Abstract

The amino acid sequence plays an essential role in amyloid for-mation. Here, using the central core recognition module of the Aβ peptide and its reverse sequence, we show that although both peptides assemble into β-sheets, their morphologies, kinetics and cell toxicities display marked differences. In addition, the native peptide, but not the reverse one, shows notable affinity towards bilayer lipid model membranes that modulates the aggregation pathways to stabilize the oligomeric intermediate states and function as the toxic agent responsible for neuronal dysfunction.

There is an intense effort to elucidate the mechanism formation of amyloid structures by proteins and peptides, motivated by its relevance to understanding the misfolded structures, believed to cause diseases including Alzheimer’s.1 The formation of fibrillar and oligomeric states of the Amyloid β (Aβ) peptide is implicated in the progression of this condition. The substantial research activity on Aβ has led to identification of a core aggregation domain which encompasses the Aβ(16-22) Ac-KLVFFAE-NH2 sequence.1,2 This peptide has been shown to form fibrils or nanotubes, depending on the solution conditions.3 The core domain includes the FF sequence, which is believed to drive aggregation due to aromatic stacking interactions.4 The analogous peptide NH2-AAKLVFF-OH was also found to form fibrils and nanotubes in different conditions.5

The oligomerization propensity of Aβ-driven peptides is known to be related to their interaction with lipid bilayers.1d,6 Lipid membranes may (partially) unfold the peptide, increase the local concentration of membrane-bound peptide molecules, and facilitate aggregation by aligning the peptide. In addition, lipid rafts are implicated in Aβ dimer and oligomer formation and may provide platforms for selective deposition of different Aβ-aggregates.

In the field of amyloid assembly, the influence of the sequence order has rarely been systematically examined.7 Reverse full Aβ peptides Aβ(42-1) and Aβ(40-1) are sometimes used as negative controls in AD-related animal cytotoxicity studies and in Aβ production assays.7 Similarly, the reverse Aβ(35-25) peptide is used as a control in studies using Aβ(25-35).7,8 The retro-inverse Aβ peptide ffvlk (D-amino acids) has been shown to bind Aβ40 fibrils with moderate affinity, but this binding can be significantly enhanced by attaching multiple copies of this peptide to an eight-arm branched PEG.9 In a recent study on a different amyloid peptide, the aggregation of a transthyretin fragment conjugated to RGD was compared to that of the reverse peptide, and both were found to form similar fibrillar assemblies.10 Serpell and coworkers have recently studied the self-assembly of the full length Aβ1-42 and its reverse sequence.7a Although both the peptides found to self-assemble into fiber structures, the reverse sequence has reduced effect on cellular health.

Here, for the first time, we compare the conformation and aggregation of Aβ(16-22), the core recognition motif of Aβ and the reverse peptide Aβ(22-16). In addition, the cytotoxicity of the two peptides towards model neuronal cell line is investigated. Significant differences in the self-assembly kinetics and neural toxicity are observed. We further study the interactions of both pseudo-zwitterionic peptides with a model zwitterionic lipid mixture. The native peptide shows strong affinity towards lipid vesicles, resulting in stabilization of the oligomeric state by modulation of the aggregation kinetics thereby leading to toxicity. However, the reverse peptide has minimal affinity for the bilayer lipid vesicles as it self-assembles very quickly into mature fibers, which in turn are non-toxic to cells.

We first investigated the morphology of self-assembled nanostructures fabricated by the two peptides at neutral pH (~7) after aging for two weeks. Fig. 1a–f shows transmission electron micrograph (TEM) and atomic force micrograph (AFM) images of the peptides. Amyloid-like straight, unbranched fibers 10-15 nm in diameter and length reaching to several microns were observed for both peptides. The CD spectra of both peptides showed typical peaks of a β-sheet secondary structure. The spectrum for the native peptide contained negative maxima at 217 nm with a positive peak at 202 nm (Fig. 1g). For the reverse peptide, the negative maxima was observed at 218 nm, with a positive peak at 198 nm (Fig. 1h). Thus, both the peptides self-assembled to produce a β-sheet structure, with the peaks slightly red shifted as compared to canonical β-sheet probably due to strong π–π stacking interactions. The high conformational flexibility of the peptide backbone was evaluated by temperature dependent denaturation experiments (Fig. S1 and S2, ESI†). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to further confirm the preferred secondary structure. The native peptide showed a vibrational band at 1627 cm−1 in the amide I region, in correlation with a β-sheet conformation (Fig. 1i). The reverse peptide showed a peak at 1628 cm−1 with a shoulder at 1664 cm−1, also indicating the predominate presence of a β-sheet structure (Fig. 1j).

