Abstract

The Cell-Assembled extracellular Matrix (CAM) is an attractive biomaterial because it provided the back-bone of vascular grafts that were successfully implanted in patients, and because it can now be assembled in “human textiles”. For future clinical development, it is important to consider key manufacturing questions. In this study, the impact of various storage conditions and sterilization methods were evaluated. After 1 year of dry frozen storage, no change in mechanical nor physicochemical properties were detected. However, storage at 4 °C and room temperature resulted in some mechanical changes, especially for dry CAM, but physicochemical changes were minor. Sterilization modified CAM mechanical and physicochemical properties marginally except for hydrated gamma treatment. All sterilized CAM supported cell proliferation. CAM ribbons were implanted subcutaneously in immunodeficient rats to assess the impact of sterilization on the innate immune response. Sterilization accelerated strength loss but no significant difference could be shown at 10 months. Very mild and transient inflammatory responses were observed. Supercritical CO2 sterilization had the least effect. In conclusion, the CAM is a promising biomaterial since it is unaffected by long-term storage in conditions available in hospitals (hydrated at 4 °C), and can be sterilized terminally (scCO2) without compromising in vitro nor in vivo performance.

Keywords: Cell-assembled extracellular matrix, Sterilization, Storage stability, In vivo remodeling, Mechanical properties, Physicochemical properties

1. Introduction

Tissue-Engineered Products (TEPs) offer groundbreaking opportunities in healthcare and are the subject of thousands of research studies around the world. However, only a handful of them have led to clinical trials and they have yet to achieve widespread clinical use. To date, only 102 clinical trials in tissue engineering have been conducted [1], and fewer than 20 TEPs have been approved or marketed [2]. This low rate of clinical translation can be explained by the important manufacturing and regulatory challenges [3] associated with TEP development. Some of these difficulties can bring a breakthrough technology to a standstill when they have not been addressed sufficiently early in the development process.

Our team has shown that the Cell-Assembled extracellular Matrix (CAM), produced by normal adult skin fibroblasts in vitro, is truly a “bio”-material with a strong therapeutic potential [4]. We have recently focused on the development of CAM-based human textiles as an innovative technology to produce TEPs [5]. In this study, we address two issues that are crucial for the development of any CAM-based TEP: product stability and sterilization.

Off-the-shelf availability is a key feature to facilitate clinical adoption and allow the use of the product in emergency cases. A critical limitation for the clinical relevance of TEP is often storage temperature. For example, while -80 °C storage is readily available in academic research, this type of storage is challenging in a clinical context as the world recently experienced with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [6].

Sterility is an absolute requirement for TEP. Aseptic manufacturing is an option, and successful products have reached clinical trials and even commercialization (Dermagraft®, Apligraft®) using this strategy [7–9]. Although this process may be optimal, it comes at a significant cost in terms of time, complexity, infrastructure, risks, and quality control. Terminal sterilization is an alternative strategy that provides high safety levels, that are preferred by regulatory agencies, and simplifies manufacturing [10]. However, sterilization methods are known for altering biomaterials, particularly when they are of biological origin, resulting in changes in mechanical and chemical properties that can impair in vivo performance [11]. To date, no consensus exists on an appropriate sterilization protocol and sterilization effects must be evaluated on every new biomaterial [12].

The first objective of this study is to characterize the effects of storage conditions on the mechanical and physicochemical properties of the CAM in vitro after 1 year of storage. The second objective is to evaluate the effects of 6 sterilization methods on the mechanical, physicochemical and biological properties of the CAM in vitro and in vivo. This work will allow the selection of the most appropriate methods to manufacture terminally sterilized CAM-based TEPs that can be available off-the-shelf.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Cell culture and CAM samples production

Human Skin Fibroblast (HSFs) isolation and culture were performed in accordance with article L. 1243-3 of the code of public health and under the agreement DC-2008-412 with the University Hospital Center of Bordeaux, France [update 10/10/2014] as previously described [13,14]. Briefly, HSFs were isolated from adult normal human skin and grown in DMEM/F12 media (#31331-028, Gibco) supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (20%; #SH30109 HyClone; #S1810-500 Biowest or #CVFSVF00-01 Eurobio; 1:1). For CAM sheets production, HSFs (passage 5 or 6) were seeded (1 × 104 cells/cm2) in 6-well plates or in 225 cm2 flasks to obtain circular (3.5 cm diameter) or rectangular (10 × 18 cm) sheets. They were cultured for 8 weeks with a supplementation of sodium L-ascorbate (500 μM, #A4034-500 G, Sigma-Aldrich). CAM sheets were rinsed (distilled water), frozen at -80 °C, thawed and then rinsed (distilled water). Large sheets of 108 microns in thickness (± 31 μm, n = 24) were either cut into ribbons (5-mm-wide, with a custom-made automated device), into squares (approximatively 2 × 2 cm, with scissors) or into disks (6-mm-diameter, with biopsy punches) and then air-dried (sterile air flow, at least 2 h). We refer to these steps of freezing / thawing / drying by using the term “devitalization”. All samples were stored at 80 °C until needed.

2.2. Storage stability of CAM samples

CAM samples were stored under various storage methods: dry at -80 °C, -20 °C, 4 °C or room temperature (RT); or hydrated (in PBS) at 4 °C or RT. After 1 year, samples were rehydrated when appropriate at least 1 h, which is a sufficient time for CAM samples to regain their original mechanical properties after devitalization (Suppl. Fig. 1). Mechanical testing and physicochemical evaluation were performed as described in the following sections. Devitalized CAM was used as control. Three independent experiments were performed.

2.3. Sterilization of CAM samples

CAM samples were sterilized by irradiation (min. 25 kGy), or by gas (validation by bacteriological indicator – bacillus atrophaeus strain). Tested treatments (Table 1) were: (1) high dose rate gamma irradiation on dry sample (γ Hdr D, standard commercial treatment: mean 2 kGy/h – min. 0.5 kGy/h – max. 20 kGy/h, IONISOS, Dagneux, France), (2) low dose rate gamma irradiation on dry sample (γ Ldr D, 0.5 kGy/h, IONISOS, Dagneux, France), (3) low dose rate gamma irradiation on hydrated sample (γ Ldr H, 0.5 kGy/h, in distilled water, IONISOS, Dagneux France), (4) electron beam irradiation (eBeam, 300 kGy/min, IONISOS, Chaumesnil France), (5) ethylene oxide (EtO, thoroughly rinsed with distilled water before sterilization, exposure time: 17h, aeration time: 50h, IONISOS, Civrieux d’Azergues France), or (6) supercritical CO2 (scCO2, with peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide buffer, Rescoll, Pessac, France). Samples from conditions 4 to 6 were sterilized dry. After sterilization, samples were stored at 4 °C until use. Samples were rehydrated with distilled water when appropriate at least 1 h before performing mechanical testing, physicochemical evaluation, cytocompatibility testing, histological analysis and implantation as described in the following sections. CAM produced under aseptic conditions was used as control.

3. Mechanical testing

3.1. Samples cross-section evaluation and uniaxial tensile test

Cross-section of CAM ribbons was evaluated as previously described with biaxial laser micrometer [15]. Then, ribbons extremities were clamped between the flat jaws of a tensile test apparatus (100N load cell, AGSX, Shimadzu), pre-loaded (to 0.05 N, 20 mm/min), and stretch (to breaking point, at a speed of 1% of sec of the initial length (L0) of the sample after preloading. Load and extension were recorded using Trapezium X software. Storage stability: n=8/condition/experiment, sterilization: n=2-8/conditions/time – samples could not be tested after explantation.

3.2. Tensile test data processing

A MATLAB code was written to determine the Young’s modulus by computing the slope in the quasi-linear region of the J-shaped stress-strain curve (Fig. 1A) which corresponds to the end of the curve [16,17]. To determine the quasi-linear region of the curve, the code proceeds in 2 steps. In a first phase, the largest interval (starting from the end, including at least 30% of the total values) whose linear regression line (y=Ax+B) has an r2 superior or equal to 0.999 is selected, and A corresponds to Young’s modulus. If no interval meets the criteria, a second phase starts where the code seeks the largest interval (≥ 30% of the total values) whose linear regression line (y=Cx+D) has the highest r2, but which does not necessarily begin from the end of the curve. C value then corresponds to the Young’s modulus. This data processing eliminated experimental artifacts such as oscillation in the curve due to a sample slight slippage in the jaws.

