Abstract

The missing link between cross-sectoral resource management and full-scale adoption of the water-energy-food (WEF) nexus has been the lack of analytical tools that provide evidence for policy and decision-making. This study defined WEF nexus sustainability indicators, from where an analytical model was developed to manage WEF resources in an integrated manner using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). The model established quantitative relationships among WEF sectors, simplifying the intricate interlinkages among resources, using South Africa as a case study. A spider graph was used to illustrate sector performance as related to others, whose management is viewed either as sustainable or unsustainable. The model was then applied to assess progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals in South Africa. The estimated integrated indices of 0.155 and 0.203 for 2015 and 2018, respectively, classify South Africa’s management of resources as marginally sustainable. The model is a decision support tool that highlights priority areas for intervention.

Keywords: Adaptation, Climate change, Composite indices, Resilience, Livelihoods

1. Introduction

Global grand challenges such as climate change, land degradation, migration, increasing population growth, rapid urbanisation, among others, always require integrated approaches to sustainably manage resources and ensure sustainable access and availability (Gomiero, 2016; Sherbinin et al., 2007). Such integrated solutions require stake-holder buy-in and public awareness from the onset as it calls for a paradigm shift from the usual ‘silo’ approach to a cross-cutting one that recognises and facilitates cross-sectoral convergence and coherence in resource management (Daher and Mohtar, 2015; Leck et al., 2015). One such approach is the water-energy-food (WEF) nexus, which came into prominence after the Bonn conference in 2011 (Hoff, 2011; Kling et al., 2017), and has since grown into an internationally accepted framework for integrated and sustainable resource planning and management, particularly in this era of resource scarcity and climate change (Kurian, 2017). It has evolved into an approach that provides opportunities for cross-sectoral collaboration and harmonisation of policies to sustainably address complex problems (Fürst et al., 2017). The WEF nexus distinguishes itself from previous cross-sectoral approaches such as the Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), which is water-centric, by being polycentric and considering all sectors on equal terms (Leck et al., 2015; Nhamo et al., 2018).

The essence of the WEF nexus is three dimensional as it is used either as an analytical tool, a conceptual framework, and for discourse (Keskinen et al., 2016). As an analytical tool, the approach systematically applies quantitative and qualitative methods to understand the interactions among WEF resources; as a conceptual framework it simplifies an understanding of WEF linkages to promote coherence in policy-making and enhances sustainable development, and as a discourse, it is a tool for problem framing and promoting cross-sectoral collaboration (Albrecht et al., 2018). Thus, the WEF nexus approach is a pathway for understanding complex and dynamic interlinkages between issues related to water, energy and food security. In this regard, it can also be used to monitor the performance of the WEF nexus indicators that are related to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goals 2, 6 and 7 (Stephan et al., 2018). The WEF nexus is an innovative integrated approach through which cross-sectoral sustainability indicators can be derived. Sectoral approaches to resources management risk major and unintended consequences as they often fail to identify and manage cross-sectoral synergies and trade-offs (Leck et al., 2015; Mohtar and Daher, 2016).

Although the WEF nexus is envisaged to address the three interlinked global security concerns of access to water, sustainable energy, and food security, there are gaps that remain to turn the WEF nexus into a fully-fledged operational framework (Albrecht et al., 2018). For this reason, the concept has been criticised for lack of clarity and practical applicability (Cairns and Krzywoszynska, 2016) and some have even branded it as a repackaging of the IWRM (Benson et al., 2015). The criticisms have been aided by the substantial amount of literature that has been published recently highlighting the importance of the WEF nexus as a conceptual framework and as a discourse, but evidently lacking on analytical tools that can be used to provide real-world solutions (Liu et al., 2017; Mpandeli et al., 2018; Nhamo et al., 2018; Terrapon-Pfaff et al., 2018). Therefore, what remains with the WEF nexus are methods to evaluate synergies and trade-offs in an integrated way, and decision support tools that can be used to prevent conflicts, reduce investment risks and maximise economic returns (Howells et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017). As observed by Albrecht et al. (2018), existing tools lack these main attributes and most of them either remain theoretical or maintain a sectoral approach to resource management. Previously developed WEF nexus analytical tools have not been well-adopted as they are generally complex or difficult to replicate, and sector integration to establish the linkages among the sectors is not clear or is not established at all (Albrecht et al., 2018; McGrane et al., 2018). For the WEF nexus to be a true nexus, it needs a decision support tool that assesses the three sectors together, enabling the quantification of cross-sectoral interlinkages and visualisation of the imbalances, and capable of assessing resources development and utilisation in a holistic way (Mabrey and Vittorio, 2018; McGrane et al., 2018).

One way to evaluate resource management is through sustainability indicators that are expressed through composite indices (Dizdaroglu, 2017; Farinha et al., 2019). Sustainability indicators convey information on the performance and current status of resources at a given spatial scale (Bell and Morse, 2018; Singh et al., 2012; Warhurst, 2002), and for quantifying the state or trend of resource utilisation (Garnåsjordet et al., 2012; Ozturk, 2017). Sustainability indicators can be used individually or can be combined, where all individual indicator scores are integrated into one composite index (Maxwell et al., 2013; Schernewski et al., 2014). WEF nexus sustainability indicators provide decision makers with an important analytical framework that indicates the state of WEF resources, in terms of short, medium and long-term perspectives. As important components of the WEF nexus, sustainability indicators provide the needed parameters to balance resource planning, governance, and technology development to enhance human wellbeing, now and in the future (Bizikova et al., 2013; Ozturk, 2015). They are measurable parameters that indicate the performance of ecological, social, or economic systems (Shilling et al., 2013), hence their relationship with SDGs progress assessment. They connect statements of intent (objectives) and measurable aspects of natural and human systems (Fiksel et al., 2012).

Sustainability refers to the long-term stability of the economy and environment, achievable through integrating and acknowledging economic, environmental and social concerns throughout the decision-making process (Brundtland Commission, 1987; Emas, 2015). The essence of sustainable development is to balance different and competing necessities against an awareness of the environment, social and economic limitations faced by humankind (Meadows et al., 1972). Sustainability is, therefore, a complex and multidimensional concept, which includes efficiency, equity and intergenerational equity based on socio-economic and environmental aspects (Ciegis et al., 2009a). A sustainable system is one providing for the economy, the ecosystem, and social well-being and equity at all times (Breslow et al., 2017; Shilling et al., 2013). Thus, sustainability indicators are simplified decision support tools that aim to enhance the understanding of complex interrelationships among resources, converting those relationships into simple formulations that make assessments easier (Ciegis et al., 2009b). Thus, sustainability indicators are essential tools in modelling the WEF nexus as it intends to balance cross-sectoral resource planning and management (Mpandeli et al., 2018; Nhamo et al., 2018). This study defined WEF nexus indicators and applied the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to develop composite indices to mathematically establish numerical relationships among water, energy, and agriculture (agriculture being a proxy for food) resources, using South Africa as a case study. The model was then used to assess progress towards SDGs in South Africa.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Criteria for selecting WEF nexus sustainability indicators

The essence of the WEF nexus is to ensure the security of WEF resources through sustainable and integrated and cross-sectoral resource management. The basis of the approach is to ensure that any planned developments in any one sector should only be implemented after considering the impacts on other sectors (Mpandeli et al., 2018; Nhamo et al., 2018). An integrated assessment of WEF resources was achieved by firstly defining WEF security-related sustainability indicators, a set of measurable parameters that assess resource management at a given time and spatial scale (Bizikova et al., 2013; McLaughlin and Kinzelbach, 2015; Rasul, 2016; Speirs et al., 2015). The indicators are directly related to the drivers of resource security that include availability, accessibility, self-sufficiency, and productivity (Flammini et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2012), as shown in Table 1. Any other indicators that do not relate to these drivers were excluded from the list of WEF nexus indicators. The same drivers are also crucial in sustainability dimensions that include economic (increasing resource efficiency), social (accelerating access for all), and environmental (investing to sustain ecosystem services) (Rasul and Sharma, 2016). Thus, the main criteria used to define WEF nexus indicators were (i) any indicators available in literature that referred to water, energy and food resources, but (ii) were not directly linked to the nexus and its drivers, or (iii) were not key to WEF securities, were excluded from the list of WEF nexus indicators. However, some of the indicators can be adapted depending on each particular situation.

