Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of liberal fluid resuscitation of adults with severe malaria.

Design, setting, patients and methods

28 Bangladeshi and Indian adults with severe falciparum malaria received crystalloid resuscitation guided by trans-pulmonary thermodilution (PiCCO) in an intensive care setting. Systemic hemodynamics, microvascular indices and measures of acidosis, renal function, and pulmonary edema were followed prospectively.

Results

All patients were hypovolemic (Global end-diastolic volume index (GEDVI) <680ml/m2) on enrolment. Patients received a median (range) 3230mL (390-7300) of isotonic saline in the first 6 hours and 5450mL (710–13720) in the first 24 hours. With resuscitation acid-base status deteriorated in 19/28 (68%) and there was no significant improvement in renal function. Extravascular lung water increased in 17/22 (77%) liberally resuscitated patients; 8 of these patients developed pulmonary edema, 5 of whom died. All other patients survived. All patients with pulmonary edema during the study were hypovolemic or euvolemic at the time pulmonary edema developed. Plasma lactate was lower in hypovolemic patients before (rs=0.38, p=0.05) and after (rs=0.49, p=0.01) resuscitation but was the strongest predictor of mortality before (chi-square=9.9, p=0.002) and after resuscitation (chi-square=11.1, p<0.001) and correlated with the degree of visualized microvascular sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes at both time-points (rs=0.55, p=0.003 and rs=0.43, p=0.03 respectively). Persisting sequestration was evident in 7/15 (47%) patients 48 hours after enrolment.

Conclusions

Lactic acidosis - the strongest prognostic indicator in adults with severe falciparum malaria - results from sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in the microcirculation, not from hypovolemia. Liberal fluid resuscitation has little effect on this sequestration and does not improve acid-base status or renal function. Pulmonary edema - secondary to increased pulmonary vascular permeability - is common, unpredictable, and is exacerbated by fluid loading. Liberal fluid replacement of adults with severe malaria should be avoided.

Keywords: Severe malaria, fluid resuscitation, microcirculation, acute lung injury, acute kidney injury, resource-poor setting

Introduction

Even with optimal antimalarial therapy, the case fatality rate of adults with severe falciparum malaria in a resource-poor setting remains 10-30%. It is estimated that 100,000 adults die from malaria annually [1, 2]

In adults with malaria, the base deficit is the strongest predictor for death [3, 4] and the degree of acute kidney injury (AKI) is an additional independent risk factor [4]. Hypovolemia – which may occur in severe malaria [5, 6] - exacerbates both acidosis and AKI; it might therefore be expected that prompt fluid resuscitation would improve patient outcomes [7, 8]. By analogy the outcome of bacterial sepsis is improved when patients are managed with a bundle of care including aggressive fluid loading [9]. However the microvascular pathology of the two conditions is different; in malaria impaired tissue perfusion results primarily from sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in the microcirculation [10]. The degree of sequestration correlates with acidosis and AKI [10, 11]. Whether fluid loading can overcome this microcirculatory obstruction to improve end-organ perfusion - and ameliorate the resulting acidosis and AKI - is uncertain.

Adults with malaria may have increased pulmonary vascular permeability [12]. This can develop after starting antimalarial therapy and cause pulmonary edema with a mortality of up to 80% in resource-poor settings [13]. A recent randomized trial in African children with severe malaria demonstrated the harmful consequences of liberal fluid resuscitation when compared to maintenance fluids [14]. It is uncertain whether these findings apply to adults given the different spectrum of disease in the two groups; AKI is uncommon in children with severe malaria whereas it occurs in up to 45% of adult patients [15].

To assess the risks and benefits of liberal fluid resuscitation in hypovolemic adult patients with severe malaria, we measured the changes in macrovascular and microvascular hemodynamics in an intensive care setting. We hypothesized that by optimizing volume status carefully, we might improve the acidosis and AKI attributable to hypovolemia without precipitating pulmonary edema and hence improve outcomes. This might generate data to inform the optimal resuscitation strategy for adults with severe malaria.

Methods

Patients

Patients were recruited at Chittagong Medical College Hospital in Bangladesh and Ispat General Hospital in Rourkela, India in 2008. Patients were defined as having Plasmodium falciparum infection if asexual parasites were found on a blood film. As invasive monitoring was being employed, only severely ill adults (>16 years) were enrolled. Severe disease was defined prospectively as: venous base deficit >6meq/L, blood urea nitrogen >60mg/dL or clinical pulmonary edema (defined as oxygen saturation <90% when breathing room air, with bibasal crepitations on chest examination). Patients were enrolled only after written informed consent was obtained from an accompanying relative. Patients were excluded if they had received parenteral antimalarial treatment for >24 hours. All patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Antimalarial treatment was with intravenous artesunate and, apart from the liberal fluid resuscitation, standard supportive care was provided as per current WHO treatment guidelines [16]

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from the Bangladeshi Medical Research Council, the Institutional Ethics Board of Ispat General Hospital, and the Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee. There were regular reviews by local independent safety committees and all deaths and serious adverse events were reported within 24 hours for appraisal.

Investigations

Hemodynamic measurements were performed using transpulmonary thermodilution (PiCCO-plus®, Pulsion Medical Systems, Germany). The physiological basis for measurement of hemodynamic variables using the PiCCO system is described in detail elsewhere [17, 18]. PiCCO-determined variables included: global end diastolic volume index (GEDVI) - a measure of volume status, extra vascular lung water (EVLW) - a measure of pulmonary edema and pulmonary vascular permeability index (PVPI) - a measure of pulmonary capillary leak. Cardiac index (CI) was also determined. Oxygen delivery (DO2I) was calculated using the formula: 1.34 x Hemoglobin concentration x CI x (SaO2/100). The prognostic CAM score was calculated from the Glasgow Coma Scale and plasma base deficit as described previously [4].

