Summary

The skin epidermis is constantly renewed throughout life1,2. Disruption of the balance between renewal and differentiation can lead to uncontrolled growth and tumour initiation3. However, the ways in which oncogenic mutations impact the balance between renewal and differentiation and lead to clonal expansion, cell competition, tissue colonization and tumour development is currently unknown. Here, using multidisciplinary approaches combining in vivo clonal analysis using intra-vital microscopy, single cell analysis, and functional analysis, we defined, at a single cell resolution in living animals, how SmoM2 mutation that induces basal cell carcinoma (BCC) development, the most frequent cancer in human4, affects clonal competition and tumour initiation in real time. We found that SmoM2 expression in the ear epidermis induced clonal expansion accompanied with tumour initiation and invasion. In contrast, SmoM2 expression in the back skin epidermis led to clonal expansion that induced lateral cell competition without inducing dermal invasion and tumour formation. Single cell analysis showed that oncogene expression is associated with a cellular reprogramming of adult interfollicular cells into embryonic hair follicle progenitor (EHFP) state in the ear but not in the back skin. Comparison between ear and back skin revealed a very different composition of the dermis with increased stiffness and a denser Collagen 1 network in the back skin. Decreasing Collagen I expression in the back skin by collagenase, during natural ageing or following chronic UV exposure overcome the natural resistance of back skin basal cells to undergo EHFP reprogramming and tumour initiation following SmoM2 expression. Altogether our study demonstrates that ECM composition regulates the regional competence to undergo tumour initiation and invasion.

Introduction

The skin epidermis is an essential barrier that protects animals against the external environment. The interfollicular epidermis (IFE) is a stratified epithelium that contains a proliferative basal layer and several differentiated suprabasal layers1,2. During homeostasis, the loss of differentiated cells on the skin surface is compensated by the proliferation to maintain constant number of cells3. The generation of new cells is ensured by stem cells (SC) and progenitors that divide asymmetrically at the population level3. Recent lineage tracing and clonal analysis studies revealed that the balance between renewal and differentiation is achieved by the relative proportion of asymmetric renewal, symmetric renewal, and symmetric differentiation in SCs and progenitor cells3. During homeostasis, symmetric renewal and symmetric differentiation are perfectly balanced. The deregulation of this exquisite balance between proliferation and differentiation can have disastrous outcomes such as cancer initiation3.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequent human cancer with more than 5 million of new cases diagnosed each year worldwide4. BCCs arise from the activation of the Hedgehog pathway by either loss-of-function mutations in Patched1 (Ptch1) gene or gain-of-function mutations in Smoothened (Smo)4. Mouse models of BCC using Ptch1 deletion or expression of oncogenic mutant of Smo (SmoM2) lead to the formation of tumours that resemble superficial human BCC5. SmoM2 expression in the skin epidermis leads to BCC development in the tail and ear epidermis6,7.

Cell competition is a biological process that leads to the elimination of one population of loser cells by a population of winner cells 8–10. It has been proposed that oncogene expressing cells can outcompete their WT neighbours allowing tumour formation, similarly to what has been described as super competition in fly imaginal discs expressing different doses of dMyc11,12. However, the exact mechanisms by which oncogene-expressing cells induce cell competition with their WT neighbours and allow tumour initiation remain poorly understood. Recent sequencing studies have shown that oncogenic mutations occur at a surprisingly high frequency in tissues that appear histologically normal13. The existence of oncogenic mutations in histologically normal tissues suggests that mutations alone are not sufficient to drive neoplastic growth and that other unknown mechanisms promote or restrain oncogene-expressing cells to progress into malignant invasive tumours. The question of whether alloncogene-targeted clones present the same ability to outcompete their WT neighbours remains poorly understood.

Using multidisciplinary approaches which combine lineage tracing, clonal analysis in living animals, single cell sequencing, quantitative proteomics, and functional experiments, we have investigated the mode of cell competition and the ability of oncogene-expressing cells to develop invasive BCC in different skin regions.

Intravital imaging of SmoM2 clones

It has been reported that SmoM2 expression in the back skin does not lead to BCC formation6,7. The reason for the inability of back skin epidermis to be competent for BCC initiation is currently unknown. Do stem cells in the back skin fail to undergo symmetric division and clonal expansion following oncogenic SmoM2 expression leading to their inability to outcompete their WT neighbours? To investigate the impact of the oncogenic mutation on cell competition, clonal expansion and the competence to induce tumour initiation in different body locations, we have developed a mouse model allowing us to monitor the fate of single oncogene-targeted clones over time in living mice, using intravital multiphoton confocal microscopy. To this end, we generated a mouse model that allows the expression of SmoM2 oncogene together with the expression of a fluorescent reporter gene that can be monitored by intravital microscopy. In the absence of oncogene expression, all epidermal cells express the td-tomato fluorescent protein at the membrane in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG mice. Upon TAM administration, CREER-mediated recombination induces the expression of SmoM2 and a switch of the reporter gene from the red fluorescent to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Fig. 1a-f). In order to track the same cells over time, we used a tattoo to identify the precise skin regions and defined the cell coordinate using the stable pattern of hair follicle arrangement found in the epidermis, which allowed us to monitor the same clones in anesthetized mice (Extended data Fig. 1a-e).

Fig. 1 |. Intravital imaging of clonal expansion and BCC formation in the ear and back skin.

a-d. Intravital imaging of the same SmoM2 expressing clone in the ear (a) and back skin (d) at different time points after TAM administration to K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG mice. Red: WT cells; Green: SmoM2-cells; Grey: second harmonic generation signal. b, e. Orthogonal views of the same clone presented in figures 1a, d and showing the invasion of the mutated clones over time into the dermis in the ear and the lateral expansion in the back skin. Dashed line: basement membrane. c, f. Immunofluorescence (Left) and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (Right) stainings of SmoM2-mutated cells in the ear (c) and back skin (f) epidermis of K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG mice at 12 and 24 weeks post Tamoxifen induction. For H&E, dashed line: epidermal-dermal interface. g. Quantification of the vertical distance between WT and SmoM2 cells showing the depth of invasion of SmoM2-mutated clones at 2 weeks, 4 and 6 weeks after tamoxifen administration. Measurements of the vertical invasion were performed from 3 mice for the ear and 4 mice for the back skin. h. Quantification of the lateral expansion of SmoM2-mutated clones in the ear and back skin epidermis at 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 6 after tamoxifen administration (n= 3 mice for the ear and 4 mice for the back skin). i. Quantification of the number of cells per WT clones after 6 weeks after tamoxifen and SmoM2-expressing clones in the ear and back skin epidermis (total number of cells per clone) at 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 6 weeks after tamoxifen administration. Measurements of the clones were performed on the same image areas from 2 mice (SmoM2) and 4 mice (WT). a-f. Scale bar = 20 μm. g, h, i. The number of clones quantified are indicated in parentheses. Mean +- SEM. Kruskal-Wallis test.

We monitored the fate of SmoM2 expressing cells over time in the ear, a skin location associated with BCC formation. Compared to WT cells, which divide asymmetrically at the population level14–16, SmoM2 expression promoted self-renewing division leading to an increasing pool of basal cells that first expand laterally together with a block in suprabasal differentiation14. About three weeks following SmoM2 expression, the shape of the oncogeneexpressing cells changed, and the clones adopted a placode-like morphology, that progressively grew downwards and invaded the dermis (Fig. 1a, b). After six weeks, SmoM2 expressing clones continued their vertical expansion and invaded the dermis in a branch-like structure, reminiscent of the growth of superficial BCC found in the mouse tail epidermis and in human skin (Fig. 1c)5,6. Consistent with this invasive phenotype and a previous study17, immunostaining components of the basal lamina (α6-integrin and Laminin-332) and electron microscopy analysis showed that there is a discontinuity of the basal lamina at the leading edge of invading SmoM2 clones in the ear (Extended data Fig. 2a-e). The quantification of the lateral size, depth of invasion and number of cells per clone showed that after the initial phase of lateral spreading (3 weeks), SmoM2 clones minimally expanded laterally and continued to grow vertically by invading the dermis (Fig. 1g-i and Extended data Fig. 2f-i). To further substantiate that SmoM2 expression increases self-renewing division, we performed short term lineage tracing using BrdU pulse chase and assessed the fate of BrdU doublet, corresponding to the two daughter cells after division. In contrast with WT epidermis that divided mostly asymmetrically, SmoM2 clones underwent symmetric renewing divisions (Extended data Fig. 2j-l), in good accordance with the clonal analysis made by lineage tracing. These data show that clonal expansion in the ear epidermis following oncogenic SmoM2 expression switch rapidly from lateral expansion to vertical invasion.

