Abstract

Spatially controlled, cargo-specific endocytosis is essential for development, tissue homeostasis and cancer invasion. Unlike cargo-specific clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the clathrin- and dynamin-independent endocytic pathway (CLIC-GEEC, CG pathway) is considered a bulk internalization route for the fluid phase, glycosylated membrane proteins and lipids. While the core molecular players of CG-endocytosis have been recently defined, evidence of cargo-specific adaptors or selective uptake of proteins for the pathway are lacking. Here we identify the actin-binding protein Swiprosin-1 (Swip1, EFHD2) as a cargo-specific adaptor for CG-endocytosis. Swip1 couples active Rab21-associated integrins with key components of the CG-endocytic machinery—Arf1, IRSp53 and actin—and is critical for integrin endocytosis. Through this function, Swip1 supports integrin-dependent cancer-cell migration and invasion, and is a negative prognostic marker in breast cancer. Our results demonstrate a previously unknown cargo selectivity for the CG pathway and a role for specific adaptors in recruitment into this endocytic route.

Endocytosis is a vital process involving the internalization of extracellular material and cell surface receptors. This controls various functions ranging from fluid-phase nutrient uptake and spatially and temporally regulated traffic of adhesion and growth-factor receptors, to pathogen entry1. The predominant view is that the specificity of endocytosis is achieved through cargo-specific adaptors, as described for clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME)2,3. This raises the possibility that as-yet unidentified cargo adaptor proteins could function as key gatekeepers for other endosomal routes.

The clathrin- and dynamin-independent endocytic pathway (CG pathway) internalizes a major fraction of the extracellular fluid phase, glycosylphosphotidylinositol-anchored proteins and other cell surface receptors—including nutrient transporters, ion channels and cell adhesion receptors4,5—as well as bacterial and viral pathogens4,6. This occurs through high-capacity tubulovesicular membrane uptake carriers called clathrin-independent carriers (CLICs)7,8. CLICs are formed via the recruitment of Arf1, the actin-binding BAR-domain protein IRSp53 and Arp2/3 to the membrane, followed by Cdc42 activation of IRSp53 and Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization, presumptively resulting in the scission of CLICs and generation of CG endosomes9. Although the core machinery of CG-endocytosis has been defined, no cargo-specific adaptors are known10.

The small GTPase Rab21 binds directly to integrins to regulate endo/exosomal traffic, cytokinesis, chromosome integrity, endosomal signalling and anoikis11–14. Rab21 interacts with integrins independently of its activation state (GDP/GTP); nevertheless, integrin endocytosis requires Rab21 activity, but the exact mechanism is currently unknown11. In addition, very few Rab21 interactors have been identified15.

Here we identify Swiprosin-1 (Swip1, EFHD2) as an interactor of Rab21 and a cargo-specific adaptor for CG-endocytosis.

Results

Swip1 interacts with Rab21 and β1-integrin

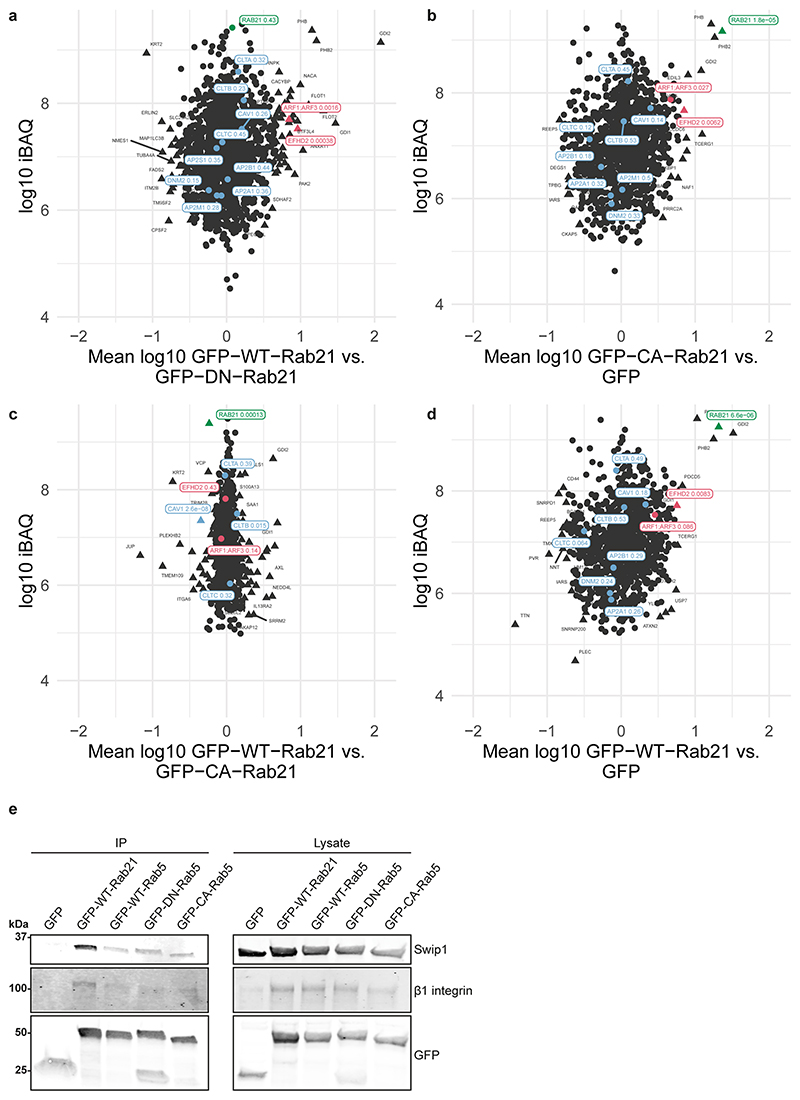

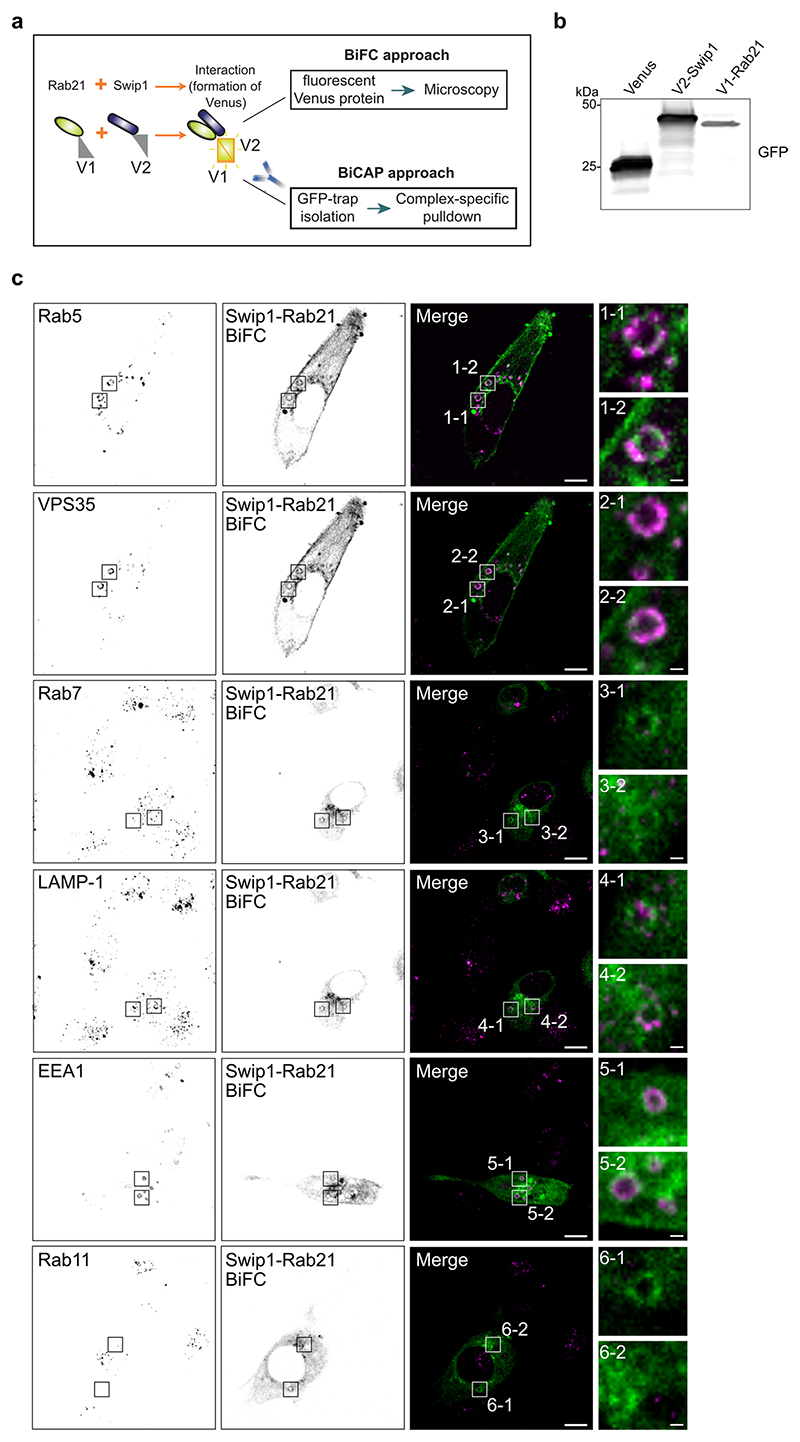

To identify Rab21-interacting proteins, we performed proteomic analyses by stable isotope labelling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) of cells expressing wild-type (WT) Rab21, the constitutively active Rab21Q76L mutant (CA-Rab21) or the Rab21T31N inactive mutant16,17. This mass-spectrometry strategy identified the actin-binding protein Swip1 as a putative active Rab21 interactor (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a–d and Supplementary Table 1). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) pulldowns from the cell lysates demonstrated endogenous Swip1 preferably bound to WT and CA-Rab21, and not to the closely related Rab5 GTPase (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1e). Moreover, purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Swip1 interacted directly with GTP-analogue-loaded recombinant Rab21 (positive control: Rab21–GTP-specific interactor APPL1 (refs. 18,19); Fig. 1c). We next validated the interaction in cells, where Swip1 localized to GFP–Rab21-containing endosomes (Fig. 2a) and a proximity ligation assay (PLA) indicated endogenous Swip1 and Rab21 association in intact cells (Fig. 2b). Rab21 localizes with membrane-proximal puncta and early endosomes positive for endocytosed active β1-integrins11,14,20. Concordantly, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC)21 revealed an interaction between Swip1 and Rab21 in structures overlapping predominantly with EEA1, Rab5 and VPS35, and to a lesser extent with late endosome markers (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). Furthermore, Swip1 localized to Rab21-positive, β1-integrin-containing endosomes (Extended Data Fig. 3a). These data indicate that Swip1 interacts with integrin-associated Rab21 in cells.

