Abstract

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) p7 protein plays a critical role during particle formation in cell culture and is required for virus replication in chimpanzees. The discovery that it displayed cation channel activity in vitro led to its classification within the “viroporin” family of virus-coded ion channel proteins, which includes the influenza A virus (IAV) M2 protein. Like M2, p7 was proposed as a potential target for much needed new HCV therapies, and this was supported by our finding that the M2 inhibitor, amantadine, blocked its activity in vitro. Since then, further compounds have been shown to inhibit p7 function but the relationship between inhibitory effects in vitro and efficacy against infectious virus is controversial. Here, we have sought to validate multiple p7 inhibitor compounds using a parallel approach combining the HCV infectious culture system and a rapid throughput in vitro assay for p7 function. We identify a genotype-dependent and subtype-dependent sensitivity of HCV to p7 inhibitors, in which results in cell culture largely mirror the sensitivity of recombinant protein in vitro; thus building separate sensitivity profiles for different p7 sequences. Inhibition of virus entry also occurred, suggesting that p7 may be a virion component. Second site effects on both cellular and viral processes were identified for several compounds in addition to their efficacy against p7 in vitro. Nevertheless, for some compounds antiviral effects were specific to a block of ion channel function. Conclusion: These data validate p7 inhibitors as prototype therapies for chronic HCV disease. (HEPATOLOGY 2008;48:1779-1790.)

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronically infects over 3% of the population causing severe liver disease. Despite intensive efforts, no vaccine exists and asymptomatic acute infection results in most carriers being unaware of their positive status. Combination antiviral therapy is available based on interferon α (IFNα) and ribavirin (Rib). This treatment is expensive, poorly tolerated, and its outcome is largely determined by virus genotype1; resistance of many genotype 1 isolates results in a sustained response for only 50% of patients overall, despite good response rates for other virus strains. New, virus-specific, therapies are in production, yet face resistance caused by HCV sequence variation.2 Future therapies will likely require combinatorial approaches, targeting multiple virus-specific processes.

HCV is the prototype member of the Hepacivirus genus within the Flaviviridae. It is enveloped and possesses a positive strand RNA genome of ~9.6 kb. An internal ribosome entry site (IRES) present in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) drives translation of a single polyprotein that is cleaved to yield 10 mature proteins. The core and envelope (E) glycoproteins, with the RNA genome, comprise the virion, while nonstructural (NS) proteins modulate host metabolism and replication of the viral RNA.3 Viral insensitivity to IFN/Rib maps to regions within the NS proteins that confer resistance to the innate immune response,4,5 whereas the virus develops resistance to specific drugs via the high error rate of its polymerase, NS5B. Thus, identification of new drug targets has become a major research focus and the new infectious culture system for HCV based on the genotype 2a Japanese fulminant hepatitis-1 (JFH-1) strain represents a major advance in this regard, allowing the processes of virus assembly and entry to be examined for the first time.6–8

The HCV p7 protein oligomerizes to form a heptameric cation channel in vitro9–12 and is yet to be classified as either a structural or NS protein. It is 63 amino acids in length and highly hydrophobic; comprising two amphipathic trans-membrane alpha helices,13–15 separated by a conserved charged loop that is required for ion channel activity in cells16 as well as virus replication in chimpanzees.17 p7 Belongs to the “viroporins,” typified by the influenza A virus (IAV) M2 protein, and is required for efficient assembly and secretion of HCV particles in culture.18,19 Furthermore, p7 localizes to endoplasmic reticulum– derived membranes13,20,21 and can functionally replace M2 in cell-based assays.16

p7 ion channel activity is blocked by the M2 inhibitor, amantadine.9,12,16 Amantadine has been the subject of HCV clinical trials,22 with controversial results. Other inhibitors have subsequently been identified; namely imino-sugars (e.g., N-nonyl deoxynojirimycin [NN-DNJ]),11 hexamethylene amiloride (HMA),10 rimantadine, and experimental compounds (provided by Glaxo-Smith-Kline and termed GSK1-3).23 It is of note that these compounds have hitherto only been tested against genotype 1 p7.

Variations in M2 sequence alters amantadine sensitivity24 and comparison of p7 sequences reveals a high degree of variability, implying that p7 may differ in compound sensitivity in a sequence-specific fashion. A recent study, however, found amantadine to be ineffective at blocking HCV assembly in culture, whereas imino-sugars were effective.25 Here, we have compared these and other inhibitors to assess their relative efficacy against both HCV assembly and p7 channel activity in vitro. Both systems highlight a genotype-dependent pattern of resistance to inhibitors, yet some compounds displayed activity against multiple genotypes. This underpins the need for expansion of the p7 inhibitor repertoire using high-throughput screening or rational drug design.

Materials and Methods

Virus Clones and p7 Expression Plasmids

Full-length JFH-1, JFH-1 chimeric derivatives, the sub-genomic JFH-1 firefly luciferase replicon, and the J4 infectious clone have been described.7,26–28

The bacterial expression construct for J4 p7 has been described.9 Analogous clones for other genotypes were generated identically using appropriate polymerase chain reaction templates. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Cell Culture and RNA Transfection

Huh7 cells were passaged under standard conditions in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. Cells were trypsinized, washed twice, then resuspended at a density of 2 × 107/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (1 × 107 for replicons). Then, 400 μL (8 × 106;4 × 106 for replicons) cells were mixed with 20 μg of in vitro transcribed RNA (or 2 μg replicon RNA and 1 μg capped Renilla transcript), generated using a T7 Megascript kit (Ambion), then placed in a 4-mm electroporation cuvette. Cells were pulsed in a Bio-Rad gene pulser II at 270 V, 950 μF, and then resuspended in an appropriate volume of media.

p7 Inhibitor Compounds

All inhibitors were made as 40-mM stock solutions in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), then diluted as appropriate in media or buffer. Rimantadine and GSK1-3 were provided by GSK.23 Amantadine-HCl and HMA were purchased from Sigma and NN-DNJ from Toronto Biochemicals.

Replicon p7 Inhibitor Assays

Four replicon electroporations (4.8 mL medium each) were pooled and 50 μL cells were added to each well of four 96-well plates; three white-walled luminescence plates (Greiner) and one standard plate. A total of 50 μL of media containing either DMSO or inhibitors was added (four wells/condition). At 24, 48, and 72 hours posttransfection, cells were washed twice in PBS then lysed in 20 μL passive lysis buffer (Promega) or stained for NS5A as described.29 Luciferase activity was quantified in a BMG Fluo Star plate luminometer.

