Abstract

Maintaining and limiting T cell responses to constant antigen stimulation is critical to control pathogens and maintain self-tolerance, respectively. Antigen recognition by T cell receptors (TCRs) induces signalling that activates T cells to produce cytokines and also leads to the downregulation of surface TCRs. In other systems, receptor downregulation can induce perfect adaptation to constant stimulation by a mechanism known as state-dependent inactivation that requires complete downregulation of the receptor or the ligand. However, this is not the case for the TCR, and therefore, precisely how TCR downregulation maintains or limits T cell responses is controversial. Here, we observed that in vitro expanded primary human T cells exhibit perfect adaptation in cytokine production to constant antigen stimulation across a 100,000-fold variation in affinity with partial TCR downregulation. By directly fitting a mechanistic model to the data, we show that TCR downregulation produces imperfect adaptation, but when coupled to a switch produces perfect adaptation in cytokine production. A prediction of the model is that pMHC-induced TCR signalling continues after adaptation and this is confirmed by showing that, while costimulation cannot prevent adaptation, CD28 and 4-1BB signalling reactivated adapted T cells to produce cytokines in a pMHC-dependent manner. We show that adaptation also applied to 1st generation chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells but is partially avoided in 2nd generation CARs. These findings highlight that perfect adaptation limits T cell responses rendering them dependent on costimulation for sustained responses.

Introduction

T cell activation is critical to initiate and maintain adaptive immunity. It proceeds by the recognition of peptide major-histocompatibility complex (pMHC) antigens by T cells using their T cell receptors (TCRs). TCR/pMHC binding induces signalling pathways that can activate T cells to directly kill cancerous or infected cells and to secrete a range of cytokines (1). When T cells are confronted with persistent or constant pMHC antigens, maintaining responses to foreign or altered-self pMHC (in chronic infections and cancers (2)) can be just as important as limiting responses to self pMHC (e.g. adaptive tolerance (3)). Like other surface receptors, the TCR is downregulated from the surface of T cells upon recognition of pMHC ligands (4). Precisely how TCR downregulation controls T cell responses to constant pMHC antigen stimulation remains controversial.

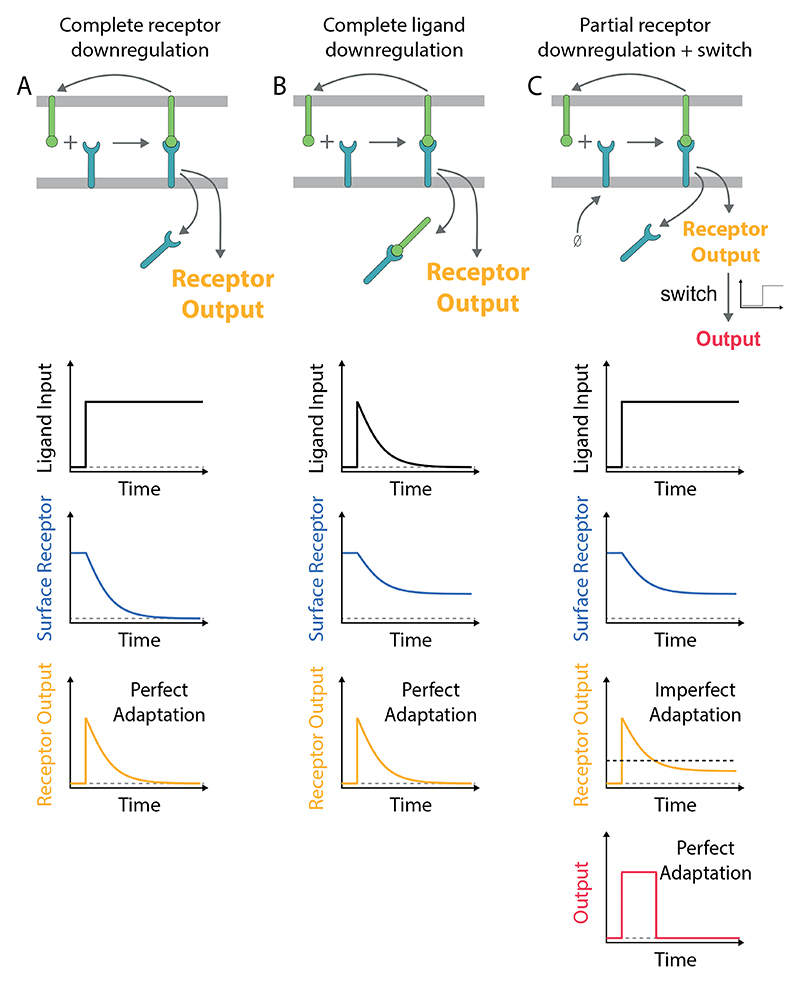

In other cellular systems, receptor downregulation can induce biological adaptation to constant ligand stimulation (5). Adaptation is defined by the ability of a system to display transient responses that return to baseline when presented with constant input stimulation. The process is known as perfect (or near-perfect) when the baselines before and after stimulation are similar and is imperfect otherwise. Systematic network searches have identified two key mechanisms of adaptation; negative feedback loops (NFLs) and incoherent feedforward loops (IFFLs) (6, 7). At a molecular level, these mechanisms are implemented by surface receptors, signalling pathways, and transcriptional networks (5, 8, 9). In the case of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), and ion channels, the common underlying mechanism is effectively an incoherent feedforward termed state-dependent inactivation (5, 7, 9). This mechanism relies on receptors becoming inactivated (i.e. no longer able to signal) after sensing the ligand by, for example, receptor downregulation. Perfect adaptation can be observed when all receptors are downregulated (Fig. 1A) or if all the ligand is removed by the downregulation of receptor/ligand complexes (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of perfect adaptation based on receptor downregulation.

A) Perfect adaptation can be observed if the ligand induces the downregulation of all receptors. This mechanism requires that the re-expression of the receptor on the surface is negligible on the timescale of adaptation. B) Alternatively, perfect adaptation can also be observed with partial receptor downregulation if all ligand is removed by the downregulation of receptor-ligand complexes. This mechanism requires that the receptors are in excess of the ligand (shown) or that receptors are re-expressed on the adaptation timescale (not shown) so that all ligand is removed. C) Receptor output exhibits imperfect adaptation in the model in panel A if the receptor is replenished at the cell surface. In this case, perfect adaptation can be observed if a switch is introduced downstream of the receptor (threshold indicated by dashed horizontal line). In all schematics, the ligand input represents the concentration of ligand available to bind receptor (not including internalised ligand). The mechanism of adaptation by receptor downregulation is a subset of the more general mechanism of state-dependent inactivation (5, 9), which is effectively an incoherent feedforward (7).

The conditions for perfect adaptation exhibited by other receptors are not readily applicable to the TCR. First, the complete downregulation of the TCR is not commonly observed nor is it required for T cell activation (10–14). Second, the complete removal of the pMHC ligand has not been reported although there are reports that some pMHC can be internalised by T cells (15). Instead, individual pMHC ligands have been shown to serially engage and downregulate many TCRs (16) and, on the timescale of hours, they can sustain TCR signalling to induce digital cytokine production (17).

Although TCR downregulation does not appear to meet the criteria for perfect adaptation, it has been suggested to play an important physiological role in peripheral tolerance (18–22). This concept is supported by studies showing that defects in TCR downregulation lead to hyper-responsive T cells with a loss of tolerance to persistent self-antigens resulting in autoimmune phenotypes (23–27) and that this is associated with sustained early TCR signalling (28, 29). However, studies where transgenic mice were challenged with peripheral antigens came to inconsistent conclusions, with some investigators reporting near-complete TCR downregulation as the mechanism of tolerance (20, 30–33), while others concluded that TCR downregulation did not play a role in tolerance because overt downregulation was not observed (34–38). Therefore, it would seem that complete TCR downregulation is not necessary for adaptation tolerance (3).