Microcirculation

Microvascular flow was assessed directly using orthogonal polarized spectroscopy (OPS) (Microscan, Microvision Medical, The Netherlands) as described previously [10]. Sequestration was deemed to be present if erythrocyte flow velocity was <100μm per second and was expressed as a percentage of visualized capillaries showing these changes. Measurement was performed at baseline, 6 hours later, then daily.

Patient management

Patients had liberal fluid loading in the first 6 hours of the study, with hemodynamic indices measured hourly, guided by the PiCCO device manufacturer’s suggested algorithm (figure 1)[19]; measurements were then repeated every 6 hours until recovery or death. Patients were resuscitated with normal (0.9%) saline; blood was transfused if the hemoglobin concentration fell below 5g/dL. Respiratory support and dialysis were initiated at the attending clinicians’ discretion.

Figure 1. PiCCO guided fluid resuscitation algorithm*.

* PiCCO decision tree as recommended by Pulsion Medical Systems.

CI: Cardiac Index

GEDVI: Global End Diastolic Volume Index

EVLWI: Extravascular lung water Index

V+?: Increase fluid administration?

V-?: Reduce fluid administration/diuresis?

Cat?: Administer inotropic support

A chest radiograph was performed on admission and again if clinically indicated. EVLW was followed closely during resuscitation to identify incipient pulmonary edema; increased pulmonary capillary permeability was diagnosed if PVPI was >3 [20]. In the absence of the availability of reliable measurement of the arterial oxygen partial pressure, pulse oximetry was performed continuously. The pulse oximetry saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (S/F ratio) was used as a measure of acute lung injury (ALI) [21].

Laboratory investigations

Thick and thin films for parasite counts, a full blood count, and plasma biochemistry were performed on admission and then daily until death or recovery. Central venous plasma lactate was measured using an automated point-of-care analyzer (iStat, Abbott Laboratories, New Jersey, USA) on admission, at 6 hours, and then daily. Plasma Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein (PfHRP2) - a measure of parasite biomass - was measured on enrolment by ELISA as described previously [22]. Analysis of acid-base status using Stewart’s approach was performed using published methods [23, 24].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using statistical software (STATA, Version 10, StataCorp). As the data were not normally distributed, comparisons between groups were made using the Kruskal-Wallis or Fisher’s exact test; Spearman’s correlation coefficients are reported. Repeated measures were adjusted for in the analysis as necessary.

Results

Patients

Twenty eight adults with severe malaria were recruited, 17 had received intravenous artesunate before enrolment for a median (range) of 14 (10-24) hours. Five (18%) patients died; the median (range) time to death was 36 (9-98) hours after enrolment (table 1, figure 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of survivors and non-survivors at baseline and after 6 hours of liberal fluid resuscitation (all values are medians (IQR) or raw numbers and percentages).

| Baseline | Post-resuscitation (6 hours) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived (n=23) | Died (n=5) | P | Survived (n=23) | Died (n=5) | P | |

| Macrovascular measures | ||||||

| GEDVI (ml/m2) | 467 (414 – 526) | 577 (470 – 654) | 0.09 | 571 (521 -617) | 634 (564 – 715) | 0.15 |

| CVP (cm H2O) | 5 (-2 to 8) | 6 (0 - 8) | 0.67 | 9 (7 – 13) | 17 (7-26) | 0.21 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 3.17 (2.9 - 3.49) | 2.86 (2.6 - 3.15) | 0.14 | 3.47 (3.17 - 4.38) | 3.67 (2.46 -3.95) | 0.88 |

| DO2I (ml/min/m2) | 426 (329 – 493) | 394 (327 – 477) | 0.74 | 432 (328 -542) | 360 (217 -474) | 0.32 |

| SVRI (dynes-sec/cm5/m5) | 1936 (1653 - 2295) | 2700 (2293 - 3438) | 0.02 | 1926 (1545 -2533) | 2250 (1631 -3694) | 0.54 |

| Microvascular measures | ||||||

| Sequestration (% capillaries) | 10 (1.7 - 30) | 38.4 (14.2 -48.9) | 0.053 | 5.9 (2.1 – 11.7) | 21.7 (5.5 - 40.4) | 0.17 |

| PfHRP2 (ng/mL)* | 5.8 (4.1 - 7.5) | 14 (0 - 29) | 0.046 | - | - | |

| Respiratory measuresa | ||||||

| EVLW (ml/kg) | 8 (6 - 9) | 9 (6 - 12) | 0.55 | 10 (7-11) | 10(9-18) | 0.15 |

| PVPI | 2.4 (1.87 - 2.58) | 2.32 (1.73 - 2.6) | 0.45 | 2.2 (1.97 – 2.6) | 2.28 (1.9 -3.64) | 0.92 |

| SaO2/FiO2 ratio | 452 (280 – 467) | 303 (240 – 465) | 0.63 | 448 (347 – 462) | 196 (168 – 273) | 0.005 |

| Clinical measures | ||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 14 (10 - 15) | 8 (5 - 9) | 0.01 | 14 (13-15) | 7 (6-8) | 0.02 |

| MABP (mmHg) | 86 (75 - 96) | 98 (93 – 107) | 0.05 | 98 (93 - 107) | 105 (91-114) | 0.19 |

| CAM score* | 2 (1 – 3) | 4b | 0.001 | - | - | |

| Laboratory measuresc | ||||||

| pH | 7.34 (7.33 - 7.37) | 7.3 (7.11 - 7.36) | 0.09 | 7.31 (7.26 -7.34) | 7.2 (6.91 -7.32) | 0.06 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.3 (1.8 – 3.4) | 8.3 (5.6 – 11.4) | 0.002 | 1.5 (1.1 – 2) | 5.5 (3.9 -8.6) | <0.001 |