To assess why oncogene expression in the back skin is not associated with BCC formation, we monitored the fate of oncogene-targeted cells overtime in living animals using intravital microscopy. Interestingly, initially SmoM2 expressing cells in the back skin were expanding laterally at the same rate as the epidermal cells of the ear epidermis. However, in sharp contrast to ear epidermis, oncogene expressing cells in the back skin did not undergo a cell shape transition and initiate downgrowth into the dermis, but instead continued to expand laterally (Fig. 1d, e, i). Even after 6 months following SmoM2 expression, oncogene targeted cells continued to differentiate into suprabasal cells and presented a hyperplasia resulting into a “touch dome”-like morphology (Fig. 1f). Quantification of lateral spreading, invasion and clone size demonstrated that in contrast to WT cells targeted with a fluorescent protein, oncogene-targeted cells in the back skin epidermis readily expanded following oncogene expression, leading to a similar clonal expansion and increased in self-renewing division compared to the ear epidermis, but the clones expanded laterally and failed to invade the dermis vertically (Fig. 1g-i). Similarly to the ear epidermis, short term BrdU pulse chase experiments confirmed the switch from asymmetric division to symmetric renewal upon SmoM2 expression (Extended data Fig. 2j-l). These data demonstrate that the inability of the back skin epidermis to undergo neoplastic transformation and inability to invade the dermis upon SmoM2 expression is not related to the inability of the oncogene targeted stem cells to switch from an asymmetrical to symmetrical mode of division but is rather the consequence of their inability to switch from lateral expansion to vertical invasion.

Cell mechanics surrounding SmoM2 clones

As mutated clones expand over time, they must compete for the space with their WT neighbouring cells. Differences in cell mechanics between WT and oncogene targeted cells can constrain the growth and expansion of mutated clones18–20. To assess the possible differences in mechanical properties of WT cells and mutant cells, we first quantified the shape of the cells at the interface of the mutated clone and WT cells over time. In the ear epidermis, WT cells at the border of the clones became deformed as shown by the increase in the aspect ratio of the cells (ratio of cell width to cell height) as soon as the mutated cloned adopted a placode-like morphology and before the mutated clone became invasive. The aspect ratio of the WT border cells in the ear further increased as the clones grow and become invasive. In contrast, in the back skin, no change in cell shape or aspect ratio was found in the WT cells contacting the mutated clones (Fig. 2a, b). These data suggest that in the ear epidermis, oncogene-targeted clones and WT border cells generate an interface displaying features of high interfacial tension that may restrain its lateral expansion and thus participate in promoting vertical growth. In the back skin, the WT cells at the border of the SmoM2-expressing clone were not elongated (Fig. 2b), indicating the absence of a specific mechanical interface in this tissue compartment.

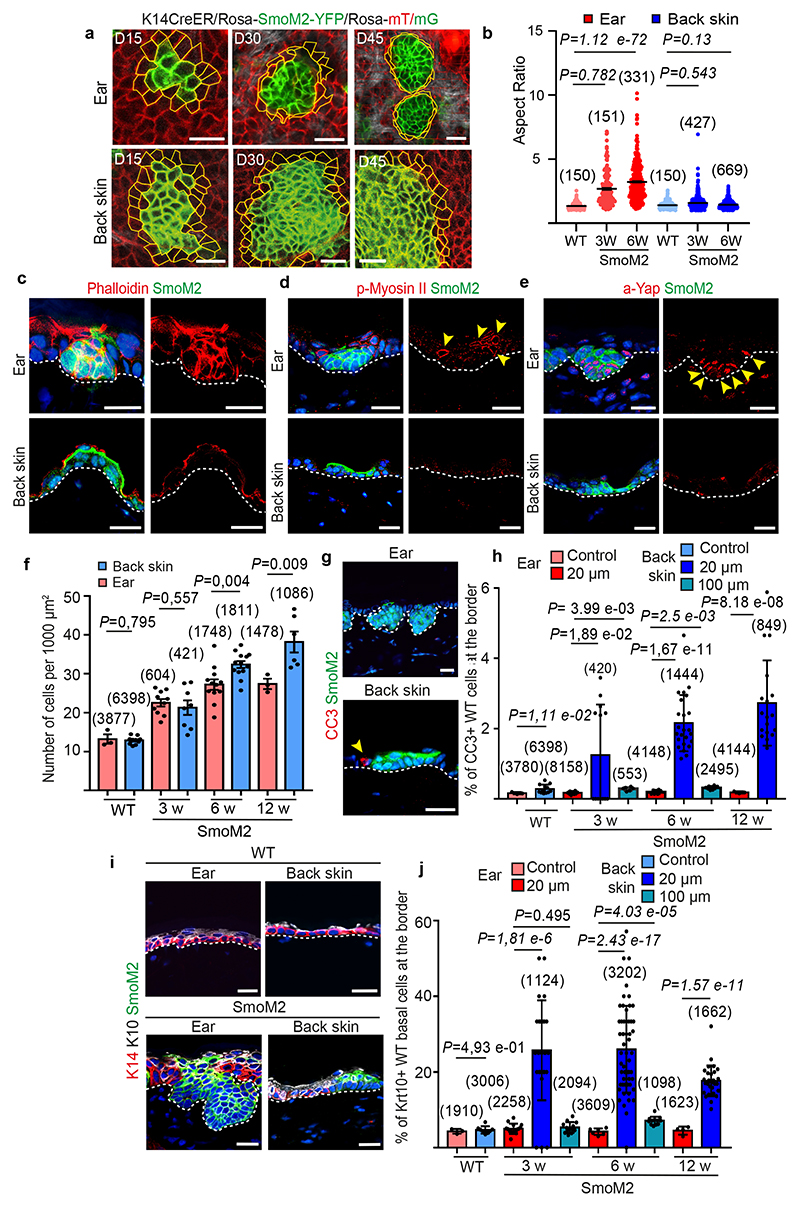

Fig. 2 |. Difference in cell mechanics and competition in the ear and back skin epidermis following SmoM2 expression.

a. Intravital imaging showing the shape of WT cells at border of SmoM2 clone in the ear and back skin epidermis. In the ear, WT cells became elongated whereas they remain cuboidal in the back skin. b. Quantification of aspect ratio of WT cells in control (n=3) and WT cells around SmoM2-clones 3 weeks (n=4) and 6 weeks (n=3 for the ear and n=2 for the back skin) after oncogenic expression. Mean ± SEM. Two-tailed z-test. c-e. Immunostainings for actin (c), phospho-myosin II (d) and active YAP in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 3 weeks after SmoM2 activation. f. Quantification of cell density in control (n=3) and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 3 weeks (n=3), 6 weeks (n=5), and 12 weeks (n=3) after SmoM2 expression. Mean +- SEM. Paired t-test, with two-sample unequal variance. g. Immunostainings for cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice 6 weeks after SmoM2 activation in the ear and back skin. h Quantification of apoptotic cells in control and WT cells at the border of SmoM2 clones within 20 and 100 μm in K 14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2- YFP at 3 (n=3), 6 (n=4) and 12 weeks (n=3) after SmoM2 expression. i. Immunostainings for Keratin 14 and Keratin 10 in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 6 weeks after SmoM2 activation in the ear (top) and back skin (bottom). j. Quantification of WT Krt10 positive basal cells in control (n=3) and within 20 and 100 μm from SmoM2 clones in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 3 (n=3), 6 (n=3 for the ear n=5 for the back skin at 20 μm and n=4 at 100 μm) and 12 weeks (n=3) after SmoM2 activation. h, j. Mean +- SEM. Kruskal-Wallis test. a, c-e, g, i. Scale bar, 20 μm. The number of clones quantified are indicated in parentheses. n = mice.

To further define the role and source of the mechanical force exerted by the mutated clones on WT cells, we assessed the remodelling of the acto-myosin cytoskeleton during the early step of tumor initiation. Phalloidin staining showed a major increase in the level of F-actin in oncogene targeted cells in the ear as soon as SmoM2 cells adopt a placode like shape. In contrast, no change in phalloidin staining was found in oncogene targeted clones in the back skin epidermis (Fig. 2c and Extended data Fig. 3a-d). Immunostaining of phosphorylated myosin light chain-2 (pMLC2) revealed an increase in myosin activity in SmoM2 expressing cells and its WT neighbour at the border of oncogene mutated clones in the ear epidermis but not in the back skin (Extended data Fig. 3b). Quantification of YAP activity as a further indication of increased mechanical tension showed increased nuclear YAP at the leading edge of invading clones and in the WT neighbour at the border of clones, whereas only very occasional nuclear active YAP positive cells were found in the back skin SmoM2 expressing clones (Fig. 2c, e). Collectively these data indicate increased mechanical tension specifically at the clone boundary and enhanced cortical actin in the mutant cells in the ear, explaining their ability to laterally confine WT cells. These data are reminiscent of the role of compressive forces triggering early hair follicle downward migration during embryonic development21. In contrast, oncogene targeted cells in the back skin showed no evidence for mechanical force-mediated cell competition between WT and oncogene mutated cells at this body location.

Instead, in the back skin, the increase of cell proliferation of SmoM2 mutated cells at the border of the clones was associated with a decrease in cell size and increase in cell density within the mutated clone, accompanied by an increase in the aspect ratio of the SmoM2 expressing cells at the center of the clones (Fig. 2f and Extended data Fig. 4a-e), indicative of mechanical confinement inside the clone. To assess in real time the cellular rearrangement of SmoM2 mutated clones in the back skin during clonal expansion, we performed live imaging of SmoM2 mutated clones over time for 54 hours. We found that SmoM2 mutated clones progressively outcompete their WT neighbour through specific patterns of cellular rearrangements, including progressive displacement, encirclement, intercalation and extrusion of WT cells (Extended data Fig. 4f). This pattern of cell intercalation with no apparent sharp mechanical interface between WT and mutated clones suggest that SmoM2 mediated clonal expansion occurs through an active mechanism of cell competition independently of mechanical stress.

