Abstract

Background

Dental glass-ceramics have limited strength and are unsuitable for high-stress-bearing areas. Zirconia stands out as a popular choice for reinforcing dental glass-ceramics due to its biocompatibility and high fracture toughness.

Objectives

The objective of the study is to investigate the effect of an increase in zirconia (25, 30, 35 and 50 wt%) on microstructure, chemical solubility, hardness, fracture toughness, and brittleness index of fluorosilicate glass systems for dental restorative applications.

Material and methods

The fluorosilicate glass frit was obtained through the melt-quench technique. The glass frit was ball-milled with 25, 30, 35 and 50 wt % of 3 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia (G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z). The composites were sintered to 1000 °C for 48h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. The glass frit was subject to differential scanning calorimetry. Phase analysis and microstructural characterization were carried out. The crystallite size of zirconia and glass-ceramics, micro-hardness, indentation fracture toughness, brittleness index, and chemical solubility were evaluated.

Results

Phase analysis reveals tetragonal and monoclinic zirconia with minor peaks of forsterite, fluorphlogopite, norbergite, and spinel. Their microstructures reveal the characteristic house-of-cards arrangement of fluorophlogopite crystals with dispersed zirconia. The results of hardness and fracture toughness show a statistically significant improvement with an increase in zirconia content. The crystallite size of zirconia and fluorophlogopite crystals with aspect ratio, brittleness index, and chemical solubility declined as the zirconia content increased.

Conclusions

Increase in zirconia content from 25 wt % to 50 wt % in heat-treated fluorosilicate glass systems reveals non-reactive zirconia with a stable glass matrix and limits the growth of fluorphlogopite crystals with a house-of-cards microstructure. This results in a range of properties suitable for dental restorations of enhanced hardness, and improved fracture toughness. Despite these improvements, the material maintains its machinability with reduced chemical solubility.

Keywords: Zirconia, Fluorosilicate glass-ceramics, Dental ceramics, Dental restorations

1. Introduction

Dental glass-ceramics, particularly those based on lithium disilicate, are primarily recommended for use in anterior and premolar crowns and three-unit bridges for replacing missing teeth. However, they have limited strength and are unsuitable for posterior teeth involving high-stress-bearing areas in the oral cavity [1,2]. To address these issues, various methods were explored to enhance their mechanical properties, such as dispersion strengthening, reinforcing with zirconia for transformation toughening, and introducing residual compressive stresses [3,4]. Dispersion strengthening involves introducing a separate material phase within the glass-ceramic, effectively impeding the formation of cracks. The emerging cracks encounter resistance from these dispersed crystals within the glass matrix, which ultimately increases the toughness and strength of the glass-ceramic systems. Transformation toughening revolves around the phase transformation of zirconia. The tetragonal phase of zirconia plays a role in reinforcing the material through localized transformation into a monoclinic phase. This transformation results in a volume expansion near the crack tips, creating local compressive stresses that hinder crack propagation and prevent fractures from occurring [3,4]. Crack deflection and toughening are further facilitated by the differential coefficients of thermal expansion between the glass matrix and the dispersed material phase, which generates residual compressive stress [5,6].

Given the background provided on methods of strengthening glass-ceramics, zirconia stands out as a popular choice for reinforcing dental glass-ceramics due to its biocompatibility and high fracture resistance. Glass-ceramics are typically produced through nucleation and crystallization through heat treatment. Recently, there have been advancements in the development of glass-ceramics, including zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate and virgilite-based glass-ceramics like Vita Supranity and Celtra Duo [7,8]. Glass compositions containing fluorosilicate have also gained recognition because of their ease of machinability, compatibility with living tissues, and resistance to chemical wear [9–16]. Researchers have previously explored the application of fluorosilicate-based glass-ceramics in dental restorations, including castable options like DICOR and machinable alternatives such as MACOR. However, dental restorations made from fluorosilicate-based glass-ceramics have exhibited only moderate mechanical strength and limited durability in clinical settings. Consequently, efforts have been made to enhance their mechanical properties [17].

Traditionally, zirconia (ZrO2) has been used as a catalyst to induce crystallization in silicate glass systems by promoting phase separation and internal nucleation [9–11]. Adding zirconia to fluorosilicate glass systems has had a significant impact on various aspects, such as crystallization behavior, microstructure, and properties like coefficient of thermal expansion, glass stability, glass transition temperature, machinability, and mechanical characteristics [12–16]. Essentially, zirconia reduces the activation energy required for crystallization, making nucleation and crystallization easier, resulting in a dense and uniform microstructure with interlocked card-like fluorophlogopite crystals [11]. The inclusion of zirconia in mica-based glass has been observed to enhance bending strength and fracture toughness while improving machinability [13].

