Abstract

Diversity in the biochemical workhorses of the cell—that is, proteins—is achieved by the innumerable permutations offered primarily by the 20 canonical L-amino acids prevalent in all biological systems. Yet, proteins are known to additionally undergo unusual modifications for specialized functions. Of the various post-translational modifications known to occur in proteins, the recently identified non-disulfide crosslinks are unique, residue-specific covalent modifications that confer additional structural stability and unique functional characteristics to these biomolecules. We review an exclusive class of amino acid cross-links encompassing aromatic and sulfur-containing side chains, which not only confer superior biochemical characteristics to the protein but also possess additional spectroscopic features that can be exploited as novel chromophores. Studies of their in vivo reaction mechanism have facilitated their specialized in vitro applications in hydrogels and protein anchoring in monolayer chips. Furthering the discovery of unique canonical cross-links through new chemical, structural, and bioinformatics tools will catalyze the development of protein-specific hyperstable nanostructures, superfoods, and biotherapeutics.

Keywords: hyperstable structures, novel protein function, side chain modification, unusual cross-link

1. Introduction

Proteins are polymeric biologicals, comprising one or more chains of amino acids that serve as their building blocks. Proteins serve as the workhorses of all biological systems, and play indispensable roles in every known biochemical, functional, and structural process. Primarily known for their function as enzymes that catalyze nearly all biochemical reactions, proteins also provide mechanical support in muscles, have structural roles in cytoskeletal organization, and are vital for cell-cell signaling, immune response, cell adhesion, and regulating the cell cycle. How a protein functions depends largely on its structure, how it folds into a unique tertiary scaffold, and how it interacts to form quaternary assemblies,1,2 all of which rely on the protein's primary sequence. Proteins rely on several elements to effectively perform their function and their timed regulation, including coenzymes and cofactors, protein−protein interactions, differential expression levels and their cellular lifetimes (proteostasis), and post-translational modifications.

The recent surge in characterization of protein complexes and protein machinery using high-resolution structural biology (e.g., cryoEM and AI-based methodologies) and mass spectrometry (large scale top-down and bottom-up proteomics) has led to the identification of several post-translational modifications in proteins.3–7 These modifications include the formation of covalent bonds between amino acids, which occur post-translationally.8 The resultant covalent bond can affect the structure in three ways: stabilize it, destabilize it, or not have any effect. The phenomenon of cross-linking is not new, and has been previously been applied to generate highly specialized structures such as hydrogels.9–11 Cross-linking has been identified and implicated primarily in aging, which involves the accumulation of physiological changes in biomolecules over time.12–15 At the core of this change is the functionality of several proteins.7 Long-lived proteins (with half-life of years, such as collagen and crystallin16) undergo non-enzymatic cross-linking, mediated by glycation end products, leading to the formation of high molecular weight products and aggregates. One such well-known example that causes the disease cataract is due to cross-links observed in lens crystallin and collagen, caused by prolonged UV−mediated damage and loss of redox homeostasis.17–19 Some therapeutics effective in reversing cross-linking have been shown to reverse some of the aging-related changes in rats and monkeys and in preliminary human trials.20 These reactions are generally residue-specific, and non-specific for motifs or enzymes.

Naturally observed cross-links are generated post-translationally in several ways. These include metal-catalyzed and enzymatic pathways, as well as oxidative reactions that trigger cross-linking in biomolecules.21–23 While the disulfide bond is a well-known cross-link in proteins, other novel and specific cross-links have been discovered through mass spectrometry. For example, oxidative cross-linking is obtained in the presence of chemical constituents like radicals and electron-rich species, or enzymatic action of oxidases.23 Addition of functional groups on residues can render them reactive under specific conditions, such as, chemical conditions, temperature, or light of a specific wavelength.24–26 Enzymatic catalysis of cross-links may play an essential role in switching the activity of the protein and regulating its function.7,27–29 Cross-linking can also be generated in vitro, using selective reagents, or incorporating amino acid analogues and non-canonical residues.22,30 The benefit of cross-linking natural residues is that it has minimal effect on the structure or activity of the protein, and is a better mimetic of conditions in vivo.7 The identification of novel cross-links has also paved the way for developing specialized protocols, reagents, and cross-linkers to selectively target residues under defined reaction conditions. Reviews of several cross-links identified thus far discuss the chemical biology and foodomics of various oxidative modifications.7,23,31,32 We complement these summaries by presenting a comprehensive structural perspective of unique cross-links discovered recently in the canonical aromatic and sulfur-containing amino acids, and discuss their applications in structural biology and protein biophysics. While both classes are involved in conferring structural stability, we also discuss how aromatics, with their characteristic absorption and fluorescence properties, can serve as essential probes. New applications, including protein bioengineering, drug development, studying protein-protein interactions, and as disease biomarkers, can readily be achieved by understanding the structural and physico-chemical characteristic of each unique cross-link. By highlighting the involvement of canonical residues in reactions that are highly unusual, we illustrate how cross-links can play important structural roles in real world applications involving proteins, while also serving as reporters of novel interactions and aging-associated diseases.

2. Cross-Links Involving Aromatic Residues

Cross-linking involving three canonical aromatic amino acids—tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine—has been a field of interest, due to the characteristic absorption (λabs-max ≈ 250−280 nm) and reactivity of these residues. Aromatic residues predominantly occupy the protein core and stabilize the structure, while additionally promoting protein folding and anchoring membrane proteins.33 Cross-linking involving aromatic residues can not only affect the primary structural role of these groups, but can also stabilize alternative conformations of these proteins. Formation and function of these unusual biochemical has been studied using mass spectrometry, crystallography and NMR, chromatography, as well as spectroscopy (fluorescence, dynamic light scattering, etc.). We discuss key aryl cross-links here, with characterization techniques and known mechanisms of their formation.

2.1. Tyr−Trp, di−Tyr, di−Trp cross-links

The formation of di-aryl cross-links, triggered by the generation of free radicals, has been well-characterized in several proteins and peptide mimetics.34,35 The presence of oxidants under anaerobic conditions results in high yields of Tyr−Trp, di-Tyr and di-Trp cross-links.36,37 Naturally, Tyr−Trp forms four major cross-linked products, involving C−N, O−N, C−O, or C−C linkages. Di-Tyr is formed via C−C or C−O linkages, while C−C or C−N linkages are seen in di-Trp (Figure 1).36 Di-Trp cross-links have been identified in human lens proteins, which additionally requires the photosensitizer kynurenic acid and N-acetyl-L-Trp, and is catalyzed by molecular oxygen.37 These di-Trp cross-links are linked both to aging and the formation of cataract.37 Di-Trp cross-links can be introduced in vitro in synthetic peptides using highly acidic conditions.38 Di-Tyr, formed in the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and catalyzed by Cu2+, has been shown to confer stability to dimers of Aβ-42 isoform of Aβ (amyloid-β), in vitro and in vivo, in neuroblastoma cells (Figure 2).39 The presence of copper as a catalyst is important in Aβ-42 cross-linking.40 In vitro, metal-catalyzed arylations, formed by activating C−H bonds, can be used to obtain stapled peptide sequences by directly cross-linking Trp with iodo-Phe/Tyr precursors.41 Di-Tyr/Trp links have been implicated in several such structures, including in the formation of hydrogels.42 A recent study highlighted how intra-protein di-Tyr cross-linking in α-synuclein prevents this protein from forming toxic aggregates in the system,43 suggesting that not all cross-links have unfavorable consequences.

Figure 1.

Radical-radical reactions forming di-Tyr, di-Trp, and Trp−Tyr cross-links. Tyrosine and tryptophan, in the presence of free radical generating agents, forsm resonating structures (center), and subsequently undergo cross-linking by the formation of C−O, C−C, C−N, or O−N bonds. Di-Tyr and di-Trp cross-links are shown on the left, and Trp-Tyr on the right. Di-Tyr cross-links have also been observed in the presence of peroxidase and laccase enzymes. Figure was redrawn from fig. 7 of Figueroa et al. (2020),36 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry under the CC BY-NC 3.0 license, and was generated using ChemDraw (® PerkinElmer Informatics Inc.).

