Abstract

Kinetochores couple chromosomes to the mitotic spindle to segregate the genome during cell division. An error correction mechanism drives the turnover of kinetochore – microtubule attachments until biorientation is achieved. The structural basis for how kinetochore-mediated chromosome segregation is accomplished and regulated remains an outstanding question. Here we describe the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the budding yeast outer kinetochore Ndc80 and Dam1 ring complexes assembled onto microtubules. Complex assembly occurs through multiple interfaces, and a staple within Dam1 aids ring assembly. Perturbation of key interfaces suppresses yeast viability. Force-rupture assays indicated this is a consequence of impaired kinetochore – microtubule attachment. The presence of error correction phosphorylation sites at Ndc80-Dam1 ring complex interfaces and the Dam1 staple explains how kinetochore – microtubule attachments are destabilized and reset.

Chromosome segregation is essential for the equal propagation of genetic information from parent to daughter cells, achieved through kinetochore-mediated coupling of sister chromatids to the mitotic spindle (1). Kinetochores are large macromolecular assemblies delineated into the inner – centromere binding- and outer -microtubule binding- complexes. The outer kinetochore couples the inner kinetochore CCAN (constitutive centromere associated network) to microtubules through three conserved complexes comprising the Knl1-MIND-Ndc80 (KMN) network (2). MIND interconnects CCAN with both the Ndc80 and Knl1 complexes (Ndc80c and Knl1c). Knl1c functions in the spindle-assembly checkpoint (SAC) (3), whereas Ndc80c, a heterotetramer of Ndc80, Nuf2, Spc24 and Spc25, is the major microtubule-binding component of KMN.

Outer kinetochore attachment to microtubules is augmented by additional essential microtubule-dependent kinetochore components. Many fungi, including S. cerevisiae, utilize the ten-subunit Dam1 complex (Dam1c), which self-assembles into a large ring around microtubules (4–9), whereas most metazoans contain the Ska complex (2). Although the Ndc80c and Dam1/Ska complexes bind microtubules independently, full function and interaction strength requires both modules (10–17). A central unresolved question is how these complexes coordinately bind and track the dynamic microtubule plus-end to ensure kinetochores do not detach from the spindle (10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19). As initial kinetochore-microtubule attachments are not necessarily bioriented, an error correction (EC) pathway, governed by antagonistic outer kinetochore phosphorylation by Aurora B kinase, ensures erroneous attachments are weakened and reset (20–24). As kinetochores come under tension, a feature of biorientation, the outer kinetochore is dephosphorylated, attachments are stabilized, and the SAC is inactivated to trigger anaphase (20, 21, 23, 25–31).

In yeast, centromere-localized Aurora B kinase phosphorylates Dam1c to suppress ring formation (15, 17, 32) and block its association with Ndc80c (10, 11, 28, 33), resulting in weakened end-on attachment (34, 35). Phosphorylation of a second set of targets within the unstructured N-terminus of Ndc80 (Ndc80N-Tail) also contributes to EC (14, 35, 36).

To obtain deeper mechanistic insight into Dam1c:Ndc80c (outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c) assembly on microtubules and its regulation by EC, we reconstituted and determined the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the budding yeast outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c:microtubule complex. We observe multiple contacts between Ndc80c and Dam1c. An N-terminal ‘staple’ region of the Dam1 subunit (Dam1Staple) binds the inter-protomer interface of the Dam1c ring. The presence of embedded EC phosphorylation sites within the Dam1Staple and Ndc80c-Dam1c interfaces indicates why EC would drive both Dam1c ring disassembly and destabilize kinetochore-microtubule attachments.

Results

Overall architecture of the yeast outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c bound to microtubules

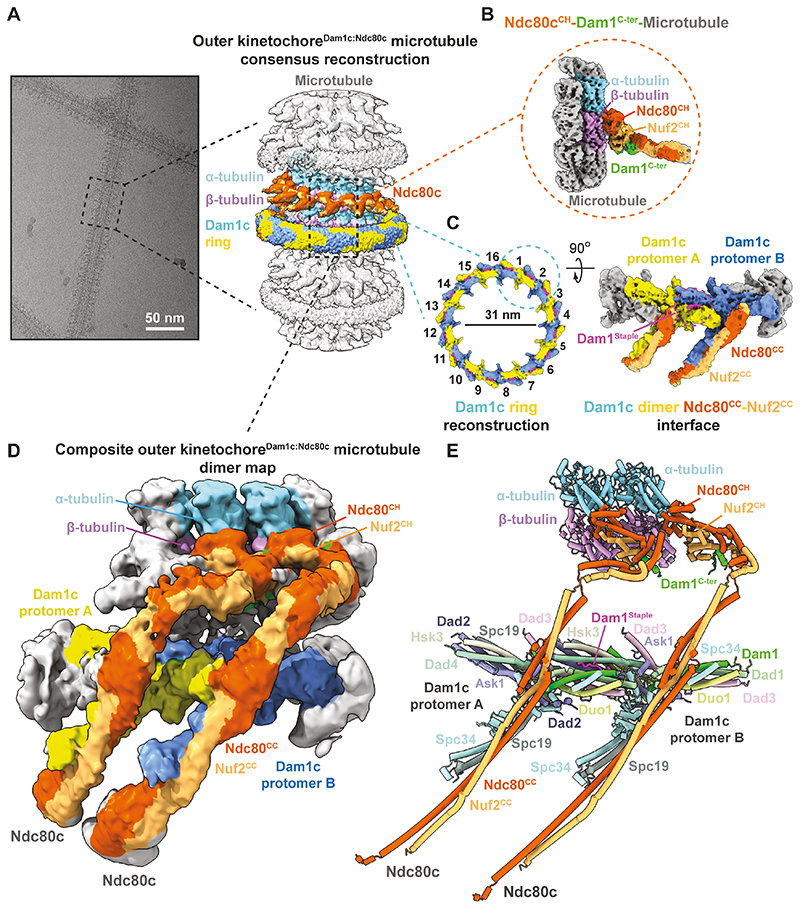

Outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c:microtubule complexes were assembled on cryo-EM grids by step-wise addition of taxol-stabilized microtubules, Ndc80c, and Dam1c (Fig. 1A, fig. S1A). Cryo-electron micrographs showed microtubules decorated with Dam1c rings (Dam1cRing) and Ndc80c fibrils (Fig. 1A). In the resultant consensus cryo-EM map, we observed a tandem organization of Ndc80c coiled-coil ‘spokes’ emerging from the microtubule surface between diffuse Dam1c rings (Fig. 1A, fig. S2A, B).

Figure 1. Yeast outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c complexes assemble through multiple interfaces to tandemly decorate the microtubule.