Virus Assembly Inhibition Assays

Electroporated cells were resuspended in 4.8 mL medium and 200 μL was added to each well of a 24-well plate. A total of 100 μL media containing DMSO or inhibitors (each condition in duplicate) was added and cells were cultured for 72 hours; drugs were therefore present throughout the experiment. Virus titers were determined at 72 hours by focus-forming assay (see below). Transfected cells were fixed and stained for NS5A to ensure equal numbers of HCV-positive cells in each well.

Focus-Forming Assay

Naive Huh7 cells were plated at 8 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate. The next day, clarified supernatant was applied undiluted to wells and three further 10-fold dilutions were made. For virus release assays, therefore, residual inhibitor was present in neat inoculum wells but was then diluted, whereas in virus entry assays inhibitor concentrations were constant. Cells were stained for NS5A at 48 hours postinfection.

Virus Entry Inhibition Assays

A total of 50 μL of infectious supernatant derived from single JFH-1 (4 × 104 focus-forming units [FFU]/mL) or J6 chimera (JC-1) (4 × 105 FFU/mL) transfections was added to 50 μL of media containing inhibitors at 2× concentration. Cells were plated as described for focus-forming assays. Cells and virus were preincubated with inhibitors for 1 hour at 37°C prior to overnight infection (16 hours). Cells were washed thoroughly and media was replaced, then cells were grown for a further 32 hours prior to NS5A staining. Murine leukemia virus core particles were produced as described30 using either the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein or JFH-1 E1/E2 as pseudotype envelopes with no envelope controls. Infection of Huh7 cells was performed as above except that infection was quantified by green fluorescent protein fluorescence using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest Pro software.

Antibodies and Western Blotting

Antibody 1055 has been described.21 Antibodies 2715 and 2717 are rabbit anti-peptide sera to the 11 N-terminal and six C-terminal amino acids of the JFH-1 p7 sequence, respectively. Antibody 308 rabbit anti-core, AP33 mouse anti-E2, and sheep anti-NS5A have been described.31–33 Rabbit anti-ICAM-1 antibody was provided by Dr. Toby Tuthill (University of Leeds).

Electroporations for protein analysis were resuspended in 6 mL media and divided into 6-well or 12-well plates. Inhibitors/DMSO were present throughout the experiment. At 72 hours posttransfection, cells were lysed in 50 or 25 μL of EBC lysis buffer,21 respectively. An equal volume of 2× Laemmli buffer was added and 5 μL was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Western blotting was performed as described.21 Recombinant p7 was analyzed as described.9,23

Liposome Dye Release Assay

Recombinant p7 proteins were purified and liposome dye release assays were performed as described.9,23 Solvent concentrations in drug titrations were constant throughout.

Results

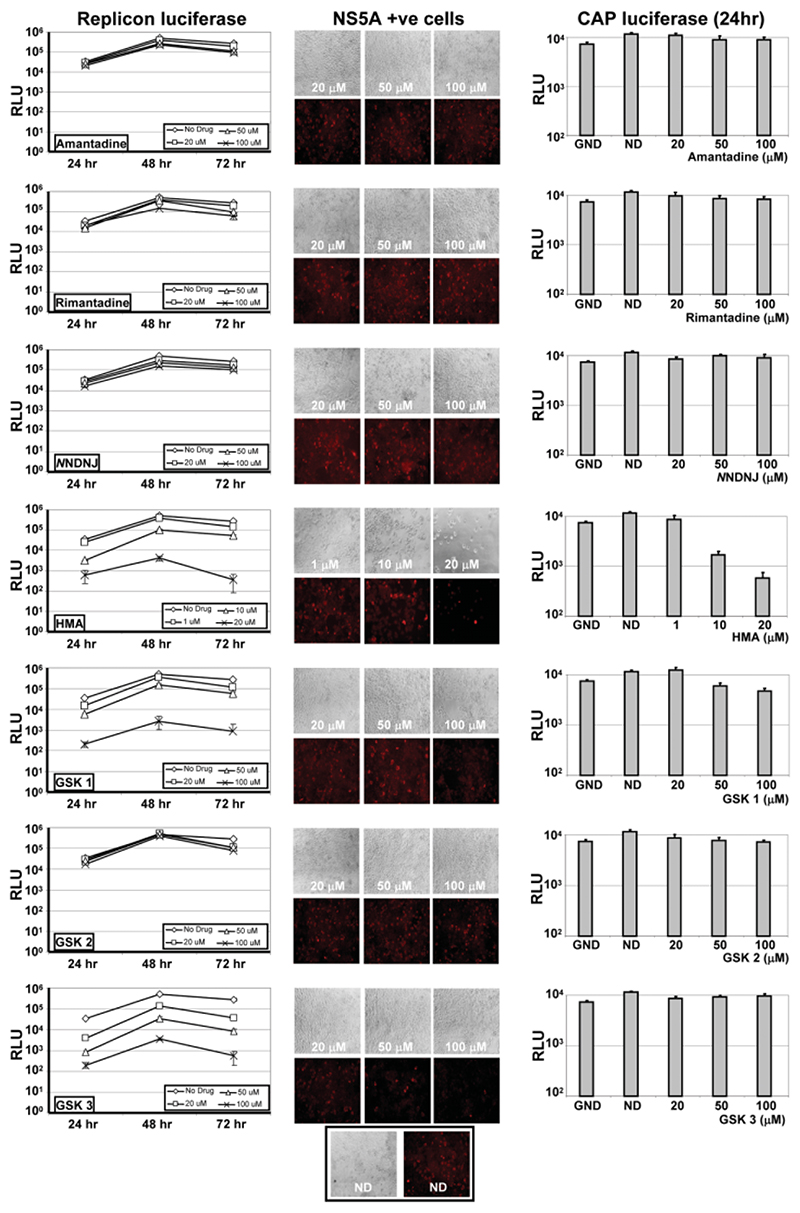

p7 Inhibitors Can Have Nonspecific Effects on HCV Replication and Cell Viability

To ensure that inhibitors acted solely on particle assembly, we tested compounds on Huh7 cells cotransfected with a sub-genomic firefly luciferase JFH-1 replicon and a capped Renilla luciferase transcript to measure cell viability through translational activity. Replicon luciferase activity was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 hours (Fig. 1, left-hand panels) whereas activity from capped transcripts was only measured at 24 hours (Fig. 1, right-hand panels), as levels dropped sharply at later time points. Cells were stained at 72 hours for NS5A in parallel (Fig. 1, middle panels).

Fig. 1.

