Abstract

Background

In parallel to the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome, the prevalence of hepatic steatosis has also increased dramatically worldwide. Hepatic steatosis is a major risk factor of hepatic cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Circulating levels of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) have been positively associated with the metabolic syndrome. However, the association between PCSK9 and the liver function is still controversial.

Objective

The objective of this study is to investigate the association between circulating PCSK9 levels and the presence of hepatic steatosis, as well as with liver biomarkers in a cohort of healthy individuals.

Methods

Total PCSK9 levels were measured by an in-house ELISA using a polyclonal antibody. Plasma albumin, alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, total bilirubin and GGT were measured in 698 individuals using the COBAS system. The presence of hepatic steatosis was assessed using ultrasound liver scans.

Results

In a multiple regression model adjusted for age, sex, insulin resistance, body mass index and alcohol use, circulating PCSK9 level was positively associated with albumin (β=0.102, P=0.008), alkaline phosphatase (β=0.201, P<0.0001), ALT (β=0.238, P<0.0001), AST (β=0.120, P=0.003) and GGT (β=0.103, P=0.007) and negatively associated with total bilirubin (β= -0.150, P<0.0001). Tertile of circulating PCSK9 was also associated with hepatic steatosis (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.05-2.08, P=0.02).

Conclusion

Our data suggest a strong association between PCSK9 and liver biomarkers as well as hepatic steatosis. Further studies are needed to explore the role of PCSK9 on hepatic function.

Keywords: Liver, hepatic steatosis, PCSK9, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a spectrum of progressive liver diseases that begins with an aberrant deposition of triglycerides (TG) in the hepatocytes (hepatic steatosis). Hepatic steatosis is defined as the presence of triglycerides droplets in more than ~ 5% of hepatocytes [1,2]. In some cases, the disease progresses to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterized by hepatocyte ballooning and the presence of inflammation, with or without collagen deposition (fibrosis). NASH can then progress in up to 1/3 of cases to cirrhosis, which is a major risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure [3].

The worldwide prevalence of NAFLD has been estimated to be around 25-35% [4,5]. NAFLD represents the most frequent cause of liver enzymes elevation in plasma [6].

Hepatic steatosis occurs when there is an increased input or synthesis of triglycerides in the liver and/or a decreased output of triglycerides from the liver. The principal modifiable risk factors for the development of NAFLD include obesity, insulin resistance, diet (in particular, carbohydrate or fructose excess) and sedentary lifestyle [5, 7–9]. Hepatic steatosis is now recognized as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) [10–12]. Similar to the MetS, NAFLD has also been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes [13].

To date, the sole effective treatment recommended for NAFLD remains weight loss via caloric restriction and exercise [14].

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a key modulator of the degradation of the LDL receptor (LDLR) [15]. Gain-of-function mutations in PCSK9 have been associated with familial hypercholesterolemia and increased cardiovascular risk whereas loss-of-function mutations have been associated with low LDL-C and cardiovascular risk [16]. Furthermore, plasma PCSK9 as been independently associated with each individual components of the lipid profile, the stronger associations being with IDL and triglycerides [17,18]. Since PCSK9 has been positively associated with the MetS, as well as with the individual MetS components and insulin resistance [17,19], it is logical to assume that PCSK9 would also be associated with the presence of NAFLD or with anomalies in liver enzymes.

However, some controversies exist in the literature concerning the effect of PCSK9 on the liver function, both for studies conducted in mice [20–22] and in humans. Indeed, several small case report studies have previously linked the presence of PCSK9 loss-of-function mutation with the presence of liver steatosis [23–25], whereas other authors report a normal liver function or perhaps even protection against steatosis in PCSK9 loss-of-function carriers [26,27]. In PCSK9 inhibitors trials, no liver adverse effects have been reported to date. Furthermore, in FOURIER trial, there was no difference between the experimental and the control groups concerning the frequency of aminotransferase level > 3 times the upper limit of the normal range [28]. Similarly, in studies evaluating the association between circulating plasma PCSK9 levels and the presence of hepatic steatosis, some studies reported a positive association [29,30], whereas others did not detect any effect of plasma PCSK9 on hepatic steatosis or circulating liver enzymes [31]. The objectives of the present study is therefore to investigate the association between circulating PCSK9 and circulating liver biomarkers as well as the presence of hepatic steatosis in a large cohort of Kenyan individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Recruitment

