Abstract

Despite over 50 years of messaging about the reality of human-caused climate change, significant portions of the population remain sceptical. Furthermore, many sceptics remain unmoved by standard science communication strategies such as myth-busting and evidence-building. To understand this, we examine psychological and structural reasons why climate change misinformation is prevalent. First, we review research on motivated reasoning: how interpretations of climate science are shaped by vested interests and ideologies. Second, we examine climate scepticism as a form of political followership. Third, we examine infrastructures of disinformation: the funding, lobbying, and political operatives that lend climate scepticism its power. Guiding this review are two principles: (1) to understand scepticism one must account for the interplay between individual psychologies and structural forces, and (2) global data are required to understand this global problem. In a spirit of optimism, we finish by describing six strategies for reducing the destructive influence of climate scepticism.

Decades ago, scientists reached consensus that human activities are changing the Earth’s climate, and that these changes will have dramatic, largely negative consequences. This message has been a prominent and persistent feature of the global conversation, occupying policy makers at all levels. Nonetheless, a sizeable – and frequently vocal – minority of the population continues to argue that the scientists are wrong. At the turn of the century, the main contrarian claim was that temperatures are not rising1. A sequence of record-breaking global temperatures during the next two decades forced a shift in the narrative of climate sceptics: yes, temperatures are rising, but human activities are not a primary cause of it2. Over time, new elements were added to the spectrum of arguments: that climate change will be benign, that the issue has been exaggerated, or that known mitigation methods are ineffective2,3. What unites these arguments is three features: (1) they defy the overwhelming scientific consensus, (2) they slow our collective ability to respond to the climate crisis, and (3) the number of people who hold them is too big to ignore. For example, in Australia (a world-leading exporter of coal) and the U.S. (the second biggest carbon emitter in the world) roughly a third of the population maintains that climate change is not predominantly caused by humans4–6. Surveys from South America indicate wide variability in levels of scepticism across nations, but 40-50% of respondents in Honduras, Dominican Republic, and Ecuador agreed with the statement “Climate change is not a problem”7.

In trying to understand this phenomenon, one line of thought subscribes to a deficit argument: perhaps climate change scepticism is due to lack of education or scientific literacy. Research suggests a kernel of truth in this argument, and there is a long history of finding positive effects of interventions designed to address information deficits8,9. However, the effects of education and science literacy are relatively modest10,11, and “classic” science communication strategies —ones that rely on myth-busting or easily digestible distillations of scientific conclusions – have had limited effects on sceptics12,13. On that basis, scholars have long understood that facts alone would not be sufficient to dispel climate scepticism: what is needed is a broader set of understandings of the psychology of climate scepticism.

This paper aims to de-mystify two urgent questions: why are so many people sceptical of climate science, and what can be done about it? First, we focus on climate scepticism as motivated reasoning: how people’s interpretations of evidence are influenced by underlying vested interests, ideologies, and worldviews. Second, we examine climate scepticism as an intergroup phenomenon: an expression of political followership. Third, we examine the infrastructure of disinformation that lends climate scepticism its power: the funding, lobbying, and campaigning that has super-sized climate scepticism from being an “argument” into being a movement. In the final section —and in a spirit of optimism — we examine strategies for reducing the damage associated with climate scepticism.

Before beginning, we note that we use the term “scepticism” to include what some scholars refer to as “denial”9. The difference between terms is largely about tone and politics: climate science contrarians believe the term “denier” is stigmatising and resent the fact that it presumes an objective truth which they dispute. Many climate change scholars resent that the term “sceptic” is being appropriated by people with rigid and non-sceptical belief systems, used in opposition to a scientific method that is inherently sceptical and inquisitive about truth14,15. Although our sympathies lie with the latter argument, we use the term “climate scepticism” in this paper in acknowledgement of the fact that it has a broader and more flexible implication, incorporating a range of views from outright rejection of climate trends to more nuanced arguments about the effectiveness of mitigation measures.

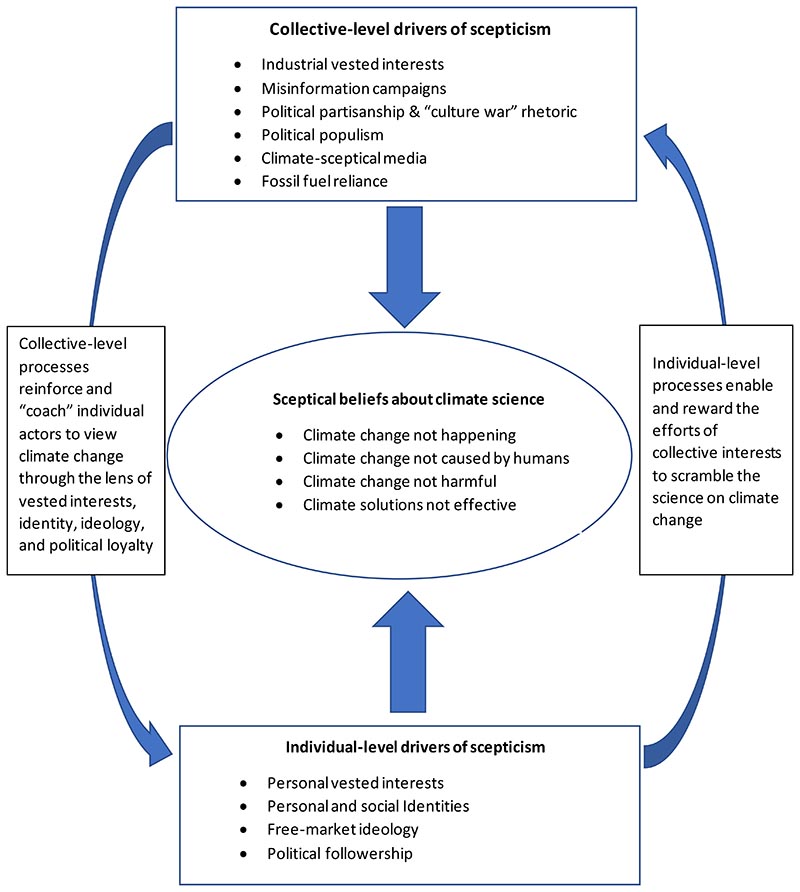

Furthermore, this paper construes climate scepticism as a multi-level belief system: one that resides “under the skull” of individual community members but also one that is manufactured at the macro-level of media, industry, political operatives, and government. In this review we toggle between the micro- and the macro-level of understanding, but we emphasise that these levels are interdependent and mutually reinforcing (see Fig. 1 for an articulation of how collective-level and individual-level factors reinforce each other to shape climate scepticism).

Figure 1. The interplay between individual and collective influences on climate scepticism.

