Summary

Background

Underweight and obesity are associated with adverse health outcomes throughout the life course. We estimated the individual and combined prevalence of underweight or thinness and obesity, and their changes, from 1990 to 2022 for adults and school-aged children and adolescents in 200 countries and territories.

Methods

We used data from 3663 population-based studies with 222 million participants that measured height and weight in representative samples of the general population. We used a Bayesian hierarchical model to estimate trends in the prevalence of different BMI categories, separately for adults (age ≥20 years) and school-aged children and adolescents (age 5–19 years), from 1990 to 2022 for 200 countries and territories. For adults, we report the individual and combined prevalence of underweight (BMI <18·5 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). For school-aged children and adolescents, we report thinness (BMI <2 SD below the median of the WHO growth reference) and obesity (BMI >2 SD above the median).

Findings

From 1990 to 2022, the combined prevalence of underweight and obesity in adults decreased in 11 countries (6%) for women and 17 (9%) for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 that the observed changes were true decreases. The combined prevalence increased in 162 countries (81%) for women and 140 countries (70%) for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80. In 2022, the combined prevalence of underweight and obesity was highest in island nations in the Caribbean and Polynesia and Micronesia, and countries in the Middle East and north Africa. Obesity prevalence was higher than underweight with posterior probability of at least 0·80 in 177 countries (89%) for women and 145 (73%) for men in 2022, whereas the converse was true in 16 countries (8%) for women, and 39 (20%) for men. From 1990 to 2022, the combined prevalence of thinness and obesity decreased among girls in five countries (3%) and among boys in 15 countries (8%) with a posterior probability of at least 0·80, and increased among girls in 140 countries (70%) and boys in 137 countries (69%) with a posterior probability of at least 0·80. The countries with highest combined prevalence of thinness and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents in 2022 were in Polynesia and Micronesia and the Caribbean for both sexes, and Chile and Qatar for boys. Combined prevalence was also high in some countries in south Asia, such as India and Pakistan, where thinness remained prevalent despite having declined. In 2022, obesity in school-aged children and adolescents was more prevalent than thinness with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 among girls in 133 countries (67%) and boys in 125 countries (63%), whereas the converse was true in 35 countries (18%) and 42 countries (21%), respectively. In almost all countries for both adults and school-aged children and adolescents, the increases in double burden were driven by increases in obesity, and decreases in double burden by declining underweight or thinness.

Interpretation

The combined burden of underweight and obesity has increased in most countries, driven by an increase in obesity, while underweight and thinness remain prevalent in south Asia and parts of Africa. A healthy nutrition transition that enhances access to nutritious foods is needed to address the remaining burden of underweight while curbing and reversing the increase in obesity.

Funding

UK Medical Research Council, UK Research and Innovation (Research England), UK Research and Innovation (Innovate UK), and European Union.

Introduction

Underweight and obesity are associated with adverse health outcomes throughout the life course. Therefore, optimal nutrition and health policies should address both forms of malnutrition, as indicated by Sustainable Development Goal Target 2.2, which calls for ending “all forms of malnutrition”. Trends in underweight and obesity have varied substantially across countries and age groups.1–4 Furthermore, underweight and obesity have changed independently of each other in some regions.2 Despite these heterogeneities, global data on how the combined (double) burden of underweight and obesity has changed in terms of magnitude and composition are scarce, and the latest data on their individual prevalence are from 2016.1 This lack of consistent evidence hinders optimal resource allocation and policy formulation to address both forms of malnutrition.

We estimated individual and combined prevalence of underweight and obesity among adults and school-aged children and adolescents from 1990 to 2022. After 1990, the focus on obesity as an epidemic increasingly matched that on undernutrition and the phrase nutrition transition was introduced to refer to changes in the type and quantity of food available in different countries.5,6 The consistent analysis of these outcomes helps to evaluate similarities and variations in the transition from underweight to obesity, termed the obesity transition,7 across countries and age groups, and helps to bridge the gap between knowledge and policies focused on undernutrition and obesity.

Methods

Study design

To estimate trends in underweight and obesity in national populations from 1990 to 2022, we pooled population-based studies with measurements of height and weight. Pooled data were analysed using a Bayesian hierarchical meta-regression model. Our primary outcome was the individual and combined prevalence of underweight (adults; age ≥20 years) or thinness (school-aged children and adolescents; age 5–19 years) and obesity. On the basis of previous work,1 we conducted separate analyses for adults and for children and adolescents because cutoffs for underweight and obesity differ between them.8 Under-weight was defined as a BMI of less than 18·5 kg/m2 and thinness as BMI less than two SD below the median of the WHO growth reference.8 Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher for adults and a BMI of more than two SD above the median of the WHO growth reference for children and adolescents.8,9 We estimated trends in these outcomes for 200 countries and territories.

Data

We pooled population-based studies with measurements of height and weight in samples of the general population from a database collated by the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Details of the data sources are provided in previous publications1–4,10,11 and in the appendix (pp 47–51).

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using a Bayesian hierarchical meta-regression model. The statistical methods are detailed in previous publications4,11,12 and in the appendix (pp 52–64). In summary, the model had a hierarchical structure in which estimates for each country and year were informed by its own data, if available, and by data from other years in the same country and from other countries, especially those in the same region with data for similar time periods. The extent to which estimates for each country-year were influenced by data from other years and other countries depended on whether the country had data, the sample size of data, whether the data were at the national, subnational, or community level, and the within-country and within-region variability of the available data. The model incorporated non-linear time trends and age associations. The model accounted for the possibility that BMI in subnational and community studies might systematically differ from, and have larger variation than, nationally representative samples, as well as for urban-rural differences in BMI. We fitted the statistical model with the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. Posterior estimates were made in 1-year age groups for ages 5–19 years and in 5-year age groups for ages 20 years and older.

We calculated the prevalence of double burden as the sum of the prevalence of underweight or thinness and obesity. We also calculated the proportion (share) of the combined prevalence that was from obesity. We report age-standardised prevalence and proportions. Estimates were age-standardised using age weights from the WHO standard population.13 The number of people who were affected by underweight, thinness, and obesity was calculated by multiplying the corresponding age-specific prevalence by the age-specific population by sex, country, and year. We report Pearson correlation coefficients (r) among specific quantities of interest as a measure of their association.

All calculations were done at the posterior draw level. The reported credible intervals (CrIs) represent the 2·5th–97·5th percentiles of the posterior distributions, which contains the true estimates with 95% probability. We obtained the posterior probability that an estimated change represented a true increase as the proportion of draws from the posterior distribution that indicated an increase. We obtained the posterior probability that obesity was more prevalent than underweight as the proportion of posterior draws for which obesity prevalence was greater than underweight prevalence; we did the equivalent for underweight being more prevalent than obesity. Analyses were performed in R (version 4.2.0).

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

The results of this study can be explored using visualisations and downloaded from the NCD-RisC website. Results presented in this report are age-standardised as described in the Methods.

A list of data sources and their characteristics is provided in the appendix (pp 66–134), along with visualisations of data availability (appendix pp 137–140). We used 3663 studies with height and weight measurements from 222 million participants aged 5 years and older, including 63 million aged 5–19 years. We had at least one study for 197 (99%) of the 200 countries for which estimates were made; 196 (98%) had data for adults and 190 (95%) for children and adolescents. Data were most scarce in Oceania (average of 5·3 studies per country) and sub-Saharan Africa (7·6 per country), with all other regions having more than ten studies per country on average (appendix pp 139–140). The high-income western region (consisting of high-income English-speaking countries, northwestern Europe, and southwestern Europe; appendix p 135) had the most data (49·0 studies per country).