Effects of p7 inhibitors on HCV replication and cell viability. Huh7 cells were coelectroporated with a subgenomic firefly luciferase JFH-1 HCV replicon and a capped transcript encoding Renilla luciferase. Transfections were split into wells of a 96-well plate and inhibitors were added immediately following transfection. Dual luciferase assays were used to assess effects at 24, 48, and 72 hours, although Renilla values were only measurable at 24 hours (right-hand panels). NS5A immunofluorescence was assessed in parallel at 72 hours (middle panels). Each condition was assessed in quadruplicate and results show the means of three independent experiments. Error bars show standard deviations. Replicon firefly luciferase activity (left-hand panels) and Renilla luciferase activity (right-hand panels) are shown relative to no drug (ND) and polymerase knockout (GND) controls. Drugs added at 20, 50, and 100 μM, except HMA, which was added at 1, 10, and 20 μM.

HMA at concentrations of 20 μM or greater was extremely cytotoxic, with few cells surviving at 72 hours (data not shown). At lower concentrations (up to 20 μM), HMA still displayed a pronounced effect on both replication and cellular translation. GSK1 also showed a mild effect on cellular translation at high concentrations (100 μM). Both GSK1 and GSK3 strongly inhibited RNA replication in a dose-dependent fashion.

Amantadine, GSK2, rimantadine, and NN-DNJ had no significant effect on Huh7 cell viability. At high concentrations (100 μM), however, each of these compounds was seen to reduce HCV RNA replication at the 48-hour and 72-hour time points. This was most notable at 48 hours, when replicon replication was at peak levels; both NNDNJ and rimantadine reduced luciferase activity by up to 75%. However, this reduction was not as pronounced as that seen with GSK3, for example, which reduced luciferase activity by almost 1,000-fold, and did not correlate with a reduction in the number of NS5A-positive cells at 72 hours (Fig. 1, middle panel).

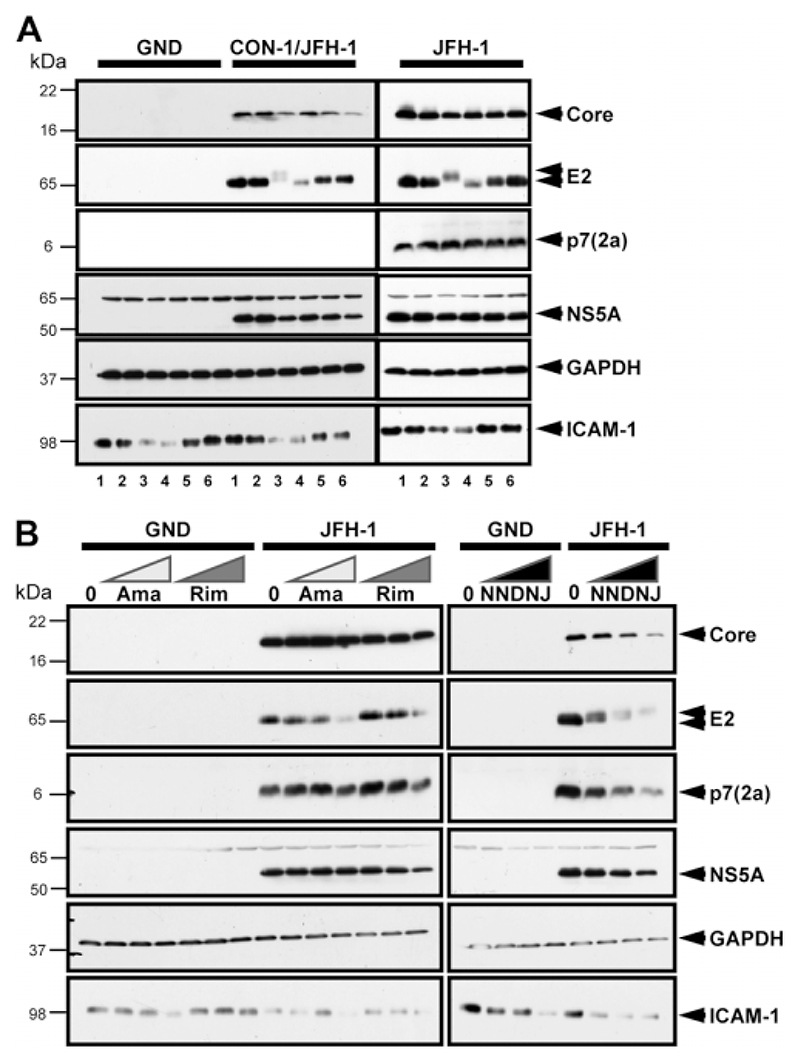

Effects of p7 Inhibitors on Viral and Cellular Glycoproteins

Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ)-based imino-sugars inhibit α-glucosidases, reducing N-linked glycan trimming and resulting in retardation of glycoprotein electrophoretic mobility.34 Thus it was necessary to ensure that inhibitory effects were not due to aberrant glycosylation of viral glycoproteins. We performed western blot analysis on cells transfected with JFH-1 and CON-1/JFH-1 RNA and treated them with inhibitors at maximal doses. In addition to viral proteins, lysates were analyzed for N-glycosylated ICAM-1 and nonglycosylated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Effects of p7 inhibitors on viral and cellular protein expression. (A) Huh7 cells were electroporated with GND, CON-1/JFH-1, or JFH-1 RNA and cells split into the wells of a six-well plate. Inhibitors were added at maximal concentrations and cells cultured for 72 hours. Cells were then lysed and analyzed. 1, no inhibitor; 2, 1 μM HMA; 3, 100 μM NN-DNJ; 4, 100 μM amantadine; 5, 100 μM rimantadine; 6, 100 μM GSK2. (B) Huh7 cells were transfected with either GND or JFH-1 RNA as in (A), but split into a 12-well dish with increasing concentrations of inhibitors added (20, 50, and 100 μM of amantadine, rimantadine, and NN-DNJ). Cell lysates were analyzed for viral (core, E2, p7 genotype 2a, and NS5A) and cellular proteins (GAPDH and ICAM-1) by western blot.

Treatment with NN-DNJ resulted in retarded mobility of E2 (Fig. 2A). In addition, total levels of both E2 and ICAM-1 were markedly reduced (Fig. 2A), although size differences of ICAM-1 were not resolvable. This effect appeared more pronounced for E2 than for ICAM-1. Surprisingly, a reduction in glycoprotein levels was also observed in amantadine-treated cells, although E2 mobility was increased rather than retarded. Decreased ICAM-1 was also observed for both compounds in GND-transfected cells. Neither GAPDH nor other viral proteins were affected by NN-DNJ/amantadine treatment, indicating a glycoprotein-specific effect. Rimantadine, GSK2, and HMA had no effect on protein glycosylation.