Figure 2.

Plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease. Tyrosine present in the Aβ fibers forms di-Tyr cross-links in the presence of Cu2+ ions and ROS stress.39 These cross-links are central to stabilizing the Aβ oligomers. The reaction chemistry for the di-Tyr formation is similar to that shown in Figure 1. Image inspired from Al-Hilaly et al. (2013),39 and created with BioRender.com.

Di-aryl cross-links are also abundant in nature, and have functional significance. Fibrillary human fibronectins, found on the surface of myofibroblast, undergo oligomerization by forming o,o'-dityrosine cross-links, which, in turn, confers protease resistance to the fibronectin.44 These di-Tyr cross-links require hydrogen peroxide and peroxidases such as myeloperoxidase or horseradish peroxidase in the extracellular matrix. Peroxidases are also known to induce extensive oxidative cross-linking and oligomerization of Tyr, as is seen with Tyr octamers during α-lactalbumin polymerization.35 Similar free radical mechanisms have been seen for N-acetyl derivatives of Tyr and Trp, in the presence of rose Bengal and prolonged UV exposure.34 As diaryl links often lead to protein aggregation (with the exception of di-Tyr cross-link in α-syn43), the study of their formation gives essential insights into early events leading to diseases caused by protein aggregation. Given these cross-links involve the covalent linkage of two aromatic residues, for example di-Trp, studying the fluorescence properties can prove useful in development of probes as reporters for protein folding and mapping of biomolecular interaction networks.45

2.2. Trp−Tyr/Phe

A recent study identified a Trp−Phe cross-link in cyclophilin A, when the Trp was first substituted with its 7-fluoro analogue, and irradiated with UV. This photoreactivity occurs due to defluorination of 7-fluro-Trp when exposed to 282 nm light. The increased electron density at the C7 of indole triggers nucleophilic displacement of the fluorine atom upon UV exposure. Subsequently, this cross-links with a spatially proximal Phe in cyclophilin A (indole C7 cross-links with the para position of Phe) (Figure 3). This Trp−Phe cross-link extends the π-orbital system across both rings, giving rise to a fluorophore with red-shifted excitation and emission maxima of 304 nm and 373 nm, respectively, high quantum yield of ~0.4, and a 2.38 ns fluorescence lifetime.46 This reaction is highly specific for 7-F-Trp, and depends on the side chain conformations of the spatially proximal aromatics. However, the reaction is relatively non-specific for the cross-linking group, and can work with a tyrosine or any other strong nucleophile in the vicinity, and independent of an aryl residue.47 Further experimenting with different Trp analogues can provide novel approaches to design protein-specific fluorescent probes, for spectroscopy and fluorescence imaging studies.

Figure 3.

7-F indole-mediated aryl cross-linking. Crystal structures of cyclophilin A before (left) and after (right) the cross-linking of W121 with F60. The process is chemically driven by first converting the indole side chain of W121 to its 7-fluoro analogue (left; fluorine in red), followed by irradiation of the protein with 282 nm light.46 7-Fluoro-tryptophan is usually incorporated metabolically by growing the cells in media carrying indole analogues.48 Image inspired and reprinted (adapted) with permission from Lu et al., (2022).46 Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society. Structure coordinates PDB ID: 3K0N49 rendered using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

2.3. Trp−Gly

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are eukaryotic zinc-containing enzymes that play a role in morphogenesis, angiogenesis, tissue repair, and other pathophysiological processes.50 These proteins are involved in degradation of extracellular matrix proteins, and are implicated in photo-aging and photo-carcinogenesis.51 Phagocyte myeloperoxidases might play a role in regulating the enzymatic activity of MMPs by producing the potent oxidizing agent hypochlorous acid (HOCl).52 Studies have demonstrated that in human MMP-7 (matrilysin), HOCl leads to the formation of the oxidation product, 3-chloroindolenine at a W−G motif. This product cross-links with the amide nitrogen of the vicinal glycine, creating a six-membered aromatic ring (Figure 4). This cyclic Trp−Gly modification kinks the peptide backbone, reduces its conformational flexibility, hinders substrate binding in the catalytic pocket of MMP-7, and thereby regulating its activity.52 This unusual Trp−Gly modification is also of spectroscopic interest, owing to its red-shifted excitation and emission maxima of 363 and 412 nm, respectively, with a ~ 3.5-fold increase in fluorescence intensity.

Figure 4.

Autoregulation of MMPs by W-G cross-link. HOCl inactivates human MMP-7 by first oxidizing Trp to 3-chloroindolenine. This transient intermediate generates a cyclic six-membered indole-amide species by reacting with the backbone of the succeeding Gly. On the left is the proposed mechanism of the cross-linking, and on the right is the model Trp−Gly-containing peptide and the cyclized product. Note how the formation of the cyclized product dramatically lowers the conformational flexibility of the peptide backbone, which consequently affects substrate binding at the catalytic pocket of MMP-7. MMP-7 activity is regulated by the oxidants produced by the surrounding phagocytes, which causes sequential activation and inactivation of MMP-7 during inflammation. Figure on the left is redrawn with permission from Fu et al. (2004).52 Figure was generated using ChemDraw (® PerkinElmer Informatics Inc.) and PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

2.4. Trp−Lys

The radical S-adenosylmethionine (RaS) enzymes are a superfamily of proteins with [4Fe-S] clusters that reductively cleave S-adenosylmethionine, abstract a H atom from an amino acid, and generate a radical.53 These enzymes catalyze the synthesis of bioactive RiPPs (ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides) and numerous other post-translational protein modifications. The reactions catalyzed by this superfamily are quite unorthodox in nature.54 A recently identified K-W cyclase enzyme from Streptococcus thermophilus, belongs to the “SPASM domain” (subilitosin, PQQ, anaerobic sulfatases, and mycofactocin)55 of the RaS family. This enzyme forms a novel and highly specific C−C cross-link between lysine and tryptophan in a 21 residue natural peptide (Figure 5). An eight-residue internal leader sequence at the N-terminal region helps position the enzyme on the peptide for the Lys-Trp side chain cross-linking. The positioning role is also evident from the fact that this K-W cyclase helps cyclize only the KGDGW motif immediately adjacent to the binding site, and not the one ahead of it. This 21-residue sequence is also present in the human pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae.55

Figure 5.

Peptide-modifying K-W cyclase. A RaS enzyme with a characteristic SPASM domain post-translationally cross-links the side chains of Lys and Trp in the KGDGW motif of the 21 residue peptide substrate, with the first eight residues serving as leader sequence and enzymebinding site.55 The pentapeptide segment highlighting the cross-link is represented on the top, and spatial location of the Lys−Trp in the 21-residue peptide is illustrated at the bottom. The peptide structure was generated in silico using I-TASSER.56–58 The top panel was generated using ChemDraw (® PerkinElmer Informatics Inc.) and the bottom panel using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

2.5. Tyr−Arg

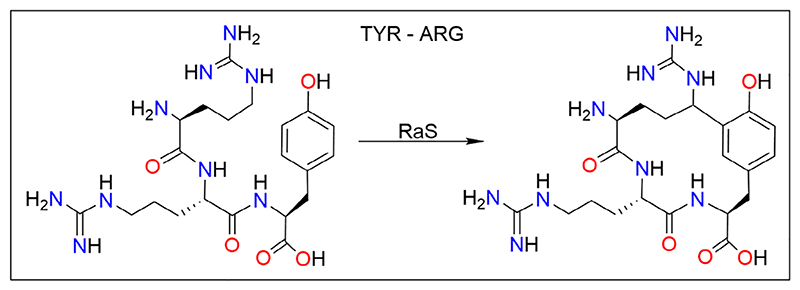

As discussed above, several natural RiPPs are post-translationally modified by the RaS enzymes.53 The RiPP products are present in biosynthetic gene clusters that co-localize the peptide with its modifying RaS enzymes.59 Over 600 gene clusters were recently identified from Streptococcus sp., wherein the expression of RiPP precursor peptide and its modifying RaS enzyme is co-functional with quorum sensing systems.60 One such enzyme belonging to the RRR subfamily (named after the conserved ITRRRY C-terminal motif) of RaS in Streptococcus suis, called RrrB, carries out macro-cyclization by radical-mediated cross-linking Cδ of arginine to the ortho position of tyrosine in the RRY motif (Figure 6).60 Interestingly, and unlike other RaS enzymes, a leader sequence is not required in this case. Similar RiPPs with an RRY motif, and RaS enzymes with sequence identity of >35% to RrrB, are found in other pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus delphini, Lactobacillus murinus, Butyrivibrio sp., and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.60

Figure 6.

