Abstract

Self-renewing cells of the vertebrate heart have become a major subject of interest in the past decade. However, many researchers had a hard time to argue against the orthodox textbook view that defines the heart as a postmitotic organ. Once the scientific community agreed on the existence of self-renewing cells in the vertebrate heart, their origin was again put on trial when transdifferentiation, dedifferentiation, and reprogramming could no longer be excluded as potential sources of self-renewal in the adult organ. Additionally, the presence of self-renewing pluripotent cells in the peripheral blood challenges the concept of tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells. Leaving these unsolved problems aside, it seems very desirable to learn about the basic biology of this unique cell type. Thus, we shall here paint a picture of cardiovascular progenitor cells including the current knowledge about their origin, basic nature, and the molecular mechanisms guiding proliferation and differentiation into somatic cells of the heart.

Keywords: Stem cell, Cardiovascular progenitor cell, Self-renewal, Cell differentiation, Cardiogenesis, Transcriptional control, Cell plasticity.

1. Introduction

Following the identification of numerous self-renewing cells in vertebrate hearts during the past decade, the assumption emerged that the mammalian heart also has a limited, intrinsic, regenerative potential. Endogenous, self-renewing, and differentiating cells were only recently discovered to contribute to the maintenance, homeostasis, and proper function of the heart throughout the life of an organism. However, clinical approaches show that those cells fail to repair injuries sufficiently after acute myocardial infarction and cannot hinder chronic degeneration of the myocardium. In stark contrast to lower vertebrates, such as fish and newts that are able to respond to cardiac damage by generation of de novo cardiomyogenesis, mammals respond to injury of the heart with scar formation (Ausoni and Sartore, 2009). Interestingly, a continual, limited turnover of human heart cells has been demonstrated elegantly by C14-dating of postmortem heart cells (Bergmann et al., 2009). Most importantly, this study also showed a declining regenerative potential in elderly patients, which may be interpreted as a decrease in the number of self-renewing cells with increasing age.

These dividing heart cells shall be named here cardiovascular progenitor cells for several reasons explained in the next section on the definition of terms and have been identified in situ in the hearts of humans (Bearzi et al., 2009, 2007; Beltrami et al., 2001; Bergmann et al., 2009; Kajstura et al., 2010; Laugwitz et al., 2008; Messina et al., 2004; Smits et al., 2009), mice (Messina et al., 2004; Tallini et al., 2009; Tateishi et al., 2007), rats (Oyama et al., 2007), dogs (Linke et al., 2005), and pigs (Johnston et al., 2009). Cardiovascular progenitor cells have been characterized by the expression of stem cell antigen 1, SCA1 (Matsuura et al., 2004; Smits et al., 2009); Islet-1, ISL1 (Laugwitz et al., 2005; Moretti et al., 2006); the multidrug resistance protein, MDR1 (Oh et al., 2003); and the Stem Cell Factor receptor, cKIT (Bearzi et al., 2009, 2007; Beltrami et al., 2003). They were found mainly in the ventricular and atrial myocardium but also in the epicardial tissue (Limana et al., 2007), cardiospheres (Davis et al., 2009; Messina et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007), heart auricles (Gambini et al., 2010), and embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies (Kattman et al., 2006, 2011). In most publications, these cells have been uniformly termed cardiac stem cells or progenitor cells, but were also named mesoangioblasts (Galvez et al., 2008) and cardiac side population cells (Oyama et al., 2007).

The renewing cell populations were characterized in vitro by their potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells (Bearzi et al., 2007; Oyama et al., 2007; Smits et al., 2009; Srivastava and Ivey, 2006; Wu et al., 2008), and possibly also cardiac fibroblasts (Zeisberg and Kalluri, 2010). These data led to the hypothesis that these somatic cell types in the heart share a common progenitor heritage, possibly a kind of primordial cardiovascular stem cell (Garry and Olson, 2006; Moretti et al., 2006). In mice, such isolated, primary cell populations contributed to the regeneration of the diseased heart to variable extents when injected into the myocardium adjacent to infarcted areas (Bearzi et al., 2007; Beltrami et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2009; Martin-Puig et al., 2008). However, their functional contribution to the heart has not been unambiguously demonstrated so far.

The identification and characterization of cardiovascular progenitor cells has been described in numerous reviews because of the feasible therapeutical potential of these cells in regenerative medicine. Thus, only a few reviews can be mentioned here (Anversa et al., 2007b; Hansson et al., 2009; Kajstura et al., 2008; Laugwitz et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008), some of them dealing with the transcriptional regulation of the cell cycle (Goetz and Conlon, 2007) and cardiomyogenesis (Bruneau, 2002; Chien et al., 1993; Firulli and Thattaliyath, 2002; Laugwitz et al., 2008), others focusing on the various developmental stages a common progenitor has to run through before complete differentiation into a mature heart cell (Bruneau and Black, 2007; Garry and Olson, 2006; Martin-Puig et al., 2008; Musunuru et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2008).

The existence of tissue-specific self-renewing cells has been challenged by the identification of multipotent progenitor cells present in the peripheral human blood (Cesselli et al., 2009). Possibly, these cells are able to transmigrate through the vessel walls and populate the heart either constantly or after activation through paracrine mechanisms after injury. Likewise, induced reprogramming (Efe et al., 2011; Ieda et al., 2010), transdifferentiation (Takeuchi and Bruneau, 2009), and naturally occurring plasticity of somatic cells (Raff, 2003; Zipori, 2004a) open new questions about the origin and nature of cardiovascular progenitor cells.

Nonetheless, understanding the framework of molecular and cellular mechanisms guiding the instruction and limitation of maintenance, dormancy, self-renewal, and differentiation of cardiovascular progenitor cells in their natural microenvironment or niche is of fundamental biological interest and an indispensable prerequisite for future medical applications. On the way to reach this ultimate goal, numerous obstacles have to be overcome. First of all, there is still no consent about the molecular markers specifying somatic cardiac stem cells and whether they have a significant functional role in cardiovascular progenitor cells. Second, cells described so far differ in their morphology and developmental phenotypes. Third, we still know far too little about the stem cell niche of the heart, the transcriptional network regulating self-renewal of cardiovascular progenitor cells, and the developmental cues guiding differentiation into all cardiac cell types. Finally, but most importantly, we do not know the conditions for in vitro maintenance of isolated cardiovascular progenitor cells to keep them in an indefinite state of self-renewal in conjunction with the preservation of their differentiation potential. This last issue is of major interest and an indispensable prerequisite for studying and comparing molecular mechanisms of self-renewing cells of the heart (Moretti et al., 2007; Smits et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009).

Thus, most information obtained so far about the transcriptional regulation and the influence of growth factors, cytokines and small molecules on self-renewal, commitment, and differentiation of cardiovascular progenitor cells has been from genetic model organisms, such as Drosophila melanogaster, Xenopus laevis, Danio rerio, Mus musculum, and embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies from mouse and man. For the sake of clarity, we will not distinguish between mechanisms analyzed in human and mouse stem cells and tissues, first, in order not to complicate the subject and, second, because there is too little data to draw a clear picture of the differences between these species. Consequently, several assumptions had to be made to build this hypothetical model of molecular regulation of cardiomyogenesis in the heart. We presume that the core mechanisms of self-renewal and differentiation are evolutionarily conserved in vertebrates and comparable to those in insects. Further, we suppose that molecular mechanisms responsible for cardiac development during embryogenesis are comparable to those involved in cardiomyogenesis and homeostasis of the adult heart.

Based on these assumptions, we shall review and discuss data concerning the fundamental nature of cardiovascular progenitor cells, their origin within the heart, and how our knowledge about the underlying molecular mechanisms evolved. These insights will foster our understanding of embryonic heart development, homeostasis in the adult heart, also in the context of congenital and acquired heart diseases, and finally on the inevitable decay of the aging heart.

2. Definition of Terms

Since dividing cells residing in the adult heart were discovered not even a decade ago, the definition and use of terms in the literature is still inconsistent. First of all, it is not entirely clear what connotations go along with the use of the terms “cardiac” and “heart” in combination with “cells” in the literature. In most cases, muscle cells of the heart, cardiomyocytes, are meant, regardless of the assumption that the heart might be composed of one or two dozens of different somatic cell types. Among them, cardiomyocytes, interstitial cells or fibroblasts, telocytes or podocyte-like cells, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and all different cell types composing the complex cardiac conduction system can be defined. Going into further detail, one should keep in mind that the heart muscle is composed of different types of cardiomyocytes, such as atrial and ventricular ones. Similarly, cells forming the endocardium, heart valves, epicardium, and pericardium most likely also display different phenotypes. The same applies for the coronary blood vessels and the descending large vessels, where it is still hard to identify a clear border between arteries and veins on one side, and the core myocardium on the other side. Because of this plethora of cell types composing the heart, and the fact that all described self-renewing heart cells give rise to more than one somatic cell type, we will use here, as in the past, the term “cardiovascular” when speaking of cells located in the heart.