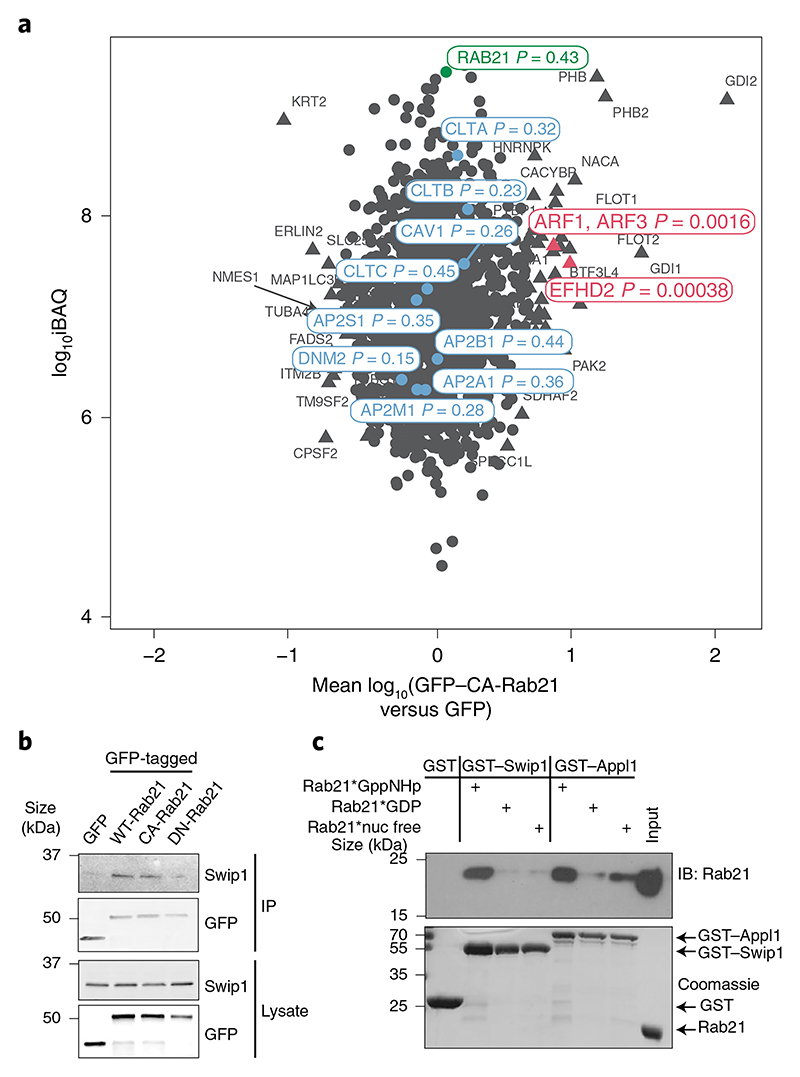

Fig. 1. Swip1 interacts directly with active Rab21.

a, SILAC proteomics analysis of GFP-Trap pulldowns in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing GFP-tagged CA-Rab21 versus GFP alone. The plot is representative of two independent experiments, forward and reverse; the experiments consisted of two independent affinity purifications. The plot shows the mean fold-changes from the forward and reverse experiments against absolute protein abundances (intensity-based absolute quantification, iBAQ). Abundance bins were defined by including 1,000 proteins in a subsequent order. The log10-transformed fold-change values of the proteins were tested for statistical significance using double-sided Significance B tests. No multiple hypothesis correction method was applied due to the small number of selected proteins for the statistical analysis. Proteins with P < 0.01 are represented by a triangle and non-significant proteins are shown as circles. P values are depicted in the figure for a selected set of proteins. The proteins in red are markedly enriched in the CA-Rab21 fraction and proteins in blue are known endosomal proteins—clathrin (CLTA, CLTB and CLTC), AP2 (AP2A1, AP2B1, AP2M1 and AP2S1), caveolin (CAV1) and dynamin II (DNM2)—that are not specifically enriched. b, Representative immunoblots of GFP-Trap pulldowns from MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the indicated constructs and probed for GFP and endogenous Swip1. Three independent experiments were performed. GFP–DN-Rab21, Rab21T33N dominant negative, GDP-bound/nucleotide-free; IP, immunoprecipitation. c, Coomassie-stained gel and immunoblot (IB) of GST-pulldowns with the indicated GST-tagged proteins and recombinant Rab21 (indicated by asterisks) bound to a non-hydrolysable form of GTP (GppNHP; active Rab21), GDP or no nucleotide after EDTA treatment (nuc free). The Rab21-effector GST–APPL1 was used as a positive control. Three independent experiments were performed. Unprocessed blots are provided.

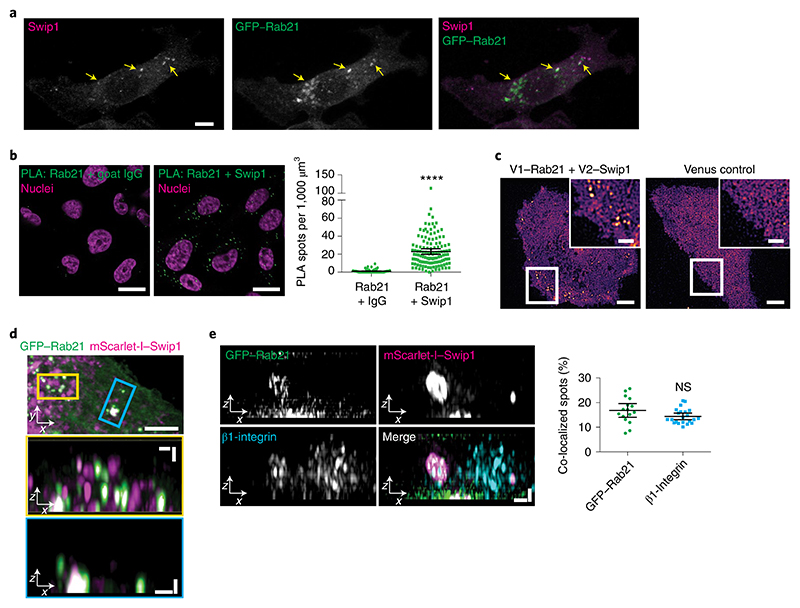

Fig. 2. Swip1 interacts with Rab21 and β1-integrin.

a, Representative MDA-MB-231 cell expressing GFP–Rab21 and immunostained for Swip1. The arrows point to regions of overlap between Swip1 and GFP–Rab21. Scale bar, 10 μm. The micrograph is representative of two independent experiments. b, Endogenous Rab21 and Swip1 are in close proximity in MDA-MB-231 cells. A PLA assay using the indicated antibodies (left) is quantified (right). Goat IgG was included as a negative control and nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bars, 20 μm; n = 121 (Rab21–IgG) and 126 (Swip1–Rab21) cells were examined across three independent experiments. c, Representative TIRF microscopy images of live MDA-MB-231 cells expressing the BiFC constructs V1–Rab21 and V2–Swip1 or Venus alone as a control. Scale bars, 5 μm (main images) and 2 μm (insets). Three independent experiments were performed. d, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and GFP–Rab21 imaged using SIM. The blue and yellow squares highlight the regions of interest (ROI; top) in the x–y plane that are magnified in the x–z projections (middle and bottom; magnified views). Scale bars, 5 μm (top) and 1 μm (middle and bottom). Representative images of three independent experiments are shown. e, SIM x–z projections of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1, GFP–Rab21 and immunostained for β1-integrin (left) were quantified for co-localization with mScarlet-I–Swip1 (right). Each dot represents the co-localization fraction in one cell; n = 16 (GFP–Rab21) and 22 (β1-integrin) cells pooled from two independent experiments. Scale bars, 0.5 μm. b,e, Data are presented as the mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Mann–Whitney test; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. Numerical source data are provided.

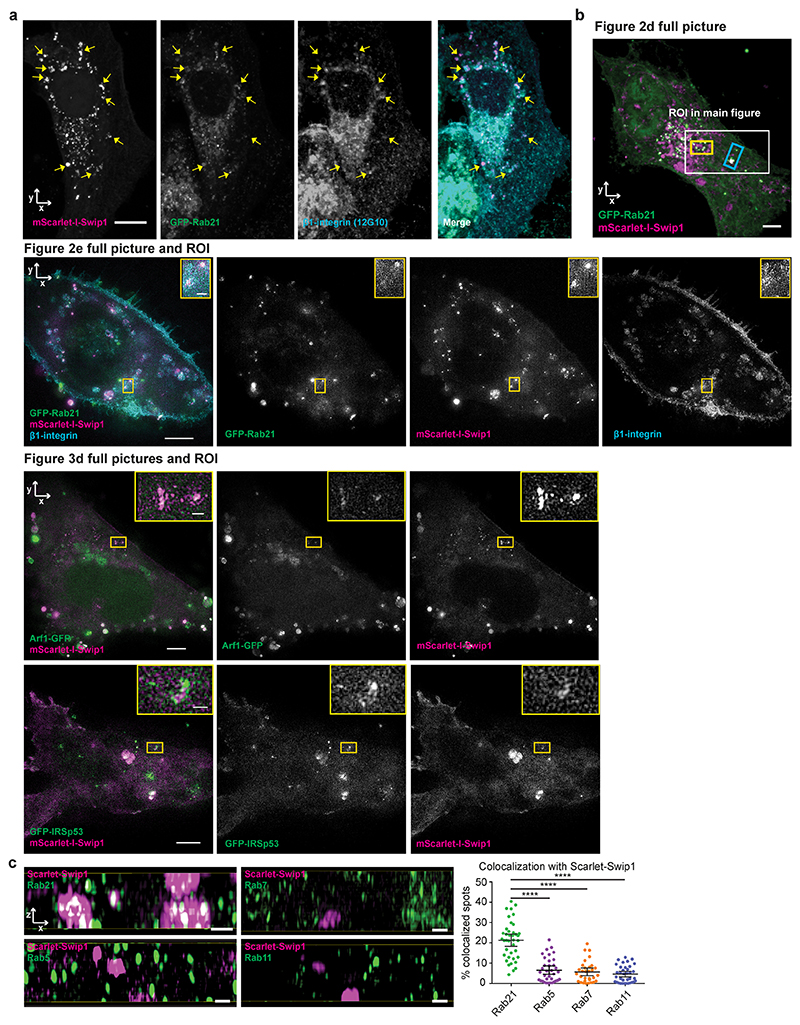

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy of endocytic events on the plasma membrane revealed split Venus-tagged Rab21 and Swip1 (V1–Rab21 and V2–Swip1) complexes moving at the cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interface in live cells9,22 (Fig. 2c). The BiFC interaction puncta were dynamic, detected at the cell periphery and in the cell centre, and absent in the Venus-expressing control cells (Supplementary Video 1). Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) images of the cell–ECM interface revealed that Swip1, Rab21 and β1-integrin-positive structures extended vertically into the cell (Fig. 2d,e, x–z projections and Extended Data Fig. 3b). In these structures, Swip1 co-localized substantially more with Rab21 than Rab5, Rab7 and Rab11 (Extended Data Fig. 3c), indicating a degree of specificity for Rab21 binding. Together, these data identify Swip1 as an interactor of active Rab21, overlapping with β1-integrins in endosomal compartments and in close proximity with the plasma membrane.