Tyr−Arg cross-linking by the RaS enzyme RrrB. The RrrB enzyme, belonging to the RRR subfamily of RaS, recognizes the RRY motif in a co-translationally expressed peptide, and catalyzes its macro-cyclization via an Arg−Tyr cross-link. Unlike the K-W cyclase, RrrB can work independent of a leader sequence in the substrate. Figure is reprinted (adapted) with permission from Caruso et al. (2019).60 Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society. Figure was generated using ChemDraw (® PerkinElmer Informatics Inc.).

2.6. Tyr−Lys

Succinimidyl esters are extremely versatile and highly reactive cross-linking agents, particularly for primary amines (N-terminus, lysine side chain) in proteins. In addition to their diverse size, and universal reactivity with the N-terminus, these esters can be made to preferentially react with tyrosine under acidic conditions (pH 6.0) and lysine under alkaline conditions (pH 8.4). For example, under alkaline conditions, ethylene glycol bis(succinimidylsuccinate), with its 13-atom spacer arm and 16 Å cross-linking distance, cross-links lysine and tyrosine in the oxidized insulin β-chain and angiotensin I.61 By varying the pH, cross-links with the N-terminus, Lys−Lys and Tyr−Tyr, can also be generated.61 The selectivity of these reagents under different distance and pH constraints can be exploited to characterize spatial orientation of specific residues in the substrate protein.

2.7. Di-Tyr−Lys

While unusual cross-links found in nature are usually of functional significance, and involve a specialized synthetic pathway, enzymes can be exploited selectively to introduce artificial cross-links for various applications. One such enzyme is laccase, which belongs to multicopper proteins that act on quinols, aminophenols, and aromatic derivatives and catalyze oxidation.62 Laccases are widely distributed among several plants and fungi. Recent studies have exploited laccase to add tyrosine to lysine residues of bovine serum albumin (BSA) through a Schiff base formation or via Maillard reaction.63 The tyrosine can then undergo dimerization to di-tyrosine. This reaction allows for grafting tyrosines on BSA, and cross-linking of BSA into oligomers through these grafted tyrosines. This technique allows for grafting of tyrosine on other proteins as well, and has applications in modifying texture and strength of various natural textiles,64 increasing resistance of proteins to chemicals,65 and in changing the properties of food.66

2.8. Tyr−His

The heme copper oxidases superfamily of dioxygen-reducing enzymes are highly efficient in reducing molecular oxygen to water, and are abundant in the inner mitochondrial and bacterial membranes.67 These canonical cytochrome c oxidases have conserved Tyr and His in their copper center, which are additionally cross-linked. This cross-link plays an essential role in O2 reduction, by positioning the histidine as a ligand to the copper, and is therefore conserved from bacteria to mammals. The importance of this cross-link is additionally evident from the subfamily of cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, which supplement for the absence of this particular tyrosine by employing another tyrosine in a Tyr−His cross-link with the copper-ligating histidine at the active site.68 A conserved Tyr → Phe mutation, although maintains the structural integrity of the protein, does not allow for the cross-link to be formed with the histidine, resulting in loss of function. Engineering myoglobin with an artificial Tyr−His cross-link increased this protein's selectivity by 8-fold, and increased the turnover for oxygen reduction to water 3-fold.69 Thus, this highly specific Tyr−His cross-link has an indispensable role in the oxygen reduction process catalyzed by these enzymes. Designing copper oxidase-like model proteins has direct applications in the alternative energy.69

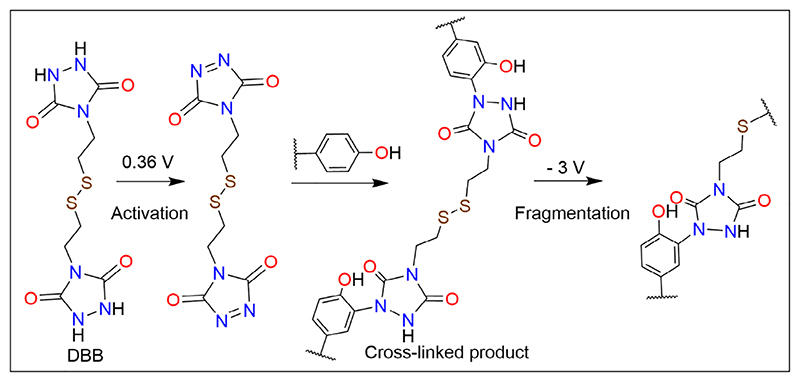

2.9. Tyrosine-reactive cross-linker

Cross-linking involving aromatic amino acids usually employs UV irradiation, and metal and enzyme catalysts.26,68,70 An approach to bypass this requirement led to the development of an electrochemical click reaction involving a novel molecule [4,4′-(disulfanediylbis(ethane-2,1-diyl)) bis(1,2,4-triazolidine-3,5-dione)] or DBB. This novel crosslinker selectively reacts with tyrosine residues and links it through electrochemical reduction. Additionally, DBB has an electrochemically cleavable disulfide bond. Activation of DBB by the application of voltage triggers cross-linking and formation of N−C bond with the meta carbon of spatially proximal Tyr rings (Figure 7). This novel molecule allows for generating transient cross-links with direct applications in studying protein−protein interactions. Inducing cross-linking at different time points, and under various cellular conditions, will allow for cross-linking in transiently interacting surfaces, which can be subsequently broken down easily and characterized using mass spectrometry.71 The reactivity of DBB and its application has been demonstrated with angiotensin II, insulin, β-casein, recombinant human growth hormone, and BSA.71

Figure 7.

Novel electrochemically cleavable tyrosine cross-linker. DBB catalyzes the cross-linking of tyrosines without requirement of UV or enzyme catalysis. The N−N bond of DBB is first oxidized to N=N bond at 0.36 V. This activated form of DBB can then cross-link with tyrosine residues in a peptide or protein. The cross-linking is reversible, and the cross-linked product can be fragmented by reducing the disulfide bond in DBB at -3 V. Figure is reprinted (adapted) with permission from Cui et al. (2021).71 Copyright (2021) American Chemical Society. Figure was generated using ChemDraw (® PerkinElmer Informatics Inc.).

2.10. Phe−Val

Proteins with internal covalent cross-links usually involve electronrich centers, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur-containing reactive functional groups, and are vital for their enzymatic activity. However, this is not always the case, as observed in the structure of symerythrin, a rubrerythrin-like protein from the photosynthetic eukaryote Cyanophora paradoxa, which possesses a covalent cross-link between the Cγ1 of valine and Cδ of phenylalanine (Figure 8).72 This C−C cross-link between the two unfunctionalized side chains is located in close spatial proximity to the diiron metallocenter of symerythrin. Unlike other cross-links, this Val−Phe covalent bridge has a structural role in securing the N-terminal tail of the protein to its core, while also stabilizing the diiron center.72 Given the unusual chemistry and the importance of this cross-link, detailed study of its generation will allow for generating biostructures with high structural strength.

Figure 8.