Titration experiments showed that both amantadine and NN-DNJ affected glycoproteins in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2B). Effects on glycoproteins were apparent at an amantadine concentration of 100 μM, whereas NN-DNJ showed a significant effect at 20 μM.

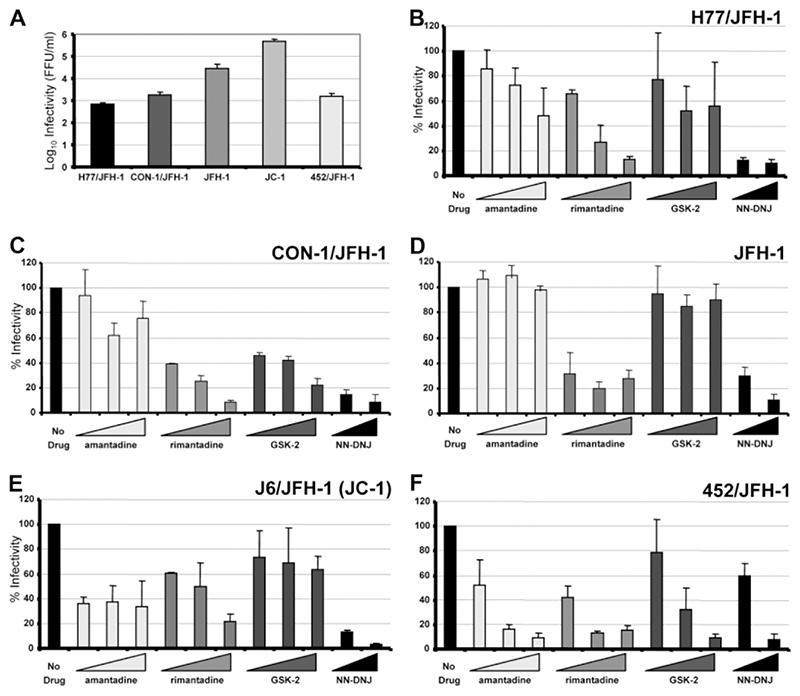

p7 Inhibitors Differentially Inhibit HCV Release According to Genotype

Despite the fact that nearly all of the compounds tested showed nonspecific effects, there was a clear difference between those compounds causing cytotoxic (HMA) or strongly inhibitory (GSK1 and GSK3) effects compared with those causing small reductions in replicon luciferase activity at high concentrations. Despite global effects on glycoprotein processing, amantadine and NNDNJ are the subject of previous studies, making them important to include here. It was therefore decided to compare the relative efficacy of amantadine, rimantadine, GSK2, and NN-DNJ against chimeric JFH-1 derivatives26 containing the structural proteins from genotypes 1a (H77), 1b (CON-1), 2a (J6, known as “JC-1”), and 3a (452) as well as parental 2a JFH-1.7 As p7 has been shown to act during virus assembly,18,19 we employed a one-step infectious assay with inhibitors present throughout. These results would then be compared to an in vitro assay for p7 ion channel function (see below).

Transfected cells were incubated in the presence of inhibitors or DMSO for 72 hours and virus release was quantified by focus-forming assay. As chimeras produced infectious virus to varying degrees (Fig. 3A), titers were expressed as % untreated value (Fig. 3B-F). In accordance with other studies,25 amantadine caused no reduction in the production of infectious HCV by parental JFH-1 or the CON-1 chimera in Huh7 cells (Fig. 3C,D). Interestingly, we did observe a reduction in titer for JC1 (Fig. 3E), although this did not increase with higher drug concentrations. The genotype 3a 452 chimera, however, showed a dose-dependent reduction in titer, indicative of a specific inhibition of virus production (Fig. 3F), as did the H77 chimera, albeit to a far lesser extent (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of HCV release by p7 inhibitors in a one-step infectious assay. Huh7 cells were electroporated with JFH-1 or chimeric RNA then split into 24-well plates. Inhibitors were added at each concentration in duplicate (20, 50, and 100 μM for amantadine, rimantadine, and GSK2; 50 and 100 μM for NN-DNJ). At 72 hours posttransfection, clarified supernatants were titrated by focus-forming assay. Results show the average of at least three experimental repeats for each virus and error bars represent the standard error of the mean between experiments. (A) Summary of average virus titers in focus-forming units (FFU)/mL for JFH-1 and chimeric derivatives. (B-F) Titers obtained following drug treatment relative to untreated controls (100%) for H77/JFH-1, CON-1/JFH-1, JFH-1, JC-1, and 452/JFH-1.

Unlike amantadine, rimantadine caused a dose-dependent inhibition of virus production for all viruses tested. NN-DNJ, too, effectively reduced virus titer in a dose-dependent fashion, although was less effective against the 452 chimera at 50 μM (Fig. 3F). GSK2 varied in its ability to block virus production and was effective only against the CON-1 and 452 chimeras. Together, the effects of inhibitors indicated a genotype-dependent or subtype-dependent pattern of sensitivity, implying that the p7 sequence might determine their effects on virus release.