Maintaining T cell responses is critical in adoptive therapies where T cells, produced by in vitro expansion, are transferred into cancer patients and migrate into tumour microenvironments with chronic cancer antigens (39). These T cells are often armed with affinity-enhanced TCRs or synthetic chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that re-direct them to tumour cell antigens. Similarly to TCRs, CARs are downregulated as a function of antigen concentration and T cells with lower CAR surface expression are less responsive (40–44). How CAR and TCR down-regulation shapes the response of these clinically relevant T cells is poorly understood.

Here, we investigated how constant antigen stimulation regulates responses of clinically relevant in vitro expanded primary human CD8+ T cells. We observed perfect (or near perfect) adaptation in cytokine production over a 100,000-fold variation in antigen affinity with partial TCR downregulation. Mathematical modelling shows that TCR downregulation produces imperfect adaptation, but when coupled to a switch, leads to perfect adaptation. This model predicts that TCR downregulation reduces, but does not abolish, TCR signalling below the threshold for sustained cytokine production. Consistent with this prediction, we show that CD28 and 4-1BB co-stimulation reactivates T cell cytokine production in a pMHC-dependent manner. Lastly, we show that adaptation is partially avoided in CAR-T cells that incorporate costimulation within the synthetic receptor. Therefore, adaptation can severely limit the production of cytokines in adoptive transfer therapies and have important implications for the design of adaptation-resistant TCR and CAR constructs.

Results

Perfect adaptation of T cell responses to constant antigen over large variation in concentration and affinity

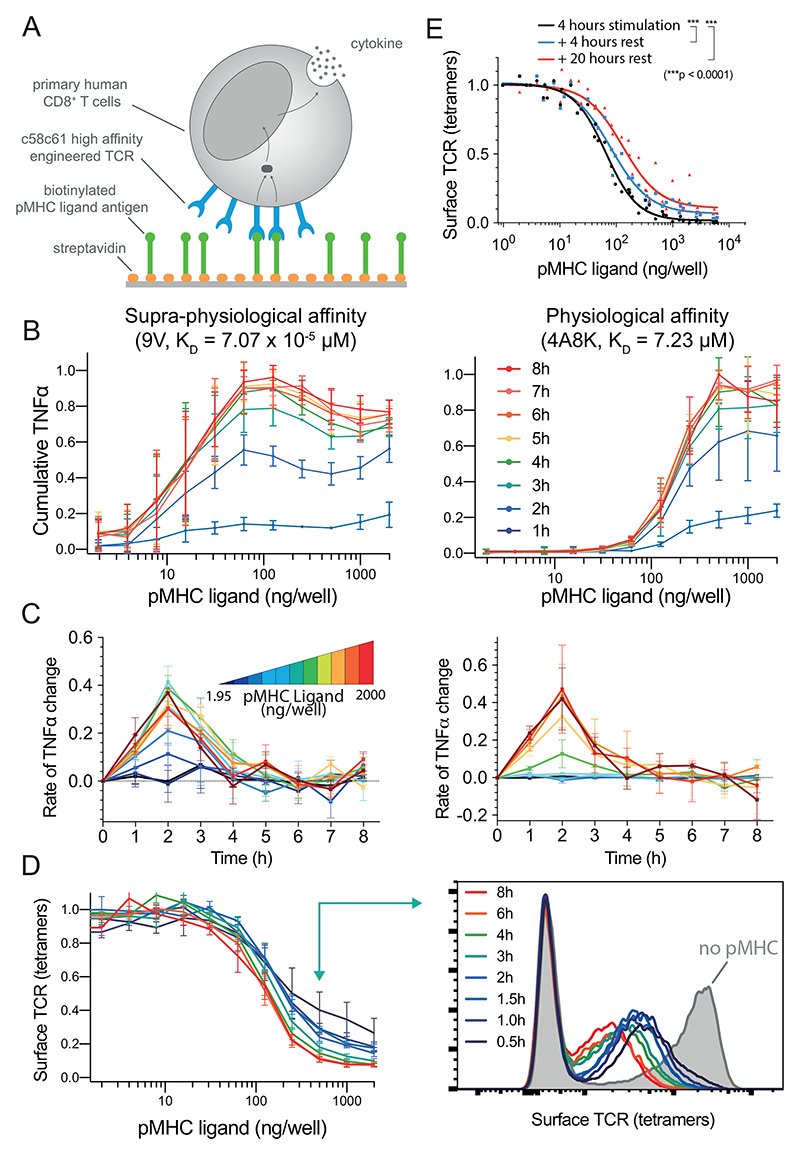

Using a standard adoptive therapy protocol (45), we generated in vitro expanded primary human CD8+ T cells expressing the therapeutic affinity-enhanced c58c61 TCR (46), which recognises the NY-ESO-1157-165 cancer testes antigen peptide bound to HLA-A2 (Fig. 2A, Materials & Methods). In order to allow for constant antigen presentation and to isolate its effects, T cells were stimulated by recombinant pMHC ligands on plates (47–49). This system has been widely used to isolate the effects of specific ligands and to precisely control the duration of stimulation (50).

Figure 2. Perfect adaptation of T cells to constant pMHC ligand stimulation over large variation in affinity and concentration.

A) Primary human CD8+ T cells expressing the c58c61 TCR were stimulated using recombinant pMHC immobilised on plates with supernatant cytokine and surface TCR levels measured (see Materials & Methods). B) Cumulative TNF-α over the concentration of 9V (left) or 4A8K (right) pMHC for 1-8 hours. Mean and SD of 3 independent repeats. C) Data in panel B expressed as a rate of change of cumulative TNF-α. D) Surface TCR expression measured using pMHC tetramers in flow cytometry for 4A8K (left) with a representative histogram (right). Mean and SD of 3 independent repeats. Downregulation could also be observed with TCR antibodies (Fig. S4). E) Recovery of surface TCR was measured by stimulating T cells for 4 hours to induce downregulation (black line) followed by transfer to empty plates without pMHC for 4 (blue) or 20 (red) hours before measuring surface TCR levels with pMHC tetramers. Expanded data showing MIP-1β, IFN-γ, and IL-2 along with raw data prior to averaging are summarised in Fig. S1-2 and single-cell intracellular cytokine staining in Fig. S3.

T cells stimulated by the high-affinity pMHC antigen (9V, KD= 70.7 pM) exhibited perfect adaptation with the secreted supernatant levels of TNF-α stabilising by ~4 hours (Fig. 2B-C, left column). This adaptation was observed at all antigen concentrations tested. Within this range, high concentrations induced an earlier decline in the rate of TNF-α secretion starting at 2 hours. This resulted in a bell-shaped dose-response curve, which has been previously observed in this system (47) and in other experimental systems (51).

Given that this adaptation was observed with a supra-physiological antigen affinity, we could not exclude the possibility that it was an uncharacteristic response to an excessive antigen signal. We therefore repeated the experiment with a physiological affinity pMHC (4A8K, KD= 7.23 μM). Although a higher concentration was required to initiate TNF-α production, the adaptation phenotype was kinetically identical (Fig. 2B-C, right column). We also observed the adaptation phenotype for IL-2, MIP-1β, and IFN-γ (Fig. S1-2), with IFN-γ exhibiting more variability but showing adaptation in transfer experiments discussed below (Fig. S9). This distinct behaviour for IFN-γ could result from a subset of T cells being pre-programmed to produce IFN-γ after initially producing TNF-α (52).

