Abstract

The skin contains a population of tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm) that is thought to contribute to local tissue homeostasis and protection against environmental injuries. Although information about the regulation, survival program, and pathophysiological roles of Trm has been obtained from murine studies, little is known about the biology of human cutaneous Trm. Here, we showed that host-derived CD69+ αβ memory T cell clones in the epidermis and dermis remain stable and functionally competent for at least 10 years in patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed low expression of genes encoding tissue egress molecules by long-term persisting Trm in the skin, whereas tissue retention molecules and stem cell markers were displayed by Trm. The transcription factor RUNX3 and the surface molecule Galectin-3 were preferentially expressed by host T cells on the RNA and protein levels, suggesting two novel markers for human skin Trm. Furthermore, skin lesions from patients developing graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) showed a large number of cytokine-producing host-derived Trm, suggesting a contribution of these cells to the pathogenesis of GVHD. Together, our studies highlighted the relationship between the local human skin environment and long-term persisting Trm which differs from murine skin. Our results also indicated that local tissue inflammation occurs through host-derived Trm following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Introduction

Tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm) are major contributors to adaptive immunity in human tissues. Trm protect against reinfection with pathogens1–3, but these cells can also contribute to the propagation of (auto-) inflammatory diseases4,5. With 20 billion memory T cells, the skin is one of the largest reservoirs of Trm in the human body6, and the control of skin-resident memory T cells is crucial for the treatment of chronic inflammatory skin conditions, such as psoriasis7–10.

Initially, Trm were identified in various mouse organs using techniques for tracking the infiltration and retention of T cells in vivo11–13. Different experimental approaches have verified tissue residency of T cells, including (i) parabiosis, in which mice are surgically conjoined and Trm can be identified by genetic markers in the two partner mice1,3, (ii) mixed bone-marrow chimeras, in which mice are lethally irradiated and reconstituted with bone-marrow cells from congenitally marked animals14,15, and (iii) in vivo fluorescent antibody labeling to distinguish circulating from tissue-resident immune cells, the latter of which are protected from antibodies that are injected intravenously16,17. These studies revealed that cutaneous Trm are generated upon infection with pathogens and that murine CD8+ T cells reside within the epidermis and CD4+ T cells in the dermis. Currently accepted phenotypic markers for the identification of Trm from circulating T cells include CD69 and CD1034,18,19.

However, studies in humans suggest that mouse data may not accurately reflect what is observed in human tissues. Indeed, the dynamics of human Trm development, retention, and function have been more challenging to assess. Decades-long immunity to common pathogens suggests that T cells may persist or self-renew in human tissues for extended periods of time20. Previous efforts using deuterium labeling to track leukocyte turnover have identified varying life spans for T cells according to phenotype and compartment21,22, and metabolic activity was suggested as a key process regulating T cell senescence and longevity23,24. Short-term skin-resident T cells were found in a human skin engraftment mouse model and in cutaneous T cell lymphoma patients treated with alemtuzumab (anti-CD52), which targets circulating T cells25. Although these studies hint towards the existence of Trm also in human skin, the concept of persistent tissue compartmentalization has been challenged by evidence that cutaneous CD4+ Trm can re-enter the blood stream26. Two studies indicate the persistence of Trm in organ transplant patients for one year and correlate transcriptomic signatures with their function27,28. Bartolomé-Casado et al. provide evidence of CD8+ Trm capable of proliferation that persist in the small intestine27. Snyder et al. show that Trm comprising populations of both CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells are present in the lung and that increase of the Trm population is associated with reduced clinical complications after lung transplantation, indicating longevity of Trm in transplanted organs28.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) after myeloablative conditioning provides an opportunity for studying human Trm biology in vivo, because host and donor-derived immune cell populations can be tracked separately. Therefore, after allo-HSCT, one can ask whether Trm reside in tissues without replenishment from circulating T cells, and, if they do, investigate how the cells achieve long lifespans, for example through cellular senescence or low-level local proliferation. Furthermore, studying such patients facilitates evaluation of the role of Trm in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a common life-threatening complication of allo-HSCT and the major limiting factor in its broad clinical application. Although GVHD has been described as the destruction of recipient tissues by invading donor T cells, release of damage- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS and PAMPS) and cytokines in tissues upon conditioning therapy suggests commencement of an inflammatory response prior to infusion of donor cells 29,30. Whether Trm are involved in this early tissue reaction is unknown.

The movement of T cells in and out of tissues involves the balance between tissue-retention proteins and tissue egress proteins on the T cell surface. Based on studies showing Trm expression of genes encoding retention markers11, we hypothesized that tissue T cells display altered elimination dynamics upon radiochemotherapy compared to their counterparts in blood. Myeloablative radiochemotherapy preceding allo-HSCT provides a situation in which to compare factors leading to differential properties of skin and blood T cells. Here, through an in-depth analysis of blood and skin samples from a large cohort of patients before and after allo-HSCT, we demonstrated that T cells persist for more than 10 years in the skin, whereas their counterparts in peripheral blood display high turnover. Single-cell RNA sequencing uncovered a unique survival program of cutaneous Trm and defined phenotypic markers of these cells. Furthermore, we evaluated the proliferative capacity of Trm and sequenced the genes encoding subunits of the T cell receptor (TCR) in serial tissue samples, providing evidence for the in vivo expansion of Trm clones over time. Finally, we identified a role for host-derived Trm in local inflammation. Their abundance in the skin at the day of transplantation correlated positively with the development of GVHD after transplantation. In addition, high numbers of host-derived proliferating T cells in skin lesions of GVHD indicated an active role of Trm in tissue inflammation. These observations challenge the widely-held paradigm of GVHD pathogenesis, which stipulates exclusively donor cell-derived induction of inflammation and tissue destruction; rather, host-versus-graft (HVG) reactions appear to contribute in triggering (auto-) inflammatory processes resulting in GVHD.

Results

Radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm survive myeloablative conditioning

To understand leukocyte elimination and recovery dynamics in patients receiving allo-HSCT, we tracked peripheral blood and skin immune cells of 28 individuals over the course of one year (fig. S1A). We isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and cells of healthy appearing skin from the upper arm at the following five time points: at baseline before conditioning with a myeloablative radiochemotherapy regimen, at the day of allo-HSCT before infusion of donor peripheral blood stem cells, and in the recovery period on post-transplant days 14, 100, and 365. Although blood leukocytes were robustly (>90%) eliminated by conditioning in all patients, on average ~50% of cutaneous leukocytes were retained with some patients retaining large numbers of these cells (fig. S1B). In line with previous reports on cutaneous macrophages after allo-HSCT 31, many (>40%) of host phagocytes in the skin survived the conditioning regimen (fig. S1C). Abundant host T cells remained in the skin after radiochemotherapy (Fig. 1A). In contrast to T cells from peripheral blood, the mean percentage of cutaneous T cells at the day of transplantation was 60% of that recorded in the skin at baseline (Fig. 1B, p=0.0015) with cells remaining in both the epidermal and dermal compartments (Fig. S1D, E), indicating different responses of T cells from blood and skin to the myeloablative regimen. Peripheral blood monocyte cell numbers recovered to baseline by day 14 after transplantation (fig. S1C), whereas circulating and skin T cells reached baseline numbers by 100 days after transplantation (Fig. 1A).

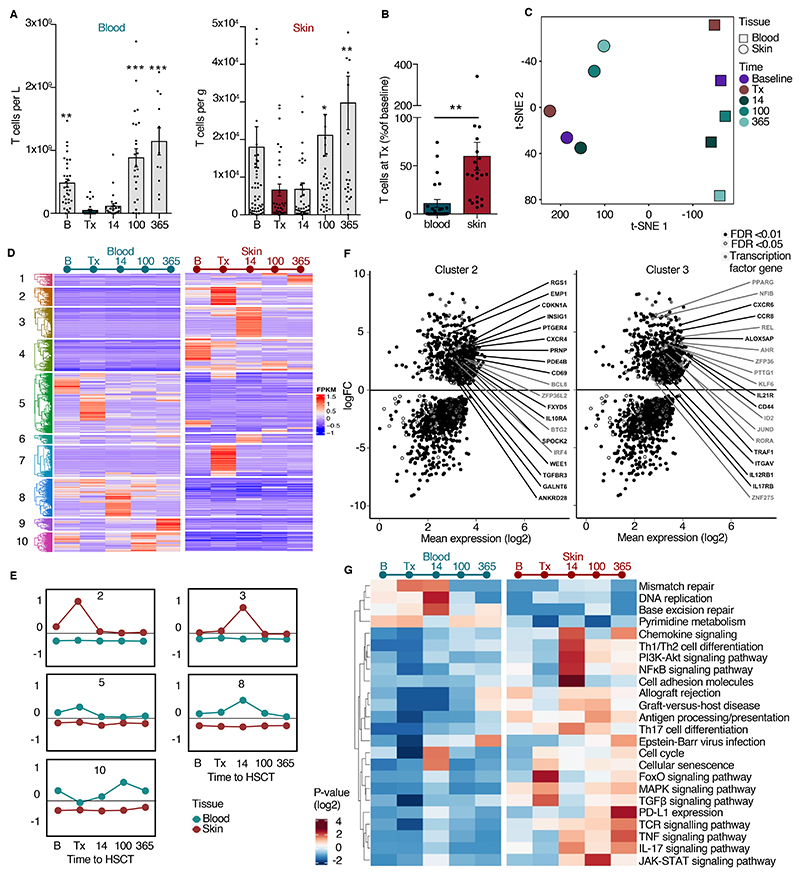

Figure 1. Distinct survival and transcriptional dynamics in T cells of peripheral blood and skin.

