Abstract

Unclean combustion of solid fuel for cooking and other household energy needs leads to severe household air pollution (HAP) and adverse health impacts in adults and children. Replacing traditional solid fuel stoves with high efficiency, low-polluting semi-gasifier stoves can potentially contribute to addressing this global problem. The success of semi-gasifier cookstove implementation initiatives depends not only on the technical performance and safety of the stove, but also the compatibility of the stove design with local cooking practices, the needs and preferences of stove users, and community economic structures. Many past stove design initiatives have failed to address one or more of these dimensions during the design process, resulting in failure of stoves to achieve long-term, exclusive use and market penetration. This study presents a user-centered, iterative engineering design approach to developing a semi-gasifier biomass cookstove for rural Chinese homes. Our approach places equal emphasis on stove performance and meeting the preferences of individuals most likely to adopt the clean stove technology. Five stove prototypes were iteratively developed following energy market and policy evaluation, laboratory and field evaluations of stove performance and user experience, and direct incorporation of stove user input. The most current stove prototype achieved high performance in the field on thermal efficiency (ISO Tier 3) and pollutant emissions (ISO Tier 4), and was received favorably by rural households in Sichuan province of Southwest China. Among household cooks receiving the final prototype of the intervention stove, 88% reported lighting and using it at least once. At five-months post-intervention, the semi-gasifier stoves were used at least once on an average of 68% [95% CI: 43, 93] of days. Our proposed design strategy can be applied to other stove development initiatives in China and other countries.

Keywords: cookstove, iterative engineering, processed biomass pellets, rural household energy, semi-gasifier, stove design and development

1. Introduction

Nearly three billion people worldwide use solid fuel (e.g. biomass, coal) for cooking and heating, and over one-fifth of solid fuel users live in China (Bonjour et al., 2013). The household air pollution generated from incomplete combustion of solid fuels is estimated to cause 2.9 million yearly premature deaths worldwide (Forouzanfar et al., 2015) and thought to be an important contributor to global and regional climate change (Bond et al., 2013).

The harmful health and environmental impacts of air pollution from traditional solid fuel stoves have motivated the design and dissemination of more efficient, cleaner-burning stoves such as gas, electric, and biomass-fuelled technologies. Early stove designs, mostly biomass-burning stoves, were primarily motivated by fuel saving and forest conservation goals and did little to reduce air pollution exposures (Arnold et al., 2003). More recent stove designs aim for high combustion efficiency and low pollution emissions to reduce air pollution exposures and improve health (IWA, 2012; Jetter et al., 2012). Since 2010, hundreds of different stove designs, the majority of which are designed to burn biomass more efficiently, have been distributed to an estimated 53 million homes (Ruiz-Mercardo et al., 2011; GACC, 2016). Yet, findings from observational studies and randomized trials suggest that most programs failed to introduce stove designs that were scalable in a community setting and substantially reduced air pollution exposures while functionally replacing the traditional stoves (Agarwal, 1983; Manibog et al., 1984; Ruiz-Mercado et al., 2011; Rehfuess et al., 2014; Kshirsagar and Kalamkar, 2014).

Ambitious targets for scaling up household energy interventions have been set by a number of national governments, including China, India, Ghana, Bangladesh, Guatemala, Nigeria, and Kenya, often in partnership with international agencies (GACC, 2016;Urmee and Gyamfi, 2014). To meet the World Health Organization’s (WHO) interim household air pollution guideline and to maximize population health benefits, near exclusive, community-wide use of the cleanest stoves is required (Johnson and Chiang, 2015). Decades of disappointing stove intervention programs highlight the need for new approaches and development efforts (Manibog, 1984; Gill, 1987; Ezzati and Kammen, 2002; Ezzati and Baumgartner, 2016).

The majority of household stove design efforts have emphasized technological advances and laboratory performance (Kumar et al., 2014). Some stove design efforts have addressed other design criteria, including fuel cost and access (Febriansyah et al., 2014; Ahiduzzaman et al., 2013),multi-functional stoves(Raman et al., 2014), and user experiences, preferences, and input(Thacker et al. 2017). However, integration of these design criteria throughout the stove design and development process, while maintaining high-level performance in the field, has been lacking.

In this paper, we document a_comprehensive, user-centered engineering approach to the design and development of low-polluting biomass stove interventions for large-scale implementation in rural China. We present this iterative stove engineering process for a semi-gasifier cooking and water-heating stove that was concurrently informed by user feedback on stove acceptability and functionality and ongoing laboratory and field-based performance testing of efficiency and emissions. Specifically, we demonstrate performance of an innovative stove design that achieves high efficiency and clean combustion, according to existing international guidelines, and that integrates desirable features that meet users’ cooking needs, preferences, and aspirations. This study provides a useful guide for anticipating the opportunities and barriers to the development, adoption, and use of stoves that meet national and international goals for household cooking and heating interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Assessing the household energy market and policy environment

Prior to starting stove design, we gathered information on commercially available biomass cookstoves in China through field visits to local stove markets and to villages near Beijing where stoves, and in particular semi-gasifier stoves, had been implemented. In addition, we assessed the existing national policy environment for rural energy, including regional and local capacity to produce processed biomass fuel.A complete timeline of the stove design process is provided in Figure S1.

2.2. Stove design concept and prototyping

Briefly, semi-gasifier stoves operate through a two-step process: 1) fuel is burned near the base of the combustion chamber after introducing primary air, producing syngas that 2) is combusted again with introduction of secondary air near the chamber opening. This two-stage combustion process has excellent oxygen supply and yields high thermal power, near-complete fuel combustion, and reduced pollution emissions (Anderson et al., 2007).

We initiated the semi-gasifier stove design process by defining the overall design objectives and developing criteria and evaluation metrics by which achievement of the design objectives would be evaluated. We produced and tested stove prototypes, iteratively modifying the stove design to meet the design criteria.