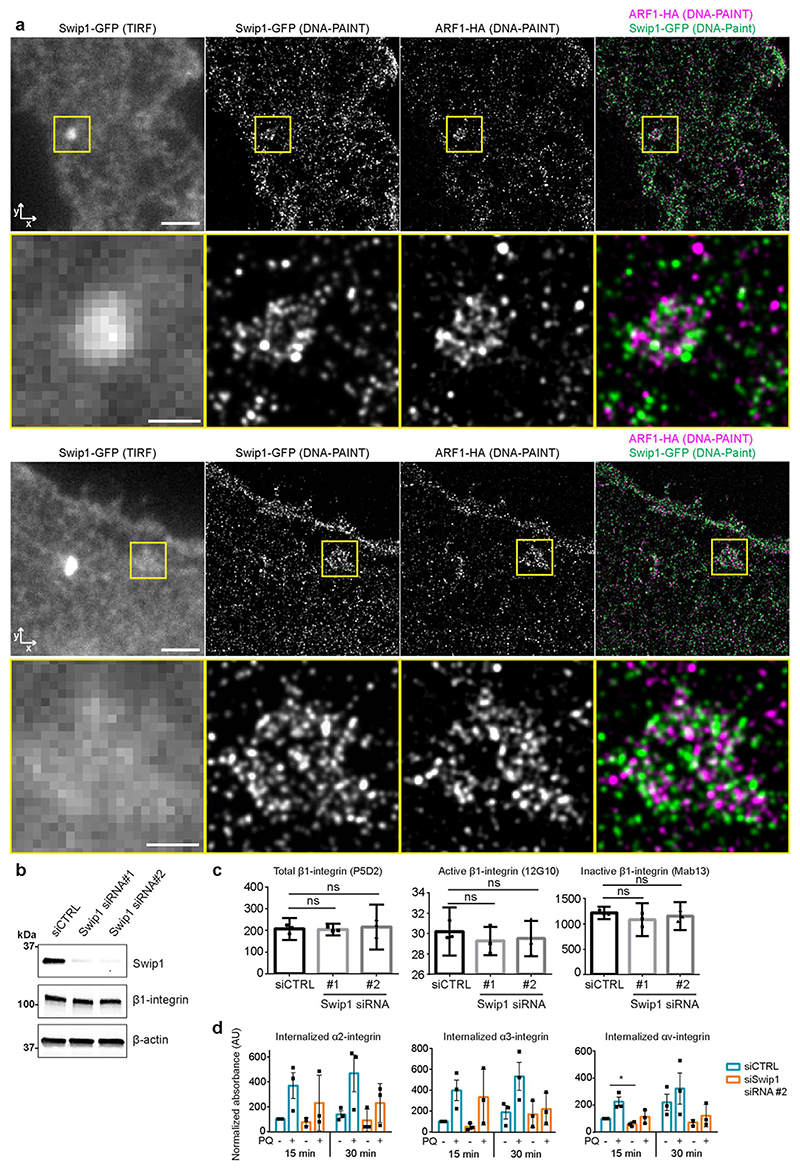

Swip1 associates with CG-pathway components

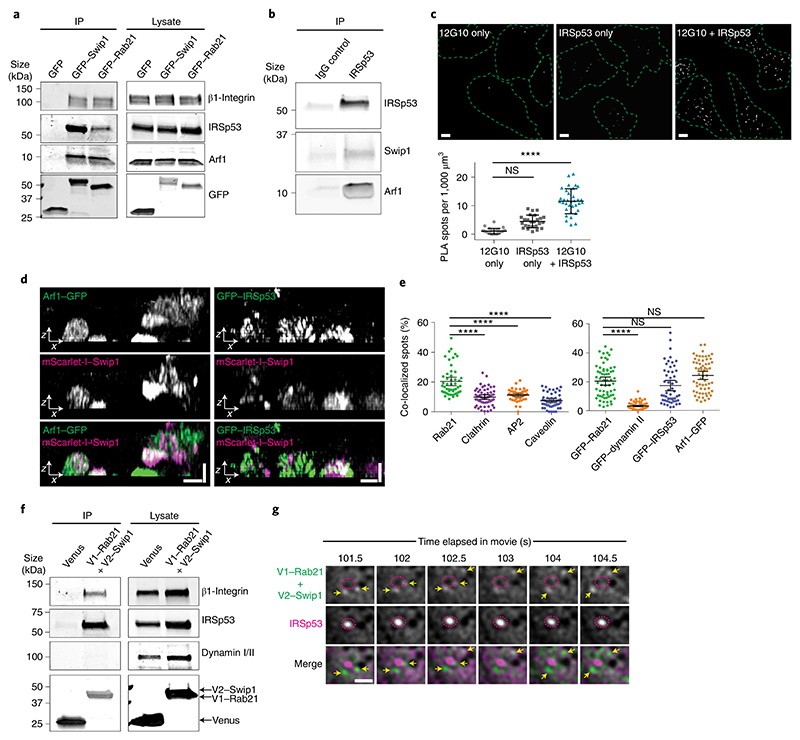

Interestingly, Arf1 was detected as an active Rab21 interactor alongside Swip1 (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a–d), prompting us to test whether Rab21 and/or Swip1 associate with Arf1. Arf1 is a known regulator of CG-endocytosis, where cargo uptake is mediated by tubulovesicular membrane invaginations23. Both GFP–Rab21 and GFP–Swip1 co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous Arf1 (Fig. 3a). In addition, another CG-endocytosis regulator, IRSp53 (ref. 10), was detected in the GFP immunoprecipitations (Fig. 3a), and immunoprecipitation of endogenous IRSp53 co-precipitated endogenous Swip1 and Arf1 (Fig. 3b). Moreover, significant PLA signal between IRSp53 and active β1-integrin (12G10 active-integrin conformation-specific antibody) showed close proximity of the endogenous proteins (Fig. 3c). These data indicate that the Rab21–β1-integrin–Swip1 complex is associated with the CG-endocytosis machinery. To investigate this in more detail, we imaged Swip1 co-localization with known components of CME, caveolin-mediated endocytosis and CG-endocytosis using SIM. Swip1 co-localized significantly more with Rab21, Arf1 and IRSp53 than with clathrin, the clathrin adaptor AP2, caveolin or dynamin II (Fig. 3d,e). These data are consistent with Rab21-mediated integrin endocytosis remaining unaffected by clathrin inhibition12, the clathrin and caveolin endocytic pathway components not being enriched in the active Rab21 mass-spectrometry fractions (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a–d) and the absence of dynamin I/II in bimolecular complementation affinity purified21 V1–Rab21 and V2–Swip1 complexes in cells (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, we detected ring-like structures of GFP–Swip1 co-localizing with haemagglutinin (HA)–Arf1 at the TIRF plane using another super-resolution microscopy technique, DNA-PAINT24 (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Moreover, Rab21–Swip1 BiFC puncta were detected dynamically moving towards IRSp53-positive structures before disappearing from the TIRF plane in live cells (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Video 2). These data indicate the existence of a Swip1–Rab21–GTP complex that links to the CG-endocytosis machinery.

Fig. 3. Swip1 interacts with members of the CG pathway.

a, Representative immunoblots of GFP-Trap pulldowns from HEK293 cells transfected as indicated and blotted for GFP, endogenous IRSp53, Arf1 and β1-integrin. b, Representative immunoprecipitation, with control mouse IgG or anti-IRSp53, of MDA-MB-231 cell lysates probed for endogenous Swip1, IRSp53 and Arf1. c, Proximity ligation assay with the indicated antibodies alone (negative controls) and together to assess co-localization. Scale bars, 10 μm; n = 12 (12G10 only), 18 (IRSp53 only) and 28 (12G10 + IRSp53) cells analysed across two independent experiments. d, Representative SIM x–z projections of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and GFP–IRSp53 or GFP–Arf1. Scale bars, 0.8 μm. Three independent experiments were performed. e, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and immunostained for endocytic adaptor proteins (left) or transfected with the indicated GFP-tagged constructs (right) were imaged with SIM and quantified for co-localization with mScarlet-I–Swip1. Each dot represents the co-localization fraction in one cell; n = 50 (Rab21, AP2 and caveolin), 55 (clathrin), 63 (GFP–Rab21 and GFP–dynamin II), 53 (GFP–IRSp53) and 62 (GFP–Arf1) cells analysed, pooled from three independent experiments. c,e, Data are the mean ± 95% CI. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Mann–Whitney test; ****P < 0.0001. f, Representative immunoblots of bimolecular complementation affinity purification pulldowns from MDA-MB-231 cells transiently transfected as indicated and blotted for GFP/Venus, endogenous IRSp53, dynamin I/II and β1-integrin. The GFP antibody recognizes both V1–Rab21 and V2–Swip1 (see also Extended Data Fig. 2b). a,b,f, Two independent experiments were performed. g, Representative TIRF microscopy BiFC images of live MDA-MB-231 cells expressing V1–Rab21 + V2–Swip1 and mCherry–IRSp53. The yellow arrows point to V1–Rab21 + V2–Swip1 puncta that travel towards mCherry–IRSp53 puncta (pink dashed circles) and then disappear from the TIRF plane. Scale bar, 1 μm. Representative images of two independent experiments are shown. IP, immunoprecipitation. Unprocessed blots and numerical source data are provided.

Active β1-integrin endocytosis via Swip1 is Rab21 dependent

We next investigated the requirement for Swip1 for integrin endocytosis. Silencing of Swip1 decreased the uptake of cell surface-labelled active β1-integrin in MDA-MB-231 cells. Swip1 silencing-induced inhibition of integrin endocytosis was apparent at the 5 min time point and persisted for up to 30 min (Fig. 4a). Ectopic expression of RNA interference-resistant GFP–Swip1 rescued β1-integrin endocytosis in Swip1-silenced cells and increased the uptake in control short interfering RNA (siRNA)-transfected cells (Fig. 4b). Reduced integrin uptake was specifically due to Swip1 silencing and not lower integrin levels, as evidenced by the total β1-integrin protein levels remaining unaffected by Swip1 silencing along with the surface levels of total, active and inactive β1-integrins (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). We then investigated whether the Swip1–Rab21 complex could discriminate between active and inactive β1-integrins. Internalization of inactive β1-integrin (Mab13 antibody) was unaffected by Swip1 or Rab21 silencing (Fig. 4c). These data are in line with previous reports of active β1-integrins signalling from Rab21 endosomes14 and the Rab21–integrin interaction requiring the conserved KR-residues within the integrin α-subunit cytoplasmic-tail GFFKR motif11. Thus, this process potentially interferes with conserved salt-bridge interactions (between α-subunit R and the conserved acidic residue of the β-cytoplasmic domain) known to stabilize integrins in their inactive conformation25.

