ABSTRACT

Previous studies on the kinematics of pea plants’ ascent and attach behavior have demonstrated that the signature of their movement varies depending on the kind of support. So far, these studies have been confined to artificial supports (e.g. wooden sticks). Little is known regarding the conditions under which pea plants could rely on biological supports (e.g. neighboring plants) for climbing toward the light. In this study, we capitalize on the 3D kinematic analysis of movement to ascertain whether pea plants scale their kinematics differently depending on whether they aim for artificial or biological support. Results suggest that biological support determines a smoother and more accurate behavior than that elicited by the artificial one. These results shed light on pea plants’ ability to detect and classify the properties of objects and implement a movement plan attuned to the very nature of the support. We contend that such differences depend on the augmented multisensory experience elicited by the biological support.

KEYWORDS: Pea plants, kinematics, accuracy, climbing plants, circumnutations, plant behavior, plant movement

1. Introduction

Climbing plants need external support to maximize light absorption and develop vertically. Climbing plants have evolved several morphological tricks to clasp support, with the development of tendrils being the most highly sophisticated. Tendrils are modified leaves or flower peduncles sensitive to mechanical stimulation and capable of coiling around potential support.1 Tendrils show helical movements (i.e., circumnutation) to explore the environment, and once potential support is perceived, they orient their movement toward it.

Among tendril – bearing plants, pea plants (Pisum sativum L. from now on P. sativum) are the most studied at the genetic, morphological, physiological, and behavioral levels.2–9 Recent studies have capitalized on timelapse techniques to investigate the kinematical features of their movement when aiming at potential supports with different characteristics. Guerra et al.3 focused their analysis on support thickness. They examined a condition lacking potential support and one in which a support of a different thickness (i.e., thin or thick) was nearby. The results showed that when the plants perceived the presence of the support, they rapidly changed the direction of their circumnutating movement to approach and grasp it. The plants adjusted the kinematics of their coming and grasping movement in terms of their tendrils’ velocity and aperture (i.e., the maximum distance between the tips of the tendrils) depending on support thicknesses. Plants moved more quickly and opened their tendrils more in the presence of a thinner support.

One may ask why climbing plants should vary their kinematic patterning depending on the thickness of the support. A reasonable hypothesis is that the metabolic cost of morphological modulation and circumnutations may vary.10,11 Studies on different varieties of climbers suggest that if the size (diameter) of potential supports increases beyond some point, climbing plants are unable to maintain tensional forces and, therefore, lose attachment to the support.12–15 The fact that pea plants decrease their average and maximum tendril velocity in the presence of thick support may allow for acquiring more information about the thick support, which is considered a more demanding task, and implementing corrective adjustments to reduce the possible risk of errors. The reduced velocity may permit the plant to save energy and invest in the modulation and correction of the trajectories for a more accurate selection of the contact points to twine around the support.

Accuracy appears to be an essential aspect of climbers’ behavior. It is operationalized through corrective adjustments (i.e., submovements), which reduce any spatial discrepancy between the effector and target position.16 This principle is also applicable to P. sativum plants. As recently demonstrated, they produce more submovements in the presence of thicker than thin-ner supports, confirming that climbers found thicker supports more demanding.17

So far, these foundational studies concerning how pea plants scale their kinematics depending on their aim have been confined to inanimate supports (e.g., wooden sticks). Little is known regarding how they could rely on neighboring plants to climb toward the light. This condition can be observed in numerous climbing plants in open environments.18,19 When potential support is not readily available, climbing shoots twine around another plant, providing biological support.7,19

