Summary

Most eukaryotes respire oxygen, using it to generate biomass and energy. However, a few organisms have lost the capacity to respire. Understanding how they manage biomass and energy production may illuminate the critical points at which respiration feeds into central carbon metabolism and explain possible routes to its optimization. Here, we use two related fission yeasts, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Schizosaccharomyces japonicus, as a comparative model system. We show that although S. japonicus does not respire oxygen, unlike S. pombe, it is capable of efficient NADH oxidation, amino acid synthesis, and ATP generation. We probe possible optimization strategies through the use of stable isotope tracing metabolomics, mass isotopologue distribution analysis, genetics, and physiological experiments. S. japonicus appears to have optimized cytosolic NADH oxidation via glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis. It runs a fully bifurcated TCA pathway, sustaining amino acid production. Finally, we propose that it has optimized glycolysis to maintain high ATP/ ADP ratio, in part by using the pentose phosphate pathway as a glycolytic shunt, reducing allosteric inhibition of glycolysis and supporting biomass generation. By comparing two related organisms with vastly different metabolic strategies, our work highlights the versatility and plasticity of central carbon metabolism in eukaryotes, illuminating critical adaptations supporting the preferential use of glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation.

Introduction

Establishing the rules of carbon metabolism, which produces biomass and energy, is critical for our understanding of life, from evolution to development to disease.1–6 In glycolysis, a molecule of glucose is catabolized to pyruvate, generating two ATP molecules. Pyruvate may be decarboxylated to acetaldehyde and then reduced to ethanol through fermentation, which oxidizes the NADH generated by glycolysis, rendering this metabolic strategy redox-neutral. Alternatively, in respiration, pyruvate may be converted to acetyl-CoA, which then enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Each round of the cycle provides precursors for amino acids and nucleotides, as well as generating NADH and succinate. NADH and succinate are oxidized via the electron transport chain (ETC), generating a potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane to power ATP synthesis. In yeasts that do not have the proton-pumping ETC complex I, respiration together with the catabolism of glucose via glycolysis can generate up to 16–18 ATP per glucose.7–11 Most eukaryotes are capable of both respiration and fermentation, but cells may choose one metabolic strategy over the other.12,13 For instance, Crabtree-positive yeasts such as Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) channel more glucose toward fermentation when ample glucose is available.13–15 Fermentation is less efficient at generating ATP, but it produces it quickly and at a low cost, while allowing Crabtree-positive species to divert glucose away from other organisms.1,11,15–19

Respiration may be the most efficient method also for NADH oxidation, which is essential to support growth.20,21 Indeed, the growth of non-respiring S. cerevisiae and S. pombe is improved by amino acid supplementation, suggesting that biomass production is limited when respiration is blocked.13,22,23 How is eukaryotic central carbon metabolism structured to overcome the limitations associated with the loss of respiration?

Unlike S. pombe, the related fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces japonicus (S. japonicus)24–31 thrives both in the presence and the absence of oxygen.32–37 Despite encoding most genes required for respiration, it does not produce coenzyme Q, does not grow on a non-fermentable carbon source glycerol, and does not consume oxygen during growth on glucose.32,33,36,38 We reasoned that understanding how S. japonicus manages its fully fermentative lifestyle might provide fundamental insights into the wiring of central carbon metabolism in eukaryotes.

Results

S. japonicus does not respire oxygen in various physiological situations

The cox6 gene encodes an evolutionarily conserved subunit of the ETC complex IV, which is essential for respiration in S. pombe.39 To test possible contributions of respiration to S. japonicus physiology, we analyzed the growth requirements and oxygen consumption in the wild-type and cox6⊿ S. japonicus and the corresponding strains of S. pombe.

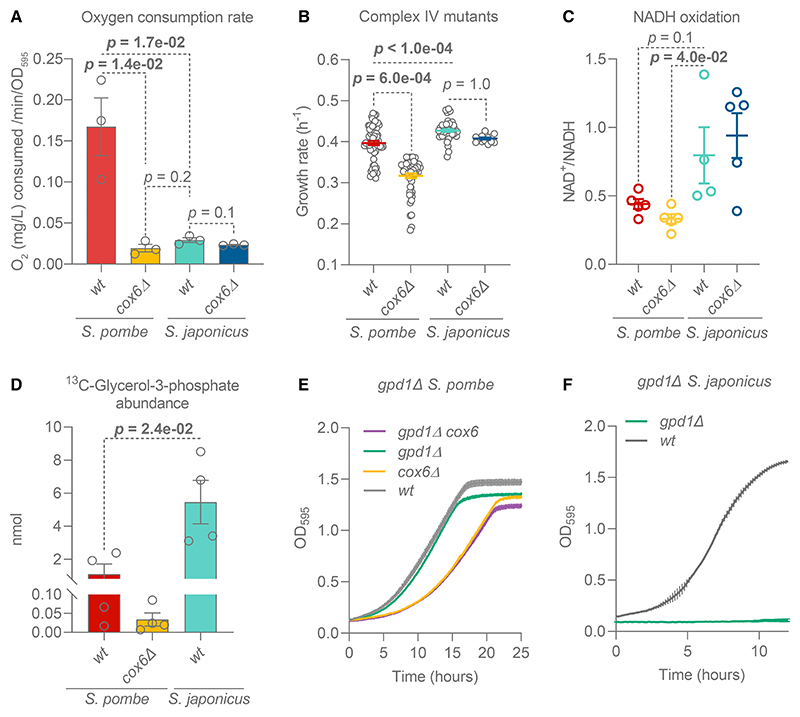

Consistent with previously published results,36 in a rich medium the wild-type S. japonicus exhibited a much lower oxygen consumption rate than S. pombe (Figure 1A). Whereas the deletion of cox6 critically decreased oxygen consumption in S. pombe, we observed no such effect in S. japonicus (Figure 1A). This result suggested that the minimal oxygen consumption in wild-type S. japonicus and cox6⊿ S. pombe cells was likely due to non-respiratory oxygen-consuming processes.40–42 S. japonicus did not grow on non-fermentable carbon sources, glycerol and galactose (Figure S1A), indicating that the lack of oxygen consumption in glucose was not due to respiratory repression. We observed this behavior in several wild isolates36,43 and S. japonicus var. versatilis,44,45 suggesting that this feature was a species-wide trait (Figure S1B).

Figure 1. S. japonicus does not respire but oxidizes NADH efficiently.

(A) Oxygen consumption rates of S. pombe and S. japonicus wild-type (WT) and cox6⊿ cultures in YES medium. Means are derived from three biological replicates.

(B) Growth rates of indicated strains in EMM medium. Means are derived from at least five biological repeats with three technical replicates.

(C) Cellular NAD+/NADH ratios. Means are derived from at least four biological replicates.

(D) Production of 13C-labeled glycerol-3-phosphate after 1 min of 13C6-glucose exposure. Means represent two biological and two technical replicates. (A–D) Error bars represent ±SEM; p values are derived from unpaired t test.

(E and F) Growth curves of S. pombe strains (E) in EMM medium and S. japonicus strains (F) in YES medium. Error bars represent ±SD. Shown are the means of OD595 readings derived from three technical replicates, representative of three biological repeats. See also Figure S1 and Data S1A.

S. pombe relies on ETC for rapid growth in minimal media, where cells must synthesize most biomass precursors.13,22 In contrast, the deletion of cox6 in S. japonicus did not impact the growth rate in the Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) (Figure 1B). Interestingly, whereas the growth rate of S. japonicus in EMM was approximately 15% higher than the respiro-fermenting S. pombe (Figure 1B), it produced less biomass, comparable with the S. pombe cox6⊿ mutant (Figure S1C). S. japonicus grows 1.5-times faster than S. pombe in the rich medium, which contains many biomass precursors. S. japonicus cox6⊿ mutants exhibited minor attenuation in the growth rate in yeast extract and supplements (YES) medium (Figure S1D). To test whether this phenotype was due to ETC disruption, we constructed a strain lacking rip1, which encodes a complex III subunit essential for respiration39 (Figure S1A). The growth rate of rip1Δ S. japonicus cells was comparable to that of the wild-type (Figure S1D), suggesting that the minor growth phenotype of cox6⊿ mutants observed in the YES medium was not due to the disruption of ETC or oxidative phosphorylation. Respiration plays an important role in sporulation and mating in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe.46,47 However, both cox6⊿ and rip1Δ S. japonicus mutants showed normal mating and sporulation efficiency (Figure S1E). Furthermore, we did not observe ETC-associated defects in hyphal growth (Figure S1F). Thus, the loss of ETC components largely did not affect key physiological states of S. japonicus.

A key function of the ETC is NADH oxidation.20,21 Interestingly, S. japonicus exhibited a whole-cell NAD+/NADH ratio similar to S. pombe; in fact, this ratio was higher than in non-respiring S. pombe mutants (Figure 1C). This finding suggests that S. japonicus has evolved ETC-independent mechanisms to efficiently oxidize NADH.

Anaerobically grown S. cerevisiae depends on the reduction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) by the G3P dehydrogenase Gpd1 to oxidize cytosolic NADH.48–50 We hypothesized that S. japonicus may rely on this reaction to sustain growth. We used stable isotope tracing coupled to gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GS-MS) to explore the rate of incorporation of glucose-derived carbons into the G3P pool.51,52 Of note, S. japonicus exhibited a higher rate of 13C incorporation into G3P as compared with S. pombe (Figure 1D). The non-respiring S. pombe cox6⊿ mutant did not upregulate G3P synthesis as compared with the wild-type. S. japonicus also maintained a larger pool of G3P than S. pombe (Figure S1G). G3P is typically used as a lipid precursor or converted to glycerol. Both intracellular and extracellular glycerol levels were comparable in S. pombe and S. japonicus (Figures S1H and S1I).