Fig. 1. (a) TEM and (b and c) AFM images of Aβ(16-22). (d) TEM and (e and f) AFM images of Aβ(22-16). (g and h) CD spectra for Aβ(16-22) (g) and Aβ(22-16) (h). (i and j) FTIR spectra for the native peptide (i) and its reverse sequence (j).

To evaluate the details of the peptide molecular packing in the self-assembled fibers, small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was carried out. The SAXS intensity profiles (Fig. S3, ESI†) showed an initial q−2 slope for both samples, consistent with flattened nanotape-like fibrils. Correspondingly, the data was fitted to a suitable form factor used for peptide nanotape fibrils.11 The results showed a clear differences between the molecular arrangement of the two peptides. The polydispersity in fibril diameter was much higher for Aβ(16-22) in comparison to Aβ(22-16), and for the later a form factor maximum allowed an estimation of nanotape thickness, (42.0 ± 9.7) Å, corresponding to approximately one bilayer based on the expected length of a β-sheet heptapeptide (7 × 3.2 Å = 22 Å). The fibril dimensions are in agreement with the TEM and AFM imaging (Fig. 1).

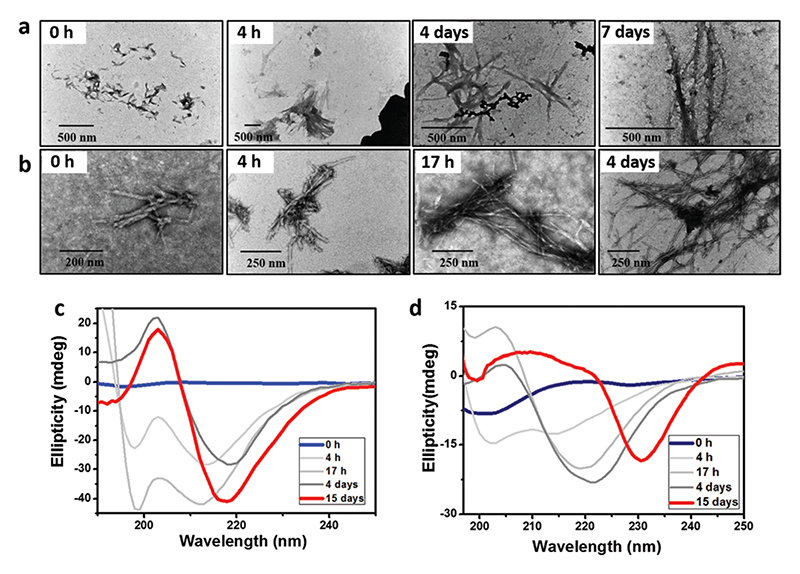

The kinetics of fiber formation was monitored by TEM imaging.12 Starting from small nucleation sites at 4 h, the native peptide transformed into mature fibers through intermediate aggregation steps over a time period of four to seven days (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the reverse sequence showed structure formation at a much faster rate (Fig. 2b). Ordered structures were observed after 17 h, and the self-assembly process was complete within four days. Thus, the intermediate aggregation rate of oligomers was significantly faster for the reverse peptide. The assembly process was further studied by following the CD spectra over time. Initially, the native peptide showed a negative peak near 200 nm, resembling a random coil conformation. Time-induced structural conversion from random coil into β-sheet ellipticity was identified after 4 days (Fig. 2c). The molar ellipticity became stronger over time and plateaus after 10 days. The time-dependent conformational transition from random coil to β-sheet is similar to that of other previously studied Aβ-derived peptides.13 The reverse peptide also elicited a similar structural transition, but with a different kinetics. Under similar conditions, the reverse peptide transformed from random coil into characteristic β-sheet ellipticity in 1 day (Fig. 2d). Over time, the peaks red shifted due to either strong aggregation through π–π stacking interaction of the aromatic residue or twisting of the β-sheet conformation during fiber formation.5b The kinetics of β-sheet formation by the two peptides, as shown by CD, was consistent with the morphological transition observed in the TEM images. However, it is extremely difficult to explain the different aggregation rates of the two peptides, as the molecular events involved in the aggregation process of oligomers still remain poorly defined. Also, the higher negative ζ-potential values for the reverse peptide, compared to the native peptide (Fig. 3a), indicated different surface charges and electrostatic repulsion between the molecules for the two peptides in the selfassembled state.

Fig. 2. (a and b) Kinetics of fiber formation as observed by TEM for Aβ(16-22) (a) and Aβ(22-16) (b). (c and d) CD spectra showing the transition from unstructured conformation into β-sheet over time for Aβ(16-22) (c) and Aβ(22-16) (d).

Fig. 3.