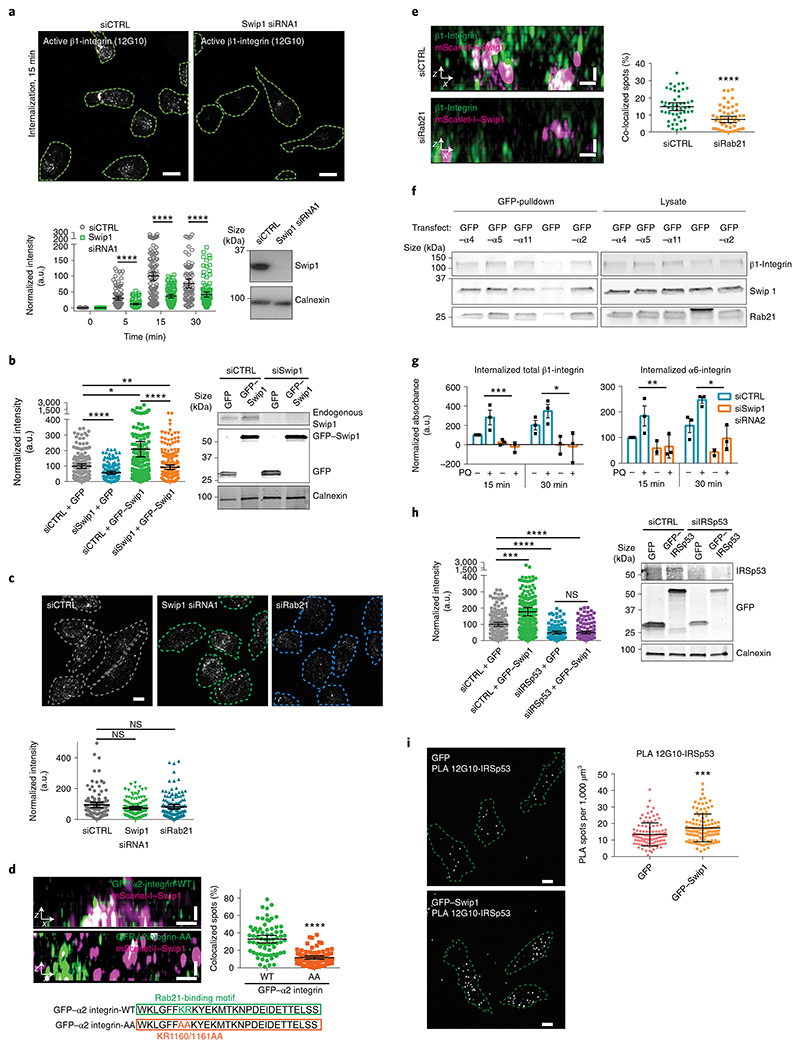

Fig. 4. Swip1 mediates the endocytosis of active integrins via the CG pathway.

a, Representative micrographs of active β1-integrin internalization in control (siCTRL)- and Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells (top; green dashed lines show the outlines of the cells defined by phalloidin labelling), and levels of internalized β1-integrin at the indicated times (bottom left). Representative immunoblot to validate Swip1 silencing (bottom right). Scale bars, 30 μm; siCTRL, n = 86, 101, 110 and 78 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 104, 98, 102 and 106 cells, from left to right. b, Levels of active β1-integrin internalization at 15 min in siCTRL- or Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells expressing GFP or GFP–Swip1 (left). Representative immunoblots of cell lysates probed as indicated (right); siCTRL + GFP, n = 153 cells; siCTRL + GFP–Swip1, n = 186 cells; siSwip1 + GFP, n = 136 and siSwip1 + GFP–Swip1, n = 196 cells. *P = 0.0275 and **P = 0.0260. c, Representative micrographs (top) and levels of inactive β1-integrin (Mab13) internalization at 15 min in siCTRL-, Swip1- and Rab21-silenced (siRab21) MDA-MB-231 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm; siCTRL, n = 107 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 116 cells; and siRab21, n = 122 cells. d, SIM x–z projections of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and GFP-tagged α2-integrin-WT or mutant α2 integrin-AA (top left). The integrin cytoplasmic sequence and mutated residues (red) are depicted (bottom). Levels of co-localization of GFP-tagged proteins with mScarlet-I–Swip1 (right). Mutant α2 integrin-AA, n = 76 cells; and α2 integrin-WT, n = 70. e, SIM x–z projections of siCTRL- or Rab21-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and immunostained for β1-integrin (P5D2; left). Levels of co-localization between mScarlet-I–Swip1 and β1 integrin (right). siCTRL, n = 50 cells; and siRab21, n = 56 cells. d,e, Scale bars, 0.5 μm. f, Representative immunoblots of three independent GFP-Trap pulldowns from MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with different GFP-tagged integrin α-subunits and blotted as indicated. g, Levels of cell-surface biotinylated β1-integrin (left) and α6-integrin internalization (right) in Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells after the indicated times in the presence or absence of 100 μM primaquine (PQ). The bar charts show the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using multiple-comparison t-tests for paired data, with the post-hoc Holm–Sidak method; α = 5.000%. For β1-integrin (left), ***P = 0.00934 and *P = 0.02015; for α6-integrin, *P = 0.02196 and **P = 0.04683 Three independent experiments were performed. h, Level of β1-integrin internalization in siCTRL- and IRSp53-silenced (siIRSp53) MDA-MB-231 cells expressing GFP or GFP–Swip1 (left). Representative immunoblots of cell lysates probed as indicated (right); siCTRL + GFP, n = 157 cells; siCTRL + GFP–Swip1, n = 289 cells; siIRSp53 + GFP, n = 108 and siIRSp53 + GFP–Swip1, n = 136 cells. ***P = 0.0003. i, Representative micrographs (left) and quantification of PLA with the indicated antibodies in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing GFP or GFP–Swip1. Scale bars, 10 μm; GFP, n = 106 and GFP–Swip1, n = 111 cells. ***P = 0.0001 a–e,h,i, The scatter dot plots show data as the mean ± 95% CI. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney tests; n is the total number of cells pooled from three independent experiments. a–e,h, ****P < 0.0001; a.u., arbitrary units. Unprocessed blots and numerical source data are provided.

To assess the impact of Rab21 in the Swip1-mediated recruitment of integrins, we mutated the key Rab21-interacting residues (KR1160/1161AA) in the integrin α2-subunit11,14. This significantly reduced integrin co-localization with Swip1-positive structures (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, co-localization of β1-integrin with Swip1 was reduced in Rab21-silenced cells (Fig. 4e), indicating that a preserved integrin–Rab21 interaction is required for the Swip1-mediated recruitment of the integrin receptor. In line with Rab21 interacting with multiple integrin α-subunits11, we found that Swip1 and Rab21 co-precipitated with several distinct GFP-tagged integrin α-subunits (Fig. 4f). Importantly, Swip1 silencing decreased the internalization of β1-integrin and several different α-subunits (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 4d). Inhibition of receptor recycling with primaquine further amplified the difference in integrin internalization between control- and Swip1-silenced cells (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 4d). This indicates that Swip1 regulates integrin traffic at the step of internalization, where it specifically regulates endocytosis of Rab21-bound active integrins.

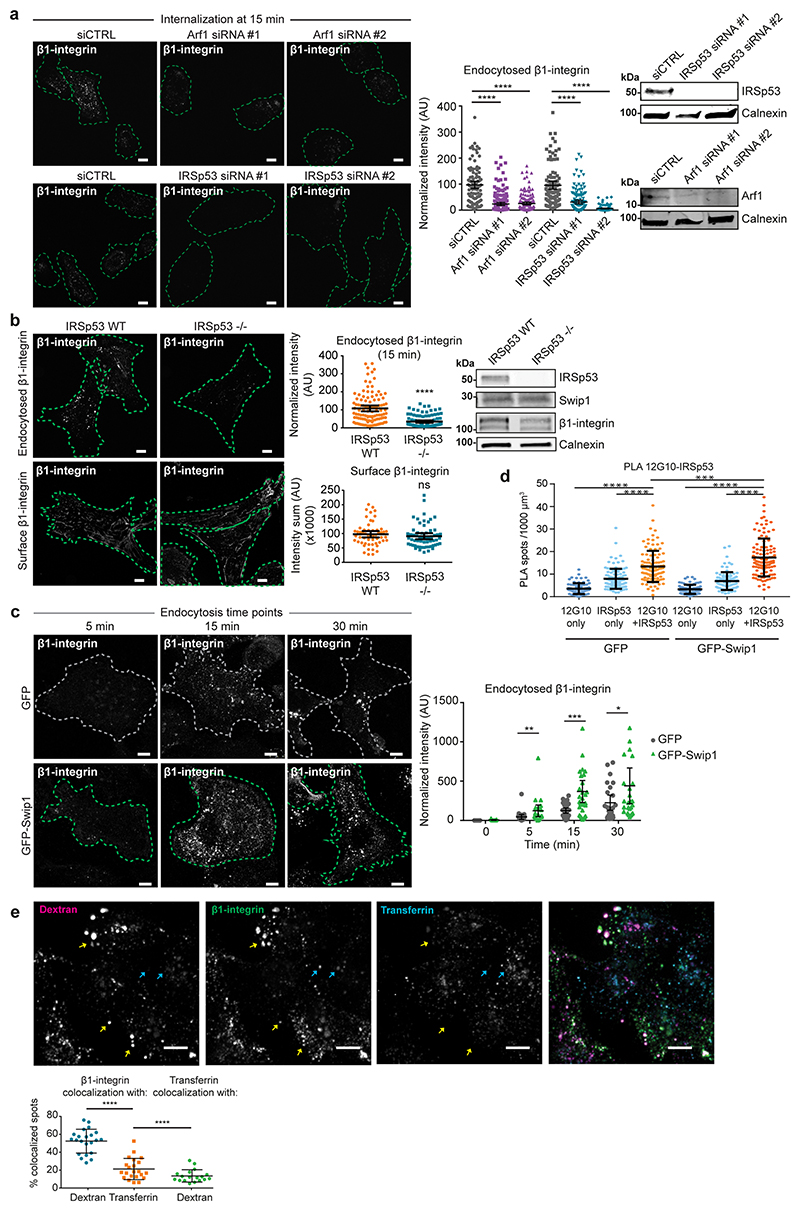

Swip1 regulates integrin uptake via the CG pathway

To explore the role of the CG pathway in Swip1-mediated endocytosis, we silenced Arf1 and IRSp53, both essential members of the CG pathway, with two independent siRNAs. This markedly decreased β1-integrin endocytosis in MDA-MB-231 cells (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Furthermore, integrin endocytosis was impaired in IRSp53-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Extended Data Fig. 5b). This was specifically due to reduced integrin uptake and not lower integrin levels, given that the levels of total integrin were unaffected by the loss of IRSp53 (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Overexpression of ectopic GFP–Swip1 clearly increased integrin uptake (Extended Data Fig. 5c). This was dependent on the CG-pathway machinery, as depletion of IRSp53 abolished GFP–Swip1 overexpression-induced β1-integrin endocytosis (Fig. 4h). The ability of ectopic Swip1 to augment β1-integrin endocytosis was most probably due to the Swip1 overexpression-augmented recruitment of β1-integrins to IRSp53 (Fig. 4i and Extended Data Fig. 5d). Together, these data link Swip1 with β1-integrin endocytosis by the CG pathway under basal conditions.

