Summary

Background

Adiposity can be measured using BMI (which is based on weight and height) as well as indices of abdominal adiposity. We examined the association between BMI and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) within and across populations of different world regions and quantified how well these two metrics discriminate between people with and without hypertension.

Methods

We used data from studies carried out from 1990 to 2023 on BMI, WHtR and hypertension in people aged 20–64 years in representative samples of the general population in eight world regions. We graphically compared the regional distributions of BMI and WHtR, and calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients between BMI and WHtR within each region. We used mixed-effects linear regression to estimate the extent to which WHtR varies across regions at the same BMI. We graphically examined the prevalence of hypertension and the distribution of people who have hypertension both in relation to BMI and WHtR, and we assessed how closely BMI and WHtR discriminate between participants with and without hypertension using C-statistic and net reclassification improvement (NRI).

Findings

The correlation between BMI and WHtR ranged from 0·76 to 0·89 within different regions. After adjusting for age and BMI, mean WHtR was highest in south Asia for both sexes, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean and the region of central Asia, Middle East and north Africa. Mean WHtR was lowest in central and eastern Europe for both sexes, in the high-income western region for women, and in Oceania for men. Conversely, to achieve an equivalent WHtR, the BMI of the population of south Asia would need to be, on average, 2·79 kg/m2 (95% CI 2·31–3·28) lower for women and 1·28 kg/m2 (1·02–1·54) lower for men than in the high-income western region. In every region, hypertension prevalence increased with both BMI and WHtR. Models with either of these two adiposity metrics had virtually identical C-statistics and NRIs for every region and sex, with C-statistics ranging from 0·72 to 0·81 and NRIs ranging from 0·34 to 0·57 in different region and sex combinations. When both BMI and WHtR were used, performance improved only slightly compared with using either adiposity measure alone.

Interpretation

BMI can distinguish young and middle-aged adults with higher versus lower amounts of abdominal adiposity with moderate-to-high accuracy, and both BMI and WHtR distinguish people with or without hypertension. However, at the same BMI level, people in south Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the region of central Asia, Middle East and north Africa, have higher WHtR than in the other regions.

Funding

UK Medical Research Council and UK Research and Innovation (Innovate UK).

Introduction

Adiposity can be measured using weight-to-height indices (eg, BMI) or indices of abdominal obesity such as waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR). Some studies found that abdominal adiposity was a better predictor of cardio-metabolic outcomes than BMI, whereas others found similar associations. At any BMI level, the extent of abdominal adiposity can vary both within and across populations due to differences in fat and muscle mass and their distributions. For example, some studies have stated that, at any BMI level, Asian populations have higher levels of abdominal obesity than European and African populations.1–5 Current data on the relationship between BMI and abdominal obesity, and their association with health outcomes, typically cover one or a small number of countries or regions. Therefore, it has not been possible to systematically and consistently investigate how the relationship between BMI and abdominal obesity varies across global populations.6

We used a global database of population-based studies to quantify in a consistent way how BMI and WHtR are related within and across different world regions. We further examined the relationship of BMI and WHtR with hypertension and mean blood pressure, and measured how well the two adiposity indices predict prevalent hypertension. Through these analyses, we evaluated whether BMI can distinguish between those with lower versus higher WHtR, and predict the risk of having hypertension as well as WHtR.

Methods

Study design

We pooled and analysed population-based studies with data on height, weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, and use of antihypertensive medicines. We used BMI as an index of general adiposity and WHtR as an index of abdominal obesity. We used WHtR because it is a better predictor of cardiometabolic risk than waist circumference and WHR,7–13 due to accounting for height, which influences overall body size. This feature is particularly relevant in a global analysis, because height varies substantially across global populations.14 We show results using waist circumference in the appendix (pp 85–97, 104–109, 116–141) for comparison. We did not analyse WHR because some studies with data on waist circumference did not measure hip circumference.

We analysed hypertension as an outcome of obesity because it is a consequence of obesity and a leading global risk factor15 for cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and dementia. Blood pressure is also more commonly measured in population-based studies15 than diabetes, cholesterol, and kidney disease, which require laboratory analysis. Furthermore, with data on systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hypertension could be defined consistently in all studies,15 whereas diabetes studies differ on whether they have data on fasting glucose or HbA1c.16 Pooled data were examined graphically and analysed using regression models as detailed below.

Data

We used individual participant data from representative samples of the general population, collated by the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC), as detailed previously and in appendix (pp 35–36).15,17

We used data on adults aged 20–64 years from 837 studies with mid-year from 1990–2023. From each study, we used the data recorded in the sex variable. The studies might have varied in their protocol and terminology related to recording of sex or gender. To harmonise the data, we have used women and men throughout this paper. A list of data sources and their characteristics is provided in the appendix (pp 40–53). Studies from earlier years were not used because fewer studies had data on waist circumference. Older age groups were excluded because there were fewer participants in many regions. We had at least one data source for 181 countries (appendix pp 57–58), where 98·3% of the world population in 2023 lived. These countries were grouped into eight regions (appendix p 39). The number of studies per region ranged from 40 in Oceania to 189 in the high-income western region (appendix p 54). Of the 837 studies with data on BMI and WHtR, 710 (85%) also had data on hypertension. The other studies did not collect data on blood pressure as their primary intent and design. In particular, some population-based nutrition surveys collected anthropometric data but not blood pressure (appendix pp 40–53).