A C−C cross-link between two unfunctionalized side chains. A valine−phenylalanine cross-link is produced in an oxygen-dependent reaction in symerythrin protein in C. paradoxa. The crosslink formation requires the diiron metallocenter and O2 as the reductant, with the di-iron abstracting a hydrogen from Cγ1 of V127, forming a primary alkyl radical. This radical then reacts with F17 forming a C−C cross-link, without additional involvement of any functional groups.72 Structure coordinates PDB ID: 3QHB72 rendered using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

3. Cross-Links Involving Sulfur-Containing Residues

Cysteine and methionine are the two naturally abundant sulfur-containing amino acids of proteins. Methionine functions primarily as the initiator amino acid in protein synthesis, while cysteine is known for its ability to form disulfide bonds. The disulfide bond plays a significant role in modulating protein-folding pathways by lowering the entropy of the unfolded protein, and stabilizing protein structures.73 This is also the most prevalent natural post-translational cross-linking reaction in proteins. Met also undergoes modification to S-adenosylmethionine, which functions as a vital cofactor in essential metabolic processes.74,75 The lower electronegativity of sulfur, when compared to oxygen, is responsible for the distinctive properties of these amino acids. Many (if not all) of the known unusual cross-links involving cysteine are generated enzymatically or involve metal cofactors, and in this section, we discuss such redox modifications.

3.1. Cys−Cys

Disulfide linkages were first detected in bovine pancreatic ribonuclease in the 1950s.76 Cross-links between two cysteines can occur either through direct linkage or via a cross-linker. The first step usually involves oxidation of the −SH group of one cysteine to −S−, which acts as a nucleophile, and attacks the side chain of another nearby Cys, to form a disulfide bond with a stability (measured as bond dissociation energy) of ~60 kcal mol -1.77,78 The reaction rate and efficiency are influenced by spatial constraints between the two residues, pKa of both side chains, and the presence of oxidants (O2, H2O2, etc.; local redox environment). Artificial oxidizing agents can also chemically induce intra- and inter-protein disulfide bonds. Cysteines that are spatially inaccessible can be linked using cross-linkers, which act as bi-electrophiles and form thioether linkages with each cysteine.79 Disulfide bonds are responsible for stabilizing various protein structures, including antibodies and other secreted proteins, cell surface proteins, keratin etc.73 They also act as redox switches in bacterial enzymes. While they present several benefits, and their mutations can result in disease states,73 non-specific disulfide bond formations can also cause aggregation in proteins with high number of cysteines.

3.2. Cys−Lys

The transaldolase enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway of the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae forms a novel cross-link involving cysteine that acts as an allosteric redox switch and renders the protein inactive. This cross-link involves the formation of a N−O−S bridge between the primary amine of lysine and sulfur of cysteine via an oxygen (Figure 9).80 The activity can be restored by using simple reducing agents that will break the N−O−S bridge,80 allowing for regulation of enzymatic activity through redox activation. Lysine, being a larger side chain, allows for higher NOS flexibility and lower steric constraints compared to disulfide linkages.80 The NOS cross-link is not unique to transaldolases, and is indeed found in the catalytic pockets of several proteins from across families in pathogens and even humans, such as DNA base excision repair pathway80 and viral nuclear egress complex.80 The reversibility of this link can be exploited in novel peptide synthesis, while the NOS bridge of pathogens such as Neisseria sp., can be explored as a drug target.81

Figure 9.

NOS bridge as an allosteric redox switch. The transaldolase enzyme of the gonorrhea-causing pathogen, N. gonorrhoeae, is regulated by an allosteric redox switch. Activation of C38 in the presence of reactive oxygen species oxidizes the cysteine thiolate, which then forms a covalent conjugate with K8 residue by the attack of the Lys Nε on the thio-(hydro)peroxy intermediate.80 The Lys−NOS−Cys bridge (shown here) can be reversed under reducing conditions, relaxing the covalent restraint and reconfiguring the surrounding residues, thereby activating the enzyme. Image inspired from Wensien et al. (2021).80 Structure coordinates PDB ID: 6ZX480 rendered using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

3.3. Cys−Tyr

Metalloprotein cofactors are a class of redox active, post-translational modifications formed by or within metalloproteins, are bound to the protein, and act as oxidants.82,83 While crystallographic studies have identified several metalloprotein cofactors, alternative methods for identification of metal-bound cross-links is through chemical bioinformatics.84 Here, protein structures are screened, using H-bonding and metal proximity, for chemical environments conducive for forming a cross-linked cofactor. With chemical bioinformatics, a search for Cys−Tyr cross-link yielded the orphan metalloprotein BF4122, from the organism Bacteroides fragilis. Proteomics analysis showed that proximity to the metal center (zinc), and copper-binding site, the vicinal tyrosine and cysteine side chains could indeed form a cross-link (Figure 10).84 The study also established how a cupin fold, and not a β-barrel (CDO) or β-propeller (GalOx) fold, can form the Cys−Tyr cross-link and host a copper-binding site adjacent to it (Figure 10). Similar chemical bioinformatics approaches for template-based searches can help identify other cofactor proteins with unusual crosslinks.

Figure 10.

BF4112 forms a Cys−Tyr cross-link. Proteomics studies confirm the formation of a 3-(S-cysteinyl)-tyrosine cross-link between Y52 and C98 when the protein BF4112 is first prepared with one Cu2+ ion per monomer, reacted with sodium dithionite under anaerobic conditions, followed by O2 exposure. The additional formation of Q50-Y52 H-bond increases tyrosine oxidation, but also restricts its rotation. The cupin fold topology is vital in ensuring that all components to generate the cross-link are located within a 3.0-4.0 Å vicinity of the metal-binding center. Image inspired from Martinie et al. (2012).84 Structure coordinates PDB ID: 3CEW (10.2210/pdb3CEW/pdb) rendered using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

3.4. Met−Lys

Unlike Cys, the Met side chain is less reactive. However, reactive halogen species can kinetically target and oxidatively modify methionine,85,86 with the resultant formation of sulfilimine (>S=N−) bonds. For example, hypobromous acid and bromamines cross-link Met with Lys in an intramolecular fashion in the model peptide formyl−Met−Leu−Phe−Lys. Chloramines, on the other hand, formed intermolecular bonds.87 If these residues are within the required spatial constraints, such cross-links can also be formed in proteins, as is seen in collagen IV.87 These cross-links can also be generated by other oxidants inside the body, and are implicated not only in oxidative stress and inflammation, but are also required to structurally support the extracellular matrix.88 Such oxidative cross-linking adducts contribute to cross-linking in the artery walls and in other inflammatory conditions leading to tissue damage.

4. Cross-Links Involving Other Amino Acids

4.1. His−His/Lys/Cys

Aggregation of antibodies is a serious concern, since it affects its immunogenicity and toxicity. Unfavorable intra- as well as intermolecular cross-links are one of the causes of such aggregation. Cross-links formed between oxidized form of histidine in the high molecular weight fractions of IgG1 monoclonal antibody can cross-link with lysines, cysteines, and other histidines. These cross-links are not reversible, and are formed primarily in aged antibody molecules.89 Studying this reaction is of importance when developing antibody based treatments, and the long-term storage of these antibodies.

4.2. Dehydroamino acids

Cross-links due to dehydroamino acids have been detected in many processed (cooked) foods, and they significantly impact the food quality, taste, and safety. Knowledge of the locations of such cross-links, the precursors involved, and the reaction chemistry is needed to develop better quality food and food processing techniques.90 Using BSA and wheat gliadin as model proteins, researchers have identified how cysteines, serines and threonines undergo β-elimination when heated to 130°C.91 These amino acids subsequently react with lysines and cysteines through Michael addition to form dehydroamino acids and cross-links. While these modifications occur naturally,92,93 these reactions can occur when food products are heated. Deducing the impact of such cross-links on the structure and consistency of food proteins will help in developing food products that are healthier and of better quality, improving taste, and preventing toxicity due to the cross-links.

4.3. Asp/Asn−Lys

The glycosylation theory of aging states that aging is a result of gradual chemical changes causing detrimental effect on proteins and other biomolecules.94 Long-lived proteins such as that of the eye lens start to break down with age. Such protein breakdown is also implicated in other diseases.95 Proteomic techniques applied to the human ocular lenses have revealed cross-links at several sites between lysine and aspartate/asparagine side chains, which are not directly related to glycosylation. Experiments with model peptides showed that the mechanism involves formation of succinimides by Asn at neutral pH, and Asp at acidic pH. These succinimides were stable in the absence of nucleophiles, whereas the presence of lysine side chain triggers crosslink formation.96 Succinimides therefore represent a novel method of cross-linking involved in aging and in long-lived proteins. Identifying and characterizing other possible cross-links, using proteomic studies coupled with mass spectrometry, is imperative for development of anti-aging treatments.

