Abstract

Sexual health has provided a guiding framework for addressing sexuality in public health for several decades. Although the WHO definition of sexual health is revolutionary in acknowledging positive sexuality, public health approaches remain focused on risk and adverse outcomes. The long-standing conflation of sexual health and sexual wellbeing has affected our ability to address everyday sexual issues. This Viewpoint provides a way forward to resolve this impasse. We propose sexual wellbeing as a distinct and revolutionary concept that can be operationalised as a seven-domain model. We situate sexual wellbeing alongside sexual health, sexual justice, and sexual pleasure as one of four pillars of public health enquiry. We argue that sexual wellbeing is imperative to public health as a marker of health equity, a meaningful population indicator of wellbeing, a means to capture population trends distinct from sexual health, and an opportunity to refocus the ethics, form, and practices of public health.

Introduction

The widely-adopted definition of sexual health developed by WHO is expansive. It includes concepts such as the absence of disease and coercion, and draws attention to sexual rights and to the possibility of sexual pleasure.1 Yet, wellbeing is mentioned as an adjunctive element of sexual health; the unique elements of wellbeing— distinct from sexual health—are not identified.

The WHO definition of sexual health reduces stigma by helping researchers, educators, clinicians, and policy makers acknowledge positive sexuality and sexual experiences as key public health outcomes. However, public health approaches to sexuality remain rooted firmly in the medical and biological sectors, with their focus largely on adverse health outcomes and concomitant risks. This risk-focused approach has come to be viewed as the standard for public health, eclipsing other aspects of sexuality, even though health is seldom—if ever—the primary reason for engaging sex.2 Such a public health vision overlooks a contemporary body of evidence from scientific research supporting perspectives far broader than those associated with sexual health.3 In practice, perspectives on what constitutes normal sexuality are understood through a public health lens.4 In research, confusion and inconsistency across different studies, often in reference to the same issues, make it difficult to advance the science in this area. Most importantly, the conflation of sexual wellbeing and sexual health obscures the diversity of experiences—not clearly addressed in definitions of sexual health—that people identify as relevant to their broader wellbeing. This truncated perspective ultimately limits our ability to understand and address everyday sexual issues.

The absence of a sharp distinction between sexual wellbeing and sexual health has created ambiguity in policy rhetoric, and hindered conceptualisation of sexual wellbeing as a valid outcome of public health interventions. For more than a decade, advocates and thought leaders have acknowledged the need to expand the scope of inquiry and intervention in public health from a singular focus on sexual health to attention on sexual wellbeing as a distinct concept. The call to make this shift partly emerged from a WHO–UN Population Fund meeting in 2007. At that time there was considerable difficulty agreeing on the meaning of sexual wellbeing. Since then, efforts to adopt sexual wellbeing as part of a comprehensive, holistic, and progressive goal for public health have stalled indefinitely, awaiting additional justification, articulation, and operationalisation.

This Viewpoint constitutes a long overdue effort to effectively resolve this impasse. We build on increasing awareness of the limits and constraints of a sole focus on sexual health, and an emerging body of research on the relevance of sexuality to wellbeing. This emerging interest mirrors the greater attention given to population wellbeing of late. A more nuanced, multi-dimensional framework is required.