Cell competition induced by SmoM2

Several mechanisms of cell competition have been described including mechanical cell competition, induction of apoptosis or cell differentiation9–10,18,20,22. To assess the nature of the active mechanisms that induce cell competition in the back skin following SmoM2 expression, we first determined whether SmoM2 clones can induce cell death at the border of the clones. In the ear epidermis, despite the compression of WT cells, there was no increase in the proportion of cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) positive cells in WT basal cells at the border of the mutated clones and CC3 positive cells were mostly found at the centre of the mutated clones as previously described (Fig. 2g, and Extended data Fig. 4g-h and Fig. 5a)14. In contrast, there was a major substantial increase in the proportion of CC3 positive WT cells at the border of the SmoM2 clones in the back skin epidermis (Fig. 2g-h), demonstrating that SmoM2 expressing cells increase apoptosis of WT cells in this skin region.

To assess whether in addition to promoting cell death, oncogene expressing cells outcompete their WT neighbouring cells by inducing their terminal differentiation23, we quantified the expression of K10, a differentiation marker, in WT basal cells (K14+) at the border of SmoM2 clones. Whereas WT basal cells did not show increased differentiation in the ear epidermis, there was a major increase in the proportion of basal cells that expressed K10 at the border of SmoM2 clones in the back skin epidermis, showing that SmoM2 expressing cells induce the differentiation of their WT neighbours in the back skin (Fig. 2i-j).

Altogether these data demonstrate that SmoM2 expressing cells present different ability to compete with WT cells depending on their body locations, and the SmoM2 clones in the back skin are much more efficient to induce lateral cell competition as compared to the ear epidermis, providing a plausible mechanism by which SmoM2 expressing cells can expand horizontally in the back skin without necessarily being associated with tumour invasion.

EHFP reprograming induced by SmoM2

To uncover the molecular mechanisms by which SmoM2 expression in the ear leads to BCC initiation while the same oncogene in the back skin leads to lateral clonal expansion that fail to invade the dermis and tumour formation, we performed temporal analysis of single cell RNA-seq of WT and SmoM2 expressing basal cells of the back skin and ear epidermis using 10X chromium technology at 3 weeks following oncogene expression, when the first difference between back skin and ear epidermis begins to be visible and at 6 weeks when the dermal invasion is well established in the ear. Unsupervised clustering of WT ear and back skin epidermis showed similar clusters associated with the different cell states previously described24–27 (Extended data Fig. 6a-d). SmoM2-expressing basal cells showed the same clusters as well as the appearance of additional clusters corresponding to new cellular states expressing the molecular signature of embryonic hair follicle progenitor (EHFP) reprogramming with high expression of Lhx2 and Lgr5 (Fig. 3a, c, e). The reprogramming of adult IFE SC into EHFP-like cells has previously been shown to be important for SmoM2 induced BCC formation in the tail epidermis28,29. The EHFP signature is associated with a higher level of HH (eg: Ptch1) and Wnt signalling (eg: Wnt6, Fzd1, Lef1, Lgr5) as well as higher expression of key genes regulating ECM (extracellular matrix)/basal lamina (eg: Adamts1, Col14a1, Postn, Lama5), cell-cell adhesion (eg: Alcam, PCadh/Cdh3), cell survival and proliferation (eg: Nmyc), and cell migration (eg: Sox9) that are likely to participate in the dermal invasion (Extended data Fig. 7a-g). In contrast, SmoM2 expressing basal cells in the back skin showed very similar clusters as WT control, with a very small cluster (about 5%) expressing the EHFP signature and a higher proportion of cells associated with differentiation program (Expression of Krt1/Krt10) (Fig. 3b, d, f).

Fig. 3 |. Single-Cell RNA-seq reveals a block of oncogene induced EHFP reprograming in the back skin.

a-b. Single-cell RNA Sequencing of WT and SmoM2 expressing cells from the back skin and ear at 3 and 6 weeks following oncogene expression. UMAP of the unsupervised clustering analysis of scRNA-seq of basal keratinocytes isolated from WT, 3 weeks and 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression in the ear (a) and back skin (b). Pie chart representing the proportion of the different clusters in the different conditions. SC/CP : Stem cell/Committed progenitors, IFE Diff: interfollicular differentiated, INF Prog: Infundibulum progenitors, INF IST: Infundibulum isthmus, INF Diff: Infundibulum differentiated, EHFP, SG: sebaceous gland, HH Responsive : hedgehog responsive. “Committed cells” are basal cells committed to differentiation that express markers as (Krt14, Krt1 and Hes1) c-d. UMAP plots showing the enrichment score of the EHFP signature28,37 in each cellular cluster from control, 3 weeks, and 6 weeks SmoM2 expressing cells isolated from the ear (c) and back skin epidermis (d). Colour scaling represents the AUC (Area Under the Curve) score of EHFP enrichment as computed by AUCell. e-f. UMAP plots showing the normalized level of gene expression for the indicated EHFP genes (Lhx2/Lgr5) in ear (e) back skin (f). Gene expression is visualized as a colour gradient. g-h. Immunostaining of ear (g) and back skin (h) for EHFP marker P-cadh, Lhx2 and YFP in control and in K14-CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks following SmoM2 expression. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Immunostaining confirmed the expression of EHFP genes in the SmoM2-expressing clones in the ear as soon as the SmoM2 expressing begun to invade the dermis and the highest expression of these EHFP associated genes are found at the leading edge of the invasive tumors (Fig. 3g and Extended data Fig. 8a, c), further supporting that the contact with the dermis regulate EHFP reprograming. In the back skin, there was occasional small buds in contact with the dermis that expressed EHFP markers, but these cells never induced invasive tumors (Fig. 3h and Extended data Fig. 8b, d). Altogether, these data show that SmoM2 expression differentially impacts cellular reprogramming resulting in new cell states induced by the oncogene in distinct regions of the skin, which in turn controls tumor initiation.

ECM in BCC competent and resistant skin

To investigate whether a different composition of the dermis in the ear and the back skin affects the ability of oncogene targeted cells to form BCC, we performed an unbiased quantitative proteomic analysis before and 6 weeks after oncogene expression. This analysis revealed that only very few proteins were more highly expressed in the back skin as compared to the ear and included Col1a1 and Col1a2 (Fig. 4a). RNA-Fish on skin sections confirmed that many more fibroblasts in the back skin dermis expressed high level of Col1a1 and Col1a2 compared to the ear dermis (Fig. 4b). Multiphoton intravital imaging of the ear and back skin with second harmonic generation (SHG) revealed a very distinct collagen fibre organization in the different skin regions. Whereas in the back skin dermis presented abundant and thicker collagen fibres, the ear dermis presented a much sparser fibre collagen network. (Fig. 4c-f and Extended data Fig. 9a-b). Immunohistochemistry confirmed a much more abundant expression of Col1 in the dermis of the back skin as compared to the ear skin that persists after SmoM2 expression (Fig. 4g). Atomic Force Microscopy-based force indentation spectroscopy showed that the back skin dermis was substantially stiffer compared to the ear dermis in WT and SmoM2 conditions (Fig. 4h). Altogether these data show that there is a major difference in the composition and stiffness of the ECM between ear and the back skin, suggesting that the higher expression of Col1 in the back skin is associated with the inability of oncogene expressing cells to invade the dermis.

Fig. 4 |. The level of Coll expression correlates with the competence for BCC initiation.

a. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the dermis from the ear and the back skin. Volcano plot shows the statistically significantly (FDR<0.05- and 2-FC) upregulated proteins in the back skin or in the ear. b. RNA fish for Col1a1 and Col1a2 in the WT ear and back skin dermis. c. SHG using confocal imaging of ear and back skin dermis in control mice. d. Quantification of the SHG intensities of ear and back skin dermis in control mice. Measurements of SHG intensities were performed on 3 random areas using intravital microscopy (n=3). e. High magnification of the SHG using confocal imaging to assess collagen fibre bundle of the ear and back skin dermis in control mice. Yellow arrow: collagen fibre bundle size. Scale bar= 5 μm. f. Quantification of the collagen bundle size in the WT ear and back skin (n=3) using ImageJ. In parentheses, the number of bundles. g. Immunohistochemistry of Collagen 1 in control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 6 and 12 weeks after SmoM2 activation. h. Stiffness of the dermis measured by atomic force microscopy. Quantification of elastic modulus of the dermis in skin sections of the ear and back skin in control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2 mice 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression (n=2 mice per condition). The number of measurements are shown in parentheses. b, c, g, scale bar, 20 μm. d, f, h, Mean +- SEM. Kruskal-Wallis test. n = mice.

We have previously shown that the cellular composition of the dermis is remodelled in the tail skin epidermis following SmoM2 induced BCC formation28. Consistent with this notion, the proteomic analysis of the dermis following SmoM2 expression showed that the ear dermis expressed many proteins associated with inflammation (such as S100a9, MPO) (Extended data Fig. 10a-c). As shown by H&E staining, the cellular infiltration of the ear dermis dramatically increased following SmoM2 expression in the ear whereas it remained unchanged in the back skin (Extended data Fig. 8d). In the absence of oncogene expression, the relative abundance of immune and inflammatory cells (CD45+, CD68+, CD4+, CD8+) within the dermis was relatively similar in the ear and back skin epidermis (Extended data Fig. 10d-f).