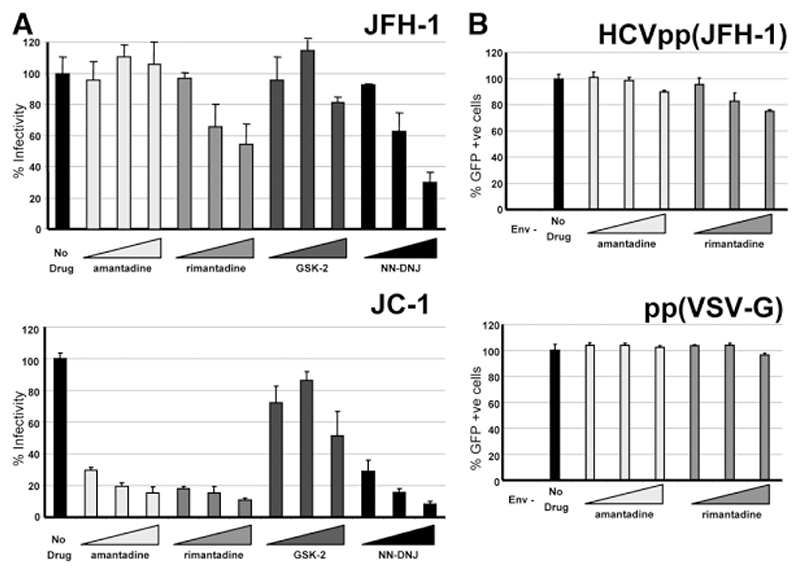

p7 Inhibitors Partially Inhibit Virus Entry

The possibility that p7 may be incorporated into HCV virions gives rise to a potential role in virus entry, which could be blocked by inhibitors. Infectious supernatants from single JFH-1 or JC-1 transfections were therefore diluted in the presence of inhibitors and used to infect naive cells (Fig. 4). Interestingly, infection with JFH-1 was reduced upon treatment with rimantadine and NN-DNJ, but not by amantadine or GSK2, whereas JC-1 infection was reduced by all compounds apart from GSK2. This represents the same pattern of inhibition as seen in the virus release assays (above). For JFH-1, however, this inhibition was reduced compared to where drugs were present throughout, whereas inhibition was seen to similar levels for the JC-1 virus. The differential sensitivity of these two viruses to amantadine argues against a nonspecific alteration of cellular endocytosis mechanisms being responsible for the observed reduction of infection. Accordingly, entry of lentiviral cores pseudotyped with the JFH-1 envelope was only minimally affected by adamantanes at the highest concentrations (Fig. 4B). A small effect was also seen for a vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G envelope and, unlike JFH-1 virus, occurred with both amantadine and rimantadine. An effect on HCV entry has also been observed previously for NN-DNJ.25

Fig. 4.

Effects of p7 inhibitors on virus entry. (A) Infectious supernatants were diluted in the presence of p7 inhibitors then applied to Huh7 cells (20, 50, and 100 μM). At 12 hours, cells were thoroughly washed to remove inhibitors and then cultured for 36 hours. Titers were determined by focus-forming assay. Results show the average of two experimental repeats with each condition in triplicate. Error bars show the standard error of the mean between experiments. (B) Entry experiments above were repeated for lentiviral cores pseudotyped with JFH-1 or vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G envelopes. Infection was quantified by GFP fluorescence. All conditions were repeated in quadruplicate.

Genotype-Dependent Sensitivity of p7 In Vitro CorRelates with Cell Culture Data

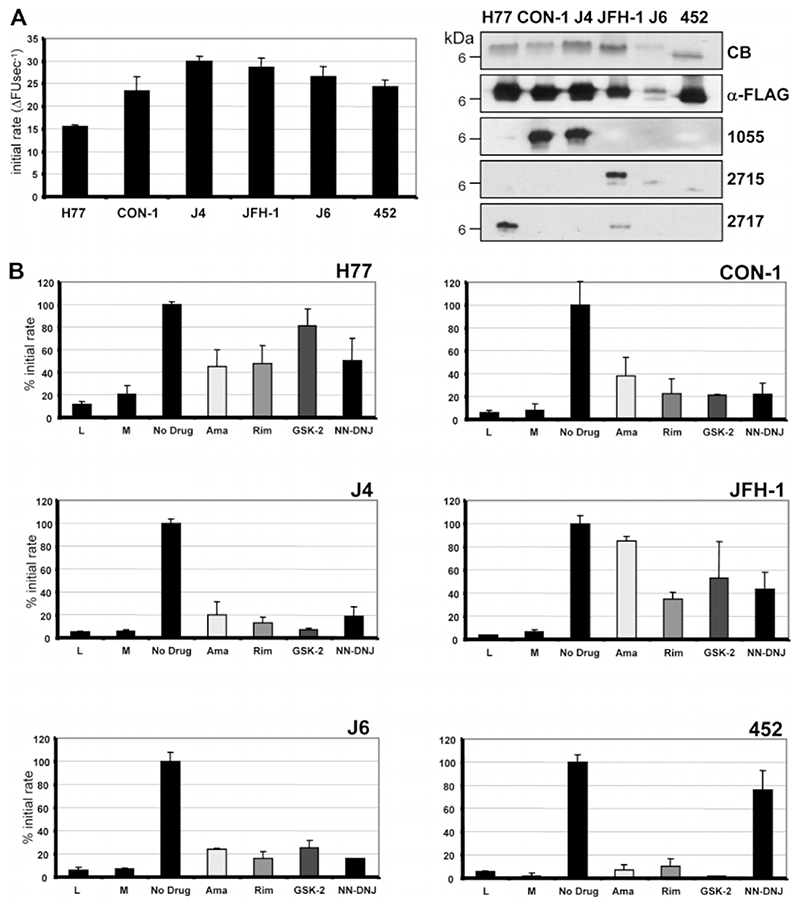

We recently described an in vitro assay for J4 p7 function based on the ability of p7 to mediate release of a fluorescent dye, CF, from liposomes.23 We used this system to investigate whether p7 from different HCV isolates showed the same differential sensitivity to inhibitors observed for corresponding chimeric viruses. Recombinant p7 proteins were purified and their relative activities assessed (Fig. 5A). With the exception of the H77 p7, which displayed reproducibly lower channel activity, p7 from other genotypes displayed similar activities to J4 (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Effects of inhibitors on p7-mediated fluorescent dye release from liposomes. (A) Recombinant p7 for each genotype was expressed and purified from E. coli and its activity measured by fluorescent dye release from liposomes.23 The graph shows the initial rate of CF release as the change in fluorescent units per second (ΔFU second-1) averaged over the first five minutes of at least three separate repeats with different batches of protein. Purity and integrity of proteins was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blotting using anti-FLAG or anti-p7 antibodies. CB, Coomassie Blue stain; 1055, anti J4 p7 C-terminus; 2715, anti JFH-1 p7 N-terminus; 2717, anti JFH-1 p7 C-terminus. (B) Effects on initial rates relative to untreated (DMSO only; 100%) of adding inhibitors to assay at 1 μM concentration for each protein. L, liposomes only; M, methanol solvent control. Results are averages of at least three separate experiments with each condition performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Addition of compounds at 1 μM concentration resulted in inhibition of CF release that predominantly followed the patterns observed in cell culture (Fig. 5B; Table 1). One exception was the inhibitory effect of amantadine on CON-1 p7 in vitro, as the drug displayed no efficacy in culture. This was also true for inhibition of J6 p7 by GSK2, where again this compound did not affect virus production in culture.

Table 1. Summary of Inhibitor Effects for Virus/p7 Protein Sequences in Culture and In Vitro.

| Virus* | Liposome† | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ama | Rim | GSK2 | DNJ | Ama | Rim | GSK2 | DNJ | ||

| H77 | + | + + | − | ++ + | + | + | − | + | |

| CON-1 | − | +++ | +++ | ++ + | + + | +++ | + + + | +++ | |

| J4 | Not determined | + + + | +++ | + + + | +++ | ||||

| JFH-1 | − | + + + | − | ++ + | − | ++ | − | + | |

| JC1 | +++ | + + | − | ++ + | + + | +++ | + + | +++ | |

| 452 | +++ | + + + | + + | + | + + + | +++ | + + + | − | |

Virus: +++, >50% inhibition at 20 μM; ++, >50% inhibition at 50 μM; +, >50% inhibition at 100 μM; −; no significant inhibition.