In the present study, we address this issue by asking whether there might be a difference in the kinematics of pea plants’ ascent and attach movements depending on the nature of the support they aim for. Differently from aiming at static support, aiming toward another plant implies keeping into account a variety of cues ranging from morphological (e.g., the size of the stem) to tactile (e.g., the information coming from the two plants touching parts) to chemical (e.g., volatile organic compounds), and motion (e.g., the movement of the hosting plant). A multisensory experience may have implications when establishing how to interact with biological support. If the biological support triggers a sensorial crosstalk between the agent and the support plant, we expect a smoother and more accurate behavior than the static/artificial support elicits. This should be revealed through kinematical analysis concerning accuracy measurements, namely the number of sub-movements and the end-point variability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Sixteen snow peas (Pisum sativum var. saccharatum cv Carouby de Maussane) were chosen as the study plants. Pea seeds were selected, potted, and kept at the conditions outlined below. We determined our sample size based on previous studies e.g.17

2.2. Experimental conditions

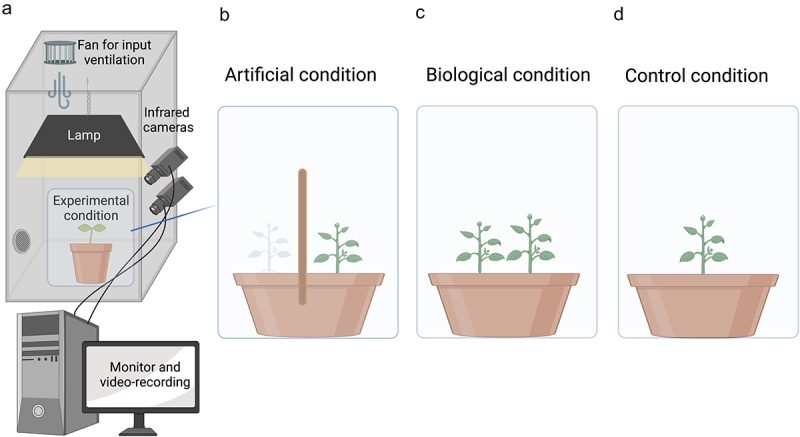

For the “biological” support condition (BC), pea plants were potted in the presence of another plant (see supplementary video BC_condition). In such circumstances, the plants were somewhat constrained to intertwine with the other plants to climb toward the light. The plant considered for the analysis was the one that finalized the movement, grasping the other plant at the level of the stem to ensure a firm attachment. For the “artificial” support condition (AC), pea plants grew in the presence of an inanimate wooden pole (see supplementary video AC_condition). The wooden pole was 60 cm in height and 1.2 cm in diameter (Figure 1). The in-ground part of the stimulus was 7 cm, while the above-ground part was 53 cm. The pole was 12 cm from the plant’s first unifoliate leaf. To equate the BC condition, we introduce another plant positioned 12 cm from the wooden pole (Figure 1). Note that this plant did not touch the wooden pole. In other words, it was a passive presence to counterbalance the number of plants considered for the BC condition. Note that despite the presence of two plants, only one plant was at a reachable distance and, therefore, in the position to grasp the support. A control condition (CC) was also considered in which an individual plant grew without support (see supplementary video CC_condition).

Figure 1.

In panel (a): Graphical representation of the experimental setup. A growth chamber with a controlled environment in terms of light and temperature and two infrared cameras recording the movement of the plants 24 hours per day. In panel (b): graphical representation of the experimental condition for the artificial support (AC condition). In panel (c): graphical representation of the experimental condition for the biological support (BC condition). In panel (d): graphical representation for the control condition (CC condition).

2.3. Dependent measures

The dependent variables specifically tailored to test our experimental hypothesis were chosen based on previous kinematic studies in pea plants6,7,10,17,20 and the literature concerning submovements and the fine structure of movement.17 If we zoom in on the fine structure of movement, we observe a primary movement and a series of submovements that perfect the homing phase. An easy way to recognize submovements is by considering how often the velocity waveform crosses the zero axis (i.e., submovement_velocity). The same applies to the acceleration profile (i.e., submovement_acceleration) and the jerk profile (i.e., submovement_jerk). These measures were: (i) the total duration of the tendrils’ circumnutations; (ii) the amplitude of mean velocity reached by the tendrils; (iii) the number of submovements_velocity computed as the total number of zero crossing from the velocity profile performed in the last 10% of the movement time; (iv) the number of submovements_acceleration computed as the total number of zero crossing from the acceleration profile performed in the last 10% of the movement time; (v) the number of submovements_jerk computed as the total number of zero crossing from the jerk profile performed in the last 10% of the movement time; (vi) the total number of submovements (acceleration, velocity and jerk) in the last 10% of movement time; (vii) the variability of the endpoint positions at the end of the movement.

