Abstract

Hypertension management is directed by cuff blood pressure (BP), but this may be inaccurate, potentially influencing cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and health costs. This study aimed to determine the impact on CVD events and related costs of the differences between cuff and invasive SBP.

Microsimulations based on Markov modelling over one year were used to determine the differences in the number of CVD events (myocardial infarction or coronary death, stroke, atrial fibrillation or heart failure) predicted by Framingham risk and total CVD health costs based on cuff SBP compared with invasive (aortic) SBP. Modelling was based on international consortium data from 1678 participants undergoing cardiac catheterization and 30 separate studies. Cuff underestimation and overestimation were defined as cuff SBP less than invasive SBP and cuff SBP greater than invasive SBP, respectively.

The proportion of people with cuff SBP underestimation versus overestimation progressively increased as SBP increased. This reached a maximum ratio of 16 : 1 in people with hypertension grades II and III. Both the number of CVD events missed (predominantly stroke, coronary death and myocardial infarction) and associated health costs increased stepwise across levels of SBP control, as cuff SBP underestimation increased. The maximum number of CVD events potentially missed (11.8/1000 patients) and highest costs ($241 300 USD/1000 patients) were seen in people with hypertension grades II and III and with at least 15 mmHg of cuff SBP underestimation.

Cuff SBP underestimation can result in potentially preventable CVD events being missed and major increases in health costs. These issues could be remedied with improved cuff SBP accuracy.

Keywords: cardiovascular systems, healthcare economics, high blood pressure, BP, blood pressure, CVD, cardiovascular disease, HDL, high-density lipoprotein

Introduction

High blood pressure (BP) is the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) with an annual global economic cost estimated at over USD$900 billion [1,2]. Cuff measured BP (cuff BP) is used universally for the diagnosis and management of high BP. Despite this method involving recording at the upper arm, the fundamental goal is to estimate the BP within the large central arteries (e.g. proximal aorta) [3] as an indication of pressure exposure to the vital organs. This is not easy to achieve with precision using cuff BP, as there may be sizable inter-individual variability in the SBP occurring at the large central arteries compared with the upper arm (e.g. from no difference to upper arm SBP being >30 mmHg higher than aortic SBP) [4]. Indeed, using a meta-analysis approach, we recently demonstrated a level of difference in cuff BP (compared with intra-arterial aortic BP) that would theoretically result in many people being incorrectly classified across hypertension thresholds [5].

Underestimation of an individual's true intra-arterial aortic SBP by cuff SBP at a clinic visit could lead to an under-appreciation of the true CVD risk from high SBP and thus, miss an opportunity to intervene with lifestyle or antihypertensive medications to reduce CVD risk. Conversely, cuff SBP overestimation could result in over medication and associated avoidable costs and side effects. Even relatively small errors in cuff SBP are estimated to have large public health effects. An underestimation of 5 mmHg may lead to missing 21 million people who may benefit from treatment to lower BP in the United States [6]. To our knowledge, the potential impact of the difference in cuff SBP and intra-arterial aortic SBP (invasive SBP) on CVD events and related costs has not been determined and was the aim of this study. Estimation of the risk of CVD events by comparison of cuff SBP versus invasive SBP was conducted with consideration of CVD risk factors (e.g. cholesterol, age, smoking) in addition to SBP, according to an absolute CVD risk management approach as recommended in many guidelines.

Methods

Study overview

Framingham CVD risk equations were used to estimate the risk of a future CVD event of coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction or coronary death), stroke, atrial fibrillation or heart failure with either cuff SBP or invasive (intra-arterial) aortic SBP. The analysis was conducted from data within an international consortium designed to understand the accuracy of cuff BP compared with intra-arterial BP (INvaSivE blood PressurE ConsorTium: INSPECT), where cuff BP was recorded simultaneously with, or in the immediate period of, invasive BP [5]. Data was derived from an individual participant level meta-analysis, and participants mostly comprised those with an indication for coronary artery angiography [5]. The University of Tasmania Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (reference: H0015048).

Data from participants at least 30 years of age were included when there was complete data of cuff SBP, invasive aortic SBP, age, and sex (from 30 of the 59 individual studies within INSPECT). The rationale for comparing cuff to invasive aortic BP has been detailed previously [5,7]. In brief, cuff BP is intended to estimate the pressure load on the vital organs at the central aortic BP level, and we hypothesize that this pressure (rather than pressure at the arm, which may be different) is a better risk estimate of heart disease and stroke. Participants were classified into two groups, either underestimation of SBP when the cuff SBP was lower than invasive SBP (cuff SBP < invasive SBP), or overestimation of SBP when cuff SBP was higher than invasive SBP (cuff SBP > invasive SBP). An underestimation of CVD risk (and underestimation of CVD events and costs) occurred when cuff SBP was less than invasive SBP, whereas an overestimation of CVD risk (and overestimation of CVD events and costs) occurred when cuff SBP was higher than invasive SBP.