Climate scepticism as motivated reasoning

Classically, human reasoning was thought to operate something like this: a person gathers all the evidence they can find and assimilates it in an unbiased and dispassionate way. Once that process is complete (and only then), the person reaches a conclusion. Indeed, most people do their best to follow a rational process, and ensure that their reasoning process is directed by the goal to be accurate.

For the last 50 years, however, social science research has revealed important exceptions to this rule. Rather than drawing conclusions after examining data, in some cases the causal order is reversed: people reach conclusions first, and then select, critique, and remember evidence in a biased way with the goal of buttressing their conclusion (more like a cognitive lawyer than a cognitive scientist)16–18. When Simon and Garfunkel sang “a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest”, they were describing motivated reasoning.

The notion of motivated reasoning – as a process of rationalising conclusions already reached – is transformative because it changes the critical question. Rather than asking “Why do people reject climate science?” the more important question becomes “Why would people want to reject climate science”? Any answer to that question helps understand the climate scepticism problem, as well as providing clues on how to solve it.

One pragmatic answer to the question is vested interests: for some, climate change is an “inconvenient truth” in that it implies painful sacrifice19. It is psychologically unrealistic to expect that anybody could appraise climate science with perfect objectivity, but it might be especially unrealistic when change is painful (e.g., for individuals whose livelihood is reliant on fossil fuel industries, or for people with a large carbon footprint that is costly to shrink). Rather than engaging with solutions that are painful, it may be easier to reject the science20 by embracing slivers of scientific dissent, clinging to baseless conspiracy theories, or shifting standards of proof as a function of how convenient the evidence is. This escape into denial from painful solutions is widely discussed in the climate change literature21, and the principle has also been documented elsewhere: smokers are more likely to deny science on the negative health effects of smoking22,23 and coffee-drinkers are more likely to deny science on the negative health effects of caffeine24.

For others, climate change is an inconvenient truth not because it costs them materially, but because the implications of the science upset their ideological worldview20,25,26. Meta-analyses of the predictors of accepting anthropogenic climate change10 show that the biggest correlates are not education (r = .12, i.e., modest positive association between education and acceptance), self-reported science literacy (r = .18) or personal experiences of extreme weather events (r = .05), but rather values-driven ideologies that ostensibly have nothing to do with science or climate. This includes where one stands on the extent to which individual freedoms should be prioritised over the interests of the collective (r = -.28, i.e., negative association between prioritising individual freedoms and accepting climate science), tolerance for status and power hierarchies (r = -.26) and belief in the sanctity of the free market (r = -.30). These associations likely reflect the fact that mitigating climate change is often construed as requiring Big Government solutions designed to regulate the freedoms of individuals and businesses27,28. Rather than aligning with solutions people find ideologically objectionable, the temptation is to reject science that suggests these solutions are necessary (a phenomenon referred to as “solution aversion”)20.

Climate scepticism as political followership

Climate change beliefs are situated within broader intergroup contexts, reflecting and creating societal schisms29. The contested, “them-against-us” nature of the climate change debate exists in many forms, but the societal faultline that has attracted by far the most research attention (and seems deepest, particularly in fossil fuel reliant countries) is around political identity.

In a study that was conducted well before political polarisation became a zeitgeist topic, Cohen30 showed political partisans in the U.S. a draft welfare policy. Although all participants received the same policy, they were told it was drafted by either Republicans or Democrats. Participants responded as one might expect: when the welfare policy was drafted by their own political ingroup they evaluated it more positively than when the same policy was drafted by the outgroup. What was striking, though, was the magnitude of the effects. Depending on whose policy they thought they were reading, participants veered dramatically between presuming the policy would be effective or ineffective; moral or immoral.

The notion that perceptions of reality are filtered through the lens of group loyalties is not surprising to social identity theorists31,32. When intergroup identities are salient, people internalise the “party line” through processes that are both cognitive (psychological assimilation to ingroup attitudes and values; psychological contrasting with those of the outgroup) and motivational (the desire to preserve a positive identity that is distinct from rival outgroups). So when a scientific issue gets drawn into the culture wars – one that differentiates between political identities – that issue can get sucked into a self-reinforcing feedback loop of political polarisation. Once this has occurred, beliefs may reflect more of an identity-expressive motive than an accuracy motive, and so “facts” become rubbery and subjective.

In some countries, climate science has had the misfortune of being drawn into these culture wars. In their historical analysis of the scrambling of climate science in the U.S., Oreskes and Conway33 highlighted that the original contrarians were nuclear scientists who themselves had strong conservative (anti-communist) attitudes. Their minority views were amplified by conservative think tanks, which in turn were financially supported by elements of the fossil fuel industry34. Drawn to the ideological implications of climate scepticism – a commitment to free markets, economic growth, and individual freedoms – the message was adopted by some conservative politicians and by elements of the conservative media.

By the 2000s, a degree of climate scepticism became “baked in” to the cluster of arguments that describe and prescribe one’s political loyalties as conservative in some countries. In the 2015 Republican primaries, only a minority of the candidates were on the record as accepting the reality of human-caused climate change35. The winner, Donald Trump, explicitly embraced the language of climate denial, referring to climate change as a hoax invented by China36. In Australia, two conservative Prime Ministers in the 2010s expressed their distaste for action on climate, either verbally (describing climate science as “absolute crap”) or symbolically (carrying a chunk of coal into Parliament and admonishing MPs not to be afraid of it). Within weeks of taking office, Brazil’s conservative President Jair Bolsonaro dismantled several government divisions dedicated to climate change and named openly climate-sceptical Cabinet members37.

It should not be surprising, then, that political conservatism is one of the most-replicated and most-discussed predictors of climate scepticism in the literature4,25,38–42. Meta-analyses show that the biggest demographic predictor of climate scepticism is whether people plan to vote for the Left or the Right; far more so than age, sex, race, and education10. People’s beliefs and attitudes about climate science became a shorthand way of signalling political loyalty. This raises the possibility that people are not always making up their mind about climate science themselves but are rather “taking their cues” from elites within the political party with which they identify.

Consistent with this notion, longitudinal analyses showed that climate concern in the U.S. shifted reliably as a function of elite cues, such as whether a respondent’s Congressional representative had joined the Tea Party Caucus, press releases on climate change issued by Republicans and Democrats, and Fox News coverage43-46. In Australia, data from 2009-2019 show that climate scepticism ebbed and flowed reliably as a function of political support for conservative political parties4.

There are three interesting sidenotes to the literature on political identification and climate scepticism. First, as elaborated later, there are dramatic differences internationally in the extent to which political conservatism is associated with people’s climate change beliefs, and in fact the relationship is robust in only a subset of nations.

