Abstract

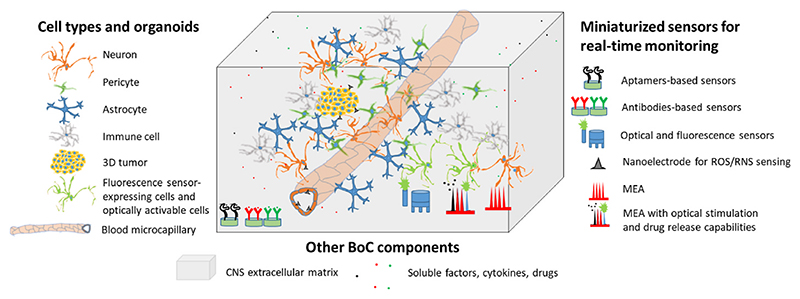

Brain-on-a-chip (BoC) devices show typical characteristics of brain complexity, including the presence of different cell types, separation in different compartments, tissue-like three-dimensionality, and inclusion of the extracellular matrix components. Moreover, the incorporation of a vascular system mimicking the blood-brain barrier (BBB) makes BoC particularly attractive, since they can be exploited to test the brain delivery of different drugs and nanoformulations. In this review, we introduce the main innovations in BoC and BBB-on-a-chip models, especially focusing sensorization: electrical, electrochemical, and optical biosensors permit the real-time monitoring of different biological phenomena and markers, such as the release of growth factors, the expression of specific receptors/biomarkers, the activation of immune cells, cell viability, cell-cell interactions, and BBB crossing of drugs and nanoparticles. The recent improvements in signal amplification, miniaturization, and multiplication of the sensors are discussed in an effort to highlight their benefits versus limitations and delineate future challenges in this field.

Keywords: Brain organoids, Brain-on-a-chip, Blood-brain barrier, Vascularized brain models, Optical sensors, Electrical sensors, Electrochemical sensors, Genetically-encoded sensors, Digital immunosensors

1. Introduction

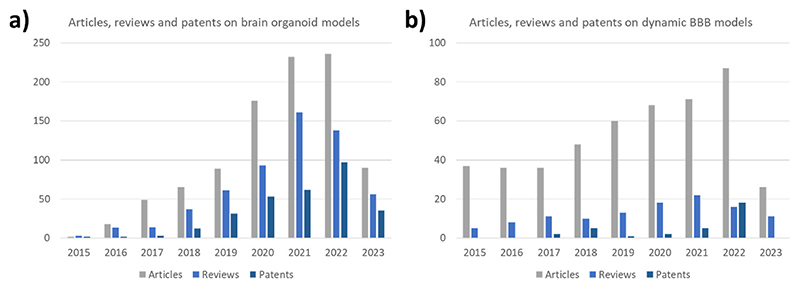

Biomimetic brain-on-a-chip (BoC) devices are brain-mimicking platforms exploited by public research centers, contract research organizations, and pharmaceutical companies to model specific physio/pathologic conditions and to perform in vitro pre-clinical drug screening. BoC systems have been used to study and perform drug testing on pathologic models including neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s diseases), ischemia, and neuroinflammation [1]. Moreover, they have been exploited to model and investigate physiologic phenomena of the central nervous system (CNS), such as neural network development (e.g., vascularization, neurite outgrowth, and synaptogenesis), cell-cell communication, and immune function [1]. The interest in such brain-mimicking models has remarkably grown in recent years (Fig. 1a shows the growing number of articles, reviews, and patents on brain organoid models from 2015). Considering that FDA no longer has to require to carry out animal tests before clinical trials [2], the use of advanced in vitro models is expected to further grow in the next years.

Fig. 1.

The growing number of research articles, reviews, and patents on a) brain organoid and b) microfluidic dynamic BBB models from 2015 to 2023 (data up to May 31st, 2023).

Brain-mimicking in vitro models differentiate from standard in vitro culture systems since they show typical features of tissue complexity, such as multicellularity, three-dimensionality, vascularization, and the presence of extracellular matrix surrounding cells. Such 3D brain-mimicking models demonstrate superior prediction capabilities compared to simple 2D monolayer cultures [3–6]. Furthermore, their complexity level permits the evaluation of multiple correlated phenomena in a single study, such as drug delivery from the vasculature, drug targeting, drug efficacy in targeted cells, and side effects on healthy cells [7]. Nevertheless, they show remarkably higher accessibility compared to the animal brain, therefore facilitating the control of the experimental conditions as well as the monitoring of the treatment effects. However, the use of BoC devices for carrying out high-throughput investigations and real-time monitoring of experimental results is still challenging. To these aims, the emerging trends involve the incorporation of sensors [8] and the miniaturization of the models [9]. The exploitation of scalable microfabrication technologies is instead required for industrialization.

A fundamental feature of the BoC model is the prediction capability, that is the ability of the system to predict specific phenomena as well as the outcomes of a treatment. Highly predictive BoC are extremely valuable in the selection of the most promising CNS drug candidates, limiting ethical concerns on animal studies and with a remarkable socio-economic impact. As introduced above, the prediction capability is strictly connected to the model biomimicry. In this regard, the incorporation of patient-derived human cells (such as primary cells and induced pluripotent stem cells - iPSCs -) is a recent trend that allows not only to improve the model accuracy, yet also to test patient-tailored target therapies and other personalized treatments [10,11]. As another example, the use of tissue-specific and disease-associated extracellular matrix components to develop brain-mimicking models is gaining interest in the scientific community [12]. This approach particularly suits brain cancer investigations, to examine the mechanisms of cancer cell migration/invasion as well as to test drugs acting on those biological pathways [13].

A particularly important characteristic to replicate into BoC devices is the brain microvasculature, especially for drug delivery applications. The brain is a highly vascularized organ and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) protects it from harmful compounds, viruses, bacteria, and particles. The BBB strongly limits the crossing of pharmaceutical drugs for CNS treatment. Not adequate BBB crossing ability represents a basic criterion for the selection of promising drug candidates, the failure of which results in the termination of drug testing [14]. For this reason, BoC models incorporating a vascularization system are particularly attractive for drug screening purposes (Fig. 1b shows the growing number of articles, reviews, and patents on microfluidic dynamic BBB models from 2015). Such BBB-on-a-chip models can be used to analyze the dynamics of drug/nanomedicine crossing, to support the drug development phases (e.g., in the selection of the drug analogs most efficient in BBB crossing), and to monitor the efficacy and safety of BBB-opening technologies (e.g., microbubbles) [15].

In this review, we discuss recent trends in BoC devices and their implementation with innovative electric, electrochemical, and optical sensors for real-time monitoring and high-throughput testing, highlighting microfluidic platforms for BBB testing capabilities.

2. Brain delivery investigations: from static to microfluidic BBB systems

BBB is a continuous structure enveloping brain blood vessels and separating the bloodstream from the brain environment. The main function of the BBB is to regulate the passage of ions, molecules, and cells from the bloodstream to the CNS and block the passage of potentially harmful substances [16]. The BBB is a part of the so-called neurovascular unit (NVU) which is composed of various cellular components such as brain endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, neurons, microglia, and extracellular components like basement membrane or extracellular matrix [17]. Despite its physiological functions, the BBB represents one of the main obstacles in the treatment of CNS disorders being able to block the passage of most commonly used drugs and therapeutical molecules [18]. Moreover, BBB dysfunctions have been identified and connected to most CNS disorders, including brain cancers and neurodegenerative diseases [19]. The study of BBB functions both in healthy and pathological conditions and the assessment of BBB crossing abilities of candidate drugs thus represent a pivotal topic for the development of treatments for CNS disorders [20]. Currently, in vivo testing represents the most widely used approach to model BBB and assess the ability of candidate drugs to reach the CNS. However, the use of animals for in vivo testing is time-consuming and expensive, presents a relatively low reproducibility and low translatability of the obtained results in humans, and is affected by the ethical concerns connected to the use of living animals [20]. Therefore, there is a strong need for in vitro models able to replicate the in vivo conditions of the NVU.

