Abstract

Background

Adjunctive corticosteroids are widely used to treat HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis despite limited data supporting their safety and efficacy.

Methods

We conducted a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in HIV-positive adults (≥18 years) with tuberculous meningitis in Vietnam and Indonesia. Participants were randomized to a 6-8 week tapering course of either dexamethasone or placebo in addition to 12 months antituberculosis chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was death from any cause over 12 months from randomization.

Results

520 adults were randomly assigned to receive either dexamethasone (n=263) or placebo (n=257). The median age was 36 years, 255/520 (49.0%) had never received anti-retroviral therapy, and 251/484 (51.9%) had a baseline CD4 count of ≤50 cells/mm3. Five participants were lost to follow up and 6 withdrew. Over 12 months of follow-up there were 116/263 (44.1%) deaths in the dexamethasone arm and 126/257 (49.0%) deaths in the placebo arm (hazard ratio 0.85, 95% confidence interval 0.66-1.10; P=0.22). Pre-specified analysis did not reveal a sub-group that clearly benefited from dexamethasone. Secondary outcomes occurred with similar frequency across both treatment arms, including the incidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. The numbers of participants with at least one serious adverse event were similar between dexamethasone (192/263 [73.0%]) and placebo (194/257 [75.5%]) arms (P=0.52).

Conclusions

We did not establish a benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis, either on survival or any other secondary endpoint. (Funded by the Wellcome Trust; ClinicalTrials.gov registration NCT03092817.)

Tuberculous meningitis is a serious complication caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is especially common in HIV-positive individuals, in whom mortality can exceed 50% despite effective anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy.1–4

Death and neurological sequelae from tuberculous meningitis are associated with intracerebral inflammation.5 Attempts to improve outcomes by controlling inflammation with adjunctive corticosteroids were first reported in 1952.6 In 2004, a trial in 545 Vietnamese adolescents and adults showed that adjunctive dexamethasone reduced mortality from tuberculous meningitis,3 although the benefit was uncertain in the 98 HIV-positive people enrolled into the trial.

The number of HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis ever enrolled into trials of adjunctive corticosteroids remains at 98. A systematic review and meta-analysis of corticosteroids for tuberculous meningitis concluded that their benefit in HIV-positive individuals was uncertain.7 However, many treatment guidelines recommend corticosteroids for everyone with tuberculous meningitis, regardless of HIV status.8–10 Trials of adjunctive corticosteroids for HIV-positive individuals with other forms of tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections highlight the potential risks of this approach. Corticosteroids have been associated with an increased risk of HIV-associated malignancies, especially Kaposi sarcoma,11,12 and in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis adjunctive dexamethasone was associated with increased death, disability, and adverse events.13

Adjunctive corticosteroids are widely used for the treatment of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis, but with little evidence for their safety or efficacy. We therefore conducted a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial to determine if adjunctive dexamethasone reduced mortality in HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis.

Methods

The trial methodology, conduct, and analysis are described in the published protocol14 and analysis plan and available at nejm.org.15 The trial was designed and delivered by the investigators, supported by Oxford University Clinical Research Unit Clinical Trials Units in Vietnam and Indonesia. All authors vouch for the data and analysis. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03092817).

Settings and study population

We recruited participants from the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, and Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital for Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and from Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo National Reference Hospital, and Persahabatan National Respiratory Referral Hospital, in Jakarta, Indonesia. Participants were ≥18 years old, HIV-positive (either newly or previously diagnosed) with a clinical diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis (at least 5 days of meningitis symptoms and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities) with anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy either planned or started by the attending physician. Participants were subsequently classified as having definite, probable, or possible tuberculous meningitis, following published criteria (Supplementary table S1).16 Patients were ineligible if another brain infection was suspected, if >6 consecutive days of anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy or >3 consecutive days of systemic corticosteroids were received before enrolment, or if systemic corticosteroids were considered mandatory or contraindicated for any reason.

Study oversight

Written informed consent to enter the trial was obtained from all participants or a relative if they were incapacitated. If capacity returned, consent from the participant was obtained. Trial approvals were obtained from local and national ethics and regulatory authorities in Vietnam and Indonesia and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee in the UK (Supplementary Text S1). An independent data monitoring committee reviewed data at 6-monthly intervals until 303 participants were randomized and annually thereafter.