Second, in the U.S. in particular, evidence for political polarisation is greater among respondents who are more educated and science-literate47-52. On one hand, this seems surprising: one might think that education and science literacy would give people the analytic skills to look beyond group loyalties and appraise evidence objectively. But from a psychological point of view, the pattern is not so surprising. Equipped with the scientific nous to know how to find convenient truths – and to dismiss inconvenient truths – the highly educated are better equipped to engage in motivated reasoning, curating their own informational reality53. Furthermore, the highly educated are more attuned to ideological and policy differences between political parties, making them more sensitive to elite cues48.

Third, historical analyses suggest that the conservative turn against climate science (and science in general) is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early 1970s, conservatives in the U.S. had greater trust in science than liberals11 and in the 1990s, highly educated conservatives were more likely than highly educated liberals to believe there was scientific consensus about anthropogenic climate change52. After climate change started to be represented in the media as a partisan issue, both trends dramatically reversed40,54,55. To further understand this process, one needs to move beyond the notion of climate scepticism being solely an individual’s failure to appraise evidence, and to examine the extent to which individuals are responding to organized campaigns of disinformation.

Climate scepticism as organized disinformation

The European landscape

There is overwhelming evidence that disinformation about climate change is disseminated in a co-ordinated manner through well-funded, often global networks. Several recent reviews provided detailed analyses of the American landscape9,56. Highlights of this landscape include the findings that: (a) most environmentally sceptical books are published or financed by conservative think tanks57,58, (b) funding of climate-denying think tanks and advocacy organizations is approximately $900 million annually59, and (c) the fossil fuel industry was aware of the anticipated consequences of climate change as early as 1965 but continued to deny its existence in public for decades, as revealed by a comparison of ExxonMobil’s internal and external communications60.

By comparison, there has been less research on organized climate denial in Europe and we know of no reviews of those efforts. Analysing contrarian efforts in Europe is of particular interest because of the striking differences between the American and European political scenes and public opinion landscapes. Although there is considerable heterogeneity among European countries, these societies are generally less politically polarised than the U.S. In most European countries, all mainstream political parties subscribe to the scientific consensus on climate change, and at least until recently, rejection of climate science represented a “fringe” opinion61. This is particularly true in Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, which is considered a leader in the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables62.

One consequence of the broad acceptance of climate science across the European mainstream is that explicit denial groups are more marginalised63. This marginalisation has softened somewhat since the recent electoral successes of far-right parties across Europe, which has created space for the public expression of climate scepticism. For example, the fraction of the German public who disagreed that the climate is changing has risen from 7% in 2011 to 16% in 201761. This increase coincided with the success of fossil fuel groups in removing feed-in tariffs for solar energy in the second half of the 2010s62. Intriguingly, the key players engaged in lobbying against climate-friendly policies (such as feed-in tariffs) tend to nominally embrace the reality of climate change and limit their arguments to politics and policies64. This is unlike the U.S., where organizations that oppose specific climate policies are also typically rejecting and misrepresenting the science65. Rejection and misrepresentation of science in Europe is confined to a small but vocal set of organizations whose influence is modest63.

One such organization, the German-based EIKE, is a think tank with close links to the Heartland Institute in the U.S. and to the far-right AfD party in Germany61. Although EIKE claims to be funded only through voluntary contributions, it refuses to reveal funders and several investigations have pointed at financial support from equivalent American organizations66. EIKE has contributed to hearings about climate science in the German parliament at the invitation of the AfD, thus establishing a “counter-public” by creating the appearance of a scientific debate using “expert” testimony. Analysis of EIKE’s public-facing outputs (more than 1,000 texts between 2015-2018) reveals that most texts seek to discredit scientists and climate campaigners so as to undermine their message66.

The strategies employed by EIKE are mirrored by similar organizations across Europe. An examination of 8 major European think tanks in 6 countries found that they used counter-frames that mainly questioned the science of climate change (50% of the time) and the legitimacy of the IPCC (30%)63. The aggressive rhetoric of these European organizations parallels that of their American counterparts, although unlike the U.S. their political influence is limited61.

Political influence in Europe is instead exercised by institutions that, like most of their corporate funders, at least pay lip service to the reality of climate change and the need for mitigation67. Instead of denying the science, public-relations and lobbying activities therefore focus on diluting effective climate policies or cloaking climate-harming activities with a green sheen67. For example, the gas industry has successfully positioned itself as a “transition fuel”, which the European Union has mainly accepted. Similarly, carbon capture technologies have attracted considerable public funding even though they have yet to deliver meaningful climate mitigation67.

At a cross-European level, Plehwe62,64 has identified the Center for European Policy as a notable player in eroding confidence in the transition to renewable energy. This Center focuses on European stipulations and was instrumental in creating doubt about the legality of (the highly successful) feed-in tariffs for solar energy in Germany. Plehwe62 lists several other transnational institutions that pursue industry-friendly positions to undermine the transition to renewables. Several of those organizations are part of the global Atlas network, which is also at the core of American climate sceptic organisations56.

In Germany, marginalisation of climate scepticism and sizable opposition to fossil-fuel driven capitalism has forced the energy industry and its allies to move away from pure status-quo protection and embrace modest reformism62. This position nominally acknowledges the need to transition to renewable energy but in reality seeks to slow the transition by opposing effective policies. The organisations involved in those efforts keep their distance from explicit denial organisations and the far right, and instead court or co-opt reputable academic institutions to develop alternative policy proposals and narratives. Those narratives claim to improve the transition with greater efficiency and savings in cost (e.g., by introducing market-based mechanisms rather than set feed-in tariffs) but in effect have slowed the transition for several years64. This is not surprising given that purely market-based solutions have a history of being less effective than their proponents claim68.

Global perspectives on climate scepticism

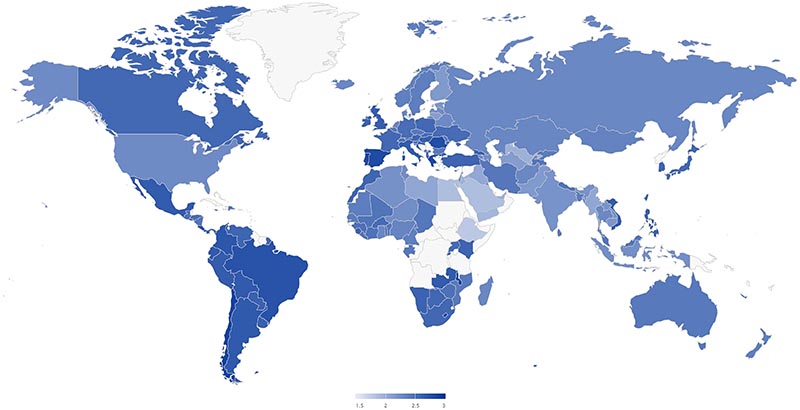

As reflected in Fig. 2, there are wide differences globally in the extent to which members of different nations perceive climate change to represent a threat to their country69. Despite this, the vast majority of research on climate scepticism has emerged from so-called WEIRD samples (i.e., from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic nations), with reviews revealing that approximately half of studies were conducted in the U.S., UK., and Australia alone10,70. This disproportionate emphasis on the highly industrialised West may simply reflect a broader problem within the social sciences, where non-Western voices remain under-represented. Another possibility is that, because Western wealth construction is one of the biggest contributors to climate change, researchers considered the Western response to the challenge as particularly critical to the construction of effective solutions. However, given that it is in the Global South that the effects of climate change will be most severe, the marginalisation of non-WEIRD voices in the literature is especially unfortunate71.