| Base deficit (meq/L) | 8 (7 - 11) | 17 (13 - 21) | 0.002 | 12 (9-14) | 19 (14-25) | 0.004 |

| Plasma bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 17.3 (14.6 - 18.2) | 10.1 (8 - 13) | 0.002 | 15.1 (12.7 -17.5) | 9.3 (6.9 – 12.2) | 0.002 |

| Plasma sodium (mmol/L) | 134 (131 - 138) | 134 (127 - 144) | 0.86 | 139 (137 -142) | 141 (137 -146) | 0.67 |

| Plasma potassium (mmol/L) | 3.9 (3.5 – 4.3) | 3.7 (3.6 – 4.4) | 0.88 | 3.8 (3.6 -4.2) | 4.3 (3.9 -4.6) | 0.19 |

| Plasma chloride (mmol/L) | 104 (101 -105) | 105 (100 - 114) | 0.35 | 109 (105-111) | 113 (110 -119) | 0.09 |

| Plasma anion gap (mmol/L) | 19 (16 - 20) | 22 (17 - 26) | 0.16 | 19 (18 -20) | 22 (19-25) | 0.09 |

| Plasma strong ion gap (meq/L) | 11.6 (8.4 – 16.5) | 8.4 (-0.5 to 12.1) | 0.13 | 12.4 (9.4 – 14.7) | 11.7 (2 – 14.6) | 0.71 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 40 (32-68) | 54 (27 -70) | 0.72 | 35 (24.8 -61.5) | 52 (34.5 -66.5) | 0.47 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL)* | 1.95 (1.2 - 3.15) | 1.9 (1.15 - 2.2) | 0.48 | - | - | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.2 (8.5 - 12.6) | 10.5 (9.4 - 12.1) | 0.7 | 9.2 (7.4 – 10.5) | 7.8 (6.1 -9.9) | 0.22 |

| White cell count (x 109/L)* | 8 (6.3 – 9.6) | 7.3 (5.4 – 14.1) | 0.7 | - | - | |

| Platelet count (x 109/L)* | 28 (16 - 56) | 19 (11 - 27) | 0.14 | - | - | |

GEDVI: Global end diastolic index, CVP: central venous pressure, CI: Cardiac index, DO2I: Oxygen delivery index, PfHRP2: Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein, SVRI: Systemic vascular resistance index, EVLW: Extra vascular lung water, PVPI: pulmonary vascular permeability index, MABP: mean arterial blood pressure, CAM score: Coma acidosis malaria score.

Post resuscitation values exclude 2 surviving patients who developed aspiration pneumonia in the first 6 hours.

Only patients with a CAM score of 4 died

Post resuscitation indices exclude 1 surviving patient who had dialysis in the first 6 hours.

These variables were not measured at 6 hours.

Figure 2. Clinical course of the patients.

CPE: Clinical pulmonary edema: Oxygen saturation <90% and bibasal crepitations

ARF: Acute renal failure: Blood Urea Nitrogen >60mg/dL

Fluid resuscitation

All patients were hypovolemic on enrolment: median (range) GEDVI 481ml/m2 (346–675) (normal range: 680-800ml/m2). Guided by the PiCCO algorithm, patients received a median (range) normal saline load of 3,230mL (390-7,300) in the first 6 hours and a median (range) of 5450mL (710–13720) over the first 24 hours. There was no relationship between patient outcome and the volume of fluid administered over either time period (p=0.74 and p=0.49 respectively). Blood was transfused in 4 patients but in all cases this occurred after the initial 6 hour resuscitation phase.

Systemic hemodynamics

In accordance with the PiCCO algorithm, the two patients with clinical pulmonary edema (CPE) on enrolment were not fluid resuscitated. Two additional patients had no baseline volumetric data due to poor positioning of the central venous catheter. In the remaining patients there was a median increase in GEDVI, CI and DO2I after 6 hours of fluid resuscitation (table 2). The relatively small rise in DO2I was related to the concomitant fall in hemoglobin.

Table 2. Response of hemodynamic, microvascular, clinical and laboratory measures to fluid resuscitation and correlation with volume of fluid administered. All numbers are medians (IQR).

| Variable | Admission | After 6 hours of fluid resuscitation | Change with 6 hours of fluid resuscitation | Correlation between change and volume of fluid administered | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemodynamic measures | rs | p | |||

| GEDVI (ml/m2) | 472 (429 to 571) | 585 (539 to 638) | 91 (10 to 126) | 0.1 | 0.65 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 3.08 (2.81 to 3.31) | 3.64 (3.31 to 4.21) | 0.49 (0.07 to 1,12) | 0.19 | 0.35 |

| DO2i (mL/min/m2) | 421 (335 to 479) | 403 (327 to 528) | 15 (-109 to 79) | -0.23 | 0.26 |

| CVP (cm H2O) | 4.5 (-2.5 to 8) | 10 (7 to 13.5) | 5.5 (1 to 10) | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| MABP (mmHg) | 87.5 (77.3 to 98.8) | 93.5 (80.5 to 106) | 6 (-3.3 to 13.5) | 0.15 | 0.46 |

| SVRI (dynes-sec/cm5/m5) | 2155 (1779 to 2532) | 1926(1552 to 2320) | -203 (-751 to 170) | -0.04 | 0.86 |

| Respiratory measuresa | |||||

| SaO2/FiO2 ratio | 455 (306 to 467) | 433 (271 to 462) | -9 (-23 to 2) | 0.16 | 0.47 |

| EVLW (ml/kg) | 8 ( 6 to 9) | 10 (8 to 11) | 1 (1 to 3) | 0.42 | 0.05 |

| PVPI | 2.29(1.82 to 2.45) | 2.25(1.97 to 2.26) | 0.05 (-0.16 to 0.32) | 0.58 | 0.004 |