Randomization and study groups

Randomization to dexamethasone or placebo was 1:1, with stratification by participating site and modified Medical Research Council (MRC) tuberculous meningitis severity grade.17 Participants in grade I had a Glasgow Coma Score of 15 (possible range, 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating better status) with no focal neurologic signs; grade II participants had a score of either 11 to 14, or 15 with focal neurological signs; and grade III participants had a score of 10 or less. The randomization list was computer-generated based on random permuted blocks with block size 4 and 6 (probability 0.75 and 0.25). Randomization of participants was performed by trained clinical staff using a web-based software, with 24-hour availability.

Study treatments

All participants received standard-of-care anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy and antiretroviral therapy (ART) according to national guidelines (Supplementary Text S2). In ART-naive participants, ART was started approximately 6–8 weeks after starting anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy. All participants were randomized to dexamethasone or placebo, termed ‘study drug’, following the regimen previously shown to reduce tuberculous meningitis mortality (Supplementary Text S3).3 Blinded study drug packages (fully made-up and labelled treatment packs) contained either dexamethasone or identical placebo. All participants and investigators were blinded to study drug allocation. Participants with grade II or III disease received intravenous treatment for four weeks (0.4 mg per kilogram per day for week 1, 0.3 mg per kilogram per day for week 2, 0.2 mg per kilogram per day for week 3, and 0.1 mg per kilogram per day for week 4) and then oral treatment for four weeks, starting at 4 mg per day and decreasing by 1 mg each week. Participants with grade I disease received three weeks of intravenous therapy (0.3 mg per kilogram per day for week 1, 0.2 mg per kilogram per day for week 2, and 0.1 mg per kilogram per day for week 3) and then oral treatment for three weeks, starting at 3 mg per day and decreasing by 1 mg each week. Adherence to study medication was ensured with the use of supervised drug intake for inpatients, encouraged by detailed instructions at discharge, and medication compliance checks at follow-up visits or phone calls.

Outcome assessments

The primary endpoint was all-cause death over 12 months from randomization. Secondary endpoints were neurological disability (modified Rankin score 3-5; Table S2) at 12 months, neurological immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) over the first 6 months, and the following endpoints assessed over 12 months from randomization: first new neurological event or death, new acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining event or death, HIV-associated malignancy, use of open-label corticosteroid treatment for any reason, requirement for shunt surgery, and serious adverse events.15

Clinical assessments and laboratory investigations

Participants underwent trial clinical assessments at baseline, at days 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 30, and monthly until month 12. Assessment included Glasgow coma score, modified MRC severity grade, and details of clinical and adverse events and other interventions. Participants were monitored daily whilst in hospital and serious adverse events were reported to local and national regulators. In participants for whom systemic corticosteroids were considered necessary by the treating clinician after randomization, study drug was discontinued (with doses already received remaining blinded) and corticosteroids commenced.

Baseline blood tests included full blood count, sodium, potassium, creatinine, alanine transaminase (ALT), bilirubin, hepatitis B and C, CD4 count and HIV viral load. Lumbar cerebrospinal fluid was sampled at baseline and tested for pyogenic bacteria (Gram stain and culture) and cryptococcal antigen. At least 6mls of cerebrospinal fluid (if available) was used for Ziehl-Neelsen smear microscopy, either Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra, and mycobacterial culture (mycobacteria growth indicator tube [MGIT]) following standard procedures.18 Phenotypic drug susceptibility testing was performed using a BACTEC MGIT SIRE kit (Becton, Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).18

Statistical analyses

Based on previous trials,3,19 we assumed a target hazard ratio (HR) of 0.69, and a 40% 9-month mortality. We estimated that 520 HIV-positive patients with tuberculous meningitis would be required to achieve 80% power at a two-sided 5% significance level, and allowing for 5% loss-to-follow-up.

Unless otherwise stated, the analysis followed a pre-specified published plan (Supplementary Text S4 and S5).15 Briefly, intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed for the primary and secondary endpoints. The intention-to-treat population included all randomized participants, even if no study drug was received. The per-protocol population included all randomized participants excluding those that subsequently did not meet the inclusion criteria or had exclusion criteria at enrolment, those with a final diagnosis other than tuberculous meningitis, those who received either <7 days of randomized study drug or <30 days of anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy for reasons other than death.

Baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment arm for intention-to-treat and per-protocol populations. The primary analysis was a Cox proportional hazards regression model with treatment as the only covariate.15 We tested for heterogeneity by six pre-specified subgroups: MRC severity grade, diagnostic category, leukotriene A4 hydrolase genotype (Supplementary Text S6), anti-tuberculosis drug resistance, ART status at enrolment, and CD4 count. We repeated analyses adjusted for MRC severity grade. Neurological disability at 12 months was compared using proportional odds logistic regression. All other secondary outcomes were compared via Cox proportional hazards models and cumulative event probabilities (nonparametric Kaplan-Meier, and Aalen-Johansen estimates in case death was a competing risk). No correction for multiple testing was made, and confidence intervals should not be interpreted as results from hypothesis tests. The number of individuals with any serious adverse event was compared by chi-squared test. Data were analyzed using the program R (version 4.1.1; R Core Team, 2021).20

Results

Study population

From May 25, 2017, to April 29, 2021, 520 adults were randomly assigned to receive either dexamethasone or placebo. Eleven participants (2.1%) did not complete 12 months follow-up due to study withdrawal (six participants) or loss-to-follow-up (five participants). 33 participants were excluded for the per-protocol population (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screening, enrollment and randomization.

Among the patients in the intention-to-treat population, in the dexamethasone arm, 2 were lost-to-follow-up, and 5 withdrew from the study before 12 months, whereas in the placebo arm 3 were lost-to-follow-up, and 1 withdrew from the study before 12 months. TB=tuberculosis.

Baseline characteristics

Participant characteristics at baseline were balanced between the study arms (Tables 1 and S3) and were broadly representative of populations of persons with tuberculous meningitis (Table S4). The median age of participants was 36 years (interquartile range [IQR] 30-41). Disease was generally mild or moderate (447/520 [86.0%] grade 1 or 2). 186/520 (35.8%) participants were newly diagnosed with HIV, 255/520 (49.0%) were ART-naïve, and 251/484 (51.9%) had CD4 counts ≤50 per mm3. The enrolment anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy regimens included rifampin in 478/514 (93.0%), isoniazid in 485/514 (94.4%), pyrazinamide in 471/514 (91.6%) and ethambutol in 364/514 (70.8%). Multi-drug resistance was identified in 16 participants (10 dexamethasone; 6 placebo), and treated following national guidelines.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics in the intention-to-treat population.

| Characteristic | All participants (N=520) | Dexamethasone (N=263) | Placebo (N=257) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Summary statistic | N | Summary statistic | N | Summary statistic | |

| Age (years) | 520 | 36 (30, 41) | 263 | 36 (29, 41) | 257 | 36 (30, 42) |

| Sex – male | 520 | 396 (76.2%) | 263 | 208 (79.1%) | 257 | 188 (73.2%) |

| Diagnostic category | 520 | 263 | 257 | |||

| - Definite TBM | 212 (40.8%) | 108 (41.1%) | 104 (40.5%) | |||

| - Probable TBM | 253 (48.7%) | 129 (49.1%) | 124 (48.3%) | |||

| - Possible TBM | 52 (10.0%) | 24 (9.1%) | 28 (10.9%) | |||

| - Not TBM | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| - Unknown* | 3 (0.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |||

| Modified MRC grade | 520 | 263 | 257 | |||

| - Grade I | 196 (37.7%) | 99 (37.6%) | 97 (37.7%) | |||

| - Grade II | 251 (48.3%) | 125 (47.5%) | 126 (49.0%) | |||

| - Grade III | 73 (14.0%) | 39 (14.8%) | 34 (13.2%) | |||

| Glasgow coma score (/15) | 515 | 14 (12, 15) | 259 | 14 (12, 15) | 256 | 14 (12, 15) |

| CSF microbiological tests | ||||||

| - Positive Ziehl-Neelsen stain | 504 | 100 (19.8%) | 255 | 52 (20.4%) | 249 | 48 (19.3%) |

| - Positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF | 401 | 107 (26.7%) | 204 | 53 (26%) | 197 | 54 (27.4%) |

| - Positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF Ultra† | 113 | 46 (40.7%) | 56 | 22 (39.3%) | 57 | 24 (42.1%) |

| - Positive mycobacterial culture | 508 | 148 (29.1%) | 256 | 77 (30.1%) | 252 | 71 (28.2%) |

| ART status at enrolment | 465 | 237 | 228 | |||

| - ART naïve | 255 (49.0%) | 133 (50.6%) | 122 (47.5%) | |||

| - >3 months of ART | 104 (20.0%) | 46 (17.5%) | 58 (22.6%) | |||

| - Undetermined ART duration | 106 (20.4%) | 58 (22.1%) | 48 (18.7%) | |||

| Enrolment CD4 count (per mm3) | 484 | 244 | 240 | |||

| - ≤50 | 251 (51.9%) | 126 (51.6%) | 125 (52.1%) | |||

| -51-100 | 89 (18.4%) | 45 (18.4%) | 44 (18.3%) | |||

| -101-200 | 71 (14.7%) | 36 (14.8%) | 35 (14.6%) | |||

| ->200 | 73 (15.1%) | 37 (15.2%) | 36 (15.0%) | |||

For three cases with unknown diagnostic category (2 in dexamethasone arm, 1 in placebo arm), clinical criteria for tuberculous meningitis diagnosis were met,16 however the total diagnostic score was <6.

Xpert Ultra availability varied between sites and over time, but only became more widely available for the last 12 months of the study, hence its relatively restricted use.

Results given for sub-group with positive mycobacterial culture on baseline CSF. N = number of patients included in that statistic. Summary statistic = the median (1st and 3rd quartile) value for continuous data, and the number and frequency (%) of patients with the characteristic for categorical data. Definite TBM = positive acid-fast bacilli on CSF Ziehl-Neelsen stain, or positive CSF GeneXpert test, or positive CSF mycobacterial culture. Probable or possible TBM defined following uniform case definition.16 Confirmed non-TBM = microbiologically confirmed other brain infection. Confirmed additional brain infection includes positive CSF India Ink stain, or CSF cryptococcal antigen, or positive blood cryptococcal antigen, or positive CSF bacterial Gram stain, or positive CSF bacterial culture, or positive CSF viral or helminth PCR test. The ART status of a patient was ‘missing’ if the ART status of a patient was unknown, of if these data were missing. The ART status of a patient was undetermined if a patient was on ART treatment but distinction between ≤3 months of ART, and >3 months of ART, could not be made due to limited date information. ART=antiretroviral therapy. CSF=cerebrospinal fluid. MDR=multi-drug resistant. MRC=Medical Research Council. TBM=tuberculous meningitis. Xpert=Gene Xpert MTB/RIF.

Primary outcome

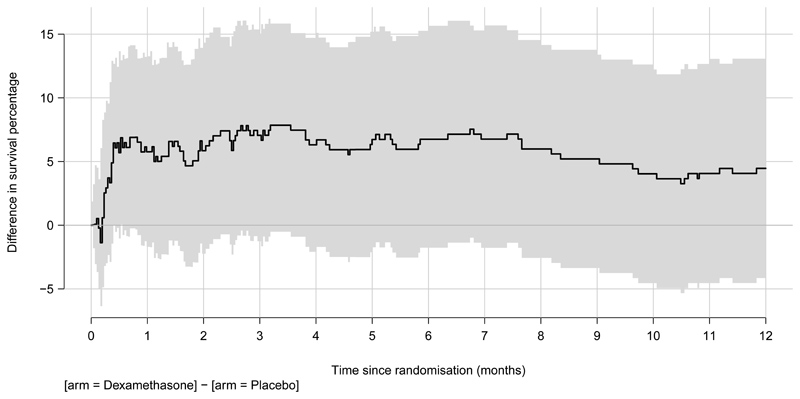

There were 116/263 (44.1%) observed deaths in the dexamethasone arm and 126/257 (49.0%) deaths in the placebo arm (HR 0.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.66-1.10; P=0.22) (Figures 2A and 2B; Table 2). Similar results were observed when adjusted for MRC severity grade (Table S5). Heterogeneity of effect was not observed by any pre-specified sub-group in the intention-to-treat (Table 2, Figures S2-8) and the per-protocol populations (Tables S5-6; Figure S9).