Figure 2.

Perceptions of the level of threat climate change presents to each nation, as reported in Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll (2021). Darker shades represent greater perceived threat (scores from the poll were reversed such that 1 = not a threat at all, 2 = somewhat serious threat, 3 = very serious threat).

Having said that, there is important work that has taken a cross-national approach to understanding climate change attitudes, and in so doing provides a more global perspective on this global problem. Early commentary in this space focused on the so-called post-materialism hypothesis: the notion that richer nations are the ones that are most likely to embrace progressive social movements such as environmentalism because they are more likely to have satisfied their material needs for physical and economic security72. Contrary to this hypothesis, some international surveys suggest that concern about climate change is greater in nations with relatively low GDP per capita73,74 and with relatively low per capita carbon emissions75.

Another approach to examining international patterns relies on content analyses of print media. These analyses suggest that it is only in a handful of countries that the media had distorted the scientific consensus around climate change into an ideologically charged “debate”: most strikingly in Australia, the U.S., and the U.K.76,77. Newspaper analysis of 27 nations indicated that media coverage of climate change (regardless of whether it was sceptical or not) was particularly pronounced in fossil fuel-producing nations that had made commitments under the Kyoto Protocol77. In other words, media coverage of the issue appears to be greatest among the nations for which there are strongest vested interests at play (i.e., the economic costs of decarbonisation are particularly acute).

Fossil fuel reliance also appears to be a factor in understanding the role of political ideology in shaping climate scepticism. In a correlational study among 25 nations, the relationship between conservatism and climate scepticism was strongest in the U.S. and second strongest in Australia78. For several countries – such as Brazil and Canada – the effects were still reliable but weaker and more variable. But for approximately three-quarters of nations (including China) the relationship was not statistically reliable at all. Interestingly, the role of conservatism in determining climate attitudes increased in lockstep with per capita carbon emissions of the nation, an index that is strongly geared toward fossil fuel production. This suggests that the link between political conservatism and climate scepticism only emerges when the stakes of decarbonising are high.

Secondary analyses of international data sets have also revealed interesting patterns involving education. In nations who are low- to mid-ranking on the Human Development Index there is a “common sense” education effect such that more educated respondents are less climate sceptical. In countries ranking highly in the Human Development Index, however, this relationship is attenuated by right-wing ideology, suggesting that ideology trumps education51. This adds to the general global picture; that in less affluent nations (and/or in nations with a less active fossil fuel industry), acceptance of climate change is less prone to ideological influence.

As datasets become more global over time, it is inevitable that these broad-brush understandings of international patterns will be supplemented by more nuanced, country-specific analyses. One interesting pattern already emerging is that conventional left-right political identification predicts climate change attitudes more in Western European countries than in Central and Eastern European countries79-81. Analysis of former Communist countries, in particular, indicates that not all left-wing contexts are aligned with pro-environmental orientations82.

In seeking new, global understandings of how political ideology might influence climate change attitudes, some researchers have focused on the international rise of populism. Although these analyses have typically focused on right-wing populist parties, the notion of populism transcends left-right distinctions to describe a political worldview defined by institutional distrust and a binary good-versus-evil division between “ordinary people” (who are pure and virtuous) and malevolent “elites” or the “establishment” (corrupt, amoral). To the extent that scientists or environmentalists are characterised as elites, this worldview provides a platform for discrediting climate science, often with the help of elaborate conspiracy theories. These dynamics have been described across several case studies (e.g., in Scandinavia)83 and empirically, it is well-established that scepticism is higher among supporters of European right-wing populist parties84,85. Analyses in Austria confirm that the link between populism and climate scepticism is explained in part by generalised distrust of science and political institutions86.

Interventions for reducing damage caused by climate scepticism

In this review we canvassed (a) individual factors that render people susceptible to rejecting climate science, and (b) organized dissemination of misinformation and contrarian lobbying efforts. Any interventions must target those two levels. Although the solutions to politically-motivated opposition must also be political—and hence is largely beyond our scope—the recommendation by Michaels and Ainger67 that the revolving door between lobbyists and governments or the EU must be shut seems an obvious first step. The World Health Organization successfully created an explicit firewall between health policy making and the tobacco industry in 200767, and the creation of a similar firewall between fossil-fuel interests and climate policy making is an advisable political goal for the 2020s.

Other structural interventions are already underway. In some carbon-intensive sectors, reluctant organizations are being corralled into action by international trade regulations such as the European Climate Law. For governments and fossil-fuel industries, there is the growing threat of climate change-related litigation87, with everything that implies both legally and in terms of personal and corporate legacies. Powerful activist investors are creating real change from within organizations to improve environmental performance88 and there is evidence that firms meeting expectations around environmental responsibility perform better and receive more investment money89. Note that these drivers of change are not necessarily driven by a sea-change in community attitudes and do not rely on the notion of “converting” sceptics to the cause. Rather, they are the results of politicians, regulators, judges, and policy makers wielding hard power.

Turning to the individual level, interventions range from the long-term mission to build critical literacy in the population90 to a variety of short-term communication techniques. Because climate change is a time-sensitive crisis, long-term educational efforts are insufficient and scholars have been forced to think flexibly about strategies to reduce the damage associated with climate scepticism, both before and after misinformation takes seed in people’s minds. Below, we highlight six strategies for doing so (see Table 1 for a summary). Note that we only consider communication strategies that adhere to the TARES principles of ethical communication91; that is, the strategy must exhibit Truthfulness of the message, Authenticity of the messenger, Respect for the recipient, Equity and fairness of communication, and Social responsibility for the common good.