| Microcirculation measures | |||||

| Sequestration (% blocked capillaries) | 15 (2.5 to 32.9) | 7.5 (1.7 to 22.1) | -6.7 (-19.2 to 4.2) | -0.23 | 0.31 |

| Acid-base measures | |||||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 3.2 (1.9 to 5.4) | 1.7 (1.4 to 3.1) | -1 (-1.8 to -0.3) | 0.35 | 0.08 |

| pH | 7.34 (7.32 to 7.37) | 7.31 (7.24 to 7.34) | -0.05 (-0.1 to 0.01) | -0.61 | <0.001 |

| Base deficit (mEq/L) | 9 (8 to 12) | 13 (10 to 14) | 3(0-5) | 0.82 | <0.0001 |

| Anion Gap (mmol/L) | 19 (16 to 21) | 19 (19 to 22) | 1 (-1 to 3) | 0.53 | 0.007 |

| SIDa (mEq/L) | 34.5(32.7 to 36.6) | 34.6 (31.2 to 36,2) | 0.1 (-1.5 to 1.4) | -0.09 | 0.67 |

| SIDe (mEq/L) | 22.8 (19.6 to 27.1) | 21.6 (20.3 to 26) | -0.7 (-4 to 1.1) | -0.6 | 0.002 |

| SIG (mEq/L) | 11.2 (7.2 to 15.2) | 12.4 (9.4 to 15.2) | 1.3 (-2.1 to 3.6) | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Venous CO2 (mmHg) | 28.4 (22.6 to 33.2) | 30.3 (26.5 to32.6) | 1.2 (-1.5 to 5) | -0.25 | 0.24 |

| Other laboratory measures | |||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.4 (8.5 to 12.6) | 9.1 (7.1-10.5) | -1.6 (-2.5 to -0.2) | -0.34 | 0.08 |

| Plasma Sodium (mmol/L) | 134 (131 to 138) | 139 (137 to 143) | 5 (3 to 7) | 0.59 | 0.002 |

| Plasma Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.8 (3.5 to 4.3) | 3.9 (3.6 to 4.3) | 0 (-0.1 to 0.2) | -0.08 | 0.69 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 104 (100 to 106) | 110 (107 to 113) | 6(4-8) | 0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Renal measuresb | Admission | After 24 hours of fluid resuscitation | Change with 24 hours of fluid resuscitation | rs | p |

| Plasma creatinine (mgl/dL) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.5 (1 to 2.4) | -0.3 (-0.7 to 0.2) | -0.14 | 0.56 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (mgl/dL) | 44 (32 to 68) | 36 (20 to 64) | -9 (-20 to -3) | -0.47 | 0.03 |

rs: Spearmans coefficient. GEDVI: Global end diastolic index, CI: Cardiac index, DO2I: Oxygen delivery index, CVP: central venous pressure, MABP: mean arterial blood pressure SVRI: Systemic vascular resistance index, EVLW: Extra vascular lung water, PVPI: pulmonary vascular permeability index, SIDa: apparent strong ion deficit, SIDe: effective strong ion deficit, SIG: strong ion gap.

Respiratory assessment excludes the two patients with clinical pulmonary edema on admission and the 2 patients who developed aspiration pneumonia.

Renal indices exclude the 4 patients who had dialysis in the first 24 hours of their hospitalization and excludes the patients with clinical pulmonary edema on admission who did not receive liberal fluid resuscitation.

Microcirculation

Excluding the one patient with no sequestration visible at either time point, 8/21 (38%) showed no change or an increase in sequestration after six hours of resuscitation. Neither patient with CPE on admission was resuscitated: sequestration increased in one and did not change in the other. Two other patients had no OPS at baseline (in 1 there was equipment malfunction and the other had unquantifiable images) and two had no OPS post-resuscitation (1 declined examination, 1 had unquantifiable images). Sequestration was still present in 47% of those assessed 48 hours after admission.

Acidosis

Although plasma lactate fell slightly over the first 6 hours in resuscitated patients, 18/26 (69%) had a concurrent fall in venous pH and a rise in base deficit. Plasma chloride increased in all 26 patients. The changes in pH, base deficit, and plasma chloride all correlated with the volume of administered fluid, whereas the change in lactate did not (table 2). Sufficient data to allow analysis of acid-base status using Stewart’s approach was available for 25 patients (table 3); 21/23 (91%) resuscitated patients had an elevated strong ion gap (SIG) at baseline (normal <5meq/L), and 14/23 (61%) had a rise in SIG with resuscitation. This rise correlated with the volume of fluid administered. The worsening of base deficit with fluid resuscitation correlated with the increase in the effect of other strong anions on acid-base status.

Table 3. Association between disease severity (CAM score), plasma lactate and microvascular indices and systemic hemodynamic indices before and after resuscitation. All values are Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

| Correlation with CAM score on admission | Correlation with plasma lactate on admission | Correlation with plasma lactate after fluid resuscitation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs | rs | rs | |

| SequestrationΛ | 0.41 Ψ | 0.55 Ω | 0.43Ψ |

| PfHRP2* | 0.48 Ψ | 0.49 Ω | 0.53Ω |

| GEDVI | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.49Ω |

| CI | -0.17 | -0.36 | -0.1 |

| DO2I | 0.09 | -0.11 | -0.26 |

CAM: Coma acidosis malaria score. rs: Spearman s coefficient. SVRI: Systemic vascular resistance index, PfHRP2: parasite biomass: Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein 2, GEDVI: Global end diastolic index, DO2I: Oxygen delivery index