Figure 2.

A. Death from any cause over the first 12 months after randomization for intention-to-treat population

Colored shading represents 95% confidence intervals

B. Differences in survival between arms for the intention-to-treat population

Shading represents 95% confidence intervals

Table 2. Analysis of primary outcome and pre-specified sub-groups in the intention-to-treat population.

| No. of deaths | Hazard ratio (95% CI); P value | Test for proportional hazards | P-value for heterogeneity* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone (N=263) | Placebo (N=257) | ||||

| Intention-to-treat population | 116/263 | 126/257 | 0.85 (0.66, 1.10); P=0.22 | 0.36 | |

| Modified MRC grade: | |||||

| - Grade I | 22/99 | 28/97 | 0.72 (0.41, 1.25); P=0.24 | 0.15 | 0.63 |

| - Grade II | 60/125 | 68/126 | 0.82 (0.58, 1.16); P=0.27 | 0.30 | |

| - Grade III | 34/39 | 30/34 | 1.03 (0.63, 1.69); P=0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Diagnostic category | |||||

| - Definite TBM | 48/108 | 49/104 | 0.90 (0.61-1.35); P=0.62 | 0.54 | 0.15 |

| - Probable TBM | 61/129 | 61/124 | 0.91 (0.64-1.30); P=0.61 | 0.17 | |

| - Possible TBM | 5/24 | 15/28 | 0.34 (0.12-0.94); P=0.04 | 0.08 | |

| Leukotriene A4 hydrolase genotype# | |||||

| - TT | 12/25 | 11/26 | 1.06 (0.47, 2.41); P=0.88 | 0.17 | 0.40 |

| - CT | 49/117 | 59/114 | 0.72 (0.49, 1.05); P=0.09 | 0.25 | |

| - CC | 38/84 | 36/80 | 1.04 (0.66, 1.63); P=0.88 | 0.64 | |

| Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance~ | |||||

| - MDR or rifampin mono-resistant | 7/10 | 5/6 | 0.66 (0.21, 2.11); P=0.48 | 0.92 | 0.15 |

| - Isoniazid resistant non-MDR | 6/14 | 13/20 | 0.56 (0.21, 1.49); P=0.25 | 0.76 | |

| - No or other resistance | 22/52 | 13/45 | 1.58 (0.79, 3.13); P=0.19 | 0.37 | |

| ART status at enrolment | |||||

| - ART naïve | 64/133 | 64/122 | 0.85 (0.60, 1.21); P=0.37 | 0.20 | 0.91 |

| - >3 months of ART | 20/46 | 26/58 | 0.96 (0.54, 1.72); P=0.89 | 0.83 | |

| - Undetermined ART duration | 19/58 | 19/48 | 0.80 (0.42, 1.51); P=0.49 | 0.95 | |

| Enrolment CD4 count (per mm3) | |||||

| - ≤50 | 67/126 | 67/125 | 0.96 (0.69, 1.35); P=0.83 | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| -51-100 | 12/45 | 19/44 | 0.52 (0.25, 1.06); P=0.07 | 0.11 | |

| -101-200 | 14/36 | 13/35 | 1.04 (0.49, 2.22); P=0.91 | 0.89 | |

| ->200 | 11/37 | 15/36 | 0.70 (0.32, 1.52); P=0.36 | 0.20 | |

Heterogeneity was tested by a Cox regression model that includes an interaction between treatment effect and subgroup.

Rationale for Leukotriene A4 hydrolase genotype sub-group provided in Supplementary Text S6.