The cross-sectional Kenya Diabetes Study, conducted between August 2005 and January 2006, comprised a total cohort of 1459 Kenyans individuals from three rural districts and the capital city of Nairobi. The study participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, following information given at local community meetings. The local social mobilizers who recruited the participants described the study as a diabetes investigation. A more detailed description of the selection procedure has been presented elsewhere [32,33]. Inclusion criteria were ≥ 17 years of age and being Luo, Kamba, or Maasai in the rural districts whereas the urban population was of mixed ethnic origin. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, serious illnesses (e.g.: malaria), inability to walk unassisted and severe mental disease. None of the participants were treated with lipid-lowering medication, oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin therapy. Ten participants were taking hypotensive medication.

In this cohort of the Kenya Diabetes Study, ultrasound liver scans were performed in an opportunity sample of 875 participants. Of these, 767 liver scans were valid. Analyses of circulating PCSK9 was performed in a subgroup of 1338 participants based on the availability of both the biological samples and the clinical data. We then performed the liver biomarkers measurements in participants with both a valid liver scan result and a PCSK9 value, for a total of 698 participants included in the present manuscript.

Information about the study was given to all participants before obtaining their informed consent (written or oral) in their preferred language (Kiswahili, English and/or other local tribal languages). The study was approved by both the National Ethical Review Committee of Kenya and the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics.

2.2. Data Collection and Biochemical Analysis

2.2.1. PCSK9

Total circulating PCSK9 concentration was analysed by an in-house ELISA using a polyclonal antibody against human PCSK9 as previously described [34,35]. For this assay, defrosted samples were used. Measurements were performed at the Montreal Clinical Research Institute (Montreal, Canada).

2.2.2. Liver Biomarkers

Albumin, ALP, ALT, AST, total bilirubin and GGT were measured by an automated analyzer (COBAS INTEGRA 400, Roche Diagnostic) on defrosted samples. Measurements were performed at the Montreal Clinical Research Institute (Montreal, Canada).

2.2.3. Hepatic steatosis

The presence of hepatic steatosis has been assessed using ultrasound liver scans. This method is semi-quantitative and allows to distinguish between normal liver (score ≤ 4) or mild (score between 5-7), moderate (score between 8-10) and severe (score ≥ 11) steatosis according to standardised criteria. Interpretation of the ultrasound liver scans was done at University of Cambridge by a single reviewer (Cambridge, United Kingdom) [36]. The operator was blinded to all other study measures. In addition, the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) and the fatty liver index (FLI) were calculated as described previously [37,38], where HSI ≥ 36 and FLI ≥ 60 were indicator of hepatic steatosis.

2.2.4. Other Clinical Variables

Method for the measurement of blood pressure, lipid profile, anthropometric measurements and glucose metabolism parameters has been described in details elsewhere [17]. All blood samples were collected in the morning following an 8-h overnight fast. The centrifuged samples were kept on ice in Kenya before to be shipped on dry ice and stored at -80 °C. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using fasting glucose and fasting insulin values. The presence of metabolic syndrome was assessed using the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) 2009 consensus statement criteria [39]. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated. Information concerning alcohol consumption was self-reported by the participants.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis. A statistical significance level was established at P ≤ 0.05. P values are two-sided. Depending on the nature of the data (continuous or categorical), results are presented either as mean +/- standard deviation or n (percentage). For continuous variables with a skewed distribution, data are presented as median with interquartile range (Q1-Q3). Abnormally distributed variables were log-transformed prior to analysis. In order to compare the baseline characteristics between the participants with hepatic steatosis and those without, a Student’s t-test was performed for continuous variables, whereas a Chi2 test was used for categorical variables. The relationship between liver biomarkers and PCSK9 was assessed through linear regression models, whereas the association between the presence of hepatic steatosis and PCSK9 tertiles was determined via logistic regression models. The P value for the prevalence of hepatic steatosis by PCSK9 tertiles was obtained by a Chi2 analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the study cohort