The most common in vitro models of the BBB are the Transwell inserts, which are 2D porous membranes of various sizes and materials [21,22]. These inserts are usually seeded with brain endothelial cells on top of the porous membrane and then placed in a multi-well cell culture plate. The obtained in vitro BBB model is therefore composed of an apical (luminal) and a basolateral (abluminal) compartment separated by a layer of brain endothelial cells (other components of the NVU such as astrocytes of pericytes can also be introduced) [21,22]. To assess the integrity of the obtained BBB in vitro models, various tests can be carried out: the commonly used tests are transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements [23], permeability tests involving the use of fluorescent tracers [24], and protein expression analysis [25]. TEER analysis refers to the measurement of the electrical resistance posed by a brain endothelial cell layer, and is a quantitative measurement of the barrier coverage and tight junctions’ integrity. TEER measurement is commonly carried out by positioning two electrodes, one in the luminal and one in the abluminal side of the model, and by applying alternating current [23,26]. The TEER is then calculated by applying Ohm’s law as a function of the voltage and current applied [23,26]. Permeability tests are commonly carried out by administrating a fluorescent tracer (e.g., fluorescent dextrans of various molecular weights) to the luminal side of the model, and by monitoring its passage across the BBB cell layer over time [24,26]. Lastly, the analysis of protein expression on BBB in vitro models is usually carried out by immunostaining to assess the presence of cellular localization of specific markers of tight junctions like claudins (CLDN), zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), and occludin [OCLN) [25,26].

Currently, the most used in vitro BBB systems rely on commercial Transwell inserts, that consist of simple permeable supports placed in multi-well cell culture plates. Inserts are available in different materials, sizes, and pore diameters, thus representing very versatile and cheap platforms for in vitro BBB crossing assays. Nevertheless, these models present several limitations: first, they only allow 2D cell cultures, failing at recapitulating perivascular 3D cell arrangement. Second, they underestimate the importance of physiological shear stress on endothelial cells, needed for the achievement of stringent barriers (by the development of tight junctions). These drawbacks result in models that poorly mimic in vivo barriers, with consequent unreliable outcomes [26]. This all considered, the interest in the production of new microfluidic 3D BBB in vitro models, with a higher degree of biomimicry, literally exploded in the latest years. Recent literature identifies two main BBB model classes: “microfluidic 3D vasculogenesis models” and “microfluidic 3D perivascular devices” [27]. The former exploits the spontaneous tubulogenic properties of endothelial cells into hydrogels to form capillary networks; despite the high biomimetic complexity of micro-vessel networks that can be attained, this model is still far from actual applications in high-throughput screenings, due to difficult shear stress control and sampling in each vessel. The latter presents a design defined by the operator to reproduce the in vivo BBB complex architecture and function [28]. The main research effort in the modeling of BBB in vitro is placed on the improvement of the biomimetic properties of microfluidic devices, and in the next section, we will analyze the most recent development in this direction.

3. Innovative microfluidic brain-on-a-chip models

BoC models combine cell culture, microfabrication, and microfluidics technology to mimic structures and functions of the brain, and to study the complex interactions between the brain environment and the NVU. One of the main research trends related to in vitro BoC models concerns the geometry of these devices and the spatial organization of the cellular components used to replicate the NVU and other biological structures.

These microfluidic devices can be designed by using different strategies based on the spatial arrangement of the “blood” and “brain” compartments. The double-layer configuration is an improved version of the Transwell model which includes an upper and a lower chamber separated by a porous membrane. While most models using this configuration are seeded with cells forming 2D layers, recently there has been a shift towards platforms exploiting 3D matrixes to mimic the in vivo physiological distribution of the NVU cells. In this regard, Ahn et al. fabricated a microfluidic device in PDMS consisting of two chambers separated by a porous membrane with 8 μm-diameter pores where the physiology of the BBB is mimicked through a 2D endothelial monolayer in the upper compartment, pericytes accommodation underneath the membrane, and astrocytes in 3D Matrigel located in the lower layer [29]. This model was used to assess the passage of HDL-mimetic nanoparticles engineered with apolipoprotein A1 (eHNP-A1), demonstrating the potential of this nanoplatform in crossing the BBB through a transcytosis-mediated mechanism [29].

Despite this vertical spatial arrangement of the microfluidic chip appears to mimic the main characteristics of the BBB, it poses a limitation on simultaneous visualization of all the involved cell types, thereby hindering microscopic analysis. To overcome these limitations, the adoption of a planar side-by-side configuration may be considered. This configuration is composed of two or more parallel horizontal microfluidic channels separated by an array of micropillars. The BBB-on chip proposed by Lee et al. is a PDMS microfluidic system composed of four channels compartmentalized by arrays of micro-pillars having a triculture system with functional barrier properties. They observed how human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) and human brain vascular pericytes (HBVPs) sprout and protrude to the opposite side of the channel containing human astrocytes (HAs) in fibrin hydrogel, thus developing a 3D blood vessel network [30].

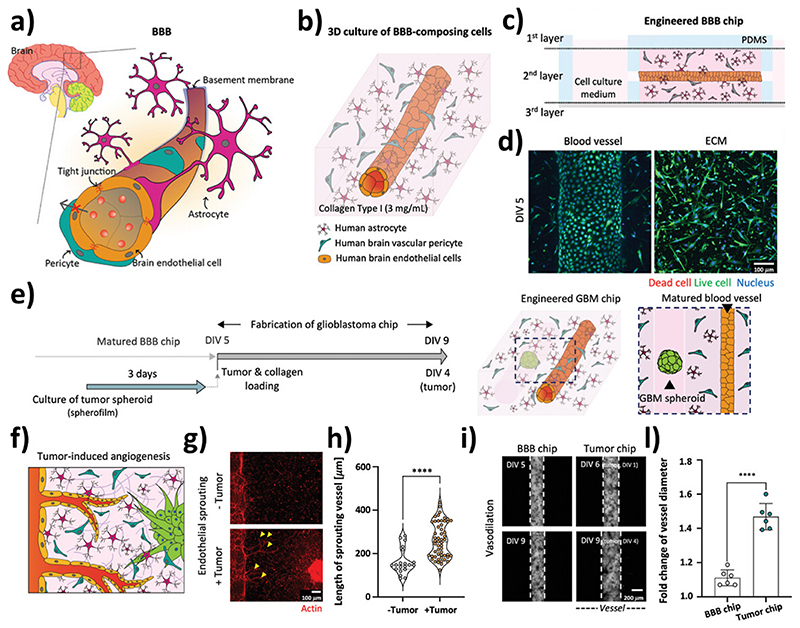

The above-mentioned configurations are suitable for verifying the maturity and the integrity of the BBB through permeability assays, expression of tight junction proteins, and TEER measurement. However, they have limitations related to modeling shear stress on the endothelial component of the barrier. Due to the fabrication process, the double-layer and side-by-side configurations have a prismatic geometry that makes it challenging to attain uniform shear stress in the models: upgraded 3D configurations with a tubular design featuring cylindrical channels have been developed to address this issue, such as the triculture tubular BBB model proposed by Seo et al. In their work, Seo and colleagues realized a co-culture with perivascular cells in a 3D hydrogel matrix in a PDMS device using micro-needles. After gelation, the micro-needles are extracted and the endothelial cells are seeded into the hollow collagen cylinder, resulting in the formation of a cylindrical brain endothelium surrounded by pericytes and astrocytes [31] (Fig. 2). This model not only is a valuable representation of the physiological BBB, yet it has also been utilized for investigating the effect of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) on the NVU. The interaction between GBM spheroids and the matured BBB induced an increase in length and number of new vessels, and a dilatation of the blood vessels resulting in increased permeability, thus providing a platform for drug screening in pathological conditions. In 2019, our group proposed a BoC microfluidic platform to assess both the BBB crossing efficiency and the anticancer properties of nultin-3a and superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (Nut-Mag-SLNs). In particular, we developed a bicompartmental microfluidic device mimicking both the blood vessels and the glioblastoma environment on a single platform. Owning to this device, we were able to assess the ability of the developed Nut-Mag-SLNs to be guided with an external static magnetic field, cross the BBB, reach the glioblastoma compartment, and act as an anticancer agent by reducing cancer cells proliferation while at the same time inducing apoptosis [32].

