Abstract

Background

Eating disorders are widespread illnesses with significant impact. There is growing concern about how young people overuse online resources leading to mental health sequelae.

Methods

We gathered data from 639 individuals from a population cohort. Participants were all young adults at the point of contact and were grouped as having probable eating disorder with excessive exercise (n=37) or controls (n=602). We measured obsessionality, compulsivity, impulsivity, and problematic internet use. Group differences in these domains were evaluated; and structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to assess structural relationships between variables.

Results

Cases had higher scores of obsessional thoughts of threat (Cohen’s d=0.94, p <0.001), intolerance towards uncertainty (Cohen’s d=0.72; p <0.001), thoughts of importance and control (Cohen’s d=0.65, p <0.01), compulsivity (Cohen’s d=0.72; p <0.001), negative urgency (Cohen’s d=0.75, p<0.001), and higher problematic usage of the internet (Cohen’s d=0.73; p-corrected <0.001). Our SEM showed significant partial mediation of problematic internet use on both the effect of obsessionality latent factor on cases (z-value=2.52, p<0.05), as well as of sensation seeking latent factor on cases (z-value=2.09, p<0.05).

Discussion

Youth with eating disorder and heightened exercise levels have increased obsessive thoughts of threat, compulsivity traits and sensation seeking impulsivity. The association between obsessive thoughts and eating disorders, as well as sensation seeking and eating disorder symptoms were partially mediated by problematic internet use. Excessive use of online resources may be playing a role in the development or maintenance of eating disorder symptoms in the background of obsessional thoughts and sensation seeking impulsive traits.

Keywords: eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, internet addiction, problematic internet use

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) have the highest morbidity and mortality of all mental illnesses (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, & Nielsen, 2011) and affect a significant proportion of the population. Depending on the cohort and definition, anorexia nervosa (AN) has a lifetime prevalence of between 1.2% and 4.3% (broad definition) in females (Smink, Van Hoeken, & Hoek, 2012) and 0.24% in men, whereas bulimia nervosa (BN) has a lifetime prevalence of 1.0-2.9% in females, and 0.5% in men (Smink et al., 2012). Incidence of AN has increased 50-fold since the 1930s and has remained relatively stable since the 1970s (Hoek, 2006); however, some studies suggest an ongoing increase of incidence in younger populations (Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay, & Schmidt, 2015) and eating disorders still remain an important health burden for societies worldwide (Erskine, Whiteford, & Pike, 2016; Treasure et al., 2015).

Problematic usage of the internet and eating disorders

Over the last decade, there has been growing concern over the impact of online media on eating disorders (Ioannidis et al., 2020; Mingoia, Hutchinson, Wilson, & Gleaves, 2017; Tiggemann & Miller, 2010; Tiggemann & Slater, 2013, 2017). Problematic usage of the internet (PUI) is an umbrella term used to describe maladaptive behaviors manifesting on the online milieu (Fineberg et al., 2018) and PUI is an age-related multifaceted construct that encompasses a number of maladaptive online behaviors (Ioannidis et al., 2018) linked with heightened levels of psychiatric comorbidity (Ho et al., 2014). Cross-sectional correlations between PUI and eating disorder psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, restrained eating, drive for thinness have been shown in meta-analysis (Ioannidis et al., 2020), while studies of bulimia and PUI show similar correlations and group comparisons (Butkowski, Dixon, & Weeks, 2019; Melioli, Rodgers, Rodrigues, & Chabrol, 2015; Smith, Hames, & Joiner, 2013; Tao, 2013). A number of prospective studies support the notion that effects of PUI on eating disorders do exist and exposure to particular types of online content e.g. social networking site (SNS) use may have accumulating effects over time (de Vries, Peter, de Graaf, & Nikken, 2016; Ferguson, Muñoz, Garza, & Galindo, 2014; Hsieh, Hsiao, Yang, Liu, & Yen, 2018; Hummel & Smith, 2015; Smith et al., 2013; Tiggemann & Slater, 2017). Experimental studies in the field have demonstrated direct effects of SNS usage or consumption of pro-ED content (e.g. “fitspiration”) on body dissatisfaction, internalization of the thin ideal and weight and shape concerns (Fardouly, Diedrichs, Vartanian, & Halliwell, 2015; Mabe, Forney, & Keel, 2014; Prichard, Kavanagh, Mulgrew, Lim, & Tiggemann, 2020; Slater, Halliwell, Jarman, & Gaskin, 2017; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015).

Excessive exercise

Excessive exercise is a particularly challenging eating disorder behavior that can lead to catastrophic consequences e.g. precipitous weight loss, coupled with exercise through injury, heart abnormalities (e.g. life threatening bradycardia), rhabdomyolysis, among other complications (Ghoch, Calugi, & Grave, 2016; Peñas-Lledó, Vaz Leal, & Waller, 2002). AN cohorts present with excessive exercise in up to ~80% (Rizk, Lalanne, Berthoz, Kern, & Godart, 2015)and in a 15-year-prospective study of AN showed compulsive excessive exercise at the time of discharge being one of the most significant predictors of chronic outcome and early time to relapse (HR = 2.2, 95% CI = 1.1–4.9) (Strober, Freeman, & Morrell, 1997). Excessive exercise has been linked with the consumption of “thinspiration” or “fitspiration” online content (Carrotte, Vella, & Lim, 2015; Quesnel, Cook, Murray, & Zamudio, 2018), as well as weight loss and fitness applications (Apps) in both males and females (Almenara, Machackova, & Smahel, 2019; Embacher Martin, McGloin, & Atkin, 2018; Levinson, Fewell, & Brosof, 2017; Linardon & Messer, 2019; Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017).

Obsessionality, intolerance of uncertainty and compulsivity in eating disorders

Obsessional ideas about own body image are core symptoms of AN (Collier & Treasure, 2004) and have causally been linked to starvation since the early exploration of consequences of starvation to healthy individuals (Minnesota study) (Keys, Brozek, Henschel, Mickelsen, & Taylor, 1950). In the 1980s’ EDs were considered as extreme manifestations of societal obsession with thinness (Collier & Treasure, 2004) and we now know that AN has a genetic linkage with obsessionality on chromosome 1 locus (Devlin, 2002). Furthermore, restricting AN was demonstrated to have reduced cognitive flexibility both during AN episodes and after recovery (Tchanturia et al., 2004), while individuals with AN experience obsessional thoughts linked to their compulsive exercise, eating and weight related obsessionality (Byrne et al., 2018; Godier & Park, 2015).

