Abstract

CCL17 is produced by conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), signals through CCR4 on regulatory T cells (Tregs), and drives atherosclerosis by suppressing Treg functions through yet undefined mechanisms. Here we show that cDCs from CCL17-deficient mice display a pro-tolerogenic phenotype and transcriptome that is not phenocopied in mice lacking its cognate receptor CCR4. In the plasma of CCL17-deficient mice, CCL3 was the only decreased cytokine/chemokine. We found that CCL17 signaled through CCR8 as an alternate high-affinity receptor, which induced CCL3 expression and suppressed Treg functions in the absence of CCR4. Genetic ablation of CCL3 and CCR8 in CD4+ T cells reduced CCL3 secretion, boosted FoxP3+ Treg numbers, and limited atherosclerosis. Conversely, CCL3 administration exacerbated atherosclerosis and restrained Treg differentiation. In symptomatic versus asymptomatic human carotid atheroma, CCL3 expression was increased, while FoxP3 expression was reduced. Together, we identified a non-canonical chemokine pathway whereby CCL17 interacts with CCR8 to yield a CCL3-dependent suppression of atheroprotective Tregs.

Keywords: chemokines, chemokine receptors, atherosclerosis, regulatory T cells

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a lipid-driven chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall, underlying most cardiovascular diseases (CVD).1 Dendritic cells (DCs) have been identified in healthy and inflamed arterial intima of mice and humans2–4, and advanced human plaques contain an increased number of DCs in clusters with T cells.5 The chemokine CCL17 (TARC/thymus and activation-regulated chemokine) was found to be elevated in patients with CVD6 and atopic dermatitis, who are prone to develop CVD.7,8 An intronic single nucleotide polymorphism (rs223828) associates with higher serum CCL17 and elevated CVD risk in humans9, and mouse studies revealed a pro-inflammatory role of CCL17 in atherosclerosis10 and colitis.11 CCL17 is primarily expressed by a subset of antigen-presenting MHCII+ conventional DCs (cDCs), which migrate to draining lymph nodes (LNs) to prime naive T cells, and plays a crucial role in the migration of various T-cell subsets including CD4+ T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs).12–14 Tregs use multiple effector mechanisms to modulate immune responses and to guard the balance between immune activation and tolerance toward self-antigens.15 Naturally arising CD4+CD25+ Tregs limit atherosclerosis development and have been implicated in the regression of established atherosclerotic lesions by licensing pro-resolving macrophage functions.16,17 We found that CCL17 controls Treg homeostasis, restraining their expansion and thereby promoting atherosclerosis.10 Accordingly, genetic deficiency or antibody blockade of CCL17 reduced atheroprogression by facilitating Treg expansion and survival in lymphoid organs, leading to Treg expansion.10 However, the precise mechanisms, by which DC-derived CCL17 controls Treg homeostasis remain to be elucidated, namely relevant soluble mediators or receptors involved.

To date, CCR4 is the only cognate signaling receptor for CCL17 identified and known to contribute to the recruitment and in vivo functions of Tregs.18 Yet, CCR4 deficiency did not phenocopy the effects on Tregs and protection from atherosclerosis seen in CCL17-deficient mice.10 Analogous findings were obtained in a model of atopic dermatitis, where the inflammatory burden was reduced in mice lacking CCL17 but not CCR4.19 Consistently, deficiency in DC-derived CCL17 was protective against intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of colitis by creating a cytokine milieu that facilitated Treg expansion and, likewise, did not require CCR4.11 In conjunction, these results suggest the existence of an alternative CCR4-independent receptor pathway triggered by CCL17. Here, we provide unequivocal evidence that CCL17 signals via CCR8 as an alternative high-affinity receptor expressed on T-cell and DC subsets, harnessing the autocrine and paracrine release of CCL3 to mediate suppression of atheroprotective Tregs via its receptor CCR1.