Fig. 2.

Biomimetic microfluidic BoC mimicking the NVU-tumor interactions in a collagen-based extracellular matrix. Schematic representations of a) the in vivo NVU, b) the in vitro fluidic NVU model with human brain endothelial cells, human brain pericytes, and human astrocytes (BBB chip), and c) the cross-section of the microfluidic system. d) Imaging of the cells developing the blood vessel (left) and of the cells in the extracellular matrix (ECM). e) BBB chip incorporating a 3D GBM (tumor chip): f) schematic representation, g) imaging, and h) analysis of the tumor-induced angiogenesis. i) Imaging and l) analysis of the NVU dilation induced by the presence of the tumor. Adapted with permission from Ref. [31].

BoC model can be used to model also non-cancer-related pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease [33], Parkinson’s disease [10], and brain ischemia [34]. For example, several key hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease such as the gradual accumulation of amyloid beta protein have been recapitulated in a BoC model based on a side-by-side multichamber microfluidic device [33]. The proposed system was composed of a fluidic chamber seeded with immortalized human brain endothelial cells, two microchannels filled with collagen, and a “brain” compartment with a 3D culture of ReNcell® neuronal progenitor cells expressing Alzheimer’s disease-specific proteins [33]. Similarly, Pediaditakis et al. developed a BoC model to investigate Parkinson’s disease-related alpha-synuclein pathology [10]. The device included a vascular channel seeded with iPSC-derived brain endothelial cells and a brain compartment mimicking the substantia nigra seeded with iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons, primary human brain astrocytes, microglia, and pericytes. Moreover, the authors were able to reproduce some of the key aspects of synucleinopathies by administrating alpha-synuclein [10]. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, BoC models can also be used to assess the delivery of candidate compounds and nanoparticles. In one such example, Palma-Florez et al. developed an organ-on-a-chip model for the screening of nanocarriers as theranostic agents against Alzheimer’s disease [35]; the authors developed gold nanorods (GNR) functionalized with polyethylene glycol (PEG), D1 peptide able to inhibit beta-amyloid accumulation, and the BBB targeting angiopep-2 peptide (Ang 2). The BBB crossing ability of the developed nanostructures was assessed on the previously mentioned microfluidic organ-on-chip model composed of brain endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes, and an integrated system for TEER monitoring [35]. In another example, Lenoir et al. developed a Huntington disease (HD) BoC model based on the culture of primary neurons derived from a HD mouse model, and able to replicate the environment of corticostriatal networks [36]. This platform was used to test the efficiency of the drug pridopidine against the synaptic impairments typical of HD. In particular, the authors demonstrated that the administration of pridopidine in their BoC model was able to rescue neurotransmitters trafficking and homeostasis at synaptic level of HD-derived primary neurons [36].

Lyu et al. proposed a BoC model to study stem cell-based regenerative therapies against ischemic stroke. This device was composed of a vascular chamber seeded with immortalized brain endothelial cells, a brain compartment seeded with stem cells-derived neurons, and a third innovative channel mimicking the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) environment [34]. By exposing the device to low oxygen values and nutrient depletion, the authors were able to simulate some of the hallmarks of ischemic stroke in terms of apoptosis induction gene expression [34].

By using BoC models, the study of more complex cellular behaviors, such as the immune response, is also possible. For example, Lauranzano et al. proposed an NVU model based on a microfluidic bi-compartmental device with a porous filter to study the transmigration of human T lymphocytes across the BBB. The platform is suitable for the evaluation of immune cell trafficking, allowing to test in a brain tumor context whether contact between astrocytes and isogenic T cells during transmigration modulates the molecular and functional phenotype of lymphocytes [37].

Another recent trend in the development of biomimetic in vitro microfluidic brain-on-a-chip models is connected to the shift from immortalized cell lines to other cellular sources able to better replicate the physiological characteristics of the human NVU and of the overall CNS. One of the limitations connected with the use of immortalized cell lines is in fact that they are unable to replicate with high fidelity the characteristics of the in vivo BBB in terms of permeability and protein expression. Moreover, there have been great efforts from the research community towards the development of personalized in vitro BoC models, able to replicate the properties of the NVU and of the surrounding brain parenchyma specific to each patient. Both these points can be addressed by using patient-derived primary cells, like in the case of the aforementioned work by Lauranzano et al., where astrocytes directly isolated from patient brain tissue were co-cultured in a microfluidic model to assess T cell transmigration [37].

Despite their potential, the use of human primary cells is time-consuming due to the complicated and invasive procedure necessary to obtain patient biopsies and the limited proliferative capabilities of primary cells. The advantage of stem cells over primary cells is mainly due to their high proliferative abilities and their capabilities to differentiate into various cell types. For example, iPSCs have been proposed as an alternative to primary cells to set up in vitro BBB models. The principle behind the use of iPSCs is to obtain differentiated somatic cells from adults (e.g., dermal fibroblast biopsy) to be de-differentiated in iPSCs. iPSCs can then be differentiated again into the various components of the NVU or of the CNS. For example, it has been shown that is possible to reproduce the BBB complex functions using patient-derived iPSCs differentiated into endothelial cells and pericytes, providing a promising platform for studying brain diseases that could potentially be employed to develop personalized therapies [10,11].

Stem cells can be used also to develop self-assembled 3D cultures/co-cultures able to replicate the structure of the brain and NVU. Brain-mimicking models consist of 3D multi-cellular structures obtained from the differentiation of stem cells in NVU components. In particular, two types of human pluripotent stem cells are commonly used to construct organoid-based BBB models: human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or human iPSCs (hiPSCs), which are then differentiated into the various components of the NVU or in other cellular components of the CNS, such as specific subsets of neurons. The most recent trends involve the vascularization of the models to better replicate the functional NVU in vitro. The main strategies involve the use of growth factors to induce vessel-like structures [38]; alternatively, more recently it has been demonstrated that vascularization can be induced by co-culturing fragments of vascularized organoids with no-vascularized organoids [39]. Being easy to set up and relatively economical, 3D brain-mimicking models can also be used in high-throughput screening approaches where a vast array of candidate drugs and substances can be simultaneously assessed [40]. For example, in 2018 Bergmann et al. described a protocol to produce BBB organoids to test the brain permeability of candidate compounds [41]. The protocol described in this work was based on the co-culture of brain endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes under low-adhesion conditions. The obtained organoids were able to express key molecular factors involved in the transport mechanisms across the BBB, and could be used for the high-throughput screening of drug permeability through fluorescence-based techniques or mass spectrometry imaging [41].