(a) ζ-potential of the two peptides. (b) MTT cell viability assay. (c–f) Cryo-TEM of Aβ(16-22) (c and d) and Aβ(22-16) (e and f) in the presence of lipid vesicles. Insets show negatively stained images of the peptides only. (g) Kinetics of peptide fibrillation using ThT fluorescence. (h) CD spectroscopy secondary structure analysis of Aβ(16-22) and Aβ(22-16) with and without lipid vesicles. In (g and h): blue and red spectra represent Aβ(16-22) and Aβ(22-16), respectively. Broken line represents peptide only and continuous line represents peptide with lipid vesicles. Scale bar for (c–f) is 200 nm.

To explore whether these fibrillation processes play a role in the cytotoxicity of the corresponding peptides, similar to amyloid aggregates, we performed a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell viability assay using the SH-SY5Y neuronal cell line. In the presence of the native peptide, cell viability decreased to approximately 70% within a short period of time (6 h), indicating substantial cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 3b). However, under similar experimental conditions, the reverse peptide showed no effect on the cells akin to the control experiment. A similar toxicity profile for the two peptides was also observed for another cell line, namely PC12 (Fig. S4, ESI†). The differences in the toxicity are probably due to the intermediate oligomers formed by the native peptide during the fibrillization pathway, leading to toxicity. The mechanism of amyloidogenic protein/peptide aggregation typically involves a conformational switch, with oligomer formation leading to protofibrils and finally mature fibrils. Although the mature fibers were initially believed to be responsible for disease pathogenesis, recent evidence suggests oligomeric intermediates are the most toxic species.14 Our kinetic study evidently showed that the rate of self-assembly and mature fiber formation of the native peptide was slow. Throughout the MTT assay, most peptide molecules were in an intermediate oligomeric state, thus leading to cell toxicity. However, the reverse peptide self-assembled at a much faster rate and most of the peptide molecules transformed into mature fibers during the experimental time scale, thus resulting in no significant cell toxicity. We also examined the stability of the two peptides in the presence of human serum.15 The results indicate both peptides to be quite stable as no degradation was observed up to 72 h in the presence of proteolytic enzymes (Fig. S5 and S6, ESI†).

We studied the membrane interactions of the peptides to explore the mechanism of toxicity.1d For this, we used vesicles mimicking mammalian plasma membranes comprising 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), cholesterol, and sphingomyelin (DOPC/Chol/Sph). Fig. 3c–f shows the fundamental differences in membrane interactions of the two peptides. Although both peptides fibrillized in either the presence or the absence of lipid bilayers, Aβ(16-22) showed intimate interactions with lipid bilayers. As shown in Fig. 3c and d, the vesicles and fibrils of Aβ(16-22) were bound, and no free vesicles are found. In contrast, for Aβ(22-16), only a small amount of lipid vesicles adhered to the fibrillar structures (Fig. 3e, f and Fig. S7, ESI†). This difference in the interactions is probably due to the slightly different surface potential originating from the assembly state and structure which induced different organization of the charged residues on the oligomer/fibril surface.