The potential of a dental restorative material is determined by clinically important attributes like mechanical properties, wear resistance, chemical solubility, thermal characteristics, compatibility with living tissues, processability and optical qualities [3,4]. Numerous studies have explored the role of zirconia in fluorosilicate-based glass systems for dental restorations. Adding 20 wt% of 3 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia enhanced the mechanical properties of fluorosilicate glass-ceramics without compromising brittleness index or chemical solubility [14,15]. However, increasing the zirconia content did not enhance mechanical properties in spark plasma-sintered lithium silicate glass ceramics, instead, it increased viscosity of the glass and hindered crystal growth [18]. An increase in wt.% of zirconia to a commercial dental ceramic powder resulted in zirconia agglomerates and reduced its wear resistance. The microstructure of glass-ceramic depends on a critical threshold of the amount of zirconia added. For example, adding less than 10 vol% of zirconia in the glass matrix refines the microstructure of the glass-ceramic and acts as a nucleating agent [19]. However, increasing the content beyond 10 vol% of zirconia particles tends to impede phase separation of the glass matrix and reduces its nucleation [19]. Therefore, the quantity of zirconia in fluorosilicate glass ceramics can significantly affect the microstructure of a glass-ceramic and further its properties.

The present study investigates the effect of an increase in the zirconia content (25 wt% till 50 wt%) on the microstructure, and clinically relevant properties such as chemical solubility, hardness, fracture toughness, and brittleness index of fluorosilicate glass systems, intended for dental prosthetic restorative applications.

2. Materials and methodology

2.1. Glass preparation

Precursor powders of fluorosilicate base glass composition (44.5 SiO2–16.7 Al2O3–9.5 K2O–14.5 MgO–8.5 B2O3–6.3F (wt.%)) were ball milled at 300 rpm for 6 h to ensure homogenous mixing. Precursor powders used for the glass batch formation are presented in Table 1. The ball-milled glass powder was melted in a platinum crucible in an electrical furnace and quenched in cool, deionized water to obtain glass frit. The particle size distribution of the glass frit was assessed using a laser particle analyzer (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Instruments) and is shown in Fig. 1. The glass frit powder (D50 ~3.08 μm) was ball milled with 25 wt%, 30 wt%, 35 wt % and 50 wt% of 3 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) (Tosoh, Japan) (D50 ~50 nm) for homogeneity. The weight percentages of zirconia were in increments of 5 wt% from 25 wt% till 35 wt%, and further with a 15 wt% increment for 50 wt%. The fluorosilicate glass with 25–30-35-50 wt % YSZ, will be abbreviated as G25Z, G35Z and G50Z respectively and YSZ as zirconia throughout the paper. The respective nomenclatures are presented in Table 2. The addition of zirconia to the base glass and further sintering constitutes a glass-ceramic composite. The composites were sintered to 1000 °C for 48h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min based on the results of differential scanning calorimetry, described in Section 2.4 and Section 3.1.

Table 1. Precursor powders used for fluorosilicate glass batch.

| Precursor powders | Oxide constituent | Wt.% |

|---|---|---|

| Silica gel (400–700 mesh) | SiO2 | 44.5 |

| Aluminium oxide Active (Neutral) | Al2O3 | 16.7 |

| Magnesium carbonate (99.5 % Analytical Reagent) | MgO | 14.5 |

| Potassium carbonate anhydrous (99.5 % Analytical | K2O | 9.5 |

| Reagent) | ||

| Boric acid crystal (99.5 % Extra pure) | B2O | 8.5 |

| Ammonium fluoride (98 % Analytical Reagent) | F−1 | 6.3 |

Fig. 1. Particle size distribution of fluorosilicate glass frit.

Table 2. Nomenclature of samples of fluorosilicate glass with varying wt. % of zirconia.

| Sample | Glass frit (wt. %) | Zirconia (wt. %) |

|---|---|---|

| G-25Z | 75 | 25 |

| G-30Z | 70 | 30 |

| G-35Z | 65 | 35 |

| G-50Z | 50 | 50 |

2.2. Phase analysis and crystallite size using X-ray diffraction

Phase analysis of sintered samples using X-ray Diffraction (Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray Diffractometer, 2.2 kW X-ray source of Cu anode operated at 40 kV Voltage and 40 mA current at 1.6 kW power with a step size of 0.026°) was carried out on a representative sample of each group to determine major and minor phases. The average crystallite size of zirconia was calculated by the analysis of prominent peaks obtained from XRD through the application of Scherrer’s Equation (Eq. (1)):

| (1) |

where, D represents the average crystallite size in nanometers (nm), K is the shape factor (assumed to be 0.9), λ denotes the X-ray wave-length (0.15406 nm), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak observed at the angle θ, and θ is the Bragg’s angle of diffraction.

2.3. Microstructural characterization

The samples were polished with silicon carbide papers (SiC) under water cooling. Polishing was done on the top surfaces using 0.5 μm diamond paste and colloidal silica to obtain an acceptable optical surface for viewing under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The representative sample of each group was etched using 12 % hydrofluoric acid for 3 min. Etched samples were gold coated using a sputter coater (Quorum Technologies, UK) for 30 s with 40 mA. SEM (Schottky Field Emission, Gemini Column) with energy dispersive spectroscopy was used for microstructural analysis. The size of the crystals in the microstructure of fluorosilicate glass following heat treatment was assessed using ImageJ software. A histogram was constructed based on a minimum of 20 particles, with a Gaussian-shaped distribution.

2.4. Differential scanning calorimetry

The ball-milled base glass powder was placed in a calorimeter and heated from room temperature to 1000°C at the rate of 10°C/min to determine the optimum sintering temperature for heat treatment.

2.5. Mechanical characterization

Vickers micro-hardness was used to evaluate the hardness and indentation fracture toughness of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic zirconia composites.