Linked to obsessional traits, ‘intolerance of uncertainty’ (IU) is the tendency for a negative emotional, cognitive and behavioral reaction to uncertain situations and events. Compulsive eating disorder behaviors have been linked to IU (Boswell, Thompson-Hollands, Farchione, & Barlow, 2013; Parkes et al., 2019). IU has been quantitatively demonstrated as prevalent in AN (Frank et al., 2012; Sternheim, Startup, & Schmidt, 2011) and qualitatively explored to show that IU in AN manifests as fear of unduly evaluation from others, leading to social problem solving difficulties (Sternheim, Danner, van Elburg, & Harrison, 2020) and compulsive planning and action (Sternheim, Konstantellou, Startup, & Schmidt, 2011).

Compulsivity has been defined as a trait in which actions are persistently repeated despite adverse consequences (Robbins, Gillan, Smith, de Wit, & Ersche, 2012). Behavioral traits of compulsivity covary with eating disorder psychopathology (Godier & Park, 2014). Extreme dietary restriction and over-exercise may reflect excessive habit formation leading to compulsive starvation or over-activity behavior (Everitt & Robbins, 2005; Fladung et al., 2010).

Impulsivity and sensation seeking in eating disorders

Impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct referring to acting without forethought or reflection or consideration of the consequences. PUI has been linked with increased levels of trait impulsivity and compulsivity (Ioannidis et al., 2016) and sensation seeking (Lin & Tsai, 2002). Impulsivity in eating disorders has been linked to poor long-term AN outcomes (Fichter, Quadflieg, & Hedlund, 2006), but also strongly related with bulimia with or without purging and binge eating disorder (Collier & Treasure, 2004; Fahy & Eisler, 1993). Heightened sensation seeking impulsivity has been particularly demonstrated in bulimia as compared to controls (Rossier, Bolognini, Plancherel, & Halfon, 2000) even after controlling for victimization and traumatic experiences (Brewerton, Cotton, & Kilpatrick, 2018). Impulsivity, compulsivity and obsessionality, when considered together they are found as prevalent behaviors in purging anorexia (Hoffman et al., 2012). Obsessional thinking is strongly positively correlated with compulsive behavior(Kim et al., 2016). Impulsivity and compulsivity exist cross-diagnostically in latent functionally impairing forms which are positively correlated (Chamberlain, Stochl, Redden, & Grant, 2018).

Aims and hypotheses

This current study had two aims: first we aimed to compare the behavioral characteristics of eating disorder traits with heightened levels of exercise in respect to their levels of (1) impulsivity, (2) compulsivity, (3) obsessionality, (4) sensation seeking, (5) intolerance to uncertainty and (6) problematic usage of the internet against controls. By doing so, we aim to quantify differences on group level in our dataset, as they have been demonstrated in previous research, and establish that our cohort does share the behavioral characteristics in line with current literature. Therefore, we hypothesized that participants with eating disorders and heightened exercise will present with increased levels of trait impulsivity, compulsivity, obsessionality, as well as heightened levels of intolerance for uncertainty and sensation seeking when compared to controls. Our second aim would be to statistically explore the structural relationship between the variables in our model and consecutively the potential mediating effect that problematic internet use may have on these neurobiological dimensions on their effect on eating disorders. To date there is no study exploring those mediating effects of PUI in eating disorders.

Methods

Study criteria and recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Neuroscience in Psychiatry Network (NSPN) UK youth cohort:, which is a longitudinal cohort, exploring brain development trajectories and mental health outcomes (Kiddle et al., 2018). The sample was originally recruited on an age-sex stratified basis, in order to maximize representativeness of the normal population in the catchment areas covered (Cambridge and London). In this study, we contacted all individuals (adults, Mean [sd] age: 23.4 [3.2]) who were still enrolled in this cohort at the time of data collection (2017–2018) via email and invited them to take part in an online study being conducted via SurveyMonkey. Participants received £15 compensation in the form of a gift voucher. Further methodological details about the recruitment and instruments are presented in previous work (Chamberlain et al., 2019). The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, subject to agreement of the Chief Investigator. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions

Ethical considerations

The procedures of this study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the Cambridge East Research Ethics Committee (Study approval number 16/EE/0260). All subjects gave informed consent online.

Assessments

Participants were classified as cases according to whether or not they displayed high probability of having an eating disorder diagnosis and excessive exercise. For the assessment of their eating disorder diagnosis we used the SCOFF Eating Disorder Questionnaire (Luck et al., 2002). This is a validated screening tool for detection of eating disorders, specifically either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. The scale is sensitive to the presence of different aspects of eating disorder symptoms, such as purging, weight loss, distorted body image, loss of control over eating and food preoccupation. A score of 2 and above indicates high likelihood of an eating disorder reason why we used this cut-off to define our cases. For the assessment of excessive exercise, we used the exercise addiction inventory (EAI) (Griffiths, Szabo, & Terry, 2005). Due to prior absence of an established cut-off, we defined excessive exercise based on scores being >1 standard deviation from that of the cohort that was examined (19 and above; the mean cohort score was 13.4). Therefore, our cases were characterized as probable eating disorder (either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa) plus excessive exercise symptoms.

Behavioral Assessments

Problematic usage of the internet

Problematic usage of the internet was quantified using the Internet Addiction Test short-12 item version (IAT-12) (Pawlikowski, Altstötter-Gleich, & Brand, 2013). The IAT-12 consists of twelve items ascertaining the level of problematic internet use, and was developed from Kimberley Young’s Internet Addiction Test, based on rigorous psychometric refinement of the original scale.

