment. These problems make conventional trial designs difficult, including platform designs, which maintain a control group over a longer period of time, against which different intervention regimens are compared, with the control potentially changing if a more effective regimen is identified.19,20

What is the clinical question?

Faced with a severely unwell patient with a life-threatening carbapenem-resistant infection (with a probable mortality ≥10–20%), the clinician needs to know, out of the several different possible regimens (including combinations) that could be prescribed, which will provide the greatest probability of success (cure). Given the high mortality associated with such infections, we argue that absolute confidence in identifying the best regimen is less important than avoiding the worst regimens. That is, choosing a regimen that is likely to be one of the better available options at that time for the individual patient is more important than choosing the perfect regimen. These are the clinical compromises that physicians make continuously: personalising decisions for each individual patient, while balancing efficacy, toxicity, resistance, availability, and cost.

This scenario has an analogy in network meta-analysis,21 which compares multiple treatments in an evidence synthesis, to identify, overall, what is the best treatment out of a set of available treatments to recommend, or how these different treatments rank against each other. The difference is that in network meta-analysis the unit is a randomised controlled trial, directly comparing two or more regimens (potentially with different control comparators). The statistical challenge is ensuring that the individual pairwise within-trial comparisons are pooled together into a coherent comparison of outcomes, taking into account uncertainty within each individual trial and between-trial variation. Much theoretical work has gone into determining the best statistically principled methods to make indirect inferences about the relative performance of different regimens across the network,22,23 even when these regimens might not have been compared directly within any individual randomised controlled trial.

A new trial design

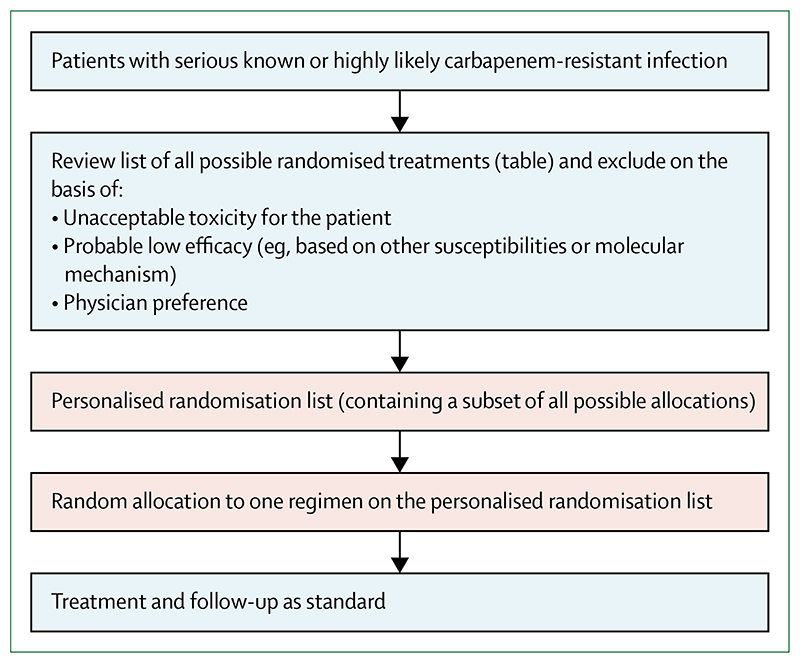

We propose to use and extend the network meta-analysis approach to individual randomisation of patients in what we term a Personalised RAndomised Controlled Trial (PRACTical) design. There are multiple drugs or dosing regimens that might be effective for carbapenem-resistant infections. Specifically, of a network of several different regimens of interest, each patient would be randomly assigned only to those regimens that were considered clinically reasonable for that patient at that time (ie, reflecting individualised equipoise), incorporating antimicrobial susceptibility, toxicity profile, and physician judgement. Each patient would then be randomly assigned to one of the clinically acceptable treatment regimens from their personalised randomisation list. The set of patients with the same personalised randomisation list would then form the unit analogous to the trial in network meta-analysis. The full regimen list would be created by reviewing current literature, in discussion with industry if new drugs were included, and in consultation with participating physicians across trial sites, as the proposed regimens must be widely acceptable and available. An example of how individual patients might be randomly assigned in such a trial is shown in the table with a flow diagram in figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed flow diagram of participants through the trial.

