Synopsis

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) can arise sporadically or as part of familial syndromes. Genetic studies of hereditary syndromes and whole exome sequencing analysis of sporadic PNETs have revealed the roles of some genes involved in PNET tumorigenesis. The most commonly mutated gene in PNETs is the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene, whose encoded protein menin, has roles in transcriptional regulation, genome stability, DNA repair, protein degradation, cell motility and adhesion, microRNA biogenesis, cell division, cell cycle control and epigenetic regulation. Therapies targeting epigenetic regulation and MEN1 gene replacement have been reported to be effective in pre-clinical models.

Keywords: MEN1, VHL, PNETs, menin, mTOR, epigenetic, SSTRs, RAS

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), which account for 1-2% of all pancreatic neoplasms, are pathologically heterogeneous and consist of epithelial cells with phenotypic and ultrastructural neuroendocrine differentiation1,2. PNETs may be classified according to their proliferation, which is assessed by the Ki-67 index or mitotic count, with: well-differentiated PNETs grade 1 (G1) having a Ki-67 index of <3% or mitotic count of <2 mitoses/10 high-power fields (HPF); well-differentiated grade 2 (G2) PNETs having a Ki-67 index of 3-20% or 2-20 mitoses/10 HPF; and well-differentiated grade 3 (G3) PNETs or poorly differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas (PNECs) having a Ki-67 index of >20% and >20 mitoses/10 HPF1,3,4. The incidence of PNETs, also known as pancreatic islet cell tumors, has doubled between 1973 and 2004 from 0.16 to 0.33 per 100,000 individuals, and this may in part be due to improvements in diagnostic imaging and detection, and autopsy studies have shown that as many as 0.8%-10% of individuals have PNETs2,5–7. PNETs may secrete hormones or vasoactive substances, such as gastrin, insulin, glucagon or vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and be associated with clinical symptoms due to the hormonal over production, or they may be non-secreting (i.e. non-functional) and clinically present often with locally advanced or metastatic disease8.

Treatments for primary PNETs include surgery, while nonresectable PNETs and metastases are treated with biotherapies that include somatostatin analogues, inhibitors of receptors and monoclonal antibodies, chemotherapy and radionuclide therapy9. The median survival time for patients with PNETs is ~3.6 years10, while prognosis for patients whose PNETs have metastasised is poor with a survival of 1-3 years5,6,11,12 However, the molecular pathology of well-differentiated PNETs is not sufficiently well understood for prediction of: the aggressiveness of individual tumors that would reliably identify patients who would benefit from early therapy; or indolent disease for which the risk to benefit ratio of treatment may not be advantageous for patients13. Thus, improved understanding of the molecular basis of PNETs as well as better treatments are required. Recent preclinical studies have identified new cellular pathways and therapeutic targets for treating PNETs, and these include epigenetic modification, the β-catenin/Wnt pathway, hedgehog signaling, somatostatin receptors and MEN1 gene replacement therapy. This chapter will review these advances in the molecular genetics of PNETs that have stemmed from studies of hereditary syndromes associated with PNETs, as well as sporadic PNETs, and the cellular pathways that these studies have identified for therapeutic approaches.

Pnets In Hereditary Syndromes

PNETs most frequently (~90%) arise as a non-familial isolated endocrinopathy (i.e. sporadically), but they can also occur as part of a complex familial syndrome that includes multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), von Hippel Lindau disease (VHL), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and the tuberous sclerosis (TS) complex1,2,9. Indeed, PNETs have been reported to occur in 30-80% of MEN1 patients, >15% of VHL patients, <10% of NF1 patients and <1% of patients with TS9. These hereditary tumor syndromes will be briefly reviewed, as they provide molecular insights in PNET development.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (Men1)

The most common hereditary syndrome associated with PNETs is MEN1, which is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by the combined occurrence of two or more tumors involving the parathyroids, pancreatic islets, anterior pituitary and adrenals14,15. In MEN1, PNETs are typically multiple whilst in sporadic cases tumors are generally solitary masses. Patients with MEN1 syndrome have germline mutations in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene, which is located on chromosome 11q13 and encodes a 610 amino acid protein, menin. MEN1 germline mutations are found in >90% of MEN1 patients and comprise whole or partial gene deletions, frameshift deletions or insertions, in-frame deletions or insertions, and splice site, missense, and nonsense mutations, which result in a functional deficiency of menin16,17. MEN1 tumors have somatic mutations as well as germline mutations consistent with the Knudson two-hit hypothesis for the role of tumor suppressor genes in oncogenesis, and in the majority (>90%) of MEN1 tumors the somatic abnormality is loss of heterozygosity (LOH), with the remaining 10% having intragenic deletions or point mutations17–19.