To test whether S. japonicus relied on DHAP reduction to sustain NADH oxidation in the absence of respiration, we generated the gpd1Δ strain. Strikingly, while the deletion of gpd1 in S. pombe did not negatively affect its growth, regardless of respiratory activity (Figures 1E and S1J), S. japonicus gpd1Δ cells were virtually incapable of growth, even in the rich medium, and could not be maintained at all in the minimal medium (Figure 1F). We conclude that S. japonicus critically depends on Gpd1 activity, whereas S. pombe may have additional mechanisms to oxidize cytosolic NADH.

S. japonicus operates a bifurcated TCA pathway with endogenous bicarbonate recycling, whereas S. pombe maintains both bifurcated and cyclic TCA variants

Respiration is typically associated with the TCA cycle, which allows for the additional oxidation of glucose, enabling more ATP production.10 The TCA cycle also generates crucial biomass precursors, alpha-ketoglutarate (aKG) and oxaloacetate, which are used to synthesize glutamate, aspartate, and other amino acids and metabolites (Figure 2A). In anaerobic S. cerevisiae, the TCA cycle bifurcates, with an oxidative branch running from acetyl-CoA to aKG and a reductive branch starting from the carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate, with subsequent conversion up to succinate.53 In the absence of respiration, bifurcation of the TCA cycle presumably enables cells to support oxaloacetate and aKG synthesis in a redox-neutral manner (Figure 2B). We assessed the TCA cycle architecture in S. pombe and S. japonicus using stable isotope tracing metabolomics, quantifying the ratios of different TCA-intermediate isotopologs after feeding cells with 13C6-glucose (Figures 2A and 2B). To mimic the “broken” TCA cycle, we included the S. pombe mutant lacking Sdh3, the key subunit of the succinate dehydrogenase complex.54–56 We used fumarate and succinate, the product and substrate of succinate dehydrogenase, as diagnostic metabolites.

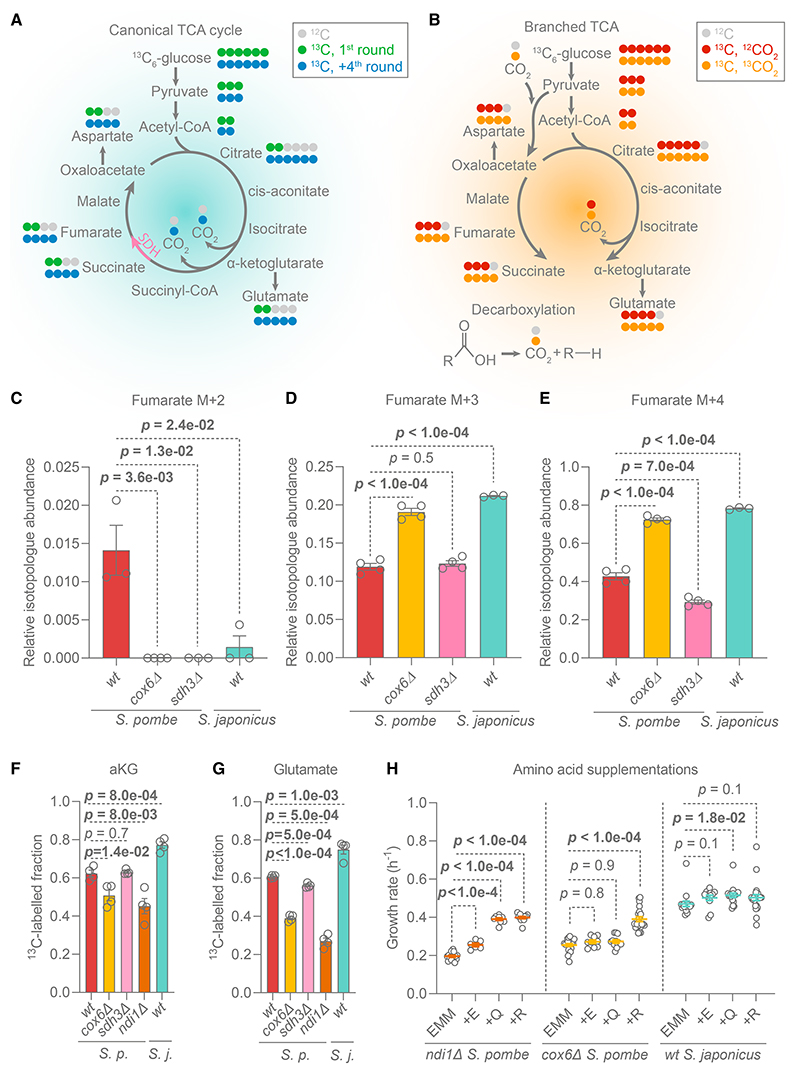

Figure 2. S. japonicus operates a bifurcated TCA pathway and efficiently synthesizes TCA-derived amino acids.

(A) Isotopologs of intermediates expected in the oxidative TCA cycle, after feeding 13C6-glucose. Pink arrow: the reaction catalyzed by succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). Isotopologs in green originate from the first cycle (M + 2 acetyl-CoA and M + 0 oxaloacetate). Isotopologs in blue are expected to be generated after the 4th cycle.52,57–59

(B) Isotopologs originating from the bifurcated TCA pathway. M + 3 pyruvate may be carboxylated using M + 0 CO2, leading to M + 3 oxaloacetate/aspartate (red),52,57–59 or M + 1 CO2, leading to M + 4 oxaloacetate/aspartate (orange).

(C–E) M + 2 (C), M + 3 (D), and M + 4 (E) fumarate fractions relative to the entire fumarate pool 30 min after 13C6-glucose addition.

(F and G) 13C-labeled alpha-ketoglutarate (F) and glutamate (G) fractions 30 min after 13C6-glucose addition.

(C–G) Shown are mean ±SEM of two biological and two technical replicates, p values were calculated using unpaired t test.

(H) Growth rates of S. pombe and S. japonicus grown in EMM with 0.2 g/L of either glutamate (E), glutamine (Q), or arginine (R). Mean ±SEM of three technical and at least two biological replicates are shown, with p values generated using unpaired t test. See also Figure S2 and Data S1D.

M + 2 fumarate is typically associated with the oxidative TCA cycle52,57–59 (Figure 2A). Indeed, only respiro-fermenting wild-type S. pombe showed M + 2 fumarate (Figure 2C). M + 3 fumarate likely originates from the reductive TCA branch52,57–59 (Figure 2B). Interestingly, both wild-type and cox6⊿ S. pombe, and wild-type S. japonicus, showed high M + 3 fumarate fractions (Figure 2D). This indicates that not only S. japonicus and non-respiring S. pombe but also the wild-type S. pombe operate the reductive TCA branch. However, the inability to respire in both fission yeasts leads to an increase in M + 3 fumarate labeling, suggesting greater use of the bifurcated TCA architecture. The oxidative branch appears to extend to succinate, as suggested by M + 2 succinate labeling in cox6⊿ and sdh3Δ S. pombe and wild-type S. japonicus (Figure S2A).

M + 4 fumarate is thought to result from repeated oxidative TCA cycles52,57–59 (Figure 2A). The wild-type S. pombe indeed showed a M + 4 fumarate signal. However, this isotopolog was also abundant in both non-respiring cox6⊿ S. pombe and the wild-type S. japonicus (Figure 2E). The proportion of M + 4 fumarate in S. pombe was only minimally affected by the deletion of sdh3, which disrupts the oxidative cycle.60 In principle, M + 4 fumarate could be produced in the reductive branch from M + 4 oxaloacetate (Figure 2B), originating from the carboxylation of the M + 3 pyruvate using M + 1 bicarbonate.61 Indeed, we observed M + 4 aspartate (proxy for oxaloacetate) in both fission yeasts and their TCA cycle mutants (Figure S2B). The labeled bicarbonate is likely released from decarboxylating reactions,61 such as conversion of pyruvate to acetaldehyde in fermentation.10 Thus, a large fraction of M + 4 fumarate—even in respiring cells—could be a product of the reductive TCA branch and the recycling of endogenous bicarbonate.

Interestingly, both wild-type and sdh3Δ S. pombe cells had M + 4 succinate but lacked M + 3 fractions, in contrast with S. japonicus and the non-respiring cox6⊿ S. pombe mutant (Figures S2C and S2D). This suggests that the reduction of fumarate to succinate by fumarate reductase in S. pombe favors M + 4 fumarate, possibly due to distinct compartmentalization of fumarate isotopologs in respiro-fermenting cells.

Taken together, our genetic and metabolomics data suggest that (1) S. japonicus operates a bifurcated TCA pathway with endogenous bicarbonate recycling and (2) the respiro-fermenting S. pombe uses a combination of bifurcated and cyclic TCA reactions.

Efficient NADH oxidation, but not cyclic TCA activity, is required to sustain glutamate synthesis

It has been postulated that sufficient production of aKG-derived amino acids, such as glutamate and arginine, requires a canonical TCA cycle.22,23,62 Seemingly in agreement with that hypothesis, aKG and glutamate labeling from 13C-glucose was lower in the non-respiring S. pombe cox6⊿ mutant as compared with the wild-type (Figures 2F and 2G). However, both aKG and glutamate were labeled to a higher degree in S. japonicus than in S. pombe (Figures 2F and 2G). The S. pombe sdh3Δ mutants, which have a broken TCA cycle, labeled aKG and glutamate similarly to the wild-type and grew normally in the minimal medium (Figures 2F, 2G, and S2E). These results suggest that some aspect of respiration, rather than running the canonical TCA cycle, is important for glutamate synthesis in S. pombe, whereas S. japonicus has evolved a respiration-independent strategy to sustain amino acid production.