Modelling of cardiovascular events and associated health costs

A microsimulation Markov model using TreeAge software [8] was used to estimate the number of CVD events in one year and costs of acute events associated with the difference in cuff SBP from invasive SBP. Probabilities were based on Framingham CVD risk equations, with SBP as a continuous variable for coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction or coronary death) [9], stroke [10], atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure [11,12]. Equations assumed that participants were free from previous CVD, valve disease, or ventricular hypertrophy at baseline. In addition to age, sex and SBP, Framingham CVD risk equations required adding some combination of the following variables: total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, BMI, heart rate, use of antihypertensive medications, smoking status, diabetes status, ECG P-R interval, history of previous coronary heart disease, left ventricular hypertrophy or valve disease. In the event of missing continuous variables (cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, BMI, heart rate, P-R interval) [13–16] data were imputed for individual participants by random selection from assumed population-level normal distributions (Table 1). Assuming normal distributions, the mean and standard deviations could be calculated based on median and quartiles of the standard normal [17]. Data in mmol/l (e.g. total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol) were converted to mg/dl (1 mmol/l = 38.67 mg/dl). Similarly, missing categorical variables (smoking status, history of diabetes, use of BP medications) were imputed based on random selection from population-level prevalence data (Table 1) [18–20]. Simulation models were run 1000 times (random walks) over one cycle of one year (Fig. 1). Framingham risk scores were adjusted to a one-year horizon for the projection of outcomes, because this study was conducted using cross-sectional data and without changes in medical interventions or clinical status. This approach was more realistic than long-term risk estimates (e.g. over 10 years), as it did not seek to attribute assumptions on changing risk variables over time. BP classification thresholds were defined based on invasive SBP only, according to the 2018 European hypertension guidelines [21], as optimal (SBP <120 mmHg), normal (SBP 120–129 mmHg), high normal (SBP 130–139 mmHg), hypertension grade I (SBP 140–159 mmHg), hypertension grade II (SBP 160–179), and hypertension grade III (SBP ≥180 mmHg). Within each BP guideline category, four groups were analysed according to the absolute difference in the level of underestimation or overestimation of invasive SBP from cuff SBP: 0–4 mmHg difference; 5–9 mmHg difference; 10–14 mmHg difference; and at least 15 mmHg difference.

Table 1. Simulation model inputs for cardiovascular outcomes and costs.

| Data | Distribution | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk variables | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) [mean (SD)] | 218.1 (46.40) | Normal | Adapted from Beekman et al. [13] | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) [mean (SD)] | 56.5 (15.86) | Normal | Adapted from Beekman et al. [13] | |

| BMI [mean (SD)] | 27.8 (2.03) | Normal | Adapted from Flegal et al. [14] | |

| Heart rate beats per minute [mean (SD)] | 65.9 (9.70) | Normal | From Moser ef.a/. [15] | |

| P-R interval milliseconds [mean (SD)] | 169.0 (10.40) | Normal | Adapted from Magnani et al. [16] | |

| Smoking prevalence (%) | 14 | Table distribution | From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18] | |

| Diabetes prevalence (%) | 6 | Table distribution | From Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [19] | |

| Use of BP medications (%) | 24 | Table distribution | From Beaney et al. [25] | |

| Costs | ||||

| Mean cost of myocardial infarction | $24 695 | Triangular | From Nicholson et al. [22] | |

| Mean cost of ischemic stroke | $18 543 | LogNormal | From Nicholson et al. [22] | |

| Mean cost of heart failure | $12 383 | LogNormal | From Nicholson et al. [22] | |

| Mean cost of atrial fibrillation | $6692 | Normal | From Dell’Orfano et al. [26] | |

Costs are expressed in USD and represent the cost of treatment of acute events in the United States before adjusting for inflation. BP. blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein. SD, standard deviation

Figure 1.

Structure of the simulation model. Shown is the microsimulation model to estimate first cardiovascular events (coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure) and related costs of acute events, of cuff SBP value versus invasive SBP value in adults who were eligible to participate. ‘M’ designates the Markov node with the different branches indicating the health states in one-year time. The black filled circle indicates the chance node after which there is a probability of having a cardiovascular event. The triangles specify the terminal nodes or the end of the pathway within a one-year cycle. There is only one outcome option per participant per cycle. Invasive SBP is the measured intra-arterial aortic SBP. CVD, cardiovascular disease.

The Framingham risk equation for coronary heart disease does not differentiate myocardial infarction from coronary death; therefore, we conservatively costed these events for acute myocardial infarction alone. Costs associated with the acute events of myocardial infarction, stroke, atrial fibrillation and heart failure (Table 1) [22,23] were synthesized from published literature and posteriorly adjusted for inflation to June 2019 values in US dollars, using the Consumer Price Index [24].

Statistics

Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), and nonnormally distributed data as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as proportions. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Study participants

There were 1715 participants with data for cuff SBP, invasive SBP, sex and age. Of those, 37 had the same cuff SBP and invasive SBP or were younger than 30 years of age and were excluded, leaving data from 1678 individuals available for analysis. The clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 2. Individuals were middle-to-older aged, mostly male, and overweight on average. Details on the extent of data missing for other variables are provided in Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/C230. Over a quarter of participants (27%) had optimal BP (invasive SBP <120 mmHg, n = 450) and 43% of participants had SBP in the hypertension range according to guidelines (hypertension I: n = 406, hypertension II: n = 220, and hypertension III: n = 96).

Table 2. Characteristics of study participants according to cuff SBP underestimation or overestimation of invasive aortic SBP.

| All (n = 1678) | Underestimation by cuff SBP (n = 901) | Overestimation by cuff SBP (n = 777) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 (12) | 65 [57,74] | 61 (12) |

| Male sex [n (%)] | 1144 (68) | 562 (62) | 582 (75) |

| Invasive SBP (mmHg | 137(26) | 147 (24) | 125 (22) |

| Cuff SBP (mmHg | 136(22) | 136 (22) | 136(22) |

| Heart rate (bpm | 68 (12) | 68 (12) | 69 (13) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 (5.4) | 26.2(5.1) | 27.4 (5.6) |

| BP-lowering medications (%) | 89 | 91 | 87 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.6 [3.8–5 4] | 4.6 [3.8–5.4] | 4.6 [3.8–5 3] |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.2 [1.0–1.5] | 1.2 [1.0–1.5] | 1.1 [0.9–1.3] |

| Diabetes (%) | 32 | 30 | 34 |

Data reported as n (%). mean (SD) or median [IQR]. Complete data were available for age. sex and BP variables; details on the extent of data missing for other variables is provided in Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/C230.