2.3. Stove performance testing in the laboratory

For each stove prototype, we formally evaluated the performance, namely energy efficiency and air pollution emissions, according to the ISO standardized Water Boiling Test (ISO, 2014) and under stove operating conditions that simulated rural Chinese cooking behavior (Carter et al., 2014). Laboratory performance testing also included the following: speed of ignition, speed of fuel loading, range of firepower adjustment (i.e., cooking power), total power requirements, safety (Table S1), and robustness to non-optimal fuel loading conditions (Figure S2). Results from laboratory testing were used to inform stove design modifications and engineering decisions.

2.4. Field evaluation of user experience and stove use patterns

Targeted and repeated field evaluation of users’ experiences provided an opportunity to examine the stove’s functionality and to further improve the design with respect to user acceptability and reproducibility of traditional cooking methods. Later-stage prototype stoves were introduced to village homes in rural Sichuan on a trial basis to obtain feedback on user experiences and evaluate whether the stove was robust to ‘real life’ usage conditions. Pelletized biomass fuel produced from a nearby village-level factory was supplied to homes at no cost to remove barriers to stove use. Selected homes were already enrolled in a household energy study. A detailed description of the the study site and homes’ energy practices are provided elsewhere (Ni et al., 2016).

We conducted structured and semi-structured interviews with primary cooks at 2 days and 6 weeks post-installation of the prototype stoves. Questions captured information on cooking behaviors (e.g., “What are the tasks for which you use the prototype stove?”), preferences (e.g., “What aspects of the prototype do you like compared with your traditional stove?”), and recommendations for design and functionality (e.g., “If you could modify one aspect of the prototype stove, what would you choose?”). Interviews were conducted in Mandarin-Chinese and took approximately 30 minutes. This information influenced technical design parameters (e.g., pot sizes; pellet tank and combustion chamber dimensions; flame adjustment range) and improved the stove for commercial production (Table S2).

In 10 homes with the Prototype V stove (referred to hereafter as the Tsinghua University stove, or “THU” stove), we monitored stove use for 6 months after the installation using real-time temperature data loggers (Model DS1922L, Berkeley Air, USA) that were placed on the new and traditional stoves, as well as on a kitchen wall to control for kitchen temperature fluctuations. The methods used to identify combustion events using the temperature sensors are described elsewhere (Clark et al., under review)

2.5. Stove performance testing in homes

Air pollution emissions and energy efficiency of the THU and traditional stoves were evaluated in rural Sichuan homes under conditions of real-world and uncontrolled use, approximately 6 months after installation. Details on the field emissions testing methods and measurements are provided in the SI (Section S1). Briefly, we selected 16 homes with the THU stoves and 15 homes with traditional cookstoves and accessible chimneys for field performance testing in June and July, 2016. We measured gaseous (e.g., CO, CO2, NOx) and PM2.5 emissions during complete cooking events, and determined the emission factors using the carbon balance method (Zhang et al., 2000). All measurements were conducted by sampling air from chimneys.

3. Results

3.1. Summarizing the household energy market and policy environment

Pre-stove design field visits and information gathering

We identified over 1500 household stove manufactures, representing over 3000 commercially available stove brands with annual sales estimated at nearly 20 million units in China. Most stoves were designed to burn coal, a fuel that is increasingly regulated and even banned in some regions in China (Tollefson, 2008; Caiet al., 2016). The majority of commercially available biomass stoves were designed for space heating. The existing available semi-gasifier biomass cookstoves all lacked user-desired functions such as auto-ignition and flame adjustment. Field visits to homes near Beijing revealed that most homes with semi-gasifier stoves had suspended use due to breakage or difficulty using them for cooking. We identified several design features that led to frequent breakage, namely cracking of the inner combustion chamber wall and stove grate blockage from slag that was a byproduct of inefficient ash removal. In addition, most semi-gasifer cookstoves required fuel loading from the top, a feature that made it impossible to add fuel during cooking and, according to stove users, greatly limited its functionality to meet daily cooking needs.

National rural energy policy

Coal replacement and reduction programs in China are expected to increase in number and scale over the next decade (Feng and Liao, 2016).

In its place, production and use of processed biomass fuel were identified as a priority area for rural energy development (NDRC, 2007). China’s National Energy Administration announced a goal to increase biomass energy development by the year 2020 to 58 million tonnes annually, of which 30 million tonnes should be processed biomass (NEA, 2016). Although access to and use of gaseous cooking fuels, including liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), is increasing throughout China (Tao et al., 2016), many rural households continue to use biomass fuels as their dominant cooking fuel, potentially for reasons related to affordability and cooking preferences (Shan et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). The policies supporting development of cleaner-burning biomass resources may increase interest among current stove manufacturers to diversify their technologies to include biomass-fired stoves that burn pelletized biomass fuel (Reed and Larson, 1997; Anderson et al., 2007).The feasibility of producing processed biomass fuel at the village scale, rather than traditional large-scale centralized production, is discussed elsewhere (Shan et al., 2016).

3.2. Stove prototyping

The primary design goal was to create an efficient, low-emitting semi-gasifier cookstove that would be accepted and used near exclusively by households receiving the planned stove and fuel intervention. To meet this goal, we defined seven design criteria and associated evaluation metrics (Table 1).