Measured as % blocked capillaries

Both correlations are with the baseline PfHRP2

p<0.05

p<0.01

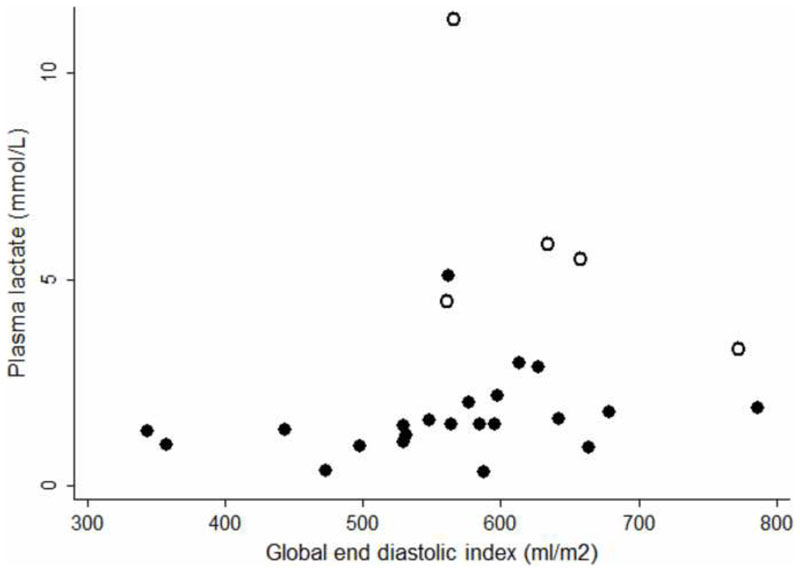

Correlations between microvascular and macrovascular variables, acidosis, and outcome

Venous plasma lactate was the strongest predictor of a fatal outcome before (chi-squared 9.9, p=0.002) and after (chi-squared 11.1, p<0.001) resuscitation. Microvascular indices (sequestration and parasite biomass) correlated with plasma lactate before and after resuscitation, whereas the macrovasular indices of CI and DO2I did not. The degree of sequestration was greater in fatal cases before and after resuscitation, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (tables 1 & 4 & figure 3). GEDVI was associated with plasma lactate, but the more hypovolemic patients had lower plasma lactate concentrations (tables 1 & 4 & figure 4).

Table 4. Characteristics of patients who developed pulmonary edema with resuscitation (all values are medians (IQR) or raw numbers and percentages)Λ.

| Developed CPE n=8 | Did not develop CPE n=16 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease severity and outcome | |||

| CAM score* | 4 (2-4) | 3 (1-3) | 0.057 |

| Died | 5/8 (63%) | 0/16 | 0.001 |

| Developed generalized edema | 7/8 (88%) | 6/16 (38%) | 0.03 |

| Volume of fluid administered | |||

| Over first 6 hours (mL) | 3400 (2638 - 5175) | 3485 (2678 - 5813) | 0.67 |

| Over first 24 hours (mL) | 5900 (3270 -10150) | 6000 (4646 - 9800) | 0.55 |

| Respiratory indices* | |||

| S/F ratio | 376 (253 - 461) | 462 (353 – 467) | 0.08 |

| RR (breaths/minute) | 33 (25 – 36) | 29 (25 - 32) | 0.44 |

| EVLW (ml/kg) | 9 (7-10) | 8 (6 - 9) | 0.41 |

| PVPI | 2.12 (1.69 – 2.52) | 2.33 (1.99 - 2.45) | 0.41 |

| Measures of acidosis* | |||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 6.3 (2.4 – 9.6) | 2.7 (1.9 – 4.1) | 0.04 |

| pH | 7.33 (7.17 -7.38) | 7.34 (7.32 -7.37) | 0.58 |

| Base deficit (meq/L) | 13 (7-19) | 9 (7 – 12) | 0.15 |

| Macrovacular indices* | |||

| CVP (cm H2O) | 7 (1 – 8) | 3 (-3 – 7) | 0.15 |

| GEDVI (ml/m2) | 594 (451 - 631) | 466 (398 - 522) | 0.07 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 3.15 (2.84 - 3.35) | 3.0 (2.72 - 3.24) | 0.62 |

| DO2i (mL/min/m2) | 393 (318 - 468) | 426 (324 – 535) | 0.39 |

| SVRI (dynes-sec/cm5/m5) | 2349 (2132 - 3075) | 1852 (1562 - 2371) | 0.08 |

| Microvascular indices* | |||

| Sequestration (% blocked capillaries) | 32 (7 – 45) | 15 (1.7 – 30) | 0.26 |

| HRP2 (ng/mL) | 7.7 (2.5 – 12.4) | 5.5 (3.5 – 9.6) | 0.58 |

| Renal function* | |||

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.9 (1.5 – 3.4) | 2.0 (1.2 – 3.1) | 0.97 |

| Anuric | 4/8 (50%) | 2/16 (13%) | 0.13 |

GEDVI: Global end diastolic index, CVP: central venous pressure, CI: Cardiac index, DO2I: Oxygen delivery index, PfHRP2: Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein, SVRI: Systemic vascular resistance index, EVLW: Extra vascular lung water, PVPI: pulmonary vascular permeability index, MABP: mean arterial blood pressure, CAM score: Coma acidosis score.

Excludes the two patients with clinical pulmonary edema on admission and the 2 patients that developed aspiration pneumonia.

Measured on admission

Figure 3. Before resuscitation: closed dots: survivors, open dots: fatal cases (rs=0.38 p=0.05).

Figure 4. After 6 hours of liberal fluid resuscitation: closed dots: survivors, open dots: fatal cases (rs=0.49 p<0.01).