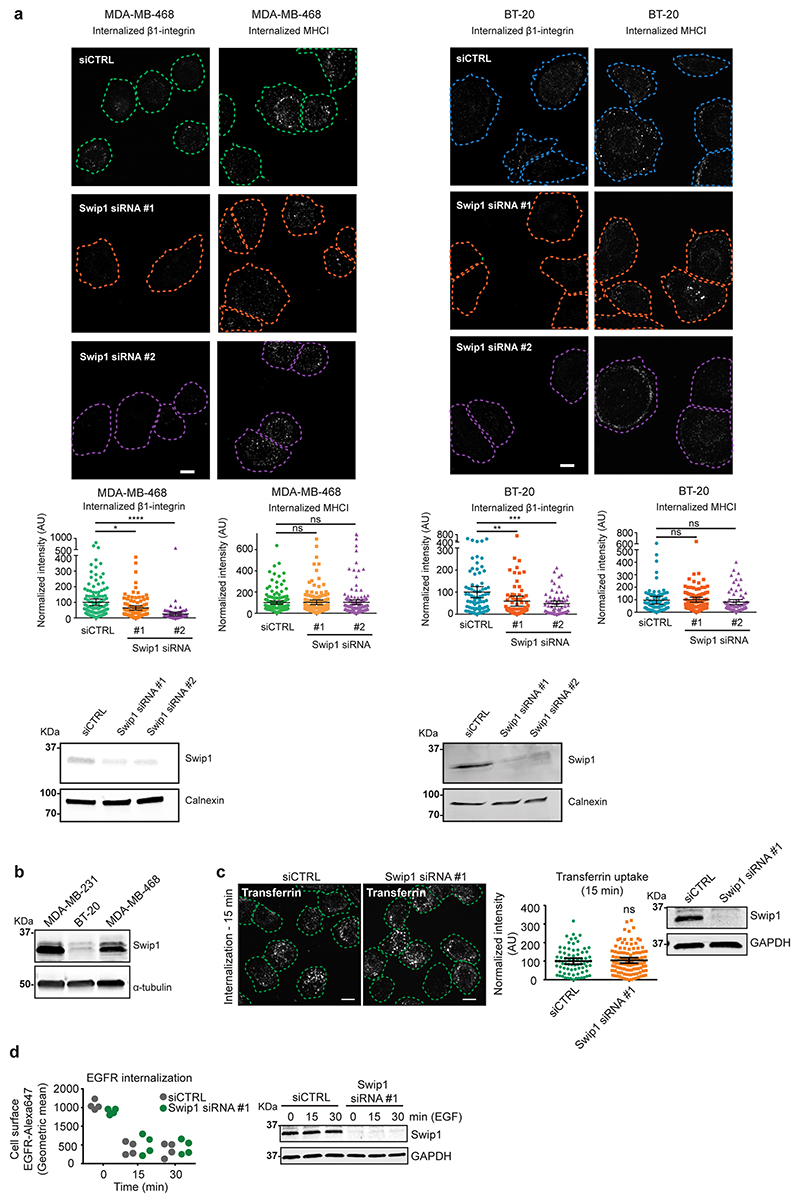

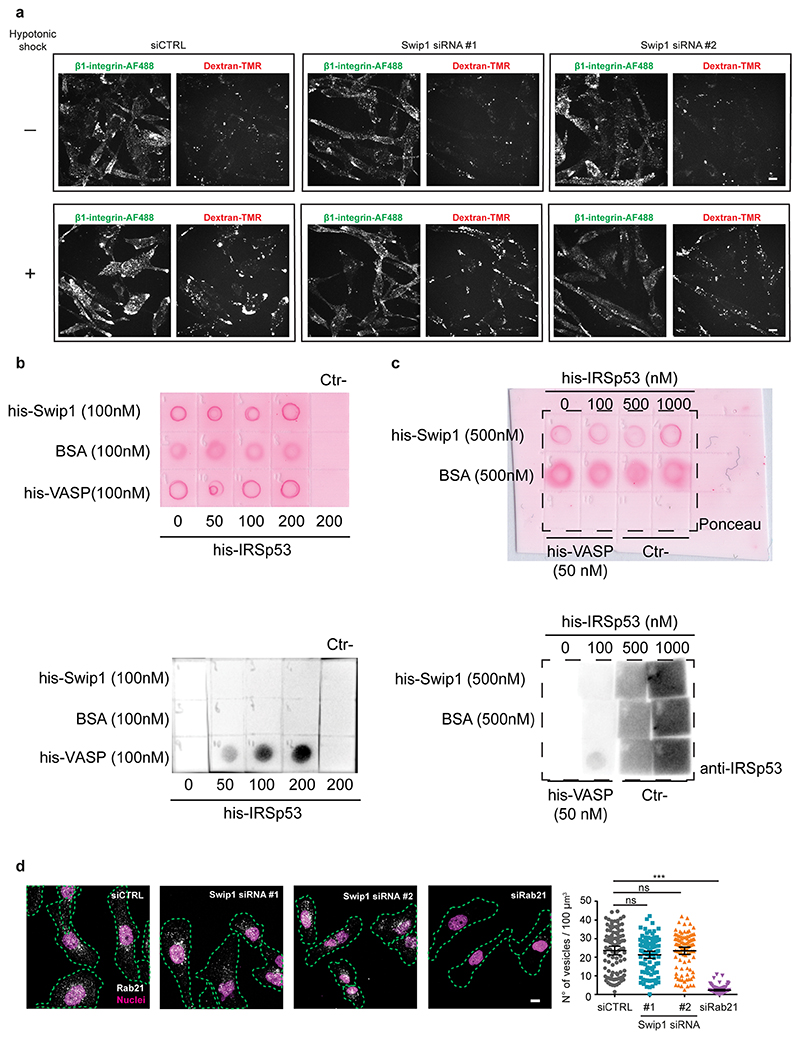

Swip1 is a cargo adaptor for the CG pathway

CG-endocytosis is the major route for the bulk uptake/internalization of different kinds of cargo5, whereas Rab21 has been primarily linked to integrin internalization11. To explore the possibility that β1-integrins enter the CG pathway, we imaged the uptake of plasma membrane-labelled active β1-integrin with 10 kDa dextran; a fluid-phase cargo for the CG pathway. Immediately after endocytosis (2 and 5 min), integrins and dextran co-localized as clearly as dextran labelled with two different dyes (Fig. 5a). Moreover, a large proportion of active β1-integrin (around 50%) co-localized with endocytosed dextran, while around 20% co-localized with transferrin (Extended Data Fig. 5e), indicating that both the CME and CG pathways are active and facilitate the uptake of active integrins. To assess whether Swip1 is a cargo adaptor or an integral member of the CG pathway, we investigated whether it regulates the endocytosis of other CG cargos. Swip1 silencing had no effect on the uptake of 10 kDa dextran or major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI; Fig. 5b,c). In contrast, silencing of IRSp53 significantly impaired endocytosis of both cargos, thereby validating the approach. Similar data were obtained in two additional triple-negative breast adenocarcinoma (TNBC) cell lines, MDA-MB-468 and BT-20, where Swip1 silencing significantly reduced β1-integrin uptake but not MHCI uptake (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 6a). The effect on β1-integrin endocytosis was more prominent in the MDA-MB-468 cells, which express higher levels of endogenous Swip1 than the BT-20 cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Furthermore, Swip1 depletion did not affect the endocytosis of transferrin or EGFR (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d), which are internalized through CME or dynamin-dependent non-clathrin endocytosis26,27. Thus, Swip1 regulates endocytosis of β1-integrin, but not of other CG cargos, which is indicative of a role for Swip1 as an integrin-specific CG-cargo adaptor.

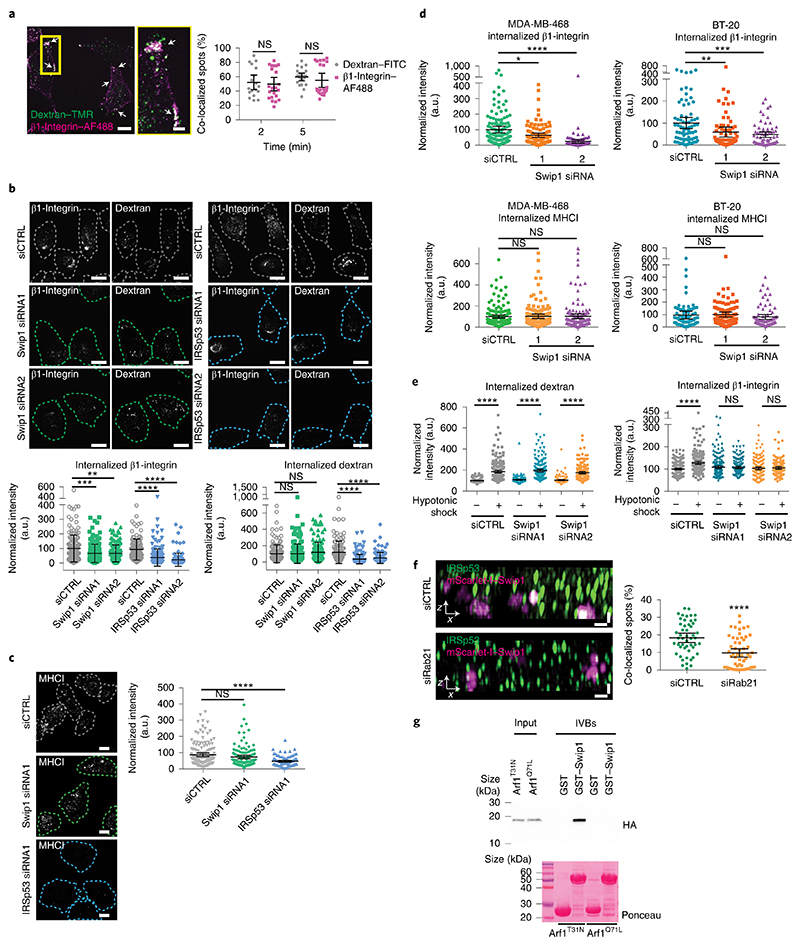

Fig. 5. Swip1 is a cargo adaptor for the CG pathway.

a, Double uptake (indicated by arrows) of fluorescently labelled 10 kDa dextran–tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated dextran or Alexa Fluor (AF) 488-conjugated anti-β1-integrin antibody (12G10, β1-integrin–AF488) in MDA-MB-231 cells for the indicated times (right). Representative images at 5 min internalization are shown (left). Scale bars, 10 μm (main image) and 3 μm (inset, magnified view of the yellow box in the main image). Dextran–FITC, n = 18 and 21 cells; and β1-integrin–A488, n = 22 and 21 cells. b, Representative micrographs (top), and levels of dextran–TMR (bottom right) and β1-integrin–AF488 (bottom left) internalization in control-, Swip1- and IRSp53-silenced MDA-MB-231 at 15 min. Swip1 siRNA1, n = 157 cells; Swip1 siRNA2 and siCTRL, n = 160 cells; siCTRL, n = 121 cells; IRSp53 siRNA1, n = 177 cells; and IRSp53 siRNA2, n = 121 cells. ***P = 0.0001 and **P = 0.0004. c, Representative micrographs (left) and levels of MHCI internalization in control-, Swip1- and IRSp53-silenced MDA-MB-231 at 15 min (right). Swip1 siRNA1, n = 125 cells; IRSp53 siRNA1, n = 92 cells; and siCTRL, n = 152 cells. b,c, Dashed lines show the outlines of the cells defined by labelling with the plasma membrane marker WGA lectin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (WGA–AF647). Scale bars, 10 μm. d, Levels of β1-integrin (top) and MHCI (bottom) internalization in control- or Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-468 (left) and BT-20 (right) cells at 15 min. For BT-20 12G10 and MHCI uptake, respectively, siCTRL, n = 79 and 91 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 76 and 91 cells; and Swip1 siRNA2, n = 66 and 75 cells. For MDA-MB-468 12G10 and MHCI uptake, respectively, siCTRL, n = 134 and 155 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 98 cells and 156 cells; and Swip1 siRNA2, n = 98 cells and 135 cells. *P = 0.0137, **P = 0.0007 and ***P = 0.0006. e, Levels of β1-integrin–AF488 (right) and 10 kDa dextran–TMR (left) uptake in steady state or after recovery from hypotonic shock in control- and Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells. For dextran uptake in the absence of (−) or with (+) hypotonic shock, respectively: siCTRL, n = 227 and 220 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 208 and 186 cells; and Swip1 siRNA2, n = 208 and 187 cells. For β1-integrin uptake in the absence of (−) or with (+) hypotonic shock, respectively: siCTRL, n = 195 and 191 cells; Swip1 siRNA1, n = 208 and 181 cells; and Swip1 siRNA2, n = 181 and 139 cells. f, SIM x–z projections of control- and Rab21-silenced (siRab21) MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and immunostained for IRSp53 (left). Co-localization between mScarlet-I–Swip1 and endogenous IRSp53 was quantified (right); siCTRL, n = 50 cells; and siRab21, n = 56 cells. Scale bars, 0.5 μm. g, Cell lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with HA–Arf1T31N (inactive) or HA–Arf1Q71L (active) were incubated with 2 μM of recombinant purified GST or GST–Swip1. Representative GST pulldowns (IVBs) stained with Ponceau and blotted with the indicated antibody from three independent experiments. a–f, Data are the mean ± 95% CI; n is the total number of cells pooled from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney tests; ****P < 0.0001. Unprocessed blots and numerical source data are provided.