(A) T cell numbers in the course of allo-HSCT. Numbers of T cells (CD45+7AAD-CD3+) in peripheral blood and skin before and after allo-HSCT (n = 28) assessed by flow cytometry. B, baseline before radiochemotherapy; Tx, data of transplantation; 14, 100, 365, days after transplantation. (B) T cells surviving radiochemotherapy. Frequency of T cells in blood and skin samples taken on day of transplantation compared to frequency at baseline (n = 21). Data in A and B are shown as mean ± SEM. Each dot corresponds to one patient. Statistical difference to day of transplantation is indicated by asterisk: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA including Tukey’s pairwise comparison (A) and Student’s t-test (B). (C) t-SNE plot of the top 2000 highly upregulated genes (mean log2 expression) among all 11 patients and 5 time points from blood and skin (55 bulk T cell samples). (D) Different transcriptional program in T cells revealed by hierarchical clustering of all 1690 differentially expressed genes from blood versus skin at each time point. Differentially expressed genes were selected as those with an adjusted p < 0.01 and log2 fold change > 2. Coregulated genes grouped into 10 clusters. (E) Time-dependent differentiation score of clusters 2, 3, 5, 8, and 10. Data are shown as average expression of all genes in each cluster for all patients at each time point in blood (turquoise line) and skin (red line). (F) Scatter plots show log fold change (FC) versus log2 mean expression of genes from clusters 2 and 3. Labels indicate representative upregulated genes with FDR < 0.01 (black) or 0.05 (gray). (G) KEGG-pathway enrichment in blood and skin T cells of time-dependent, differentially expressed genes in cluster 2 and cluster 3 from blood versus skin. Data in panels C – G are from transcriptomic analysis of T cells isolated from the skin and blood of 11 patients at the indicated timepoints (100 CD3+ singlets per sample).

Ablation of immune cells by the radiochemotherapy regimen involves the induction of doublestranded DNA breaks and genotoxic stress, which causes the death of rapidly dividing cells, such as those of the immune system. Therefore, we evaluated cellular stress of skin T cells after radiochemotherapy. The percentage of skin T cells displaying dsDNA breaks (γH2AX+ T cells) was not increased by radiochemotherapy (fig. S1F), and transcriptome analysis revealed no significant upregulation of cellular stress genes on the day of transplantation (fig. S1G). These data suggested that most T cells in the skin are resistant to the lethal effects of radiochemotherapy and remain vital.

Distinct transcriptome dynamics in T cells of blood and skin reveal marker genes for resident and circulating T cells

To explore the properties of the T cells surviving radiochemotherapy and residing in the skin and compare them to circulating T cells in blood, we studied skin- and blood-derived T cells, isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) at the transcriptional level using low-input RNA sequencing (55 T cell samples from 11 patients). We analyzed samples taken over the course of one year, as well as preceding and at the time of allo-HSCT (Fig. 1C – G, fig. S1H, I). Principal component analysis revealed that distinct transcriptomes of blood and skin T cells were conserved over time (Fig. 1C, fig. S2A, B), and we observed low inter-donor variability of gene expression (fig. S2C). The changes in average gene expression of peripheral blood-derived T cells of all patients were time dependent. Based on principal component and dendrogram analysis, T cells isolated at the time of transplant from peripheral blood were transcriptionally distinct from baseline T cells, whereas the transcriptomes of skin T cells at the time of transplant and baseline were more closely related (Fig. 1C, fig. S2B), suggesting that resident T cells are less affected by radiochemotherapy.

Differentially expressed gene analysis of peripheral blood T cells at transplant compared with cells at baseline revealed RNA profiles of cells undergoing apoptosis, indicated by an increase in the transcription of genes encoding apoptosis-regulators BAX, RELT, and RPS27L and of EPAS1 (Fig. S2D). EPAS1 is a transcription factor encoded by a gene that is induced as cellular oxygen saturation falls 32.

To elucidate different transcription programs in blood and skin T cells, we performed hierarchical clustering of all 1,690 differentially expressed genes (adjusted p value <0.01 and log2 fold change >2) between blood and skin at baseline, time of transplant, and 14, 100, and 365 days after transplant. Ten clusters with different regulation dynamics in blood and skin T cells were recognized (Fig. 1D). Notably, clusters 5, 8 and 10 were composed of genes that were consistently upregulated in blood T cells compared to skin T cells (Fig. 1E), thus constituting marker genes of circulating T cells. Genes of cluster 5 included those encoding CD69-antagonist S1PR1 and its transcription factor KLF2 33, proteins associated with effector T cells (GZMH, IL15)34,35, and clones of gamma subunits of the TCR. Genes in cluster 8 were slightly upregulated in blood after transplantation and included the genes encoding homing molecule SELL (also known as CD62L)36, zinc finger transcription factor KLF7, and TCR delta clones. Genes of cluster 10 included those encoding proteins associated with cytotoxic T cells (KLRG1, CD160, CXCR3, IL24)37. We detected transcriptional signatures of circulating effector γδ T cells (clusters 5 and 8) and blood cytotoxic T cells (cluster 10) that were efficiently eliminated by radiochemotherapy (Fig.1D, E).

We also identified gene clusters with higher expression in skin at all time points analyzed (Fig. 1E, F). In clusters 3 and 6, we found the classical Trm transcriptome, including genes encoding Trm markers (CCR8, CD44, PPRG, AHR, CXCR6), the fatty acid receptor CD36, and the cytokine receptors IL12R, IL17R, IL21R38–42 (Fig. 1F, right panel). These genes were upregulated in skin on post-transplant day 14, which could indicate an induction of residency marker genes by cells that have recently entered the skin as they acquire a resident phenotype. Cluster 2 included genes that were upregulated in skin and had a higher expression after conditioning, which could represent RNA profiles of radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm. Cluster 2 is composed of genes encoding tissue retention molecules (CD69, CXCR4) 43,44, cellular senescence markers (BTG2, WEE1, CDKN1A) 45,46, and cytokine receptors (IL10RA, TGFBR3) (Fig. 1F, fig. S2E). We performed the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis using the set of differentially regulated genes between blood and skin T cells. This analysis revealed that skin T cells at the time of transplant increased cellular senescence pathways along with MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), FoxO, and TGFβ (transforming growth factor β) signaling pathways (Fig. 1G, fig. S2E). Skin T cells after transplantation (14, 100, 365) upregulated pathways associated with inflammation, such as chemokine signaling, NF-κB signaling, T helper type 1 (Th1)/T helper type 2 (Th2) differentiation, TNF (tumor necrosis factor) signaling, and GVHD (Fig. 1G). From this analysis of time-dependent gene regulation, we concluded that a subset of Trm is overexpressing tissue retention markers, senescence factors, and receptors required for maintenance of this population of cells47, which enables them to survive radiochemotherapy.

Gene expression-based markers identify CD4+ and CD8+ radiochemotherapy-resistant T cells

To corroborate the differential expression of molecules identified at the transcriptional level on resident and non-resident T cells, we matched RNA-based marker genes to the presence of surface markers as identified by multicolor immunostaining of skin cryosections. First, we used the gene expression data to create differentiation scores for resident T cells in skin and tissue-patrolling T cells from blood. The ITGA1 gene encoding CD49a, a marker identifying epidermal Trm with cytotoxic potential in vitiligo 48, was inconsistently expressed by skin T cells (fig. S3A), thus we did not use that as a marker of Trm. Using CCR7 and CD62L as the marker genes for tissue-patrolling T cells (Fig. 2A) and CD69 and ITGAE as the markers for Trm (Fig. 2B), we defined tissue-patrolling T cells as CCR7+ and/or CD62L+ and Trm as CD69+CD103±. We then stained skin biopsy tissue for these markers.

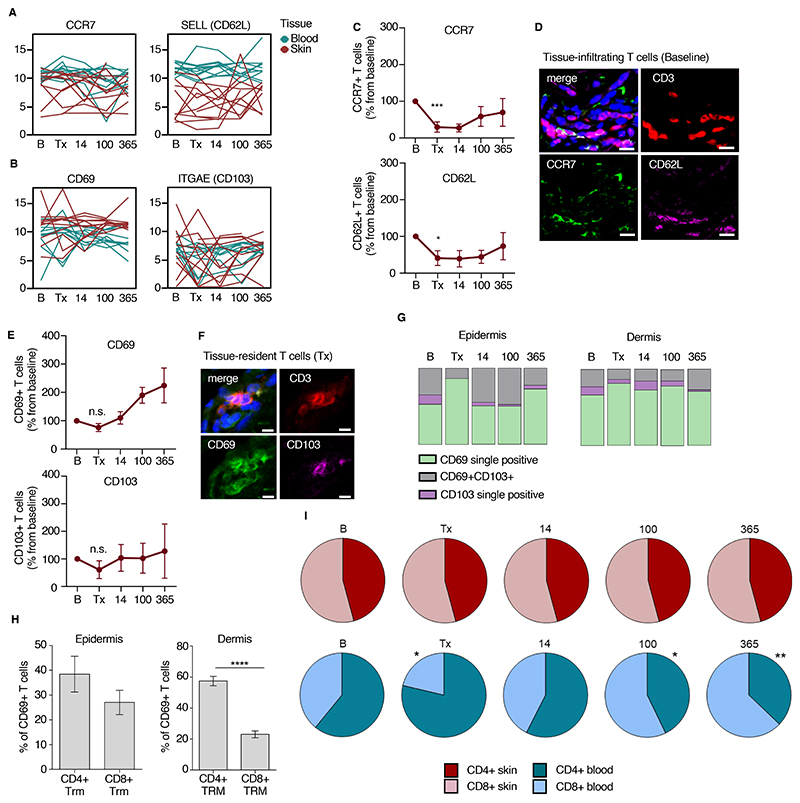

Figure 2. Gene expression-based markers identify radiochemotherapy-resistant T cells.