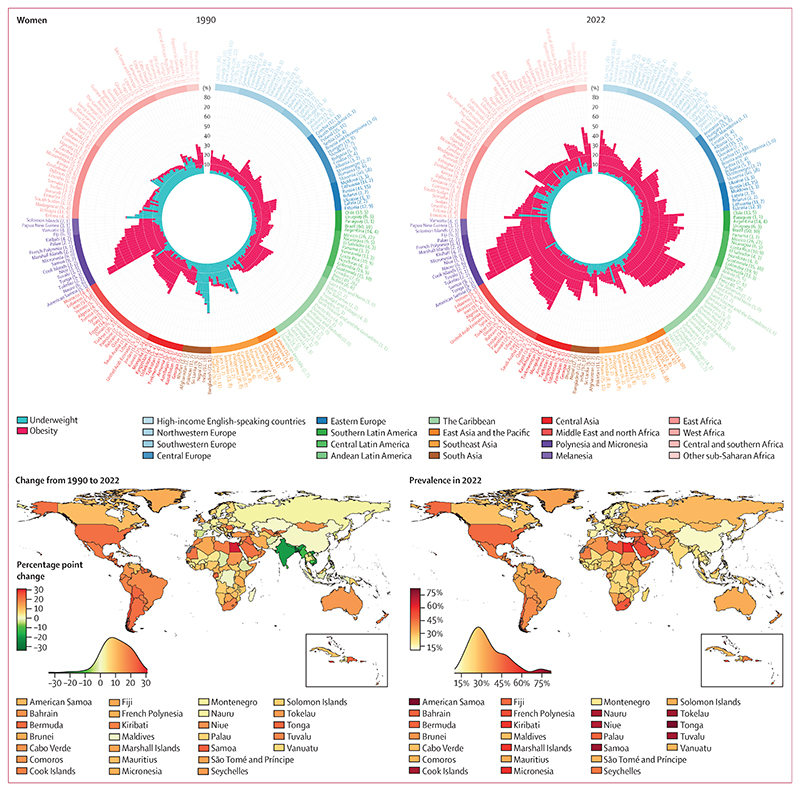

In 1990, the combined age-standardised prevalence of underweight and obesity in adults (age ≥20 years) was lowest in South Korea for both women (8·0%, 95% CrI 6·6–9·6) and men (5·2%, 4·1–6·5; figure 1). The combined prevalence was less than 10% in 19 other countries (10% of countries) for men, but surpassed 10% in all other countries for women. Combined age-standardised prevalence was more than 40% in 15 countries (8%) for women and seven countries (4%) for men. These countries were the island nations in Polynesia and Micronesia, where the dominant component of the double burden was obesity, as well as India (both sexes) and Bangladesh (women), where double burden was dominated by underweight. Combined prevalence was highest in American Samoa for women (70·6%, 67·8–73·4) and Nauru for men (66·3%, 63·0–69·5).

Figure 1. Age-standardised combined prevalence of underweight and obesity by country, for adults (age ≥20 years).

The circular bar plots show the burden of underweight and obesity in 1990 and 2022. The lengths of bars show the age-standardised prevalence of underweight (blue) and obesity (red), and their sum shows the age-standardised combined prevalence. Country names are coloured by region. The numbers in brackets after each country’s name show the total number of data sources and the number of nationally representative data sources, respectively. Countries are ordered by decreasing posterior mean combined prevalence within each region. The maps show the change in combined prevalence of underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022, and its level in 2022. The density plot alongside each map shows the smoothed distribution of estimates across countries.

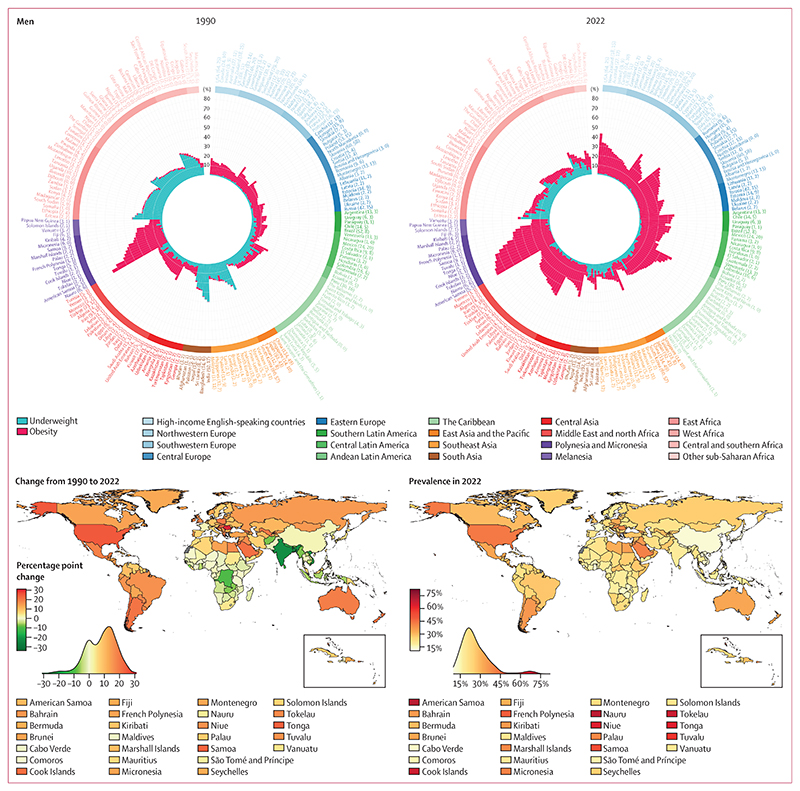

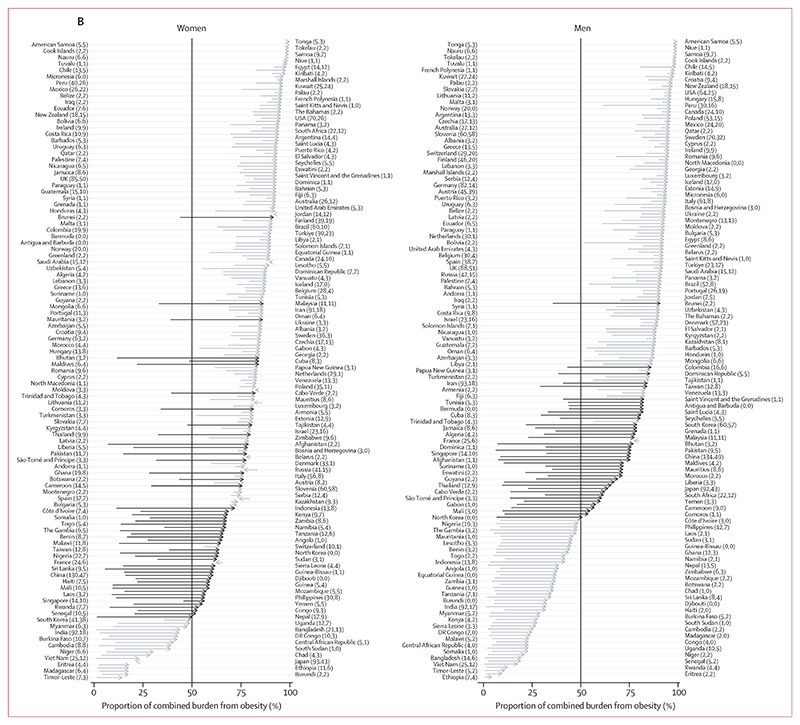

In 1990, underweight was more prevalent than obesity in adults, with a posterior probability of at least 0·80, in 65 countries (33%) for women and 89 (45%) for men (figure 2, appendix pp 163–164). Conversely, obesity was more prevalent than underweight in 128 countries (64%) for women and 104 (52%) for men. In the other seven countries each for women and men, the prevalence of the two conditions was indistinguishable at a posterior probability of 0·80. In 21 countries (11%) for women and 55 (28%) for men, more than 90% of the double burden was from underweight, whereas the share of double burden from obesity surpassed 90% in 18 countries (9%) for women and 21 (11%) for men. In 1990, the double burden was most dominated by underweight in countries in southeast Asia (Viet Nam, Timor-Leste, and Cambodia), south Asia (Bangladesh, India, and Nepal), and east Africa (Ethiopia and Eritrea) for both sexes. The double burden was most dominated by obesity in countries in Polynesia and Micronesia for both sexes, and in Kuwait for women.

Figure 2. Proportion of the double burden from obesity, for adults (age ≥20 years).

Age-standardised proportion of double burden that was from obesity in 1990 and 2022. The density plot alongside each map shows the smoothed distribution of estimates across countries.

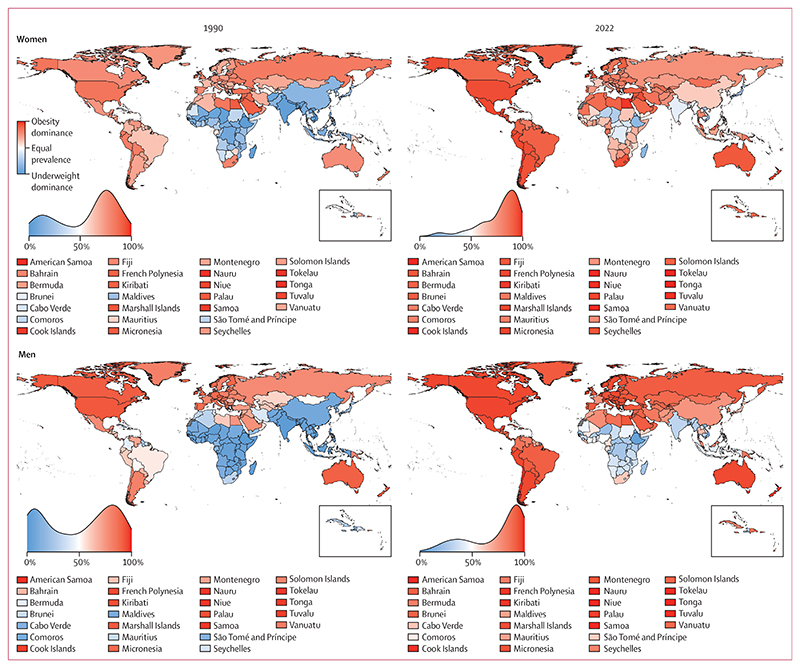

From 1990 to 2022, age-standardised prevalence of underweight among adults decreased in 129 countries (65%) for women and 149 (75%) for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 (figure 3, appendix pp 146–148). The largest absolute decreases were in countries in south Asia (eg, Bangladesh and India) and southeast Asia (eg, Viet Nam and Myanmar), with decreases of as much as 40·5 percentage points (95% CrI 35·0 to 45·9, posterior probability of being a true decrease >0·999) in women in Bangladesh and 27·3 percentage points (23·4 to 31·1, posterior probability >0·999) in men in India. The only groups that experienced an epidemiologically relevant increase in underweight—by more than two percentage points and with a posterior probability of at least 0·80—were women in Japan and South Korea. In 63 (32%) countries for women and 49 (25%) for men, neither an increase nor a decrease in underweight was detected at a posterior probability of 0·80; in the majority of these, age-standardised prevalence of underweight was already low (<10%) in 1990. The exceptions were men in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Somalia, and Uganda, and women in 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, for whom age-standardised underweight prevalence was more than 10% in 1990 but did not show a detectable decrease at a posterior probability of 0·80. Change in underweight was negatively correlated with its starting level (r= –0·83 [–0·88 to –0·77] for women and –0·80 [–0·89 to –0·68] for men; appendix pp 141–142), indicating that countries with higher underweight prevalence in 1990 experienced a larger decline on average.