Results are given for a sub-group with positive mycobacterial culture on baseline cerebrospinal fluid. The primary endpoint was death from any cause over the first 12 months after randomization, i.e., time from randomization to death, over the first 12 months of follow-up. This table reports the results from the Cox proportional hazards regression model. The primary effect measure was the resulting hazard ratio comparing dexamethasone vs. placebo with a corresponding two-sided 95% confidence interval. In the ‘Intention-to-treat population’, treatment was the only covariate. We additionally report the hazard ratio with the modified MRC grade included as stratum variable. The test for proportional hazards used the Kaplan-Meier as time transformation. In subgroup analyses, a separate Cox model was fitted for each value of the subgroup. The test for heterogeneity was based on the likelihood ratio test that includes subgroup as covariate and compares the models with subgroup as main effect only and with subgroup as treatment effect modifier, with TBM MRC severity grade at enrolment (I, II, or III) as covariates. ART=antiretroviral therapy. MRC=Medical Research Council. MDR=multi-drug resistant. TBM=tuberculous meningitis.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes occurred with similar frequency across both treatment arms in both the intention-to-treat and the per-protocol populations (Tables S7-8). Between the arms, there were similar frequencies of neurological disability (odds ratio, 1.31 95% CI 0.8-2.14) (Table S9), new neurological events or death (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67-1.08) and AIDS-defining events or death (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.68-1.12).

In ART-naïve participants, the median time to starting ART was 31 days (IQR 15-53) in 81 participants who received dexamethasone and 36 days (IQR 16-61) in 66 participants given placebo. Neurological IRIS events occurred during study drug administration in 8/20 (40.0%), and in 11/263 (4.2%) given dexamethasone and 9/257 (3.5%) given placebo (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.46-2.69). Open-label corticosteroids were prescribed to 70/263 (26.6%) and 68/257 (26.5%) in the dexamethasone and placebo arms respectively, with reasons, and time until use of open-label corticosteroids, provided in Table S10. Time to use of open-label corticosteroid for any reason was similar between study arms (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.69-1.35). No HIV-associated malignancies occurred by 12 months, and only one participant underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion.

No heterogeneity of effect was identified in the planned sub-group analysis of selected secondary outcomes (Tables S11-12, Figures S11-20), with the possible exception of a greater reduction of new neurological events and death associated with dexamethasone in the ‘possible’ tuberculous meningitis diagnosis sub-group of the intention-to-treat population (Table S11).

Serious adverse events

The numbers of participants with at least one serious adverse event were similar between dexamethasone (192/263 [73.0%]) and placebo (194/257 [75.5%]) study arms (P=0.52) (Table 3; Tables S13-14). Fewer participants experienced serious neurological adverse events (95/263 [36%] in the dexamethasone arm than in the placebo arm (115/257 [45%]). These serious neurological adverse events (275 events in 210 participants) were predominantly depressed consciousness (N=149) and new focal neurological signs (N=45). Gastrointestinal bleeding events, and other adverse events possibly, probably, or definitely related to corticosteroids, occurred with similar frequency between the study arms (Table S15). Likewise, the frequency of clinical grade 3&4 adverse events (Table S16), adverse events leading to interruptions in anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy or ART (Table S17), and grade 3&4 laboratory abnormalities were similar between study arms (Table S18), with the exception of episodes of high ALT that were more frequent in the dexamethasone (36/263 [13.7%]) than the placebo arm (20/257 [7.8%])).

Table 3. Serious adverse events.

| Characteristic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.pt | N.ae | N.pt | N.ae | |

| Any selected serious adverse event | 192/263 (73.0%) | 486 | 194/257 (75.5%) | 442 |

| Nervous system disorders | 95/263 (36.1%) | 128 | 115/257 (44.7%) | 147 |

| Infections and infestations | 60/263 (22.8%) | 79 | 50/257 (19.5%) | 63 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 51/263 (19.4%) | 66 | 59/257 (23.0%) | 68 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 39/263 (14.8%) | 40 | 37/257 (14.4%) | 39 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 38/263 (14.4%) | 44 | 29/257 (11.3%) | 29 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 32/263 (12.2%) | 33 | 21/257 (8.2%) | 25 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 20/263 (7.6%) | 23 | 17/257 (6.6%) | 17 |

| Investigations* | 14/263 (5.3%) | 14 | 9/257 (3.5%) | 9 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 14/263 (5.3%) | 15 | 7/257 (2.7%) | 7 |

| Vascular disorders | 10/263 (3.8%) | 10 | 11/257 (4.3%) | 11 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 12/263 (4.6%) | 13 | 5/257 (1.9%) | 6 |