Details of data cleaning are provided in the appendix (pp 37, 59–60). After data cleaning, there remained 7·5 million participants aged 20–64 years with data on height, weight, and waist circumference; 5·4 million of these participants (72·2% of all participants with height, weight, and waist circumference data) also had data on blood pressure and hypertension treatment. In studies with data on blood pressure, the difference in mean BMI and WHtR of participants with and without blood pressure data was 0·49 kg/m2 and 0·01; the difference in mean age was 0·1 years.

When multiple measurements of blood pressure were taken, we removed the first measurement and averaged the remaining readings. Hypertension was defined as having systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mmHg or greater, having diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mmHg or greater, or taking anti-hypertensive medication.15 We also used data on antihypertensive medicines to investigate whether the relationship between BMI or WHtR and blood pressure differed between participants who were treated for hypertension and those who were not. Treated hypertension was defined as current use of anti-hypertensive medication, regardless of blood pressure. Untreated hypertension was defined as having SBP 140 mmHg or greater or DBP 90 mm Hg or greater without the use of anti-hypertensive medication.

Statistical analysis

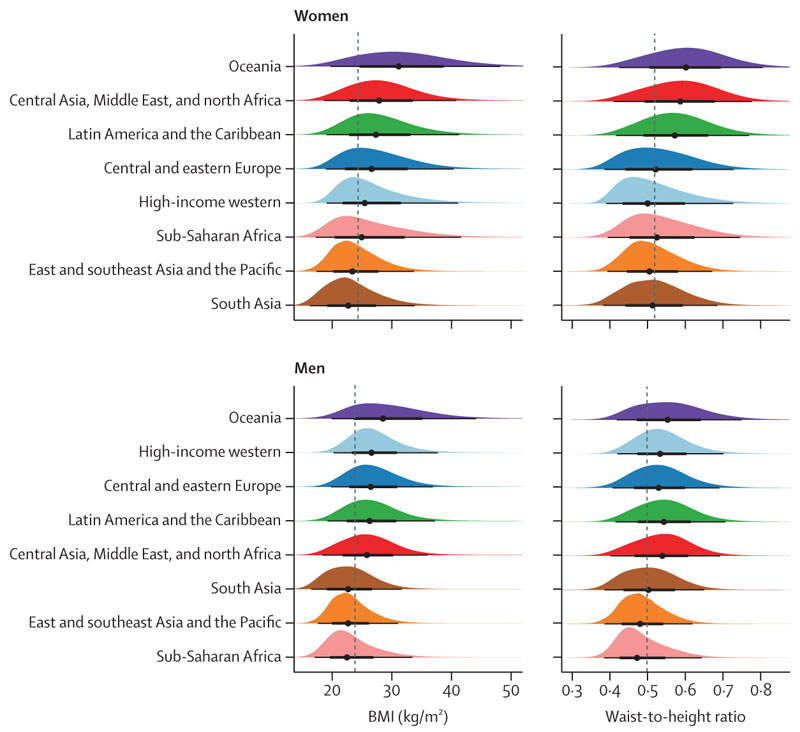

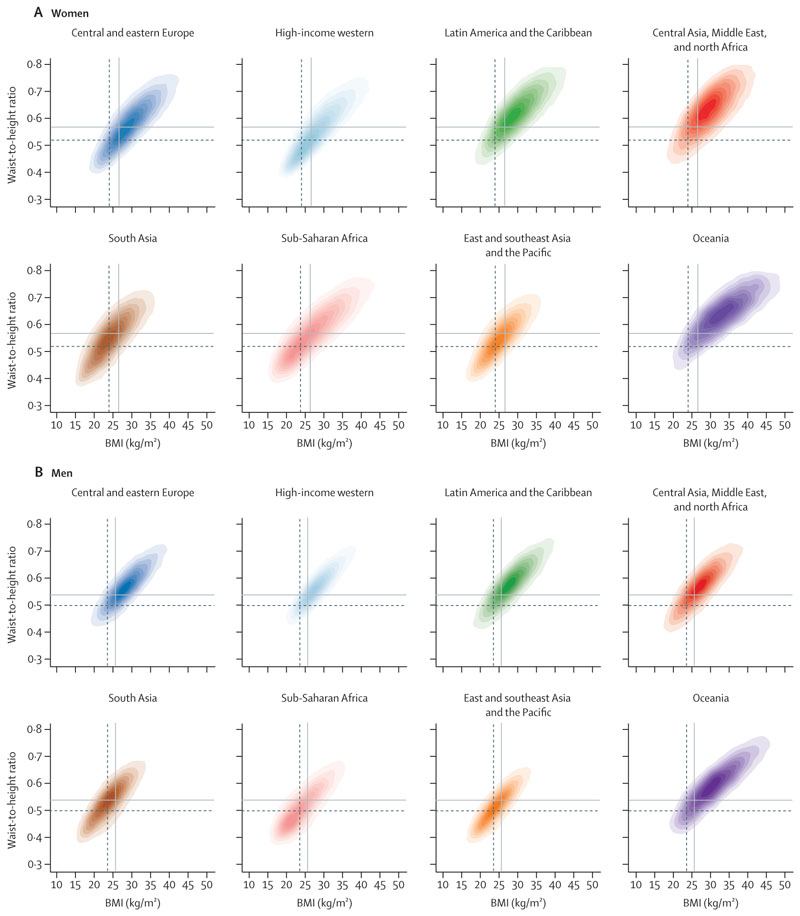

All analyses were done separately for men and women because there are differences in adiposity and hypertension between them.15,17 We graphically and numerically compared the regional distributions of BMI and WHtR to evaluate how they were distributed in each region relative to others (figure 1, appendix p 55). We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient between BMI and WHtR in each region to examine their relationship within regions (figure 2).