4.4. Lysine-selective photo-cross-linking

Cross-linking is an important tool in studying protein−protein interactions. A cross-link that can be readily induced in vivo, and is also highly specific for certain residues, can be used extensively for this purpose. The photoactivatable cross-linker o-nitrobenzyl alcohol lysine (o-NBAK) is a novel cross-linker that can be genetically encoded into bacterial genomes (amber suppressor mutants) for incorporation in proteins.97 By incorporating o-NBAK into Schistosoma japonicum glutathione-S-transferase expressed in Escherichia coli, studies have demonstrated how dimerization of this protein can be triggered in vitro and in vivo via UV light activation.97 Here, the intermediate generated from o-NBAK reacts readily with the proximal lysine ε-amino group to yield an indazolone product.97 This Lys-selective photoactivatable cross-link offers a direct way of mapping protein interfaces in vivo, building interactomes, and studying signaling pathways.

4.5. Transglutaminases

Transglutaminases are enzymes found in several organisms, including humans, and they catalyze the formation of isopeptide bonds between the carboxamide group of glutamine and the Є-amino group of lysine.98 This reaction, called aminylation, is catalyzed by Ca-dependent transglutaminases.98 They are also capable joining primary amines to carboxamide groups present in peptides or proteins.99 Distance constraint (e.g., tissue transglutaminase-2 catalyzes Gln−Lys bonding only at distances <2.0 Å98), and the protein sequence are the primary determinants of transgultaminase activity. These enzymes are involved in multiple functions. The cross-linked protein polymers formed by these proteins help form barrier-like structures for blood clot formation. Given these extensive cross-links these enzymes can create, they are often used in food processing, and have even been used in the cooking industry to create new food products.100

5. Applications Of Cross-Links

Biological systems have been under constant evolution over millions of years, which have allowed these molecules to both diversify and perfect their systems. New technology developments that use biomolecules can readily draw inspiration from nature. By way of post-translational modifications, natural and site-specific cross-links have allowed proteins to use surrounding conditions to regulate their activity, stabilize structures, anchor to other proteins, and many more novel capabilities. Characterizing these cross-links opens up avenues for peptide engineering and enzyme modification. Moreover, the proteins that have been identified and characterized with these crosslinks now serve as templates for identifying other proteins with similar or better cross-linking through large-scale bioinformatics approaches, thus reducing the burden of crystallographic studies while also expanding the repertoire of such modifications.

The potential applications of cross-linking canonical amino acids are wide-ranging. Thus far, cross-linking in modern biology has primarily been limited to mapping protein interactions.101 Given how just 20 amino acids can generate millions of different protein sequences, the possibilities that can be generated by cross-linking them is endless. Using residues other than cysteine and lysine to cross-link proteins will provide for greater flexibility in protein−protein interaction studies, allowing more specific binding and better resolution data. Cross-linkers like DBB allow simpler ways of creating reversible cross-links,71 while modified aryl rings like 7-F tryptophan creates alternative intrinsic probes for fluorescence studies.46,47 Photo-activated cross-links can provide insight on dynamics of aryl groups in real time, with considerably less protein concentrations than those required by NMR.46,102 Experimenting with this and other novel cross-links can help develop probes that display fluorescence in the visible region, for applications in non-invasive live cell imaging. Functional benefits of replicating simple cross-links, as seen with His−Tyr modification in myoglobin,69 allow for developing proteins with superior activity, developing artificial enzymes, and catalytic peptides with singular function and enhanced stability.

The emergence of diverse cross-links, while currently limited to laboratory applications, finds far-reaching applications in the real world. Cross-linking of alternate residues combined with novel linking methods have been used to develop structures with better capacity to hold water.9–11 The use of cross-linkers on natural textile proteins can improve their strength and texture.65 Improvised protein crosslinks can help improve the quality, safety, and shelf-life of food items.66 Unique and extremely specific cross-links, which are physiologically important for several pathogenic microorganisms, and their biosynthetic pathway, can be targeted with drugs. Biomedical applications that require stable biomaterials are generated usually with chemical cross-linkers that additionally carry undesired functionality or cause cytotoxicity.103–105 Improved tensile properties of crosslinked biomaterials and nanoparticles can now be achieved using cross-linking with canonical residues (e.g, di-Tyr cross-links.106) The detection of protein cross-links accumulated over time (e.g., as seen in protein damage upon UV exposure47) can serve as markers for cellular damage due to aging, and the predisposition of various demographics to aging-associated diseases. Here, we discuss two real-world applications of cross-linking.

5.1. Immunogenic nanoclusters with cross-linking

Immunization has, and continues to save millions of lives every year. With multiple new infections or variants of existing pathogens emerging every year, it is essential to develop newer, safer, effective, and affordable vaccines. Protein subunit vaccines are safe, effective, and have emerged from a well-established technology.107 Their drawbacks are the use of adjuvants and the selection of suitable antigens. An alternative is to use protein nanoclusters (PNCs), which are subunit vaccines made entirely of antigen peptides. This eliminates the use of an antigen-presenting surface or encapsulation, and significantly reduces the development time, reduces manufacturing complexity, improves the antigens per molecule, and the immune response.108 The degradation products of PNCs also serve as immunogens. The major drawback with PNCs is the self-assembly tags, which have been the one way to produce nanoclusters, act as antigens.108

Improvised PNCs have now been developed using cross-linked structures, generated using oxidation reactions involving thiols. A trithiol cross-linker joining oncofetal antigens was tested to develop a nanocluster vaccine against cancer.109 The cysteines were introduced such that the antigenic surfaces were not perturbed, and the cross-links occurred only at the desired sites.109 Another study successfully used a tyrosine-based cross-linker.31 By exploiting nickel ion binding to the spatially proximal His6-tag, Tyr was made to selectively undergo oxidation at −OH to form di-tyrosine cross-links, thereby linking peptide molecules to obtain PNCs of various sizes.31 Directing the cross-linking to specific positions allows for the development of tunable nanoclusters of various sizes and shapes, for use in different applications.

5.2. Cross-linking in food proteins

Proteins play a substantial role in various food products by providing functional and ornamental qualities.110 Many steps in cooking involve ways to process the proteins in them, to help achieve a specific texture, taste, and consistency. Food proteins' physical and chemical processing is at the core, be it poaching to get the chewy texture of pretzels, or kneading to obtain a fluffy dough. Most of these processes lead to the generation of cross-links between food proteins that go beyond simple disulfide linkages.23 Heating causes β-elimination in amino acids,111 and the subsequent Michael addition leads to inter- and intra-chain cross-links. Indeed, lanthionine (Cys−Ser cross-link) and lysinoalanine (Lys−Cys cross-link after Cys is converted to dehydroalanine)92,93 have been detected in several processed foods, which can reduce protein digestibility and also produce potentially toxic products.111 In addition to cysteine, serine and threonine are also susceptible to β-elimination,91 with specific protein motifs being more prone to these linkages. Studies have demonstrated the effect of β-elimination on the quality and toxicity of food proteins.111 The detection of similar linkages in food products using mass spectrometry will directly benefit the food processing industry.

