ABSTRACT

The ability of bacteria to interact with and respond to their environment is crucial to their lifestyle and survival. Bacterial cells routinely need to engage with extracellular target molecules, in locations spatially separated from their cell surface. Engagement with distant targets allows bacteria to adhere to abiotic surfaces and host cells, sense harmful or friendly molecules in their vicinity, as well as establish symbiotic interactions with neighboring cells in multicellular communities such as biofilms. Binding to extracellular molecules also facilitates transmission of information back to the originating cell, allowing the cell to respond appropriately to external stimuli, which is critical throughout the bacterial life cycle. This requirement of bacteria to bind to spatially separated targets is fulfilled by a myriad of specialized cell surface molecules, which often have an extended, filamentous arrangement. In this review, we compare and contrast such molecules from diverse bacteria, which fulfil a range of binding functions critical for the cell. Our comparison shows that even though these extended molecules have vastly different sequence, biochemical and functional characteristics, they share common architectural principles that underpin bacterial adhesion in a variety of contexts. In this light, we can consider different bacterial adhesins under one umbrella, specifically from the point of view of a modular molecular machine, with each part fulfilling a distinct architectural role. Such a treatise provides an opportunity to discover fundamental molecular principles governing surface sensing, bacterial adhesion, and biofilm formation.

KEYWORDS: bacterial cell surface, pili, biofilms, fimbriae, adhesins

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria are often compelled to rapidly sense and adapt to changes in their environments, which is a requirement critical to their survival in diverse settings (1–3). Environmental sensing is often performed by filamentous (long, thin, and thread-like) appendages emanating from the surface of bacteria. The extended arrangement of these filamentous appendages means that they can engage with stimuli (external molecules) at locations distant from the cell surface (1–4). These appendages are usually adhesive, allowing them to directly bind to their targets, which can range from signaling molecules, abiotic surfaces, other bacterial cells in biofilms, or even host cells during infection (5).

Despite the diversity of putative targets of surface appendages, there is an underlying similarity in architecture and arrangement of filamentous appendages present on bacterial cells. In this review, we consider different contexts of bacterial environmental sensing and adhesion, focusing on a few examples along the way to highlight similarities between bacterial surface filamentous appendages. Rather than discussing specific molecular mechanisms in one system, the main goal of this article is to consider surface appendages from a “molecular machines” perspective, to showcase common architectural principles. For more comprehensive reviews about specific types of adhesins and surface molecules, please refer to authoritative previous works by others (6, 7). We also highlight cases where the same appendage is utilized by bacteria in multiple scenarios, showing how the underlying molecular architecture of filamentous appendages is sufficient for multiple use cases.

MOLECULES MEDIATING EXTRACELLULAR CONTACT AND ADHESION IN DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

Surface sensing: binding to an abiotic surface

Characteristic surface-attached growth as well as initial stages of biofilm formation are usually associated with the adherence of bacterial cells to an abiotic surface (8). As bacterial cell surfaces are often charged, electrostatic repulsion results in bacteria being unable to stick easily to abiotic surfaces made of hydrophobic organic chemicals (6). Therefore, surface-located filamentous molecules specifically adapted for adhesion to a surface (Fig. 1A) are required to allow bacterial cells to bind to solid surfaces (6).

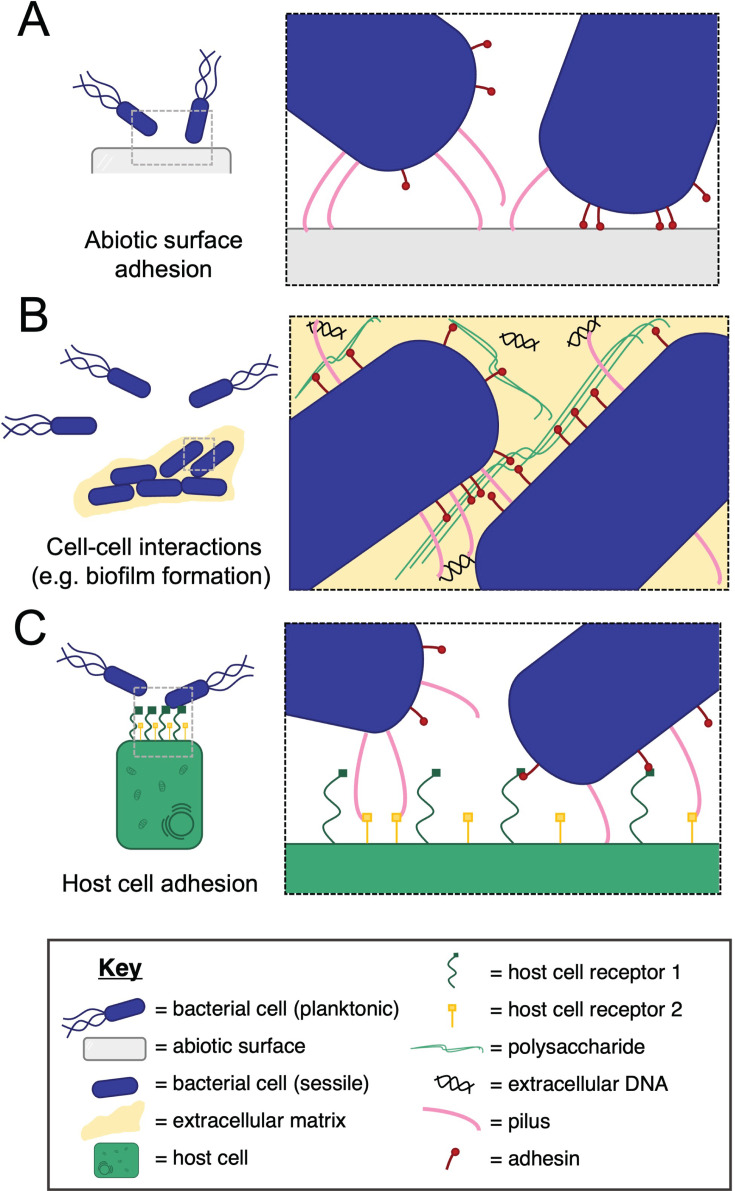

Fig 1.

Different contexts of bacterial adhesion. Different contexts in which bacterial adhesion can occur are shown schematically (key shown at the bottom). (A) Bacterial adhesion to an abiotic surface using multi-protein pili or single filamentous adhesin molecules, e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa T4P, Caulobacter crescentus Tad pilus, Paracoccus denitrificans BapA, and Bordetella pertussis FHA (9–12). (B) Bacterial adhesion to “self,” seen specifically in the context of biofilm formation. Filamentous molecules mediating this type of interaction include the Escherichia coli common pilus, Burkholderia cenocepacia cable pilus, Pseudomonas putida LapF, and Burkholderia pseudomallei BbfA (13–16). (C) Bacterial adhesion to “non-self,” seen in microbiomes or in the context of host cell infection. Examples of the filamentous molecules that interact with non-self-molecules include Corynebacterium diphtheriae SpaA-type pilus, Neisseria meningitidis T4P, Streptococcus pyogenes Sfb1, and Shigella flexneri IcsA (17–20).

A prototypical example of a class of molecules mediating surface adhesion is provided by bacterial type IV pili (T4Ps) (21). T4Ps have been characterized in a myriad of bacterial species including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Myxococcus xanthus, among others (22). Although T4Ps fulfil diverse roles including host cell interactions, a prominent role of T4Ps is mediating bacterial adherence to abiotic surfaces during the nascent stages of biofilm formation (23). In M. xanthus, T4Ps facilitate bacterial movement over solid surfaces to nutrient-dense regions for subsequent colony formation (24–26). This movement across surfaces is known as twitching motility and is facilitated by the characteristic dynamic nature of T4Ps (27, 28). T4Ps are anchored to the cell surface of the bacterium via a type IV secretion platform. In M. xanthus, this consists of proteins PilCOMNPQ and TsaP (29–32). The M. xanthus T4P is made up of multiple protein subunits of the pilin molecule PilA that extend from the cell surface (33). At the tip of the pilus, the PilY1 protein is located, which both primes the pilus for extension and facilitates adhesion (31). Finally, the pilus can dynamically extend and retract in an ATP-dependent manner, governed by cytoplasmic ATPases PilB and PilT. This allows the adhered bacteria to move toward the surface (29, 34).

Twitching motility is also observed in other Gram-negative bacteria including P. aeruginosa, N. gonorrhoeae, and N. meningitidis, where it facilitates biofilm and microcolony formation (35–37). Although not discussed in detail in this article, Gram-positive bacteria similarly use T4Ps for surface adhesion. For instance, Clostridioides difficile uses a T4P to facilitate binding to abiotic surfaces, where it can also exhibit twitching motility (38).