Although the discussed models have provided valuable insights, a major limitation is their large size compared to brain capillaries. To overcome this issue different strategies to obtain BoC models with sizes comparable to those of brain capillaries have been proposed. For example, self-assembled capillaries have been developed by Campisi et al. [42]. These capillaries are composed of a monolayer of hiPSC-derived ECs, co-cultured with brain PCs and ACs embedded in a 3D fibrin hydrogel. The resulting BBB model exhibits a selective microvasculature able to be perfused with permeability levels lower than conventional in vitro models, and comparable to in vivo measurements. Furthermore, the 3D microfluidic system has been exploited to measure the passage of differently-sized nanoparticles across the BBB [43].

Lastly, our group successfully demonstrated the potential of high-resolution 3D printing technologies in creating biomimetic fluidic brain microcapillaries [44]. We exploited two-photon lithography to fabricate structures at the submicron scale, and developed the first 1:1 scale biomimetic BBB. The proposed microfluidic device is composed of multiple parallel porous microcapillaries, where HBMECs were seeded on the inner surface. Recently, the BBB model has been further enhanced by incorporating 3D magnetic scaffolds to enable tumor cell culture and to mimic the interaction between BBB and glioblastoma [45]. The developed BoC model was used to test the permeability and therapeutical efficiency of anticancer drugs against GBM.

Details of the discussed microfluidic platforms, such as the type of cells used, the parameters analyzed to evaluate barrier integrity, and applications are listed in Table 1. The main future perspective in the development of BBB biomimetic in vitro models is represented by the combination of the approaches described in this section. In particular, the future ideal in vitro BBB model should include several parallel BBB platforms for high-throughput screening, where each platform should be composed of biomimetic, tridimensional, and multicellular models in 1:1 scale with brain capillaries.

Table 1. Summary of the main characteristics of the microfluidic brain-on-a-chip models.

| Ref | Trend | Aim | Configuration of the BBB | Fabrication/set-up procedure | 3D ECM material | Cellular NVU components | Other cell types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells | Establishment of an NVU in vitro model and test of nanoparticle passage | Double-layer | Photolithography/soft-lithography (PDMS) | Matrigel | Immortalized: HBMECs Primary: HBVPs, HAs | N/A |

| [30] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells | Set-up of an in vitro BBB model able to mimic CNS angiogenesis | Side-by-side | Photolithography/soft-lithography (PDMS) | Fibrin hydrogel | Primary: HBMECs, HUVECs, human pericytes, HAs | 3D fibroblast spheroids as a source of angiogenic factors |

| [31] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment mimicking GBM | Study of the interactions between GBM and NVU, and study of drug permeability | Tubular | Photolithography/soft-lithography (PDMS) | Collagen type I | Primary: HBVPs, HAs, HBMECs | Spheroids of T98G and U87MG cells |

| [32] | 3D microfluidic device incorporating a brain compartment mimicking GBM | Drug delivery tests involving lipid nanostructures for the treatment of glioblastoma | Double-layer | Laser cut and assembly of a multichamber device based on a porous insert | N/A | Immortalized: bEnd.3 mouse brain endothelial cells | U87MG cells |

| [33] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment mimicking AD | Set-up of an in vitro model of AD | Side-by-side | Photolithography/ soft-lithography (PDMS) | Collagen type I | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 | ReNcell® human neural progenitor cell line either wild-type or AD-related mutations |

| [10] | Microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment mimicking AD, use of stem cells | Set-up of an in vitro model of PD | Double-layer | Fabricated by Emulate, Inc. (PDMS) | N/A | hiPSC-derived HBMECs Primary: HAs, HBVPs, human microglia | iPSCs-derived dopaminergic neurons |

| [34] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment, use of stem cells | Establishment of an ischemia model and testing of a stem cell-based regenerative therapy | Side-by-side | Stereolithography 3D printing (PDMS) | Hydrogel | Primary: BMECs, Has, human brain vascular pericytes | HMC3, stem cells-derived neurons |

| [35] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells | Development of a microfluidic NVU model for testing drug delivery platforms | Side-by-side | Photolithography/soft lithography (PDMS) | Hydrogel | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 Primary: human hippocampal astrocytes, human brain-vascular pericytes | N/A |

| [36] | 3D microfluidic device with human cells | Development of a HD BoC model for drug delivery tests | Side-by-side | Photolithography/soft lithography (PDMS) | N/A | N/A | cortical and striatal neurons |

| [37] | 3D Microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of immune cells | NVU with patient- derived astrocytes obtained from tumor resection margin. Model used to test T lymphocyte migration | Device-based on porous membrane insert exposed to flow conditions | Assembly of a multichamber device based on a porous insert | Geltrex | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 Primary: HAs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) |

| [11] | Microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment | Establishment of a personalized BoC model as a potential platform for disease modeling and drug screening | Double-layer | Fabricated by Emulate, Inc. (PDMS) | N/A | hiPSC-derived HBMECs Primary: HAs, human pericytes | iPSC-derived neural cells |

| [38] | 3D vascularized organoids based on human cells, use of stem cells | Set-up of vascularized human cortical organoids | Organoids based on hESCs | Engineered hESCs | N/A | hESCs-derived ECs | hESCs differentiated into cells expressing markers typical of cells of the brain environment like cortical neurons, interneurons, astrocytes, radial glial cells, glial progenitor cells, and neuronal progenitor cells |

| [39] | 3D vascularized organoids based on human cells, use of stem cells | Analysis of the interaction between BVOs and cortical organoids | Organoids based on hiPSCs | Differentiation of hiPSCs | Matrigel | hiPSCs-derived blood vessel organoids (BVOs) | hiPSCs-derived cortical organoids |

| [40] | 3D organoids, use of human cells | Set-up of BBB organoids for drug screening | Organoids based on differentiated cells | Assembly of the cellular components of the NVU into organoids | Hydrogel | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 Primary: human pericytes,HAs | N/A |

| [41] | 3D organoids, use of primary human cells | Set-up of BBB organoids for drug screening | Organoids based on the selfassembly properties of NVU components | Self-assembly of the cellular components of the NVU into organoids | 3D structures based on the self-assembly properties of NVU cells | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 Human brain vascular pericytes (HBVPs), Primary human astrocytes | N/A |

| [43] | 1:1 scale, 3D microfluidic device with human cells, use of stem cells. | Set-up of an NVU microfluidic model for testing the passage of nanostructures | Side-by-side | Photolithography/ soft-lithography (PDMS) | Fibrin hydrogel | hiPSC-HBMECs Primary: HAs, human pericytes | N/A |

| [45] | 1:1 scale, 3D microfluidic device with human cells, incorporation of a brain compartment | Set-up of a brain-on-a- chip model in 1:1 scale with brain capillaries for drug-screening | Tubular | Two-photon lithography (SU-8 photoresist) | N/A | Immortalized: hCMEC/D3 Primary: HAs | U87MG glioblastoma cells |

4. Integration of sensors in BoC models

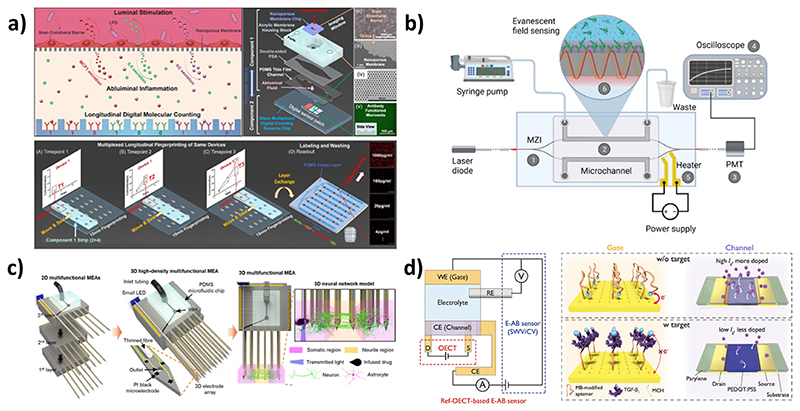

Recent advances in sensors have been of great interest in the study of disease progression in response to drug treatments. Their integration into microfluidic BoC models enables real-time monitoring of tissues (Fig. 3), while previous approaches were mainly limited to end-point tests, reducing the gap between in vitro and in vivo models. Sensors aim to be highly sensitive, accurate, stable over time, and minimally invasive. They are classified into three categories depending on their detection method: electrical, electrochemical, or optical [46].