The oxidative branch of the TCA cycle generates NADH, which must be re-oxidized to support TCA reactions and biomass production. We wondered whether decreased NADH re-oxidation in mitochondria was responsible for the reduced aKG and glutamate labeling in S. pombe cox6⊿ mutants. Ndi1 is the matrix-facing NADH dehydrogenase associated with the ETC. Deleting ndi1 did not abolish respiration in S. pombe, as despite the attenuation of growth rate in EMM (Figure S2E), ndi1Δ mutants could grow on a non-fermentable medium (Figure S2F). Interestingly, S. pombe ndi1Δ cells showed a pronounced reduction in aKG and glutamate labeling (Figures 2F and 2G). Accordingly, supplementation with aKG-derived amino acids—glutamate, glutamine, or arginine—improved their growth in EMM (Figure 2H). Surprisingly, the growth defect of S. pombe cox6⊿ mutants in EMM could be rescued by arginine but not glutamate or glutamine (Figure 2H). This finding indicates that the arginine dependency of non-respiring cox6⊿ S. pombe is not due to limited aKG production. S. japonicus appears to have overcome this limitation (Figure 2H).

Taken together, our results suggest that as long as cells can efficiently re-oxidize NADH generated by the oxidative TCA branch, a bifurcated TCA architecture can sustain amino acid synthesis and biomass production.

S. japonicus sustains higher glycolytic activity than

S. pombe

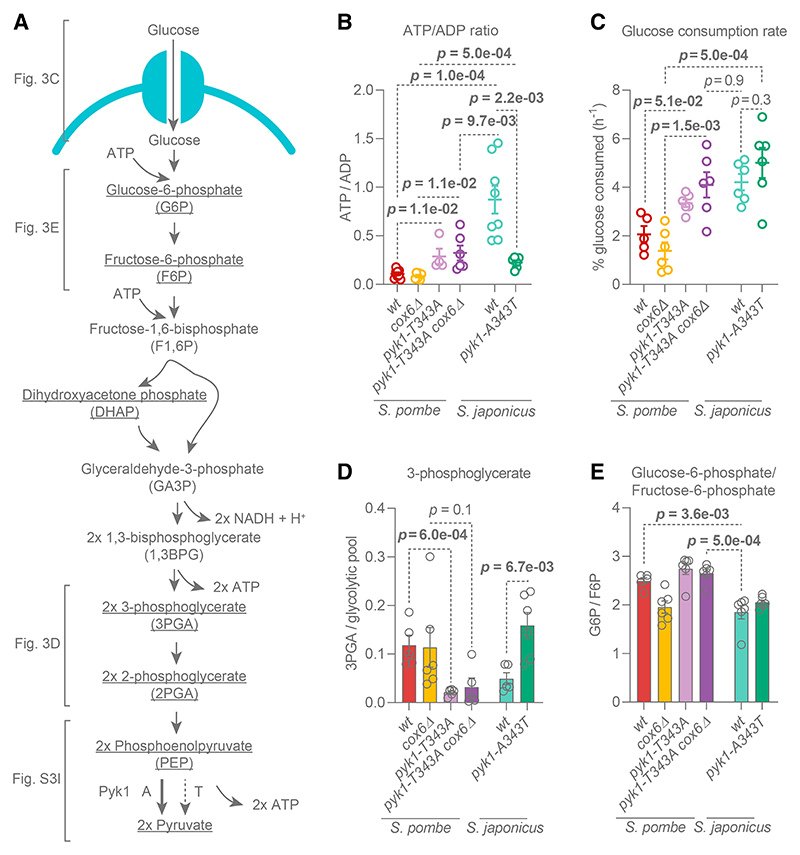

Respiration allows for additional oxidation of carbon substrates, producing more ATP than glycolysis alone (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, S. japonicus exhibited higher ATP levels (Figure S3A) and a higher ATP/ADP ratio as compared with both respiro-fermenting (wild-type) and solely fermenting (cox6D) S. pombe (Figure 3B). This suggests that the energetic output of glycolysis in S. japonicus is higher than that of S. pombe.

Figure 3. S. japonicus maintains higher glycolytic activity than S. pombe.

(A) Glycolysis and its outputs. Blue: plasma membrane hexose transporter. Underlined: metabolites quantified in this study. Pyruvate kinase Pyk1 is indicated, with A and T denoting the point mutation at site 343.

(B) Whole-cell ATP/ADP ratios. Mean ±SEM values of at least four biological replicates. p values were calculated using unpaired t test.

(C) Rate of glucose uptake in EMM. Mean ± SEM of at least five biological replicates are shown. p values were calculated using unpaired t test.

(D)3-phosphoglycerate abundance relative to the sum of detected glycolytic intermediates (G6P, F6P, DHAP, 3PGA, 2PGA, PEP, and pyruvate).

(E) Glucose-6-phosphate levels relative to fructose-6-phosphate.

(D and E) Shown are mean ±SEM of three technical and two biological replicates. p values were calculated using unpaired t test. See also Figure S3 and Data S1E.

The laboratory “wild-type” strain of S. pombe has a partial loss-of-function alanine-to-threonine point mutation at position 343 (A343T) in the pyruvate kinase Pyk1, which catalyzes the last energy-yielding step of glycolysis63 (Figure 3A). The Pyk1 kinase in S. japonicus does not have this substitution. To test whether higher Pyk1 activity is solely responsible for more efficient ATP production via glycolysis in this organism, we constructed a pyk1-A343T S. japonicus mutant. To specifically home in on the energetic output of glycolysis, we also made a non-respiring S. pombe strain with higher Pyk1 activity (pyk1-T343A cox6D). Consistent with previous work,63 the higher Pyk1 activity in S. pombe increased the cellular ATP/ADP ratio, whereas the lower Pyk1 activity in S. japonicus reduced it (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the higher Pyk1 activity did not affect the total ATP levels in S. pombe, although the lower Pyk1 activity did reduce this pool in S. japonicus (Figure S3A). The ATP/ADP ratio of wild-type S. japonicus was still higher than that of pyk1-T343A cox6⊿ S. pombe (Figure 3B). This result is notable because both the wild-type S. japonicus and pyk1-T343A cox6⊿ S. pombe mutant do not respire and presumably have comparable levels of pyruvate kinase activity.

We measured the glucose uptake of exponentially growing cultures to estimate glycolytic rates in the two sister species.64,65 The higher activity of Pyk1 improved glucose uptake in S. pombe, regardless of respiratory activity (Figure 3C). The glucose uptake rate of S. japonicus was similar to that of the non-respiring S. pombe with high Pyk1 activity (pyk1-T343A cox6D). Interestingly, glucose uptake remained high in S. japonicus, even when we introduced the S. pombe-specific partial loss-of-function pyk1-A343T allele (Figure 3C). This suggests that, unlike in S. pombe, glycolysis in S. japonicus is not regulated as tightly by the pyruvate kinase. Notably, whereas the pyk1 alleles do play a major role in modulating ATP production via glycolysis, S. japonicus might have evolved additional means of maximizing glycolytic output.

To further probe the regulation of glycolysis, we quantified glycolytic intermediates using GC-MS. The abundance of each intermediate was expressed as a fraction of the whole glycolytic intermediate pool, as this allowed us to pinpoint potential regulatory points (Figures S3B–S3H). Corroborating published data, we observed a release in the phosphoenolpyruvate-to-pyruvate bottleneck when introducing a more active pyk1 allele to S. pombe (Figure S3I). Suggesting that the pyruvate kinase activity could indeed regulate glycolysis as a whole, we have observed a Pyk1-activity-dependent bottleneck at the 3-phosphoglycerate level in S. pombe (Figure 3D). In line with the predicted higher pyruvate kinase activity in S. japonicus, we detected the accumulation of both phosphoenolpyruvate and 3-phosphoglycerate after introducing the S. pombe-like pyk1-A343T allele to this species (Figures 3D and S3I).

Interestingly, regardless of the pyk1 allele, S. japonicus exhibited a lower glucose-6-phosphate to fructose-6-phosphate (G6P/F6P) ratio than S. pombe (Figure 3E). This suggested that G6P was consumed more rapidly in S. japonicus, highlighting potential differences in upper glycolysis between the two organisms.