2.5.1. Micro-hardness

Vickers indentation test was used to evaluate the micro-hardness of discs of 12 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness on five samples in each group. The polished surfaces were indented (n = 5 indentations per sample) using a micro-hardness tester (Wilson® VH1102, Buehler, Illi-nois) with an indent load of 1 kg with a dwell time of 10 s (ASTM E92). The indent diagonals were measured using an optical microscope using the formula (Eq. (2)), where P is the indentation load (N), and d is the average diagonal length (mm [20]. Load-displacement data obtained during indentation was used to obtain reduced elastic modulus using the Oliver–Pharr formula [21].

| (2) |

2.5.2. Indentation fracture toughness

Vicker’s indenter made indentations at a load of 49 N on five samples in each group (n = 3 indentations per sample). Crack lengths were measured using SEM, and the mode I fracture toughness (KIc) was calculated using the following formula in Eq. (3). Here, P is the indentation load (N), H is hardness (GPa), E is elastic modulus (GPa), and c is the average crack length (μm) [22].

| (3) |

2.5.3. Brittleness index

The brittleness index was estimated by the ratio of hardness to fracture toughness of a material following the formula (Eq. (4)), where in Hv is Vickers hardness in GPa and KIC in MPa.m1/2 [23].

| (4) |

2.6. Chemical solubility

A thermostatic shaking incubator (N-Biotek, NB-250V), was used to experiment with ten samples of each group of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic zirconia composites. The specimens were of 12 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness polished till # 600 grit, ultrasonicated in distilled water, and dried at a temperature of 150°C for 5h, weighed to an accuracy (0.01 mg) in a digital weighing balance (Mettler Teledo). The samples were then placed in 25 ml of 4 % freshly reconstituted glacial acetic acid in the shaking incubator at a temperature of 60°C at 200 rpm for 16h. The samples were washed and dried in the hot air oven at a temperature of 150°C for 5h and weighed again. Chemical solubility was calculated based on the weight loss measured in the samples per unit surface area as per the ISO-6872 guidelines.

3. Results

3.1. Phase analysis and microstructural characterization

The results of differential scanning calorimetry shown in Fig. 2, illustrate the melting range of the fluorosilicate glass frit with enthalpy of fusion and enthalpy of crystallization. With the melting range between 1029 °C and 1122 °C, the temperature of 1000 °C was optimized to avoid melting of the glass-ceramic composites. The heat treatment of 48 h was based on the previous work by the authors [14,15]. The rate of heating should be sufficiently slow to provide enough time for crystallization and to prevent the glass body from deformation [24]. Therefore, a heat treatment time of 48 h with a slow heating rate of 5 °C/min was followed. The heat treatment schedule of sintering the fluorosilicate glass frit was optimized at 1000 °C for 48 h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

Fig. 2. Thermogram of differential scanning calorimetry of fluorosilicate glass frit.

Phase analysis of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites of G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z reveals major tetragonal and monoclinic peaks of zirconia with minor peaks of crystalline phases such as fluorphlogopite, norbergite, and spinel, as shown in Fig. 3. The strong intensity of the major zirconia peaks indicates their complete crystallinity, making them appear more pronounced than the minor phases present in the crystallized glass-ceramic. With an increase in the zirconia content from 25 wt% to 50 wt%, the average crystallite size of zirconia was reduced from 27 nm (G-25Z) to 17 nm (G-50Z), as shown in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

XRD plot of G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z with peaks of tetragonal (♦), monoclinic (♣), fluorphlogopite (♠), spinel (ε), and norbegite (Ψ).

Table 3. The sizes of zirconia crystallites and fluorophlogopite crystals with aspect ratio.

| Sample | Crystallite size of zirconia (nm) | Crystal size of fluorophlogopite (thickness) (μm) | Average crystal aspect ratio (length/breadth) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-25Z | 27 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| G-30Z | 22 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| G-35Z | 19 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| G-50Z | 17 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