(A, B) RNA-based differentiation scores of marker genes for tissue-infiltrating (A) and tissue-resident (B) T cells. Data are shown as mean expression (log2) of genes of bulk T cells from blood and skin for each of 11 patients at 5 time points. One line represents one patient. (C) Relative numbers of CCR7 and CD62L-positive skin T cells as determined by immunostaining. The number of cells at baseline was set to 100%. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n=28). (D) Representative immunostaining of CCR7 and CD62L, indicating tissue-patrolling skin T cells, at baseline. (E) Relative numbers of CD69 and CD103-positive skin T cells as determined by immunostaining. The number of cells at baseline was set to 100%. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n=28). (F) Representative immunostaining of CD69 and CD103 at day of transplantation, indicating radiochemotherapy-resistant resident skin T cells. (G) Distribution of cells positive for Trm-surface markers on T cells of epidermis and dermis from immunostaining data. Data are shown as relative mean of all samples (n=28). (H) Distribution of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the epidermal and dermal CD69+ Trm population. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 28). (I) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell distribution in skin and peripheral blood over time. Data are shown as mean relative of all samples (n=28). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s pairwise comparisons (C, E, I) and paired t-test (C, E, H). Statistically significant changes to baseline or control group are indicated by *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

CCR7 and CD62L were low in baseline biopsies (fig. S2B) and further reduced by conditioning (Fig. 2C, D). Consistent with previous studies 1,43,49, we found that the tissue-residency marker CD69 was present on a large proportion of T cells in the upper dermis throughout the pre- and post-transplantation period (Fig. 2E,F, fig. S3B). Although CD69-positive T cells persisted and even increased in relative abundance in the skin over one year, CD103-positivity on T cells was not retained in all skin compartments and only returned to baseline expression in the epidermis after transplantation (Fig. 2E, G, fig. S3B). Both epidermal and dermal CD69+ T cells could be detected at the day of transplantation, and most of the radio-resistant Trm population after conditioning was CD69 single positive (Fig. 2G). Most of the dermal CD69+ Trm population at the time of transplantation was positive for CD4 (p<0.0001), whereas CD4+ and CD8+ Trm were equally prevalent in the epidermis (Fig. 2H). In the blood, CD4+ T cells were superior to CD8+ T cells in surviving conditioning and the CD4/CD8 ratio was variable with 1 year after transplantation (Fig. 2I). However, in the skin we found no difference in the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; baseline ratio was maintained throughout all time points (Fig. 2I).

We found that human skin Trm consist of CD8+ and CD4+ T cell populations in the epidermal and dermal compartments and that CD4+ T cells dominated among radiochemotherapy-resistant T cells in the blood. Although CD103 was present on epidermal T cells at baseline, CD103 single positivity did not define radiochemotherapy-resistant long-term Trm. Instead, CD69 was the predominating marker for human skin Trm and CD69-single positive and, to a lesser extent CD69+CD103+ Trm, were radioresistant.

Multifunctional, noncytotoxic, Trm display a unique survival program

We characterized Trm at the functional and transcriptional level to define (i) various populations of radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm, (ii) the pathways promoting their survival, and (iii) their cytokine production pattern before and after radiochemotherapy. We detected a regulatory T cell (Treg) (FoxP3+) population in the skin of patients. Over the course of allo-HSCT, the abundance of these was unchanged from baseline (fig. S3C). This Treg population included a small subset of regulatory Trm cells (CD69+ FoxP3+), which was also not changed in abundance over the course of allo-HSCT (fig. S3C).

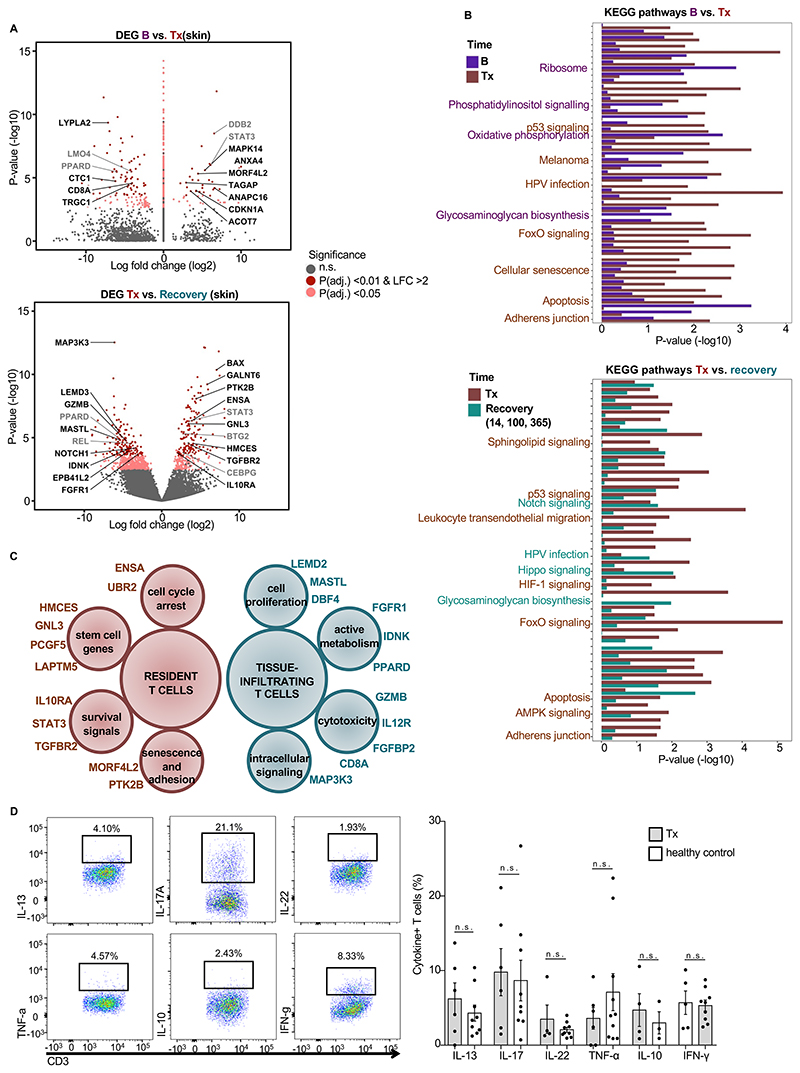

We analyzed the differentially expressed genes of skin T cells at the time of transplantation versus those in skin T cells at baseline before radiochemotherapy (upper panels in Fig 3A, B and in fig. S3D). We also analyzed the differentially expressed genes in skin T cells at transplantation versus those in skin T cells during the recovery period (14 – 365 days after transplant) (lower panels in Fig. 3A, B and in fig. S3D). Skin T cells at the time of transplantation represent radiochemotherapy-resistant, tissue-resident T cells; T cells in skin during recovery represent both tissue-resident T cells and circulating T cells that infiltrate the skin. Comparison of these gene expression signatures and the pathways enriched for each population indicated that skin T cells at the time of transplantation, representing radiochemotherapy-resistant T cells, lacked expression of genes associated with cytotoxic T cells, cell proliferation, and active metabolism (Fig. 3C). Instead, radiochemotherapy-resistant, resident skin T cells at the time of transplantation had increased transcription of genes associated with cellular senescence, cell cycle arrest, stem cells, and survival signals (Fig. 3C), suggesting that these cells were in a senescent state. Although radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm showed a senescent phenotype, upon stimulation the proportions of these cells that produced Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg cytokines were similar to those from healthy skin-derived T cells (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the fraction of cytokine-producing T cells from peripheral blood was low after radiochemotherapy and not significantly different from that in healthy donors (fig. S3 E,F). These data highlighted Trm as multifunctional resident cells of the skin that are, upon appropriate stimulation, functionally competent in promoting local protection or inflammation.

Figure 3. Unique survival program of Trm.

(A) Differentially expressed genes in skin T cells at baseline compared with those in skin T cells on the day of transplantation (upper) and on the day of transplantation compared with those on days 14 – 365 (lower). Volcano plots show differentially regulated genes in skin (n=11). (B) KEGG pathways enriched with upregulated and downregulated genes from the analysis in A. (C) Marker genes expressed by resident T cells (Tx) and tissue-infiltrating T cells (B, 14, 100, 365) as determined by transcriptome analysis in samples from A and B. (D) Cytokine production of resident T cells at Tx assessed by flow cytometry. (Left) Gating strategy and representative scatterplots of cytokine-positive skin T cells upon stimulation with phorbol ester and ionomycin from a patient on the day of transplantation. (Right) Frequencies of cytokine-positive T cells in the skin of patients on the day of transplantation (n=5) and healthy donors (n=9) as identified by intracellular cytokine staining. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s pairwise comparisons, * p < 0.05, n.s, not significant. B, baseline before radiochemotherapy; Tx, day of transplantation after radiochemotherapy

Donor and host T cells coexist after transplantation and are transcriptionally distinct

To further investigate radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing of T cells isolated from 2 patients at post-transplant day 14 by SMART-seq2 sequencing protocol50. Similar to RNA data of bulk T cells (Fig. 1), we identified time-dependent co-regulation of genes in 10 clusters (Fig. 4A). The gene regulation pattern of skin Trm (Fig. 1, clusters 2 and 3) was represented in single-cell transcriptome clusters 2 and 3 (Fig. 4A, fig. S4A). Investigating the time-dependent regulation of the cells in cluster 2, we found some genes were upregulated by most T cells after radiochemotherapy (at the time of transplantation), whereas other genes were expressed at similar levels before transplantation in a fraction of the cells and remained expressed in cells at day 14 (Fig. 4A, right). This persistent expression of genes indicated selective retention of a population of T cells constitutively expressing this set of genes in cluster 2.