Table 1. Six strategies for reducing the damaging effects of climate scepticism.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Appealing to sceptics through value-based frames | In many nations, climate scepticism is particularly strong among conservatives. For this subset of the population, climate change messages will be more effective if they are framed in ways that are congenial to conservative values (e.g., as reinforcing energy security, as a way of maintaining a way of life, as an expression of individual responsibility). |

| Appealing to sceptics through co-benefits | Given that they dispute humans are causing climate change, sceptics may not be influenced by traditional messages that focus on the importance of action to save the environment. However, they may be influenced by arguments that focus on the co-benefits of action in terms of promoting green jobs, stimulating technological innovation, or maintaining public health. |

| Leveraging climate-friendly actors within the conservative movement | Conservatives are more likely to be persuaded about the reality and urgency of climate change if those messages are presented by respected figures within the conservative movement. |

| Establishing norms | People are more likely to act in a certain way if they perceive – or are told – that valued others are acting in that way. Because they appeal to our social nature, norms-based interventions can have positive effects independent of political persuasion. |

| Consensus messaging | 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is happening and is largely caused by humans. Successfully communicating that consensus message has positive downstream influences on climate-friendly attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours. |

| Embedding climate-friendly actions in social practice | Positive action is more likely if those actions are embedded in a network of social practices, so that it becomes part of the flow of one’s day and part of one’s social life. |

Appealing to sceptics through value-based frames

As discussed earlier, many people embrace climate scepticism as an expression of ideological concern rather than as a result of cognitive reflection on evidence or arguments. Because sceptics nonetheless give the impression that they are talking about evidence (albeit in a flawed way92,93) the communication landscape is confusing and requires an indirect approach. Rather than focusing on the “surface” attitudes and beliefs that sceptics express – discussing solar flares and so forth – scholars have argued that it is preferable to attend to the underlying motivations for wanting to embrace those arguments (the so-called “attitude roots”)19. If climate messages are aligned with sceptics’ underlying attitude roots, they are more likely to be listened to, and more likely to shape attitudes and behaviour. Strategies like this have been described using various terms such as values-based frames, attitude matching, and jiu jitsu persuasion.

Given that climate scepticism has been reliably traced back to conservative worldviews in fossil-fuel reliant countries such as the U.S., U.K., and Australia, the implication is simple: when addressing sceptics, the need to mitigate climate change might be best framed in a way that resonates with conservative worldviews. Consistent with this, sceptics are indeed more likely to embrace the need for pro-environmental action when the fight against climate change is expressed using traditionally conservative values: as a way of protecting national security, as a way of protecting a traditional way of life, as a patriotic act, or as an expression of individual responsibility94–100. Conservatives are also more likely to accept climate science if the solutions are designed to be compatible with free markets20,101. Once convinced that mitigation does not necessarily require the Big Government regulations to which they ideologically object, conservatives’ motivation to reject the science diminishes.

Appealing to sceptics through co-benefits

Fundamentally, sceptics do not accept that humans are the primary cause of climate change, so messages that focus on the importance of action – or the dangers of inaction – can be easily dismissed. Furthermore, attempts to explain the link between human action and climate change are likely to meet the ideological headwinds just discussed. This has led some scholars to advocate for a suite of arguments that do not rely on accepting that climate change is real and important102,103. According to this approach, positive change can flow by articulating the co-benefits of working to mitigate climate change, independently of whether these efforts actually influence the climate. Examples of these co-benefits include improving social conditions (e.g., promoting green jobs, stimulating technological innovation, maintaining public health, reducing pollution)104–109 and promoting a smarter and more benevolent society110.

A 24-nation dataset from all inhabited continents confirmed that perceptions of these co-benefits are strong predictors of willingness to act pro-environmentally, and that the relationships are similarly strong regardless of whether participants believed climate change was an important issue102. Compared to traditional evidence-based messages, co-benefit frames tend to be at least as effective – and often more effective - in shifting pro-environmental intentions among self-reported sceptics110,111.

Leveraging climate-friendly actors within the conservative movement

The above strategies focus on optimising the content of climate messages. However, research on communication in intergroup contexts suggest that the messenger is often more important than nuances of the message112. Specifically, people are influenced by ingroup members more so than by outsiders who deliver the same message113. This is largely because people work from the assumption that insiders have their best interests at heart, whereas outsiders do not114.

An implication of this for the current analysis is that sceptics will be more influenced by messengers that share salient identities with them: rural people will be more influenced by rural messengers, conservatives will be more influenced by conservatives, and so forth. This is a challenging message for many climate activists because it underscores how their identification as “green” or “left” can be enough to render their voices impotent when it comes to influencing sceptics. It is also threatening because it emphasises how little evidence, sophisticated argument and impassioned advocacy can matter if one finds oneself on the other side of a polarised intergroup debate114.

The optimistic upside of this equation, however, is that there are non-traditional climate activists – such as the conservative-leaning, U.S.-based Climate Leadership Council – for whom real influence among conservatives is within reach. In a field study, Goldberg and colleagues115 tested the effectiveness of a one-month advertising campaign about climate change to potential voters in the U.S. states of Missouri and Georgia. The videos were crafted to appeal to Republicans, drawing on spokespeople with strong conservative credentials who referred to action on climate change as consistent with their conservative values. The campaign increased Republicans’ understanding of the existence and causes of climate change by several percentage points, providing evidence that the strategy is effective in the field as well as in the laboratory.

Leveraging climate-friendly actors within the conservative movement not only has the power to influence traditionally hard-to-reach populations, but it also has the potential to reconfigure the intergroup dynamic that has done so much damage to our ability to respond to climate change in the first place. Survey experiments in Australia revealed that when partisans learn that opposing leaders converged on a common policy proposal, it had a harmonising effect on respondents’ climate-related attitudes, leading to greater consensus and less polarisation (i.e., people took their “elite cues”116). Extracting climate science from the culture wars would be game-changing in terms of our ability to unite in the face of the climate crisis117.

Establishing norms

The term “norms” refers to two related perceptions: the perception that society (or important others) want you to behave in a certain way and the perception that the population (or important others) actually behave in a certain way. Both sets of norms – the prescriptive and descriptive – are consistently associated with behaviour, particularly when they align118. This is partly because norms increase conformity pressures around a behaviour: people fear judgement or negative attention for behaving in a non-normative way. Relatedly, norms signal whether a behaviour is the correct course of action; a form of social proof (the “consensus implies correctness” heuristic119). Once established, norms constrain behaviour in such a subtle and automatic way that people often remain unaware of their influence120. For example, one field study showed that normative information influenced energy-efficient behaviours more so than appeals to values and to economic self-interest, even though participants themselves reported the normative appeal as being relatively ineffective121.

Examined in a diverse range of contexts – both in the laboratory and in the field – norms have become a favoured tool for shaping public behaviour to solve collective challenges122. In relation to climate change, norms are a strong predictor of pro-environmental intentions123,124, and framing normative information in particular ways can influence people’s willingness to behave pro-environmentally121,125–131. Relevant to the current analysis, norms have power because they appeal to our social nature – the universal need to belong and be liked – and so do not rely on an internalised sense of concern for the environment.

Importantly, norm-based interventions can also be effective beyond the individual level. For example, elected officials tend to underestimate the climate beliefs of their constituents, so correcting those misperceptions (e.g., with survey data) can be a helpful intervention. Correcting inaccurate perceptions about what the public thinks has proved useful in the past in reducing distorted perceptions of polarisation132.