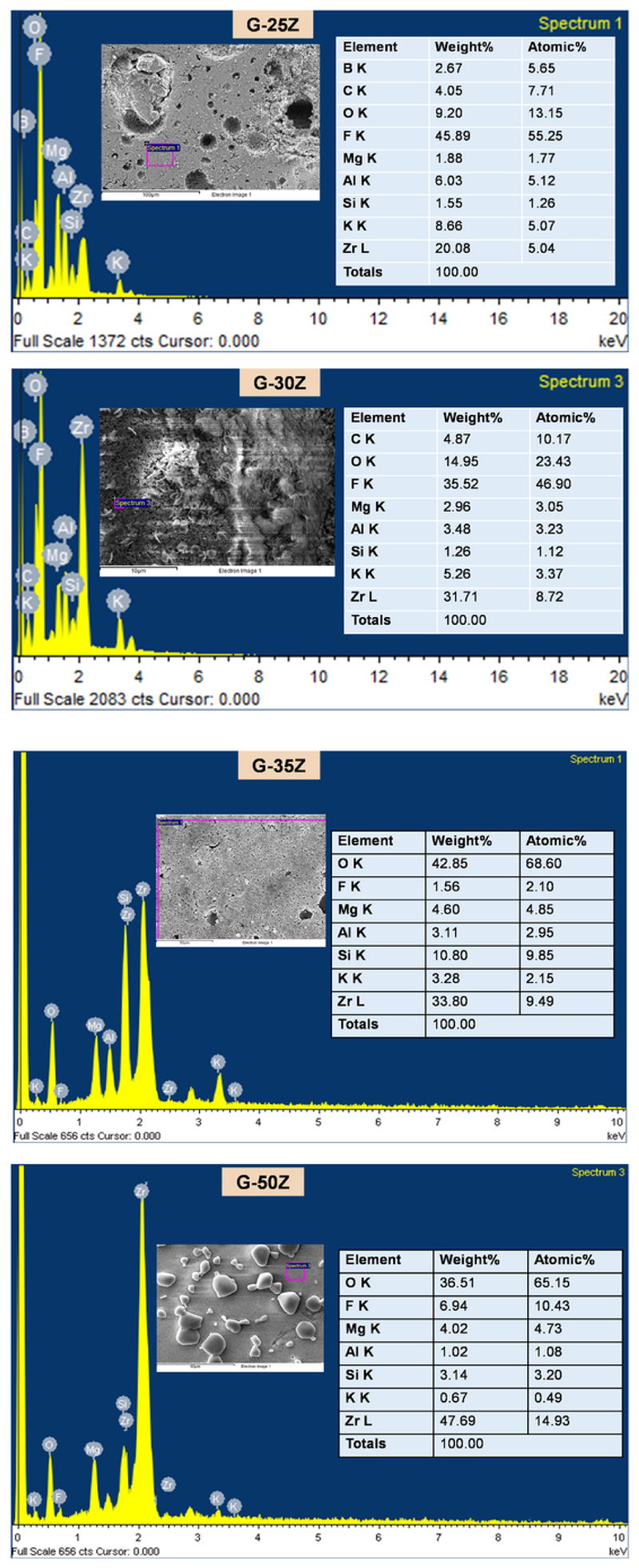

The microstructures observed in G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z are presented in Fig. 4 (a and b) and Fig. 5 (a, c, and e) with EDS (Energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis) in Fig. 6. The figures show the characteristic house-of-cards arrangement of fluorphlogopite crystals with dispersed zirconia. The crystal size (thickness) of fluorphlogopite crystals in each of the fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites are presented in Fig. 4 (c and d) and their particle size distribution with histogram is presented in Fig. 5 (b and d). The average size (thickness) of the crystals and aspect ratio (ratio of length and breadth) for G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z are presented in Table 3. Furthermore, in Fig. 5 (e and f), the apparent influence of an increase in zirconia content on the crystal size (thickness) can be observed.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopic images of microstructures of (a) G-25Z, and (b) G-30Z, and particle size distribution of flourophlogopite crystals of (c) G-25Z, and (d) G-30Z.

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron microscopic images of microstructures of (a) G-35Z, and (b) G-50Z, the particle size distribution of flourophlogopite crystals of (c) G-35Z, and (d) G-50Z, and (e) yellow arrows, and (f) graph of the relationship of crystallite size of zirconia with the flourophlogopite crystal size of G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z, and G-50Z. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 6.

Energy dispersive spectroscopic analysis of G-25Z, G-30Z, G-35Z and G-50Z.

3.2. Mechanical properties

Table 4 presents the properties of hardness, fracture toughness, and brittleness index of each of the glass-ceramic-zirconia composites. The brittleness index of the glass-ceramic-zirconia composites reduced with an increase in zirconia content. The results of hardness show a statistically significant improvement of hardness from 5.6 GPa (G-25Z) to 6.87 GPa (G-50Z) and fracture toughness values from 2.32 MPa m1/2to 7 MPa m1/2 with an increase in zirconia content. Improved fracture toughness of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites in the form of crack deflection can be seen in Fig. 7(a–d), crack pinning in Fig. 8(a–e), and crack blunting in Fig. 9.

Table 4. Mechanical properties of fluorosilicate glass with varying wt. % of zirconia × Dissimilar superscripts mean statistically significant.

| Fluorosilicate glass with varying wt.% of zirconia | Microhardness (GPa) | Fracture toughness (MPa.m1/2) | Brittleness index (μm−1/2) | Elastic modulus (GPa) | Chemical solubility (μg/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-25Z | 5.6 ± 1.2a | 2.3 ± 0.3a | 2.43 | 115 ± 3.5 | 28.7 ± 3.7a |

| G-30Z | 5.7 ± 1.0a | 2.4 ± 0.4a | 2.38 | 117 ± 3.6 | 24.6 ± 3.8 b |

| G-35Z | 6.5 ± 0.2b,c | 7.6 ± 1.2 b,c | 0.86 | 125 ± 5.0 | 20.8 ± 1.3c |

| G-50Z | 6.8 ± 0.5c | 7.0 ± 0.4c | 0.98 | 156 ± 6.5 | 24.4 ± 0.5 b |

| G14 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 2.5 | 73 ± 1.0 | ~58 |

Fig. 7.

Scanning electron microscopic images. (a) cracks emanating during Vicker’s indentation fracture toughness test depicting crack deflection, and (b–d) magnified images of crack deflection.

Fig. 8.

Scanning electron microscopic images. (a) cracks emanating during Vicker’s indentation fracture toughness test depicting crack pinning, and (a*and b-e) magnified images of crack pinning.