(A) Representative cryo-EM micrograph and corresponding consensus reconstruction of the outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c-microtubule complex. (B) Cryo-EM density map of the Ndc80cCH-Dam1C-ter-microtubule reconstruction. (C) Cryo-EM reconstruction of the 16-subunit Dam1cRing, and symmetry expanded Dam1c dimer Ndc80CC:Nuf2CC interface. (D) Composite cryo-EM map and corresponding atomic model (E) of a yeast outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c:microtubule dimer (defined as two copies of α/β tubulin:Dam1c:Ndc80c). Dam1cRing augments outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c tracking of both polymerizing and depolymerizing microtubule tips (11, 15, 16). The structure suggests Ndc80c is borne along as a ‘passenger’ on the outer surface of the ring, and need not necessarily bind the microtubule. In the latter, the complex is directly pushed by the ring.

The intermediate resolution of the cryo-EM map and the incompatible symmetries between the 16 protomers of the Dam1cRing and the 13 protofilament microtubule necessitated a divide and consolidate strategy for structure determination (Materials and Methods). This approach generated reconstructions of Ndc80c, and a dimer of Dam1c protomers at resolutions of 3.5 Å and 3.15 Å, respectively (Fig. 1B-D, figs S2B, C, S3A, S4, Table S1). Cryo-EM density was not visible for the Spc24:Spc25 subunits of Ndc80c. The coiled-coils of Ndc80c emanate from the calponin homology (CH) domains of the Ndc80 and Nuf2 subunits (Ndc80CH and Nuf2CH) at the surface of the microtubule to fold across the outer surface of the Dam1cRing. Here we observed prominent density corresponding to the coiled-coil central region of the Ndc80:Nuf2 subunits (Fig. 1C, D, fig. S2C). To obtain a complete model of the complex, we generated a composite map comprising two copies of the kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c protomer unit by rigid body fitting of the separate volumes into the consensus outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c:microtubule cryo-EM map (Fig. 1D). We then ‘folded’ the Ndc80:Nuf2 coils in the Dam1cProtomer component of the map until they were in proximity with the coils emanating from the Ndc80cCH domains, and melded the models to generate a structural model of the yeast kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c:microtubule complex (Fig. 1D, E, Table S3, Movie S1).

Structure and regulation of Dam1cRing assembly by a Dam1 staple peptide

Two- and three-dimensional classification showed that the Dam1cRing is tilted at variable angles relative to the microtubule (fig. S2B,C, top left panel), similar to Dam1cRing alone (8). Consistently, the tubulin surface beneath the ring is unoccupied except for diffuse density emerging from the α/β-tubulin C-terminal tails (fig. S3B), potentially representing the acidic E-hooks of α- and β-tubulin that enhance microtubule – Dam1c interactions (5, 8). The Dam1cRing – microtubule interface potentially involves flexible participants, as supported by biochemical and crosslinking mass spectrometry data (7, 11, 32, 37).

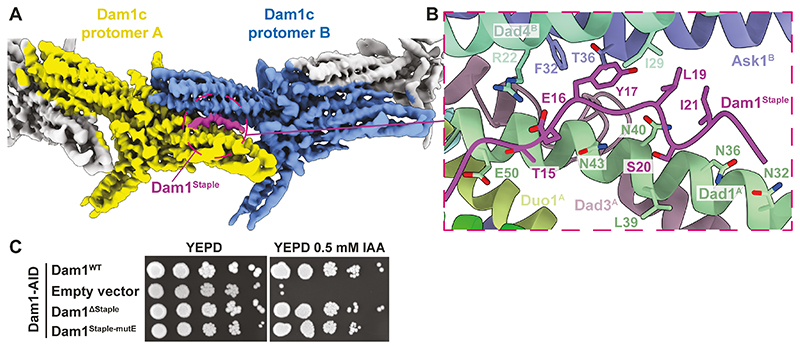

Dam1cRing assembly follows a shoulder-to-shoulder configuration (7, 38) (Figs 1C, E and 2A). The inter-protomer junctions are similar to the cryo-EM structure of a truncated C. thermophilum Dam1cRing (38). In this structure, the map resolution is limited to 4.5 Å. In contrast, here we find that in all ten subunits of S. cerevisiae Dam1c most side-chains within the globular core of the complex are resolved (fig. S3C). Additionally, we resolved a ‘staple’ density located at the inter-Dam1cProtomer interfaces that was truncated from C. thermophilum Dam1 (38) (Fig. 2A, B). The Dam1Staple comprises the N-terminus (residues 1-26) of the Dam1 subunit. The staple bridges the Dam1 and Dad1 subunits of Dam1cProtomerA with the Ask1 and Dad4 subunits of Dam1cProtomerB. Contact with Dam1cProtomerA is through hydrogen bonding between Dam1Staple residues Thr15 and Ser20, and Dad1A (Fig. 2B). Binding to Dam1cProtomerB is mediated by a salt bridge between Arg22 of Dad4B and Glu16 of Dam1Staple, as well as packing of Dam1Staple residues Tyr17, Leu19, and Ile21 against Ask1B and Dad4B (Fig. 2B). To test this interface in vivo, we performed rescue assays in an S. cerevisiae strain with an auxin-inducible degron (AID) tag inserted at the C-terminus of the endogenous copy of Dam1 (Table S2). We then integrated a series of Dam1 variants at the LEU locus. Cells grown on auxin with wild-type Dam1 as the ectopic copy rescued loss of endogenous Dam1, whereas cells carrying an empty vector failed to grow (Fig. 2C, fig. S1B, C). Cells carrying either a Dam1ΔStaple or Dam1Staple-mutE (Dam1 Tyr17, Leu19 and Ile21 to Glu) mutant were viable in the absence of wild-type Dam1 (Fig. 2C). In the cell, Dam1cRing assembly may be augmented by additional mechanisms that compensate for mutagenesis of the Dam1Staple (39, 40).

Figure 2. The Dam1 N-terminus forms a staple to stabilize Dam1cRing assembly that is negatively regulated by Aurora B kinase.

(A) Structure of the Dam1c protomer dimer interface shows a staple density (purple) between protomer A (yellow) and protomer B (blue). (B) Details of amino-acid contacts at the Dam1cProtomer dimer – Dam1Staple interface. Ser20 is an Aurora B kinase phosphorylation site and is oriented toward the Dad1 subunit of protomer A. Dam1Staple residues 13-23 are visible in cryo-EM density, whereas residues 1-12, and the connectivity to residue 55 of the remainder of Dam1 are not resolved. Mutation of Dad1 Glu50 to Asp impairs ring formation (41). (C) Dam1 auxin depletion assays. Cells grown on YEPD agar and YEPD agar containing 0.5 mM IAA are shown for each strain. Dam1ΔStaple: Dam1 mutant with residues 1-26 deleted, Dam1Staple-mutE: Dam1 mutant: Y17E/L19E/I21E.

Serine 20 of Dam1Staple, a target of Aurora B kinase (28), is buried at the interprotomer interface close to Leu39, Asn40 and Asn43 of the Dad1 subunit of Dam1cProtomerA (Fig. 2B).