6. Discussion

Cross-linking of proteins has emerged as a valuable tool for multiple applications. For example, they have been used to anchor proteins to solid surfaces for biosensors, tissue engineering, chromatographic applications, and in understanding protein−protein interactions. Coupling cross-linking with mass spectrometry has allowed the discovery of catalytically important sites in proteinaceous enzymes, and in deducing their three-dimensional structure. Here, it is important to characterize and map differences between the effect of intra- and inter-molecular cross-links in detail, and advantages they may offer for bio-applications.112 Intra-molecular cross-links can lead to structural constraints and cyclization, thereby directly impacting function and activity. Inter-molecular cross-links can cause networking, and cause unfavorable aggregation effects and surface formation, or produce favorable biomaterials such as nanoparticles and hydrogels.45,103,105,106,112 While we have not discovered all (nearly a million) possible permutations of cross-links across the naturally abundant 20 amino acids, the development of chemical and biophysical techniques, coupled with bioinformatics analyses, will unravel unique cross-links with their reaction chemistries. For example, a recent study demonstrated how Cys-derived cross-links can readily generate a library of end products in both peptides and proteins.113 As seen with RaS enzymes,55 a simple template search can help discover enzymes with unique cross-linking abilities. Detailed knowledge of precursors and the reaction chemistry (discussed here and earlier reviews7,23,32,103,105) will allow for the development of novel crosslinks towards translational applications including designing protein-specific probes, high-quality superstructures, stable nanostructures, superfoods, and enzymes with higher catalytic activity.

Artificially generated cross-links are beneficial for incorporating structural characteristics and locked conformations in proteins that directly impact their activity, conformational flexibility, and turnover. The library of cross-linked permutations identified thus far are sufficiently diverse, allowing for selection of the best candidates to engineer proteins and elicit the desired changes. Grouping cross-link types according to their structural and functional impact, as we have done here, will help generate repositories, expediting their testing and incorporation in diagnostics, drug development and delivery, and in the food industry for food preservation and food quality. For example, simple aryl-driven cross-links (Tyr−Tyr/Trp, Trp−Gly/Phe) give rise to ordered structures that can be used for protein structure determination, mapping protein-protein interactions, or reinforced natural polymers. The extended resonance structures additionally have application in generating fluorescent entities for molecular mapping of biomolecule dynamics in vitro and in vivo. Those involving reversible sulfur-based cross-links can act as molecular switches. The formation of ring structures lowers flexibility of peptides, enabling their use as stable drugs with enhanced effectiveness, and additionally as encapsulation moieties for carrying drugs with improved and prolonged drug release profiles. Cross-linking electron-rich residues and metal ion carriers allows for biomaterial engineering in regenerative medicine. Improved detection of cross-linked species in age-associated diseases47 will facilitate early identification of neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, macular degeneration and cataracts, obstructive pulmonary disease and atherosclerosis, while also leading to enhanced treatment regimens and early therapeutic interventions.

Structural and mass spectrometric methods have together led to the discovery of several novel cross-links between natural amino acids in a diverse array of proteins. These bonds serve as structural reinforcements, enzymatic switches toward novel functions, and serve as probes for study. This review has discussed several unique cross-links that are functionally essential for the parent protein. While these and other cross-links have been identified, several remain to be discovered, and their molecular mechanism(s) of formation and function require detailed characterization. The knowledge of these and other unique cross-links will facilitate development of new chemistries that replicate the natural cross-links for novel applications.

Acknowledgements

Jinam Ravindra Bora thanks the Department of Science and Technology for Innovation in Science Pursuit for Inspired Research— Scholarship for Higher Education (INSPIRE−SHE). Radhakrishnan Mahalakshmi is a recipient of the DBT−Wellcome India Alliance Senior Fellowship and the Lady Tata Memorial Trust Young Researcher Award. This work was supported by the India Alliance grant IA/S/20/2/505182, Science and Engineering Research Board grant SPR/2021/000018, and the Department of Biotechnology grant BT/PR28858/BRB/10/1718/2018, to Radhakrishnan Mahalakshmi.

Funding information

Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, India, Grant/Award Number: BT/PR28858/BRB/10/1718/2018; Science and Engineering Research Board, Grant/Award Number: SPR/2021/000018; The Wellcome Trust DBT India Alliance, Grant/Award Number: IA/S/20/2/505182