Although T4Ps are an example of a long-range bacterial filamentous appendage that can extend several microns away from the cell, there are other appendages that can bind to targets in closer proximity to the bacterial cell surface. For instance, LapA is a cell-surface-associated filamentous adhesin, which has also been shown to mediate abiotic surface binding in environmental pseudomonads including Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida (39–41). LapA is a 519-kilodalton-sized adhesive protein, which is arranged as multi-domain polypeptide with 37 repeated domains, each approximately 100 amino acid residues in length at the N-terminal part of the protein (42). The N-terminal part of LapA is in turn anchored at the cell surface through a type II secretion system, which consists of multiple accessory proteins (43–46). There are adhesive domains in the C-terminal region of LapA that consist of a Calx-β-domain, a von Willebrand Factor Type A domain, and seven repeat-in-toxin (RTX) domains, which are all suggested to contribute to LapA’s function in binding to abiotic surfaces (42, 47). Atomic force microscopy has shown a twofold decrease in adhesion of cells without LapA displayed on their surface (48). Although beyond the scope of this review, similar single polypeptide filamentous adhesins are observed in several bacteria. For example, the 600-nm-long, 1.5-megadalton-sized Marinomonas primoryensis ice-binding protein (MpIBP) adhesin facilitates the positioning of the bacterium in an advantageous niche in the environment at the top of the water column, where ice is found, and which is rich in nutrients and oxygen (49).

Although the two examples highlighted above facilitate bacterial adhesion over different length scales—namely, long-range adhesion by T4Ps or short-range adhesion by the polypeptide LapA—both share certain architectural characteristics. The middle part of the appendage that we refer to as an extension module is noticeably present and required in both cases. This extension module allows the appendage to stretch from the cell surface, exit the polysaccharide-rich surface of the bacterium, reaching into the extracellular milieu where interaction with a target (in this case, an abiotic surface) can occur. In the case of T4P, this extension module consists of multiple protein monomers of PilA, whereas in the case of LapA, 37 tandemly arranged N-terminal domains carry out this function of bridging the cell surface to the target molecule through the repeated domains (Fig. 1A).

Biofilm cell–cell interactions: binding to self

After initial attachment to an abiotic surface, many bacteria form surface-attached multicellular communities called biofilms (50). As the biofilm develops, cell–cell interactions become important for holding cells together and maintaining the structural integrity of the multicellular community (Fig. 1B). In mature biofilms, both long-range multi-subunit pili as well as single polypeptide filamentous adhesins play important roles in mediating these interactions (51–53).

Cell–cell interactions in P. aeruginosa biofilms are facilitated through numerous molecular mechanisms; however, the so-called archaic chaperone-usher pili (CUPs) play a central role in biofilm maturation (54). In particular, CupE pili from P. aeruginosa contribute to the mushroom shape of biofilms and aid in colony formation, stabilizing the three-dimensional architecture of the multicellular community (55, 56). CupE pili are made of multiple subunits of the CupE1 protein that each extend a so-called donor strand into the following subunit, forming an extended fiber structure (57). CupE pili are anchored in the outer membrane of the bacteria by usher protein CupE5 (57). At the tip of the CupE pili, the CupE6 adhesin has a predicted exposed hydrophobic groove, which could be important in binding to apolar substrates that are rich in the extracellular matrices of biofilms (57).

A similar principle is observed in other bacteria, for instance, Acinetobacter baumannii uses Csu pili to mediate cell–cell interactions in the developing biofilm (58). Deletions in the assembly apparatus of this pilus resulted in strains being unable to form mature biofilms on a range of surfaces (58). In a related mechanism of biofilm stabilization, C. difficile also uses T4Ps to interact with extracellular DNA (eDNA) in biofilms, which stabilizes the multicellular community (38). Slightly removed from the biochemical adhesion mechanism employed by appendages discussed in this article, we draw attention to bacterial functional amyloids (59) that stabilize biofilms in a biophysical mechanism involving filament aggregation (51, 60–64).

In addition to the long-range filaments such as CupE pili that support the assembly of mature biofilms, P. aeruginosa employs the important filamentous adhesin CdrA to mediate interactions between cells in biofilms. CdrA is a 220-kilodalton-sized multi-domain polypeptide (65) that protrudes 70 nm from the cell surface into the extracellular matrix (66). CdrA contains several MBG2-type repeat domains that allow it to extend from the outer membrane (67). CdrA is a two-partner secretion system adhesin that is anchored on the cell surface by its partner protein CdrB, which forms a β-barrel in the outer membrane (68). Being anchored in the CdrB pore at its C-terminus, the N-terminus of CdrA contains an adhesive tip that interacts with the mannose-rich, long-chain polysaccharide Psl (69, 70). This interaction is crucial for biofilm stability, as blocking it disassembles biofilms (66). In the same vein as P. aeruginosa CdrA, other bacteria use other polypeptide adhesins to mediate cell–cell interactions in biofilms, such as the Ag43 protein of Escherichia coli, which forms zipper-like dimers to tether opposing cells together, leading to the formation of cellular rosettes (71, 72).

Beyond the spatial access provided by the appendage’s extension module highlighted in the previous section, both the long-range multi-protein pili and the short-range polypeptide adhesins share additional common design principles (Fig. 1B). In particular, both CupE pili and CdrA adhesins are anchored at the surface of the bacterial cells through a defined molecular interaction at one of the ends of the appendage, which we refer to as an anchoring module. In the case of CupE pili, the pilus is anchored to the CupE5 usher, whereas in the case of CdrA, the C-terminus is held in the outer membrane barrel of CdrB using a cysteine hook (68). In Gram-positive bacteria likewise, both multi-protein pili and multi-domain adhesins have a sorting signal (typically a conserved LPXTG motif), which facilitates anchoring of the appendage into the cell wall via action of sortase enzymes (73, 74). Overall, an anchoring module is present in all bacterial surface appendages, making it an important characteristic architectural feature, even though the biochemical mechanisms of anchoring differ markedly from case to case (75, 76).

Non-self-interactions: binding in host infection

For pathogenic bacteria, the ability to colonize host tissue is often dependent on the ability to recognize and bind to host cell surface proteins (Fig. 1C). This is a crucial part of the establishment of infection, and the specificity of adhesion dictates tissue tropism and the colonization of a specific niche (77).

The FimA pilus of Porphyromonas gingivalis is a crucial virulence factor that facilitates both biofilm formation and host cell colonization, causing chronic periodontal disease (78). This distinctive type V (type 5) pilus is composed of many copies of the FimA subunit, creating a 0.3- to 1.6-µm-long filament (79). FimA subunits polymerize and extend through a protease-mediated strand exchange mechanism, where the action of Rgp proteases results in release of a β-strand to fill a hydrophobic groove of the neighboring subunit, generating the polymeric pilus (80, 81). This mechanism is distinct from the donor-strand complementation mechanism operating in the assembly of type 1 pilus subunits that results in a different pilus morphology (80, 82). In the case of the FimA pilus of P. gingivalis, the proximal FimA subunits are tethered to the cell by the FimB protein (83). The adhesive tip of the protein is formed by the distal FimA subunit with the accessory proteins FimC, FimD, and FimE (84, 85). The FimA pilus has been shown to bind diverse targets, including proline-rich salivary proteins, statherins, and host-cell-associated matrix proteins (86–91). These host-cell-associated proteins include keratin, integrin, collagen type I, fibronectin, laminin, and elastin (91–95). Furthermore, the tip accessory proteins have been shown to have an important role in binding, with deletion of FimCDE attenuating binding to fibronectin and type I collagen (96). A similar principle is observed in the Fim (type 1) pilus of uropathogenic E. coli where the distal FimH tip protein interacts with terminal α-D-linked mannose residues of N-linked glycans on urinary tract epithelial cells (97, 98). Other examples of adhesion include flagella in P. aeruginosa and C. difficile, which have been found to promote adherence to epithelial cells and human mucus during infection (99–102). Specifically, the flagellar cap protein (distal tip of the flagellum) has been implicated in mediating interactions with the target in both cases (101, 103).