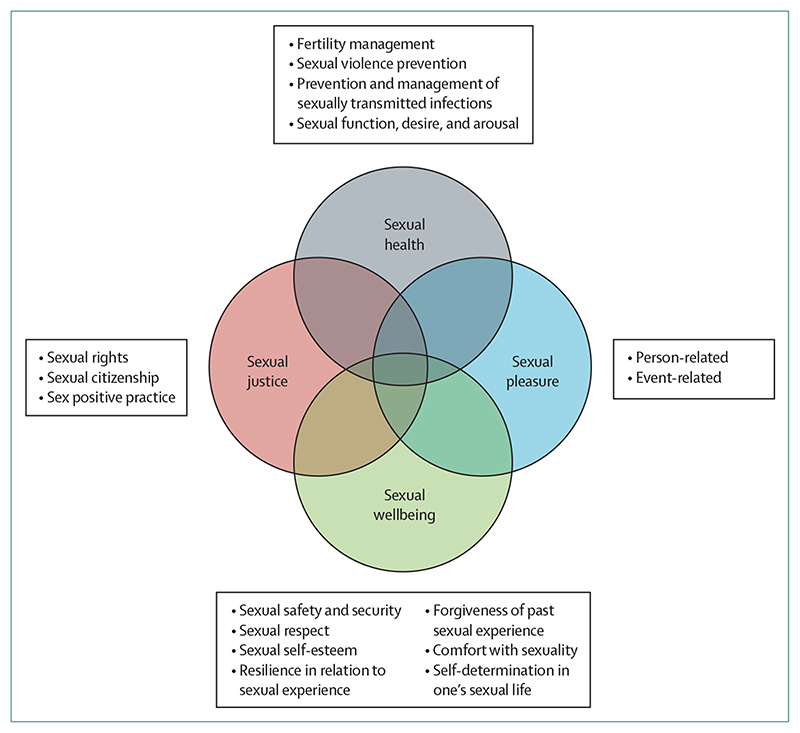

Our conceptualisation of sexual wellbeing resonates with the biopsychosocial–cultural framework based in people’s perspectives on sexual wellbeing in mid and later life.5 This perspective locates sexual wellbeing firmly in relation to sexual health, and in relation to two other pillars of public health focused inquiry—sexual pleasure and sexual justice—each needed to address structural determinants of sexual inequities (figure). Here, we describe the interconnections of these four pillars and the conceptual overlap with sexual wellbeing.

Figure. Four pillars of comprehensive public health focused inquiry and intervention in relation to sexuality.

A guiding premise of our argument is that the concept of sexual wellbeing demands recognition, not as an extension, subclass, or alternate form of sexual health, but as a distinct and revolutionary concept that challenges our accepted thinking, and has far-reaching global applications in public health that have been neglected to date. However, our interest in expanding recognition of the public health relevance of sexual wellbeing does not undermine the importance of sexual health, sexual pleasure, and sexual rights. Rather, we believe sexual wellbeing brings conceptual clarity to our shared understanding of sexual health, identifies areas of conceptual difference, and clarifies a much broader public health perspective on sexuality beyond sexual health alone.

Four pillars for a comprehensive public health approach to sexuality

Sexual health

Our model follows key issues identified in the WHO definition of sexual health: fertility regulation, prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs; including HIV), sexual violence prevention, and sexual functions (including sexual desire and arousal).6 The relevance of these issues to global public health were underlined by the 2018 Guttmacher–Lancet Commission on sexual and reproductive health and rights focusing on the role of the Sustainable Development Goals in promoting specific areas of sexual health.7 The WHO Working Group to Operationalize Sexual Health8 explicitly linked these aspects of sexual health to “physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to sexuality”, centred within an interconnected framework of sexual health influences, including attention to human rights and positive approaches to sexuality.

Sexual pleasure

Sexual pleasure is related to both sexual health and sexual wellbeing but its distinct relevance to public health is increasingly recognised.9,10 A recent definition of sexual pleasure addresses the diverse physical and psychological satisfactions of sexual experience, and key enabling factors, such as self-determination, consent, safety, privacy, confidence, and the ability to communicate and negotiate sexual relations.11 Furthermore, this definition specifies that pleasure requires fundamental social and cultural conditions of sexual rights in terms of equality, non-discrimination, autonomy, bodily integrity, and freedom of expression. To improve the operationalisation of sexual pleasure, we propose the inclusion of two key elements (figure): events (eg, key features of a sexual occasion, such as the repertoire, timing, and spacing of different sexual practices, occurrence of orgasm, use of a condom or contraception) and people (eg, interactional elements of sexual pleasure, encompassing interpersonal dynamics, such as communication, negotiation, and trust). These elements illustrate the conceptual relationships of pleasure with sexual health and sexual wellbeing, and help to summarise the diverse factors associated with sexual pleasure without privileging pleasure as the cornerstone of wellbeing.12,13