Coll constrains BCC development

Collagen immunostaining showed that Col1 expression is higher the inner part of the ear as compared to the outer part of the ear and there was an inverse correlation between the level of Col1 expression and the ability of SmoM2 expressing cells to invade the dermis (Fig. 5a-d). The tail epidermis is organized into 2 distinct regions: the scale and the interscale regions. In the tail epidermis, BCCs develop only from the interscale region whereas the SmoM2 clones in the scale remain blocked at the pre-neoplastic stage14. Interestingly, there was an excellent correlation between the level of Col1 expression and the ability of SmoM2 to induce BCC formation, further suggesting that the level of Col1 dictates the competence of tumour initiation (Extended data Fig. 11a-d).

Fig. 5 |. High level of collagen 1 expression constrains BCC development.

a. Collagen 1 immunohistochemistry in the inner and outer ear. b. c. H&E staining (b), immunostainings of Lhx2 (c) in the ear of K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 6 weeks after SmoM2 activation. d. Quantification of tumour invasion measured by the vertical distance between WT cells and SmoM2-cells in the ear at 6 weeks after SmoM2 activation (n=4). e-f. Collagen 1 immunohistochemistry for collagen 1 and confocal analysis using SHG (e) and SHG quantification (f) of the back skin dermis before and 1 day after PBS or collagenase intradermal injection. Scale bar = 50μm for IHC and 20μm for SHG. Measurements of SHG intensities were performed on 3 random areas (n=4 mice). g. Quantification of the collagen bundle size in the WT back skin and back skin after collagenase injection (n=3 mice). h. Lhx2 immunostaining in the back skin after collagenase injection or PBS 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. i. Vertical distance between WT cells and smoM2 cells at 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression in the back skin following collagenase or PBS injection (n=6 mice) j-r. H&E staining (j, m, p), Collagen 1 immunohistochemistry (k, n, q) and Lhx2 and SmoM2 immunostaining (l, o, r) of the back skin in SmoM2 young (j, k, l), 1.5 years old (m, n, o), and UV-A treated mice (p, q, r). s. Vertical distance between WT cells and smoM2 cells 6 weeks after tamoxifen in the back skin of control mice (n=3), old mice (n=2) and mice treated with UV-A for 8 weeks (n=6). t. Immunostaining of SmoM2-clones of the back skin in young (left) and 1.5 year old SmoM2-mice (right) 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. yellow arrow= width. Red= height. u. Ratio between the height and width of SmoM2 clones in the back skin in SmoM2 young (n=3) and old mice (n=2) 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. Mean +- SEM. Two-tailed z-test. v. Quantification of WT basal cells expressing K10 at 20um around SmoM2 clones in the back skin in young (n=3) and 1.5 year-old mice (n=2) 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. Mean +- SEM. Paired t-test, with two-sample unequal variance (heteroscedastic). a, d, f, g, i, s. Mean +- SEM. Kruskal-Wallis test. a-c, h, j-r, t. Scale bar, 20μm. In parentheses, the number of clones (d, i, s, u, v) or measurements (g) quantified.

To assess whether the higher Col1 expression restricts invasion and tumour formation in the back skin upon SmoM2 expression, we enzymatically decreased the abundance of collagen and assessed its impact on tumour formation and invasion. To this end, we induced SmoM2 expression and 2 weeks later, we subcutaneously injected collagenase twice per week in the back skin and measured invasion and tumour formation 6 weeks following TAM administration. Collagenase injections rapidly decreased the abundance and density of collagen fibres (Fig. 5e, f). Upon collagenase administration in control mice, invasion of epidermal cells into the dermis was not observed and the basal lamina was unaffected (Extended data Fig. 12a-c). However, decreasing the abundance and thickness of the collagen bundles without impairing their orientation in the back skin by collagenase injection overcome the resistance of the back skin to SmoM2 transformation and led to the development of tumorigenic lesions that invade the dermis. These invasive lesions begun to express EHFP markers similarly to SmoM2 tumours that grow spontaneously in the ear and tail skin (Fig. 5e-i, and Extended data Fig. 9c-f). To assess whether the inflammation associated with collagenase administration could promote invasion by itself, we induced inflammation and assessed whether they promote dermal invasion of SmoM2 clones. Whereas Bleomcyin or Imiquimod administration induced strong inflammation in the dermis, they did not promote invasion of the SmoM2 cells in the back skin, demonstrating that inflammation is not sufficient to promote BCC formation (Extended data Fig. 12d-i).

It has been previously shown that aging is associated with decrease in collagen density in the skin30, 31. We therefore assessed the collagen density by immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy using the second harmonic generation in aged mice. Our analysis showed that the level of collagen drastically decreased in mice over 1.5 years old. To assess whether the decrease in collagen density associated with ageing promotes the ability of back skin epidermis to undergo tumorigenesis, we induced the expression of oncogene SmoM2 on 1.5 years old mice and analysed BCC formation 6 weeks after oncogene expression. Interestingly, SmoM2 expressing cells invaded the dermis of the back skin of aged mice, and this invasion was associated with EHFP reprograming (Fig. 5j-o, s). Moreover, we found that in aged mice, there was a decrease in lateral expansion concomitant with an increase in the vertical invasion of the clones (Fig. 5t-u). The decrease in the lateral expansion was associated with a decrease in the ability of SmoM2 expressing cells to promote the terminal differentiation of the WT border cells in the back skin (Fig. 5v). These data show the balance between lateral expansion and vertical outgrowth upon SmoM2 expression and further reinforce the notion that the level of collagen expression dictates the competence for BCC initiation.

UV exposure is also well known to decrease Collagen expression32. UVB are absorbed by the epidermis whereas UVA penetrates to the dermis and induces premature aging of the skin and reduced collagen 1 expression33. To assess whether decrease in collagen expression following chronic UVA exposure promotes the formation of BCC, we irradiated the back skin of the mice using a UVA lamp 5 times per week for a total of 10 weeks34. At the end of the 4th week, we induced SmoM2 expression and assessed the Col1 expression and the formation of BCC. Chronic UVA exposure led to a strong reduction in the level of collagen 1. Very interestingly, the decrease in Col1 expression induced by chronic UVA exposure expression was associated with the ability of SmoM2 expressing cells in the back skin to lead to BCC formation and invasion as well as EHFP reprograming (Fig. 5j-l, p-s). The complete penetrance of the invasion phenotype in the back skin following UVA administration suggests that random secondary mutations are not likely to be the driving force of tumor invasion. Altogether these data indicate that high level of Col1 expression in the dermis is responsible for the natural resistance of the back skin epidermis to form BCC upon SmoM2 expression and suggest that the contact of oncogene expressing cells with the dermal microenvironment is important for the EHFP reprogramming of these cells during tumour initiation.

Discussion

In this study, we use for the first time intravital microscopy to track and follow the same cells expressing the SmoM2 oncogene overtime in living animals from the first targeted cell until the development of invasive tumours. We demonstrate that not all epidermal cells across the body are equally sensitive to oncogenic transformation following SmoM2 expression. Whereas the ear epidermis is susceptible to oncogenic transformation, the back skin is profoundly resistant. While the extent of clonal expansion is similar between the two tissues, the oncogene-targeted clones expand and compete with the WT basal cells by promoting their apoptosis and terminal differentiation in a lateral manner without invading the dermis. The demonstration that oncogene induced cell competition does not necessarily lead to tumor initiation can explain why mutated clones for cancer drivers can be found in normal human tissues without any signs of neoplastic transformation13,35. In contrast, in the ear epidermis, after a short phase of lateral expansion, the oncogene targeted clones begin to grow downward and invade the dermis. The switch between lateral to vertical growth and the early steps of tumour invasion is associated with a reprograming of the adult IFE SC into EHFP like fate that is essential for BCC initiation28,29(Extended data Fig. 14).

Our data shows that only the susceptible part of the skin and not the resistant back skin epidermis undergo this EHFP reprograming following oncogene expression. We demonstrate that the resistance to oncogene transformation is dictated by the stiffness of the dermis and the composition of the ECM. These data are consistent with the study of Fiore and colleagues showing that during embryonic development, during which collagen expression is almost absent36, the remodelling of a soft basal lamina promotes BCC formation17. Decreasing collagen concentration by collagenase injection, following chronic UVA exposure and during natural ageing rescues the ability of oncogene expressing cells in the back skin to undergo tumour invasion, EHFP reprograming of oncogene expressing cells and BCC formation, demonstrating that these key features are dictated by the contact of oncogene expressing cells with the ECM of the deeper dermis. These data are relevant for human skin cancer, as BCC also preferentially arises from certain body locations such as ear and nose compared to the cheek that presented a larger surface and similarly exposed to UV, and similarly to UVA exposure, chronic sun exposure is one of the most important risk factors of BCC formation and finally, similarly to aged mouse, BCC preferentially develops in older humans.