We propose that the eligible population would be patients with bloodstream infections and hospital-associated or ventilator-associated pneumonia (as defined by the FDA24 or European Medicines Agency25), highly likely or proven to be caused by a carbapenem-resistant organism (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, A baumanii, or P aeruginosa). These infections are still relatively uncommon in high-income settings but are now common in Asia,26 where such trials should be done. Patients would be randomly assigned when the clinician decides to initiate therapy to treat a life-threatening proven or highly likely carbapenem-resistant infection. Generally, this decision requires the results of culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, but might be affected by known previous carbapenem-resistant organism colonisation or other epidemiological risk factors.

The physician would consider the treatment options for each individual patient from the full regimen list based upon their assessment of the nature and antimicrobial susceptibility of the infecting organisms, clinical presentation, PK–PD properties of the drugs available, and the patient’s characteristics (table). This could be conceptualised as a list of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria that the physician would use to determine the initial randomisation possibilities for each patient, which could then be further individualised into a personal randomisation list based on physician preference or local availability. Although there would probably be some clinician or site-specific preferences for certain regimens, given combination therapy choices in studies to date,26 these preferences are very likely to vary substantially between sites, and even between clinicians within sites. In practice, sufficient numbers of participating sites and previous assessment of site and physician preferences would ensure variation in the personal randomisation lists and overcome potential risks of restricted prescribing. A single protocol would harmonise delivery of each regimen and management. The number of different regimens and complexity of dosing would preclude masking, but standard two-arm trials in this area of research have been open label for similar reasons.

Table. Example of possible regimens for personalised randomised trial design.

| Patient 1: moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance <40mL/min) | Patient 2: history of myocardial infarction | Patient 3: meropenem MIC ≥64 | Patient 4: ventilator-acquired or hospital-acquired pneumonia | Patient 5: Pseudomonas aeauumosu infection | Patient 6: known class B (NDM, IMP, VIM) infection | Patient 7: presence of 6S ribosomal RNA methyltransferases (encoding aminoglycoside resistance)* | Patient 8: history of moderate to severe allergy to cephalosporins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: plazomicin | No or maybe† | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| B: ceftazidime plus avibactam | No or maybe† | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| C: cefiderocol | Maybe† | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| D: high-dose meropenem‡ | Maybe† | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| E: polymyxin B with or without zidovudine | No or maybe† | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F: high-dose meropenem‡ plus ertapenem | Maybe† | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| G: high-dose meropenem‡ plus imipenem | No or Maybe† | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H: high-dose meropenem‡ plus polymyxin B with or without zidovudine | No or maybe† | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| I: high-dose meropenem‡ plus high-dose tigecycline | Maybe† | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| J: high-dose meropenem‡ plus fosfomycin | Maybe† | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| K: high-dose tigecycline§ plus polymyxin B with or without zidovudine | No or maybe† | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| L: high-dose tigecycline§ plus fosfomycin | Maybe† | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| M: fosfomycin plus polymyxin B with or without zidovudine | No or maybe† | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

MIC=minimum inhibitory concentration. NDM=New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase. IMP=imipenemase. VIM=Verona integron metallo-β-lactamase.

Based on plausibility as assessed by high MIC.

Dose adjustments required in patients with renal impairment, which might or might not be assessed as feasible in an individual patient; patient weight or surface area and creatinine are important variables, given their likely effect on drug exposure to the treatment outcome.

By use of continuous or prolonged infusion (>3 h); 2 g delivered every 8 h.

200 mg loading dose and 100 mg maintenance dose every 12 h.

The trial endpoints should be objective (reducing the effect of lack of blinding) with direct relevance to patients and physicians. Both bloodstream infections and hospital-associated or ventilator-associated pneumonia are life-threatening infections. Therefore, we consider that phase 3 trials, which aim to provide practice-changing evidence, should be large and definitive with mortality as their primary endpoint.27 Syndrome-specific outcomes have been defined by regulators assessing licensing trials and these could also be included as endpoints.