The CG pathway responds specifically to transient changes in the cell-membrane tension. The constitutive activity of the pathway is augmented following a strain relaxation, such as moving cells from hypotonic to isotonic medium, leading to a decrease in membrane tension28. Treatment of cells with hypotonic medium, followed by a shift to isotonic medium, notably increased the uptake of 10 kDa dextran and β1-integrin compared with the cells in isotonic medium. Although dextran uptake was similarly elevated in control- and Swip1-silenced cells, when the cells were moved from hypotonic to isotonic medium, the β1-integrin uptake did not increase in the Swip1-silenced cells following this treatment, in line with the idea of Swip1 specifically facilitating β1-integrin uptake through the CG pathway (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 7a). This observation further confirmed β1-integrin as a Swip1 recruited cargo for the CG pathway.

Swip1 and Arf1 direct integrin cargo towards CG-endocytosis

To investigate the mechanism through which Swip1 provides cargo specificity to the CG pathway, we silenced Rab21 and assessed the co-localization of the CG-pathway component IRSp53. After Rab21 silencing, co-localization of IRSp53 with Swip1 was significantly reduced, indicating that recruitment of Swip1 to the CG pathway is dependent on binding to Rab21 and β1-integrin (Fig. 5f). Swip1 did not interact with IRSp53 directly, while IRSp53 still associated with VASP, a known IRSp53 interactor29–31 (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). We then explored the possible link between Swip1 and Arf1. Unexpectedly, we found that Swip1 associates preferentially and specifically with the inactive Arf1mutant (Arf1T31N) but not the active Arf1 (Arf1Q71L; Fig. 5g). Arf1 localization at the plasma membrane precedes the formation of CG-endocytic tubules and its activation is required for CG-endocytosis9,32. Given that Swip1 neither activates the CG pathway nor an integral part of it, we propose a model where Swip1 targets Rab21-bound integrins to the CG pathway as a pre-assembled module with inactive Arf1, which is then recruited to the endocytic CG machinery.

Cumulatively, these data imply that Swip1 specifically directs integrin cargo towards CG-endocytosis rather than affecting the overall activity of this pathway. These data help to explain the long-standing conundrum whereby active Rab21 is required for integrin endocytosis yet binds integrins in both GDP- and GTP-bound states11. Here we show that Swip1 interacts specifically with Rab21–GTP, coupling active Rab21 and integrin cargo to CG-endocytosis.

CG-pathway integrin trafficking requires Swip1–actin binding

A common emerging theme among non-clathrin endocytosis is the reliance on the actin cytoskeleton33. Intrigued by the established actin-binding activity of Swip1 (ref. 34), we investigated whether this function was important for Swip1-mediated integrin CG-endocytosis. Deletion of the first EF-hand domain (EF1) rendered Swip1 unable to bind actin, concordant with a previous report34, and abolished its ability to facilitate integrin endocytosis (Fig. 6a–c). In contrast, EF2 deletion had no significant effect on Swip1-induced integrin uptake. This indicates that binding of Swip1 to actin is necessary for its ability to induce integrin endocytosis. SIM imaging revealed F-actin overlap with Swip1 and β1-integrin close to the cell–ECM interface (Fig. 6d), indicating that Swip1 and the actin cytoskeleton are in close proximity during integrin endocytosis.

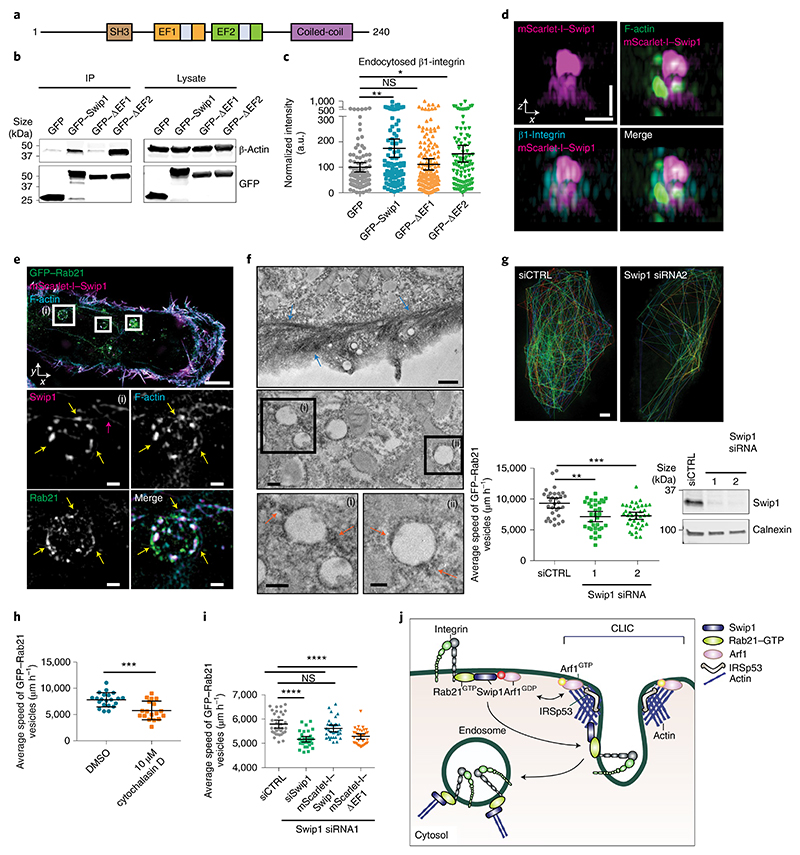

Fig. 6. Swip1–actin binding regulates integrin traffic.

a, Swip1 domains. EF, EF-hand domain containing a calcium-binding site (shown in grey); SH3, SRC homology 3 domain. b, Representative GFP-pulldowns of two independent experiments in HEK293 cells expressing GFP, GFP–Swip1 or truncated versions of Swip1 and blotted as indicated. IP, immunoprecipitation. c, Levels of β1-integrin uptake at 15 min in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing the indicated proteins. **P = 0.0034 and *P = 0.0356; n = 92 (GFP), 94 (GFP–Swip1), 161 (GFP–ΔEF1) and 101 (GFP–ΔEF2) cells. d, Representative SIM x–z projections of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1, immunostained for β1-integrin and labelled with phalloidin. Two independent experiments were performed. Scale bars, 0.7 μm. e, Representative SIM x–y image of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 and GFP–Rab21 and labelled with phalloidin. The white squares highlight ROIs. The yellow arrows point to Swip1 overlap with actin on Rab21-containing vesicles. The pink arrow indicates actin filaments in close proximity to the vesicle. Scale bars, 5 μm (main image) and 0.5 μm (magnified views of (i); bottom). f, Electron microscopy images of GFP–Swip1 visualized using GBP-APEX. ROI (i) and (ii) are magnified (bottom). The arrows point to Swip1–APEX-positive patches adjacent to filament-like actin structures (blue) or vesicles (orange). Scale bars, 0.5 μm (top), 0.2 μm (middle and bottom left, magnified view of (i)) and 0.1 μm (bottom right, magnified view of (ii)). g, Average speed of Rab21 vesicles for each cell close to the TIRF plane over 2 min (bottom left). Representative tracks of Rab21 vesicles in a control or a Swip1-silenced cell (top) and representative immunoblot validating Swip1 silencing (bottom right). Scale bar, 5 μm; **P = 0.0005 and ***P = 0.0003; n = 31 (siCTRL), 33 (siSwip1 siRNA1) and 39 (siSwip1 siRNA2) cells. h, Average speed of Rab21-vesicle movement for each cell following treatment with cytochalasin D. ***P = 0.0007; n = 21 (DMSO) and 18 (cytochalasin D) cells. i, Average speed of Rab21-vesicle movement for each cell following Swip1 silencing and rescue with mScarlet-I–Swip1 or mScarlet-I–ΔEF1. ****P < 0.0001; n = 33 cells per condition. j, Swip1 directs integrins to CG-endocytosis. c,g–i, Data are the mean ± 95% CI; n is the total number of cells pooled from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney tests. Unprocessed blots and numerical source data are provided.

In addition to Swip1 localization to cell–ECM-proximal structures, we observed Swip1 deeper in the cell, where it overlapped with Rab21-positive endosome-like vesicles (Fig. 6e) and F-actin in discrete puncta around Rab21 vesicles (Fig. 6e, yellow arrows, and Supplementary Video 3). Similar localization was visualized using GBP-APEX (GFP-binding protein soybean ascorbate peroxidase)-labelled GFP–Swip1 imaged with electron microscopy (Fig. 6f)35. Swip1 localized to filaments close to the plasma membrane and in the vicinity of endosomes (Fig. 6e,f, pink arrow and blue arrows, respectively). Swip1 localization with actin on Rab21 endosomes prompted us to investigate whether Swip1 regulates the movement of endosomes. Silencing of Swip1 notably reduced the speed of GFP–Rab21 vesicles, but not the number of vesicles (Extended Data Fig. 7d), and restricted their subcellular distribution to the cell periphery (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Videos 4,5). The motility of Rab21 vesicles was actin-dependent, as the actin inhibitor cytochalasin D reduced the vesicle speed (Fig. 6h), consistent with previous observations11. Furthermore, re-expression of WT Swip1, but not the actin binding-deficient EF1-deleted Swip1, fully restored the vesicle speed (Fig. 6i and Extended Data Fig. 8a). Together, these data highlight a role for actin in both Swip1/Rab21-dependent integrin CG-endocytosis and Rab21-mediated integrin endosomal traffic in the cell (Fig. 6j).