The participants’ characteristics according to the presence or the absence of hepatic steatosis are presented in Table 1. The presence of hepatic steatosis on the ultrasound liver scan was observed in 104 participants (15%). For the remaining individuals of the study cohort, no sign of hepatic steatosis was observed (n=594 (85%)). The group with hepatic steatosis was five years older and had significantly lower proportion of men vs women (28% vs 44%, respectively) than the group without hepatic steatosis (P<0.05). In addition, we observed significant differences between groups for many metabolic parameters. The group with hepatic steatosis had higher BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting glucose, insulinemia, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), HOMA-IR, total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, PCSK9, prevalence of self-reported diabetes, prevalence of metabolic syndrome and average number of MetS criteria and lower HDL-C than the group without hepatic steatosis (P<0.05). There were significant differences between groups for only three liver biomarkers. Indeed, the group with hepatic steatosis had lower albumin, AST and total bilirubin levels than the group without hepatic steatosis (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between groups concerning alcohol consumption (P=0.46).

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics.

| Variables | Absence of hepatic steatosis (n=594) | Presence of hepatic steatosis (n=104) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 37 ± 11 | 42 ± 11 | <0.0001 |

| Sex (men (%)) | 259 (44%) | 29 (28%) | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20 (18-23) | 27 (23-32) | <0.0001 |

| WC (cm) | 74.7 (70.2-80.3) | 93.2 (82.3-102.5) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 118 (110-127) | 126 (116-139) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74 (67-80) | 79 (73-86) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.4 (4.0-4.7) | 4.5 (4.1-5.0) | 0.009 |

| Fasting insulinemia (pmol/L) | 22 (15-33) | 39 (25-59) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.0 (4.7-5.3) | 5.4 (5.0-5.9) | 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 1.2 (0.7-1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.83 ± 0.90 | 4.37 ± 1.11 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.25 ± 0.74 | 2.74 ± 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.15 ± 0.29 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 0.003 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.82 (0.66-1.04) | 1.02 (0.78-1.50) | <0.0001 |

| PCSK9 (ng/mL) | 141.4 (118.4-170.4) | 157.9 (131.7-189.5) | 0.001 |

| Self-reported diabetes (n(%)) | 9/579 (2%) | 5/103 (5%) | 0.05 |

| Self-reported CVD (n(%)) | 37/562 (7%) | 4/103 (4%) | 0.38 |

| MetS (n(%)) | 42/577 (7%) | 31/99 (31%) | <0.0001 |

| Number of MetS criteria | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 43.36 ± 4.33 | 42.36 ± 4.69 | 0.03 |

| ALP (U/L) | 74.6 (61.3-92.8) | 78.7 (67.0-95.8) | 0.16 |

| ALT (U/L) | 7.8 (6.0-9.9) | 7.5 (5.6-10.6) | 0.93 |

| AST (U/L) | 19.5 (16.7-23.4) | 18.1 (14.9-22.1) | 0.004 |

| Total bilirubin (umol/L) | 4.5 (3.0-7.4) | 3.8 (2.3-5.9) | 0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 17.6 (12.4-26.7) | 20.2 (12.7-30.1) | 0.16 |

| Alcohol use (n(%)) | 58/557 (10%) | 8/100 (8%) | 0.46 |

Data for continuous normally distributed variables are expressed as mean +/- SD, whereas continuous logarithmic variables are expressed as median (interquartile range).

Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (n (%)). Bold type indicates P value ≤ 0.05. BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; SD, standard deviation; WC, waist circumference.

3.2. Relation between circulating PCSK9 levels and liver biomarkers

The associations between PCSK9 and liver biomarkers according to several regression models are presented in Table 2. In an unadjusted model, only ALP, ALT and total bilirubin were significantly associated with PCSK9. When adjustment for age and sex (Model 2) or for age, sex, HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use (Model 3) were applied, all liver biomarkers were strongly associated with PCSK9 (In model 3: β=0.102 for albumin, β= 0.201 for ALP, β=0.238 for ALT, β=0.120 for AST, β=-0.150 for total bilirubin and β=0.103 for GGT, P values < 0.05).