The constant level of supernatant cytokine may be established by a balance of uptake with continued secretion, by a stop in secretion, or a combination of both. Using single-cell intracellular cytokine staining, we observed that fewer T cells stained positive for TNF-α beyond 3 hours (Fig. S3) suggesting that production stops, consistent with a recent report (53). Moreover, continued secretion would predict that replacing the media would lead to detection of additional cytokine as the constant level of supernatant cytokine is restored but this was not observed in transfer experiments discussed below (e.g. Fig. 4C-D, transfer to pMHC & Fig. S7,S9). Collectively, this suggests that cytokine production stops in response to constant pMHC stimulation.

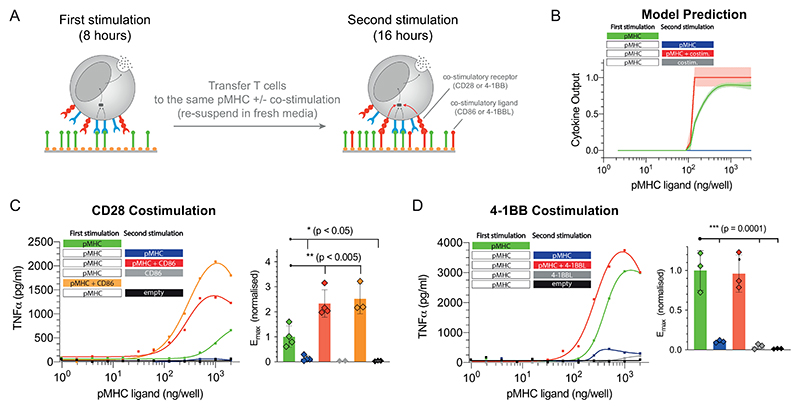

Figure 4. Adapted T cells can be reactivated by CD28 or 4-1BB costimulation.

A) Schematic of the experiment showing that T cells were first stimulated for 8 hours before being transferred for a second stimulation for 16 hours with either antigen alone, costimulation alone, or antigen and costimulation. B) Predicted cytokine production by the mathematical model where costimulation is assumed to lower the threshold for the downstream switch. C) Representative TNF-α production when providing costimulation to CD28 by recombinant biotinylated CD86 and averaged Emax values with SD from 4 independent experiments. D) Representative TNF-α production when providing costimulation to 4-1BB by recombinant biotinylated trimeric 4-1BBL and averaged Emax values with SD from 3 independent experiments. Expanded data showing additional cytokines and TCR downregulation are shown in Fig. S7-9. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons by Dunnett’s test.

Activation-induced cell death may also result in reduced cytokine production but this is unlikely to be the case here. First, we previously confirmed that cell death is minimal in this experimental system (less than 10% of T cells stain positive for Annexin V at 8 hours) (47) and second, adapted T cells can be fully reactivated with co-stimulation (see below; Fig. 4C-D, transfer to pMHC + CD86 or 4-1BBL).

Taken together, perfect adaptation in cytokine production is observed with similar temporal kinetics across a 2,000-fold variation in antigen concentration and a 100,000-fold variation in antigen affinity.

Perfect adaptation cannot be explained by complete TCR or pMHC downregulation

Previously, it has been shown that complete receptor downregulation can produce perfect adaptation provided that the receptor is not re-expressed on the surface on the adaptation timescale (Fig. 1A). We therefore examined the surface dynamics of the TCR in our experimental system using flow cytometry. Consistent with previous reports (16, 18, 54–56), we observed concentration-dependent TCR downregulation that reached steady-state within ~3-6 hours (Fig. 2D). In all conditions tested, the TCR was only partially downregulated and this was not a result of a fraction of T cells downregulating their TCR (i.e. digital downregulation) because histograms showed the entire population of TCR-transduced T cells reducing their TCR surface expression (i.e. analogue downregulation, see Fig. 2D). Consistent with previous reports (18, 57), we observed a small but significant recovery in TCR surface expression on the timescale of ~4 hours (Fig. 2E, compare black to blue line) suggesting that partial downregulation is maintained by a balance of re-expression. Taken together, perfect adaptation cannot be explained by complete downregulation of the TCR.

It has also been shown that complete removal of the ligand can produce perfect adaptation (Fig. 1B). As already discussed, the efficient removal of all pMHC ligands is not known to take place during T cell activation with previous reports showing that pMHC ligands continually engage TCRs (16, 17). Indeed, the removal of pMHC is unlikely to be the mechanism in this experimental system because transferring T cells after they have adapted to plates newly coated with pMHC did not reactivate them to produce cytokine (see below; Fig. 4C-D, transfer to pMHC). Taken together, perfect adaptation by T cells cannot be explained by complete TCR or pMHC downregulation.

Perfect adaptation by imperfect adaptation at the TCR coupled to a downstream switch

Given that up-regulation of the TCR can be observed on the adaptation timescale suggests that TCR downregulation would lead to imperfect adaptation (Fig. 1C). Therefore, additional mechanism(s) are required to produce perfect adaptation in cytokine production. Given that switches have been extensively documented in the TCR signalling pathways (17, 58–60) and that digital cytokine production has been reported (17), we hypothesised that a downstream switch could convert imperfect adaptation at the TCR into perfect adaptation in cytokine production (Fig. 1C).

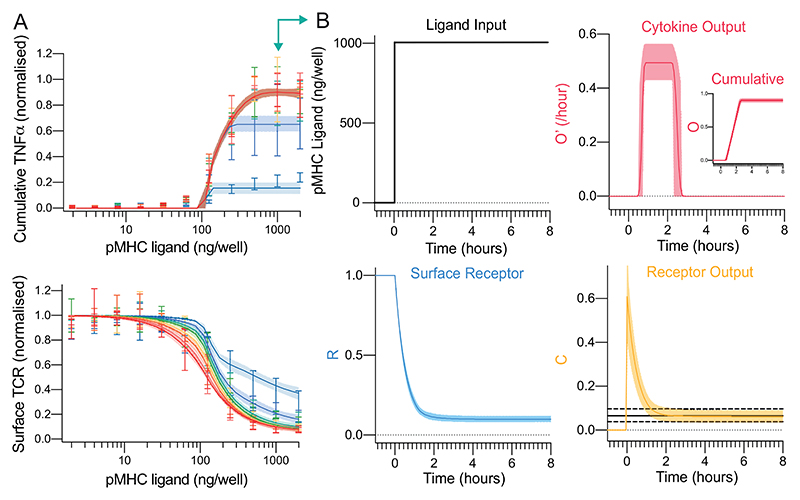

We converted the schematic (Fig. 1C) into an ordinary-differential-equation (ODE) model and used Approximate Bayesian Computations coupled to Sequential Monte Carlo (ABC-SMC) (61) to directly fit the model to the surface TCR and cytokine data (see Materials & Methods). Given that the experimental data is derived from a heterogeneous population of T cells, the ABC-SMC method is particularly appropriate because it effectively simulates a population of T cells with potentially different values of the model parameters representing population heterogeneity (Fig. S5).

The model produced an excellent fit to the data (Fig. 3A, solid lines) indicating that partial TCR downregulation coupled to digital cytokine production is sufficient to explain perfect adaptation. By examining the timecourse at a single concentration (Fig. 3B), it was observed that incomplete TCR downregulation (R, surface TCR) led to imperfect adaptation in TCR/pMHC complexes (C, receptor output). Perfect adaptation in cytokine production (O, output) was observed in the model because the concentration of TCR/pMHC complexes decreased below the switch threshold required to maintain the output.

Figure 3. A mechanistic mathematical model shows that TCR downregulation coupled to a downstream switch is sufficient to explain perfect adaptation in T cell cytokine production to constant pMHC ligand stimulation.

A) The fit of the mathematical model (Fig. 3C) using ABC-SMC to the physiological affinity pMHC data (Fig. 2B,D) with solid line and shaded region indicating the mean and 95% CI of the fit. B) Model outputs over time for a single concentration (1000 ng/well, teal arrow in panel A). The solid and dashed horizontal black lines in receptor output (bottom right) indicate the fitted mean threshold and 95% confidence intervals, respectively, for the downstream switch. Distributions of all fitted parameters can be found in Fig. S5.