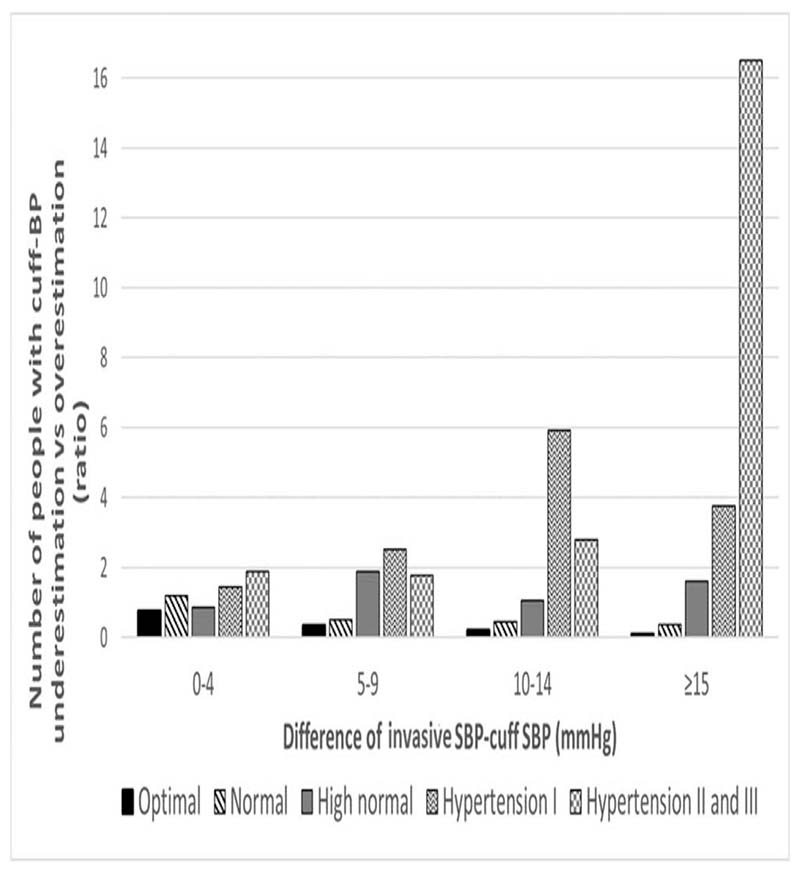

Underestimation and overestimation of SBP and its impact on expected cardiovascular disease events

The proportion of people with cuff SBP underestimation versus overestimation increased progressively as the SBP increased, reaching the maximum ratio of people with cuff SBP underestimation versus cuff SBP overestimation of 16 : 1 in people with hypertension grade II and III (Fig. 2). Overall, the prevalence of SBP underestimation and overestimation by cuff was 54% (n = 901) and 46% (n = 777), respectively.

Figure 2.

Ratio of the number of people with cuff underestimation versus overestimation across BP classification thresholds (based on invasive aortic SBP). The ratio underestimation versus overestimation was calculated as the number of people with underestimation of BP by cuff SBP as numerator and the number of people with overestimation of SBP by cuff SBP as the denominator. The level of underestimation or overestimation was calculated as the absolute difference between invasive SBP and cuff SBP. BP, blood pressure. Definitions: underestimation: invasive SBP > cuff SBP; overestimation: invasive SBP < cuff SBP; optimal SBP: invasive SBP < 120 mmHg; Normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg; high normal SBP: invasive -SBP ≥130 mmHg and <140 mmHg; hypertension I: invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg; hypertension II: invasive SBP ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg; hypertension III: invasive SBP ≥180 mmHg.

Table 3 shows the differences in the total number of CVD events according to underestimation and overestimation of cuff SBP compared with invasive SBP, per 1000 patients in each of the SBP categories and within different levels of cuff SBP underestimation or overestimation. The number of total CVD events increased concomitantly with the SBP level, and the magnitude of difference between the CVD events based on cuff SBP and invasive SBP widened in both underestimation and overestimation of SBP.

Table 3. Differences in the total number of cardiovascular events according to underestimation and overestimation of cuff SBP compared with invasive SBP.

| Underestimation | Overestimation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Events/1000 patients | n | Events/1000 patients | ||||||||||

| Category of BP control based on invasive SBP | Level of difference between cuff and invasive SBP (mmHg) | Invasive SBP | Cuff SBP | Difference | Invasive SBP | Cuff SBP | Difference | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| Optimal <120 mmHg | 0–4 | 56 | 19.9 | 4.3 | 19.5 | 42 | 0.5 | 74 | 19.9 | 4.5 | 204 | 4.6 | 0.5 |

| 5–9 | 31 | 15.6 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 92 | 20.1 | 4.5 | 21.6 | 4.6 | 1.5 | |

| 10–14 | 16 | 18.8 | 4.3 | 16.5 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 77 | 17.9 | 42 | 20.2 | 4.5 | 2.4 | |

| ≥15 | 9 | 19.0 | 4.5 | 15.8 | 4.1 | 32 | 95 | 18.6 | 4.3 | 23.6 | 4.8 | 5.0 | |

| Normal 120–129 mmHg | 0–4 | 52 | 263 | 5.1 | 25.6 | 5.0 | 0.7 | 44 | 22.0 | 4.9 | 225 | 4.9 | 0.5 |

| 5–9 | 24 | 281 | 5 2 | 260 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 49 | 26.6 | 5.0 | 28.4 | 52 | 1.8 | |

| 10–14 | 13 | 34.5 | 5.7 | 308 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 29 | 21.1 | 4.5 | 23.8 | 4.8 | 2.7 | |

| ≥15 | 12 | 16.9 | 4.1 | 13.5 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 33 | 25.4 | 4.9 | 320 | 5.5 | 6.6 | |

| High normal 130–139 mmHg | 0–4 | 35 | 24.7 | 4.9 | 24.1 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 41 | 32.1 | 5.6 | 32.8 | 5.6 | 0.7 |

| 5–9 | 51 | 26.3 | 52 | 24.6 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 27 | 322 | 5.6 | 34.6 | 5.8 | 2.4 | |