Consensus messaging

Using descriptive norms in communication relies on the existence of a popular consensus that can be leveraged. In cases where there is no community consensus, or the prevailing consensus runs counter to the intended message, it may instead be necessary to communicate the consensus in a specific reference group, such as scientists or experts. In the case of climate change, messaging would emphasise the fact that 97% of climate scientists agree on the fundamental principles of anthropogenic climate change133.

Some theorists have invested considerable hope in this 97% heuristic as a persuasion tool, describing it as a gateway belief: should communicators successfully communicate this fact, concern for the environment and urgency to enact change should follow. There is some support for this: in experiments, those who are exposed to the 97% heuristic are typically more likely than those in control conditions to accept the existence of human-caused climate change and, in turn, to support policy interventions28,134–137. Two recent meta-analyses have confirmed the power of highlighting consensus among (climate) experts138,139, and consensus information has been shown to be effective among sceptics28,140.

Embedding climate-friendly actions in social practice

Much behavioural science works on the implicit assumption that individual actions are a result of mindful consideration; a planned process during which costs and benefits are consciously weighed. However, many behaviours occur while we are in an automatic and unthinking state. In the pragmatic language of “nudging” and consumer psychology, this is referred to as habit141,142. In practice theory (which emerged from sociology and anthropology), a similar point is made about the routinised nature of action but with an ideological overlay. From this perspective, asking for individual change is unrealistic at best and sinister at worst; a process of “responsibilisation”, cultivated as a neoliberal strategy to deflect attention from the structural causes of climate change, which can ultimately cause resentment143,144.

Regardless, both perspectives converge to make a similar point: positive action is more likely if those actions are embedded in a network of social practices, so that it becomes part of the flow of one’s day and part of one’s social life. As a practical example of what this means, consider the example of recycling. When recycling is inconvenient, the decision to do so will be based on a conscious algorithm of costs and benefits, one that is partly captive to identity. But when recycling is made readily available and becomes routinised in daily life, it becomes a practice that sits outside of values, identities, and cost-benefit analyses.

Conclusion

The first scientific article to draw connections between fossil fuel combustion and climate change dates back more than 120 years145 and it has been over 30 years since George Bush Snr. said: “Those who think we are powerless to do anything about the greenhouse effect forget about the 'White House effect'; as President, I intend to do something about it.”146 However, neither scientific knowledge nor political rhetoric has thus far resulted in global commitments that are sufficient to address the climate crisis.

We have reviewed some of the reasons for this gridlock. The politically motivated operations to undermine or delay climate mitigation cannot be undone by better communication tools alone. However, we have shown that a suite of ethical communication techniques is at our disposal to accelerate any meaningful climate mitigation that might arise from political solutions to the political problem of climate scepticism.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dieter Plehwe for helpful discussions and pointers to relevant literature.

Acknowledgement of Funding

MH acknowledges funding support from the Australian Research Council Discovery scheme (DP220101566).

SL acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant 101020961 PRODEMINFO) and the Humboldt Foundation in Germany through a research award.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Washington H, Cook J. Climate change denial: Heads in the sand. Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitmarsh L. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environmental Change. 2011;21:690–700. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capstick SB, Pidgeon NF. What is climate change scepticism? Examination of the concept using a mixed methods study of the UK public. Global Environmental Change. 2014;24:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornsey MJ, Chapman CM, Humphrey JE. Climate skepticism decreases when the planet gets hotter and conservative support wanes. Global Environmental Change. 2022;74:102492 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton LC, Hartter J, Lemcke-Stampone M, Moore DW, Safford TG. Tracking public beliefs about anthropogenic climate change. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0138208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan PJ, Mullin M. Climate change: US public opinion. Annual Review of Political Science. 2017;20:209–227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polino C. Cambio climático y opinión pública en América Latina. Buenos Aires: 2019. pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecker UKH, et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology. 2022;1:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewandowsky S. Climate change, disinformation, and how to combat it. Annual Review of Public Health. 2021;42:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornsey MJ, Harris EA, Bain PG, Fielding KS. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change. 2016;6:622–626. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauchat G. Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review. 2012;77:167–187. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond E, Bernauer T, Mayer F. Does providing scientific information affect climate change and GMO policy preferences of the mass public? Insights from survey experiments in Germany and the United States. Environmental Politics. 2020;29:1199–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart PS, Nisbet EC. Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research. 2012;39:701–723. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewandowsky S, Mann ME, Brown NJL, Friedman H. Science and the public: Debate, denial, and skepticism. Journal of Social and Political Psychology. 2016;4:537–553. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellerton P. Climate sceptic or climate denier? It's not that simple and here's why. 2019. < https://theconversation.com/climate-sceptic-or-climate-denier-its-not-that-simple-and-heres-why-117913>.

- 16.Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K. Motivated rejection of science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2016;25:217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunda Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornsey MJ, Fielding KS. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: Understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. American Psychologist. 2017;72:459–473. doi: 10.1037/a0040437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell TH, Kay AC. Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014;107:809–824. doi: 10.1037/a0037963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornsey MJ, Fielding KS. Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2020;14:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassarjian HH, Cohen JB. Cognitive dissonance and consumer behavior. California Management Review. 1965;8:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mata A, Sherman SJ, Ferreira MB, Mendonça C. Strategic numeracy: Self-serving reasoning about health statistics. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2015;37:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunda Z. Motivated inference - self-serving generation and evaluation of causal theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:636–647. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K. Worldview-motivated rejection of science and the norms of science. Cognition. 2021;215:104820. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahan DM. Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment & Decision Making. 2013;8:407–424. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heath Y, Gifford R. Free-market ideology and environmental degradation: The case of belief in global climate change. Environment and Behavior. 2006;38:48–71. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewandowsky S, Gignac GE, Vaughan S. The pivotal role of perceived scientific consensus in acceptance of science. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fielding KS, Hornsey MJ. A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen GL. Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:808–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner JC. Social influence. Thomson Brooks / Cole Publishing Co; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornsey MJ. Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:204–222. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oreskes N, Conway EM. Merchants of doubt. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrell J. Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:92–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509433112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan R, Uchimiya E. Where the 2016 Republican candidates stand on climate change. 2015. < www.cbsnews.com/news/where-the-2016-republican-candidates-stand-on-climate-change>.

- 36.Matthews D. Donald Trump has tweeted climate change skepticism 115 times Here’s all of it. 2017. < https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/6/1/15726472/trump-tweets-global-warming-paris-climate-agreement>.

- 37.Escobar H. Brazil’s new President has scientists worried Here’s why. 2019. < https://www.science.org/content/article/brazil-s-new-president-has-scientists-worried-here-s-why>.