Results

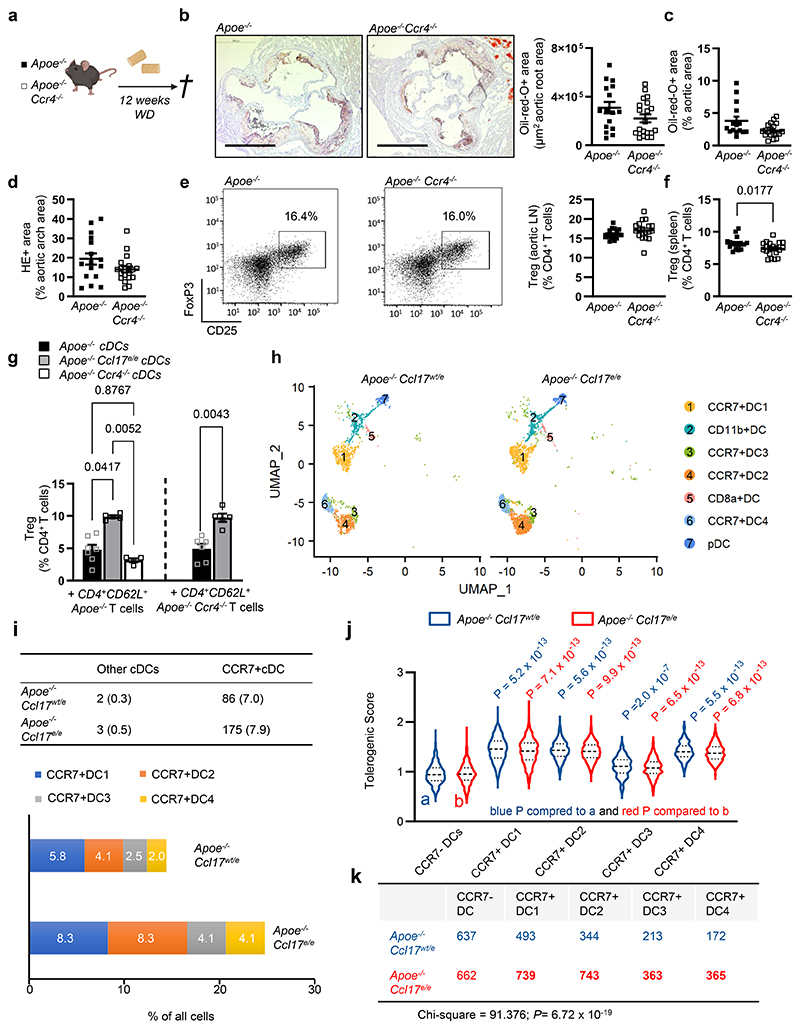

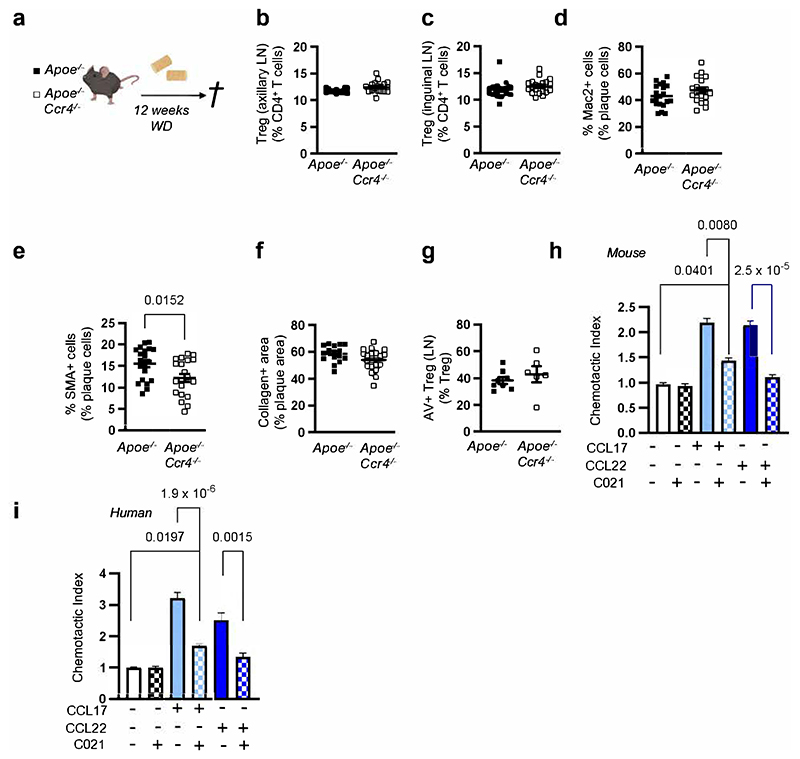

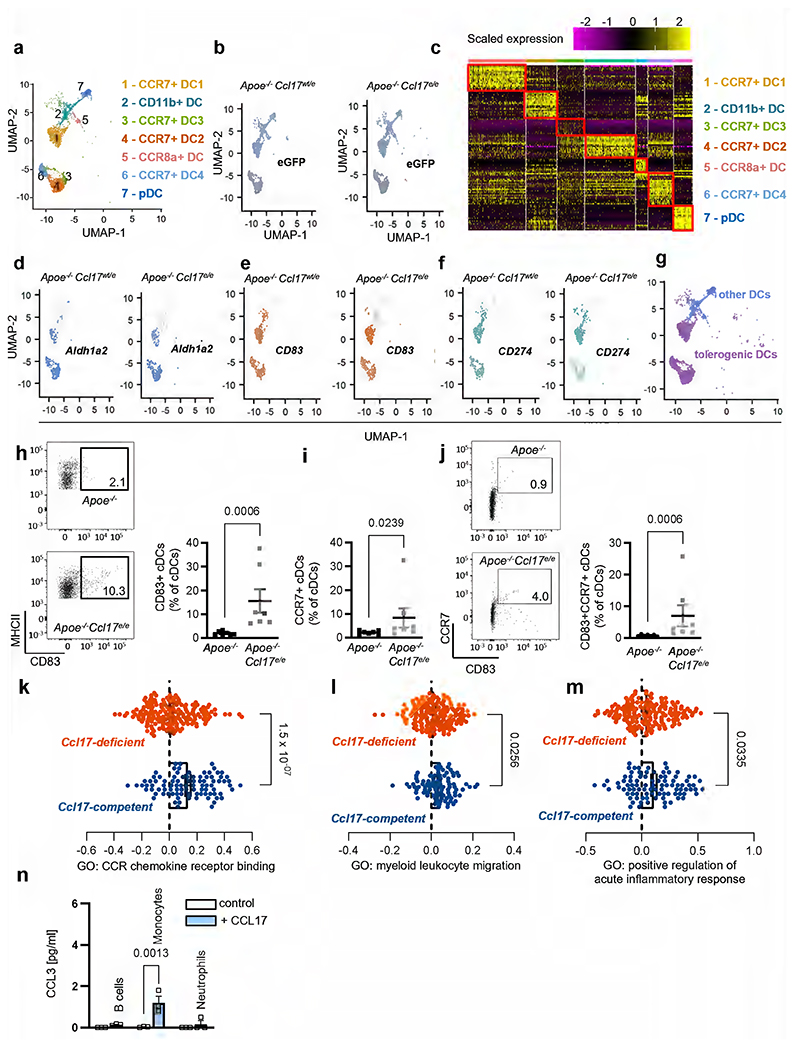

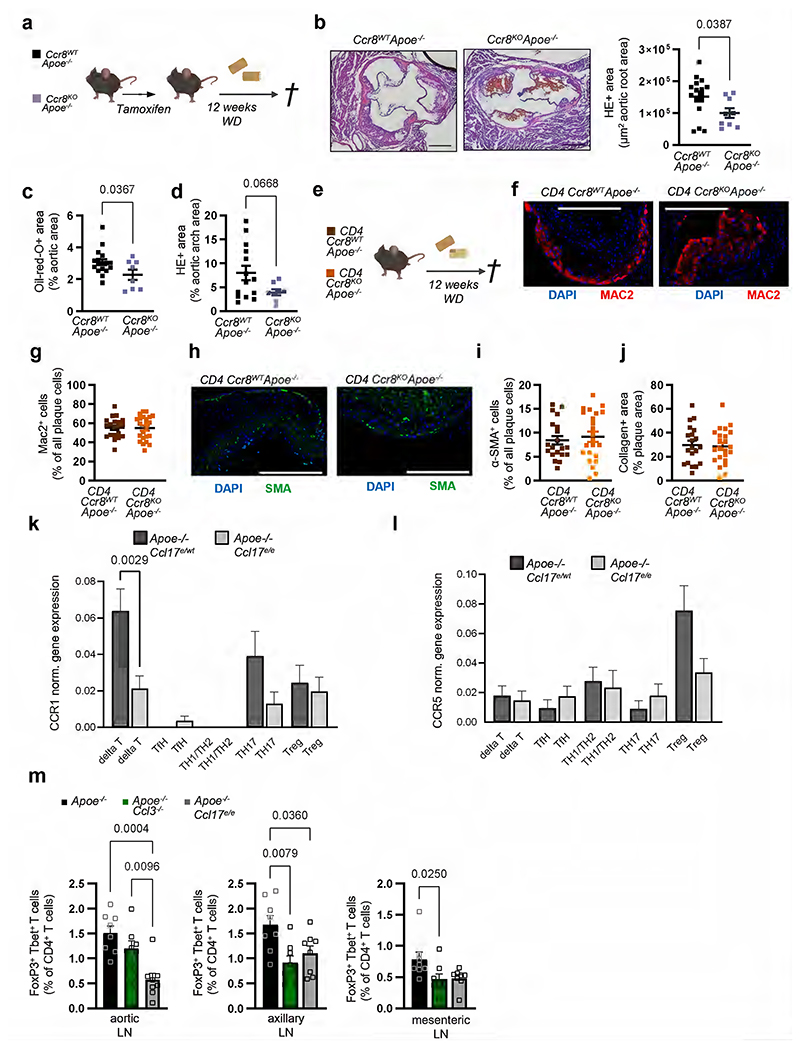

CCR4 does not mediate the effects of CCL17 on atherogenesis

Mice with a targeted replacement of the Ccl17 gene by the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene (eGFP; Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice) displayed a reduced atherosclerotic lesion size in the aortic root, thoraco-abdominal aorta and aortic arch but unchanged lesional macrophage, SMC and collagen content after 12 weeks of western-type diet (WD), when compared with Apoe-/- littermate controls (Extended Data Fig. 1a-g). This was related to a higher frequency of CD25+Foxp3+CD3+CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in para-aortic LNs, spleen, axillary and inguinal LNs of Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice, as compared to controls (Extended Data Fig. 1h-l). In contrast, mice lacking the canonical CCL17 receptor CCR4 did not phenocopy the effects observed in CCL17-deficient mice. Neither hematopoietic Ccr4 deficiency10 nor systemic deletion in Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice altered atherosclerotic lesion size, composition or Treg frequencies after 12 weeks of WD, as compared to controls, and the decrease in apoptotic Tregs in LNs of CCL17-deficient mice10 was not found in LNs of CCR4-deficient mice (Fig. 1a-1f; Extended Data Fig. 2a-g). Lipid levels, circulating leukocyte and thrombocyte counts did not differ between Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e, Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- and respective control mice (Supplementary Table 1 and 2) and thus did not explain the observed phenotype. Using recombinant CCL17, CCL22 and the CCR4 inhibitor C021 in Transwell assays, we confirmed CCR4-dependent chemotaxis of CD4+ T cells isolated from Apoe-/- mice and from human PBMCs in vitro, as C021 abrogated CCL22-induced migration and inhibited CCL17-induced migration (Extended Data Fig. 2h,i). Together, these data indicate that an alternative signaling pathway is involved in mediating the effects of CCL17, a notion reinforced by investigating Treg homeostasis. Co-culturing CD4+CD62L+ T cells from Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice with ex vivo isolated cDCs revealed an increased differentiation of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in the presence of Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e cDCs but not Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- or Apoe-/- cDCs (Fig. 1g). To explore whether CCL17-deficient cDCs differentially express putative mediators of this effect, we sorted CD45+CD11c+CD3-CD19- cells from LNs of Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice and performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) (GSE200862). Our analysis identified seven different DC clusters, with CCL17-expressing eGFP+ cells almost exclusively located among CCR7+ cDCs (Fig. 1h; Extended Data Fig. 3a-g). In CCL17-deficient samples, CCR7+ cDCs were enriched and had a higher tolerogenic score compared to other DC clusters (Fig. 1i). A tolerogenic profile was defined by high expression of Aldh1a2, CD83 and CD274 in CCR7+ cDCs (Fig. 1j; Extended Data Fig. 3d-g) and analysis of a gene set defining immunogenic and tolerogenic cell properties (Supplementary Table 3). While the tolerogenic score was similar in hetero- and homozygous samples, the number of CCR7+ tolerogenic cDCs was higher in CCL17-deficient mice (Fig. 1j,k), showing that more cDCs acquire a tolerogenic phenotype in the absence of CCL17. Accordingly, flow cytometry of cDCs in aortic LNs of Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice uncovered a higher percentage of CD83+, CCR7+ and CD83+CCR7+ cDCs (Extended Data Fig. 3h-j), Deletion of CD83 in cDCs confers a pro-inflammatory DC phenotype driving antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation, Th17 commitment but impairing Treg suppressive capacity and resolving mechanisms.20 Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) further revealed an enrichment of pro-inflammatory pathways in CCL17-competent cDCs (Extended Data Fig. 3k-m), in line with an atheroprotective role of CCR7 found in Apoe-/- mice.21

Figure 1. CCR4 does not affect atherosclerosis or Tregs, while CCL17-deficiency increases tolerogenic DCs.

(a) Experimental scheme of Western-diet (WD) feeding; (b) Representative sections and quantification of lesion area after Oil-Red-O staining (ORO) for lipid deposits in the aortic root of Apoe-/- (n=16) or Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- (n=20) mice. Scale bar = 500 µm; (c) Quantification of lesion area after ORO in the thoraco-abdominal aorta of Apoe-/- (n=5) or Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- (n=19) mice; (d) Atherosclerotic lesion size quantified by H&E staining in aortic arches of Apoe-/- (n=16) or Apoe-/- Ccr4-/- (n=19) mice; (e,f) Representative dot plots and flow cytometric quantification of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in para-aortic lymph nodes (LNs) (e) and spleen (f) of Apoe-/- (e, n=16; f, n=16) or Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- (e, n=19; f, n=20) mice; (g) Co-culture of CD45+CD11c+MHCII+ DCs sorted from Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e or Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice with splenic CD4+CD62L+ T cells isolated from Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice. After 72 hours, the abundance of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs was determined by flow cytometry (individual number of experiments per bar from left to right n=7, 5, 4, 6, 5). Besides the cells, no other factors were added to the culture; (h-j) CD45+CD3-CD19-CD11c+ cells were sorted from pooled LNs of Apoe-/- Ccl17wt/e or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice on chow diet. (h) UMAP projection of 4731 single cells colored by inferred cell types consisting of 7 distinct dendritic cell (DC) clusters (i) Depicted are eGFP+ cell counts in CCR7+ DCs or other (CCR7-) DCs (percentage of total numbers) and proportions of 4 distinct CCR7+ DC clusters among all single cells (CD45+CD3-CD19-CD11c+) (bottom). (j-k) Tolerogenic score calculated for 4 distinct CCR7+DC clusters and other (CCR7-) DC clusters based on the top 20 genes differentially expressed between the groups (top) as [1 + mean (top 20 upregulated tolerogenic genes)]/[1 + mean(top 20 upregulated immunogenic genes)]. Table depicts cell counts of four CCR7+ DC and other DC clusters (k). LNs for scRNA-seq were obtained from Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e (n=8) and Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (n=6). (a-k) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-tailed P values as indicated and as analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test (b,e,f), Mann-Whitney U test (c,d), or Kruskal-Wallis H with Dunn’s post hoc test (g,j). Differences in proportion in DC clusters between Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e and Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e were computed by Pearson’s chi-square (k).

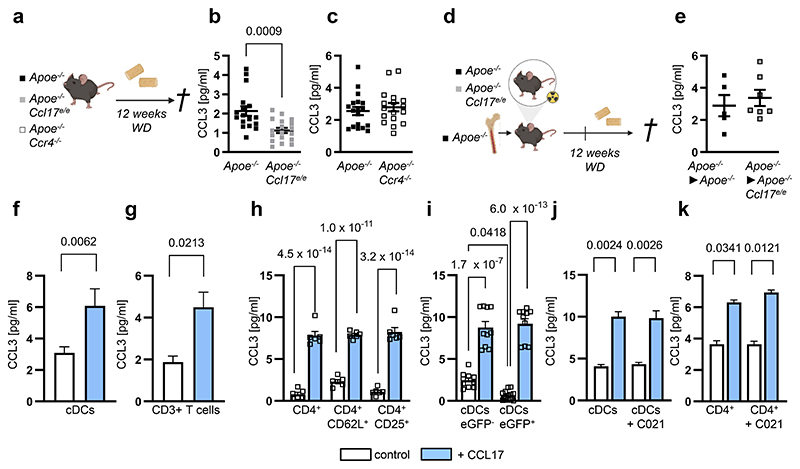

CCL17 induces CCL3 release independent of CCR4 expression

Because CCL17-deficient mice displayed increased numbers of tolerogenic cDCs, we performed an unbiased screen for differentially regulated inflammatory mediators. A multiplex-bead-array for cytokines and chemokines identified only CCL3 to be significantly reduced in plasma of Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice versus Apoe-/- controls after 12 weeks of WD (Fig. 2a,b; Extended Data Table 1), corresponding with decreased lesion size and increased Treg numbers (Extended Data Fig. 1). In contrast, CCL3 plasma levels in Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice were unaffected (Figure 2a,c), consistent with unaltered atherosclerotic burden (Fig. 1a-f). Reconstituting Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice with CCL17-sufficient bone marrow (BM) restored CCL3 plasma levels to those seen in Apoe-/- controls (Fig. 2d,e). Given that CCL3 was diminished in systemic circulation of CCL17-deficient mice, we assessed which cell types release CCL3 in response to CCL17 by sorting CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs, CD3+ T cells and CD19+B220+ B cells from LNs, monocytes and neutrophils from spleen and BM for in vitro treatment with CCL17. ELISA or multiplex-bead-array identified cDCs and T cells as the main source of CCL3 upon CCL17 stimulation, whereas CCL3 release from monocytes, B cells and neutrophils was less marked or negligible (Fig. 2f,g; Extended Data Fig. 3n). CCL3 release was induced by CCL17 in distinct T-cell subsets, namely splenic CD4+ T helper cells, CD4+CD62L+ naïve/memory T cells and CD4+CD25+ Tregs (Fig. 2h). Comparing sorted CCL17+ (eGFP-) with CCL17-deficient CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs (eGFP+), we found that baseline CCL3 secretion was lower in CCL17-deficient cDCs, while CCL17-stimulated CCL3 release was similar (Fig. 2i), implying that CCL17+ cDCs can release CCL17 in an autocrine or paracrine fashion to induce CCL3 secretion. This effect was independent of CCR4 in cDCs and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2j,k), indicating that CCL17 mediates CCL3 secretion through an alternative receptor.

Figure 2. CCL3 induction by CCL17 does not require CCR4 but inversely correlates with Treg numbers.

(a) Experimental scheme of Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e and Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- mice fed a Western-diet (WD); (b,c) CCL3 plasma concentrations in Apoe-/- (n=17) and Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (n=18) mice (b) or Apoe-/- (n=18) and Apoe-/-Ccr4-/- (n=17) mice (c), as measured by ELISA; (d) Experimental scheme of reconstituting irradiated Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice with Apoe-/- bone marrow before WD feeding; (e) CCL3 concentrations in plasma of Apoe-/-►Apoe-/- (n=5) or Apoe-/-►Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (n=7) mice were measured by ELISA; (f) Sorted CD11c+MHCII+ conventional DCs (cDCs) (control, n=17 replicates over 11 independent experiments; CCL17, n=23 replicates over 12 independent experiments) or (g) CD3+ T cells (control and CCL17, n=17 replicates over 6 independent experiments) were cultured for 4 hours with or without recombinant mouse CCL17. CCL3 concentrations in the supernatant were measured by multiplex-bead-array; (h) Isolated T-cell subsets from LN suspensions of Apoe-/- mice were stimulated for 4 hours in the presence or absence of CCL17. CCL3 concentrations in supernatants are measured by ELISA (n=6 for each bar); (i) Sorted CD11c+MHCII+eGFP- cDCs (CCL17-competent, control and CCL17, n=10) or CD11c+MHCII+ eGFP+ cDCs (CCL17-deficient, control n=12; CCL17 n=10) from Apoe-/-Ccl17e/WT mice were cultured for 4 hours in the presence or absence of CCL17. CCL3 concentrations in supernatants were measured by ELISA; (j) Sorted CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs from LNs of Apoe-/- mice were cultured for 4 hours in the presence or absence of CCL17 with or without the CCR4 inhibitor C021, and CCL3 concentrations in supernatants of isolated cDCs were measured by multiplex-bead-array (n=20 replicates across 6 independent experiments for all conditions); (k) Isolated T-cell subsets from LN suspensions of Apoe-/- mice were stimulated with or without CCL17 in the presence of absence of the CCR4 inhibitor C021 for 4 hours, and CCL3 concentrations in supernatants were measured by ELISA (control, n=39 replicates; C021, n=38 replicates; CCL17, 42 replicates; CCL17+C021, n=40 replicates; all distributed over 9 independent experiments); (a-k) Data represents mean±SEM. Two-sided P values as indicated versus control/Apoe-/- and as analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test (b,c,e), nested t test (f,g), two-way ANOVA (h) or nested ANOVA (j,k) with Holm-Šídák’s post hoc test, and Kruskal-Wallis H with Dunn’s post hoc test (i).