Besides long pili such as FimA from P. gingivalis, single polypeptide adhesins can also support host colonization. A notable example is provided by the fibronectin-binding protein A (FnBPA), which is a crucial mediator of host colonization in Staphylococcus aureus (104, 105). FnBPA is anchored to the cell surface of S. aureus cells via a C-terminal LPXTG motif that links to 11 extended repeated regions that position the N-terminus away from the cell surface (73, 106). The N-terminal section of FnBPA consists of three immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) domains, which form a promiscuous ligand-interacting site that can attach to the structurally distinct eukaryotic extracellular matrix proteins fibrinogen, fibronectin, and elastin (107). At the molecular level, adhesion is mediated by a “dock, lock and latch mechanism.” This involves a fibrinogen peptide inserting into an open trench between two of the Ig-like domains, catalyzing a conformational rearrangement that locks the bound peptide in place (108, 109). This strong interaction can also take place in two different scenarios; either through interaction with fibronectin in the extracellular matrix or through fibronectin bound to integrin (110). In S. aureus cells lacking FnBPA, the ability to colonize host cells is reduced by approximately 500-fold (111, 112). In addition to host colonization, FnBPA has also been shown to be crucial in S. aureus biofilm formation, suggesting multiple functions of the same protein (113, 114).

Multi-protein host-binding pili like FimA and single polypeptide adhesins like FnBPA share all the molecular machine construction features mentioned above, including a cell-anchoring module at one of their ends, as well as multiple repeat domains that form the extension module, allowing the appendage to exit the immediate capsule of the bacterium. Another feature highlighted above is the presence of an adhesin at the distal end of the appendage, which we call an adhesion module. This module is positioned at the end away from the cell surface that engages with the target molecule. In FimA pili, this adhesion module consists of both the FimA subunit and the FimCDE accessory proteins, whereas in FnBPA, it is the fibronectin-binding N-terminal immunoglobulins.

COMMON FEATURES OF A PROTOTYPICAL FILAMENTOUS ADHESIVE APPENDAGE

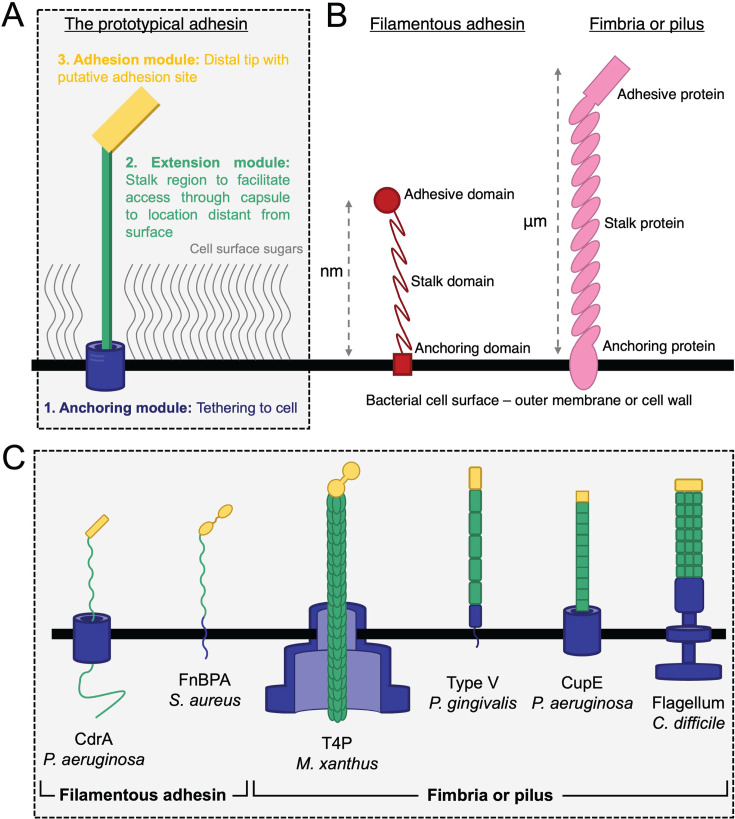

In all contexts of extracellular interactions, we have found common design features that are shared by filamentous microbial appendages. We have highlighted one of these design features in each of the sections above, and our enumeration of these characteristics allows us to define common features that must be shared by every filamentous appendage (Fig. 2A). In addition to the examples discussed in detail above, we provide further examples of filamentous appendages in Table 1, all of which exhibit the same architectural principles discussed in this review.

Fig 2.

Architectural dissection of microbial filamentous surface adhesive appendages. (A) The molecular architecture of a prototypical microbial cell surface adhesive appendage. We propose that all surface appendages must contain three modular parts; first, the presence of an anchoring module, which ensures that the appendage remains bound to the cell. Second, an extension module composed of repeated domains or polymeric proteins enables the appendage to extend away from the cell and out of the dense, sugary network at the cell surface. Third, at the distal end of the appendage, far away from the cell surface, an adhesion module mediates interactions with target molecules. (B) The comparison between a single polypeptide filamentous adhesin and a multi-protein pilus. Despite differences in length, biochemistry, and molecular details, the overall modular molecular architecture of every appendage is the same from a “molecular machines” perspective. We propose that all appendages (fibrillar polypeptides, pili or fimbriae, and even polysaccharides) must contain the three basic modules highlighted in panel A. (C) The overall molecular architecture of examples of a few filamentous appendages described in the text. The colors are the same as panel A to highlight the architectural modularity. Despite differences in molecular details, there is an underlying simplicity in the molecular architecture of filamentous surface adhesive appendages. Panel made using information from references (33, 57, 68, 80, 107, 115).

TABLE 1.

Further examples of filamentous surface adhesive appendages along with their architectural modules

| Name and type | Species | Anchoring module | Extension module | Adhesion module | Role(s) | References and further reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fim pilus (Type 1 – chaperone-usher pilus) |

Escherichia coli | FimD usher adds FimA units into a rod and anchors the rod in the outer membrane. | Made of up to ~3,000 copies of FimA in ~2-µm-long pili. Rod extends through donor-strand complementation between FimA subunits. |

Adhesive protein FimH is associated with FimG and FimF at the distal tip of the pilus. | Host cell binding to uroplakin 1a receptors (mannose moieties in N-linked glycans) in the urinary tract during infection. | (82, 97, 98, 116–120) |

| Thin aggregative fimbria (Tafi) (Nucleation-precipitation pilus) |

Salmonella enterica | AgfEFG proteins regulate fiber assembly and maintain the fidelity of fibers. | Fiber consists primarily of repeating units of AgfA (major fiber component) with a predicted β-strand rich structure typical of nucleation-precipitation pili. AgfB is a minor fiber component. |

Undefined adhesion module. | Associated with cellulose and other extracellular polymeric substances in biofilms. | (121–125) |

| Type IV pilus (Type IVa pilus) |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Type IV secretion platform, consisting of the proteins PilCFMNOPQ, anchors the pilus to the cell surface. The cytoplasmic ATPases PilT, PilB, and PilU govern the ATP-dependent pilus extension and retraction. |

Pilus made of multiple subunits of pilin PilA. T4P dynamically extends and retracts through polymerization and depolymerization of PilA. |

PilY1 protein mediates the adherence to abiotic surfaces at the distal tip. | Mediates interactions with surfaces in biofilm formation. | (22, 126–134) |

| Fine tangled pilus (Ftp) (tad pilus) |

Haemophilus ducreyi | Undefined anchoring module. | Composed predominantly of pilin subunit FtpA. | Not much known about the adhesive tip of FtpA. | Adherence to abiotic surfaces. Microcolony formation: interaction with self. |

(135–137) |

| Toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) (Type IVb pilus) |

Vibrio cholerae | TcpC forms a secretin ring in the outer membrane and is associated with TcpQ and TcpS. TcpDEJRT form the inner membrane-associated anchoring machinery. Incorporation of the minor pilin TcpB, rather than TcpA, at the inner membrane causes retraction of the pilus. |

Formed from repeating subunits of the pilin TcpA. | TcpB (minor pilin) forms a trimer at the pilus tip, creating the adhesion module. Association of TcpB and TcpF at the distal tip alters conformation allowing the pilus to leave the outer membrane through the TcpC secretin ring and extend. |

Microcolony formation: aids in colonization of the human intestine. | (138–141) |

| Tad pilus (Type IVc pilus) |

Caulobacter crescentus | Tad secretion system. Pilus retracts upon cell surface detection. |

Tad pilins (PilA) form the extension module. Unlike other type IV pilins, Tad pilins lack the characteristic β-sheet rich globular domains. |

Undefined adhesion module. | Abiotic surface adherence. Biofilm formation. |

(142, 143) |

| Pilus Islet 2 (PI-2) pilus (Sortase-dependent pilus) |

Streptococcus oralis | Unlike other Gram-positive pili, lack a basal pilin to link the pili to the cell wall. A housekeeping A-type sortase recognizes the PitB pilin for attachment to the cell wall. Molecular mechanism for anchoring and length control is not fully known. |