2.4. Data analysis

In order to quantify the submovement_velocity, we defined the following parameter concerning velocity array computation in a discrete mood:

Where is the velocity computed at time point i, is distance from the stimulus on the XZ plane at time point i and is the time for point i referring to the last 10% of the movement.

To quantify the submovement_acceleration, we defined the following parameter concerning acceleration array in a discrete mood as a derivative of the velocity previously described:

Where is the acceleration computed at time point i, is the velocity computed at time point i and is the time for point i referring to the last 10% of the movement.

In order to quantify the submovement_jerk, we defined the following parameter concerning jerk array in a discrete mood as the rate of changes of the acceleration previously described:

Where is the jerk computed at time point i, the acceleration computed at time point i and as the time for point i referring to the last 10% of the movement.

The analysis used JASP21 nested within the environment R;22 see used packages: https://jasp-stats.org/r-package-list/). We performed the Shapiro-Wilk test to check the normality of the dataset. Since the data were not normally distributed, we conducted a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis Test to compare the different conditions’ movement duration and mean velocity. A Tukey’s post-hoc comparison has been performed. A parametric Student t-test was conducted to compare the dependent measures concerned with the submovements between the AC and the BC conditions. No analysis of submovements was possible for the CC condition because there was no grasping phase.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative results

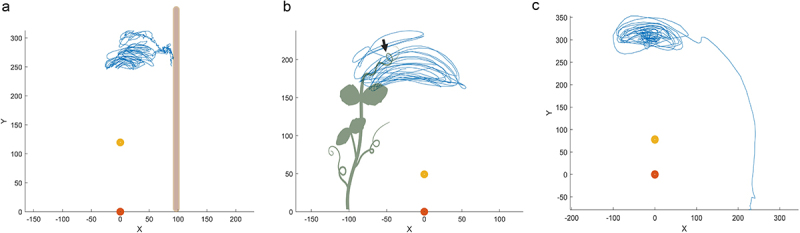

All plants exhibited a growing pattern characterized by circumnutation (Figure 2a–c). By observing the trajectories, we can see a different pattern for the two experimental conditions. AC is characterized by a higher density of circumnutation and smaller movements in the very proximity of the support than BC. This may allow for implementing more corrective adjustments to reduce the possible risk of errors. This careful approach may permit plants to save energy and invest in the modulation and correction of the trajectories for a more accurate selection of the contact points. For BC, circumnutations appear smoother, and the other plant is grasped with a single final maneuver, as indicated by the black arrow. There are no modulations or online corrections of the trajectories during the final phase. This suggests an easier and sharper movement concerning the one performed toward the artificial support. For the CC condition, the circumnutative movement ends with an irreversible plant drop represented by the linear trajectory directed toward the floor (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Example of trajectories for the AC (a), the BC (b), and the CC (c) condition. The yellow and orange dots represent the stem of the tracked plant. The blue line represents the trajectory of the tendril. The black arrow in Panel (b) represents the end of the movement for the BC, culminating with the final grasping phase on the support plant.