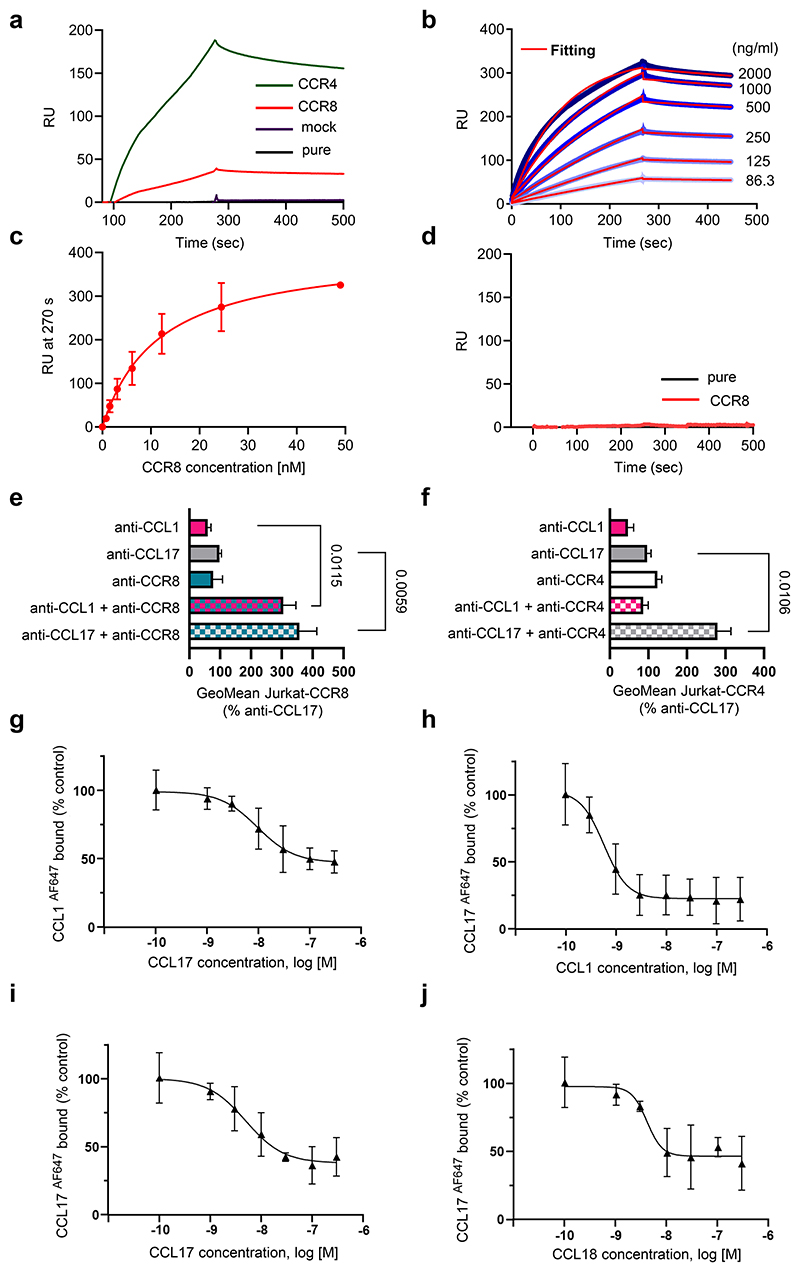

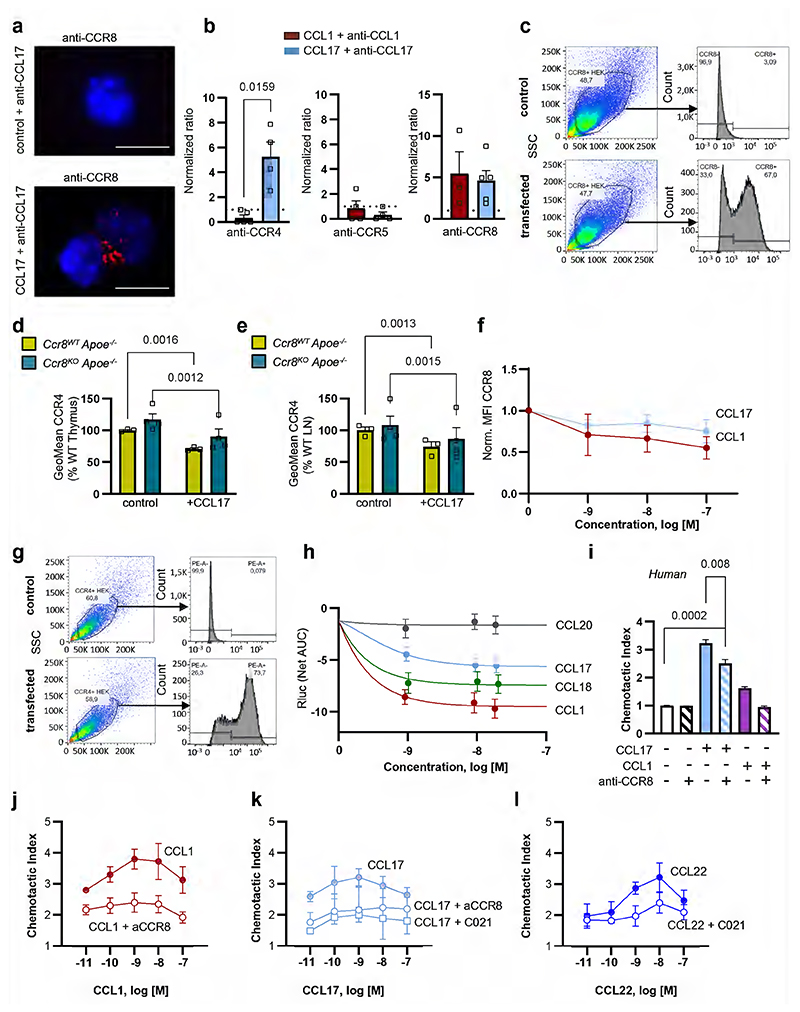

CCL17 binds and activates CCR8 as a non-canonical receptor

Searching for alternative receptors, we revisited the notion that CCR8 could be a receptor for CCL1722 (findings subsequently contested23), as CCR8 has also been implicated in controlling the migration and function of Tregs.24,25 To probe for binding of CCL17 to CCR8, we used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to record the concentration-dependent binding of CCR8-carrying liposomes to biotinylated CCL17 immobilized on a BIAcore C1 sensor chip, using CCR4-carrying, mock protein-carrying or pure liposomes as positive or negative controls (Fig. 3a-d). CCR8-bearing liposomes displayed saturable binding with a KD (koff/kon) of 1.1±0.4 nM, indicating a high-affinity interaction between CCL17 and CCR8 (Fig. 3b,c). While CCR4-bearing liposomes showed even stronger binding, irrelevant protein-bearing or empty liposomes did not support binding to CCL17 (Fig. 3a). A CCL5-chip used as a negative control did not support binding of CCR8-bearing liposomes (Fig. 3d). We next used a proximity ligation assay in CCR4- or CCR8-transfected Jurkat cells or in adherent cDCs from LNs of Apoe-/- mice treated with CCL17 or the cognate CCR8 ligand CCL1 and subsequently with non-blocking antibodies to CCL17 or CCL1 and to CCR4, CCR8, or CCR5 to yield signals reporting receptor interactions of CCL17 or CCL1. Proximity ligation signals and their quantification revealed an interaction of CCL17 with both CCR4 and CCR8, whereas CCL1 interacted with CCR8 but not with CCR4 (Fig. 3e,f; Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). We further performed receptor binding competition studies using fluorescently labeled CCL1 and CCL17 in CCR8-expressing HEK293 transfectants (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Inhibition of CCL1AF647 binding to CCR8-transfectants with increasing concentrations of unlabeled CCL17 yielded an IC50 of 9.4±4.4 nM. Inhibition of CCL17AF647 binding to CCR8-transfectants with increasing concentrations of unlabeled CCL1 yielded an IC50 of 0.58±0.24 nM, and with unlabeled CCL18 yielded an IC50 of 4.1±1.7 nM, similar to unlabeled CCL17 (IC50 4.9±2.4 nM) (Fig. 3g-j). Using primary CD4+ T cells from thymus or LNs of tamoxifen-inducible CCR8-competent UniCreErt2-Ccr8flox/flox (Ccr8WTApoe-/-) or CCR8-deficient UniCreErt2+Ccr8flox/flox (Ccr8KOApoe-/-) Apoe-/- mice, we found CCR8 internalization upon CCL17 treatment in CCR8-expressing but not CCR8-deficient T cells (Fig. 4a,b). The expression of CCR4 was unaltered in CCR8-deficient T cells and CCR4 internalization by CCL17 was preserved, while CCR8 internalization by CCL1 and CCL17 was dose-dependent in these cells (Extended Data Fig. 4d-f). In addition, human CD4+ T cells exhibited both CCR4 and CCR8 internalization upon CCL17 treatment, whereas CCL1 only internalized CCR8 and CCL22 only internalized CCR4 (Fig. 4c,d). These experiments indicate that CCL17 binds to CCR8.

Figure 3. CCL17 binds to CCR8 with high affinity in human and mouse cells.

(a-d) Surface plasmon resonance to detect CCL17-CCR8 interactions. RU = response units; (a) Human biotinylated CCL17 was immobilized on C1 sensor chips and sensorgrams of human CCR8-, CCR4-, mock protein-carrying or pure liposomes perfused at 0.5 µg/ml were recorded; (b) Binding kinetics of CCR8-carrying liposomes perfused at indicated concentrations on immobilized CCL17 were determined after fitting (red) of curves (blue) with a 1:1 interaction model. Concentration-independent dissociation was low (koff 4.2±0.8E-04/s), indicating high stability. Calculating the koff/kon ratio using the theoretical molecular weight of CCR8 (40.2 kD) yielded an apparent KD of 1.1±0.4 nM. Shown is one representative of 5 experiments; (c) Saturation binding of experiments from (b) were fitted with one-site specific binding, yielding a KD of 11.7±2.1 nM. Data represent mean±SD (n=5 independent experiments). (d) Sensorgrams of CCR8-carrying (red) or pure liposomes (black) perfused at 0.5 µg/ml on biotinylated human CCL5 immobilized as a negative control. (e,f) Interactions of mouse CCL17 or CCL1 with CCR4 and CCR8 were analyzed in stably transfected Jurkat cells using Duolink proximity-ligation assays. Signals generated by close proximity of non-blocking antibodies bound to ligands or receptors on CCR8- (e, all n=9 replicates over 4 independent experiments) or CCR4-transfectants (f, anti-CCL1, anti-CCL17+anti-CCR4, n=19 replicates each over 6 independent experiments; anti-CCL17, n=22 replicates; anti-CCR4, n=18 replicates; anti-CCL1+anti-CCR4, n=22 replicates over 7 independent experiments) were quantified by flow cytometry. For anti-CCL17 and anti-CCL1 incubation, recombinant CCL17 (100 ng/ml) or CCL1 (50 ng/ml) were added, respectively. (g-j) HEK293 cells stably transfected with human CCR8 were incubated with CCL1 or CCL17 labeled with Alexa-Fluor 647 (AF467) at the C-terminus (10 nM). Background binding to mock-transfected HEK293 cells was subtracted, data were normalized to binding without unlabeled chemokine (control) and subjected to nonlinear fitting. Data represent mean±SD (n=3 independent experiments). (g) Inhibition of CCL1AF647 binding to CCR8-transfectants with increasing concentrations of unlabeled CCL17; IC50 9.4±4.4 nM; (h-j) Inhibition of CCL17AF647 binding to CCR8-transfectants with increasing concentrations of unlabeled CCL1 (h, IC50 0.58±0.24 nM), CCL17 (i, IC50 4.9±2.4 nM) or CCL18 (j, IC50 4.1±1.7 nM). (e,f) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values versus respective controls were analyzed by nested ANOVA.

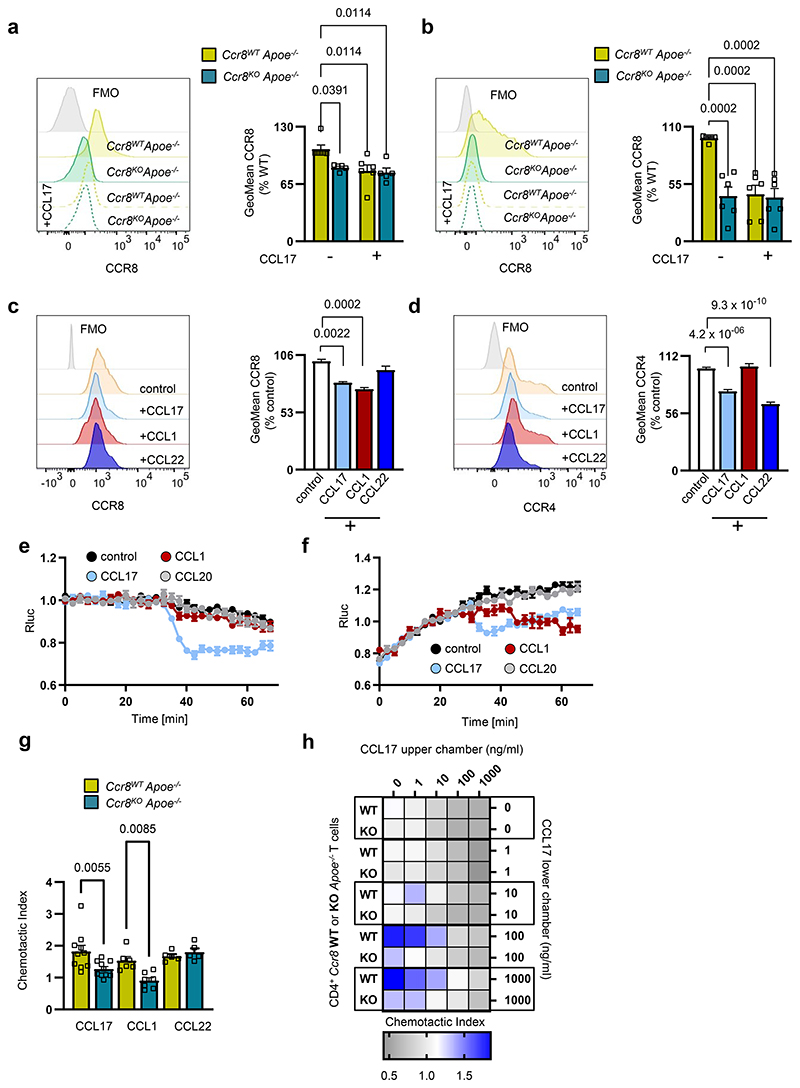

Figure 4. CCL17-CCR8 interaction induces G-protein-coupled signaling and T-cell chemotaxis.

(a,b) Representative histogram and quantification of CCR8 surface availability and internalization upon stimulation with recombinant mouse CCL17 (100 ng/ml) on CD4+ T cells isolated from thymus (a) and LNs (b) of UniCreErt2-Ccr8flox/floxApoe-/- (Ccr8WTApoe-/-, a,b n=6 for all conditions) or CCR8-deficient UniCreErt2+Ccr8flox/floxApoe-/- (Ccr8KOApoe-/- a, n=5 for both, b, n=6 for both) mice; (c,d) Representative histogram and quantification of CCR8 (c) and CCR4 (d) surface expression and internalization upon stimulation with recombinant human CCL17 (100 ng/ml), CCL1 (50 ng/ml) or CCL22 (50 ng/ml) on CD4+ T cells isolated from human PBMCs (c,d number of replicates in parentheses over number of independent experiments per bar from left to right for c, n=(59)12, (28)6, (29)6, (23)6 and d, n=(56)12, (27)6, (23)6, (27)6); (e,f) Glosensor-HEK293 cells transfected with either CCR4 (e) or CCR8 (f). Cells were stimulated with recombinant human CCL17, CCL1, CCL20 (all 100 ng/ml) or PBS as vehicle control after 25 min of equilibration. Shown is one of 4 representative experiments; (g) Transwell migration of CD4+ T cells isolated from Ccr8WTApoe-/- or Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice towards recombinant murine chemokines. Migrated cells were quantified by flow cytometry, chemotactic index induced by the chemokines CCL17 (100 ng/ml), CCL1 (50 ng/ml) and CCL22 (50 ng/ml) was calculated as the ratio of chemokine-stimulated to unstimulated migration (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=10,10, 6, 7, 5, 5); (h) Transwell migration of CD4+ T cells isolated from Ccr8WTApoe-/- or Ccr8KOApoe-/-mice towards recombinant murine CCL17 displayed in a checkerboard heat map format; columns indicate CCL17 concentrations (ng/ml) in the upper chamber, rows indicate CCL17 concentrations (ng/ml) in the lower chamber. While blue represents enhanced, grey indicates reduced migration towards CCL17 in the bottom chamber. Each box represents a mean value of 3 independent experiments; (a-d, g) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values as indicated versus Ccr8WT Apoe-/- (a,b,g) or control (c,d) and as analyzed by two-way (a,b,g) or univariate (c,d) ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s post hoc test.