Table 1. Sustainability indicators and pillars for WEF nexus sectors.

| Sector | Indicator | Units | Pillars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Proportion of available freshwater resources per capita (availability) | m3/capita | Affordability |

| Proportion of crops produced per unit of water used (productivity) | $/m3 | Stability Safety | |

| Energy | Proportion of the population with access to electricity (accessibility) | % | Reliability |

| Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP (productivity) | MJ/GDP | Sufficiency Energy type |

|

| Food | Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population (self-sufficiency) | % | Accessibility |

| Proportion of sustainable agricultural production per unit area (cereal productivity) | kg/ha | Availability Affordability Stability |

Within each WEF nexus sustainability indicator, there are pillars that sustain the indicators. The pillars contribute significantly when establishing numerical relationships among indicators but fall short of being WEF nexus indicators according to the set criteria. Each WEF nexus sector has its set of indicators and pillars that are relevant for establishing quantitative relationships among the sectors. For example, a country may have abundant water resources per capita (availability), but may not be affordable for the majority of the population or accessible to many as supplies from the sources may not be stable due to systems failures (stability) (Cosgrove and Loucks, 2015; Hinrichsen and Tacio, 2002). Furthermore, a country may have enough energy supplies, but they are not reliable, or the energy type is condemned. All these factors are considered when establishing indicator relationships.

2.2. Definitions for WEF nexus sustainability indicators

The WEF nexus indicators and pillars (Table 1) can be adapted and used at any scale. They are the same indicators for related SDGs 2, 6 and 7 and address issues related to the security of water, energy, and food (https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/). Country baseline data for the indicators can be obtained from World Bank indicators or from national statistical agents. The WEF nexus sustainability indicators (Table 1) are defined as follows:

-

i

The proportion of available freshwater resources per capita (m3/capita). This indicator refers to the estimate of the total available freshwater water resources per person in a country, thus termed water availability (Damkjaer and Taylor, 2017).

-

ii

The proportion of crops produced per unit of water used ($/m3). This indicator refers to a measure of output from an agricultural system in relation to the water it consumes and thus called water productivity (Kijne et al., 2003). In this study, we used the economic water productivity which is expressed in US$ per unit of water consumed (Nhamo et al., 2016).

-

iii

The proportion of the population with access to electricity is expressed as a percentage (%) of the total population with electricity access and is referred to as energy accessibility (Rao and Pachauri, 2017).

-

iv

Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP (MJ/GDP). Energy intensity is defined as the energy supplied to the economy pet unit value of economic output and is termed as energy productivity (King, 2010).

-

v

Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population. This is the percentage (%) of individuals in the population who have experienced food insecurity at moderate or severe levels during the reference year and is termed as food self-sufficiency (Pérez-Escamilla and Segall-Corrêa, 2008).

-

vi

The proportion of sustainable agricultural production per unit area (kg/ha). This is the ratio between the area under productive and sustainable agriculture and the agricultural land area (Reytar et al., 2014). Only cereals were considered in this study, hence the indicator is referred to as cereal productivity. Sustainable agriculture refers to an agricultural production system that produces food in a way that protects and improves natural environments, and the social and economic conditions of farmers and workers, while at the same time safeguarding the local communities, the health, and welfare of all species within the farming system (Bowler, 2002).

2.3. Tools to integrate WEF nexus indicators

The main approach used to develop the WEF nexus analytical model is the multi-criteria-decision making (MCDM), a tool for structuring and solving complex decisions and planning problems that involve multiple criteria (Kumar et al., 2017). The MCDM is a cross-sectoral planning tool to overcome the increasing demand for essential resources with a vision of sustainable development (Siksnelyte et al., 2018). With the increasing complexity and multiplicity of managing resources, the sectoral analysis is no longer relevant. The MCDM was preferred as it solves socio-economic, environmental, technical and institutional barriers in resources management in a holistic way (Kiker et al., 2005).

The AHP, an MCDM method was used to integrate and establish numerical relationships among WEF sectors (Saaty, 1977; Triantaphyllou and Mann, 1995). The AHP, introduced by Saaty (1987), is a theory of measurement to derive ratio scales from both discrete and continuous paired comparisons to help decision-makers to set priorities and make the best decisions. The AHP comparison matrix is determined by comparing two indicators at a time using, Saaty’s scale, which ranges between 1/9 and 9 (Saaty, 1977). A range between 1 and 9 represents an important relationship, and a range between 1/3 and 1/9 represents an insignificant relationship (Supplementary Material 1). A rating of 9 indicates that in relation to the column factor, the row factor is 9 times more important. Conversely, a rating of 1/9 indicates that relative to the column indicator, the row indicator is 1/9 less important. In cases where the column and row indicators are equally important, they have a rating of 1. The method has been successfully applied in recent years (Cabrera-Barona and Ghorbanzadeh, 2018; Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2018; Yavuz, 2015). In the case of the WEF nexus, the weight for an indicator in the pairwise comparison is determined by the influence of that indicator in relation to the other indicators. For example, if the total renewable water resources per capita is 855 m3/year, the pairwise comparison would determine how other factors like water scarcity and agriculture production influence this value. Thus, the degree of influence of one indicator on the other is based on available baseline data, which is obtainable from national statistical agents, World Bank indicators, Aquastat or any other recognised database. The weight for the indicators is also based on expert opinion or from literature (Flammini et al., 2017). The integrated statistical information provides the baseline to establish the numerical relationship among indicators.

2.4. An overview of the AHP in integrating different indicators

Of the many MCDM methods available [Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), Simple Additive Weighting (SAW), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT), Elimination and Choice Expressing the Reality (ELECTRE), Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Of Evaluations (PROMETHEE), etc.], the AHP remains the most used and widely accepted as demonstrated by comparative studies on MCDM methods (de FSM Russo and Camanho, 2015; Tscheikner-Gratl et al., 2017; Velasquez and Hester, 2013). Some of the methods like the TOPSIS actually apply the AHP in their applications (Tscheikner-Gratl et al., 2017). The AHP is used in many fields and various specialties such as Environmental Sustainability, Economic Wellbeing, Sociology, Programming, Suitability Mapping, Resource Allocation, Strategic Planning, and Project/Risk Management to aggregate distinct indicators and monitor performance, for benchmarking, policy analysis and decision-making (Cherchye and Kuosmanen, 2004; Dizdaroglu, 2017; Forman and Gass, 2001; Zanella et al., 2013). These fields, and more recently WEF nexus, cannot be measured using a single indicator but through a set of distinct indicators that need to be standardised and normalised.