Compulsivity

Cambridge–Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T) (Chamberlain & Grant, 2018). This is a scale designed to capture the comprehensive aspects of compulsivity, viewed trans-diagnostically. The scale comprises 15 items, each scored on a Likert scale of 1–4, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The total score is 60, with higher scores indicating higher compulsivity. The scale is sensitive to compulsivity across a range of pathologies, such as disordered gambling, substance use, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Albertella et al., 2019).

Impulsivity

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale short version (BIS-8) to quantify impulsive personality (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995) is a self-report questionnaire used to determine levels of impulsiveness.

The short Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, Positive Urgency, Impulsive Behavior Scale (S-UPPS) is a measurement of impulsivity as a multi-faceted and multi-dimensional construct, comprising five impulsive personality traits (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The proposed model of impulsivity includes five specific (distinct) dispositions a) sensation seeking (i.e. pursuit of novel/exciting stimuli), b) lack of planning (i.e. action without advanced planning), c) lack of perseverance (i.e., limited capacity for focus maintenance), d) positive urgency (i.e., rash action in response to intense positive emotions), and e) negative urgency (i.e., rash action in response to intense negative emotions) (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The S-UPPS scale has five subscales (first order factors) and four items per sub-scale. Sensation seeking comprises a second order factor alone, whilst positive and negative urgency comprise ‘emotion based rushed action’ and lack of premeditation and perseverance comprise ‘deficits in conscientiousness’ (Cyders, Littlefield, Coffey, & Karyadi, 2014).

Sensation Seeking

The Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS-8) is a measure of sensation seeking as a psychobiological trait of need for novelty, complexity and intensity (Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002). It comprises of eight items of a five-point-Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

Intolerance of Uncertainty

Intolerance of Uncertainty scale (Buhr & Dugas, 2002). This is a scale original developed in French, but validated for English speakers as well. The scale comprises 27 items, each scored on a Likert scale of 1–5, from “not at all characteristic of me” to “entirely characteristic of me”; with higher scores indicating higher degree of intolerance to uncertainty. The measure of interest was the total score.

Statistical analysis

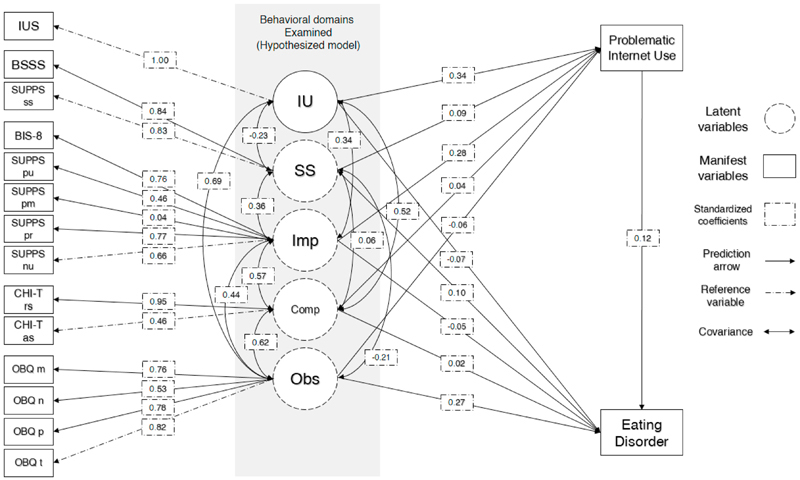

Data processing and statistical analyses were conducted using statistical software R version 3.4.2 and “dplyr” (Wickham, François, Henry, Müller, & RStudio, 2020) and “lavaan” (Rosseel, 2012) R packages. We performed direct comparisons of our cases and controls using student t-test under the assumption of normal distribution of behavioral characteristics in our cohort. The NSPN is a representative cohort of the catchment area and behavioral characteristics are expected to have normal distributions. We used chi-square to compare non-parametric values e.g. gender. Finally, we also performed a structural equation modelling (SEM) to explore structural relationships between the variables at hand; this also enabled us to ascertain whether problematic internet use has any mediation influence on the effect of behavioral traits on eating disorder cases. Our SEM initial (hypothesized) model included four latent variables predicted by manifest variables as such: a) ‘Obsessionality’ latent factor predicted by the four subscales of OBQ (“Obsessional thoughts of threat”, “Obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty”, “Obsessional thoughts of importance and control”, “Obsessional thoughts of inflated responsibility”; b) “Compulsivity” latent factor predicted by the two factors of CHI-T “reward-seeking and need for perfection” and “anxiolytic/soothing compulsivity”; c) “Impulsivity” latent factor predicted by the four factors of S-UPPS “Negative urgency”, “Lack of perseverance”, “Lack of premeditation”, “Positive urgency”, also “BIS-8 total score”; d) “Sensation seeking” latent factor predicted by “BSSS total score” and “S-UPPS Sensation seeking”. We hypothesized that those variables were predictive of problematic usage of the internet “IAT-12 total score”, as well as “cases”, as defined above (SCOFF≥2, EAI≥19). We also used “Intolerance to Uncertainty” as (IUS total score) as a separate path, predicting both PUI and “cases”. We calculated regression coefficients for all predictors as well as covariances between all latent variables between themselves and with IUS. We calculated the indirect effect of problematic internet use for every latent and IUS variable on cases. Our initial (hypothesized) model was plotted and presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structural equation model hypothesized model.

Legend: IUS = intolerance to uncertainty score; IU = intolerance to uncertainty, as directly measured by IUS; SS = sensation seeking latent factor; BSSS = Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS) total score; BIS-8 = The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, short version total score; Imp = impulsivity latent factor; SUPPS = Short UrgencyPremeditation-Perseverance-Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Scale (SUPPS); SUPPS pu = SUPPS Positive urgency; SUPPS pr = SUPPS (Lack of) perseverance; SUPPS pm = SUPPS (Lack of) premeditation; SUPPS nu = SUPPS Negative urgency; CHI-T = Cambridge-Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T); CHI-T rs = CHI-T reward-seeking and need for perfection; CHI-T as = CHI-T anxiolytic/soothing compulsivity; Comp = compulsivity latent factor; Obs = obsessionality latent factor; OBQ = Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire, short version (OBQ-20); OBQ m = Obsessional thoughts of importance and control; OBQ n = Obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty; OBQ p = Obsessional thoughts of inflated responsibility; OBQ t = Obsessional thoughts of threat; Problematic Internet use = Internet Addiction Test, short version (IAT-12) total score; Eating disorder = case; Numeric scores are standardized regression coefficients in direct lines and standardized covariance coefficients in curves lines.