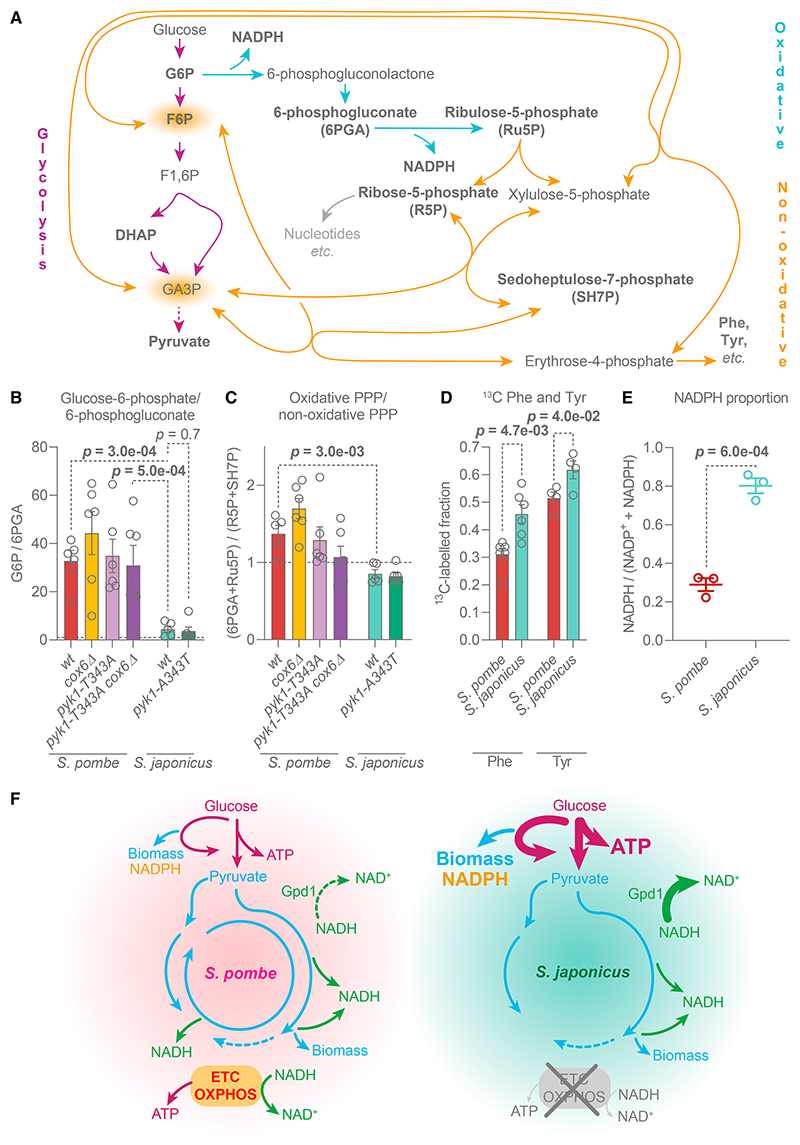

S. japonicus may upregulate upper glycolysis via the pentose phosphate pathway

A major route utilizing G6P is the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the G6P to 6-phosphogluconate (G6P/6PGA) ratio was considerably lower in S. japonicus as compared with S. pombe (Figure 4B). This suggested that S. pombe has a bottleneck at the PPP entry point but S. japonicus may channel large amounts of G6P into the PPP. This phenomenon was independent of the pyruvate kinase activity (Figure 4B). Indicating a steady-state conversion of 6PGA to ribulose-5-phosphate, the ratio of these metabolites in S. japonicus was close to 1 (Figure S4A).

Figure 4. S. japonicus may upregulate the entry into the pentose phosphate pathway.

(A) PPP and its intersection with glycolysis. Bold: metabolites quantified in this study. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; F1,6BP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; Phe, phenylalanine; Tyr, tyrosine.

(B) Glucose-6-phosphate abundance normalized to 6-phosphogluconate.

(C) Sum of oxidative PPP intermediates (6PGA and Ru5P) relative to non-oxidative PPP intermediates (R5P and SH7P).

(B and C) Dotted lines indicate the ratio of 1.

(D)13C-labeled phenylalanine and tyrosine fractions 10 min after 13C6-labeled glucose addition.

(B–D) Mean ±SEM of two biological and two to three technical replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t test.

(E) Cellular NADPH relative to a total NADP(H) pool. Mean ±SEM of three biological replicates, p values estimated using unpaired t test.

(F) A diagram summarizing the findings of this study. ETC, electron transport chain; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation. See also Figure S4 and Data S1E–S1G.

The PPP is composed of an oxidative followed by a non-oxidative branch. The latter allows cells to redirect carbon back into glycolysis66–70 (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the ratio of oxidative relative to non-oxidative PPP products was higher in S. pombe as compared with S. japonicus, indicating a potential bottleneck at the transition between the two branches in the former (Figure 4C; see individual data for ribulose-5-phosphate/ribose-5-phosphate and ribose-5-phosphate/sedoheptulose-7-phosphate ratios in Figures S4B and S4C). Importantly, we detected higher labeling of phenylalanine and tyrosine, amino acids produced from the non-oxidative PPP (Figure 4A), from 13C-glucose in S. japonicus than S. pombe (Figure 4D).

Finally, we observed a considerably higher NADPH/total NADP(H) ratio in S. japonicus as compared with S. pombe (Figure 4E). As NADPH is a product of oxidative PPP (Figure 4A), our results indicate that this pathway may operate at a higher capacity in S. japonicus.

Taken together, these results indicate that S. japonicus may use PPP to upregulate glycolysis by preventing the accumulation of upper glycolytic intermediates, thus reducing feedback-inhibition of this pathway. Additionally, upregulated PPP could support anabolism by providing biomass precursors and NADPH.

Discussion

Our work suggests that the non-respiring S. japonicus has optimized its energy and redox metabolism to support rapid growth at the expense of biomass production yield (Figure 4F).

First, S. japonicus relies on cytosolic DHAP reduction to reoxidize NADH (Figures 1D and 1F). Although diverting DHAP away from glycolysis may reduce ATP yield, there are several advantages to this strategy. In addition to supporting amino acid and nucleotide anabolism by regenerating NAD+, the high activity of G3P dehydrogenase Gpd1 may provide more glycerol backbones for lipid synthesis.71 Furthermore, high Gpd1 activity could prevent the build-up of DHAP, which can be converted to the toxic by-product, methylglyoxal.72 S. pombe appears to use alternative NADH oxidation strategies during non-respiratory growth (Figure 1E). Obvious candidates include alcohol dehydrogenases and the NAD(H)-dependent malic enzyme Mae2,63,73,74 or the lactate dehydrogenase SPAC186.08c75 that is absent in the genomes of either S. japonicus or budding yeast.35,76,77

Second, S. japonicus supports the production of amino acids derived from the TCA cycle by running a bifurcated version of this pathway. Interestingly, even S. pombe, which requires respiration for optimal growth, runs both bifurcated and canonical TCA cycles (Figure 2). Presumably, the bifurcated version allows for better biomass production by committing oxaloacetate and aKG to amino acid synthesis. In S. pombe, the bifurcated TCA pathway yielding biomass still depends on ETC-dependent NADH oxidation (Figures 2F–2H). By utilizing the bifurcated TCA pathway alongside respiration, this organism maintains rapid growth and biomass production. Yet, the fast growth of S. japonicus demonstrates that this is not the only effective strategy. Interestingly, S. japonicus has lost the NAD(H)-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh1/2), while retaining the NADP(H)-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase Idp1.35,77 Furthermore, it has lost one of the NAD(H)-dependent glutamate dehydrogenases, Gdh2, but kept the NADP(H)-specific glutamate dehydrogenase, Gdh1.35,77–79 This suggests that besides evolving efficient NADH oxidation pathway(s), S. japonicus may have alleviated the NADH burden by changing the cofactor dependencies of anabolic enzymes.

Third, S. japonicus maintains high ATP levels and a high ATP/ADP ratio by maximizing glycolysis, presumably through a combination of high pyruvate kinase activity and by diverting G6P through the PPP (Figures 3 and 4). Diverting G6P away from glycolysis and reintroducing carbon back at the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate level may reduce allosteric inhibition of hexo-kinase and help maintain high glycolytic activity.65,80

Of note, the replacement of S. japonicus pyk1 with the S. pombe-like allele of the pyruvate kinase did not reduce glucose uptake (Figure 3C). This suggests that S. japonicus upper glycolysis is less tightly regulated by lower glycolysis as compared with its sister species. Presumably, this feature allows S. japonicus to sustain rapid glycolysis in situations where it normally would be inhibited, such as low pH81,82 or low glucose levels.83–85 The latter could be particularly important because S. japonicus cannot rely on respiration as a metabolic strategy for dealing with starvation, unlike S. pombe.12,13,56 Interestingly, S. japonicus has lost the fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase Fbp1,35,77 rendering it incapable of gluconeogenesis.86 The lack of Fbp1 may also prevent the suppression of glycolysis in low glucose,87 which is arguably vital for a non-respiring organism. The lack of gluconeogenesis in S. japonicus may support the use of the non-oxidative part of the PPP as a one-way shunt into glycolysis and would prevent the recycling of F6P and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate into the oxidative PPP.67 Overall, a combination of upregulated PPP, “good” pyruvate kinase, and other adaptations reducing negative feedback on glycolysis allows S. japonicus to maintain high ATP levels independent of oxidative phosphorylation.

Finally, the upregulation of the PPP may allow S. japonicus to rapidly produce nucleotides and some amino acids, together with NADPH, which is key for several anabolic pathways, e.g., lipid metabolism88 (Figures 4D and 4E). S. japonicus is highly sensitive to paraquat and hydrogen peroxide,36 despite high levels of NADPH, which is needed for the reduction of glutathione and thioredoxin.89,90 It is plausible that over the course of its life history, which has involved adaptation to anaerobic environments, this species has lost some capacity to manage oxidative stress.

S. japonicus, as a committed fermenting species, may successfully compete with other organisms by growing rapidly, sequestering glucose, and secreting ethanol and other toxic waste products.36,43 Critically, S. japonicus grows well both in the presence and absence of oxygen,32–37 allowing it to explore different ecological niches. Yet, the inability to respire restricts this species toa narrow range of carbon sources. Furthermore, the lack of respiration may account for its relatively low biomass yield (Figure S1C). This is consistent with the behavior of Crabtree-positive yeasts, which also grow rapidly but to a lower final biomass content.11,15 Such trade-offs may manifest in the wild, giving S. japonicus selective advantage only in the environments replete with nutrients and glucose. Indeed, S. japonicus grows at a considerably higher rate (1.6-times faster) in the rich medium, where many biomass precursors are available, as compared with the EMM. However, our work suggests that it has evolved a range of strategies to thrive even in nutritionally sub-optimal conditions, for instance in EMM, when it is forced to synthesize most biomass precursors.