Future studies will be required to investigate the relevance of these findings for constraining or promoting clonal cell competition and tumour development in the different tissues that present mutations in cancer driver genes8. These findings also have implications for understanding the cellular non-autonomous factors that are important for tumour initiation and identifying the cells within a tissue that are more susceptible to undergo neoplastic transformation.

Methods

Mice

Mouse colonies were housed and maintained in a certified animal facility in accordance with the European guidelines. All animal procedures were approved by the corresponding ethical committee (Commission d’Ethique et du Bien Être Animal (CEBEA), Faculty of Medicine, Université Libre de Bruxelles) under protocol numbers 794 and 820. CEBEA follows the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes. This study is compliant with all ethical regulations regarding animal research. Mice were monitored daily and euthanized when tumors became macroscopic, if the skin was ulcerated or haemorrhagic, or if the mouse lost >20% of its initial weight or showed any other sign of distress (based on general health and spontaneous activity). All the experiments complied strictly with the protocols approved by ethical committee. The housing conditions of all animals were strictly following the ethical regulations. The room temperature ranged from 20 and 24 °C. The relative ambient humidity at the level of mouse cages was 55 ± 10%. Each cage was provided with food, water and two types of nesting material. A semi-natural light cycle of 12:12 was used. All the experiments complied strictly with the protocols approved by ethical committee.

Mouse strains

The K14CreER transgenic mouse model was generated and provided by E. Fuchs laboratory, Rockefeller University, USA. This mouse model is available at the Jackson Laboratory, stock # 005107. The Rosa26-LSL-SMOM2-YFP mouse line was imported from the Jackson Laboratory (stock # 005130). The Rosa26-LSL-mT/mG mouse line was imported from the Jackson Laboratory (stock # 07576). The iChr2-Control-Mosaic was provided by Rui Benedito’s lab and is now available in Jackson Laboratory (stock # 031302). All mice used in this study were composed of males and females with mixed genetic backgrounds.

Inducing oncogene activation

Mice were induced between 1.5 and 4 months of age (apart from the experiment on old mice) with tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 10% Ethanol and 90% sunflower oil (Sigma). The quantity of tamoxifen administrated to mice was adapted in accordance with their weight. For non-clonal induction: mice were treated with a single intraperitoneal injection (IP) of tamoxifen at a dosage of 1mg/30g. For clonal induction : mice were treated with a single intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen at a dosage of 0,075mg/30g (ear skin clonal dose) or 0,4mg/30g (back skin clonal dose). Mice were sacrificed at different time points post induction.

In vivo lineage tracing and imaging

Mice were first anesthetized with vaporized isoflurane delivered in a box at 4% isoflurane + 2% O2. Then, they were placed into the microscope and maintained under anaesthesia by a nose cone delivering isoflurane at 2% isoflurane + 0,3% O2 throughout the course of imaging sessions. Temperature inside the microscope was set at 29°C to avoid hypothermia. Before the start of each experiment, ear skin and back skin were shaved using clippers and depilatory cream. To navigate back to the same field of view and follow the behaviours of the same epidermal clones over multiple days, tattoos, and inherent landmarks of the skin such as hair follicles distribution were used. Ear skin was tattooed using a small needle and carbon ink as described in Pineda et al., nature protocol, 2015. Back skin was tattooed using a tattoo machine. Image were acquired on a LSM 880 confocal (Zeiss) fitted on a AxioObserver Z NLO inverted microscope (Zeiss). Multiphoton excitation from a tunable InSight X3 laser (Spectra Physics) was set at 920nm to image second harmonic generation (SHG), GFP and dtTomato using emission filters (Chroma) KP 475nm, BP 510-540nm and BP 580-640nm, respectively, in front of GaAsP non-descanned detectors (NDD) 5Zeiss). Serial optical sections were acquired through a 40x dry lens (Zeiss) with a 0,6-1 μm step to image the entire thickness of the epidermis, invasion of the dermis by BCC and a part of the ECM thanks to the second harmonic signal.

Quantification of SHG intensity

Measurements of the intensity of SHG were analysed manually in ImageJ software. For the intensity of SHG, we analysed 3 random area at 40x magnification for the ear and for the back skin from 4 different mice. The analysed area was defined manually to exclude hair follicles.

Measurement of the Aspect Ratio (AR) of epidermal cells

Measurements of AR were performed manually using ImageJ software.

Collagen fiber bundles measurements

Measurements of the collagen fiber bundles were analysed manually in ImageJ software. For that, we measure at least 311bundles for the ear, 263 bundles for the back skin and 533 bundles for back skin with collagenase from 3 random area at 40x magnification from 3 different mice.

Orientation of Collagen fiber bundles measurements

For the orientation of the collagen fiber bundles, we used the plug-in OrientationJ in ImageJ to generate the HBS color code and the histogram of local angles. Orientations are automatically calculated according to the collagen fiber bundles and are represented as color images with the orientation encoded in a hue-saturation-brightness (HSB) map. We analysed 3 random area at 40x magnification for the WT ear, the WT back skin and the back skin with collagenase from 3 different mice.

Immunofluorescences on sections

After dissection, ear skin and back skin samples were embedded without prior fixation into optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura), frozen on dry ice and kept at -80°C. Tissues were then cut into 6-10 μm sections using a CM3050S Leica cryostat (Leica Microsystems). For immunostainings, frozen sections were dried few minutes at room temperature, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and washed three times in PBS before being incubated with a blocking buffer (5% horse serum, 1% BSA and 0,2% triton-X100) for one hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted into blocking buffer, overnight at 4°C. The day after, sections were washed three times in PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies diluted at 1:400 and Hoechst (10mg/ml) diluted at 1:2000 in blocking buffer for one hour at room temperature. Sections were finally rinsed three times (5min) in PBS and mounted in DAKO mounting medium supplemented with 2,5% Dalco (Sigma). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-GFP (goat polyclonal; Abcam, ab6673; 1:1000), anti-GFP (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, ab6556; 1:2000), anti-CD104/ß4 integrin (rat; BD Biosciences, 346-11A; 1:200); anti-K10 (rabbit; Covance, 905404 ; 1:2000); anti-K1 (rabbit, Covance; 1/4000), anti-K15 (chicken; Covance, 833904 ; 1/15000); anti-Lhx2 (Goat,; Santa Cruz, sc-19344; 1/500); anti-Lef1 (rabbit, cell signalling, 2230 ; 1/200); anti-P-Cadherin (Rat; Invitrogen, 32000Z ; 1/1000); anti-Vimentin (Rabbit; Abcam, 92547 ; 1/1000); anti-CD45;(Rat; BD Biosciences, 103106 ; 1/50), anti-CD68 (Rabbit; Abcam, ab125212; 1/1000), anti-CD8 (Rabbit; Abcam, ab203035; 1/200), anti-CD4 ((Rat; Biolegend, 100412; 1/200), anti-K14 (Chicken, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #MA5-11599, 1:2000), anti-activeYap1 (Rabbit; Abcam, ab205270; 1/200), anti-Phospho-Myosin Light Chain 2 (Rabbit; Cell signalling, 3674S; 1/200), Phalloidin (Invitrogen, A22287; 1/400), EdU (ThermoFisher, c10340), anti-CC3 (Rabbit; R&D, AF835 ; 1/400), anti-Lamin5 (Rabbit; Abcam, ab14509 ; 1/200). The following secondary antibodies were used (dilution 1:400): anti-rabbit, anti-rat, anti-chicken and anti-goat conjugated either to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) or Rhodamine Red-X (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or Cyanine5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). All confocal images from whole-mount epidermis were acquired at room temperature with a LSM780 confocal system fitted on an AxioExaminer Z1 upright microscope equipped with C-Apochromat 40x/1,1 water.

RNA-FISH

Ear and back skin were dissected from the SmoM2 YFP and control mice and were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura) and cut into 5–8μm frozen sections using a CM3050S Leica cryostat (Leica Microsystems). Sections were fixed for 30min in 4%PFA at 4°C and the in-situ protocol was performed according to the manufacturer instructions (Advanced Cell diagnostics). The following mouse probes were used: Mm-Col1a1 (319371) and MmCol1a2 (585461-C2).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Ear auricle and back skin samples were fixed for 24h in 10% neutral buffered formalin and routinely embedded in paraffin wax. Four mm thick sections were placed on Superfrost microscope slides glass (Gerhard Menzel GmbH) or Flex IHC Microscope Slides (Dako Agilent Technologies) and dried at 37°C. Immunohistochemistry for the detection of Collagen I was performed using a rabbit monoclonal antibody (Abcam ab270993, 1:1000) on a Dako Autostainer Link 48 (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, USA). Briefly, deparaffinized and hydrated tissue sections were treated with H2O2 3% for 5 min to quench endogenous and incubated at 97°C in EDTA buffer (pH9.0) for 5 min for antigen retrieval. Tissue sections were incubated 40 min with the primary antibody, washed and incubated 20 min with Flex immunoperoxidase Polymer Anti-Rabbit IgG (Agilent). Immunolabelling was visualized by incubation with diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide for 10 min and counterstain with Hematoxylin. The slides were digitized using slide scanners Nanozoomer 2.0 HT (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) and analysed using QuPath (0.3.2).