Figure 1. Distributions of BMI and waist-to-height ratio, by region.

The black lines below each distribution show the 2·5%, 25·0%, 75·0%, and 97·5% quantiles of the distributions and the points show the median. The dashed lines show medians across all participants. Regions are ordered by their sex-specific median BMI. See appendix (p 55) for numerical summaries.

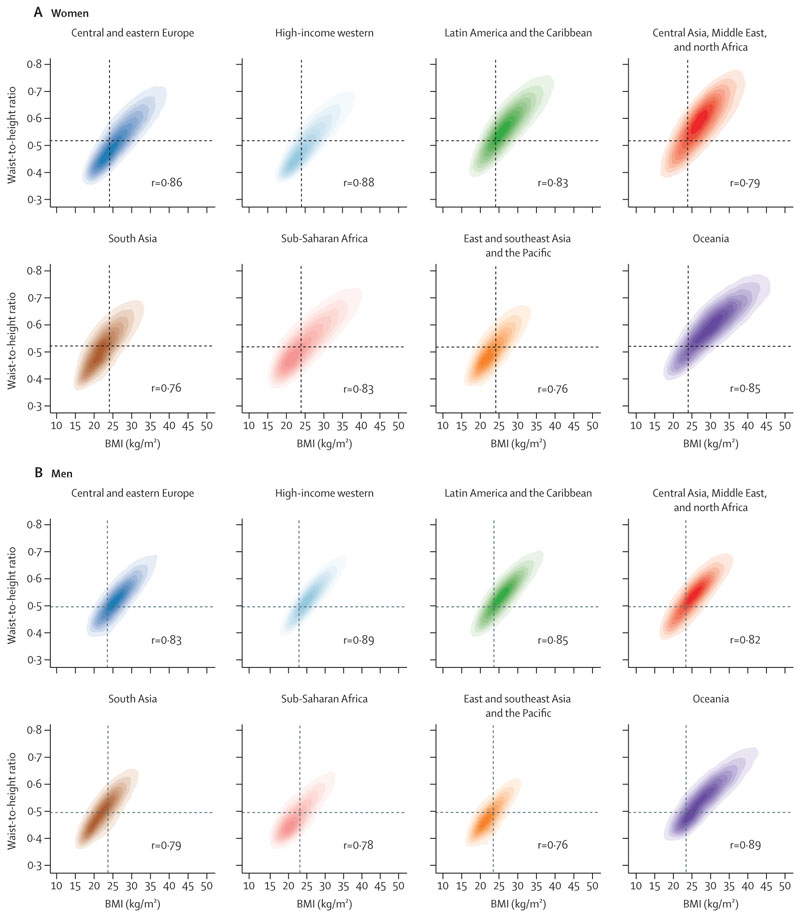

Figure 2. Relationship between waist-to-height ratio and BMI, by region.

The shading indicates the density of participants in each region, with darker shades corresponding to more participants and vice versa. Pearson correlation coefficients between BMI and waist-to-height ratio in each region are shown in the panels. The vertical dashed line shows median BMI for all participants globally, the horizontal dashed line shows median waist-to-height ratio for all participants globally. See appendix (pp 85–87) for results using waist circumference.

We used mixed-effects linear regression to estimate the extent to which WHtR varied across regions at any BMI level (appendix pp 61–62). The dependent variable was WHtR and the independent variables were BMI, age, and region. We adjusted for age because BMI and WHtR vary with age. We used age and BMI as linear terms, because their inclusion as categorical terms, with each category covering different age and BMI ranges, led to similar conclusions compared with linear terms for the BMI range that contained most participants (~17·5–47·5 kg/m2). The use of linear terms has the additional advantage of simplifying the presentation of results. Comparison of linear and categorical BMI terms at the global level indicates that at very high BMI levels, approximately 47·5 kg/m2 and higher, WHtR rises more slowly than predicted by linear BMI (appendix pp 63–64). The opposite happens at very low BMIs of around 17·5 kg/m2 and lower. We used random intercepts at the study level to account for unmeasured study level factors that might have influenced BMI or WHtR (these models are also known as multi-level, with individuals nested in studies).

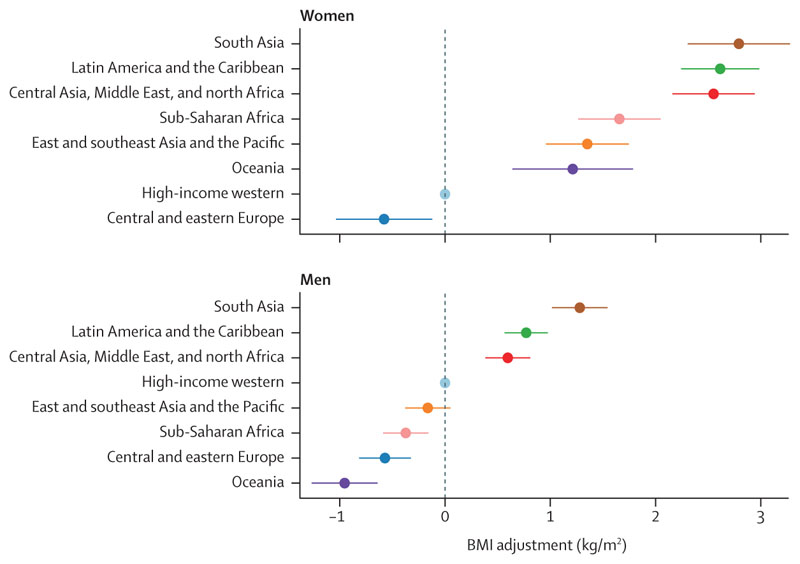

We report the difference across regions in WHtR at the sex-specific global mean BMI level. We used the regression coefficients to calculate how much lower or higher BMI would need to be for each region’s population to have the same WHtR; we refer to this quantity as regional BMI adjustment (figure 3). We estimated the 95% CIs of regional BMI adjustment based on the uncertainty of the model coefficients, accounting for the covariance matrix of the fixed effects.