Many copies of the PitB pilin. | PitA pilin forms the distal tip of the pilus. | Coaggregation with Acinetobacter oralis in dental plaque (biofilm) formation. Interaction with galactose. |

(144–146) |

| Emp pilus (Sortase-dependent pilus) |

Enterococcus faecium | Assembled at the cell surface and integrated into the cell wall using a sortase. | Composed of the subunits EmpA, EmpB, and EmpC. EmpC is the major pilin. | EmpA localizes to the tip of the fiber where it plays a key role in regulating the length of the pilus. All three pilins shown to be important in the interaction with extracellular matrix proteins. EmpA and EmpB indispensable in mediating biofilm interactions. |

Biofilm formation. Host cell interactions in urinary tract infections: interactions with extracellular matrix proteins. |

(144, 147–150) |

| Hap (Monomeric autotransporter – type V secretion system) |

Haemophilus influenzae | Hap consists of three major domains: an N-terminal signal peptide, a passenger domain, and a C-terminal outer membrane translocator domain. The C-terminal domain is also an outer membrane β-barrel, which holds Hap at the cell surface. |

A section of 60 residues separates the outer membrane barrel from the passenger domain. The passenger domain is elongated, contributing to extension from the cell surface. | The passenger domain acts as the adhesion module. Within this domain, the extracellular-matrix binding region facilitates binding to matrix components. The SAAT region facilitates adherence to epithelial cells and self (Hap–Hap interactions). |

Binds to matrix components fibronectin, laminin, and collagen IV. Microcolony formation and biofilm formation via Hap–Hap interactions. |

(151–154) |

| LecB | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Associated with the membrane. | Homotetramer, which consists of four LecB monomers. | Contains a calcium-dependent carbohydrate-binding domain. | LecB binds to biofilm matrix sugars to stabilize the multicellular community. | (155, 156) |

| FrhA | Vibrio cholerae | Two-partner secretion system consisting of two proteins: FrhA and FrhC. FrhC is an outer membrane pore, which holds the FrhA adhesin. | Extension module is not well characterized. | FrhA is the adhesin molecule and contains a C-terminal peptide-binding domain. Also contains four cadherin repeats that help bind to epithelial cells and erythrocytes. |

Host cell binding. Biofilm formation. |

(157–159) |

| Ace | Enterococcus faecalis | Held at the surface of cells through the action of sortases to integrate its C-terminal LPXTG anchoring motif into the cell wall. | The B domain of Ace acts as the extension module and consists of a variable number of repeats (between 2 and 5 repeats of 47 amino acids). | Binding to collagen requires the A domain of Ace, which has two sub-domains with an Ig-like fold. Mechanism of binding is known as a “collagen hug” and is an adapted version of the dock-lock-latch mechanism employed by other MSCRAMMs. |

Interaction with host-cell- associated molecules. Adherence of cells to human collagen type IV and dentin (and rat collagen type I and mouse laminin). |

(160–163) |

| SdrG | Staphylococcus epidermis | SdrG is held at the cell wall with a proline-rich cell-wall-spanning domain, which also contains the characteristic LPXTG motif for tethering to the cell wall. | The R domain consists of serine and aspartate repeats to extend the ligand domain away from the cell surface. | The N-terminal “A” domain employs the canonical dock-lock-latch mechanism to bind to fibrinogen. | Fibrinogen binding–host cell interaction. | (108, 164–166) |

| Aap | Staphylococcus epidermis | C-terminal LPXTG motif binds to the cell wall. | Aap is a “periscope protein” with a variable number of repeats in the “B” domain. | “A” domain is a lectin-binding domain. | Binds to polystyrene. Interaction with corneocytes (host interaction). Biofilm formation. |

(167–169) |

| BabA | Helicobacter pylori | The second domain is predicted to form an outer membrane-spanning β-barrel for anchoring BabA. | Undefined extension module. | Extracellular adhesin domain consists of a β-sheet region that interacts with fucosylated blood group antigens. | Host cell binding to fucosylated blood group antigens on gastric mucosa, e.g., Lewisb antigen. | (170–173) |

| YadA (trimeric autotransporter adhesin – type V secretion system) |

Yersinia pestis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Yersinia enterocolitica | Each monomer consists of a β-barrel as the membrane-anchoring domain, forming a trimeric β-barrel together with two other subunits. | Each monomer has a coiled-coil stalk, which forms a trimeric coiled coil together and make the extension domain. | The ligand-binding domains of each of the polypeptides have a left-handed parallel β-roll fold and together form a compact domain. | Host cell binding: interaction with collagens, fibronectin, and laminins in the matrix. Autoagglutination. |

(174–177) |

| Filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) (Hemagglutinin-like adhesin – type V secretion system) |

Bordetella pertussis | Two-partner secretion system consisting of two proteins: FhaC and FHA. FHA N-terminus interacts with the FhaC pore to anchor at the cell surface. |

FhaB is the ~370 kDa precursor to the extended β-helical FHA that is cleaved upon exit from the FhaC pore. | The adhesive domain interacts with ligands on tracheal cells including complement receptor 3 and very late antigen V. | Host cell binding. | (178–182) |

First, every appendage must have an anchoring module: a part of the machinery dedicated to affixing the appendage at the cell surface to maintain connection with the underlying cell, as well as to facilitate the potential transfer of information from distal locations back to the bacterium. Second, all appendages contain an extension module: a part of machinery dedicated to stretching from the cell surface through a repeated stalk region. This is facilitated by structurally repeating domains in a single polypeptide adhesin or by many copies of the same protein in a multi-protein pilus or fimbria. Third, the distal tip of the appendage (located far away from the cell surface) must contain an adhesion module, which facilitates binding to a surface or to a ligand. All these features are found unanimously across all the surface appendage examples that we have discussed in this review, and we propose in others that we have not considered in detail (see also Table 1). These requirements usually dictate a certain modularity that must be built into bacterial surface appendages. The molecular architecture of each appendage must, therefore, simultaneously fulfil the multiple requirements of anchoring (to the cell surface), extension (from the cell surface), and adhesion (to a distant target). Irrespective of underlying molecular details, be it multi-protein pili or single polypeptide filamentous adhesins, and also irrespective of biological function, i.e., binding to abiotic surfaces, to other bacteria or to hosts, these requirements of anchoring, extension, and adhesion must be fulfilled, meaning that the governing molecular principles are the same in all appendages from a “molecular machines” viewpoint (Fig. 2B and C).

DIVERSITY OF ADHESION IN BACTERIA

Overall, we have discussed how different types of proteinaceous bacterial surface appendages play an important role in adhesion in numerous contexts. These adhesive appendages share the same overall modular architecture, as we have asserted in this article. Several examples further demonstrate a large degree of redundancy in the functional roles of different filamentous appendages. For example, a filamentous appendage could be involved both in biofilm formation and in binding to the host in infection (Table 1; Fig. 2). This observation of redundancy further supports the idea of underlying simplicity in the molecular architecture of surface appendages.

Both from a microbiological as well as therapeutic perspective, understanding bacterial adhesive appendages is of particular importance. Surface appendages can have a profound influence on the fundamental cell biology of bacterial cells, because the expression of these appendages can rapidly drive planktonic bacteria into biofilms and facilitate surface colonization (65). From a therapeutic standpoint, these appendages are often virulence factors and targets for the design of antimicrobials. For example, blocking of the P. aeruginosa CdrA has been shown to render biofilms susceptible to antibiotics (66). In the same manner, blocking of type 1 pili in uropathogenic E. coli has also been shown to decrease cell adhesion and biofilm formation (183).

We propose that these design principles could be extended to all surface appendages; for example, even non-proteinaceous appendages could be considered within the same molecular framework, possessing a modular architecture with specific design features (Fig. 2A). Let us consider the example of the dedicated molecular machinery for surface adhesion in Caulobacter crescentus called holdfast, which is an adhesive polysaccharide appendage. The holdfast polysaccharide is anchored just beneath the outer membrane through the HfaABD complex, whereas extension into the extracellular space as well as adhesion are carried out by polysaccharide components of the holdfast (184). Even this primarily non-proteinaceous adhesive appendage can be conceptually deconstructed into the three basic architectural modules. Inevitably of course, there are variations in the precise molecular details in each system; however, it is helpful to think of bacterial adhesion from this perspective to delineate common features.