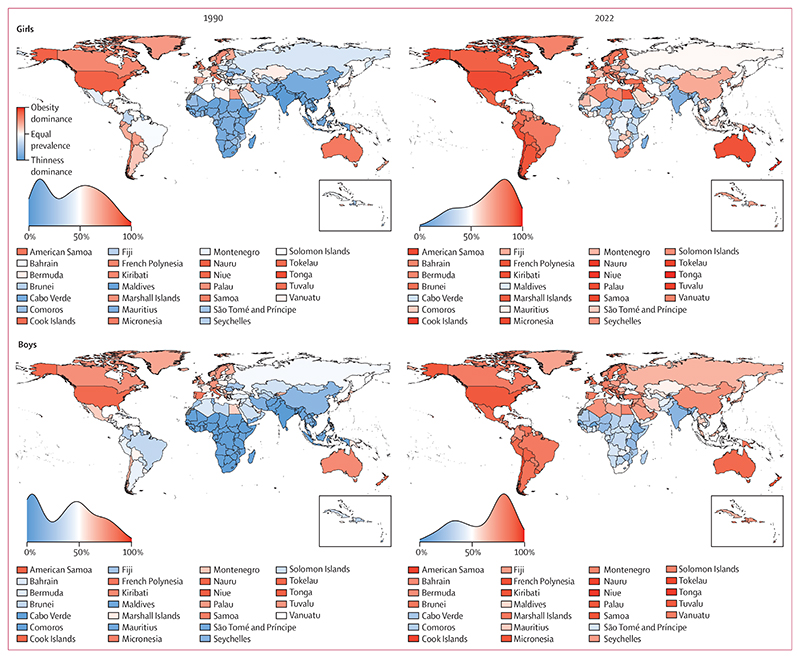

Figure 3. Change in the individual and combined prevalence of underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022, for adults (age ≥20 years).

(A) Contributions of change in underweight and obesity prevalence to the change in their combined prevalence from 1990 to 2022. The blue and red bars show the change in age-standardised prevalence of underweight and obesity, respectively, and the points show the change in the age-standardised combined prevalence. (B) Change in the composition of double burden from 1990 to 2022. The arrows start from the age-standardised proportion of double burden that was from obesity in 1990 and end at the age-standardised proportion from obesity in 2022; they are ordered by the posterior mean proportion in 2022. The arrows in a darker shade show countries where double burden shifted from underweight dominance to obesity dominance. In A and B, the numbers in brackets after each country’s name show the total number of data sources and the number of nationally representative data sources, respectively.

Age-standardised prevalence of obesity in adults increased from 1990 to 2022 in 188 countries (94%) for women and in all except one country for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 (figure 3, appendix pp 149–151). The largest increases were in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa for women; the USA, Brunei, and some countries in central Europe and Polynesia and Micronesia for men; and some countries in the Caribbean and in the Middle East and north Africa for both sexes. Age-standardised prevalence of obesity increased by more than 20 percentage points in 49 countries (25%) for women and 24 countries (12%) for men, and by as much as 33·0 percentage points (95% CrI 23·0 to 42·3, posterior probability >0·999) in The Bahamas for women and 31·7 percentage points (25·3 to 38·1, posterior probability >0·999) in Romania for men. It decreased only among women in Spain (by 4·6 percentage points [1·1 to 7·8, posterior probability 0·995]) and France (2·2 percentage points [–0·8 to 5·1, posterior probability 0·927]). In women in the remaining ten countries, mostly in Europe, and in men in France, neither an increase nor a decrease was detected at a posterior probability of 0·80. Unlike underweight, the correlation between change in obesity and its 1990 level was weak (r=0·13 [0·01 to 0·24] for women and 0·31 [0·13 to 0·47] for men). Furthermore, at 1990 baseline obesity levels of 5% or higher (appendix pp 141–142), the correlation was almost non-existent (r= –0·04 [–0·16 to 0·09] for women and –0·08 [–0·31 to 0·15] for men), indicating that the extent of increase in obesity was largely unrelated to how prevalent it was in 1990. There was no correlation between change in obesity and change in underweight for women (r= –0·02 [–0·10 to 0·05]) but a weak positive correlation was found for men (r= 0·29 [0·14 to 0·43]).

In 2022, the prevalence of obesity was less than 5% among women in six countries (3%; Viet Nam, Timor-Leste, Japan, Burundi, Madagascar, and Ethiopia) and among men in 17 countries (9%) in south and southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. It surpassed 60% among women in eight countries (4%) and men in six countries (3%), all in Polynesia and Micronesia. The range of underweight prevalence across countries in 2022 was smaller than the range of obesity prevalence, and prevalence surpassed 20% only among women in Timor-Leste and four countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and among men in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa (figure 1).

The net effect of changes in underweight and obesity in adults was that their combined age-standardised prevalence decreased in 11 countries (6%) for women and 17 countries (9%) for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80, and increased in 162 countries (81%) for women and 140 countries (70%) for men with a posterior probability of at least 0·80, from 1990 to 2022 (figure 3, appendix pp 152–153). Countries where the double burden decreased were mostly in south and southeast Asia for both sexes, and in sub-Saharan Africa for men. Among women in sub-Saharan Africa, however, the decline in underweight was counteracted by a rise in obesity, such that their combined prevalence either changed little or increased (figures 1, 3). Decreases in the double burden of underweight and obesity were driven by decreases in underweight, with the exception of women in Spain, for whom the decrease was driven by a decline in obesity.

Bangladesh, India, and Viet Nam experienced the largest decreases in double burden among adults for both sexes, with decreases by 33·1 percentage points (95% CrI 27·4–38·7, posterior probability >0·999) among women in Bangladesh and 22·4 percentage points (18·5–26·2, posterior probability >0·999) among men in India (figures 1, 3). Mirroring the declines, the increase in combined prevalence of underweight and obesity in most countries was due to the rise in obesity exceeding a decline in underweight. As a result, countries that experienced a large increase in double burden were the same as those that had a large increase in obesity. The largest increases in double burden among women were in Egypt (31·0 percentage points, 25·4–36·6, posterior probability >0·999), followed by The Bahamas and Jamaica, and among men in Romania (30·5 percentage points, 24·0–37·0, posterior probability >0·999), followed by the USA and Tonga.

In 2022, the combined prevalence of underweight and obesity in adults was more than 10% in all countries (figure 1). It was between 10% and 15% for women in four countries (South Korea, China, Viet Nam, and Denmark) and men in 17 countries (9%). South Korea and China had the lowest combined prevalence for women, and Sierra Leone, South Korea, and China had the lowest combined prevalence for men. At the other extreme, combined underweight and obesity prevalence was 40% or higher in 55 countries (28%) for women and 16 (8%) for men. The prevalence was highest in American Samoa (81·7%, 73·6–88·8 for women; 70·6%, 59·8–79·8 for men), followed by other island nations in Polynesia and Micronesia and the Caribbean (eg, The Bahamas and Saint Kitts and Nevis), and countries in the Middle East and north Africa (Egypt for women, Qatar for men). Outside of these regions, men in the USA also had a high prevalence of double burden (43·0%, 39·1–47·1), as did women in South Africa (49·6%, 45·1–54·2). The number of countries where underweight was more prevalent than obesity among adults with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 decreased from 65 (33%) in 1990 to 16 (8%) in 2022 for women, and from 89 (45%) to 39 (20%) for men (figure 2). In 2022, all such countries were in sub-Saharan Africa, southeast Asia, and south Asia, with the exceptions of Haiti (for men) and Japan (for women).14 Obesity prevalence was higher than underweight with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 in 177 countries (89%) for women and 145 countries (73%) for men in 2022. The largest absolute increases in the proportion of double burden from obesity were in countries in south Asia (eg, Bhutan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan), southeast Asia (eg, Maldives and Malaysia), and west Africa (eg, Liberia) for both sexes, and in east Asia and the Pacific (eg, China) for men. In 50 countries (25%) for women and 41 countries (21%) for men, double burden shifted from underweight dominance to obesity dominance (figure 3). By 2022, more than 90% of double burden consisted of obesity in 67 countries (34%) for women and 88 (44%) for men. These countries were predominantly in Oceania, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and north Africa, and the high-income western region for both sexes, and in central and eastern Europe for men. The share of double burden from underweight surpassed 90% only among men in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Further results for adults are provided in the appendix, including separate results for ages 20–39 years, 40–64 years, and 65 years and older (appendix pp 156–162, 165–168, 172–179); results on the levels of all BMI categories (appendix pp 143–145); maps of the age-standardised prevalence of underweight in 1990 and 2022, change from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that underweight increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 146–148); maps of the age-standardised prevalence of obesity in 1990 and 2022, change from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that obesity increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 149–151); maps of the posterior probability that the age-standardised combined prevalence increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 152–153); trends in underweight, obesity, and their combined prevalence from 1990 to 2022, together with their 95% CrIs, for all countries (appendix pp 204–404); maps of change in the proportion of double burden that was from obesity from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that the proportion of double burden that was from obesity increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 154–155); the uncertainty (posterior SD) of the proportion of double burden that was from obesity (appendix pp 163–164); and the uncertainty (posterior SD) of the changes in underweight, obesity, their combined prevalence, and the proportion of the combined prevalence that was from obesity, from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 169–171).