Phosphorylation of Ser20 would cause steric hindrance and charge repulsion that would disrupt Dam1Staple binding. Phosphorylation of Ser20 destabilizes Dam1cRing in vitro (17, 32), and increases its diffusion on microtubules (12, 15). Similarly, mutations at the Dam1Staple-binding site (Fig. 2B) impair ring formation on microtubules (41). However, these mutations rescue loss of Aurora B kinase activity, presumably by driving increased kinetochore-microtubule attachment turnover (41, 42). Consistent with the notion that Dam1Staple regulates ring assembly, we found that the assembly of higher-order Dam1 complexes is substantially impaired when the staple is deleted (fig. S1F, S3D, E).

Structure of the Ndc80c:microtubule interface

The Ndc80c microtubule-binding domain forms a club-like structure comprising its two CH domains (Figs 1B, E and 3A). The underside of the club binds the α/β-tubulin interface along the lateral axis of the protofilament, whereas the coiled-coil shaft of Ndc80:Nuf2 projects outward orthogonal to the CH domains. In contrast to human and C. elegans, in which Ndc80c binds to every lateral α/β-tubulin interface (43, 44), the yeast complex binds only at the α/β site, a mode of binding that is independent of Dam1c (fig. S5A-C). No EM density is visible for the disordered Ndc80N-tail, and therefore we cannot account for how it contributes to kinetochore – microtubule attachments.

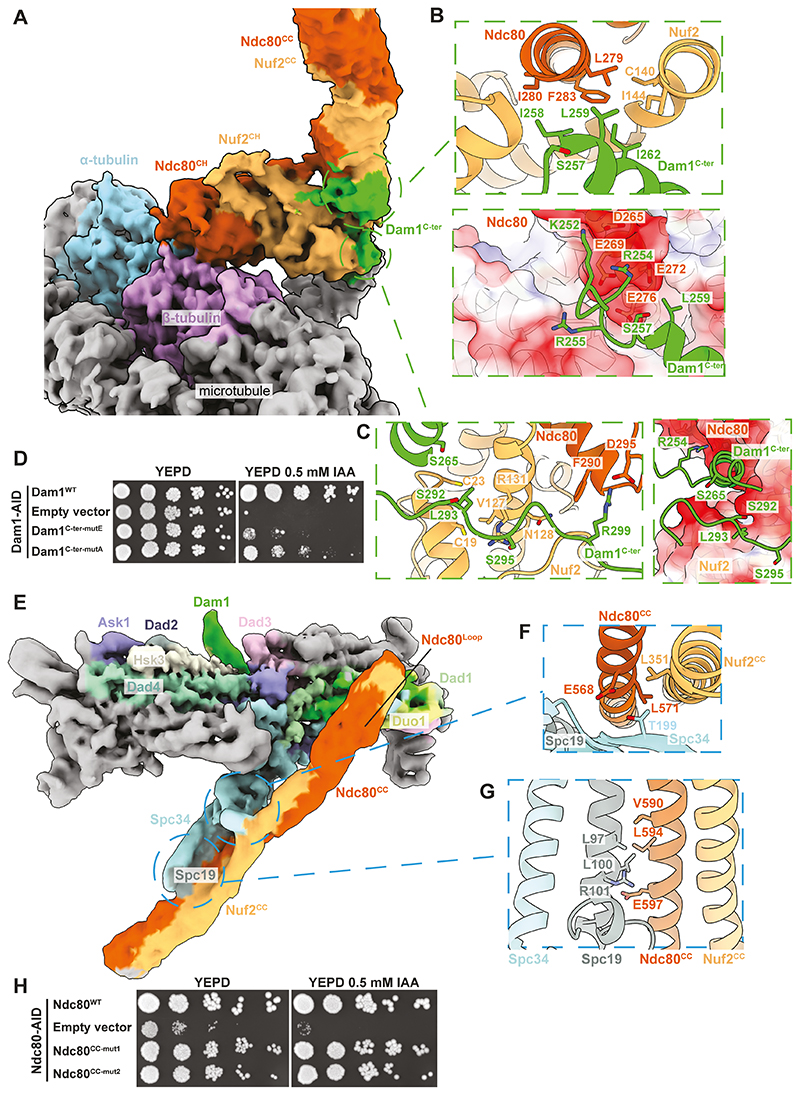

Figure 3. The Dam1 and Ndc80 complexes associate through a microtubule-proximal interface, and the outer surface of the Dam1cRing.

(A) Cryo-EM reconstruction of the Ndc80c-Dam1c-microtubule interface. Rigid-body placement of an AlphaFold2 prediction of the Ndc80cCH – Dam1C-ter interface into cryo-EM density shows: (B) The Dam1C-ter α-helix packs against a hydrophobic interface generated by the Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coil emerging from the Ndc80cCH domain (upper panel). Surface charges on Ndc80cCH and position of the Ser257 EC site on Dam1C-ter are shown in the lower panel. (C) The Dam1C-ter interface on the back-side of the Ndc80cCH (left panel), positions of residues targeted by EC and surface charges (right panel). Ser265 and Ser292 are oriented toward negative charges that would drive dissociation of Dam1C-ter from Ndc80CH during EC. (D) Dam1 rescue assays on auxin. Cells grown on YEPD agar and YEPD agar containing 0.5 mM IAA are shown for each strain. Dam1C-ter-mutE: Dam1 mutant: I258E/L259E/I262E, Dam1C-ter-mutA: Dam1 mutant: I258A/L259A/I262A. (E) Cryo-EM reconstruction of the Dam1c monomer-Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coil interface. The position of the Ndc80Loop is highlighted in fig. S5D. Rigid-body placement of an AlphaFold2 prediction of the Ndc80CC:Nuf2CC into cryo-EM density together with our experimental model of Dam1c shows the Ndc80CC:Nuf2CC binds Dam1c at two interfaces shown as insets: (F) Ndc80CC:Nuf2CC docks against a β-strand on Spc34. The EC target site Thr199 is oriented toward Ndc80c. (G) The Spc19:Spc34 coiled coils pack against Ndc80CC:Nuf2CC via residues in Spc19 and Ndc80. (H) Ndc80 auxin depletion assays. Cells grown on YEPD agar and YEPD agar containing 0.5 mM IAA are shown for each strain. Ndc80cc-mut1: Ndc80 coiled-coil mutant1: E568A/V590A/L594A/E597A, Ndc80cc-mut2: Ndc80 coiled-coil mutant2: E568R/V590W/L594E/E597R.