| Cardiac disorders | 7/263 (2.7%) | 7 | 4/257 (1.6%) | 4 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 4/263 (1.5%) | 4 | 6/257 (2.3%) | 6 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 4/263 (1.5%) | 4 | 2/257 (0.8%) | 2 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 3/263 (1.1%) | 3 | 1/257 (0.4%) | 1 |

| Eye disorders | 0/263 (0.0%) | 0 | 3/257 (1.2%) | 3 |

| Endocrine disorders | 1/263 (0.4%) | 1 | 2/257 (0.8%) | 2 |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 1/263 (0.4%) | 1 | 1/257 (0.4%) | 1 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1/263 (0.4%) | 1 | 1/257 (0.4%) | 1 |

| Immune system disorders | 0/263 (0.0%) | 0 | 1/257 (0.4%) | 1 |

Events summarized according to the System Organ Class of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) hierarchy.

Denotes abnormal results of investigations. N.pt = the number of patients with at least one serious adverse event (% of all patients receiving the same intervention). N.ae = the total number of episodes of that particular serious adverse event. The number of patients with any adverse events and specific events, respectively, were summarized and compared between the two treatment arms based on chi-squared tests, or Fisher’s exact test if the expected number in one of the cells was smaller than one.

Discussion

We were unable to confirm a benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis on survival or any other pre-specified secondary endpoint. Planned subgroup analyses did not identify a sub-population that clearly benefited from dexamethasone. The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the arms.

In dexamethasone-treated HIV-negative adults with tuberculous meningitis, survival has been associated previously with elevated cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory cytokine concentrations,5 suggesting dexamethasone benefits patients with excessive intracerebral inflammation. Cerebrospinal inflammatory cytokine concentrations are higher in HIV-positive than HIV-negative individuals with tuberculous meningitis,21 yet our trial findings indicate little benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone on survival in this important population. These observations suggest intracerebral inflammation in HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis may be qualitatively different, or the mechanisms leading to death are different, compared to HIV-negative individuals.

Our study population was profoundly immunosuppressed, with 51.9% presenting with a CD4 count of ≤50 cells/mm3 and 49.0% ART-naïve. These individuals are at risk of developing other opportunistic infections, which might alter the impact of dexamethasone on outcome and increase the risk of adverse events. In addition, many participants were at risk of IRIS after starting ART, the neurological inflammatory complications of which can be fatal or disabling.22 Corticosteroids were previously shown to prevent IRIS in non-neurological tuberculosis,23 but we found dexamethasone did not reduce IRIS incidence or the timing or need for open-label corticosteroid treatment after randomization. However, dexamethasone doses were usually low by the time ART started (median 33 days after randomization), which may have reduced dexamethasone’s ability to prevent IRIS.

Our study has several limitations. First, we cannot exclude the possibility that a larger trial may have demonstrated a smaller mortality reduction than we hypothesized. The effect size observed (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.66-1.10) was less than anticipated (HR 0.69), although was similar to the HIV-positive population in our previous trial (relative risk 0.86, 95% CI 0.52-1.41). Second, 138 participants (26.5%) were given open-label corticosteroids at some time during treatment, and although the frequency and timing of their use was similar between arms and initial treatment allocations remained masked, the additional corticosteroids may have obscured outcome differences between arms. Third, the findings may not generalise to better resourced settings, with patients with less advanced HIV and wider access to ventriculoperitoneal shunting for hydrocephalus, a common life-threatening complication of tuberculous meningitis.24

A strength of our trial is that it studies adjunctive corticosteroids exclusively in HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis, increasing the available data from this important population by more than five times. The trial was pragmatic, enrolling all those with suspected tuberculous meningitis requiring anti-tuberculosis drugs and therefore generating findings of real-world relevance, where a high proportion of patients are treated for tuberculous meningitis without bacteriological confirmation. Lastly, the trial had high retention with only 5 participants lost to follow-up.

Given the high mortality of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis, and the frequency of inflammatory intracerebral complications, there is an ongoing need to explore alternative antiinflammatory strategies. These might include more targeted immunosuppression – against tumor necrosis factor α or interleukin-1, for example – which may be superior to corticosteroids for the prevention or treatment of inflammatory complications. Case reports and small case series have demonstrated a potential role for infliximab,25 thalidomide,26 and anakinra,27 in some tuberculous meningitis patients. Evaluation of these agents in clinical trials is required.