Fig. 3. Representative sensors designed for integration into BoC models.

a) Schematic of digital immunosensors integrated into BBB-on-a-chip model for the sequential detection of cytokines. Reprinted with permission from. Ref. [69]. b) Schematic representation of an integrated optical Mach-Zender interferometer for the detection of target spike protein S1 subunit crossing the BBB after coronavirus infection. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [70]. c) Schematic illustration of 3D high-density microelectrode array integrated into a 3D neural network in vitro model. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [71]. d) Schematic of the sensing mechanisms of the ref-OECT-based E-AB sensor for the detection of TGF-B1. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [52].

Electrical sensors have been extensively used in BoC models due to their simple integration into microfluidic models. Microelectrode arrays (MEA) are particularly well adapted to measure the electrophysiological activity of neurons, but can also provide information on BBB integrity [8,46]. Recent studies showed the potential of such models in the scope of brain diseases. Liu et al. recently combined indium-tin-oxide microelectrodes with neural stem cells spheroid-based BoC models to study AD. Real-time impedance measurements were correlated with the formation and degeneration of neuronal networks after the addition of amyloid beta, one of the major pathological hallmarks of AD known to be toxic for neurons and to induce degeneration of synapses [47]. Still regarding AD treatment, Palma-Florez et al. integrated microelectrodes into their BBB-on-a-chip to evaluate the permeability performance of gold nanorods developed to overcome the BBB and to disassemble amyloid aggregates. The measure of TEER with electrodes placed at a micrometric distance of the BBB allowed them to prove the successful formation of a cell barrier and to evaluate the effect of nanomaterials on the tight junctions’ integrity [48].

Electrochemical biosensors are a sub-class of electrical sensors where the working electrode is modified with a biological recognition element [49]. A recent trend is represented by the implementation of miniaturized aptamer-beacon-based (E-AB) sensors for high-sensitive screening purposes. These rely on modified electrodes functionalized with aptamers, which are synthetic DNA or RNA strains able to bind target molecules with high affinity and selectivity. The binding of specific target molecules with redox-labeled aptamers induces a change in the 3D conformation, modifying the distance between the redox tag and the electrodes and thus the measured signal. These types of sensors have been widely used, as they offer real-time sensing of a broad range of targets. However, their sensitivity is highly dependent on the number of aptamers and therefore on the surface area, limiting the possibility of miniaturization for the integration into BoC devices. To overcome this limitation, Guo et al. developed a 2D CuNi metal-organic framework exhibiting a graphene-like structure, able to anchor a much larger amount of aptamers compared to standard electrodes of similar size. With this bifunctional sensor, they selectively detected living C6 glioma cells (from 50 to 1.105 cells/mL) and their endothelial growth factor (EGFR) biomarker (limit of detection of 0.72 fg/mL), exhibiting great potential for cancer diagnosis [50]. In 2022, Shaver et al. optimized an aptamer-based sensor to reach a better detection of vancomycin, an antibiotic that can be used for the treatment of bacterial meningitis. By using a one-base-pair-longer aptamer, they were able to resolve vancomycin concentration from baseline noise in the brain cortex of living mice, which was not possible in previously developed vancomycin-E-ABs [51]. Finally, most recently, Ji et al. used organic electrochemical transistors as on-site amplifiers for the detection of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1). Their device consists of an aptamer-modified Au working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) counter-electrode, achieving direct amplification of the current in the working electrode [52]. They could reach 3-4 orders of magnitude enhancement in sensitivity compared to the bare E-AB sensor. These different approaches pave the way for future integration of E-AB into BoC, and can also be applied to other types of electrochemical sensors to improve electrode interface and implement in situ amplification of measured signals.

Electrochemical sensors can be also designed to detect small metabolic products, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which regulate a plethora of biological phenomena at physiologic concentrations (e.g., H2O2 intracellular concentration in the 1–100 nM range), yet contribute to the pathogenesis of different neurodegenerative diseases at elevated concentrations [53,54]. The overproduction of these reactive molecules triggers oxidative damage to different cell components, such as DNA bases, amino acids, and phospholipids of the membranes, with activation of senescence and apoptotic pathways. Due to the high reactivity of these molecules, their half-life in the cell medium is very short: therefore, sensors require elevated sensitivity [55]. In this regard, electrochemical sensors allow the local detection of ROS/NOS in real-time with high selectivity, elevated sensitivity, and miniaturization potential [56]. The development of these sensors recently reached the single-cell detection scale thanks to the use of nanoelectrodes [57]. The most investigated ROS/NOS with this technology is H2O2, which is also the most common and stable ROS. Two types of H2O2 electrochemical sensors have been developed: the enzymatic biosensors, such as those based on the horseradish peroxidase, show good sensitivity but limited stability and potential inhibition of the enzymatic activity by contaminants [55]; the non-enzymatic sensors, instead, show long-term stability. Furthermore, different materials/nanomaterials-composites have been recently exploited in non-enzymatic H2O2 sensors to reach excellent sensitivity properties [58–65]. Concerning CNS application, despite different H2O2 sensors have been exploited to monitor the ROS levels in brain cancer cells (such as U87 glioblastoma cells), the incorporation of these sensors in proper 3D brain tumor-a-chip (BToC) or BoC models has not been described yet. However, since the ROS are known to play a fundamental role in the regulation of neuronal development and function (i.e., cell polarity, axonal outgrowth, synapsis formation, and network tuning), the approach of monitoring their concentration in real-time by electrochemical sensors is expected to be increasingly used due to their improved performances; also the rapid commercialization and standardization of such systems for high-throughput tests is envisaged.

Optical sensors are easily integrable into BoC models as they do not require direct physical or electrical contact between the transducer and the detector [8,66]. The optical signal is generated directly by the interaction of the analyte with the transducer or through a labeling agent. Recent progress in gene engineering led to the development of genetically encoded fluorescent indicators with a high spatiotemporal resolution, providing access to a broad range of biological events. Such indicators have been recently used for calcium imaging, detection of neural activation (voltage-sensitive indicators), and as sensors for neurotransmitters and neuromodulators with a high signal-to-noise ratio on in vitro and in vivo brain models [67]. Most recent trends concern the expansion of the spectral diversity, through the development of a genetically-encoded far-red fluorescent indicator for the imaging of synaptic Zn2+, a key neuromodulator in the brain [51], or a near-infrared genetically-encoded indicator for calcium imaging [68]. An innovative optical biosensor was recently presented by Su et al. in 2023. They developed a BBB-on-a-chip platform integrating digital immunosensors for the sequential detection of three cytokines species relevant to neuroinflammation, with a limit of detection of 100-500 fg/mL. These immunosensors have a short detection time and use a very limited amount of bulk solution to generate digital sensor signals [69].