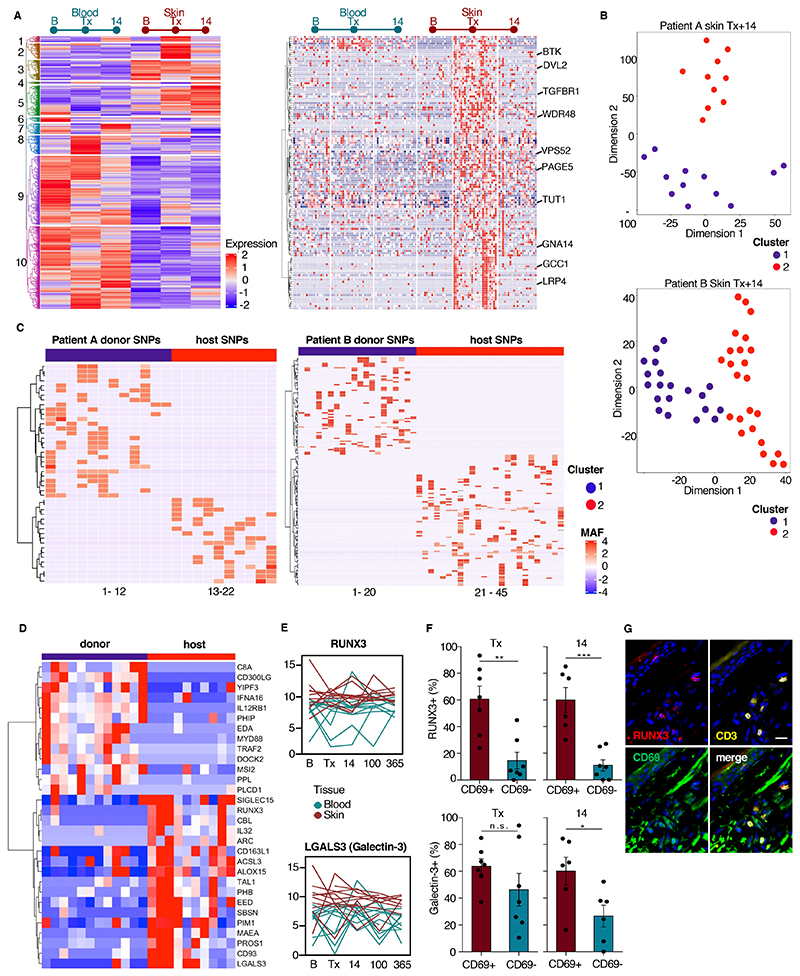

Figure 4. Donor and host Trm are transcriptionally distinct.

(A) Time-dependent transcriptional program in T cells shown by hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes from single blood T cells versus single skin T cells at baseline, day of transplantation, and 14 days after transplantation from 2 patients. Differentially expressed genes were selected at an adjusted p value < 0.01 and log2 fold change >2. Genes clustered according to co-regulation into 10 clusters (left). Enlarged view of the genes in cluster 2 with each column representing one cell (right). (B) Representative t-SNE plot of patients A and B of skin T cells at day 14. One dot represents one cell. (C) Allele frequency heatmap of host and donor specific SNPs in 22 T cells of donor A at day 14 (left, cluster 1 with 28 donor and cluster 2 with 18 host specific SNPs) and 44 T cells of donor B (right, cluster 1 with 69 donor and cluster 2 with 93 host specific SNPs). (D) Heatmap of selected 30 significantly differentially expressed protein-coding genes (p-value < 0.01 and log2 fold change >1) from donor versus host T cells comparison using the RNA sequencing data from donor and host T cells defined by the phenograph and SNP analysis. (E) RNA differentiation score of RUNX3 (upper) and LGALS3 (lower) over time. Data are shown as mean expression of bulk T cells from blood and skin in 11 patients at 5 time points. One line represents one patient. (F) Quantification of proportion of RUNX3-positive T cells (upper) and galectin-3-positive T cells (lower) by immunostaining skin tissue at the time of transplant (Tx) and on post-transplant day (14). Data are shown as mean percentage of RUNX3-positive or Gal-3-positive CD3+CD69+ and CD3+CD69- cells (n = 6). Error bars indicate the SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by paired t-test. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; n.s., not significant. (G) Representative immunostaining of RUNX3, CD3, and CD69 in skin on the day of transplantation.

At post-transplant day 14, phenogram analysis identified that skin T cells formed two distinct clusters in both patients analyzed (Fig. 4B). We hypothesized that these two clusters were due to the presence of both host and donor T cells in the patient’s skin. To define host and donor clusters we characterized the host single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (minimum coverage 20, minimum SNP quality 30) from pooled blood and skin T cells from baseline and SNPs from individual skin T cells at day 14 from the same individuals. SNPs from skin T cells at day 14 that were not present at baseline were considered to have come from the donor (Fig. 4C).

By defining the transcriptomes of these two cell populations, we attempted to identify new markers for tissue-resident and tissue-infiltrating T cells in skin. KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes showed activated donor T cells with upregulation of NF-κB signaling and various viral infection pathways (fig. S4B). Among the highly expressed genes in donor T cells, we identified several encoding molecules involved in cell migration (CD300LG, DOCK2) and inflammation (MYD88, C8A) (Fig. 4D, fig. S4C). Conversely, radiochemotherapy-resistant host T cells showed higher expression of genes encoding proteins associated with stem cells (SBSN, TAL1), anti-apoptotic signaling (PIM1, MAEA, CBL), the transcription factors EED and RUNX3 and several genes encoding for potential adhesion molecules (CD93, CD163L, LGALS3, SIGLEC15) (Fig. 4D). The upregulation of KEGG pathways for ‘Oxidative Phosphorylation’ and ‘Long-term Potentiation’ indicated altered metabolism in host T cells (fig. S4B). Furthermore, host Trm showed increased expression of ALOX15, encoding a molecule that positively regulates CD69 expression51.

To validate these findings from 2 patients in a larger patient cohort, we re-examined RNA-expression data from the bulk T cells of 11 patients for molecules identified as potential markers by single-cell RNA transcriptomics. We scored time-dependent transcription of potential candidate marker genes of Trm, using the process like the one used to score the Trm marker CD69 (Fig. 2). We identified a Trm score based on the expression of the gene encoding the transcription factor RUNX3, which maintains murine cytotoxic Trm13, and the gene LGALS encoding Galectin-3, which is present on CD4+ effector memory T cells52 (Fig. 4E). To confirm the proteins were present in cutaneous Trm, we performed immunostaining of T cells in skin tissue on the day of transplantation and on post-transplant day 14. We found 30% of the T cells were positive for RUNX3 at both time points, and that this protein was present preferentially in CD69+ T cells (Fig. 4F, G, S4D)). Similarly, Galectin-3 was detected on the surface of 50 – 60% of CD69+ T cells (Fig. 4F). Although a greater proportion of T cells were positive for Galectin-3 than were positive for RUNX3, this marker was present in a similar proportion of CD69+ and CD69- T cells at the time of transplantation (Fig. 4F).

Thus, we identified host radiochemotherapy-resistant T cells with a unique transcriptomic signature and RUNX3 and Galectin-3 as stable markers of these cells in skin. Our results showed that these cells persist together with donor T cells in tissues after allo-HSCT.

Replacement of the TCR repertoire in circulating T cells is paralleled by clonal expansion of tissue-resident αβTCR clones upon HSCT

To explore the persistence of T cell clonotypes in the recovery period after allo-HSCT and decipher the turnover and expansion of T cell clones in the skin and blood, we performed TCR immunostaining and high-throughput TCR sequencing of blood and skin T cells over the course of one year (Fig. 5A). Almost all surviving Trm were positive for αβTCR, whereas γδ T cells were preferentially eliminated and re-entered the skin after allo-HSCT (Fig. 5B-D). Across all time points, skin T cells were more polyclonal compared to those of the blood, emphasizing retained multi-functionality of skin T cells in the course of allo-HSCT (Fig. 5E).

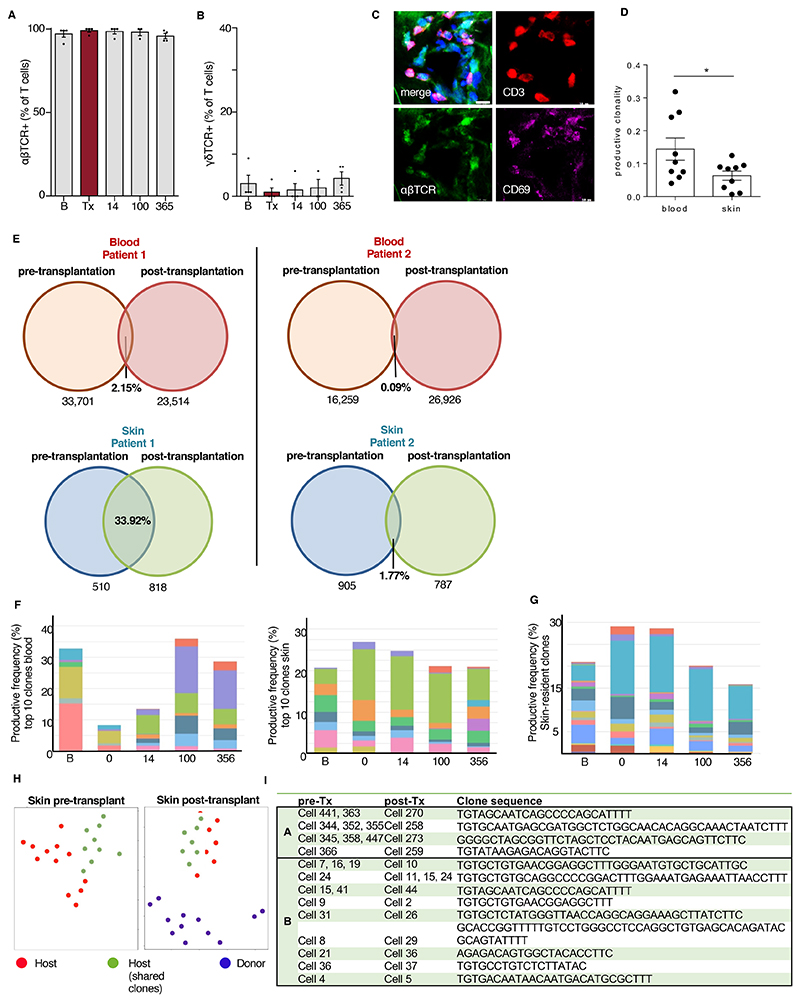

Figure 5. The TCR repertoire of skin T cells is partially conserved during allo-HSCT.