Sexual justice

Sexual justice represents larger global efforts to ensure social, cultural, and legal supports for equitable, person-centred sexual and reproductive experiences. Public health plays an instrumental role in documentation and mitigation of adverse outcomes associated with disparities in human rights. Public health also contributes to the promotion of equal access to distributive and restorative justice, helping combat historical restrictions of sexual citizenship on the basis of ethnicity, sex, and sexual and gender identity.7,14 Among many specific examples, public health has played a central role in addressing violence and discrimination linked to sexuality among people living with HIV.15 With regard to the pillar of sexual justice, we propose trauma-informed, sex positive public health practices as a specific tool for enacting social justice. This practice implies restorative approaches that acknowledge and address adverse sexual experiences, trauma that resonates through the life course, and the effects on sexual wellbeing.16,17 Sex positivity is central to a public health relevant concept of sexual wellbeing. Trauma-informed, sex positive practices refer to perspectives and approaches that emphasise contributions of sexuality and sexual expression to overall wellbeing.

Sexual wellbeing in the context of sexual health, sexual pleasure, and sexual justice

We believe it is now imperative for the field of public health to adopt and integrate sexual wellbeing in efforts to address pervasive inequities related to sexuality and sexual behaviour, in particular, those driven by gender and sexual identity. Our framework allows distinct attention to the role of sexual wellbeing in overall wellbeing18 and better support for operationalisation, measurement, and potential public health intervention.

Operationalisation and measurement of sexual wellbeing is challenged by diverse perspectives on its definition and meaning. Outside of professional spheres, people rarely refer to sexual wellbeing per se, although the concept is inferred in the idea of a sex life that is supposedly good or going well. Pharmacies sometimes sell products, such as vaginal tightening gel, nutritional supplements, and fertility aids, under the banner of sexual wellbeing. This commodification probably influences public understanding and focuses attention on a narrow set of assessment criteria to judge whether a sex life is going well.19 However, definitions of sexual wellbeing in academic literature attend to a broader range of aspects. Several measures have been developed, which inlclude unidimensional measures defined in terms of a global assessment of one’s sex life.20 Laumann and colleagues defined sexual wellbeing as “the cognitive and emotional evaluation of an individual’s sexuality”, and used four satisfaction judgments.21 Muise and colleagues used a similar definition, but extended the domains to include satisfaction with sexual relationships and functioning, sexual awareness, sexual self-esteem, and body image esteem.22 Syme and colleagues, in a study of sexuality in mid and later life, referred to sexual wellness with four dimensions: psychological (eg, cognitions, emotions, and concepts), social (eg, relationship and shared experience), biological and behavioural (eg, functioning, behaviours and scripted sexual activities), and cultural (eg, age or time in life, and gender and sexual orientation).5

In operationalising sexual wellbeing, we developed a model with seven core domains: sexual safety and security, sexual respect, sexual self-esteem, resilience in relation to past sexual experiences, forgiveness of past sexual events, self-determination in one’s sex life, and comfort with one’s sexuality (table). Domains were identified and refined through intensive engagement with wide-ranging literature, including a review of sexual wellbeing definitions and measures.62 In developing this new concept of sexual wellbeing, we specified five criteria: (1) the concept should be distinct from sexual health, sexual satisfaction, sexual pleasure, and sexual function; (2) the concept should be applicable to people regardless of whether they are sexually active; (3) the concept should apply to people irrespective of their partnership status (including those who are unpartnered); (4) the concept should be based in elements amenable to change through policy, public health action, clinical support, or personal growth; and (5) the concept should focus both on a person’s summation of experience and assessment of prospects for sexual wellbeing in the near future. For each of the seven domains, we provide a working definition and show its contribution to sexual wellbeing, provide examples of relevance to public health, and offer examples of how the domain might be operationalised (table).