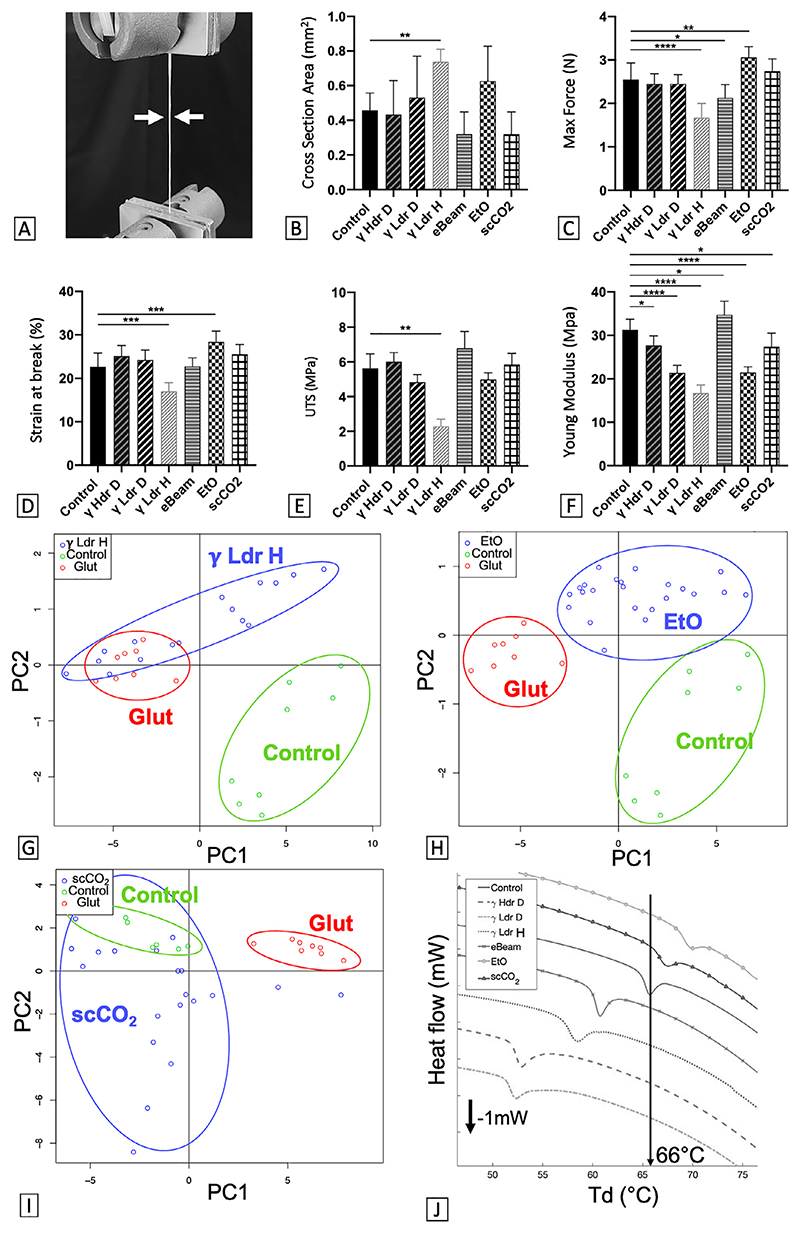

Fig. 1. CAM can be conserved for at least 1 year with no (or minor) modification of mechanical and physicochemical properties.

(A) Stress-strain curve obtained after tensile testing of a control CAM ribbon. (B) Cross-section of devitalized CAM ribbons before (control) and after 1 year of storage in various conditions (RT: Room Temperature, HYDR = Hydrated). Tensile test results: (C) Maximum Force, (D) Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS), (E) Strain at break and (F) Young modulus of CAM ribbons before and after 1 year storage. Results are expressed as mean of 3 experiments using 3 CAM batches (± SD, n = 5 to 8 ribbons) as % of control. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 as compared to control. One-way ANOVA for Cross Section, Max Force, Strain at break and Kruskal-Wallis for Max Stress, Young Modulus. (G) PCA scatter plot of CAM FTIR spectra (4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1) does not show a significant difference between control and CAM stored 1 year dry at RT (RT D). Glutaraldehyde-crosslinked CAM (Glut – positive denatured control) is easily distinguished from control. Ellipses cluster the different groups. (H) CAM denaturation temperature (Td) before and after 1 year of storage in various conditions (n = 4-11, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, One-way ANOVA).

4. Physicochemical evaluation

4.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Hydrated CAM samples (> 25 mg) were sealed in aluminum crucibles of 100 μL, in volume, and heated from 10 to 200 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C/min. DSC analyses were performed on a Mettler Toledo analyzer (DSC 1 STARe System). All data were processed using STARe software and MATLAB to obtain denaturation temperatures (Td, lowest point of the endothermic peak) of samples. Paraformaldehyde (4%, overnight) cross-linked CAM samples were tested as a positive control of denatured CAM. Storage stability: n = 4-11/condition/experiment, sterilization: n = 11-12/conditions/time.

4.2. Fourier Transform InfraRed (FTIR)

Hydrated CAM samples were air-dried for at least 2 h when appropriate (after rinses in distilled water if in PBS). CAM spectra were acquired using an ATR FT-IR spectrometer (FT-IR 4600, Jasco Inc., Tokyo, Japan) controlled by spectra manager software. CAM spectra were recorded after averaging 8 accumulations with 8 cm−1 resolution between 4000 cm−1 and 400 cm−1. Background was performed on the atmosphere and subtracted to all acquisitions. All spectra were acquired in the transmittance mode. IR data were processed using a free online tool, ChemFlow 20.05, mostly dedicated to infrared spectrometry. Before the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the spectra were pre-processed using Savitzky Golay derivative (derivative order: 1; Size of window: 7; Degree of the polynom: 2). Glutaraldehyde (25%, 4 days, 354400, Sigma Aldrich) cross-linked CAM samples were tested as a positive control of denatured CAM. Storage stability: n = 2–20 spectra/condition/experiment, sterilization: n = 8–24 spectra/conditions/time.

4.3. Cytocompatibility testing

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) were isolated from healthy newborns’ umbilical veins as previously described [15]. HUVECs were then transduced with mKate-containing vector using the same technique as previously described [18]. MKate-labelled HUVECs were grown in Endothelial Cell Growth Basal Medium-2 (EBM-2, CC-3156, Lonza) supplemented with the Microvascular Endothelial SingleQuotsTM Kit (EGMTM-2, CC-4147, Lonza) without antibiotics. CAM sheets were rehydrated (supplemented medium, 24 h, 37 °C) and their upper surfaces were seeded with HUVECs (passage 9, 0.5.104 cells/cm2). Cell attachment and endothelium development was evaluated. When cells reached confluence, CAM sheets were fixed (4% PFA, 1 h, RT). HUVECs were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against VE-Cadherin (2 h, RT, 1:1000, ab231227, Abcam) then with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1 h, RT, 1:300, A-11008, Invitrogen) followed by 1h incubation in 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:1000, D1306, Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (TCS SPE, Leica Microsystems).

4.4. Subcutaneous implantation and explantation in immunodeficient rats of CAM ribbons

Fifty-four immunodeficient female rats (12–14 rats/time) were subcutaneously implanted as previously described [14]. Sterilized CAM ribbons with γ Hdr D, γ Ldr D, γ Ldr W, eBeam, EtO or scCO2 and control were inserted under rat skin using a sterile 17-cm-long needle. Each rat received 4 ribbons from 2 different methods, and 8 ribbons per condition per time were distributed evenly among the rats. Samples were explanted at 2 weeks, 1, 5 and 10 months (no access to the animal facility during Covid-19 postpone the last 2 explantation times initially scheduled at 3 and 6 months, and no eBeam ribbons were implanted at 2 weeks due to animal availability issues). After sacrifice, rats were carefully skinned and ribbons retrieved. Some ribbons were missing, probably eaten by rats as already observed before. Remaining ribbons were classified into 3 categories: (1) easy to extract, (2) difficult to extract, and (3) distinctly apparent but non-extractable from skin. One end of each ribbon was explanted with surrounding tissue for histological analysis while the rest was carefully dissected for mechanical testing. All procedures and animal treatments complied with the principles of laboratory animal care formulated by the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

5. Histological analysis

5.1. Sample preparation and standard staining

Pieces of non-implanted ribbons were assembled into bundles (t0, n = 8/condition), and implanted ribbons were explanted as explained in Section 2.7. Samples were fixed (4% PFA, at least overnight) and paraffin-embedded. Blocks were cut into 5-μm-thick cross-sections and representative sections were stained with standard Hematoxylin-Erythrosine (H&E) or Masson’s Trichrome (MT) staining. Images were captured using a slide scanner (NanoZoomer S60 digital slide scanner, C13210-01, Hamamatsu).