Second, there is still a Babylonian confusion concerning the terms “stem,” “stemness,” “progenitor,” and “precursor.” Concomitantly, the lack of knowledge about the differentiation potential of a cell further complicates this issue. To start with the easiest part, we suggest to prefer “progenitor” over “precursor” in regard to a cell placed within a series of cell divisions. A connotation of progenitor is to descend from something living, which fits best when talking about cells, whereas “precursor” is more often used in a chemical or technical sense. To decide whether a cell is a stem cell or a progenitor cell, we should first consider that the term “stem” implies the positioning at the base of a stem, a genealogical tree or a pedigree, giving rise to all descendants. Thus, we would assume this cell type to be totipotent or at least pluripotent. This would fit best to the zygote, the blastomeres, and perhaps to embryonic stem cells, but not to somatic or adult cells that inherit some, however, not all, properties of stemness. The latter ones include here the capability of a cell to self-renew, either indefinitely or for a limited period of time, and the potential to give rise to all types of somatic cells, including germ cells and somatic dividing cells. As self-renewing cells of an adult organ always stem from some predecessors classified in a certain lineage and are neither totipotent nor multipotent, we suggest not to use the terms “somatic stem cells” or “adult stem cells” any longer. Based on these considerations, we shall rather use here and in the future the term “cardiovascular progenitor cell” for a somatic cell in the heart that is capable of self-renewal and displays a certain degree of differentiation potential, being either multipotent or unipotent.

Two other terms that are often used to describe attributes of cardiovascular progenitor cells are “commitment” and “clonogenicity.” At a first glance, it seems simple and straight forward to argue that an organ-specific progenitor cell has to be committed to a certain lineage giving rise to at least some somatic cell types of the organ of origin, but not to those of other organs. Similarly, if progenitor cell are self-renewing they must be clonogenic, as they give rise to at least one identical daughter cell. However, since we see accumulating evidence for natural plasticity of cells and cannot exclude reprogramming of somatic cells as a potential source of progenitor or stem cell, we should not use “commitment” and “clonogenicity” as stringent attributes to define progenitor cells.

Concerning the heart as well as other organs, a future task will be to provide a more accurate definition of the progression of the differentiation process that characterizes the lineage commitment of cardiovascular progenitor cells with the ultimate acquisition of the adult phenotype. However, it remains an open question whether defined and stable cell lines showing a certain developmental stage between the primitive mesoderm and the adult heart can be isolated and characterized. Likewise, it is currently impossible to determine and classify cardiovascular progenitor cells isolated by different groups of scientists, according to their maturity, developmental potential, or dedication. In fact, the existence of distinguishable subpopulations of cardiovascular progenitor cells is still uncertain. Most populations are identical concerning their phenotype, mostly because of their smallness. However, the use of different marker genes to isolate and characterize different cell types by fluorescence-activated cell sorting does not solve this problem. First, no functional relevance of these markers has been described so far, and second, different expression levels of sets of genes, considered as typical for a certain cell type, do not guarantee a different phenotype. This we shall see later when discussing fluctuations of gene expression in cells with a high differentiation potential. Vice versa, diverse expression levels in differentially isolated cardiovascular progenitor cells cannot be taken as evidence for their discrimination and different function. It seems that as long as a certain degree of “stemness” can be attributed to a cell, the expression of responsible genes and functional consequences are inherently linked to some uncertainness. To address this problem properly, a first step would be to culture all differently isolated cardiovascular progenitor cells in an identical and parallel way. Characterization of these cell lines regarding their self-renewal, differentiation potential, and gene expression pattern would help to answer the question, about the existence of only one or several different types of cardiovascular progenitor cells. Consequently, in this review, we shall describe all primary cell populations published so far but will not distinguish between these cell population when discussing the potential and proven influence of transcription factor networks and paracrine signaling on their self-renewal and differentiation.

3. Origin of Cardiovascular Progenitor Cells

3.1. Evolutionary aspects

Inevitably, the heart is considered as the most essential and central organ of the human body as it is absolutely necessary for existence of all higher organisms. However, at the beginning of life, there was no need for heart-like structures and primitive multicellular organisms still do not use circulatory systems. An efficient pump became necessary for the first time when distribution of oxygen became an inevitable prerequisite for the survival of triploblastic organisms (Romer and Parsons, 1977). All along the evolutionary pathways from earliest sponges to humans, the major molecular and cellular mechanisms of heart development only slightly changed (Olson, 2006). The ancestral genes coding for transcription factors that form a network regulating cardiomyogenesis expanded through duplication, refined through modification and subsequential selection. This network was mainly comprised of NKX, MEF, GATA, TBX, and HAND transcription factors. The conserved principal coordination of cardiomyogenesis over millions of years presents the importance of the idea of the heart, even though today’s perfectly working organ only vaguely resembles the ancient contracting tubes of primitive sponges (Bishopric, 2005). Noteworthy, not all metazoans possess a heart. One group of miniaturized animals in the taxon Panarthropoda, the Tardigrades, has lost the heart during evolution and reduction of body size (Schmidt-Rhaesa, 2001).

In evolution, the earliest hearts served as primitive organs in late diploblastic or early triploblastic organisms (Martynova, 1995). A gradually increasing body size of these organisms led to the development of a body cavity, the coelom, or a fluid filled vessel-like structure. Improved nutrient and gas exchange, as well as centralized sexual reproduction allow evolutionary advantage for the newly arisen coelomata (Boero et al., 1998). The gradual specification of this “gastroderm” in diploblasts results in the appearance of a third germ layer, a prototype of mesoderm. Diploblastic jellyfish development was shown to involve the formation of the so-called entocodon, an autonomous tissue layer between the distal ectodermal and the endodermal tissue (Boero et al., 1998). In medusa, this layer is not only separated from the others by an extracellular matrix but also shows expression of muscle-specific forms of Troponin and Myosin heavy chain, distinctive mesoderm-patterning genes, such as Twist and Brachyury, as well as the muscle regulatory proteins MEF2 and SNAIL (Spring et al., 2002). As another prerequisite for a more structured tissue, collagen came up and served as a major component of extracellular matrix of the separating germ layers (Schroder et al., 2000). Interestingly, a protein homologue of cardiac Myotrophin, a factor that stimulates myocyte growth and triggers myocardial hypertrophy in mammalians, was shown to stimulate collagen synthesis in sponges. These early autocrine and paracrine signaling pathways together with the appearance of matrix molecules and the characteristic mesodermal gene expression in primitive diploblastic organisms can be considered as the earliest predisposition of a third germ layer, subsequently allowing myogenesis and muscle-like development (Chen and Fishman, 2000).

The first primitive myocytes appeared before the divergence of Radiata and Bilateria 555 million years ago (Oota and Saitou, 1999). Initially, organized muscle-like cells for early cardiac-like purpose may then have evolved from local dorsal, in insects, or ventral, in vertebrates, excrescences of the primitive foregut (Martynova, 2004). The function of these simple, but already electrically and functionally coupled, contracting structures was the formation of a pumping system for body fluids through the coelom of bilaterian organisms (Moorman and Christoffels, 2003; Simoes-Costa et al., 2005). Later, muscular tubes evolved, squeezing rhythmically and moving blood-like liquid through peristaltic contraction through the body. Invertebrates, such as modern earthworms, still possess these evolutional relicts, some of them having seven pumping tracts regulating their straightforward body fluid circulation system (Avery and Thomas, 1997). Further, most insects still inherit the so-called dorsal vessel which fulfill the function of a primitive heart (Baccetti and Bigliardi, 1969). In D. melanogaster, a pulsating blood vessel already containing valves is formed from heart precursor cells in response to Decapentaplegic, DPP, a Bone Morphogenetic Protein, BMP, homologue, and Wingless, WG, a WNT homologue. Here, the NKX2.5 homologue Tinman is required for cardiac specification (Chen and Schwartz, 1995), resulting in two major cell types: cardioblasts of the contractile tube and flanking pericardial cells (Bodmer, 1995). Additionally, Pannier, a GATA4 homologue, T-box transcription factors, and Hand genes play fundamental roles in heart development of the fruit fly (Olson, 2006). Through modification and specification of this conserved set of genes, the mammalian homologue proteins namely, NKX2.5, TBX5, TBX20, HAND2, and GATA4, nowadays function in a similar manner as the ancient regulators of heart development. Thus, autoregulation of the key transcription factors has induced and stabilized definitive cardiac identity throughout evolution (Bruneau, 2002; Buckingham et al., 2005; Srivastava and Olson, 2000).

As a lineage of the primordial invertebrates slowly morphed through primitive chordates, it became the first fishes about 500 million years ago (Long, 1996). In addition to the extensive modification of the body structure, also the pumping and vessel system developed more complex characteristics in fish. Primary muscle cells diversified into skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle cells, ultimately resulting in the formation of atrial, ventricular, and conductive myocytes. Accordingly, a quite primitive organ considered as the heart aroused in fish 500 million years ago (Bishopric, 2005; Moorman and Christoffels, 2003; Romer, 1967; Simoes-Costa et al., 2005). The previously tube-like structure developed into a two-chambered, synchronously pumping heart, composed of an atrium and a ventricle, separated by a rudimentary atrioventricular valve. In this self-contained single circuit circulation in fish, the blood is pumped through the atrium and the ventricle and exits the organ through the conus arteriosus. It receives oxygen at the gills and is then pumped to the organs of the fish for gas, nutrients, and waste exchange before returning back to the atrium.