The global age-standardised prevalence of underweight in adults decreased from 14·5% (95% CrI 14·0–15·0) in 1990 to 7·0% (6·5–7·5) in 2022 in women and from 13·7% (13·0–14·4) to 6·2% (5·6–6·9) in men. 183 million (169–197) women and 164 million (148–180) men were underweight in 2022, a decrease of 44·9 million (28·5–61·0) and 47·6 million (27·1–66·7), respectively, from 1990, despite global population growth. The countries with the largest number of adults with underweight in 2022 were India, China, Japan (for women only), Indonesia, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh. Age-standardised prevalence of underweight in Ethiopia, Bangladesh, India, and Japan (for women) ranged from 11% to 26% and ranked in the 25 highest countries, which, together with large populations, led to large numbers of people with under-weight. The relatively high prevalence of underweight among women (but not men) in Japan, the only high-income country in this group, has been attributed to perceived weight being higher than actual weight, and higher than desired weight.14 Underweight prevalence was lower in Indonesia (6·6% [4·7–8·8] and 10·6% [7·1–14·6] for women and men, respectively) and especially in China (5·9% [4·6–7·4] and 2·9% [1·9–4·0], ranking 61st-highest and 97th-highest globally). Nonetheless, when combined with the large populations in these countries, even this low or moderate prevalence led to large absolute numbers. The global age-standardised prevalence of obesity increased from 8·8% (8·5–9·1) in 1990 to 18·5% (17·9–19·1) in 2022 in women and from 4·8% (4·6–5·0) to 14·0% (13·4–14·6) in men. The global age-standardised prevalence of obesity overtook that of underweight in 2003 (2003–2004) for women and 2009 (2008–2010) for men. The number of women and men with obesity in 2022 was 504 million (489–520) and 374 million (358–391), respectively, which was an increase of 377 million (360–393) and 307 million (290–324), respectively, from 1990. The countries with the largest absolute numbers of adults with obesity in 2022 were the USA, China, and India.