5.2. Immunofluorescence

Representative sections were selected for immunofluorescence (n = 1/condition/time). To identify macrophages with an “M1” phenotype, sections were double-stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CCR7 (1:100, ab32527, Abcam) and mouse polyclonal antibodies against CD68 (1/100, ab31630, Abdcam) (2h, RT). “M2” macrophages were double-stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CD206 (1:100, ab64693, Abcam) and mouse polyclonal antibodies against CD68 (1/100, ab31630, Abdcam) (2h, RT). Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antirabbit (1:150, A-11008, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:150, A-11031, Invitrogen), and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:500, D1306, Invitrogen) were applied (1h, RT). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (TCS SPE, Leica microsystems).

5.3. Statistical analysis

One-variable data sets were analyzed by one-way ANOVA when residuals were normal (D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus (K2) test) and by a Kruskal-Wallis test otherwise. Two-variable data sets were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA. Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests followed ANOVA tests, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test followed others. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

6. Results

6.1. The effect of various long-term storage on the CAM stability

To evaluate the effect of storage on CAM mechanical properties, tensile tests were performed after 1 year of storage under different storage conditions. Fig. 1A shows the J-shaped (or hyperbolic) stress-strain curve of devitalized CAM used as control. This shape, typical of soft tissue, shows 2 phases of sample response to loading. First, the collagen fibrils composing the matrix align. Then, the collagen fibrils expand under tension [19,20,17]. Mechanical parameters obtained from tensile testing ribbons were compared after long-term storage (Fig. 1B-F). One year of frozen storage did not change any of the measured mechanical properties. However, dry unfrozen storage (4 °C and RT) did modify CAM mechanical properties. It decreased the cross-sectional area of rehydrated ribbons by over 50% compared to control after 1-year storage (Fig. 1B). It also increased their strength by 28% compared to control for RT (Fig. 1C) but did not significantly modify their stretchability (Fig. 1D). UTS logically showed an increasing trend for both groups (more pronounced for RTd) but statistical significance was not achieved (Fig. 1E). In addition, it appeared that RT storage (compared to 4 °C) tended to increase the effects of dry storage on the CAM (Fig. 1C-F). Stiffness was also increased as expected (4 °C: + 171 % of control, RT: + 229% of control – Fig. 1F). Importantly, hydrated non-frozen storage only resulted in small changes in CAM mechanical properties. Cross-sectional areas of 1-year samples slightly decreased after storage (-4 °C: -23% of control, RT: -27% of control –Fig. 1B) as did as stretchability (< -15% - Fig. 1D) whereas strength was unmodified (Fig. 1C).

To also evaluate the effect of 1 year of storage on CAM physicochemical properties, DSC and FTIR spectroscopy were performed. Analysis of the DSC thermograms provided the denaturation temperature (Td) of samples, which is an indicator of the thermal stability of collagen 3D structure [21–23]. The slight increase in Td of the CAM stored at RT dry, 4 °C hydrated and RT hydrated (+ 2% of control) indicates that the thermal stability of the CAM was slightly modified under these conditions (Fig. 1G). For comparison, the Td of the CAM cross-linked with PFA (4%) increased by 33%. FTIR spectroscopy was used to obtain CAM spectra before and after storage and thereby to evaluate general CAM changes at the molecular level [22, 23]. Principle Component Analysis of FTIR spectra did not allow clear distinctions between 1-year-conserved points clouds and control one, thus not showing any significant change in the samples molecular structure (Fig. 1H). For comparison, the cloud points of CAM fixed with glutaraldehyde (Glut) used as a positive control of matrix denaturation is clearly distinguished from control. These in vitro results indicate that the CAM is mechanically and physicochemically stable to frozen storage and can withstand hydrated cold storage with only minor mechanical and physicochemical modifications.

6.2. The effect of various terminal sterilization on the CAM properties

To evaluate the effect of sterilization on the CAM, mechanical properties were quantified by uniaxial testing of 5-mm-wide sterilized ribbons (Fig. 2A-F), physiochemical properties were assessed by FTIR spectroscopy and DSC on sterilized CAM sheets (Fig. 2G-J), matrix morphology was evaluated by histology (Fig. 3A-C) and cytocompatibility was tested by endothelialization of sterilized CAM sheets (Fig. 3D-F). All results were compared to a control CAM produced aseptically.

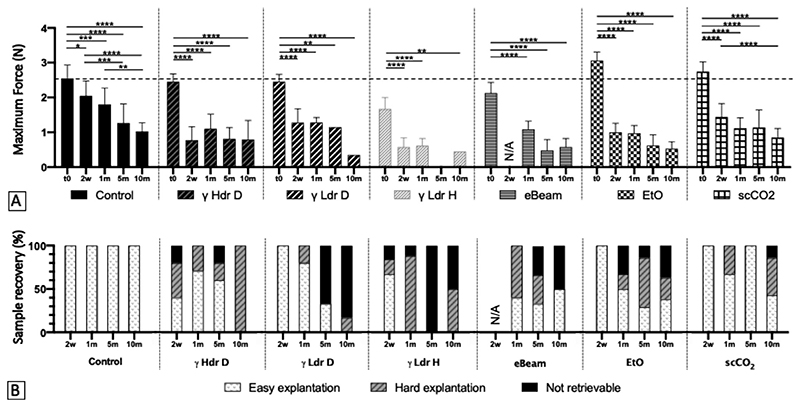

Fig. 2. CAM can be terminally sterilized with minor modification of its mechanical and physicochemical properties.

(A) Five-mm-wide CAM ribbon (white arrows) undergoing a tensile test. (B) Cross-section of devitalized CAM ribbons before (control) and after terminal sterilization with various methods. Tensile test results: (C) Maximum Force, (D) UTS, (E) Strain at break and (F) Young modulus of CAM ribbons before and after terminal sterilization. n = 7-8 ribbons, ± STD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 as compared to control. One-way ANOVA for Max Force, Strain at break and Young Modulus, Kruskal-Wallis for UTS. (G) PCA scatter plot of CAM FTIR spectra (4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1) show a significant distinction between control and CAM sterilized with γ Hdr D, but γ Hdr D can not be distinguished from positive control (Glut). (H) PCA scatter plot of CAM FTIR spectra show a significant distinction between control, CAM sterilized with EtO and positive control. (I) PCA scatter plot of CAM FTIR spectra does not show a significant difference between control and CAM sterilized with scCO2. Ellipses cluster the different groups. (J) DSC thermogram of CAM samples shows a significant difference in Td (lowest point of endothermic peak) between control and sterilized CAM (n = 11-12, p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA).

Fig. 3. CAM can be terminally sterilized without modification of its microscopic structure and remain a favorable biomaterial for cell attachment.

Masson’s Trichrome staining on cross sections of CAM ribbons (dashed lines delimit one cross section). (A) The typical dense network of collagen (blue staining) is visible on sterilely produced control CAM ribbons. Devitalized cells are mainly visible at ribbons surface (white arrows). (B) After γ Ldr H sterilization, the microscopic structure of CAM ribbons was modified. Layers within the ribbon are delaminated, thus exposing gaps (black arrows) and increasing ribbons thickness. (C) Microscopic structure of EtO sterilized ribbons is similar to control. Dashed lines outline ribbons, scale bar = 50 μm. Microscopic images of HUVECs after VE-Cadherin (VE-Cad) and nuclear staining on sterilely produced or terminally sterilized CAM sheets. The presence of VE-Cadherin shows an organization of the cell-cell interface, suggesting a normal morphology of the endothelium regardless of the condition ((D) Control, (E) γ Ldr H, (F) scCO2). Scale bar = 50 μm. γ Ldr H: Gamma irradiation with Low dose rate Hydrated, EtO: Ethylene Oxide.

Among sterilizations by irradiation, the γ Ldr H method had the largest effect as cross-sectional area of samples increased (+ 60% of control, Fig. 2B), maximum force and strain decreased (-35% an -25% of control, respectively, Fig. 2C-D), and, logically, UTS and stiffness decreased (-60% and -47% of control, respectively, Fig. 2E-F). Moreover, spectroscopy revealed major modifications at a molecular level of these samples (Fig. 2G). Indeed, PCA of the FTIR spectra revealed a clear distinction between the γ Ldr H and control. The γ Ldr H points even overlapped with the denatured CAM cloud (Glut) suggestive on major damage to the ECM. On the other hand, irradiation with γ Hdr D, γ Ldr D and eBeam only had little impact on the CAM mechanical properties and no effect on molecular structure. Indeed, strength of eBeam ribbons slightly decreased after sterilization (-17% of control, Fig. 2.C) and stiffness of Hdr D, γ Ldr D and eBeam ribbons were modified (-11, -32 and + 11% of control, respectively (Fig. 2F), but no distinction was evidence between control and any of these groups after PCA of FTIR spectra (Suppl. Fig. 2). It should be noted that the only difference between high versus low dose rate gamma sterilization of dry samples was the amplitude of stiffness decrease (-11% vs -32%, Fig. 2F).