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Jinam Ravindra Bora: Conceptualization; writing − original draft; writing − review and editing. Radhakrishnan Mahalakshmi: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing − original draft; writing − review and editing.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1002/prot.26571.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.Lee D, Redfern O, Orengo C. Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(12):995–1005. doi: 10.1038/nrm2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dill KA, MacCallum JL. The protein-folding problem, 50 years on. Science. 2012;338(6110):1042–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.1219021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn A, Boivin P, Rubinson H, Cottreau D, Marie J, Dreyfus JC. Modifications of purified glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and other enzymes by a factor of low molecular weight abundant in some leukemic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73(1):77–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kivirikko KI, Risteli L. Biosynthesis of collagen and its alterations in pathological states. Med Biol. 1976;54(3):159–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risteli J, Kivirikko KI. Intracellular enzymes of collagen biosynthesis in rat liver as a function of age and in hepatic injury induced by dimethylnitrosamine. Changes in prolyl hydroxylase, lysyl hydroxylase, collagen galactosyltransferase and collagen glucosyltransferase activities. Biochem J. 1976;158(2):361–367. doi: 10.1042/bj1580361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalle-Donne I, Aldini G, Carini M, Colombo R, Rossi R, Milzani A. Protein carbonylation, cellular dysfunction, and disease progression. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10(2):389–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravikiran B, Mahalakshmi R. Unusual post-translational protein modifications: the benefits of sophistication. RSC Adv. 2014;4:33958–33974. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimsrud PA, Xie H, Griffin TJ, Bernlohr DA. Oxidative stress and covalent modification of protein with bioactive aldehydes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(32):21837–21841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millon LE, Wan WK. The polyvinyl alcohol-bacterial cellulose system as a new nanocomposite for biomedical applications. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;79(2):245–253. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palantöken S, Bethke K, Zivanovic V, Kalinka G, Kneipp J, Rademann K. Cellulose hydrogels physically crosslinked by glycine: synthesis, characterization, thermal and mechanical properties. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137:48380 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada K, Tabata Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Potential efficacy of basic fibroblast growth factor incorporated in biodegradable hydrogels for skull bone regeneration. J Neurosurg. 1997;86(5):871–875. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.5.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sell DR, Nagaraj RH, Grandhee SK, et al. Pentosidine: a molecular marker for the cumulative damage to proteins in diabetes, aging, and uremia. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1991;7(4):239–251. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610070404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorksten J, Andrews F. Fundamentals of aging: a comparison of the mortality curve for humans with a viscosity curve of gelatin during the cross-linking reaction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1960;8:632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1960.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornstein P. The cross-linking of collagen and elastin and its inhibition in osteolathyrism. Is there a relation to the aging process? Am J Med. 1970;49(4):429–435. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(70)80036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartos F, Ledvina M. Age changes of cross-links in rat skin elastin. Arch Dermatol Forsch. 1971;241(2):134–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00595366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu P, Edassery SL, Ali L, Thomson BR, Savas JN, Jin J. Long-lived metabolic enzymes in the crystalline lens identified by pulse-labeling of mice and mass spectrometry. Elife. 2019;8:e50170. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckingham RH. Cross-links in protein from cataractous lenses. Bio-chem J. 1971;124(5):54P–55P. doi: 10.1042/bj1240054pb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckingham RH. The behaviour of reduced proteins from normal and cataractous lenses in highly dissociating media: cross-linked protein in cataractous lenses. Exp Eye Res. 1972;14(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding JJ. Disulphide cross-linked protein of high molecular weight in human cataractous lens. Exp Eye Res. 1973;17(4):377–383. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(73)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasan S, Foiles P, Founds H. Therapeutic potential of breakers of advanced glycation end product-protein crosslinks. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;419(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heck T, Faccio G, Richter M, Thony-Meyer L. Enzyme-catalyzed protein cross-linking. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(2):461–475. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4569-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora B, Tandon R, Attri P, Bhatia R. Chemical cross-linking: role in protein and peptide science. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(9):946–955. doi: 10.2174/1389203717666160724202806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuentes-Lemus E, Hagglund P, Lopez-Alarcon C, Davies MJ. Oxidative cross-linking of peptides and proteins: mechanisms of formation, detection, characterization and quantification. Molecules. 2021;27(1):15. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, Heim A, Riether D, et al. Reactivity of functional groups on the protein surface: development of epoxide probes for protein labeling. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(27):8130–8133. doi: 10.1021/ja034287m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagar AD, Patil MD, Flood DT, Yoo TH, Dawson PE, Yun H. Recent advances in biocatalysis with chemical modification and expanded amino acid alphabet. Chem Rev. 2021;121(10):6173–6245. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen TH, Garnir K, Chen CY, et al. A toolkit for engineering proteins in living cells: peptide with a tryptophan-selective Ru-TAP complex to regioselectively photolabel specific proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(39):18117–18125. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c08342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumura M, Matthews BW. Control of enzyme activity by an engineered disulfide bond. Science. 1989;243(4892):792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.2916125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakashima I, Kato M, Akhand AA, et al. Redox-linked signal transduction pathways for protein tyrosine kinase activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4(3):517–531. doi: 10.1089/15230860260196326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivaramakrishnan S, Keerthi K, Gates KS. A chemical model for redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(31):10830–10831. doi: 10.1021/ja052599e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chrysanthou M, Miro Estruch I, Rietjens I, Wichers HJ, Hoppenbrouwers T. In vitro methodologies to study the role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in neurodegeneration. Nutrients. 2022;14(2):363. doi: 10.3390/nu14020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilks LR, Joshi G, Grisham MR, Gill HS. Tyrosine-based cross-linking of peptide antigens to generate nanoclusters with enhanced immunogenicity: demonstration using the conserved M2e ieptide of influenza A. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7(9):2723–2735. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renzone G, Arena S, Scaloni A. Cross-linking reactions in food proteins and proteomic approaches for their detection. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2022;41(5):861–898. doi: 10.1002/mas.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vondrasek J, Bendova L, Klusak V, Hobza P. Unexpectedly strong energy stabilization inside the hydrophobic core of small protein rubredoxin mediated by aromatic residues: correlated ab initio quantum chemical calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(8):2615–2619. doi: 10.1021/ja044607h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludvikova L, Stacko P, Sperry J, Klan P. Photosensitized cross-linking of tryptophan and tyrosine derivatives by rose Bengal in aqueous solutions. JOrg Chem. 2018;83(18):10835–10844. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhayal SK, Sforza S, Wierenga PA, Gruppen H. Peroxidase induced oligo-tyrosine cross-links during polymerization of alpha-lactalbumin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854(12):1898–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Figueroa JD, Zarate AM, Fuentes-Lemus E, Davies MJ, Lopez-Alarcon C. Formation and characterization of crosslinks, including Tyr-Trp species, on one electron oxidation of free Tyr and Trp residues by carbonate radical anion. RSC Adv. 2020;10(43):25786–25800. doi: 10.1039/d0ra04051g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sormacheva ED, Sherin PS, Tsentalovich YP. Dimerization and oxidation of tryptophan in UV-A photolysis sensitized by kynurenic acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;113:372–384. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makwana KM, Mahalakshmi R. Trp-Trp cross-linking: a rtructure-reactivity relationship in the formation and design of hyperstable peptide beta-hairpin and alpha-helix scaffolds. Org Lett. 2015;17(10):2498–2501. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hilaly YK, Williams TL, Stewart-Parker M, et al. A central role for dityrosine cross-linking of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:83. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maina MB, Burra G, Al-Hilaly YK, Mengham K, Fennell K, Serpell LC. Metal-and UV-catalyzed oxidation results in trapped amyloid-beta intermediates revealing that self-assembly is required for Abeta-induced cytotoxicity. iScience. 2020;23(10):101537. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendive-Tapia L, Preciado S, Garcia J, et al. New peptide architectures through C-H activation stapling between tryptophan-phenylalanine/tyrosine residues. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7160. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding Y, Li Y, Qin M, Cao Y, Wang W. Photo-cross-linking approach to engineering small tyrosine-containing peptide hydrogels with enhanced mechanical stability. Langmuir. 2013;29(43):13299–13306. doi: 10.1021/la4029639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahin C, Osterlund EC, Osterlund N, et al. Structural basis for dityrosine-mediated inhibition of alpha-synuclein fibrillization. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(27):11949–11954. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c03607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Locy ML, Rangarajan S, Yang S, et al. Oxidative cross-linking of fibronectin confers protease resistance and inhibits cellular migration. Sci Signal. 2020;13(644):eaau2803. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang AH, Gross J. Relationship between the intra and intermolecular cross-links of collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;67(3):1307–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.3.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu M, Toptygin D, Xiang Y, et al. The magic of linking rings: discovery of a unique photoinduced fluorescent protein crosslink. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(24):10809–10816. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c02054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bora JR, Mahalakshmi R. Photoradical-mediated catalystindependent protein cross-link with unusual fluorescence properties. Chembiochem. 2023:e202300380. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202300380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broos J, Gabellieri E, Biemans-Oldehinkel E, Strambini GB. Efficient biosynthetic incorporation of tryptophan and indole analogs in an integral membrane protein. Protein Sci. 2003;12(9):1991–2000. doi: 10.1110/ps.03142003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fraser JS, Clarkson MW, Degnan SC, Erion R, Kern D, Alber T. Hidden alternative structures of proline isomerase essential for catalysis. Nature. 2009;462(7273):669–673. doi: 10.1038/nature08615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klein T, Bischoff R. Physiology and pathophysiology of matrix metalloproteases. Amino Acids. 2011;41(2):271–290. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0689-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pittayapruek P, Meephansan J, Prapapan O, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in photoaging and photocarcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):868. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu X, Kao JL, Bergt C, et al. Oxidative cross-linking of tryptophan to glycine restrains matrix metalloproteinase activity: specific structural motifs control protein oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):6209–6212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Broderick JB, Duffus BR, Duschene KS, Shepard EM. Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. Chem Rev. 2014;114(8):4229–4317. doi: 10.1021/cr4004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehta AP, Abdelwahed SH, Mahanta N, et al. Radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzymes in cofactor biosynthesis: a treasure trove of complex organic radical rearrangement reactions. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(7):3980–3986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.623793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benjdia A, Decamps L, Guillot A, et al. Insights into the catalysis of a lysine-tryptophan bond in bacterial peptides by a SPASM domain radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) peptide cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(26):10835–10844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.783464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, Zhang Y. The I-TASSER suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McIntosh JA, Donia MS, Schmidt EW. Ribosomal peptide natural products: bridging the ribosomal and nonribosomal worlds. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(4):537–559. doi: 10.1039/b714132g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caruso A, Martinie RJ, Bushin LB, Seyedsayamdost MR. Macrocyclization via an arginine-tyrosine crosslink broadens the reaction scope of radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(42):16610–16614. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leavell MD, Novak P, Behrens CR, Schoeniger JS, Kruppa GH. Strategy for selective chemical cross-linking of tyrosine and lysine residues. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15(11):1604–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shraddha SR, Sehgal S, Kamthania M, Kumar A. Laccase: microbial sources, production, purification, and potential biotechnological applications. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:217861. doi: 10.4061/2011/217861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Y, Su J, Cavaco-Paulo A. Laccase-catalyzed cross-linking of BSA mediated by tyrosine. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;166:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cortez J, Anghieri A, Bonner PLR, Griffin M, Freddi G. Transglutaminase mediated grafting of silk proteins onto wool fabrics leading to improved physical and mechanical properties. Enzyme Microb Tech-nol. 2007;40(7):1698–1704. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cortez J, Bonner PL, Griffin M. Transglutaminase treatment of wool fabrics leads to resistance to detergent damage. J Biotechnol. 2005;116(4):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buchert J, Ercili Cura D, Ma H, et al. cross-linking food proteins for improved functionality. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2010;1:113–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Heme/copper terminal oxidases. Chem Rev. 1996;96(7):2889–2908. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rauhamaki V, Baumann M, Soliymani R, Puustinen A, Wikstrom M. Identification of a histidine-tyrosine cross-link in the active site of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 2006;103(44):16135–16140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606254103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu X, Yu Y, Hu C, Zhang W, Lu Y, Wang J. Significant increase of oxidase activity through the genetic incorporation of a tyrosine-histidine cross-link in a myoglobin model of heme-copper oxidase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(18):4312–4316. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong J, Huang C, Guo S, et al. Free-radical-mediated photoinduced electron transfer between 6-thioguanine and tryptophan leading to DNA-protein-like cross-link. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(1):14–22. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c03380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cui L, Ma Y, Li M, et al. Tyrosine-reactive cross-linker for probing protein three-dimensional structures. Anal Chem. 2021;93(10):4434–4440. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooley RB, Rhoads TW, Arp DJ, Karplus PA. A diiron protein autogenerates a valine-phenylalanine cross-link. Science. 2011;332(6032):929. doi: 10.1126/science.1205687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feige MJ, Braakman I, Hendershot LM. In: Oxidative Folding of Proteins: Basic Principles, Cellular Regulation and Engineering. Feige MJ, editor. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2018. Disulfide bonds in protein folding and stability; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ouyang Y, Wu Q, Li J, Sun S. S-adenosylmethionine: a metabolite critical to the regulation of autophagy. Cell Prolif. 2020;53(11):e12891. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pascale RM, Simile MM, Calvisi DF, Feo CF, Feo F. S-Adenosyl-methionine: from the discovery of its inhibition of tumorigenesis to its use as a therapeutic agent. Cell. 2022;11(3):409. doi: 10.3390/cells11030409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruoppolo M, Torella C, Kanda F, et al. Identification of disulphide bonds in the refolding of bovine pancreatic RNase A. Fold Des. 1996;1(5):381–390. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(96)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pace CN, Grimsley GR, Thomson JA, Barnett BJ. Conformational stability and activity of ribonuclease T1 with zero, one, and two intact disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(24):11820–11825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sowdhamini R, Srinivasan N, Shoichet B, Santi DV, Ramakrishnan C, Balaram P. Stereochemical modeling of disulfide bridges. Criteria for introduction into proteins by site-directed mutagenesis. Protein Eng. 1989;3(2):95–103. doi: 10.1093/protein/3.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prahlad J, Hauser DN, Milkovic NM, Cookson MR, Wilson MA. Use of cysteine-reactive cross-linkers to probe conformational flexibility of human DJ-1 demonstrates that Glu18 mutations are dimers. J Neurochem. 2014;130(6):839–853. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wensien M, von Pappenheim FR, Funk LM, et al. A lysine-cysteine redox switch with an NOS bridge regulates enzyme function. Nature. 2021;593(7859):460–464. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nussinov R, Tsai CJ. The design of covalent allosteric drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:249–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davidson VL. Generation of protein-derived redox cofactors by posttranslational modification. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7(1):29–37. doi: 10.1039/c005311b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davidson VL. Protein-derived cofactors. Expanding the scope of post-translational modifications. Biochemistry. 2007;46(18):5283–5292. doi: 10.1021/bi700468t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martinie RJ, Godakumbura PI, Porter EG, et al. Identifying proteins that can form tyrosine-cysteine crosslinks. Metallomics. 2012;4(10):1037–1042. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20093g. 1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Kinetic analysis of the reactions of hypobromous acid with protein components: implications for cellular damage and use of 3-bromotyrosine as a marker of oxidative stress. Biochemistry. 2004;43(16):4799–4809. doi: 10.1021/bi035946a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine, and ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(5):572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ronsein GE, Winterbourn CC, Di Mascio P, Kettle AJ. Cross-linking methionine and amine residues with reactive halogen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;70:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fu X, Mueller DM, Heinecke JW. Generation of intramolecular and intermolecular sulfenamides, sulfinamides, and sulfonamides by hypochlorous acid: a potential pathway for oxidative cross-linking of low-density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry. 2002;41(4):1293–1301. doi: 10.1021/bi015777z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu CF, Chen Y, Yi L, et al. Discovery and characterization of histidine oxidation initiated cross-links in an IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Anal Chem. 2017;89(15):7915–7923. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ghate V, Leong AL, Kumar A, Bang WS, Zhou W, Yuk HG. Enhancing the antibacterial effect of 461 and 521 nm light emitting diodes on selected foodborne pathogens in trypticase soy broth by acidic and alkaline pH conditions. Food Microbiol. 2015;48:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rombouts I, Lambrecht MA, Carpentier SC, Delcour JA. Identification of lanthionine and lysinoalanine in heat-treated wheat gliadin and bovine serum albumin using tandem mass spectrometry with higher-energy collisional dissociation. Amino Acids. 2016;48(4):959–971. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lynch MJ, Miller M, James M, et al. Structure and chemistry of lysi-noalanine cross-linking in the spirochaete flagella hook. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(10):959–965. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.An L, Cogan DP, Navo CD, Jimenez-Oses G, Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Substrate-assisted enzymatic formation of lysinoalanine in duramycin. Nat Chem Biol. 2018;14(10):928–933. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moremen KW, Tiemeyer M, Nairn AV. Vertebrate protein glycosylation: diversity, synthesis and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(7):448–462. doi: 10.1038/nrm3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Krisko A, Radman M. Protein damage, ageing and age-related diseases. Open Biol. 2019;9(3):180249. doi: 10.1098/rsob.180249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Friedrich MG, Wang Z, Schey KL, Truscott RJW. Spontaneous cross-linking of proteins at aspartate and asparagine residues is mediated via a succinimide intermediate. Biochem J. 2018;475(20):3189–3200. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hu W, Yuan Y, Wang C-H, et al. Genetically encoded residue-selective photo-crosslinker to capture protein-protein interactions in living cells. Chem. 2019;5(11):2955–2968. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lai TS, Lin CJ, Greenberg CS. Role of tissue transglutaminase-2 (TG2)-mediated aminylation in biological processes. Amino Acids. 2017;49(3):501–515. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Martins IM, Matos M, Costa R, et al. Transglutaminases: recent achievements and new sources. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(16):6957–6964. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kieliszek M, Misiewicz A. Microbial transglutaminase and its application in the food industry. A review. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2014;59(3):241–250. doi: 10.1007/s12223-013-0287-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein-protein interactions. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25(4):663–682. doi: 10.1002/mas.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bora JR, Mahalakshmi R. Photoradical-mediated catalyst-independent protein cross-link with unusual fluorescence properties. Chembiochem. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202300380. Published online 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reddy N, Reddy R, Jiang Q. cross-linking biopolymers for biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33(6):362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jayachandran B, Parvin TN, Alam MM, Chanda K, Mm B. Insights on chemical cross-linking strategies for proteins. Molecules. 2022;27(23):8124. doi: 10.3390/molecules27238124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Spicer CD, Pashuck ET, Stevens MM. Achieving controlled biomole-culebiomaterial conjugation. Chem Rev. 2018;118(16):7702–7743. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Partlow BP, Applegate MB, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Dityrosine cross-linking in designing biomaterials. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2(12):2108–2121. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Heidary M, Kaviar VH, Shirani M, et al. A comprehensive review of the protein subunit vaccines against COVID-19. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:927306. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.927306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hong S, Choi DW, Kim HN, Park CG, Lee W, Park HH. Protein-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(7):604. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12070604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tsoras AN, Champion JA. Cross-linked peptide nanoclusters for delivery of oncofetal antigen as a cancer vaccine. Bioconjug Chem. 2018;29(3):776–785. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Malecki J, Muszynski S, Solowiej BG. Proteins in food systems-bionanomaterials, conventional and unconventional sources, functional properties, and development opportunities. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13(15):2506. doi: 10.3390/polym13152506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Friedman M. Chemistry, biochemistry, nutrition, and microbiology of lysinoalanine, lanthionine, and histidinoalanine in food and other proteins. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47(4):1295–1319. doi: 10.1021/jf981000+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ter Huurne GM, Voets IK, Palmans ARA, Meijer EW. Effect of intra-versus intermolecular cross-linking on the supramolecular folding of a polymer chain. Macromolecules. 2018;51(21):8853–8861. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Magon NJ, Turner R, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Cross-linking between cysteine and lysine, tryptophan or tyrosine in peptides and proteins treated with hypochlorous acid and other reactive halogens. Redox Biochem Chem. 2023;1–2:100002 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.