S. japonicus shares a number of metabolic traits with the anaerobically growing S. cerevisiae, including the reliance on G3P dehydrogenase-dependent NADH oxidation and the use of the bifurcated TCA pathway.48,53,91 Its innovations may include the potential optimization of glycolysis through the PPP shunt and the extension of the oxidative TCA branch to succinate. In anaerobic budding yeast, succinate appears to be made from the oxidative TCA branch when glutamate is supplemented.53 Such an extension may allow S. japonicus to undergo the TCA substrate-level phosphorylation at the succinate-CoA ligase step. Finally, S. japonicus does not secrete more glycerol as compared with S. pombe, unlike S. cerevisiae that upregulates glycerol production in anoxia due to increased G3P synthesis and dephosphorylation.48 Coincidentally, S. japonicus cannot consume secreted glycerol (Figures S1A and S1B), unlike budding yeast.

Our study lays the groundwork for better understanding of central carbon metabolism in fission yeasts and beyond. We demonstrate the power of stable isotope tracing metabolomics, mass isotopologue distribution analyses, and genetic perturbations in illuminating the architecture of metabolic pathways in yeasts. Importantly, our work showcases a comparative biology approach to understanding metabolism.

Central carbon metabolism is woven tightly into the fabric of cellular biology. Understanding the plasticity of metabolism—both in ontogenetic and phylogenetic terms—may ultimately aid in explaining organismal ecology and the evolution of higher-level cellular features, such cell size and growth rate.

Star⋆Methods

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

-

○

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

-

○RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

- Lead contact

- Materials availability

- Data and code availability

-

○

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

-

○METHOD DETAILS

- Serial dilution assays

- Hyphae formation assay

- Sporulation efficiency assay

- Molecular genetics

- Oxygen consumption

- Biomass yield coefficient determination

- Glucose consumption

- NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H quantification

- ATP/ADP quantification

- Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics

- Analysis of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics data

-

○

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Star+Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | |||||

| Methanol hypergrade for LC-MS LiChrosolv | Merck | Cat#1.06035 | |||

| Chloroform LiChrosolv | Merck | Cat#1.02444 | |||

| Acetonitrile hypergrade for LC-MS LiChrosolv | Merck | Cat#1.00029 | |||

| Water, Optima™ LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | Cat#W6500 | |||

| 13C labeled glucose | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories | Cat#CLM-1396-PK | |||

| Scyllo-inositol | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#I8132 | |||

| Methoxyamine hydrochloride, for GC derivatization, LiChropur™, 97.5-102.5% (AT) |

Sigma Aldrich | Cat#89803 | |||

| Pyridine | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#360570 | |||

| N,O-bis(trimetylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide and 1% trimethylchlorosilane | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#15238 | |||

| Critical commercial assays | |||||

| NAD/NADH Quantitation Kit | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#MAK037 | |||

| NADP/NADPH Quantitation Kit | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#MAK038 | |||

| ADP/ATP Ratio Assay Kit | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#MAK-135 | |||

| Glucose (HK) Assay Kit | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#GAHK20 | |||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | |||||

| S. pombe nde1 Δ::kanR h? | This paper | SO8547 | |||

| S. pombe ndi1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SO8587 | |||

| S. pombe rip1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SO8688 | |||

| S. pombe sdh3Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SO8695 | |||

| S. pombe cox6⊿::kanR h- | This paper | SO8727 | |||

| S. pombe gpd1Δ::hygR h? | This paper | SO8991 | |||

| S. pombe gpd1Δ::hygR, ndi1Δ::kanR h? | This paper | SO9034 | |||

| S. pombe gpd1Δ::hygR, nde1 Δ::kanR h? | This paper | SO9036 | |||

| S. pombe gpd1Δ::hygR, rip1Δ::kanR h? | This paper | SO9038 | |||

| S. pombe gpd1 Δ::hygR, cox6⊿::kanR h? | This paper | SO9040 | |||

| S. pombe mdh1 Δ::hygR h+ | This paper | SO9046 | |||

| S. pombe fum1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SO9078 | |||

| S. pombe pyk1T343A h- | Kamrad et al.63 | SO9109 | |||

| S. pombe pyk1T343A, cox6⊿::kanR h- | This paper | SO9271 | |||

| S. japonicus gpd1 Δ::natMX6 h+ | This paper | SOJ3553 | |||

| S. japonicus var. versatilis sjk4 h90 iodine stain positive | Yu et al.44 and Klar45 | SOJ3571 | |||

|

S. japonicus Wild isolate 1; YH156 from

oak bark, Northeastern Pennsylvania, U.S.A. |

Osburn et al.43 | SOJ3572 | |||

|

S. japonicus Wild isolate 2; YH157 from

oak bark, Northeastern Pennsylvania, U.S.A. |

Osburn et al.43 | SOJ3573 | |||

| S. japonicus Wild isolate 3; from Matsue, Japan | Kaino et al.36 | SOJ3574 | |||

| S. japonicus Wild isolate 4; from Hirosaki, Japan | Kaino et al.36 | SOJ3575 | |||

| S. japonicus Wild isolate 5; from Nagano, Japan | Kaino et al.36 | SOJ3576 | |||

| S. japonicus mdh1 Δ::hygR h- | This paper | SOJ3884 | |||

| S. japonicus pyk1A343T h- | This paper | SOJ3910 | |||

| S. japonicus ndi1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ4540 | |||

| S. japonicus rip1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ4542 | |||

| S. japonicus nde1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ4543 | |||

| S. japonicus cox6⊿::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ4545 | |||

| S. japonicus sdh3Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ5182 | |||

| S. japonicus ndi1 Δ::kanR h+ | This paper | SOJ5199 | |||

| S. japonicus nde1 Δ::kanR h+ | This paper | SOJ5201 | |||

| S. japonicus rip1 Δ::kanR h+ | This paper | SOJ5203 | |||

| S. japonicus cox6⊿::kanR h+ | This paper | SOJ5204 | |||

| S. japonicus fum1 Δ::kanR h- | This paper | SOJ5212 | |||

| Software and algorithms | |||||

| MANIC | Behrends et al.92 | N/A | |||

| Masshunter Workstation Qualitative | Agilent Technologies | N/A | |||

| Analysis 10.0 | |||||

| ImageJ | Schindelin et al.93 | N/A | |||

| Growthcurver | Sprouffske and Wagner 94 | N/A | |||

| Other | |||||

| Hanna waterproof field Dissolved | Scientific Laboratory Supplies | Cat#PHM0358D2 | |||

| Oxygen meter with BOD | |||||

| VICTOR Nivo Multimode Plate Reader | Perkin Elmer | N/A | |||

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Snezhana Oliferenko (snezhka.oliferenko@crick.ac.uk).

Experimental Model And Subject Details

S. pombe and S. japonicus prototrophic strains used in this study are listed in key resources table. We used standard fission yeast media and methods.95,96 For non-fermentable conditions, we used EMM with 2% glycerol or 2% galactose and 0.1% glucose. The inclusion of 0.1% glucose is necessary for S. pombe growth in these conditions.56,97 Temperature-controlled 200 rpm shaking incubators we used for liquid cultures. For most experiments, yeasts were pre-cultured in Edinburgh Minimal Medium (EMM) at 30°C. Pre-cultures for growth, serial dilution or oxygen consumption experiments were grown in rich Yeast Extract and Supplements (YES) medium at 24°C. All cultures were grown in a 200rpm shaking incubator. The following day, cultures were diluted to an OD595 within lag-phase or early-exponential phase, as required, and allowed to grow to a desired OD595. Once cultures reached early (0.2-0.5 OD595) or mid-exponential phase (OD595 determined by each strain and condition’s OD595 at stationary phase), cells were collected.

In the case of growth experiments, post-dilution growth was tracked in a plate reader, as follows. Yeasts were pre-cultured in YES at 25°C until OD595 0.1-0.6. Cultures were then washed in experimental medium and diluted to 0.1 OD595. Growth was measured every 10 min at 30°C using VICTOR Nivo multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer). Growth curves were plotted using Graphpad Prism and growth rates were calculated using the Growthcurver R package.94 All experiments were performed in three technical and at least three biological replicates. Technical replicates were three wells in a 96-well plate; biological replicates were independent growth experiments using freshly-defrosted batches of each strain.

Mating of S. pombe and S. japonicus strains was performed on SPA solid medium. Spores were dissected and germinated on YES agar plates.

Method Details

Serial dilution assays

Serial dilution assays were performed by preculturing cells in YES at 25°C overnight until early-exponential phase. Cultures were diluted to 2×106 cells/ml and serially diluted by a factor of 10. 2ml of each dilution were inoculated on plates. Plates were typically incubated at 30°C for three days. All experiments were repeated three times, using freshly-defrosted strains.

Hyphae formation assay

S. japonicus cultures grown at 24°C overnight in YES to exponential phase were centrifuged and washed once in YES. The equivalent of OD595 0.5 was inoculated on Yeast Extract Glucose Malt Extract Agar plates and incubated at 30°C for five days. Surface colonies were gently washed away to retain only the hyphae formed within the agar. Plates were imaged and ImageJ93 was used to measure the diameter of hyphal zone. Experiments were repeated at least thrice using freshly defrosted strains.

Sporulation efficiency assay

S. japonicus wild-type and deletion strains of the opposite mating types, carrying the KanMX (KanR) selection marker, were crossed on SPA plates overnight at 30°C. The following day, a defined numbers of spores were dissected on YES plates using a Singer MSM micromanipulator (Singer Instruments). Between 50 and 100 spores per biological replicate were dissected. Spores were allowed to germinate over three days at 30°C. Spores that formed colonies versus the total spores dissected were counted to estimate sporulation efficiency. Colonies of spores from wild-type and deletion strain crosses were replica-plated onto YES plates with or without G418 sulphate (Sigma Aldrich) and spores that grew in the presence of G418 versus normal YES plates were counted to determine the KanMX positivity score. Experiments were replicated at least three times.