Liposome: +++, <20% untreated rate; ++, <40% untreated rate; +, <60% untreated rate; −, no significant inhibition.

In agreement with cell culture experiments, amantadine did not block the activity of JFH-1 p7 in vitro. Insensitivity of 452 p7 to NN-DNJ in vitro also correlated with resistance to this drug at 50 μM in cell culture. H77 p7 was, overall, less sensitive to inhibitors that were effective against the virus in culture, though it remained insensitive to GSK2.

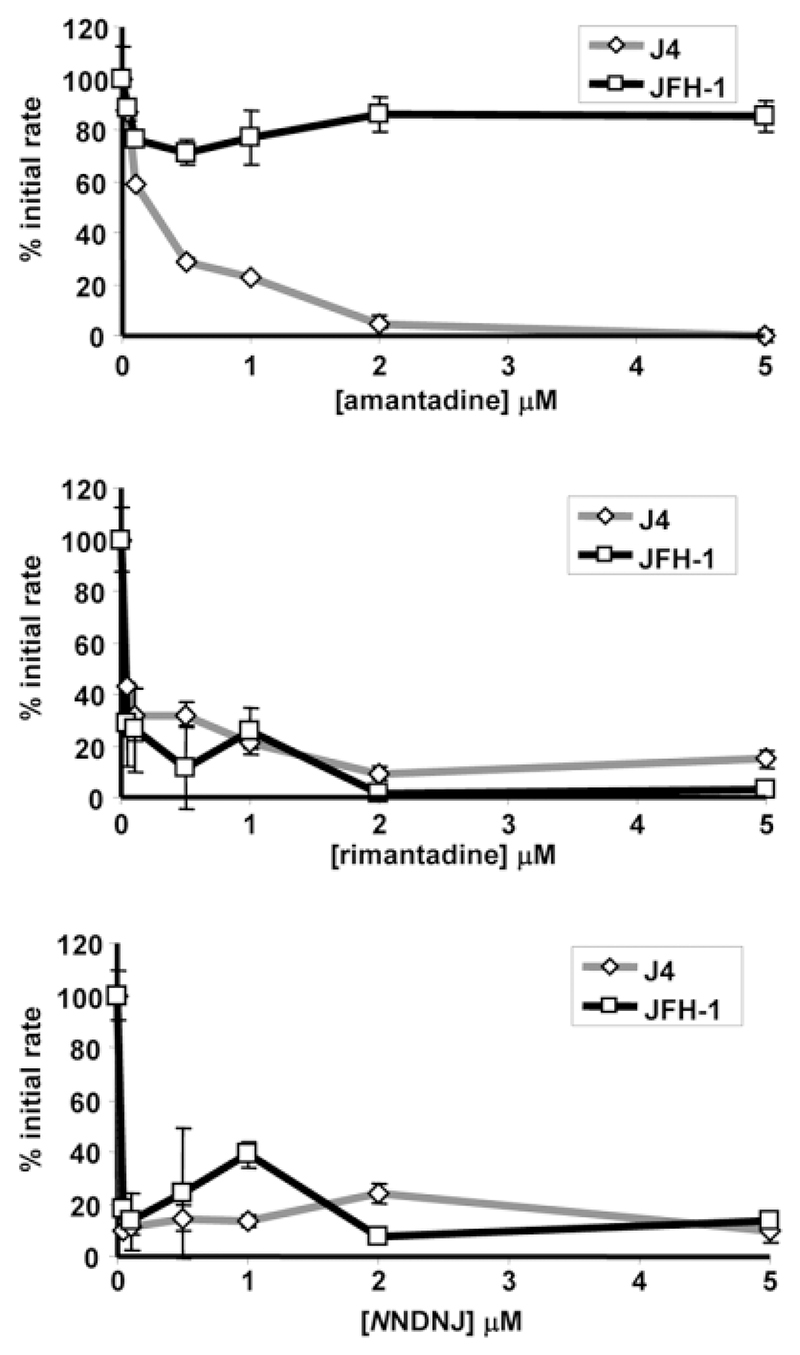

To determine whether resistance of p7 to inhibitors was concentration-dependent, J4 and JFH-1 p7 proteins were subjected to increasing concentrations of amantadine, rimantadine, and NN-DNJ (Fig. 6). J4 p7 was inhibited by low (<0.5 μM) concentrations of all three inhibitors, whereas the JFH-1 protein remained active despite the presence of up to 10 times this concentration of amantadine (5 μM). These results confirm that p7 sequences display altered sensitivity to inhibitors, implying a specific interaction between compounds and residues lining the p7 channel lumen.

Fig. 6.

Effects of increasing inhibitor concentrations on susceptible and resistant p7 proteins. Effects of increasing concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μM) of amantadine, rimantadine, and NN-DNJ on activity of J4 and JFH-1 recombinant p7 activity in liposome dye release were measured as % of untreated initial rate. Results are an average of three experiments with each condition in triplicate. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Discussion

This study evaluated inhibitors of the p7 ion channel using both the HCV culture system and an in vitro assay for p7 function. Release of infectious HCV in culture was reproducibly blocked by compounds known to inhibit p7 function in vitro; further validating p7 inhibitors as potential therapeutic options. Furthermore, both methods showed that inhibitor efficacy is dependent on the genotype or subtype of the p7 sequence with good correlation; producing the same patterns of susceptibility for each virus/protein tested. These observations have profound implications for the development of antivirals targeting p7 as compounds will need to be tested against multiple genotypes.

The application of p7 inhibitors identified in vitro to HCV cell culture raises the important question of compound specificity. The compounds tested herein fell into two broad categories; those that displayed pronounced effects (several orders of magnitude) in the HCV replicon system (HMA, GSK1, and GSK3) and those that caused a comparatively small reduction (within the same order of magnitude) at high concentrations (amantadine, rimantadine, NNDNJ, and GSK2) (Fig. 1); subsequently tested against infectious virus. This was further complicated by a global effect on glycoprotein processing observed for amantadine and NNDNJ (Fig. 2). These two second site effects seemingly call into question whether any of the compounds tested in the infectious system exert their effects via a specific inhibition of p7 ion channel function; instead, blocking virus release by either a reduction in virus replication or by depleting the levels of viral glycoproteins. The genotype-dependent or subtype-dependent variation in compound efficacy we observed, however, strongly argues against either of these possibilities. Each chimera shares identical RNA replication machinery with parental JFH-1 and so would be expected to show equivalent sensitivity to an inhibitor that only targeted genome replication, yet this was clearly not the case. In addition, levels of nonstructural proteins were unaffected by the addition of these compounds (Fig. 2) and the number of NS5A-positive JFH-1/chimera transfected cells at 72 hours did not differ to untreated wells (data not shown). Furthermore, as both amantadine and NNDNJ also varied in efficacy, it appears likely that levels of functional E2 were not limiting for virus assembly despite the aberrant processing observed by western blot (Fig. 2). This is perhaps not surprising, given that even the most effective particle producing chimera, JC-1, only produces approximately one infectious particle per transfected cell. The same genotype-dependent pattern of sensitivity was evident when inhibitors were present during virus entry, or for individual p7 proteins in vitro; supporting the hypothesis that amantadine, rimantadine, GSK2, and NNDNJ primarily act by blocking the ion channel function of p7.