Table. Sexual domains of sexual wellbeing: definitions, contributions, relevance to public health, and potential operationalised measures.

| Definition | Contribution to sexual wellbeing | Relevance to public health (examples) | Potential operationalised measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual safety and security5,23 | Experience of reduced threat coupled with experience of actions taken to assuage vulnerability24 | Free expression of sexuality;25,26 rituals of safety;27 relationship trust;28 coercion-free environments29 | Gender-based violence;30 technologies for partner identification;31 sexual coercion;28,32 legal protections for sexual rights;33,34 teaching sexual consent; addressing risks to sex workers | Little worry about future sex life; absence of unwanted vulnerability during sexual activities; feeling safe with a sexual partner |

| Sexual respect5 | Perception of positive regard by others for one’s sexual personhood35 | Mitigates influence of experiences of violence;36 tolerance of differences;37 validation by others38,39 | Elements of interventions to reduce sexual harassment (eg, in higher education39); sexual rights of people with minority identities and or marginalised experiences (eg, sexual minority groups living with HIV40) | Sexual identity and preferences accepted by those around you; sexual identity and preferences accepted by broader culture |

| Sexual selfesteem5,22 | Affective appraisals of oneself as a sexual being41 | Associated with sexual satisfaction;42 mindful attention to sexual interactions43 | Interventions to improve overall sexual functioning;44 building capacities to sexually relate to a partner22 | Feeling good about your body sexually; feeling in control of sexual thoughts and desires |

| Resilience in relation to sexual experiences | Maintenance of equilibrium in response to sexual stress, dysfunctions-adversity- or trauma45 | Influences long-term trajectories of wellbeing;46 interplay of person’s resources, needs, and assets3 | Lessens the effects of sexual minority stressors;47 support for recovery from emotional trauma | Having someone to talk to openly about your sex life; taking a long time to recover if something bad happens in your sex life |

| Forgiveness of past sexual experiences | Halted patterns of self-blame, self-stigmatisation, shame, avoidance, aggression, regret, and revenge48,49 | Reduces harm and improves wellbeing;50 improves relationship quality;51 mitigates trauma of laws, policies, and practices that harm or do not prevent harm52 | Interventions to support recovery from sexual trauma and improve subsequent health outcomes50,53 | Forgiveness of yourself about mistakes made in past sex life; forgiveness of others about things they have done to you in past sex life |

| Self-determination in one’s sex life5 | Free choice or rejection of sexual partner(s), behaviours, context and timing without pressure, force, or felt obligation54 | Directly influences sexual wellbeing;55 autonomous choice about sexuality supports ability to orient choices toward others56 | Global public health significance of unwanted sexual interactions;7 reproductive self-determination for women | Only doing sexual activities that you really want to do; not feeling pressure from others to do specific sexual activities |

| Comfort with sexuality5 | Experience of ease in contemplation, communication, and enactments of sexuality and sex57 | Exploration of sexual identities and experiences;58 associated with partner communication, trust, and forgiveness;59 mindfulness in attending to sexual contexts43,60 | Comfort in sexual communication associated with improved sexual health behaviours such as contraceptive use;61 ease in discussing sexual anatomy with a health professional; alleviating sexual guilt | Feeling focused and experiencing a sense of flow during sexual activities; absence of unwanted thoughts during sexual activities; absence of shame about sexual thoughts and desires; feeling comfortable with your sexual identity and preferences; a pleasurable sex life |

Why is sexual wellbeing imperative to public health?

We anticipate some resistance to considering wellbeing as a valid goal of public health. Critics refer to the subjective and variable qualities of wellbeing, necessarily influenced by social and cultural contexts, and played out in individual attitudes and actions.63 Introduction of surveillance infrastructures and goals in diverse national and cultural settings will require persistence and careful data gathering. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic and the life-changing interruptions of migration have changed sexual priorities such that even delimiting appropriate sexual wellbeing timeframes is challenging.64,65 There might be resource constraints to monitoring that requires a multi-dimensional measure, and political resistance to giving prominence to sexual wellbeing alongside risk-focused outcomes. Acknowledging these issues, we set out four ways in which sexual wellbeing is highly relevant to core functions of contemporary public health.