This mechanism predicts that increasing the antigen strength would induce further TCR downregulation and cytokine production. Therefore, the model was used to predict the outcome of increasing the antigen affinity (Fig. S6) and experiments confirmed that TCR levels tuned to the new antigen strength with further cytokine production. As expected, reducing the antigen strength by reducing antigen affinity did not lead to marked changes in TCR expression or further cytokine production (Fig. S6D, light purple line showing transfer from high-affinity to low-affinity).

In summary, and in contrast to adaptation by other receptors, perfect adaptation can be explained here by imperfect adaptation at the TCR by partial downregulation coupled to a switch in the pathway for cytokine production (Fig. 1C).

T cell adaptation to constant pMHC antigen can be overridden by costimulation

The model predicted imperfect adaptation by TCR downregulation so that residual TCR output continued after cytokine production had stopped (Fig. 3B). Given that T cells can encounter antigen in vivo with costimulation through other surface receptors, and costimulation is thought to lower the signalling threshold for cytokine production (62–64), we determined whether costimulation can amplify residual TCR signalling to reactivate adapted T cells.

We used the mathematical model to predict the outcome of transferring T cells from a first stimulation to a second stimulation on the same antigen with or without costimulation (Fig. 4A). Note that in these transfer experiments, T cells experience the same concentration of antigen in the first and second stimulation. The effect of costimulation was simulated by lowering the switch threshold and as expected, this allowed T cells to produce cytokine provided they also continued to receive constant antigen stimulation (Fig. 4B). We note that similar results are obtained if co-stimulation acts to increase TCR signalling but not if co-stimulation acts after the switch.

In order to test whether CD28 costimulation could override adaptation, we stimulated T cells with the physiological affinity pMHC (first stimulation) before transferring them to the same titration of pMHC with or without recombinant CD86, which is the ligand for CD28 (second stimulation). Consistent with the adaptation phenotype, there was a dramatic reduction in TNF-α production in the second stimulation without CD86 but when CD86 was present, strong cytokine production was observed (Fig. 4C). Importantly, T cells transferred to empty wells without pMHC or to wells coated with only CD86 produced no cytokines. In addition to CD28, the costimulatory receptor 4-1BB is also known to play an important role in the activation of CD8+ T cells. We repeated the experiments with the recombinant ligand to 4-1BB showing that this TNFR is also able to override adaptation but as with CD28, it critically relied on TCR/pMHC interactions (Fig. 4D). Co-stimulation through both CD28 and 4-1BB did not result in increased TCR surface expression (Fig. S8).

Previous work on T cell anergy has described unresponsive T cell states that are induced when T cells are activated in the absence of CD28 costimulation. We therefore tested whether CD28 costimulation can prevent adaptation. We repeated the CD28 costimulation transfer experiments but now transferred T cells that were stimulated with either pMHC alone or with both pMHC and CD86 in the first stimulation to a second stimulation that included pMHC alone, CD86 alone, pMHC and CD86, or empty wells. We observed reduced cytokine production in the second stimulation to pMHC alone, which was similar to empty wells, irrespective of whether CD86 was included in the first stimulation (Fig. S9), suggesting that CD28 costimulation cannot prevent adaptation to constant antigen.

Taken together, these results indicate that perfect adaptation in cytokine production induced by constant pMHC antigen stimulation does not lead to perfect adaptation in TCR signalling because extrinsic costimulation through CD28 or 4-1BB can induce adapted T cells to produce TNF-α in a pMHC-dependent manner. This phenotype was also observed for other cytokines (Fig. S7-9).

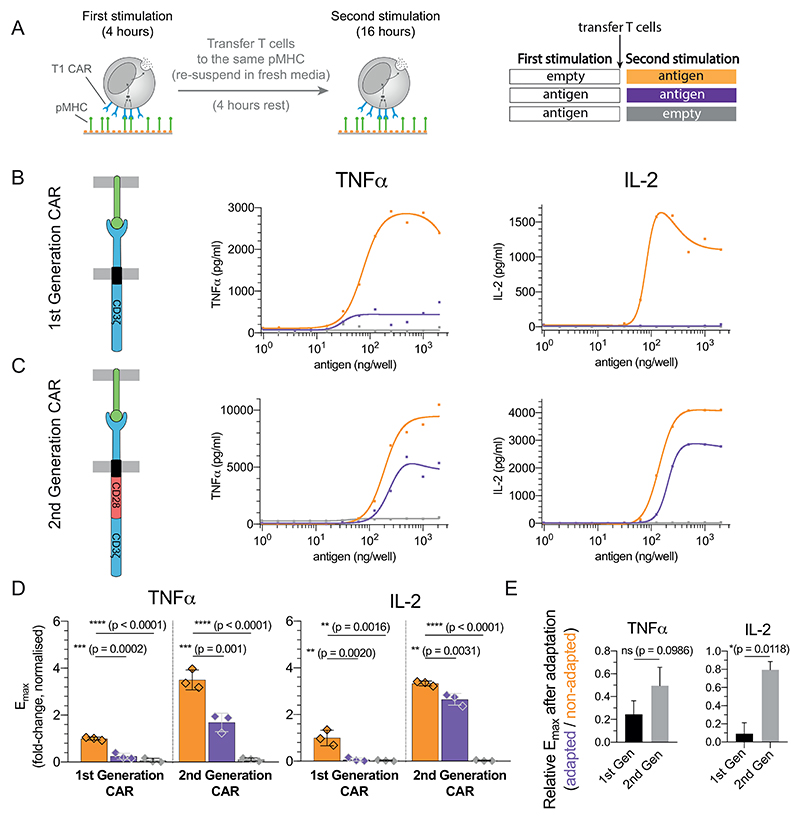

Adaptation by CAR-T cells to constant antigen can be overridden by costimulatory domains

Given that CAR-T cells experience constant antigen stimulation in vivo, we analysed their adaptation phenotype. To do this, we utilised the previously described T1 CAR (65) fused to the cytoplasmic tail of the ζ-chain (1st generation CAR) that also recognises the NY-ESO-1157−165 peptide on HLA-A2 in a similar orientation to the TCR (KD= 4 nM (66)). These CAR-T cells were first stimulated with a titration of 9V pMHC before being transferred for a second stimulation on the same titration of 9V (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Adaptation is partially avoided in 2nd but not 1st generation CAR-T cells.

A) Schematic of the experiment. T cells expressing the T1 CAR that recognises the 9V pMHC antigen were transferred to the same titration of antigen. B-C) Representative TNF-α and IL-2 production over antigen concentration from CAR-T cells expressing the B) the 1st generation variant containing only the ζ-chain and C) the 2nd generation variant containing the cytoplasmic tail of CD28 fused to the ζ-chain. D) Averaged Emax values and SD for 3 independent experiments. E) Fold reduction of Emax between the first and second stimulation for the 1st and 2nd generation CARs highlighting that 2nd generation CARs are more resistant to adaptation induced by constant antigen. Expression profile of both CARs and antigen-induced CAR downregulation is shown in Fig. S10. Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons by Dunnett’s test.

We observed reduced cytokine production by CAR-T cells that experienced the antigen in the first stimulation compared to CAR-T cells that were directly placed on the second stimulation (Fig. 5B, purple and orange lines, respectively). Given that costimulation can override adaptation, we repeated the experiments with a 2nd generation CAR containing the CD28 costimulatory domain finding that these CAR-T cells were able to partially avoid adaptation (Fig. 5C). Compared to cytokine production in the 1st stimulation (100%), the production of TNF-α and IL-2 were reduced in the second stimulation to 26% (p=0.0002) and 2.1% (p=0.002) in the 1st Generation CAR but were only reduced to 58.7% (p=0.001) and 79% (p=0.0031) in the 2nd generation CAR (Fig. 5D-E). The ability of the 2nd generation CAR to resist adaptation was not a result of higher expression or an ability to resist downregulation since this CAR was consistently expressed at lower levels and downregulated to similar levels compared to the 1st generation CAR (Fig. S10).