(A, C) Relative numbers of αβTCR+ (A) and γδTCR+ cells (B) among T cells in the course of allo-HSCT. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05). (C) Representative immunostaining of αβTCR, CD3, and CD69 at the day of transplantation. (D) Productive T cell clonality of blood and skin calculated from TCRB sequences across all time points. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 9). Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired student’s T-test (*, p < 0.05). (E) Numbers and frequencies of shared TCRB clones in blood and skin before (at baseline and the day of transplantation) and after allo-HSCT (14, 100, and 365 days) in two patients. (F) Productive frequency of top 10 clones at each time point for blood and skin T cells of patient 1 from panel E. (G) Productive frequency of skin-resident T cell clones (determined by presence at baseline and ≥1 time point after transplantation in patient 1 from E). (H) Example phenograph of single cell TCR clone tracking. Data points were manually colored to reflect clone origin. (I) Identical clone sequences in single cells from patients A and B at pre- (baseline and day of transplantation) and post-transplantation (day 14) time points. All clones were identified using TRUST tool.

We investigated the overlap of baseline-to-recovery phase clonotypes as identified by identical nucleotide sequence. In peripheral blood T cells, we detected little overlap of pre- and post-transplant clones (0.09 – 2.15% of clones present at baseline) (Fig. 5E). The skin of each patient harbored higher percentages of identical clones across time points, accounting for 15 – 20-fold difference in shared skin over shared blood clones (Fig. 5E). The top clones among blood T cells were completely replaced until post-transplant day 14, but we detected the top 10 TCR clones of skin from pre-transplant until day 365, with only 3 new top clonotypes emerging in skin between days 14 and 100 (Fig. 5F). By obtaining longitudinal samples of blood and skin samples over one year, we followed Trm clones in skin over time, defined the emergence of new clones, and compared them to those occurring in peripheral blood. Tracking only tissue-resident clones defined by their persistence over 1 year, we found that remaining TCR clones underwent relative expansion and were found in high frequencies of up to 30% of T cell clones (Fig. 5G). These data are in accordance with our transcriptional and immunofluorescence data on the persistence of radiochemotherapy-resistant Trm in the skin. Their clonal expansion indicated that these cells may proliferate in the skin.

Single-cell TCR analysis indicates developmental pathways of CD103+ Trm from CD69+CD103- precursors

Tracking T cell clones at various time points offers the opportunity to study different states of Trm precursors. From single-cell data we tracked identical clones based on their TCR sequence. In both individuals studied, we identified several clones in the skin that were present both before and after transplantation (Fig. 5H). In patient A, several cells had the same clone sequence at baseline, which each was detected in one cell post-transplantation. In patient B, we saw a similar dynamic with additionally clonal expansion of one host T cell clone, which gave rise to 3 cells post transplantation (Fig. 5I).

Analysis of Trm markers on identical clones revealed altered expression on pre- and post-transplantation T cells (fig. S4E). Whereas CD69 expression was reduced in clones after transplant, identical post-transplantation Trm clones gained CD103 expression, arguing for transition from a CD69 single positive to a CD103+ state. Furthermore, analysis of LGALS3 and RUNX revealed consistent expression in pre- and post-transplantation time point, indicating these are stable Trm markers (fig. S4E, Fig. 4D-F).

Long-term Trm are maintained for a decade after allo-HSCT

Low replacement rates of skin T cell clones over the course of 1 year suggest potential for even longer local survival. We therefore sampled 44 additional patients receiving peripheral blood stem cells from a sex-mismatched donor to track host-derived T cells by X/Y fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Fig. 6A). Strikingly, a mean of 50% (range: 5-95%) of skin T cells remained of host origin up to 10 years after allo-HSCT, whereas the presence of host T cells (host chimerism) in peripheral blood of the same patients was below detection level (< 5%) (Fig. 6B, D). This finding was not restricted to sex-mismatched allo-HSCT, because we detected comparable amounts of host T cells in a patient transplanted with sex-matched, HLA-A mismatched hematopoietic stem cells (Fig. S5A-C).

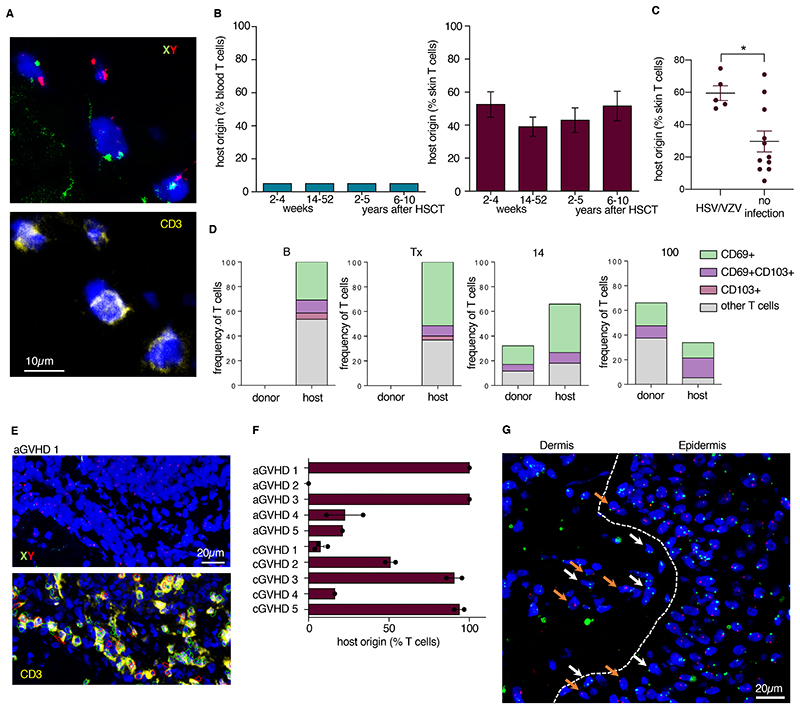

Figure 6. Long-term Trm are maintained for a decade after allo-HSCT.

(A) Representative image of FISH-labeled X (green) and Y (red) chromosomes, CD3 immunostaining (yellow) and DAPI counterstain in a patient 8 years after allo-HSCT. (B) Percentage of host T cells among peripheral blood (left) and skin T cells (right) after HSCT (weeks 2 – 4, n = 10; weeks 14 – 52, n = 11; years 2 – 5, n = 10; years 6 – 10, n = 13). Data shown as mean ± SEM. (C) Percentage of host T cells in skin from patients described in B who had a history of viral skin infection (herpes simplex virus, HSV or varicella zoster virus – VZV) between allo-HSCT and sampling time point (n = 5) and patients without viral skin infection after allo-HSCT (n = 11). Data shown as mean ± SEM, statistical analysis performed with unpaired student’s T-test (*, p < 0.05). (D) Proportion of donor and host skin T cells positive for the indicated tissue-residency markers at the indicated times before and after transplantation. Data are shown as mean of 5 patients. (E) Representative immunostaining (CD3, yellow) and FISH of the X and Y chromosomes (green and red, respectively) of dermal T cell infiltrate in acute GVHD patient 1 (aGVHD1). Red and green markings of the lower picture delineate automated imaging analysis by TissueFAXS software with red indicating T cells also positive for CD69 and green indicating CD3 single positive cells. (F) Percentage of host cells among T cells in acute (aGVHD patients 1 – 5, n = 5) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD patients 1 – 5, n = 5). Data are shown as mean of 2 experiments, >150 T cells/experiment. Error bars indicate the SEM. (G) Representative image of spatial relationship of host (XY, orange arrows) and donor (XX, white arrows) T cells in the papillary dermis and lower epidermis in inflamed skin that was previously stained for CD3. Image data were merged using StrataQuest software. All T cells (CD3+) are marked with arrows; unmarked cells are other cell types.

Considering the high variation of host-derived Trm in skin up to 10 years after allo-HSCT, we investigated the influence of cutaneous inflammation, including GVHD and systemic or local infections, on retention of host T cells within the time period between stem cell transplantation and skin sampling. We found increased host-derived T cells in the skin in patients that had cutaneous signs of herpes-simplex or varicella zoster virus infection (Fig. 6C), although this was not the case for patients upon reactivation of cytomegalovirus (CMS) (fig. S5D). One patient without skin infection presented with leukocytoclastic vasculitis after allo-HSCT (12.5% recipient cells 7 years post-transplant), the remaining patients did not show signs of common non-infectious inflammatory skin conditions at baseline or after allo-HSCT, such as psoriasis, eczema, lichen planus, or vitiligo. Additionally, patients with GVHD showing low response to systemic or topical steroid treatment had higher percentages of host T cells (fig. S5E). T cell origin did not depend on patient age at time of transplantation (fig. S5F).

We evaluated proportion of skin T cells positive for tissue-residency markers on both host- and donor-derived cells. Most of the host T cells were CD69 ± CD103 (Fig. 6D). Donor T cells rapidly acquired a residency phenotype (CD69+ and CD69+CD103+) after entering the skin and at post-transplant day 14 with > 50% of donor-derived skin T cells positive for one or both Trm markers (Fig. 6D). Together, these results highlighted that considerable numbers of Trm clones are maintained in the skin for > 10 years with newly arriving T cells rapidly exhibiting a Trm phenotype.

Proliferation of Trm precedes GVHD development

Skin is the organ most commonly affected by both acute GVHD (up to post-transplant day 100) and chronic GVHD (after post-transplant day 100), both of which are characterized by a dense lymphocytic infiltrate53. To address the occurrence of host T cells in GVHD propagation, we assessed donor-host chimerism in previously untreated cutaneous GVHD lesions. We found host T cells in 9 out of 10 individual GVHD patients, with host cells representing 0 – 100% of the cells (Fig. 6E, F). In biopsies displaying mixed chimerism, host and donor T cells were found in a close spatial relationship in T cell clusters in the papillary dermis (Fig 6G). We therefore hypothesized that host-derived Trm play a role in the pathogenesis of GVHD.