Table 2. Relation between circulating PCSK9 and liver biomarkers.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver biomarkers |

Standardized coefficient (β) |

P value | Standardized coefficient (β) |

P value | Standardized coefficient (β) |

P value |

| Albumin | -0.004 | 0.91 | 0.105 | 0.005 | 0.102 | 0.008 |

| ALP | 0.162 | < 0.001 | 0.213 | < 0.001 | 0.201 | <0.0001 |

| ALT | 0.143 | < 0.001 | 0.216 | < 0.001 | 0.238 | <0.0001 |

| AST | 0.041 | 0.28 | 0.085 | 0.03 | 0.120 | 0.003 |

| Total bilirubin | -0.242 | < 0.001 | -0.146 | < 0.001 | -0.150 | <0.0001 |

| GGT | 0.052 | 0.18 | 0.104 | 0.005 | 0.103 | 0.007 |

P values for linear regression analysis. Bold type indicates P value ≤ 0.05.

Model 1: Uncorrected

Model 2: Corrected for age and sex

Model 3: Corrected for age, sex, HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use.

PCSK9 : proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

3.3. Relation between circulating PCSK9 levels and the presence of hepatic steatosis

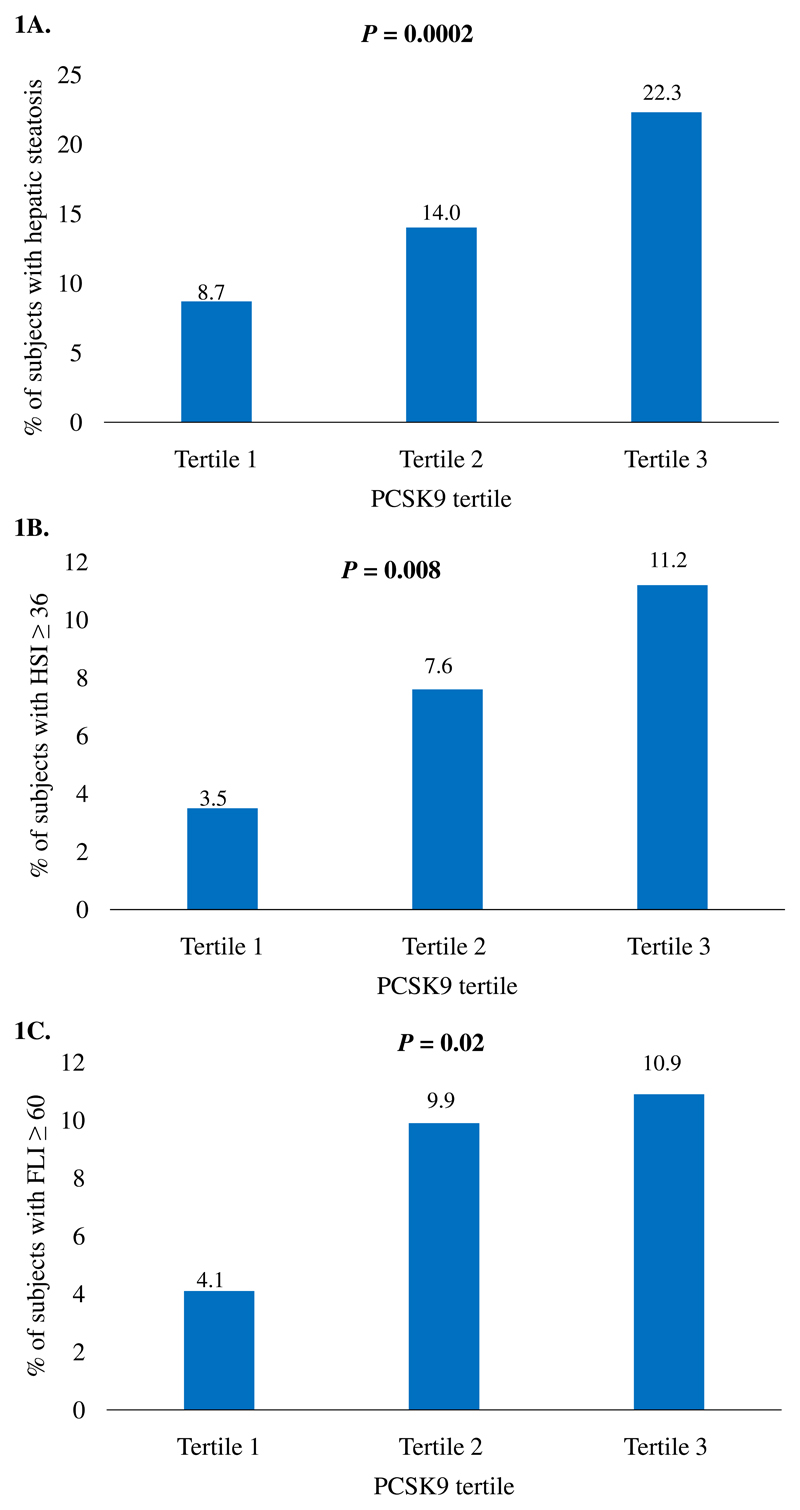

The associations between PCSK9 tertiles and the presence of hepatic steatosis according to several regression models are presented in Table 3. PCSK9 was significantly associated with the presence of hepatic steatosis in the unadjusted model (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.32-2.28, P<0.0001) as well as in the model adjusted for age, sex, HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.05-2.08, P=0.02). The prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the three tertiles was 8.7% in the lowest tertile, 14.0% in the intermediate tertile and 22.3% in the highest tertile (Figure 1A). Similar associations were observed for the prevalence of HSI ≥ 36 (P=0.008) and FLI ≥ 60 (P=0.02) between PCSK9 tertiles (Figure 1 B and C). The association between LDL-C and PCSK9 levels was statistically significant in the group without hepatic steatosis (β=0.224, P<0.0001), but not in subjects with hepatic steatosis (β=0.161, P=0.11) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3. Relation between tertiles of circulating PCSK9 and hepatic steatosis.

| Prediction of hepatic steatosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Models | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Model 1 | 1.74 | 1.32-2.28 | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1.50 | 1.13-2.00 | 0.005 |

| Model 3 | 1.48 | 1.05-2.08 | 0.02 |

P values for logistic regression analysis. Bold type indicates P value ≤ 0.05.

Model 1: Uncorrected

Model 2: Corrected for age and sex