The advantages of using the AHP over other methods are its usefulness in the hierarchical problem presentation, the appeal of pairwise comparisons in preference elicitation and its flexibility and ability to check inconsistencies (Emrouznejad and Marra, 2017; Saaty, 2008; Schmidt et al., 2015; Tscheikner-Gratl et al., 2017). Despite the subjective judgments in an AHP, results remain vital for policy evaluation and performance assessment as the method captures both subjective and objective evaluation measures (Cherchye et al., 2007). This uncertainty is dealt with by engaging experts and the use of reliable baseline data in establishing relationships among indicators (Brunelli, 2014; Zhou et al., 2007). However, studies have shown that the AHP accuracy can be compromised, if there are too many criteria or factors (more than 9) used during the pairwise comparison (Görener, 2012; Tscheikner-Gratl et al., 2017; Widianta et al., 2018).

2.5. Calculation and normalisation of indices

Indicators and pillars (Table 1) are important for establishing numerical relationships among indicators through a comparison matrix by indexing the indicators. Each indicator is compared and related to other indicators and is assigned a value (index) according to Saaty’s AHP pairwise comparisons matrix (PCM) and then normalised (Saaty, 1987, 1977). Through the PCM, the AHP calculates the index for each indicator by taking the eigenvector (a vector whose direction does not change even if a linear transformation is applied) corresponding to the largest eigenvalue (the size of the eigenvector) of the matrix and then normalising the sum of the components (Stewart and Thomas, 2006). The eigenvalue method synthesises a pairwise comparison matrix A, to obtain a priority weight vector for several decision criteria and alternatives. Here an eigenvector of matrix A is used for the priority weight vector. In eigenvector method, the priority weight vector is set to the right principal eigenvector w of the pairwise comparison matrix A. Therefore, the eigenvector method is to find the maximum value λ and its corresponding vector w such that (Saaty, 1990):

| (1) |

The overall importance of each indicator is then determined. The basic input is the pairwise matrix, A, of n criteria, established based on of Saaty’s scaling ratios, which is of the order (n x n) (Rao et al., 1991). A is a matrix with elements aji. The matrix generally has the property of reciprocity, expressed mathematically as:

| (2) |

After generating this matrix, it is then normalized as a matrix B, in which B is the normalized matrix of A, with elements bji and expressed as:

| (3) |

Each weight value wi is computed as:

| (4) |

The integrated WEF nexus index is then calculated as a median of all the indices of indicators. The integrated composite index represents the overall performance of resource development, utilisation, and management as seen together.

2.6. Determining the consistency of the pairwise comparison matrix

In an AHP method, the derived indices should always be consistent at an acceptable ratio of less than 0.1 or 10 % (the allowable consistency). The consistency ratio (CR) indicates the likelihood that the matrix judgments were generated randomly and are consistent (Alonso and Lamata, 2006). Higher CR values indicate that the comparisons are less consistent, while smaller values indicate that comparisons are more consistent. When CRs are above 0.1, the pair-wise comparison is not consistent and should be revaluated (Saaty, 1977). The CR is calculated as (Teknomo, 2006):

| (5) |

where: CI is the consistency index, RI is the random index, the average of the resulting consistency index depending on the order of the matrix given by Saaty (Saaty, 1977). CI is calculated as:

| (6) |

where: λ is the principal eigenvalue (shaded section of Table 4), and n is the number of criteria or sub-criteria in each pairwise comparison matrix.

Table 4. Normalised pairwise comparison matrix and composite indices.

| Indicator | Normalised pairwise comparison matrix | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water availability | Water productivity | Energy accessibility | Energy productivity | Food self-sufficiency | Crop productivity | Indices | |

| Water availability | 0.100 | 0.214 | 0.071 | 0.051 | 0.091 | 0.065 | 0.099 |

| Water productivity | 0.100 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 0.459 | 0.272 | 0.065 | 0.221 |

| Energy accessibility | 0.100 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.153 | 0.054 | 0.022 | 0.079 |

| Energy productivity | 0.300 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.153 | 0.272 | 0.326 | 0.199 |

| Food self-sufficiency | 0.300 | 0.214 | 0.357 | 0.153 | 0.272 | 0.457 | 0.292 |

| Crop productivity | 0.100 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.065 | 0.111 |

| CR = 0.01 | Σ = 1 | ||||||

| Composite WEF nexus index (weighted average) | 0.203 | ||||||

2.7. Application of the model: South Africa Case Study

South Africa is used as a case study to apply the developed WEF nexus analytical model. The data used is specifically for South Africa and the results thereof. However, the methodology can be replicated anywhere and at any scale, depending on data availability.

2.7.1. Pairwise comparison matrix for WEF nexus indicators for South Africa

The PCM to determine the relationship among WEF nexus components for South Africa is given in Table 3. The diagonal elements are the values of unity (i.e., when an indicator is compared with itself the relationship is 1). Since the matrix is also symmetrical, only the upper half of the triangle (yellow shaded) is filled in and the remaining cells are reciprocals of the lower triangle. The relationships are established using a scale between 1/9 to 9, and the overview of the country indicator status according to a particular year, in this case for 2018 as shown in Table 2 in relation to the classification categories given in Table 5, respectively. Thus, the indicator values given in Table 2 provide the basis to classify the indicators. There is a close relationship between Tables 2 and 5 when determining the coefficients given in Table 3.

Table 3. Pairwise comparison matrix for WEF nexus indicators.

| Indicator | Pairwise comparison matrix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water availability | Water productivity | Energy accessibility | Energy productivity | Food self-sufficiency | Cereal productivity | |

| Water availability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1 |

| Water productivity | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Energy accessibility | 1 | 1/3 | 1 | 1 | 1/5 | 1/3 |

| Energy productivity | 3 | 1/3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Food self-sufficiency | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Cereal productivity | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1/5 | 1/7 | 1 |

Table 2. Overview of the WEF nexus indicators for South Africa.

Source: World Bank Indicators

| WEF nexus | Indicator | Status 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Water | Proportion of available freshwater resources per capita (availability) | 821.42 m3/cap |

| Proportion of crops produced per unit of water used (water productivity) | 26.2 $/m3 | |

| 2. Energy | Proportion of population with access to electricity (accessibility) | 84.2 % |

| Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP (productivity) | 8.7 (MJ/GDP) | |

| 3. Food | Prevalence of moderate/severe food insecurity in the population (self-sufficiency) | 6.1 % |

| Proportion of sustainable agricultural production per unit area (cereal productivity) | 3.8 kg/ha |

Table 5. WEF nexus indicators performance classification categories.

| Indicator | Unsustainable | Marginally sustainable | Moderately sustainable | Highly sustainable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water availability (m3/per capita) | < 1 700 | 1 700−6 000 | 6 001–15 000 | > 15 000 |

| Water productivity (US$/m3) | < 10 | 10 - 20 | 21 - 100 | > 100 |

| Food self-sufficiency (% of pop) | > 30 | 15 - 29 | 5 - 14 | < 5 |

| Cereal productivity (kg/ha) | < 500 | 501 - 2 000 | 2 001–4 000 | > 4 000 |

| Energy accessibility (% of pop) | < 20 | 21 - 50 | 51 - 89 | 90 - 100 |

| Energy productivity (MJ/GDP) | > 9 | 6 - 9 | 3 - 5 | < 3 |

| WEF nexus composite index | 0 - 09 | 0.1 - 0.2 | 0.3 - 0.6 | 0.7 - 1 |

2.7.2. Normalised pairwise comparison matrix for WEF nexus indicators

The normalisation of the PCM for the indicators (Table 3) is shown in Table 4 where each index is calculated using Eqs 3 and 4, respectively. The sum of indices should always be 1 (as shown in Table 4). The summing of the indices to 1 shows that the indicators are now numerically linked or related and can now be analysed together as a whole for sustainable development. The CR for the normalised pairwise matrix is 0.01, which is within the acceptable range. The weighted average of the calculated indices is the WEF nexus integrated index, which is classified according to the categories given using Table 5. The indices are ranked according to their weight, the highest being ranked 6 and the lowest-ranked 1 in order to calculate the weighted average. The integrated WEF nexus composite index for South Africa was calculated at 0.203, classifying the country into a marginally sustainable category (Table 5).