Table 1. Design criteria and evaluation metrics considered throughout design and development of the semi-gasifier cookstove and pelletized biomass fuel combustion.

| Design Criteria | Evaluation Metrics | Target Performance Indexes | Achievement relative to Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| High energy utilization | Stove thermal efficiency (expressed as %) | >35% | >40% |

| Low pollutant emissions | Mass emitted of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and carbon monoxide (CO) per mass of fuel burned and per energy unit delivered, and per task, under conditions of controlled and uncontrolled stove use | CO emission ≤9 g/MJd, and PM2.5 emission ≤168mg/MJd, matching the highest performance targets (Tier 4) set by the ISO International Working Agreement Tiered Cookstove Guidelines (ISO, 2012). | Achieved Tier 3 when including all data; excluding two high-emitting households, Tier 4 stove pollutant emission performance metrics met. |

| Ease and convenience during use | Duration and effort required for stove operation, including fuel loading and ignition before cooking; flame and firepower adjustment during cooking; ash removal | Cooking can begin within 3 minutes following ignition; firepower can be easily adjusted between the conditions of low power (30% of the maximum achievable power) and high power (100% of the maximum). | Met and exceeded goals for ignition speed and power variability. |

| Safety | Smooth surface and stable stove body; electrical safety; burn prevention in compliance with Biomass Stove Safety Protocol Guidelines (Gallagher et al., 2016) | Achieve the safest level (tier = 4), based on performance with respect to ten standardized protocols. | Achieved Tier 4 |

| Adaptability | Capacity of stove to perform multiple tasks, including diverse cooking activities and water boiling | Perform more than 80% of daily cooking activities and water boiling. | Intervention stoves used for many, but not all, daily cooking activities. |

| User acceptability | Users’ attitudes toward the new stove; initial and long-term choice to use (or to not use) the stove; use of the gasifier stove in replacement of, or in addition to, the traditional cookstove | More than 50% replacement of the traditional cookstove over the long-term (6 months) deployment. | In homes using the intervention stove, traditional and interventions stoves were used separately and for a similar number of meals per day. |

| Material cost and durability | Anticipated years of operation, under conditions of normal use; Initial cost and annual cost of repairs | Anticipated years of operation for more than 10 years under conditions of normal use; similar initial cost level to traditional cookstoves (RMB 1500 (US$215)); annual cost of repairs will be zero in the first three years, and less than RMB 70 (US$ 10) annually in the following years. | Durability yet to be determined. Initial capital cost < RMB 1600. Repairs cost < RMB 50 |

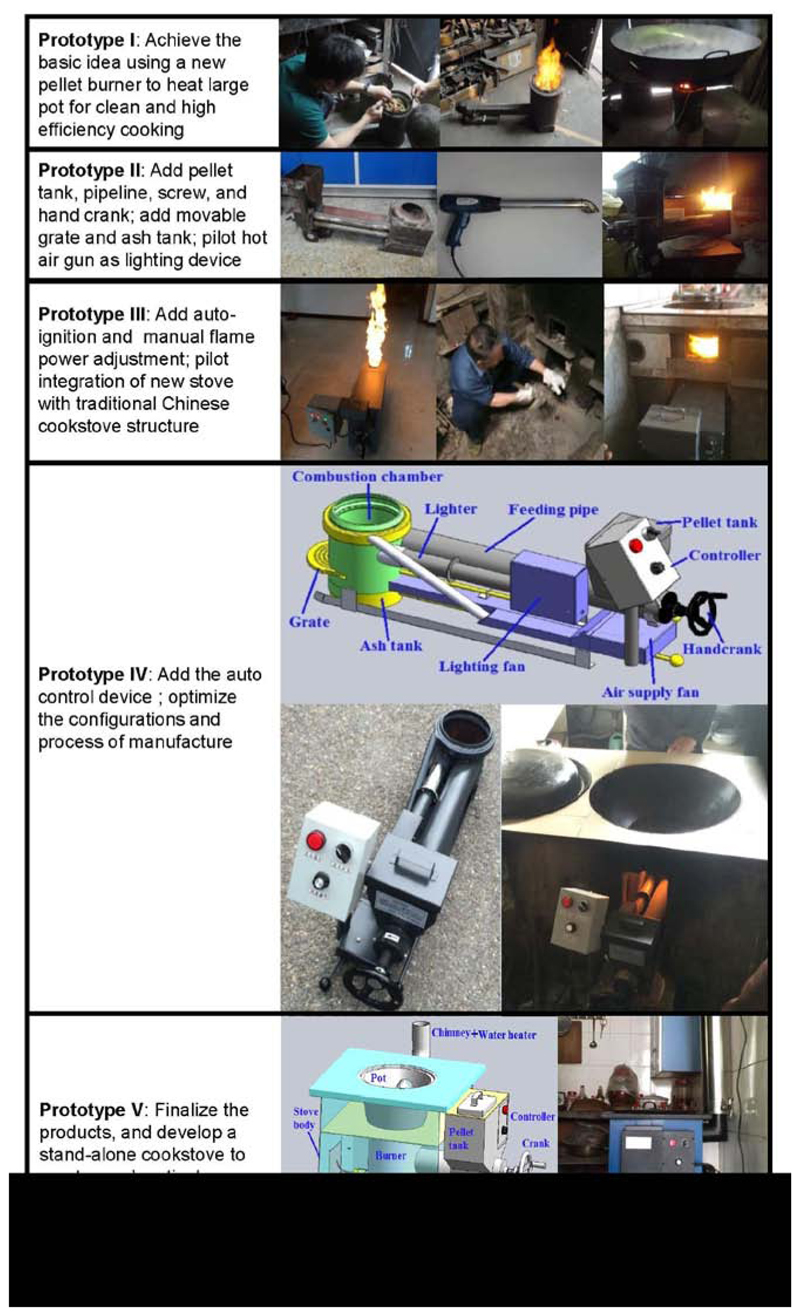

The stove development process yielded five distinct stove prototypes, which are summarized in Figure 1 along with a list of key advances for each prototype. We adopted the method of Technology Readiness Assessment (TRA) to enable consistent, uniform discussions of technical maturity across different prototypes. The TRA examines program concepts, technology requirements, and demonstrated technology capabilities, based on a scale from 1 to 9, with 9 being the most mature technology (DoD., 2011). Estimated Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) for each prototype are described below.

Figure 1. The stove development process: five stove prototypes developed as part of the study, ranging from the proof-of-concept (Prototype I) to commercial scale production readiness (Prototype V).

Prototype I (TRL: 3)

The initial prototype consisted of a single chamber for fuel loading and combustion. Primary and secondary air flow to the chamber was powered by a small electric blower (input power =12W).