Model 3: Corrected for age, sex, HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use.

PCSK9 : proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of A) hepatic steatosis (ultrasound scan), B) HSI ≥ 36 and C) FLI ≥ 60 by tertile of circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). HSI: hepatic steatosis index; FLI: fatty liver index.

4. Discussion

In the present study, including 698 participants from the Kenya Diabetes Study, we demonstrated that circulating PCSK9 levels were strongly associated with all circulating liver biomarkers as well as the presence of hepatic steatosis, as determined by ultrasound liver scans, HSI and FLI indexes. These associations were independent of insulin resistance status, although the strength of the association between PCSK9 and hepatic steatosis was somewhat decreased when corrected for HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use. This suggests that PCSK9 could have and indirect effect on hepatic steatosis via insulin resistance as well as a direct independent effect. In a previous publication in the same cohort, PCSK9 was also associated with the presence of metabolic syndrome, as well as with each individual components of the lipid profile [17].

Elevated level of liver enzymes is considered as an indicator of abnormal liver function. Thus, the screening for NAFLD stages using liver biopsy is usually reserved for individuals with elevated levels of circulating liver enzymes. However, liver enzymes are not systematically correlated with the level of liver fat and could be linked to other cardiometabolic pathways. For example, ALT levels would be normal in the majority (79%) of subjects who have increased liver fat [5]. In the present cohort, when the associations between the presence of hepatic steatosis and transaminases level were corrected for age, sex, HOMA-IR, BMI and alcohol use, these associations were non-significant (data not shown). Also, there exists some evidence suggesting that GGT itself would be associated with an increased incidence of new-onset metabolic syndrome and an increased incidence of CVD, independently of traditional risk factors [40]. However, the mechanisms underlying the action of GGT on metabolic risk remain unclear. Another group also reported a positive association between GGT and PCSK9 after adjustment for gender, age, type of diabetes, statin treatment, BMI, systolic blood pressure and HbA1c [41]. Further investigations should be done to improve our understanding of the independent role of PCSK9 on liver biomarkers.