Together with further development and specialization of primitive hearts, different classes of cardiac and skeletal muscle gene isoforms evolved such as cardiac Actins and Troponin C (Gillis and Tibbits, 2002). The underlying mechanisms such as gene duplication and subsequent change of DNA sequence allow functional specialization not only on the cellular level but in a greater context (Olson, 2006). Novel regulatory transcription factor networks tolerate greater plasticity and adaptability to more specified demands and structural components.

Alongside, the amphibians came up evolving a three-chambered heart, comprising two atria and one ventricle (Simoes-Costa et al., 2005). The atria evolved through physical division of the original atrium or through duplication of an incoming vessel. The formation of the right and the left atrium permits somewhat separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood circulation. In reptiles, the heart became almost four-chambered (Wang et al., 2002). An incomplete ventricular division allows double circuit circulation and directed flow of mostly separated oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, necessary for survival in the terrestrial environment.

With the evolution of birds and mammals, 120 million years ago, the division between the left and the right ventricles was completed (Rishniw and Carmel, 1999). In this regard, the boundary between high expression of the T-box transcription factor 5, TBX5, in the left ventricle and low expression in the right ventricle of mammalian hearts marks the line where the septum forms during embryogenesis and divides the ventricles into two parts (Bruneau et al., 1999). The created double circuit circulation then includes total separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood as well as separation of the pulmonary and the systemic circulation. Alongside, cardiac shape and functionality developed and led to the formation of chambers, valves, and the conduction system. The latter one was only possible through the evolutionary invention of Connexins, intracellular channel forming proteins, transmitting chemical, and electrical signals (Becker et al., 1998). Whereas only one major type of Connexins can be found in primitive chordata, 20 separate forms developed in mammalia, enabling greater plasticity of complex heart formation. Accelerated communication through these channels allowed rapid, synchronous contraction, and has finally found a climax in the formation of the today’s cardiac conduction system (Myers and Fishman, 2003).

Hand in hand with the first steps of cell differentiation and tremendous changes in heart development, the question of integrity, maintenance, and repair strategies arose. In this context, a distinct, ideally well-controlled number of multipotent, somatic stem cells came up to fulfill all these requirements (Bosch, 2009). Stem cells were shown to keep responsibility of cellular homeostasis, replacing dysfunctional somatic cells, and generating new ones through asymmetric cell division. As the stem cell pool in adult organisms has to comprise a constant cell number, molecular pathways regulating maintenance and differentiation are required for their nonpathological function.

Stem cells were supposed to be at least 800 million years old; they first evolved in the oldest extant metazoan, the sponges (Bosch, 2009). The chemokine network of porifera provides earliest markers for stem cells, mesenchymal stem cell-like proteins, and stem cell maintenance factors such as Noggin and Glia Maturation Factor (Muller et al., 2004b). Likewise, homologues of these genes can still be found in the human genome (Muller et al., 2004a). More primitive organisms, such as molluscs, arthropods, and amphibians, use the mentioned progenitor cell pool to easily reconstruct parts of their heart or other organs via self-renewal or replacement (Martynova, 2004). In contrast to lower vertebrates, mammals respond to injury of the heart with scar formation (Ausoni and Sartore, 2009). As it was recently shown, also humans posses a limited ability of heart renewal; however, their regenerative potential is diminished in comparison to many other lower vertebrates (Beltrami et al., 2003). It is hypothesized that, in long-lived organisms, adult stem cells may serve as a source of restoration of minor injuries, prevent degeneration, and slow down aging during long-time organ function. However, possibly due to avoidance of neoplasia and tumor growth, the mammalian heart is not capable of complete regeneration after acute myocardial injury. This evolutionary adaptation excludes proper replacement of large-scale damaged tissue and makes cardiovascular diseases one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the western word.

3.2. Origin of cardiovascular progenitor cells during embryogenesis

In vertebrates, the cardiovascular system and its central apparatus, the heart, represent the first organ system to become functional long before other parts in the early embryo are discernable. All subsequent events in life depend on the heart’s continuous contractility and ability to pump oxygen and nutrients through the body of higher organisms. During heart development, initial cardiac progenitor cell populations driven by underlying molecular mechanisms guide heart development, from the primitive contractile cardiac tube to gradually more specific structures, including chambers, valves, and the conduction system. In birds and mammals, this finally leads to the formation of a four-chambered heart, such as it can be found in humans. Due to the complex nature of the heart, developmental abnormalities result in congenital heart disease, the most common human birth defect, and may lead to medical consequences such as arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, hypertrophies, or heart failure.

During embryonic development, the earliest cells showing cardiac fate were confirmed to have their origin in mesodermal tissue derived from the primitive streak that forms during gastrulation (Rawles, 1943; Robb and Tam, 2004). Recently, the T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin was described to be an initial and essential factor for epithelial to mesenchymal transition, marking the earliest formation of cardiac mesoderm through directly activating the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH), transcription factor Mesoderm Posterior Homolog 1 (MESP1) (Costello et al., 2011; Saga et al., 2000). Accurate temporal and local control of transcription factors such as T-box transcription factor Brachyury and MESP1 is required for successful activation of downstream cardiac signaling and initiation of heart development (Solloway and Harvey, 2003). In one of the evolutionary oldest cardiac-like structure, the dorsal vessel of D. melanogaster, distinct gene expression patterns of developmental genes guide heart development (Harvey, 1996). However, the more complex the contractile organ gets, the more intricate pathways are required for its development. In mammalian cardiogenesis, a much greater diversity is needed to ensure formation and function of the multifaceted protein network in cells adopting cardiac fate (Fishman and Olson, 1997).

Among the most significant pathways, the canonical WNT/βCatenin signaling is absolutely required for embryonic mesoderm formation and thus lays the foundations for heart development during the third week of human embryogenesis (Eisenberg and Eisenberg, 1999). Remarkably, from that time point on, distinct canonical WNTs prohibit further heart formation and their inhibition was shown to induce heart activating factors such as the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Marvin et al., 2001; Schneider and Mercola, 2001). In contrast, other noncanonical WNTs act through calcium regulation and phosphorylation of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinases, JNK, resulting in activation of cardiac progenitor cells during embryogenesis (Pandur et al., 2002). Further key molecules inducing heart development are the members of the Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGFβ) super-family, including Nodal, Activin, BMP, and Growth Differentiation Factor (GDF; Olson, 2006). These factors act through SMA and Mothers-Against-Dekapentaplegic homologs (SMAD) signaling molecules and were shown to be responsible for early mesendodermal induction. BMP antagonists chordin and noggin prevent downstream signaling of the stated pathways and hence the formation of cardiac mesoderm in inappropriate areas (Schlange et al., 2000). Further, Cdx genes, a family of very early expressed transcription factors regulating the Hox genes, together with retinoic acid signaling were shown to restrict the formation of anterior mesoderm and suppress cardiac development by implementing posterior identity to developing cells (Lengerke et al., 2011).

After and during initial gene expression patterning, specialization, and definition of cardiac progenitor cells, they migrate from the ventral splanchnic or visceral region of the mesoderm to the anterior lateral region of the early embryo to form the cardiac crescent (Tam et al., 1997). Subsequently to these initial molecular and physiological steps essential for the onset of early cardiomyogenesis, inductive endogenous signals, and those of the surrounding tissue induce mesodermal progenitor cell specification to the cardiac lineage (Tam et al., 1997). Utilized signaling for cardiac commitment includes Fibroblast Growth Factor, FGF, BMP, WNT, and Hedge-hog-induced signal transduction. Early cardiac and noncardiac patterning, regional activation, and inhibition of differentiation and signal response require a few irreplaceable key players. Among those, the cardiac transcription factors NKX2.5, TBX5, TBX20 and GATA4 are necessary and guiding for cardiomyogenesis (Gelb, 2004). Upstream of this network, FGF and BMP signaling were shown to stimulate the expression of the homeodomain transcription factor NKX2.5 and, as mentioned previously, activate a number of downstream cardiac transcription factors such as MEF2 and GATA4, finally resulting in the onset of muscle-specific gene expression (Tanaka et al., 2001).

The earliest specified precursor cells commit henceforward irreversibly to the cardiac lineage and begin to differentiate. These primed precursor cells are in a premature state still within a progenitor cell pool named the “first heart field” and can be characterized through the expression of TBX5, HAND1, and the first wave of NKX2.5 (Lengerke et al., 2011). They have cardiac developmental potential when explanted and cultured in vitro (Jacobson and Sater, 1988). After cells of the first heart field eventually build up the primordium, the latter one subsequently fuse to a linear heart tube. The inner layer, the endocardium, is composed of endothelial cells, and the outer layer, the myocardium, of myocardial cells (Buckingham et al., 2005). At this point, the heartbeat is initiated, possibly as a direct result of induction of cTnT and Tropomyosin-4 expression (Nishii et al., 2008).