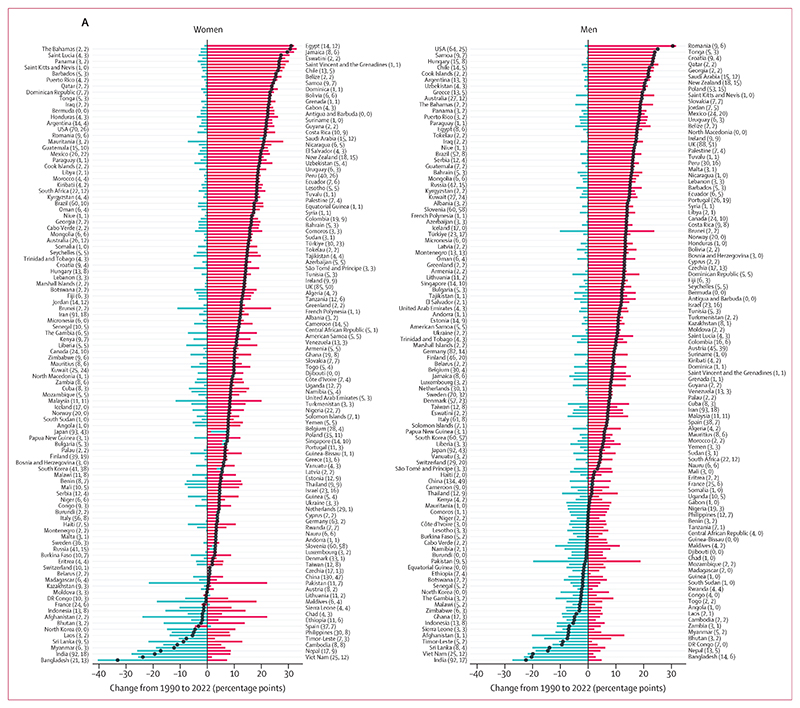

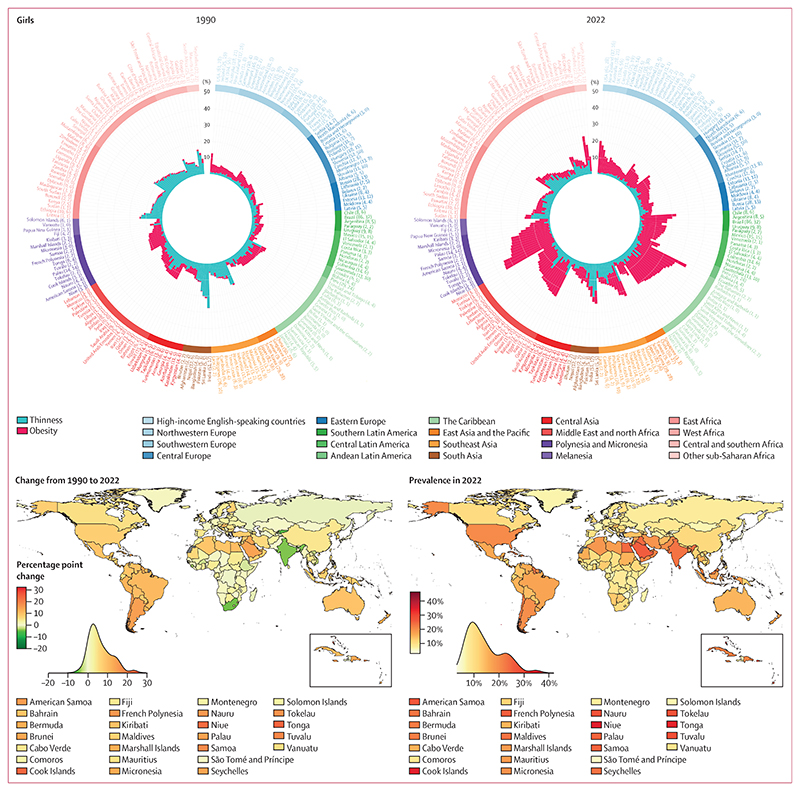

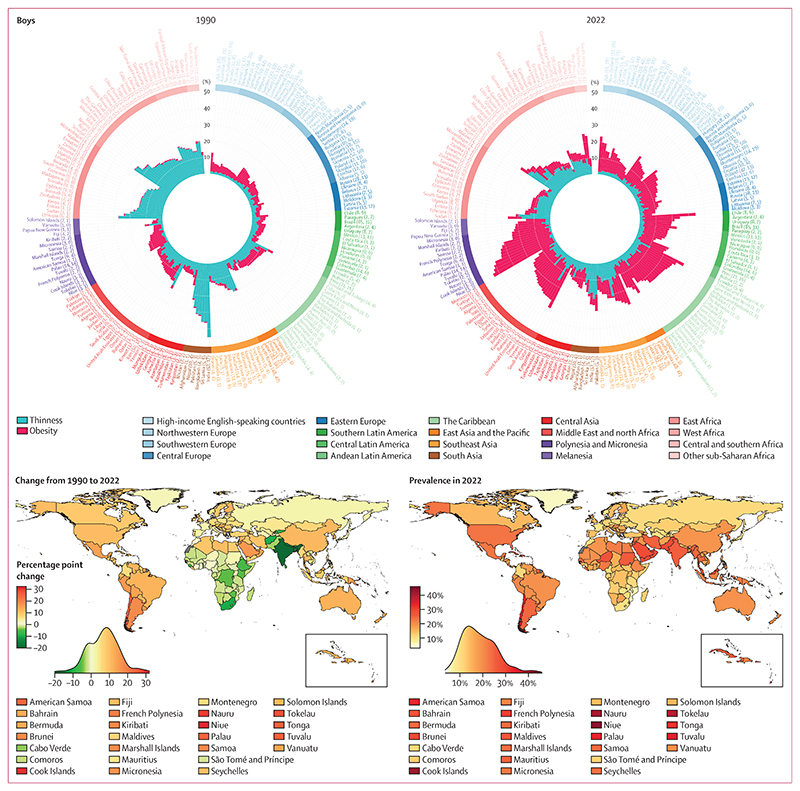

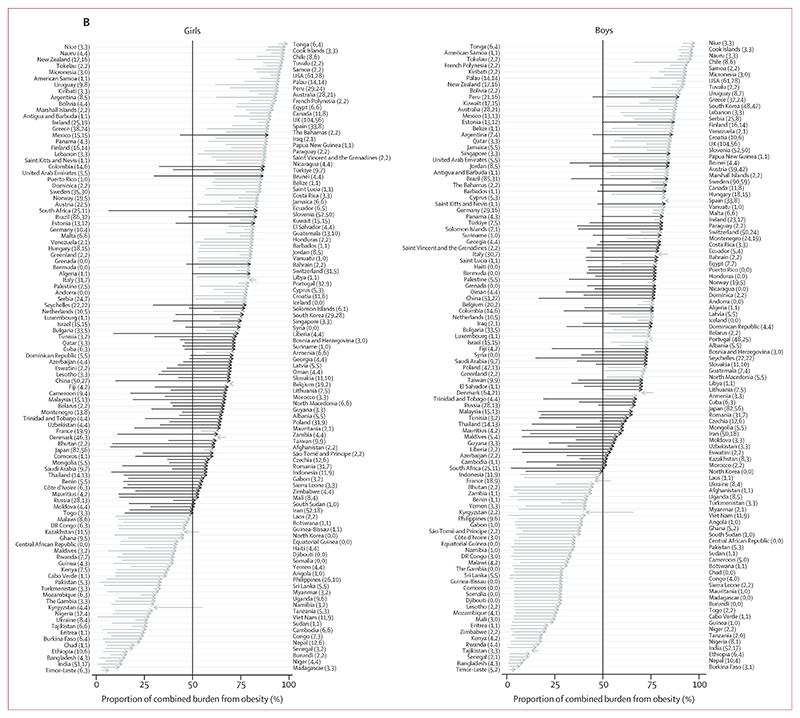

In 1990, the contribution of thinness to the double burden of thinness and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents (age 5–19 years) was larger than the corresponding share of underweight in adults, especially for boys. Specifically, in 93 countries (47%) for each sex, the age-standardised prevalence of thinness was greater than that of obesity with a posterior probability of at least 0·80; conversely, the prevalence of obesity was greater than that of thinness in 52 countries (26%) for girls and 47 countries (24%) for boys (figures 4, 5; appendix pp 195–196). In the other 55 countries (28%) for girls and 60 countries (30%) for boys, the prevalence of the two forms of malnutrition were indistinguishable at a posterior probability of 0·80. In 34 countries (17%) for girls and in 64 (32%) for boys, mostly in south and southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, more than 90% of double burden consisted of thinness, whereas the opposite (>90% of double burden from obesity) occurred in some countries in Polynesia and Micronesia for both sexes, and in the USA for girls.

Figure 4. Age-standardised combined prevalence of thinness and obesity by country, for school-aged children and adolescents (age 5–19 years).

The circular bar plots show the burden of thinness and obesity in 1990 and 2022. The lengths of the bars show the age-standardised prevalence of thinness (blue) and obesity (red), and their sum shows the age-standardised combined prevalence. Country names are coloured by region. The numbers in brackets after each country’s name show the total number of data sources and the number of nationally representative data sources, respectively. Countries are ordered by decreasing posterior mean combined prevalence within each region. The maps show the change in combined prevalence of thinness and obesity from 1990 to 2022 and its level in 2022. The density plot alongside each map shows the smoothed distribution of estimates across countries.

Figure 5. Proportion of double burden from obesity for school-aged children and adolescents (age 5–19 years).

Age-standardised proportion of double burden that was from obesity in 1990 and 2022. The density plot alongside each map shows the smoothed distribution of estimates across countries.

India experienced the highest age-standardised prevalence of double burden in school-aged children and adolescents in 1990 (27·4% [95% CrI 24·3–30·7] for girls and 45·3% [42·1–48·5] for boys, with 99·6% [99·3–99·8] and 99·7% [99·5–99·9], respectively, consisting of thinness). Age-standardised prevalence was between 30% and 40% for boys in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, with 98–99% of double burden coming from thinness (figures 4, 5). Kuwait and Egypt were also among the top ten countries for girls in terms of double burden, but unlike the aforementioned countries where thinness was dominant, more than 70% of double burden came from obesity. Age-standardised prevalence of obesity in 1990 surpassed 10% in only seven countries (4%) for girls and six (3%) for boys, including the USA and some countries in Polynesia and Micronesia and the Middle East and north Africa, whereas thinness surpassed 10% in 20 countries (10%) for girls and 67 countries (34%) for boys.

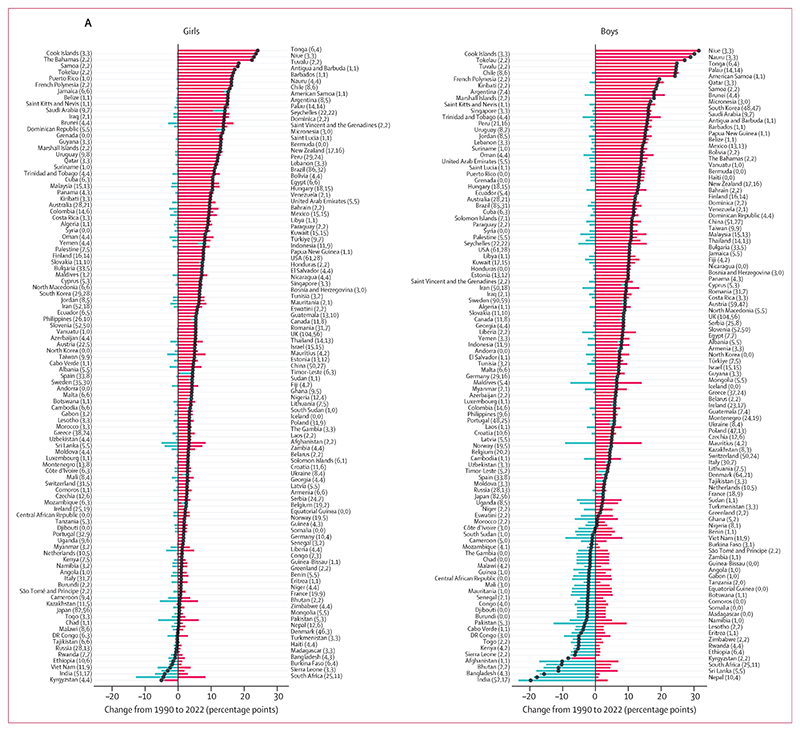

From 1990 to 2022, age-standardised prevalence of thinness decreased in girls in 44 countries (22%) and boys in 80 countries (40%) with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 (figure 6). The largest decreases took place in countries in south and southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (figures 4, 5), with the greatest decreases in South Africa (decrease of 12·7 percentage points [95% CrI 6·8 to 19·8]) and India (7·0 [2·2 to 11·9]) for girls, and India (23·5 [18·5 to 28·4]) and Nepal (18·7 [9·1 to 28·7]) for boys. Like in adults, change in thinness was negatively correlated with the starting level of thinness (r= –0·53 [–0·70 to –0·33] for girls and –0·79 [–0·90 to –0·62] for boys; appendix pp 180–181), indicating that larger declines occurred where thinness was more common in 1990. However, in some countries, such as Yemen, Niger, and Myanmar, age-standardised thinness prevalence was at least 10% in 1990 but did not change from 1990 to 2022 with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 (appendix pp 185–187). Thinness increased by at least two percentage points and with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 in three countries for girls and one country for boys.

Figure 6. Change in the individual and combined prevalence of thinness and obesity from 1990 to 2022, for school-aged children and adolescents (age 5–19 years).

(A) Contributions of change in thinness and obesity to the change in their combined prevalence from 1990 to 2022. The blue and red bars show the change in age-standardised prevalence of thinness and obesity, respectively, and the points show the change in the age-standardised combined prevalence. (B) Change in the composition of double burden from 1990 to 2022. The arrows start from the age-standardised proportion of double burden that was from obesity in 1990 and end at the age-standardised proportion in 2022; they are ordered by the posterior mean proportion in 2022. The arrows in a darker shade show countries where double burden shifted from thinness dominance to obesity dominance. In A and B, the numbers in brackets after each country’s name show the total number of data sources and the number of nationally representative data sources, respectively.