| 10–14 | 25 | 32.2 | 5.6 | 28.5 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 24 | 29.8 | 5.5 | 333 | 5.7 | 3.5 | |

| ≥15 | 29 | 24.5 | 4.9 | 19.7 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 18 | 27 2 | 52 | 32.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | |

| Hypertension grade 1140–159 mmHg | 0–4 | 63 | 39.2 | 6.1 | 38.3 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 44 | 36.3 | 6.1 | 37.0 | 62 | 0.7 |

| 5–9 | 78 | 36.7 | 6.1 | 34.3 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 31 | 37.8 | 6.1 | 40.4 | 6.3 | 2.6 | |

| 10–14 | 77 | 35.9 | 6.1 | 31.9 | 5.6 | 4.1 | 13 | 30.4 | 5.4 | 345 | 5.6 | 4.1 | |

| ≥15 | 79 | 38.8 | 6.2 | 31.7 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 21 | 37.7 | 6.0 | 47.0 | 6.5 | 9.3 | |

| Hypertension grades II and III ≥160 mmHg | 0–4 | 45 | 53.3 | 6.9 | 52.0 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 24 | 51.0 | 6.9 | 52.2 | 7.0 | 12 |

| 5–9 | 32 | 48.4 | 6.5 | 45.1 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 18 | 46.5 | 6.7 | 49.5 | 6.9 | 2.9 | |

| 10–14 | 42 | 59.3 | 7.7 | 52.3 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 15 | 50.7 | 6.9 | 56.7 | 7.4 | 6.0 | |

| ≥15 | 132 | 50.5 | 6.9 | 38.7 | 6.1 | 11.8 | 8 | 65.7 | 7.8 | 809 | 8.6 | 15.2 | |

Column n shows the number of people in each category for which 1000 simulations were applied to each participant The difference in the number of events was calculated as the number of total cardiovascular events with invasive SBP minus the amount of total cardiovascular events with cuff SBP The level of underestimation or overestimation was calculated as the absolute difference between invasive SBP and cuff SBP Definitions: underestimation: invasive SBP > cuff SBP: overestimation invasive SEP < cuff SBP. optimal SBP: invasive SBP < 120 mmHg: normal SBP mvasrve SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg: high normal SBP: invasrve SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and <140 mmHg: hypertension I: invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg: hypertension II: invasne SBP ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg: Hypertension III: invasive SBP ≥180 mmHg. SD. standard deviation

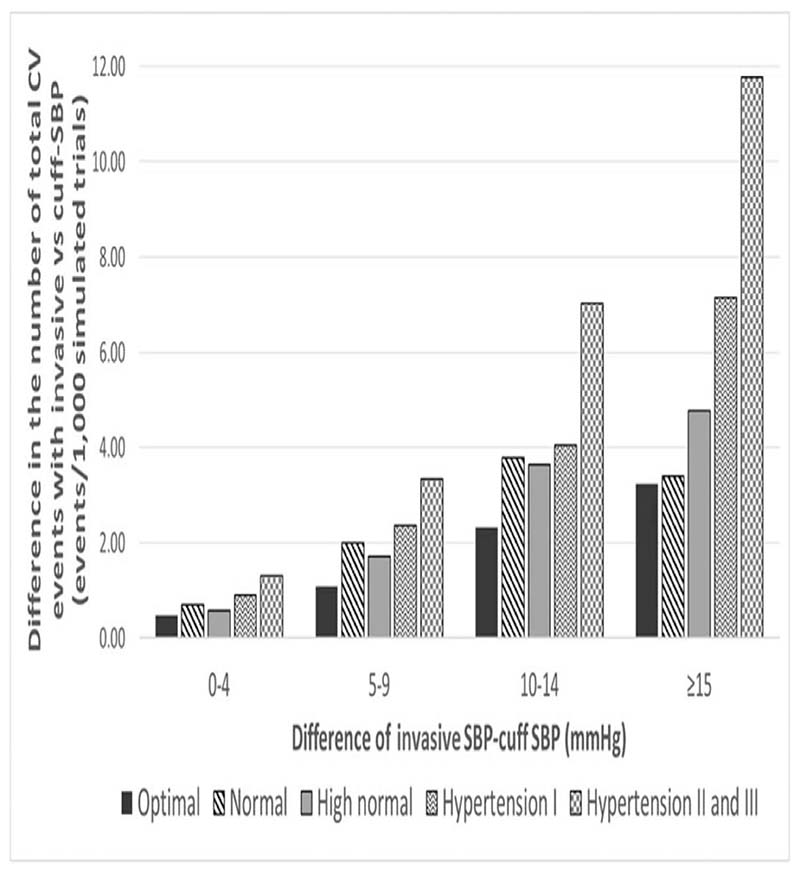

Figure 3 shows the difference in the number of total CVD events per 1000 patients who are potentially missed because of SBP underestimation by cuff SBP. The number of CVD events likely missed by cuff SBP increased stepwise as the level of cuff SBP underestimation, and as the category of BP control increased. The number of preventable CVD events possibly missed because of underestimation by cuff SBP reached a maximum of 11.8 events per 1000 patients in people with hypertension grade II and III and with underestimation at least 15 mmHg.

Figure 3.

Number of potentially preventable total cardiovascular disease events missed because of cuff SBP underestimation. The difference in the number of total CVD events was calculated as the number of total CVD events with invasive SBP minus the number of CVD events with cuff SBP. The absolute difference between cuff SBP and invasive SBP was calculated as invasive SBP minus cuff SBP. CVD, cardiovascular disease. Definitions: underestimation: cuff SBP < invasive SBP; Optimal SBP: invasive SBP < 120 mmHg; Normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg; High normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥130 mmHg and <140 mmHg; hypertension I: invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg; Hypertension II: invasive SBP ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg; Hypertension III: invasive SBP ≥180 mmHg.