Molecular genetics

Molecular genetic manipulations were performed via homologous recombination using the gene deletion cassette method,98,99 where target genes’ open reading frames were replaced by kanR, NatR or HygR cassettes flanked by 80-base-pair portions of the 5’ and 3’ UTRs of the gene of interest.

S. pombe was transformed using the lithium acetate method, as previously described.100 Briefly, early-exponential S. pombe cultures grown in YES were centrifuged and washed twice in dH2O. Cells were then washed in lithium acetate Tris-EDTA and incubated in 100ml of the same buffer for 10 min at room temperature together with 5mg of linear DNA and 50mg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (Agilent Technologies). 240Δl of PEG-lithium acetate Tris-EDTA was added and cell suspension was mixed by swirling with a pipette tip. Samples were incubated at 30°C for 30–60 min. 43Δl of DMSO was then added and cells were washed in dH2O twice. Cells were then recovered in 10ml of YES at 25°C overnight and subsequently inoculated on selective plates – YES plates containing 100mg/mL G418 sulphate (Sigma Aldrich), 50Δg/mL hygromycin B (Sigma Aldrich), or 100Δg/mL nourseothricin (Werner BioAgents, Germany).

S. japonicus was transformed using electroporation.96 Briefly, early-exponential cultures grown in YES were pelleted and from then on kept on ice. Cells were washed three times using ice-cold dH2O and then were suspended in 5ml of cold 1M sorbitol with 50mM dithiothreitol in dH2O. Suspensions were incubated for 12 min at 30°C without shaking, after which cells were centrifuged and washed twice with cold 1M sorbitol. Pellets were then resuspended in 100Δl 1M sorbitol containing linearised DNA and sonicated salmon sperm DNA (Agilent Technologies). Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min. S. japonicus was subsequently electroporated at 2.30keV using a cold 2mm Gene Pulser/MicroPulser Electroporation Cuvette (Bio-Rad laboratories). Immediately after electroporation, 1ml of cold 1M sorbitol was added to the cell suspension, and cells were recovered overnight at 25°C in 10ml YES, shaking. The next day, cells were plated on selective plates, as with S. pombe.

Oxygen consumption

Oxygen levels were measured using a waterproof field Dissolved Oxygen meter (Hanna HI 98193). Oxygen consumption was measured in mid-exponential cultures grown in YES. Cultures were centrifuged, cells were resuspended in fresh medium and used to fill a conical flask to the brim. The probe was submerged into the culture and the flask was sealed. Cultures were kept in gentle motion using a magnetic stirrer. Once oxygen readings stabilised, oxygen levels were recorded every minute for 10 min, after which the OD595 of cultures were recorded. Cultures were at room temperature during oxygen readings. Oxygen concentration over the time course was plotted to identify when oxygen changes slowed or plateaued. Selected linear oxygen changes were used to calculate the oxygen consumption rate per minute, which were normalised to the culture OD595. Measurements were independently repeated three times to yield three biological replicates.

Biomass yield coefficient determination

Cells were pre-cultured in YES until early-exponential phase, after which they were diluted in EMM with 2% glucose to OD595 0.1 and incubated at 30°C until stationary phase was reached. 5ml of cultures were dried over 48 h at 70°C and pellets were weighed. Alongside the dry weight, we measured glucose levels in EMM and the conditioned EMM at the time of collection using Glucose (HK) Assay Kit (Sigma Aldrich) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The biomass yield coefficient was calculated using the dry weight divided by the change in glucose levels over the growth period. Data shown is the result of three technical and two biological replicates.

Glucose consumption

Cells were pre-cultured in EMM with 2% glucose and once cultures reached early exponential phase, they were diluted to OD595 0.1 and incubated overnight at 30°C. When cultures reached mid-exponential phase, cells were centrifuged and resuspended in fresh medium. Cultures were placed in a shaking incubator at 30°C and media samples were collected after 2 h. The percentage of glucose consumed during the incubation time was normalised to the change in OD595 in the same period, and the result was multiplied by the growth rate of each strain (h-1). Glucose was quantified using Glucose (HK) Assay Kit (Sigma Aldrich) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were collected as independent biological replicates from cultures grown on separate occasions, using freshly-defrosted strains.

NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H quantification

Cells were pre-cultured in EMM overnight at 30°C until early-exponential phase. Subsequently, cultures were diluted to OD595 0.1 and were grown overnight at 30°C. The equivalent of OD595 5 of early-exponential (in the case of NAD+/NADH) or mid-exponential (in the case of NADP+/NADPH) cultures were harvested by centrifugation and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. NAD+/NADH was extracted and measured using MAK037 (Sigma Aldrich) and NADP+/NADPH was extracted and measured using MAK038 (Sigma Aldrich) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were resuspended in chilled extraction buffer and lysed using lysing matrix Y tubes (MP Biomedicals) containing 0.5 mm diameter yttria-stabilized zirconium oxide beads and a cell disruptor (MP Biomedicals). Samples were kept as cold as possible by bead beating in 10 second intervals, at 6.5m/sec, 10 times, with 2-min breaks on ice between each round. Samples were then filtered through a 10kDa protein filter (MRCPRT010, Sigma Aldrich) via centrifugation at 4°C. Extracts were then processed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were collected in at least three independent experiments. Quantification was performed using a Tecan Spark plate reader.

ATP/ADP quantification

Cells were pre-cultured in EMM overnight at 30°C until early-exponential phase. Subsequently, cultures were diluted to OD595 0.1 and were grown overnight at 30°C. Early-exponential cultures in EMM were collected by quenching the equivalent of OD595 5 cells in -80°C methanol. Suspensions were centrifuged at 3000rpm for 2 min at 4°C and decanted, and pellets were dried in -80°C overnight. ATP and ADP were extracted and quantified using the ATP/ADP ratio quantification kit (MAK-135, Sigma Aldrich) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, with the following modification. To extract ATP and ADP, cell pellets were lysed in the kit’s assay buffer using lysing matrix Y tubes (MP Biomedicals) containing 0.5 mm diameter yttria-stabilized zirconium oxide beads and a cell disruptor. Samples were kept as cold as possible by bead beating once for 10 seconds at 6.5m/sec at 4°C. Bioluminescence was quantified using a Tecan Spark microplate reader. Samples were collected as at least three biological replicates from cultures grown on separate occasions, using freshly defrosted strains.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics

For metabolomics experiments, cells were pre-cultured in EMM and diluted the previous day so that cells were in early-exponential phase at the time of harvest. In the case of stable isotope tracing experiments, pre-cultures and experimental cultures were both grown in EMM at 24°C. When cultures reached an OD595 of 0.2-0.4, cells were centrifuged at 3000rpm for 2 min and resuspended in either unlabelled (12C) or labelled (13C) media without dilution. Labelled media refers to EMM with 2% D-Glucose (U-13C6) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.). Once cells came into contact with labelled media, a time course was started. Cells were kept agitated until each time point was reached. At 1, 3, 5, 10, 30 or 60 min, a volume equivalent to 1.5 OD595 was injected into 100% LCMS-grade methanol (Sigma Aldrich) pre-cooled to -80°C. Quenched cultures were centrifuged and washed twice with -80°C methanol, centrifuging at 4°C and 3000rpm. The dried pellets stored at -80°C until extraction. For abundance quantification, a total of six replicates were collected per condition, two technical over three biological repeats. For stable isotope tracing, a total of four replicates were collected, two biological repeats with two technical replicates. Biological replicates were defined as independent experiments performed using freshly defrosted batches of cells.

The extraction protocol is a modified version of a method developed in Vowinckel et al.23 and Doppler et al.101 Cell pellets were resuspended in 200μl of LCMS-grade acetonitrile/methanol/water (2:2:1) (Sigma Aldrich) chilled to -20°C and transferred to lysing matrix Y tubes (MP Biomedicals) containing 0.5 mm diameter yttria-stabilized zirconium oxide beads. Extraction blanks were included from this stage, consisting of 200μl of extraction solution. 1nmol of scyllo-inositol (Sigma Aldrich) standard was added to all samples at this stage. Samples were kept on ice and lysed at 4°C. Bead beating was performed at 6.5m/sec for 10 seconds, five times, with 2-min breaks on ice after each round. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged at 12,000rpm for 2 min at 4°C and supernatants were dried for 1–2 h in a SpeedVac Vacuum Concentrator at 30°C. Samples were then stored at -80°C.

Dried extracts were resuspended in -20°C chilled 50μl LCMS-grade chloroform (Sigma Aldrich) and 300ml LCMS-grade methanol:-water (1:1) (Sigma Aldrich). Samples were vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 12,000rpm for 5 min at 4°C. 240μl of upper, polar phase was transferred to GC-MS glass vial inserts for drying, which included two 30μl methanol washes to ensure there was no residual water.

Derivatisation was performed based on published work.51 Samples were resuspended in 20μl of 20mg/ml of freshly dissolved methoxyamine hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich) in pyridine (Sigma Aldrich). Samples were briefly vortexed and centrifuged, and incubated at room temperature overnight (around 15 h). The next day, 20μl of room-temperature N,O-bis(trimetylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide and 1% trimethylchlorosilane (Sigma Aldrich) was added to each sample, followed by a brief vortex and centrifugation.

Metabolites were detected using Agilent 7890B-MS7000C GC-MS as previously described.51 Samples were arranged and processed in random order together with regular hexane washes and metabolite standards (kindly gifted by James I. MacRae, Francis Crick Institute). Splitless injection was performed at 270°C in a 30m + 10m x 0.25mm DB-5MS+DG column (Agilent J&W). Helium was used as the carrier gas. The oven temperature cycle was as follows: 70°C for 2 min, temperature gradient up to 295°C with a rate of 12.5°C/min and gradient up to 350°C at a rate of 25°C/min. The 350°C temperature was held for 3 min. Electron impact ionization mode was used for MS analysis.