Taken together, the adaptation phenotype observed with the TCR can also be observed with a 1st generation CAR that can be partially overridden by a 2nd generation CAR that includes costimulation. Partial rescue in the 2nd generation CAR is not unexpected because, unlike the complete rescue of the TCR by extrinsic co-stimulation (Fig. 4), co-stimulation in the CAR is intrinsic and is therefore reduced over time as a result of CAR downregulation.

Discussion

Using a reductionist system to provide T cells with constant pMHC antigens, we observed that in vitro expanded primary human CD8+ T cells do not maintain cytokine production but instead exhibit perfect adaptation across a 100,000-fold variation in affinity. Their responses can be rescued by higher antigen affinity (Fig. S6) or by co-stimulation (Fig. 4).

Mechanism of adaptation

Adaptation by surface receptors has been termed state-dependent inactivation (5, 9), which is an incoherent feedforward loop whereby ligand binding induces receptor signalling (positive regulation) and receptor downregulation (negative regulation) (7). Perfect adaptation takes place if the receptor is completely inactivated or downregulated by the ligand. Unlike other receptors, the TCR is only partially downregulated leading to imperfect adaptation. To explain perfect adaptation in cytokine production, an additional downstream mechanism is required, and in the present study we have invoked a switch (Fig. 1C). However, other signalling modules, such as additional IFFLs or NFLs, can also convert imperfect adaptation at the TCR to perfect adaptation in cytokine production.

The observation that 4-1BB co-stimulation can reactivate adapted T cells suggests that the identity of the additional downstream mechanism is likely to be at the transcriptional level. 4-1BB signalling activates NFκB and MAPK pathways and is not known to interfere with TCR-proximal signalling. Moreover, TCR signalling results in the efficient and sustained nuclear trans-localisation of NFAT through the calcium pathway, whereas its ability to activate AP-1 and NFκB without co-stimulation is relatively poor (67–69). Dependence of sustained cytokine production on these transcription factors suggests that T cells adapted to the pMHC stimulus by downregulating TCR signalling can be reactivated by 4-1BB co-stimulation because it is able to mitigate the lack of active AP-1 and NFκB. Conversely, CD28 co-stimulation can modulate TCR proximal signalling, which may effectively amplify residual TCR signalling to restore the activation of AP-1 and NFκB (70, 71).

The minimal model of TCR downregulation coupled to a downstream switch can produce bell-shaped dose-response curves (e.g. Fig. S6B). Previously, we argued that bell-shaped dose-response curves can be explained by incoherent feedforward loops but not by TCR downregulation (47). The key assumption underlying this conclusion was that the rate of cytokine production was in steady-state, which is the case for Jurkat T cell lines (47), but the detailed analysis in the present work has revealed that it is not the case for primary T cells in the absence of costimulation. The bell-shaped dose-response curve produced by the kinetic model used here is a result of faster TCR downregulation at higher antigen concentrations resulting in cytokine production stopping at an earlier time point.

Function of adaptation

Adaptation is a critically important and widely implemented process in biology. Unlike other receptors, perfect adaptation in T cells is achieved by imperfect adaptation at the TCR. This has the important consequence that adapted T cells are rendered dependent on both antigen and extrinsic costimulation. In the specific example of activated T cells, whose killing capacity is thought to be less dependent on costimulation, adaptation in cytokine production may be an important mechanism to ensure that their ability to initiate or maintain inflammation is extrinsically regulated by other cells. In this way, adaptation may serve to balance functional immunity with excessive tissue damage as previously suggested (3, 72).

Role of TCR downregulation

T cells are known to enter unresponsive states upon recognition of persistent self- and viral-antigens in vivo (2, 3, 20, 31, 33–38, 73–77). While the underlying mechanisms that induce and maintain these states are debated, their functional phenotype is characterised by transient cytokine production that can be overcome by costimulation as observed here (Fig. 2,4). For example, it has been shown that effector CD4+ T cells transiently produce cytokines despite continued antigen exposure (76) and the unresponsive (exhausted) phenotype of CD8+ T cells induced by persistent antigens can be overcome by costimulation (77).

We note that the mechanism of adaptation that we report can take place with only minor TCR downregulation, which may help reconcile previous reports arguing either that TCR downregulation can explain tolerance (20, 30–33) or that TCR downregulation did not play a role in tolerising T cells because overt downregulation was not observed (34–38). Additionally, our results suggest that adaptation by TCR downregulation renders T cells dependent on costimulation, which is in line with the finding that T cells with impaired TCR downregulation lose their dependence on costimulation for activation (25, 27). Ultimately, by studying in vitro-expanded human T cells, we are inherently limited in making direct comparisons with in vivo T cell phenotypes.

Implications for adoptive therapy

The T cells we have used were generated using a protocol for adoptive therapy with TCRs or CARs. Consistent with the adaptation phenotype we observe, it has recently been observed that CAR-T cells exposed to chronic antigen become unresponsive but can respond to a higher antigen dose, which correlates with CAR expression (43). The ability of 2nd generation CARs to partially avoid adaptation in cytokine production (Fig. 5) may explain why they generate much more potent and persistent anti-tumour responses in vivo (78–81) even though their in vitro killing capacity is comparable to 1st generation receptors (79–82). The optimisation of TCRs and CARs has focused on affinity, surface levels, and signalling potency, but engineering for optimal downregulation has yet to be explored.

Materials & Methods

Protein production

pMHCs were refolded in vitro from the extracellular residues 1-287 of the HLA-A*02:01 α-chain, β2-microglobulin and NY-ESO-1157−165 peptide variants as described previously (47). CHO cell lines permanently expressing the extracellular part of human CD86 (amino acids 6-247) with a His-tag for purification and a BirA biotinylation site were kindly provided by Simon Davis (Oxford, UK). Cells were cultured in GS selection medium and passaged every 3-4 days. After 4-5 passages from thawing a new vial, cells from 2 confluent T175 flasks were transferred into a cell factory and incubated for 5-7 days after which the medium was replaced. The supernatant was harvested after another three weeks, sterile filtered and dialysed over night. The His-tagged CD86 was purified on a Nickel-NTA Agarose column. 4-1BB Ligand expression constructs were a kind gift from Harald Wajant (Wuerzburg, Germany) and contained a Flag-tag for purification and a tenascin-C trimerisation domain. We added a BirA biotinylation site. The protein was produced by transient transfection of HEK 293T cells with XtremeGene™ HP Transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and purified following a published protocol (83), with the exception of the elution step where we used acid elution with 0.1 M glycine-HCl at pH 3.5. The pMHC or costimulatory ligand was then biotinylated in vitro by BirA enzyme according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Avidity) and purified using size-exclusion chromatography.

Production of lentivirus for transduction

HEK 293T cells were seeded into 6-well plates 24 h before transfection to achieve 50–80% confluency on the day of transfection. Cells were cotransfected with the respective third-generation lentiviral transfer vectors and packaging plasmids using Roche XtremeGene™ 9 (0.8μg lentiviral expression plasmid, 0.95 μg pRSV-rev, 0.37 μg pVSV-G, 0.95 μg pGAG). The supernatant was harvested and filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter 24-36h later. The 1G4 TCR used for this project was initially isolated from a melanoma patient (84). The affinity maturation to the c58c61 TCR variant used herein was carried out by Adaptimmune Ltd. The TCR and all CARs in this study have been used in a standard third-generation lentiviral vector with the EF1α promoter. The CAR constructs that bind the NY-ESO-1157−165 HLA-A2 pMHC complex (66, 85) were a kind gift from Christoph Renner (Zurich, Switzerland). The high-affinity T1 version was used for this project. All CAR constructs contained the scFv binding domain, a 2 Ig domain spacer derived from an IgG antibody Fc part and the CD28 transmembrane domain. We modified the different CARs to contain the CD3ζ signalling domain alone or in combination with the CD28 signalling domain.