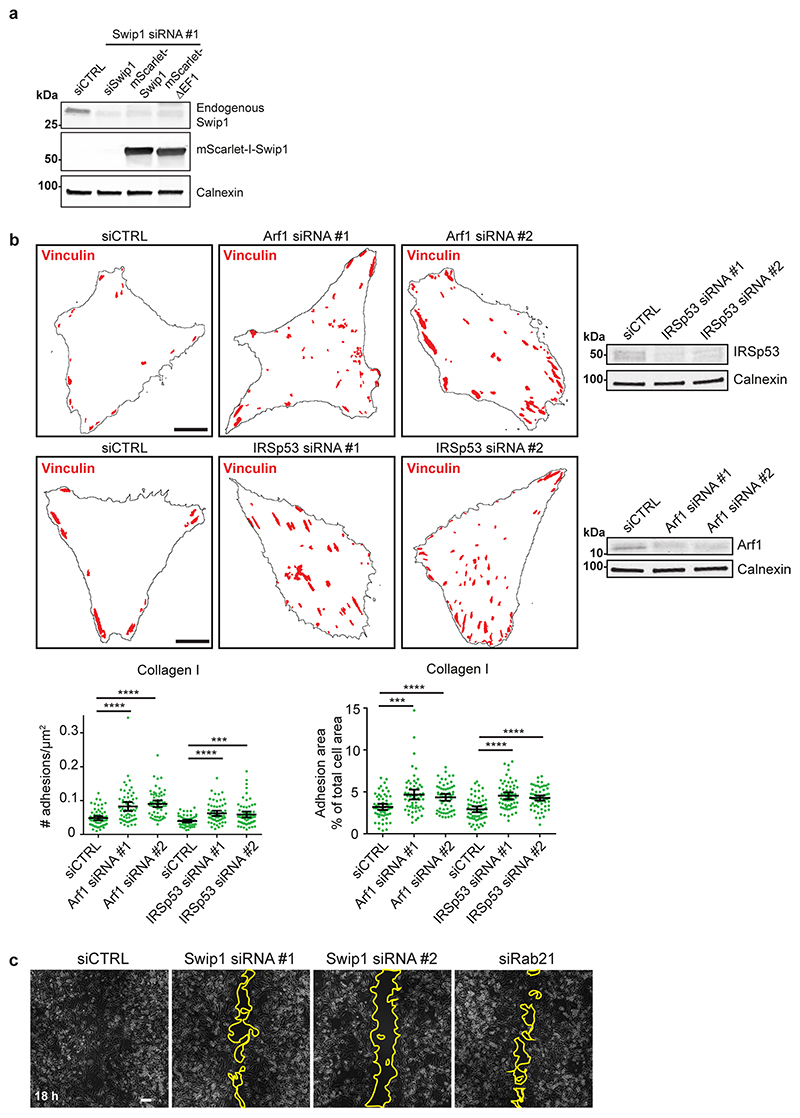

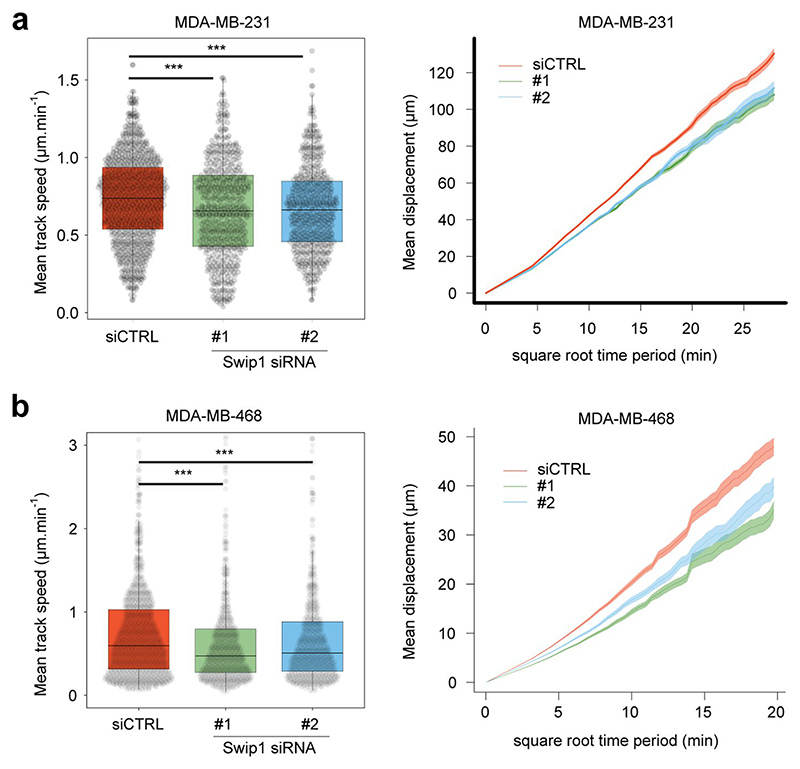

Swip1 regulates adhesion turnover, migration and invasion

Integrin endocytosis and intracellular transport are crucial for integrin turnover, cell migration and invasion15,36. Concordant with this idea, we found that vinculin-containing focal adhesions accumulated in Swip1-silenced cells on collagen I-, fibronectin- and laminin-coated surfaces (Fig. 7a). This phenotype was also present in cells silenced for Arf1 or IRSp53 (Extended Data Fig. 8b), indicating that CG-endocytosis of integrins may regulate adhesion dynamics and cell motility. Using live-cell imaging of paxillin-positive focal adhesions, we observed clearly slower rates of adhesion assembly and disassembly in Swip1-silenced cells compared with the control cells (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, live imaging of BiFC Swip1–Rab21 complexes and paxillin revealed significant enrichment of BiFC signal in close proximity to focal adhesions, indicating that, at the ventral surface of the cell, the Swip1–Rab21 interaction occurs preferentially in the vicinity of adhesion sites (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Video 6). Swip1 regulation of focal adhesions correlated with notably impaired cell migration (Fig. 7d and Extended Data Fig. 8c), in line with previously reported migration defects of IRSp53-null fibroblasts31. Swip1 silencing also inhibited the migration speed of randomly migrating MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9) as well as the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells through a three-dimensional collagen matrix (Fig. 7e). These data indicate that Swip1 supports integrin adhesion dynamics, in concert with the migration and invasion of TNBC cells.

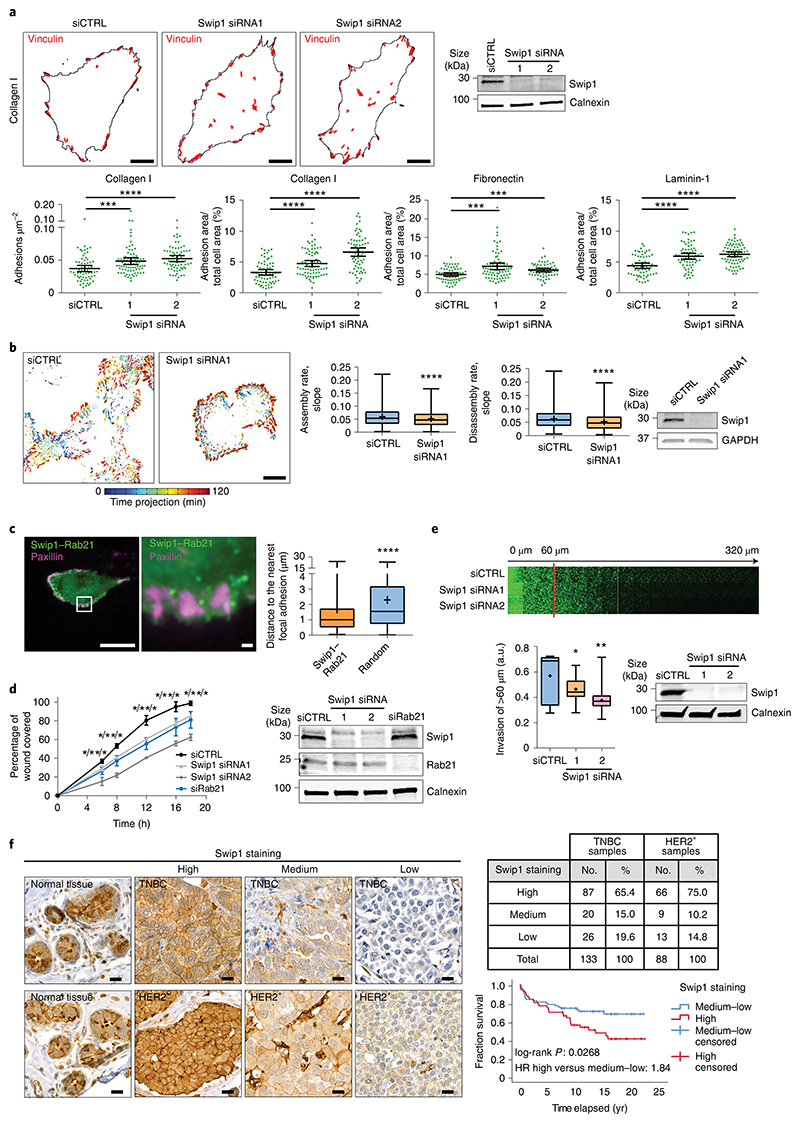

Fig. 7. Swip1 regulates adhesion dynamics, cell motility and breast cancer progression.

a, Representative masks of vinculin-containing focal adhesions in control- or Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells on collagen I (top). Analysis of the number of adhesions and total adhesion area per cell on different ECM components (bottom). Scale bars, 10 μm; data are the mean ± 95% CI. Collagen I, n = 65, 76 and 67 cells; fibronectin, n = 65, 75 and 62 cells; and laminin-1, n = 62, 66 and 73 cells for siCTRL, siSwip1 siRNA1 and siRNA2, respectively. Collagen, ****P < 0.0001 and ***P = 0.0005; fibronectin, ***P = 0.0002 (Swip1 siRNA1) and 0.0007 (siRNA2); laminin-1, ****P < 0.0001. b, Visualization of the GFP–paxillin dynamics in control- and Swip1-silenced cells (left). The colour scale represents the focal adhesion localization over time. The assembly and disassembly rates are shown (middle). Scale bar, 10 μm; siCTRL, n = 861 and 764 adhesions; and siSwip1, n = 1,014 and 1,024 adhesions for assembly and disassembly, respectively; n = 18 cells were analysed per condition. c, Representative TIRF microscopy BiFC images of live MDA-MB-231 cells expressing V1–Rab21, V2–Swip1 and mKate2–paxillin (left). Distance between Swip1–Rab21 puncta or randomly distributed puncta and the closest paxillin-positive focal adhesions (right). Scale bars, 25 μm (main image) and 1 μm (magnified view of the white box); n = 697 (BiFC) and 1,364 (randomly distributed) puncta; n = 20 cells per condition. b,c, ****P < 0.0001. d, Migration of control-, Swip1- or Rab21-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells. Wound-area coverage over time (left). Data are the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using multiple-comparison t-tests with the post-hoc Holm–Sidak method; siSwip1 siRNA1, *P = 0.022118, 0.00148533, 0.00320197, 0.00598189 and 0.00156902; siSwip1 siRNA2, **P = 0.00161506, 8.929064 × 10−5, 0.000190115, 0.000316543 and 0.000100846; and siRab21, *P = 0.0158582, 0.0101405, 0.00574356, 0.0240206 and 0.0286109 for 8, 12, 16 and 18 h, respectively, for comparisons with the siCTRL condition. e, Representative micrographs of control- and Swip1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells that invaded through fibrillar collagen I (top). The relative invasion through fibrillar collagen I over 60 μm was quantified (bottom left). Representative immunoblot validating Swip1 silencing is shown (bottom right). *P = 0.0418 and **P = 0.0055. d,e, Three independent experiments were performed. f, Representative images of Swip1 staining in samples of HER2+ and TNBC breast cancer tissue microarrays (left) and the percentage of tumours with high, medium or low Swip1 (top right). Overall survival of 133 patients with TNBC with high (red) or medium and low (blue) staining of Swip1 (bottom right). The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.84 (95% CI, 1.05–3.23). Scale bars, 20 μm. b,c,e, Boxplots display the median and quartiles of the data and the whiskers display the maxima and minima. The mean of the data are indicated with a + symbol. a,b,d,e, Representative immunoblots validating silencing are shown. a–c,e, Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney tests; n is the number of analysed cells (a), adhesions (b) or puncta (c) pooled from three independent experiments. Unprocessed blots and numerical source data are provided.