Sexual wellbeing is a marker of health equity

Within the field of public health, population wellbeing approaches seek to establish measurable and achievable goals toward equity.66 Sexual wellbeing is an appropriate marker of population wellbeing, given inequities related to sexuality and sexual expression. These inequities include systemic and pervasive racial, ethnic, or immigrationbased discrimination, gender-based violence, sexual identity-based violence, and STIs and HIV.7 A sexual wellbeing approach recognises the transgenerational traumas that mark the unique needs of marginalised people. This recognition then supports implementation of population health approaches that are anti-oppressive, intersectional, and culturally and contextually adapted.67,68

Sexual wellbeing is a meaningful population indicator of wellbeing

As population wellbeing continues to be an aspirational goal of public health, sexual wellbeing emerges as an important component of overall wellbeing. A populationbased study has shown the positive contribution of a measure of sexual wellbeing in population surveys.18 Sexual wellbeing provides important insights into population wellbeing over the entire life course. Data on sexual wellbeing would add new dimensions to community engagement in health issues, address structural determinants of health at local levels, and link local and larger public health policy and practice related to sexual and reproductive health.69

Sexual wellbeing captures population trends distinct from sexual health measures

Sexual wellbeing incorporates outcomes that are increasingly recognised as important to, but distinct from, biomedically focused sexual health intervention. In a review of English-language sexual health promotion interventions published from 2010–14, four of 33 interventions’ stated goals were related to sexual wellbeing; most interventions (n=28) either targeted sexual wellbeing in addition to biomedical sexual health, or addressed sexual health outcomes through a focus on sexual wellbeing.70 Tracking sexual wellbeing also shows key population trends in the importance of sex to broader wellbeing. For example, in four decades of French national surveys (1970s to 2006), the proportion of people reporting that sexual intercourse was considered essential to feeling good about oneself increased from 48% to 60% for women and from 55% to 69% for men.71

Sexual wellbeing refocuses the ethics, form, and practices of public health

Positioning sexual wellbeing as a driver for cross-cutting public health innovation challenges the structural origins of sexual inequities and requires acknowledging that sexual wellbeing is experienced by people in relation to contexts and surroundings.72 This suggests that surveillance of sexual wellbeing, at individual and community levels, is required, and thus challenges the centrality of privacy in sexuality. Public health surveillance is well established in sexual health prevention and control (eg, for STIs). However, extension to sexual wellbeing refocuses such surveillance—and the capacity to offer intervention—into areas traditionally outside of public health function. We contend that such surveillance is necessary to focus resources on populations of greatest need, and to track those who enter or exit intervals of greater need.73 Such functions might require redefinition of relationships between communities and public health entities to create trust and full engagement while protecting privacy.74

Conclusion

We believe that the adoption and integration of sexual wellbeing as an essential concept in efforts to address sexual inequities is imperative for the field of public health. A broad and consistent body of research supports the relevance of sexual wellbeing as a distinct correlate of sexual health whose importance has been obscured by conflation of the two concepts.75 Our conceptualisation of sexual wellbeing relates to sexual health and pleasure (a primary motivation for sex), and to social, cultural, and political frameworks of sexual justice. By identifying trauma-informed sex positivity as a central guiding public health value, we anchor our approach to sexual wellbeing with a corresponding recognition of the notable significance of both sexuality and sexual trauma in our lives. Inclusion of sexual wellbeing as a public health goal is attainable but requires an additional data-driven vision and specified objectives. Our initial steps toward an approach, and ultimately conceptualisation, of sexual wellbeing builds on existing measures and intentionally focuses on dimensions and an organisational structure that might be addressed effectively by public health policy and intervention.

The personal losses of illness and death, the threats to the health of families, the interpersonal effects of quarantine and physical distancing, and the pervasive economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic will almost certainly have enduring effects on sexual wellbeing that have yet to be fully described and appreciated. Significant public health resources will be needed, simply to meet the basic needs of many people. Our proposed shift in thinking about sexuality in public health will facilitate movement forward in the process of reorganising social structures to meet these effects, including attention to population wellbeing.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