Epidermal whole mount and immunostaining

The ear and the back skin were dissected from the experimental and control mice, cut into small pieces and incubated in 20mM PBS-EDTA on a rocking plate at 37 0 C for 1 hr. Epidermis was separated from the dermis by using forceps. Washed 2 times with 1X PBS and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1hr at room temperature. Washed 3 times with 1X PBS for 5 min each wash and then stored in PBS and sodium azide (0.2%) at 4 0 C. For immunofluorescence staining, we used the pieces of epidermal sheet, incubated in blocking buffer (1% BSA,5% Horse serum, 0.8% Triton in 1X PBS) for 3 hours at room temperature on rocking plate. For primary antibody staining, samples were incubated with primary antibody anti-Integrinβ4 (rat, 1:200, BD Biosciences), Keratin 14 (1: 2000), Keratin 10 (1: 1000), anti-CC3 (1:600), anti-activeYap1 (1/200) and Phalloidin (1:200) for overnight at room temperature on rocking plate (100 rpm). Samples were then washed for 3 times with PBS 0.2% Tween for 20 minutes each and then incubated with secondary antibody and Hoechst (1: 2000) for nuclear staining for 2 hrs at room temperature on rocking plate. Samples were washed 3 times with PBS 0.2% Tween for 20 minutes each and then mounted in DAKO mounting medium by keeping hairy side down.

For BrdU staining, epidermal sheets are incubated in 1M HCL at 37 0 C for 45 min and then washed with 1X PBS, 3 times for 10 min each. Overnight incubation with primary antibody anti-BrdU (rat, 1:200, Abcam) in blocking buffer at room temperature on rocking plate. The next day, samples were washed for 3 times with PBS 0.2% Tween for 20 minutes each and then incubated with secondary antibody and Hoechst (1:500) for 2hrs at room temperature on rocking plate. Samples were washed 3 times with PBS 0.2% Tween for 20 minutes each and then mounted in DAKO mounting medium by keeping hairy side down. For EdU staining, performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermofisher). For co-expression with EdU, first performed the K14 or other primary antibody staining then followed the EdU protocol.

Proliferation experiments

For proliferation experiments, mice were injected with a single intraperitoneal injection of EdU (2.5 mg/ml in PBS) 4hrs before sacrifice. We performed EdU staining as recommended by the manufacturer. For the quantification at least an area of 1,5 mm per animal was analysed with Zen2012 (Black Edition) software (Zeiss) to determine the percentage of EdU positive cells.

Cell fate divisions

To understand the dynamics of cell fate in the expansion of SmoM2 cells in the Ear as well as Back skin we performed BrdU pulse chase assay which allows to assess the fate of the division (References Aragona et al, Nature 2020., Sanchez-Danes et al, Nature 2016). Mice were injected with a single intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (1.25 μg/μl) 24hrs before sacrifice to capture the doublets of BrdU. We analysed BrdU doublets with SmoM2 YFP with the location of BrdU either in the basal-basal, basal-suprabasal or suprabasal-suprabasal position.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Ear and back skin of CD1 mice and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP (200 mg wet weight) was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and crushed using a mortar and pestle to obtain powder tissue. 3 mice were using for each condition (WT and SmoM2). For each sample, 10-70 mg skin or ear tissue was transferred to 1.5 ml tubes and 50 μl lysis buffer containing 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB, pH 8.5) was added. The samples were mechanically disrupted by 2 cycles of grinding with a disposable micropestle and heating to 90°C in between cycles. Another 50 μl lysis buffer was added, the resulting lysate was transferred to a 96-well PIXUL plate and sonicated with a PIXUL Multisample sonicator (Active Motif) for 60 minutes with default settings (Pulse 50 cycles, PRF 1 kHz, Burst Rate 20 Hz). After centrifugation of the samples for 5 minutes at 2,204 x g and room temperature (RT) to remove insoluble components, the protein concentration was measured by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific) and from each sample 300 μg of protein was isolated to continue the protocol. Proteins were reduced and alkylated by addition of 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride and 40 mM chloroacetamide and incubation for 10 minutes at 95°C in the dark. Phosphoric acid was added to a final concentration of 1.2% and subsequently samples were diluted 7-fold with binding buffer containing 90% methanol in 100 mM TEAB, pH 7.55. The samples were loaded on the 96-well S-Trap™ plate (Protifi) and a Resolvex® A200 positive pressure workstation (Tecan Group Ltd) was used for semi-automatic processing. After protein binding, the S-trap™ plate was washed three times with 200 μl binding buffer. A new deepwell plate was placed below the 96-well S-Trap™ plate and trypsin (1/100, w/w) was added for digestion overnight at 37°C. Also using the Resolvex® A200 workstation, peptides were eluted in three times, first with 80 μl 50 mM TEAB, then with 80 μl 0.2% formic acid (FA) in water and finally with 80 μl 0.2% FA in water/acetonitrile (ACN) (50/50, v/v). Eluted peptides were dried completely by vacuum centrifugation.

TMTproTM 18-plex labels (0.5 mg, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were equilibrated to RT immediately before use and dissolved in 20 μl anhydrous ACN. The dried peptides were re-suspended in 90 μl 100 mM TEAB (pH 8.5), peptide concentration was determined on a Lunatic spectrophotometer (Unchained Labs)38 and peptide amount was adjusted to 50 μg for each sample. Peptides were labelled for 1 hour at RT using 0.25 mg of TMTProTM label (labels used: 126, 127C, 128C: K14CrER Rosa SmoM2 Dermis EAR replicates; 127N, 128N, 129N: K14CrER Rosa SmoM2 Dermis Back skin replicates; 129C, 132C, 133C: WT Dermis EAR replicates; 130N, 133N, 134N: WT Dermis Back skin replicates). The reaction was quenched for 15 min at RT by addition of hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 0.2%. The 12 labelled samples were combined, 100 μg labelled peptides was isolated, dried by vacuum centrifugation, re-dissolved in 100 μl 50 mM TEAB and 13 IUBMB mU Peptide-N-Glycosidase F (PNGaseF, made in-house) was added for deglycosylation at 37°C overnight. Peptides were acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to lower the pH below 3 and desalted on reversed phase (RP) C18 OMIX tips (Agilent). The tips were first washed 3 times with 100 μl pre-wash buffer (0.1% TFA in water/ACN (20:80, v/v)) and pre-equilibrated 5 times with 100 μl of wash buffer (0.1% TFA in water) before the sample was loaded on the tip. After peptide binding, the tip was washed 3 times with 100 μl of wash buffer and peptides were eluted twice with 100 μl elution buffer (0.1% TFA in water/ACN (40:60, v/v)). The combined elutions were transferred to HPLC inserts and dried in a vacuum concentrator.

Vacuum dried peptides were re-dissolved in 100 μl solvent A (0.1% TFA in water/ACN (98:2, v/v)) and 95 μl was injected for fractionation by RP-HPLC (Agilent series 1200) connected to a Probot fractionator (LC Packings). Peptides were first loaded in solvent A on a 4 cm pre-column (made in-house, 250 μm internal diameter (ID), 5 μm C18 beads, Dr. Maisch) for 10 min at 25 μl/min and then separated on a 15 cm analytical column (made in-house, 250 μm ID, 3 μm C18 beads, Dr Maisch). Elution was done using a linear gradient from 100% RP-HPLC solvent A (10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5) in water/ACN (98:2, v/v)) to 100% RP-HPLC solvent B (70% ACN, 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5)) in 100 min at a constant flow rate of 3 μL/min. Fractions were collected every minute between 20 and 92 minutes and pooled every 24 minutes to generate a total of 24 samples for LC-MS/MS analysis. All 24 fractions were dried under vacuum in HPLC inserts and stored at -20°C until further use.

Purified peptides were re-dissolved in 20 μl loading solvent A (0.1% TFA in water/ACN (98:2, v/v)) and the peptide concentration was determined on a Lunatic spectrophotometer (Unchained Lab). 15 μl of each sample was injected for LC-MS/MS analysis on an Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system in-line connected to an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo). Trapping was performed at 20 μl/min for 2 min in loading solvent A on a (Pepmap, 300 μm ID, 5 μm beads, C18, Thermo). The peptides were separated on a 110cm μPAC column (Thermo), kept at a constant temperature of 50°C. Peptides were eluted by a non-linear gradient starting from 2% MS solvent B (0.1% FA in ACN) reaching 26.4% MS solvent B in 45 min, 44% MS solvent B in 55 min and 56% MS solvent B in 60 min starting at a flowrate of 600 nl/min for 5 minutes, and completing the run at a flow rate of 300 nl/min, followed by a 5-minute wash at 56% MS solvent B and re-equilibration with MS solvent A (0.1% FA in water).

The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode, automatically switching between MS and MS/MS acquisition in TopSpeed mode. Full-scan MS spectra (375-1500 m/z) were acquired at a resolution of 120,000 in the Orbitrap analyser after accumulation to a target AGC value of 200,000 with a maximum injection time of 50 ms. The precursor ions were filtered for charge states (2-7), dynamic exclusion (60 s; +/- 10 ppm window) and intensity (minimal intensity of 5E4). The precursor ions were selected in the quadrupole with an isolation window of 0.7 Da and accumulated to an AGC target of 1.2E4 or a maximum injection time of 100 ms and activated using CID fragmentation (35% NCE). The fragments were analysed in the Ion Trap Analyzer at turbo scan rate. 10 most intense MS2 fragments were selected in the quadrupole using MS3 multi-notch isolation windows of 2 m/z. An orbitrap resolution of 60k was used with an AGC target of 1.0e5 or a maximum injection time of 118 ms and activated using HCD fragmentation (65% NCE). QCloud was used to control instrument longitudinal performance during the project39.