3.2. Kinematic results

The duration of the circumnutation is shorter, and the mean velocity is faster for the AC condition than the BC condition (see Tables 1–3), suggesting a more careful approach when the support is biological. The plants perform a different movement when there is no support in the surroundings.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the kinematic measures when comparing the AC and the BC conditions.

| Median | IQR | P-value of Shapiro-Wilk | Range | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total duration movement | BC | 111.000 | 39.000 | .857 | 144.000 | 93.000 | 111.000 | 132.000 |

| AC | 81.000 | 30.000 | <.001 | 120.000 | 69.000 | 81.000 | 99.000 | |

| CC | 63.000 | 18.000 | <.001 | 159.000 | 57.000 | 63.000 | 75.000 | |

| Mean velocity | BC | 1.582 | 1.694 | <.001 | 4.275 | 0.714 | 1.582 | 2.408 |

| AC | 2.571 | 1.956 | <.001 | 7.060 | 1.564 | 2.571 | 3.520 | |

| CC | 2.172 | 2.839 | <.001 | 6.484 | 1.174 | 2.172 | 4.013 |

Table 2.

Kruskal-Wallis non parametric ANOVA among AC, BC and control condition for the dependent measures considered.

| Cases | Statistic | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total duration | 146962.276 | 2 | <.001 |

| Mean speed | 42.620 | 2 | <.001 |

Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Table 3.

Post-hoc comparison for the dependent measures considered.

| Total duration | Mean Difference |

SE | t | ptukey | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | BC | −43.218 | 0.166 | 6.302 | <.001 |

| AC | −18.192 | 0.131 | 0.210 | 0.976 | |

| BC | AC | −1.020 | 0.172 | −5.941 | <.001 |

| Mean velocity | |||||

| CC | BC | 1.047 | 0.166 | 6.302 | <.001 |

| AC | 0.027 | 0.131 | 0.210 | 0.976 | |

| BC | AC | −1.020 | 0.172 | −5.941 | <.001 |

P-value adjusted for comparing a family of 3.

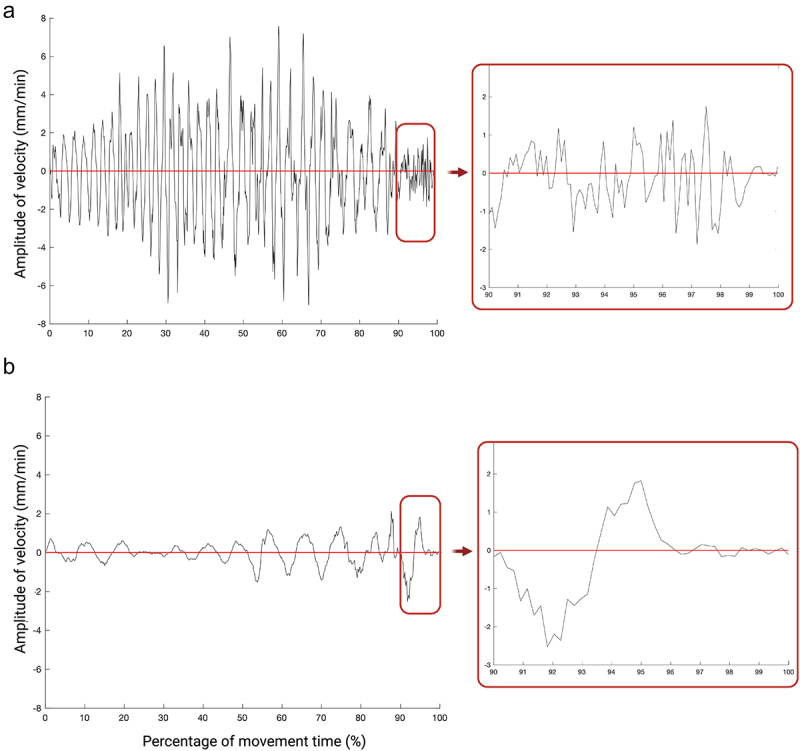

The number of submovements is higher for the AC than for the BC condition (see Tables 4 and 5). This is particularly evident in the final 10% of the movement (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for the specific dependent measures considered in terms of sub-movements for the AC and the BC conditions.