Figure 3. Regional BMI adjustment.

The BMI adjustment shows how much lower BMI in each region should be to achieve an equivalent waist-to-height ratio. The adjustment is shown relative to the population of the high-income western region where most current epidemiological studies have been done; regional ordering and differences across regions would be unchanged if a different reference were used. The bars show 95% CIs of the BMI adjustments. See appendix (pp 90–91) for results using waist circumference.

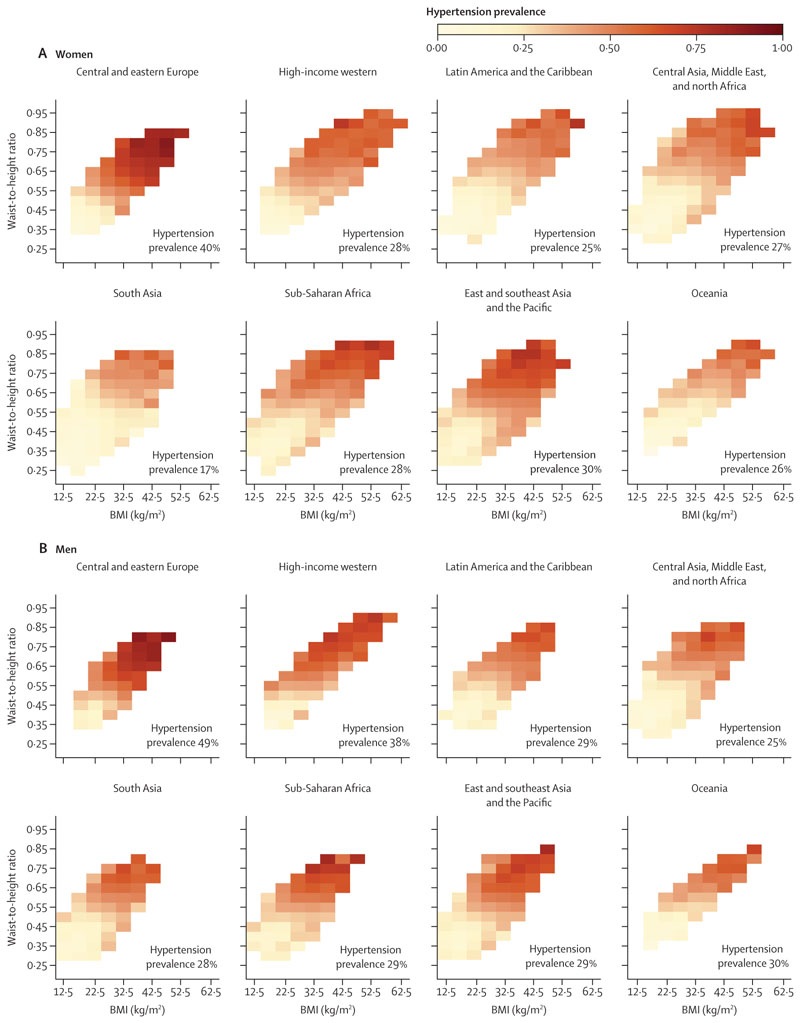

We graphically examined the prevalence of hypertension and the distribution of the number of people who have hypertension, both in relation to BMI and WHtR in each region. The first presentation quantifies the association of hypertension prevalence with BMI and WHtR, regardless of the distributions of BMI and WHtR in the regional population. The second presentation also takes into account the distributions of BMI and WHtR in the regional population (figures 4, 5).

Figure 4. Prevalence of hypertension at different levels of waist-to-height ratio and BMI, by region.

Cells with 30 or fewer participants have been excluded from the figure because the results are less stable than at larger numbers. The number on each panel indicates the crude prevalence of hypertension among all participants in each region. See appendix for separate results for untreated and treated hypertension (pp 98–103) and for results using waist circumference (pp 92–94, 104–109).

Figure 5. Distribution of participants with hypertension in relation to BMI and waist-to-height ratio, by region.

The shading indicates the density of participants with hypertension in each region, with darker shades corresponding to more participants. The vertical lines show median BMI and horizontal lines show median waist-to-height ratio for all participants (dashed lines) and those with hypertension (solid lines) globally. See appendix for separate results for untreated and treated hypertension (pp 110–115) and for results using waist circumference (pp 95–97, 116–121).

We also assessed how well BMI and WHtR predict individuals’ hypertension status in each region using the C-statistic and the continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) metrics. C-statistic measures the extent to which the use of BMI, WHtR, or both results in a participant with hypertension having a predicted probability higher than a participant without hypertension, whereas NRI measures the improvement made in the prediction of hypertension status by regression models with BMI, WHtR, or both, compared with a null model with neither. C-statistic and NRI were estimated from mixed effects logistic regressions that also included age, region, and study year, because hypertension prevalence varies by these factors.15 We included age as a linear term because exploratory analyses showed that the association with hypertension was linear for the age range of our analysis (20–64 years). For study year, we used categorical variables for 5-year intervals (1990–94, 1995–99, 2000–04, 2005–09, 2010–14, 2015–19, and 2020–23) because hypertension trends were nonlinear in some regions.15 We used interaction terms between region and age and between region and year to account for differences across regions in age associations and time trends. We tested but did not include an interaction between BMI and WHtR because its inclusion did not improve C-statistic or NRI. We also included study-level random intercepts to account for unobserved study level factors, such as sampling and measurement method, that might affect hypertension prevalence. In addition to C-statistic and NRI, we report the odds ratio (OR) for prevalent hypertension per SD of BMI and of WHtR without mutual adjustment, from regressions that had each metric alone; we also report ORs with mutual adjustment, from regressions that included both metrics.