After elongation of the tubular heart structure, a second population of proliferating progenitors in the pharyngeal mesoderm, lying anterior of the cardiac crescent, is recruited to the poles of the heart tube (Christoffels et al., 2000). These cells of the second heart field are characterized through expression of Insulin gene enhancer protein 1, Islet-1 or ISL1, FGF10, bHLH, transcription factor HAND2, and a second wave of NKX2.5 during embryonic development. Using dyes, retroviral lineage tagging, or LacZ transgenes, the migration of these cells into the cranial part of the previously formed heart tube was revealed. They contribute primary to cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, constructing the outflow tract and the right ventricular myocardium (Moses et al., 2001). According to in vitro analysis, signals from the already existing outflow tract myocardium are sufficient to recruit cells from this second heart field to a myocardial fate (Mjaatvedt et al., 2001), and BMP antagonist Noggin was shown to inhibit the effect (Waldo et al., 2001).

During cardiac looping, where the linear heart tube folds ventrally, the migrating cells of the second heart field present a reserve pool of progenitors before contributing to the developing heart. Along the linear heart tube, recruited cells display diverse molecular behavior and gene expression patterns according to their positions in the looping heart. Asymmetric specification and remodeling of the folded heart tube require especially the embryonic left–right axis accompanied by sided expression of Pituitary Homeobox 2 transcription factor (PITX2), HAND1 and 2, and XIN, an Actin binding protein, among several other factors (Franco and Campione, 2003; Grosskurth et al., 2008; Harvey, 1998; McFadden et al., 2005). Together with the invasion of cells of the second heart field, progenitor cells from a nearby, transient, primitive organ-like structure, called the proepicardium, migrate toward the looping heart. These progenitors give rise to smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, and cardiac fibroblasts, finally forming the epicardium, the outer layer of the heart tissue, and contributing to the coronary vasculature (Limana et al., 2011). Regulating signals between the endo-, myo-, and epicardium are essential for correct growth and development of cardiac chambers later on. During the process of cardiac looping, the myocardium noticeably expands through invading cells of the second heart field and the heart tube bulges at its outer curvature. Anterior and posterior, as well as dorsal and ventral patterning is required for the primitive precursor structures of the later forming cardiac chambers (Christoffels et al., 2000).

Further specification of different heart tissues requires complete differentiation of cardiovascular progenitor cells and an augmented expression of cardiac-specific proteins such as actins, troponins, tropomyosins, and connexin channel proteins. Extensive remodeling of the internal structures of the heart includes septation and building of valves, guaranteeing the separation, and concurrent connection of the heart chambers. Definitive, coordinated myogenic specialization of restricted cells enables functional, contractile chamber formation.

During the ongoing formation and patterning of the heart, retrograde in vivo tracing of participating cells reveals that progenitors of the first heart field later contribute predominantly to the left ventricle in the adult heart. On the contrary, cells of the second heart field give rise to the outflow tract, the right ventricle, and to the right and left arterial chambers at the venous pole. The T-box transcription factor family plays a key role in establishment of chamber and nonchamber myocardium. TBX5 together with NKX2.5 promotes expression of chamber-specific genes, whereas TBX2 acts antagonistically and inhibits chamber formation (Christoffels et al., 2004). The remaining primary, nonchamber myocardium adopts another distinct fate, partly giving rise to the proximal conduction system, the atrioventricular node and the bundle of His, inflow and outflow vessel myocardium, and fibrotic tissue of the atrioventricular junction (Harvey et al., 2009). In addition to both heart fields and the contributions from the cranial neural crest to the heart (Scholl and Kirby, 2009), recent studies suggest the existence of a proepicardium-derived cardiac progenitor cell population (Zhou et al., 2008a). Cells of this distinct pool of progenitors expressing the WT1 genes separate early from the rest of the developing heart and later form the epicardial layer of the heart and the coronary blood vessels (Perez-Pomares et al., 2002).

Wide-ranging adjustment of the pumping structure, finally leading to cardiac valve formation, complete septation, separation of the oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the heart, occurrence of the coronary vasculature, the conduction system, and the epicardium, grants the heart its final form. Importantly, cardiogenesis requires a non-negligible amount of plasticity. This is supported by the fact that boundaries between distinct tissues and their flanking regions are not clonally restricted, but dependent on progressively changing signaling gradients.

For now, just the top of the iceberg about the fundamental mechanisms of cardiogenesis during embryonic development has been explored. The intricate dilemma that insights into the generation of life go mostly hand in hand with its destruction is still challenging. Anyway, the understanding about these early processes must be internalized to acquire understanding of similar mechanisms guiding cardiogenesis in cardiovascular progenitor cells in the adult heart. Piece by piece, in single steps, the molecular puzzle of the heart yet has to be solved to give a general idea about our innermost organ.

3.3. Cardiovascular progenitor cells in the adult organism

For many decades, cardiac biology was regarded as a very static field of research as the heart was considered a postmitotic organ without any regenerative potential. The changing came with the discovery of a subpopulation of small, immature, and proliferating myocardial cells in the adult heart. Before that, myocytes were presumed to exist from early embryonic mesodermal development onward until the very old age of men. Although other organs such as bone marrow, liver, skin, brain, skeletal muscle, and pancreas harbor-specific populations of regenerative, proliferating cells (Passier and Mummery, 2003), putative stem cells of the heart remained undetectable. Accordingly, the organ was thought to be composed out of terminally differentiated myocytes without any reproductive potential (Nadal-Ginard et al., 2003). As it was assumed that the actual number of cardiomyocytes in the mammalian heart hits the maximum right after birth and progressively diminishes with age, the only compensatory mechanism after injury of the heart was considered to be hypertrophy of the remaining cells.

The phenomenon that after heart injury the affected organ does not show great ability to self-repair and reconstruct seemed to assure the initial idea of the heart as a postmitotic organ. However, earliest evidence for postnatal cardiac regeneration came from the detection of cycling cells in the fully developed mammalian heart right after myocardial infarction (Anversa and Nadal-Ginard, 2002; Leri et al., 2005). The stated study shows an increased number of immature, mitotic cardiomyocytes in the infracted border zone of the heart. Further, incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine during DNA replication, expression of Ki67 and phosphohistone-H3, and activation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) has been evidential for karyo- and cytokinesis in adult myocytes (Bergmann et al., 2009; Kajstura et al., 2010; Leri et al., 2005). Unfortunately, the outcome of these initial experiments was rather misapprehended as cardiomyocytes were proposed to reenter the cell cycle after terminal differentiation (Anversa and Kajstura, 1998).

Anyway, the search for the concrete source of cycling cells led to the identification of a subpopulation of immature cells in the adult mammalian heart that was able to divide and give rise to new cells of the cardiac lineage (Beltrami et al., 2003). Anversa and colleagues isolated and characterized these small myocytes, according to their expression of the stem cell growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, cKIT. The isolated cells were considered as bona fide cardiac stem cells that were confirmed to show self-renewing capacity, were clonogenic, and multipotent; moreover, they could differentiate into myocytes, smooth muscle cells, or endothelial cells (Beltrami et al., 2003). In vivo, subsequently to commitment to the myocytes lineage, these stem cells give rise to progenitor cells that divide once or twice before they finally develop into mature, terminally differentiated myocytes (Nadal-Ginard et al., 2003; Torella et al., 2005). The finding of a stem cell source in the adult heart properly explained the previously misinterpreted discovery of cycling cells in the alleged postmitotic organ.

Another source of progenitor cells might come from the epicardium. Thymosin β4 induces the synthesis of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 (Al-Nedawi et al., 2004) in endothelial cells and has been demonstrated to provide endogenous stem cells from a pool within the epicardium (Smart et al., 2011). After myocardial infarction and intraperitoneal Thymosin β4 administration in mice, these stem cells reactivate the embryonic epicardial gene Wilm’s tumor 1 (Wt1), begin to express ISL1 and NKX2.5, migrate to the infarcted area, and transdifferentiate to functional cardiomyocytes.

The plasticity of pericytes, differentiating into vascular smooth muscle cells (Nehls and Drenckhahn, 1993; Nehls et al., 1992), other mesenchymal cells types, including fibroblasts, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes (Collett and Canfield, 2005), was used to argue, that pericytes may present a source of stem cells in the heart with a niche located along the cardiac microvasculature (Dore-Duffy, 2008), similarly to their function as stem cells in the brain (Bonkowski et al., 2011). Likewise, cardiomyocytes that induce endothelial cells to transdifferentiate into cardiac muscle cells (Condorelli et al., 2001) as well as isolated mesoangioblasts were suggested to contribute to myocardial regeneration (Galvez et al., 2008; Messina et al., 2004). However, it is unclear whether these types of cellular plasticity should be regarded as transdifferentiation between different somatic cell types or a common mesenchymal stem cell. Although pericytes and mesoangioblasts may be of pathophysiological importance or even contribute to tissue regeneration and homeostasis on the adult heart, it is important to remember that the lack of definitive markers do not allow reliable fate mapping of these cells in vivo and in vitro. Hence, conducted experiments are generally confounded by the uncertain origin and identity of pericyte cultures.