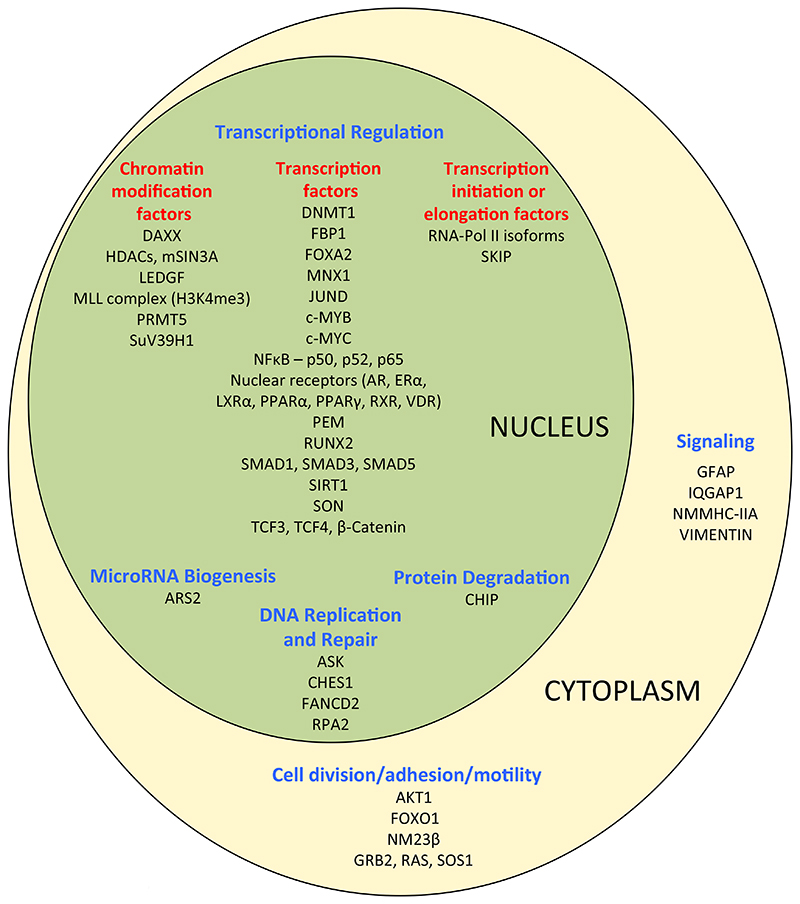

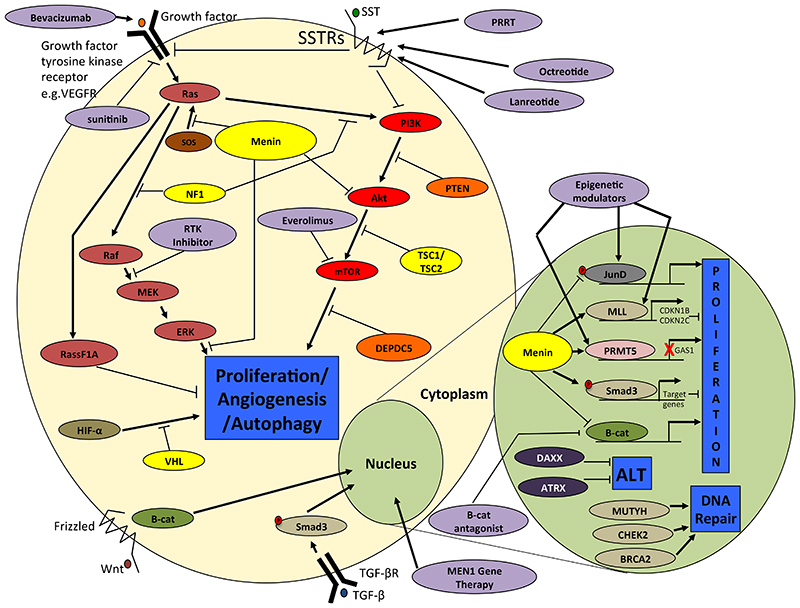

Menin is a ubiquitously expressed protein that functions as a nuclear scaffold protein that interacts with >40 interacting proteins (Figure 1), thereby enabling it to have multiple roles in pathways of cellular proliferation by influencing transcriptional regulation, genome stability, DNA repair, protein degradation, cell motility and adhesion, microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis, cell division, cell cycle control and epigenetic regulation17,20–25. For example, menin inhibits: wingless integration 1 (Wnt) signaling by transferring β-catenin from the nucleus, which reduces cell proliferation21,26; the activity of JunD proto-oncogene (JunD) by blocking its phosphorylation and therefore potentially subsequent interaction with co-activators22,27, causing JunD to prevent rather than promote cell growth28; and Hedgehog pathway signaling, which influences several functions including tumorigenesis, by recruitment of a protein arginine methyltransferase (PRMT5), which inactivates the Hedgehog pathway promoter growth arrest specific 1 (Gas1) gene29 (Figure 2). In addition, menin interacts with the mixed lineage leukaemia protein 1 (MLL1) histone methyltransferase complex to methylate histone H3 (Lys4), causing chromatin modification and increased transcriptional activity of genes including those encoding the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p27 and p18, which are involved in cell cycle regulation30,31 (Figure 2). Menin also promotes the cytostatic effects of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) by interaction with the small body size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (Smad) pathway32–34 (Figure 2), as well as interacting with nuclear factor kappa B subunit (NF-kB) proteins to modulate NF-kB transactivation35. Furthermore, menin can prevent the interaction between the GTPase Kirsten rat Sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (K-RAS) and sons of sevenless (SOS) that is essential for K-RAS activation36. Moreover, in murine pancreatic β-cells menin has been shown to activate opposing K-RAS pathways that comprise a proliferative pathway, likely via regulation of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation, and an anti-proliferative pathway via ras association domain family member 1 (RASSF1A)37. Thus, menin is considered to interact with K-RAS to block the MAPK/ERK pathway, thereby inhibiting proliferation, and menin loss removes this inhibition and leads to increased cell proliferation37. Menin also acts as a suppressor of ERK-dependent phosphorylation of target proteins38 (Figure 2). In addition, somatostatin receptor (SSTR) modulation of proliferation may also occur through K-RAS signaling, thereby highlighting the importance of K-RAS signaling in PNETs, and indicating that menin may play a possible role in SSTR downstream signaling39 (Figure 2). Furthermore menin is an inhibitor of the phosphatidtylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/viral oncogene of Akt8 retrovirus (Akt) (also known as protein kinase B (PKB)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (PI3K/Akt/mTOR)) signaling pathway, by binding to Akt and preventing its translocation to the plasma membrane40 (Figure 2). The mTOR pathway regulates cell proliferation, cell metabolism, survival, motility and autophagy41.

Figure 1.

Menin interacting proteins. More than 40 different proteins have been reported to interact with menin, which is a multifunctional protein with roles in: transcriptional regulation as a co-repressor or co-activator (via interactions with chromatin modifying proteins, transcription factors and transcription initiation or elongation proteins); DNA repair associated with response to DNA damage; cell signaling; cytoskeletal structure; cell division; cell adhesion; or cell motility17,20. DAXX = death domain associated protein; HDACs = histone deacetylases; mSIN3A = SIN3 transcription regulator family member A; LEDGF = lens epithelium-derived growth factor; MLL = mixed lineage leukemia; PRMT5 = protein arginine methyltransferase 5; SUV39H1 = suppressor of variegation 3-9 homolog 1; DNMT1 = DNA methyltransferase 1; FBP1 = fructose bisphosphatase 1; FOXA2 = forkhead box A2; MNX1 = motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1; JUND = JunD proto-oncogene; c-MYB = MYB (myeloblastosis) proto-oncogene; c-MYC = MYC (myelocytomatosis) proto-oncogene; NFκB = nuclear factor kappa B; AR = androgen receptor; ERα = estrogen receptor alpha; LXRα = liver X receptor rlpha; PPARα = peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha; RXR = retinoic X receptor; VDR = vitamin D receptor; PEM = PEM homeobox; RUNX2 = runt related transcription factor 2; SMAD = small body size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog; SIRT = Sirtuin 1; SON = SON DNA binding protein; TCF = transcription factor; SKIP = SKI interacting protein; ARS2 = arsenite-resistance protein 2; CHIP = carboxy terminus of hsp70-interacting protein; ASK = apoptosis signal regulating kinase; CHES1 = checkpoint suppressor 1; FANCD2 = fanconi anemia complementation group D2; RPA2 = replication protein 2; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; IQGAP1 = IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1; NMMHC-IIA = non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA; AKT1 = viral oncogene of Akt8 retrovirus (AKT) serine/threonin kinase 1; FOXO1 = forkhead box O1; NM23β = NME/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2; GRB2 = growth factor receptor bound protein 2; RAS = KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma virus) proto-oncogene; SOS1 = son of sevenless homolog 1

Figure 2.

Major pathways associated with PNET tumor progression. In the nucleus menin interacts with: the transcription factor JunD to prevent its phosphorylation and activation of target genes such as gastrin (GAST); β-catenin mediating its export from the nucleus and inhibiting Wnt signaling; PRMT5 to inactivate the Hedgehog pathway promoter Gas1; and MLL1 and MLL2, and Smad3, which is a TGF- β signaling component, to promote transcription of target genes that reduce cellular proliferation. DAXX and ATRX are responsible for telomere maintenance with genetic mutations leading to the Altered Lengthening of Telomere (ALT) phenotype, while MUTYH, CHEK2 and BRCA2 are involved in DNA repair. In the cytoplasm menin inhibits: the mTOR pathway which regulates cellular proliferation and autophagy by binding to Akt, which are part of RTK and SSTR signaling pathways; and K-RAS induced proliferation by both inhibition of ERK dependent phosphorylation of target proteins and prevention of the SOS/K-RAS interaction. PTEN, TSC1, TSC2 and DEPDC5 are also involved in regulating the mTOR signaling pathway, while NF1 regulates RAS signaling via MEK/ERK and mTOR pathways by regulating the conversion of inactive RasGDP to active RasGTP. VHL is part of a multiprotein complex responsible for ubiquitination and degradation of the α subunits of HIF1 and 2, and thus VHL mutations can lead to stabilisation of HIFs increasing angiogenesis through increased expression of hypoxia-inducible target genes. Targeted therapies (white text in ovals with solid outlines) include mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus; Wnt pathway inhibitors such as β-catenin antagonists; epigenetic modulators; MEN1 gene therapy; RTK inhibitors such as sunitinib; and somatostatin analogues such as octreotide and lanreotide or PRRT. VEGFR = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; SSTRs = somatostatin receptors; SOS = son of sevenless; RAS = KRAS proto-oncogene; Raf = B-Raf proto-oncogene; MEK = mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase 1; ERK = extracellular signal-regulated kinase; RASSF1A = ras association domain family member 1; HIF-α = hypoxia inducible factor alpha; VHL = von hippel lindau; B-cat = β-catenin; PI3K = phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3 kinase; AKT = AKT serine/threonin kinase 1; mTOR = mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase; PTEN = phosphatase and tensin homolog; TSC1/2 = tuberous sclerosis 1/2; DEPDC5 = DEP domain containing protein 5; SMAD = small body size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog; JUND = JunD proto-oncogene; MLL = mixed lineage leukemia; CDKN1B/2C = cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B/2C; PRMT5 = protein arginine methyltransferase 5; GAS1 = growth arrest specific 1; DAXX = death domain associated protein; ATRX = alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-Linked; MUTYH = MutY homolog; CHEK2 = checkpoint kinase 2; BRCA2 = breast cancer 2; Wnt = wingless integration 1; RTK = receptor tyrosine kinase; PRRT = peptide receptor radionuclide therapy.