| Mean | Std. Deviation |

Shapiro-Wilk | P-value of Shapiro-Wilk |

Minimum | Maximum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submovement_type1 | BC | 48.000 | 13.148 | 0.884 | .207 | 33.000 | 66.000 |

| AC | 67.125 | 20.490 | 0.991 | .997 | 35.000 | 101.000 | |

| Submovement_type2 Submovement_type3 |

BC | 26.250 | 7.025 | 0.961 | .817 | 14.000 | 35.000 |

| AC | 43.250 | 21.684 | 0.948 | .688 | 17.000 | 81.000 | |

| BC | 37.500 | 7.982 | 0.887 | .220 | 26.000 | 46.000 | |

| Total submovement | AC | 59.375 | 26.403 | 0.969 | .891 | 24.000 | 100.000 |

| BC | 115.500 | 23.513 | 0.951 | .722 | 79.000 | 145.000 | |

| AC | 169.750 | 63.209 | 0.951 | .722 | 80.000 | 259.000 | |

| End point variability | BC | 18.072 | 11.294 | 0.977 | .949 | 0.369 | 34.438 |

| AC | 242.397 | 45.776 | 0.973 | .919 | 175.622 | 307.567 |

Table 5.

Independent samples student’s T-Test between AC and BC condition for the dependent measures considered.

| 95% CI for Cohen’s d |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | P | Cohen’s d | SE Cohen’s d | Lower | Upper | |

| Submovement_type1 | −2.222 | 14 | .043* | −1.111 | 0.572 | −2.156 | −0.033 |

| Submovement_type2 | −2.109 | 14 | .053 | −1.055 | 0.565 | −2.092 | 0.015 |

| Submovement_type3 | −2.243 | 14 | .042* | −1.122 | 0.573 | −2.168 | −0.042 |

| Total submovements | −2.275 | 14 | .039* | −1.138 | 0.575 | −2.186 | −0.055 |

Student’s t-test.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the velocity profile for exemplar plants for the two conditions. The callouts represent the last 10% of the movement, emphasizing the number of zero-crossings on the velocity profile representing the amount of type 1 submovements for the AC condition (a) and BC condition (b). Note that the number of submovements is much higher for the AC condition than for the BC condition.

For endpoint variability, this value for the AC condition (DS = 45.776) is more significant than for the BC condition (DS = 11.294) (see Table 4), suggesting that greater accuracy in determining the contact points on the wooden pole is needed to accomplish the final grasping.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate whether and how pea plants can differentiate, adjust, and ultimately regulate their ascent and attachment behavior according to the nature of potential support, namely biological (BC condition) or artificial (AC condition). To do this, we capitalized on the concept of accuracy, as exemplified via the occurrence of sub-movements and the measurement of end-point variability in plants.17

According to the findings, pea plants can categorize the type of support they aim for and act accordingly. Movement duration was shorter, and the velocity peak was higher for the AC condition than for the BC condition. Further, more sub-movements and a higher endpoint variability for the AC condition were found. Overall, this kinematical patterning indicates that the movement toward a conspecific is slower and characterized by a more accurate homing phase.

Given the absence of studies in the plant’s realm concerned with the issues at stake, it is tempting to discuss this aspect with a comparative and integrated approach.23,24 Animal research revealed that the kinematics of an agent’s movement during the interaction with a biological agent is different from that underlying the identical movement implying the interaction with an inanimate object,25,26 with the former characterized by a more accurate patterning mirroring the one described here for pea plants. The fact that our plants act toward a conspecific implies greater accuracy, which becomes particularly evident when looking at the differences in sub-movements and endpoint variability. For the BC condition, the observed number of sub-movements and the endpoint variability are lower than for the AC condition. One may say that it is somewhat counterintuitive that support still requires more adjustments than one that moves, and a more complex structure characterizes it. The greater smoothness of the movement associated with the BC condition could rely on exchanging information between the two plants at both roots and aerial levels. This may occur via a continuously updated interaction through volatile compounds. Plants use one of the most efficient and complex mechanisms to communicate volatile organic compounds (VOCs). A chemical “language” plants use for a variety of reasons, including exchanging useful information,27–29 adapting to environmental stress30 and mediating plant interactions31 with other organisms both above and below ground. Underground, this chemical communication occurs through root exudates that convey crucial information about the neighbors in the surrounding environment.32,33 Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that they may be able to discriminate detailed features of what surrounds them via a primitive visual system.34 Evidence suggests that the leaf upper and sub-epidermis comprise cells suitable to act as ocelli, allowing plants to experience a sort of vision.34,35 Support for this contention comes from studies on leaf mimicry in climbing plants36 and photoreceptor-mediated kin recognition of Arabidopsis seedlings.37 Both reports suggest plants can gather information about their environmental setting through vision-based inputs and behave accordingly.