All analyses were done using R version 4.3.2. The pooled analysis was approved by Imperial College London Research Ethics Committee and complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The participating studies followed their institutional approval and consent process.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the paper.

Results

The distributions of BMI and WHtR differed across regions and between sexes. For both sexes, BMI distributions in the three regions of south Asia, east and southeast Asia and the Pacific, and sub-Saharan Africa had lower medians and were shifted towards lower values compared with other regions (figure 1, appendix p 55). In contrast, WHtR distributions in these three regions overlapped more closely with those of other regions than was the case for their BMI distributions. For women, WHtR distribution in these three regions coincided closely with those of the high-income western region and central and eastern Europe. For men, the medians of the WHtR distributions of these three regions were ordered in the same way as for BMI, but the distribution in south Asia was more similar to other regions than was the case for BMI.

Oceania exhibited distributions of BMI with higher medians and quartiles compared with those in other regions. Oceania was followed by central Asia, Middle East and north Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean for women, and by the high-income western region and central and eastern Europe for men. For women, the same regions also had the highest median WHtR, although Oceania’s WHtR distribution overlapped more closely with other regions than its BMI distribution. For men, the WHtR distributions were similar for the top five regions. In all regions, BMI and WHtR distributions of women had wider distributions than those of men.

The correlation coefficients between BMI and WHtR ranged from 0·76 to 0·89 in the two sexes across different regions—ie, within each region, BMI and WHtR were strongly, but not perfectly, correlated (figure 2). After adjusting for age and BMI, mean WHtR was highest in south Asia for both sexes, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean and the region of central Asia, Middle East, and north Africa (appendix pp 61–62). BMI-adjusted mean WHtR was lowest in central and eastern Europe for both sexes, high-income western region for women, and Oceania for men. The remaining regions showed no clear ordering for either sex. In all regions, after adjusting for age and BMI, mean WHtR was higher in women than in men.

To achieve an equivalent WHtR, those in south Asia need to have BMI that was, on average, 2·79 kg/m2 (95% CI 2·31–3·28) lower for women and 1·28 kg/m2 (1·02–1·54) lower for men than the population of the high-income western region (figure 3). The next largest BMI adjustments were for Latin America and the Caribbean (women: 2·61 [2·24–2·98] kg/m2, men: 0·77 [0·57–0·98] kg/m2) and the region of central Asia, Middle East, and north Africa (women: 2·55 [2·16–2·94] kg/m2, men: 0·60 [0·38–0·81] kg/m2). For both sexes, BMI adjustment for east and southeast Asia and the Pacific was smaller than that of south Asia, and for men its 95% CI contained the null value of zero. BMI adjustments to achieve the same WHtR were larger for women than men in all regions, although in central and eastern Europe the 95% CIs for the two sexes overlapped.

Although total hypertension prevalence varied across regions, in every region prevalence increased with both BMI and WHtR (figure 4). For low BMI (≤22·5 kg/m2) and WHtR (≤0·40), hypertension prevalence was 25% or less in all regions, except for men in sub-Saharan Africa where one BMI–WHtR combination within this range had a prevalence of 26%. In some BMI–WHtR region combinations in this range, prevalence was less than 15%. At high BMI (≥37·5 kg/m2) and WHtR (≥0·75), hypertension prevalence was 39% or higher for women and 49% or higher for men in all regions; in central and eastern Europe, it was 80% or higher for both men and women. The positive associations with BMI and WHtR were also seen for mean SBP and DBP among all participants (appendix pp 65–70) and in those who did not use anti-hypertensive medication (appendix pp 71–76). However, there was either no association or weak association between BMI or WHtR and mean SBP or DBP among participants on anti-hypertensive medication (appendix pp 77–82).

Models that included BMI alone and WHtR alone predicted hypertension status with similar C-statistics (0·74–0·78) and NRIs (0·41–0·44) when data from all regions were used (table). Regional models varied in their predictive performance, with higher C-statistics and NRIs in central and eastern Europe, the high-income western region, and Latin America and Caribbean for both sexes and in Oceania for men, and lower C-statistics and NRIs in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa for both sexes. However, in every region, the ability to predict prevalent hypertension was virtually identical between models that included either adiposity measure (ie, similar C-statistic and NRI for models with either BMI or WHtR). Globally and within each region, including both BMI and WHtR led to little improvement in C-statistic and NRI compared with using either measure alone. Model C-statistics were consistently higher for women than men. ORs for both sexes for having hypertension per SD of BMI and WHtR were nearly identical (~1·7) without mutual adjustment (appendix pp 83–84). When both measures were included in the regression, BMI had a slightly larger OR per SD (1·39 [1·38–1·40] for BMI vs 1·33 [1·32–1·34] for WHtR for women; 1·38 [1·37–1·39] for BMI vs 1·32 [1·32–1·33] for WHtR for men).