The indices for the indicators vary between 0 and 1, where 0 represents unsustainable resource management and 1, highly sustainable resource management (Table 5). Some countries could be falling in a highly sustainable category, but 1 is almost impossible to achieve.

2.8. Classification categories for indicators and the WEF nexus integrated index

Table 5 shows the classification categories for the indicators as well as the WEF nexus integrated index for ranking resource use and performance. Categorising indicators form the basis to establish the numerical relationship between the indicators by first classifying an indicator according to given classification criteria or standard. The classification is useful especially when scaling the indicators. It helps in determining the intensity of the importance of an indicator.

2.9. Conceptual framework for developing WEF nexus analytical model

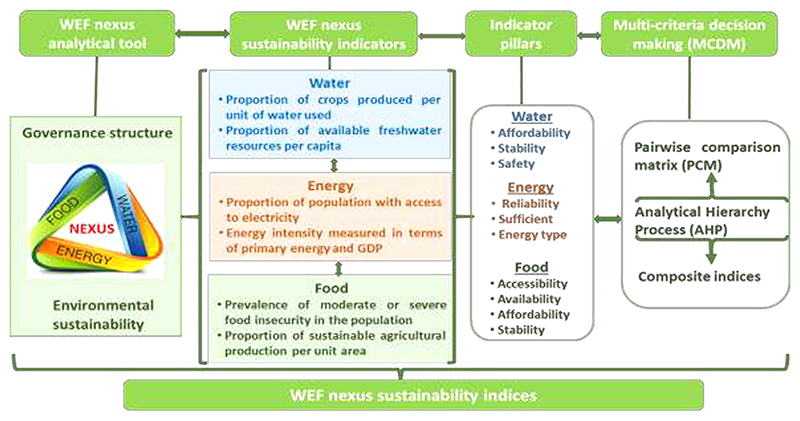

Fig. 1 is a graphical representation of the conceptual outline used to develop the WEF nexus analytical model. The initial step was to define the sustainability indicators for each WEF nexus sector (water, energy, and food). The indicators were framed in a way that reflects the securities of water, energy and food from a nexus perspective (Ericksen, 2008; Forsström et al., 2011; IEA, 2008; Qiu et al., 2007; Rao and Rogers, 2006; Shilling et al., 2013; Zhen and Routray, 2003). However, the indicators can be adapted to a particular situation, as they do not always apply in every situation. For example, the indicator on ‘proportion of sustainable agricultural production per unit area’ does not always apply in all situations as countries like Japan and Italy import between 50 % and 70 % of their food requirements because of limited land, but have enough food (Clapp, 2017; Ortiz-Ospina et al., 2018).

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework to develop WEF nexus indicators and indices.

Within each indicator, there are defined pillars that determine the performance of an indicator. Indicators and pillars are necessary for establishing numerical relationships among sectors by means of indices. The second step involved determining composite indices for the indicators, establishing quantitative relationships among the indicators, using the AHP as an MCDM. The AHP was used to normalise, standardise and integrate distinct data from the indicators, and to compute a composite index or a set of indices through the (PCM).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Performance of WEF nexus indicators in South Africa

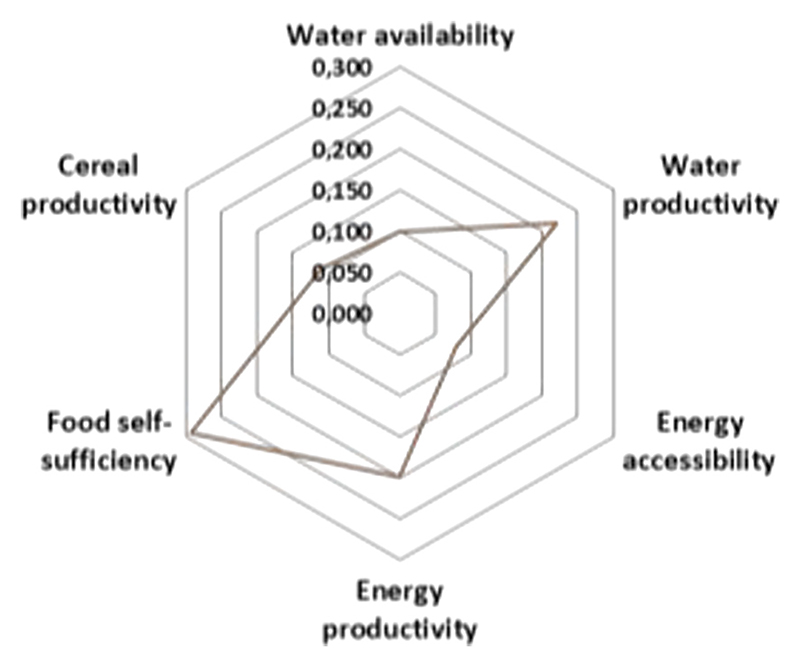

The calculated indices for the WEF nexus (Table 4) were used to construct a spider graph that provides a clear visualisation of the interactions, interconnectedness, and interdependences among sectors as seen together (Fig. 2). The spider graph provides a synopsis of the current outlook, general performance and quantitative relationships of WEF sectors in South Africa, based on the results of the assessment. The further the distance of the indicator from the centre of the axis, the greater the level of sustainable development or the closer it is to the axis the greater the level of unsustainability. Thus, for the periods assessed, the results showed that there was an imbalance in resource planning, allocation, utilisation, and management.

Fig. 2. Performance of WEF nexus indicators in South Africa in 2018.

In the case of South Africa, there was an evident focus on food security (food self-sufficiency) and water productivity at the expense of other sectors. While energy productivity is fairly well managed, energy accessibility was the worst performing indicator. Although a lot has been done in increasing access to energy to 84.2 % of the population, pillars like reliability and source or type of energy used also come into play. In this example, it was considered that 86 % of South Africa’s energy comes from coal (Pretorius et al., 2015), which is regarded as environmentally unsustainable and uses a lot of water. Coal releases a considerable amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (methane) into the atmosphere, which contributes to global warming (Weisser, 2007). Another area that needs to be improved is water management to ensure water security in a country where annual water availability per capita is only 821.42 m3, which is already unsustainable according to the classification given in Table 6. Improving water management, especially agricultural water management has potential to free water for other uses as agriculture currently consumes about 60 % of available water resources (Pereira and Drimie, 2016). Unsustainable water availability indicates the degree of water scarcity in South Africa. The country is classified as water-scarce and it is among the thirty driest countries in the world (Muller et al., 2009). Thus, the country’s marginal performance in water availability is greatly influenced by pillars such as stability and safety that were factored in during the pairwise comparison. Water infrastructure could be there to reach many households with tapped water, but supply is not guaranteed due to water scarcity challenges. The challenge of water scarcity has promoted the country to use water resources optimally as water productivity is the second-best performing indicator and is classified as moderately sustainable producing US$26.2/m3 (Tables 2 and 5).