In light of this, again, comparative literature might be of help. Several studies have been conducted on other species as primates,38,39 mammalian,40 and insects,41–45 describe how the integration of complementary information exchange affords numerous perceptual and behavioral benefits increasing accuracy46–48 and resulting in a smoother behavior.

Considering all the information, it seems that there are things in the world with which plants interact more smoothly than others. Identifying them is fundamental for plants. How do plants identify objects and separate conspecifics from all the rest? It seems that they can track and individuate the two things differently and interact appropriately with them, a method of identification that might be termed a property method. In this broad classification, members’ conspecifics are particularly important. Various properties may allow plants to uniquely identify conspecifics and segregate them from everything else, such as having a particular morphological schema or speaking a natural chemical ‘language.’ It is reasonable to suppose that plants can discriminate a wide array of properties not limited to basic low-level stimulus features but rather extend to the complex properties that could allow them to single out conspecifics uniquely. Further, such abilities might not just be “perceptual.” Not only can they discriminate other plants from artifacts, as it seems here, but they can also form specific expectations of what they can do with them and behave accordingly. Plants seem equipped with all the necessary mechanisms for applying the proposed ‘property method,’ at least to plants and objects. Nonetheless, we do not know whether they use the concepts and property detectors to identify objects. This study has been the first step in shedding light on the highly controlled and accurate mechanisms plants put into work when acting toward different kinds of supports with other properties. We now know plants are good at detecting property changes and planning the movement and accuracy accordingly. What remains to be uncovered is what the metaphysics of this kind of object identification could look like.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the European Union [ERC, ROOMors, Grant Number 101096728] to UC. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible. B.B. is supported by a MUR grant [n. 20227ZYLH9] to U.C.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, B.B. and U.C.; methodology, B.B., and U.C.; software, V.S.; formal analysis, B.B.; investigation, B.B.; data curation, B.B., S.G. S.V.; writing – original draft preparation, B.B. and U.C.; writing – review and editing, B.B., U.C., V.S. and S.G.; supervision, U.C.; project administration, U.C.; funding acquisition, U.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available in ZENODO at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10852877.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2024.2355739