Analysis of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics data

Samples were analysed using a combination of MassHunter Workstation (Agilent Technologies) and MANIC, an updated version of the software GAVIN,92 for identification and integration of defined ion fragment peaks. For abundance quantification, integrals, the known amount of scyllo-inositol internal standard (1nmol) and the known abundances in the standardised metabolite mix (kindly gifted by James I. Macrae, Francis Crick Institute) run in parallel to samples were used to calculate an estimated nmol abundance of each metabolite in each sample. When presenting secreted metabolites, abundances of metabolites of interest and glucose were corrected to levels detected in the unconsumed EMM, and the change in levels of metabolites of interest were divided by the concomitant decrease in glucose. The formula used for calculating molar abundances as shown in Equation 1.

13C-glucose stable isotope tracing metabolomics data was analysed using MANIC to extract mass isotopologue ratios of metabolites of interest and percentage of metabolite pool that was labelled with 13C. Glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis in a defined time period was obtained by first identifying the timepoint when the proportion of 13C-labelling increased linearly (1 min), and normalising fractional labelling by the abundance of the total metabolite pool, to quantify the nmol of 13C metabolite generated after a specific time passed since exposure to 13C-glucose. Note that mass isotopologue ratios were obtained before steady state to capture transient isotopologues.

Data generated in metabolomics experiments performed for this study are shown in Data S1. Table S1 lists the nmol abundances of metabolites analysed in the standardised metabolite mix run in parallel to samples in each metabolomics experiment.

| (1) |

Equation 1 - Formula for nmol abundance quantification

MRRF = molar relative response factor; SI = scyllo-inositol (internal standard); met = metabolite to be quantified; mm = standard metabolite mix; int = integrals; s = samples.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical details of experiments, including the number of biological and technical replicates and the dispersion and precision measures can be found in figure legends and methods details. All data were analysed using unpaired t-test statistical analysis, unless indicated otherwise. All plots were generated using Graphpad Prism.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

S. japonicus relies on dihydroxyacetone phosphate reduction to oxidize NADH

Fermenting fission yeasts operate a bifurcated TCA pathway to produce biomass

S. japonicus optimizes glycolysis to generate high ATP levels without respiration

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Oliferenko and Bähler labs for discussions and to M. Yuneva, L. Fets, E. Makeyev, A. Yuen, and E. Pascual Navarro for suggestions on the manuscript. We thank A. Forbes for assistance with generating the pyk1 S. japonicus strain. We are grateful to K. Ishikawa (NCI, U.S.) for the S. japonicus var versatilis, and to M. Bochman (Indiana University, U.S.) and M. Kawamukai (Shimane University, Japan) for S. japonicus wild isolates. Many thanks to J.I. MacRae and J. Ellis (Crick Metabolomics STP) for invaluable training and assistance. S.A. was supported by the Crick-King’s PhD scholarship. Work in S.O.’s lab was supported by the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (CC0102), by the UK Medical Research Council (CC0102), and by the Wellcome Trust (CC0102). This research was funded, in whole or in part, by the Wellcome Trust (103741/Z/ 14/Z; 220790/Z/20/Z) and BBSRC (BB/T000481/1) grants awarded to S.O. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.A. conceived, performed, and interpreted experiments, generated strains, analyzed data, and co-wrote the manuscript; Y.G. generated gpd1Δ and mdh1Δ S. pombe and S. japonicus strains, designed pyk1-A343T S. japonicus, and edited the manuscript; P.R. assisted with analysis of metabolomics experiments and edited the manuscript; J.B. interpreted experiments and edited the manuscript; S.O. conceived and interpreted experiments, and co-wrote and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and Diversity

One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in their field of research or within their geographical location. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