- 38.Fielding KS, Head BW, Laffan W, Western M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Australian politicians’ beliefs about climate change: political partisanship and political ideology. Environmental Politics. 2012;21:712–733. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunlap RE. Clarifying anti-reflexivity: conservative opposition to impact science and scientific evidence. Environmental Research Letters. 2014;9:021001 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunlap RE, McCright AM, Yarosh JH. The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the U.S. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 2016;58:4–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCright AM, Dunlap RE. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change. 2011;21:1163–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCright AM, Dunlap RE. Anti-reflexivity: The American conservative movement’s success in undermining climate science and policy. Theory Culture & Society. 2010;27:100–133. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brulle RJ, Carmichael J, Jenkins JC. Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002-2010. Climatic Change. 2012;114:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmichael JT, Brulle RJ. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: An integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001-2013. Environmental Politics. 2017;26:232–252. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mildenberger M, Leiserowitz A. Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy-environment tradeoff? Environmental Politics. 2017;26:801–824. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gustafson A, et al. The development of partisan polarization over the Green New Deal. Nature Climate Change. 2019;9:940–944. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kahan DM, et al. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:732–735. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drummond C, Fischhoff B. Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114:9587–9592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704882114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamilton LC. Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change. 2011;104:231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ballew MT, Pearson AR, Goldberg MH, Rosenthal SA, Leiserowitz A. Does socioeconomic status moderate the political divide on climate change? The roles of education, income, and individualism. Global Environmental Change. 2020;60:102024 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Czarnek G, Kossowska M, Szwed P. Right-wing ideology reduces the effects of education on climate change beliefs in more developed countries. Nature Climate Change. 2021;11:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tesler M. Elite domination of public doubts about climate change (not evolution) Political Communication. 2018;35:306–326. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornsey MJ. The role of worldviews in shaping how people appraise climate change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2021;42:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCright AM, Dunlap RE. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001-2010. The Sociological Quarterly. 2011;52:155–194. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones JM. Democratic, Republican confidence in science diverges. 2021. < https://news.gallup.com/poll/352397/democratic-republican-confidence-science-diverges.aspx>.

- 56.Brulle RJ, Hall G, Loy L, Schell-Smith K. Obstructing action: Foundation funding and US climate change counter-movement organizations. Climatic Change. 2021;166:17. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunlap RE, Jacques PJ. Climate change denial books and conservative think tanks: Exploring the connection. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013;57:1–33. doi: 10.1177/0002764213477096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacques PJ, Dunlap RE, Freeman M. The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environmental Politics. 2008;17:349–385. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brulle RJ. Institutionalizing delay: Foundation funding and the creation of U.S. climate change counter-movement organizations. Climatic Change. 2014;122:681–694. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Supran G, Oreskes N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977-2014) Environmental Research Letters. 2017;12:084019 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruser A. In: Civil Society: Concepts, Challenges, Contexts. Hoelscher M, List R, Ruser A, Toepler S, editors. Springer; 2022. pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Plehwe D. Reluctant transformers or reconsidering opposition to climate change mitigation? German think tanks between environmentalism and neoliberalism. Globalizations. 2022 doi: 10.1080/14747731.2022.2038358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Almiron N, Boykoff M, Narberhaus M, Heras F. Dominant counter-frames in influential climate contrarian European think tanks. Climatic Change. 2020;162:2003–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plehwe D. Whither Energiewende? Strategies to manufacture uncertainty and unknowing to redirect Germany’s Renewable Energy Law. International Journal of Public Policy. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oreskes N. Systematicity is necessary but not sufficient: On the problem of facsimile science. Synthese. 2019;196:881–905. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moreno JA, Kinn M, Narberhaus M. A Stronghold of climate change denialism in Germany: Case study of the output and press representation of the think tank EIKE. International Journal of Communication. 2022;16:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michaels L, Ainger K. In: Climate Change Denial and Public Relations: Strategic Communication and Interest Groups in Climate Inaction. Xifra Jordi, Almiron Núria., editors. Routledge; 2019. pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Best J. Varieties of ignorance in neoliberal policy: or the possibilities and perils of wishful economic thinking. Review of International Political Economy. 2022;29:1159–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll. 2021. < https://wrp.lrfoundation.org.uk/>.

- 70.Björnberg KE, Karlsson M, Gilek M, Hansson SO. Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990-2015. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2017;167:229–241. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simpson NP, et al. Climate change literacy in Africa. Nature Climate Change. 2021;11:937–944. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guha RA, Alier JM. Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South. Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim SY, Wolinsky-Nahmias Y. Cross-national public opinion on climate change: The effects of affluence and vulnerability. Global Environmental Politics. 2014;14:79–106. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee TM, Markowitz EM, Howe PD, Ko C-Y, Leiserowitz AA. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change. 2015;5:1014–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tranter BK, Booth KI. Scepticism in a changing climate: A cross-national study. Global Environmental Change. 2015;33:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Painter J, Ashe T. Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007-10. Environmental Research Letters. 2012;7:044005 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmidt A, Ivanova A, Schäfer MS. Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Global Environmental Change. 2013;23:1233–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hornsey MJ, Harris EA, Fielding KS. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nature Climate Change. 2018;8:614–620. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poortinga W, Whitmarsh L, Steg L, Böhm G, Fisher S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Global Environmental Change. 2019;55:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCright AM, Dunlap RE, Marquart-Pyatt ST. Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environmental Politics. 2016;25:338–358. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith EK, Mayer A. Anomalous Anglophones? Contours of free market ideology, political polarization, and climate change attitudes in English-speaking countries, Western European and post-Communist states. Climatic Change. 2019;152:17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Birch S. Political polarization and environmental attitudes: A cross-national analysis. Environmental Politics. 2020;29:697–718. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vihma A, Reischl G, Nonbo Andersen A. A climate backlash: Comparing populist parties’ climate policies in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. The Journal of Environment & Development. 2021;30:219–239. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kulin J, Johansson Sevä I, Dunlap RE. Nationalist ideology, rightwing populism, and public views about climate change in Europe. Environmental Politics. 2021;30:1111–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huber RA. The role of populist attitudes in explaining climate change skepticism and support for environmental protection. Environmental Politics. 2020;29:959–982. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huber RA, Greussing E, Eberl J-M. From populism to climate scepticism: The role of institutional trust and attitudes towards science. Environmental Politics. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1978200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Higham JSC. Global trends in climate change litigation: 2021 snapshot. The Centre for Climate Change Econcomics and Policy; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clark CE, Crawford EP. Influencing climate change policy: The effect of shareholder pressure and firm environmental performance. Business & Society. 2012;51:148–175. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Flammer C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. The Academy of Management Journal. 2013;56:758–781. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Motta M. The enduring effect of scientific interest on trust in climate scientists in the United States. Nature Climate Change. 2018;8:485–488. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baker S, Martinson DL. The TARES Test: Five principles for ethical persuasion. Journal of Mass Media Ethics. 2001;16:148–175. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benestad R, et al. Learning from mistakes in climate research. Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 2016;126:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lewandowsky S, Ballard T, Oberauer K, Benestad R. A blind expert test of contrarian claims about climate data. Global Environmental Change. 2016;39:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feinberg M, Willer R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science. 2013;24:56–62. doi: 10.1177/0956797612449177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wolsko C. Expanding the range of environmental values: Political orientation, moral foundations, and the common ingroup. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2017;51:284–294. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wolsko C, Ariceaga H, Seiden J. Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2016;65:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feygina I, Jost JT, Goldsmith RE. System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:326–338. doi: 10.1177/0146167209351435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kidwell B, Farmer A, Hardesty DM. Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research. 2013;40:350–367. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Whitmarsh L, Corner A. Tools for a new climate conversation: A mixed-methods study of language for public engagement across the political spectrum. Global Environmental Change. 2017;42:122–135. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feldman L, Hart PS. Climate change as a polarizing cue: Framing effects on public support for low-carbon energy policies. Global Environmental Change. 2018;51:54–66. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dixon G, Hmielowski J, Ma Y. Improving climate change acceptance among U.S. conservatives through value-based message targeting. Science Communication. 2017;39:520–534. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bain PG, et al. Co-benefits of addressing climate change can motivate action around the world. Nature Climate Change. 2016;6:154–157. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moser SC, Dilling L. Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nemet GF, Holloway T, Meier P. Implications of incorporating air-quality co-benefits into climate change policymaking. Environmental Research Letters. 2010;5:014007 [Google Scholar]