Prototype II (TRL: 5)

Prototype II design was adapted to load biomass pellet fuel from a separate chamber, allowing the user to continuously transfer, rather than batch-feed, fuel to the combustion chamber by turning a hand crank. A combustion chamber grate was added to facilitate ash removal by the user and prevent breakage due to slag build-up.

Prototype III (TRL: 6)

To automate fuel ignition for ease, Prototype III incorporated a lighter and electric resistance heating element that heated air at the surface of the biomass pellets in the combustion chamber. Two manual valves were added to the primary and secondary air supply lines to improve the user’s ability to adjust the flame and firepower and thus cook a wider range of foods.

Prototype IV (TRL: 8)

Stove geometry and electric wiring were modified to provide a traditional stove retrofit option for homes and for safety. The placement and functionality of electrical controls were changed to improve stove ergonomics and the user experience. In addition, the manufacturing process was optimized for scaling up production by adopting standard components and simplifying steps in stove assembly.

Prototype V (TRL: 9)

The stove chamber and components were re-configured into a stand-alone stove frame that retained the functionality of Prototype IV. The stand-alone version accommodated user preference for home installation. A modifiable chimney and water tank were added at the flue gas outlet to vent smoke outside of the home and also capture vented heat for hot water provision.

3.3. Stove performance testing in the laboratory

In the laboratory, stove Prototypes IV and V performed the best of the five stove prototypes with respect to thermal efficiency and pollutant emissions. Notably, emissions of PM2.5 were lowest (0.038 ± 0.013g/MJd) for Prototype V, meeting the ISO standard for a Tier 4 stove (ISO, 2012). CO emissions for Prototype V (2.2 ± 1.1g/MJd) performed at a Tier 4 level. The laboratory-measured PM2.5 emissions from the Prototype V (THU semi-gasifier) stove were lower by 39% to 94% than several commercially available semi-gasifier stoves whose performance is reported in the literature (Jetter et al., 2012). The thermal efficiency and CO emissions of the THU semi-gasifier stove were similar to or performed better than most other comparable stoves (Table S3).

The thermal efficiencies of Prototype II and III were lower than the other three stove prototypes (Table 2). This is largely attributable to a smaller size ratio of the pot (diameter=32cm) to combustion chamber, which limited the heat absorbed by the pot during high power cooking. We subsequently reduced the combustion chamber diameter. Doing so, we discovered that the primary air face velocity increased with reduced combustion chamber diameters, likely because the diameter of holes in the ash removal grate, which is also the primary air supply inlet, was unchanged. Meanwhile, it was difficult for the stove user to precisely control the flame by manually adjusting the two valves that controlled primary and secondary air flow. We therefore changed the structure and inlets of the ash removal grate and the combustion chamber and re-designed the flame power adjustment by automating control of the air supply fan flowrate to avoid manual valve adjustment, which resulted in the improved performance of Prototypes IV and V. Adding an insulation layer to the combustion chamber further improved the thermal efficiency of the final prototype (Prototype V) over that of Prototype IV, reaching 41 ±2% and exceeding the standard for a Tier 3 stove according to the ISO IWA performance standards.

Table 2. Thermal efficiency and emissions performance during laboratory testing of five semi-gasifier cookstove prototypes.

| Prototype | Thermal Efficiency (%) Mean ± St Dev | Emission Factors (g/MJda) Mean ± St Dev | ISO Tierb,c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | PM2.5 | CO | |||

| I | 6 | 27 ± 3 | 0.230 ± 0.069 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 2, 2, 4 |

| II | 4 | 16 ± 1 | 0.164 ± 0.044 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1, 3, 4 |

| III | 3 | 18 ± 1 | 0.351 ± 0.019 | 21.2 ± 2.2 | 1, 2, 0 |

| IV | 5 | 25 ± 1 | 0.121± 0.056 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2, 3, 4 |

| V | 10 | 41 ± 2 | 0.038 ± 0.013 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 3, 4, 4 |

CO, carbon monoxide; PM, particulate matter

Mega-joules of energy delivered to the cooking pot; conversion from per-mass emissions multiplied by the caloric heating value of the fuel (= 17.1 MJ/kg) and the thermal efficiency of the stove

International Standards Organization (ISO) International Working Agreement tiered cookstove rating system, values from 0 (worst performance) to 4 (best performance) (ISO, 2012)

First value refers to thermal efficiency tier, second value refers to PM2.5 emissions tier, and third value refers to CO emissions tier

3.4. Field evaluation of stove use and user experience

Users of Prototypes III and IV (n=3) expressed a preference for the prototype stove over the traditional stove for flash-frying food due to its powerful flame. Other advantages noted included cleaner handling of the pelletized fuel compared with wood and a visible reduction in kitchen smoke. Limitations mentioned by users included having to retrofit their traditional stove, inconsistent automated ignition, and frequent breakage the stove’s igniter (i.e., once every 2 to 5 weeks). Additional information on stove user preferences and dislikes, and proposed design or implementation changes, is provided in Table S1.

Among 25 homes that received a Prototype V (i.e., THU) stove and fuel supply in September 2015, 22 homes (88%) reported lighting and using the stove at least once. Among the extended questionnaire respondents (n=14), the stove features identified as most favorable were cleanliness (n=11, 79%) and ease of operation (n=9, 64%). Most reported using the THU semi-gasifier stoves for frying vegetables and meat (n=12, 86%) and making soups (n=9, 64%), which are common cooking methods in rural China.