To test whether CCL17 can elicit Gi-protein-coupled signaling via CCR8, we determined down-stream cAMP levels in Glosensor-HEK293 cells transfected with CCR4 or CCR8 (Extended Data Fig. 4c,g) and stimulated with recombinant human CCL17, CCL1 or CCL20 (Fig. 4e,f). Dose-response curves revealed a near maximal CCR8 activation by CCL1 at a concentration of ≈ 1.2 nM, corresponding to the IC50 for receptor binding competition, whereas CCL17 and CCL18 were less effective (Extended Data Fig. 4h). Prior studies reported CCL17 binding to CCR8 but lack of subsequent calcium signaling.22 In contrast, our results revealed that CCL17 induced Gi-mediated signaling both in CCR4- and CCR8-transfectants. CCL1 induced Gi-signaling in CCR8- but not CCR4-transfectants, whereas CCL20, as a negative control, had no effect (Fig. 4e,f). We next performed Transwell migration assays with CD4+ T cells from Ccr8WTApoe-/- or Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice. CCL17-induced migration of CD4+ T cells lacking CCR8 was lower than that of wild-type cells, and more markedly reduced than by a CCR8 antibody in human T cells, whereas migration towards CCL1 was abolished and that towards CCL22 was unaffected (Fig. 4g; Extended Data Fig. 4i). The migration of Apoe-/- CD4+ T cells induced by CCL1, CCL17 and CCL22 followed a bell-shaped dose-response curve mediated by CCR8 and CCR4, respectively, as shown by receptor blockade (Extended Data Fig. 4j-l) and was chemotactic, as evident by a checker-board analysis applying CCR8-competent and -deficient CD4+ T cells with CCL17 in the upper chamber (Fig. 4h). Together, our data demonstrate that CCL17 activates CCR8 to induce Gi-signaling and functional responses.

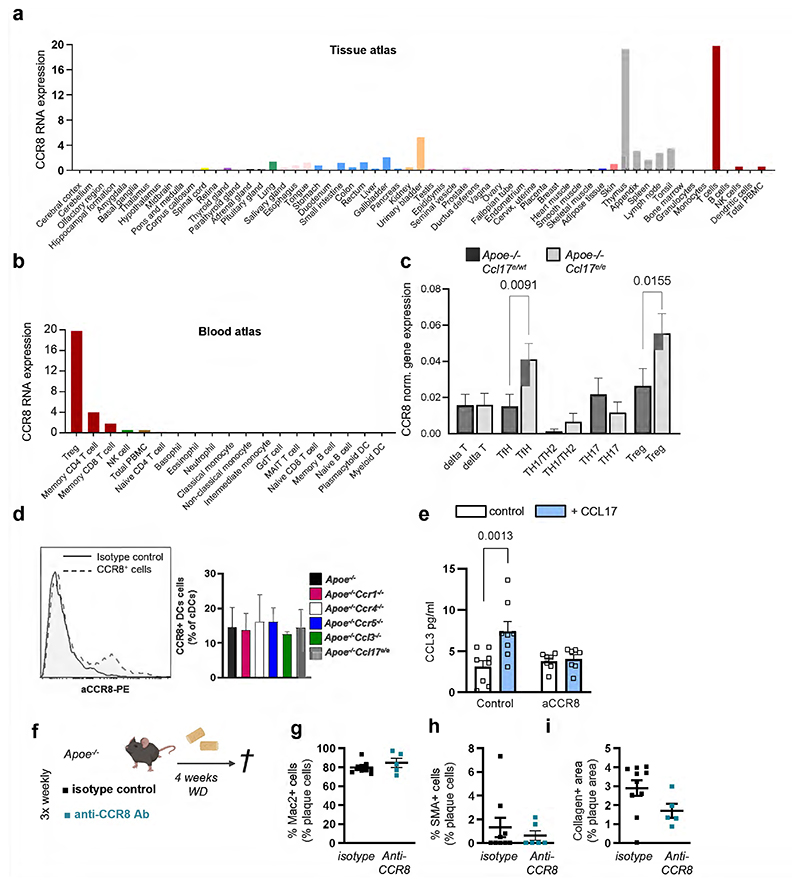

CCL17/CCR8-CCL3 axis interferes with Treg differentiation

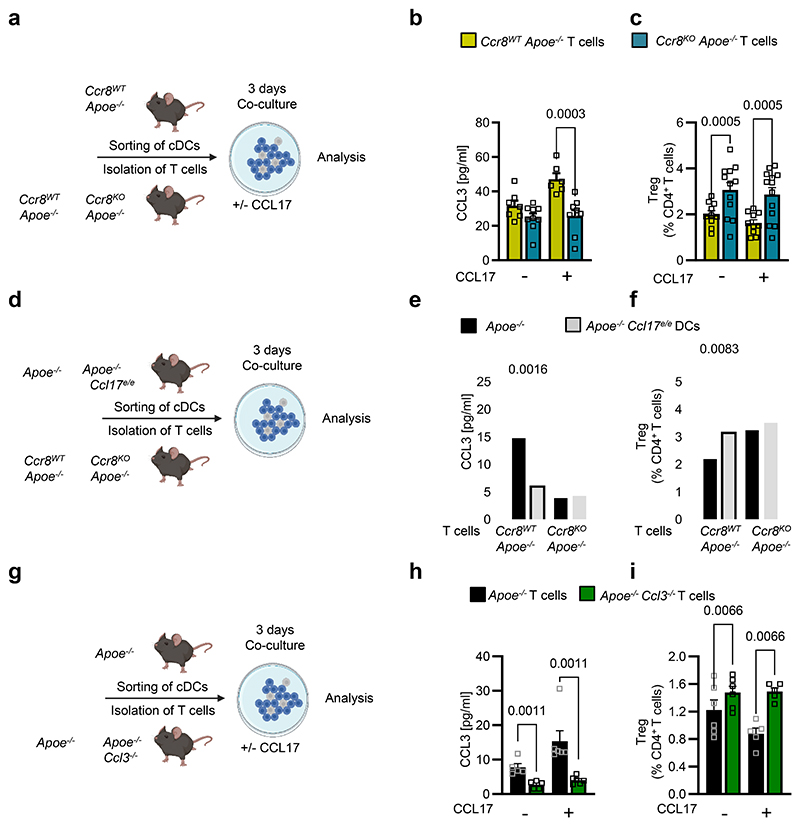

Having established the interaction of CCL17 with CCR8, we assessed which cell types express CCR8. Screening the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org26) we found CCR8 mostly expressed on T-cell subsets with an enrichment in Tregs (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Accordingly, scRNAseq of aortic LNs from CCL17-competent and CCL17-deficient mice revealed a prominent expression of CCR8 in CD4+ T cells, mainly in Tregs and follicular T helper, and detectable CCR8 expression in a cDC subset (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). We next assessed whether the CCL17-CCR8 pathway directly mediates CCL3 secretion by culturing CD4+ T cells from Apoe-/- mice with or without CCL17 and an antibody to CCR8 for 4 hours. ELISA revealed an increase in CCL3 release induced by CCL17 alone but not when CCR8 was blocked (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Likewise, CD4+CD62L+ T cells sorted from Ccr8WTApoe-/- or Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice were co-cultured with CCR8-competent cDCs with or without CCL17 addition for 3 days to quantify CCL3 release and Treg differentiation (Fig. 5a). CCL3 secretion was induced by CCL17 in CCR8-competent but not CCR8-deficient CD4+ T cell/DC co-cultures (Fig. 5b). Correspondingly, the number of Tregs in co-cultures of cDCs with CCR8-deficient CD4+ T cells was higher than in CCR8-bearing controls, even after addition of CCL17 (Fig. 5c). This indicates that CCL17-induced signaling via CCR8 on CD4+ T cells and a subsequent autocrine CCL3 release are important for restraining Treg differentiation, whereas cDC-derived paracrine production of CCL3 appears rather redundant.

Figure 5. CCL17-CCR8-CCL3 axis critically interferes with Treg differentiation.

(a) Scheme of co-culture experiment, where isolated splenic CD4+CD62L+ T cells from CCR8WTApoe-/- or CCR8KOApoe-/- mice were combined with sorted CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs from LN of CCR8WTApoe-/- mice and cultured for 3 days in absence or presence of recombinant murine CCL17 (100 ng/ml); (b) CCL3 concentrations were measured in cell supernatants by ELISA (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=7, 9, 6, 9); (c) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs were quantified using flow cytometry analysis (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=10, 12, 10, 13); (d) Scheme of co-culture experiment, where isolated splenic CD4+CD62L+ T cells from CCR8WTApoe-/- or CCR8KOApoe-/-mice were combined with sorted CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs from LN of Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice and cultured for 3 days; (e) CCL3 concentrations in the supernatant were determined by ELISA (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=6, 5, 4, 6); (f) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs were quantified by flow cytometry (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=8,13, 4, 6); (g) Scheme of co-culture experiment, where splenic CD4+CD62L+ T cells isolated from Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice were combined with sorted CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs from LN of Apoe-/- mice and cultured for 3 days; (h) CCL3 concentrations in the supernatant were determined by ELISA (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right n=5, 6, 5, 6); (i) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs were quantified by flow cytometry (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right n=6, 5, 6, 5). (a-i) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values as indicated versus respective controls and as analyzed by two-way ANOVA (b,c,e,f,h,i) with Holm-Šídák’s post hoc test.

Next, CD4+CD62L+ T cells sorted from Ccr8WTApoe-/- or Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice were co-cultured with CCL17-competent or CCL17-deficient cDCs for 3 days (Fig. 5d). Combining CCR8-competent naïve T cells with CCL17-deficient as compared to CCL17-competent cDCs reduced CCL3 levels, while co-cultures with CCR8-deficient naïve T cells showed lower CCL3 levels with either CCL17-competent or CCL17-deficient cDCs (Fig. 5e). This was accompanied by inverse changes in Treg numbers, which were elevated in the presence of CCL17-deficient cDCs or using CCR8-deficient CD4+ T cells independent of CCL17 (Fig. 5f). To verify the requirement for T cell-derived CCL3, we co-cultured CD4+CD62L+ T cells from CCL3-competent or CCL3-deficient mice with CCR8-competent cDCs in the absence and presence of CCL17 for 3 days (Fig. 5g). CCL3 release was induced by CCL17 compared to baseline in CCL3-competent T cells and abolished in co-cultures with CCL3-deficient CD4+ T cells, where background CCL3 secretion from cDC was less sensitive to CCL17 (Fig. 5h). The number of Tregs in co-cultures of cDCs with CCL3-deficient CD4+ T cells was increased, as compared to controls, and remained higher and not diminished upon addition of CCL17 (Fig. 5i). Together, our data demonstrate that CCL17 interaction with CCR8, particularly on CD4+ T cells, is critical in mediating CCL3 secretion and restraining Treg differentiation.