Statistical considerations

Extrapolating from network meta-analysis, initial simulations show that two-analysis methods give appropriate inference about differences between regimens. The network method corresponds to a common-effect network meta-analysis, combining direct and indirect evidence by assuming consistency (ie, that relative treatment effects are the same for each patient type).23 Failure of consistency would be shown by interactions between treatment and personalised randomisation. In the pairwise method, all data for each pairwise comparison of any two regimens (a pairwise trial) are stacked and analysed using robust variance adjustments. Both network and pairwise methods ensure that direct comparisons between any pair of regimens are informed only by patients who are eligible for both regimens and are, therefore, comparable. Uncertainty will be expressed via confidence intervals around relative treatment effects, but our aim is not to show statistical significance and so there is no need to allow for multiple testing. Instead, across a network of regimens, the goal is essentially to rank the options and provide some degree of assurance that the top-ranked regimen that is relevant for any individual patient is one of the best regimens for that patient. For example, from the table, a new patient could take any of these regimens: plazomicin, ceftazidime plus avibactam, high-dose meropenem, high-dose meropenem plus ertapenem, high-dose mero-penem plus polymyxin B with or without zidovudine, or high-dose meropenem plus high-dose tigecycline. The goal of a personalised randomised trial is to ensure that there is a high probability that the top-ranked regimen from this list based on the trial’s results provides an expected improvement in the primary outcome compared with any randomly chosen regimen from this list.

One important challenge for all trials is variation in differences between regimens by, for example, heterogeneous types and severity of comorbidity or underlying disease (ie, subgroup effects or interactions), which even traditional trial designs are rarely powered to detect. However, the fact that our new design uses both indirect and direct evidence in any regimen comparison requires specific consideration and checking of consistency in the analysis. In all trials, not just this new proposed design, the main approach to deal with heterogeneity in regimen comparisons is to restrict eligibility criteria to a more homogeneous group and try to answer the questions within this group. The challenge is then to generalise such results. The alternative is to enrol a broad and generalisable group of patients and accept that power to detect all but the strongest interactions will be low. We favour the latter approach, because, given the underlying mechanism of action (bacterial killing), it is plausible that only qualitative (effect vs no effect) interactions are likely to be clinically important. The ranking analysis method, however, could be applied within specific subgroups to investigate, for example, whether the top three regimen choices from any personalised randomisation list varied substantially across different patient subgroups.

The potential for variation by age raises the question as to whether such a trial should recruit adults or adolescents only, infants or children only, or both, given the threat that carbapenem-resistant organism infections pose across the age groups. Assuming appropriate dose adjustment for maturity, patient’s weight, and kidney function (thus overcoming major age-driven differences in pharmacokinetics), the antimicrobial action of different drugs and combinations is unlikely to vary substantially by age. There is a recognised ethical obligation to ensure that children benefit from research to identify the best treatments for them as for adults.28 We can identify no current trials on carbapenem-resistant organisms in children. A review of the global literature noted a mortality of 36% from a total of 23 children and 38 neonates.29 Therefore, we strongly advocate for including all ages in the trial. A single independent data monitoring committee would monitor safety and efficacy (eg, by use of single-group Bayesian stopping rules) to halt randomisation to regimens with unacceptable toxicity,30 overall and by age group.

The primary analysis would be intention to treat. Postrandomisation changes to antimicrobial therapy are permissable and probable, but can be assumed to represent what would happen outside the trial context, where the trial regimens would be used in clinical practice. Therefore, the initial randomised comparison will more closely reflect real-world effectiveness. Changes from randomised treatment could also be adjusted for using inverse probability weighting methods.31 If cure was the primary efficacy endpoint, and change of regimen was counted as a failure, then a further possibility would be to re-randomise patients who need to change treatment for lack of response, clinical deterioration, or treatment-emergent toxicity to a new personalised list of acceptable regimens.32 Our proposal differs from a Sequential Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trial (SMART) design that aims to optimise sequences of treatments.

Sample size

Standard methods for determining sample size (eg, to detect a clinically relevant improvement in outcome from an intervention vs a comparator regimen) do not apply to a network of regimens. We did a simulation analysis assuming that ten regimens in a network have overall 30-day mortality uniformly distributed between 10–30%; if, hypothetically, we could choose the true top-ranked regimen for each patient, then we would reduce mortality by 5·5% on average across simulations compared with choosing a random regimen for each patient from the personalised randomisation list. A 5·5% reduction is, therefore, the maximum possible average reduction in mortality if perfect information on the true mortality under each regimen was available. Randomising 1000 patients provides an expected mortality reduction of 4·6% from choosing the top-ranked regimen based on the trial’s results versus choosing a random regimen from the personalised randomisation list before the trial—ie, resulting in a gain of 82% (ratio at 4·6% to 5·5%) of the maximum possible benefit. It also provides a 90% probability (calculated using simulations) that selecting the top-ranked regimen reduces an individual patient’s mortality risk versus choosing randomly. Mortality reductions would be greater if some regimens have mortality much worse or better than 10–30%. One advantage of the regimen network is that, intrinsic to the design, most information is obtained about regimens that are acceptable to more patients. These regimens would have proportionately more patients enrolled to them by the trial’s end. This strategy maximises information available on these regimens and increases precision in their ranking, but without requiring patients to all have the potential to be randomly assigned to a common control regimen.