We are unclear as to why we saw an effect for amantadine on virus release for the JC-1 and H77 chimeras whereas previous studies did not,25 though this may be due to the use of different cell types; Huh7 in our experiments and a combination of Huh7-Lunet and Huh7.5 cells previously. We also used higher concentrations in culture, although effects were apparent in the lower range for both JC-1 and the 452 chimera, which was not included in the previous study. All three equivalent p7 proteins were also sensitive to amantadine in the liposome assay at 1 μM, yet previous single channel studies using an H77 p7 synthetic peptide have shown that much higher amantadine concentrations were necessary for inhibition in suspended bilayers.25 This may be explained by H77 p7 showing reduced activity with less sensitivity overall to inhibitors in the liposome assay. By contrast, amantadine did not reduce virus production for the CON-1/JFH-1 chimera, despite effectively blocking the activity of this protein in vitro. NNDNJ was generally effective in blocking virus release except in the case of the 452 chimera, which was less affected at 50 μM and whose p7 was insensitive to the drug in vitro. Rimantadine was the only compound that blocked both virus release and p7 activity in vitro in each case, whereas the GSK2 compound only showed efficacy against the 452 and CON-1 chimeras despite also blocking the J6 p7 in vitro.

A moderate effect was observed when inhibitors used to block JFH-1 virus entry, with a more pronounced effect for entry of JC-1 virions. These two closely related viruses differ in their sensitivity to amantadine, which argues against a nonspecific blocking of endocytosis being responsible for the action of these weakly basic compounds. Entry of JFH-1 lentiviral pseudotypes, however, was minimally inhibited by both amantadine and rimantadine at the highest concentration, suggesting a partial block of endocytosis may have occurred, yet in the absence of p7, the genotype-dependent pattern of sensitivity is lost. This indirectly supports the presence of p7 in HCV virions, although studies in Pestiviruses did not find it to be present in purified particles,35 yet an effect on both BVDV and HCV entry has previously been observed for p7-specific imino-sugars.25,36

The critical observation from these studies is the identification of genotype-dependent patterns of p7 inhibitor sensitivity for HCV. To date, all compounds identified in vitro have been tested against genotype 1 p7 sequences,9–12 which differ from other genotypes (Fig. 7). p7 sequences contain clusters of hydrophilic amino acids predicted to line the channel lumen, implying these might determine channel opening and drug sensitivity, as is the case for M2.37,38 As at least one function of p7 may be analogous to that of M2 during particle secretion,16 it is possible that variation at these sites might determine the sensitivity of HCV to p7 inhibitors. Comparing the differential sensitivities of the closely related JFH-1 and J6 proteins implies that quasispecies or subtype variation might rapidly result in resistance. Indeed, a recent study of amantadine alongside IFN/Rib showed that, following an initial drop, virus load recovered after only a few weeks,39 and this has also been observed for amantadine monotherapy.40 Similar rebound is also seen in trials involving single protease inhibitors.2 The development of future p7 inhibitors, therefore, will likely require testing against multiple p7 sequences and resultant compounds are only likely to be effective when used in combination with other HCV-specific compounds or IFN/Rib. It should also be noted that, in this and other studies,25 effective p7 inhibitors were not able to reduce virus titer by more than 10-fold at the concentrations used. Thus, compounds identified to date merely provide proof of principle for p7 as a drug target.

Fig. 7.

Alignment of p7 sequences according to genotype. Alignment of p7 sequences analyzed in this study. Hydrophilic residues are shown in red, basic in blue, and acidic in green.

Overall, these studies validate the use of p7 inhibitors for future HCV therapies, but a genotype-dependent pattern of sensitivity highlights the need for developing more potent compounds active against multiple p7 sequences.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Prof. Takaji Wakita (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Neuroscience) for the JFH-1 full-length infectious clone; Prof. Ralf Bartenschlager (University of Heidelberg, Germany) and Dr. Thomas Pietschmann (University of Hannover, Germany) for chimeric JFH-1 derivatives; Prof. Jens Bukh (Hvidovre University Hospital, Denmark, and the National Institutes of Health) for the J4 infectious clone; Dr. John McLauchlan and Dr. Paul Targett-Adams (MRC Virology Unit, Glasgow, UK) for the JFH-1 luciferase replicon and anti-core antibody 308; and Dr. Toby Tuthill (University of Leeds, UK) for the anti-ICAM-1 antibody. We also thank Dr. Helen Bright (GlaxoSmith-Kline [GSK], Stevenage, UK) for provision of the p7 inhibitor compounds and Dr. Sarah Gretton and Mair Hughes (University of Leeds, UK) for capped Renilla luciferase RNA.

Abbreviations

- BVDV

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus

- CF

carboxyfluorescein

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EBC

enriched broth culture

- FFU

focus-forming unit

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSK

Glaxo-Smith-Kline

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HMA

hexamethylene amiloride

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IAV

influenza A virus

- ICAM-1

intracellular adhesion molecule-1

- IFNα

interferon α.