We then followed a step wise change of our model by adding relationships based on their modification indices and subtracting relationships based on non-significant covariances, aiming to improve the model’s goodness of fit statistics. We added new relationships with high modification indices taking into account the theoretical implications of adding those relationships into the model. We calculated the degrees of freedom, goodness and badness of fit statistics (“AIC” = Akaike information criterion; “CFI” = comparative fit index; “TLI” = Tucker–Lewis index; “RMSEA” = root mean square error) for every model and compared each model with the previous one using chi-square comparisons. We finalized our SEM when reached non-significant improvement in our model via path change (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003).

Results

Our final sample comprised 37 cases (i.e. individuals meeting criteria for probable eating disorder plus having excessive exercise), and 602 controls. Group comparison results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and behavioral characteristics of study cohort.

| TOTAL N = 639 | Controls N = 502 | ED Low exercise N= 100 | ED High exercise N= 37 | Group t-test comparison | p-value† | Signif. †† | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | |||||

| Age | 23.4(3.2) | 23.4(3.1) | 23.4(3.9) | 23.4(3.1) | - | - | - | - |

| Gender [%Female] | 65% | 64.7% | 70% | A < B | ||||

| Obsessional thoughts of threat (OBQ) | 15.7 (6.1) | 14.8(5.8) | 18.1 (6.4) | 21.0 (5.0) | A < B < C | |||

| Obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty (OBQ) | 18.2 (6.9) | 17.3 (6.6) | 20.6 (7.5) | 22.8 (6.2) | A < B , C | |||

| Obsessional thoughts of importance and control (OBQ) | 14.1 (6.2) | 13.4 (5.9) | 16.4 (6.7) | 17.8 (6.0) | A < B , C | |||

| Obsessional thoughts of inflated responsibility (OBQ) | 20.9 (6.3) | 20.7 (6.4) | 21.4 (6.3) | 22.6 (5.6) | - | |||

| Transdiagnostic compulsivity traits (CHI-T) | 24.3 (6.0) | 23.6 (5.9) | 26.2 (6.0) | 28.3 (4.8) | A < B < C | |||

| Impulsivity traits (BIS-8) | 16.4 (3.9) | 15.9 (3.7) | 18.4 (4.3) | 17.1 (3.6) | A < B | |||

| Negative urgency (SUPPS) | 4.74 (2.49) | 4.3 (2.3) | 6.4 (2.4) | 6.5 (2.1) | A < B , C | |||

| Lack of perseverance (SUPPS) | 4.44 (1.85) | 4.4 (1.8) | 4.8 (2.1) | 3.7 (1.6) | A, B > C | |||

| Lack of premeditation (SUPPS) | 3.95 (1.85) | 3.8 (1.8) | 4.7 (2.0) | 3.9 (2.2) | A < B | |||

| Sensation seeking (SUPPS) | 5.99 (2.60) | 6.1 (2.6) | 5.4 (2.6) | 6.6 (3.1) | A, C > B | |||

| Positive urgency (SUPPS) | 3.14 (2.14) | 3.0 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.1) | A < B, C | |||

| Intolerance of Uncertainty (IUS) | 58.3 (21.1) | 55.3 (20.0) | 69.2 (22.7) | 69.0 (18.9) | A < B, C | |||

| BSSS | 24.11(6.8) | 24.2 (6.6) | 23 (7.1) | 25.5 (7.0) | - | |||

| Internet use (IAT-12) | 13.1(8.0) | 11.7 (7.2) | 16.6 (9.9) | 18.5 (7.7) | A < B, C | |||

| Quality of life | 55.3 (17.8) | 57.3 (17.6) | 46.5 (15.4) | 50.9 (17.7) | A > B, C |

Group A = controls; Group B = ED with low exercise; Group C = ED with high exercise;

Two sample t-test p-values;

Significance: ‘*’ <0.05; ‘**’ <0.01; ‘***’ <0.001;

Chi-square; ED = Eating disorders; Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire, short version (OBQ-20); Internet Addiction Test, short version (IAT-12); Cambridge–Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T); The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, short version (BIS-8); Brief Sensation Seeking

Scale (BSSS); Short Urgency-Premeditation-Perseverance-Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Scale (SUPPS).

Case control comparison

Cases had higher scores of obsessional thoughts of threat (t-test, Cohen’s d=0.94, p<0.001), obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty (OBQ) (Cohen’s d=0.72; p<0.001), obsessional thoughts of importance and control (Cohen’s d=0.65, p<0.01), transdiagnostic compulsivity traits (Cohen’s d=0.72; p<0.001), negative urgency (Cohen’s d=0.75, p<0.001), intolerance of uncertainty (IUS) (Cohen’s d=0.55; p <0.05), and higher problematic usage of the internet (Cohen’s d=0.73; p corrected <0.001). All other results were non-significant or became non-significant after the application of Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We used standardized mean difference (Cohen’s d) under the assumption of normality and homogeneity of variances.