Mach-Zehnder interferometer is also of great interest regarding its high sensitivity and portability, facilitating its integration into BoC models. This interferometric construction is based on waveguide structures functionalized by recognition elements. The binding of analytes induces a change of the refractive index in the measuring arm, resulting in a phase shift in the propagation wave compared to the referring arms. This type of device was recently integrated into a BBB-on-a-chip model to demonstrate the barrier penetration capability of the surface spike protein subunit 1 of SARS-CoV-2 into the brain, emphasizing the neuroinvasive potential of this virus [70].

5. Discussion

Biomimetic BoC and BBB-on-a-chip are platforms allowing researchers for extensive investigations and predictive experiments, such as testing brain delivery and efficacy of drugs/nanoformulations, reconstructing disease conditions, evaluating immunotherapy responses, mimicking tumor-induced angiogenesis, and studying interactions among tumor and healthy cells. Recent trends include i) biomimicry to improve prediction capabilities (e.g., by incorporating hiPSCs, patient-derived cells, 3D organoids, and tissue-specific ECM matrix components), and ii) sensorization for real-time monitoring and/or high-throughput screening of molecule release (e.g., nanomodulators, nanotransmitters, growth factors, cytokines), receptor expression, cell viability, cell-cell interactions, intracellular phenomena (e.g., calcium waves) and BBB crossing of drugs, nanoparticles, and viruses.

Regarding sensorization, electrical, electrochemical, and optical sensors have benefits and limitations that must be considered for their integration into BoC devices. In Fig. 4, a schematic representation showing integration of different sensors into different compartments of biomimetic BoC has been provided. Electrical sensors are the easiest to integrate but they provide non-specific information. Miniaturization of the electrodes improves spatial resolution but induces high impedance and thus a decreased recording quality. Recent approaches improved the sensitivity by in situ amplifying the produced signal or by using porous conductive materials that increase the surface area and lower the impedance. Implementation of 3D MEAs is also considered for better spatial coverage of 3D models, and the use of thin-film electrodes that are less invasive is very promising for better integration into BoC models [71]. Electrical sensors measuring neural activity are appropriate for the multi-compartmental systems, where the pumped fluid is maintained separated and does not interfere with the working electrode. Their application is particularly appealing for the BoC models developed from human stem cells to monitor their electrophysiologic maturation into neurons. Furthermore, they can be also used with matured neurons to detect their functionality after drug treatment.

Fig. 4. Schematic representation of different sensors integrated into a biomimetic BoC.

Electrochemical sensors exhibit similar characteristics, as they rely on the same principle. However, they require an additional functionalization of the electrodes with specific biological recognition elements, on which the measurement is greatly dependent. Recent studies investigated different approaches to improve the functionalization, allowing miniaturization of the sensors. Electrochemical sensors may be integrated in the presented BoC models in different configurations: i) biosensors can be positioned in the “brain” mimicking compartment for real-time molecule/drug detection after BBB crossing; ii) miniaturized electrochemical sensors, such as in the form of nanoelectrodes, can be implemented in the “blood” compartment to locally detect ROS levels in endothelial cells (e.g., for analyzing the safety of the delivered drug at microcapillary level of the BBB). Another envisaged application of miniaturized electrochemical sensors is the real-time monitoring of the neurodegeneration in pathologic models, such as those mimicking Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and the detection of potential functional rescue with specific treatments. Similarly, the detection of ROS and RNS with miniaturized sensors can be applied to brain tumor-on-a-chip models to monitor 3D tumor response to anticancer drugs.

Optical biosensors are probably the less commonly integrated into BoC models, as they require much more complex techniques and optical read-out systems. However, they are very promising as they are less invasive, they consume few or no analytes, and the sensing area can be miniaturized to a few micrometers. Combining several of the recently developed biosensors into a single microfluidic platform seems to be very promising for improving the real-time monitoring of BoC models in response to drug treatments, and should be the challenge of these next years. Finally, multimodal stimulation and sensing systems have been recently developed for the monitoring of neural circuit responses within engineered 3D neural tissues. An example is the use of 3D MEAs integrated with a small light-emitting diode (LED) for optogenetic neuromodulation and microfluidic channels with pressure-driven drug delivery capabilities [71]. This approach allows for precise mapping of functional connectivity in the entire 3D tissue volume with improved recording performances thanks to the Pt black covering of the electrodes. Such integrated stimulation recording systems represent a valuable tool to study the response of neural tissue functionality to different drugs, and can be potentially applied to both physiologic and pathologic BoC models without the need for further microfluidic integration. The main limit of this delivery system is that it cannot provide direct information on BBB permeability capabilities and drug functionality after BBB crossing; however, this MEA coupled with a delivery system can be potentially downstream connected to a BBB screening device able to provide such functions.

6. Conclusions

BoC and BBB-on-a-chip models will support more and more researchers in the pre-clinical testing of novel therapies for CNS. Thanks to the incorporation of hiPSCs and patient-derived cells in these devices, new patient-tailored approaches can be discovered and tested. Also, signal amplification, miniaturization, and multiplication of the sensors in BoC are the key processes to increase the types of biological phenomena that can be simultaneously detected. The standardization of BoC tests may also simplify and improve the result replicability in different laboratories, which can be complex to obtain in the case of customized bioreactors. Finally, the implementation of miniaturized optical sensors and their combination with genetically-encoded fluorescent indicators, despite being technically challenging, is expected to be the next frontier of BoC, since it would allow monitoring of a plethora of complex biologic phenomena and intracellular pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the European Research Council (MagDock, 101081539) and by the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions program (Theratools, 101073404).

Abbreviations

- eHNP-A1

Apolipoprotein A1

- E-AB

aptamer-beacon-based

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BoC

brain-on-a-chip

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- HAs

human astrocytes

- HBMECs

human brain microvascular endothelial cells

- HBVPs

human brain vascular pericyte

- hESCs

human embryonic stem cells

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- NVU

neurovascular unit

- PEDOT: PSS

poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly (styrenesulfonate)