These initial, outstanding findings were supported by later studies and numerous independent descriptions of populations of cardiac stem and progenitor cells and their isolation from different mammalian species, including mouse, rat, pig, dog, and human (Laugwitz et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2004; Matsuura et al., 2004; Messina et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2003; Pfister et al., 2005; Tomita et al., 2005). The obtained stem and progenitor cells are proposed to offer the heart a basis for homeostasis, plasticity, and regenerative potential during age-dependent or injury-induced degeneration of cardiac cells. Apart from hypertrophy, the heart was now demonstrated to inherit hyperplasic resource and competence.

However, there still is much discrepancy between and among the various cardiac stem and progenitor cell populations (Garry and Olson, 2006). The diverse cell types were identified with the help of completely different, independent surface markers such as SCA1, ATP-binding cassette transporter, ABCG2, or ISL1 and display 1–2% of total heart cells (Laugwitz et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2003). Phenotypical and methodical discrepancies between all collections of immature myocytes remain, possibly resulting in the unequal differentiation potential and expression profile of characterized cells. The lineage relation of the isolated subpopulations is still unclear, and the definition of a cardiac stem or progenitor state is ambiguous.

In regard to the fact that many organs only harbor one or two different types of progenitor cells, it is quite doubtful that the heart depends on three or more dissimilar groups of progenitors (Bollini et al., 2011). However, due to the lack of knowledge, it was also suggested that all or some of the described cell populations may present sequential or alternative differentiation stages of only one cell type (Ellison et al., 2007). As existence and the molecular characteristics of quiescent or cycling, undifferentiated or already committed stem, and progenitor cells could not yet be adequately defined, the question remains to be answered.

3.4. Marker of cardiovascular progenitor cells

The originally described and most promising population of cardiac stem cells was isolated according to the expression of cKIT and absence of the expression of Lin genes, a set of eight blood cell markers. So far, the isolated cell type represents the only one to fulfill the requirement of a bona fide stem cell, being self-renewing, clonogenic, and multipotent, giving rise to myocytes, smooth muscle, and vascular cells (Beltrami et al., 2003). When cultured in suspension, the cells were able to form so-called cardiospheres, similar to pseudo-embryoid bodies. Outgrowing cells from these aggregates express marker of myocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells (Torella et al., 2005). Moreover, using chemically or genetically tagged cKIT + cells for injection into the border zone of the heart after experimentally inducing myocardial infarction, the labeled cells gave rise to functional myocytes and vascular structures in vivo, hence, partly replacing the infracted zone. Especially, the expression of Connexin 43 and N-cadherin demonstrates electrical and mechanical coupling to the surrounding tissue (Beltrami et al., 2003).

In human, cKIT+ cardiac cells were identified (Quaini et al., 2002; Urbanek et al., 2003) and isolated from adult patients (Smith et al., 2007). These cells were shown to be negative for hematopoietic and endothelial markers but did express the MDR1, which is a glycoprotein of the same family of membrane transporters as SCA1, and ABCG2 (Anversa and Nadal-Ginard, 2002). This fact mainly supports the theory that cKIT+ cardiovascular progenitor cells represent a more original, immature cell population among the various isolated progenitor cell types, with the potential to generate side population cells and SCA1+ cells. Human cKIT+ cells were shown to be able to give rise to cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and ventricular smooth muscle cells, indicating their capacity for cardiac regeneration (Bearzi et al., 2007).

Another population of cardiac progenitor cells was isolated from the murine adult heart based on the expression of SCA1+ (Oh et al., 2003). The origin and the molecular identity of SCA1+ cells remain unclear, as distinct groups reported different amount of the expression of marker proteins such as cKIT, TIE2, ANG1, CD31, CD34, or CD45 (Matsuura et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2003). The inconsistent expression profiles of SCA1 cells may correspond to isolation artifacts or dissimilar sources and origins of the gained cells. SCA1+ cells only start to express cardiac transcription factors NKX2.5 and GATA4, structural proteins cTNT, cActin, αMHC, and the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1, FLT1, upon treatment with oxytocin (Matsuura et al., 2004) or the demethylating agent 5-azacytidine (Oh et al., 2003). However, in further guided development, they formed sarcomeric structures and spontaneously beating clusters. After ischemic reperfusion, SCA+ cells that were injected intravenously into the patient’s abdomen target the injured myocardium through differentiation into cardiomyocytes (Oh et al., 2003). Anyway, the identity of SCA1+ cells as cardiac stem cells and their therapeutic potential have been questioned because the marker gene is not decisive on human cells.

Cells of the so-called side population within the SCA1+ fraction represent another population of cardiac progenitor cells (Martin et al., 2004). They are marked by the expression of ABCG2, that enables the cells to exclude Hoechst and rhodamine dyes (Oh et al., 2003). Side population cells were shown to exist from early embryonic heart development on and persist into the adulthood in various organs such as muscle, liver brain, lung, skin, and finally heart (Montanaro et al., 2003). These cells show stem cell-like properties but prove ability to differentiate into cardiomyocyte lineages only upon treatment with oxytocin or trichostantin A, a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor (Oyama et al., 2007). When injected into the ischemic heart, side population cells differentiated to endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes (Oyama et al., 2007).

Recent work identified ISL1 expressing cells as cardiovascular progenitor cells in the human adult heart (Laugwitz et al., 2005). They were shown to be remnants from the cardiac primordia, the anterior pharynx, and subsequently the second heart field (Cai et al., 2003). In adult hearts, ISL1+ cells can be found in the outflow tract, the atria, and the right ventricle. They have been characterized as cardiac stem cells, implying the capability to self-renew and expand or differentiate to smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and endothelial cells (Bu et al., 2009). Approving the theory of ISL+ cells exclusively giving rise to myocytes of the formerly second heart field, no contribution of the subtype to the left ventricle was found. Secluded ISL+ cells from newborn rodents and humans showed potential to give rise to cardiac myocytes both in vivo and in vitro. Electromechanical coupling of in vitro differentiated ISL1+ cells into functional signaling networks indicates the possibility of treatment of conductive system diseases. However, the number of isolated stem cells decreases dramatically during the first weeks after the birth of mammals (Laugwitz et al., 2005), and moreover, in adult humans, no ISL1+ cells could be identified so far.

The epicardium was lately discovered as another potential source of fetal and adult cardiac stem cells (Lepilina et al., 2006). The outermost layer of the heart was shown to harbor multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells expressing the early epicardial genes Wt1 and Tbx18 during embryonic development and in the injured heart of adult organisms. The according cells were hypothesized to undergo epithelial mesenchymal transition, before forming so-called epicardium-derived mesenchymal cells and finally giving rise to multiple cardiac lineages such as cardiac fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardiomyocytes (Limana et al., 2011). The named properties are of particular importance during embryonic cardiogenesis and formation of the coronary vasculature but also in adult heart regeneration. After coronary artery occlusion, restoration of embryonic epicardial genes and developmental programs has been demonstrated to be essential for tissue regeneration (Urbanek et al., 2005). Moreover, in vitro culture of epicardial derived cells allows differentiation into smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and endothelial cells (Wu et al., 2006a). However, similar to ISL1+ cells, stem cells of the epicardium are mainly abundant during fetal development and merely disappeared in the adult heart (Limana et al., 2007).

Apart from problematic determination of their lineage relation, also the origin of cardiac stem cells yet has to be revealed. Either intrinsic cardiac cells exist in the adult organism since fetal life or cells of extracardiac origin have colonized the myocardium in postnatal life through the circulatory system. The small number of ISL1+ progenitors in the postnatal mammalian heart indicates the existence of remnant cardiac stem cells from embryonic development onward. Moreover, also cKIT+ cells and side population cells have been identified in embryonic and fetal development (Martin et al., 2004; Messina et al., 2004). On the other side, sex-mismatched cardiac and bone marrow transplants (Bayes-Genis et al., 2004; Quaini et al., 2002; Thiele et al., 2004) suggest an extracardiac source of recruited progenitors reconstituting the heart because cells with genetic markers of the donor and recipient, respectively, mix in the transplanted heart. If the bone marrow indeed harbors a source of cardiac stem cells in the adult organism, these cells would present a hitherto unidentified subpopulation of progenitors.

However, the in vitro and in vivo differentiation potential, the phenotype, the molecular identity, and the expression of defined marker genes of these immature cells vary among subpopulations (Di Nardo et al., 2010). Precardiac and cardiac transcription factors such as MESP1, TBX2, and NKX2.5 were shown to be unequally expressed. Further, numerous marker proteins such as SCA1, cKIT, MDR1, NKX2.5, and GATA4 are also abundant in other tissues and organs (Di Nardo et al., 2010). Hence, more definitive markers of the various cell types still need to be termed. Conflicting views of different functional characteristics have to be further investigated, integrated, and united. Especially for clinical reasons, homogeneous, fully characterized cardiovascular progenitor cells will be necessary to avoid decontamination by hyperplastic or tumorigenic cells.