Von Hippel Lindau (Vhl)

PNETs develop in patients with VHL disease, which is an autosomal dominant disorder with an incidence of 1 in 36000 individuals42. The VHL gene is located on chromosome 3p25 and encodes a protein, von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor (pVHL), involved in the oxygen-sensing pathway that regulates hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs)43. Truncation of the pVHL prevents the ubiquitination of HIF transcription factors leading to expression of target genes favouring angiogenesis (Figure 2). Individuals with VHL disease typically inherit a germline VHL mutation and those cells that acquire a somatic mutation (i.e. the “second hit”) of the wild-type allele develop tumors. VHL germline mutations, which are detected in virtually all VHL patients44,45, comprise missense, frameshift, nonsense, in-frame deletions/insertions, large/complete deletions and splice site abnormalities with mutations located in exon 3 being associated with an increased risk of malignant PNETs45–47. Mouse models of conditional inactivation of Vhl in specific pancreatic cell populations have revealed that a lack of pVHL in pancreatic progenitor cells results in significant postnatal death, and the few surviving mice then develop islet hyperplasia and microcystic adenomas, which are also found to occur in 35-70% of VHL patients48.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (Nf1)

Patients with NF1, which is an autosomal dominant disorder, may develop PNETs. The NF1 tumor suppressor gene is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and encodes the cytoplasmic protein neurofibromin that controls cellular proliferation by inactivating the ras signal transduction pathway49 (Figure 2). Loss of function NF1 mutations lead to increased activity of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways50, and the PNETs that develop have a great potential for malignancy51,52.

Tuberous Sclerosis (Ts)

Patients with TS may develop PNETs such as gastrinomas, insulinomas and non-functioning tumors. TS is an autosomal dominant disease caused by mutations in tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) located on chromosome 9q34 or TSC2 located on chromosome 16p13.3, which encode the hamartin and tuberin proteins, respectively. Mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 can activate the mTOR pathway to increase cell proliferation52,53 (Figure 2).

Sporadic Pnets

The majority of sporadic PNETs are associated with somatic mutations, although some patients with sporadic PNETs may have germline mutations.

Somatic Mutations In Sporadic Pnets

The commonest mutated gene in sporadic PNETs is the MEN1 gene. Thus, 40% of sporadic PNETs have somatic MEN1 mutations, indicating that MEN1 mutations are major drivers in the development of all PNETs (Table 1)13,54. In addition, whole exome and whole genome sequencing studies have identified the involvement of other genes and cellular pathways in chromatin modification, telomere length maintenance, growth control, DNA damage and cell metabolism as well as alterations in gene copy number, chromosomal rearrangements, gene fusions, telomere integrity and miRNAs13,54.

Table 1.

Germline and somatic driver mutations identified in clinically sporadic PNETs reported in two whole genome sequencing studies13,54. Germline mutations were identified in MEN1, CDKN1B, VHL, BRCA2 and MUTYH and CHEK213. One study reported whole exome sequencing findings from 10 sporadic PNETs and screened the most common mutated genes in an additional 58 PNETs which together comprised 66 non-functional tumors and 2 functional PNETs54. Another study reported the genomic findings from 98 clinically sporadic PNETs comprising 78 non-functional tumors, 8 insulinomas, 1 glucagonoma, 2 gastrinomas, 1 clear cell tumor, 1 PPoma, 1 VIPoma, 1 unspecified functional tumor and 5 well differentiated or well/poorly differentiated NECs13. This identified ~3100 somatic coding mutations ~2500 of which were non-silent in >2550 genes, and some of these mutations were verified in a further 62 additional PNETs13. Sixteen significantly and recurrently mutated genes defined by IntOGen analysis are shown. In addition recurrent mutations were identified in TSC1 and TSC213,54 which encode negative regulators of the mTOR pathway, and the histone modifier gene SETD2 was reported to have multiple independent mutations in subclones of a tumor. Recurrent regions of gain and loss, as well as chromosomal rearrangements were also identified13. 1Type S = somatic, G = germline. 2Mutation: fs = frame shift insertion or deletion; in = in frame insertion or deletion; ns = nonsense mutation; ms = missense mutation; sp = splice site mutation; re = chromosomal rearrangement; CNV = copy number variant; meth = hypermethylation of the promoter

| Gene | Pathway/Function | Type1 | Somatic (%) | Germline (%) | Mutation2 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEN1 | Chromatin remodelling/mTOR/TGF-β | S /G | 37-44 | 6 | fs, in, ns, ms, sp | 13,54 |

| DAXX | Chromatin remodelling/ALT | S | 22-25 | fs, in, ns, ms, sp | 13,54 | |

| ATRX | Chromatin remodelling/ALT | S | 11-17 | fs, in, ns, sp | 13,54 | |

| PTEN | mTOR pathway | S | 7-9 | fs, ns, ms, | 13,54 | |

| SETD2 | Chromatin remodelling | S | 6 | fs, ns, ms, sp, re | 13 | |

| MLL3 | Chromatin remodelling | S | 3 | ns, ms, re | 13 | |

| TP53 | Cell cycle arrest/apoptosis/DNA repair | S | 2 | ns, ms | 13,54 | |

| TSC1 | mTOR pathway | S | 2 | ms, sp | 13 | |

| TSC2 | mTOR pathway | S | 2 | fs, ms | 13,54 | |

| CDC42BPB | Cytoskeletal reorganisation and cell migration | S | 2 | ms | 13 | |