Structural equation modelling

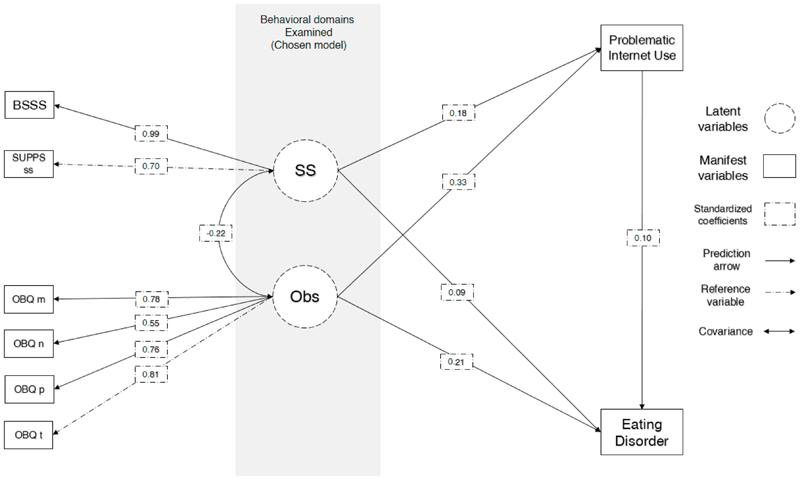

Problematic internet use was associated with obsessionality (regression coef. z=7.61, p<0.001) and sensation seeking (z=4.65, p<0.001); eating disorder case was associated with obsessionality (z=4.53, p<0.001), sensation seeking (z=2.26, p<0.02) and PUI (z=2.32, p<0.02). The chosen model with the lowest RMSEA was model 8 (see Table 2) which had Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.975 and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.956 indicating good fit. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation was less than 0.1 (mean=0.059; 1000-iterations-bootstrap 95%CI 0.059-0.060). The indirect (mediation) effect of PUI on obsessionality effect on cases was statistically significant (z=2.25, p=0.024) indicating partial mediation (Obsessionality ~ case standardized effect reduction from 0.24 to 0.21 [12.5% reduction]). The indirect (mediation) effect of PUI on sensation seeking effect on cases was statistically significant (z=2.08, p=0.037) indicating partial mediation (Sensation seeking ~ case standardized effect reduction from 0.11 to 0.09 [18% reduction]). Initial models did not have acceptable goodness of fit statistics and were rejected (see Table 2). Full mediation SEM results are presented in Table 3. Model 8 (chosen model) is graphically presented in Figure 2. Comparative statistics between hypothesized model and final model are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Structural equation modelling.

| Model | DF | χ2 diff | Pr (>Chisq) | AIC | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | 95%CI RMSEA | Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIRST MODEL | 90 | - | - | 44816.52 | 0.653 | 0.538 | 0.158 | 0.158 - 0.158 | - |

| 2 | 89 | 187.68 | *** | 44624.60 | 0.706 | 0.603 | 0.146 | 0.146 - 0.147 | comp_rsfr ~~ supps_lackpersevrnce |

| 3 | 88 | 23.463 | *** | 44611.65 | 0.712 | 0.607 | 0.146 | 0.145 - 0.146 | comp_rsfr ~~ bis8_total |

| 4 | 87 | 122.89 | *** | 44488.21 | 0.748 | 0.653 | 0.137 | 0.137 - 0.137 | bis8_total ~~ supps_lackpremed |

| 5 | 67 | 147.12 | *** | 39466.08 | 0.735 | 0.640 | 0.143 | 0.142 - 0.143 | Compulsivity =~ comp_rsfr + comp_arss |

| 6 | 66 | 63.713 | *** | 39395.04 | 0.759 | 0.667 | 0.137 | 0.137 - 0.137 | OBQ_perfec_intoluncert ~~ supps_lackpersevrnce |

| 7 | 22 | 342.93 | *** | 28183.77 | 0.792 | 0.659 | 0.164 | 0.164 - 0.164 | Impulsivity =~ exogenous |

| 8 | 16 | 284.52 | *** | 23472.67 | 0.971 | 0.949 | 0.062 | 0.062 - 0.063 | ius_total ~ |

| 9 | 8 | 11.157 | 0.19 | 17743.64 | 0.970 | 0.944 | 0.072 | 0.071 - 0.072 | SS =~ bsss_total + supps_sensseek |

Legend: Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 ; DF = Degrees of freedom; χ2 diff = chi square difference; Pr(>Chisq) = p-value for the chi square test, tests compare consecutive models; AIC = Akaike information criterion; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; 95%CI RMSEA = 95% confidence intervals for RMSEA; Path = step change for each model. All results are averages and 95%CI intervals from 1000 iteration boot strap estimates of model fit.

Table 3. Structural equation regressions, total and indirect effects of H8 model.

| Regressions | Estimate | Standard Errors | z-value | P(>|z|) | Std.all |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case by ~ | |||||

| Obsessionality | 0.03 | 0.005 | 5.15 | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.01 | 0.005 | 2.01 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| PUI | 0.01 | 0.003 | 3.34 | 0.001 | 0.15 |

| PUI by ~ | |||||

| Obsessionality | 0.463 | 0.074 | 6.23 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.275 | 0.069 | 3.97 | <0.001 | 0.16 |

| Total effects | |||||

| Obsessionality on case | 0.032 | 0.005 | 6.23 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| Sensation seeking on case | 0.012 | 0.005 | 2.59 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| PUI~obsessionality | 0.005 | 0.002 | 3.02 | 0.002 | 0.044 |

| PUI~sens.seeking | 0.003 | 0.001 | 2.57 | 0.01 | 0.024 |

Legend: SS = sensation seeking latent factor; Obs = obsessionality latent factor; OBQ = Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire, short version (OBQ-20); OBQ m = Obsessional thoughts of importance and control; OBQ n = Obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty; OBQ p = Obsessional thoughts of inflated responsibility; OBQ t = Obsessional thoughts of threat; Problematic Usage of the Internet (PUI) = Internet Addiction Test, short version (IAT-12) total score; z-values = regression coefficients; Std.all = standardized coefficients; Case = SCOFF > 2, Exercise Addiction Inventory > 18.

Figure 2. Structural equation model chosen model.