- TEER

transendothelial electrical resistance

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β 1

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Gianni Ciofani reports financial support was provided by Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia. N/A.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- [1].Amirifar L, Shamloo A, Nasiri R, de Barros NR, Wang ZZ, Unluturk BD, Libanori A, Ievglevskyi O, Diltemiz SE, Sances S, Balasingham I, et al. Brain-on-a-chip: recent advances in design and techniques for microfluidic models of the brain in health and disease. Biomaterials. 2022;285:121531. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOMATERIALS.2022.121531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wadman M. FDA no longer has to require animal testing for new drugs. Science. 2023;379:127–128. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.ADG6276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rossetti AC, Koch P, Ladewig J. Drug discovery in psychopharmacology: from 2D models tocerebral organoids. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21:203. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.2/JLADEWIG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Choe MS, Kim JS, Yeo HC, Bae CM, Han HJ, Baek K, Chang W, Lim KS, Yun SP, Shin IS, Lee MY. A simple metastatic brain cancer model using human embryonic stem cell-derived cerebral organoids. Faseb J. 2020;34:16464–16475. doi: 10.1096/FJ.202000372R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fedorova V, Pospisilova V, Vanova T, Amruz Cerna K, Abaffy P, Sedmik J, Raska J, Vochyanova S, Matusova Z, Houserova J, Valihrach L, et al. Glioblastoma and cerebral organoids: development and analysis of an in vitro model for glioblastoma migration. Mol Oncol. 2023;17:647–663. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scuderi S, Altobelli GG, Cimini V, Coppola G, Vaccarino FM. Cell-to-Cell adhesion and neurogenesis in human cortical development: a study comparing 2D monolayers with 3D organoid cultures. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16:264–280. doi: 10.1016/J.STEMCR.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marino A, Battaglini M, Carmignani A, Pignatelli F, De Pasquale D, Tricinci O, Ciofani G. Magnetic self-assembly of 3D multicellular microscaffolds: a biomimetic brain tumor-on-a-chip for drug delivery and selectivity testing. APL Bioeng. 2023;7:36103. doi: 10.1063/5.0155037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cecen B, Saygili E, Zare I, Nejati O, Khorsandi D, Zarepour A, Alarcin E, Zarrabi A, Topkaya SN, Yesil-Celiktas O, Mostafavi E, et al. Biosensor integrated brain-on-a-chip platforms: progress and prospects in clinical translation. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023;225:115100. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOS.2023.115100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tan HY, Cho H, Lee LP. Human mini-brain models. Nat Biomed Eng. 2020;51:11–25. doi: 10.1038/S41551-020-00643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pediaditakis I, Kodella KR, Manatakis DV, Le CY, Hinojosa CD, Tien-Street W, Manolakos ES, Vekrellis K, Hamilton GA, Ewart L, Rubin LL, et al. Modeling alpha-synuclein pathology in a human brain-chip to assess blood-brain barrier disruption. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5907. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vatine GD, Barrile R, Workman MJ, Sances S, Barriga BK, Rahnama M, Barthakur S, Kasendra M, Lucchesi C, Kerns J, Wen N, et al. Human iPSC-derived blood-brain barrier chips enable disease modeling and personalized medicine applications. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cho A-N, Jin Y, An Y, Kim J, Choi YS, Lee JS, Kim J, Choi W-Y, Koo D-J, Yu W, Chang G-E, et al. Microfluidic device with brain extracellular matrix promotes structural and functional maturation of human brain organoids. Nature Communications. 2021;12:4730. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24775-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Koh I, Cha J, Park J, Choi J, Kang SG, Kim P. The mode and dynamics of glioblastoma cell invasion into a decellularized tissue-derived extracellular matrix-based three-dimensional tumor model. Sci Rep. 2018;81:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22681-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sun D, Gao W, Hu H, Zhou S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:3049–3062. doi: 10.1016/J.APSB.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cai Y, Fan K, Lin J, Ma L, Li F. Advances in BBB on chip and application for studying reversible opening of blood-brain barrier by sonoporation. Micromachines. 2023;14:112. doi: 10.3390/MI14010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Daneman R, Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a020412. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McConnell HL, Mishra A. Cells of the blood-brain barrier: an overview of the neurovascular unit in health and disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2492:3–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2289-6_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liebner S, Dijkhuizen RM, Reiss Y, Plate KH, Agalliu D, Constantin G. Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135:311–336. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1815-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ruck T, Bittner S, Meuth SG. Blood-brain barrier modeling: challenges and perspectives. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:889–891. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.158342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Czupalla CJ, Liebner S, Devraj K. In vitro models of the blood-brain barrier. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1135:415–437. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0320-7_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bagchi S, Chhibber T, Lahooti B, Verma A, Borse V, Jayant RD. In-vitro blood-brain barrier models for drug screening and permeation studies: an overview. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2019;13:3591–3605. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S218708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Srinivasan B, Kolli AR, Esch MB, Abaci HE, Shuler ML, Hickman JJ. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:107–126. doi: 10.1177/2211068214561025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hoffmann A, Bredno J, Wendland M, Derugin N, Ohara P, Wintermark M. High and low molecular weight fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Dextrans to assess blood-brain barrier disruption: technical considerations transl. Stroke Res. 2011;2:106–111. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Malina KC-K, Cooper I, Teichberg VI. Closing the gap between the in-vivo and in-vitro blood-brain barrier tightness. Brain Res. 2009;1284:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Williams-Medina A, Deblock M, Janigro D. In vitro models of the blood-brain barrier: tools in translational medicine. Front Med Technol. 2021;2 doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2020.623950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yoon JK, Kim J, Shah Z, Awasthi A, Mahajan A, Kim YT. Advanced human BBB-on-a-chip: a new platform for Alzheimer’s disease study. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10:e2002285. doi: 10.1002/ADHM.202002285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xu S, Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang K, Liang W, Xu Z, Wu Y, Luo J, Zhuang C, Cai X. Recent progress and perspectives on neural chip platforms integrating PDMS-based microfluidic devices and microelectrode arrays. Micromachines. 2023;14 doi: 10.3390/MI14040709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ahn SI, Sei YJ, Park H-J, Kim J, Ryu Y, Choi JJ, Sung H-J, MacDonald TJ, Levey AI, Kim Y. Microengineered human blood-brain barrier platform for understanding nanoparticle transport mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2020;11:175. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee S, Chung M, Lee S-R, Jeon NL. 3D brain angiogenesis model to reconstitute functional human blood-brain barrier in vitro. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2019;117:748–762. doi: 10.1002/bit.27224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Seo S, Nah S-Y, Lee K, Choi N, Kim HN. Triculture model of in vitro BBB and its application to study BBB-associated chemosensitivity and drug delivery in glioblastoma. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32:2106860. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202106860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grillone A, Battaglini M, Moscato S, Mattii L, de Julian Fernandez C, Scarpellini A, Giorgi M, Sinibaldi E, Ciofani G. Nutlin-loaded magnetic solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted glioblastoma treatment. Nanomedicine. 2019;14:727–752. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shin Y, Choi SH, Kim E, Bylykbashi E, Kim JA, Chung S, Kim DY, Kamm RD, Tanzi RE. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in a 3D in vitro model of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Sci. 2019:1900962. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lyu Z, Park J, Kim K-M, Jin H-J, Wu H, Rajadas J, Kim D-H, Steinberg GK, Lee W. A neurovascular-unit-on-a-chip for the evaluation of the restorative potential of stem cell therapies for ischaemic stroke. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:847–863. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00744-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Palma-Florez S, Lopez-Canosa A, Moralez-Zavala F, Castaño O, Kogan MJ, Samitier J, Lagunas A, Mir M. BBB-on-a-chip with integrated micro-TEER for permeability evaluation of multi-functionalized gold nanorods against Alzheimer’s disease. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:115. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lenoir S, Lahaye RA, Vitet H, Scaramuzzino C, Virlogeux A, Capellano L, Genoux A, Gershoni-Emek N, Geva M, Hayden MR, Saudou F. Pridopidine rescues BDNF/TrkB trafficking dynamics and synapse homeostasis in a Huntington disease brain-on-a-chip model. Neurobiol Dis. 2022;173:105857. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lauranzano E, Campo E, Rasile M, Molteni R, Pizzocri M, Passoni L, Bello L, Pozzi D, Pardi R, Matteoli M, Ruiz-Moreno A. A microfluidic human model of blood-brain barrier employing primary human astrocytes. Adv Biosyst. 