In summary, there is an underlying shared molecular architecture in all bacterial filamentous appendages, which is not confined to appendages that share the same sequence or function. This underlying modular architecture is repeated in many examples of molecules that facilitate bacterial adherence to extracellular targets, highlighting the importance of environmental sensing and adhesion in bacteria. Interacting with distant targets is an important capability of any cell, beyond even bacteria, which is required for the cell to adapt to a rapidly changing environment. The usage of filamentous appendages containing three basic modules by cell surfaces represents a general modular solution to the universal problem of organizing molecular interactions outside the periphery of a cell, which we propose is pervasive across all (micro)organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Abul Tarafder and Jan Böhning for critical reading of the manuscript. T.A.M.B. would like to thank UKRI MRC (Programme MC_UP_1201/31), the Wellcome Trust (Grant 225317/Z/22/Z), the EPSRC (Grant EP/V026623/1), the European Molecular Biology Organization, the Leverhulme Trust, and the Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine for support.

For the purpose of open access, the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Biographies

Olivia E. R. Smith received her BSc in Biological Sciences from Imperial College London and an MRes in Structural Molecular Biology also from Imperial College London. Since 2022, she has been a PhD Student with the University of Cambridge at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Olivia is interested in understanding how pathogenic bacteria form biofilms, focusing on the atomic structure and function of cell surface biofilm-promoting proteins. Olivia is particularly interested in investigating how fundamental mechanisms of biofilm formation could be targeted to design therapeutics against bacterial infections.

Tanmay A. M. Bharat is a programme leader at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge (UK). Tanmay studied Chemistry at the University of Delhi and Biology at the University of Oxford. He completed his PhD at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany on Structural Biology, focusing on electron tomography of pathogens. After a post-doc in Cambridge, Tanmay started his laboratory at the Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford in 2017, studying how pathogenic bacteria form biofilms. Now, Tanmay’s laboratory is back in Cambridge (UK), developing structural and cell biology methods to characterise bacteria (particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa) biofilms at high-resolution.

Contributor Information

Tanmay A. M. Bharat, Email: tbharat@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk.