Fig. 9.

Scanning electron microscopic images. (a) cracks emanating during Vicker’s indentation fracture toughness test depicting crack blunting, and (a*) magnified image of crack blunting.

3.3. Chemical solubility

In our current investigation, the chemical solubility of the fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites declined as the zirconia content increased, as shown in Table 4. Importantly, all tested materials remained within the specified thresholds for chemical solubility of 100 μg/cm2 for body ceramics and 2000 μg/cm2 for core ceramics, according to the ISO 6872 guidelines. Additionally, the chemical solubility of all fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites complies with the limits established by the ISO guidelines.

3.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluations were conducted using SPSS-20.0 (IBM, USA) commercial software. Data is expressed as mean values accompanied by error bars representing standard deviations. Student t-tests were employed to analyze mechanical properties, considering statistical significance at a threshold of p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The results of phase assemblage, microstructural analysis with mechanical property characterization, and chemical solubility of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites will be discussed in the following sections.

4.1. Microstructure-property correlation

In the present study, phase analysis reveals the retention of tetragonal and monoclinic peaks of yttria-stabilized zirconia with minor peaks of fluorphlogopite, norbergite and spinel. The detection of a tetragonal phase signals a non-reactive zirconia with a stable glass matrix. Non-reactive zirconia with silica glass matrix in rate-controlled sintering condition shows the low tendency of fluorosilicate-based glass to dissolve zirconia particles. The phase stability of the tetragonal phase of zirconia is generally complemented by the crystallite size of zirconia falling within the critical range of 16–30 nm. The average crystallite size of zirconia in Table 3, confirms the phase stability of zirconia in fluorosilicate glass [25]. The crystallite size was calculated using XRD in the present study. The use of small-angle X-ray scattering and high-temperature X-ray diffraction are recommended to determine the crystallite size of zirconia in future studies [26].

The microstructure reveals plate-like crystals (aspect ratio less than 2 is plate-like, in Table 3) that are randomly oriented and their formation could be attributed to the two-dimensional anisotropic crystal growth, as seen in Figs. 4 and 5. The formation of stable fluorphlogopite crystal formation indicates its evolution from the metastable norbergite and chondrite phases in the matrix of potassium aluminosilicate. As the rate of crystal growth depends on the temperature, a slow heating rate of 5 °C/min is associated with crystal growth with slight glass deformation [24].

The thickness of fluorphlogopite crystal particles in each of the fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites is presented in Fig. 4 (c and d) and Fig. 5 (c and d). The increase in zirconia content from 25 wt%, 30 wt%, 35 wt% to 50 wt% reduced the thickness of fluorphlogopite crystal particles from 2.52 μm, 1.73 μm, and 1.09 μm, to 0.11 μm and the aspect ratio from 1.52 to 1.05, respectively indicating the role of zirconia in reducing crystal growth. Compared to the current study findings of aspect ratio, the addition of 20 wt% of zirconia to fluorosilicate glass-ceramics produced an average aspect ratio of 3 of fluorophlogopite crystals [14]. The addition of zirconia beyond 20 wt% reduced the aspect ratio of fluorphlogopite crystals. The findings of the study corroborate with other studies, wherein zirconia addition was found to limit crystal sizes in transparent spodumene glasses [27]. The addition of 5 % YSZ had a significant effect on mica glass-ceramics, with a reduction of crystal morphology from tabular to equiaxed and a slow-down of crystal growth kinetics [28]. The addition of zirconia was reported to increase the viscosity of the glass matrix and inhibit crystal growth [18]. The role of zirconia on the microstructure of fluorosilicate-based glass-ceramics is typically as a nucleating agent encouraging heterogeneous nucleation and crystallization. The degree to which this phenomenon happens relies on factors such as the composition of the glass, conditions during heat treatment, and the structural function of zirconia [25].

The improved hardness of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites could be related to the reduced size and aspect ratio of fluorphlogopite crystals, with increased zirconia content, as shown in Table 3 with reduced aspect ratio. The reduced size of fluorphlogopite crystals offers high resistance to indentation, reported in similar studies [29]. Further, the increase in hardness is supplemented by adding zirconia content to the composites. Table 4 demonstrates the improved hardness and fracture toughness observed in fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites.

The fracture toughness of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites was evaluated in this study. Strength and fracture toughness are important properties used to evaluate the performance of ceramics, but they measure different aspects of the material. While strength gives an immediate measure of load-bearing capacity, fracture toughness provides a deeper understanding of the ceramic’s durability and resistance to crack propagation, making it a more inherent and reliable property for assessing the material’s long-term performance. The strength of a ceramic depends on the distribution of flaws or defect population in the specimens under loading configurations, and the surface finish of the specimen and can be affected by processing and handling which may not closely resemble clinical conditions. In contrast, fracture toughness is a more inherent and comparable measure of ceramic structure as surface flaws less influence it. Therefore, it is a more reliable indicator of a ceramic’s durability and structural integrity than strength [14,30].