Binding of the Dam1 C-terminus to Ndc80c is essential and is regulated by error correction

We observed additional cryo-EM density at the base of the Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coils emerging from Ndc80cCH (Figs 1B and 3A). Although the additional density was not sufficiently well resolved to model de novo, crosslinking mass-spectrometry and mutagenesis experiments suggest this region of Ndc80c (Fig. S5A) interacts with Dam1c (13) through the Dam1 C-terminus (11, 14). We used AlphaFold2 to predict the structure of Ndc80:Nuf2 together with residues 201 to 343 of Dam1. The resulting prediction was a tripartite complex consistent with a subsequently-solved crystal structure (45). Two short segments from the C-terminus of Dam1 (Dam1C-ter) dock onto the Ndc80cCH domains. One of these (residues 251 to 272) nestles in an amphipathic pocket at the base of the Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coils (Fig. 3B, fig. S5D), and another (residues 287 to 301) snakes around the back-face of Ndc80cCH (Fig. 3C, fig. S5E). Dam1 residues Ile258, Leu259, Ile262 pack against Ndc80cCH (Fig. 3B, upper panel). We introduced Dam1 mutants bearing triple alanine or glutamate substitution of these residues as ectopic copies into our Dam1-AID strain (Dam1C-ter-mutA and Dam1C-ter-mutE, respectively) (figs S1B, C, Table S2). Upon depletion of endogenous Dam1, growth was severely impaired (Fig. 3D). Therefore, the integrity of the Dam1C-ter:Ndc80cCH interface is essential for proper kinetochore function and yeast cell viability.

During EC, residues at the Dam1C-ter-Ndc80cCH interface are phosphorylated by Aurora B kinase, specifically Dam1 Ser257, Ser265, and Ser292 (Fig. 3B-lower panel, 3C-right panel) (27, 28). Phosphorylation of these residues in vitro results in decreased strength and lifetime of outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c binding to microtubules (10, 11), and phospho-mimetics suppress impaired Aurora B kinase activity in vivo (28). Ser257 is oriented towards negatively charged residues on an α-helix of Ndc80c (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Phosphorylation of Ser257 would be incompatible with binding of Dam1C-ter to Ndc80cCH. Similarly, phosphorylated Ser265 and Ser292 would also be oriented toward negatively charged surfaces on Ndc80c (Fig. 3C, right panel). EC phosphorylation would thus weaken co-assembly of the outer kinetochore.

The central coiled-coil domain of Ndc80:Nuf2 folds across the outer rim of Dam1c

The Ndc80:Nuf2 central coiled-coil docks near the Dam1cProtomer interface against a pair of β-strands from Spc34 that contain the EC target residue Thr199 (Fig. 3E, F, fig. SF left panel), and runs parallel with the C-terminal coiled-coils of Spc34 and Spc19 (Fig. 3E, G, fig. SF right panel). Our structure is consistent with previous cross-linking mass spectrometry and insertion mutagenesis experiments indicating that the central segment of the Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coils proximal to the conserved Ndc80 loop directly interacts with the Spc34:Spc19 C-termini (11, 13). Following focused classification and flexible refinement, a distinct interruption in the coiled-coil became apparent (Fig. 3E). This interruption corresponds to the Ndc80 loop (Ndc80Loop), enabling us to infer the amino-acid register of an AlphaFold2 prediction comprising the remaining coiled-coil (fig. S5G). We mapped sequence conservation onto the structure, and observed that interfacial residues are well-conserved, whereas outward-facing residues are not (fig. S5H).

To test the impact of mutating this interface in vivo, we generated a yeast strain in which the endogenous copy of Ndc80 bore a C-terminal AID tag (figs S1D, E, Table S2). Mutation of a series of four conserved interfacial residues on Ndc80 (Ndc80CC-mut1&2) did not impair viability (Fig. 3H), consistent with in vitro observations that disruption of this interface by phosphorylation of Spc34 at Thr199 exerts a minor reduction in outer kinetochore – microtubule rupture forces (10). Indeed, our auxin-depletion experiments that disrupted the Dam1C-ter-Ndc80cCH interface (Fig. 3D) showed that the Ndc80c coiled-coil:Spc34 interface is not sufficient for proper outer kinetochore function (13, 14).

Disruption of outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c interfaces weakens microtubule attachments in vitro

The full load-bearing potential of the outer kinetochore and its ability to track dynamic microtubule ends is dependent on co-assembly of Ndc80c and Dam1c (10–17, 33). Disruption of coordinated binding to the microtubule is a central proposed mechanism for how error correction regulates attachments (10–13, 15, 16, 33–35, 46).