| KLF7 | Transcriptional activator | S | 2 | ns | 13 | |

| BCOR | Transcriptional co-repressor | S | 2 | ns | 13 | |

| PRRC2A | Inflammation | S | 2 | fs, ns | 13 | |

| URGCP | Cell cycle progression | S | 2 | ns | 13 | |

| ARID1A | Chromatin remodelling | S | 2 | ns | 13 | |

| DIS3L2 | mRNA degradation | S | 2 | ms | 13 | |

| DEPDC5 | mTOR pathway | S | 2 | fs | 13 | |

| CDKN2A | Cell cycle progression | S | 1 | CNV/re, meth | 13 | |

| EYA1 | Transcriptional co-activator/DNA repair | S | 1 | CNV | 13 | |

| FMBT1 | Chromatin remodelling | S | 1 | CNV | 13 | |

| RABGAP1L | GTPase | S | 2 | CNV | 13 | |

| PSPN | mTOR pathway | S | 1 | CNV | 13 | |

| ULK1 | mTOR pathway | S | 1 | CNV | 13 | |

| MTAP | Polyamine metabolism | S | 4 | re | 13 | |

| ARID2 | Chromatin remodelling | S | 5 | re | 13 | |

| SMARCA4 | Chromatin remodelling | S | 3 | re | 13 | |

| DST | Cell adhesion | S | 3 | ms | 13 | |

| ZNF292 | Transcriptional regulation | S | 2 | ns | 13 | |

| EWSR | mTOR pathway | S | 3 | re | 13 | |

| PIK3CA | mTOR pathway | S | 1 | ms | 54 | |

| VHL | Degradation of hypoxia inducible factors | S/G | 1 | 1 | ns | 13 |

| CDKN1B | Cell cycle progression | G | 1 | 13 | ||

| MUTYH | Base excision repair | G | 5 | 13 | ||

| BRCA2 | DNA damage repair | G | 1 | 13 | ||

| CHEK2 | DNA damage repair | G | 4 | 13 |

Mutations in Genes Involved in Chromatin Remodelling

Approximately 25-45% of sporadic PNETs have somatic mutations in MEN1 with loss of heterozygosity seen at the MEN1 locus in 30-70% of cases, including those without somatic MEN1 mutations13,54–56; and ~45% have inactivating somatic mutations of either the death-domain-associated protein (DAXX) or α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) genes that are associated with loss of protein expression, detected by immunohistochemical analysis of PNETs57–61. Mutations in both MEN1 and either ATRX or DAXX occur in 18-25% of PNETs, whereas ATRX and DAXX mutations do not occur concurrently in the same tumor13,54, and this is consistent with the functional roles of DAXX and ATRX encoded proteins being within the same pathway62. Indeed, the DAXX and ATRX proteins, which are involved in apoptosis and chromatin remodelling13,54,63, are critical for the maintenance of stable telomere length. Thus, both DAXX and ATRX proteins, which form a H3.3 histone chaperone complex, are required to enable incorporation of histone H3.3 at telomeres. ATRX is also required for suppressing the expression of the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA), which maintains telomeric structure by regulating telomerase activity and heterochromatin formation64–68. Thus, DAXX and ATRX are involved in controlling telomere length, and the loss of DAXX or ATRX function due to mutations leads to an increase in telomere length in tumors with DAXX/ATRX mutations13, and these tumors are referred to as having the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) phenotype (Figure 2)58,59. Reactivation of telomerase leads to resistance to senescence in tumor cells with ATRX mutations, and tumors lacking telomerase activity display telomerase independent ALT69,70. Patients that have PNETs with mutations in MEN1, DAXX/ATRX or a combination of both MEN1 and DAXX/ATRX are reported to have a better prognosis when compared to patients who had PNETs that lacked these mutations54. Somatic mutations of the set domain containing 2 (SETD2) gene, have also been detected in ~20% of sporadic PNETs (Table 1)13,71. Inactivating mutations of SETD2, which is involved in chromatin remodelling, have previously been linked with clear cell renal carcinoma72. MEN1, DAXX and ATRX are tightly related to chromatin remodelling, thereby suggesting that PNETs are tightly regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, which are important drivers of tumorigenesis. Other epigenetic alterations found in PNETs include hypermethylation of the promoter region of RASSF1 and cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)73–75. In addition, insulin like growth factor 2 (IGF2) has a unique hypermethylation signature in insulinomas, and this is of interest in relation to the reported epigenetic changes in insulin like growth factor and insulinoma76. Finally, the pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 3 (PHLDA3) genomic locus, which is a p53-regulated repressor of Akt, has been reported to have LOH and promoter methylation at a high frequency, thereby indicating that PHLDA3 is a likely tumor suppressor in PNETs77.

The occurrence of MEN1 and DAXX/ATRX mutations in sporadic non-MEN1 insulinomas is reported to be 3-8% and 3%, respectively78,79. However mutations and differential expression of epigenetic modifying genes and their targets are reported to occur more frequently78,79. Thus, the somatic Trp372Arg gain of function mutation of the Ying Yang 1 (YY1) transcription factor, which regulates mitochondrial function and insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling and is a target for mTORC180,81, has been reported to occur in 15-30% of sporadic insulinomas78,79. The Trp372Arg mutation increased transcriptional activity of YY1 that resulted in greater transcription of target genes isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD(+)) alpha (IDH3A) and uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2)78. Other recurrently mutated genes detected in insulinomas include H3 histone family 3A (H3F3A), lysine-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein) serine/threonine kinase (ATR), which are reported in 8%, 8% and 8% of insulinomas, respectively79.

Mutations Affecting the mTOR Signaling Pathway

Approximately 15% of sporadic PNETs harbor somatic mutations of genes in the mTOR cell signaling pathway, and these include mutations of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), TSC1 and TSC2, and DEP (Dishevelled, Egl-10 and Pleckstrin) domain containing protein 5 (DEPDC5)13,54 (Table 1, Figure 2). Mutations in PTEN, TSC2 and DEPDC5, which are mutually exclusive, are typically inactivating mutations and 75% of sporadic PNETs have decreased expression of PTEN and TSC282, whereas the PIK3CA mutation, which involves a hotspot for activation of the kinase domain, has been reported to be oncogenic62,83. Moreover, gastroenteropancreatic NETs with TSC2, KRAS and tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutations are reported more likely to be associated with disease progression and reduced survival in patients, and these possible aggressive alterations were observed in 6% of patients with PNETs <2cm and limited to the pancreas (defined as stage 1 disease by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Tumor Node Metastasis (ENET TNM) classification and combined ENET/American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC))84, thereby identifying a potential group of patients that may benefit from early surgery or systemic therapy85. Gene fusion events involving the ewings sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) gene, that can activate mTOR signaling, have also been putatively identified in PNETs13.

Copy Number Changes

Copy number changes, which may reflect chromosomal instability comprising loss and gain have been reported in PNETs, and these alterations may accumulate during tumor growth and progression with multiple chromosomal abnormalities being associated with a worse prognosis1,86. Recurrent regions of chromosomal loss involve the known NET tumor suppressors MEN1, CDKN2A, EYA (eyes absent homolog) transcriptional coactivator and phosphatase 1 (EYA1), Scm (sex comb on midleg) like with four Mbt (malignant brain tumor) domains 1 (SFMBT1), and RAB GTPase activating protein 1 like (RABGAP1L) which are located on chromosomes 11q13.1, 9q21.3, 8q13.3, 3p21.1 and 1q25.1, respectively13. Recurrently amplified regions include persephin (PSPN) on chromosome 19p13.3 and Unc-51 (C.elegans) like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) on chromosome 12q24.33, which are involved in RET signaling and mTOR-regulated autophagy, respectively13.

MiRNAs

MiRNAs miR-103 and miR-155 are up- and down-regulated in PNETs and pancreatic acinar cancers when compared to normal tissue respectively87. MiR-204 expression in insulinomas is reported to correlate with insulin expression, and mir-21, which represses PTEN, is reported to be associated with an increased proliferation index in insulinomas and their hepatic metastases87. The miRNA profiles of insulinomas and non-functioning PNETs are reported to be indistinguishable, although overexpression of miR-204 and miR-211, which are closely related, have been reported to be restricted to insulinomas73,86,88.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Carcinomas (PNECs)

G3 PNETs or PNECs have a distinct molecular signature from G1 and G2 PNETs, in having frequent mutations of the TP53 and retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) genes which are very rare in well-differentiated PNETs13,89. The prevalence of TP53 aberrations is also significantly greater in liver metastases than in primary PNETs85. There are also significant differences in the distribution of variants in the rearranged during transfection (RET), Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncoprotein (HRAS), MEN1, DAXX and ATRX genes, with MEN1 variants being more common in early stage disease and DAXX and ATRX being more frequent in advanced disease85.

Germline Mutations In Patients With Sporadic Pnets

Germline mutations of the MEN1, CDKN1B and VHL genes have been reported to occur in ~6%, ~1%, and ~1% of patients with sporadic PNETs, which also had LOH involving these genes in the tumors13 (Table 1). The identification of germline MEN1 mutations in patients with apparently sporadic PNETs is important, as it indicates that such patients and their children are at greater risk of developing MEN1 associated tumors. This has implications for the clinical management and surveillance of MEN1-associated tumors in the patients and for genetic screening and tumor surveillance in their children and also possibly their first degree relatives. In addition, germline alterations in DNA repair genes have also been reported to result in characteristic mutational signatures in tumour genomes. Thus, inactivating germline mutations of the base-excision repair gene Mut Y homolog (MUTYH), which occurred with somatic LOH in PNETs of ~5% of patients13 (Table 1), had a mutational signature of G:C>T:A transversions throughout the tumor genome. Germline biallelic inactivation of MUTYH has been also reported to cause autosomal recessive MUTYH-associated colorectal polyposis syndrome, which is also associated with somatic G:C>T:A transversions involving the APC gene, that is the driver of colorectal polyps13,90. This suggests that MUTYH deficiency likely plays a role in the development of PNETs and that poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, which are directed at defective DNA-damage repair mechanisms, may represent potential treatments that would require further assessments. In addition, ~1% and ~4% of patients with sporadic PNETs have been observed to have germline mutations of breast cancer 2 (BRCA2), and checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) that were associated with reduced kinase activity, respectively13 (Table 1).