Ruscica et al (2016) observed an independent association between circulating PCSK9 and severity of steatosis in a cohort of 201 subjects who underwent liver biopsy for suspected NASH. The authors, as well as others, [42] suggested that this association would be explained by an activation of hepatic lipogenesis by PCSK9. However, they did not correct for the insulin resistance status or the presence of metabolic syndrome in the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, an association between circulating PCSK9 and ALT was found in univariate analysis, but the association was no longer significant in multivariate analysis [29]. In another study, Cariou et al [30] observed that a short-term high fructose diet was associated with a 27-93% increase in circulating PCSK9 levels in healthy volunteers and that PCSK9 concentration was positively associated with insulin resistance, liver steatosis and VLDL-TG. However, the authors performed Spearman’s correlation test, which is a univariate association. Therefore, whether the association between PCSK9 and hepatic steatosis is independent of insulin resistance in this study is not known. Furthermore, this association was not observed under baseline conditions [30]. On the other hand, in a study from the same group, there was no association between circulating PCSK9 and liver fat content, histological markers of NASH or transaminases level in a cohort of 478 high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome and without lipid-lowering therapy [31]. The prevalence of hepatic steatosis found in our cohort is lower than the worldwide prevalence of 25-35% [4,5]. However, in a meta-analysis of NAFLD prevalence stratified by region, a pooled prevalence of 14% was found for Africa, which is in accordance with our own observations [4]. In the group with hepatic steatosis, 31% had MetS compared to 7% in the group without hepatic steatosis.

The limitations of the present study include the method used to assess the presence of steatosis. Indeed, even if the ultrasound liver scan allows distinguishing between normal liver or mild, moderate and severe steatosis, the liver biopsy represents the gold standard for a proper diagnostic of the NAFLD stage. Also, the interpretation of the ultrasound scan has the disadvantage to be operator-dependent. Furthermore, our data concerning alcohol consumption are self-reported by the participants and under-reporting was suspected, especially among the women. Therefore, it was not possible to do adequate statistical correction for this variable. Similarly, we did not assess the presence of secondary causes of steatosis, such as the presence of other hepatic diseases that can cause steatosis and genetic predispositions. In addition, data on the presence of HIV/AIDS or other inflammatory or viral conditions that could influence plasma PCSK9 levels or hepatic function have not been systematically collected. Indeed, elevation of liver enzymes in HIV patients is frequent due to several reasons including antiretroviral therapy, coinfection with hepatitis B or C (up to 30% of cases), as well as concomitant alcohol, cocaine, or methamphetamine use [43]. Finally, because the study participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, and because only certain ethnic groups were selected, the sample probably does not represent the whole general Kenyan adult population. Therefore, the generalizability to other populations or ethnic groups needs to be confirmed. The major strength of our study is that the entire cohort was free of lipid-lowering therapy, oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin therapy.

5. Conclusions

Results from our study confirm the association between PCSK9 and hepatic steatosis previously reported in other studies. Our study suggests that this effect could be mediated in part via the association between PCSK9 and insulin resistance as well as by a direct effect of PCSK9 on hepatic steatosis. Further research would be necessary to investigate the clinical implications of the association between PCSK9 and hepatic steatosis in the context of the use of PCSK9 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the Montreal Clinical Research Institute (IRCM) research team and the nursing staff for their everyday help, support and implication. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to all participants, the local chiefs and sub-chiefs, the local elder councils, and district politicians as well as local laboratory technicians and assistants for excellent work throughout the data collection period. The authors acknowledge the permission by the Director of KEMRI to publish this article.

7. Funding Sources

This work was supported by The Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Networks of Excellence [grant number 13CVD03], DANIDA [J. no.104.DAN.8–871, RUF project no. 91202], Cluster of International Health Grant (University of Copenhagen) and generous support for laboratory analyses from Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, Denmark and Section of Global Health, University of Copenhagen. The study funders had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

8. Disclosures

A.B. received research grants from Merck Frosst, Amgen, Sanofi, Astra Zeneca and the Fondation Leducq. He has participated in clinical research protocols from Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., The Medecines Company, Amgen, Acasti Pharma Inc., Novartis, Sanofi, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Astra Zeneca, Akcea and Merck Frosst. He has served on advisory boards and received honoraria for symposia from Amgen, Akcea and Sanofi.