Costs of cardiovascular disease events due to underestimation and overestimation of cuff SBP

The related costs of CVD events due to underestimation and overestimation of cuff SBP are shown in Table 4. These differences in the number of total CVD events between cuff SBP and invasive SBP show a projected cost, on average, around $10 300 US dollars per 1000 patients in people with optimal SBP with a small difference between cuff SBP and invasive SBP of 0 and 4 mmHg. This difference in costs because of underestimation increased to just over $241 000 US dollars per 1000 patients in people with hypertension II and III and cuff SBP underestimation of invasive SBP of more than 15 mmHg (Fig. 4).

Table 4. Costs of total cardiovascular events with invasive SBP and cuff SBP in underestimation and overestimation of SBP.

| Underestimation | Overestimation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (USO) per 1.000 patients | Cost (USD) per 1.000 patients | ||||||||||

| Category of BP control based on invasive SBP | Level of difference between cuff and invasive SBP (mmHg) | Invasive SBP | Cuff SBP | Invasive SBP | Cuff SBP | ||||||

| Mean | SO | Mean | SD | Difference | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Difference | ||

| Optimal <120 mmHg | 0–4 | 379186.40 | 89 818.30 | 368843.20 | 88 801.00 | 10 343 20 | 384 49590 | 94 256.10 | 395 050.80 | 96274.80 | 10 555.00 |

| 5–9 | 300161.70 | 8290740 | 276 452 60 | 80576.00 | 23 709 10 | 385 816.90 | 93 032.60 | 417864.60 | 95 635.60 | 32 017.80 | |

| 10–14 | 348644.80 | 8967440 | 299411.90 | 80 371.60 | 49 232.90 | 337 730.40 | 85 715.80 | 387937.10 | 9368930 | 50 206.70 | |

| ≥15 | 353 237 30 | 91 680.10 | 286 719.70 | 81919.70 | 66 517.70 | 358 449.10 | 90 653.20 | 463 847.40 | 102 923 60 | 105 398 30 | |

| Normal 120–129 mmHg | 0–4 | 509 355 00 | 108 354 60 | 494 231 70 | 10681980 | 15 123 20 | 428 886 80 | 101 947.10 | 438 905.90 | 102 366 50 | 1001910 |

| 5–9 | 536 813.30 | 110102.30 | 495026.60 | 105 158.30 | 41 786.70 | 508 114.50 | 106 030.40 | 545 760.00 | 108988.20 | 37 645 50 | |

| 10–14 | 667 901.80 | 121187.50 | 590 540.70 | 11252420 | 77 361.10 | 405 022.10 | 98 660.50 | 463 177.60 | 103 902.30 | 58 155.60 | |

| ≥15 | 321 558 90 | 85040.40 | 249 574.00 | 7481590 | 71 984.90 | 498 867.40 | 106 814.00 | 638 292.00 | 117415.90 | 139 424.60 | |

| rtgh normal 130–139 mmHg | 0–4 | 478 550.00 | 101482 40 | 466 167.90 | 100309.10 | 12 382.10 | 628 333.30 | 119246.40 | 611 866.50 | 119 857 60 | 13 533 20 |

| 5–9 | 51271680 | 110200.60 | 477384.70 | 106 557.00 | 35 332.10 | 618 593 60 | 115 576.80 | 668 093.00 | 120 503.10 | 49 499 40 | |

| 10–14 | 619034.90 | 118 599.20 | 546 036 10 | 109 753.10 | 72 998.80 | 587 351.90 | 117 850.10 | 660 812.80 | 120 296.90 | 73 457.80 | |

| ≥15 | 474 758.30 | 104 841.00 | 376 078.00 | 92 870.50 | 98 680 30 | 521 675.50 | 109251.60 | 610 025.40 | 121094.40 | 11835000 | |

| Hypertension grade 1140–159 mmHg | 0–4 | 764 996 50 | 130 834 90 | 74613570 | 12851340 | 18 860.90 | 712 351.50 | 129271.50 | 72762450 | 130 768.60 | 1527290 |

| 5–9 | 711522.20 | 129 881.00 | 661 90310 | 125 217.10 | 49619.10 | 737 63150 | 130 330.70 | 790 144 60 | 134726 70 | 52510.10 | |

| 10–14 | 695 765 80 | 130 171.00 | 612 188 80 | 120 59940 | 83 577.00 | 590 0M.00 | 115810.10 | 677 914.30 | 121899.40 | 87910.30 | |

| ≥15 | 757 466.90 | 132 312.90 | 609 488 80 | 11795920 | 147978.20 | 734 107.40 | 129559.00 | 924 700.00 | 140 94420 | 190 592.60 | |

| Hypertension grades II and III 2160 mmHg | 0–4 | 1 041 069.00 | 150 999 60 | 1014 245.50 | 148 851.40 | 26 823 50 | 1 015907.80 | 147369.10 | 1 040 629.50 | 149 055.60 | 24 721 60 |

| 5–9 | 95347300 | 136 247.20 | 882 672 30 | 130 660 30 | 70 800.70 | 915 427.30 | 142 032.00 | 976 302.60 | 145 080.10 | 60 87540 | |

| 10–14 | 1161315.00 | 162 251.40 | 1017 475.00 | 150226.00 | 143810.10 | 99477220 | U7 530.30 | 1 11775450 | 157 562.70 | 122 982.30 | |

| ≥15 | 991 034.20 | 143351.30 | 749 707.00 | 125 845.30 | 24132720 | 1 255128.50 | 162 164.50 | 1570 092.90 | 182434.50 | 314 9644 | |

The level of underestimation or overestimation vras calculated as the absolute difference between invasive SBP and erf SBP. The difference in costs of events was calculated as the costs of total caniovascular events with imasrre SBP minus the costs of total cardiovascular events with cuff SBP for the underestimation group, and as the costs of total cardiovascular events with cuff SBP rrwus the costs of total cartficnascular events vwth invasive S6P for the overestimation group Costs are expressed in USD and represent the cost of treatment of acute events in the United States. Definitions: underestimation: invasive SBP > cuff SBP: overestimation: invasive SBP < cuff SBP: opbmal SBP invasive SBP < 120 mmHg: normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg: high normal SBP invasive SBP ≥130 mmHg and <140 mmHg: hypertension I invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg: hypertension II invasive SBP ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg: hypertension III invasive SBP ≥180 mmHg.