T cell isolation and culture

Up to 50 ml peripheral blood were collected by a trained phlebotomist from healthy volunteer donors after informed consent had been taken. This project has been approved by the Medical Sciences Inter-Divisional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Oxford (R51997/RE001) and all samples were anonymised in compliance with the Data Protection Act. Alternatively, leukocyte cones were purchased from National Health Services Blood and Transplant service. Only HLA-A2- peripheral blood or leukocyte cones were used due to the cross-reactivity of the high-affinity receptors used in this project which leads to fratricide of HLA-A2+ T cells (65, 66, 86). CD8+ T cells were isolated directly from blood using the CD8+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies) and density gradient centrifugation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated CD8+ T cells were washed and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per ml in completely reconstituted RPMI supplemented with 50 units/ml IL-2 and 1 × 106 CD3/CD28-coated Human T-Activator Dynabeads (Life Technologies) per ml. The next day, 1 × 106 T cells were transduced with the 2.5 ml virus-containing supernatant from one well of HEK cells supplemented with 50 units/ml of IL-2. The medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 50 units/ml IL-2 every 2–3 d. CD3/CD28-coated beads were removed on day 5 after lentiviral transduction and the cells were used for experiments on days 10-14. This protocol produces antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells with a fraction (typically ~70%) expressing the transduced c58c61 TCR or T1 CAR.

T cell stimulation

T cells were stimulated with titrations of plate-immobilised pMHC ligands with or without co-immobilised ligands for accessory receptors. Ligands were diluted to the working concentrations in sterile PBS. 50 μl serially two-fold diluted pMHC were added to each well of Streptavidin-coated 96-well plates (15500, Thermo Fisher). After a minimum 45 min incubation, the plates were washed once with sterile PBS. Where accessory receptor ligands were used, those were similarly diluted and added to the plate for a second incubation of 45-90 min. In experiments with small molecule inhibitors, the T cells were incubated with the inhibitor at 37 °C for 20-30 min prior to the start of the stimulation. The inhibitors were left in the medium for the whole duration of the stimulation. All control conditions were incubated with DMSO at a 1:1000 dilution so that the DMSO concentration was the same for inhibitor and non-inhibitor samples. PP2 was used at a 20 μM concentration. After washing the stimulation plate with PBS, 7.5 × 104 T cells were added in 200 μl complete RPMI without IL-2 to each stimulation condition. The plates were spun at 9 x g for 2 min to settle down the cells and then incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. For transfer experiments, the T cells were pipetted from the stimulation plate into a V-bottom plate and pelleted after the first round of stimulation. The supernatant was stored at -20 °C for later cytokine ELISAs, the cells were resuspended in 200 μl fresh R10 medium and – depending on the experiment – either rested for some time or transferred to another stimulation plate with a new set of conditions. The cells were then again settled down by centrifuging at 9 x g before incubation.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to assess receptor expression after TCR and CAR transductions, and to quantify receptor downregulation at the end of stimulation experiments. After stimulation, T cells were pelleted in a V-bottom plate and resuspended in 40 μl PBS with 2% BSA and fluorescent 9V pMHC tetramers that were produced with Streptavidin-PE (Biolegend, 405204) and used at a predetermined dilution (1:100-1:1000). The staining was incubated for 20-60 min after which the cells were pelleted, resuspended in 70-100 μl PBS and analysed on a FACSCalibur™ or LSRFortessa X-20 (BD) flow cytometer. Flow cytometry data was analysed with Flowjo V10.0.

ELISA

Supernatants from stimulation experiments were stored at -20 °C. Cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISAs according to the manufacturer’s instructions in Nunc MaxiSorp™ flat-bottom plates (Invitrogen) using Uncoated ELISA Kits (Invitrogen) for TNF-α, IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and IL-2.

Data analysis

The fraction of T cells expressing the transduced TCR or CAR and the amount of supernatant cytokine exhibited variation between independent experiments (with different donors). Therefore, directly averaging the data produced curves that were not representative of individual repeats. To average cytokine data, the maximum for each repeat was normalised to 1 before averaging independent repeats. To average surface TCR gMFI (X), which is on a logarithmic scale, we used the following formula that corrected for the fraction of T cells expressing the , where X0 is the mean background gMFI of the TCR negative population. After applying this transform, each repeat was normalised to the maximum gMFI before averaging independent repeats.

The statistical analysis of maximum cytokine produced across different pMHC concentrations (Emax), was performed by expressing Emax as a fold-change to pMHC alone before averaging independent repeats. Given that the dose-response curves often exhibited a bell-shape, it was not possible to use a standard Hill function to estimate Emax. Instead, we used lsqcurvefit in Matlab (Mathworks, MA) to fit a function that was the difference of two Hill curves in order to generate a smooth spline through the data from which the maximum value of cytokine was estimated. This procedure was used to extract Emax values in Fig. 4, 5, S7, S9. In a limited number of cases, individual outlier values were excluded prior to data fitting but are still shown as data points in respective figures.

Statistical analysis

Ordinary one-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons by Dunnett’s test was performed on experimental data to determine statistical significance levels (Fig. 4C,D, Fig. S6C, Fig. 5D,E, Fig. S9). Statistical significance for surface TCR recovery (Fig. 2E) was performed by using an F-test for the null hypothesis that a single Hill curve (with the same parameters) can explain the data. GraphPad Prism was used for all statistical analyses.

Mathematical model

The mathematical model (Fig. 1C) is represented as a system of two non-linear coupled ordinary-differential-equations (ODEs),

where R and O are the surface TCR levels (normalised to 1) and cumulative cytokine output with initial conditions 1 and 0, respectively. Given that TCR/pMHC binding kinetics (seconds) are faster than experimental timescales (hours), the concentration of TCR/pMHC complexes (C, defined as receptor output) were assumed to be in quasi steady-state, , where L is the given concentration of pMHC (in ng/well), K0 is the effective dissociation constant (in ng/well), and n is the Hill number. In the equation for R, the first two terms are the basal turnover of surface TCR (k1(1 − R)) and the pMHC binding induced downregulation of TCR (−k3C). In the equation for O, the term for the switch (k4H(C − K4)) includes a heaviside step function (H), so that the term is 0 unless receptor output (C) is above the switch threshold (K4), and in this case, cytokine output is produced at rate k4.

To directly fit the model to the data, two additional modifications were required. First, TCR downregulation is biphasic in time (55, 57) (e.g. Fig. 2D) requiring an additional term for downregulation in the equation for R (k2H(C − K2)R). This term increases TCR downregulation initially when the output from the receptor (C) is above a threshold (K2) and at a molecular level, this may represent signalling-dependent bystander downregulation (13). Given that the model already contained a stiff step-function in the equation for O, this step-function was approximated by a Hill number with large cooperativitiy for computational efficiency (, s = 12). Second, cytokine production was larger in the 2nd hour compared to the 1st hour (e.g. Fig. 2B), which may be associated with transcriptional delays. To capture this delay, a multiplicative term in the equation for O was introduced (H(t − tdelay)) so that cytokine production was only initiated after a delay of tdelay.

Data fitting using ABC-SMC

A Matlab (Mathworks, MA) implementation of a previously published algorithm for Approximate Bayesian Computation coupled to Sequential Monte Carlo (ABC-SMC) was used for data fitting (61). The ODEs were evaluated using the Matlab function ode23s.