Metabolomics raw data is supplied in Data S1. Other types of raw data will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyse the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Hagman A, Piškur J. A study on the fundamental mechanism and the evolutionary driving forces behind aerobic fermentation in yeast. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosios AM, Vander Heiden MG. The redox requirements of proliferating mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:7490–7498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM117.000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muir A, Vander Heiden MG. The nutrient environment affects therapy. Science. 2018;360:962–963. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäckhed F, Bugianesi E, Christofk H, Dikic I, Gupta R, Mair WB, O’Neill LAJ, Ralser M, Sabatini DM, Tschöp M. The next decade of metabolism. Nat Metab. 2019;1:2–4. doi: 10.1038/s42255-018-0022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane N. How energy flow shapes cell evolution. Curr Biol. 2020;30:R471–R476. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olzmann JA, Fendt SM, Shah YM, Vousden K, Chandel N, Horng T, Danial N, Tu B, Christofk H, Vander Heiden MG, et al. More metabolism! Mol Cell. 2021;81:3659–3664. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verduyn C, Stouthamer AH, Scheffers WA, van Dijken JP. A theoretical evaluation of growth yields of yeasts. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1991;59:49–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00582119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Gulik WM, Heijnen JJ. A metabolic network stoichiometry analysis of microbial growth and product formation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;48:681–698. doi: 10.1002/bit.260480617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Kok S, Kozak BU, Pronk JT, van Maris AJ. Energy coupling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: selected opportunities for metabolic engineering. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:387–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compagno C, Dashko S, Piškur J. In: Introduction to carbon metabolism in yeast. In Molecular Mechanisms in Yeast Carbon Metabolism. Piškur J, Compagno C, editors. Springer; 2014. pp. 1–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeiffer T, Morley A. An evolutionary perspective on the Crabtree effect. Front Mol Biosci. 2014;1:17. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda K, Starzynski C, Mori A, Yanagida M. The critical glucose concentration for respiration-independent proliferation of fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mitochondrion. 2015;22:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malecki M, Bitton DA, Rodríguez-López M, Rallis C, Calavia NG, Smith GC, Bähler J. Functional and regulatory profiling of energy metabolism in fission yeast. Genome Biol. 2016;17:240. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagman A, Säll T, Compagno C, Piskur J. Yeast “makeaccumulate-consume” life strategy evolved as a multi-step process that predates the whole genome duplication. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malina C, Yu R, Björkeroth J, Kerkhoven EJ, Nielsen J. Adaptations in metabolism and protein translation give rise to the Crabtree effect in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112836118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piskur J, Rozpedowska E, Polakova S, Merico A, Compagno C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet. 2006;22:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Bartolomeo F, Malina C, Campbell K, Mormino M, Fuchs J, Vorontsov E, Gustafsson CM, Nielsen J. Absolute yeast mitochondrial proteome quantification reveals trade-off between biosynthesis and energy generation during diauxic shift. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:7524–7535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918216117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amado A, Fernández L, Huang W, Ferreira FF, Campos PRA. Competing metabolic strategies in a multilevel selection model. R Soc Open Sci. 2016;3:160544. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson A, Nielsen J. Metabolic Trade-offs in Yeast are Caused by F1F0-ATP synthase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22264. doi: 10.1038/srep22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luengo A, Li Z, Gui DY, Sullivan LB, Zagorulya M, Do BT, Ferreira R, Naamati A, Ali A, Lewis CA, et al. Increased demand for NAD(+) relative to ATP drives aerobic glycolysis. Mol Cell. 2021;81:691.e6–707.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekker WJC, Jürgens H, Ortiz-Merino RA, Mooiman C, van den Berg R, Kaljouw A, Mans R, Pronk JT. Respiratory reoxidation of NADH is a key contributor to high oxygen requirements of oxygen-limited cultures of Ogataea parapolymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022;22 doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foac007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malecki M, Kamrad S, Ralser M, Bähler J. Mitochondrial respiration is required to provide amino acids during fermentative proliferation of fission yeast. EMBO Rep. 2020;21:e50845. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.12.946111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vowinckel J, Hartl J, Marx H, Kerick M, Runggatscher K, Keller MA, Mülleder M, Day J, Weber M, Rinnerthaler M, et al. The metabolic growth limitations of petite cells lacking the mitochondrial genome. Nat Metab. 2021;3:1521–1535. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00477-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yam C, He Y, Zhang D, Chiam KH, Oliferenko S. Divergent strategies for controlling the nuclear membrane satisfy geometric constraints during nuclear division. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1314–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Y, Oliferenko S. Comparative biology of cell division in the fission yeast clade. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;28:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makarova M, Gu Y, Chen JS, Beckley JR, Gould KL, Oliferenko S. Temporal regulation of lipin activity diverged to account for differences in mitotic programs. Curr Biol. 2016;26:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell JJ, Theriot JA, Sood P, Marshall WF, Landweber LF, Fritz-Laylin L, Polka JK, Oliferenko S, Gerbich T, Gladfelter A, et al. Non-model model organisms. BMC Biol. 2017;15:55. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliferenko S. Understanding eukaryotic chromosome segregation from a comparative biology perspective. J Cell Sci. 2018;131 doi: 10.1242/jcs.203653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu Y, Oliferenko S. Cellular geometry scaling ensures robust division site positioning. Nat Commun. 2019;10:268. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makarova M, Peter M, Balogh G, Glatz A, MacRae JI, Lopez Mora N, Booth P, Makeyev E, Vigh L, Oliferenko S. Delineating the rules for structural adaptation of membrane-associated proteins to evolutionary changes in membrane lipidome. Curr Biol. 2020;30:367–380.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foo S, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Wenk MR, Oliferenko S. Diacylglycerol at the inner nuclear membrane fuels nuclear envelope expansion in closed mitosis. J Cell Sci. 2023;136 doi: 10.1242/jcs.260568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulder CJEA. PhD thesis. Delft University of Technology; 1963. On respiratory deficiency in yeasts. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulder CJ. Anaerobic growth, ergosterol content and sensitivity to a polyene antibiotic, of the yeast Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1971;37:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF02218505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bullerwell CE, Leigh J, Forget L, Lang BF. A comparison of three fission yeast mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:759–768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhind N, Chen Z, Yassour M, Thompson DA, Haas BJ, Habib N, Wapinski I, Roy S, Lin MF, Heiman DI, et al. Comparative functional genomics of the fission yeasts. Science. 2011;332:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1203357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaino T, Tonoko K, Mochizuki S, Takashima Y, Kawamukai M. Schizosaccharomyces japonicus has low levels of CoQ(10) synthesis, respiration deficiency, and efficient ethanol production. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2018;82:1031–1042. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1401914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouwknegt J, Koster CC, Vos AM, Ortiz-Merino RA, Wassink M, Luttik MAH, van den Broek M, Hagedoorn PL, Pronk JT. Class-II dihydroorotate dehydrogenases from three phylogenetically distant fungi support anaerobic pyrimidine biosynthesis. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2021;8:10. doi: 10.1186/s40694-021-00117-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada Y, Arimoto M, Kondo K. Coenzyme Q system in the classification of the ascosporogenous yeast genus Schizosaccharomyces and yeast-like genus Endomyces. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1973;19:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuin A, Gabrielli N, Calvo IA, García-Santamarina S, Hoe KL, Kim DU, Park HO, Hayles J, Hidalgo E. Mitochondrial dysfunction increases oxidative stress and decreases chronological life span in fission yeast. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenfeld E, Beauvoit B, Rigoulet M, Salmon JM. Nonrespiratory oxygen consumption pathways in anaerobically-grown Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidence and partial characterization. Yeast. 2002;19:1299–1321. doi: 10.1002/yea.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenfeld E, Beauvoit B, Blondin B, Salmon JM. Oxygen consumption by anaerobic Saccharomyces cerevisiae under enological conditions: effect on fermentation kinetics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:113–121. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.113-121.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeld E, Beauvoit B. Role of the non-respiratory pathways in the utilization of molecular oxygen by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2003;20:1115–1144. doi: 10.1002/yea.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osburn K, Amaral J, Metcalf SR, Nickens DM, Rogers CM, Sausen C, Caputo R, Miller J, Li H, Tennessen JM, et al. Primary souring: a novel bacteria-free method for sour beer production. Food Microbiol. 2018;70:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu C, Bonaduce MJ, Klar AJ. Defining the epigenetic mechanism of asymmetric cell division of Schizosaccharomyces japonicus yeast. Genetics. 2013;193:85–94. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klar AJ. Schizosaccharomyces japonicus yeast poised to become a favorite experimental organism for eukaryotic research. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3:1869–1873. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.007187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao H, Wang Q, Liu C, Shang Y, Wen F, Wang F, Liu W, Xiao W, Li W. A role for the respiratory chain in regulating meiosis initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2018;208:1181–1194. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.300689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun LL, Li M, Suo F, Liu XM, Shen EZ, Yang B, Dong MQ, He WZ, Du LL. Global analysis of fission yeast mating genes reveals new autophagy factors. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ansell R, Granath K, Hohmann S, Thevelein JM, Adler L. The two isoenzymes for yeast NAD+-dependent glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase encoded by GPD1 and GPD2 have distinct roles in osmoadaptation and redox regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2179–2187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Björkqvist S, Ansell R, Adler L, Lidén G. Physiological response to anaerobicity of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:128–132. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.128-132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nissen TL, Hamann CW, Kielland-Brandt MC, Nielsen J, Villadsen J. Anaerobic and aerobic batch cultivations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants impaired in glycerol synthesis. Yeast. 2000;16:463–474. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000330)16:5<463::AID-YEA535>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacRae JI, Dixon MW, Dearnley MK, Chua HH, Chambers JM, Kenny S, Bottova I, Tilley L, McConville MJ. Mitochondrial metabolism of sexual and asexual blood stages of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Biol. 2013;11:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, Burgess SC, Brunengraber H, Clish CB, DeBerardinis RJ, Feron O, Frezza C, Ghesquiere B, et al. A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Camarasa C, Grivet JP, Dequin S. Investigation by 13C-NMR and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) deletion mutant analysis of pathways for succinate formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during anaerobic fermentation. Microbiology (Reading) 2003;149:2669–2678. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daignan-Fornier B, Valens M, Lemire BD, Bolotin-Fukuhara M. Structure and regulation of SDH3, the yeast gene encoding the cytochrome b560 subunit of respiratory complex II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15469–15472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szeto SSW, Reinke SN, Sykes BD, Lemire BD. Ubiquinone-binding site mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate dehydrogenase generate superoxide and lead to the accumulation of succinate. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27518–27526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malecki M, Bähler J. Identifying genes required for respiratory growth of fission yeast. Wellcome Open Res. 2016;1:12. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.9992.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alves TC, Pongratz RL, Zhao X, Yarborough O, Sereda S, Shirihai O, Cline GW, Mason G, Kibbey RG. Integrated, stepwise, mass-isotopomeric flux analysis of the TCA cycle. Cell Metab. 2015;22:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang J, Cheng J, Sun B, Li H, Wu S, Dong F, Yan X. Untargeted and stable isotope-assisted metabolomic analysis of MDA-MB-231 cells under hypoxia. Metabolomics. 2018;14:40. doi: 10.1007/s11306-018-1338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Antoniewicz MR. A guide to 13C metabolic flux analysis for the cancer biologist. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cimini D, Patil KR, Schiraldi C, Nielsen J. Global transcriptional response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to the deletion of SDH3. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duan L, Cooper DE, Scheidemantle G, Locasale JW, Kirsch DG, Liu X. 13C tracer analysis suggests extensive recycling of endogenous CO2 in vivo. Cancer Metab. 2022;10:11. doi: 10.1186/s40170-022-00287-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sumegi B, McCammon MT, Sherry AD, Keys DA, McAlister-Henn L, Srere PA. Metabolism of [3–13C]pyruvate in TCA cycle mutants of yeast. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8720–8725. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamrad S, Grossbach J, Rodríguez-López M, Mülleder M, Townsend S, Cappelletti V, Stojanovski G, Correia-Melo C, Picotti P, Beyer A, et al. Pyruvate kinase variant of fission yeast tunes carbon metabolism, cell regulation, growth and stress resistance. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:e9270. doi: 10.15252/msb.20199270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.TeSlaa T, Teitell MA. Techniques to monitor glycolysis. Methods Enzymol. 2014;542:91–114. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416618-9.00005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanner LB, Goglia AG, Wei MH, Sehgal T, Parsons LR, Park JO, White E, Toettcher JE, Rabinowitz JD. Four key steps control glycolytic flux in mammalian cells. Cell Syst. 2018;7:49.e8–62.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patra KC, Hay N. The pentose phosphate pathway and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bouzier-Sore AK, Bolaños JP. Uncertainties in pentose-phosphate pathway flux assessment underestimate its contribution to neuronal glucose consumption: relevance for neurodegeneration and aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:89. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Akram M, Shah Ali, Munir N, Daniyal M, Tahir IM, Mahmood Z, Irshad M, Akhlaq M, Sultana S, Zainab R. Hexose monophosphate shunt, the role of its metabolites and associated disorders: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:14473–14482. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bertels LK, Fernández Murillo L, Heinisch JJ. The pentose phosphate pathway in yeasts-more than a poor cousin of glycolysis. Biomolecules. 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/biom11050725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacoby J, Hollenberg CP, Heinisch JJ. Transaldolase mutants in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis provide evidence that glucose can be metabolized through the pentose phosphate pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Turyn J, Schlichtholz B, Dettlaff-Pokora A, Presler M, Goyke E, Matuszewski M, Krajka K, Swierczynski J. Increased activity of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and other lipogenic enzymes in human bladder cancer. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:565–569. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aguilera J, Prieto JA. Yeast cells display a regulatory mechanism in response to methylglyoxal. FEMS Yeast Res. 2004;4:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Viljoen M, van der Merwe M, Subden RE, van Vuuren HJJ. Mutation of Gly-444 inactivates the S. pombe malic enzyme. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Groenewald M, Viljoen-Bloom M. Factors involved in the regulation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe malic enzyme gene. Curr Genet. 2001;39:222–230. doi: 10.1007/s002940100199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Todd BL, Stewart EV, Burg JS, Hughes AL, Espenshade PJ. Sterol regulatory element binding protein is a principal regulator of anaerobic gene expression in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2817–2831. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2817-2831.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harris MA, Rutherford KM, Hayles J, Lock A, Bähler J, Oliver SG, Mata J, Wood V. Fission stories: using PomBase to understand Schizosaccharomyces pombe biology. Genetics. 2022;220 doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyab222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rutherford KM, Harris MA, Oliferenko S, Wood V. JaponicusDB: rapid deployment of a model organism database for an emerging model species. Genetics. 2022;220 doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyab223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perysinakis A, Kinghorn JR, Drainas C. Glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase ammonium-assimilating pathway in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:367–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00369864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sasaki Y, Kojima A, Shibata Y, Mitsuzawa H. Filamentous invasive growth of mutants of the genes encoding ammonia-metabolizing enzymes in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu X, Kim CS, Kurbanov FT, Honzatko RB, Fromm HJ. Dual mechanisms for glucose 6-phosphate inhibition of human brain hexokinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31155–31159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ui M. A role of phosphofructokinase in pH-dependent regulation of glycolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Gen Subj. 1966;124:310–322. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luzia L, Lao-Martil D, Savakis P, van Heerden J, van Riel N, Teusink B. pH dependencies of glycolytic enzymes of yeast under in vivo-like assay conditions. FEBS Journal. 2022;289:6021–6037. doi: 10.1111/febs.16459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]