Legend: BSSS = Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS) total score; BIS-8 = The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, short version total score; Imp = impulsivity latent factor; OBQ = Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire, short version (OBQ-20); OBQ m = Obsessional thoughts of importance and control; OBQ n = Obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty; OBQ p = Obsessional thoughts of inflated responsibility; OBQ t = Obsessional thoughts of threat; Problematic Internet use = Internet Addiction Test, short version (IAT-12) total score; Eating disorder = case; Numeric scores are standardized regression coefficients in direct lines and standardized covariance coefficients in curves lines.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the problematic online behaviors, coupled with behavioral characteristics of a putative eating disorders cohort with heightened excessive exercise behaviors. In our study, we identified, through group comparisons, that cases, as compared to controls, had heightened degree of obsessive thoughts of threat, obsessional intolerance towards uncertainty, obsessional thoughts of importance and control, high cross-diagnostic traits of compulsivity, negative urgency impulsivity and higher levels of problematic internet use. Those results are in line with previous research, that obsessional preoccupation with food and food predominance, as well as and intolerance to uncertainty manifesting with deficits in social decision making, planning and action, as well as fear of unduly evaluation from others (Davis & Kaptein, 2006; Sternheim, Konstantellou, et al., 2011). Increased compulsivity, manifesting as compulsive restriction of food intake and compulsive exercise is also in line with previous research (Davis & Kaptein, 2006; Godier & Park, 2014), as well as a higher level of negative urgency impulsive, particularly in cohorts of heightened impulsivity during negative emotional states (e.g. binge/purging AN or BN) (Westwater et al., 2019). The increased level of PUI is also in line with previous research.

Furthermore, our study is the first to explore the mediation effect of problematic internet behaviors on the impact of obsessionality and sensation seeking, to eating disorder symptoms, via SEM. Our analysis showed partial mediation, for both effects of obsessionality (0.24 to 0.21) and sensation seeking (0.11 to 0.09) suggestive that obsessional thoughts and sensation seeking impulsivity traits, when present in in young populations, may be impacting on the development or perseverance of eating disorders, partially via the problematic usage of online resources. While a SEM analysis does not provide evidence for causal directional link, it highlights the importance for future studies that can potentially examine this interaction further. Previous longitudinal research has shown that the use of social media (Facebook) maintained weight and shape concerns as well as state anxiety (Mabe et al., 2014) as compared to alternate online activity. Also, social media use has been associated with perseverance of obsessional body image symptoms (Tiggemann & Slater, 2013) and found to causally associate with obsessive drive for thinness longitudinally (Tiggemann & Slater, 2017). We argue that our mediation model is grounded on robust theory of obsessional thoughts and sensation seeking behavior strongly associate with both with PIU and ED and the mediation pathway in proposition is both statistically demonstrable and theoretically plausible. We argue that enhancing our understanding of the behavioral underpinnings of this effect may be helpful in the developing appropriate interventions and therapeutic targets, including health recommendations about the use of novel technology, digital interventions and appropriate clinical interviews and screening of symptoms. Obsessional thoughts linked with compulsive usage of the internet (e.g. calorie counting via apps, fitness apps, obsessing over body image content consumption, step counting etc.) and sensation seeking online behaviors (e.g. consumption of ‘fitspiration’ or food related or ‘ mukbang’ content etc.) may be potential such targets. Finally, the current manuscript is prepared in the unusual times of the COVID-19 pandemic. The global social distancing measures have driven people to rely more that even on online resources for their work, leisure and social connectedness. It is unclear what effect this may have, but it is possible that we may see higher levels of problematic usage of the internet in the future; this may mean that it would be pertinent for future research to unravel the causal links between behavioral traits predisposing for both PUI and EDs, to enable us to think about how to target those in our diagnostics, therapies and prevention programs.

Limitations

We have several limitations to consider in this study deriving from our data collection process and instruments used. Given that this is an online survey, it has less quality control and less accuracy for measuring psychopathology constructs as compared to face-to-face clinical assessments. For example, we used the SCOFF questionnaire to ascertain putative AN or BN diagnosis. While the SCOFF is an efficient screening tool for AN and BN, and its specificity and positive predictive value are reasonable (Spec.: 89.6%, PPV: 24.4%) (Luck et al., 2002) for a screening tool, it does not have ‘gold-standard’ diagnostic validity that can be provided by a clinical or DSM-5 structured interview. Furthermore, due to the survey being delivered online, there is also a potential sampling bias, since returning participants of the NSPN cohort may be those who are more technologically adept or responsive to email requests. In respect to our SEM analysis, it is important to note that mediational models are presumptuously causal models in which the mediator is presumed to cause the outcome and not vice versa (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Here, we model on the basis that latent cross-diagnostic traits e.g. sensation seeking, compulsivity, obsessionality are factors predisposing to eating disorder behaviors, however, we cannot draw causal effects; this would require a different study design. Future research with appropriate (longitudinal, randomized, controlled) design can explore further whether those causal links exist and in which direction. Furthermore, for our SEM we used the CHI-T two-factor structure as reported in first publication (Chamberlain & Grant, 2018), however this factor analysis is considered preliminary; future research on the instrument in larger samples may replicate this finding or demonstrate a different factor structure for the instrument. It is important to note that BSSS total score and sensation seeking UPPS scores considered individually were not statistically significantly higher for cases in group comparisons; however, the sensation seeking latent factor was predictive of cases (p=0.02, see Table 3). This may imply that latent sensation seeking as modelled in our SEM brings together a wider range of sensation seeking parameters, rendering the latent construct predictive of eating disorder symptoms, an attribute that the instruments may not possess if considered individually.

Conclusion

We have shown that our case group of putative eating disorders with heightened levels of activity have increased levels of obsessionality, cross-diagnostic compulsivity, negative urgency impulsivity, intolerance of uncertainty and higher levels of problematic usage of the internet. We have demonstrated that obsessionality latent factor and sensation seeking latent factor predict cases, and that problematic usage internet resources mediates that relationship. This mediation provides us novel insight into the potential role of problematic use of online resources for the development and perseverance of eating disorder psychopathology with heightened exercise levels.

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to the volunteers who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr Chamberlain’s involvement in this research was funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship (110049/Z/15/Z). Dr Chamberlain consults for Promentis and Ieso; and receives stipends from Elsevier for journal editorial work. Dr Grant reports grants from the National Center for Responsible Gaming, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Brainsway, and Roche, and others from Oxford Press, Norton, McGraw-Hill, and American Psychiatric Publishing outside of the submitted work. Authors received no funding for the preparation of this manuscript. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interest. Dr Roman-Urrestarazu work received funding from the Gillings Fellowship in Global Public Health Grant Award YOG054 and the Commonwealth Fund with a Harkness Fellowships in Health Care Policy and Practice 2020-2021.