References

- 1.Jaffe MJ, Galston AW.. The physiology of tendrils. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1968;19(1):417–7. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.19.060168.002221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerra S, Bonato B, Wang Q, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Baccinelli W, Bulgheroni M, Castiello U.. Kinematic evidence of root-to-shoot signaling for the coding of support thickness in pea plants. Biology. 2022;11(3):11, 405. doi: 10.3390/biology11030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerra S, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Bulgheroni M, Baccinelli W, D’Amico E, Gómez A, Massaccesi S, Ceccarini F, Castiello U. Flexible control of movement in plants. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16570. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53118-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreplak J, Madoui MA, Cápal P, Novák P, Labadie K, Aubert G, Bayer PE, Gali KK, Syme RA, Main D. A reference genome for pea provides insight into legume genome evolution. Nat Genet. 2019;51(9):1411–1422. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smýkal P, Horáček J, Dostálová R, Hýbl M. Variety discrimination in pea (Pisum sativum L.) by molecular, biochemical and morphological markers. J Applied Gen. 2008;49(2):155–166. doi: 10.1007/BF03195609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonato B, Simonetti V, Bulgheroni M, Wang Q, Guerra S, Quaggiotti S, Ruperti B, Castiello U. Evidence of motor intentions in plants: a kinematical study. J Comp Psychol. 2023;137(4):228–237. doi: 10.1037/com0000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonato B, Simonetti V, Bulgheroni M, Wang Q, Guerra S, Quaggiotti S, Ruperti B, Castiello U. “United we stand, divided we fall”: intertwining as evidence of joint action in pea plants. AoB Plants. 2024;16(1):plad088. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plad088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra S, Bonato B, Wang Q, Ceccarini F, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Bacinelli W, Bulgheroni M, Castiello U. The coding of object thickness in plants: when roots matter. J Comp Psychol. 2021;135(4):495–504. doi: 10.1037/com0000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Q, Barbariol T, Susto GA, Bonato B, Guerra S, Castiello U. Classifying circumnutation in pea plants via supervised machine learning. Plants. 2023;12(4):12, 965. doi: 10.3390/plants12040965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ceccarini F, Guerra S, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Bulgheroni M, Baccinelli W, Bonato B, Castiello U. Speed–accuracy trade-off in plants. Psychon Bull Rev. 2020;27(5):966–973. doi: 10.3758/s13423-020-01753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe NP, Isnard S, Gallenmüller F, Speck T. Diversity of mechanical architectures in climbing plants: an ecological perspective. In: Herrel A, Speck T, Rowe NP, editors. Ecology and biomechanics: a mechanical approach to the ecology of animals and plants. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2006. p. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrasco‐Urra F, Gianoli E. Abundance of climbing plants in a southern temperate rain forest: host tree characteristics or light availability? J Veg Sci. 2009;20(6):1155–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01115.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goriely A, Neukirch S. Mechanics of climbing and attachment in twining plants. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97(18):184302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.184302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putz FE. The natural history of lianas on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Ecology. 1984;65(6):1713–1724. doi: 10.2307/1937767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putz FE, Holbrook NM. Biomechanical studies of vines. In: Putz FE, Mooney HA, editors. The biology of vines. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991. p. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fradet L, Lee G, Dounskaia N. Origins of submovements during pointing movements. Acta Psych. 2008;129(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceccarini F, Guerra S, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Bulgheroni M, Baccinelli W, Bonato B, Castiello U. On-line control of movement in plants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;564:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianoli E. The behavioural ecology of climbing plants. AoB Plants. 2015;7:lv013. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe NP, Speck T. Stem biomechanics, strength of attachment, and developmental plasticity of vines and lianas. In: Schnitzer SA, Bongers F, Burnham RJ, Putz FE, editors. Ecol Lianas. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2015. p. 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonetti V, Bulgheroni M, Guerra S, Peressotti A, Peressotti F, Baccinelli W, Ceccarini F, Bonato B, Wang Q, Castiello U. Can plants move like animals? A three-dimensional stereovision analysis of movement in plants. Animals. 2021;11(7):1854. doi: 10.3390/ani11071854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.JASP Team . JASP (Version 0.17) [Computer Software]. 2023. https://jasp-stats.org/.