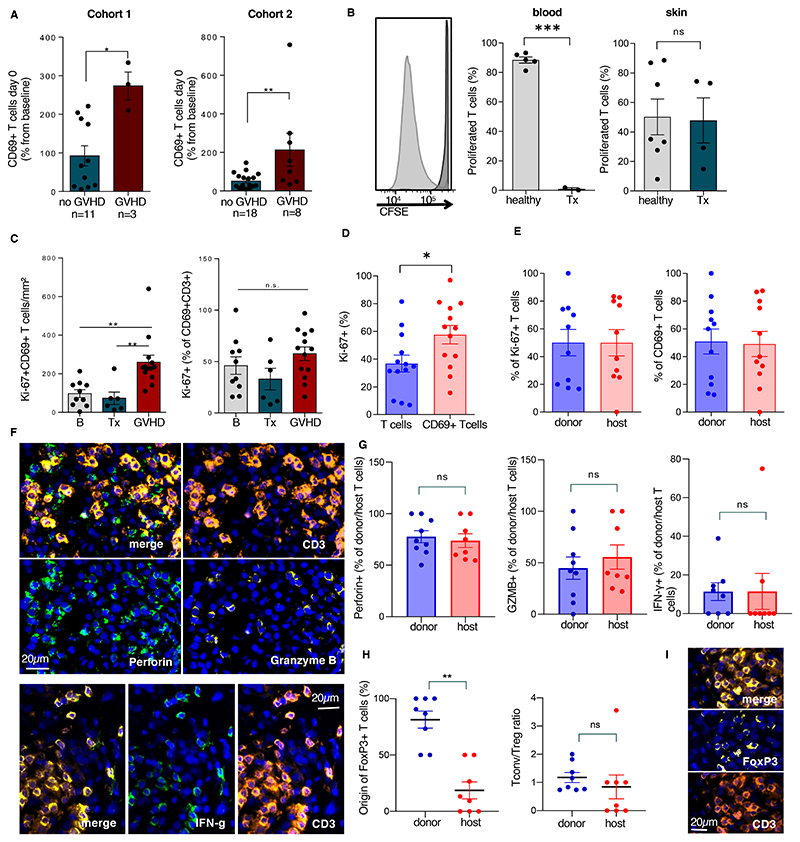

To test our hypothesis and unravel early mechanisms for GVHD development, we studied early expansion of host Trm from baseline numbers to the day of transplantation in two cohorts of individuals with and without later GVHD development (able S9). Indeed, we saw massive increase of host Trm at the time of transplantation (> 200% from baseline) in patients from cohort 1 who later developed GVHD, whereas stable Trm percentages were found in patients without cutaneous GVHD (≤ 100% from baseline) (Fig. 7A, left, p=0.0059). We observed a similar increase in cohort 2, with some patients who developed GVHD exhibiting an increase of host Trm >200% from baseline (Fig. 7A, right, p=0.0092). To determine the proliferative capacity of T cells at the time of transplantation, we isolated blood and skin T cells from biopsies taken at transplantation and stimulated the cells with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 to stimulate the TCR. Although proliferation of peripheral blood T cells at transplantation was massively impaired, radiochemotherapy-resistant skin T cells showed a normal proliferation rate comparable to T cells from healthy skin (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Proliferating Trm of host origin contribute to GVHD skin inflammation.

(A) Relative frequencies of CD69+ T cells at Tx compared to baseline CD69+ T cells in patients of cohort 1(left, n=14) and validation cohort 2(right, n=26). (B) Representative histogram and relative frequencies of proliferated (CSFElo) T cells upon TCR stimulation. Cells isolated from peripheral blood of healthy controls (n=5), peripheral blood of patients at Tx (n=5), skin of healthy controls (n=7) and skin of patients at Tx (n=4). (C) Ki-67+CD69+ T cells/mm2 skin (left panel) and relative frequencies (right panel) as determined by immunostaining at baseline (B, n=10), Tx (n=6) and in acute GVHD lesions (n=13). (D) Frequencies of Ki-67-expressing cells among CD3+ T cells and CD3+CD69+ T cells (n=13). (E) Percentage of donor vs. host-derived cells among proliferating (Ki-67+) T cells (left panel) and among CD69+ T cells (right panel) in GVHD as identified by X/Y-FISH and immunostaining. (F) Representative immunostaining of CD3 and lytic granules (perforin, granzyme B, top panels) and CD3 and cytokines (IFN-g, bottom panels) in a GVHD lesion. (G) Perforin, granzyme B and IFN-g positivity among donor and host T cells as detected by immunofluorescence and X/Y-FISH. (H) Donor/host chimerism of FoxP3+ T cells (left panel) and ratio of Tconv (FoxP3-) over Treg (FoxP3+) (right panel) among donor and host T cells in GVHD lesions (I) Representative immunostaining of CD3 and transcription factor FoxP3 in a GVHD lesion. All data shown as mean, error bars indicate the SEM. Each data point represents the mean of 2 independent measurements of one patient. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired student’s t-test (A, B, D, E, G, H), one-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparisons (C), *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Trm can mount rapid immune responses against pathogens. To find out if Trm after transplantation were as efficient in mediating local immune reactions as these cells before radiochemotherapy conditioning, we measured the number of proliferative Trm by Ki-67 staining (Fig. 7C). In skin sections at baseline and the day of transplantation, we found host Trm were proliferating. Although the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells among CD69+ T cells did not increase in GVHD (Fig. 7C, right), we detected higher absolute numbers of proliferating CD69+ T cells in GVHD lesions (Fig. 7C, left). When comparing CD69+ to total T cells in GVHD lesions, CD69+ T cells proliferated at a higher rate than the general T cell population (Fig. 7D). By defining the origin of T cells by FISH and combining that analysis with immunofluorescence staining of CD69 and Ki-67, we detected CD69+ donor-derived T cells and CD69+ host T cells in a close spatial relationship within the same GVHD skin section (Fig. 7E, left). In GVHD lesions, a similar number of host-derived T cells and donor-derived T cells were CD69 positive, and both populations proliferated at the same rate (Fig. 7E, right).

Host-derived T cells exhibit pro-inflammatory properties in GVHD

To address the consequence of host-derived T cells for GVHD inflammation, we investigated cytokine production of host- and donor-derived cells in skin lesions by immunofluorescence (Fig. 7F). A high proportion of host-derived Trm were positive for interferon (IFN)-γ, granzyme B, and perforin similar to donor-derived Trm within GVHD skin lesions (Fig. 7G). The proportion of T cells positive for CD49a, a marker found on cytotoxic Trm in vitiligo, was equivalent for host and donor T cells (fig. S5G). We detected only a small FoxP3-positive Treg population within the host-derived T cell fraction, and no differences were observed in ratio of conventional to Treg cells between donor and host cells (Fig. 7H,I).

In summary, these data indicated a prominent role of host-derived Trm in GVHD development and propagation, challenging the paradigm of exclusive graft-versus-host immunoreaction after allo-HSCT and highlighting the functional competence of long-term Trm of the skin even following myeloablative radiochemotherapy.

Discussion

Unlike murine memory T cells, which are short-lived due to the limited life span of mice, human Trm populations require extraordinary, decades-long longevity to provide life-long protection from pathogens at barrier sites4,54. Our unique experimental approach allowed us to reveal the survival capabilities and functional properties of human skin-resident T cells. We defined the biologic characteristics of this T cell population in a patient cohort that is comparable to the experimental strategies involving bone-marrow chimeric mice. By isolation of T cells at various timepoints from skin and blood under steady state before and after allo-HSCT, we tracked Trm by their host or donor origin up to a decade after transplantation and demonstrated their poly-functionality. Our studies revealed certain parallels between human and murine skin Trm but also highlighted important differences of their features, thereby expanding our knowledge of this critical immune cell population in steady-state and diseased human skin.

In the intestine, decades-long immunity to viral pathogens is mediated by antibody-secreting plasma cells55 and aided by Trm that are maintained for at least 12 months27. However, in tissues where B lymphocytes are largely absent, proof of long-lived, tissue-resident adaptive immunity is scarce. Adding to reports of long-term immunological memory mediated by T cells20 and first reports on short-term survival of Trm in human renal allografts (≤ 5 months)56 and transplanted lung tissue (≤ 12 months)28, we found here that 50% of human cutaneous T cells are long-term resident cells providing protection for more than 10 years. Increased numbers of host-derived Trm upon prior cutaneous inflammation suggested that local T cell proliferation occurred and implied that common factors can stimulate Trm expansion even at distant sites from the site of inflammation. Indeed, we found that clinical symptoms of herpes-simplex or varicella zoster virus reactivation occurred at skin sites other than where the biopsies were taken, yet the increased Trm numbers were detected at the biopsy site. This observation indicated the presence of systemic factors regulating Trm in peripheral tissues that are secreted upon local proliferation.

We experimentally addressed Trm survival strategies and determined that human Trm developed a senescent, stem cell-like profile, which enabled superior survival in skin even upon myeloablative radiochemotherapy. Trm sustenance was further aided by the up-regulation of genes encoding survival receptors and adhesion molecules. According to our transcriptomic and functional data, Trm abolished their senescent phenotype upon TCR stimulation, change metabolism to rely on oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism, and undergo local proliferation by clonal expansion. These findings are in line with murine studies showing that fatty acid-based metabolism supports long-term maintenance of Trm in tissues57. They further help explain the well-established presence of Trm in healthy-appearing former psoriasis lesions ed and the recurrence of fixed drug eruptions at the site of prior inflammation7,9,58.

Our patient cohort allowed us to reveal a potential role of Trm in inflammation in patients that developed GVHD. A role of Trm in cutaneous inflammation was indicated in patients after face transplantation, where T cells of the donor graft were associated with injured target cells59. In kidney transplantation, the concept of both graft-resident and graft-infiltrating T cells has recently been introduced60, and donor lymphocyte infusion early after allo-HSCT caused rejection of donor marrow by host T cells61. Furthermore, cases of murine and human syngeneic GVHD have been reported62–65. However, combined renal allograft transplantation and non-myeloablative HSCT achieved transplantation tolerance in 6 patients, arguing for a less prominent role for renal Trm in this constellation66.