3.5. Cardiac stem cell niche

Stem cells and progenitor cells are supposed to reside in habitats called niches. We use “niche” here as a collective term including connotations such as microenvironmental influences, paracrine and autocrine influences, and cellular contact, as well as the physical parameters influencing cells. They remain there in an undifferentiated and quasi-dormant state until external signals stimulate their commitment and differentiation into specific somatic cell types required for repair and maintenance of the according organ. Consequently, the myocardium possesses interstitial structures with the architectural organization of specific stem cell niches (Urbanek et al., 2006) particularly located in the atria and in a subepicardial region of the ventricles (Gherghiceanu and Popescu, 2010; Kuhn and Wu, 2010; Popescu et al., 2009).

Embryonic stem cells were shown to support themselves to maintain their self-renewing gene expression pattern in the presence of a minimal cocktail of growth factors just by cell–cell contact. In this case, the niche-like environment is composed of embryonic stem cell-derived Fibroblasts and the embryonic stem cells themselves that keep their status by a complex interplay between the Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 (IGF2), basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF), (Bendall et al., 2007), and Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) signaling (Niwa et al., 2009). In cardiospheres, as suggested by Anversa et al. (2007a), also niche-like environmental structures were identified (Li et al., 2010). Many of these niche cells express surface receptors such as N-cadherin, or β4α1 Integrins found on fibroblasts (Moore and Lemischka, 2006) in the interstitial space in the heart (Oyama et al., 2007). As the expression of Brachyury in primitive mesoderm is sufficient to establish the embryonic mesodermal stem cell state (Martin and Kimelman, 2010), it was argued here that these cells build up their own niche by supporting each other, without the need for a cellular compartment of different cell types.

In the heart, so far no specific stem cell niche comprising diverse types of supporting cells has been described. However, several cell populations residing in various locations in the heart were suggested to have stem cell potential. Recently, the epicardial stem cell niche has been proposed to contain cardiomyocyte precursors, potentially nursed by telocytes (Gherghiceanu and Popescu, 2010) and interstitial Cajal-like cells (Popescu et al., 2009).

3.6. Cardiovascular progenitor cell descent

Induction and specification of mesoderm commence during gastrulation of triploblastic organisms (Stern, 2004). All mesodermal cells share the expression of Brachyury, the founding member of the T-box family of transcription factors (Herrmann et al., 1990; Kispert and Herrmann, 1993). Its expression is downregulated during commitment and differentiation and upon patterning and specification of nascent mesoderm into derivative tissue (Kispert and Herrmann, 1994). As founders of all mesodermal cell types, the positioning of Brachyury positive cells along the primitive streak, together with distinct gradients of morphogen, predestine them already to a specific developmental fate. To mention just one out of many examples, the gradual expression of the transcription factor Goosecoid significantly influences Brachyury expression and mesodermal patterning (Niehrs et al., 1994) by a reciprocal inhibition of both genes (Artinger et al., 1997).

Brachyury positive, T+, primitive mesodermal cells can be divided into two populations. Those cells expressing the Tyrosine kinase receptor, FLK1, develop into hemangioblasts and consequently give rise to all descendants of the hematopoietic lineage (Kouskoff et al., 2005). The major part of the T+ cells, not expressing FLK1, differentiates into cardiomyocytes. Later, a subpopulation of FLK1 positive cells expressing the Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor α (PDGFRα) was reported to gave rise to a significant number of cardiomyocytes when stimulated with Activin, Nodal, and BMP4 (Kattman et al., 2006, 2011). These sets of data have been obtained from cells generated and isolated from embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies that allow, in contrast to in vivo studies, to manipulate developmental processes by growth factors and to isolate defined subpopulations of cells. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells in combination with preparative FACS can be used to define the biochemical status of a certain cell type expressing a common surface antigen. However, these methods exclude the effects of paracrine signaling on cell proliferation, commitment, and differentiation during cardiomyogenesis in vivo. Small differences in the culture conditions upon differentiation of embryonic stem cells and cardiovascular progenitor cells may easily lead to varying expression levels and thus to contradicting results.

MESP1, another transcription factor marking cardiogenic mesoderm (Kitajima et al., 2000; Saga et al., 1996, 2000, 1999), promotes cardiomyogenic differentiation (David et al., 2008). However, a population of MESP1 negative precursor cells was shown to contribute to parts of the ventricular cardiac conduction system (Kitajima et al., 2006), displaying again the ambivalent situation concerning the specificity of the used markers. Most recently, it has been demonstrated that Brachyury (David et al., 2011) and Eomesodermin (Costello et al., 2011) activate expression of MESP1 providing at least one of the numerous remaining missing links between primitive mesodermal and cardiovascular progenitor cells.

A third transcription factor, the LIM/homeodomain protein, ISL1, was identified in embryonic heart cells (Bu et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2003; Laugwitz et al., 2005; Moretti et al., 2006) that gave rise to cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells of the second heart field. ISL1 negative precursor cells were shown to be characteristic for the first heart field (Musunuru et al., 2010). In a more detailed hierarchy, Chien and colleagues suggest that ISL1 and FLK1 positive cells gave rise to vascular progenitors and finally to endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, whereas ISL1 and NKX2.5 positive precursors develop into smooth muscle cells, cells of the conduction system, and atrial, as well as ventricular cardiomyocytes (Laugwitz et al., 2008). Similar cell types could be derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (Moretti et al., 2010).

Anversa and colleagues isolated cKIT positive and lineage negative, Lin−, cells from adult hearts and subpopulations of progenitor cells expressing cKIT together with SCA1 or with both SCA1 and ISL1 and showed their differentiation potential into endothelial, smooth muscle, and cardiomyocyte lineages (Bearzi et al., 2007; Beltrami et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2007). These diverse cell types may represent different stages during cardiac stem cell development and differentiation (Ott et al., 2007). Likewise, a population of cKIT+, SCA1+ cells expressing P-glycoprotein, a member of the multidrug resistance ABC protein family that is found in side population cells, was identified in cardiac tissue (Barile et al., 2007).

cKIT+ progenitor cells were also found in human heart auricles giving rise to mesenchymal stem cells expressing the appropriate markers but no cardiac-specific genes (Aghila Rani et al., 2008; Gambini et al., 2010). These cells had a different phenotype, and when cocultured with cardiomyocytes, differentiated primarily into adipocytes and osteoblasts. As they developed into smooth muscle, endothelial, or cardiomyocytes to a much lesser extent, a noncardiac origin of these progenitors was suggested. In contrast, cKIT and nestin positive cells from postnatal murine hearts readily differentiated into endothelial, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle cells in vitro and in vivo (Tallini et al., 2009). This study also demonstrates that cKIT expression in postinfarction hearts does not reflect stem cell activity but rather demonstrates infiltration of cKIT positive blood cells. Notably, more than 60% of the CD34 positive blood cells are also positive for cKIT (Reisbach et al., 1993).

To obtain a population of cells with a differentiation potential more restricted to the vasculature, the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2, KDR, together with cKIT was used to isolate and expand resident coronary vascular progenitor cells from human myocardial samples (Bearzi et al., 2009; Leri et al., 2011). Some of these cells showed self-renewal, were clonogenic, and differentiated predominantly into endothelial and smooth muscle cells. However, as the expression of KDR did not exclude the differentiation into cardiomyocytes, a high degree of plasticity was again apparent. This suggests that most populations isolated with different surface antigens may be reprogrammed during isolation and culture and are not necessarily committed to a certain lineage.

SCA1 was used to isolate a population of cells displaying high telomerase activity, resembling the side population of hematopoietic stem cells (Oh et al., 2004), and cardiac progenitor cells, that were negative for CD34 and CD45 and did not express any endothelium or myocardium specific gene. Comparable cells were also isolated from human hearts (van Vliet et al., 2008) but differentiated into cardiomyocytes only upon exposure to 5-azacytidine (Oh et al., 2004). Later, it was demonstrated that a cardiac-specific side population of cells positive for SCA1, but negative for CD31, gave rise to functional cardiomyocytes when cocultured with adult cardiomyocytes. This suggests the requirement of the intimate contact with cardiac cells and most likely paracrine signaling to adopt a cardiomyocyte phenotype (Pfister et al., 2005). These data demonstrate further, that blood stem cells can be isolated from cardiac tissue, and question any attempts to isolate tissue-specific stem cells. Moreover, the group showed that CD34 and CD45 negative progenitor cells do not have the intrinsic information for differentiation into cardiomyocytes. Although other progenitor cell populations also express SCA1, this marker is most likely inadequate for the enrichment of tissue-specific cardiovascular progenitor cells. Most importantly, similar multipotent progenitor cells can be isolated from peripheral blood after Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF) stimulation (Cesselli et al., 2009).

These multipotent progenitor cells are clonogenic, self-renew in vitro for a long time, and, under appropriate environmental conditions, differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers. They express surface proteins similar to those present in mesenchymal stem cells but are developmentally younger. Their molecular and functional characteristics inevitably resemble human embryonic stem cells rather than any other somatic stem cell type described so far. In these multipotent progenitor cells, the pluripotency-specific transcription factors OCT4, Nanog, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC are expressed and the telomerase activity is comparable to that in embryonic stem cells. According to first reports, which still have to be confirmed by independent investigators, these multipotent progenitor cells of the blood migrate to most organs and integrate into the tissue by acquiring the structural and functional identity of the resident cell types. They give rise to endothelial cells of the blood vessels, form hepatocytes in the liver, and most astonishingly, transmigrate through the brain–blood barrier and give rise to neurons of the brain of immunodeficient mice. Finally, to make the current picture even more complex, very small embryonic-like stem cells, so-called VSELs, have been isolated from murine and human hearts (Zhang et al., 2011). This finding adds to the notion that stem cells isolated from a particular tissue or organ may well come from the bone marrow as the only source of stem and progenitor cells in the adult body.