Among gaseous sterilization methods, EtO was the sterilization that most modified the CAM properties. Strength and stretchability of EtO samples increased (+ 20% and + 25% of control, respectively, Fig. 2C-D) whereas stiffness decreased (-30% of control) (Fig. 2F). Spectroscopy also revealed significant modifications at a molecular level of these samples. Indeed, PCA of the FTIR spectra revealed a net distinction between EtO and control points clouds, but also between EtO and the denatured CAM (Glut) clouds (Fig. 2H). Conversely, mechanical properties and molecular structure of the scCO2 sterilized CAM were barely modified. Only YM slightly decreased (-12% of control, Fig. 2.F) and scCO2 and control clouds obtained with PCA of FTIR spectra could not be distinguished from one another (Fig. 2I). No clear difference could be observed between irradiated and gaseous sterilized groups in terms of mechanical properties.

Thermal stability after sterilization was also evaluated by DSC on CAM sheets (Fig. 2J). In irradiated samples the Td decreased, reflecting a thermal destabilization of this CAM, while in gaseous sterilized samples the Td increased, reflecting a thermal stabilization of this CAM. Among the irradiated groups, we can see that: (1) the CAM was less thermally destabilized by eBeam than by gamma sterilization (eBeam Td: -8% of control), (2) the CAM was equally destabilized by high or low dose rate gamma sterilization (γ Hdr D and γ Ldr D Td: ≈ -20% of control), and (3) theCAM was less destabilized by gamma sterilization on hydrated than on dry sample (γ Ldr H Td: -12% of control). In gaseous sterilization, the changes in Td were less, and scCO2 sterilization changed the CAM thermal stability the least (scCO2 Td: + 3% of control vs EtO Td: + 5% of control).

CAM ribbons sections were then observed after Masson’s Trichrome (MT) staining to evaluate microscopic alterations after sterilization. For all conditions, blue staining revealed the multilayered structure of the CAM as previously observed. This structure is mainly composed of collagen fibers mostly oriented according to the plane of the sheet in a complex and variable pattern [24]. This matrix is also composed of at least 70 extracellular matrix-related as previously revealed by mass spectroscopy [25]. In Fig. 3A, dense layers of folded ribbons are easily distinguishable in control devitalized CAM (one layer indicated by black dotted line) and cell remnants are visible (white arrows). Conversely, sections of the γ Ldr H sterilized ribbons (Fig. 3B) show delamination with gaps in the ribbon’s microscopic structure (black arrows). This is consistent with a visible increase in ribbon section width as observed with laser measurement (Fig. 2B). Fewer cells are visible as they may have detached and floated away in this more porous structure. All other sterilization conditions (Suppl. Fig. 3E-H), like EtO (Fig. 3C), did not induce any microscopic difference compared to control.

Despite all effects mentioned above, none of the sterilization methods prevented HUVECs from attaching and proliferating on the CAM, even γ Ldr H. Indeed, VE-Cadherin immunostaining (green) showed that cells adhered and formed a confluent monolayer, with organized cell-cell junctions, regardless of sterilization method (Fig. 3D-F and Suppl. Fig. 3I-L). We tested the cytocompatibility of the processed CAM using endothelial cells since we are focused on CAM-based vascular applications and because endothelial cells are known as “sensitive” cells. Taken together, these in vitro results show that only γ Ldr H sterilization has significantly altered the CAM mechanical and physicochemical properties as well as matrix morphology.

6.3. The effect of sterilization on the CAM in vivo remodeling

Devitalized CAM ribbons were sterilized and subcutaneously implanted in immunodeficient rats to determine the influence of sterilization on the in vivo CAM remodeling (Suppl. Fig. 4A). After 2 weeks, 1, 5 and 10 months, the rats were sacrificed and carefully skinned to retrieve the implanted ribbons. After explantation, both mechanical and histological changes were evaluated and compared to those of an implanted aseptically produced control.

At 2 weeks, macroscopic differences were already visible between the γ Ldr H group and other ribbons (Suppl. Fig. 4B). The γ Ldr H sterilized ribbons (white arrows) were more difficult to discern and appeared less white and less thick than other ribbons (black arrows). After 10 months, ribbons were still identifiable under rat skin (Suppl. Fig. 4C). Control and scCO2 sterilized ribbons (black arrows) were found to be slightly whiter and thicker than other ribbons (white arrows).

The evolution of the maximum force of sterilized ribbons during in vivo remodeling, and the ease to explant them, are shown in Fig. 4. Overall, we can note that all sterilizations impacted the CAM remodeling by accelerating the loss of mechanical strength compared to the non-sterilized control (Fig. 4). Indeed, the strength of control ribbons progressively decreased during the course of the implantation (40% of strength remaining after 10 months), whereas the strength of sterilized ribbons decreased abruptly right after implantation and then appeared stabilized (≈ 60% of the strength lost in 2 weeks). Sterilized ribbons were statistically weaker than control at earlier timepoints but these differences progressively disappeared leading to little and no statistical differences observed by 5 and 10 months (Suppl. Fig. 5). The sterilization also impacted the ease of ribbons explantation: control ribbons were all recovered regardless of the implantation time, whereas the retrieval of sterilized ribbons was variable and overall less easy (Fig. 4.B). Sterilization using γ Ldr H conditions appears to have had the most detrimental effect since it both showed very significant and consistent decreases in strength (Suppl. Fig. 5) as well as the worse retrieval level (Fig. 4.B). This is consistent with the in vitro results clearly showing matrix denaturation. Conversely, dry gamma sterilization was among the methods that had the least effect on the mechanical strength caused by the remodeling at 1 month. However, CAM ribbons rehydrated after dry irradiation felt stiffer than ribbons sterilized by gaseous methods (EtO and scCO2) when handled, suggesting some level of denaturation.

Fig. 4. Terminal sterilization accelerates CAM loss of strength in early stages of in vivo remodeling, but may not affect its long-term evolution.

(A) Maximum force of 5-mm-wide CAM ribbons obtained in tensile test as a function of sterilization methods and time (γ Hdr D: Gamma irradiation with High dose rate Dry, γ Ldr D: Gamma irradiation with Low dose rate Dry, γ Ldr H: Gamma irradiation with Low dose rate Hydrated, eBeam: electron Beam irradiation, EtO: Ethylene Oxide, scCO2 : supercritical CO2). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 as compared to control. Two-way ANOVA (n = 1-8). The dotted line indicates the maximum force of non-sterilized non-implanted CAM ribbons. (B) Retrievability of CAM ribbons (easy/hard/not retrievable) for mechanical evaluation as a function of sterilization methods and time.

The inflammatory response during in vivo remodeling was evaluated by histology and immunostaining analysis (Figs. 5 and 6, Suppl. Figs. 6 to 8). We have previously shown that immunodeficient rats are capable of producing an innate immune response that can degrade rapidly a denatured ECM as part of a foreign body reaction (FBR) [14] Despite all precautions taken, small foreign bodies (probably rat hair) were occasionally introduced during subcutaneous implantation of ribbons. A strong FBR was observed confirming our previous observations (Fig. 5A-D). Debris were surrounded by a cluster of cells positive for macrophage markers. M1 phenotype (proinflammatory) was determined by co-labeling with CCR7 (M1) and CD68 (pan macrophage). M2 phenotype (remodeling) was determined by CD206 (M2) and CD68. M1 was the prevalent phenotype consistent with an FBR. In contrast, the immune response to the CAM was low, regardless of the sterilization method (Figs. 5 and 6, Suppl. Figs. 6 to 8). Indeed, no cell clusters or migration fronts were observed in or around the CAM at 2 weeks (Fig. 5) and no fibrous encapsulation nor giant cells developed over time (Fig. 6). At two weeks, a very low response is induced by the control devitalized ribbon (asterisk), and the majority of macrophages displayed M2 phenotype (Fig. 5E-H). Very few macrophages appear to be in the CAM. A few adipocytes can be seen on and between CAM layers when also present in surrounding tissues. The ribbons appear already well integrated in the tissue with fibroblastic looking cells all around the CAM. Only sterilization γ Hdr D and γ Ldr H show a notably stronger immune response than the control, with concentrations of M1 and M2 in ribbon folds (Fig. 5I-L, Q-T). For all other conditions, the reaction was only slightly stronger than for the control, with both M1 and M2 cells visible (Fig. 5E-H, M-P, U-AB). After 1 month, the slight inflammation caused by the subcutaneous insertion of sterilized ribbons with γ Hdr D and γ Ldr H was largely diminished (Fig. 6E-H and Suppl. Fig. 6E-H, M-P), and essentially resolved for the others conditions (Fig. 6A-D, I-L and Suppl. Fig. 6A-D, I-L, Q-AB). After 5 months, the inflammation of all conditions was resolved, even for the ribbons sterilized with γ Hdr D and γ Ldr H (Fig. 6M-T and Suppl. Fig. 7). After 10 months, ribbons were still easily identifiable and well-integrated into surrounding tissues regardless of the condition. (Fig. 6U-AB and Suppl. Fig. 8). Taken together, these results indicate that (1) the sterilized CAM does not induce strong FBR and persist subcutaneously for at least 10 months in immunosuppressed rats, (2) sterilization accelerate the CAM in vivo remodeling and (3) scCO2 sterilization had the least effect whereas γ Hdr D and γ Ldr H were the most inflammatory treatments.