Figure 4.

Costs (in USD) of the potentially preventable cardiovascular events missed because of cuff SBP underestimation. The difference in costs (per thousand USD) was calculated as the cost of total CVD events with invasive SBP minus the cost of total CVD events with cuff SBP. The absolute difference between cuff SBP and invasive SBP was calculated as invasive SBP minus cuff SBP. CVD, cardiovascular disease. Definitions: underestimation: invasive SBP > cuff SBP; optimal SBP: invasive SBP <120 mmHg; normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg; High normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥130 mmHg and <140 mmHg; hypertension I: invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg; hypertension II: invasive SBP ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg; hypertension III: invasive SBP ≥180 mmHg.

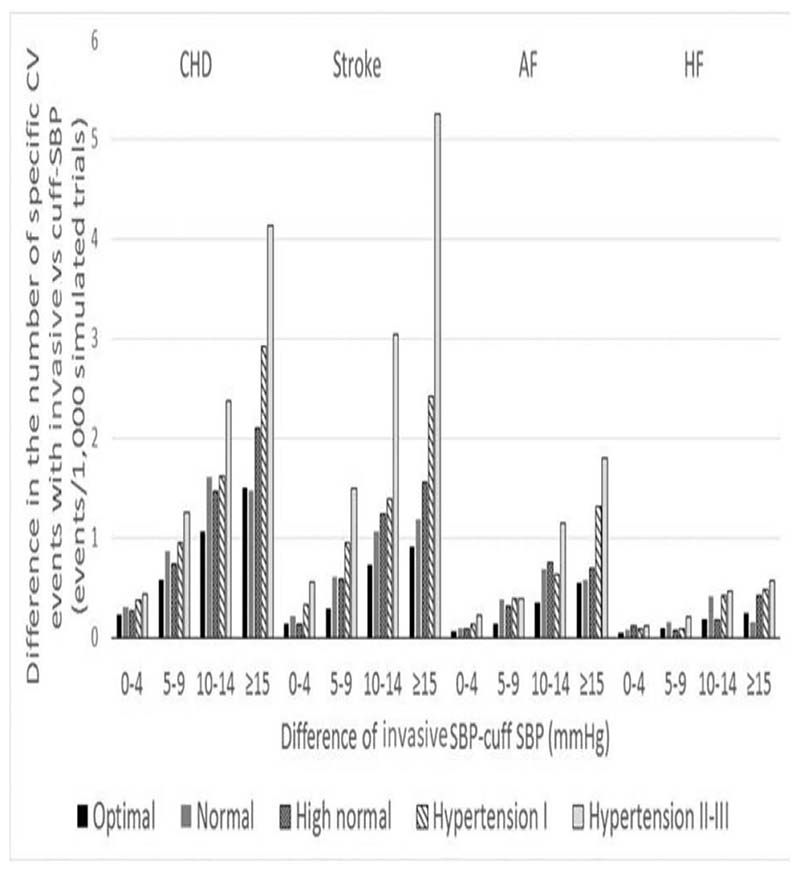

When coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction or coronary death), stroke, atrial fibrillation and heart failure were examined separately in people with underestimation of SBP, we found a positive trend between greater cuff underestimation, level of SBP and possible CVD events missed by cuff SBP (Fig. 5). Stroke, followed by coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction or coronary death), were the events that would be most missed in people with higher grades of hypertension and greater cuff SBP underestimation of invasive SBP.

Figure 5.

Number of potentially preventable specific cardiovascular disease events missed because of cuff SBP underestimation. The difference in the number of specific CVD events was calculated as the number of specific CVD events with invasive SBP minus the number of specific CVD events with cuff SBP. The absolute difference between cuff SBP and invasive SBP was calculated as invasive SBP minus cuff SBP. AF: atrial fibrillation; CHD: coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF: heart failure. Definitions: underestimation: invasive SBP > cuff SBP; optimal SBP: invasive SBP < 120 mmHg; normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥120 mmHg and <130 mmHg; high normal SBP: invasive SBP ≥130 mmHg and <140 mmHg; hypertension I: invasive SBP ≥140 mmHg and <160 mmHg; Hypertension II: invasive SBP ≥ 60 mmHg and <180 mmHg; hypertension III: invasive SBP ≥ 180 mmHg.

Discussion

This study determined the potential CVD outcomes and cost impacts of differences between cuff SBP and invasive SBP. Estimates of the effects of differences between cuff SBP and invasive SBP were modelled in a large sample of participants. The main findings were that the most significant potential influence on CVD events and health costs was related to cuff SBP underestimation. This was most pronounced among people with the highest SBP (hypertension grades II and III) and where the level of cuff underestimation was at least 15 mmHg. For these people, there was the highest number of CVD events and highest health-related costs projected to occur from a failure to recognize high SBP because of cuff SBP underestimation. This modelling study shows that improving cuff BP measurement methods should reduce preventable CVD events and associated health costs.

High BP is estimated to account for 10% of global healthcare spending, and with a particular economic burden in developing countries [27]. The control of high BP is recognized by WHO as a ‘Best Buy’ intervention in the management of CVD, where an investment of $1 USD will return more than $3 USD in terms of healthy life-years gained, deaths and incident cases averted [28]. To appropriately diagnose high BP and initiate correct clinical care pathways, the accurate measurement of BP is a crucial step. Efforts to achieve this have concentrated on ensuring that BP measurement techniques are standardized [29], and it is well appreciated that more reliable diagnosis of hypertension (such as with home BP or 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring compared with clinic BP) provides better quantification of risk and is more cost-effective [30–32].