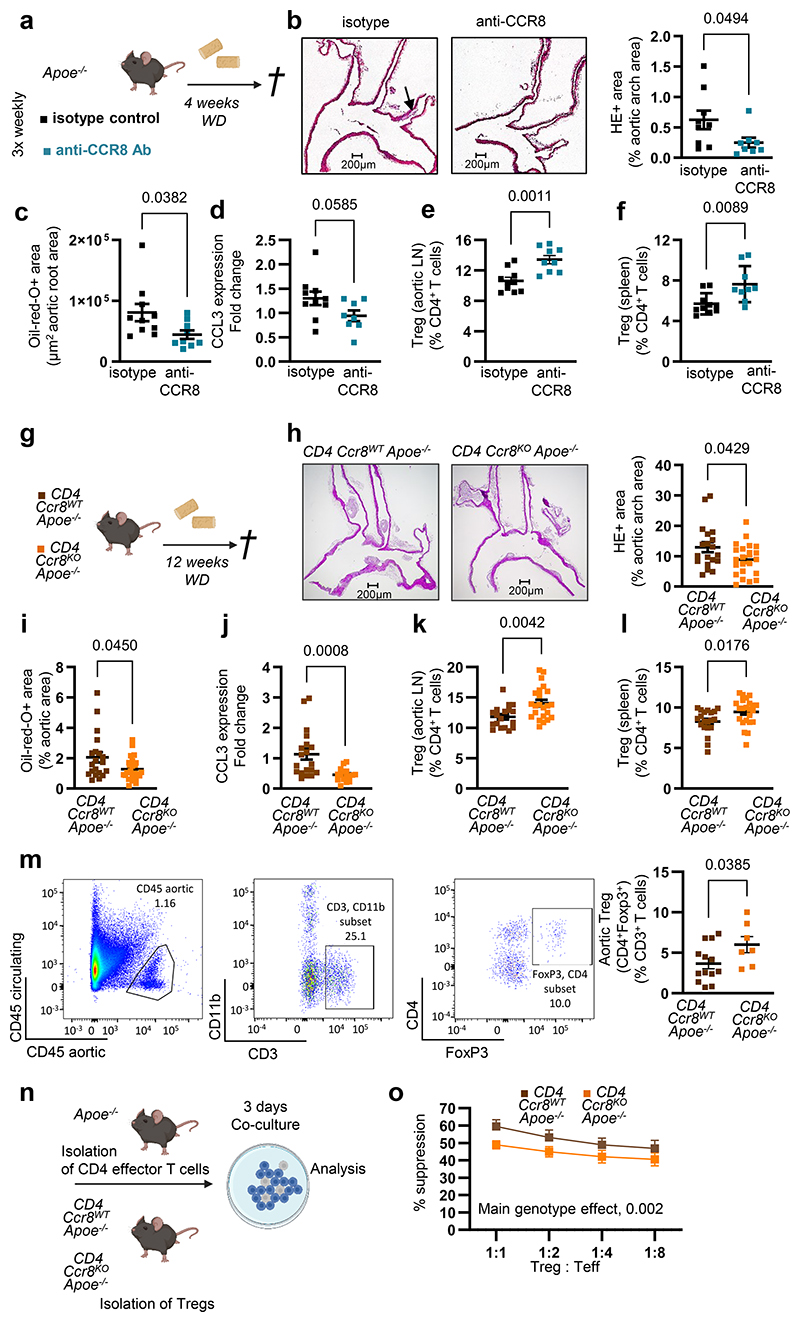

Atheroprotection by blockade or CD4-specific deletion of CCR8

To test whether CCR8 inhibition affects in vivo Treg numbers and atherosclerosis, we injected a blocking antibody to CCR8 or isotype control 3-times weekly into Apoe-/- mice receiving WD for 4 weeks (Fig. 6a). Atherosclerotic lesion size in aortic roots and arches was reduced (Fig. 6b-c), while lesional macrophage, SMC and collagen content was unaltered in anti-CCR8-treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 5f-i). Accordingly, CCL3 expression was reduced, whereas FoxP3+CD25+ Treg numbers was elevated in para-aortic LNs and spleens of anti-CCR8-treated mice (Fig. 6d-f), and lipid levels, circulating leukocyte and thrombocyte counts remained unaltered (Supplementary Table 4). Atherosclerotic lesion size in aortic root, thoracic-abdominal aorta and aortic arch was decreased in Ccr8KOApoe-/- versus Ccr8WTApoe-/- mice fed a WD for 12 weeks (Extended Data Fig. 6a-d). Because our in vitro data indicated a role of CCR8 on CD4+ T cells in controlling Treg differentiation, we generated CD4CreCcr8flox/floxApoe-/- mice (CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/-) lacking CCR8 in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6g). Compared to CD4Cre-Ccr8flox/floxApoe-/- (CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/-) controls, we found a reduced atherosclerotic lesion burden in the aortic arch and thoraco-abdominal aorta after 12 weeks of WD (Fig. 6h-i). Lesional content of macrophages, SMCs and collagen was unaltered, CCL3 expression in LNs was reduced, while Treg numbers were increased in para-aortic LNs and spleens but not in blood and thymus of CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice (Fig. 6e-l; Supplementary Table 5). As Helios is a marker distinguishing thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ Tregs27, we quantified CD4+FoxP3+Helios+ Tregs in aortic LNs, blood and thymus of CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/-and CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- mice but did not observe any differences (Supplementary Table 5). Yet, flow cytometry analysis of aortic cell suspensions revealed increased CD4+FoxP3+ Treg numbers in the aorta of CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- versus control mice after 12 weeks of WD (Fig. 6m), whereas the suppression capacity of CCR8-deficient Tregs was reduced compared to CCR8-competent Tregs (Fig. 6n,o). These data indicate that the CCL17-CCR8-CCL3-CCR1 axis affects Treg numbers directly at sites of inflammation (Fig. 6m) and in aortic LNs (Fig. 6k) rather than in blood and thymus. Lipid levels, circulating leukocyte and platelet counts, other T-cell subsets in blood, spleen, aortic and axillary LNs did not differ in CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/ versus control mice (Supplementary Table 6), except a reduction of naïve CD44-CD62L+ T cells in aortic LNs, reciprocating increased Treg frequencies (Supplementary Table 7; Fig. 6k). This corroborates a crucial role for CCR8 on CD4+ T cells in conferring atherogenic effects of CCL17 via CCL3 release and Treg suppression.

Figure 6. CCR8 blocking or CD4+ T cell-specific CCR8 deficiency reduce atherosclerosis and increase Tregs.

(a) Experimental scheme of Apoe-/- mice fed a Western-diet (WD) and injected 3-times weekly with a blocking antibody to CCR8 or isotype control; (b) Representative images and quantification of atherosclerotic lesion size after H&E-staining in aortic arches of Apoe-/- mice (isotype, n=9; anti-CCR8, n=8). Scale bar = 200 µm; (c) Lesion area after Oil-Red-O staining (ORO) in aortic roots of Apoe-/- mice (isotype, n=10; anti-CCR8, n=9); (d) CCL3 mRNA expression levels in LNs of Apoe-/- mice. 18sRNA was used as a housekeeping gene and changes in expression are given as fold-change calculated with the 2 –ΔΔCt method (isotype, n=10; anti-CCR8, n=8); (e,f) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+Tregs in para-aortic LNs (e) and spleens (f) of Apoe-/- mice (isotype, n=10; anti-CCR8, n=9); (g) Experimental scheme of CD4Cre- Ccr8flox/floxApoe-/- (CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/-) and CD4Cre+Ccr8flox/floxApoe-/- (CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/-) mice fed a WD; (h) Representative images and quantification of lesion area after H&E-staining in the aortic arches of CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- (n=19) or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- (n=22) mice. Scale bar = 200 µm; (i) Atherosclerotic lesion size after ORO in aortas of CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- (n=20) or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/ (n=22) mice; (j) CCL3 mRNA expression levels in LNs of CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- (n=19) or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- (n=16) mice. 18sRNA was used as a housekeeping gene and changes in expression are given as fold change calculated with the 2 –ΔΔCt method; (k,l) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+Tregs in para-aortic LNs (n=18 or 23) (k) and spleen (n=20 or 23) (l) of CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- (k, n=18; l, n=20) or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- (k,l n=23 each) mice; (m) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD4+FoxP3+ Treg in aortic cell suspensions from CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- (n=13) or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- (n=7) mice fed a WD; (n) Experimental scheme of a Treg suppression assay conducted with Apoe-/- CD4 effector T cells or Tregs from CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- mice; (o) Capacity of CD4Ccr8WTApoe-/- or CD4Ccr8KOApoe-/- Tregs to suppress CD4+ effector T-cell proliferation at varying Treg/Teff ratios (n=2 replicates for each dilution over 6 independent experiments); (a-o) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values as indicated and as analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test (b,I,j,m), unpaired Student’s t test (c,d-f,h,k,l), or a generalized linear model and Wald test for main model effects (o).

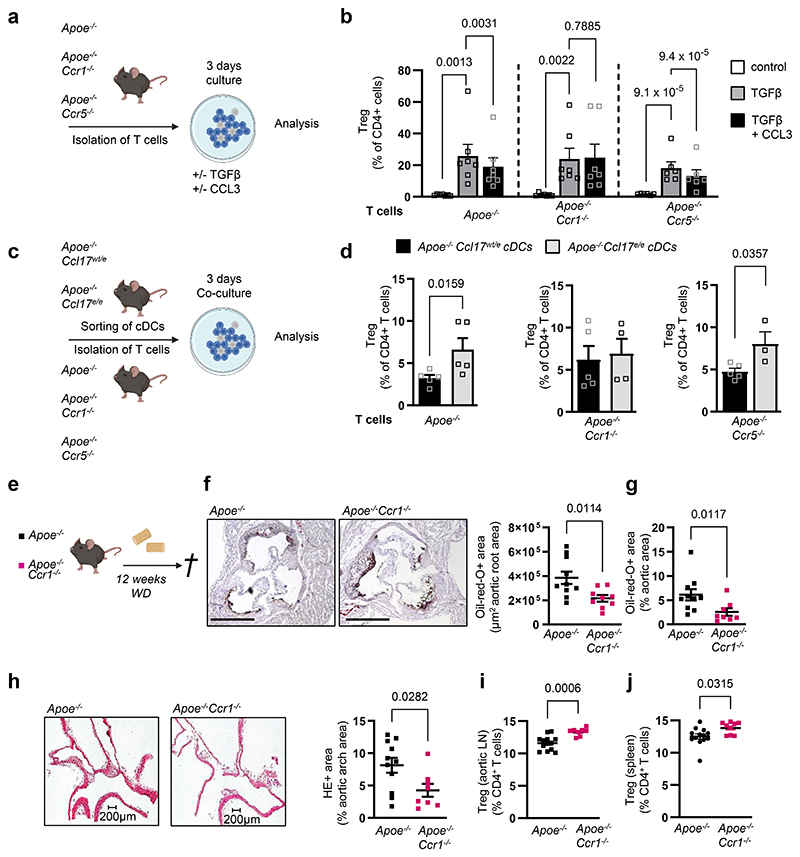

CCL17-driven CCL3 release limits Treg differentiation via CCR1

To explore which CCL3 receptor (CCR1 or CCR5) expressed on CD4+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 6k,l) mediates the effects of CCL17-induced CCL3 release, we cultured CD4+CD62L+ T cells from spleens of Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- mice under Treg-polarizing conditions with or without CCL3 (Fig. 7a). Flow cytometry analysis revealed a decrease in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg frequencies among CD4+ T cells, when comparing CCL3-treated Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- T cell cultures to controls (TGFβ only), while this did not occur in Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- T cells (Fig. 7b), indicating that CCL3 restrains CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg differentiation via CCR1. Evaluating the frequency of CD4+FoxP3+Tbet+ cells (as a subset with pro-atherogenic functions28) in LNs of CCL17- and CCL3-deficient mice, we observed a reduction of these cells in absence of CCL17 or CCL3 (Extended Data Fig. 6m). To confirm a role of the CCL3-CCR1 axis in mediating effects of CCL17, we sorted eGFP+ cDCs from Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e (CCL17-competent) or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (CCL17-deficient) mice for co-culture with naïve CD4+CD62L+ T cells from Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- mice (Fig. 7c). Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e DCs reduce CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg frequencies in co-culture with Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- but not Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- T cells, establishing the importance of a CCL17-instructed CCL3-CCR1 axis in restraining Treg differentiation (Fig. 7d). As compared to controls, lesion size in the aortic root, arch and thoraco-abdominal aorta was reduced, lesional SMC content was increased, macrophage and collagen content were unaltered in Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- mice (Fig. 7e-h; Extended Data Fig. 7a-d). While CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs were elevated in para-aortic, axillary and inguinal LNs and spleen of Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- mice, CCL3 plasma levels (Fig. 7i,j; Extended Data Fig. 7e-g), lipid levels, blood cell counts were unaltered (Supplementary Table 8). Our data are in line with reduced lesion size in Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- mice after 4 weeks of WD.29

Figure 7. CCL17-dependent CCL3 release controls Treg differentiation via CCR1.

(a) Experimental scheme wherein CD4+CD62L+ T cells isolated from spleens of Apoe-/-, Apoe-/- Ccr1-/-or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- mice were cultured for 3 days under Treg-polarizing conditions (TGFβ at 100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of recombinant mouse CCL3 (100 ng/ml); (b) Quantification of CD45+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 6, 6, 6) using flow cytometry; (c) Scheme of co-culture experiment wherein CD4+CD62L+ T cells isolated from spleens of Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccr1-/-or Apoe-/-Ccr5-/- mice were combined with sorted CD45+CD11c+MHCII+eGFP+ cDCs from LNs of Apoe-/-Ccl17wt/e or Apoe-/- Ccl17e/e mice and cultured for 3 days; (d) Quantification of CD45+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs (number of independent experiments per bar from left to right: n=5, 5, 5, 4, 5, 3) using flow cytometry; (e) Experimental scheme of Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- mice fed a WD for 12 weeks (e-j); (f) Representative images and quantification of lesion area after Oil-Red-O staining for lipid deposits in the aortic root of Apoe-/- (n=10) or Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- (n=9) mice. Scale bar = 500µm; (g) Quantification of lesion area after Oil-Red-O staining for lipid deposits in the thoraco-abdominal aorta of Apoe-/- (n=10) or Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- (n=8) mice; (h) Representative images and quantification of atherosclerotic lesion size in aortic arches of Apoe-/- (n=11) or Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- (n=8) mice after H&E staining; (i, j) Flow cytometric quantification of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in para-aortic LNs (i) and spleen (j) of Apoe-/- (i,j, n=13 each) or Apoe-/-Ccr1-/- (i, n=8; j, n=9) mice; (a-j) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values as indicated and as analyzed by mixed-effect regression model followed by pairwise contrasts for fixed factors corrected by Holm-Šídák’s procedure (b), unpaired Student’s t test (d,f,i), or Mann-Whitney U test (g,h,j).