Fig. 5. CAM can be terminally sterilized without substantial increase of the acute immune response.

Histological analyses of sterilized CAM ribbons at 2 weeks (TM, H&E, Immunofluorescence for M1/M2 phenotype) in the immunodeficient rats. Asterisk (*) indicates the position of the ribbon delimited by the dashed lines. (A)(B) Foreign bodies (possibly rat hair, white arrows) are surrounded by numerous inflammatory cells (round dark purple). (C) Immunostaining for CD68 (red) labels macrophages and double staining with CCR7 (yellow) suggest large number of macrophages with a M1 phenotype (pro-inflammatory). (D) Immunostaining for CD68 (red) labels macrophages and double staining with CD206 (yellow) show few M2 macrophages (remodeling phenotype). Insets show high magnification views of doubly labelled cells showing membrane staining of CCR7/CD206 while CD68 stains cellular organelles. (E)(F) Very few inflammatory cells surround the control CAM ribbon, and adipocytes (yellow arrows) are present between ribbon layers. (G)(H) Double staining with CD68/CCR7 compared to double staining with CD68/CD206 suggest a majority of macrophages with a M2 phenotype. (I)(J) Inflammatory cell clusters (red arrows) are visible within the ribbon and between the folds it forms. Black arrows indicate blood vessels. (K)(L) Double staining suggests a majority of macrophages with a M1 phenotype. (M)-(P) The few macrophages present between the layers of the γ Ldr D sterilized ribbon are predominantly M1 phenotype. (Q)(R) Inflammatory cell clusters are visible within the γ Ldr H sterilized ribbon and between the folds it forms. (S)(T) CD68 labeled macrophages are either double stained with CCR7 or with CD206 showing the presence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. (U)-(X) The few macrophages present around and between the EtO-sterilized ribbon layers are slightly more co-stained with CD206 than with CCR7, suggesting a slight majority of M2 phenotype. (Y)-(AB) The few macrophages present around and between the scCO2-sterilized ribbon layers are double-stained with either CD206 or CCR7, indicating M1 and M2 phenotypes. Scale bar = 100 μm (close up scale bar = 5 μm).

Fig. 6. CAM can be terminally sterilized with no risk of chronic immune reaction.

Histological analyses of sterilized CAM ribbons at 1, 5 and 10 months (TM, H&E, M1/M2 phenotype) in the immunodeficient rats. Asterisk (*) indicates the position of the ribbon delimited by the dashed lines. (A)(B) Hardly any inflammatory cells surround the control CAM ribbon. Black arrows indicate blood vessels. (C)(D) Barely any cell is stained with CD68 (red, labelling for macrophages) and no double staining (yellow) with either CCR7 nor with CD206 shows the absence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. (E)-(H) The few macrophages present between the layers of the γLdr H sterilized ribbon are predominantly M2 phenotype. The red arrow indicates inflammatory cells (round dark purple). (I)(J) Very few inflammatory cells are present around and between the scCO2-sterilized ribbon layers. (K)(L) Barely any cell is double stained with CD68/CCR7 nor CD68/CD206, showing the quasi-absence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. (M)(N) Hardly any inflammatory cells surround the control CAM ribbon. (O)(P) Only one cell is double stained with CD68 and CCR7 showing the quasi-absence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. (Q)-(T) The rare macrophages present surrounding the γ Ldr H sterilized ribbon are M2 phenotype. (U)(V) Hardly any inflammatory cells surround the control CAM ribbon. (W)(X) Only one cell is double stained with CD68 and CCR7 (M1 phenotype) showing the quasi-absence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. (Y)(Z) Hardly any inflammatory cells surround the γ Ldr H CAM ribbon, and a few adipocytes are present between ribbons layers (yellow arrows). (AA)(AB) Only one cell is double stained with CD68 and CCR7 (M1 phenotype) showing the quasi-absence of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. Scale bar = 100 μm.

7. Discussion

In previous studies, the CAM composition has been characterized, the in vivo remodeling of the CAM has been investigated, and its use as a “human textile” has been presented [5,14,24]. In this study, we wanted to find a storage strategy and a terminal sterilization method to facilitate the transition of CAM-based products to the clinic.

7.1. Effects of long-term storage on matrix

The first objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of long-term storage on the CAM in order to determine the most appropriate method for our matrix. Previous work had shown that CAM rolled and fused as a vascular graft did not lose mechanical properties after 1 year of storage at -80 °C dehydrated [26]. In this study, we not only confirmed these results at -80 °C but also at -20 °C. We also showed the absence of physicochemical damage after frozen-storage using standard characterization methods for biomaterials characterization. The -80 °C storage is widespread in the academic environment but is not commonly available in the clinic. We therefore evaluated the effect of long-term storage in conditions compatible with routine use. We saw that air-dried non-frozen storage (4 °C and RT) resulted in changes of CAM mechanical properties such as volume loss, strength and stiffness increase. Interestingly, we also noticed that the dehydration of CAM led to a large decrease in volume (≈ -75%), and a large increase in strength and stiffness (≈ + 80% and ≈ + 500%, respectively, Suppl. Fig. 1) after rehydration. Moreover, storage at RT increased the effect of dry storage. Freytes et al. studied the mechanical properties of a lyophilized and sterilized matrix derived from porcine urinary bladder (UBM) after 1 year of storage at 4 °C and RT [27]. Similar to our results, they saw an increase of UBM strength (+ 54% of control) and tangential stiffness (+ 74%) after 1 year of storage at RT, and these changes were less important at 4 °C. They also saw an increase in strain after storage at 4 °C, that we did not observe with our matrix, but did not measure matrix volume changes. They concluded that structural changes slowly occurred during storage as a function of time and temperature, which is in accordance with our results. In the literature, it has been shown that the absence of water leads to an increase in thermal stability of collagen-type peptides, and that these modifications can be irreversible with severe dehydration [28]. Our hypothesis is that the CAM, mainly composed of collagen [24], continues to dehydrate over time when stored dry at 4 °C and RT, exceeding a certain threshold beyond which rehydration is not possible within a few hours. This phenomenon may be caused by cross-linking of the matrix as hypothesized by Freytes et al. as well as Silver et al. [27, 29]. Consistent with this hypothesis, CAM properties appeared more modified by storage at RT than at 4 °C. In addition to suggesting structural alterations, the inability of CAM to return to its initial volume can impede the functionality of some Tissue-Engineered Products (TEP), such as a woven vascular graft whose walls would become too permeable after rehydration [15]. Combine with the fact that rehydration adds additional time and handling, non-frozen dry storage is not an optimal solution for this matrix. Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that a longer rehydration time, not applicable in the clinic and therefore not evaluated here, would modify these results.