Current Therapeutic Approaches For Pnets

Surgical resection with regional lymph node dissection offers the only potentially curative treatment for well-differentiated PNETs (G1 and G2)9. For advanced PNETs and metastatic disease medical therapies (e.g. biotherapies, which target tumor-specific receptors and intracellular pathways, and chemotherapies, which generally target cell division) and radiological treatments (e.g. peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), radiofrequency ablation, transarterial embolization, and selective internal radiation therapy) are available9. Medical chemotherapy is usually reserved for patients with PNET metastases, a high tumor burden, high proliferative index (e.g. Ki-67 index >5%), rapid tumor progression or symptoms not controlled by biotherapy9. Chemotherapy for such PNET disease usually comprises combined cytotoxic regimes (e.g. Streptozocin with fluorouracil or doxorubicin91; or temozolamide with capecitabene92) and tumor response rates of 70% have been reported92. Medical biotherapies for PNETs, which can be: hormonal and based on somatostatin (a peptide hormone that inhibits release of other hormones, cell proliferation and angiogenesis93); or targeted to tumor-specific molecular changes (e.g. in receptors and signaling pathways) that help tumors to grow and spread, include mTOR signaling inhibitors, receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitors, and antibodies targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or its receptor (VEGFR)9 (Figure 2). The recent advances in medical biotherapies will be briefly reviewed, prior to discussing emerging therapies.

Somatostatin Analogues

Somatostatin analogues (e.g. octreotide and lanreotide) have been used to control excessive hormone secretion and for their potential anti-proliferative effects in patients with low-grade (Ki-67 index <5%) PNETs that express somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), which are G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)94–97. There are 5 SSTRs (SSTR1-5) and each has specific functions with: SSTR2 and SSTR5 predominantly mediating inhibition of hormone secretion; SSTR1, SSTR2, SSTR4 and SSTR5 mediating cell cycle arrest and anti-proliferative actions; and SSTR3 mediating apoptosis98,99. Moreover, the aberrantly truncated variant of SSTR5 (sst5TMD4) is overexpressed in gastroeneteropancreatic NETs (GEPNETs) where it is associated with increased aggressiveness100. In addition, sst5TMD4 disrupts the normal function of SSTR2 and decreases the response of different tumor cells and tissues in response to somatostatin analogues101,102. These findings suggest that identification of sst5TMD4 may be a useful biomarker to predict responses to somatostatin analogues and the aggressiveness of PNETs86,100. PNETs may express all 5 subtypes, although ~80% of PNETs will predominantly express SSTR2, for which octreotide and lanreotide have high affinities (Figure 2)94, such that treatment with: lanreotide resulted in a ~50% reduction in the risk of disease progression and a prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) (median in lanreotide treated group not reached versus median in placebo treated group of 18 months, p<0.001) in non-MEN1 patients with treatment naive well-differentiated G1 and G2 non-functioning GEPNETs96,103,104; and octreotide, resulted in tumor response in 10%, stable disease in 80%, and progression of disease in 10% of MEN1 patients with duodeno-pancreatic NETs who were treated, over 12-15 months105. In addition PRRT using a somatostatin analogue (e.g. octreotide, octreotate, dototate, and dota-toc) labelled with a β-emitting nuclide in the form of either 177Lutetium or 90Yttrium has been reported to be effective for treating NETs. Thus, treatment with: 177Lutetium- or 90Yttrium-octreotide in patients with gastro-intestinal NETs and metastatic NETs106–111, has been reported to result in objective response rates of ~20-60%106,108–110, progression free survival (PFS) of 20-34 months108,110, and an overall survival of 53 months108; combining 177Lutetium and 90Yttrium nuclides has also been reported to increase survival in patients with PNETs111; and the combination of 177Lu-octreotate, capecitabine and temozolomide, in a phase1/2 study, has been reported to result in complete or partial response in >50% of the patients with advanced NETs (including PNETs)107.

mTOR Inhibitors

mTOR activation is associated with poor prognosis and there is a significant correlation between high proliferaton index (Ki-67) values and expression of mTOR, PIK3CA and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (p-4EBP1)86,112. Moreover, somatic mutations of genes associated with the mTOR pathway13,54 are found in ~15% of PNETs, and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus, which suppresses multiprotein complexes to inhibit downstream signaling (Figure 2), has been reported to increase PFS from ~6 to 11 months in patients with advanced NETs, including PNETs113–116. However, a companion diagnostic test that would help to identify patients who could benefit from treatment with mTOR inhibitors are not available2, although preclinical data have suggested that aberrations of PI3KCA and PTEN, and high pAKT levels, may predict sensitivity to rapamycin in NET cell lines and rapalogs in NET patients117. However, protein and/or mRNA analysis might be a better indicator of mTOR pathway activation than mutational status, as it would avoid errors due to epigenetic changes that affect protein expression86. Loss of AKT repression, may also occur in patients with PHLDA3 LOH or methylation, and thus such patients may also potentially respond well to everolimus77.

Rtk Inhibitors

PNETs are highly vascular and frequently express VEGFRs118,119, and RTK inhibitors (e.g. sunitinib, which targets VEGFRs and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) (Figure 2)) have been reported to increase PFS from ~5.5 to 11.4 months, in patients with PNETs120. Pazopanib, another RTK inhibitor, has also been reported, in a phase 2 trial, to result in response and disease control rates of ~20% and >75%, respectively of non-MEN1 patients with metastatic GEPNETs121. However, therapeutic resistance to RTK inhibitors may arise through induction of hypoxic stress and upregulation of transcription factors controlling expression of pro-angiogenic molecules, or reduced lysosomal stability leading to autophagy122,123, and companion diagnostic tests that would help to identify such resistance remain to be developed.

Emerging Therapies For Pnets

MEN1 mutations, which occur in ~40% of sporadic PNETs and almost all MEN1 PNETs, represent the major drivers for PNET development, and therapies based on an increased understanding of menin, together with that of receptors and signaling pathways in PNETs are helping to develop new therapies. Assessment of the efficacy of these therapies have been facilitated by cellular and in vivo models which include conventional and conditional Men1 knockout mouse models that develop MEN1-associated tumors, including PNETs124–133, and some of these pre-clinical advances will be discussed.

MEN1 Gene Replacement Therapy

Menin acts as a tumor suppressor, and as such its loss due to MEN1 mutations leads to tumor development and growth. Thus, MEN1 gene replacement therapy should be able to suppress tumor proliferation, and indeed Men1 gene replacement therapy into pituitary NETs that developed in conventional knockout mice lacking one allele of Men1 (Men1+/-), using a recombinant non-replicating adenoviral serotype 5 vector (rAd5), containing Men1 cDNA under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter (rAd5-MEN1), resulted in increased menin expression with decreased proliferation of the pituitary NETs. The Men1 gene therapy did not induce an immune T-cell response or increased apoptosis134. These findings, established proof of principle for the efficacy of Men1 gene replacement therapy. In addition use of a hybrid adeno-associated virus and phage (AAVP) vector displaying biologically active octreotide on the viral surface for ligand-directed delivery of the pro-apoptotic tumor necrosis factor (TNF) transgene to PNETs developing in a pancreatic specific Men1 knockout mouse model, has also been reported to reduce tumor size, and improve survival of the mutant mice135. These results suggest that systemic, ligand-directed transgene treatment of PNETs could potentially evolve as a novel and effective treatment.

Epigenetic Modulators

Menin interacts with a number of histone modifying proteins including histone methyltransferase (MLL1 and PRMT5) and deacetylase complexes (mSin3A-histone deacetylase)17 (Figure 1), and the use of epigenetic modulators, which represent a novel class of anti-cancer drugs136 to treat PNETs has been employed in in vitro and in vivo studies137. These studies utilised JQ1, an inhibitor of the bromo and extra terminal domain (BET) family of proteins that bind to acetylated histone residues to promote gene transcription137. In vitro studies revealed that JQ1 decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of a PNET cell line and in vivo studies, using a pancreatic β-cell specific conditional Men1 knockout mouse model revealed that JQ1 decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of PNETs137. CP103, another BET inhibitor, has also been reported to reduce PNET proliferation in a human PNET cell line xenograft mouse model138. Thus, epigenetic modulators, e.g. via BET inhibition, may offer potential therapies for PNETs lacking MEN1 expression.

Wnt Signaling Modulators

Menin inhibits Wnt signaling, as it promotes phosphorylation of β-catenin and its transfer from the nucleus via nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling, which reduces cell proliferation21,26. Moreover, the conditional knockout of β-catenin in PNETs of mice with pancreatic β-cell conditional knockout of menin, decreased the number and size of PNETs, as well as increasing survival, while use of a β-catenin antagonist (PKF115-584) decreased PNET cell proliferation in β-cell menin knockout mice139. Thus, Wnt-signaling modulators may provide a novel approach for treatment of MEN1-deficient PNETs.