The BMI and WHtR ranges where the density (ie, absolute number) of participants with hypertension was greatest varied across regions (figure 5). This variation occurred because the distributions of these two adiposity indices varied across regions (figures 1, 2). Specifically, in populations with lower BMI and WHtR distributions relative to other regions (both sexes in the east and southeast Asia and Pacific region; men in sub-Saharan Africa), more people with hypertension were concentrated in the lower range of BMI and WHtR, and vice versa (Oceania and the region of central Asia, Middle East, and north Africa). This finding is analogous to Rose’s phenomenon that most cases arise from ranges that contain the most people, not where the highest risk is. For example, 45% of men with hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or lower and a WHtR of 0·5 or lower. In contrast, in Oceania, this range accounted for only 10% of men with hypertension; rather, to reach a similar percentage of men with hypertension, BMI and WHtR would have to exceed around 30 kg/m2 and 0·65. In south Asia, people with hypertension were more concentrated towards lower BMI, but not WHtR, because in this region WHtR is higher at equivalent BMI levels compared with other regions (figure 2). In every region, density of those with treated hypertension was shifted towards higher BMI and WHtR compared with those who were not treated—ie, among participants with hypertension, those with higher BMI and WHtR were more likely to be treated than those with lower values (appendix pp 110–115).

Discussion

In this global study, with data representative of the populations of all world regions, we found that BMI and WHtR were correlated at the individual level within all regions. In every region, BMI and WHtR predicted prevalent hypertension equally well. However, at any BMI level, WHtR was highest in south Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and central Asia, Middle East, and north Africa (especially for women), and lowest in central and eastern Europe and, for men, in Oceania.18

The main strength of our study is its global data and scope, which allowed comparison across regions. With a large number of studies and participants, we could robustly quantify how BMI and WHtR were associated both within and across regions, and how they were associated with hypertension prevalence. We maintained a high standard of data quality through careful checks of study sample and characteristics and, to avoid bias, we did not use self-reported data. Data were analysed according to a consistent protocol. Our study is also affected by limitations that apply to data pooling analyses, especially those that use data collected in different countries and time periods. Despite using substantially more data than previous studies, some regions, such as Oceania, had fewer studies, although even in this region we had data on 63 000 participants from 40 studies. Furthermore, we did not have sufficient data to include those older than 64 years, at which point BMI and WHtR might diverge due to age-related loss of muscle mass and decreases in height. We also did not have data on direct measures of body composition or fat distribution because such data require more complex measurements, which are not feasible in population surveillance, especially when health-care resources are limited. Although we only used studies with measurements of height, weight, and waist circumference following validated methods, unobserved differences might remain due to differing methods and implementation. We attempted to mitigate these differences by including study-level random effects in our models, which adjust for the influence of unobserved differences across studies. Finally, beyond hypertension, future research should investigate the similarities and differences in how BMI and abdominal adiposity are associated with conditions such as diabetes and kidney and liver disease in global populations.

That the populations of some regions had higher WHtR at similar BMI levels might be due to differences in genetics, smoking, diet, and exercise, which can differentially affect muscle and fat mass and their distributions.19 The differing WHtRs might also be due to phenotypic differences related to early-life nutrition, which affects body build, especially height and trunk height relative to leg height, which in turn influences the balance and distribution of lean and fatty body mass. In particular, populations in south Asia, where WHtR was higher than other regions at a similar BMI, have some of the lowest worldwide heights.14

The larger WHtR at any BMI level in women compared with men, and the variations in this sex difference across regions, could be due to at least three factors. First, body fat distribution is affected by sex hormones,19 which themselves vary across populations due to genetics, nutrition, environment, and social roles. Second, these regional sex differences could be due to differences in reproductive behaviours, including age at first child and total fertility rate, which might differentially affect waist circumference and weight.20 Finally, these differences might be due to sex differences in nutrition. The wider distributions of BMI and WHtR among women compared with men might additionally be because the social gradient and geographical variation in obesity is larger in women than men.17,21,22

The similarity of BMI and WHtR in predicting prevalent hypertension, which is consistent with studies in specific countries,23–26 could be due to two reasons. First, WHtR and BMI were correlated within regional populations. Second, the potential mechanisms for adiposity-induced hypertension, including insulin resistance, inflammation, and increased leptin leading to arterial stiffness; higher sympathetic nervous system activity; and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system with increased sodium reabsorption might be similar for general and abdominal adiposity.27,28 The weak association of BMI and WHtR with blood pressure among those who used antihypertensive medicines could be because treatment weakens these mechanisms, and because patients with higher BMI and WHtR are more likely to be treated (appendix pp 110–115) and treated at higher doses or with a larger number of antihypertensive medicines.