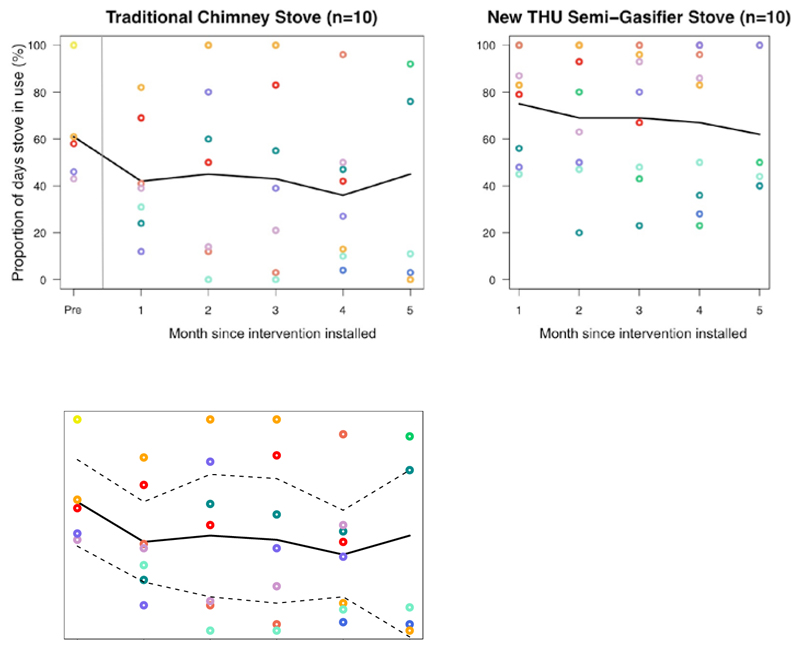

In the 10 homes with stove use monitoring, we observed large between-household and within-household variability in usage patterns for both the traditional and semi-gasifer stove over five months, though average stove use across households remained relatively consistent over time (Figure 2). On average, the THU stoves were used on more days per month than the traditional stoves (68% [95% CI: 43, 93] versus 42% [95% CI: 16, 68]). However, exclusive or near exclusive use of the THU stove was less common: of the 34 total post-intervention household-months contributed by 9 homes, 12 months (35%) contributed by 6 homes were characterized by consistent use of the THU stove and <15% of days of traditional stove use. Use of the THU stove did not fall below 20% of days per month for any single household-month evaluated. Frequent use (>60% of days per month) of both the traditional and THU stoves was observed in 6 household-months (18%) contributed by three homes.

Figure 2.

Average monthly proportion of days the intervention and traditional stoves were in use, pre- and up to 5-months post-intervention, in 10 homes. Circles represent the proportion of daily stove use per month for each household. The solid black lines represent the mean proportion of daily stove use across households in the months since intervention and the dashed black lines indicate the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence intervals around the mean. Different colored circles correspond to different study homes. Homes contributed a different numbers of months to the analysis due to random temperature sensor breakage.

We also observed a small but consistent decrease in THU stove use over time (75%, 69%, and 62% of days in months 1, 3, and 5, respectively). While traditional stove use decreased slightly from pre-intervention (61% of days, n=5 homes) to the first month post-intervention (43% days in use), the monthly days of use remained very consistent over the next five months (43%, 43%, and 45% of days in months 1, 3, and 5, respectively).

On days of use, the THU and traditional stoves were used an average of 1.7 [95% CI: 1.6, 1.8] and 1.6 [95% CI: 1.6, 1.7] times per day, respectively, indicating that after the choice had been made to use the stoves, they contributed to daily cooking to a similar extent. On days when both the traditional and THU stoves were used, they were used for separate meals on 68% of those days.

Stove use monitoring and participant experiences in the 10 homes helped to inform us the shortages of using the stoves in the real rural environment. For instance, the inlet nozzle of the hot water tank was too small and water would spill out when being added, which would be dangerous for the electric devices below. To improve the users’ safety, convenience and acceptance of using the new stoves, we therefore changed the size of inlet nozzle and re-designed the relative positions of hot water tank, wiring port and electric devices in the following batch of products.

3.5. Stove performance testing in homes

On an as-received basis, the THU cookstove reduced PM2.5 and CO emissions (per-energy-delivered basis) by 80% and 50%, respectively, relative to traditional stoves (Table 3). However, the average PM2.5 and CO emissions, on a per-energy-delivered basis, were approximately three times higher than the laboratory-based emissions for the Prototype V stove (Table 2). Emissions of CO2 and NOx, on a per-energy-delivered basis, were higher for the THU stove compared with the traditional stove (SI Section S2), which would be expected, given the more efficient and higher heat combustion achieved by the intervention stove.

Table 3.

Emission factors on a per-fuel, per-task, and per-energy-delivered basis for PM2.5 and CO from traditional chimney stoves burning wood (n=15) and the THU semi-gasifier stoves burning pelletized biomass (n=16), 6 months post-stove installation.

| Pollutant | Traditional Stove Mean ± St Dev(ISO Tier) |

THU Stove Mean ± St Dev(ISO Tier) |

|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 (g/kg-fuel) | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 0.9 ± 0.9 |

| PM2.5 (g/task) | 3.7 ± 3.3 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| PM2.5 (g/MJda) | 0.612 ± 0.457 (1) | 0.123 ± 0.125 (3) |

| CO (g/kg-fuel) | 53 ± 17 | 49 ± 25 |

| CO (g/task) | 88 ± 49 | 31 ± 21 |

| CO (g/MJd) | 14 ± 5 (1) | 7 ± 4 (4) |

CO, carbon monoxide; ISO, International Standards Organization; PM, particulate matter

megajoule delivered on a dry basis

Notably, two households using the THU stoves had particularly high emissions (average emissions factors for PM2.5=3.0 g/kg-dry-fuel and CO=80.4g/kg-dry-fuel; compared with PM2.5=0.6 g/kg-dry-fuel and CO=44.0g/kg-dry-fuel in the other 14 homes). PM2.5 and CO emissions from these two high-emitting homes are strong drivers of the observed difference between field and laboratory emissions tests. When the data from these two homes are removed, the average PM2.5 and CO emission factors for the remaining 14 homes are 1.3 and 1.4 times, respectively, greater than those for the laboratory emission factors. The higher emissions in these two homes were attributable to both a longer lighting phase and user delay when switching from the lighting to burning phase. The auto-ignition controller was adjusted in a later batch of THU stoves (Prototype V) to facilitate more consistent emissions performance regardless of the user (see SI Section S3).