Renal function

There was no association between volume status and renal function on enrolment (rs=0, p=0.97). With 24 hours of fluid resuscitation there was a clinically insignificant median (IQR) fall in the plasma creatinine of 0.2mg/dL (-0.7 to 0.6); this was not statistically significant (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, p=0.2). There was no association between the volume of fluid administered and the change in creatinine (rs=-0.14, p=0.56). No anuric patient regained a urine output with resuscitation; 6/8 (75%) required dialysis and two died with concomitant CPE. In patients with significant renal impairment (plasma creatinine>2mg/dL) still passing urine, 4/8 (50%) had an increase in plasma creatinine despite 24 hours’ resuscitation. After 24 hours, the more hypovolemic (assessed using GEDVI) patients had a lower plasma creatinine concentrations (rs=-0.59, p=0.01).

Lung water and pulmonary edema

On admission GEDVI correlated with EVLW (rs=0.5, p=0.01). Six hours of fluid resuscitation resulted in an increase in EVLW in 17/22 (77%) patients (excluding two patients with aspiration pneumonia). Concurrently in 12/22 (55%) the S/F ratio fell; the value post-resuscitation was correlated with outcome.

The two patients with CPE on admission were also hypovolemic (GEDVI: 502ml/m2 and 506ml/m2 respectively). During the study, eight additional patients developed CPE – when CPE developed, five were still hypovolemic (GEDVI range: 561-645ml/m2) and 3 were euvolemic (range 685-759ml/m2). All but one patient who developed CPE had a PVPI>3 (in the absence of positive airways pressure), the other patient’s PVPI was 2.97. All 10 patients with CPE required respiratory support (seven endotracheal mechanical ventilation, three non-invasive continuous positive airway pressure ventilation) and five (50%) died. These were the only deaths during the study. Five additional patients with neither CPE nor aspiration pneumonia had a PVPI>3 at some point in the study. Therefore, 15 (58%) of the 26 patients had either CPE or volumetric evidence of increased pulmonary capillary permeability.

There was no relationship between the development of CPE and the volume of fluid administered over the first 6 hours (p=0.67) or 24 hours (p=0.55). Patients who went on to develop CPE with resuscitation generally had more severe disease although only admission plasma lactate was significantly higher in the univariate analysis (table 4) and 4/10 patients with CPE had a CAM score ≤2.

Hypovolemia and peripheral edema

Despite liberal fluid resuscitation, most patients (93%) still had a GEDVI<680ml/m2 at 6 hours and at 24 hours (88%). Patients who died had a median (IQR) fall in GEDVI of 58ml/m2 (45-89) in the first 24 hours compared with a 67ml/m2 (7-145) rise in survivors (p=0.008). Marked generalized peripheral edema developed in 14/26 (54%) resuscitated patients. Patients with generalized edema were more likely to die (p=0.04) and more likely to develop CPE (p=0.03). Patients developing generalized edema had a trend to receiving more fluid than those who did not – a median (IQR) of 3800mL (2998-5738) versus 2765mL (2271-3545) in the first 6 hours (p=0.07) and 7770mL (5075–10025) versus 5053mL (3506–6728) in the first 24 hours (p=0.08). No patient had clinical evidence of cerebral edema in the study.

Discussion

In this prospective study of hypovolemic adult patients with severe falciparum malaria, liberal PiCCO-guided fluid resuscitation with normal saline led to a small decrease in plasma lactate but no meaningful improvement in acid-base status or renal function. Despite close monitoring in an ICU setting, increased pulmonary capillary permeability led to pulmonary edema in a third of the patients receiving fluid resuscitation, and the majority of these patients died. Half the patients in the series developed severe generalized edema - indirect evidence of increased systemic vascular permeability – mortality was higher in this group. Hypovolemia was not associated with more severe disease; instead disease severity correlated with the degree of visualized microvascular sequestration, a relationship which persisted after liberal fluid loading. Liberal volume loading had little effect on sequestration and its sequelae, whilst increasing the risk of potentially lethal complications. Taken together with the recent evidence of harm in children [14] this suggests that liberal fluid resuscitation in severe falciparum malaria is contraindicated.

The study aimed to determine if fluid resuscitation would improve the acidosis and kidney injury attributable to hypovolemia in patients with severe malaria. However acidosis and AKI were not more severe in hypovolemic patients and neither improved significantly with fluid loading. Despite liberal resuscitation no anuric patient re-established a urine output and two additional patients later developed AKI. Half of the patients with significantly impaired renal function on admission still passing urine had a deterioration in in plasma creatinine despite a median fluid load of almost 8 liters in the first 24 hours. Remarkably, at 24 hours the more hypovolemic patients had lower plasma creatinine levels. Autopsy studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between the degree of sequestration in the renal circulation and the presence of malaria associated AKI [11]. Our data suggest that fluid loading does little to overcome this.

Approximately 70% of patients had their acid-base status deteriorate with resuscitation. This resulted from an elevated SIG present in over 90% of patients on admission which increased further with fluid resuscitation. An elevated SIG has been noted previously in adults with severe malaria and in a larger series was independently associated with a fatal outcome [25], although there remains uncertainty over the identity and origin of the component strong anions. In this small series, the SIG was not higher in fatal cases before or after resuscitation and the etiology of the rise in SIG with fluid resuscitation is unclear.

Plasma lactate concentration, the acid-base measure with the strongest prognostic value - before and after resuscitation, - correlated with the degree of visualized parasitized erythrocyte sequestration at both time-points. Sequestration has been considered central to the pathophysiology of severe falciparum malaria for over 100 years [26] with early pathological observations confirmed by more recent in vivo and autopsy studies [10, 27]. Although microvascular dysfunction occurs in sepsis [28], and improves with fluid loading [29], the pathophysiology is quite different in falciparum malaria where parasitized erythrocytes bind strongly to the endothelium obstructing microcirculatory flow [30]. In this series liberal fluid resuscitation had little effect on sequestration and plasma lactate; the volume of fluid resuscitation did not correlate with the change in either. Despite continuing fluid therapy almost half of the patients with microcirculatory assessment still had evidence of sequestration 48 hours after enrolment, up to 72 hours after administration of the rapidly acting antimalarial artesunate.