Table 6. WEF nexus indicators and pillars, and the linked SDG indicators.

| Sector | WEF nexus Indicator | Related SDG indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Water | Proportion of crops/energy produced per unit of water used (productivity) | 6.4.1: Change in water-use efficiency over time |

| Proportion of available freshwater resources per capita (availability) | 6.4.2: Freshwater withdrawal as a proportion of available freshwater resources | |

| Energy | Proportion of population with access to electricity (accessibility) | 7.1.1: Proportion of population with access to electricity |

| Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP (productivity) | 7.3.1: Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP | |

| Food | Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population (self-sufficiency) | 2.1.2: Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population |

| Proportion of sustainable agricultural production per unit area (cereal productivity) | 2.4.1: Proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture |

However, for balanced and sustainable resource development, utilisation and management, the country should target to make all sectors reach the highest index achieved in food self-sufficiency of 0.28 and attain a circular shape of the amoeba in the spider graph; otherwise, the current sectoral approach will continue creating an imbalance in the economy and retard development. Achieving a circular shape of the amoeba at an index of 0.28 would only indicate a balanced resource management, but it would still be regarded as marginally unsustainable. A balanced resource management shows that resources are being developed and utilised holistically to achieve sustainability. A deformed shape of the amoeba usually results from a sectoral approach in resources management, which is the current situation for South Africa and the region (Mabhaudhi et al., 2016; Nhamo et al., 2018). The developed WEF nexus analytical framework provides evidence to decision-makers on how to integrate strategies aimed at adapting to cross-sectoral approaches and translate to savings from costs associated with duplication of developmental projects, increased efficiencies due to streamlining of activities, and higher likelihood of success due to consideration of WEF nexus trade-offs and synergies (Mpandeli et al., 2018).

The amoeba (the centrepiece) highlights a country’s strengths, as well as priority areas needing intervention. The WEF nexus analytical model is, therefore, a decision support tool for tracking resource utilisation and performance, vividly capturing the interactions among sectors. The model differs from previously developed methods in that it portrays the polycentric nature of the WEF nexus, analysing sectors in a holistic way, viewing them in equal terms, as a whole, and in an integrated manner, providing decision support to policy and resource managers. The approach links resource management and governance outcomes for sustainable development, which underlines the value of the nexus approach. These niches make the WEF nexus applicable in many fields of study, including assessing SDGs performance. The analytical model can be used to set targets to meet the desired balance in resource development in line with relevant SDGs and country programmes over a certain period. In the presented scenario for South Africa, interventions could be to improve the provision of safe and reliable water, clean and safe energy and improve crop productivity. Possible intervention scenarios are weighed to assess their impacts before implementation. For example, South Africa aims to increase the area under irrigation by 149 000 ha in order to ensure food security (RSA, 2011). However, before implementing such initiatives, decision-makers should consider the impacts on water and energy by analysing all possibilities through the WEF nexus analytical framework.

3.2. Application of the model to assess progress towards SDGs

The capability of the WEF nexus to establish integrated numerical relationships on resource management and providing an overview of the status of resource sustainability over time facilitates an assessment of the progress towards SDGs. The WEF nexus indicators are directly linked to SDG indicators such as (a) direct measure of available water resources, (b) direct measure of food security, and (c) direct measure of energy accessibility as shown in Table 6. These refer to indicators falling under SDGs 2, 6 and 7. The linkages between WEF nexus and SDGs indicators allowed the application of the model to assess progress towards SDGs between 2015 and 2018 in South Africa.

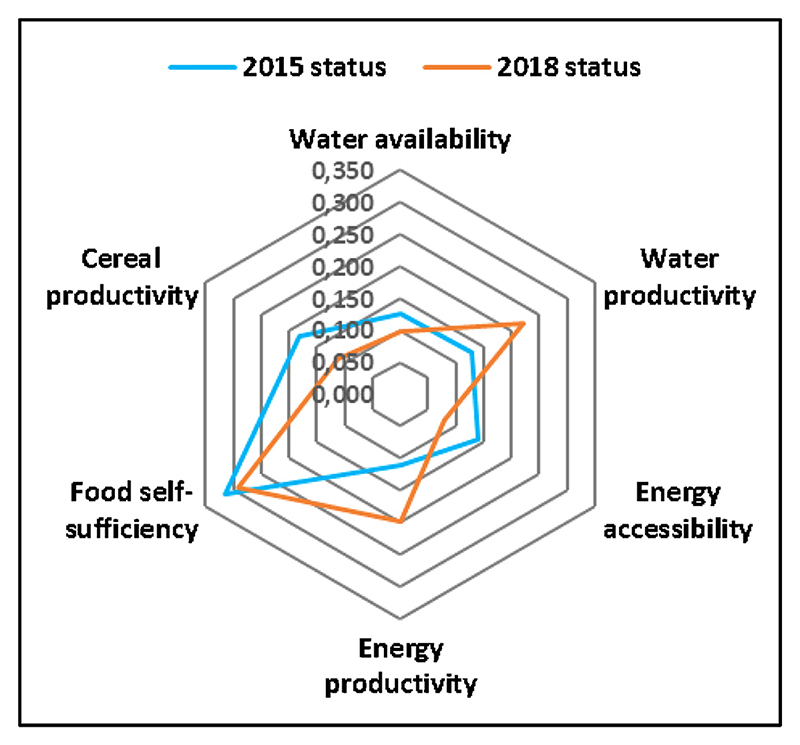

After estimating the indices for 2018, the same methodology was applied to estimate the indices for 2015. The PCM and normalised indices, as well as the CR for 2015, are given in Supplementary Material 1. Composite indices for each of the indicators from the normalised PCM for 2015 and 2018 for South Africa are summarised in Table 7, as well as WEF nexus integrated indices for each of the reference years as 0.147 and 0.203, respectively. Both integrated and individual indices between the reference years are compared to assess the progress and the sustainability in resource management towards the SDGs. There is a noted overall improvement in resources management, and progress in SDG implementation (an increase of 38 % between 2015 and 2018), however, the level of sustainability remains marginal, according to the classification given in Table 5. The country should thrive to achieve the highest achievable level of sustainability to ensure resource security.

Table 7. WEF nexus composite indices for South Africa.

| Indicator | Composite indices | |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2018 | |

| Water availability | 0.126 | 0.099 |

| Water productivity | 0.128 | 0.221 |

| Energy accessibility | 0.141 | 0.079 |

| Energy productivity | 0.111 | 0.199 |

| Food self-sufficiency | 0.314 | 0.292 |

| Cereal productivity | 0.180 | 0.111 |

| WEF integrated index | 0.155 | 0.203 |

The integrated indices for the respective years are low, exposing the unsustainability in resource management in South Africa. The numerical relationships and the changes that took place in the progress towards SDGs between 2015 and 2018 are shown as a spider graph (Fig. 3). The irregular shapes of the spider graphs for both reference years are an indication that South Africa is still a long way from achieving sustainability in resource use and management. The irregular shapes resemble an imbalance in resource planning, allocation, utilisation and management, which promotes inequality, exacerbates poverty, and triggers resource insecurity.

Fig. 3.

An overview of the progress in SDGs implementation in 2015 and 2018 in South Africa. The deformed shape of the numerical relationship indicates the unsustainability of resource management.

In both reference years (2015 and 2018), South Africa focused more on food security (food self-sufficiency), and in 2018 the country also improved on water productivity (Fig.3). However, these improvements are achieved at the expense of other indicators as some of the indicators contracted, giving the irregular shape to the graphs. Thus, at a time when food security and water productivity were improving, the performance of the other indicators was shrinking (Fig. 3), an indication of an unbalanced resource management, which is the main cause of unsustainability. Without compromising food security and the advances made in water productivity, the country should also consider allocating more resources to improving the other indicators in an integrated manner. A balanced economy and sustainable resource management are evidenced when the graphs (Fig. 3) become circular, unlike the present situation where it is irregular.