- 22.R Development Core Team, R . A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castiello U. (Re)claiming plants in comparative psychology. J Comp Psychol. 2020;135(1):127. doi: 10.1037/com0000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castiello U. Plant intelligence from a comparative psychology perspective. Biology. 2023;12(6):819. doi: 10.3390/biology12060819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becchio C, Sartori L, Castiello U. Toward you: The social side of actions. Curr Dir Psych Sci. 2010;19(3):183–188. doi: 10.1177/0963721410370131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becchio C, Sartori L, Bulgheroni M, Castiello U. The case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: a kinematic study on social intention. Consc Cog. 2008;17(3):557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonato B, Peressotti F, Guerra S, Wang Q, Castiello U. Cracking the code: a comparative approach to plant communication. Commun Integr Biol. 2021;14(1):176–185. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2021.1956719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karban R, Shiojiri K, Huntzinger M, McCall AC. Damage‐induced resistance in sagebrush: volatiles are key to intra‐and interplant communication. Ecology. 2006;87(4):922–930. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[922:DRISVA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pichersky E, Noel JP, Dudareva N. Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science. 2006;311(5762):808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.1118510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin IT, Halitschke R, Paschold A, Von Dahl CC, Preston CA. Volatile signaling in plant-plant interactions: “talking trees” in the genomics era. Science. 2006;311(5762):812–815. doi: 10.1126/science.1118446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ueda H, Kikuta Y, Matsuda K. Plant communication: mediated by individual or blended VOCs? Plant Sign Beh. 2012;7(2):222–226. doi: 10.4161/psb.18765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biedrzycki ML, Jilany TA, Dudley SA, Bais HP. Root exudates mediate kin recognition in plants. Comm Integr Bio. 2010;3(1):28–35. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.1.10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semchenko M, Saar S, Lepik A. Plant root exudates mediate neighbour recognition and trigger complex behavioural changes. New Phyt. 2014;204(3):631–637. doi: 10.1111/nph.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baluska F, Mancuso S. Vision in plants via plant-specific ocelli? Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(9):727–730. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gavelis GS, Hayakawa S, White Iii RA, Gojobori T, Suttle CA, Keeling PJ, Leander BS. Eye-like ocelloids are built from different endosymbiotically acquired components. Nature. 2015;523(7559):204–207. doi: 10.1038/nature14593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White J, Yamashita F. Boquila trifoliolata mimics leaves of an artificial plastic host plant. Plant Signal Behav. 2022;17(1). doi: 10.1080/15592324.2021.1977530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crepy MA, Casal JJ. Photoreceptor mediated kin recognition in plants. New Phitol. 2015;205(1):329–338. doi: 10.1111/nph.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bremmer F. Multisensory space: from eye‐movements to self‐motion. J Physiol. 2011;589(4):815–823. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanz F, Moret V, Rouiller EM, Loquet G. Multisensory integration in non-human primates during a sensory-motor task. Front Hum Neurosc. 2013;7:799. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi I, Demir I, Oh S, Lee SH. Multisensory integration in the mammalian brain: diversity and flexibility in health and disease. Philos Trans Royal Soc B. 2023;378(1886):20220338. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huber R, Knaden M. Homing ants get confused when nest cues are also route cues. Curr Bio. 2017;27(23):3706–3710. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu ZL, Ho SH. Bioactivity of the essential oil extracted from Evodia rutaecarpa Hook f. et Thomas against the grain storage insects, Sitophilus zeamais Motsch. And Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). J Stor Prod Res. 1999;35(4):317–328. doi: 10.1016/S0022-474X(99)00015-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wohlgemuth S, Ronacher B, Wehner R. Ant odometry in the third dimension. Nature. 2001;411(6839):795–798. doi: 10.1038/35081069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolf R, Heisenberg M. Basic organization of operant behavior as revealed in Drosophila flight orientation. J Comp Physiol A. 1991;169(6):699–705. doi: 10.1007/BF00194898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knaden M, Graham P. The sensory ecology of ant navigation: from natural environments to neural mechanisms. Ann Rev Entom. 2016;61(1):63–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gentilucci M, Daprati E, Gangitano M. Implicit visual analysis in handedness recognition. Consc Cogn. 1998;7(3):478–493. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1998.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patchay S, Castiello U, Haggard P. A cross-modal interference effect in grasping objects. Psych Bull Rev. 2003;10(4):924–931. doi: 10.3758/BF03196553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patchay S, Haggard P, Castiello U. Cross-modal links in action: evidence for an object-centred reference frame for control of grasping. Exp Brain Res. 2005;23:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available in ZENODO at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10852877.