Ras Signaling

Aberrent activation of Ras signaling can occur in NETs due to mutations in Ras or Ras regulatory proteins like NF1, or downstream effectors such as Raf/MEK/ERK. Aberrent activation of Ras depends on absolute dependency on protein kinase C delta (PKCδ)-mediated survival pathways140,141. This sensitizes cells to apoptosis induced by suppression of PKCδ activity which is not toxic to cells with normal Ras activity. The PNET cell line - BON-1, is sensitive to PKCδ inhibition induced by shRNA knockdown or diverse small molecule inhibitors such as Rottlerin142, and such molecules may prove to be useful for treating PNETs which have activated Ras signaling.

Anti-Angiogenic Compounds

Most anti-angiogenic compounds block the activity of the cytokine VEGF, which promotes the growth and survival of blood vessels. Treatment with bevacizumab, which is an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, in combination with chemotherapy, has been reported to delay the progression of moderately well-differentiated and advanced gastro-intestinal NETs, which included metastatic well-differentiated, PNETs143–146. However, inhibiting VEGF signaling has been reported to be accompanied by increased invasiveness and metastasis of cancers possibly due to the upregulation of proangiogenic factors which include fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and therefore targeting FGFs in addition to VEGF and PDGF may improve the efficacy of treatment147–149. Furthermore, the combination of sunitinib, or an anti-VEGF antibody, with inhibitors (e.g. PF-04217903 or PF-0241066 (crizotinib)) of hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR or c-Met), which promotes cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, prevented the increased tumor aggressivity without impairment to the activity of restricting tumor growth150. Thus, these studies suggest that the increase in invasion and metastasis that are promoted by selective inhibition of VEGF signaling, may be reduced by combining the treatment with a c-met inhibitor. In addition, inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) synthase may have a role, since the use of L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), a NO synthase inhibitor, in ex vivo treatment of PNETs from conventional Men1+/- knockout mice, caused impaired blood perfusion and increased constriction of the tumour supplying arterioles151.

Use Of Somatostatin Analogues For Pnet Chemoprevention

Somatostatin analogues may have a potential role in chemoprevention of MEN1-associated NETs as they have been shown to have antiproliferative, and antisecretory effects on NETs103,104,152,153. Thus, treatment with pasireotide, which is a multiple-receptor-targeted somatostatin analogue that acts via SSTR1,2,3 and SSTR594, decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of PNETs in conventional Men1+/- and pancreatic specific conditional Men1 knockout mutant mice, as well as increasing survival of the conventional Men1+/- mutant knockout mice154,155. In addition to these anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects, pasireotide was also found to inhibit the development of PNETs in the Men1+/- mutant mice154. These findings, which indicate that pasireotide-treatment resulted in fewer Men1+/- mice with PNETs who also had fewer PNETs per pancreas, when compared to control phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-treated Men1+/- mice, are consistent with a lower development of new NETs, in pasireotide treated Men1+/- mice154. These findings suggest that somatostatin analogues may have a chemopreventative role in the treatment of MEN1-associated PNETs in patients, and two studies in MEN1 patients have reported such anti-proliferative actions of somatostatin analogues. In one study octreotide was given to MEN1 patients to treat duodeno-pancreatic NETs, and retrospective analysis revealed that 10% of PNETs had tumour response, and that 80% had stable disease105; and in another study, octreotide was given prospectively to 8 MEN1 patients with GEPNETs, and found to be safe and decrease gastro-intestinal hormone secretion, and to be associated with stable PNET disease156.

Summary

MEN1 mutations are major drivers for development of familial and sporadic forms of PNETs. Additional genetic studies of PNETs have further improved our understanding of the molecular alterations and cellular pathways associated with these tumours and these include the roles of genes involved in: chromatin remodelling and epigenetic regulation; mTOR signaling; K-RAS signaling; β-catenin/Wnt signaling; and SSTR signaling. This has lead to the development of medical biotherapies, which can inhibit SSTR, mTOR or RTK signaling. In addition recent pre-clinical studies have also demonstrated the efficacy of: MEN1 gene replacement therapy; epigenetic modulators; Wnt pathway targeting β-catenin antagonists; and multi-somatostatin receptor targeted analogues in treating PNETs. Clinical evaluation of such emerging treatments may help to provide new therapies for improving outcomes and life expectancies in PNET patients.

Key Points.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNETs) can occur as sporadic neoplasms or as part of hereditary syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1).

MEN1, which is an autosomal dominant disorder, is due to loss-of-function mutations of the tumour suppressor MEN1 gene that encodes menin.

Approximately 40% of non-familial (i.e. sporadic) PNETs have MEN1 mutations, with subsequent loss of menin which acts as a tumour suppressor.

Menin is a scaffold protein with roles in transcriptional regulation, genome stability, DNA repair, protein degradation, cell motility and adhesion, microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis, cell division, cell cycle control, epigenetic regulation and Wnt signaling.

Emerging therapies targeting the functional roles of menin with Men1 gene replacement therapy, epigenetic modulators and antagonists of Wnt-signaling may prove useful for future treatment of PNETs.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) programme grants G9825289 and G1000467 (M.S., K.E.L. and R.V.T) and UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – Oxford Biomedical Research Centre programme. R.V.T. is a Wellcome Trust Investigator and NIHR senior investigator.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Mark Stevenson, Email: mark.stevenson@ocdem.ox.ac.uk, Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism (OCDEM), University of Oxford, Churchill Hospital, Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LJ, United Kingdom; Tel 0044 (0)1865 857350.

Kate E. Lines, Email: kate.lines@ocdem.ox.ac.uk, Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism (OCDEM), University of Oxford, Churchill Hospital, Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LJ, United Kingdom; Tel 0044 (0)1865 857340.

Rajesh V. Thakker, Email: rajesh.thakker@ndm.ox.ac.uk, Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism (OCDEM), University of Oxford, Churchill Hospital, Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LJ, United Kingdom; Tel 0044 (0)1865 857501.