The improved water productivity index in 2018 could have been a result of the measures that were affected after the severe drought that occurred during the 2015/16 rainy season (Nhamo et al., 2019). Also, the improvement in energy productivity in the same year could have been driven by the energy crisis that was experienced in 2017, which, however, also resulted in lower energy accessibility as compared to 2015 (decreased by 1.3 % between 2015 and 2018). Thus, “the good performance” in food self-sufficiency and water and energy productivity was mainly informed by prevailing challenges. However, such short-term interventions or coping strategies aften results in transferring challenges from one sector to others, thus creating trade-offs with long-term negative implications. Without informed interventions, sustainability is difficult to achieve, progress made towards long-term adaptation and resilience-building is compromised, and resource management unsustainable.

4. Way forward and recommendations

The developed WEF nexus analytical model has managed to establish relationships among different, but interlinked WEF sectors, moving the WEF nexus approach from a theoretical framework to an analytical and practical one that provides real-world solutions. The analytical model has enabled the evaluation and management of synergies and trade-offs in resource planning and utilisation, which previous tools had failed to achieve. Besides their failure to establish numerical relationships among the WEF sectors, previous models had either remained theoretical or had maintained a sectoral approach to resource management, rendering them inappropriate to offer any nexus evidence for the operationalisation of the WEF nexus. The developed model has simplified human understanding of the complex interrelationships among resources, by converting those relationships into a simple formulation that makes assessments easier.

By illustrating the numerical relationships among sectors through a spider graph reveals a country’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as indicating priority areas for intervention, making the WEF nexus a valuable adaptation and decision support tool. As different scenarios can be developed from the information that is derived from the model, the WEF nexus has, thus, become important for tracking resource utilisation and management at a given time. The WEF nexus has evolved into a multi-purpose and polycentric decision support tool for simplifying and framing complex interactions between socio-economic and environmental concerns. However, further research is needed to develop interventional scenarios that inform decision-makers on achieving a circular spider graph and a balanced resource management for sustainable development.

As already alluded to, the model has been designed to simplify and interpret the complex interactions and relationships among the WEF resources, converting those complexities into simple formulations that can be understood by stakeholders for easy application and assessment at any spatial scale. However, there are some considerations to make before applying the model at different scales or different purposes, which include:

-

a

The indicators that were used in this study are those that measure the security of WEF resources at the country level. Although these indicators are valid for this study and at the country level, they can be adjusted for other purposes, but using the same procedure. The focus on the security of the three WEF resources was based on southern Africa regional priorities, but priorities differ across spatial scales and context, thus the indicators may be adjusted to suit each context. For example, at the household level, different indicators, other than the ones used here, can be used depending on the objectives.

-

b

He model has been designed in such a way that a WEF nexus integrated index of 1 is almost impossible to achieve, even for individual indicators. This could be true in that optimal sustainable development is difficult to achieve and no society can claim to be using its resources optimally.

4.1. Limitations of the model

The developed model is still in its infancy and can only be improved with time as it is applied at different spatial scales. One area that would strengthen the model is the development of interventional scenarios that would assist in balancing the spider graph and drive towards sustainability in resource management. As a new model, the following factors have been identified as the major limitations of the model:

-

a

A major weakness of the model is embedded in the use of the AHP, particularly its subjective judgments during the pairwise comparison matrix. Nevertheless, the developed analytical model remains vital for policy evaluation and performance assessment as the method captures both subjective and objective evaluation measures by using reliable baseline data during the pairwise comparison matrix categorisations and by engaging field experts. In addition, the calculation of the consistency ratio with the AHP framework strengthens the integration of expert opinion with the available data. The hierarchical problem presentation of the AHP qualifies it in WEF nexus modelling as it ranks resources according to how they are planned and managed, linking them to each other.

-

b

Although the AHP remains as the most used MCDM, consistency is very difficult to achieve where there are more than 9 criteria/indicators under consideration (Fortunet et al., 2018; Pamučar et al., 2018). Yet, its ability to measure consistency is one of the factors that gives the AHP an age over the other methods.

-

c

At this stage, the model is just indicative, only showing a country’s status in resource planning, use and management, and identifying areas of immediate interventions, but without offering solutions to achieve sustainability in resource use. There is, therefore, a need to develop interventional scenarios to achieve a circular shape of the spider graph.

-

d

The current model does not consider all available indicators as it only focuses on indicators that are related to the security of water, energy and food resources. However, the model is flexible and can be adjusted and replicated to meet every situation.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a WEF nexus analytical model, firstly by defining WEF nexus indicators, and then calculating the indicator composite indices for South Africa. The model was then used to assess progress towards related SDGs providing an overview of the changes taking place over time. Although the procedure uses data for South Africa, it can be replicated anywhere, and at any spatial scale. Thus, the procedure presents an inclusive and multi-spatial scale analytical framework that defines and quantifies the interconnectivity of WEF sectors. The composite indices assess the interactions between the natural environment and the biosphere in a given context and at any scale, and the methodology presents the WEF nexus as a unique tool to (a) quantitatively assess the cross-sectoral linkages among resources and indicate performance of resource utilisation and management, (b) leverage an understanding of WEF linkages to promote coherence in policy-making and enhance sustainable development, (c) guide and promote cross-sectoral collaboration, and (d) assess progress towards SDGs. The indices provide a clear overview of the level of interactions, inter-relationships, and inter-connectedness among sectors. The relationships are demonstrated in the form of interdependencies, constraints, synergies and trade-offs that arise when changes in one area affect others, and they are viewed as either positive or negative (sustainable or unsustainable). When shown through a spider graph, the indices indicate areas needing immediate attention to create a balance in resource utilisation, increase efficiency and productivity, improve livelihoods and build resilience. The WEF nexus analytical framework simplifies the understanding of the complex and dynamic interlinkages between the issues related to the securities of water, energy and food and it provides evidence for decision-making and policy formulation. The approach facilitates analyses that inform policy interventions with regards to testing the sustainability of related policies (e.g. for South Africa this would include policies such as the Draft Climate Smart Agriculture Strategy, National Adaptation Strategy and the Climate Change Bill). The composite indices are an entry point and/or point of departure to assess available data and determine what interventions to focus on and derive solutions to mitigate negative trade-offs on economic development. The integrated WEF nexus indices, thus, provide an overview on how to balance and prioritise different components of complex systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is as a result of the WEF nexus research initiative by the Water Research Commission’s (WRC) WEF nexus Lighthouse and was funded through the WRC’s Research Development Branch, and the Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems (SHEFS) programme supported by the Wellcome Trust’s Our Planet, Our Health programme [grant number: 205200/Z/16/Z].