We also tested storage conditions that are compatible with a “ready to use” product. CAM stored in PBS at RT or 4 °C for 1 year showed only a slight loss in volume and in strain at failure, suggesting that these are excellent conditions for long-term storage of the CAM in a clinical setting. Loss of strain at failure after 1-year storage at 4 °C in PBS with antibiotics was also found by Baiguera et al. on bioengineered human tracheas but is was much more important than with the CAM (-48% of control) [30]. And, unlike us, they reported a loss a strength and stiffness (-50% and -25% of control, respectively). After biochemical analysis (enzymatic degradation test) and conventional matrix visualization (histological staining and scanning electron microscopy), they concluded to a denaturation of their matrix structure. Bonenfant et al. also reported a loss of architecture of mice lung matrices after 6 months at 4 °C in PBS with antibiotics [31], as well as Urbani et al. who showed signs of degradation of rabbit esophageal scaffold after similar storage [32]. They also showed a loss of stiffness (-67%) and UTS (-50%) after storage. Similar to this study, Tondreau et al. showed a loss in volume (-24% of control) of their tissue-engineered fibroblasts-derived vascular scaffold after 3 months of storage in deionized water at 4 °C [33]. However, they also observed a loss of strength: a decrease in burst pressure and in suture retention (-24% of control for both). A decrease in burst pressure (-21% of control) after 1 year of storage at 4 °C in PBS was also reported by Dahl et al. on their human extracellular matrix, as well as a decrease in compliance (-25% of control) although these differences were not statistically significant31. The mechanical properties of the CAM were much less affected by hydrated storage at 4C than in these studies. This may be due to its specific structure and composition, or could be linked to differences in storage media (distilled water vs PBS). In addition, some of these matrices were decellularized using harsh chemicals which might have made the matrix less stable [34].

7.2. Effects of sterilization on matrix

The second objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of different sterilization methods on CAM to determine which had the least denaturing effect. Gamma irradiation has been a major player in sterilization for decades and is an attractive method (effective, low temperature, without toxic residues, easy to control, relatively inexpensive, performed easily on final packaging) [35–37]. However, it is not appropriate for all biomaterial as it can induce structural alterations and collagen degradation inducing mechanical weakening that affect biomaterials in vivo functionality [38]. The present study investigated two parameters of gamma irradiation to adapt the method to CAM sterilization: the dose rate and the hydration of samples.

In radiotherapy, it is well established that the radiation dose as well as the irradiation dose rate are important [39–41]. Dose effects have been investigated for the sterilization of sensitive biomaterials [42–44]. To our knowledge, this is the first study looking at the effect of dose rate on an extracellular matrix. In vitro analyses we performed barely showed any statistically significant differences between high and low dose rate gamma sterilized CAM. However, in vivo results showed that high, but not low, dose rate gamma sterilization increased much more the acute foreign body reaction. This discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo results are a reminder of the limitations of in vitro research [45]. While convenient, these commonly used biomaterials characterization tests were not predictive of in vivo results, although animal models obviously have their own limitations [46].

Our group and others have reported a decrease in volume of their biological matrix after gamma sterilization on dry samples, which may impair the functionality of some TEPs as previously discussed [15,47]. In anticipation of this undesired effect, the CAM was gamma sterilized in its hydrated state as proposed by Grémare et al. for their human amniotic membrane, and effects were evaluated [15]. However, the dry CAM did not, as expected, lose its ability to fully recover its hydrated volume after standard dry gamma sterilization. This difference between in vivo and in vitro synthesized human ECM maybe due to different organization or composition, or to some methodology differences. As for hydrated sterilization, it caused an important (≈70%) CAM swelling upon rehydration and loss of CAM mechanical strength and stiffness. This loss of strength was not unexpected since other groups have reported that radiations interact with water leading to the production of free radicals that increases the scission of collagen molecules by cutting peptide bonds and to unnatural collagen crosslinking [48–51]. This increase amount of cross-linking is consistent with the thermal stabilization of the hydrated versus dry gamma-sterilized CAM observed by the DSC analysis and by the similarities between the FTIR spectra of the hydrated gamma-sterilized CAM with a glutaraldehyde-reticulated CAM. The denaturation of the CAM by wet gamma sterilization was confirmed by a stronger and longer immune response during the in vivo remodeling, making this method inappropriate for our material.

Electron beam (eBeam) sterilization was also tested on the CAM as an irradiative method similar to gamma irradiation, but for which the irradiation source is an accelerated electron beam. This method is considerably faster than conventional gamma sterilization (seconds vs hours) with similar efficiency, which is very advantageous in terms of manufacturing process, but has a low penetration rate (< 2 cm depth) [51,52]. As expected, since mechanisms of action are identical, in vitro results were similar to those of conventional gamma sterilization. However, DSC analysis suggested better thermal stability of eBeam vs. gamma sterilized CAM. This difference could be due to the absence of matrix oxidation that is, according to Deepalaxmi et al., negligible within the very short exposure period [52]. However, Faraj et al. reported a similar decrease in Td after gamma and eBeam sterilization of their collagen scaffold from bovine tendon [53]. As previously, further in vitro analyses would be necessary to understand the underlying mechanisms explaining this difference. Overall, the denaturation of CAM was slightly reduced by eBeam sterilization for a faster sterilization time. Therefore, eBeam sterilization appears to be a good alternative to gamma sterilization for thin samples.

Ethylene oxide sterilization is a gaseous sterilization technique that is widely used in hospitals and the industry. It is effective, inexpensive and used for commercialized ECM-based products (Biodesign®, Cook Biomedical) [54]. In this study, it was found that the CAM strength and strain at rupture were improved after EtO sterilization. The molecular structure of the CAM was changed according to FTIR spectra analysis and thermal stability was increased as suggested by DSC evaluation. Faraj et al. were able to observe an increase in UTS of their scaffold after EtO sterilization, Dearth et al. saw a slight increase (not significant) in their porcine dermal scaffold strength (+ 25% of control), and Freytes et al. reported an increase in strain at rupture of 64% of control of UBM [12, 27, 53]. Monaco et al. also saw an increase in the thermal stability of their collagen scaffold derived from calfskin (+ 10 °C) [12, 53, 55]. All these small increases in strength are consistent with some level of crosslinking after treatment with this reactive chemical. It should be noted that ethylene oxide can leave toxic residues on the sterilized products and required the handling of a dangerous gas. However, abundant rinsing of samples before sterilization and intensive degassing after sterilization helps avoid toxic residues in the final product [56,57]. As was the case in this study, Faraj et al., Dearth et al. and Monaco et al. observed no cytotoxicity or inhibition of cellular proliferation after sterilization. The CAM changes observed in vitro did not trigger a strong foreign body immune response, similar to Dearth et al. after implantation of their matrix into the rat abdominal wall up to 35 days. Overall, EtO sterilization is a method widely accepted by the scientific community and by regulatory agencies that has slightly modified the CAM but with no in vivo consequences, so it represents a good potential solution for the sterilization of our matrix.

A more recently developed alternative is a sterilization process based on supercritical CO2 (scCO2) combined with small amounts of peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide [58–61]. Other authors using this sterilization technique with biological matrices also reported no or very little alteration of mechanical, physicochemical, histological or biological functions [59, 62–66]. In our study, this method was consistently among the least denaturing methods regardless of the evaluation. In vitro, mechanical testing only showed a slight decrease in stiffness, FTIR detected no major molecular structure modification, DSC revealed the smallest change in thermal stability, and no microscopic alterations nor cytotoxicity was detected. In vivo, no strong inflammatory response was triggered. Supercritical CO2 appears therefore the most promising method for CAM sterilization. However, this technique is relatively new and it is not one of the methods approved by the regulatory agencies (i.e., heat, gamma, EtO) [61] Hence, the use of this process for commercial applications of the CAM would likely require a more thorough validation to obtain regulatory approval.

A possible limitation of these results is that CAM tissues were not preconditioned before mechanical testing, and that the potential inelasticity of this tissue was not investigated.

The implantation model used in this in vivo study, which enables the implantation of a significant amount of tissue, allowed the analysis of both the histological response of the host and the mechanical evolution of the implanted tissue. From a histological perspective, an inflammatory reaction, although very low, was detected. From a mechanical standpoint, an abrupt loss of strength of the implanted sterilized tissues was initially observed, then the discrimination between sterilized and non-sterilized tissues became less. However, the animal model used obviously has its limitations. CAM was implanted subcutaneously, which is not necessarily predictive of the tissue remodeling at other sites. In addition, little or no mechanical stress is applied in the subcutaneous position. However, these stimuli, which can be very intense at other sites (e.g. in the cardio vascular system), significantly influence tissue remodeling [67]. Finally, although immunocompromised rats are capable of producing a functional innate immune response, information regarding the adaptive immune system is lacking. Therefore, further studies in immunocompetent animals at relevant implant sites will be required to complete this study.