Implementation and impact

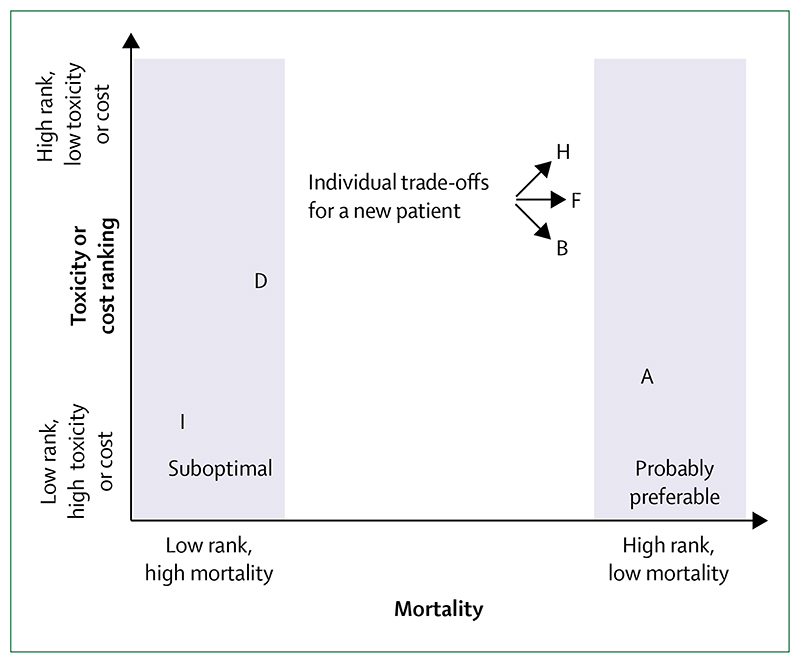

The trial results would rank the regimens according to their efficacy, safety, and cost (figure 2). When faced with a new patient, their key characteristics and their infection (eg, organism and its susceptibility profile, infection type, renal or liver function impairment) would determine which regimens are acceptable, and the ranking of these acceptable regimens on the primary outcome (30-day mortality) would then suggest the obvious treatment choice in many situations. Any major qualitative interactions could change the ranking for some key characteristics. However, the trial can also rank secondary outcomes, which might have different degrees of importance in different settings and for licensing trials.

Figure 2. Hypothetical ranking of regimens from a personalised randomisation list for a future individual patient after the trial.

Efficacy ranking based on predicted probability of primary outcome for the personalised randomisation subset (table). I=high-dose meropenem plus high-dose tigecycline. D=high-dose meropenem. H=high-dose meropenem plus polymyxin B with or without zidovudine. F=high-dose meropenem plus ertapenem. B=ceftazidime plus avibactam. A=plazomicin.

Similarly, if the two top-ranked regimens on mortality have very different toxicity profiles or ease of dosing, physicians might make different choices depending on patient characteristics. These decisions could be facilitated by electronic clinical decision support systems for physicians, or formalised into institutional, national, or, eventually, WHO guidelines.

Challenges

The panel presents some advantages and disadvantages of the new design. There is no doubt that implementation would raise challenges, not least explaining the design to ethics committees in multiple sites across multiple countries. Interestingly, despite concerns about explaining more complex designs to patients and clinicians, multiarm trials have generally recruited faster than standard two-arm trials, possibly because they more closely reflect real-world uncertainties and hence have greater salience.33 Regulatory approval for use of some drugs in a trial might be difficult, and could vary by country, but this might simply further restrict the personalised randomisation list for some patients. There will be competition for similar patients from innovator companies doing carbapenem-resistant organism studies, which will provide high per-patient fees. Many patients are not eligible for such standard two-arm licencing trials, but could enter the proposed personalised randomisation trial. Whether and how data from this novel design could support licensing applications would need discussion with the FDA and European Medicines Agency. Clinicians might potentially only wish to randomise between their top two choices for an individual patient, reducing power across the network of regimens: clear criteria for inclusion and exclusion of specific regimens and minimising the number of regimens that can be rejected for physician preference could mitigate this issue and increase generalisability. Recommending doses in patients likely to have renal insufficiency, which might then improve during treatment, is challenging, particularly where access to therapeutic drug monitoring is limited and as most of the drugs under consideration do not have adequate pharmacokinetic data in individuals with severe infections.