Our initial search terms focused on “sexual wellbeing” using multiple databases, including Google Scholar, Psychinfo, and Ovid. No specific inclusion criteria were used other than relevance to emerging concepts. On the basis of this extensive process, we produced an initial set of sexual wellbeing domains summarised in the table. Additional literature reviews were based on key words “sexual safety,” “sexual security,” “sexual respect,” “sexual self-esteem,” “sexual resilience,” “sexual forgiveness,” “sexual self-determination,” and “sexual comfort.” No date limits were used in these reviews. Abstracts of retrieved articles were reviewed for relevance, with detailed review of selected papers, books, and book chapters. Additional resources were identified by hand searching the citation lists of relevant sources.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Fourth British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes (Natsal-4). The Natsal Resource is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (212931/Z/18/Z), with contributions from the Economic and Social Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research. KRM and RL are supported by core funding from the UK Medical Research Council [MC_UU_00022/3] and Scotland Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU18). The funders had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

JDF reviewed the literature with contributions from KRM, LFO’S, and RL. All authors contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Prof Lucia F O’Sullivan, Psychology Department, University of New Brunswick, NB, Canada.

Prof J Dennis Fortenberry, Indiana School of Medicine, Indiana University, IN, USA.

References

- 1.WHO. Defining Sexual Health. [accessed Aug 15, 2020]. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/