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- JFH-1

Japanese fulminant hepatitis-1

- NS

nonstructural

- NN-DNJ

N-nonyl deoxynojirimycin

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- Rib

ribavirin

- UTR

untranslated region

- VSV-G

vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Pawlotsky JM. Therapy of hepatitis C: from empiricism to eradication. HEPATOLOGY. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S207–S220. doi: 10.1002/hep.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarrazin C, Kieffer TL, Bartels D, Hanzelka B, Muh U, Welker M, et al. Dynamic hepatitis C virus genotypic and phenotypic changes in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1767–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moradpour D, Gosert R, Egger D, Penin F, Blum HE, Bienz K. Membrane association of hepatitis C virus nonstructural proteins and identification of the membrane alteration that harbors the viral replication complex. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17717–17722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508531102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald A, Harris M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A: tales of a promiscuous protein. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2485–2502. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, et al. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke D, Griffin S, Beales L, Gelais CS, Burgess S, Harris M, et al. Evidence for the formation of a heptameric ion channel complex by the hepatitis C virus p7 protein in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37057–37068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602434200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Premkumar A, Wilson L, Ewart GD, Gage PW. Cation-selective ion channels formed by p7 of hepatitis C virus are blocked by hexamethylene amiloride. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavlovic D, Neville DC, Argaud O, Blumberg B, Dwek RA, Fischer WB, et al. The hepatitis C virus p7 protein forms an ion channel that is inhibited by long-alkyl-chain iminosugar derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6104–6108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031527100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin SD, Beales LP, Clarke DS, Worsfold O, Evans SD, Jaeger J, et al. The p7 protein of hepatitis C virus forms an ion channel that is blocked by the antiviral drug, Amantadine. FEBS Lett. 2003;535:34–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrere-Kremer S, Montpellier-Pala C, Cocquerel L, Wychowski C, Penin F, Dubuisson J. Subcellular localization and topology of the p7 polypeptide of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2002;76:3720–3730. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3720-3730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima H, Hijikata M, Asabe S, Hirota M, Kimura K, Shimotohno K. Two hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2 products with different C termini. J Virol. 1994;68:6215–6222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6215-6222.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin C, Lindenbach BD, Pragai BM, McCourt DW, Rice CM. Processing in the hepatitis C virus E2-NS2 region: identification of p7 and two distinct E2-specific products with different C termini. J Virol. 1994;68:5063–5073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5063-5073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin SD, Harvey R, Clarke DS, Barclay WS, Harris M, Rowlands DJ. A conserved basic loop in hepatitis C virus p7 protein is required for amantadine-sensitive ion channel activity in mammalian cells but is dispensable for localization to mitochondria. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:451–461. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai A, Claire MS, Faulk K, Govindarajan S, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, et al. The p7 polypeptide of hepatitis C virus is critical for infectivity and contains functionally important genotype-specific sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11646–11651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834545100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones CT, Murray CL, Eastman DK, Tassello J, Rice CM. Hepatitis C virus p7 and NS2 proteins are essential for production of infectious virus. J Virol. 2007;81:8374–8383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00690-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinmann E, Penin F, Kallis S, Patel AH, Bartenschlager R, Pietschmann T. Hepatitis C virus p7 protein is crucial for assembly and release of infectious virions. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haqshenas G, Mackenzie JM, Dong X, Gowans EJ. Hepatitis C virus p7 protein is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum when it is encoded by a replication-competent genome. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:134–142. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin S, Clarke D, McCormick C, Rowlands D, Harris M. Signal peptide cleavage and internal targeting signals direct the hepatitis C virus p7 protein to distinct intracellular membranes. J Virol. 2005;79:15525–15536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15525-15536.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deltenre P, Henrion J, Canva V, Dharancy S, Texier F, Louvet A, et al. Evaluation of amantadine in chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2004;41:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.StGelais C, Tuthill TJ, Clarke DS, Rowlands DJ, Harris M, Griffin S. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus p7 membrane channels in a liposome-based assay system. Antiviral Res. 2007;76:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hay AJ, Wolstenholme AJ, Skehel JJ, Smith MH. The molecular basis of the specific anti-influenza action of amantadine. EMBO J. 1985;4:3021–3024. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinmann E, Whitfield T, Kallis S, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N, Pietschmann T, Bartenschlager R. Antiviral effects of amantadine and iminosugar derivatives against hepatitis C virus. HEPATOLOGY. 2007;46:330–338. doi: 10.1002/hep.21686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietschmann T, Kaul A, Koutsoudakis G, Shavinskaya A, Kallis S, Steinmann E, et al. Construction and characterization of infectious intragenotypic and intergenotypic hepatitis C virus chimeras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7408–7413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504877103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Targett-Adams P, McLauchlan J. Development and characterization of a transient-replication assay for the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:3075–3080. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yanagi M, Claire M, Shapiro M, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Bukh J. Transcripts of a chimeric cDNA clone of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b are infectious in vivo. Virology. 1998;244:161–172. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCormick CJ, Maucourant S, Griffin S, Rowlands DJ, Harris M. Tagging of NS5A expressed from a functional hepatitis C virus replicon. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:635–640. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1–E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLauchlan J, Lemberg MK, Hope G, Martoglio B. Intramembrane proteolysis promotes trafficking of hepatitis C virus core protein to lipid droplets. EMBO J. 2002;21:3980–3988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owsianka A, Clayton RF, Loomis-Price LD, McKeating JA, Patel AH. Functional analysis of hepatitis C virus E2 glycoproteins and virus-like particles reveals structural dissimilarities between different forms of E2. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1877–1883. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-8-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macdonald A, Crowder K, Street A, McCormick C, Saksela K, Harris M. The hepatitis C virus non-structural NS5A protein inhibits activating protein-1 function by perturbing ras-ERK pathway signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17775–17784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branza-Nichita N, Durantel D, Carrouee-Durantel S, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N. Antiviral effect of N-butyldeoxynojirimycin against bovine viral diarrhea virus correlates with misfolding of E2 envelope proteins and impairment of their association into E1–E2 heterodimers. J Virol. 2001;75:3527–3536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3527-3536.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbers K, Tautz N, Becher P, Stoll D, Rumenapf T, Thiel HJ. Processing in the pestivirus E2-NS2 region: identification of proteins p7 and E2p7. J Virol. 1996;70:4131–4135. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4131-4135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durantel D, Branza-Nichita N, Carrouee-Durantel S, Butters TD, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N. Study of the mechanism of antiviral action of iminosugar derivatives against bovine viral diarrhea virus. J Virol. 2001;75:8987–8998. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.8987-8998.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinto LH, Dieckmann GR, Gandhi CS, Papworth CG, Braman J, Shaughnessy MA, et al. A functionally defined model for the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus suggests a mechanism for its ion selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11301–11306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okada A, Miura T, Takeuchi H. Protonation of histidine and histidine-tryptophan interaction in the activation of the M2 ion channel from influenza a virus. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6053–6060. doi: 10.1021/bi0028441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maynard M, Pradat P, Bailly F, Rozier F, Nemoz C, Si Ahmed SN, et al. Amantadine triple therapy for non-responder hepatitis C patients. Clues for controversies (ANRS HC 03 BITRI. J Hepatol. 2006;44:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan J, O’Riordan K, Wiley TE. Amantadine’s viral kinetics in chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:438–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1013703013053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]