The within-region correlations of BMI and WHtR indicate that, within regional populations, BMI can distinguish young and middle-aged adults with higher versus lower amounts of abdominal adiposity with moderate-to-high accuracy. Weight is also easier to measure than waist circumference in primary-care facilities and in population health surveys, and in some cultural settings it is more acceptable. Waist circumference might be measured with larger error. These features make BMI an appropriate, and in some settings preferred, metric for opportunistic risk screening and monitoring changes in obesity in primary care and in public health surveillance, especially if our results on the similarity of their performance in predicting hypertension are replicated for other conditions. Specialist obesity clinics will inevitably use a larger and more complex set of measures to decide on interventions, such as bariatric surgery and new obesity medicines to monitor patients’ outcomes. At the same time, the cross-region differences in the relationship indicate that some populations—especially those from south Asia—have higher amounts of abdominal adiposity at lower BMI levels, especially women. This finding might justify different thresholds for further screening if guideline committees consider that region-specific and sex-specific thresholds can be implemented in primary-care settings.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for articles published from database inception up to March 27, 2024, with no language restrictions, using the following search terms: (“obesity”[mh:noexp] OR “overweight”[mh:noexp] OR “body size”[mh:noexp] OR “body height”[mh:noexp] OR “body weight”[mh:noexp] OR “thinness”[mh:noexp] OR “waist-hip ratio”[mh:noexp] or “waist circumference”[mh:noexp] or “body mass index” [mh:noexp]) AND (“humans”[mh]) AND (“health surveys”[mh] OR “epidemiological monitoring”[mh] OR “prevalence”[mh]) AND (“global*” OR “worldwide”) NOT “patient*”[Title] NOT comment[ptyp] NOT case reports[ptyp]. Articles were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the methods. We also reviewed the report of a WHO expert consultation on abdominal adiposity. We found studies either in one country or several countries that had compared BMI with different indices of abdominal adiposity, and had analysed their separate and combined associations, with incident or prevalent cardiometabolic outcomes. We also found one study that recruited patients from primary care facilities in 63 countries, and compared the associations of BMI and waist circumference with diagnosed cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, in countries with limited health-care access and utilisation, a substantial proportion of people with these conditions might be undiagnosed. Some studies found that measures of abdominal adiposity were a better predictor of cardiometabolic outcomes than BMI, whereas others found similar associations. The classification of regions where the participants came from, or their ethnicity, varied across these studies, and many did not distinguish between different parts of Asia (eg, east, south, and west Asia). We did not find any population-based study that had participants from all world regions. A comparison of our findings with these studies is presented in the appendix (p 38).

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses population-based data from all major regions of the world to evaluate how much BMI represents the extent of abdominal adiposity in different global populations, and measures how BMI and abdominal adiposity predict hypertension status, a major global cardiovascular risk. With numerous studies and millions of participants, we could consistently and robustly quantify these relationships in all world regions.

Implications of all the available evidence

Within regional populations, BMI can distinguish individuals with higher versus lower amounts of abdominal adiposity, and is appropriate for opportunistic risk screening and monitoring changes in adiposity in surveillance and primary care. However, some populations, especially those from south Asia, have higher amounts of abdominal adiposity relative to other regions at equivalent BMI levels, especially women.

Table. C-statistics and continuous NRIs for hypertension from three logistic models using BMI, waist-to-height ratio, and both.

| Women | Men | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-statistic | NRI | C-statistic | NRI | ||||||||||||

| BMI | Waist-to-height ratio | Both | BMI | Waist-to-height ratio | Both | BMI | Waist-to-height ratio | Both | BMI | Waist-to-height ratio | Both | ||||

| Central and eastern Europe | 0·810 | 0·810 | 0·813 | 0·568 | 0·560 | 0·581 | 0·765 | 0·763 | 0·767 | 0·467 | 0·458 | 0·481 | |||

| High-income western | 0·788 | 0·791 | 0·791 | 0·512 | 0·519 | 0·528 | 0·757 | 0·758 | 0·760 | 0·439 | 0·437 | 0·452 | |||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 0·808 | 0·807 | 0·809 | 0·445 | 0·431 | 0·454 | 0·765 | 0·764 | 0·766 | 0·445 | 0·436 | 0·453 | |||

| Central Asia, Middle East, and north Africa | 0·791 | 0·791 | 0·793 | 0·395 | 0·400 | 0·414 | 0·755 | 0·753 | 0·757 | 0·405 | 0·405 | 0·420 | |||

| South Asia | 0·749 | 0·748 | 0·751 | 0·389 | 0·365 | 0·405 | 0·720 | 0·720 | 0·724 | 0·397 | 0·404 | 0·421 | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0·781 | 0·783 | 0·784 | 0·347 | 0·365 | 0·371 | 0·735 | 0·735 | 0·737 | 0·344 | 0·355 | 0·366 | |||

| East and southeast Asia and the Pacific | 0·755 | 0·752 | 0·757 | 0·456 | 0·437 | 0·471 | 0·718 | 0·715 | 0·721 | 0·433 | 0·420 | 0·446 | |||

| Oceania | 0·786 | 0·783 | 0·787 | 0·416 | 0·410 | 0·435 | 0·744 | 0·745 | 0·747 | 0·455 | 0·456 | 0·465 | |||

| Global | 0·780 | 0·779 | 0·782 | 0·440 | 0·427 | 0·454 | 0·741 | 0·740 | 0·744 | 0·421 | 0·414 | 0·434 | |||

NRI values were calculated relative to a logistic regression model using no adiposity measure. All models included terms for age and study year, and the global model included region. Regional models used only the data from that region. The appendix (p 56) shows results using waist circumference. NRI=net reclassification improvement.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (grant number MR/V034057/1) and UK Research and Innovation (Innovate UK grant number 10103595, for participation in the OBCT consortium funded by the EU grant agreement 101080250). KK and FZ are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. EWG is supported by Science Foundation Ireland (grant number 22/RP/10091). BZ is supported by a fellowship from the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics at Imperial College London, funded by a donation from Community Jameel. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution license to the Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. We thank Matthias Schulze for comments on earlier drafts of the paper. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this Article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Footnotes