It will be interesting to investigate whether all these cardiovascular progenitor cells are ontologically related to human embryonic stem cells. If they are, we have to consider the mechanisms of stem cells surviving developmental pressure during gastrulation. Possibly, niches in the early eutherian embryo allow the endurance of embryonic stem cells into adulthood, or mature cells find their way back to the embryonic stem cell phenotype similarly to mechanisms first demonstrated by Yamanaka et al. in vitro (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). Further, there may be ways to oscillate from a quiescent and more mature mesenchymal phenotype to a highly proliferative and immature state resembling embryonic stem cells. Similarities to the reversible epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition suggest that the study and comparison of both processes on the molecular level may lead to new fundamental insight into the process of naturally occurring reprogramming of somatic cells.

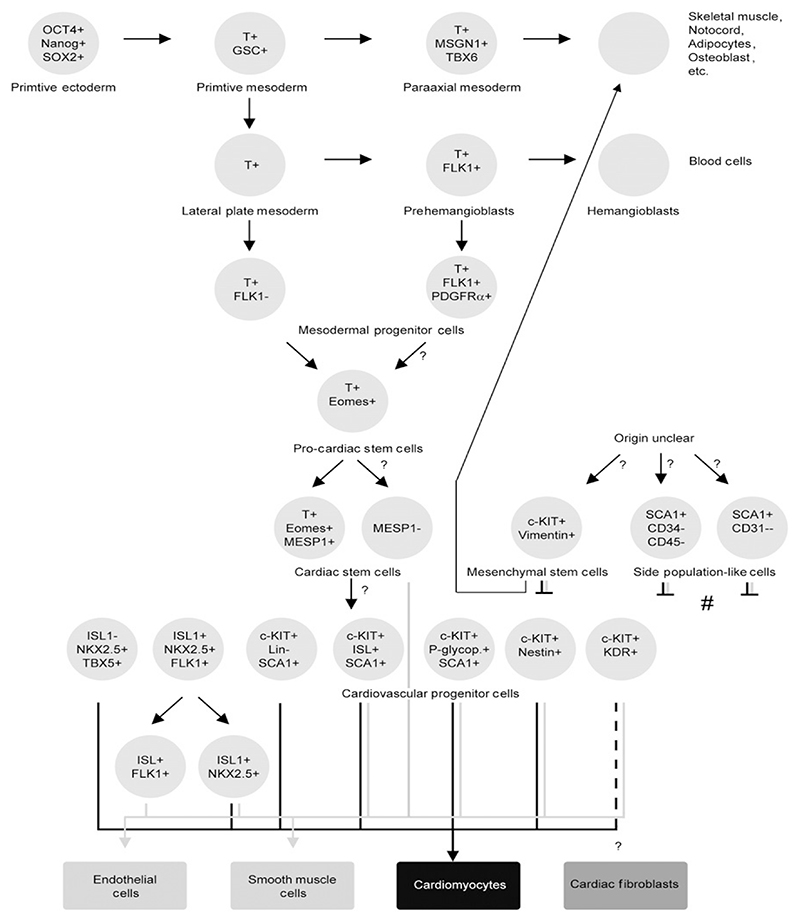

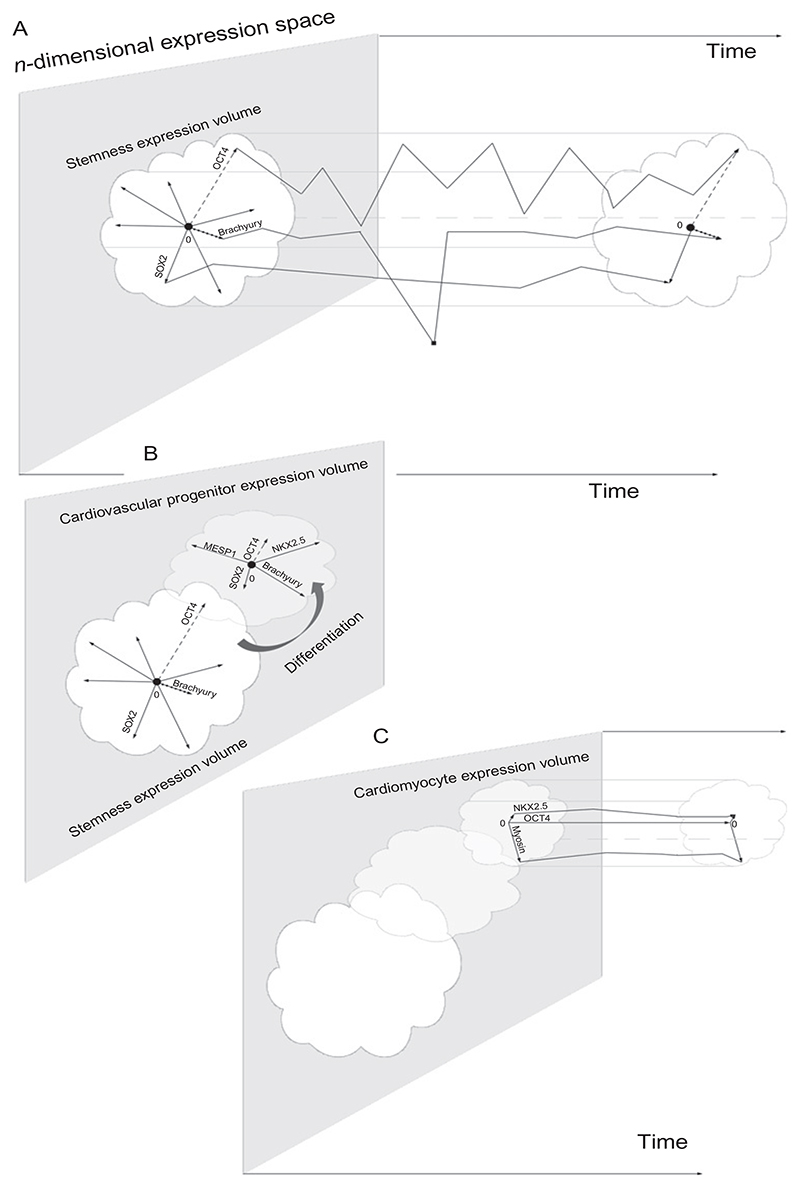

Taken together, this substantial work from many research institutions gave rise to several, however, only partially overlapping models how cardiac cells descend from primitive mesoderm and cardiovascular progenitor cells, respectively. In Fig. 7.1, we try to combine these different models of descent in one illustration. However, we state at the same time that presumably, this static view must be replaced by a more dynamic model displaying constant fluctuation of gene expression, which would better reflect the high plasticity and differentiation potential of all stem and progenitor cells. Thus, this picture may be still far away from reality. Most importantly, it is still unclear if a single type of cardiovascular progenitor cell stands at the root of a pedigree and if a hierarchy composed of different developmental stages of cardiovascular progenitor cells in the heart exists.

Figure 7.1.

Descent of cardiovascular progenitor cells from the primitive mesoderm. Molecules used to identify cell types (circles) are indicated. Rectangles, somatic cardiac cell types. Question marks, marks descent not directly supported by data or simply unknown. Black arrows in the lower part of the cartoon indicate differentiation of progenitor cells to cardiomyocytes, whereas gray lines indicate differentiation to smooth muscle and endothelial cells, respectively. The dashed line reflects only minor contribution to somatic cell type. (#) indicates the two cell types which differentiate to cells of the cardiac lineages only after reprogramming with 5-azacytidine or coculture with cardiomyocytes as feeder layers. Stemness markers: OCT4, Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; Nanog, homeodomain transcription factor; SOX2, sex determining region Y-box 2 transcription factor; mesodermal markers: T, Brachyury; GSC, goosecoid; MSGN, Mesogenin 1, a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor; FLK1, a receptor for the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; PDGFRα, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor alpha; Eomes, Eomesodermin, a maternal T-box transcription factor; MESP1, Mesoderm Posterior 1 homolog transcription factor; cKIT, stem cell growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase; SCA1, Stem cell antigen 1; Vimentin, a mesenchymal cell-specific type III intermediate filament protein; CD34, 45, and 31, cluster of differentiation antigens; ISL1, a LIM domain transcription factor; NKX2.5, a zinc finger transcription factor; Lin, a set of nine lineage markers of the hematopoietic lineages; P-glyop., P-glycoprotein, an ABC transmembrane transporter; Nestin, a type VI intermediate filament protein, expressed mainly in neuronal cells but also in some stem cells; KDR, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2; TBX5, T-box transcription factor.