The accuracy of cuff BP devices is recognized as playing a pivotal role in the reliability of hypertension diagnosis, but unfortunately the majority of automated cuff BP devices have not undergone rigorous accuracy testing [33–38]. To our knowledge, this current analysis is the first to determine the potential health outcomes and cost implications of cuff SBP by comparison to invasive aortic SBP. The findings are not unexpected because there is a continuous relationship between SBP and CVD events [39], thus the higher the level of difference between cuff SBP and invasive SBP, the greater the probability of adverse CVD events and associated health costs. Our previous analysis from the INSPECT consortium showed that the highest chances for different BP classification using cuff SBP (compared with invasive SBP) were in the SBP range from 120 to 160 mmHg [5]. We extend on this observation by showing that the most important aspect of cuff SBP underestimation occurs amongst the higher-end BP range because this increases chances for potentially missing opportunities to recognize and intervene on high BP to reduce CVD events. On the other hand, in the higher end invasive BP range, even if cuff BP was substantially underestimated, the cuff SBP value could still be within the hypertensive range, thus, treatment may still be initiated. Nonetheless, if cuff BP were more accurate across all BP levels, it would assist towards achieving correct targeted treatment to thresholds. The mechanisms of cuff underestimation and overestimation are not fully understood but are likely to be influenced by inadequate algorithms used by automated devices to estimate BP. These algorithms do not account for changes in arterial structure and hemodynamic characteristics that can occur at the site of cuff BP measurement associated with various factors, including ageing and vascular disease.

High BP is the world's leading preventable risk factor for cardiovascular death and disability [2,40]. In lieu of this, the reporting of this study focused on the effects of underestimation of SBP as opposed to overestimation, considering the relative importance to preventable CVD events. The greatest impact of cuff inaccuracy was demonstrated for cuff underestimation, but this does not discount the importance of overestimation in the appropriate treatment of high BP. Antihypertensive treatment based on falsely elevated BP values can lead to overtreatment, which especially in the elderly may lead to complications or an increase in side effects [41,42], with the associated costs. For this study, the extent and effect of overtreatment on the CVD events in the overestimation group could not be quantified because of limited data. Additionally, the model was unable to predict beyond the endpoints of the CVD events, more specifically the outcomes of the events (mortality/survival). Having this data would provide more insight into the true effects of overestimation and underestimation. This will be the focus of future research.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, data were analysed from within a consortium of several studies in which cuff SBP was recorded among people undergoing coronary angiographic procedures. Although this design helps provide an indication on the level of cuff SBP underestimation and overestimation, modelling assumed that all participants were free from CVD (as required for using the Framingham equation), and this was not likely to be the case. Thus, the analysis will in part be extrapolating a primary prevention equation to a secondary prevention population, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations with different clinical characteristics. Similarly, diversity among the quality of methods to record invasive SBP may have influenced the level of cuff SBP underestimation and overestimation. Having said this, rigorous quality control methods were employed for the inclusion of studies into the INSPECT consortium, and previous sensitivity analysis conducted on issues related to study design and data quality (e.g. fluid-filled versus solid-state catheters) did not alter findings [5,7,43]. CVD risk projections and costs were modelled over one-year instead of the 10-year time horizon of the Framingham equations. This approach was chosen in favour of attributing assumptions on changing risk variables over time, which could have led to a different risk and cost projections. This study focussed on SBP rather than DBP, because SBP is commonly used in risk equations and is subject to greater differences from invasive measures (more inaccuracy) compared with DBP. However, this focus on SBP means that the study findings do not apply to people with diastolic hypertension. Finally, this is a theoretical study in which some missing values were imputed (e.g. BP-lowering medications) and the cuff BP and invasive BP were not measured in the same ways that were used to develop the Framingham risk score.

This study found that potentially preventable CVD events may be missed, and major increases in health costs – not only mostly from cuff SBP underestimation of invasive SBP at higher SBPs but also from cuff SBP overestimation. The adverse outcomes associated with cuff SBP underestimation and overestimation could be remedied with improvements in the precision of methods to measure cuff SBP, and this is an area of future research need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Additional members of the INSPECT consortium include: Esben Laugesen, Department of Endocrinology and Internal Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; Niklas B. Rossen, Department of Endocrinology and Internal Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; Manish D. Sinha, Cardiology Department, Guy's and St. Thomas’ Hospitals, London, United Kingdom.

Funding

this work is supported by Royal Hobart Hospital Research Foundation grants (references 19-202 and 21-006) and was supported by a Vanguard Grant from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (reference 101836). D.S.P. is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (reference 104774) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. M.G.S. is supported by a Future Leadership Fellowship (reference 102553) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Tokushima, Japan. Microlife Co., Ltd., and National Yang-Ming University have signed a contract for transfer of the noninvasive central blood pressure technique. The contract of technology transfer includes research funding for conducting the validation study. C.H.C. has served as a speaker or a member of a speaker's bureau for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bayer AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Servier, Merck & Co., Sanofi and Takeda Pharmaceuticals International. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 201. Lancet. 2017;390:1345–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booth J. A short history of blood pressure measurement. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70:793–799. doi: 10.1177/003591577707001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Peng X, Black JA, Dwyer N, Roberts-Thomson P, et al. Discovery of new blood pressure phenotypes and relation to accuracy of cuff devices used in daily clinical practice. Hypertension. 2018;71:1239–1247. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Otahal P, Aakhus S, Al-Jumaily AM, Black JA, et al. Accuracy of cuff-measured blood pressure: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DW, Appel LJ, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ, Lenfant C. Measuring blood pressure accurately: new and persistent challenges. JAMA. 2003;289:1027–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Otahal P, Black JA, Bos WJ, Chen CH, et al. Invasive Blood Pressure Consortium. Influence of age on upper arm cuff blood pressure measurement. Hypertension. 2020;75:844–850. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.TreeAge Pro 2019. Williamstown, MA: TreeAge Software; Available at http://www.treeage.com . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Framingham Heart Study. Hard Coronary Heart Disease (10-year risk) [Accessed 20 November 2018]. Available at: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/hard-coronary-heart-disease-10-year-risk/