The enhanced property of fracture toughness can be attributed to the phenomenon of transformation toughening through the addition of partially stabilized zirconia particles to the glass matrix. Some of the criteria essential for achieving transformation toughening are zirconia particles remaining undissolved by the host matrix. This was possibly facilitated by fluorosilicate glass [5,6]. Other factors include maintaining a zirconia particle size typically below 500 nm. The critical size of tetragonal zirconia influences the phase transition of zirconia. In the present study, the average particle size of zirconia particles was 50 nm. To further ensure transformation toughening, the host microstructure must be strong enough to retain zirconia particles in their tetragonal form during cooling and control the amount of retained t-zirconia within the matrix [5,6,31]. The retention of the tetragonal phase of zirconia can be confirmed from phase analysis in Fig. 3.

Micro-cracking at the crack tip, resulting from the internal residual stresses arising during cooling from sintering temperature, and phase transition contributes to enhanced fracture toughness [32–34]. Crack deflection is typically credited to several factors. One of them is the local stress fields arising due to the mismatch of elastic modulus between tetragonal zirconia and glass-ceramic [25]. Crack deflection by fluorophlogopite crystals is one of the mechanisms of resisting crack propagation, as shown in Fig. 7(a–d). Crack deflection is a toughening mechanism wherein the crack deviates from its natural path due to its interaction with incorporated particles in the matrix. Crack deflection also occurs due to the mismatch of the coefficient of thermal expansion between zirconia and glass matrix and dispersion strengthening. The role of zirconia in fluorosilicate glass systems in crack deflection has been attributed to dispersion toughening. Similar studies report a large mismatch in the thermal coefficient of thermal expansion between zircon and mica glass matrix as one of the reasons attributed to crack deflection in zirconia-containing mica-apatite glass systems. In the present study, crack pinning can be attributed to the minor peak phases of fluorophlogopite crystals of fluorosilicate glass-ceramic, and its interaction with zirconia as seen in Fig. 8(a–e). When a crack meets inorganic particles, it gets pinned and curves around them. This phenomenon happens when there is a smaller distance between particles due to a relatively high concentration, creating river-like patterns from crack pinning and the obstructive effects of nanoparticles. Crack blunting by zirconia particles can be seen in Fig. 9 (a). In crack blunting, the tip of a propagating crack becomes less sharp and more rounded. The crack tip undergoes plastic deformation, which lowers the stress concentration at the crack tip and slows the crack’s growth [31,5,6]. A comparison of the mechanical properties of earlier developed zirconia-reinforced fluorosilicate-based glass systems with the present study is presented in Table 5. Zirconia addition of 35–50 wt% to fluorosilicate glass systems showed higher fracture toughness and hardness compared to other studies. It should be noted that the indentation method of measuring fracture toughness used in the present study has the merits of being simple and easy to follow, however, the method has limitations of overestimation of fracture toughness when compared to single-edge V-shaped notch beam (SEVNB) method.

Table 5. Properties of earlier developed zirconia-reinforced fluorosilicate based glass-ceramics.

| Sample | Heat treatment temperature (°C), time and heating rate | Vickers hardness (GPa) | Elastic modulus (GPa) | Fracture toughness (MPa.m1/2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorosilicic mica with 30 wt% of nano-zirconia33 | 1150 °C for 20 min at 15 °C/min | – | – | 4.20 ± 0.11 (IF) |

| Mica apatite with 10 wt% zirconia5 | 1060 and 1170 °C for 4 h at 20 °C/min | 4.4 ± 0.82 | – | 1.4 ± 0.16 (SEVNB) |

| Mica with 15 wt% Zirconia6 | 1060–1130 °C for 4h at 20 °C/min | 4.3 ± 0.64 | – | 1.3 ± 0.07 (SEVNB) |

| Bioverit with 20 wt% zirconia16 | 1040–1130 °C for 0.5–4h | – | 59 | 2.5 (IF) |

| Mica glass-ceramic with 20 wt% zirconia14 | 850 for 2h at 25 °C/min followed by 1080 °C for 48 h at 10 °C/min | 9.2 ± 0.57 | 125 ± 5.0 | 3.6 ± 0.20 (IF) |

| Mica glass-ceramics with 5 wt% zirconia13 | 643 °C for 10 min followed by crystallization at 897 °C for 10 min both with a 55 °C/min | 3.3 ± 1 | – | – |

| 30 vol% mica with zirconia28 | 1150–1250 °C for 2 h at 10 °C/min | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 153 | 3.9 ± 0.1 (IF) |

| 36 vol% mica with zirconia | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 146 | 3.9 ± 0.1 (IF) | |

| 49 vol% mica with zirconia | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 123 | 3.5 ± 0.3 (IF) | |

| *Present work G-50Z | 1000 °C for 48 h at 5 °C/min | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 156 ± 6.5 | 7.0 ± 0.4 (IF) |

| G-35Z | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 125 ± 5.0 | 7.6 ± 1.2 (IF) | |

| G-30Z | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 117 ± 3.6 | 2.4 ± 0.4 (IF) | |

| *Celtra Duo (10 wt% zirconia to lithium silicate glass-ceramics) | Fully crystallized | 7 | – | 2.6 |