George O'Toole, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coutte L, Alonso S, Reveneau N, Willery E, Quatannens B, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F. 2003. Role of adhesin release for mucosal colonization by a bacterial pathogen. J Exp Med 197:735–742. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klemm P, Schembri MA. 2000. Bacterial adhesins: function and structure. Int J Med Microbiol 290:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80102-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soto GE, Hultgren SJ. 1999. Bacterial adhesins: common themes and variations in architecture and assembly. J Bacteriol 181:1059–1071. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.4.1059-1071.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiil K, Ferchaud JB, David C, Binnewies TT, Wu H, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Willenbrock H, Ussery DW. 2005. Genome update: distribution of two-component transduction systems in 250 bacterial genomes. Microbiol 151:3447–3452. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28423-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Di Martino P. 2018. Bacterial adherence: much more than a bond. AIMS Microbiol 4:563–566. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2018.3.563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berne C, Ducret A, Hardy GG, Brun YV. 2015. Adhesins involved in attachment to abiotic surfaces by Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Spectr 3. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0018-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O’Toole GA, Wong GC. 2016. Sensational biofilms: surface sensing in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 30:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berne C, Ellison CK, Ducret A, Brun YV. 2018. Bacterial adhesion at the single-cell level. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:616–627. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0057-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craig L, Pique ME, Tainer JA. 2004. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:363–378. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sangermani M, Hug I, Sauter N, Pfohl T, Jenal U. 2019. Tad pili play a dynamic role in Caulobacter crescentus surface colonization. MBio 10:e01237-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01237-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Serra DO, Conover MS, Arnal L, Sloan GP, Rodriguez ME, Yantorno OM, Deora R. 2011. FHA-mediated cell-substrate and cell-cell adhesions are critical for Bordetella pertussis biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and in the mouse nose and the trachea. PLoS One 6:e28811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoshida K, Toyofuku M, Obana N, Nomura N. 2017. Biofilm formation by Paracoccus denitrificans requires a type I secretion system-dependent adhesin BapA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx029. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garnett JA, Martínez-Santos VI, Saldaña Z, Pape T, Hawthorne W, Chan J, Simpson PJ, Cota E, Puente JL, Girón JA, Matthews S. 2012. Structural insights into the biogenesis and biofilm formation by the Escherichia coli common pilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3950–3955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106733109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martínez-Gil M, Yousef-Coronado F, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2010. LapF, the second largest Pseudomonas putida protein, contributes to plant root colonization and determines biofilm architecture. Mol Microbiol 77:549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ammendolia MG, Bertuccini L, Iosi F, Minelli F, Berlutti F, Valenti P, Superti F. 2010. Bovine lactoferrin interacts with cable pili of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Biometals 23:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9333-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lazar Adler NR, Dean RE, Saint RJ, Stevens MP, Prior JL, Atkins TP, Galyov EE. 2013. Identification of a predicted trimeric autotransporter adhesin required for biofilm formation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. PLoS One 8:e79461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen A, Seifert HS. 2011. Interactions with host cells causes Neisseria meningitidis pili to become unglued. Front Microbiol 2:66. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mandlik A, Swierczynski A, Das A, Ton-That H. 2007. Corynebacterium diphtheriae employs specific minor pilins to target human pharyngeal epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol 64:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05630.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwarz-Linek U, Werner JM, Pickford AR, Gurusiddappa S, Kim JH, Pilka ES, Briggs JAG, Gough TS, Höök M, Campbell ID, Potts JR. 2003. Pathogenic bacteria attach to human fibronectin through a tandem β-zipper. Nature 423:177–181. doi: 10.1038/nature01589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brotcke Zumsteg A, Goosmann C, Brinkmann V, Morona R, Zychlinsky A. 2014. IcsA is a Shigella flexneri adhesin regulated by the type III secretion system and required for pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 15:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Costa TRD, Patkowski JB, Macé K, Christie PJ, Waksman G. 2024. Structural and functional diversity of type IV secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 22:170–185. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00974-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Craig L, Forest KT, Maier B. 2019. Type IV pili: dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:429–440. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0195-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pelicic V. 2023. Mechanism of assembly of type 4 filaments: everything you always wanted to know (but were afraid to ask). Microbiol 169:001311. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berleman JE, Scott J, Chumley T, Kirby JR. 2008. Predataxis behavior in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:17127–17132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804387105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun H, Zusman DR, Shi W. 2000. Type IV pilus of Myxococcus xanthus is a motility apparatus controlled by the frz chemosensory system. Curr Biol 10:1143–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00705-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu SS, Wu J, Kaiser D. 1997. The Myxococcus xanthus pilT locus is required for social gliding motility although pili are still produced. Mol Microbiol 23:109–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1791550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merz AJ, So M, Sheetz MP. 2000. Pilus retraction powers bacterial twitching motility. Nature 407:98–102. doi: 10.1038/35024105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skerker JM, Berg HC. 2001. Direct observation of extension and retraction of type IV pili. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:6901–6904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121171698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bischof LF, Friedrich C, Harms A, Søgaard-Andersen L, van der Does C. 2016. The type IV pilus assembly ATPase PilB of Myxococcus xanthus interacts with the inner membrane platform protein PilC and the nucleotide-binding protein PilM. J Biol Chem 291:6946–6957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.701284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siewering K, Jain S, Friedrich C, Webber-Birungi MT, Semchonok DA, Binzen I, Wagner A, Huntley S, Kahnt J, Klingl A, Boekema EJ, Søgaard-Andersen L, van der Does C. 2014. Peptidoglycan-binding protein TsaP functions in surface assembly of type IV pili. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E953–E961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322889111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Treuner-Lange A, Chang Y-W, Glatter T, Herfurth M, Lindow S, Chreifi G, Jensen GJ, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2020. PilY1 and minor pilins form a complex priming the type IVa pilus in Myxococcus xanthus. Nat Commun 11:5054. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18803-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang Y-W, Rettberg LA, Treuner-Lange A, Iwasa J, Søgaard-Andersen L, Jensen GJ. 2016. Architecture of the type IVa pilus machine. Science 351:aad2001. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Treuner-Lange A, Zheng W, Viljoen A, Lindow S, Herfurth M, Dufrêne YF, Søgaard-Andersen L, Egelman EH. 2024. Tight-packing of large pilin subunits provides distinct structural and mechanical properties for the Myxococcus xanthus type IVa pilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121:e2321989121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2321989121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jakovljevic V, Leonardy S, Hoppert M, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2008. PilB and PilT are ATPases acting antagonistically in type IV pilus function in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 190:2411–2421. doi: 10.1128/JB.01793-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eriksson J, Eriksson OS, Maudsdotter L, Palm O, Engman J, Sarkissian T, Aro H, Wallin M, Jonsson A-B. 2015. Characterization of motility and piliation in pathogenic Neisseria. BMC Microbiol 15:92. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0424-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kearns DB, Robinson J, Shimkets LJ. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits directed twitching motility up phosphatidylethanolamine gradients. J Bacteriol 183:763–767. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.763-767.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Merz AJ, So M. 2000. Interactions of pathogenic Neisseriae with epithelial cell membranes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16:423–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ronish LA, Sidner B, Yu Y, Piepenbrink KH. 2022. Recognition of extracellular DNA by type IV pili promotes biofilm formation by Clostridioides difficile. J Biol Chem 298:102449. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hinsa SM, Espinosa-Urgel M, Ramos JL, O’Toole GA. 2003. Transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 requires an ABC transporter and a large secreted protein. Mol Microbiol 49:905–918. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA, Brinkman FSL. 2016. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D646–D653. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Boyd CD, Smith TJ, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Newell PD, Dufrêne YF, O’Toole GA. 2014. Structural features of the Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm adhesin LapA required for LapG-dependent cleavage, biofilm formation, and cell surface localization. J Bacteriol 196:2775–2788. doi: 10.1128/JB.01629-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boyd CD, Chatterjee D, Sondermann H, O’Toole GA. 2012. LapG, required for modulating biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1, is a calcium-dependent protease. J Bacteriol 194:4406–4414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00642-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chatterjee D, Cooley RB, Boyd CD, Mehl RA, O’Toole GA, Sondermann H. 2014. Mechanistic insight into the conserved allosteric regulation of periplasmic proteolysis by the signaling molecule cyclic-di-GMP. Elife 3:e03650. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Navarro MVAS, Newell PD, Krasteva PV, Chatterjee D, Madden DR, O’Toole GA, Sondermann H. 2011. Structural basis for c-di-GMP-mediated inside-out signaling controlling periplasmic proteolysis. PLoS Biol 9:e1000588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Newell PD, Boyd CD, Sondermann H, O’Toole GA. 2011. A c-di-GMP effector system controls cell adhesion by inside-out signaling and surface protein cleavage. PLoS Biol 9:e1000587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Puhm M, Hendrikson J, Kivisaar M, Teras R. 2022. Pseudomonas putida biofilm depends on the vWFa-domain of LapA in peptides-containing growth medium. Int J Mol Sci 23:5898. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ivanov IE, Boyd CD, Newell PD, Schwartz ME, Turnbull L, Johnson MS, Whitchurch CB, O’Toole GA, Camesano TA. 2012. Atomic force and super-resolution microscopy support a role for LapA as a cell-surface biofilm adhesin of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Res Microbiol 163:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guo S, Stevens CA, Vance TDR, Olijve LLC, Graham LA, Campbell RL, Yazdi SR, Escobedo C, Bar-Dolev M, Yashunsky V, Braslavsky I, Langelaan DN, Smith SP, Allingham JS, Voets IK, Davies PL. 2017. Structure of a 1.5-MDa adhesin that binds its Antarctic bacterium to diatoms and ice. Sci Adv 3:e1701440. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flemming H-C, Wuertz S. 2019. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:247–260. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0158-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Böhning J, Tarafder AK, Bharat TAM. 2024. The role of filamentous matrix molecules in shaping the architecture and emergent properties of bacterial biofilms. Biochem J 481:245–263. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Booth SC, Smith WPJ, Foster KR. 2023. The evolution of short- and long-range weapons for bacterial competition. Nat Ecol Evol 7:2080–2091. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02234-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol 49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nuccio S-P, Bäumler AJ. 2007. Evolution of the chaperone/usher assembly pathway: fimbrial classification goes Greek. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:551–575. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Bentzmann S, Giraud C, Bernard CS, Calderon V, Ewald F, Plésiat P, Nguyen C, Grunwald D, Attree I, Jeannot K, Fauvarque M-O, Bordi C. 2012. Unique biofilm signature, drug susceptibility and decreased virulence in Drosophila through the Pseudomonas aeruginosa two-component system PprAB. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003052. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Giraud C, Bernard CS, Calderon V, Yang L, Filloux A, Molin S, Fichant G, Bordi C, de Bentzmann S. 2011. The PprA-PprB two-component system activates CupE, the first non-archetypal Pseudomonas aeruginosa chaperone-usher pathway system assembling fimbriae. Environ Microbiol 13:666–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Böhning J, Dobbelstein AW, Sulkowski N, Eilers K, von Kügelgen A, Tarafder AK, Peak-Chew S-Y, Skehel M, Alva V, Filloux A, Bharat TAM. 2023. Architecture of the biofilm-associated archaic Chaperone-Usher pilus CupE from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 19:e1011177. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ahmad I, Nadeem A, Mushtaq F, Zlatkov N, Shahzad M, Zavialov AV, Wai SN, Uhlin BE. 2023. Csu pili dependent biofilm formation and virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9:101. doi: 10.1038/s41522-023-00465-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Balch WE, Kelly JW. 2007. Functional amyloid--from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem Sci 32:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kikuchi T, Mizunoe Y, Takade A, Naito S, Yoshida S. 2005. Curli fibers are required for development of biofilm architecture in Escherichia coli K-12 and enhance bacterial adherence to human uroepithelial cells. Microbiol Immunol 49:875–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Luna-Pineda VM, Moreno-Fierros L, Cázares-Domínguez V, Ilhuicatzi-Alvarado D, Ochoa SA, Cruz-Córdova A, Valencia-Mayoral P, Rodríguez-Leviz A, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J. 2019. Curli of uropathogenic Escherichia coli enhance urinary tract colonization as a fitness factor. Front Microbiol 10:2063. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Evans ML, Chapman MR. 2014. Curli biogenesis: order out of disorder. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1551–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Böhning J, Ghrayeb M, Pedebos C, Abbas DK, Khalid S, Chai L, Bharat TAM. 2022. Donor-strand exchange drives assembly of the TasA scaffold in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Nat Commun 13:7082. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34700-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Böhning J, Graham M, Letham SC, Davis LK, Schulze U, Stansfeld PJ, Corey RA, Pearce P, Tarafder AK, Bharat TAM. 2023. Biophysical basis of filamentous phage tactoid-mediated antibiotic tolerance in P. aeruginosa. Nat Commun 14:8429. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44160-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Borlee BR, Goldman AD, Murakami K, Samudrala R, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol 75:827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06991.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Melia CE, Bolla JR, Katharios-Lanwermeyer S, Mihaylov DB, Hoffmann PC, Huo J, Wozny MR, Elfari LM, Böhning J, Morgan AN, Hitchman CJ, Owens RJ, Robinson CV, O’Toole GA, Bharat TAM. 2021. Architecture of cell-cell junctions in situ reveals a mechanism for bacterial biofilm inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118:e2109940118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2109940118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Monzon V, Lafita A, Bateman A. 2021. Discovery of fibrillar adhesins across bacterial species. BMC Genomics 22:550. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07586-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cooley RB, Smith TJ, Leung W, Tierney V, Borlee BR, O’Toole GA, Sondermann H. 2016. Cyclic di-GMP-regulated periplasmic proteolysis of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type Vb secretion system substrate. J Bacteriol 198:66–76. doi: 10.1128/JB.00369-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Reichhardt C, Wong C, Passos da Silva D, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2018. CdrA interactions within the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix safeguard it from proteolysis and promote cellular packing. MBio 9:e01376-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01376-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reichhardt C, Jacobs HM, Matwichuk M, Wong C, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2020. The versatile Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix protein CdrA promotes aggregation through different extracellular exopolysaccharide interactions. J Bacteriol 202:e00216-20. doi: 10.1128/JB.00216-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Heras B, Totsika M, Peters KM, Paxman JJ, Gee CL, Jarrott RJ, Perugini MA, Whitten AE, Schembri MA. 2014. The antigen 43 structure reveals a molecular Velcro-like mechanism of autotransporter-mediated bacterial clumping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:457–462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311592111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Puri D, Allison KR. 2024. Escherichia coli self-organizes developmental rosettes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121:e2315850121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2315850121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fischetti VA, Pancholi V, Schneewind O. 1990. Conservation of a hexapeptide sequence in the anchor region of surface proteins from Gram-positive cocci. Mol Microbiol 4:1603–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02072.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marraffini LA, Dedent AC, Schneewind O. 2006. Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:192–221. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.192-221.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bhat AH, Nguyen MT, Das A, Ton-That H. 2021. Anchoring surface proteins to the bacterial cell wall by sortase enzymes: how it started and what we know now. Curr Opin Microbiol 60:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hospenthal MK, Costa TRD, Waksman G. 2017. A comprehensive guide to pilus biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:365–379. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Thanassi DG. 2011. The long and the short of bacterial adhesion regulation. J Bacteriol 193:327–328. doi: 10.1128/JB.01345-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hasegawa Y, Nagano K. 2021. Porphyromonas gingivalis FimA and Mfa1 fimbriae: current insights on localization, function, biogenesis, and genotype. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 57:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2021.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Xu Q, Shoji M, Shibata S, Naito M, Sato K, Elsliger M-A, Grant JC, Axelrod HL, Chiu H-J, Farr CL, Jaroszewski L, Knuth MW, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Curtis MA, Nakayama K, Wilson IA. 2016. A distinct type of pilus from the human microbiome. Cell 165:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shibata S, Shoji M, Okada K, Matsunami H, Matthews MM, Imada K, Nakayama K, Wolf M. 2020. Structure of polymerized type V pilin reveals assembly mechanism involving protease-mediated strand exchange. Nat Microbiol 5:830–837. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0705-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shoji M, Shibata S, Sueyoshi T, Naito M, Nakayama K. 2020. Biogenesis of type V pili. Microbiol Immunol 64:643–656. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Remaut H, Rose RJ, Hannan TJ, Hultgren SJ, Radford SE, Ashcroft AE, Waksman G. 2006. Donor-strand exchange in chaperone-assisted pilus assembly proceeds through a concerted β strand displacement mechanism. Mol Cell 22:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nagano K, Hasegawa Y, Murakami Y, Nishiyama S, Yoshimura F. 2010. FimB regulates FimA fimbriation in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Dent Res 89:903–908. doi: 10.1177/0022034510370089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Enersen M, Nakano K, Amano A. 2013. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. J Oral Microbiol 5. doi: 10.3402/jom.v5i0.20265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pierce DL, Nishiyama S, Liang S, Wang M, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K, Yoshimura F, Demuth DR, Hajishengallis G. 2009. Host adhesive activities and virulence of novel fimbrial proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun 77:3294–3301. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00262-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Amano A, Sharma A, Lee JY, Sojar HT, Raj PA, Genco RJ. 1996. Structural domains of Porphyromonas gingivalis recombinant fimbrillin that mediate binding to salivary proline-rich protein and statherin. Infect Immun 64:1631–1637. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1631-1637.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Amano A, Shizukuishi S, Horie H, Kimura S, Morisaki I, Hamada S. 1998. Binding of Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae to proline-rich glycoproteins in parotid saliva via a domain shared by major salivary components. Infect Immun 66:2072–2077. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.5.2072-2077.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kataoka K, Amano A, Kuboniwa M, Horie H, Nagata H, Shizukuishi S. 1997. Active sites of salivary proline-rich protein for binding to Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. Infect Immun 65:3159–3164. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3159-3164.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kataoka K, Amano A, Kawabata S, Nagata H, Hamada S, Shizukuishi S. 1999. Secretion of functional salivary peptide by Streptococcus gordonii which inhibits fimbria-mediated adhesion of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun 67:3780–3785. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.8.3780-3785.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Nagata H, Sharma A, Sojar HT, Amano A, Levine MJ, Genco RJ. 1997. Role of the carboxyl-terminal region of Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbrillin in binding to salivary proteins. Infect Immun 65:422–427. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.422-427.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhang W, Ju J, Rigney T, Tribble G. 2013. Integrin α5β1-fimbriae binding and actin rearrangement are essential for Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of osteoblasts and subsequent activation of the JNK pathway. BMC Microbiol 13:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Murakami Y, Hanazawa S, Tanaka S, Iwahashi H, Kitano S, Fujisawa S. 1998. Fibronectin in saliva inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbria-induced expression of inflammatory cytokine gene in mouse macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 22:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Nakagawa I, Amano A, Inaba H, Kawai S, Hamada S. 2005. Inhibitory effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae on interactions between extracellular matrix proteins and cellular integrins. Microbes Infect 7:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nakamura T, Amano A, Nakagawa I, Hamada S. 1999. Specific interactions between Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae and human extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 175:267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sojar HT, Sharma A, Genco RJ. 2002. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae bind to cytokeratin of epithelial cells. Infect Immun 70:96–101. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.96-101.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nishiyama S, Murakami Y, Nagata H, Shizukuishi S, Kawagishi I, Yoshimura F. 2007. Involvement of minor components associated with the FimA fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis in adhesive functions. Microbiol 153:1916–1925. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/005561-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sauer MM, Jakob RP, Eras J, Baday S, Eriş D, Navarra G, Bernèche S, Ernst B, Maier T, Glockshuber R. 2016. Catch-bond mechanism of the bacterial adhesin FimH. Nat Commun 7:10738. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhou G, Mo WJ, Sebbel P, Min G, Neubert TA, Glockshuber R, Wu XR, Sun TT, Kong XP. 2001. Uroplakin Ia is the urothelial receptor for uropathogenic Escherichia coli: evidence from in vitro FimH binding. J Cell Sci 114:4095–4103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.4095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Simpson DA, Ramphal R, Lory S. 1992. Genetic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence: distinct genetic loci control attachment to epithelial cells and mucins. Infect Immun 60:3771–3779. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3771-3779.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Simpson DA, Ramphal R, Lory S. 1995. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fliO, a gene involved in flagellar biosynthesis and adherence. Infect Immun 63:2950–2957. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2950-2957.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Tasteyre A, Barc MC, Collignon A, Boureau H, Karjalainen T. 2001. Role of FliC and FliD flagellar proteins of Clostridium difficile in adherence and gut colonization. Infect Immun 69:7937–7940. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7937-7940.