Author contributions

KI designed the idea for the manuscript, analyzed the data, wrote the majority of the manuscript and coordinated the co-authors’ contributions. SRC, RH designed and coordinated the study and collected and managed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and contributed to the drafting and revising of the paper as well as to interpreting the results.

References

- Albertella L, Chamberlain SR, Le Pelley ME, Greenwood L-M, Lee RSC, Den Ouden L, Yücel M, et al. Compulsivity is measurable across distinct psychiatric symptom domains and is associated with familial risk and reward-related attentional capture. CNS Spectrums. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852919001330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almenara CA, Machackova H, Smahel D. Sociodemographic, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Correlates of Using Nutrition, Weight Loss, and Fitness Websites: An Online Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2019;21(4):e10189. doi: 10.2196/10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality Rates in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):724. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. https://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~schaller/528Readings/BaronKenny1986.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Thompson-Hollands J, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Intolerance of Uncertainty: A Common Factor in the Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(6):630–645. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD, Cotton BD, Kilpatrick DG. Sensation seeking, binge-type eating disorders, victimization, and PTSD in the National Women’s Study. Eating Behaviors. 2018;30:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40(8):931–945. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkowski CP, Dixon TL, Weeks K. Body Surveillance on Instagram: Examining the Role of Selfie Feedback Investment in Young Adult Women’s Body Image Concerns. Sex Roles. 2019;81(5-6):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s11199-018-0993-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne CE, Wonderlich JA, Curby T, Fischer S, Lock J, Le Grange D. Using bivariate latent basis growth curve analysis to better understand treatment outcome in youth with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2018;26(5):483–488. doi: 10.1002/erv.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MSC. Predictors of “Liking” Three Types of Health and Fitness-Related Content on Social Media: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2015;17(8):e205. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Grant JE. Initial validation of a transdiagnostic compulsivity questionnaire: The Cambridge-Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale. CNS Spectrums. 2018;23(5):340–346. doi: 10.1017/S1092852918000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Stochl J, Redden SA, Grant JE. Latent traits of impulsivity and compulsivity: Toward dimensional psychiatry. Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(5):810–821. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Tiego J, Fontenelle LF, Hook R, Parkes L, Segrave R, Yücel M, et al. Fractionation of impulsive and compulsive trans-diagnostic phenotypes and their longitudinal associations. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;53(9):896–907. doi: 10.1177/0004867419844325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier DA, Treasure JL. The aetiology of eating disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004 November;185:363–365. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Littlefield AK, Coffey S, Karyadi KA. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(9):1372–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Kaptein S. Anorexia nervosa with excessive exercise: A phenotype with close links to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2006;142(2-3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries DA, Peter J, de Graaf H, Nikken P. Adolescents’ Social Network Site Use, Peer Appearance-Related Feedback, and Body Dissatisfaction: Testing a Mediation Model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(1):211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B. Linkage analysis of anorexia nervosa incorporating behavioral covariates. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(6):689–696. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embacher Martin K, McGloin R, Atkin D. Body dissatisfaction, neuroticism, and female sex as predictors of calorie-tracking app use amongst college students. Journal of American College Health. 2018;66(7):608–616. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine HE, Whiteford HA, Pike KM. The global burden of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2016 October 1;29:346–353. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: From actions to habits to compulsion. Nature Neuroscience. 2005 November;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy T, Eisler I. Impulsivity and eating disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993 FEB;162:193–197. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly J, Diedrichs PC, Vartanian LR, Halliwell E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image. 2015;13:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Muñoz ME, Garza A, Galindo M. Concurrent and Prospective Analyses of Peer, Television and Social Media Influences on Body Dissatisfaction, Eating Disorder Symptoms and Life Satisfaction in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Hedlund S. Twelve-year course and outcome predictors of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39(2):87–100. doi: 10.1002/eat.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg N, Demetrovics Z, Stein D, Ioannidis K, Potenza M, Grünblatt E, Chamberlain S, et al. Manifesto for a European research network into Problematic Usage of the Internet. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 doi: 10.1016/J.EURONEURO.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fladung AK, Grön G, Grammer K, Herrnberger B, Schilly E, Grasteit S, Von Wietersheim J, et al. A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):206–212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank GKW, Roblek T, Shott ME, Jappe LM, Rollin MDH, Hagman JO, Pryor T. Heightened fear of uncertainty in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(2):227–232. doi: 10.1002/eat.20929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghoch M, Calugi S, Grave RD. Management of Severe Rhabdomyolysis and Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia in a Female with Anorexia Nervosa and Excessive Compulsive Exercising. Case Reports in Medicine. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8194160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godier LR, Park RJ. Compulsivity in anorexia nervosa: A transdiagnostic concept. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:778. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godier LR, Park RJ. Does compulsive behavior in Anorexia Nervosa resemble an addiction A qualitative investigation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015 OCT;6 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MD, Szabo A, Terry A. The exercise addiction inventory: a quick and easy screening tool for health practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(6):e30. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RC, Zhang MWB, Tsang TY, Toh AH, Pan F, Lu Y, Mak KK, et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006 July;19:389–394. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ER, Gagne DA, Thornton LM, Klump KL, Brandt H, Crawford S, Bulik CM, et al. Understanding the association of impulsivity, obsessions, and compulsions with binge eating and purging behaviours in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2012 May;20:e129. doi: 10.1002/erv.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:401–414. www.elsevier.com/locate/paid . [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh KY, Hsiao RC, Yang YH, Liu TL, Yen CF. Predictive effects of sex, age, depression, and problematic behaviors on the incidence and remission of internet addiction in college students: A prospective study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel AC, Smith AR. Ask and you shall receive: Desire and receipt of feedback via Facebook predicts disordered eating concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48(4):436–442. doi: 10.1002/eat.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Chamberlain SR, Treder MS, Kiraly F, Leppink EW, Redden SA, Grant JE, et al. Problematic internet use (PIU): Associations with the impulsive-compulsive spectrum. An application of machine learning in psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2016;83:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Taylor C, Holt L, Brown K, Lochner C, Fineberg NA, Czabanowska K, et al. Problematic usage of the internet and eating disorders: a multifaceted, systematic review and metaanalysis. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.20.20177535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Treder MS, Chamberlain SR, Kiraly F, Redden SA, Stein DJ, Grant JE, et al. Problematic internet use as an age-related multifaceted problem: Evidence from a two-site survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;81:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The Biology of Human Starvation. University of Minnesota Press; Oxford: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Kiddle B, Inkster B, Prabhu G, Moutoussis M, Whitaker KJ, Bullmore ET, Jones PB, et al. Cohort Profile: The NSPN 2400 Cohort: a developmental sample supporting the Wellcome Trust NeuroScience in Psychiatry Network. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2018;47(1):18–19g. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, McKay D, Taylor S, Tolin D, Olatunji B, Timpano K, Abramowitz J. The structure of obsessive compulsive symptoms and beliefs: A correspondence and biplot analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;38:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Fewell L, Brosof LC. My Fitness Pal calorie tracker usage in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors. 2017;27:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SSJ, Tsai C-C. Sensation seeking and internet dependence of Taiwanese high school adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior. 2002;18:411–426. Retrieved from www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh. [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, Messer M. My fitness pal usage in men: Associations with eating disorder symptoms and psychosocial impairment. Eating Behaviors. 2019;33:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck AJ, Morgan JF, Reid F, O’Brien A, Brunton J, Price C, Lacey JH, et al. The SCOFF questionnaire and clinical interview for eating disorders in general practice: Comparative study. British Medical Journal. 2002;325(7367):755–756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabe AG, Forney KJ, Keel PK. Do you “like” my photo Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;47(5):516–523. doi: 10.1002/eat.22254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melioli T, Rodgers RF, Rodrigues M, Chabrol H. The role of body image in the relationship between internet use and bulimic symptoms: Three theoretical frameworks. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015;18(11):682–686. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingoia J, Hutchinson AD, Wilson C, Gleaves DH. The relationship between social networking site use and the internalization of a thin ideal in females: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017 AUG;8 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes L, Tiego J, Aquino K, Braganza L, Chamberlain SR, Fontenelle L, Yücel M, et al. Transdiagnostic variations in impulsivity and compulsivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder and gambling disorder correlate with effective connectivity in cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical circuits. NeuroImage. 2019;202:116070. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2019.116070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowski M, Altstötter-Gleich C, Brand M. Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(3):1212–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G. Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;31(4):370–375. doi: 10.1002/eat.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard I, Kavanagh E, Mulgrew KE, Lim MSC, Tiggemann M. The effect of Instagram #fitspiration images on young women’s mood, body image, and exercise behaviour. Body Image. 2020;33:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel DA, Cook B, Murray K, Zamudio J. Inspiration or Thinspiration: the Association Among Problematic Internet Use, Exercise Dependence, and Eating Disorder Risk. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2018;16(5):1113–1124. doi: 10.1007/s11469-017-9834-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk M, Lalanne C, Berthoz S, Kern L, Godart N. Problematic Exercise in Anorexia Nervosa: Testing Potential Risk Factors against Different Definitions. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD. Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: Towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012 January;16:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48(1):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier V, Bolognini M, Plancherel B, Halfon O. Sensation seeking: a personality trait characteristic of adolescent girls and young women with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2000;8(3):245–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0968(200005)8:3<245::AID-ERV308>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online. 2003;8 [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CC, Mazzeo SE. Calorie counting and fitness tracking technology: Associations with eating disorder symptomatology. Eating Behaviors. 2017;26:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater A, Halliwell E, Jarman H, Gaskin E. More than Just Child’s Play: An Experimental Investigation of the Impact of an Appearance-Focused Internet Game on Body Image and Career Aspirations of Young Girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46(9):2047–2059. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0659-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smink FRE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2012;14(4):406–414. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Hames JL, Joiner TE. Status Update: Maladaptive Facebook usage predicts increases in body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;149(1-3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternheim L, Danner U, van Elburg A, Harrison A. Do anxiety, depression, and intolerance of uncertainty contribute to social problem solving in adult women with anorexia nervosa? Brain and Behavior. 2020 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternheim L, Konstantellou A, Startup H, Schmidt U. What does uncertainty mean to women with anorexia nervosa An interpretative phenomenological analysis. European Eating Disorders Review. 2011;19(1):12–24. doi: 10.1002/erv.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternheim L, Startup H, Schmidt U. An experimental exploration of behavioral and cognitive-emotional aspects of intolerance of uncertainty in eating disorder patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(6):806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: Survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10-15 years in a prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(4):339–360. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199712)22:4<339::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z. The relationship between Internet addiction and bulimia in a sample of Chinese college students: Depression as partial mediator between Internet addiction and bulimia. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2013;18(3):233–243. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchanturia K, Anderluh MB, Morris RG, Rabe-Hesketh S, Collier DA, Sanchez P, Treasure JL. Cognitive flexibility in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10(4):513–520. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704104086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Miller J. The internet and adolescent girls’ weight satisfaction and drive for thinness. Sex Roles. 2010;63(1):79–90. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9789-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetGirls: The internet, facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46(6):630–633. doi: 10.1002/eat.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Slater A. Facebook and body image concern in adolescent girls: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2017;50(1):80–83. doi: 10.1002/eat.22640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image. 2015;15:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J, Zipfel S, Micali N, Wade T, Stice E, Claudino A, Wentz E, et al. Anorexia nervosa. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015 November 26;1:1–21. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwater ML, Mancini F, Gorka AX, Shapleske J, Serfontein J, Grillon C, Fletcher PC, et al. Prefrontal responses during proactive and reactive inhibition are differentially impacted by stress in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. BioRxiv Preprint. 2019 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.27.968719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K RStudio. [Retrieved April 24, 2020];A Grammar of Data Manipulation [R package dplyr version 085] 2020 https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr . [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: Aetiology, assessment, and treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:1099–1111. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]