In summary, we did not establish a benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-positive adults with tuberculous meningitis on survival or any other secondary outcome over 12 months. The mortality associated with tuberculous meningitis in HIV-positive individuals remains unacceptably high, emphasising the global importance of enhanced detection and early treatment of HIV and tuberculosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all staff involved in caring for trial participants, laboratory and support staff at all trial sites, the patients who participated, and their relatives. The authors would also like to thank members of the Data Monitoring Committee and Trial Steering Committee (listed in Supplementary Text S7). Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge Laura Merson and Marcel Wolbers for their involvement in the initial design and set-up of the trial.

Funding

The trial was funded by Wellcome [110179/Z/15/Z]. The funder had no role in the design or conduct of this study.

References

- 1.Marais S, Pepper DJ, Schutz C, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G. Presentation and Outcome of Tuberculous Meningitis in a High HIV Prevalence Setting. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinnard C, King L, Munsiff S, et al. Long-term Mortality of Patients With Tuberculous Meningitis in New York City: A Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(4):401–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thwaites GE, Bang ND, Dung NH, et al. Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Tuberculous Meningitis in Adolescents and Adults. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1741–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruslami R, Ganiem AR, Dian S, et al. Intensified regimen containing rifampicin and moxifloxacin for tuberculous meningitis: an open-label, randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitworth LJ, Troll R, Pagán AJ, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels in tuberculous meningitis predict survival in response to dexamethasone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2024852118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024852118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shane SJ, Clowater RA, Riley C. Cortisone and Streptomycin in the Meningitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1952;67:13–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD002244. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002244.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahid P, Dorman SE, Alipanah N, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e147–195. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thwaites G, Fisher M, Hemingway C, et al. British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J Infect. 2009;59:167–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment - drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in Tuberculous Pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1121–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott AM, Luzze H, Quigley MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the use of prednisolone as an adjunct to treatment in HIV-1-associated pleural tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:869–78. doi: 10.1086/422257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beardsley J, Wolbers M, Kibengo FM, et al. Adjunctive Dexamethasone in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:542–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan J, Phu NH, Mai NTH, et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone for the treatment of HIV-infected adults with tuberculous meningitis (ACT HIV): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:31. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14006.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan J, Khanh TDH, Thwaites GE, Geskus RB. A statistical analysis plan for the Adjunctive Corticosteroids for Tuberculous meningitis in HIV-positive adults (ACT HIV) clinical trial. Wellcome Open Res. 2022;6:280. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17154.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:803–12. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medical Research Council. Streptomycin treatment of tuberculous meningitis. Lancet. 1948;1:582–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nhu NTQ, Heemskerk D, Thu DDA, et al. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for Diagnosis of Tuberculous Meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:226–33. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01834-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heemskerk AD, Bang ND, Mai NTH, et al. Intensified Antituberculosis Therapy in Adults with Tuberculous Meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2021. https://www.r-project.org/

- 21.Thuong NTT, Heemskerk D, Tram TTB, et al. Leukotriene A4 Hydrolase Genotype and HIV Infection Influence Intracerebral Inflammation and Survival From Tuberculous Meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1020–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marais S, Meintjes G, Pepper DJ, et al. Frequency, Severity, and Prediction of Tuberculous Meningitis Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:450–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meintjes G, Stek C, Blumenthal L, et al. Prednisone for the Prevention of Paradoxical Tuberculosis-Associated IRIS. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1915–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donovan J, Figaji A, Imran D, Phu NH, Rohlwink U, Thwaites GE. The neurocritical care of tuberculous meningitis. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:771–83. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marais BJ, Cheong E, Fernando S, et al. Use of Infliximab to Treat Paradoxical Tuberculous Meningitis Reactions. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofaa604. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Toorn R, Solomons RS, Seddon JA, Schoeman JF. Thalidomide Use for Complicated Central Nervous System Tuberculosis in Children: Insights From an Observational Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e136–145. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keeley AJ, Parkash V, Tunbridge A, et al. Anakinra in the treatment of protracted paradoxical inflammatory reactions in HIV-associated tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: a report of two cases. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31:808–12. doi: 10.1177/0956462420915394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.