8. Conclusion

This study addresses manufacturing issues that are critical to the future transition of CAM-based TEP to the clinic. CAM was found to be extremely stable in storage as it can be kept at least 1 year frozen dry with no alteration. In addition, cold storage in PBS only slightly altered the mechanical and physicochemical properties of CAM, allowing CAM-based TEPs to be available off-the-shelf in the clinical environment. Some gas sterilization methods, particularly with scCO2, caused little changes to the CAM’s mechanical, morphological and physicochemical properties and elicited only a minor increase in the acute immune response when implanted in the immunodeficient rat. After 10 months in the subcutaneous environment, sterilized CAM was still present and slowly remodeled. Together, these results show that the CAM can truly be considered a “bio” material with properties that are compatible with numerous clinical applications in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

In the field of tissue engineering, the use of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins as a scaffolding biomaterial has become very popular. Recently, many investigators have focused on ECM produced by cells in vitro to produce unprocessed biological scaffolds. As this new kind of “biomaterial” becomes more and more relevant, it is critical to consider key manufacturing questions to facilitate future transition to the clinic. This article presents an extensive evaluation of long-term storage stability and terminal sterilization effects on an extracellular matrix assembled by cells in vitro. We believe that this article will be of great interest to help tissue engineers involved in so-called scaffold-free approaches to better prepare the translation from benchtop to bedside.

Table 1. Summary of sterilization methods.

| Abbreviation | Sterilization method | Sterilization parameters | CAM hydration state at sterilized |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ Hdr D | Gamma irradiation High dose rate Dry |

Dose rate: mean 2 kGy/h, min. 0.5 kGy/h, max. 20 kGy/h |

Dry |

| γ Ldr D | Gamma irradiation Low dose rate Dry |

Dose rate: 0.5 kGy/h | Dry |

| γ Ldr H | Gamma irradiation Low dose rate Hydrated |

Dose rate: 0.5 kGy/h | Hydrated |

| eBeam | Electron beam irradiation | Dose rate: 300 kGy/min | Dry |

| EtO | Ethylene oxide | Exposure time: 17 h Aeration time: 50 h |

Dry |

| scCO2 | Supercritical CO2 | Presence of peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide buffer |

Dry |

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the European Research Council (Advanced Grant # 785908). We thank Benoit Rousseau, Philippe Barthelemy, Yoann Torres, Cécile Montfoulet, Gaetan Roudier, Mélanie Estiez, Audrey Michot and Sébastien Marais for their support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Diane Potart: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Maude Gluais: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Alexandra Gaubert: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation. Nicolas Da Silva: Investigation, Data curation. Marie Hourques: Investigation, Data curation. Marie Sarrazin: Investigation, Data curation. Julien Izotte: Methodology, Investigation, Resources. Léa Mora Charrot: Investigation. Nicolas L’Heureux: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations. However, the corresponding author will be happy to share any data used to prepared this manuscript with any researcher upon simple request.

References

- [1].U.S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrialsgov-Tissue engineering. [accessed April 9, 2022]. (n.d.). https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=tissue+engineering&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=

- [2].Alliance for Regenerative Medicine. Alliance for regenerative medicine, Available products. 2023. (n.d.). https://alliancerm.org/available-products/