Over the same period, age-standardised prevalence of obesity increased in girls in 186 countries (93%) and in boys in 195 countries (98%) with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 (figure 6, appendix pp 188–190). In most countries, obesity more than doubled (appendix pp 180–181). Obesity decreased with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 only in Kyrgyzstan, by 4·1 percentage points (95% CrI 1·3 to 7·3) for girls and 7·2 percentage points (2·8 to 11·6) for boys. In the remaining 13 countries (7%) for girls and four countries (2%) for boys, mostly in Europe and central Asia, neither an increase nor a decrease was detected at a posterior probability of 0·80. The largest increases in child and adolescent obesity were in the island nations of Polynesia and Micronesia and the Caribbean, Brunei, and Chile. The size of the increase surpassed 20 percentage points among girls in Tonga, Cook Islands, Niue, and The Bahamas, and surpassed 25 percentage points among boys in Niue, Cook Islands, Nauru, Tokelau, and Chile. Like in adults, there was weak correlation between obesity in 1990 and change from 1990 to 2022 (r=0·37 [0·19 to 0·54] for girls and 0·30 [0·11 to 0·47] for boys; appendix pp 180–181). In particular, in many countries in Europe, Japan, the USA, and some countries in central Asia, an increase in child and adolescent obesity was either not detectable at a posterior probability of 0·80 or was smaller than in countries elsewhere that had a similar prevalence in 1990. There was no or weak correlation between change in thinness and change in obesity (r= –0·02 [–0·17 to 0·12] for girls and 0·14 [–0·04 to 0·30] for boys).

In 2022, age-standardised prevalence of thinness was less than 15% for girls in all countries except India and Sri Lanka, and below 20% among boys in all countries except Niger, India, Senegal, and Timor-Leste (figure 4). By contrast, age-standardised prevalence of obesity was more than 20% in girls in 21 countries (11%) and boys in 35 countries (18%), with the highest prevalence in Niue for both girls (34·3%, 95% CrI 23·5–44·7) and boys (42·9%, 31·6–53·4). These countries were mostly in Polynesia and Micronesia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East and north Africa.

As a result of changes in thinness and obesity, by 2022, double burden in school-aged children and adolescents began to mirror the obesity dominance that was seen in adults throughout these three decades. Specifically, in 2022, obesity in school-aged children and adolescents was more prevalent than thinness with a posterior probability of at least 0·80 among girls in 133 countries (67%) and boys in 125 countries (63%), whereas the opposite was true in 35 (18%) and 42 countries (21%), respectively (figure 5, appendix pp 195–196). In 25 countries (13%) for girls and 17 countries (9%) for boys, more than 90% of double burden consisted of obesity in 2022, whereas the share of thinness surpassed 90% only among girls and boys in Timor-Leste, and boys in Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The largest shifts in the thinness–obesity share of double burden in school-aged children and adolescents were in South Africa for girls, with the share of obesity increasing by 77·2 percentage points (95% CrI 64·3–86·7, posterior probability >0·999), and in China for boys, with an increase of 60·5 percentage points (50·4–69·4, posterior probability >0·999; figure 6).

The combined prevalence of thinness and obesity declined with posterior probability of at least 0·80 among girls in India, Kyrgyzstan, Sierra Leone, South Africa, and Viet Nam, and among boys in 15 countries (8%), all of which were in central Asia, south Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa (figure 6, appendix pp 191–192). With the exception of Kyrgyzstan, the declines in the double burden were driven by declines in the prevalence of thinness. The largest declines were in Kyrgyzstan (5·1 percentage points, 95% CrI 1·0–9·2, posterior probability 0·991) for girls and in India (19·7 percentage points, 14·7–24·8, posterior probability >0·999) for boys. The combined burden of thinness and obesity increased with posterior probability of at least 0·80 among girls in 140 countries (70%) and boys in 137 countries (69%). The largest increases were in some countries in Polynesia and Micronesia and the Caribbean for both sexes, and in Chile for boys, with the size of the increase reaching 24·1 percentage points (12·7–34·6, posterior probability >0·999) in girls in Tonga and 31·1 percentage points (16·4–44·6, posterior probability >0·999) in boys in Niue.

In 2022, the combined age-standardised prevalence of thinness and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents was less than 10% in 70 countries (35%) for girls and 16 countries (8%) for boys (figure 4). In these countries, thinness either remained low throughout the analysis period or declined, and obesity did not rise noticeably. These countries were mostly in central Asia, Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa. At the other extreme, the countries with highest combined prevalence of thinness and obesity in 2022 were in Polynesia and Micronesia and the Caribbean for both sexes, plus Chile and Qatar for boys. Double burden prevalence was also high in some countries in south Asia, notably Sri Lanka and India, where thinness remained prevalent despite its decline.

Further results for children and adolescents are shown in the appendix, including levels of all BMI categories (appendix pp 182–184); maps of the age-standardised prevalence of thinness in 1990 and 2022, change from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that thinness increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 185–187); maps of the age-standardised prevalence of obesity in 1990 and 2022, change from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that obesity increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 188–190); maps of the posterior probability that the age-standardised combined prevalence increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 191–192); trends in thinness, obesity, and their combined prevalence from 1990 to 2022, together with their 95% CrIs, for all countries (appendix pp 204–404); maps of change in the proportion of double burden from obesity from 1990 to 2022, and posterior probability that the proportion of double burden from obesity increased from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 193–194); the uncertainty (posterior SD) of the proportion of double burden from obesity (appendix pp 195–196); and the uncertainty (posterior SD) of the changes in thinness, obesity, their combined prevalence, and the proportion of the double burden from obesity, from 1990 to 2022 (appendix pp 197–199).

The global age-standardised prevalence of thinness among school-aged children and adolescents decreased from 10·3% (95% CrI 9·5–11·1) in 1990 to 8·2% (7·3–9·0) in 2022 in girls and from 16·7% (15·6–17·8) to 10·8% (9·7–11·9) in boys (posterior probability >0·999). A total of 77·0 million (69·1–84·9) girls and 108 million (98–119) boys were affected by thinness in 2022, a decrease of 4·4 million (95% CrI ranging from an increase of 5·6 million to a decrease of 14·6 million) for girls and 30·1 million (15·6–44·3) for boys from 1990. The global age-standardised prevalence of obesity in school-aged children and adolescents increased from 1·7% (1·5–2·0) in 1990 to 6·9% (6·3–7·6) in 2022 in girls and from 2·1% (1·9–2·3) to 9·3% (8·5–10·2) in boys (posterior probability >0·999). The number of girls and boys with obesity in 2022 was 65·1 million (59·4–71·7) and 94·2 million (85·3–103·0), respectively, an increase of 51·2 million (45·2–57·8) and 76·7 million (67·6–85·7), respectively, from 1990.

Discussion

Our results show three important global transitions in underweight and obesity since 1990. First, the combined prevalence of these forms of malnutrition has increased in most countries, with the notable exception of countries in south and southeast Asia and, for some age-sex groups, in sub-Saharan Africa. Second, decreases in the double burden were largely driven by declining prevalence of underweight, whereas increases were driven by increasing obesity, leading to a transition from underweight dominance to obesity dominance in many countries. The rise in double burden has been largest in some low-income and middle-income countries, notably those in Polynesia and Micronesia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East and north Africa; newly high-income countries such as Chile; and, for men, in central Europe. These countries now have higher obesity prevalence than industrialised high-income countries. Finally, the transition to obesity was already apparent in adults in 1990 in much of the world, as demonstrated by the large number of countries in which adult obesity exceeded underweight at that time, and has since followed in school-aged children and adolescents.7

Our study has strengths related to its scope, data, and methods. We present consistent estimates of underweight and obesity, and their combined prevalence, over a period of substantial change in food and nutrition. We used a large amount of population-based data, from 197 countries covering more than 99% of the world’s population. We maintained a high standard of data quality through repeated checks of study sample and characteristics, and did not use self-reported data to avoid bias. Data were analysed according to a consistent protocol. We used a statistical model that accounted for the age patterns of BMI during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. We used all available data while giving more weight to national data than to subnational and community data.

As with all global analyses, our study has limitations. Some countries had fewer data and three had none; their estimates were informed to a stronger degree by data from other countries through geographical hierarchy. There were also differences in data availability by age group, with less data available for ages 5–9 years, and in older adults (≥65 years), which increased the uncertainty of estimates in these age groups. Despite our systematic and rigorous process of evaluating study representativeness, data from health surveys are subject to error if sample weights do not fully adjust for non-response. We did not report on height, a marker of the quality of nutrition and the living environment, and predictive of health throughout the life course,15 as reported previously.4,11 BMI is an imperfect measure of the extent and distribution of body fat, but is widely available in population-based surveys, and is used in clinical practice; it is also correlated with the more complex and costly dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.16 Cutoffs for thinness and obesity for school-aged children and adolescents are based on BMI distributions in a reference population, and were not selected to represent optimal BMI in epidemiological studies, as was done for adults, or optimal nutritional status, as for children younger than 5 years.8,9 Finally, various hypotheses exist about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on BMI. Data on the impact of the pandemic on obesity are scarce,17 and there are even fewer data on the impact on underweight. The available data on obesity, mostly from high-income countries, indicate a small rise in prevalence, with large heterogeneity across studies;17 it is unclear whether these effects are transitory or permanent. Studies from low-income and middle-income countries have indicated worsening food security and diet quality during and after the pandemic, but did not measure underweight prevalence.18 We used 103 studies from 2020 and later, but additional data are needed to evaluate the population-level effects. Finally, although our statistical model has been shown to be unbiased and have small deviation (ie, random error) in cross-validation analyses,3,10 fitting to data that vary in relation to age, country, and year has the potential for model misspecification.