To elucidate the influence of lipid bilayer on peptide assembly, the kinetics of fibrillation was studied using Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay (Fig. 3g). Generally, ThT fluorescence increases in the presence of amyloidal fibrillar structures.16 Likewise, increase in ThT fluorescence during a kinetic measurement indicates a process of fibril elongation.17 The reverse peptide did not display any fluorescence increase during 96 hours (only the first 20 hours are shown). This may be due to fast fibrillation and sedimentation of the aggregates. Nevertheless, the particular surface potential may also induce ThT adherence to the fibril surface without flattening the ThT probe to its fluorescent conformation. Moreover, the addition of lipid vesicles did not result in any change in ThT fluorescence. In contrast, Aβ(16-22) showed a dramatic increase in fluorescence (dotted blue curve). This increase in florescence intensity is related to typical amyloid fibril elongation. Surprisingly, the addition of lipid vesicles resulted in inhibition of the fibrillation process, as exemplified by the reduction of fluorescence in the presence of lipid vesicles, as compared to their absence. The lowered maximal fluorescence indicates that addition of lipid vesicles resulted in inhibition of the fibril elongation step, rather than inhibition of early stages of aggregation from monomer to oligomer.

To evaluate the impact of the lipid membranes on peptide conformation, CD spectra were recorded (Fig. 3h). The reverse peptide showed a spectrum with a minimum around 197 nm, correlated to a random coil structure. The presence of lipid vesicles resulted in a CD spectrum with minimum at 220 nm. However, the signal was extremely weak, possibly due to very low solubility of the peptide assemblies. The significant phase separation between peptide nanostructures and lipid vesicles was also identified in cryo-TEM images. In contrast, the random coil conformation of the native peptide without lipid vesicles (broken blue line in Fig. 3h) changed dramatically in the presence of lipids, with the strong maximum at ~ 205 nm indicating the formation of a β-sheet like structural pattern with exposed Phe sidechains.18 Thus, the formation of β-sheet structure by the native peptide is not affected by the presence of lipid vesicles, in contrast to the reverse peptide.

It has been shown that the effects of lipids on amyloid aggregation are diverse, among which modulating of aggregation pathways is the most significant.19 The charged membranes act as two-dimensional aggregation-templates to initiate the soluble random coil monomeric peptides to aggregate into β-sheet oligomers at a faster rate for native peptide. However, ThT kinetics suggests that the fibril elongation from the oligomeric state is inhibited in the presence of lipid bilayers. The heterotypic aggregation (peptide–lipid) follows an off-fibril formation pathway instead of homotypic (peptide–peptide) on-pathway. “Off-pathway” oligomers tend to have a longer halflife and are slow in converting into mature fibrils due to their potential stabilization in kinetic traps. Thus, the presence of lipid vesicles significantly alters the aggregation pathways for the native peptide and induces oligomer-stabilizing conditions, which in turn causes amyloid cytotoxicity.

In conclusion, our work sheds light on the observation that although the high toxicity of the Aβ(1-42) peptide leads to neuronal dysfunction, the reverse sequence Aβ(42-1) is non-toxic, which has been assumed to be due to its inability to form ordered fibers. Using a core recognition motif of Aβ, here we demonstrate that although both peptide sequences aggregate to form fibrillar structures, they display markedly different aggregation kinetics. Moreover, the native peptide, not the reverse, shows strong cellular cytotoxicity. A membrane binding study reveals that the native peptide shows a strong affinity to lipid vesicles, resulting in stabilization of the oligomeric state. In contrast, the reverse peptide forms mature fibers at a much faster rate and is phase separated from the lipid vesicles. It has minimal affinity for the bilayer lipid vesicles and therefore does not show any toxicity. This study provides a firm foundation for the understanding of the influence of amino acid sequence order on amyloid assembly and function, which may pave the way to in-depth understanding of the amyloid formation process.