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Luxon Nhamo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation. Sylvester Mpandeli: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Data curation. Chris Dickens: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Charles Nhemachena: Data curation, Validation, Writing - original draft. Aidan Senzanje: Data curation, Writing - original draft. Dhesigen Naidoo: Supervision, Validation. Stanley Liphadzi: Supervision, Writing - original draft, Validation. Albert T. Modi: Supervision, Writing - original draft, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Albrecht TR, Crootof A, Scott CA. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: a systematic review of methods for nexus assessment. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13:043002 [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JA, Lamata MT. Consistency in the analytic hierarchy process: a new approach. Int J Uncertain Fuzziness Knowl Syst. 2006;14:445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Morse S. Sustainability Indicators Past and Present: What Next? Sustainability. 2018;10:1688 [Google Scholar]

- Benson D, Gain AK, Rouillard JJ. Water governance in a comparative perspective: From IWRM to a’nexus’ approach? Water Alternatives. 2015;8 [Google Scholar]

- Bizikova L, Roy D, Swanson D, Venema HD, McCandless M. The Water-energy-food Security Nexus: Towards a Practical Planning and Decision-support Framework for Landscape Investment and Risk Management. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler I. Developing sustainable agriculture. Geography. 2002:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow SJ, Allen M, Holstein D, Sojka B, Barnea R, Basurto X, Carothers C, Charnley S, Coulthard S, Dolšak N. Evaluating indicators of human well-being for ecosystem-based management. Ecosyst Health Sustain. 2017;3:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future; Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli M. Introduction to the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Alto, Finland: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Barona P, Ghorbanzadeh O. Comparing classic and interval analytical hierarchy process methodologies for measuring area-level deprivation to analyze health inequalities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:140. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, Krzywoszynska A. Anatomy of a buzzword: the emergence of ‘the water-energy-food nexus’ in UK natural resource debates. Environ Sci Policy. 2016;64:164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchye L, Kuosmanen T. Benchmarking Sustainable Development: a Synthetic Meta-index Approach Research Paper, UNU-WIDER. United Nations University (UNU); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchye L, Moesen W, Rogge N, Van Puyenbroeck T. An introduction to ‘benefit of the doubt’composite indicators. Soc Indic Res. 2007;82:111–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ciegis R, Ramanauskiene J, Martinkus B. The concept of sustainable development and its use for sustainability scenarios. Eng Econ. 2009a;62 [Google Scholar]

- Ciegis R, Ramanauskiene J, Startiene G. Theoretical reasoning of the use of indicators and indices for sustainable development assessment. Eng Econ. 2009b;63 [Google Scholar]

- Clapp J. Food self-sufficiency: making sense of it, and when it makes sense. Food Policy. 2017;66:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove WJ, Loucks DP. Water management: current and future challenges and research directions. Water Resour Res. 2015;51:4823–4839. [Google Scholar]

- Daher BT, Mohtar RH. Water–energy–food (WEF) Nexus tool 2.0: guiding integrative resource planning and decision-making. Water Int. 2015;40:748–771. [Google Scholar]

- Damkjaer S, Taylor R. The measurement of water scarcity: defining a meaningful indicator. Ambio. 2017;46:513–531. doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-0912-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de FSM Russo R, Camanho R. Criteria in AHP: a systematic review of literature. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;55:1123–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu D. The role of indicator-based sustainability assessment in policy and the decision-making process: a review and outlook. Sustainability. 2017;9:1018 [Google Scholar]

- Emas R. The Concept of Sustainable Development: Definition and Defining Principles. Florida International University; Florida, USA: 2015. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Emrouznejad A, Marra M. The state of the art development of AHP (1979–2017): a literature review with a social network analysis. Int J Prod Res. 2017;55:6653–6675. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen PJ. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Glob Environ Chang Part A. 2008;18:234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Farinha F, Oliveira MJ, Silva EM, Lança R, Pinheiro MD, Miguel C. Selection process of sustainable indicators for the algarve region—OBSERVE project. Sustainability. 2019;11:444 [Google Scholar]

- Fiksel JR, Eason T, Frederickson H. In: A Framework for Sustainability Indicators at EPA. Eason T, editor. Citeseer; Wshington D.C, USA: 2012. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Flammini A, Puri M, Pluschke L, Dubois O. Walking the Nexus Talk: Assessing the Water-energy-food Nexus in the Context of the Sustainable Energy for All Initiative. FAO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forman EH, Gass SI. The analytic hierarchy process—an exposition. Oper Res. 2001;49:469–486. [Google Scholar]

- Forsström J, Lahti P, Pursiheimo E, Rämä M, Shemeikka J, Sipilä K, Tuominen P, Wahlgren I. Measuring Energy Efficiency: Indicators and Potentials in Buildings, Communities and Energy Systems, VTT Research Notes. VTT Tiedottetta; Helsinki, Finland: 2011. p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunet C, Durieux S, Chanal H, Duc E. DFM method for aircraft structural parts using the AHP method. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2018;95:397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fürst C, Luque S, Geneletti D. Nexus thinking–how ecosystem services can contribute to enhancing the cross-scale and cross-sectoral coherence between land use, spatial planning and policy-making. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management. 2017;13:412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Garnåsjordet PA, Aslaksen I, Giampietro M, Funtowicz S, Ericson T. Sustainable development indicators: from statistics to policy. Environ Policy Gov. 2012;22:322–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanzadeh O, Feizizadeh B, Blaschke T. An interval matrix method used to optimize the decision matrix in AHP technique for land subsidence susceptibility mapping. Environ Earth Sci. 2018;77:584. [Google Scholar]

- Gomiero T. Soil degradation, land scarcity and food security: reviewing a complex challenge. Sustainability. 2016;8:281. [Google Scholar]

- Görener A. Comparing AHP and ANP: an application of strategic decisions making in a manufacturing company. Int J Res Bus Soc Sci. 2012;3 [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen D, Tacio H. The Coming Freshwater Crisis Is Already Here The Linkages Between Population and Water. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; 2002. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff H. Understanding the Nexus; Background Paper for the Bonn2011 Conference: the Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus; Stockholm. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howells M, Hermann S, Welsch M, Bazilian M, Segerström R, Alfstad T, Gielen D, Rogner H, Fischer G, Van Velthuizen H. Integrated analysis of climate change, land-use, energy and water strategies. Nat Clim Chang. 2013;3:621. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Towards a Sustainable Energy Future. Paris, France: International Energy Agency (IEA); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keskinen M, Guillaume JH, Kattelus M, Porkka M, Räsänen TA, Varis O. The water-energy-food nexus and the transboundary context: insights from large Asian rivers. Water. 2016;8:193. [Google Scholar]

- Kijne JW, Barker R, Molden DJ. Water productivity in agriculture: limits and opportunities for improvement. CABI International; UK: 2003. (Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 1). [Google Scholar]

- Kiker GA, Bridges TS, Varghese A, Seager TP, Linkov I. Application of multicriteria decision analysis in environmental decision making. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2005;1:95–108. doi: 10.1897/IEAM_2004a-015.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CW. Energy intensity ratios as net energy measures of United States energy production and expenditures. Environ Res Lett. 2010;5:044006 [Google Scholar]

- Kling CL, Arritt RW, Calhoun G, Keiser DA. Integrated assessment models of the food, energy, and water Nexus: a review and an outline of research needs. Annu Rev Resour Economics. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Sah B, Singh AR, Deng Y, He X, Kumar P, Bansal R. A review of multi criteria decision making (MCDM) towards sustainable renewable energy development. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2017;69:596–609. [Google Scholar]

- Kurian M. The water-energy-food nexus: trade-offs, thresholds and transdisciplinary approaches to sustainable development. Environ Sci Policy. 2017;68:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Leck H, Conway D, Bradshaw M, Rees J. Tracing the water–energy–food nexus: description, theory and practice. Geogr Compass. 2015;9:445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Preston F, Kooroshy J, Bailey R, Lahn G. Resources Futures. London, UK: Chatham House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yang H, Cudennec C, Gain A, Hoff H, Lawford R, Qi J, Strasser Ld, Yillia P, Zheng C. Challenges in operationalizing the water–energy–food nexus. Hydrol Sci J Des Sci Hydrol. 2017;62:1714–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Mabhaudhi T, Mpandeli S, Madhlopa A, Modi AT, Backeberg G, Nhamo L. Southern Africa’s water–energy Nexus: towards regional integration and development. Water. 2016;8:235. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrey D, Vittorio M. Moving from theory to practice in the water-energy-food nexus: an evaluation of existing models and frameworks. Water-energy Nexus 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell D, Coates J, Vaitla B. How Do Different Indicators of Household Food Security Compare? Empirical Evidence From Tigray. Medford, USA: Feinstein International Centre, Tufts University; 2013. p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- McGrane SJ, Acuto M, Artioli F, Chen PY, Comber R, Cottee J, Farr-Wharton G, Green N, Helfgott A, Larcom S. Scaling the nexus: towards integrated frameworks for analysing water, energy and food. Geogr J. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D, Kinzelbach W. Food security and sustainable resource management. Water Resour Res. 2015;51:4966–4985. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows DH, Meadows DH, Randers J, Behrens WW., III . The Limits to Growth: a Report to the Club of Rome A Report Fo the Club of Rome on the Predicament of Mankind. Universe Books; Washington DC, USA: 1972. p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Mohtar RH, Daher B. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Framework for facilitating multi-stakeholder dialogue. Water Int. 2016;41:655–661. [Google Scholar]