- 10.Framingham Heart Study. Stroke. [Accessed 20 November 2018]. Available at: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/stroke/

- 11.Framingham Heart Study. Framingham Heart Study AF score (10-year risk) [Accessed 20 November 2018]. Available at: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/atrial-fibrillation-10-year-risk/

- 12.Framingham Heart Study. Congestive Heart Failure. [Accessed 20 November 2018]. https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/congestive-heart-failure/

- 13.Beekman M, Heijmans BT, Martin NG, Whitfield JB, Pedersen NL, DeFaire U, et al. Evidence for a QTL on chromosome 19 influencing LDL cholesterol levels in the general population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:845–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moser M, Lehofer M, Sedminek A, Lux M, Zapotoczky HG, Kenner T, Noordergraaf A. Heart rate variability as a prognostic tool in cardiology. A contribution to the problem from a theoretical point of view. Circulation. 1994;90:1078–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnani JW, Wang N, Nelson KP, Connelly S, Deo R, Rodondi N, et al. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Electrocardiographic PR interval and adverse outcomes in older adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:84–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.975342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. [Accessed 28 February 2019]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm .

- 19.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Diabetes snapsho–t, How many Australians have diabetes? – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. [Accessed 1 March 2019]. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes-snapshot/formats .

- 20.Beaney T, Schutte AE, Tomaszewski M, Ariti C, Burrell LM, Castillo RR, et al. MMM Investigators. May Measurement Month 2017: an analysis of blood pressure screening results worldwide. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e736–e743. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson G, Gandra SR, Halbert RJ, Richhariya A, Nordyke RJ. Patient-level costs of major cardiovascular conditions: a review of the international literature. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:495–506. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S89331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dell’Orfano JT, Patel H, Wolbrette DL, Luck JC, Naccarelli GV. Acute treatment of atrial fibrillation: spontaneous conversion rates and cost of care. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:788–790.:A710. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00993-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyatake N, Matsumoto S, Nishikawa H, Numata T. Relationship between body composition changes and the blood pressure response to exercise test in overweight Japanese subjects. Acta Med Okayama. 2007;61:1–7. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaney T, Schutte AE, Tomaszewski M, Ariti C, Burrell LM, Castillo RR, et al. May Measurement Month 2017: an analysis of blood pressure screening results worldwide. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e736–e743. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dell’Orfano JT, Patel H, Wolbrette DL, Luck JC, Naccarelli GV. Acute treatment of atrial fibrillation: spontaneous conversion rates and cost of care. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:788–790. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00993-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Weinstein MC. International Society of Hypertension. The global cost of nonoptimal blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1472–1477. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832a9ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saving lives, spending less: a strategic response to noncommunicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. (WHO/NMH/NVI/18.8). Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Head GA, McGrath BP, Mihailidou AS, Nelson MR, Schlaich MP, Stowasser M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in Australia: 2011 consensus position statement. J Hypertens. 2012;30:253–266. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834de621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierdomenico SD, Mezzetti A, Lapenna D, Guglielmi MD, Mancini M, Salvatore L, et al. ‘White-coat’ hypertension in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension: evaluation of prevalence by ambulatory monitoring and impact on cost of healthcare. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:692–697. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arrieta A, Woods JR, Qiao N, Jay SJ. Cost-benefit analysis of home blood pressure monitoring in hypertension diagnosis and treatment: an insurer perspective. Hypertension. 2014;64:891–896. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharman JE, Ordunez P, Brady T, Parati G, Stergiou GS, Whelton PK, et al. The urgency to regulate validation of automated blood pressure measuring devices: a policy statement and call to action from the World Hypertension League. J Hum Hypertens. 2022;37:155–159. doi: 10.1038/s41371-022-00747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell NR, Gelfer M, Stergiou GS, Alpert BS, Myers MG, Rakotz MK, et al. A call to regulate manufacture and marketing of blood pressure devices and cuffs: a position statement from the World Hypertension League, International Society of Hypertension and Supporting Hypertension Organizations. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18:378–380. doi: 10.1111/jch.12782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharman JE, O’Brien E, Alpert B, Schutte AE, Delles C, Hecht Olsen M, et al. Lancet Commission on Hypertension Group. Lancet Commission on Hypertension group position statement on the global improvement of accuracy standards for devices that measure blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2020;38:21–29. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alpert BS. Can ’FDA-cleared’ blood pressure devices be trusted? A call to action. Blood Press Monit. 2017;22:179–181. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharman JE, Padwal R, Campbell NRC. Global marketing and sale of accurate cuff blood pressure measurement devices. Circulation. 2020;142:321–323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picone DS, Campbell NRC, Schutte AE, Olsen MH, Ordunez P, Whelton PK, Sharman JE. Validation status of blood pressure measuring devices sold globally. JAMA. 2022;327:680–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Law MR, Elliott P, MacMahon S, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and the global burden of disease 2000. Part II: estimates of attributable burden. J Hypertens. 2006;24:423–430. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000209973.67746.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kowalski C, Yang K, Charron T, Doucet M, Hatem R, Kouz R, et al. Inaccuracy of brachial blood pressure and its potential impact on treatment and aortic blood pressure estimation. J Hypertens. 2021;39:2370–2378. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kouame N, Cleroux J, Lefebvre J, Ellison R, Lacourciere Y. Incidence of overestimation and underestimation of hypertension in a large sample of Canadians with mild-to-moderate hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Armstrong MK, Black JA, Bos WJW, Chen CH, et al. Invasive Blood Pressure Consortium. Identifying isolated systolic hypertension from upper-arm cuff blood pressure compared with invasive measurements. Hypertension. 2021;77:632–639. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.