- [3].Ghaemi RV, Siang LC, Yadav VG. Improving the rate of translation of tissue engineering products. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8:1900538. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wystrychowski W, Garrido SA, Marini A, Dusserre N, Radochonski S, Za-galski K, Antonelli J, Canalis M, Sammartino A, Darocha Z, Baczyn’ ski R, et al. Long-term results of autologous scaffold-free tissue-engineered vascular graft for hemodialysis access. J Vasc Access. 2022:112972982210959. doi: 10.1177/11297298221095994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Magnan L, Labrunie G, Fénelon M, Dusserre N, Foulc M-P, Lafourcade M, Svahn I, Gontier E, Vélez JH, McAllister VTN, L’Heureux N. Human textiles: A cell-synthesized yarn as a truly “bio” material for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2020;105:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kartoglu UH, Moore KL, Lloyd JS. Logistical challenges for potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and a call to research institutions, developers and manufacturers. Vaccine. 2020;38:5393–5395. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lawson JH, Glickman MH, Ilzecki M, Jakimowicz T, Jaroszynski A, Peden EK, Pilgrim AJ, Prichard HL, Guziewicz M, Przywara S, Szmidt J, et al. Bioengineered human acellular vessels for dialysis access in patients with end-stage renal disease: two phase 2 single-arm trials. Lancet. 2016;387:2026–2034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00557-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eudy M, Eudy CL, Roy S. Apligraf as an alternative to skin grafting in the pediatric population. Cureus. 2021 doi: 10.7759/cureus.16226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Domaszewska-Szostek A, Krzyzanowska M, Siemionow M. Cell-based therapies for chronic wounds tested in clinical studies: review. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83:e96–e109. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].European Medicines Agency (EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/850374/2015) Guideline on the sterilisation of the medicinal product, active substance, excipient and primary container. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gorham SD, Srivastava S, French DA, Scott R. The effect of gamma-ray and ethylene oxide sterilization on collagen-based wound-repair materials. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1993;4:40–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00122976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dearth CL, Keane TJ, Carruthers CA, Reing JE, Huleihel L, Ranallo CA, Kollar EW, Badylak SF. The effect of terminal sterilization on the material properties and in vivo remodeling of a porcine dermal biologic scaffold. Acta Biomater. 2016;33:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].L’Heureux N, Dusserre N, Konig G, Victor B, Keire P, Wight TN, Chronos AFN, Kyles AE, Gregory CR, Hoyt G, Robbins RC, et al. Human tissue-engineered blood vessels for adult arterial revascularization. Nat Med. 2006;12:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nm1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Magnan L, Kawecki F, Labrunie G, Gluais M, Izotte J, Marais S, Foulc M-P, Lafourcade M, L’Heureux N. In vivo remodeling of human cell-assembled extracellular matrix yarns. Biomaterials. 2021;273:120815. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Grémare A, Thibes L, Gluais M, Torres Y, Potart D, Da Silva N, Dusserre N, Fénelon M, Senthilhes L, Lacomme S, Svahn I, et al. Development of a vascular substitute produced by weaving yarn made from human amniotic membrane. Biofabrication. 2022 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ac84ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Toniolo I, Fontanella CG, Foletto M, Carniel EL. Coupled experimental and computational approach to stomach biomechanics: Towards a validated characterization of gastric tissues mechanical properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2022;125:104914. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Griffin M, Premakumar Y, Seifalian A, Butler PE, Szarko M. Biomechanical characterization of human soft tissues using indentation and tensile testing. JoVE. 2016:54872. doi: 10.3791/54872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thébaud NB, Aussel A, Siadous R, Toutain J, Bareille R, Montembault A, David L, Bordenave L. Labeling and qualification of endothelial progenitor cells for tracking in tissue engineering: an in vitro study. Int J Artif Organs. 2015;38:224–232. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wertheim MG. Monthly Retrospect of the Medical Sciences. 2. Vol. 1. Alexander Fleming and W.T. Gairdner; 1848. On the elasticity and cohesion og the principal tissues of the human body. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ridge MD, Wright V. A bio-engineering study of the mechanical properties of human skin in relation to its structure. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:639–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1965.tb14595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schroepfer M, Meyer M. DSC investigation of bovine hide collagen at varying degrees of crosslinking and humidities. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;103:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tang R, Samouillan V, Dandurand J, Lacabanne C, Nadal-Wollbold F, Casas C, Schmitt A-M. Thermal and vibrational characterization of human skin: influence of the freezing process. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;127:1143–1154. doi: 10.1007/s10973-016-5384-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang Y, Chen Z, Liu X, Shi J, Chen H, Gong Y. SEM, FTIR and DSC investigation of collagen hydrolysate treated degraded leather. J Cult Herit. 2021;48:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2020.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Magnan L, Labrunie G, Marais S, Rey S, Dusserre N, Bonneu M, Lacomme S, Gontier E, L’Heureux N. Characterization of a cell-assembled extracellular matrix and the effect of the devitalization process. Acta Biomater. 2018;82:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kawecki F, Gluais M, Claverol S, Dusserre N, McAllister T, L’Heureux N. Inter-donor variability of extracellular matrix production in long-term cultures of human fibroblasts. Biomater Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1039/D1BM01933C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wystrychowski W, McAllister TN, Zagalski K, Dusserre N, Cierpka L, L’Heureux N. First human use of an allogeneic tissue-engineered vascular graft for hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1353–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Freytes DO, Tullius RS, Badylak SF. Effect of storage upon material properties of lyophilized porcine extracellular matrix derived from the urinary bladder. J Biomed Mater Res. 2006;78B:327–333. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mogilner IG, Ruderman G, Grigera JR. Collagen stability, hydration and native state. J Mol Graph Model. 2002;21:209–213. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(02)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Silver FH, Christiansen DL, Snowhill PB, Chen Y. Role of storage on changes in the mechanical properties of tendon and self-assembled collagen fibers. Connect Tissue Res. 2000;41:155–164. doi: 10.3109/03008200009067667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Baiguera S, Del Gaudio C, Jaus MO, Polizzi L, Gonfiotti A, Comin CE, Bianco A, Ribatti D, Taylor DA, Macchiarini P. Long-term changes to in vitro preserved bioengineered human trachea and their implications for decellu-larized tissues. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3662–3672. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bonenfant NR, Sokocevic D, Wagner DE, Borg ZD, Lathrop MJ, Lam YW, Deng B, De Sarno MJ, Ashikaga T, Loi R, Weiss DJ. The effects of storage and sterilization on de-cellularized and re-cellularized whole lung. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3231–3245. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Urbani L, Maghsoudlou P, Milan A, Menikou M, Hagen CK, Totonelli G, Camilli C, Eaton S, Burns A, Olivo A, De Coppi P. Long-term cryopreservation of decellularised oesophagi for tissue engineering clinical application. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tondreau MY, Laterreur V, Gauvin R, Vallières K, Bourget J-M, Lacroix D, Tremblay C, Germain L, Ruel J, Auger FA. Mechanical properties of endothe-lialized fibroblast-derived vascular scaffolds stimulated in a bioreactor. Acta Biomater. 2015;18:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233–3243. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bailey AJ, Bendall JR, Rhodes DN. The effect of irradiation on the shrinkage temperature of collagen. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1962;13:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0020-708X(62)90136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Abdel-Fattah AA, Berejka AJ, Chmielewski AG, Dettlaff KD, Dziedz-ic-Goclawska A, Mohammad H-S, Hammad AA, Hegazy E-SA, Kaluska IM, Kaminski A, Marciniec B, et al. Trends in Radiation Sterilization of Health Care Products. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); Vienna: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dai Z, Ronholm J, Tian Y, Sethi B, Cao X. Sterilization techniques for biodegradable scaffolds in tissue engineering applications. J Tissue Eng. 2016;7:204173141664881. doi: 10.1177/2041731416648810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Harrell CR, Djonov V, Fellabaum C, Volarevic V. Risks of using sterilization by gamma radiation: the other side of the coin. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:274–279. doi: 10.7150/ijms.22644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hall EJ, Brenner DJ. The dose-rate effect revisited: Radiobiological considerations of importance in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 1991;21:1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90314-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Olofsson D, Cheng L, Fernández RB, Płódowska M, Riego ML, Akuwudike P, Lisowska H, Lundholm L, Wojcik A. Biological effectiveness of very high gamma dose rate and its implication for radiological protection. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2020;59:451–460. doi: 10.1007/s00411-020-00852-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brooks AL, Hoel DG, Preston RJ. The role of dose rate in radiation cancer risk: evaluating the effect of dose rate at the molecular, cellular and tissue levels using key events in critical pathways following exposure to low LET radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2016;92:405–426. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2016.1186301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Edwards JH, Herbert A, Jones GL, Manfield IW, Fisher J, Ingham E. The effects of irradiation on the biological and biomechanical properties of an acellular porcine superflexor tendon graft for cruciate ligament repair: properties of an acellular tendon graft following irradiation. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2017;105:2477–2486. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Helder MRK, Hennessy RS, Spoon DB, Tefft BJ, Witt TA, Marler RJ, Pislaru SV, Simari RD, Stulak JM, Lerman A. Low-dose gamma irradiation of decellularized heart valves results in tissue injury in vitro and in vivo. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2016;101:667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Herbert A, Edwards JH, Jones GL, Ingham E, Fisher J. The effects of irradiation dose and storage time following treatment on the viscoelastic properties of decellularised porcine super flexor tendon. J Biomech. 2017;57:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pearson RM. In-vitro techniques: can they replace animal testing?*. Hum Reprod. 1986;1:559–560. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Akhtar A. The flaws and human harms of animal experimentation. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2015;24:407–419. doi: 10.1017/S0963180115000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gouk S-S, Lim T-M, Teoh S-H, Sun WQ. Alterations of human acellular tissue matrix by gamma irradiation: histology, biomechanical property, stability, in vitro cell repopulation, and remodeling. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2008;84B:205–217. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Singh R, Singh D, Singh A. Radiation sterilization of tissue allografts: a review. World J Radiol. 2016;8:355. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i4.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hamer AJ, Stockley I, Elson RA. J Bone Jt Surg. 81-B. British: 1999. Changes in allograft bone irradiated at different temperatures; pp. 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Borrely SI, Cruz AC, Del Mastro NL, Sampa MHO, Somessari ES. Radiation processing of sewage and sludge. A review. Prog Nucl Energy. 1998;33:3–21. doi: 10.1016/S0149-1970(97)87287-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dziedzic-Goclawska A, Kaminski A, Uhrynowska-Tyszkiewicz I, Stachow-icz W. Irradiation as a safety procedure in tissue banking. Cell Tissue Bank. 2005;6:201–219. doi: 10.1007/s10561-005-0338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Deepalaxmi R, Rajini V. Gamma and electron beam irradiation effects on SiR-EPDM blends. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2014;7:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jrras.2014.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Faraj KA, Brouwer KM, Geutjes Elly PJ, Versteeg M, Wismans RG, De-prest JA, Chajra H, Tiemessen DM, Feitz WFJ, Oosterwijk E, Daamen WF, et al. The effect of ethylene oxide sterilisation, beta irradiation and gamma irradiation on collagen fibril-based scaffolds. Tissue Eng Regener Med. 2011:460–470. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Delgado LM, Pandit A, Zeugolis DI. Influence of sterilisation methods on collagen-based devices stability and properties. Expert Rev Med Dev. 2014;11:305–314. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2014.900436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Monaco G, Cholas R, Salvatore L, Madaghiele M, Sannino A. Sterilization of collagen scaffolds designed for peripheral nerve regeneration: Effect on microstructure, degradation and cellular colonization. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;71:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-USA. Ethylene Oxide “Gas” sterilization guideline for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities. 2008. [accessed March 15, 2023]. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/sterilization/ethylene-oxide.html#print .

- [57].Mendes GCC, Brandão TRS, Silva CLM. Ethylene oxide sterilization of medical devices: a review. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].White A, Burns D, Christensen TW. Effective terminal sterilization using supercritical carbon dioxide. J Biotechnol. 2006;123:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Balestrini JL, Liu A, Gard AL, Huie J, Blatt KMS, Schwan J, Zhao L, Broekelmann TJ, Mecham RP, Wilcox EC, Niklason LE. Sterilization of lung matrices by supercritical carbon dioxide. Tissue Eng Part C: Methods. 2016;22:260–269. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2015.0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tovar N, Witek L, Neiva R, Marão HF, Gil LF, Atria P, Jimbo R, Caceres EA, Coelho PG. In vivo evaluation of resorbable supercritical CO2-treated collagen membranes for class III furcation-guided tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res. 2019;107:1320–1328. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ribeiro N, Soares GC, Santos-Rosales V, Concheiro A, Alvarez-Lorenzo C, García-González CA, Oliveira AL. A new era for sterilization based on supercritical CO 2 technology. J Biomed Mater Res. 2020;108:399–428. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Irani M, Lovric V, Walsh WR. Effects of supercritical fluid CO2 and 25 kGy gamma irradiation on the initial mechanical properties and histological appearance of tendon allograft. Cell Tissue Bank. 2018;19:603–612. doi: 10.1007/s10561-018-9709-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hennessy RS, Jana S, Tefft BJ, Helder MR, Young MD, Hennessy RR, Stoyles NJ, Lerman A. Supercritical carbon dioxide-based sterilization of de-cellularized heart valves. JACC: Basic Transl Sci. 2017;2:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hennessy RS, Go JL, Hennessy RR, Tefft BJ, Jana S, Stoyles NJ, Al-Hijji MA, Thaden JJ, Pislaru SV, Simari RD, Stulak JM, et al. Recellularization of a novel off-the-shelf valve following xenogenic implantation into the right ventricular outflow tract. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Baldini T, Caperton K, Hawkins M, McCarty E. Effect of a novel sterilization method on biomechanical properties of soft tissue allografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:3971–3975. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wehmeyer JL, Natesan S, Christy RJ. Development of a sterile amniotic membrane tissue graft using supercritical carbon dioxide. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21:649–659. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:802–812. doi: 10.1038/nrm3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations. However, the corresponding author will be happy to share any data used to prepared this manuscript with any researcher upon simple request.