S.B. has participated in clinical research protocols from Akcea, The Medecines Company and Sanofi. She has served on advisory boards for Akcea, Novo Nordisk, Merck Frosst, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Sanofi and Amgen and received honoraria for symposia from Akcea, Sanofi-aventis, Merck Frosst, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim.

D.L.C. has received consultancy payment from Novo Nordisk A/S.

M.P., D.G., A.C., A.P., L.K., N.G.S., E.D.L.R. and J.J.R. have nothing to declare.

The authors' contributions were as follows: All authors contributed to the discussion, analysis and interpretation of data and have reviewed the article for the intellectual content. M.P performed statistical analysis and has drafted the manuscript. All authors have approved the final article. A.B. had primary responsibility for final content.

References

- [1].Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1202–19. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, Browning JD, Reingold JS, Grundy S, Hobbs HH, Dobbins RL. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(2):E462–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00064.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Argo CK, Caldwell SH. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13(4):511–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1387–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):960–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332(6037):1519–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Semple RK, Sleigh A, Murgatroyd PR, Adams CA, Bluck L, Jackson S, Vottero A, Kanabar D, Charlton-Menys V, Durrington P, Soos MA, et al. Postreceptor insulin resistance contributes to human dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(2):315–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI37432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhu X, Bian H, Gao X. The Potential Mechanisms of Berberine in the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecules. 2016;21(10):E1336. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Bugianesi E, Lenzi M, McCullough AJ, Natale S, Forlani G, Melchionda N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1844–50. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kotronen A, Yki-Järvinen H. Fatty liver: a novel component of the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(1):27–38. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bedogni G, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Tiribelli C, Marchesini G, Bellentani S. Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology. 2005;42(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Armstrong MJ, Adams LA, Canbay A, Syn WK. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1174–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.26717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55(6):2005–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Marcinkiewicz J, Jasmin SB, Stifani S, Basak A, Prat A, Chretien M. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(3):928–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335507100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Awan Z, Baass A, Genest J. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): lessons learned from patients with hypercholesterolemia. Clin Chem. 2014;60(11):1380–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.225946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Paquette M, Luna Saavedra YG, Chamberland A, Prat A, Christensen DL, Lajeunesse-Trempe F, Kaduka L, Seidah NG, Dufour R, Baass A. Association Between Plasma Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 and the Presence of Metabolic Syndrome in a Predominantly Rural-Based Sub-Saharan African Population. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15(8):423–9. doi: 10.1089/met.2017.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kwakernaak AJ, Lambert G, Dullaart RP. Plasma proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 is predominantly related to intermediate density lipoproteins. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(7-8):679–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Awan Z, Dubuc G, Faraj M, Dufour R, Seidah NG, Davignon J, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Baass A. The effect of insulin on circulating PCSK9 in postmenopausal obese women. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(12):1033–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rashid S, Curtis DE, Garuti R, Anderson NN, Bashmakov Y, Ho YK, Hammer RE, Moon YA, Horton JD. Decreased plasma cholesterol and hypersensitivity to statins in mice lacking Pcsk9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(15):5374–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501652102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zaid A, Roubtsova A, Essalmani R, Marcinkiewicz J, Chamberland A, Hamelin J, Tremblay M, Jacques H, Jin W, Davignon J, Seidah NG, et al. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): hepatocyte-specific low-density lipoprotein receptor degradation and critical role in mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):646–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Demers A, Samami S, Lauzier B, Des Rosiers C, Ngo Sock ET, Ong H, Mayer G. PCSK9 Induces CD36 Degradation and Affects Long-Chain Fatty Acid Uptake and Triglyceride Metabolism in Adipocytes and in Mouse Liver. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(12):2517–25. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fasano T, Cefalù AB, Di Leo E, Noto D, Pollaccia D, Bocchi L, Valenti V, Bonardi R, Guardamagna O, Averna M, Tarugi P. A novel loss of function mutation of PCSK9 gene in white subjects with low-plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(3):677–81. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000255311.26383.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cariou B, Ouguerram K, Zaïr Y, Guerois R, Langhi C, Kourimate S, Benoit I, Le May C, Gayet C, Belabbas K, Dufernez F, et al. PCSK9 dominant negative mutant results in increased LDL catabolic rate and familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(12):2191–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Baragetti A, Balzarotti G, Grigore L, Pellegatta F, Guerrini U, Pisano G, Fracanzani AL, Fargion S, Norata GD, Catapano AL. PCSK9 deficiency results in increased ectopic fat accumulation in experimental models and in humans. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(17):1870–7. doi: 10.1177/2047487317724342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kotowski IK, Pertsemlidis A, Luke A, Cooper RS, Vega GL, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. A spectrum of PCSK9 alleles contributes to plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(3):410–22. doi: 10.1086/500615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Di Filippo M, Vokaer B, Seidah NG. A case of hypocholesterolemia and steatosis in a carrier of a PCSK9 loss-of-function mutation and polymorphisms predisposing to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(4):1101–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ruscica M, Ferri N, Macchi C, Meroni M, Lanti C, Ricci C, Maggioni M, Fracanzani AL, Badiali S, Fargion S, Magni P, et al. Liver fat accumulation is associated with circulating PCSK9. Ann Med. 2016;48(5):384–91. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2016.1188328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cariou B, Langhi C, Le Bras M, Bortolotti M, Lê KA, Theytaz F, Le May C, Guyomarc’h-Delasalle B, Zaïr Y, Kreis R, Boesch C, et al. Plasma PCSK9 concentrations during an oral fat load and after short term high-fat, high-fat high-protein and high-fructose diets. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2013;10(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wargny M, Ducluzeau PH, Petit JM, Le May C, Smati S, Arnaud L, Pichelin M, Bouillet B, Lannes A, Blanchet O, Lefebvre P, et al. Circulating PCSK9 levels are not associated with the severity of hepatic steatosis and NASH in a high-risk population. Atherosclerosis. 2018;278:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Christensen DL, Eis J, Hansen AW, Larsson MW, Mwaniki DL, Kilonzo B, Tetens I, Boit MK, Kaduka L, Borch-Johnsen K, Friis H. Obesity and regional fat distribution in Kenyan populations: impact of ethnicity and urbanization. Ann Hum Biol. 2008;35(2):232–49. doi: 10.1080/03014460801949870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Christensen DL, Friis H, Mwaniki DL, Kilonzo B, Tetens I, Boit MK, Omondi B, Kaduka L, Borch-Johnsen K. Prevalence of glucose intolerance and associated risk factors in rural and urban populations of different ethnic groups in Kenya. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84(3):303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Baass A, Dubuc G, Tremblay M, Delvin EE, O’Loughlin J, Levy E, Davignon J, Lambert M. Plasma PCSK9 is associated with age, sex, and multiple metabolic markers in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. Clin Chem. 2009;55(9):1637–45. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.126987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dubuc G, Tremblay M, Paré G, Jacques H, Hamelin J, Benjannet S, Boulet L, Genest J, Bernier L, Seidah NG, Davignon J. A new method for measurement of total plasma PCSK9: Clinical applications. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:140–9. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900273-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].De Lucia Rolfe E, Brage S, Sleigh A, Finucane F, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Ong KK, Forouhi NG. Validity of ultrasonography to assess hepatic steatosis compared to magnetic resonance spectroscopy as a criterion method in older adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, Lee CH, Yang JI, Kim W, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Cho SH, Sung MW, Lee HS. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7):503–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Passalacqua M, Castiglione A, Tiribelli C. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC, Jr, International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee DS, Evans JC, Robins SJ, Wilson PW, Albano I, Fox CS, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Gamma glutamyl transferase and metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and mortality risk: the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(1):127–33. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251993.20372.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cariou B, Le Bras M, Langhi C, Le May C, Guyomarc’h-Delasalle B, Krempf M, Costet P. Association between plasma PCSK9 and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211(2):700–2. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tavori H, Giunzioni I, Predazzi IM, Plubell D, Shivinsky A, Miles J, Devay RM, Liang H, Rashid S, Linton MF, Fazio S. Human PCSK9 promotes hepatic lipogenesis and atherosclerosis development via apoE- and LDLR-mediated mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110(2):268–78. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pol S, Lebray P, Vallet-Pichard A. HIV infection and hepatic enzyme abnormalities: intricacies of the pathogenic mechanisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S65–72. doi: 10.1086/381499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.