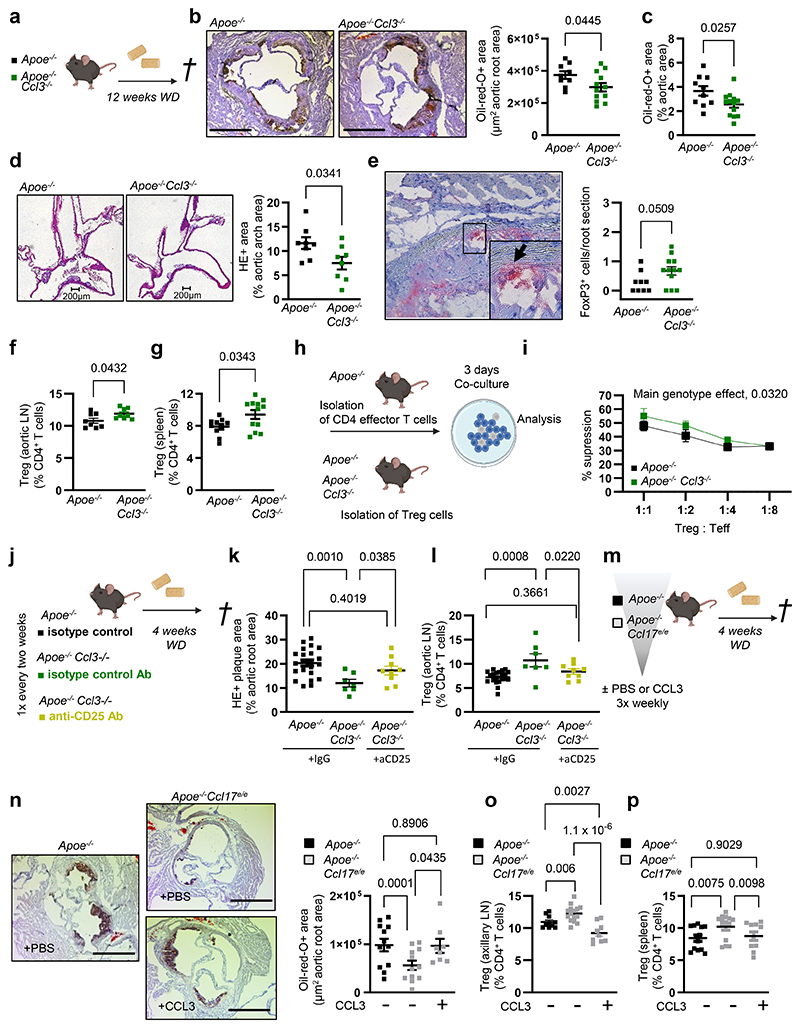

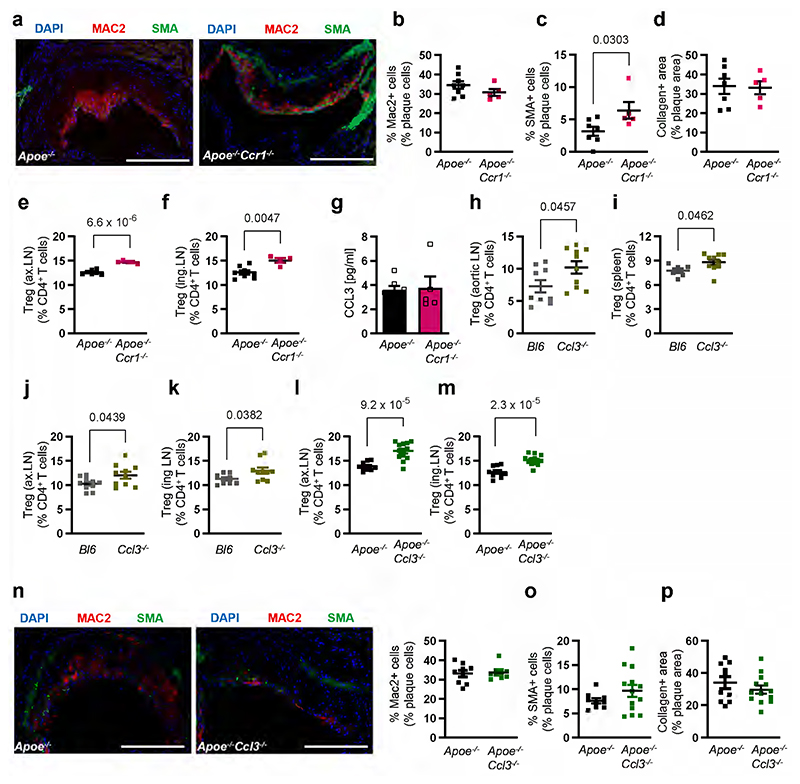

CCL3 confers atherosclerosis and reduced Treg numbers in vivo

Under steady-state conditions, we found an increase in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs among CD4+ T cells in para-aortic, axillary and inguinal LNs and spleen of Ccl3-/- mice as compared to wild-type controls (Extended Data Fig. 7h-k). A pro-atherogenic role of hematopoietic CCL3 was evidenced by protection in Ldlr-/- mice bearing CCL3-deficient BM cells.30 Similar to CCL17-deficient mice, Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice displayed a marked reduction in lesion size in the aortic root, arch and thoraco-abdominal aorta (Fig. 8a-d), elevated FoxP3+ cells in aortic root lesions (Fig. 8e) and an increase in Treg numbers in aortic, axillary or inguinal LNs and spleen, when compared to controls (Fig. 8f,g; Extended Data Fig. 7l,m). The suppression capacity of Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- Tregs in a 3-day assay with CD4+ effector T cells from Apoe-/- mice was enhanced (Fig. 8h,i). The lesional content of macrophages, SMCs and collagen (Extended Data Fig. 7n-p), body weight, lipid levels, and blood cell counts (Supplementary Table 9) were unaltered in Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- versus control mice.

Figure 8. CCL3 drives atherosclerosis and mediates reduced Treg numbers in vivo.

(a) Experimental scheme; (b,c) Representative images and quantification of lesion area after Oil-Red-O staining (ORO) in aortic roots of Apoe-/- (n=9) or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (n=12) mice. Scale bar = 500 µm; (c) Quantification of lesion area after ORO in the thoraco-abdominal aorta of Apoe-/- (n=10) or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (n=12) mice; (d) Representative images (scale bar = 200 µm) and quantification of lesion area after H&E staining of aortic arches from Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice (n=8 each); (e) Representative image and immunohistochemical quantification of lesional FoxP3+ cell numbers in aortic roots of Apoe-/ -(n=9) or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (n=12) mice; (f,g) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in para-aortic LNs (f) and spleen (g) of Apoe-/- (f, n=8; g, n=10) or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (f, n=8; g, n=12) mice; (h) Experimental scheme of Treg suppression assays with Apoe-/- CD4+ effector T cells; (i) Capacity of Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- Tregs to suppress CD4+ T-cell proliferation at varying Treg/Teff ratios (n=6 each); (j) Experimental scheme of Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice injected twice with isotype control or anti-CD25 antibody for Treg depletion; (k) Lesion quantification in aortic roots of isotype control-treated Apoe-/- (n=22), Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (n=7) or anti-CD25-treated Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice (n=9); (l) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in para-aortic LNs of isotype control-treated Apoe-/- (n=21), Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- (n=7) or anti-CD25-treated Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice (n=9); (m) Experimental scheme of Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice injected 3-times weekly with PBS or recombinant mouse CCL3 (20 µg i.p.); (n) Representative images and quantification of lesion area after ORO in aortic roots of PBS-treated Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (n=12 each) or CCL3-treated Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (n=8) mice. Scale bar = 500 µm; (o,p) Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in para-aortic LNs (o) and spleen (p) of PBS-treated Apoe-/- (o, n=10; p, n=13) or Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e (o, n=15; p, n=14) or CCL3-treated Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice (o, n=9; p, n=10).; (a-p) Data represent mean±SEM. Two-sided P values were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test (b-g), a generalized linear model and Wald test for main model effects (i), or a generalized linear model with mixed effects and post hoc pairwise contrasts within fixed factors corrected by step-down Holm-Šídák’s procedure (k-p).

To establish that atheroprotective effects of CCL3 deficiency were mediated by Tregs, we depleted CD25+ cells in Apoe-/-Ccl3-/ mice using an antibody to CD25. As compared to isotype control, treatment of Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice with anti-CD25 antibody increased lesion size in the aortic root and decreased Treg frequencies in aortic LNs, restoring the levels to those observed in isotype control-treated Apoe-/- mice (Fig. 8j-l). Body weight, lipid levels, and blood cell counts were unaltered in these mice (Supplementary Table 10). We next tested whether supplementing Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice with CCL3 would reinstate the phenotype of CCL17-competent mice (Fig. 8m). Injection of CCL3 (3-times weekly) into Apoe-/-Ccl17e/e mice during 4 weeks of WD increased aortic root lesion size and reduced axillary and splenic Treg numbers to levels seen in Apoe-/- controls (Fig. 8n-p). Body weight, lipid levels, and blood cell counts were unaltered (Supplementary Table 11). Our data demonstrate the importance of CCL3 in restraining Tregs and promoting atherosclerosis.

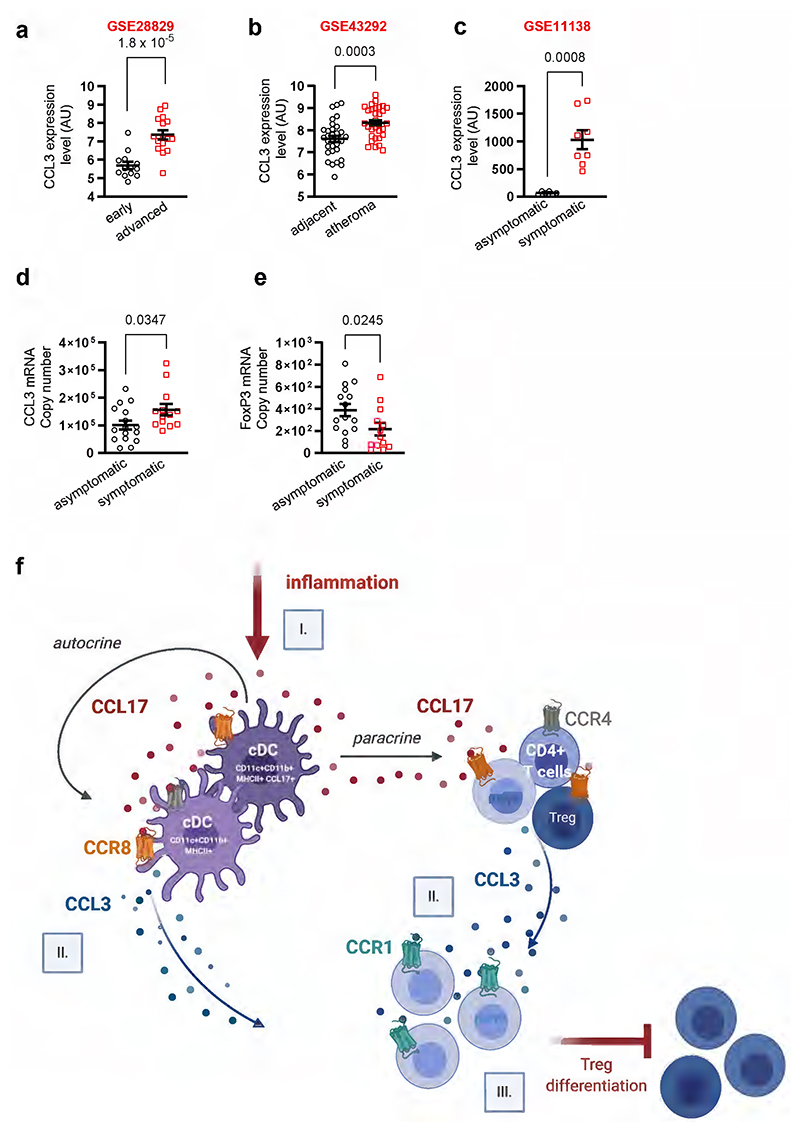

Proof-of-principle analysis in human gene expression data sets revealed higher CCL3 levels in atherosclerotic carotid artery segments with advanced (thick or thin fibrous cap atheroma) versus early lesions (intimal thickening or xanthoma) (Extended Data Fig. 8a, GSE28829) or in carotid atheroma specimens (stage IV) containing plaque core and shoulders versus remote, macroscopically intact tissue (stages I/II) (Extended Data Fig. 8b, GSE43292). We found increased CCL3 expression in human coronary arteries with atherosclerotic lesions from symptomatic as compared to asymptomatic patients with coronary artery disease (Extended Data Fig. 8c, GSE11138). Likewise, CCL3 transcript levels were higher in carotid atherectomy specimens from symptomatic patients (characteristics in Extended Data Table 2) with ipsilateral neurological events, e.g., transient ischemic attacks (n=16), than in those from asymptomatic patients (n=13) (Extended Data Fig. 8d). This was mirrored by lower FoxP3 expression indicative of reduced Treg abundance (Extended Data Fig. 8e). These data confirm increased CCL3 levels in progressing human lesions and imply a role in suppressing Treg differentiation in humans.

Discussion

Our quest to disambiguate the mechanisms underlying effects of CCL17 in an atherogenic context uncovered that aortic LNs of CCL17-deficient mice contain more tolerogenic cDCs, which license atheroprotective Treg maintenance. In turn, mice lacking the canonical CCL17 receptor CCR4 failed to phenocopy the effects of CCL17 deficiency. Instead, we could identify CCR8 as a functional high-affinity CCL17 receptor expressed by cDCs, CD4+ T cells and Tregs. Further analysis established that CCL17-CCR8 interactions on CD4+ T cells facilitate CCL3 release, thereby suppressing Treg differentiation. Accordingly, interference with CCR8 by antibody blockade or CD4+ T cell-specific deletion blunted CCL3 levels and atherosclerotic lesion formation. Likewise, CCL3-deficiency attenuated lesion development and increased Treg numbers, whereas CCL3 applied in CCL17-deficient mice worsened atherosclerosis and hindered Treg differentiation, an effect that was dependent on CCR1. We found increased CCL3 expression and reduced FoxP3 levels in human plaques versus healthy arteries and in symptomatic versus asymptomatic plaques.

CCR7 is a key receptor guiding cDCs into T-cell rich regions of lymphatic organs, enabling them to stimulate or suppress T-cell immunity.31 CCR7 has also been implicated in mediating egress of antigen-presenting cells from atherosclerotic lesions.32 We provide evidence that the CCR7-expressing DCs cluster in aortic LNs harbors both CCL17+ and CCL17-deficient cDC populations. In LNs from CCL17-deficient mice, the number of CCR7-expressing DCs with a tolerogenic gene expression profile was 2-fold higher than in controls. Hence, an increased number of tolerogenic cDCs together with locally decreased CCL3 levels might explain higher Treg frequencies in lymphoid organs of CCL17-deficient mice. This is consistent with the hypothesis that CCL17+ DCs regulate the homeostatic mechanisms of T cells, including Treg differentiation in lymphoid tissues, and are thereby able to affect the development of atherosclerosis.10 The involvement of Tregs in limiting chronic inflammation and immune responses in mouse models of atherosclerosis17,33 and in alleviating atherosclerosis-related diseases in humans34–36 is well documented.