This project received funding from ERC (grant agreement No BISON-694426 to E. G.). I. W. H. thanks EPSRC (UK) for the award of a Platform grant (EP/L020599/1).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.(a) Teplow DB. Amyloid. 1998;5:121. doi: 10.3109/13506129808995290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Selkoe DJ. Nat Med. 2011;17:1060. doi: 10.1038/nm.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chiti F, Dobson CM. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hamley IW. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5147. doi: 10.1021/cr3000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wei G, Su ZQ, Reynolds NP, Arosio P, Hamley IW, Gazit E, Mezzenga R. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:4661. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00542j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Hilbich C, Kisterswoike B, Reed J, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:460. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tao K, Wang J, Zhou P, Wang C, Xu H, Zhao X, Lu JR. Langmuir. 2011;27:2723. doi: 10.1021/la1034273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Mehta AK, Lu K, Childers WS, Liang S, Dong J, Snyder JP, Pingali SV, Thiyagarajan P, Lynn DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9829. doi: 10.1021/ja801511n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lu K, Jacob J, Thiyagarajan P, Conticello VP, Lynn DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6391. doi: 10.1021/ja0341642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Gazit E. FASEB J. 2002;16:77. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0442hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gazit E. FEBS J. 2005;272:5971. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Castelletto V, Hamley IW, Harris PJF. Biophys Chem. 2008;138:29. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hamley IW, Nutt DR, Brown GD, Miravet JF, Escuder B, Rodríguez-Llansola F. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:940. doi: 10.1021/jp906107p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Butterfield SM, Lashuel HA. Angew Chem. 2010;49:5628. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsuzaki K. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2007;1768:1935. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Vadukul DM, Gbajumo O, Marshall KE, Serpell LC. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:822. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Emre M, Geula C, Ransil BJ, Mesulam MM. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:553. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ripoli C, Cocco S, Li Puma DD, Piacentini R, Mastrodonato A, Scala F, Puzzo D, D’Ascenzo M, Grassi C. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12893–12903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1201-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Paik SR, Lee JH, Kim DH, Chang CS, Kim YS. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bergin DH, Jing Y, Zhang H, Liu P. Neuroscience. 2015;298:367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor M, Moore S, Mayes J, Parkin E, Beeg M, Canovi M, Gobbi M, Mann DMA, Allsop D. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3261. doi: 10.1021/bi100144m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu LL, Zheng YF, Xu J, Qu FY, Lin YC, Zou YM, Yang YL, Gras SL, Wang C. Nano Res. 2018;11:577. doi: 10.1007/s12274-018-2094-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castelletto V, Hamley IW. In: Peptide Self-Assembly: Methods and Protocols. Nilsson BL, Doran TM, editors. Vol. 1777. Humana Press Inc; Totowa: 2018. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh M-C, Liang C, Mehta AK, Lynn DG, Grover MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:17007. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Simmons LK, May PC, Tomaselli KJ, Rydel RE, Fuson KS, Brigham EF, Wright S, Lieberburg I, Becker GW, Brems DN, Li WY. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;45:373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Soto C, Castaño EM. Biochem J. 1996;314:701. doi: 10.1042/bj3140701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Nature. 2002;416:507. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dobson CM. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:329. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul A, Kalita S, Kalita S, Sukumar P, Mandal B. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40095. doi: 10.1038/srep40095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeVine H., III Protein Sci. 1993;2:404. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles TPJ, Waudby CA, Devlin GL, Cohen SIA, Aguzzi A, Vendruscolo M, Terentjev EM, Welland ME, Dobson CM. Science. 2009;326:1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1178250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krysmann MJ, Castelletto V, Hamley IW. Soft Matter. 2007;3:1401. doi: 10.1039/b709889h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangachari V, Dean DN, Rana P, Vaidya A, Ghosh P. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2018;1860:1652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.