References

- 1.Reid MD, Saka B, Balci S, Goldblum AS, Adsay NV. Molecular Genetics of Pancreatic Neoplasms and Their Morphologic Correlates An Update on Recent Advances and Potential Diagnostic Applications. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141(2):168–180. doi: 10.1309/AJCP0FKDP7ENVKEV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohmoto A, Rokutan H, Yachida S. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Basic Biology, Current Treatment Strategies and Prospects for the Future. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(1) doi: 10.3390/ijms18010143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosman FTCF, Hruban RH, Thiese ND. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd RVORY, Kloppel G, Rosa J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. 4th. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after Carcinoid”: Epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(10):1727–1733. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura W, Kuroda A, Morioka Y. Clinical pathology of endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Analysis of autopsy cases. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36(7):933–942. doi: 10.1007/BF01297144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Domenico A, Wiedmer T, Marinoni I, Perren A. Genetic and epigenetic drivers of neuroendocrine tumours (NET) Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(9):R315–R334. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost M, Lines KE, Thakker RV. Current and emerging therapies for PNETs in patients with or without MEN1. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2018.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. Jama Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–1342. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao JC, Eisner MP, Leary C, et al. Population-based study of islet cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3492–3500. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9566-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Francois R, Iyer R, Seshadri M, Zajac-Kaye M, Hochwald SN. Current understanding of the molecular biology of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(14):1005–1017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarpa A, Chang DK, Nones K, et al. Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature. 2017;543(7643):65. doi: 10.1038/nature21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1) J Clin Endocr Metab. 2012;97(9):2990–3011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yates CJ, Newey PJ, Thakker RV. Challenges and controversies in management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours in patients with MEN1. Lancet Diabetes Endo. 2015;3(11):895–905. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemos MC, Thakker RV. Multiple endocrine neoplaslia type 1 (MEN 1): Analysis of 1336 mutations reported in the first decade following identification of the gene. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/humu.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thakker RV. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and type 4 (MEN4) Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2014;386(1–2):2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goudet P, Murat A, Binquet C, et al. Risk Factors and Causes of Death in MEN1 Disease. A GTE (Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) Cohort Study Among 758 Patients. World J Surg. 2010;34(2):249–255. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito T, Igarashi H, Uehara H, Berna MJ, Jensen RT. Causes of Death and Prognostic Factors in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: A Prospective Study Comparison of 106 MEN1/Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome Patients With 1613 Literature MEN1 Patients With or Without Pancreatic Endocrine Tumors. Medicine. 2013;92(3):135–181. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182954af1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal SK. The future: genetics advances in MEN1 therapeutic approaches and management strategies. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(10):T119–T134. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao Y, Liu R, Jiang X, et al. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of menin regulates nuclear translocation of {beta}-catenin. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(20):5477–5487. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Gurung B, Wan B, et al. The same pocket in menin binds both MLL and JUND but has opposite effects on transcription. Nature. 2012;482(7386):542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matkar S, Thiel A, Hua X. Menin: a scaffold protein that controls gene expression and cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(8):394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal SK, Kennedy PA, Scacheri PC, et al. Menin molecular interactions: Insights into normal functions and tumorigenesis. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37(6):369–374. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balogh K, Racz K, Patocs A, Hunyady L. Menin and its interacting proteins: elucidation of menin function. Trends Endocrin Met. 2006;17(9):357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(5):387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, et al. Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription. Cell. 1999;96(1):143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80967-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agarwal SK, Novotny EA, Crabtree JS, et al. Transcription factor JunD, deprived of menin, switches from growth suppressor to growth promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):10770–10775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834524100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurung B, Feng Z, Iwamoto DV, et al. Menin epigenetically represses Hedgehog signaling in MEN1 tumor syndrome. Cancer Res. 2013;73(8):2650–2658. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes CM, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Milne TA, et al. Menin associates with a trithorax family histone methyltransferase complex and with the hoxc8 locus. Mol Cell. 2004;13(4):587–597. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milne TA, Hughes CM, Lloyd R, et al. Menin and MLL cooperatively regulate expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):749–754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408836102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296(5573):1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hendy GN, Kaji H, Sowa H, Lebrun JJ, Canaff L. Menin and TGF-beta superfamily member signaling via the Smad pathway in pituitary, parathyroid and osteoblast. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37(6):375–379. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canaff L, Vanbellinghen JF, Kaji H, Goltzman D, Hendy GN. Impaired transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) transcriptional activity and cell proliferation control of a menin in-frame deletion mutant associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(11):8584–8597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heppner C, Bilimoria KY, Agarwal SK, et al. The tumor suppressor protein menin interacts with NF-kappaB proteins and inhibits NF-kappaB-mediated transactivation. Oncogene. 2001;20(36):4917–4925. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Feng ZJ, Gao SB, et al. Interplay between menin and K-Ras in regulating lung adenocarcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(47):40003–40011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamberlain CE, Scheel DW, McGlynn K, et al. Menin determines K-RAS proliferative outputs in endocrine cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(9):4093–4101. doi: 10.1172/JCI69004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallo A, Cuozzo C, Esposito I, et al. Menin uncouples Elk-1, JunD and c-Jun phosphorylation from MAP kinase activation. Oncogene. 2002;21(42):6434–6445. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel YC. Somatostatin and its receptor family. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 1999;20(3):157–198. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Ozawa A, Zaman S, et al. The tumor suppressor protein menin inhibits AKT activation by regulating its cellular localization. Cancer Res. 2011;71(2):371–382. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth Control and Disease. Cell. 2012;149(2):274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maher ER, Iselius L, Yates JRW, et al. Vonhippel-Lindau Disease-a Genetic-Study. J Med Genet. 1991;28(7):443–447. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.7.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maher ER, Neumann HPH, Richard S. von Hippel-Lindau disease: A clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(6):617–623. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolle C, Glenn G, Zbar B, et al. Improved detection of germline mutations in the von Hippel Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Hum Mutat. 1998;12(6):417–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:6<417::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Findeis-Hosey JJ, McMahon KQ, Findeis SK. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease. J Pediatr Genet. 2016;5(2):116–123. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1579757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blansfield JA, Choyke L, Morita SY, et al. Clinical, genetic and radiographic analysis of 108 patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) manifested by pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNETs) Surgery. 2007;142(6):814–818.:e811-812. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nordstrom-O’Brien MvdLRB, van Rooijen E, van der Ouweland Am, Majoor-Krakauer DF, Lolkema MP, van Brussel A, Voest EE, Giles RH. Genetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(5):521–537. doi: 10.1002/humu.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen HCJ, Adem A, Ylaya K, et al. Deciphering von Hippel-Lindau (VHL/Vhl)-Associated Pancreatic Manifestations by Inactivating Vhl in Specific Pancreatic Cell Populations. Plos One. 2009;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin GA, Viskochil D, Bollag G, et al. The Gap-Related Domain of the Neurofibromatosis Type-1 Gene-Product Interacts with Ras P21. Cell. 1990;63(4):843–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90150-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brems H, Beert E, de Ravel T, Legius E. Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of malignant tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):508–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishi T, Kawabata Y, Hari Y, et al. A case of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor in a patient with neurofibromatosis-1. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10 doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minnetti M, Grossman A. Somatic and germline mutations in NETs: Implications for their diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Cl En. 2016;30(1):115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lebwohl D, Anak O, Sahmoud T, et al. Development of everolimus, a novel oral mTOR inhibitor, across a spectrum of diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1291:14–32. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331(6021):1199–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corbo V, Dalai I, Scardoni M, et al. MEN1 in pancreatic endocrine tumors: analysis of gene and protein status in 169 sporadic neoplasms reveals alterations in the vast majority of cases. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(3):771–783. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gortz B, Roth J, Krahenmann A, et al. Mutations and allelic deletions of the MEN1 gene are associated with a subset of sporadic endocrine pancreatic and neuroendocrine tumors and not restricted to foregut neoplasms. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(2):429–436. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Wilde RF, Heaphy CM, Maitra A, et al. Loss of ATRX or DAXX expression and concomitant acquisition of the alternative lengthening of telomeres phenotype are late events in a small subset of MEN-1 syndrome pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(7):1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao YC, et al. Altered Telomeres in Tumors with ATRX and DAXX Mutations. Science. 2011;333(6041):425–425. doi: 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marinoni I, Kurrer AS, Vassella E, et al. Loss of DAXX and ATRX Are Associated With Chromosome Instability and Reduced Survival of Patients With Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):453. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.KA Chen SF, Yazdani S, Chan MSM, Wang L, Yang-Yang H, Gao HW, Sasano H. Clinicopathologic significance of immunostaining of alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked protein and death domain-associated protein in neuroendocrine tumors. Human Pathology. 2013;44:2199–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.SM Yuan F, Shi H, Zhou C, Yu Y, Liu B, Zhu Z, Zhang J. KRAS and DAXX/ATRX gene mutations are correlated with the clinicopathological features, advanced disease and poor prognosis in Chinese patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2014;10(9):957–965. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Wilde RF, Edil BH, Hruban RH, Maitra A. Well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: from genetics to therapy. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat. 2012;9(4):199–208. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elsasser SJ, Allis CD, Lewis PW. New Epigenetic Drivers of Cancers. Science. 2011;331(6021):1145–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1203280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Gene Dev. 2010;24(12):1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, et al. Distinct Factors Control Histone Variant H3.3 Localization at Specific Genomic Regions. Cell. 2010;140(5):678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong LH, McGhie JD, Sim M, et al. ATRX interacts with H3.3 in maintaining telomere structural integrity in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2010;20(3):351–360. doi: 10.1101/gr.101477.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cusanelli E, Chartrand P. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA TERRA: a noncoding RNA connecting telomere biology to genome integrity. Front Genet. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science. 2007;318(5851):798–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vinagre J, Pinto V, Celestino R, et al. Telomerase promoter mutations in cancer: an emerging molecular biomarker? Virchows Arch. 2014;465(2):119–133. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1608-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lovejoy CA, Li WD, Reisenweber S, et al. Loss of ATRX, Genome Instability, and an Altered DNA Damage Response Are Hallmarks of the Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres Pathway. Plos Genet. 2012;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raj NP, Soumerai T, Valentino E, Hechtman JF, Berger MF, Reidy DL. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) in advanced well differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (WD pNETs): A study using MSK-IMPACT. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463(7279):360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meeker A, Heaphy C. Gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;386(1–2):101–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karpathakis A, Dibra H, Thirlwell C. Neuroendocrine tumours: cracking the epigenetic code. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(3):R65–R82. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.House MG, Herman JG, Guo MZ, et al. Aberrant hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Ann Surg. 2003;238(3):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086659.49569.9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Cell. 2011;144(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohki R, Saito K, Chen Y, et al. PHLDA3 is a novel tumor suppressor of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(23):E2404–e2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319962111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cao YN, Gao ZB, Li L, et al. Whole exome sequencing of insulinoma reveals recurrent T372R mutations in YY1. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang H, Bender A, Wang P, et al. Insights into beta cell regeneration for diabetes via integration of molecular landscapes in human insulinomas. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00992-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blattler SM, Cunningham JT, Verdeguer F, et al. Yin Yang 1 Deficiency in Skeletal Muscle Protects against Rapamycin-Induced Diabetic-like Symptoms through Activation of Insulin/IGF Signaling. Cell Metab. 2012;15(4):505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1 alpha transcriptional complex. Nature. 2007;450(7170):736–U712. doi: 10.1038/nature06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, et al. Pancreatic Endocrine Tumors: Expression Profiling Evidences a Role for AKT-mTOR Pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):245–255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samuels Y, Wang ZH, Bardelli A, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304(5670):554–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rindi G, Falconi M, Klersy C, et al. TNM Staging of Neoplasms of the Endocrine Pancreas: Results From a Large International Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer I. 2012;104(10):764–777. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gleeson FC, Voss JS, Kipp BR, et al. Assessment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cytologic genotype diversity to guide personalized medicine using a custom gastroenteropancreatic next-generation sequencing panel. Oncotarget. 2017;8(55):93464–93475. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Capdevila J, Casanovas O, Salazar R, et al. Translational research in neuroendocrine tumors: pitfalls and opportunities. Oncogene. 2017;36(14):1899–1907. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roldo C, Missiaglia E, Hagan JP, et al. MicroRNA expression abnormalities in pancreatic endocrine and acinar tumors are associated with distinctive pathologic features and clinical behavior. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(29):4677–4684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oberg K, Casanovas O, Castano JP, et al. Molecular Pathogenesis of Neuroendocrine Tumors: Implications for Current and Future Therapeutic Approaches. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(11):2842–2849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yachida S, Vakiani E, White CM, et al. Small Cell and Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Pancreas are Genetically Similar and Distinct From Well-differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(2):173–184. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182417d36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Al-Tassan N, Chmiel NH, Maynard J, et al. Inherited variants of MYH associated with somatic G:C-->T:A mutations in colorectal tumors. Nat Genet. 2002;30(2):227–232. doi: 10.1038/ng828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill JS, McPhee JT, McDade TP, et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2009;115(4):741–751. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, et al. First-Line Chemotherapy With Capecitabine and Temozolomide in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Endocrine Carcinomas. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2011;117(2):268–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cakir M, Dworakowska D, Grossman A. Somatostatin receptor biology in neuroendocrine and pituitary tumours: part 1--molecular pathways. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(11):2570–2584. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schmid HA, Silva AP. Short-and long-term effects of octreotide and SOM230 on GH, IGF-I, ACTH, corticosterone and ghrelin in rats. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28(11 Suppl International):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walter T, Brixi-Benmansour H, Lombard-Bohas C, Cadiot G. New treatment strategies in advanced neuroendocrine tumours. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2012;44(2):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martin-Richard M, Massuti B, Pineda E, et al. Antiproliferative effects of lanreotide autogel in patients with progressive, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours: a Spanish, multicentre, open-label, single arm phase II study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Palazzo M, Lombard-Bohas C, Cadiot G, et al. Ki67 proliferation index, hepatic tumor load, and pretreatment tumor growth predict the antitumoral efficacy of lanreotide in patients with malignant digestive neuroendocrine tumors. European journal of gastroenterology hepatology. 2013;25(2):232–238. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328359d1a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Theodoropoulou M, Stalla GK. Somatostatin receptors: From signaling to clinical practice. Front Neuroendocrin. 2013;34(3):228–252. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Shimon I, Korbonits M, Grossman AB. Somatostatin analogues in the control of neuroendocrine tumours: efficacy and mechanisms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(3):701–720. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sampedro-Nunez M, Luque RM, Ramos-Levi AM, et al. Presence of sst5TMD4, a truncated splice variant of the somatostatin receptor subtype 5, is associated to features of increased aggressiveness in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncotarget. 2016;7(6):6593–6608. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Duran-Prado M, Saveanu A, Luque RM, et al. A Potential Inhibitory Role for the New Truncated Variant of Somatostatin Receptor 5, sst5TMD4, in Pituitary Adenomas Poorly Responsive to Somatostatin Analogs. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2010;95(5):2497–2502. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Duran-Prado M, Gahete MD, Hergueta-Redondo M, et al. The new truncated somatostatin receptor variant sst5TMD4 is associated to poor prognosis in breast cancer and increases malignancy in MCF-7 cells. Oncogene. 2012;31(16):2049–2061. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Cwikla JB, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):224–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Cwikla JB, et al. Anti-tumour effects of lanreotide for pancreatic and intestinal neuroendocrine tumours: the CLARINET open-label extension study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(3):191–199. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ramundo V, Del Prete M, Marotta V, et al. Impact of long-acting octreotide in patients with early-stage MEN1-related duodeno-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80(6):850–855. doi: 10.1111/cen.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bodei L, Cremonesi M, Grana CM, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with (1)(7)(7)Lu-DOTATATE: the IEO phase I-II study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(12):2125–2135. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1902-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Claringbold PG, Price RA, Turner JH. Phase I-II study of radiopeptide 177Lu-octreotate in combination with capecitabine and temozolomide in advanced low-grade neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2012;27(9):561–569. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ezziddin S, Khalaf F, Vanezi M, et al. Outcome of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-octreotate in advanced grade 1/2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(5):925–933. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Imhof A, Brunner P, Marincek N, et al. Response, survival, and long-term toxicity after therapy with the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in metastasized neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2416–2423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sansovini M, Severi S, Ambrosetti A, et al. Treatment with the radiolabelled somatostatin analog Lu-DOTATATE for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97(4):347–354. doi: 10.1159/000348394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Villard L, Romer A, Marincek N, et al. Cohort study of somatostatin-based radiopeptide therapy with [(90)Y-DOTA]-TOC versus [(90)Y-DOTA]-TOC plus [(177)Lu-DOTA]-TOC in neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1100–1106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Qian ZR, Ter-Minassian M, Chan JA, et al. Prognostic Significance of MTOR Pathway Component Expression in Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lombard-Bohas C, Yao JC, Hobday T, et al. Impact of prior chemotherapy use on the efficacy of everolimus in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a subgroup analysis of the phase III RADIANT-3 trial. Pancreas. 2015;44(2):181–189. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yao JC, Pavel M, Lombard-Bohas C, et al. Everolimus for the Treatment of Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Overall Survival and Circulating Biomarkers From the Randomized, Phase III RADIANT-3 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Oh DY, Kim TW, Park YS, et al. Phase 2 study of everolimus monotherapy in patients with nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors or pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6162–6170. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meric-Bernstam F, Akcakanat A, Chen HQ, et al. PIK3CA/PTEN Mutations and Akt Activation As Markers of Sensitivity to Allosteric mTOR Inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(6):1777–1789. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hanahan D, Christofori G, Naik P, Arbeit J. Transgenic mouse models of tumour angiogenesis: the angiogenic switch, its molecular controls, and prospects for preclinical therapeutic models. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(14):2386–2393. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Scoazec JY. Angiogenesis in neuroendocrine tumors: therapeutic applications. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97(1):45–56. doi: 10.1159/000338371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):501–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ahn HK, Choi JY, Kim KM, et al. Phase II study of pazopanib monotherapy in metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1414–1419. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yao JC, Phan A. Overcoming Antiangiogenic Resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(16):5217–5219. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]