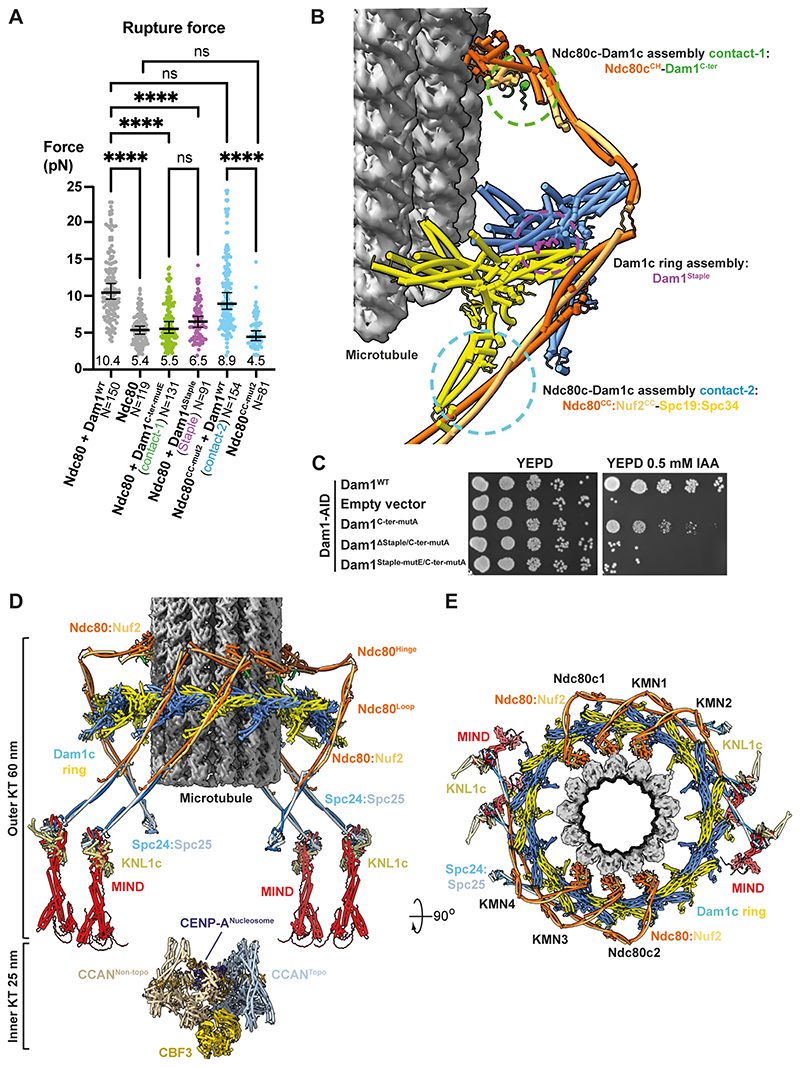

In vitro optical trap experiments in which purified yeast kinetochores and reconstituted kinetochore – microtubule attachments are challenged have determined rupture forces of ~5-10 pN (10, 12, 15, 47). To test the contribution each of the interfaces in our structure makes to the ability of the outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c complex to withstand force, we purified a series of Dam1c and Ndc80c variants (figs S1F-H) and performed force-rupture assays (Fig. 4A, B, fig. S6) (10, 48). We determined a median rupture force of 5.4 pN for Ndc80c alone that increased to 10.4 pN in the presence of Dam1c (Fig. 4A), confirming that the kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c complex withstands greater forces than does isolated Ndc80c (10, 12, 15). Mutation of the Dam1C-ter (Ndc80cCH contact-1) and Dam1Staple (ring assembly contact) substantially lowered the rupture forces to 5.5 pN and 6.5 pN, respectively. The Dam1C-ter mutant was not impaired in self-assembly (fig. S1I), consistent with (5), thus it presumably acts by disrupting binding to Ndc80cCH. In contrast, the Ndc80CC-mut2 (Spc19:Spc34-Ndc80:Nuf2 coiled-coil contact-2) essentially had no effect on rupture strength when combined with Dam1c (Fig. 4A, B). Hence, mutation of outer kinetochore assembly through the Dam1C-ter-Ndc80cCH interface, or disruption of Dam1cRing formation independently weakened microtubule binding. Our structural and biochemical results suggested that ablation of these functional elements of Dam1, targeted for inhibition by EC, would generate complexes that are unable to assemble rings, contact Ndc80c, or bear load (Fig. 4A, B). To test whether concurrent disruption of these elements of Dam1c impacted kinetochore function in vivo, we combined Dam1Staple and Dam1C-ter mutants in our Dam1-AID strain (Table S2). Mutagenesis of key Dam1C-ter residues to alanine (Dam1C-ter-mutA) permitted weak growth that was completely abolished when the Dam1Staple was deleted or mutated (Dam1ΔStaple and Dam1Staple-mutE, respectively) (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. A structural model for mitotic error correction and chromosome segregation by the yeast kinetochore.

(A) Force-rupture measurements of outer kinetochore – microtubule complexes. Each circle represents a single rupture event (the maximum trap force before rupturing). The total number of measurements for each condition are indicated by N values. The black bar represents the median rupture forces, with 95% CIs. Numbers below the black bar indicates median values. A Kruskal-Wallis test to determine which medians are significantly different was performed, ****: p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Mutants of Dam1 and Ndc80 are defined in Figs 2C, 3D, H. (B) Structure of an outer kinetochoreDam1:Ndc80c dimer bound to the microtubule. Outer kinetochore and Dam1cRing assembly contacts that are targeted by error correction are highlighted. (C) Dam1 auxin depletion assays. Cells grown on YEPD agar and YEPD agar containing 0.5 mM IAA are shown for each strain. Dam1C-ter-mutA: Dam1 mutant: I258A/L259A/I262A, Dam1ΔStaple/C-ter-mut-A: Dam1 mutant with residues 1-26 deleted/I258A/L259A/I262A. Dam1Staple-mutE/C-ter-mut-A: Dam1 mutant: Y17E/L19E/I21E/I258A/L259A/I262A. Simultaneous mutation of the Dam1 Staple (Dam1ΔStaple and Dam1Staple-mutE) and Dam1 C-terminus (Dam1C-ter-mutA) results in lethality. (D) Structural model of the complete yeast holo-kinetochore bound to a microtubule. Shown are the microtubule, Dam1cRing, four KMN network complexes, two Ndc80 complexes and the CCAN inner kinetochore complex (comprising two CCAN promoters, CBF1, CBF3 and CENP-A nucleosome) (49). The flexible linkers connecting CCAN to the KMN network and Ndc80c are not shown. For clarity, shown are four of six possible KMN network complexes. The view is in plane with the microtubule helical axis. In this configuration, the end-to-end dimension of the kinetochore is ~85 nm, a value consistent with the relative location and separation of kinetochore components measured in metaphase yeast cells using fluorescence localization microscopy (52, 62). Shortening of the kinetochore as tension is reduced (52) could be facilitated through the flexible linkers connecting the inner kinetochore with MIND and Ndc80 complexes. (E) Top view viewed from the microtubule minus-end.

Consistent with EC driving attachment turnover by breaking outer kinetochore assembly, our force-rupture data correspond well to measurements of in vitro reconstituted Dam1c phosphorylated at the respective interfaces by Aurora B (10, 12, 15), as well as for complexes containing a phospho-mimetic Dam1 S20D mutation (12, 34). Finally, the severity of the force-rupture phenotypes correlated closely with the degree of viability defect caused by the corresponding mutants in cells. Mutagenesis of the interfaces identified in our structures likely caused reduced fitness in vivo because these cells form defective kinetochore – microtubule attachments that cannot support normal chromosome segregation.

Discussion

We consolidated previous structural findings and in vivo measurements of relative kinetochore subunit positions and stoichiometry with our outer kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c structure to generate a model for a yeast holo-kinetochore bound to a microtubule (Fig. 4D, E). The inner kinetochore generates a total of eight Ndc80c linkages to the microtubule (49). These Ndc80c molecules are readily accommodated by the 16 binding sites of Dam1cRing, which is recruited through Ndc80c in a microtubule-dependent fashion (50). The flexible hinge between Ndc80cCH and Ndc80Loop (51) permits Ndc80 complexes to fold as hooks across the Dam1cRing, explaining how the coiled-coils of Ndc80:Nuf2 dock in a parallel configuration across Spc19:Spc34 despite adherence of the Ndc80cCH to the pseudo-helical symmetry of the microtubule (52, 53).

In budding yeast several models for how EC detects attachment errors have gained prominence (54). Yeast error correction is trifurcated between disruption of Dam1cRing assembly, disassembly of Dam1c – Ndc80c interfaces and phosphorylation of Ndc80N-Tail (10–12, 14–16, 27, 28, 33). Collectively these inhibitory activities dismantle the Dam1cRing and dissolve kinetochore – microtubule attachments. We found that kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c assembly is mediated through multiple interfaces that are antagonized by EC, whereas Dam1cRing assembly is facilitated by a ‘staple’ that contains an embedded EC target. In contrast to human Ndc80c, we did not observe inter-Ndc80c contacts, nor can we account for the flexible Ndc80N-Tail (43, 55). The Dam1, Ask1 and Spc34 subunits of Dam1c form a network of interactions between the Dam1cRing and Ndc80c that promote cooperative outer kinetochore assembly on the microtubule and are disrupted by EC (10, 11, 13, 14). The region implicated in Ask1-Ndc80c binding is likely situated at the Ndc80cHinge and is too mobile to resolve in our cryo-EM maps (11). Our molecular models therefore account for two EC-sensitive contacts: the Dam1C-ter-Ndc80cCH and the Spc34-Ndc80:Nuf2CC interfaces. At both, residues phosphorylated in EC would cause electrostatic and steric repulsion (Figs 2B, 3B, C), explaining how EC-mediated phosphorylation suppresses kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c assembly.