It is remarkable that a deficiency of CCR4, conventionally considered as the sole CCL17 receptor, failed to recapitulate any experimental features associated with CCL17 deficiency in our models. These findings mirrored related reports in experimental models of atopic dermatitis19 and colitis11, where reduced inflammation was observed in CCL17-deficient but not CCR4-deficient mice. A similar discrepancy was evident in models of allograft tolerance, where CCR4-deficient mice fail to develop tolerance due to diminished Treg recruitment, whereas CCL17-deficient mice show prolonged allograft survival.13,37 Hence, we revisited the previously proposed but later contested concept22,25,38 that CCR8 may serve as an alternate CCL17 receptor and unequivocally establish that CCR8 indeed acts as a functional high-affinity receptor for CCL17. CCR8 is mainly expressed on CD4+ T cells and specifically on Tregs39,40 but also present on monocytes, NK cells, group 2 innate lymphoid cells and DCs, depending on disease context and tissue location.41–43 Whereas a role of CCR8 in cancer has received greeat attention44,45, reports on its contributions to chronic inflammation remain scarce. CCR8 has been implicated in airway inflammation46 and in promoting pathogenic functions of IL-5+ Th2 cells during atopic dermatitis47. A role of CCR8 in atherosclerosis has been addressed in a study showing that genetic deletion of CCL1 in Apoe-/- mice reduced Treg recruitment to inflamed arteries and increased lesion formation.48 In Ldlr-/- mice reconstituted with BM cells expressing FoxP3-driven red fluorescent protein, treatment with a CCR8-blocking antibody increased lesion size48, contrasting our findings likely due to different experimental set-ups. Whereas we used Apoe-/- mice for CCR8 blocking studies, the Ldlr-/- mice were subjected to BM transplantation48 and fed a cholesterol-rich diet for one week, an unusually short time span for evaluating the pathogenic role of adaptive immune cells in atherosclerosis. Yet, CCR8-expressing Tregs interacting with CCL1 have been identified as key drivers of suppressive immunity in models of autoimmune encephalomyelitis.24 We cannot exclude that CCL1-CCR8 interactions driving Treg recruitment contribute to atheroprotective effects in CCL17-deficient mice, nor that differences in receptor affinity or local availability of its ligands or biased signaling may shape anti- versus pro-inflammatory immune responses mediated by CCR8. In fact, both CCR8 ligands may be involved and differential levels in a given pathology may determine functional outcomes.

Expression of CCR8 was initially identified on human monocytes and lymphocytes.49 Mouse pre-B-cell transfectants (4DE4) expressing CCR8 dose-dependently migrated and exhibited specific calcium transients in response to CCL1 but not other chemokines tested (albeit not including CCL17).49 Subsequently, CCL17 was suggested to act as a functional CCR8 ligand, evidenced by a dose-dependent migration of Jurkat CCR8-transfectants towards CCL17.22 This was supported by a study revealing CCR8 expression and dose-dependent migration of human IL-2-activated NK cells (IANK) in response to CCL17.36 Whereas CCL1 induced a CCR8-dependent calcium flux in IANK cells, partially inhibiting CCL17-induced calcium flux, CCL17 fully desensitized the calcium response to CCL1. This discrepancy was explained by the expression of CCR4 on IANK cells, which cannot be desensitized by CCL1.41 Accordingly, other groups were unable to show migration, calcium flux or receptor internalization in CCR8-transfected 4DE4 cells in response to CCL17.38,50 This may be related to the fact that 4DE4 transfectants are a suboptimal model for signaling studies, whereas primary human IANK41 cells like CD4+ T cells used herein represent more physiological CCR8-bearing cell types. Still, calcium flux induced by CCL17 in IANK cells was predominantly mediated by CCR4.41 Given these inconsistencies, we applied assays beyond migration and receptor internalization, both of which documented CCL17 activity for CCR8, to confirm a functional high-affinity CCL17 interaction with CCR8. Proximity ligation in DCs or Jurkat CCR8-transfectants, SPR and binding competition revealed binding of CCL17 to CCR8 with apparent affinities ranging from 1.1 nM (KD SPR) to 9.4 nM (IC50 CCL1 competition), thus equivalent to that for CCL18 (KD 1.9 nM) but lower than that found for CCL1 by us (IC50 0.58 nM) and others (Ki/IC50 0.11-0.22 nM).50,51 Determining cAMP levels in CCR4- or CCR8-transfected HEK293 cells confirmed that CCL17 induced Gi-signaling via both receptors. This extends findings that CCR8 mediates chemotactic migration towards CCL17, unequivocally establishing that CCR8 as a signaling high-affinity receptor for CCL17. Our data can be reconciled with a report that CCL17 induced chemotaxis of Jurkat CCR8-transfectants, albeit without eliciting calcium mobilization.22 Findings disputing the assignment of CCL17 as a CCR8 ligand may have been due to insufficient bioactivity, as no positive controls were provided.22 A role of CCR8 in mediating the restraint of Treg homeostasis may thus serve to complement or counter-balance functions of CCR4 in Treg recruitment during inflammation and cancer.52,53 Preliminary evidence that CCR4 and CCR8 can engage in a heterodimeric interaction may further imply alternative mechanisms of modulation that will be subject of future studies. For instance, CCL17 inhibited Treg recruitment through biased activation of CCR4, activating Gq-signaling but inhibiting CCL22-stimulated β-arrestin signaling to explain the abundance of Tregs in injured myocardium of CCL17-deficient mice54, an effect possibly attributable to CCL17 activity mediated by CCR8.

It is tempting to speculate that only chronic inflammatory conditions, as present in atherosclerosis, atopic dermatitis19 or colitis11, foster the development of CCL17-expressing cDCs, which then trigger Treg restraint by inducing CCL3 release through CCR8 in lymphoid organs. Notably, our data show that it is primarily CCR8 on CD4+ T cells, which orchestrates the restraint of Tregs by up-regulating CCL3 in response to CCL17, as evident by decreased lesion size and increased Treg numbers in Apoe-/- mice lacking CCR8 on CD4+ T cells. Because CCR8 is prominently expressed in Tregs, it is conceivable that at sites of inflammation or in T-cell rich areas of LNs CCL17 directs Treg trafficking but also prevents Treg differentiation through induction of CCL3. This mechanism would explain why isolated CD25+CD4+ T cells secreted CCL3 in response to CCL17. Under chronic inflammatory conditions like atherosclerosis, however, CCL17+ cDCs are continuously present and skewing CD4+ T-cell responses towards a pro-inflammatory type. This concept is corroborated by mechanistic studies in psoriasis as a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease. The transcription factor Grainyhead-like 3 is crucial for maintaining barrier integrity of the skin, while its knockdown upregulates CCL17 in keratinocytes, driving their proliferation and an inflammatory T-cell infiltration pattern resembling psoriasis.55 Moreover, elevated CCL3 inversely correlates with FoxP3 levels in Tregs of psoriatic patients and CCL3 interferes with FoxP3 stability by promoting ubiquitination-dependent degradation.56 Psoriatic disease may thus be prompted by CCL17-induced CCL3 expression to impair FoxP3 stability and reduce Treg numbers. It will be intriguing to dissect whether CCL3 induction by CCL17 is restricted to cell types expressing CCR8, whether additional cell types are licensed by CCR8 expression to enact this mechanism of Treg control and which specific signaling pathways couple CCR8 to CCL3 release.

Prior evidence on the role of CCL3 in atherosclerosis, despite not pinpointing the cellular sources of CCL3, lends support to our findings. In Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Ccl3-/- BM, aortic lesion formation and inflammatory neutrophil adhesion was reduced; however, an involvement of T-cell subsets was not examined.30 Atorvastatin inhibits the 5-lipoxgenase pathway in Apoe-/- mice, thereby downregulating CCL3 expression and attenuating lesion development, to implicate CCL3 as a therapeutic target in atherosclerosis.57 Mice lacking CCL3 are also protected from aortic inflammation and aneurysm formation58. Here we show that genetic deletion of CCL3 in Apoe-/- mice reduced lesion size and increased Treg numbers, and depletion studies indicated that atheroprotection was mediated by Tregs. Probing CCL3 receptors, CCR5 deficiency conferred a protective phenotype in different mouse models of atherosclerosis59, whereas results on CCR1 deficiency were more ambiguous29,59. Our data demonstrate that Treg restraint by CCL3 is afforded by CCR1 and that CCR1 deficiency in Apoe-/- mice decreased lesion development and enhanced Treg numbers. Nevertheless, findings may be reconciled depending on the mouse model and disease phenotype, as CCR1 engages multiple other chemokine ligands. Thus, cell subsets interacting in the vicinity and the local tissue environment may determine the availability of CCR1 ligands and how CCL3 shapes the immune response at relevant interfaces.

In synopsis, our data establish that CCL17 binds to CCR8 as its second functional high-affinity receptor besides CCR4, and introduce CCL17, to the unique ligand spectrum of CCR8, including its major ligand CCL1, CCL847, a chemokine responsible for pathogenic circuits in atopic dermatitis and the widely expressed inflammatory chemokine CCL18.50 The functional relevance in primary cells, i.e. Tregs, unfolds another facet within the remarkable versatility of the chemokine-receptor family.60 Our data show that CCL17 signaling via CCR8 on CD4+ T cells triggers CCL3 secretion, which engages CCR1 and suppresses Treg differentiation to drive atherogenic effects of CCL17 (Extended Data Figure 8f). We propose that the specific instruction of CD4+ T cells by CCL17+ cDCs dictating a CCL3-dependent restraint of Tregs may constitute a broadly relevant mechanism in chronic inflammatory disease and identify the sequential CCL17-CCR8-CCL3-CCR1 pathway as a target for multilayered therapeutic intervention.

Methods

A detailed overview of used materials is provided in the Major Resources Table (Supplementary Table 12).

Mice

Ccr4-/- mice1 were kindly provided by K. Pfeffer (Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany) and Ccl17e/e (GFP reporter knock-in) mice2 were kindly provided by I. Förster (Universität Bonn, Germany). Ccl3-/- mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, USA). Ccr1-/- mice and Ccr5-/- mice were kindly provided by P.M. Murphy and W.A. Kuziel, respectively, and have been previously characterized.3,4 Ccr4-/-, Ccr1-/-, Ccr5-/-, Ccl17e/e and Ccl3-/- mice were crossed with Apoe-/- mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. Ccr8flox/flox mice were generated at Ozgene, backcrossed into a C57Bl/6 background and crossed with C57Bl/6 Apoe-/- mice in house. Apoe-/-UniCreErt2 (ubiquitous inducible Cre expression) as published before5 and CD4Cre (purchased from Jackson laboratory) bred to Apoe-/- were crossed in house with Apoe-/-Ccr8flox/flox mice to generate whole body or T cell-specific Ccr8 knock out mice, respectively. To induce Ccr8 deletion in UniCreErt2 mice the mice were injected i.p. with tamoxifen (50 mg/kg body weight, from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in Miglyol, Caelo) for 5 consecutive days. All strains were backcrossed for at least 10 generations to the C57Bl/6 background. All of the mice were housed under specific pathogen free conditions in 12 h/12 h light–dark cycles at 21°C and 50% humidity with ad libitum food and water. Depending on the type of study, mice were either fed a normal chow diet (steady state) or a Western Type diet (WD; for atherosclerosis studies) containing 21% fat and 0.15-0.2% cholesterol (Altromin 132010, Sniff TD88137) starting at 8-10 weeks of age for 4 or 12 weeks before sacrifice. For the rescue experiment using CCL3 injections, mice were injected 3x weekly with 20 µg recombinant mouse CCL3 or PBS control by intraperitoneal injection. For depletion of CD25+ cells including Tregs, Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- mice were fed a WD for 4 weeks and injected twice (every second week) with isotype control or anti-CD25 antibody (each 250 µg antibody per intraperitoneal injection). For the experiment using anti-CCR8 blocking antibody, mice were injected 3x weekly with 5 µg anti-CCR8 antibody or isotype control by intraperitoneal injection. For single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), male Ccl17wt/eApoe-/-, and Ccl17e/eApoe-/- mice were fed a normal chow diet or 6 weeks of WD. All experimental mice were sex- and age-matched. All experiments were approved by local authorities and complied with German animal protection law (Regierung von Oberbayern, Germany; ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-14-189, ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-18-96, ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-20-26). Every effort was made to minimize suffering.

Histology and immunofluorescence

Atherosclerotic lesion size was assessed by analyzing cryosections of the aortic root by staining for lipid depositions with Oil-Red-O. In brief, hearts with the aortic root were embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura) for cryo-sectioning. Oil-Red-O+ atherosclerotic lesions were quantified in 4 µm transverse sections and averages were calculated from 3 sections. The thoraco-abdominal aorta was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and opened longitudinally, mounted on glass slides and stained enface with Oil-Red-O. Aortic arches with the main branch points (brachiocephalic artery, left subclavian artery and left common carotid artery) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Lesion size was quantified after Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE)-staining of 4 µm transverse sections and averages were calculated from 3-4 sections. For analysis of the cellular composition or inflammation of atherosclerotic lesions, aortic root sections were stained with antibodies to Mac2 (Cedarline), smooth muscle actin (SMA, Dako) or FoxP3 (Abcam). Nuclei were counter-stained by 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI). After incubation with a secondary FITC- or Cy3-conjugated antibody (Life Technologies) for 30 minutes at room temperature, sections were embedded with VectaShield Hard Set Mounting Medium (Vector laboratories) and analyzed using a Leica DM4000B LED fluorescence microscope and charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. For FoxP3 staining, Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit, VECTASTAIN® ABC-AP and Vector® Red Substrate Kit were applied (all from Vector laboratories). Blinded image analysis was performed using Diskus, Leica Qwin Imaging (Leica Lt.) or Image J software. For each mouse and staining, 2-3 root sections were analyzed and the average was taken.

Laboratory blood parameters and flow cytometry

Whole blood from the mice was collected in EDTA-buffered tubes. Thrombocyte counts were determined using a Celltac Automated Hematology Analyzer (Nihon Kohden). Afterwards, samples were subjected to red-blood-cell lysis for further analysis using flow cytometry. Spleen and lymph nodes (LNs) were mechanically crushed and passed through a 30 μm cell strainer (Cell-Trics, Partec) using Hank’s Medium (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 0.3 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA; Gibco by life technologies) to obtain single cell suspensions. Leukocyte subsets were analyzed using the following surface marker combinations: neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+CD115-Gr1high), classical (CD45+CD11b+CD115+GR1high) and non-classical (CD45+CD11b+CD115+GR1low) monocytes, B cells (CD45+B220+), T cells (CD45+ CD3+). Regulatory T cells (Tregs) were classified as CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ (gating strategy used to identify Treg throughout the manuscript is depicted in Extended Data Figure 1J) and its subpopulation as CD45+CD3+CD4+FoxP3+Tbet+. Foxp3 transcription factor was stained using the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience). Annexin-V+ cells were analyzed using the Dead Cell Apoptosis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell populations and marker expression were analyzed using a FACSCanto-II, FACSDiva software v.8.0 (BD Biosciences) and the FlowJo analysis program v.10 (Tree Star Inc.).