It was hoped that the use of volumetric measures to identify a critical increase in EVLW would allow the safe administration of fluid individualized to the patient’s deficit. However, even with intensive monitoring – seldom available in resource-poor settings where malaria is managed - there was a high incidence of CPE. All patients were hypovolemic or euvolemic when CPE developed and did not receive more fluid than patients without this complication. Troublingly, there was no clinical or laboratory index that reliably predicted whether pulmonary edema would occur. Notably admission PVPI was no higher in those who would later develop CPE.

An increase in systemic vascular permeability has been reported previously in adults with malaria [31]. In this series there were indirect data to suggest this had prognostic significance. The GEDVI fell in the first 24 hours in all the patients who died despite continuing fluid administration. The patients who developed marked generalized edema were more likely to die and to develop CPE. The mechanism for an increased vascular permeability in patients with malaria is uncertain, although angiopoietin-2 - a molecule associated with endothelial activation and increased mortality in malaria [32] and linked with increased systemic capillary permeability [33] and ALI [34] in the critical care setting - may play a role.

These observations should be viewed in the context of recent concerns about liberal fluid resuscitation [35]. Conservative fluid regimens have proved beneficial in patients with ALI [36] and aggressive resuscitation has been shown to be harmful in other settings [37, 38]. In patients with severe malaria, a retrospective study of Vietnamese adults demonstrated no improvement in acidosis or renal function with fluid loading [39]. In African children with severe malaria there was an unsuspected dramatic increase in mortality in those resuscitated liberally [14].

In previous studies, Bangladeshi patients with severe malaria and CAM scores of 2 and 3 had a mortality rate of 27% and 36% respectively when managed with intravenous artesunate on a general ward [4]. The case fatality rate was 18% in the present study, no patient with a CAM score <4 died. This presumably reflects the intensive care management possible in this series – rare in the resource-poor settings where patients with malaria will be managed.

The study has limitations. The number of patients was small and a majority had received antimalarial therapy before enrolment. All had been unwell for >48 hours, the majority for >5 days; earlier resuscitation may have led to different outcomes. PiCCO-based resuscitation algorithms are not validated in this population and in an earlier study were associated with a greater positive fluid balance [38]. Finally, patient outcome might have been different in better resourced ICU settings [40]

Conclusions

This study shows a strong association between directly observed microvascular sequestration and clinical endpoints, and a failure of liberal fluid resuscitation to meaningfully improve sequestration, acid-base status or renal function. The high rate of potentially lethal pulmonary edema and evidence of harm in other recent studies [14, 39] strongly suggests that a more cautious approach to fluid therapy in adults with severe malaria is warranted.

Figure 5. Before fluid resuscitation: closed dots: survivors, open dots: fatal cases (rs=0.55, p=0.003).

Figure 6. After 6 hours of fluid resuscitation: closed dots: survivors, open dots: fatal cases (rs=0.43, p=0.03).

Table 5. Analysis of the change in acid-base status with resuscitation using the Stewart approach.

| Variable | Median (IQR) Δ with fluid load | Correlation with fluid load | Correlation with Δ base deficit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | p | rs | p | ||

| Chloride effect | -2.4 (-3.7–1.3) | -0.21 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.4 |

| Albumin effect | 0.6 (0.1 – 1.6) | -0.18 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.93 |

| Free H20 effect | 1.2 (0.3 – 2) | 0.58 | 0.002 | -0.46 | 0.02 |

| Lactate effect | 1.2 (0.4 – 1.8) | -0.1 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.008 |

| Other strong ions | -3.9 (-6.4 – 0.4) | -0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.001 |

rs: Spearman’s correlation coefficient

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the doctors and nurses of the Intensive Care Units of Chittagong Medical College Hospital and Ispat General Hospital. They would also like to thank Dr David Bihari, Dr Kesinee Chotivanich, Mr Martin Boyle and Ms Sophie Cohen for valuable advice and support during the preparation of the study.

Role of the funding source

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. The Wellcome Trust however played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Study location: The clinical work in this study was performed at Chittagong Medical College Hospital, Chiattagong, Bangladesh and Ispat General Hospital, Rourkela, India.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest

Reprints will not be sought, but information regarding the study can be obtained from Dr Hanson via drjoshhanson@gmail.com