Using ABC-SMC, the values of R(t) and O(t) were directly fitted to the normalised surface TCR levels and cumulative cytokine output, respectively, for the dose-response timecourse of 4A8K (192 data points in total). The distance measure was the standard sum-squared-residuals (SSR) and all 9 model parameters were fitted (K0, n, k1, k2, K2, k3, k4, K4, tdelay). A population of 3000 particles were initialised with uniform priors in log-space and propagated through 30 populations by which point the distance measure was no longer decreasing. The final population of 3000 particles, each of which had a different set of model parameters (Fig. S5), was used to display the quality of the fit (Fig. 3A). Although the ODE model represents the reactions within a single cell, and hence the dose-response curve for a single cell would exhibit a perfect switch (i.e. a step function), the population averaged dose-response curves from the model include particles (i.e. cells) with different parameter values, accounting for population heterogeneity, leading to a more gradual dose-response curve.

The posterior distributions revealed that only a subset of the model parameters were uniquely determined (Fig. S5). Nonetheless, we were still able to make predictions using the model by simulating different experimental conditions for the 3000 particles in the final population. To predict the effect of increasing antigen affinity (Fig. S6B), the TCR/pMHC binding parameters in the model (K0 and n) for each particle were reduced by 50%. To predict the effect of co-stimulation (Fig. 4B), the threshold for the switch (K2) for each particle was reduced by 60% for a duration of 8 hours. The value of 60% was chosen as it approximately reproduced EC50 ~ 100 ng/well observed in the data. The duration of this reduction scaled the value of Emax with 8 hours producing a value more similar to the 4-1BB and 16 hours producing a value more similar to the CD28 (not shown).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Simon J. Davis for providing CD86 expression plasmids, Harald Wajant for providing 4-1BBL expression plasmids, Christopher Renner for providing T1 CAR plasmids, Alan Rendall, and Vahid Shahrezaei for feedback on mathematical modelling, Adaptimmune Ltd for providing the c58c61 TCR, and Enas Abu Shah, Michael L. Dustin, Marion H. Brown, and Vincenzo Cerundolo for helpful discussions about experimental protocols. We thank P. Anton van der Merwe for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Doctoral Training Centre Systems Biology studentship from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (to NT), a scholarship from the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (to NT), a studentship from the Edward Penley Abraham Trust and Exeter College, Oxford (to PK), a postdoctoral extension award from the Cellular Immunology Unit Trust (to PK), a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (098363, to OD), pump-prime funding from the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre Development Fund (CRUKDF 0715, to OD), National Science Foundation (USA) grant (1817936, to EDS) and a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (207537/Z/17/Z, to OD).

Footnotes

Author contributions. NT, PK, SG, JN, and JP performed experiments; NT, PK, and OD performed the mathematical modelling; NT, PK, SG, JN, JP, and OD analysed data; NT, PK, and OD designed the research and wrote the paper; NT, PK, and SG contributed equally. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