LC-MS/MS runs of all 12 samples were searched together using the MaxQuant algorithm (version 2.1.3.0) with mainly default search settings, including a false discovery rate set at 1% on peptide and protein level. Spectra were searched against the mouse protein sequences in the Swiss-Prot database (database release version of 2022_01), containing 21,986 sequences (www.uniprot.org). The mass tolerance for precursor and fragment ions was set to 4.5 and 20 ppm, respectively, during the main search. Enzyme specificity was set to C-terminal of arginine and lysine, also allowing cleavage at Arg/Lys-Pro bonds with a maximum of two missed cleavages. Variable modifications were set to oxidation of methionine residues and acetylation of protein N-termini whereas carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues was set as fixed modification. In order to reduce the number of spectra that suffer from co-fragmentation, the precursor ion fraction (PIF) option was set to 75%. Only proteins with at least one unique or razor peptide were retained leading to the identification of 2,849 proteins. MS2-based quantification using TMTpro™ labels was chosen as quantification method and a minimum ratio count of two unique peptides was required for quantification. Further data analysis was performed with an in-house R script. Reverse database hits were removed from the MaxQuant proteingroups file, corrected reporter intensities were log2 transformed & median normalized and replicate samples were grouped. Proteins with less than three valid values in at least one group were removed and missing values were imputed by random sampling from a normal distribution cantered around each sample’s detection limit (package DEP) leading to a list of 2,781 quantified proteins that was used for further data analysis. To compare protein intensities between pairs of sample groups, statistical testing for differences between group means was performed, using the package limma. Statistical significance for differential regulation was set to a false discovery rate (FDR, Benjamini-Hochberg method) of 0.05 and |log2FC| = 1 and volcano plots were generated. Z-scored protein intensities from differentially abundant hits were plotted in a heatmap after non-supervised hierarchical clustering. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD041644 and 10.6019/PXD041644.

Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy work, mouse skin tissue samples were cut to a minimal size (1 mm x 1mm) and fixed with 2 % glutaraldehyde/2 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. Further processing was done according using standard protocols, including a number of optimized steps for skin tissue, as described previously40. Resulting 60 nm ultrathin sections were analysed with a Tecnai 12-biotwin transmission electron microscope (ThermoFisher) and representative images were taken with a 2K CCD Veleta camera (EMSIS, Münster, Germany).

Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements of extracellular matrix stiffness were performed on freshly cut 16 μm thick cryosections using the JPK Nano Wizard 2 (Bruker Nano) AFM mounted on an Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus) and operated using the JPK SPM control software v.5. Briefly, cryosections were equilibrated in PBS supplemented with protease inhibitors and measurements were performed within 20 min of thawing the samples. Silicon Nitride cantilevers with 3.5 μm colloidal particle (NanoAndMore GbmbH) were used for the nanoindentation experiments. For all of the indentation experiments, forces of up to 2 nN were applied, and the velocities of cantilever approach and retraction were kept constant at 2 μm /second. Before fitting the Hertz model corrected by the tip geometry to obtain Young’s Modulus (Poisson’s ratio of 0,5), the offset was removed from the baseline, the contact point was identified, and cantilever bending was subtracted from all force curves.

Dissociation of epidermal cells and Flow cytometry for cell sorting

To isolate skin epidermal cells, ears were dissected, opened in two along the cartilage with forceps and incubated in DMEM (Dubelcco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium-Gibco, thermo Fisher Scientific) - 0,25% Trypsin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C. The back skin was first shaved with electric clippers, dissected and the hypodermis was then removed by scratching it with a scalpel. The remaining tissue (epidermis-dermis) was finally incubated in DMEM-0,25% trypsin overnight at 4°C by placing the dermis in contact with the solution. The day after, the epidermis was carefully separated from the dermis by using a scalpel and then incubated on a rocking plate (100 rpm) at room temperature for 5 min. Trypsin was neutralized by adding DMEM supplemented with 5% of Chelex-treated Fetal Calf Serum (CFCS) and epidermal cells were mechanically dissociated by pipetting 10 times. Samples were filtrated on a 70μm filter then on a 40μm filter and washed in a PBS-2% CFCS. Single cells were incubated with a biotinylated anti-CD34 primary antibody (clone RAM34; BD Biosciences; dilution 1:50) diluted in PBS-2% CFSC, for one hour on ice on a rocking plate, and protected from light. Cells were washed with PBS-2% CFCS, incubated for 45 min on ice, on a rocking plate, with streptavidin-APC secondary antibody (BD Biosciences; 1:400), washed again and finally resuspended in a Hoechst (10mg/ml) solution diluted at 1:4000 in PBS-2% CFCS. Cell sorting was performed on a BD FACS Aria II using the FACSDiva software at the ULB Flow Cytometry Platform: living epidermal cells were gated by forward scatter, side scatter, and negative for Hoechst. SmoM2 mutated cells were isolated based on the expression of the YFP fused to the oncogene. Smom2-YFP expressing cells from the hair follicle bulge were excluded by the CD34-APC staining. For wild type tissues living IFE and infundibulum cells were sorted on the negative expression of the CD34 marker only. 20 000 cells were sorted for each sample and the samples harvested from three different mice were pooled together to obtain a total number of 60 000 cells for both tissues: ear skin and back skin.

Single cell RNA library preparation and sequencing

10,000 single cells from the back skin and ear skin were loaded onto each channel of the Chromium Single Cell 3’ microfluidic chips (V2-chemistry, PN-120232, 10X Genomics) and barcoded with a 10X Chromium controller according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (10X Genomics). RNA from the barcoded cells was subsequently reverse transcribed, followed by amplification, shearing 5' adaptor and sample index attachment. The libraries were prepared using the Chromium Single Cell 3' Library Kit (V3-chemistry, PN-120233, 10X Genomics) and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 (paired-end 100bp reads).

Single cell transcriptomic data analysis

Sequencing reads were aligned and annotated with the mm10-2020-A reference dataset as provided by 10X Genomics and demultiplexed using CellRanger (v.5.0.0) with default parameters. Further downstream analyses were carried out individually for each of the four samples (Ear Smo, Ear WT, Back Smo, Back WT). Quality control and downstream analysis were performed using the Seurat R package (v.4.1.0). For each sample, all of the cells passed the following criteria: showed expression of more than 2000 and less than 7000 unique genes and had less than 10% UMI counts belonging to mitochondrial sequences. Read counts were normalized by NormalizeData function of Seurat, with parameter ‘normalization.method = "LogNormalize" and scale.factor=10000’. A PCA for each sample was calculated using the scaled expression data of the most variable genes (identified as outliers on a mean/variability plot, implemented in the FindVariableGenes). UMAP calculation and graphbased clustering were done for each sample using the appropriate functions from Seurat (default parameters) with the respective PCA results as input. The clusters expressing sebaceous gland markers (Scdl, Lpl, Mgstl, Ldhb, Nrp2) and stromal cells are excluded, and dimensionality has been recalculated. The final resolutions were set to 0.5 for wildtype and 0.7 for Smo samples, after testing a range from 0.3 to 0.9. Given that the obtained clustering sensitivity for a given resolution is dependent on the number of cells of that subpopulation in each respective sample, we swept over the same range of resolutions for the other samples, to assure the presence/absence of described clusters in all samples. Selected resolutions are the best to reflect the biological heterogeneity between different cell types and analysis of the clonal data, identifying (which cell types should be ngood to tell). In addition, to verify proliferating stages, the S-phase and GS/M-phase scores were regressed out by CellCycleScoring function, implemented in the Seurat. Geneset enrichment analysis on individual dataset was performed using AUCell R package, with default parameters. The geneset for identification of cells with active genesets are defined as EHFP signature on previous study28.For visualization of AUC (Area Under the Curve) score calculated by AUCell, the AUC score matrix has been embedded into each dataset as additional assay with CreateAssayObject function of Seurat.

Mice treatment

250 μl per cm2 of collagenase type I (Sigma; 0,5 mg/ml diluted in PBS) was administrated every twice a week by subcutaneous injections on the back skin, starting 2 weeks after oncogene induction (Tamoxifen administration). Bleomycin sulfate (Abcam, 5 mg/mL diluted in PBS) was administrated every twice a week by subcutaneous injections on the back skin (150-200 μl per cm2) and in the dermis of the ear (30 μl), starting 1 month before oncogene induction and until 6 weeks after. Imiquimod (Aldara®) was directly applied on the back skin 5 days per week, starting 2 weeks after oncogene induction (Tamoxifen administration). To irradiate the back skin, we used a UV-LED lamp (Uwave) emitting at a wavelength of 365 nm (UV-A). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and then irradiated for 4 min at a distance of 20-25 cm 5 days per week starting 1 month before oncogene induction until 6 weeks after (10 weeks in total).