| *VITA Supranity DC | 7 | 70 | 2 |

4.2. Brittleness index

For a restorative dental material to be considered machinable, it needs to find a balance between hardness (its resistance to cutting) and toughness (its resistance to failure). The “brittleness index,” calculated as the ratio of hardness to fracture toughness, provides an estimate of machinability [23,35]. Typically, a material requires a brittleness index of less than 4.3 μm−1/2 to be considered machinable [35]. As seen in Table 4, the brittleness index was favorable for G-25 and G-30Z and least for G-35Z and G-50Z. This could be due to the increased concentration of zirconia (35–50 wt% YZP) contributing to high fracture toughness. This high fracture toughness leads to a reduced brittleness index, thereby affecting machinability. Further, increased zirconia reduced the crystal growth and aspect ratio of fluorosilicate crystals. Fluorosilicate crystals contribute to machinability due to the presence of cleavage between the mica planes. At least one-third by volume of mica must be present for satisfactory machinability. Optimum machinability was obtained by two-thirds by volume (which means 66.6 % of glass and 33.33 % of zirconia [36]. An increase in the wt.% zirconia in mica glass systems has shown an increase in hardness and toughness with a reduction in the brittleness index, suggesting their machinable nature.

4.3. Chemical solubility

The endurance of a dental material is determined by its capacity to withstand the corrosive conditions of the oral cavity, which includes exposure to acidic and alkaline substances. ISO-6872 prescribes the assessment of a dental material’s chemical solubility when in direct contact with fluids, suggesting that it should be below 100 μg/cm2 when subjected to 4 % glacial acetic acid for 16 h [37]. Ceramics can be vulnerable to the acidic and alkaline conditions present in the oral environment. While ceramics are generally recognized for their high bio-compatibility and chemical durability, degradation in ceramics may increase the risk of wear, dissolution, and the ingestion of leached ions by the patient. Such occurrences can potentially lead to toxic effects and systemic implications for the patient [37].

The precursor of the currently examined glass-ceramic composed of fluorosilicate involves a foundational glass containing silicon oxides, alumina, potassium (alkali), magnesium (alkaline earth), and boron with fluoride. The solubility mechanism operates through the selective removal of alkali ions from the glass matrix and the dissolution of the glass network. However, crystallized glasses exhibit greater resistance to leaching compared to those in the glass phase [37]. The inclusion of alumina and zirconia in fluorosilicate glass-ceramic immobilizes alkali ions, resulting in reduced chemical solubility in composites with zirconia [38]. To enhance chemical durability, a mica glass ceramic system requires 7 wt% of zirconia [37]. Optimal chemical durability is achieved in a tetra silicic fluorosilicate system formulation with a minimum of 0.5 wt % Al2O3 and 2 wt % zirconia [39]. Hence, the diminished chemical solubility in fluorosilicate glass-ceramic-zirconia composites (Table 4) can be attributed to their partially crystallized state and the presence of glass modifiers and zirconia in their composition.

5. Conclusions

Increase in the zirconia content from 25 wt % to 50 wt % in heat-treated fluorosilicate glass systems reveals non-reactive zirconia with a stable glass matrix and limits the growth of fluorphlogopite crystals with a house-of-cards microstructure. This results in a range of properties suitable for dental restorative applications, including enhanced hardness, and improved fracture toughness. Importantly, the material maintains its machinability with reduced chemical solubility despite these improvements.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance, Early Career Fellowship for Clinicians and Public Health Research with the grant number IA/CPHE/18/1/503943.

Footnotes

Uncited reference

[31].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sivaranjani Gali: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Akshay Arjun: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. H.B. Premkumar: Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors of the manuscript, hereby declare no conflict of interest with the manuscript. All authors disclose we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) our work. The following are the contributions of each of the authors for the manuscript titled” “Zirconia toughened fluorosilicate glass-ceramics for dental prosthetic restorations” authored by Sivaranjani Gali, Akshay Arjun, and H.B. Premkumar, as an original article in Ceramics International.

Contributor Information

Sivaranjani Gali, Email: sivaranjanigali.pr.ds@msruas.ac.in.

Akshay Arjun, Email: akshayarjun.2014@gmail.com.