Conclusions

The major challenge to obtaining robust evidence on the most effective regimens for life-threatening carbapenem-resistant infections is that a large number of the potential treatment options in routine clinical care might not be relevant for any individual patient, preventing successful conduct of a traditional two-arm or even multiarm randomised controlled trials. The current, largely innovator company-led, single comparator trials are not designed to answer the urgent public health question, identified as a high priority by WHO, particularly for antibiotics in the reserve group of the Essential Medicines list, of what are the best regimens out of the available options that will significantly reduce morbidity, costs, and mortality. We propose a novel trial design, building on network meta-analysis methods, to maximise the relevance to each individual patient, and enable the safest and most efficacious regimens from any personalised randomisation list to be identified.

Panel: Advantages and disadvantages of personalised randomised controlled trial designs.

Advantages

No requirement for predefined standard of care control group, facilitating wide recruitment across ages, centres, and countries.

No requirement that both control and all interventions can be taken by all randomly assigned patients, enhancing recruitment

Pretrial engagement with physicians in construction of full randomisation list increasing trial buy-in and subsequent recruitment

Pragmatic eligibility criteria enhancing recruitment

Provides outcomes that can inform individual countries’ public health decisions

Faster recruitment and multiple randomised groups result in quicker results on more relevant regimens

Personalised randomisation list enhances potential benefit to patients from joining the trial, because the regimens that they can be randomised to are more individually relevant

Trial mirrors normal clinical practice, easing on-the-ground delivery

Trial produces an easy to understand ranking of multiple patient-focused (eg, oral administration, few side-effects) and physician-focused outcomes (eg, drug susceptibility profile, renal function)

Results might lead to electronic clinical decision support systems that provide better targeted therapy for individual patients

Disadvantages

Complex statistical methods supporting the design (no hypothesis testing), potentially reducing wider understanding and future buy-in

Standard sample size calculations cannot be used

Novel concept of ranking regimens according to efficacy and safety: direct clinical utility might take time

Likely to require multiple participating sites and physicians to overcome risk of limited prescribing and restricted use of the full randomisation list

Design might be perceived as too complicated by physicians and policy makers

Ethical committees might not understand or easily approve the design

Will require substantial discussions with regulators to become applicable to licensing trials

Acknowledgements

ASW, IRW, and RMT are supported by core support from the MRC to the MRC Clinical Trials Unit (MC_UU_12023/22 through a concordat with the Department for International Development, MC_UU_12023/29). ASW is also supported by the Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre; and is an NIHR senior investigator. GET and NJW are supported by the Wellcome Trust (UK). LYH is supported by the Singapore National Medical Research Council’s Collaborative Centre Grant (NMRC/CGAug16C005). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, the UK Department of Health, or Public Health England.

Footnotes

Contributors

The concept of this Personal View was developed by ASW, IRW, RMT, MS, and GET, with input from HLY, YTW, and NJW. The manuscript was drafted by ASW, IRW, MS, and GET, and critically reviewed by all authors.

Declaration of interests

ASW reports grants from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and from the UK National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR), during the conduct of the study. MS is the Chair of the Antibiotic Working Group of the WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

A Sarah Walker, MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, London, UK; Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Ian R White, MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, London, UK.

Rebecca M Turner, MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, London, UK.

Li Yang Hsu, National University of Singapore, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, Singapore.

Tsin Wen Yeo, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Nicholas J White, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; Mahidol-Oxford Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Mike Sharland, St George’s University of London, London, UK.