A fundamental paradox at the heart of EC is how initially weak, low-tension kinetochore attachments can escape re-phosphorylation during attachment reset to form new connections to the microtubule. Ndc80c retains a degree of microtubule affinity even when Ndc80N-tail is either deleted (14, 56) or incorporates EC phosphosites (33). However, it has remained unclear how Dam1c is reincorporated into the kinetochore if the Ndc80c – Dam1c interfaces are disrupted during EC. The major targets of phosphorylation that govern kinetochoreDam1c:Ndc80c assembly are within Dam1c (10, 11, 27, 28). Achieving full attachment strength would thus require dephosphorylation and/or replacement of Dam1c. We propose that simple replacement of Dam1c by EC-mediated turnover would resolve the EC-reset paradox. Following EC, kinetochores remain attached to the lateral face of the microtubule (35, 57), and phosphorylated Dam1c diffuses away. However, Dam1c not associated with the kinetochore remains unphosphorylated (29) and is transported to the kinetochore by tracking microtubule plus-ends. Unphosphorylated Dam1c then associates with Ndc80c to facilitate conversion from lateral to end-on attachment (33, 35, 57). This Ndc80c:Dam1c assembly could drive displacement of the outer kinetochore, rendering it resistant to the centromere-localized Aurora B kinase (58, 59).

Two models posit how the mechanical energy of microtubule depolymerization is exploited by the kinetochore to segregate chromosomes: the conformational wave, and biased diffusion. In the former, the curling protofilaments lever the kinetochore toward the spindle poles (60). In the biased diffusion model, an array of kinetochore attachments detaches and rebinds the tubulin lattice as it depolymerizes (61). Dam1c augments outer kinetochore tracking of both polymerizing and depolymerizing microtubule tips (11, 15, 16). Our findings support a model for kinetochore-mediated chromosome segregation wherein Dam1cRing acts as a topological sleeve that is pushed along by the curved protofilaments of the depolymerizing microtubule, driving Ndc80c translocation through steric occlusion. By generating multivalency through coordinating multiple Ndc80 complexes, Dam1cRing also enables biased diffusion. Association of outer kinetochore components through flexible peptidic interfaces mediates a tethering mechanism which prevents Ndc80c detaching from the microtubule when displaced by the advancing Dam1cRing, thus pulling chromatids toward the spindle poles (6, 14–16, 33, 35).

Supplementary Material

One-Sentence Summary.

Structural mechanism for how phosphorylation regulates kinetochore-microtubule attachments in mitotic error correction.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Diamond Light Source for access and support of the cryo-EM facilities at the UK's national Electron Bio-imaging Centre (eBIC) [under proposal EM BI31336], funded by the Wellcome Trust, MRC and BBRSC. We are grateful to the LMB EM facility for help with the EM data collection, to J. Grimmett, T. Darling and I. Clayson for high-performance computing, and to J. Shi for help with insect cell expression, Sami Chaaban for advice on microtubule cryo-EM and Vicente Jose Planelles Herrero for help with the optical tweezer study. We thank Stanislau Yatskevich for discussions and Noah Turner for comments on the manuscript.

Funding

UKRI/Medical Research Council MC_UP_1201/6 (DB), Cancer Research UK C576/A14109 (DB).

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization: D.B. and K.W.M., Methodology: K.W.M., C.B., T.D., J.Y., Z.Z., A.B., D.B., Investigation: K.W.M., C.B., T.D., J.Y., Z.Z., Visualization: K.W.M., Funding acquisition: D.B., Project administration: D.B., K.W.M., Writing – original draft: K.W.M., Writing – review & editing: K.W.M., D.B., C.B., T.D., J.Y., Z.Z., A.B.

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability

Atomic coordinates and cryo-EM density maps (also listed in Table S1) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (https://ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/): Ndc80cCH-α/β-tubulin-Dam1C-ter (PDB: 8QAU; map: EMD-18304), Dam1c protomer dimer-Ndc80CC-Nuf2CC (PDB: 8Q84; map: EMD-18246), Dam1c protomer monomer-Ndc80CC-Nuf2CC (PDB: 8Q85; map: EMD-18247), Ndc80c – microtubule (map: EMD-18485). All other data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Materials.