3.6. Stove and fuel cost

The production cost of the Prototype V stove was RMB 1600 (US$230), excluding packaging and transportation (RMB 400, US$58). Material and labor costs associated with small-batch production accounted for up to two-thirds of the cost of the final intervention stove prototype. Production costs could likely be reduced with increased scale of manufacturing. In our study villages, the estimated cost of a new traditional cookstove is approximately RMB 1500 (US$215), with the majority of the cost going towards labor. If produced at a larger scale (i.e., >1000 units), the cost of the THU stoves (Prototype V) should decrease.

In the 16 homes where THU stove emissions and fuel use were measured, daily consumption of biomass pellet fuel by the semi-gasifier stove did not exceed 1kg, and household gross annual cooking fuel consumption for the semi-gasifier stove would be estimated to not exceed 0.5t (calculated under the assumption that the same amount of fuel is used all 365 days of the year), representing a ~80% reduction in fuel consumption relative to the daily average fuel use observed with traditional wood-burning cookstoves alone (Shan et al., 2014; Carter et al., 2016). Rural homes may save time and effort that was previously spent collecting firewood, a benefit mentioned by many stove users and their family members during interviews (Table S1). If the processed biomass fuel were produced at a village-level factory, we estimate that a household’s annual expenditure on pelletized fuel for cooking would be ~US$25 or less, roughly equivalent with daily cooking with LPG for one month (Shan et al., 2016).

4. Discussion

Field observations and interactions with stove users frequently inform stove selection (Loo et al., 2015) and intervention study design (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2012). User-centered design has also led to diversification of stove installation options in the field (Thacker et al., 2017) and influenced design and implementation of policies to promote cookstoves (Lambe and Atteridge, 2012). However, early integration of user needs and preferences to constrain core technical design, as we did here, has not been presented at a similar level of detail for past stove development.

Recent systematic reviews indicate that a key limitation of past and more recent stove programs was that the stove design was insufficiently engineered to meet the needs of households most likely to adopt the technology (Barnes et al., 1994; Lewis and Pattanayak, 2012; Rehfuess et al., 2014). An early stove program in Kenya, for example, failed because cooks lacked the time and tools to chop the small wood pieces required for the stove’s combustion chamber (Openshaw et al., 1982). Three decades later, the stove intervention in a large randomized trial in Malawi was limited by poor field emissions performance (Wathore et al., 2017) and infrequent use (Mortimer et al., 2016). Conversely, stove designs that meet household preferences may not sufficiently improve efficiency and reduce air pollution emissions. For example, China's National Improved Stove Program disseminated biomass chimney stoves to over a billion Chinese residents in the 1980s and 1990s (Smith et al., 1993). The stoves were well liked and replaced traditional stoves and open fires used at the time, but lacked the engineering design to sufficiently reduce air pollution emissions and kitchen concentrations (Zhou et al, 2006; Edwards et al., 2007).

The ultimate stove design presented here achieved higher thermal efficiency and lower emissions than many biomass cookstoves available in China (Tryner et al, 2014; Shen et al., 2015). At the same time, we obtained information from village homes on relevant functional considerations including household size (to inform pot size), cooking frequency and duration (to inform combustion chamber capacity and fuel feeding method), cooking methods and foods (to inform the range of flame power), and characteristics of local available fuels (to inform the method of ash removal). Input from household cooks early in the design process made it possible to re-engineering the stove multiple times to meet our design criteria and improve users’ experience with a new technology (e.g. automated ignition and single knob flame power adjustment). With each substantial design modification, we re-evaluated stove thermal efficiency and pollutant emissions to determine whether an improvement in usability compromised performance. Conversely, we consulted users to learn whether technological changes to increase thermal efficiency and lower pollutant emissions made stove operation more difficult.

Repeated field-based evaluations led to incorporation of numerous desirable features into the stove design, including the fuel loading apparatus, auto-ignition, flame adjustment, the stand-alone frame, and the heat-recovery water tank, which all arose as a direct result of observation of or extended interaction with household cooks.

Regular field-based data collection efforts also brought to light limitations of the stove design and barriers to sustained use and displacement of traditional stoves and fuels. For example, the forced draft semi-gasifier design and automated features of the stove rely on electricity. Although >98% of households in China have access to electricity, the potential for brief electrical outages or a desire to limit electricity consumption and expense might result in continued collection of firewood and use of traditional cookstoves that do not require electricity. Several of the advanced features of the final intervention stove (Prototype V) were desirable—e.g. automated ignition, flame/power adjustment—but increased design complexity. With each stove prototype tested, there was a need for consistent, though manageable, stove repairs, and part replacement. While it is unrealistic to eliminate the need for regular stove maintenance, our experience suggests that the development of more advanced cookstoves, such as semi-gasifiers, should be coupled with development and implementation of robust operation and maintenance plans.

The household energy intervention package included a semi-gasifier cookstove and a pelletized biomass fuel. It is beyond the scope of this specific study to address the production of a reliable supply of pelletized biomass, and the feasibility of developing this energy supply at scale in rural China has been discussed in greater detail elsewhere (Shan et al., 2016). However, the importance of a reliable fuel supply should not be overlooked. Future studies that evaluate the technical, environmental, economic, and political factors that influence the production of pelletized biomass would be very useful. Given the regional and geographic variability throughout China, studies designed to evaluate biomass utilization at local and regional scales might provide the most impactful information.

A limitation of the iterative stove design approach we presented is the small number of observations that may be obtained at any given stage in the design process. Despite high rates of stove uptake and evidence of adoption, the results presented here suggest intervention stoves were not fully displacing traditional stoves and that intervention stove use may decline with longer term follow-up. Of note, we observed that on days when both traditional and intervention stoves were used, they were often used separately. This observation suggests that the capabilities of the intervention stove were preferred for some types of cooking practices but not for others. Future studies designed to monitor long-term use of the intervention stoves and to identify patterns and predictors of complete, or near-complete, traditional stove displacement are warranted.