References

- 1.Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):717–725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Malaria Report. World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day NP, Phu NH, Mai NT, Chau TT, Loc PP, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, Holloway P, Hien TT, White NJ. The pathophysiologic and prognostic significance of acidosis in severe adult malaria. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(6):1833–1840. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson J, Lee SJ, Mohanty S, Faiz MA, Anstey NM, Charunwatthana P, Yunus EB, Mishra SK, Tjitra E, Price RN, et al. A simple score to predict the outcome of severe malaria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):679–685. doi: 10.1086/649928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sitprija V, Napathorn S, Laorpatanaskul S, Suithichaiyakul T, Moollaor P, Suwangool P, Sridama V, Thamaree S, Tankeyoon M. Renal and systemic hemodynamics, in falciparum malaria. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16(6):513–519. doi: 10.1159/000169042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis TM, Krishna S, Looareesuwan S, Supanaranond W, Pukrittayakamee S, Attatamsoonthorn K, White NJ. Erythrocyte sequestration and anemia in severe falciparum malaria. Analysis of acute changes in venous hematocrit using a simple mathematical model. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(3):793–800. doi: 10.1172/JCI114776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Management of life-threatening acid-base disorders. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(1):26–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1448–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, Linde-Zwirble WT, Marshall JC, Bion J, Schorr C, Artigas A, Ramsay G, Beale R, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):367–374. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0cdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dondorp AM, Ince C, Charunwatthana P, Hanson J, van Kuijen A, Faiz MA, Rahman MR, Hasan M, Bin Yunus E, Ghose A, et al. Direct in vivo assessment of microcirculatory dysfunction in severe falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(1):79–84. doi: 10.1086/523762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguansangiam S, Day NP, Hien TT, Mai NT, Chaisri U, Riganti M, Dondorp AM, Lee SJ, Phu NH, Turner GD, et al. A quantitative ultrastructural study of renal pathology in fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria. TropMedInt Health. 2007;12(9):1037–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charoenpan P, Indraprasit S, Kiatboonsri S, Suvachittanont O, Tanomsup S. Pulmonary edema in severe falciparum malaria. Hemodynamic study and clinicophysiologic correlation. Chest. 1990;97(5):1190–1197. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.5.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor WR, Canon V, White NJ. Pulmonary manifestations of malaria : recognition and management. Treat Respir Med. 2006;5(6):419–428. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200605060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, Engoru C, Olupot-Olupot P, Akech SO, Nyeko R, Mtove G, Reyburn H, Lang T, et al. Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2483–2495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Severe falciparum malaria. World Health Organization, Communicable Diseases Cluster. Trans R Soc Trop MedHyg. 2000;94(1):S1–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. second edn. World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godje O, Hoke K, Goetz AE, Felbinger TW, Reuter DA, Reichart B, Friedl R, Hannekum A, Pfeiffer UJ. Reliability of a new algorithm for continuous cardiac output determination by pulse-contour analysis during hemodynamic instability. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litton E, Morgan M. The PiCCO monitor: a review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40(3):393–409. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PiCCO decision tree. Pulsion Medical Systems; Munich: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monnet X, Anguel N, Osman D, Hamzaoui O, Richard C, Teboul JL. Assessing pulmonary permeability by transpulmonary thermodilution allows differentiation of hydrostatic pulmonary edema from ALI/ARdS. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(3):448–453. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB. Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007;132(2):410–417. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dondorp AM, Desakorn V, Pongtavornpinyo W, Sahassananda D, Silamut K, Chotivanich K, Newton PN, Pitisuttithum P, Smithyman AM, White NJ, et al. Estimation of the total parasite biomass in acute falciparum malaria from plasma PfHRP2. PLoS Med. 2005;2(8):e204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellum JA, Kramer DJ, Pinsky MR. Strong ion gap: a methodology for exploring unexplained anions. J Crit Care. 1995;10(2):51–55. doi: 10.1016/0883-9441(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figge J, Mydosh T, Fencl V. Serum proteins and acid-base equilibria: a follow-up. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120(5):713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dondorp AM, Chau TT, Phu NH, Mai NT, Loc PP, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, Taylor A, Hien TT, White NJ, et al. Unidentified acids of strong prognostic significance in severe malaria. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1683–1688. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000132901.86681.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchiafava E, Bignami A. On Summer-Autumnal Fever. New Sydenham Society. 1894 [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacPherson GG, Warrell MJ, White NJ, Looareesuwan S, Warrell DA. Human cerebral malaria. A quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. The American journal of pathology. 1985;119(3):385–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ince C, Sinaasappel M. Microcirculatory oxygenation and shunting in sepsis and shock. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1369–1377. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ospina-Tascon G, Neves AP, Occhipinti G, Donadello K, Buchele G, Simion D, Chierego ML, Silva TO, Fonseca A, Vincent JL, et al. Effects of fluids on microvascular perfusion in patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(6):949–955. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho M, White NJ. Molecular mechanisms of cytoadherence in malaria. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(6 Pt 1):C1231–1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.6.C1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis TM, Suputtamongkol Y, Spencer JL, Ford S, Chienkul N, Schulenburg WE, White NJ. Measures of capillary permeability in acute falciparum malaria: relation to severity of infection and treatment. Clinical infectious diseases. 1992;15(2):256–266. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeo TW, Lampah DA, Gitawati R, Tjitra E, Kenangalem E, Piera K, Price RN, Duffull SB, Celermajer DS, Anstey NM. Angiopoietin-2 is associated with decreased endothelial nitric oxide and poor clinical outcome in severe falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(44):17097–17102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805782105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Meurs M, Kumpers P, Ligtenberg JJ, Meertens JH, Molema G, Zijlstra JG. Bench-to-bedside review: Angiopoietin signalling in critical illness - a future target? Crit Care. 2009;13(2):207. doi: 10.1186/cc7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Heijden M, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, van Hinsbergh VW, Groeneveld AB. Angiopoietin-2, permeability oedema, occurrence and severity of ALI/ARDS in septic and non-septic critically ill patients. Thorax. 2008;63(10):903–909. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.087387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada TA, Walley KR, Russell JA. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):259–265. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF, Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alsous F, Khamiees M, DeGirolamo A, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Negative fluid balance predicts survival in patients with septic shock: a retrospective pilot study. Chest. 2000;117(6):1749–1754. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Sugihara M, French C, Stephens D, Wendon J, Honore P, Mulder J, Turner A. Pulmonary artery catheter versus pulse contour analysis: a prospective epidemiological study. Crit Care. 2006;10(6):R174. doi: 10.1186/cc5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phu NH, Hanson J, Bethell D, Mai NT, Chau TT, Chuong LV, Loc PP, Sinh DX, Dondorp A, White N, et al. A retrospective analysis of the haemodynamic and metabolic effects of fluid resuscitation in vietnamese adults with severe falciparum malaria. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruneel F, Tubach F, Corne P, Megarbane B, Mira JP, Peytel E, Camus C, Schortgen F, Azoulay E, Cohen Y, et al. Severe imported falciparum malaria: a cohort study in 400 critically ill adults. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]