References

- 1.McAinsh AD, Marston AL. The Four Causes: The Functional Architecture of Centromeres and Kinetochores. Annu Rev Genet. 2022;56:279–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-072820-034559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Hooff JJ, Tromer E, van Wijk LM, Snel B, Kops GJ. Evolutionary dynamics of the kinetochore network in eukaryotes as revealed by comparative genomics. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1559–1571. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer ES. Kinetochore-catalyzed MCC formation: A structural perspective. IUBMB Life. 2023;75:289–310. doi: 10.1002/iub.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda JJ, De Wulf P, Sorger PK, Harrison SC. The yeast DASH complex forms closed rings on microtubules. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:138–143. doi: 10.1038/nsmb896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westermann S, Avila-Sakar A, Wang HW, Niederstrasser H, Wong J, Drubin DG, Nogales E, Barnes G. Formation of a dynamic kinetochore- microtubule interface through assembly of the Dam1 ring complex. Mol Cell. 2005;17:277–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westermann S, Wang HW, Avila-Sakar A, Drubin DG, Nogales E, Barnes G. The Dam1 kinetochore ring complex moves processively on depolymerizing microtubule ends. Nature. 2006;440:565–569. doi: 10.1038/nature04409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HW, Ramey VH, Westermann S, Leschziner AE, Welburn JP, Nakajima Y, Drubin DG, Barnes G, Nogales E. Architecture of the Dam1 kinetochore ring complex and implications for microtubule-driven assembly and force-coupling mechanisms. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramey VH, Wang HW, Nakajima Y, Wong A, Liu J, Drubin D, Barnes G, Nogales E. The Dam1 ring binds to the E-hook of tubulin and diffuses along the microtubule. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:457–466. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-10-0841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng CT, Deng L, Chen C, Lim HH, Shi J, Surana U, Gan L. Electron cryotomography analysis of Dam1C/DASH at the kinetochore-spindle interface in situ. J Cell Biol. 2019;218:455–473. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201809088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores RL, Peterson ZE, Zelter A, Riffle M, Asbury CL, Davis TN. Three interacting regions of the Ndc80 and Dam1 complexes support microtubule tip-coupling under load. J Cell Biol. 2022;221 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202107016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JO, Zelter A, Umbreit NT, Bollozos A, Riffle M, Johnson R, MacCoss MJ, Asbury CL, Davis TN. The Ndc80 complex bridges two Dam1 complex rings. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.21069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umbreit NT, Miller MP, Tien JF, Ortola JC, Gui L, Lee KK, Biggins S, Asbury CL, Davis TN. Kinetochores require oligomerization of Dam1 complex to maintain microtubule attachments against tension and promote biorientation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4951. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tien JF, Fong KK, Umbreit NT, Payen C, Zelter A, Asbury CL, Dunham MJ, Davis TN. Coupling unbiased mutagenesis to high-throughput DNA sequencing uncovers functional domains in the Ndc80 kinetochore protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;195:159–170. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampert F, Mieck C, Alushin GM, Nogales E, Westermann S. Molecular requirements for the formation of a kinetochore-microtubule interface by Dam1 and Ndc80 complexes. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:21–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tien JF, Umbreit NT, Gestaut DR, Franck AD, Cooper J, Wordeman L, Gonen T, Asbury CL, Davis TN. Cooperation of the Dam1 and Ndc80 kinetochore complexes enhances microtubule coupling and is regulated by aurora B. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:713–723. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampert F, Hornung P, Westermann S. The Dam1 complex confers microtubule plus end-tracking activity to the Ndc80 kinetochore complex. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:641–649. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gestaut DR, Graczyk B, Cooper J, Widlund PO, Zelter A, Wordeman L, Asbury CL, Davis TN. Phosphoregulation and depolymerization-driven movement of the Dam1 complex do not require ring formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:407–414. doi: 10.1038/ncb1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huis In ‘t Veld PJ, Volkov VA, Stender ID, Musacchio A, Dogterom M. Molecular determinants of the Ska-Ndc80 interaction and their influence on microtubule tracking and force-coupling. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.49539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helgeson LA, Zelter A, Riffle M, MacCoss MJ, Asbury CL, Davis TN. Human Ska complex and Ndc80 complex interact to form a load-bearing assembly that strengthens kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:2740–2745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718553115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggins S, Severin FF, Bhalla N, Sassoon I, Hyman AA, Murray AW. The conserved protein kinase Ipl1 regulates microtubule binding to kinetochores in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 1999;13:532–544. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka TU, Rachidi N, Janke C, Pereira G, Galova M, Schiebel E, Stark MJ, Nasmyth K. Evidence that the Ipl1-Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell. 2002;108:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cimini D, Moree B, Canman JC, Salmon ED. Merotelic kinetochore orientation occurs frequently during early mitosis in mammalian tissue cells and error correction is achieved by two different mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4213–4225. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauf S, Cole RW, LaTerra S, Zimmer C, Schnapp G, Walter R, Heckel A, van Meel J, Rieder CL, Peters JM. The small molecule Hesperadin reveals a role for Aurora B in correcting kinetochore-microtubule attachment and in maintaining the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:281–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biggins S, Murray AW. The budding yeast protein kinase Ipl1/Aurora allows the absence of tension to activate the spindle checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3118–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.934801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLuca KF, Lens SM, DeLuca JG. Temporal changes in Hec1 phosphorylation control kinetochore-microtubule attachment stability during mitosis. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:622–634. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cimini D, Wan X, Hirel CB, Salmon ED. Aurora kinase promotes turnover of kinetochore microtubules to reduce chromosome segregation errors. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1711–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shang C, Hazbun TR, Cheeseman IM, Aranda J, Fields S, Drubin DG, Barnes G. Kinetochore protein interactions and their regulation by the Aurora kinase Ipl1p. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3342–3355. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-11-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheeseman IM, Anderson S, Jwa M, Green EM, Kang J, Yates JR, 3rd, Chan CS, Drubin DG, Barnes G. Phospho-regulation of kinetochore-microtubule attachments by the Aurora kinase Ipl1p. Cell. 2002;111:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keating P, Rachidi N, Tanaka TU, Stark MJ. Ipl1-dependent phosphorylation of Dam1 is reduced by tension applied on kinetochores. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4375–4382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.055566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewar H, Tanaka K, Nasmyth K, Tanaka TU. Tension between two kinetochores suffices for their bi-orientation on the mitotic spindle. Nature. 2004;428:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature02328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukherjee S, Sandri BJ, Tank D, McClellan M, Harasymiw LA, Yang Q, Parker LL, Gardner MK. A Gradient in Metaphase Tension Leads to a Scaled Cellular Response in Mitosis. Dev Cell. 2019;49:63–76.:e10. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zelter A, Bonomi M, Kim JO, Umbreit NT, Hoopmann MR, Johnson R, Riffle M, Jaschob D, MacCoss MJ, Moritz RL, Davis TN. The molecular architecture of the Dam1 kinetochore complex is defined by cross-linking based structural modelling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8673. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doodhi H, Kasciukovic T, Clayton L, Tanaka TU. Aurora B switches relative strength of kinetochore-microtubule attachment modes for error correction. J Cell Biol. 2021;220 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarangapani KK, Akiyoshi B, Duggan NM, Biggins S, Asbury CL. Phosphoregulation promotes release of kinetochores from dynamic microtubules via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7282–7287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220700110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalantzaki M, Kitamura E, Zhang T, Mino A, Novak B, Tanaka TU. Kinetochore-microtubule error correction is driven by differentially regulated interaction modes. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:530. doi: 10.1038/ncb3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyoshi B, Nelson CR, Ranish JA, Biggins S. Analysis of Ipl1-mediated phosphorylation of the Ndc80 kinetochore protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2009;183:1591–1595. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legal T, Zou J, Sochaj A, Rappsilber J, Welburn JP. Molecular architecture of the Dam1 complex-microtubule interaction. Open Biol. 2016;6 doi: 10.1098/rsob.150237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenni S, Harrison SC. Structure of the DASH/Dam1 complex shows its role at the yeast kinetochore-microtubule interface. Science. 2018;360:552–558. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutierrez A, Kim JO, Umbreit NT, Asbury CL, Davis TN, Miller MP, Biggins S. Cdk1 Phosphorylation of the Dam1 Complex Strengthens Kinetochore-Microtubule Attachments. Curr Biol. 2020;30:4491–4499.:e4495. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dudziak A, Engelhard L, Bourque C, Klink BU, Rombaut P, Kornakov N, Janen K, Herzog F, Gatsogiannis C, Westermann S. Phospho-regulated Bim1/EB1 interactions trigger Dam1c ring assembly at the budding yeast outer kinetochore. EMBO J. 2021;40:e108004. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021108004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haase MAB, Olafsson G, Flores RL, Boakye-Ansah E, Zelter A, Dickinson MS, Lazar-Stefanita L, Truong DM, Asbury CL, Davis TN, Boeke JD. DASH/Dam1 complex mutants stabilize ploidy in histone-humanized yeast by weakening kinetochore-microtubule attachments. EMBO J. 2023;42:e112600. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022112600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarke MN, Marsoner T, Adell MAY, Ravichandran MC, Campbell CS. Adaptation to high rates of chromosomal instability and aneuploidy through multiple pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 2023;42:e111500. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022111500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alushin GM, Ramey VH, Pasqualato S, Ball DA, Grigorieff N, Musacchio A, Nogales E. The Ndc80 kinetochore complex forms oligomeric arrays along microtubules. Nature. 2010;467:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature09423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson-Kubalek EM, Cheeseman IM, Milligan RA. Structural comparison of the Caenorhabditis elegans and human Ndc80 complexes bound to microtubules reveals distinct binding behavior. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:1197–1203. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-12-0858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahm JA, Jenni S, Harrison SC. Structure of the Ndc80 complex and its interactions at the yeast kinetochore-microtubule interface. Open Biol. 2023;13:220378. doi: 10.1098/rsob.220378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarangapani KK, Koch LB, Nelson CR, Asbury CL, Biggins S. Kinetochore-bound Mps1 regulates kinetochore-microtubule attachments via Ndc80 phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 2021;220 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202106130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akiyoshi B, Sarangapani KK, Powers AF, Nelson CR, Reichow SL, Arellano-Santoyo H, Gonen T, Ranish JA, Asbury CL, Biggins S. Tension directly stabilizes reconstituted kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nature. 2010;468:576–579. doi: 10.1038/nature09594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asbury CL, Gestaut DR, Powers AF, Franck AD, Davis TN. The Dam1 kinetochore complex harnesses microtubule dynamics to produce force and movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9873–9878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dendooven T, Zhang Z, Yang J, McLaughlin SH, Schwab J, Scheres SHW, Yatskevich S, Barford D. Cryo-EM structure of the complete inner kinetochore of the budding yeast point centromere. Science Advances. 2023 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adg7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Bachant J, Alcasabas AA, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ. The mitotic spindle is required for loading of the DASH complex onto the kinetochore. Genes Dev. 2002;16:183–197. doi: 10.1101/gad.959402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang HW, Long S, Ciferri C, Westermann S, Drubin D, Barnes G, Nogales E. Architecture and flexibility of the yeast Ndc80 kinetochore complex. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aravamudhan P, Felzer-Kim I, Gurunathan K, Joglekar AP. Assembling the protein architecture of the budding yeast kinetochore-microtubule attachment using FRET. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kukreja AA, Kavuri S, Joglekar AP. Microtubule Attachment and Centromeric Tension Shape the Protein Architecture of the Human Kinetochore. Curr Biol. 2020;30:4869–4881.:e4865. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Broad AJ, DeLuca JG. The right place at the right time: Aurora B kinase localization to centromeres and kinetochores. Essays Biochem. 2020;64:299–311. doi: 10.1042/EBC20190081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alushin GM, Musinipally V, Matson D, Tooley J, Stukenberg PT, Nogales E. Multimodal microtubule binding by the Ndc80 kinetochore complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1161–1167. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei RR, Al-Bassam J, Harrison SC. The Ndc80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:54–59. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka K, Kitamura E, Kitamura Y, Tanaka TU. Molecular mechanisms of microtubule-dependent kinetochore transport toward spindle poles. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:269–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia-Rodriguez LJ, Kasciukovic T, Denninger V, Tanaka TU. Aurora B-INCENP Localization at Centromeres/Inner Kinetochores Is Required for Chromosome Bi-orientation in Budding Yeast. Curr Biol. 2019;29:1536–1544.:e1534. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fischbock-Halwachs J, Singh S, Potocnjak M, Hagemann G, Solis-Mezarino V, Woike S, Ghodgaonkar-Steger M, Weissmann F, Gallego LD, Rojas J, Andreani J, et al. The COMA complex interacts with Cse4 and positions Sli15/Ipl1 at the budding yeast inner kinetochore. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.42879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koshland DE, Mitchison TJ, Kirschner MW. Polewards chromosome movement driven by microtubule depolymerization in vitro. Nature. 1988;331:499–504. doi: 10.1038/331499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill TL. Theoretical problems related to the attachment of microtubules to kinetochores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4404–4408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cieslinski K, Wu YL, Nechyporenko L, Horner SJ, Conti D, Skruzny M, Ries J. Nanoscale structural organization and stoichiometry of the budding yeast kinetochore. J Cell Biol. 2023;222 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202209094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Z, Yang J, Barford D. Recombinant expression and reconstitution of multiprotein complexes by the USER cloning method in the insect cell-baculovirus expression system. Methods. 2016;95:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Russo CJ, Scotcher S, Kyte M. A precision cryostat design for manual and semi-automated cryo-plunge instruments. Rev Sci Instrum. 2016;87:114302. doi: 10.1063/1.4967864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kimanius D, Dong L, Sharov G, Nakane T, Scheres SHW. New tools for automated cryo-EM single-particle analysis in RELION-4.0. Biochem J. 2021;478:4169–4185. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache JP, Verba KA, Cheng Y, Agard DA. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner T, Merino F, Stabrin M, Moriya T, Antoni C, Apelbaum A, Hagel P, Sitsel O, Raisch T, Prumbaum D, Quentin D, et al. SPHIRE-crYOLO is a fast and accurate fully automated particle picker for cryo-EM. Commun Biol. 2019;2:218. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cook AD, Manka SW, Wang S, Moores CA, Atherton J. A microtubule RELION-based pipeline for cryo-EM image processing. J Struct Biol. 2020;209:107402. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Courtine G, Sofroniew MV. Spinal cord repair: advances in biology and technology. Nat Med. 2019;25:898–908. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Punjani A, Fleet DJ. 3D variability analysis: Resolving continuous flexibility and discrete heterogeneity from single particle cryo-EM. J Struct Biol. 2021;213:107702. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Punjani A, Fleet DJ. 3DFlex: determining structure and motion of flexible proteins from cryo-EM. Nat Methods. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41592-023-01853-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lacey SE, He S, Scheres SH, Carter AP. Cryo-EM of dynein microtubule-binding domains shows how an axonemal dynein distorts the microtubule. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.47145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Croll TI. ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2018;74:519–530. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, Ferrin TE. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018;27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Zidek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tanaka S, Miyazawa-Onami M, Iida T, Araki H. iAID: an improved auxin-inducible degron system for the construction of a ‘tight’ conditional mutant in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2015;32:567–581. doi: 10.1002/yea.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Planelles-Herrero VJ, Bittleston A, Seum C, Daeden A, Gaitan MG, Derivery E. Elongator stabilizes microtubules to control central spindle asymmetry and polarized trafficking of cell fate determinants. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:1606–1616. doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-01020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nishimura K, Kanemaki MT. Rapid Depletion of Budding Yeast Proteins via the Fusion of an Auxin-Inducible Degron (AID) Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2014;64:20 29 21–16. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2009s64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and cryo-EM density maps (also listed in Table S1) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (https://ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/): Ndc80cCH-α/β-tubulin-Dam1C-ter (PDB: 8QAU; map: EMD-18304), Dam1c protomer dimer-Ndc80CC-Nuf2CC (PDB: 8Q84; map: EMD-18246), Dam1c protomer monomer-Ndc80CC-Nuf2CC (PDB: 8Q85; map: EMD-18247), Ndc80c – microtubule (map: EMD-18485). All other data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Materials.