- 2.Epstein S, Mamo L. The proliferation of sexual health: diverse social problems and the legitimation of sexuality. Soc Sci Med. 2017;188:176–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellings K, Johnson AM. Framing sexual health research: adopting a broader perspective. Lancet. 2013;382:1759–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandfort TGM, Ehrhardt AA. Sexual health: a useful public health paradigm or a moral imperative? Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:181–87. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026618.16408.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syme ML, Cohn TJ, Stoffregen S, Kaempfe H, Schippers D. “At my age … ”: defining sexual wellness in mid- and later life. J Sex Res. 2019;56:832–42. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1456510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wellings K. In: Sexual health: a public health perspective. Wellings K, Mitchell K, Collumbien M, editors. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2012. Sexual health: theoretical perspectives; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391:2642–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephenson R, Gonsalves L, Askew I, Say L. Detangling and detailing sexual health in the SDG era. Lancet. 2017;390:1014–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boone CA, Bowleg L. Structuring sexual pleasure: equitable access to biomedical HIV prevention for black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:157–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruskin S, Kismödi E. A call for (renewed) commitment to sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure: a matter of health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:159–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing. Sexual pleasure: the forgotten link in sexual and reproductive health and rights. Berkshire: The Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClelland SI. “What do you mean when you say that you are sexually satisfied?” A mixed methods study. Fem Psychol. 2014;24:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmerstig E, Wijma B, Sandell K, Berterö C. “Sexual pleasure on equal terms”: young women’s ideal sexual situations. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33:129–34. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.706342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGlynn C, Westmarland N, Godden N. ‘I just wanted him to hear me’: sexual violence and the possibilities of restorative justice. J Law Soc. 2012;39:213–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter A, Greene S, Money D, et al. The problematization of sexuality among women living with HIV and a new feminist approach for understanding and enhancing women’s sexual lives. Sex Roles. 2017;77:779–800. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Loughlin JI, Brotto LA. Women’s sexual desire, trauma exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33:238–47. doi: 10.1002/jts.22485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird ER, Seehuus M, Clifton J, Rellini AH. Dissociation during sex and sexual arousal in women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:953–64. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooghe M. Is sexual well-being part of subjective well-being? An empirical analysis of Belgian (Flemish) survey data using an extended well-being scale. J Sex Res. 2012;49:264–73. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.551791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascoal PM, Narciso IS, Pereira NM. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. J Sex Res. 2014;51:22–30. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.815149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öberg K, Fugl-Meyer KS, Fugl-Meyer AR. On sexual well-being in sexually abused Swedish women: epidemiological aspects. Sex Relationship Ther. 2002;17:329–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, et al. A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: findings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:145–61. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muise A, Preyde M, Maitland SB, Milhausen RR. Sexual identity and sexual well-being in female heterosexual university students. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:915–25. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorimer K, DeAmicis L, Dalrymple J, et al. A rapid review of sexual wellbeing definitions and measures: should we now include sexual wellbeing freedom? J Sex Res. 2019;56:843–53. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2019.1635565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawshaw P. Whither wellbeing for public health? Crit Public Health. 2008;18:259–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlisle S, Hanlon P. ‘Well-being’ as a focus for public health? A critique and defence. Crit Public Health. 2008;18:263–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plagnol AC. Subjective well-being over the life course: conceptualizations and evaluations. Soc Res. 2010;77:749–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adler A, Seligman ME. Using wellbeing for public policy: theory, measurement, and recommendations. Int J Wellbeing. 2016;6:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulé NJ, Ross LE, Deeprose B, et al. Promoting LGBT health and wellbeing through inclusive policy development. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prather C, Fuller TR, Jeffries WL, 4th, et al. Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health:a review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity. Health Equity. 2018;2:249–59. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.La Placa V, Knight A. Well-being: its influence and local impact on public health. Public Health. 2014;128:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Condron B. Addressing the dimensions of sexual health: a review of evaluated sexual health promotion interventions. Winnipeg, MB: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajos N, Bozon M, Beltzer N, et al. Changes in sexual behaviours: from secular trends to public health policies. AIDS. 2010;24:1185–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328336ad52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dooris M, Farrier A, Froggett L. Wellbeing: the challenge of ‘operationalising’ an holistic concept within a reductionist public health programme. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138:93–99. doi: 10.1177/1757913917711204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunbar JK, Hughes G, Fenton K. In a challenging environment, intelligent use of surveillance data can help guide sexual health commissioners’ choices to maximise public health benefit. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:151–52. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haley DF, Matthews SA, Cooper HLF, et al. Confidentiality considerations for use of social-spatial data on the social determinants of health: sexual and reproductive health case study. Soc Sci Med. 2016;166:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin KM, Woodgate RL. Concept analysis: the holistic nature of sexual well-being. Sex Relationship Ther. 2020;35:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Upadhyay UD, Danza PY, Neilands TB, et al. Development and validation of the sexual and reproductive empowerment scale for adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexander KA, Fannin EF. Sexual safety and sexual security among young Black women who have sex with women and men. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43:509–19. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryant J. Rights, responsibilities and citizenship in heterosexual women’s talk about sex: promoting women’s sexual health and safety. Health Sociol Rev. 2006;15:277–86. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plummer DC. Masculinity and risk: how gender constructs drive sexual risks in the Caribbean. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2013;10:165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva LC, Wright DW. Safety rituals: how women cope with the fear of sexual violence. Qual Rep. 2009;14:747–73. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malone J, Syvertsen JL, Johnson BE, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Bazzi AR. Negotiating sexual safety in the era of biomedical HIV prevention: relationship dynamics among male couples using pre-exposure prophylaxis. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20:658–72. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1368711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith R, Gallagher M, Popkin S, Mireles A, George T. Coercive sexual environments: what MTO tells us about neighborhoods and sexual safety. Cityscape. 2014;16:85–112. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thurston RC, Chang Y, Matthews KA, von Känel R, Koenen K. Association of sexual harassment and sexual assault with midlife women’s mental and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:48–53. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padgett PM. Personal safety and sexual safety for women using online personal ads. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2007;4:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masters NT, Beadnell B, Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Wells EA. Multidimensional characterization of sexual minority adolescents’ sexual safety strategies. J Adolesc. 2013;36:953–61. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffman EE, Mair TTM, Hunter BA, Prince DM, Tebes JK. Neighborhood sexual violence moderates women’s perceived safety in urban neighborhoods. J Community Psychol. 2018;46:79–94. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masters NT, Casey E, Beadnell B, Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Wells EA. Condoms and contexts: profiles of sexual risk and safety among young heterosexually active men. J Sex Res. 2015;52:781–94. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.953023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huo YJ, Binning KR, Molina LE. Testing an integrative model of respect: implications for social engagement and well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36:200–12. doi: 10.1177/0146167209356787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bachmann AS, Simon B. Society matters: the mediational role of social recognition in the relationship between victimization and life satisfaction among gay men. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2014;44:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon B, Eschert S, Schaefer CD, Reininger KM, Zitzmann S, Smith HJ. Disapproved, but tolerated: the role of respect in outgroup tolerance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2019;45:406–15. doi: 10.1177/0146167218787810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon B, Grabow H, Böhme N. On the meaning of respect for sexual minorities: the case of gays and lesbians. Psychol Sex. 2015;6:297–310. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clancy KBH, Cortina LM, Kirkland AR. Opinion: use science to stop sexual harassment in higher education. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:22614–18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016164117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carter A, Greene S, Money D, et al. Supporting the sexual rights of women living with HIV: a critical analysis of sexual satisfaction and pleasure across five relationship types. J Sex Res. 2018;55:1134–54. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1440370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doyle Zeanah P, Schwarz JC. Reliability and validity of the sexual self-esteem inventory for women. Assessment. 1996;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hannier S, Baltus A, De Sutter P. The role of physical satisfaction in women’s sexual self-esteem. Sexologies. 2018;27:e85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leavitt CE, Lefkowitz ES, Waterman EA. The role of sexual mindfulness in sexual wellbeing, relational wellbeing, and self-esteem. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:497–509. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1572680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sakaluk JK, Kim J, Campbell E, Baxter A, Impett EA. Self-esteem and sexual health: a multilevel meta-analytic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2020;14:269–93. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2019.1625281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng X, Fleury M-J, Xiang Y-T, Li M, D’Arcy C. Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53:453–75. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fava NM, Bay-Cheng LY, Nochajski TH, Bowker JC, Hayes T. A resilience framework: sexual health trajectories of youth with maltreatment histories. J Trauma Dissociation. 2018;19:444–60. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2018.1451974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levitt HM, Horne SG, Herbitter C, et al. Resilience in the face of sexual minority stress: “Choices” between authenticity and selfdetermination. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2016;28:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Worthington EL, Jr, Witvliet CVO, Pietrini P, Miller AJ. Forgiveness, health, and well-being: a review of evidence for emotional versus decisional forgiveness, dispositional forgivingness, and reduced unforgiveness. J Behav Med. 2007;30:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall JH, Fincham FD. Self-forgiveness: the stepchild of forgiveness research. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24:621–37. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akhtar S, Barlow J. Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19:107–22. doi: 10.1177/1524838016637079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bell CA, Fincham FD. Humility, forgiveness, and emerging adult female romantic relationships. J Marital Fam Ther. 2019;45:149–60. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adelsberg G. In: Phenomenology and Forgiveness. La Caze M, editor. London: Rowman Littlefield International; 2018. Collective forgiveness in the context of ongoing harms; pp. 131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baskin TW, Enright RD. Intervention studies on forgiveness: a meta-analysis. J Couns Dev. 2004;82:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanchez DT, Crocker J, Boike KR. Doing gender in the bedroom: investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31:1445–55. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gravel EE, Reissing ED, Pelletier LG. Global, relational, and sexual motivation: a test of hierarchical versus heterarchical effects on well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20:2269–89. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Philippe FL, Vallerand RJ, Beaulieu-Pelletier G, Maliha G, Laventure S, Ricard-St-Aubin J-S. Development of a Dualistic model of sexual passion: investigating determinants and consequences. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:2537–52. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01524-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, O’Sullivan LF, Orr DP. The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women. J Adolesc. 2011;34:675–84. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anders KM, Olmstead SB. “Stepping out of my sexual comfort zone”: comparing the sexual possible selves and strategies of college-attending and non-college emerging adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:1877–91. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rubinsky V, Hosek A. “We have to get over it”: navigating sex talk through the lens of sexual communication comfort and sexual self-disclosure in LGBTQ intimate partnerships. Sex Cult. 2019;24:613–29. [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCarthy B, Wald LM. Mindfulness and good enough sex. Sex Relationship Ther. 2013;28:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Landor AM, Ramseyer Winter V. Relationship quality and comfort talking about sex as predictors of sexual health among young women. J Soc Pers Relat. 2019;36:3934–59. [Google Scholar]