4. Regulation of Cardiogenesis in Cardiovascular Progenitor Cells

4.1. Transcriptional regulation of cardiogenesis

4.1.1. Transcriptional regulation of cardiomyogenesis in cardiovascular progenitor cells

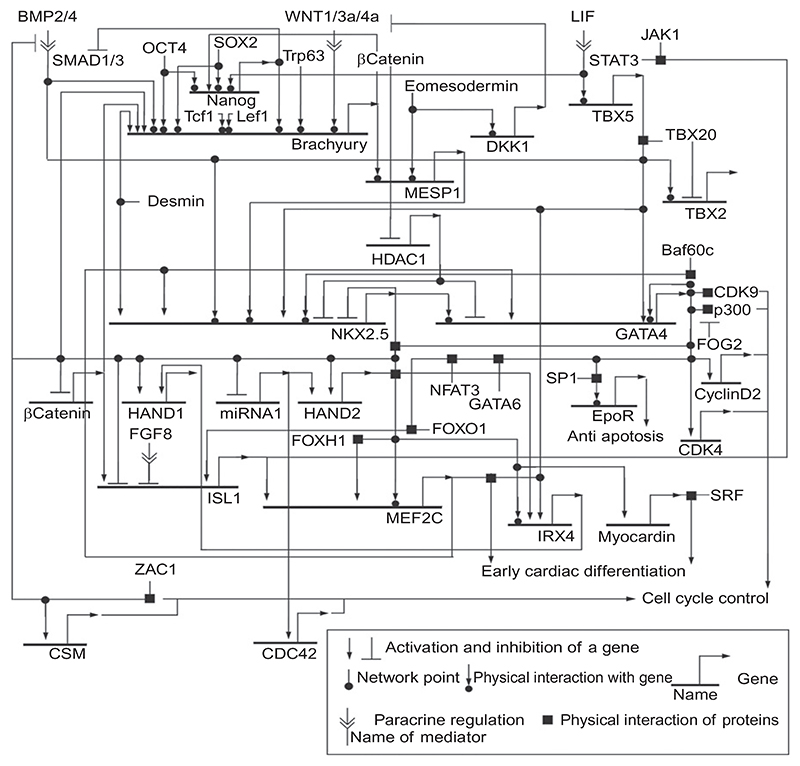

Currently, we do not have the knowledge about a continuous hierarchy of transcription factors regulating the expression of a cell in the primitive mesoderm in a way that it undergoes several defined developmental stages to finally become a cardiomyocyte. We have also very little data on the spatiotemporal interaction of the transcription factors involved in maintenance of the stem cell character and driving cardiomyogenesis in cardiovascular progenitor cells. Thus, we will focus first on two of the best studied transcription factors involved in early cardiomyogenesis the homeobox transcription factor NKX2.5, and the zinc-finger transcription factors GATA4. Both are essential in heart formation during embryogenesis, but neither can initiate cardiomyogenesis on its own in mammalian cardiovascular progenitor cells. Importantly, GATA and NK class proteins are coexpressed in many other tissues, and thus, interaction of these two transcription factors may be crucial for organogenesis. In the case of GATA4 and NKX2.5, it is very likely that they are also important regulators for late events during heart formation (Durocher et al., 1997). Beginning there, we shall try to extend the network of transcriptional regulation, first backward to the rather uncertain beginning in the primitive mesoderm, and second but more securely, toward committed and differentiated cardiomyocytes. Finally, we will try to construct an evidence-based network of physical and genetic interactions of transcription factors as a working model for further investigations.

4.1.2. NKX2.5

NK2 transcription factor related, locus 5, Nkx2.5, or cardiac-specific homeobox gene, Csx (Komuro and Izumo, 1993), codes for a member of the evolutionary highly conserved NK2 homeodomain transcription factor family (Kim and Nirenberg, 1989; Komuro and Izumo, 1993; Lints et al., 1993a,b) which are distantly related to the large Hox gene family. Nk2 genes, where NK stands for Nirenberg and Kim, the authors of the first paper describing these genes in D. melanogaster, are expressed in a tissue-specific manner at different times during mammalian embryogenesis (Harvey, 1996; Harvey et al., 2002). This occurrence suggests versatile roles in commitment and differentiation of cells and patterning of tissues and organs.

In the heart, NKX2.5 is first expressed in the cardiomyogenic progenitor cells during the formation of the lateral plate mesoderm in the late gastrula. NKX2.5 is temporally downregulated during differentiation of cardiomyocytes and then expressed at lower levels in the myocardium throughout the live of an organism. However, on the cellular level expression is likely to significantly vary between different cell types (Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 2007). NKX2.5 is a closely related homolog of Tinman, expressed in D. melanogaster (Bodmer, 1993; Bodmer et al., 1990) where it has an essential function in the development of the cardiac mesoderm (Grow and Krieg, 1998). In D. rerio, NKX2.5 seems to mark the earliest heart field and when ectopically expressed induces the initial but not late steps of cardiomyogenesis (Chen and Fishman, 1996). In mice, NKX2.5 expression starts at embryonic day 7.5 in the paired primordia arising from the splanchnic which builds, by midline fusion, the primitive heart tube (Kasahara et al., 1998). Most likely, NKX2.5 is expressed at low levels much earlier in cardiovascular progenitor cells because in embryoid bodies NKX2.5 expression can be detected on day 4 after initiation of in vitro differentiation (Hofner et al., 2007). Expression before the fusion of the primitive heart tube (Harvey, 1996; Moses et al., 2001) additionally suggests that it is expressed in still proliferating cardiovascular progenitor cells. This notion is heavily supported by data obtained from chicken (Schultheiss et al., 1997, 1995) and X. laevis (Sater and Jacobson, 1989; Sparrow et al., 2000), where cNkx2.5 and XNkx2.5 transcripts accumulate already in midgastrulation during formation of the primitive streak, and can be even detected in the pregastrulation epiblast of chicken embryos (Yatskievych et al., 1997). Nkx2.5-null mutation results in death before embryonic day 11 (Lyons et al., 1995; Tanaka et al., 1999a) and dominant negative mutants of Nkx2.5 negatively affected cardiomyogenesis (Jamali et al., 2001b). Although a rhythmically contracting primitive heart tube is formed in Nkx2.5-null mouse embryos, looping, chamber formation, and trabeculation are severely affected. The fact that NKX2.3 and NKX2.7 can step in for NKX2.5 during early cardiomyogenesis (Fu et al., 1998; Grow and Krieg, 1998; Tu et al., 2009) may explain this results. Otherwise we would have to conclude that NKX2.5 is not essential for cardiomyogenesis in at least a certain subpopulation of cells forming the paired heart primordia. In opposition to this interpretation stands the Nkx2.5 haploinsufficiency, the negative effects of various NKX2.5 point mutations in humans (Benson et al., 1999; Schott et al., 1998; Watanabe et al., 2002), and the fact that NKX2.5 is essential for the commitment of mesodermal cells into the cardiomyogenic lineage in teratocarcinoma cell-derived embryoid bodies (Jamali et al., 2001b).

Recent experiments designed to generate induced cardiovascular progenitor cells from fibroblasts suggest that NKX2.5 is indeed one of the key players for cells to become cardiomyocytes (Efe et al., 2011; Ieda et al., 2010; Takeuchi and Bruneau, 2009). Bruneau and colleagues and Srivastava and colleagues, respectively, demonstrated that ectopic expression of NKX2.5, GATA4, and TBX5 in neonatal murine cardiac fibroblasts is sufficient to convert them to cardiomyocytes. Ding and colleagues demonstrated that ectopic expression of the stemness transcription factors OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, and c-MYC for 4 days in combination with LIF withdrawal, and administration of BMP4, which induces NKX2.5 expression (Jamali et al., 2001a), is sufficient to generate significant numbers of cardiomyocytes from mouse embryonic fibroblasts. The latter demonstrated that this regime led to the upregulation of GATA4, MESP1, and ISL1 expression. Taken together, these data suggest that, in sharp contrast to Tinman in flies, none of the transcription factors identified so far in mammals is sufficient to induce cardiomyogenesis, and that most likely different sets of three or more myocardial transcription factors only suffice to initiate the myocardial differentiation program.

Most importantly, NKX2.5 has also a negative role in early cardiomyogenesis as it downregulates myocardial genes at a very early stage of cardiac induction (Prall et al., 2007). Later in cardiomyogenesis, NKX2.5 can also have detrimental effects as ectopic overexpression of NKX2.5 in mice suppresses the formation of the sinoatrial node (Espinoza-Lewis et al., 2011). Our own results demonstrate that murine cardiovascular progenitor cells temporally downregulate NKX2.5 expression when induced to differentiate in aggregates in vitro (submitted for publication). This phenomenon may be required for proper differentiation of cardiovascular progenitor cells along the cardiac lineage. In contrast, higher expression levels in cardiovascular progenitor cells perhaps maintain the stem cell state and at the same time prevent cardiovascular progenitor cells to escape the cardiomyogenic lineage. Based on the observation of a higher β-galactosidase activity in hearts of homozygous mice with a LacZ gene knocked into the Nkx2.5 locus, replacing the entire coding sequence, than in heterozygous mice (Tanaka et al., 1999b), a negative autoregulatory loop has been suggested for this gene. This model could explain the inhibitory roles and the temporal downregulation of NKX2.5 during cardiomyogenesis in cardiovascular progenitor cells.