- 105.West JJ, et al. Co-benefits of global greenhouse gas mitigation for future air quality and human health. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:885–889. doi: 10.1038/NCLIMATE2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thurston GD. Health co-benefits. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:863–864. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maibach EW, Nisbet M, Baldwin P, Akerlof K, Diao G. Reframing climate change as a public health issue: An exploratory study of public reactions. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Myers TA, Nisbet MC, Maibach EW, Leiserowitz AA. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Climatic Change. 2012;113:1105–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Petrovic N, Madrigano J, Zaval L. Motivating mitigation: When health matters more than climate change. Climatic Change. 2014;126:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bain PG, Hornsey MJ, Bongiorno R, Jeffries C. Promoting pro-environmental action in climate change deniers. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:600–603. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bernauer T, McGrath LF. Simple reframing unlikely to boost public support for climate policy. Nature Climate Change. 2016;6:680–683. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fielding KS, Hornsey MJ, Thai HA, Toh LL. Using ingroup messengers and ingroup values to promote climate change policy. Climatic Change. 2020;158:181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hornsey MJ, Esposo S. Resistance to group criticism and recommendations for change: Lessons from the intergroup sensitivity effect. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Esposo SR, Hornsey MJ, Spoor JR. Shooting the messenger: Outsiders critical of your group are rejected regardless of argument quality. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2013;52:386–395. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goldberg MH, Gustafson A, Rosenthal SA, Leiserowitz A. Shifting Republican views on climate change through targeted advertising. Nature Climate Change. 2021;11:573–577. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kousser T, Tranter B. The influence of political leaders on climate change attitudes. Global Environmental Change. 2018;50:100–109. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hornsey MJ, Chapman CM, Fielding KS, Louis WR, Pearson S. A political experiment may have extracted Australia from the climate wars. Nature Climate Change. 2022;12:695–696. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Smith JR, et al. Congruent or conflicted? The impact of injunctive and descriptive norms on environmental intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2012;32:353–361. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Aarts H, Dijksterhuis A. The silence of the library: Environment, situational norm, and social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nolan JM, Schultz PW, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:913–923. doi: 10.1177/0146167208316691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nyborg K, et al. Social norms as solutions. Science. 2016;354:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fielding KS, McDonald R, Louis WR. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2008;28:318–326. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rees JH, Bamberg S. Climate protection needs societal change: Determinants of intention to participate in collective climate action. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2014;44:466–473. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB, Griskevicius V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35:472–482. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kormos C, Gifford R, Brown E. The influence of descriptive social norm information on sustainable transportation behavior: A field experiment. Environment and Behavior. 2014;47:479–501. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schultz PW. Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A field experiment on curbside recycling. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;21:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Allcott H. Social norms and energy conservation. Journal of Public Economics. 2011;95:1082–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cialdini RB. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions In Psychological Science. 2003;12:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schubert C. Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical? Ecological Economics. 2017;132:329–342. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ruggeri K, et al. The general fault in our fault lines. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5:1369–1380. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cook J, et al. Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters. 2016;11:048002 [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cook J, Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH. Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0175799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Goldberg MH, et al. The experience of consensus: Video as an effective medium to communicate scientific agreement on climate change. Science Communication. 2019;41:659–673. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Imundo MN, Rapp DN. When fairness is flawed: Effects of false balance reporting and weight-of-evidence statements on beliefs and perceptions of climate change. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 2021;11:258–271. [Google Scholar]

- 137.van der Linden S, Leiserowitz A, Maibach E. Scientific agreement can neutralize politicization of facts. Nature Human Behavior. 2018;2:2–3. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rode JB, et al. Influencing climate change attitudes in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2021:101623 [Google Scholar]

- 139.van Stekelenburg A, Schaap G, Veling H, Van’t Riet J, Buijzen M. Scientific consensus communication about contested science: A preregistered meta-analysis. Psychological Science. 2022 doi: 10.1177/09567976221083219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.van der Linden S, Leiserowitz A, Maibach E. Perceptions of scientific consensus predict later beliefs about the reality of climate change using cross-lagged panel analysis: A response to Kerr and Wilson 2018. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2018;60:110–111. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Harvey AG, Armstrong CC, Callaway CA, Gumport NB, Gasperetti CE. COVID-19 prevention via the science of habit formation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2021;30:174–180. [Google Scholar]

- 142.White K, Habib R, Hardisty DJ. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing. 2019;83:22–49. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gonzalez-Arcos C, Joubert AM, Scaraboto D, Guesalaga R, Sandberg J. “How do i carry all this now?” Understanding consumer resistance to sustainability interventions. Journal of Marketing. 2021;85:44–61. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Eckhardt GM, Dobscha S. The consumer experience of responsibilization: The case of Panera Cares. Journal of Business Ethics. 2019;159:651–663. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Arrhenius S. XXXI. On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 1896;41:237–276. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Hudson M. George Bush Sr could have got in on the groundfloor of climate action – history would have thanked him. 2018. < https://theconversation.com/george-bush-sr-could-have-got-in-on-the-ground-floor-of-climate-action-history-would-have-thanked-him-108050>.