Conclusions

The unique features of the particular semi-gasifier, biomass cookstove discussed here need not be directly transferable to other regions in China. Rather, the user-centered, iterative engineering design process presented could be replicated in other provinces and regions to identify optimal stove design that is responsive to the local context. Stove designs (Tryner et al., 2014 and 2016) that over-emphasize technical performance early in the stove development process limit the extent to which user input obtained later in the process—if sought—can lead to stove design modification. The user-centered and iterative engineering design approach we present prioritized local users’ preferences and aspirations, and sought to combine user input with high technical performance. Our results suggest that valuable engineering insights are gained in the early stages of stove design through targeted field-based data collection that yield information unattainable in the laboratory. These field-based data collection efforts are not intended to replace larger scale studies designed to evaluate stove performance, stove adoption and uptake, and long-term health and environmental impacts of stove programs at a population level. Instead, we transparently present the design criteria and lab- and field-based data collection that inform critical decisions in the stove engineering design process. The framework for stove engineering design we present may be used as a model for stove engineers and practitioners and provide more comprehensive information to policy-makers making decisions about household energy technologies and initiatives.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A multi-functional, semi-gasifier cooking and water-heating stove was developed.

An iterative stove design process integrated technological performance testing with well-documented user preferences and experiences.

Prototype stove performance in the laboratory, test homes, and actual homes demonstrated a user-friendly, robust, semi-gasifier cookstove with high thermal efficiency and low air pollutant emissions.

Acknowledgement

We thank our study participants and field staff. Supports for this study were provided by the Chinese National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (#2013BAC17B02),the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results Program (#83542201), the Wellcome Trust grant (Grant No. 103906/Z/14/Z),the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#51521005), and the UN Foundation Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves.

References

- Agarwal B. Diffusion of rural innovations: some analytical issues and the case of wood-burning stoves. World Development. 1983;11(4):359–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ahiduzzaman M, Islam AS. Development of biomass stove for heating up die barrel of rice husk briquette machine. Procedia Engineering. 2013;56:777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PS, Reed TB, Wever PW. Micro-Gasification: What it is and why it works. Boiling Point. 2007;53(3):35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JEM, Kohlin G, Persson R, Shepherd G. Fuelwood Revisited: What has changed in the last decade? (No CIFOR Occasional Paper 39. CIFOR; Bogor, Indonesia: 2003. p. viii-35. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DF, Openshaw K, Smith KR, Van der Plas R, Mundial B. What makes people cook with improved biomass stoves? A comparative international review of stove programs World Bank Technical Paper Number 242, Energy Series. 1994

- Bond TC, Doherty SJ, Fahey DW, Forster PM, Berntsen T, DeAngelo BJ, Flanner MG, Ghan S, Kärcher B, Koch D, Kinne S. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 2013;118(11):5380–5552. [Google Scholar]

- Bonjour S, Adair-Rohani H, Wolf J, Bruce NG, Mehta S, Prüss-Ustün A, Lahiff M, Rehfuess EA, Mishra V, Smith KR. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980-2010. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013;121(7):784. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Wang Y, Zhao B, Wang S, Chang X, Hao J. The impact of the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan on PM2.5 concentrations in Jing-Jin-Ji region during 2012-2020. Science of The Total Environment. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.188. (Available Online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EM, Shan M, Yang X, Li J, Baumgartner J. Pollutant emissions and energy efficiency of Chinese gasifier cooking stoves and implications for future intervention studies. Environmental Science &Technology. 2014;48(11):6461–6467. doi: 10.1021/es405723w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EM, Archer-Nicholls S, Ni K, Lai AM, Niu H, Secrest MH, Sauer SM, Schauer JJ, Ezzati M, Wiedinmyer C, Yang X. Seasonal and diurnal air pollution from residential cooking and space heating in the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016;50(15):8353–8361. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, et al. Adoption and use of a semi-gasifier cooking and water heating stove and fuel intervention in the Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Research Letters [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RD, Liu Y, He G, Zheng Y, Jonathan S, John P, Kirk RS. Household CO and PM measured as part of a review of China’s National Improved Stove Program. Indoor air. 2007;17(3):189–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Baumgartner JC. Household energy and health: where next for research and practice? The Lancet. 2016;389(10065):130–132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Kammen DM. Household energy, indoor air pollution, and health in developing countries: knowledge base for effective interventions. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 2002;27(1):233–270. [Google Scholar]

- Febriansyah H, Setiawan AA, Suryopratomo K, Setiawan A. Gama Stove: Biomass Stove for Palm Kernel Shells in Indonesia. Energy Procedia. 2014;47:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Liao W. Legislation, plans, and policies for prevention and control of air pollution in China: achievements, challenges, and improvements. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2016;112(2):1549–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, Brauer M, Burnett R, Casey D, Coates MM, Cohen A, Delwiche K. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–2323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Beard M, Clifford MJ, Watson MC. An evaluation of a biomass stove safety protocol used for testing household cookstoves, in low and middle-income countries. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2016;33:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gill J. Improved stoves in developing countries: A critique. Energy Policy. 1987;15(2):135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. 2016 progress report on Clean Cooking Key to Achieving Global Development and Climate Goals. 2016