Considering the data in the present study, we propose that host-derived Trm play a mostly unappreciated role in the initiation and propagation of barrier organ rejection after HSCT based on the observations that (i) high percentages of Trm at the day of transplantation were associated with the development of GVHD; (ii) proliferating Trm were present in skin samples under steady state and GVHD skin lesions; (iii) host-derived Trm with a proliferating subset were present in GVHD lesions in ratios of up to 100%; (iv) host-derived T cells in GVHD lesions produced Th1 cytokines and contained cytotoxic granules. Our data are therefore suggestive that Trm of host origin participate in GVHD pathology and present a potential target for therapeutic and preventive strategies.

One caveat of previously published findings is that markers for Trm and circulatory T cells, such as CD69 and CCR7, are used to define putatively stable cell subsets, but the profiles of the cells conceivably may change upon activation. Our work assessed marker validity in stable T cell subsets and identified additional markers that might be less variable within the lifecycle of Trm. In our patient samples, most human skin-resident T cells were positive for CD4 and the tissue-residency marker CD69, confirming previous analyses of skin T cells in a human skin-engrafted mouse model1. Although CD103 was described as tissue residency marker in mice and humans, we found a large proportion of Trm staining positive for CD69 only. We identified a small population of CD103 single-positive cells in the epidermis and dermis before transplantation, and this population was eliminated by radiochemotherapy. Tracking of identical TCR clones revealed altered expression of the genes encoding CD69 and CD103 before and after transplantation: Expression of CD69 was reduced, while ITGAE (encoding CD103) expression increased in clones over time. This finding indicated the presence of functionally and developmentally distinct subsets of tissue T cells defined by CD103 expression. Furthermore, these T cell subsets display distinct susceptibilities to environmental damage, indicated by their elimination by radiochemotherapy. We further showed that rapidly generated and newly-migrated Trm acquire residency markers CD69 and CD103 within days upon entering the skin, but these cells fail to occupy the full niche after transplantation.

However, some radiochemotherapy-resistant cells did not express either residency marker, which prompted us to search for novel markers of Trm, which would facilitate future characterization. By combining single-cell data transcriptomic data with bulk T cell-RNA analysis and subsequent protein confirmation, we identified two molecules that may differentiate skin-resident from tissue-patrolling T cells, namely RUNX3 and galectin-3. The gene encoding the transcription factor RUNX3 is expressed in murine CD8+ Trm and plays a role for CD8+ Trm generation13, but its relevance in human CD4+ and CD8+ Trm has not been addressed so far. Galectin-3 belongs to a group of evolutionarily conserved proteins widely distributed in human tissues that can directly bind pathogens at the surface of mononuclear phagocytes67 and may be involved in modulation of T cell activation68. The gene encoding galectin-3 was expressed by a subset of CD69-negative cells, indicating that a population of radiochemotherapy-resistant CD69- Trm may be detected by galectin-3 as Trm marker. Both markers were consistently expressed on identical single-cell TCR clones over time, indicating their potential to identify Trm by detection of RUNX3 and galectin-3 gene expression or protein abundance in T cells.

Limitations of our work include the need for detailed analysis of galectin-3 function and analysis of the expression of the encoding gene in murine Trm and Trm in human organs other than the skin. In addition, it remains to be addressed if functionally distinct subsets of Trm possess different Trm marker profiles with regard to CD69, RUNX3, and galectin-3. Lastly, although we provide first evidence for a potentially detrimental effect of Trm on GVHD development, the synergistic role of host- and donor-derived leukocytes in GVHD propagation needs to be addressed in murine models and comprehensive clinical studies.

Trm play a fundamental role in chronic T cell-driven immune responses, such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. Our data suggested a crucial role of Trm in tissue inflammation of GVHD, challenging the paradigm of a one-directional graft-versus-host immunoreaction and providing insights into the behavior of Trm. Additionally, our findings prompt a re-examination of treatment strategies in T cell-driven chronic inflammatory skin diseases, because pathogenic Trm subsets likely escape targeting by current therapies. Finally, it will be of great interest to determine whether long-lived cutaneous CD4+ Trm can function as a viral reservoir for chronic infections, such as HIV. If so, the possibility exists that cutaneous Trm can be directly targeted to contribute to clearance of viral diseases.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We investigated Trm biology in serial skin and blood samples and the putative role of Trm in human cutaneous GVHD. The proposed research follows ethical principles and national law and has been approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (ECS 1087/2016). The research involved the voluntary participation of patients with fully informed written consent and the collection of necessary personal data. The individual risks for patients participating in this study was minimal and we did not observe side effects in the course of the study. N values represent the number of patients in each experiment, and each experiment contained a minimum of two technical replicates.

Human tissue samples

Adults presenting with acute or chronic leukemia in complete remission (standard risk disease), myelodysplastic syndrome or myelofibrosis applicable to HSCT were included in the study prior to initiation of conditioning therapy at the Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit of the Medical University of Vienna. Samples of healthy appearing skin of the upper arm (6mm punch biopsies) as well as peripheral blood were taken before start of conditioning treatment (baseline, B, n=28), at the day of transplantation (Tx, n=16), two weeks after HSCT (14, n=22), 100 days (100, n=18) and 365 days after HSCT (365, n=16). Lower sample numbers at time points after baseline are due to patient drop out and mortality after HSCT. To confirm results on early Trm expansion in patients later developing GVHD (shown in Figure 7A-C), an additional cohort was prospectively sampled at baseline and Tx and followed up until 2 years after HSCT (n=26). For tracking of host/donor-derived T cells via X/Y-FISH, we obtained single biopsies of 54 patients who underwent sex-mismatched HSCT (biopsy sites: healthy appearing skin of the upper arm n=44, GVHD lesion n=10) in a time span of up to 10 years after donor cell infusion. Patients were examined for signs of skin inflammation by an experienced dermatologist at time of inclusion and at each sampling time point. GVHD scoring was continuously performed by specialists for internal medicine from the Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit of the Medical University of Vienna. For sampling of healthy skin, skin lacked signs of inflammation and patients didn’t show symptoms of GVHD of other organs at the time of sampling or one week before or afterwards. GVHD diagnosis was based on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus criteria69 and independent histological examination. Sampling was performed before initiation of treatment with corticosteroids. Fresh biopsies were either embedded and cryosectioned or digested following a collagenase IV skin digestion protocol as previously described53. Isolation of live PBMC from fresh heparinized blood samples was performed under sterile conditions with Ficoll-Paque reagent (Sigma Aldrich).

Cell stimulation

Cell proliferation upon TCR stimulation was tested on CFSE-labeled PBMC stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody and anti-CD28 antibody for 12 hours at 37°C. Cytokine release assays were performed upon stimulation with PMA/ionomycin for 4 hours at 37°C and subsequent addition of brefeldin A. Cells were labeled using surface antibodies followed by fixation, permeabilization and intracellular cytokine staining70 (Table S19).

Flow cytometry, cell sorting and library preparation

Flow cytometric analysis of single-cell suspensions was performed by surface and intracellular marker staining as previously described70. Single-cell suspensions were acquired using FACS Diva software on a FACS Aria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and sorted for 1 (single cell RNAseq) or 100 (bulk RNAseq) live CD45+CD3+ singlets into cell lysis buffer containing RNase inhibitor (Takara). cDNA synthesis and enrichment were performed using the Smart-seq2 protocol50 and library preparation was conducted using Illumina Nextera XT library preparation kit. The libraries were sequenced by the Biomedical Sequencing Facility at CeMM using the Illumina HiSeq 3000/4000 platform and the 50 bp single-read configuration. After single-cell sequencing, 1 cell from Patient A and 2 cells from patient B did not meet quality control criteria.

Bioinformatic analysis of sequencing data

Single-end reads were trimmed for low quality bases and removal of low-quality reads using ReadTools (v.1.0.0)71. Trimmed reads were mapped to the Homo sapiens genome (GRCh38.92 assembly) using STAR (v2.5.3a) mapper72. The reads mapped in multiple genomic locations were eliminated by using Samtools (v1.4)73. Read counts for features (exons) were generated using the featureCounts function from the Subread package (v 1.22.1)74.

For bulk RNA-seq data analysis, genes with fewer than 10 reads were eliminated from the further analysis in all samples. Gene expression analysis was done with DESeq2 (v 3.22.3)75 using the Ensembl Known Gene models (version GRCh38.92) as reference annotations. For differential gene expression analyses genes were considered differentially expressed if they showed a P value (FDR) < 0.05, adjusted for multiple hypothesis correction and an absolute log2 (fold change) > 1. Normalized count (log2) by DESeq2 was used to perform the Principle component analysis (PCA), t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), hierarchical clustering (HC) and to create heatmaps and scatter plots.

For single-cell RNA-seq data analysis, we had first removed the low quality cells with log-library sizes that are more than 3 median absolute deviations (MADs) below the median log-library size and the log-transformed number of expressed genes is 3 MADs below the median. We also removed the low expressed genes that are not expressed in at least 3 cells. After quality control we normalized the count matrix by using the deconvolution method from Scater package76. The technical bias was modelled by using the “trendVar” and “decomposeVar” methods and removed by using the “denoisePCA” method from Scater package. Batch effect was removed by using the “removeBatchEffect” function from limma package77. The clustering of cells was done with the t-stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) method with “ncomponents=2, perplexicty=10 and ntop=500” parameters. The differentially expressed genes were identified with P-value < 0.01 and logFC> 1. The heatmaps for selected genes were created by using the pheatmap package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html). KEGG pathway enrichment and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis were done by using the KEGGA and GOANA methods respectively from limma package77. Top 20 KEGG pathways and GO terms were selected for each gene set at corrected p-value (p adj <0.05).

To characterize host- and donor-specific marker SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms), we used FreeBayes tool (v1.0.0)78 with “-iXu -C 2 -q 30” parameters. After SNP identification we further filtered the low quality SNPs with sequencing depth < 20× and SNP quality < 30. In summary, we first characterized the host only SNPs by pooling all cells from baseline and day of transplantation from both skin and PBMC. We then called SNPs at day 14 from skin for each cell individually and considered SNPs as reliable marker for donor or host cells if a SNP was present in at least 3 cells. Finally, we assigned the SNPs from individual cells from day 14 as donor-derived if it was absent in the SNPs from baseline and Tx time points.