- Mpandeli S, Naidoo D, Mabhaudhi T, Nhemachena C, Nhamo L, Liphadzi S, Hlahla S, Modi A. Climate change adaptation through the Water-Energy-Food Nexus in Southern Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Schreiner B, Smith L, van Koppen B, Sally H, Aliber M, Cousins B, Tapela B, Van der Merwe-Botha M, Karar E. Water security in South Africa. Midrand, South Africa: Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo L, Mabhaudhi T, Magombeyi M. Improving water sustainability and food security through increased crop water productivity in Malawi. Water. 2016;8:411. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo L, Ndlela B, Nhemachena C, Mabhaudhi T, Mpandeli S, Matchaya G. The water-energy-Food Nexus: climate risks and opportunities in Southern Africa. Water. 2018;10:18. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo L, Mabhaudhi T, Modi A. Preparedness or repeated short-term relief aid? Building drought resilience through early warning in southern Africa. Water Sa. 2019;45:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, Roser M. Trade and Globalization. Our World in Data; Oxford, UK: 2018. OurWorldInDataorg. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I. Sustainability in the food-energy-water nexus: evidence from BRICS (Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa) countries. Energy. 2015;93:999–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I. The dynamic relationship between agricultural sustainability and food-energy-water poverty in a panel of selected Sub-Saharan African Countries. Energy Policy. 2017;107:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pamučar D, Stević Ž, Sremac S. A new model for determining weight coefficients of criteria in MCDM models: full consistency method (FUCOM. Symmetry. 2018;10:393. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Drimie S. Governance arrangements for the future food system: addressing complexity in South Africa. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev. 2016;58:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla R, Segall-Corrêa AM. Food insecurity measurement and indicators. Rev Nutr. 2008;21:15s–26s. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius I, Piketh S, Burger R, Neomagus H. A perspective on South African coal fired power station emissions. J Energy South Afr. 2015;26:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H-J, Zhu W-B, Wang H-B, Cheng X. Analysis and design of agricultural sustainability indicators system. Agric Sci China. 2007;6:475–486. [Google Scholar]

- Rao ND, Pachauri S. Energy access and living standards: some observations on recent trends. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:025011 [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, Rogers P. Assessment of agricultural sustainability. Curr Sci. 2006:439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rao M, Sastry S, Yadar P, Kharod K, Pathan S, Dhinwa P, Majumdar K, Sampat Kumar D, Patkar V, Phatak V. A Weighted Index Model for Urban Suitability Assessment—a GIS Approach. Bombay, Bombay, India: Bombay Metropolitan Regional Development Authority; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul G. Managing the food, water, and energy nexus for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in South Asia. Environ Dev. 2016;18:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul G, Sharma B. The nexus approach to water–energy–food security: an option for adaptation to climate change. Clim Policy. 2016;16:682–702. [Google Scholar]

- Reytar K, Hanson C, Henninger N. Indicators of Sustainable Agriculture: a Scoping Analysis. World Resources Institute (WRI); Washington DC, USA: 2014. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- RSA. National Development Plan Vision 2030: Our Future Make It Work. Pretoria, South Africa: National Planning Commission (NPC); 2011. p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty TL. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J Math Psychol. 1977;15:234–281. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty RW. The analytic hierarchy process—what it is and how it is used. Math Model. 1987;9:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty TL. Eigenvector and logarithmic least squares. Eur J Oper Res. 1990;48:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty TL. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int J Serv Sci. 2008;1:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Schernewski G, Schönwald S, Kataržytė M. Application and evaluation of an indicator set to measure and promote sustainable development in coastal areas. Ocean Coast Manag. 2014;101:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K, Aumann I, Hollander I, Damm K, von der Schulenburg J-MG. Applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process in healthcare research: a systematic literature review and evaluation of reporting. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:112. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0234-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbinin Ad, Carr D, Cassels S, Jiang L. Population and environment. Annual Revieew of Environment and Resources. 2007;32:345–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.32.041306.100243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling F, Khan A, Juricich R, Fong V. Using indicators to measure water resources sustainability in California; World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2013: Showcasing the Future; 2013. pp. 2708–2715. [Google Scholar]

- Siksnelyte I, Zavadskas E, Streimikiene D, Sharma D. An overview of multi-criteria decision-making methods in dealing with sustainable energy development issues. Energies. 2018;11:2754 [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Murty HR, Gupta SK, Dikshit AK. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol Indic. 2012;15:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Speirs J, McGlade C, Slade R. Uncertainty in the availability of natural resources: fossil fuels, critical metals and biomass. Energy Policy. 2015;87:654–664. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan RM, Mohtar RH, Daher B, Embid Irujo A, Hillers A, Ganter JC, Karlberg L, Martin L, Nairizi S, Rodriguez DJ. Water–energy–food nexus: a platform for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Water Int. 2018;43:472–479. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Thomas MO. In: Novotná J, Moraová H, Krátká M, Stehlíková N, editors. Process-object difficulties in linear algebra: eigenvalues and eigenvectors; Proceedings of the 30th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education; Czech Republic. 2006. p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Teknomo K. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Tutorial. Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University; 2006. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Terrapon-Pfaff J, Ortiz W, Dienst C, Gröne M-C. Energising the WEF nexus to enhance sustainable development at local level. J Environ Manage. 2018;223:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantaphyllou E, Mann SH. Using the analytic hierarchy process for decision making in engineering applications: some challenges. International Journal of Industrial Engineering: Applications and Practice. 1995;2:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tscheikner-Gratl F, Egger P, Rauch W, Kleidorfer M. Comparison of multi-criteria decision support methods for integrated rehabilitation prioritization. Water. 2017;9:68. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez M, Hester PT. An analysis of multi-criteria decision making methods. Int J Oper Res. 2013;10:56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Warhurst A. Sustainability Indicators and Sustainability Performance Management, Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development [MMSD] Project Report. University of Warwick; UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weisser D. A guide to life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from electric supply technologies. Energy. 2007;32:1543–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Widianta M, Rizaldi T, Setyohadi D, Riskiawan H. J Phys Conf Ser. IOP Publishing; 2018. Comparison of multi-criteria decision support methods (AHP, TOPSIS, SAW & PROMENTHEE) for employee placement; 012116 [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz M. Equipment selection based on the AHP and Yager’s method. J South Afr Inst Min Metall. 2015;115:425–433. [Google Scholar]

- Zanella A, Camanho A, Dias TG. Benchmarking countries’ environmental performance. J Oper Res Soc. 2013;64:426–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen L, Routray JK. Operational indicators for measuring agricultural sustainability in developing countries. Environ Manage. 2003;32:34–46. doi: 10.1007/s00267-003-2881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Ang B, Poh K. A mathematical programming approach to constructing composite indicators. Ecol Econ. 2007;62:291–297. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.