- ISO International Working Agreement. IWA 11:2012: Guidelines for evaluating cookstove performance. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. The Water Boiling Test Version 423 Cookstove emissions and efficiency in a controlled laboratory setting. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jetter J, Zhao Y, Smith KR, Khan B, Yelverton T, DeCarlo P, Hays MD. Pollutant emissions and energy efficiency under controlled conditions for household biomass cookstoves and implications for metrics useful in setting international test standards. Environmental Science &Technology. 2012;46(19):10827–10834. doi: 10.1021/es301693f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Chiang RA. Quantitative guidance for stove usage and performance to achieve health and environmental targets. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2015;123(8):820. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kshirsagar MP, Kalamkar VR. A comprehensive review on biomass cookstoves and a systematic approach for modern cookstove design. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2014;30:580–603. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Kumar S, Tyagi SK. Design, development and technological advancement in the biomass cookstoves: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2013;26:265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lambe F, Atteridge A. Putting the cook before the stove: a user-centred approach to understanding household energy decision-making-A case study of Haryana State, northern India Working Paper 2012-03; Stockholm Environment Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JJ, Pattanayak SK. Who adopts improved fuels and cookstoves? A systematic review. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(5):637. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo JD, Hyseni L, Ouda R, Koske S, Nyagol R, Sadumah I, Bashin M, Sage M, Bruce N, Pilishvili T, Stanistreet D. User Perspectives of Characteristics of Improved Cookstoves from a Field Evaluation in Western Kenya. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(2):167. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manibog FR. Improved cooking stoves in developing countries: problems and opportunities. Annual Review of Energy. 1984;9(1):199–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer K, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, Malava J, Katundu C, Weston W, Wang D. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the Cooking and Pneumonia Study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;389(10065):167–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Sambandam S, Pillarisetti A, Jack D, Mukhopadhyay K, Balakrishnan K, Vaswani M, Bates MN, Kinney PL, Arora N, Smith KR. Cooking practices, air quality, and the acceptability of advanced cookstoves in Haryana, India: an exploratory study to inform large-scale interventions. Global Health Action. 2012;5:1–13. doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.19016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Energy Administration of China 2016 Planning of Biomass Energy Development for China’s 13th Five-Year Plan. http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/auto87/201612/t20161205_2328.htm?keywords=

- National Development and Reform Commission of People’s Republic of China (NDRC) Medium and Long-Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy in China (Abbreviated Version, English Draft), Issued in September 2007. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Ni K, Carter E, Schauer JJ, Ezzati M, Zhang Y, Niu H, Lai AM, Shan M, Wang Y, Yang X, Baumgartner J. Seasonal variation in outdoor, indoor, and personal air pollution exposures of women using wood stoves in the Tibetan Plateau: Baseline assessment for an energy intervention study. Environment International. 2016;94:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw K. The development of improved cooking stoves for urban and rural households in Kenya. Report of the Beijer Institute Beijer Institute/Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; Stockholm: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Raman P, Ram NK, Gupta R. Development, design and performance analysis of a forced draft clean combustion cookstove powered by a thermo electric generator with multi-utility options. Energy. 2014;69:813–825. [Google Scholar]

- Reed TB, Larson R. A wood-gas stove for developing countries In Developments in Thermochemical Biomass Conversion. Springer; Netherlands: 1997. pp. 985–993. [Google Scholar]

- Rehfuess EA, Puzzolo E, Stanistreet D, Pope D, Bruce NG. Enablers and barriers to large-scale uptake of improved solid fuel stoves: a systematic review. Environmental Health Perspectives (Online) 2014;122(2):120. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden CA, Bond TC, Conway S, Pinel ABO, MacCarty N, Still D. Laboratory and field investigations of particulate and carbon monoxide emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves. Atmospheric Environment. 2009;43(6):1170–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mercado I, Canuz E, Smith KR. Temperature dataloggers as stove use monitors (SUMs): Field methods and signal analysis. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2012;47:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mercado I, Masera O, Zamora H, Smith KR. Adoption and sustained use of improved cookstoves. Energy Policy. 2011;39(12):7557–7566. [Google Scholar]

- Shan M, Wang P, Li J, Yue G, Yang X. Energy and environment in Chinese rural buildings: Situations, challenges, and intervention strategies. Building and Environment. 2015;91:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Shan M, Li D, Jiang Y, Yang X. Re-thinking China’s densified biomass fuel policies: Larger or small scale? Energy Policy. 2016;93:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Chen Y, Xue C, Lin N, Huang Y, Shen H, Wang Y, Li T, Zhang Y, Su S, Huangfu Y. Pollutant emissions from improved coal-and wood-fuelled cookstoves in rural households. Environmental science & technology. 2015;49(11):6590–6598. doi: 10.1021/es506343z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Gu S, Huang K, Qiu D. One hundred million improved cookstoves in China: How was it done? World Development. 1993;21(6):941–961. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, Thompson LM, Balmes J, Diaz A, Arana B, Bruce N. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker KS, Barger KM, Mattson CA. Balancing technical and user objectives in the redesign of a Peruvian cookstove. Development Engineering. 2017;2:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson J. Kicking the coal habit. Nature. 2008:388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tryner J, Tillotson JW, Baumgardner ME, Mohr JT, DeFoort MW, Marchese AJ. The effects of air flow rates, secondary air inlet geometry, fuel type, and operating mode on the performance of gasifier cookstoves. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016;50(17):9754–9763. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryner J, Willson BD, Marchese AJ. The effects of fuel type and stove design on emissions and efficiency of natural-draft semi-gasifier biomass cookstoves. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2014;23:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Defense. Technology Readiness Assessment (TRA) Guidance. 2011 April [Google Scholar]

- Urmee T, Gyamfi S. A review of improved cookstove technologies and programs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2014;33:625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Li K, Li H, Bai D, Liu J. Research on China’s rural household energy consumption-Household investigation of typical counties in 8 economic zones. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017;68:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wathore R, Mortimer K, Grieshop AP. In-use emissions and estimated impacts of traditional, natural-and forced-draft cookstoves in rural Malawi. Environmental Science & Technology. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Smith KR, Ma Y, Ye S, Jiang F, Qi W, Liu P, Khalil MAK, Rasmussen RA, Thorneloe SA. Greenhouse gases and other airborne pollutants from household stoves in China: a database for emission factors. Atmospheric Environment. 2000;34(26):4537–4549. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Jin Y, Liu F, Cheng Y, Liu J, Kang J, He G, Tang N, Chen X, Baris E, Ezzati M. Community effectiveness of stove and health education interventions for reducing exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in four Chinese provinces. Environmental Research Letters. 2006;1(1):014010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.