Single cell TCR sequencing

In order to extract the T cell clones from single-cell RNA sequencing data, we used the TRUST (TCR repertoire utilities for solid tissue) tool version 4.079. We ran TRUST with the recommended default parameters, which takes single-end sequencing reads mapped to the human reference genome in BAM format as the standard input. It automatically detects input library type, selects informative unmapped reads, assigns read into TCR genes on the basis of putative motifs, assembles reads into contigs and annotates the assembled CDR3 sequences with International Immunogenetics Information System (IMGT) nomenclatures. With this method we identified clones for each cell individually and finally identified the shared clones between pre-and posttransplantation time points among the cells.

High-throughput TCR sequencing

DNA was extracted from skin cells isolated at indicated time points using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, 51304)80. For each sample, 600ng of DNA were used as template to amplify and sequence TCRB CDR3 segments with a set of bias-controlled primers (Adaptive Biotechnologies, ImmunoSEQ hsTCRB kit). Trimming and annotation of CDR3 segments (identifying contributing V, D and J genetic fractions according to the International ImMunoGeneTics collaboration) was done by the kit manufacturer. Data analysis including TCR diversity and clone tracking was carried out in the ImmunoSEQ platform (Adaptive Biotechnologies).

Multicolor immunofluorescence

Multicolor immunofluorescence (IF) stainings for T cell surface markers were established on 5μm cyrosections. Protocols for immunofluorescence labelling of cells on acetone-fixed cryosections were adapted from Brüggen etal.70 (antibodies listed in Table S19. Slides were scanned using a Z1 Axio Observer microscope equipped with a LD Plan-Neofluar 20x/0.4 objective (Zeiss) and TissueFAXS imaging system and analyzed using TissueQuest and StrataQuest software (TissueGnostics GmbH)81. Blood vessels and apocrine glands were excluded from analysis. Matched isotype controls were included for analysis of background staining. Measurements were taken from two sequential sections as replicates.

X/Y fluorescence in situ hybridization

X/Y chimerism analysis was performed on 5μm skin cryosections combined with surface marker labeling. Briefly, sections were immunolabeled with directly conjugated anti-CD3 (BD), anti-CD69 (BD) and anti-CD103 (BioLegend) antibodies followed by acquisition of images using TissueFAXS system. Subsequently, surface marker staining was removed and nuclei were permeabilized using pepsin solution for 15 min at 37°C. Sections were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, and further processed using FAST FISH X/Y/18 Prenatal Enumeration Kit (Cytocell). Hybridization was performed at 75°C followed by 24hr incubation with FISH-probe at 37°C. Images of sections were acquired once more and files were merged using a custom-designed StrataQuest software profile (TissueGnostics GmbH). Donor-derived and host-derived T cells were determined using automated dot quantification of X and Y chromosomes and histologically verified by two independent, blinded examiners. Measurements were taken from four individual sections of the same skin biopsy.

Statistical analysis

Flow cytometric data was analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Data were tested for normal distribution by the Shapiro-Wilk test. In cases of normal distribution, parametric one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparisons and two-tailed Student’s t-test were used to compare more than two groups. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare GVHD and no GVHD groups in Fig. 7. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). The data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and individual data points.

Supplementary Material

One-sentence summary.

GVHD includes an auto-inflammatory host-versus-graft component from recipient-derived skin-resident memory T cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Weninger for his valuable scientific input. Editorial services were provided by Nancy R. Gough (BioSerendipity, LLC, Elkridge, MD)

Funding

This work was supported by funds of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank, Anniversary Fund, project number: 17872), by the research stipend of the German Foundation of Dermatology (DSD/ADF), by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, P30972) and by the Innovation Fund of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW, project number: IF_2017_29). J.S. was supported by a DOCmed fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. P.V.-G. had funding support from the Fondation René Touraine-Celgene and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.S. planned and conducted experiments, analyzed data and drafted the figures and manuscript, R.V.P. and M.M.J. analyzed data and performed statistical testing. N.B., L.K., P.V.G. and B.R. conducted experiments, N.B. compiled figures. M.M., P.K., and W.R. performed disease scoring. G.S., G.S., P.W., T.K. and C.B. designed the study, provided reagents and revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback to the manuscript.Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability

The sequencing data discussed in this publication was deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and is accessible via GEO Series accession number GSE146495.

References

- 1.Teijaro JR, et al. Cutting edge: Tissue-retentive lung memory CD4 T cells mediate optimal protection to respiratory virus infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:5510–5514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glennie ND, et al. Skin-resident memory CD4+ T cells enhance protection against Leishmania major infection. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1405–1414. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stary G, et al. VACCINES. A mucosal vaccine against Chlamydia trachomatis generates two waves of protective memory T cells. Science. 2015;348:aaa8205. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang X, et al. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ T(RM) cells providing global skin immunity. Nature. 2012;483:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinert EM, et al. Quantifying Memory CD8 T Cells Reveals Regionalization of Immunosurveillance. Cell. 2015;161:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark RA, et al. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol. 2006;176:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallais Serezal I, et al. A skewed pool of resident T cells triggers psoriasis-associated tissue responses in never-lesional skin from patients with psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1444–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallais Serezal I, et al. Resident T Cells in Resolved Psoriasis Steer Tissue Responses that Stratify Clinical Outcome. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1754–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matos TR, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing alphabeta T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031–4041. doi: 10.1172/jci93396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyman O, et al. Spontaneous development of psoriasis in a new animal model shows an essential role for resident T cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Exp Med. 2004;199:731–736. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackay LK, Kallies A. Transcriptional Regulation of Tissue-Resident Lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackay LK, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;352:459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milner JJ, et al. Runx3 programs CD8(+) T cell residency in non-lymphoid tissues and tumours. Nature. 2017;552:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature24993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Lee YT, Kaech SM, Garvy B, Cauley LS. Smad4 promotes differentiation of effector and circulating memory CD8T cells but is dispensable for tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2015;194:2407–2414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilharm A, et al. Mutual interplay between IL-17-producing gammadeltaT cells and microbiota orchestrates oral mucosal homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:2652–2661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818812116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson KG, et al. Intravascular staining for discrimination of vascular and tissue leukocytes. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:209–222. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KG, et al. Cutting edge: intravascular staining redefines lung CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 2012;189:2702–2706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebhardt T, et al. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebhardt T, et al. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature. 2011;477:216–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akondy RS, et al. Origin and differentiation of human memory CD8 T cells after vaccination. Nature. 2017;552:362–367. doi: 10.1038/nature24633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghans JAM, Tesselaar K, de Boer RJ. Current best estimates for the average lifespans of mouse and human leukocytes: reviewing two decades of deuterium-labeling experiments. Immunol Rev. 2018;285:233–248. doi: 10.1111/imr.12693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muranski P, et al. Th17 cells are long lived and retain a stem cell-like molecular signature. Immunity. 2011;35:972–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishton RJ, Sukumar M, Restifo NP. Metabolic Regulation of T Cell Longevity and Function in Tumor Immunotherapy. Cell Metab. 2017;26:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui G, et al. IL-7-Induced Glycerol Transport and TAG Synthesis Promotes Memory CD8+ T Cell Longevity. Cell. 2015;161:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark RA, et al. Skin effector memory T cells do not recirculate and provide immune protection in alemtuzumab-treated CTCL patients. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:117ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klicznik MM, et al. Human CD4(+)CD103(+) cutaneous resident memory T cells are found in the circulation of healthy individuals. Sci Immunol. 2019;4 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav8995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartolome-Casado R, et al. Resident memory CD8 T cells persist for years in human small intestine. J Exp Med. 2019 doi: 10.1084/jem.20190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder ME, et al. Generation and persistence of human tissue-resident memory T cells in lung transplantation. Sci Immunol. 2019;4 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease-Biologic Process, Prevention, and Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2167–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1609337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathewson ND, et al. Gut microbiome-derived metabolites modulate intestinal epithelial cell damage and mitigate graft-versus-host disease. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:505–513. doi: 10.1038/ni.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jardine L, et al. Donor monocyte-derived macrophages promote human acute graft versus host disease. bioRxiv. 2019:787036. doi: 10.1101/787036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamura K, et al. The transcription factor EPAS1 links DOCK8 deficiency to atopic skin inflammation via IL-31 induction. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13946. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willinger T, Freeman T, Hasegawa H, McMichael AJ, Callan MF. Molecular signatures distinguish human central memory from effector memory CD8 T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2005;175:5895–5903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patil VS, et al. Precursors of human CD4(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes identified by single-cell transcriptome analysis. Sci Immunol. 2018;3:eaan8664. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan8664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guarda G, et al. L-selectin-negative CCR7-effector and memory CD8+ T cells enter reactive lymph nodes and kill dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:743–752. doi: 10.1038/ni1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herndler-Brandstetter D, et al. KLRG1(+) Effector CD8(+) T Cells Lose KLRG1, Differentiate into All Memory T Cell Lineages, and Convey Enhanced Protective Immunity. Immunity. 2018;48:716–729.:e718. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCully ML, et al. CCR8 Expression Defines Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Human Skin. J Immunol. 2018;200:1639–1650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan Y, Kupper TS. Metabolic Reprogramming and Longevity of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1347. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaid A, et al. Persistence of skin-resident memory T cells within an epidermal niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5307–5312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322292111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Behr FM, et al. Blimp-1 Rather Than Hobit Drives the Formation of Tissue-Resident Memory CD8(+) T Cells in the Lungs. Front Immunol. 2019;10:400. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar BV, et al. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2921–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackay LK, et al. Cutting edge: CD69 interference with sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor function regulates peripheral T cell retention. J Immunol. 2015;194:2059–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabashima K, et al. CXCL12-CXCR4 engagement is required for migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1249–1257. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]