References

- 1.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky Ga, Jordan MS. T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashimoto M, et al. CD8 T Cell Exhaustion in Chronic Infection and Cancer: Opportunities for Interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2018:301–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012017-043208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcover A, Alar B, Bartolo VD. Cell Biology of T Cell Receptor Expression and Regulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:85–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrell JE. Perfect and near-perfect adaptation in cell signaling. Cell Systems. 2016;2:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma W, Trusina A, El-Samad H, Lim WA, Tang C. Defining Network Topologies That Can Achieve Biochemical Adaptation. Cell. 2009;138:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahi SJ, et al. Oscillatory stimuli differentiate adapting circuit topologies. Nature Methods. 2017;14:1010–1016. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankaran H, Resat H, Wiley HS. Cell surface receptors for signal transduction and ligand transport: A design principles study. PLoS Computational Biology. 2007;3:0986–0999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedlander T, Brenner N. Adaptive response by state-dependent inactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:22558–22563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902146106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T Cell Activation Determined by T Cell Receptor Number and Tunable Thresholds. Science (80- 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Z, et al. Requirements for Peptide-Induced T Cell Receptor Downregulation on Naive CD8 T Cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:641–652. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salio M, Valitutti S, Lanzavecchia A. Agonist-Induced T Cell Receptor Down-Regulation: Molecular Requirements and Dissociation from T Cell Activation. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1769–1773. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.San Jose E, Borroto A, Niedergang F, Alcover A, Alarcón B. Triggering the TCR complex causes the downregulation of nonengaged receptors by a signal transduction-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 2000;12:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monjas A, Alcover A, Alarcón B. Engaged and bystander T cell receptors are down-modulated by different endocytotic pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J. TCR-Mediated Internalization of Peptide-MHC Complexes Acquired by T Cells. Science. 1999;286:952–954. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valitutti S, et al. Serial Triggering of Many T-Cell Receptors by a Few Peptide-Mhc Complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, et al. A Single peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligand triggers digital cytokine secretion in CD4+ T Cells. Immunity. 2013;39:846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinherz EL, et al. Antigen recognition by human T lymphocytes is linked to surface expression of the T3 molecular complex. Cell. 1982;30:735–743. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanders ED, Lamb JR, Feldmann M, Green N, Beverley PC. Tolerance of T-cell clones is associated with membrane antigen changes. Nature. 1983;303:625–627. doi: 10.1038/303625a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schönrich G, et al. Down-regulation of T cell receptors on self-reactive T cells as a novel mechanism for extrathymic tolerance induction. Cell. 1991;65:293–304. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90163-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Čemerski S, et al. The Balance between T Cell Receptor Signaling and Degradation at the Center of the Immunological Synapse Is Determined by Antigen Quality. Immunity. 2008;29:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallegos AM, et al. Control of T cell antigen reactivity via programmed TCR downregulation. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:379–386. doi: 10.1038/ni.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy MA, et al. Tissue Hyperplasia and Enhanced T-Cell Signalling via ZAP-70 in c-Cbl-Deficient Mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4872–4882. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naramura M, Kole HK, Hu RJ, Gu H. Altered thymic positive selection and intracellular signals in Cbl-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1998;95:15547–15552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmaier K, et al. Negative regulation of lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity by the molecular adaptor Cbl-b. Nature. 2000 doi: 10.1038/35003228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeon MS, et al. Essential Role of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Cbl-b in T Cell Anergy Induction. Immunity. 2004;21:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurieva RI, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase GRAIL regulates T cell tolerance and regulatory T cell function by mediating T cell receptor-CD3 degradation. Immunity. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KH, et al. The Immunological Synapse Balances T Cell Receptor Signaling and Degradation. Science (80-) 2003;302:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1086507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naramura M, et al. c-Cbl and Cbl-b regulate T cell responsiveness by promoting ligand-induced TCR down-modulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1192–1199. doi: 10.1038/ni855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferber I, et al. Levels of peripheral T cell tolerance induced by different doses of tolerogen. Science. 1994;263:674–676. doi: 10.1126/science.8303275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tafuri A, Alferink J, Möller P, Hämmerling GJ, Arnold B. T cell awareness of paternal alloantigens during pregnancy. Science (80-) 1995 doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin S, Bevan MJ. Transient alteration of T cell fine specificity by a strong primary stimulus correlates with T cell receptor down-regulation. Eur J Immunol. 1998 doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<2991::AID-IMMU2991>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamou P, et al. Chronic Exposure to Low Levels of Antigen in the Periphery Causes Reversible Functional Impairment Correlating with Changes in CD5 Levels in Monoclonal CD8 T Cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1278–1284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh NJ, Schwartz RH. The Strength of Persistent Antigenic Stimulation Modulates Adaptive Tolerance in Peripheral CD4+ T Cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawiger D, Masilamani RF, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK, Nussenzweig MC. Immunological unresponsiveness characterized by increased expression of CD5 on peripheral T cells induced by dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan KR, McCue D, Anderton SM. Fas-mediated death and sensory adaptation limit the pathogenic potential of autoreactive T cells after strong antigenic stimulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lees JR, et al. Deletion is neither sufficient nor necessary for the induction of peripheral tolerance in mature CD8+T cells. Immunology. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han S, Asoyan A, Rabenstein H, Nakano N, Obst R. Role of antigen persistence and dose for CD4+ T-cell exhaustion and recovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008437107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359:1361–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James SE, et al. Mathematical Modeling of Chimeric TCR Triggering Predicts the Magnitude of Target Lysis and Its Impairment by TCR Downmodulation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4284–4294. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caruso HG, et al. Tuning sensitivity of CAR to EGFR density limits recognition of normal tissue while maintaining potent antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3505–3518. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arcangeli S, et al. Balance of Anti-CD123 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Binding Affinity and Density for the Targeting of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1933–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han C, et al. Desensitized Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Selectively Recognize Target Cells with Enhanced Antigen Expression. Nat Commun. 2018;9:468. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02912-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eyquem J, et al. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rapoport AP, et al. NY-ESO-1–specific TCR–engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nature Medicine. 2015;21:914–921. doi: 10.1038/nm.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, et al. Directed Evolution of Human T-Cell Receptors with Picomolar Affinities by Phage Display. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:349–354. doi: 10.1038/nbt1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lever M, et al. Architecture of a Minimal Signaling Pathway Explains the T-Cell Response to a 1 Million-Fold Variation in Antigen Affinity and Dose. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:E6630–E6638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608820113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aleksic M, et al. Dependence of T Cell Antigen Recognition on T Cell Receptor-Peptide MHC Confinement Time. Immunity. 2010;32:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dushek O, et al. Antigen potency and maximal efficacy reveal a mechanism of efficient T cell activation. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra39. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iezzi G, Karjalainen K, Lanzavecchia A. The duration of antigenic stimulation determines the fate of naive and effector T cells. Immunity. 1998;8:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris DT, et al. Comparison of T Cell Activities Mediated by Human TCRs and CARs That Use the Same Recognition Domains. J Immunol. 2017:ji1700236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han Q, et al. From the Cover: Polyfunctional responses by human T cells result from sequential release of cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:1607–1612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salerno F, Paolini NA, Stark R, von Lindern M, Wolkers MC. Distinct PKC-mediated posttranscriptional events set cytokine production kinetics in CD8 <sup>+</sup>T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:201704227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704227114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Essen M, et al. The CD3 gamma leucine-based receptor-sorting motif is required for efficient ligand-mediated TCR down-regulation. J Immunol. 2002 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Utzny C, Coombs D, Müller S, Valitutti S. Analysis of peptide/MHC-induced TCR downregulation: Deciphering the triggering kinetics. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2006 doi: 10.1385/CBB:46:2:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas S, et al. Human T cells expressing affinity-matured TCR display accelerated responses but fail to recognize low density of MHC-peptide antigen. Blood. 2011;118:319–329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sousa J, Carneiro J. A mathematical analysis of TCR serial triggering and down-regulation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3219–3227. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200011)30:11<3219::AID-IMMU3219>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altan-Bonnet G, Germain RN. Modeling T Cell Antigen Discrimination Based on Feedback Control of Digital Erk Responses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Das J, et al. Digital Signaling and Hysteresis Characterize Ras Activation in Lymphoid Cells. Cell. 2009;136:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Navarro MN, Feijoo-Carnero C, Arandilla AG, Trost M, Cantrell DA. Protein Kinase D2 Is a Digital Amplifier of T Cell Receptor–Stimulated Diacylglycerol Signaling in Naive CD8+ T Cells. 2014;7:ra99. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toni T, Welch D, Strelkowa N, Ipsen a, Stumpf MPH. Approximate Bayesian computation scheme for parameter inference and model selection in dynamical systems. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:187–202. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murtaza A, Kuchroo VK, Freeman GJ. Changes in the Strength of Co-Stimulation through the B7/CD28 Pathway Alter Functional T Cell Responses to Altered Peptide Ligands. Int Immunol. 1999;11:407–416. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michel F, Attal-Bonnefoy G, Mangino G, Mise-Omata S, Acuto O. CD28 as a Molecular Amplifier Extending TCR Ligation and Signaling Capabilities. Immunity. 2001;15:935–945. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siller-Farfán JA, Dushek O. Molecular mechanisms of T cell sensitivity to antigen. Immunol Rev. 2018;285:194–205. doi: 10.1111/imr.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maus MV, et al. An MHC-Restricted Antibody-Based Chimeric Antigen Receptor Requires TCR-like Affinity to Maintain Antigen Specificity. Mol Ther — Oncolytics. 2016;3:16023. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stewart-Jones G, et al. Rational Development of High-Affinity T-Cell Receptor-Like Antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:5784–5788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901425106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macián F, et al. Transcriptional mechanisms underlying lymphocyte tolerance. Cell. 2002;109:719–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wells AD. New Insights into the Molecular Basis of T Cell Anergy: Anergy Factors, Avoidance Sensors, and Epigenetic Imprinting. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:7331–7341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marangoni F, et al. The Transcription Factor NFAT Exhibits Signal Memory during Serial T Cell Interactions with Antigen-Presenting Cells. Immunity. 2013;38:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Acuto O, Michel F. CD28-mediated co-stimulation: a quantitative support for TCR signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nri1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular Mechanisms of T Cell Co-Stimulation and Co-Inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:227–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pradeu T, Vivier E. The discontinuity theory of immunity. Science Immunology. 2016;1:aag0479. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aag0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith K, et al. Sensory adaptation in naive peripheral CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 2001 doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chiodetti L, Choi S, Barber DL, Schwartz RH. Adaptive Tolerance and Clonal Anergy Are Distinct Biochemical States. J Immunol. 2006;176:2279–2291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Teague RM, et al. Peripheral CD8+ T Cell Tolerance to Self-Proteins Is Regulated Proximally at the T Cell Receptor. Immunity. 2008;28:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Honda T, et al. Tuning of Antigen Sensitivity by T Cell Receptor-Dependent Negative Feedback Controls T Cell Effector Function in Inflamed Tissues. Immunity. 2014;40:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kamphorst AO, et al. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1–targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science (80-) 2017;355:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Savoldo B, et al. Cd28 Costimulation Improves Expansion and Persistence of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells in Lymphoma Patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1822–1826. doi: 10.1172/JCI46110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brentjens RJ, et al. Genetically Targeted T Cells Eradicate Systemic Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5426–5435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carpenito C, et al. Control of Large, Established Tumor Xenografts with Genetically Retargeted Human T Cells Containing Cd28 and Cd137 Domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:3360–3365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813101106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao Z, et al. Structural Design of Engineered Costimulation Determines Tumor Rejection Kinetics and Persistence of CAR T Cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pulè MA, et al. A Chimeric T Cell Antigen Receptor That Augments Cytokine Release and Supports Clonal Expansion of Primary Human T Cells. Mol Ther. 2005;12:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wyzgol A, et al. Trimer stabilization, oligomerization, and antibody-mediated cell surface immobilization improve the activity of soluble trimers of CD27L, CD40L, 41BBL, and glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor ligand. J Immunol. 2009;183:1851–1861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen JLL, et al. Identification of NY-ESO-1 peptide analogues capable of improved stimulation of tumor-reactive CTL. J Immunol. 2000;165:948–955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jakka G, et al. Antigen-Specific in Vitro Expansion of Functional Redirected Ny-Eso-1-Specific Human Cd8+ T-Cells in a Cell-Free System. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4189–4201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tan MP, et al. T cell receptor binding affinity governs the functional profile of cancer-specific CD8+ T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;180:255–270. doi: 10.1111/cei.12570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.