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Haiko J, Westerlund-Wikström B. 2013. The role of the bacterial flagellum in adhesion and virulence. Biology (Basel) 2:1242–1267. doi: 10.3390/biology2041242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Arora SK, Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. 1998. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar cap protein, FliD, is responsible for mucin adhesion. Infect Immun 66:1000–1007. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.3.1000-1007.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Jönsson K, Signäs C, Müller HP, Lindberg M. 1991. Two different genes encode fibronectin binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. The complete nucleotide sequence and characterization of the second gene. Eur J Biochem 202:1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Patti JM, Jonsson H, Guss B, Switalski LM, Wiberg K, Lindberg M, Höök M. 1992. Molecular characterization and expression of a gene encoding a Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin. J Biol Chem 267:4766–4772. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42898-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Tsompanidou E, Denham EL, Sibbald M, Yang X-M, Seinen J, Friedrich AW, Buist G, van Dijl JM. 2012. The sortase A substrates FnbpA, FnbpB, ClfA and ClfB antagonize colony spreading of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 7:e44646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Bingham RJ, Rudiño-Piñera E, Meenan NAG, Schwarz-Linek U, Turkenburg JP, Höök M, Garman EF, Potts JR. 2008. Crystal structures of fibronectin-binding sites from Staphylococcus aureus FnBPA in complex with fibronectin domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:12254–12258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803556105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ponnuraj K, Bowden MG, Davis S, Gurusiddappa S, Moore D, Choe D, Xu Y, Hook M, Narayana SVL. 2003. A “dock, lock, and latch” structural model for a staphylococcal adhesin binding to fibrinogen. Cell 115:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00809-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Speziale P, Pietrocola G. 2020. The multivalent role of fibronectin-binding proteins A and B (FnBPA and FnBPB) of Staphylococcus aureus in host infections. Front Microbiol 11:2054. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sinha B, François PP, Nüsse O, Foti M, Hartford OM, Vaudaux P, Foster TJ, Lew DP, Herrmann M, Krause KH. 1999. Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin α5β1. Cell Microbiol 1:101–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Dziewanowska K, Patti JM, Deobald CF, Bayles KW, Trumble WR, Bohach GA. 1999. Fibronectin binding protein and host cell tyrosine kinase are required for internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by epithelial cells. Infect Immun 67:4673–4678. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.9.4673-4678.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Fowler T, Wann ER, Joh D, Johansson S, Foster TJ, Höök M. 2000. Cellular invasion by Staphylococcus aureus involves a fibronectin bridge between the bacterial fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs and host cell beta1 integrins. Eur J Cell Biol 79:672–679. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Geoghegan JA, Monk IR, O’Gara JP, Foster TJ. 2013. Subdomains N2N3 of fibronectin binding protein A mediate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and adherence to fibrinogen using distinct mechanisms. J Bacteriol 195:2675–2683. doi: 10.1128/JB.02128-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. O’Neill E, Pozzi C, Houston P, Humphreys H, Robinson DA, Loughman A, Foster TJ, O’Gara JP. 2008. A novel Staphylococcus aureus biofilm phenotype mediated by the fibronectin-binding proteins, FnBPA and FnBPB. J Bacteriol 190:3835–3850. doi: 10.1128/JB.00167-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Stevenson E, Minton NP, Kuehne SA. 2015. The role of flagella in Clostridium difficile pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol 23:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ronald A. 2002. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens. Am J Med 113 Suppl 1A:14S–19S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01055-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Hahn E, Wild P, Hermanns U, Sebbel P, Glockshuber R, Häner M, Taschner N, Burkhard P, Aebi U, Müller SA. 2002. Exploring the 3D molecular architecture of Escherichia coli type 1 pili. J Mol Biol 323:845–857. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Waksman G, Hultgren SJ. 2009. Structural biology of the chaperone–usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:765–774. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Phan G, Remaut H, Wang T, Allen WJ, Pirker KF, Lebedev A, Henderson NS, Geibel S, Volkan E, Yan J, Kunze MBA, Pinkner JS, Ford B, Kay CWM, Li H, Hultgren SJ, Thanassi DG, Waksman G. 2011. Crystal structure of the FimD usher bound to its cognate FimC-FimH substrate. Nature 474:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nature10109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Zyla DS, Wiegand T, Bachmann P, Zdanowicz R, Giese C, Meier BH, Waksman G, Hospenthal MK, Glockshuber R. 2024. The assembly platform FimD is required to obtain the most stable quaternary structure of type 1 pili. Nat Commun 15:3032. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47212-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Collinson SK, Parker JMR, Hodges RS, Kay WW. 1999. Structural predictions of AgfA, the insoluble fimbrial subunit of Salmonella thin aggregative fimbriae. J Mol Biol 290:741–756. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. White AP, Collinson SK, Banser PA, Gibson DL, Paetzel M, Strynadka NCJ, Kay WW. 2001. Structure and characterization of AgfB from Salmonella enteritidis thin aggregative fimbriae. J Mol Biol 311:735–749. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Ledeboer NA, Frye JG, McClelland M, Jones BD. 2006. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium requires the Lpf, Pef, and Tafi fimbriae for biofilm formation on HEp-2 tissue culture cells and chicken intestinal epithelium. Infect Immun 74:3156–3169. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01428-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Quan G, Xia P, Zhao J, Zhu C, Meng X, Yang Y, Wang Y, Tian Y, Ding X, Zhu G. 2019. Fimbriae and related receptors for Salmonella Enteritidis. Microb Pathog 126:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. White AP, Gibson DL, Collinson SK, Banser PA, Kay WW. 2003. Extracellular polysaccharides associated with thin aggregative fimbriae of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. J Bacteriol 185:5398–5407. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5398-5407.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Burrows LL. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility: type IV pili in action. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:493–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Tammam S, Sampaleanu LM, Koo J, Manoharan K, Daubaras M, Burrows LL, Howell PL. 2013. PilMNOPQ from the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus system form a transenvelope protein interaction network that interacts with PilA. J Bacteriol 195:2126–2135. doi: 10.1128/JB.00032-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Chi E, Mehl T, Nunn D, Lory S. 1991. Interaction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with A549 pneumocyte cells. Infect Immun 59:822–828. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.822-828.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Ochner H, Böhning J, Wang Z, Tarafder AK, Caspy I, Bharat TAM. 2024. Structure of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 type IV pilus. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.09.588664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 130. Thongchol J, Yu Z, Harb L, Lin Y, Koch M, Theodore M, Narsaria U, Shaevitz J, Gitai Z, Wu Y, Zhang J, Zeng L. 2024. Removal of Pseudomonas type IV pili by a small RNA virus. Science 384:eadl0635. doi: 10.1126/science.adl0635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Marko VA, Kilmury SLN, MacNeil LT, Burrows LL. 2018. Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV minor pilins and PilY1 regulate virulence by modulating FimS-AlgR activity. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007074. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Webster SS, Mathelié-Guinlet M, Verissimo AF, Schultz D, Viljoen A, Lee CK, Schmidt WC, Wong GCL, Dufrêne YF, O’Toole GA. 2021. Force-induced changes of PilY1 drive surface sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 13:e0375421. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03754-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Adams DW, Pereira JM, Stoudmann C, Stutzmann S, Blokesch M. 2019. The type IV pilus protein PilU functions as a PilT-dependent retraction ATPase. PLoS Genet 15:e1008393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. 1994. Characterization of a gene, pilU, required for twitching motility but not phage sensitivity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 13:1079–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Spinola SM, Fortney KR, Katz BP, Latimer JL, Mock JR, Vakevainen M, Hansen EJ. 2003. Haemophilus ducreyi requires an intact flp gene cluster for virulence in humans. Infect Immun 71:7178–7182. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7178-7182.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Nika JR, Latimer JL, Ward CK, Blick RJ, Wagner NJ, Cope LD, Mahairas GG, Munson RS Jr, Hansen EJ. 2002. Haemophilus ducreyi requires the flp gene cluster for microcolony formation in vitro. Infect Immun 70:2965–2975. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2965-2975.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Al-Tawfiq JA, Bauer ME, Fortney KR, Katz BP, Hood AF, Ketterer M, Apicella MA, Spinola SM. 2000. A pilus-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is virulent in the human model of experimental infection. J Infect Dis 181:1176–1179. doi: 10.1086/315310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Li J, Lim MS, Li S, Brock M, Pique ME, Woods VL, Craig L. 2008. Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus structure analyzed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Structure 16:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Oki H, Kawahara K, Iimori M, Imoto Y, Nishiumi H, Maruno T, Uchiyama S, Muroga Y, Yoshida A, Yoshida T, Ohkubo T, Matsuda S, Iida T, Nakamura S. 2022. Structural basis for the toxin-coregulated pilus-dependent secretion of Vibrio cholerae colonization factor. Sci Adv 8:eabo3013. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Nguyen M, Wu T-H, Danielson KJ, Khan NM, Zhang JZ, Craig L. 2023. Mechanism of secretion of TcpF by the Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120:e2212664120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2212664120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Chang Y-W, Kjær A, Ortega DR, Kovacikova G, Sutherland JA, Rettberg LA, Taylor RK, Jensen GJ. 2017. Architecture of the Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus machine revealed by electron cryotomography. Nat Microbiol 2:16269. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Wang Y, Theodore M, Xing Z, Narsaria U, Yu Z, Zeng L, Zhang J. 2024. Structural mechanisms of Tad pilus assembly and its interaction with an RNA virus. Sci Adv 10:eadl4450. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adl4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Mignolet J, Panis G, Viollier PH. 2018. More than a Tad: spatiotemporal control of Caulobacter pili. Curr Opin Microbiol 42:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Yadav RK, Krishnan V. 2022. New structural insights into the PI-2 pilus from Streptococcus oralis, an early dental plaque colonizer. FEBS J 289:6342–6366. doi: 10.1111/febs.16527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Kumari Yadav R, Krishnan V. 2020. The adhesive PitA pilus protein from the early dental plaque colonizer Streptococcus oralis: expression, purification, crystallization and X-ray diffraction analysis. Acta Cryst F Struct Biol Commun 76:8–13. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X1901642X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Zähner D, Gandhi AR, Yi H, Stephens DS. 2011. Mitis group streptococci express variable pilus islet 2 pili. PLoS One 6:e25124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Montealegre MC, Singh KV, Somarajan SR, Yadav P, Chang C, Spencer R, Sillanpää J, Ton-That H, Murray BE. 2016. Role of the emp pilus subunits of Enterococcus faecium in biofilm formation, adherence to host extracellular matrix components, and experimental infection. Infect Immun 84:1491–1500. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01396-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Sillanpää J, Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Prakash VP, Fothergill T, Ton-That H, Murray BE. 2010. Characterization of the ebpfm pilus-encoding operon of Enterococcus faecium and its role in biofilm formation and virulence in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Virulence 1:236–246. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.4.11966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Garsin DA, Hook M, Erlandsen SL, Murray BE. 2006. Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili of Enterococcus faecalis. J Clin Invest 116:2799–2807. doi: 10.1172/JCI29021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Almohamad S, Somarajan SR, Singh KV, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE. 2014. Influence of isolate origin and presence of various genes on biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecium. FEMS Microbiol Lett 353:151–156. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]