Contributors

Members of the country and regional data group collected data and checked pooled data for accuracy of information about their study and other studies in their country. BZ, RKS, RAH, LJ, RMC-L, KES, VPFL, NHP, AM, GAS, AWR, AB-P, and MLCI collated, checked, and harmonised data from participating studies. APW, BZ, JEB, AM, and ME developed the statistical approach. APW, BZ, JEB, and NI conducted statistical analyses and prepared results. ME, JEB, BZ, and APW wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from other members of the pooled analysis and writing group. Members of the country and regional data group commented on the draft manuscript. Members of the country and regional data group had access to and verified data from individual participating studies. BZ, JEB, RKS, and RAH had access to and verified the pooled data used in the analysis. The corresponding author had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests

MW reports consulting fees from Freeline, outside of the submitted work. MDC reports consulting fees paid as part of the Independent Expert Group of the Global Nutrition Report and support for attending meetings and travel from Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand and from the World Heart Federation, all outside of the submitted work. KK reports grants in support of investigator and investigator initiated trials from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Boehringer Ingelheim; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Oramed Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Roche, and Applied Therapeutics; and payments for speaking from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Oramed Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Roche, and Applied Therapeutics, all outside of the submitted work. LL reports research centre funds paid to their institution by Forte, Sweden. JES reports payments for lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Zuellig Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, and Abbott and payments for a program committee from AstraZeneca, outside of the submitted work. SS reports honoraria for speaking, support for attending meetings and travel and participation on a Scientific Board Exposure study from Jansen, outside of the submitted work. FZ reports consulting fees from Daiichi Sankyo. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC):

Pooled analysis and writing and Country and regional data

Data sharing

Data used in this research are governed by data-sharing protocols of participating studies. Contact information for data providers can be obtained from www.ncdrisc.org upon the publication of the paper. Computer code and meta-data for data sources used in the study are also available from the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/records/12744326). Data governance and sharing agreements do not permit the sharing of individual participant data; contact information for data request is provided for all data sources used in the study.

References

- 1.WHO. [accessed April 3, 2024];Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO Expert Consultation. 2008 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501491 .

- 2.Deurenberg-Yap M, Schmidt G, van Staveren WA, Deurenberg P. The paradox of low body mass index and high body fat percentage among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1011–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CH, Heshka S, Wang J, et al. Truncal fat in relation to total body fat: influences of age, sex, ethnicity and fatness. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2007;31:1384–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lear SA, James PT, Ko GT, Kumanyika S. Appropriateness of waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio cutoffs for different ethnic groups. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:42–61. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lear SA, Humphries KH, Kohli S, Chockalingam A, Frohlich JJ, Birmingham CL. Visceral adipose tissue accumulation differs according to ethnic background: results of the Multicultural Community Health Assessment Trial (M-CHAT) Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:353–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li WC, Chen IC, Chang YC, Loke SS, Wang SH, Hsiao KY. Waist-to-height ratio, waist circumference, and body mass index as indices of cardiometabolic risk among 36,642 Taiwanese adults. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0286-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13:275–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai L, Liu A, Zhang Y, Wang P. Waist-to-height ratio and cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese adults in Beijing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayawardana R, Ranasinghe P, Sheriff MH, Matthews DR, Katulanda P. Waist to height ratio: a better anthropometric marker of diabetes and cardio-metabolic risks in South Asian adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:292–99. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasdar Y, Moradi S, Moludi J, et al. Waist-to-height ratio is a better discriminator of cardiovascular disease than other anthropometric indicators in Kurdish adults. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16228. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petermann-Rocha F, Ulloa N, Martínez-Sanguinetti MA, et al. Is waist-to-height ratio a better predictor of hypertension and type 2 diabetes than body mass index and waist circumference in the Chilean population? Nutrition. 2020;79-80:110932. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware LJ, Rennie KL, Kruger HS, et al. Evaluation of waist-to-height ratio to predict 5 year cardiometabolic risk in sub-Saharan African adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:900–07. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) A century of trends in adult human height. elife. 2016;5:e13410. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Global variation in diabetes diagnosis and prevalence based on fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c. Nat Med. 2023;29:2885–901. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02610-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024;403:1027–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinburn BA, Ley SJ, Carmichael HE, Plank LD. Body size and composition in Polynesians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:1178–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank AP, de Souza Santos R, Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Determinants of body fat distribution in humans may provide insight about obesity-related health risks. J Lipid Res. 2019;60:1710–19. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R086975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butovskaya M, Sorokowska A, Karwowski M, et al. Waist-to-hip ratio, body-mass index, age and number of children in seven traditional societies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1622. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01916-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Cesare M, Khang Y-H, Asaria P, et al. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet. 2013;381:585–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devaux M, Sassi F. Social inequalities in obesity and overweight in 11 OECD countries. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:464–69. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyamdorj R, Qiao Q, Lam TH, et al. BMI compared with central obesity indicators in relation to diabetes and hypertension in Asians. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1622–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obesity in Asia Collaboration. Is central obesity a better discriminator of the risk of hypertension than body mass index in ethnically diverse populations? J Hypertens. 2008;26:169–77. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f16ad3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Smith M, et al. Blood pressure in relation to general and central adiposity among 500 000 adult Chinese men and women. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1305–19. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huxley R, James WPT, Barzi F, et al. Ethnic comparisons of the cross-sectional relationships between measures of body size with diabetes and hypertension. Obes Rev. 2008;9(suppl 1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116:991–1006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chrysant SG. Pathophysiology and treatment of obesity-related hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21:555–59. doi: 10.1111/jch.13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this research are governed by data-sharing protocols of participating studies. Contact information for data providers can be obtained from www.ncdrisc.org upon the publication of the paper. Computer code and meta-data for data sources used in the study are also available from the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/records/12744326). Data governance and sharing agreements do not permit the sharing of individual participant data; contact information for data request is provided for all data sources used in the study.