Height and weight are affected by the quantity and quality of nutrition, energy expenditure, and some infections.19,20 For decades before the COVID-19 pandemic, higher incomes allowed more spending on food, especially in poor countries and households where a large share of income is spent on food.21 Meanwhile, as food production, distribution, and storage changed, there was a shift from subsistence and local foods to transported commercial foods, and the time spent obtaining and preparing food was reduced.22–24 These economic and technological changes have affected both the amount and types of food that are consumed, including higher total calories, and higher consumption of animal-source foods, sugar, vegetables, and oil crops in many low- and middle-income countries, whereas animal-source foods and possibly sugar consumption have declined in high-income countries.25–29 Furthermore, changes in food processing technology and increasing commercialisation and industrialisation of food30 have increased the consumption of processed foods, which leads to higher caloric intake and weight gain than fibre-rich foods such as whole grains and fruits.31,32 In some countries, equitable economic and agricultural policies and food programmes have improved the quality of nutrition, especially for the poor,33–36 resulting in gains in height, whereas elsewhere weight gain occurred without substantial height gain, leading to increasing obesity.4,11,19,37 These height gains were similar to those in Europe and north America during industrialisation and economic development.38 Researchers have also detected a so-far unexplained decline in adult basal energy expenditure,39 which might have contributed to the rise in obesity.

The finding that obesity increased, and double burden shifted from underweight-dominated to obesity-dominated, earlier in adults than in children and adolescents40 might be due to two phenomena: first, adults began to eat away from home earlier than children and adolescents,41–43 and second, the mechanisation of work and transport, while providing many health benefits, also reduced energy expenditure, and hence contributed to weight gain among adults.44 The shift in onset of obesity to younger ages over these three decades could be because eating away from home and access to commercial and processed foods in school-aged children and adolescents followed that of adults over this period.45 It has also been hypothesised that some leisure-time play and sports have been replaced by sedentary activities, but data on trends are scarce.46 Breastfeeding, which improves child survival and development, has also been associated with a lower risk of obesity in observational studies but the findings from randomised trials are mixed, possibly because of reverse causality.47,48 In all regions except the Middle East and north Africa, optimal breastfeeding has increased slightly.49 However, any benefits of these improvements in reducing obesity are likely to have been overwhelmed by much larger changes in other aspects of nutrition. The reasons for the small decline in obesity among women in France and Spain, which was also seen in middle-age and older ages (approximately age ≥60 years) in other studies that used measurement data,50–52 are not known but could be related to changes in eating and exercise, following changes in social norms and roles.53

Our findings have two implications. First, there is an urgent need for obesity prevention, supporting weight loss and reducing disease risk (via treatment of the mediators of its hazards, such as hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia) in those with obesity. Prevention and management are especially important because the age of onset of obesity has decreased, which increases the duration of exposure. Most efforts to prevent obesity have focused on individual behaviours or isolated changes to the built or food environment.54 These have had little impact on obesity prevalence, in part because healthy foods and participating in sports and other active lifestyles are not accessible or affordable for people with low income and autonomy.55–59 In the past decade, some countries have regulated marketing and taxed items such as sugar-sweetened beverages;60 the impacts on obesity prevalence are currently being evaluated.61 There are fewer policies that make healthy foods accessible and affordable, especially for people with low income and in communities where such foods are scarce. Unaffordability and inaccessibility of healthy foods and opportunities for play and sports leads to inequalities in obesity, and could limit the impact of policies that target unhealthy foods.58,59,62,63 New pharmacological treatment of obesity, although promising, is likely to have a low impact globally in the short-term, due to high cost and the absence of generalisable clinical guidelines.

Second, the remaining burden of underweight should be tackled, especially in south and southeast Asia, and parts of Africa, where food insecurity persists.64,65 Our results show that this need cannot be considered in isolation, because the underweight–obesity transition can occur rapidly, leaving their combined burden unchanged or higher. A healthy transition away from high underweight prevalence while limiting the rise in obesity, consistent with the Sustainable Development Goal Target 2.2, requires improving access to healthy and nutritious foods. This is particularly important because both poverty and the cost of food, especially nutrient-rich foods, have increased since the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.65–67 Together with the adverse impact of climate change on food production and supply, these factors risk worsening both underweight and obesity through a combination of underconsumption in some countries and households, and a switch to less healthy foods in others.68,69 To engender a healthy transition, economic and agricultural policies are needed that tackle poverty and improve food security.70 As these macro policies are implemented, there is an urgent need for programmes that enhance healthy nutrition, such as targeted cash transfers, food assistance as subsidies or vouchers for healthy foods, free healthy school meals, and primary care-based nutritional interventions.71–75

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) for articles published from database inception up to Sept 25, 2023, with no language restrictions, using the following search terms: (((“obesity”[mh:noexp] OR “overweight”[mh:noexp] OR “overnutrition”[mh:noexp]) AND (“thinness”[mh:noexp] OR “malnutrition”[mh:noexp])) OR (“double burden” AND “malnutrition”)) AND (“Health Surveys”[mh] OR “Epidemiological Monitoring”[mh] OR “Prevalence”[mh]) AND (“global*” OR “worldwide”) NOT “patient*”[Title] NOT Comment[ptyp] NOT Case Reports[ptyp]. Articles were screened to include measured data on height and weight, collected from probabilistic samples of national, subnational, or community populations aged 5 years and older. We found two studies that reported the prevalence of underweight and obesity in adults, one of which also reported the prevalence of thinness and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents, for all countries in the world. These outcomes were reported separately, and neither their combination nor their relative sizes were evaluated. The most recent data for both age groups were from 2016. We found eight studies on the double burden of malnutrition in low-income and middle-income countries, using data mostly from Demographic and Health Surveys or Global School-based Student Health Surveys. These studies covered only women of reproductive age or school-aged children and adolescents, and few assessed change over time. We found two other studies that covered multiple world regions but they did not report country-level prevalence or assess change over time. These studies defined double burden of malnutrition at the level of the individual (eg, combination of stunting and obesity), household (eg, presence of underweight and obesity in different members of the same household), or country, depending on the study. None reported for all countries in the world.

Added value of this study

This study uses thousands of high-quality population-based studies, and presents consistent and up-to-date estimates of underweight, thinness, and obesity from late childhood through to adulthood, separately and in combination, for all countries in the world. It also analyses how the two components have contributed to the change in their combined burden over a period of more than three decades, 1990–2022, during which major changes occurred in food policies and programmes and nutrition.

Implications of all the available evidence

The combined prevalence of underweight and obesity has increased in most countries since 1990, due to the rise in obesity surpassing the decline in underweight. Exceptions were most countries in south Asia, and some in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where a decrease in the prevalence of underweight led to a decrease in the combined burden. This transition to obesity dominance was already apparent in adults in 1990 in much of the world, and has followed in school-aged children and adolescents. There is a need throughout the world for social and agricultural policies and food programmes that address the remaining burden of underweight while curbing and reversing the rise in obesity by enhancing access to healthy and nutritious foods.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (grant number MR/V034057/1), the UK Research and Innovation (Research England Policy Support Fund), UK Research and Innovation (Innovate UK grant number 10103595, for participation in the OBCT consortium funded by the European Union grant agreement 101080250), and European Union (STOP Project grant agreement 774548). BZ is supported by a fellowship from the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics at Imperial College London, funded by a donation from Community Jameel. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to the Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this Article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Footnotes

Contributors

Members of the country and regional data group collected and reanalysed data and checked pooled data for accuracy of information about their study and other studies in their country. RKS, BZ, RAH, NHP, AM, VPFL, RMCL, GAS, AWR, and AFBP collated data from different studies. RKS, BZ, and RAH managed the database. NHP, BZ, AM, JEB, and JB adapted the statistical model with input from CJP and ME. NHP analysed data and prepared results. ME, NHP, and RKS wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from other members of the pooled analysis and writing group. Members of the country and regional data group commented on the draft report. ME oversaw research. Members of the country and regional data group had access to and verified data from individual participating studies. RKS, NHP, BZ, and RAH had access to and verified the pooled data used in the analysis. The corresponding author had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests

JLB reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk Denmark and voluntary work at the European Association for the Study of Obesity, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Editorial note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC):

Pooled analysis and writing and Country and regional data

Data sharing

Age-standardised and age-specific results of this study, as well as the computer code and input data for the analyses, can be downloaded from https://www.ncdrisc.org. Computer code and input data are also available from the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10534960). Input data are provided where permitted by data governance and sharing arrangements; contact information is provided for other data sources.