All aortas, including the aortic root, aortic arch and thoracic portions were subjected to a house-made enzymatic digestion and post-digestion protocol6. Single cell suspensions were obtained by mashing aortas through a 70 μm cell strainer. Live/dead staining was performed with Zombie Violet™ Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423113) followed by surface staining with antibodies: anti-CD45-APC-Cy7 (Biolegend, clone 30-F11, 1:300), anti-CD11b-PerCP-Cy5.5 (Biolegend, clone M1/70, 1:300), anti-CD3e-FITC (Biolegend, clone 145-2C11, 1:300) and anti-CD4-PE-Cy7 (Biolegend, clone RM4-5; 1:500) including unconjugated anti-CD16/32 (Biolegend, clone 93, 1:500). Intracellular staining for FoxP3 was performed using anti-FoxP3-PE antibody (eBiosciences, clone FJK-16s, 1:50) and FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBiosciences, 00-5523-00) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Data were acquired using flow cytometry (BD FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences) and analyzed analyzed using Flowjo v.10 (Flowjo, LLC, Ashland, USA).

Plasma lipid levels

Cholesterol and triglyceride levels were analyzed using mouse EDTA-buffered plasma and quantified using enzymatic assays (c.f.a.s. cobas, Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and tolerogenic DC analysis

For the isolation of dendritic cells (DCs), LNs were mechanically crushed and passed through a 30 μm cell strainer (Cell-Trics, Partec) using Hank’s Medium (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 0.3 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA; Gibco by life technologies) to obtain single cell suspensions. Conventional DCs are isolated from this suspension by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria), by gating for CD45+CD11c+MHCII+ cells. Furthermore, eGFP+Ccl17wt/e and eGFP+Ccl17e/e DCs were isolated by gating for the endogenous eGFP signal in the FITC channel (pre-gating: CD45+CD11c+MHCII+). Flow cytometric analysis of tolerogenic DCs in aortic LNs was performed by pre-gating for CD45+CD11c+ MHCII+ followed by evaluation of CD83, CCR7, IDO, and CD274 on pre-gated cDCs.7–10

For the isolation of T and B cells, spleens were mechanically crushed and passed through a 30 μm cell strainer (Cell-Trics, Partec) using Hank’s Medium (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 0.3 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA; Gibco by life technologies) to obtain single cell suspensions. Cell subsets are isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria), by gating for CD45+CD3+ cells (T cells) or CD45+CD19+ cells (B cells). After sorting, all cells were cultured in 96 well round-bottom plates (1x105 cells/well) (Corning Costar by Sigma-Aldrich/Merck) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-Glutamine and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (all Gibco by Life technologies), unless stated otherwise, and with/without specific stimuli as indicated for the individual experiments.

Immunomagnetic cell isolation

For the isolation of monocytes and neutrophils, bone marrow cells were harvested by flushing femurs with Hank’s Medium (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 0.3 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA) (Gibco by life technologies). Monocytes are isolated using the mouse Monocyte Isolation Kit and a LS separation column (all Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Neutrophils are isolated using the mouse Neutrophil Isolation Kit and a LS separation column (all Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After isolation, all cells were cultured in 96 well round-bottom plates (1x105 cells/well) (Corning Costar by Sigma-Aldrich/Merck) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 2mM L-Glutamine and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (All Gibco by Life technologies) unless stated otherwise, with/without specific stimuli as indicated for the individual experiments.

For the isolation of CD4+, CD4+CD62L+ and CD4+CD25+ T cells, spleens were mechanically crushed and passed through a 30 μm cell strainer (Cell-Trics, Partec) using Hank’s Medium (Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 0.3 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA; Gibco by life technologies) to obtain single cell suspensions. CD4+ T cells are subsequently isolated using the mouse CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit and a LS separation column (all Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CD4+CD62L+ T cells are subsequently isolated using the mouse CD4+CD62L+ T cell Isolation Kit II and a LS separation column (all Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CD4+CD25+ T cells are subsequently isolated using the mouse CD4+CD25+ T cell Isolation Kit and a LS separation column (all Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After isolation, cells were cultured in 96 well round-bottom plates (1x105 cells/well) (Corning Costar by Sigma-Aldrich/Merck) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-Glutamine and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (all Gibco by Life technologies), unless stated otherwise, and with/without specific stimuli as indicated for the individual experiments.

For the isolation of human CD4+ T cells, 18 ml whole blood was harvested from healthy volunteers and mixed with 2 ml citrate to avoid blood coagulation (approved by the local ethics committee, LMU Munich, no. 18-283). Whole blood was then diluted with same volume of T cell isolation buffer (phosphate-buffered saline + 2 mmol/l EDTA + 0.1% BSA; Gibco by life technologies) and gently layered over 2-fold volume of Biocoll solution (1.077 g/ml; Bio&SELL), followed by centrifugation for 25 minutes at 600 g without brake. The top layer of plasma was removed and mononuclear cells in the middle layer were carefully harvested and transferred to a new tube. The mononuclear cells were washed with T cell isolation buffer twice and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 300 g. The supernatants were discarded, and cell pellets were resuspended with T cell isolation buffer to reach a final density of 1×108 cells/ml. Human CD4+ T cells were isolated from this cell suspension with Dynabeads™ Untouched™ Human CD4 T Cells Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Transmigration assay

Mouse and human CD4+ T cells were isolated according to manufacturer’s protocols as detailed above.

Transmigration assays were performed using HTS Transwell-96 well plate (3.0 μm pore size with polycarbonate membrane; Corning). Murine or human recombinant CCL17 (Biolegend) were added to bottom chambers at a concentration of 100 ng/mL or as indicated in RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.5% BSA. Murine or human recombinant CCL1 or CCL22 (Peprotech) were added to bottom chambers at a concentration of 50 ng/mL or as indicated in RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.5% BSA. Mouse CD4+ T cells from Apoe-/-, CCR8WTApoe-/- or CCR8KOApoe-/- mice or human CD4+ T cells (1x105) were added to the top chamber in the presence or absence of CCR4 receptor antagonist C 021 dihydrochloride (Tocris) at a concentration of 0.5 µM; or human CD4+ T cells (1x105) were pretreated with or without anti-CCR8 antibody (R&D Systems) and added to the top chamber and allowed to migrate for 3 hours. The number of cells migrated was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v.10 software (Tree Star Inc.). The chemotactic index was calculated as the ratio of chemokine-stimulated to unstimulated migration.

In another quantitative transmigration assay (checkerboard), HTS Transwell-96 well plates (3.0 μm pore size with polycarbonate membrane; Corning) were also used. Isolated CD4+ T Cells (1×105) were added to the upper chamber of each well in a total volume of 80 μl of RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.5% BSA. Murine recombinant CCL17 (Biolegend) was used at concentrations of 1 µg/ml, 100 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml, 1 ng/ml or 0 ng/ml in RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.5% BSA in the lower, upper, or both lower and upper chambers of the Transwell to generate ‘checkerboard’ analysis matrix of positive, negative, and the absent gradients of CCL17, respectively. Cells were collected from the lower chamber 3 h later and counted. The number of cells migrated was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v.10 software (Tree Star Inc.). The chemotactic index was calculated as the ratio of migrated cell counts of each well to unstimulated migration without murine recombinant CCL17 in both lower and upper chamber.

T effector polarization assay

Splenic CD4+CD62L+ T cells were obtained by immunomagnetic cell isolation as described previously. CD4+CD62L+ T cells (1×105) were cultured in 96-well tissue round bottom culture plates in the presence of anti-CD3e (pre-coated overnight, 5µg/ml), anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml) and supplemented with TGF-β (5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of CCL17 (100 ng/mL) for 3 days. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) were classified as CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+, The number of Treg cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v.10 software (Tree Star Inc.).

Treg suppression assay

Splenic CD4+CD25- T cells and CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) from Apoe-/-, Apoe-/-Ccl3-/- or CCR8KOApoe-/- were isolated using CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-091-041) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated CD4+CD25- T cells were labelled with 5 µM Cell Proliferation Dye eFluor™ 670 dye (eBioscience™, 65-0840-90) according to manufacturer´s instructions and co-cultured with different concentrations of CD4+CD25+ Tregs and with Dynabeads™ Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11456D) for 72 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Proliferation of CD4+CD25- T cells was assessed by flow cytometry (BD FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using Flowjo v.10 (Tree Star Inc.).

Co-culture experiments

DCs were isolated from cell suspension from lymph nodes by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria), by gating for CD45+CD11c+MHCII+ cells as aforementioned. Sorted DCs were subsequently co cultured for 3 days in 96-well tissue flat bottom culture plates with splenic naïve CD4+CD62L+ T cells obtained by immunomagnetic cell isolation as described previously in a DC:T cell ratio of 1:2 (in general 2.5x104 : 5x104 cells), with/without specific stimuli as indicated for the individual experiments. The percentage of regulatory T cells (CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells) relative to CD4+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v.10 software (Tree Star Inc.). Supernatants were collected for further ELISA or Multiplex-bead-array analysis.

Cell culture experiments for CCL3 release

To measure CCL3 release of CD4+, CD4+CD62L+, CD4+CD25+, CD45+CD11c+MHCII+, eGFP+Ccl17wt/e DCs, eGFP+Ccl17e/e DCs CD45+CD3+ cells (T cells) or CD45+CD19+ B cells and monocytes as well as neutrophils cells were seeded at 1x105 into a 96 well round bottom plate and incubated in absence or presence of CCL17 (100 ng/ml) in combination with C021 (5 µM) or anti-CCR8 antibody (2 µg/ml) for 4 h. Thereafter, supernatants were harvested and measured by CCL3 ELISA as detailed below.

Multiplex-bead-array

Cell culture supernatants and mouse plasma were analyzed for various cytokines using the “Cytokine & Chemokine 26-Plex Mouse ProcartaPlex™ Panel 1” (Thermo Fisher Scientific (eBioscience)), sample preparation and analysis were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The kit allows the simultaneous detection and quantification of soluble murine IFNγ; IL-12p70; IL-13; IL-1β; IL-2; IL-4; IL-5; IL-6; TNFα; GM-CSF; IL-10; IL-17A; IL-18; IL-22; IL-23; IL-27; IL-9; GRO-α (CXCL1); IP-10 (CXCL10); MCP-1 (CCL2); MCP-3 (CCL7); MIP-1α (CCL3); MIP-1β (CCL4); MIP-2 (CXCL2); RANTES (CCL5); Eotaxin (CCL11). The bead-based assay follows the principles of a sandwich immunoassay. Fluorescent magnetic beads are coupled with antibodies specific to the analytes to be detected. Beads are differentiated by their sizes and distinct spectral signature (color-coded) by flow cytometry using the Luminex™ xMAP, data were collected with the xPONENT software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, v.4.2), and analyzed with the ProcartaPlex Analyst software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, v.1.0).

ELISA

CCL3 plasma (EDTA-plasma of full blood) levels or CCL3 levels in cell culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA using a commercially available kit (CCL3 Mouse Uncoated ELISA Kit with Plates from Thermo Fisher Scientific or Mouse CCL3/MIP-1 alpha Quantikine ELISA Kit by R&D System) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The final measurement of absorbance was carried out using a plate reader (Tecan) set to 450 nm with a correction factor of 550 nm.

Cyclic AMP signaling

Levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) were measured in confluent Flp-In system and Flp-In™ TREx-293 (HEK293) cells (Invitrogen). HEK293 cells were transfected using plasmids harboring sequences of CCR4 and CCR8 (Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center, www.cdna.org). The sequence of the luciferase-cAMP binding site fusion protein from the pGloSensor™-20F-vector (Promega) was amplified and ligated into a bicistronic pIRESneo vector (Clontech) to obtain the reporter gene plasmid. HEK293 cells were transfected with the reporter gene vector using Eco-Transfect (OZBioscience), stable clones were selected as host cell lines for expressing receptor constructs using the Flp-In system11 and reselected with G418 and hygromycin B. After incubation with luciferin-EF (2.5 mM, Promega) at room temperature for 2 h, cells were stimulated with CCL17, CCL1 or CCL20 (100 ng/ml each) or left unstimulated (PBS control) and luminescence indicating the reduction of cAMP was recorded over time.

Proximity ligation assay

Proximity ligation was carried out using the Duolink In Situ Red Kit Goat/Rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich) on PFA fixated mouse dendritic cells cultured on collagen-coated cover slips which were pre-incubated with recombinant mouse CCL1 (Peprotech) and CCL17 (Biolegend) using primary polyclonal antibodies to mouse CCL17 (R&D systems), mouse CCL1 (Acris), mouse CCR4 (Thermo Scientific), mouse CCR5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse CCR8 (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Imaging was performed using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DM4000) after which deconvolution algorithms for wide field microscopy were applied to improve overall image quality (Huygens professional 16.10; SVI). The number of Duolink detected interactions was determined in the processed images using the Leica LAS 4.2 analyses software. In order to more accurately resolve the interactions detected with Duolink, representative DC samples of each condition were also visualized with a Leica SP8 3X microscope using a combination of 3D confocal microscopy (DAPI) and 3D STED nanoscopy (Duolink Red). Image processing and deconvolution of the resultant 3D datasets was performed using the Leica LAS X and Huygens professional software packages.

Proximity ligation was also carried out using the Duolink In Situ Probe anti-Goat or anti-Rabbit or anti-mouse Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) on PFA fixated CCR4-transfected or CCR8-transfected Jurkat cells (ATCC) which were pre-incubated with or without recombinant human CCL1 (Peprotech) and CCL17 (Biolegend) using primary polyclonal antibodies against human CCL17 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), human CCL1 (R&D Systems), human CCR4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific or Biolegend) and human CCR8 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were then treated with ligase and polymerase according to the manufacturer’s instructions of Duolink flowPLA Detection Far Red kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The fluorescent signal was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v.10 software (Tree Star Inc.).

Expression, purification and labeling of CCL17