Guy E Thwaites, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

References

- 1.Bush K. Past and present perspectives on β-Lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01076-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01076-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drusano GL, Neely MN, Yamada WM, et al. The combination of fosfomycin plus meropenem is synergistic for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in a hollow-fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01682-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01682-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pryjma M, Burian J, Kuchinski K, Thompson CJ. Antagonism between front-line antibiotics clarithromycin and amikacin in the treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus infections is mediated by the whiB7 gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01353-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01353-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAleenan A, Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, et al. Methodological features of clinical pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic studies of antibacterials and antifungals: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1374–89. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulitta JB, Hope WW, Eakin AE, et al. Generating robust and informative nonclinical in vitro and in vivo bacterial infection model efficacy data to support translation to humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02307-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02307-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizk ML, Bhavnani SM, Drusano G, et al. Considerations for dose selection and clinical pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics for the development of antibacterial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02309-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02309-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrara E, Bragantini D, Tacconelli E. Combination versus monotherapy for the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:594–99. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheu CC, Chang YT, Lin SY, Chen YH, Hsueh PR. Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae: an update on therapeutic options. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:80. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piperaki ET, Tzouvelekis LS, Miriagou V, Daikos GL. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: in pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:951–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durante-Mangoni E, Andini R, Zampino R. Management of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:943–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez-Gutierrez B, Rodriguez-Bano J. Current options for the treatment of infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in different groups of patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:932–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin YW, Abdul Rahim N, Zhao J, et al. Novel polymyxin combination with the antiretroviral zidovudine exerts synergistic killing against NDM-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02176-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02176-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton S. Which clinical studies provide the best evidence? The best RCT still trumps the best observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:255–56. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez-Gutierrez B, Salamanca E, de Cueto M, et al. Effect of appropriate combination therapy on mortality of patients with bloodstream infections due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (INCREMENT): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:726–34. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKinnell JA, Dwyer JP, Talbot GH, et al. Plazomicin for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:791–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1807634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al. Once-daily plazomicin for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:729–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul M, Daikos GL, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria:an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:391–400. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Antibacterial agents in clinical development: an analysis of the antibacterial clinical development pipeline, including tuberculosis. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [accessed April 30, 2020]. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/antibacterial_agents_clinical_development/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parmar MK, Sydes MR, Cafferty FH, et al. Testing many treatments within a single protocol over 10 years at MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL: multi-arm, multi-stage platform, umbrella and basket protocols. Clin Trials. 2017;14:451–61. doi: 10.1177/1740774517725697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanini S, Ioannidis JPA, Vairo F, et al. Non-inferiority versus superiority trial design for new antibiotics in an era of high antimicrobial resistance: the case for post-marketing, adaptive randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e444–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouse B, Chaimani A, Li T. Network meta-analysis: an introduction for clinicians. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12:103–11. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1583-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley RD, Jackson D, Salanti G, et al. Multivariate and network meta-analysis of multiple outcomes and multiple treatments: rationale, concepts, and examples. BMJ. 2017;358:j3932. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2008;17:279–301. doi: 10.1177/0962280207080643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia: developing drugs for treatment. 2020. [accessed April 30, 2020]. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm234907.pdf .

- 25.EMA. Addendum to the guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products indicated for treatment of bacterial infections. European Medicines Agency; London, UK: 2013. Oct 24, [accessed April 30, 2020]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/addendum-guideline-evaluation-medicinal-products-indicated-treatment-bacterial-infections_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewardson AJ, Marimuthu K, Sengupta S, et al. Effect of carbapenem resistance on outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by Enterobacteriaceae in low-income and middle-income countries (PANORAMA): a multinational prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:601–10. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PNA, McNamara JF, Lye DC, et al. Proposed primary endpoints for use in clinical trials that compare treatment options for bloodstream infection in adults: a consensus definition. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:533–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burman WJ, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Walker AS, Vernon AA, Donald PR. Ensuring the involvement of children in the evaluation of new tuberculosis treatment regimens. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dona D, Sharland M, Heath PT, Folgori L. Strategic trials to define the best available treatment for neonatal and pediatric sepsis caused by carbapenem-resistant organisms. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:825–27. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zohar S, Teramukai S, Zhou Y. Bayesian design and conduct of phase II single-arm clinical trials with binary outcomes: a tutorial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:608–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Per-protocol analyses of pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1391–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsm1605385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahan BC, Forbes AB, Dore CJ, Morris TP. A re-randomisation design for clinical trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:96. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parmar MK, Carpenter J, Sydes MR. More multiarm randomised trials of superiority are needed. Lancet. 2014;384:283–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]