References

- 1.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Heterogeneous contributions of change in population distribution of body mass index to change in obesity and underweight. eLife. 2021;10:e60060. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature. 2019;569:260–64. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1171-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Diminishing benefits of urban living for children and adolescents’ growth and development. Nature. 2023;615:874–83. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler J. Epidemic obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1040–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popkin BM, Paeratakul S, Zhai F, Ge K. A review of dietary and environmental correlates of obesity with emphasis on developing countries. Obes Res. 1995;3(suppl 2):145s–53s. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaacks LM, Vandevijvere S, Pan A, et al. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:231–40. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–67. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Onis M, Lobstein T. Defining obesity risk status in the general childhood population: which cut-offs should we use? Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:458–60. doi: 10.3109/17477161003615583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Height and body-mass index trajectories of school-aged children and adolescents from 1985 to 2019 in 200 countries and territories: a pooled analysis of 2181 population-based studies with 65 million participants. Lancet. 2020;396:1511–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takimoto H, Yoshiike N, Kaneda F, Yoshita K. Thinness among young Japanese women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1592–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner JM. Growth as a mirror of the condition of society: secular trends and class distinctions. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1987;29:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1987.tb00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Calvo N, Moreno-Galarraga L, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Association between body mass index, waist-to-height ratio and adiposity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8:512. doi: 10.3390/nu8080512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson LN, Yoshida-Montezuma Y, Dewart N, et al. Obesity and weight change during the COVID-19 pandemic in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2023;24:e13550. doi: 10.1111/obr.13550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picchioni F, Goulao LF, Roberfroid D. The impact of COVID-19 on diet quality, food security and nutrition in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of the evidence. Clin Nutr. 2022;41:2955–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells JC, Sawaya AL, Wibaek R, et al. The double burden of malnutrition: aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet. 2020;395:75–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32472-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das JK, Salam RA, Thornburg KL, et al. Nutrition in adolescents: physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1393:21–33. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian S, Deaton A. The demand for food and calories. J Polit Econ. 1996;104:133–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reardon T, Timmer CP, Barrett CB, Berdegué J. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Am J Agric Econ. 2003;85:1140–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bleich S, Cutler D, Murray C, Adams A. Why is the developed world obese? Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:273–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reardon T, Timmer CP, Minten B. Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12332–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003160108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, et al. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4001–06. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313490111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolmarans P. Background paper on global trends in food production, intake and composition. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55:244–72. doi: 10.1159/000229005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. Food and commodity balances 2010–2020. Global, regional and country trends. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentham J, Singh GM, Danaei G, et al. Multi-dimensional characterisation of global food supply from, 1961–2013. Nat Food. 2020;1:70–75. doi: 10.1038/s43016-019-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C, et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013;381:670–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2414–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30:67–77.:e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winichagoon P. Thailand nutrition in transition: situation and challenges of maternal and child nutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22:6–15. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paes-Sousa R, Vaitsman J. The Zero Hunger and Brazil without Extreme Poverty programs: a step forward in Brazilian social protection policy. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:4351–60. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320141911.08812014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Núñez J, Pérez G. The escape from malnutrition of Chilean boys and girls: height-for-age Z scores in late XIX and XX centuries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10436. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alderman H, Bundy D. School feeding programs and development: are we framing the question correctly? World Bank Res Obs. 2012;27:204–21. [Google Scholar]

- 37.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) A century of trends in adult human height. eLife. 2016;5:e13410. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floud R, Fogel RW, Harris B, Hong SC. The changing body: health, nutrition, and human development in the western world since 1700. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speakman JR, de Jong JMA, Sinha S, et al. Total daily energy expenditure has declined over the past three decades due to declining basal expenditure, not reduced activity expenditure. Nat Metab. 2023;5:579–88. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00782-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popkin BM, Conde W, Hou N, Monteiro C. Is there a lag globally in overweight trends for children compared with adults? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1846–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Clarke A, Smith WCS. Diet behaviour among young people in transition to adulthood (18–25 year olds): a mixed method study. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2:909–28. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.931232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winpenny EM, van Sluijs EMF, White M, Klepp KI, Wold B, Lien N. Changes in diet through adolescence and early adulthood: longitudinal trajectories and association with key life transitions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:86. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0719-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev. 2012;13:659–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neufeld LM, Andrade EB, Ballonoff Suleiman A, et al. Food choice in transition: adolescent autonomy, agency, and the food environment. Lancet. 2022;399:185–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dollman J, Norton K, Norton L. Evidence for secular trends in children’s physical activity behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:892–97. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016675. discussion 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kramer MS, Moodie EEM, Dahhou M, Platt RW. Breastfeeding and infant size: evidence of reverse causality. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:978–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng M, D’Souza NJ, Atkins L, et al. Breastfeeding and the longitudinal changes of body mass index in childhood and adulthood: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2023;15:100152. doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neves PAR, Vaz JS, Maia FS, et al. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: analysis of 113 countries. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:619–30. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00163-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Czernichow S, Renuy A, Rives-Lange C, et al. Evolution of the prevalence of obesity in the adult population in France, 2013–2016: the Constances study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14152. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93432-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, León-Muñoz LM, Regidor E, Banegas J, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Trends in obesity and abdominal obesity in the older adult population of Spain (2000–2010) Obes Facts. 2013;6:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000348493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jansana A, Pistillo A, Raventós B, Nurn E, Freisling H, Duarte Salles T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of adult overweight and obesity in a large population-based cohort study in Catalonia, Spain. Obes Facts. 2023;16(suppl 1):133. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Gonzalez JM, Martin-Criado E. A reversal in the obesity epidemic? A quasi-cohort and gender-oriented analysis in Spain. Demogr Res. 2022;46:273–90. [Google Scholar]

- 54.WHO. Consideration of the evidence on childhood obesity for the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: report of the Ad hoc Working Group on Science and Evidence for Ending Childhood Obesity. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiggins S, Keats S, Han E, et al. The rising cost of a healthy diet: changing relative prices of foods in high-income and emerging economies. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why are some population interventions for diet and obesity more equitable and effective than others? The role of individual agency. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen NJ, østergaard JN, Bjerregaard LG, et al. A literature review of evidence for primary prevention of overweight and obesity in healthy weight children and adolescents: a report produced by a working group of the Danish Council on Health and Disease Prevention. Obes Rev. 2024;25:e13641. doi: 10.1111/obr.13641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharman L. Half of households unable to afford a healthy diet, finds study. 2018. Sept 5, [accessed Aug 18, 2023]. https://www.localgov.co.uk/Half-of-households-unable-to-afford-a-healthy-diet-finds-study/45949 .

- 59.Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Khan T, Wada R, Chaloupka FJ. Assessing the potential effectiveness of food and beverage taxes and subsidies for improving public health: a systematic review of prices, demand and body weight outcomes. Obes Rev. 2013;14:110–28. doi: 10.1111/obr.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Popkin BM, Ng SW. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: lessons to date and the future of taxation. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taillie LS, Busey E, Stoltze FM, Dillman Carpentier FR. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. 2019;77:787–816. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:643–60. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kern DM, Auchincloss AH, Stehr MF, et al. Neighborhood prices of healthier and unhealthier foods and associations with diet quality: evidence from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1394. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fraval S, Hammond J, Bogard JR, et al. Food access deficiencies in sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence and implications for agricultural interventions. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;3:104. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Food Security Information Network, Global Network Against Food Crises. Global report on food crises 2023. Rome: Food Security Information Network; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Laborde D, Herforth A, Headey D, de Pee S. COVID-19 pandemic leads to greater depth of unaffordability of healthy and nutrient-adequate diets in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Food. 2021;2:473–75. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baffes J, Mekonnen D. Falling food prices, yet much higher than pre-covid. 2023. Aug 16, [accessed Sept 22, 2023]. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/falling-food-prices-yet-much-higher-pre-covid .

- 68.Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, International Fund for Agricultural Development, UNICEF, UN World Food Programme, WHO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023: urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, International Fund for Agricultural Development, UNICEF, UN World Food Programme, WHO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022: repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pandey VL, Mahendra Dev S, Jayachandran U. Impact of agricultural interventions on the nutritional status in South Asia: a review. Food Policy. 2016;62:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grajeda R, Hassell T, Ashby-Mitchell K, Uauy R, Nilson E. Regional overview on the double burden of malnutrition and examples of program and policy responses: Latin America and the Caribbean. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;75:139–43. doi: 10.1159/000503674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen JFW, Verguet S, Giyose BB, Bundy D. Universal free school meals: the future of school meal programmes? Lancet. 2023;402:831–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bleich SN, Rimm EB, Brownell KDUS. Nutrition assistance, 2018—modifying SNAP to promote population health. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1205–07. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1613222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omidvar N, Babashahi M, Abdollahi Z, Al-Jawaldeh A. Enabling food environment in kindergartens and schools in Iran for promoting healthy diet: is it on the right track? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:e4114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tandon BN. Nutritional interventions through primary health care: impact of the ICDS projects in India. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67:77–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Age-standardised and age-specific results of this study, as well as the computer code and input data for the analyses, can be downloaded from https://www.ncdrisc.org. Computer code and input data are also available from the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10534960). Input data are provided where permitted by data governance and sharing arrangements; contact information is provided for other data sources.