2019;3:e1800335. doi: 10.1002/adbi.201800335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cakir B, Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Kural MH, Parent M, Kang Y-J, Chapeton K, Patterson B, Yuan Y, He C-S, Raredon MSB, Dengelegi J, et al. Engineering of human brain organoids with a functional vascular-like system. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ahn Y, An J-H, Yang H-J, Lee DG, Kim J, Koh H, Park Y-H, Song B-S, Sim B-W, Lee HJ, Lee J-H, et al. Human blood vessel organoids penetrate human cerebral organoids and form a vessel-like system. Cells. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/cells10082036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kassianidou E, Simonneau C, Gavrilov A, Villasenor R. High throughput blood-brain barrier organoid generation and assessment of receptor-mediated antibody transcytosis. Bio-Protocol. 2022;12:e4399. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bergmann S, Lawler SE, Qu Y, Fadzen CM, Wolfe JM, Regan MS, Pentelute BL, Agar NYR, Cho C-F. Blood-brain-barrier organoids for investigating the permeability of CNS therapeutics. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:2827–2843. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0066-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Campisi M, Shin Y, Osaki T, Hajal C, Chiono V, Kamm RD. 3D self-organized microvascular model of the human blood-brain barrier with endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Biomaterials. 2018;180:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lee SWL, Campisi M, Osaki T, Possenti L, Mattu C, Adriani G, Kamm RD, Chiono V. Modeling nanocarrier transport across a 3D in vitro human blood-brain-barrier microvasculature. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2020;9:1901486. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201901486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Marino A, Tricinci O, Battaglini M, Filippeschi C, Mattoli V, Sinibaldi E, Ciofani G. A 3D real-scale, biomimetic, and biohybrid model of the blood-brain barrier fabricated through two-photon lithography. Small. 2018;14:1702959. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tricinci O, De Pasquale D, Marino A, Battaglini M, Pucci C, Ciofani G. A 3D biohybrid real-scale model of the brain cancer microenvironment for advanced in vitro testing. Adv Mater Technol. 2020;5:2000540. doi: 10.1002/admt.202000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Fuchs S, Johansson S, Tjell A, Werr G, Mayr T, Tenje M. In-line analysis of organ-on-chip systems with sensors: integration, fabrication, challenges, and potential. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7:2926–2948. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liu NC, Liang CC, Li YCE, Lee IC. A real-time sensing system for monitoring neural network degeneration in an Alzheimer’s disease-on-a-chip model. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS14051022/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Palma-Florez S, Lopez-Canosa A, Moralez-Zavala F, Castano O, Kogan MJ, Samitier J, Lagunas A, Mir M. BBB-on-a-chip with integrated micro-TEER for permeability evaluation of multi-functionalized gold nanorods against Alzheimer’s disease. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;211:21. doi: 10.1186/S12951-023-01798-2,1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mir M, Palma-Florez S, Lagunas A, Lopez-Martínez MJ, Samitier J. Biosensors integration in blood-brain barrier-on-a-chip: emerging platform for monitoring neurodegenerative diseases. ACS Sensors. 2022;7:1237–1247. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.2c00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Guo C, Li Z, Duan F, Zhang Z, Marchetti F, Du M. Semiconducting CuxNi3—x (hexahydroxytriphenylene)2 framework for electrochemical aptasensing of C6 glioma cells and epidermal growth factor receptor. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:9951–9960. doi: 10.1039/D0TB01910K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Shaver A, Mahlum JD, Scida K, Johnston ML, Aller Pellitero M, Wu Y, Carr GV, Arroyo-Curras N. Optimization of vancomycin aptamer sequence length increases the sensitivity of electrochemical, aptamer-based sensors in vivo. ACS Sensors. 2022;7:3895–3905. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.2c01910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ji X, Lin X, Rivnay J. Organic electrochemical transistors as on-site signal amplifiers for electrochemical aptamer-based sensing. Nat Commun. 2023;141:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Salim S. Oxidative stress and the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2017;360:201. doi: 10.1124/JPET.116.237503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fischer R, Maier O. Interrelation of oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease: role of TNF. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:610813. doi: 10.1155/2015/610813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhao S, Zang G, Zhang Y, Liu H, Wang N, Cai S, Durkan C, Xie G, Wang G. Recent advances of electrochemical sensors for detecting and monitoring ROS/RNS. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021;179:113052. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOS.2021.113052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dou B, Yang J, Yuan R, Xiang Y. Trimetallic hybrid nanoflower-decorated MoS2 nanosheet sensor for direct in situ monitoring of H2O2 secreted from live cancer cells. Anal Chem. 2018;90:5945–5950. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hu K, Liu YL, Oleinick A, Mirkin MV, Huang WH, Amatore C. Nanoelectrodes for intracellular measurements of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in single living cells. Curr Opin Electrochem. 2020;22:44–50. doi: 10.1016/J.COELEC.2020.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang K, Sun Y, Xu W, Zhang W, Zhang F, Qi Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Q, Dong B, Li C, Wang L, et al. Non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of H2O2 by assembly of CuO nanoparticles and black phosphorus nanosheets for early diagnosis of periodontitis. Sensor Actuator B Chem. 2022;355:131298. doi: 10.1016/J.SNB.2021.131298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lu Q, Liang X, Lu G, Liu F, Wang J. Non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide electrochemical sensors based on reduced graphene oxide. J Electrochem Soc. 2020;167:037531. doi: 10.1149/1945-7111/AB644A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chen X, Gao J, Zhao G, Wu C. In situ growth of FeOOH nanoparticles on physically-exfoliated graphene nanosheets as high performance H2O2 electrochemical sensor. Sensor Actuator B Chem. 2020;313:128038. doi: 10.1016/J.SNB.2020.128038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shu Y, Zhang W, Yin X, Zhang L, Yang Y, Ma D, Gao Q. Efficient electrochemical biosensing of hydrogen peroxide on bimetallic Mo1-xWxS2 nanoflowers. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;566:248–256. doi: 10.1016/J.JCIS.2020.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Li Y, Huan K, Deng D, Tang L, Wang J, Luo L. Facile synthesis of ZnMn2O4@ rGO microspheres for ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide from human breast cancer cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:3430–3437. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b19126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wang M, Wang C, Liu Y, Hu B, He L, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Cui B, Du M. Nonenzymatic amperometric sensor for hydrogen peroxide released from living cancer cells based on hierarchical NiCo2O4-CoNiO2 hybrids embedded in partially reduced graphene oxide. Microchim Acta. 2020;187:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00604-020-04419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Balasubramanian P, Bin He S, Jansirani A, Deng HH, Peng HP, Xia XH, Chen W. Oxygen vacancy confined nickel cobaltite nanostructures as an excellent interface for the enzyme-free electrochemical sensing of extracellular H2O2 secreted from live cells. New J Chem. 2020;44:14050–14059. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ03281F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Oh DE, Lee C-S, Kim TW, Jeon S, Kim TH. A flexible and transparent PtNP/ SWCNT/PET electrochemical sensor for nonenzymatic detection of hydrogen peroxide released from living cells with real-time monitoring capability. Biosensors. 2023;13:704. doi: 10.3390/BIOS13070704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kincses A, Vigh JP, Petrovszki D, Valkai S, Kocsis AE, Walter FR, Lin H-Y, Jan J-S, Deli MA, Der A. The Use of Sensors in Blood-Brain Barrier-On-A-Chip Devices: Current Practice and Future Directions. Biosensors. 2023;13:3572023. doi: 10.3390/bios13030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bi X, Beck C, Gong Y. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicators for imaging brain chemistry. Biosensors. 2021;11:116. doi: 10.3390/BIOS11040116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Shemetov AA, Monakhov MV, Zhang Q, Ernesto Canton-Josh J, Kumar M, Chen M, Matlashov ME, Li X, Yang W, Nie L, Shcherbakova DM, et al. A near-infrared genetically encoded calcium indicator for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:368–377. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0710-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Su SH, Song Y, Stephens A, Situ M, McCloskey MC, McGrath JL, Andjelkovic AV, Singer BH, Kurabayashi K. A tissue chip with integrated digital immunosensors: in situ brain endothelial barrier cytokine secretion monitoring. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023;224:115030. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOS.2022.115030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Petrovszki D, Walter FR, Vigh JP, Kocsis A, Valkai S, Deli MA, Der A. Penetration of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein across the blood-brain barrier, as revealed by a combination of a human cell culture model system and optical biosensing. Biomedicines. 2022;10:188. doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES10010188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shin H, Jeong S, Lee JH, Sun W, Choi N, Cho IJ. 3D high-density microelectrode array with optical stimulation and drug delivery for investigating neural circuit dynamics. Nat Commun. 2021;121:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.