Statistical Analysis and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 and R (version 4.2.0). Data are expressed as mean ± standard bar error of the mean (S.E.M). Normality was tested using Shapiro-Wilk test. For the datasets following normality, P-value was estimated with paired-end t-test. If the dataset follows normality and the number of observation is more than 30, two-tailed z-test is applied. For the datasets which do not follow normality, P-value was calculated with Mann-Whitney test. If there were more than three samples given as input, Kruskal-Wallis test was applied. The p-values calculated via different test were corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. For all the figures, the number of mice, the number of clones and the number of areas analysed are indicated in the figure legend. For all the figures, the number of mice, the number of clones and the number of areas analysed are indicated in the figure legend. For all the images, each experiment was repeated independently with similar results at least 3 times.

Extended Data

Extended data Fig. 1 |. Intravital microscopy set up to follow the same clone overtime in living animals.

a. Set-up of intravital microscope. b, c. Making tattoos in the mouse ear (b) and back skin (c). d-e. Method combining tattoo and the stable pattern o f hair follicles to establish spatial coordinate to monitor and track the same clones in the skin by intravital microscopy overtime. For the ear (d), we used a 30g needle to make 3 punctiform tattoos. The tattoos are visible at 10x magnification. At 10x magnification, we can select an easily identifiable area using the hair follicles (yellow dashed square). At 40X magnification, we can image an area at the single cell resolution. This area will be revisited overtime to monitor cell dynamics. The same strategy is used to follow the same clones overtime in the back skin, with the difference that tattooing is performed using a tattoo machine. For more details, see Methods. White dashed line: delimitation of the tattoo. Hair follicles are numbered.

Extended data Fig. 2 |. Clonal dynamics of normal epidermis and mode of cell division of SmoM2-cells in ear and back skin.

a, b. Microscopy analysis of β4 integrin (β4) (a) and Laminin-332 (Lam5) (b) in SmoM2 clones in the ear and the back skin 6 weeks following tamoxifen administration. Note the small disruption of the basal lamina (BL) at the leading edge of SmoM2 clones invading the dermis (yellow arrows). c, d. Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of the immunostainings of β4 (left) and Lam5 (right) in control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. Measurements were performed along the BL in control and at the leading edge of invading BCC using ImageJ. For the control, 21 areas for β4 and 20 areas Lam5 were analysed (n=3). For SmoM2, 41 BCC for β4 and 56 BCC for Lam5 (n=3). Two-tailed z-test. e. Transmission electron microscopical images of ear and back skin ultrathin upon sections from control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. Representative images show the remodelling of the BL (increased (blue arrow) or reduced (yellow arrow)) observed at the leading edge of BCC in the ear epidermis whereas the BL remains intact in the back skin after SmoM2 expression. EC: epidermal cell. BL: basal lamina. Scale bar: 200 nm. f. Quantification of the total number of cells per clone in WT ear epidermis at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after clonal marking following tamoxifen injection by intravital microscopy (n=4). Kruskal-Wallis test. g. Intravital imaging of the same clones in the outer part of the ear skin at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after tamoxifen administration to K14CreER/Ichr-Ctrl-mosaic mice. h. Whole mount images of epidermis of K14CreER/Ichr-Ctrl-mosaic mice from the inner and outer part of the ear, the back and the tail at 45 days after tamoxifen administration. 40x Magnification. i. Quantification of the number of cells per clones at 6 weeks on whole mount of epidermis of K14CreER/Ichr-Ctrl-mosaic. The number of basal cells found by intravital microscopy was similar to the one found by whole mount immunostaining. (n=4 mice). Kruskal-Wallis test. j, k. BrdU pulse-chase analysis to analyse the fate of two dividing daughter cells (doublets). Whole mount images of SmoM2-clones in the ear (j) and the back skin (k) showing the location of BrdU doublets: two BrdU+ basal cells, one basal and one suprabasal BrdU+ cells or two suprabasal BrdU+ cells. l. Percentage of cell fate outcome in WT and SmoM2 cells in the ear and in the back skin. WT ear cells (61 BrdU+ doublets from 3 mice), ear 6 weeks SmoM2-clones (110 BrdU+ doublets from 4 mice), ear 12 weeks-SmoM2-clones (85 BrdU+ doublets from 3 mice), WT back skin cells (113 BrdU+ doublets from 3 mice), 6 weeks SmoM2-clones (137 BrdU+ doublets from 4 mice) and 12 weeks SmoM2-clones (115 BrdU+ doublets from 3 mice). These data show that in WT ear and back skin, most division present asymmetric cell fate outcome, whereas most SmoM2 cells in WT ear and back skin divide symmetrically. a, b, g, h. Scale bar, 20μm. f, i. In parentheses, the number of clones. c, d, f, i. Mean +- SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Expression of actin, phospho-myosin and active YAP in SmoM2 clones in the ear and back skin epidermis.

a-b. Immunostainings for actin (phalloidin) (a) phospho-myosin II (P-Myosin II) (b) in control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression, revealing an increase in the level of F-actin (a) and phospho-myosin II (b) in SmoM2-cells in the ear. In addition, some WT cells at the border of the ear clones were also positive for phospho-myosin II. No change of phalloidin or phospho-myosin II was found in the back skin. Red: Phalloidin or phospho-myosin II; Blue: Hoechst. Scale bar= 20 μm. c. Immunostainings for active Yap (aYap) in control and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP mice at 6 weeks after SmoM2 activation, revealing an increase expression of nuclear YAP at the leading edge of SmoM2 expressing clones and in the WT cells at the border of the clone in the ear. Only rare nuclear YAP expressing cells were found in the SmoM2 expressing cells of the back skin. Red: aYAP (d) Green: SmoM2; Blue: Hoechst Scale bar= 20 μm. d, e. Immunostainings on whole mount for actin (phalloidin) (d), and active-Yap (aYap) in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG 3 weeks after SmoM2 activation, showing a higher level of actin expression and a-Yap in SmoM2-cells in the ear. No change of actin or aYap was found in the back skin. Blue: Hoechst. Scale bar= 20 μm

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Cell competition, proliferation and apoptosis surrounding SmoM2 clones in the back skin and the ear.

a. Immunostainings of EdU in ear and the back skin of K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. b. Quantification EdU-positive cells in SmoM2-clones in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP at 3 (n=3), 6 (n=4 for the ear and n=5 for the back skin), and 12 weeks (n=3) after SmoM2 activation showing an increase of proliferation in SmoM2-clones compared to the control (n=3). Mean +- SEM. t-test. c. Intravital microscopy analysis of the cell density in WT cells and SmoM2 clones in the ear and the back skin of K14CreER/ Rosa-mT/mG and K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG before and at 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. d-e. Quantification of aspect ratio of the SmoM2 cells at the border (d) and at the centre (e) of the clone 3 and 6 weeks after SmoM2 expression. These data show that the SmoM2 cells adopt an elongated shape in the ear whereas in the back skin, SmoM2-cells are more deformed in the centre of the clones than at the periphery. In blue, the average. n= 3 mice for each conditions. Mean +- SEM. Two-tailed z-test. f. Time-lapse intravital microscopy analysis a SmoM2-clone in the back skin of K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG mouse 10 weeks after tamoxifen administration at different time points for 56 hours showing the clonal expansion of SmoM2 cells and out competition of WT cells surrounding the SmoM2-clone. g. Immunostaining of cleaved Caspase 3 (CC3) in ear and the back skin of K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP at 6 weeks after oncogenic expression. Scale bar= 20μm. h. Quantification of CC3+ cells in WT cells and SmoM2 -clones at 3, 6, and 12 weeks after SmoM2 activation showing the increase of apoptosis in SmoM2-clones. Mean +- SEM. t-test. a, c, f, g. Scale bar, 20 μm. b, d, e, h. In parentheses, the number of cells.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Cell competition, proliferation and apoptosis surrounding SmoM2 clones in the back skin and the ear by whole mounts imaging.

a-c. Immunostaining on whole mount back skin and ear epidermis for Caspase cleaved 3 (CC3) (a), Keratin 10 (K10) (b) and EdU (c) in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP/Rosa-mT/mG 6 weeksafter SmoM2 activation. These data show WT apoptotic cells and basal cells expressing K10 at the edge of the SmoM2-clone in the back skin and not in the ear. In the ear and the back skin, Edu positive cells are more present at the periphery of the clone. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Single cell RNA-seq analysis of WT cells and SmoM2 epidermal cells and FACS sorting strategy.

a-b. FACS plots showing the gating strategy used to FACS-isolate the proportion of SmoM2-YFP in K14CreER/Rosa-SmoM2-YFP 6 weeks after oncogenic expression. c. Table showing the genes used to annotate the different clusters. d. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) graphic of the clustering analysis for scRNA-seq of the WT ear and back skin epidermis following data integration using Seurat.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Gene ontology of EHFP associated genes.

a. Gene ontology analysis on the genes up regulated in the ear 6W EHFP cluster. Statistics are based on the permutation method. b-g. UMAP plot of the ear and back sample coloured by the level of normalized gene expression values for genes regulating extracellular matrix organization/basal lamina (b), migration (c), regulation of cell proliferation (d), Wnt pathway (e), cell-cell adhesion (f), Hedgehog pathway (g).

Extended data Fig. 8 |. EHFP reprogramming and block of normal IFE differentiation in SmoM2 expressing cells in the ear and not in the back skin epidermis.