H.B. Premkumar, Email: premhb@gmail.com.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Tiu J, Belli R, Lohbauer U. Contemporary CAD/CAM materials in dentistry. Curr Health Rep. 2019;6:250–256. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pollington S, Van Noort R. An update of ceramics in dentistry. Int J Clin Dent. 2009;2:283–307. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anusavice KJ, Shen C, Rawls HR. Phillips’ Science of Dental Materials. Elsevier Health Sciences; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sakaguchi RL, Powers JM. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials. Elsevier/Mosby; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Montazerian M, Alizadeh P, Eftekhari Yekta B. Pressureless sintering and mechanical properties of mica glass–ceramic/Y-PSZ composite. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2008;28:2687–2692. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Montazerian M, Alizadeh P, Eftekhari Yekta B. Processing and properties of a mica-apatite glass–ceramic reinforced with Y-PSZ particles. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2008;28:2693–2699. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Holland W, Beall G. Glass–ceramic Technology. second ed John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu X, Yao X, Zhang R, et al. Recent advances in glass-ceramics: performance and toughening mechanisms in restorative dentistry. J Biomed Mater Res. 2024;112:e35334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.35334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Garai M, Sasmal N, Molla AR, et al. Effects of nucleating agents on crystallization and microstructure of fluorophlogopite mica-containing glass–ceramics. J Mater Sci. 2014;49:1612–1623. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mei QX, Yun SX, Meng XZ, Liang Z. Effects of ZrO2 on the microstructure of a mica glass–ceramic. Chin J Struct Chem. 2004;23:1111–1116. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang P, Shen Z, Zhang J. Effect of TiO2 and ZrO2 on the crystallization of B2O3–MgO–SiO2 slag. Chin J Mater Res. 1998;12:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghaffari M, Alizadeh P, Rahimipour MR. Sintering behavior and mechanical properties of mica-diopside glass–ceramic composites reinforced by nano and micro-sized zirconia particles. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2012;358:3304–3333. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Taruta S, Watanabe K, Kitajima K, Takusagawa N. Effect of titanium addition on crystallization process and some properties of calcium mica–apatite glass–ceramics. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2003;321:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gali S, Ravikumar K, Murthy BVS, Basu B. Zirconia toughened mica glass ceramics for dental restorations. Dent Mater. 2018;34:e36–e45. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gali S, Ravikumar K. Zirconia toughened mica glass ceramics for dental restorations: wear, thermal, optical and cytocompatibility properties. Dent Mater. 2019;35:1706–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.08.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Verné E, Defilippia R, Carlb B, Vitale Brovaronea C, Appendinoa P. Viscous flow sintering of bioactive glass-ceramic composites toughened by zirconia particles. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2003;23:675–683. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Malament KA, Socransky SS, Malament KA, Socransky SS. Survival of Dicor glass-ceramic dental restorations over 14 years: Part I. Survival of Dicor complete coverage restorations and effect of internal surface acid etching, tooth position, gender, and age. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ghayebloo M, Alizadeh P. Effect of zirconia nanoparticles on ZrO2-Bearing Lithium-Silicate glass ceramic composite obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;110:1751–6161. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Santos RLP, Buciumeanu M, Silva FS, Souza JCM, Nascimento RM, Motta FV, Henriques B. Tribological behavior of zirconia-reinforced glass–ceramic composites in artificial saliva. Tribol Int. 2016;103:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ponton CB, Rawlings RD. Vickers indentation fracture toughness test part 1: review of literature and formulation of standardized indentation toughness equations. Mater Sci Technol. 1989;5 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Oliver WC, Pharr GM. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J Mater Res. 2004;19:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Anstis G, Chantikul P, Lawn B, Marshall D. A critical evaluation of indentation techniques for measuring fracture toughness, I, direct crack measurements. J Am Ceram Soc. 1981;46:815–818. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tsitrou EA, Northeast SE, van Noort R. Brittleness index of machinable dental materials and its relation to the marginal chipping factor. J Dent. 2007;35:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].El-Meliegy EAM, van Noort R. Glasses and glass ceramics for medical applications. 2011. Glasses and Glass Ceramics for Medical Applications.

- [25].Shearer A, Montazerian M, Deng B, Sly JJ, Mauro JC. Zirconia-containing glass-ceramics: from nucleating agent to the primary crystalline phase. Int J Ceram Eng Sci. 2024:1–32.:e10200 [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fritzsche JO, Rüdinger B, Deubener J. Slow coarsening of tetragonal zirconia nanocrystals in a phase-separated sodium borosilicate glass. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2023;606:122206 [Google Scholar]

- [27].Luo Y, Qu C, Mauro JC. High-toughness transparent glass-ceramics with petalite and β-spodumene solid solution as two major crystal phases. J Am Ceram Soc. 2022;105:6116–6127. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Srichumpong T, Pintasiri S, Heness G, Leonelli C, Meechoowas E, Thongpun N, Teanchai C, Suputtamongkol K, Chaysuwan D. The influence of yttria-stabilized zirconia and cerium oxide on the microstructural morphology and properties of a mica glass-ceramic for restorative dental materials. J Asian Ceram Soc. 2021;9:926–933. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Baik DS, No KS, Chun JS, Cho HY. Effect of the aspect ratio of mica crystals and crystallinity on the microhardness and machinability of mica glass-ceramics. J Mater Process Technol. 1997;67:50–54. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Thompson JY, Anusavice KJ, Naman A, Morris HF. Fracture surface characterization of clinically failed all-ceramic crowns. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1824–1832. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hannink RHJ, Kelly PM, Muddle BC. Transformation toughening in zirconia-containing ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc. 2000;83:461–487. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Richerson DW. Modern Ceramic Engineering. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1992. pp. 731–762. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yang H, Wu S, Hu J, Wang Z, Wang R, He H. Influence of nano-ZrO2 additive on the bending strength and fracture toughness of fluoro-silicic mica glass–ceramics. Mater Des. 2011;32:1590–1593. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Davidge RW. Mechanical Behaviour of Ceramics. CUP Archive. 1979.

- [35].Boccaccini AR. Machinability and brittleness of glass-ceramics. J Mater Process Technol. 1997;65:302–304. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Holand W, Beall G. Glass–ceramic Technology. second ed. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Anusavice KJ. Degradability of dental ceramics. Adv Dent Res. 1992;6:82–89. doi: 10.1177/08959374920060012201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Paul A, Zaman MS. The relative influences of Al2O3 and Fe2O3 on the chemical durability of silicate glasses at different pH values. J Mater Sci. 1978;13:1499–1502. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Adair PJ. Glass-ceramic dental products. [Accessed 22 March 2017];US patent No 4431420. 1982 available at : https://www.google.com/patents.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.