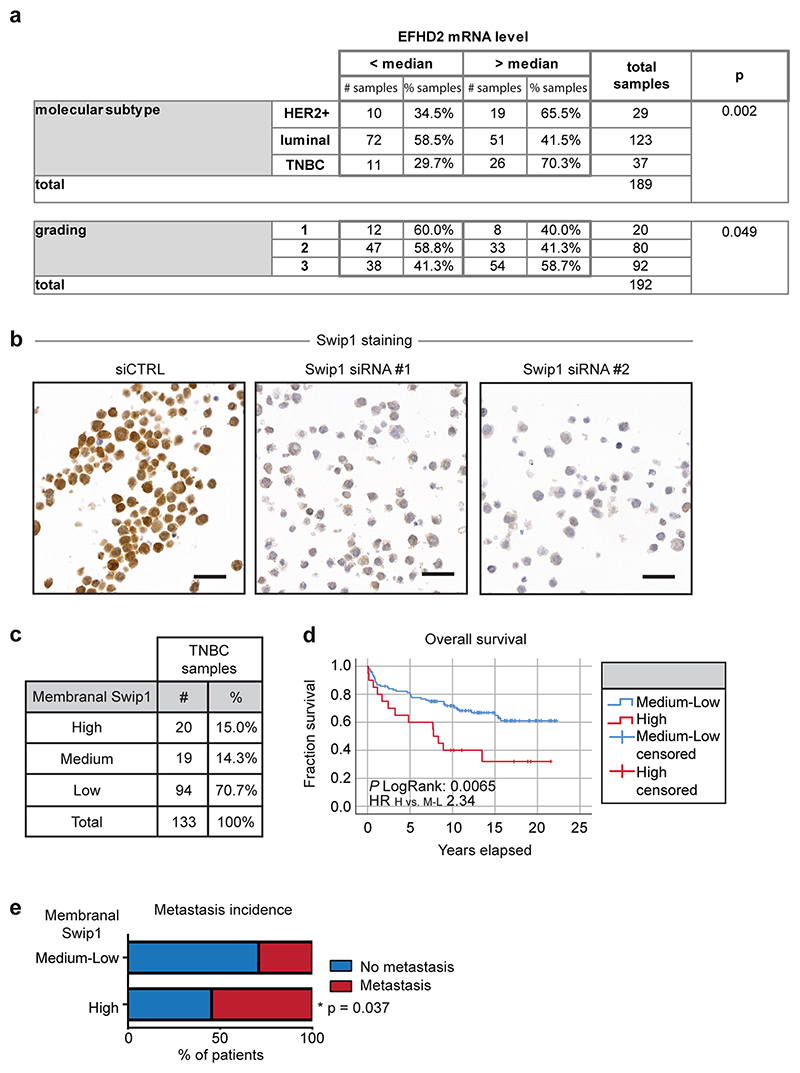

High Swip1 levels are a negative prognostic factor in TNBC

To assess the clinical relevance of our findings, we analysed Swip1 expression in a cohort of human breast cancer samples. Quantitative PCR analyses of the Swip1 messenger RNA levels of 192 breast cancer specimens revealed that Swip1 expression was significantly increased in the highest-grade tumours and the most metastatic breast cancer subtypes: HER2+ and TNBC (Extended Data Fig. 10). These findings were further validated by immunohistochemistry of Swip1 in HER2+ and TNBC tissue microarrays (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Swip1 was highly expressed in a large proportion of both breast tumour subtypes (65–75%). However, high Swip1 staining was only associated with a poorer clinical outcome in TNBC (Fig. 7f). Moreover, we found that patients with high expression levels of Swip1 on the plasma membrane had a more pronounced correlation with poor clinical outcome (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). Importantly, the Cox proportional hazards model showed that high membranal expression levels of Swip1 is associated with a poorer prognosis after adjustment for Ki67-positivity, tumour size, lymph node metastasis or tumour grade (Extended Data Fig. 10d). Finally, we observed that TNBC patients with high levels of membranal Swip1 had significantly more lymph node metastasis compared with patients with medium–low expression levels of Swip1 on the plasma membrane (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.037; Extended Data Fig. 10e). These data demonstrate that elevated Swip1 levels strongly and independently correlate with breast cancer metastasis and reduced survival in TNBC. These findings support the use of Swip1 as a prognostic marker for TNBC and as a potential drug target for this clinically challenging breast cancer subtype.

Discussion

Swip1 has not been previously associated with endocytosis, and evidence for specific cargo adaptors or selective uptake in the CG-endocytosis pathway has been lacking. Our findings place Swip1 as a validated cargo-specific adaptor for the CG pathway. Swip1 directs active Rab21 and β1-integrins to the CG pathway and is necessary for active integrin endocytosis through this route, while being fully dispensable for the uptake of other CG cargos. This demonstrates an important and unexpected feature of this pathway—the cargo-specific adaptor-based recruitment of receptors. It also highlights the possibility of unprecedented cargo-selective functions for the CG pathway in a manner similar to that described for numerous other endocytosed proteins following different endocytosis routes.

We find that IRSp53 is required for CG-pathway uptake of integrins and that this is important for efficient cell migration and invasion. This adds a pathway to the list of IRSp53-regulated cell migration and invasion mechanisms, including filopodia generation29,37, membrane ruffling38 and curvature sensing with WAVE at the neck of membrane invaginations39. Moreover, our findings shed light on previous studies demonstrating that Arf1 depletion results in defective adhesion and migration in MDA-MB-231 cells40–42. Integrin traffic is a key regulator of cell motility and adhesion dynamics in many different contexts43–45. We show that Arf1 depletion notably inhibits integrin uptake and induces the accumulation of large focal adhesions, similarly to Swip1 and IRSp53 silencing. These data link integrin uptake via the CG pathway to the regulation of cell adhesion. It has been shown that Arf1 is recruited to the forming endocytic pit long before scission and that Arf1 activation is a key regulatory step in promoting endocytosis via the CG pathway9,23. Our observation that Swip1 associates with inactive Arf1 supports a model where inactive Arf1 associates with the Swip1–Rab21–GTP–integrin complex and thereby concentrates the integrin cargo at the site of the forming pit. Subsequently, activation of Arf1 releases the cargo from its adaptor for association with actin, which persists during endocytosis through the CG pathway.

Interestingly, knockout of Swip-1 in Drosophila results in a mild adhesion defect similar to the deletion of the Rho-GAP-domain-containing protein GRAF1, another regulator of CLIC formation, suggesting an in vivo relevant role for Swip1 in the regulation of cell–ECM interactions32,46. We find that Swip1 facilitates cancer-cell migration in vitro and that high Swip1 correlates with increased cancer dissemination in patients, in line with Swip1 driving increased actin protrusion and migration in meta-static lung adenocarcinoma cells47. In macrophages, inflammatory shock-induced migration is Swip1-dependent48,49, while Swip1 deletion in mice induces faster B-cell migration in vivo; suggesting cell type- and possibly migration mode-specific roles for Swip1 (ref. 50). Importantly, these studies focus on the role of Swip1 as an actin regulator and the potential role of integrin traffic was not investigated.

Here we show that Swip1 acts as a cargo-specific adaptor that bridges the CG-endocytic machinery to Rab21-bound integrins, and couples Rab21 endosomes and their motility in cells to the actin cytoskeleton. This dual functionality of Swip1 regulates cell-adhesion turnover, migration and invasion. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the importance of these events in cancer progression, Swip1 expression has clinically relevant implications for TNBC. Thus, Swip1 and the mechanism of its interaction with Rab21 offer potentially exciting therapeutic targets for metastatic breast cancer.

Methods

Our research complies with all of the relevant ethical regulations; the use of the patient samples was approved by the Auria Biobank steering committee, University of Turku and the hospital district of Southwest Finland (approval number AB19-4522).

Cell culture, cell transfection and ECM coatings

The human TNBC cells MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% L-glutamine. BT-20 (TNBC) cells were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% L-glutamine. The cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; cat. nos MDA-MB-231, HTB-26; MDA-MB-468, HTB-132 and BT-20, HTB-19) and were routinely monitored for mycoplasma contamination. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts31 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FCS, 1% L-glutamine and 1 μg ml−1 puromycin. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293; ATCC, cat. no. CRL-1573) cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FCS and 1% L-glutamine. No commonly mis-identified cell lines were used for this study. MDA-MB-231 was authenticated by the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH, using short-tandem-repeat profiling and PCR assays to test the presence of mitochondrial DNA sequences from rodent cells, such as mouse, rat and Chinese and Syrian hamster cells. The other cell lines used in the study were not authenticated. Plasmids of interest were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or jetPRIME (Polyplus transfection) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of proteins of interest was suppressed using 27 nM siRNA and Lipofectamine siRNA max (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The siRNA used as control (siCTRL) was Allstars negative control siRNA (Qiagen, cat. no. 1027281). The siRNA oligonucleotides targeting Swip1 were purchased from Sigma (siRNA1, cat. no. SASI_Hs01_00186848; and siRNA2, cat. no. SASI_Hs01_00186847). The siRNA oligonucleotides targeting Arf1 and IRSp53 were purchased from Qiagen (siARF1#1, Hs_BCAR1_5 FlexiTube siRNA, cat. no. SI02757734; and siBCAR1#6, Hs_BCAR1_6 FlexiTube siRNA, cat. no. SI02757741). Coverslips were coated with 10 μg ml−1 fibronectin (Sigma, FC010), 12 μg ml−1 laminin-1 (Sigma, L4544) or 300 μg ml−1 collagen I from rat-tail (Sigma, 08–115).

Plasmids

Human Rab21 (amino acids 16–225) constructs were cloned into the Gateway destination vector pgLAP1 (Addgene, plasmid 19702) to express Rab21 with an amino-terminal GFP, followed by a TEV cleavage site and an S-Tag in mammalian cells. We used pCR8/GW/Topo (Thermo Fisher), in which human Rab21 was cloned by TOPO cloning, as the entry vector. The Rab21 mutants Q76L (active) and T33N (inactive) were introduced into the entry clone by site-directed mutagenesis. Mouse full-length Swip1, ΔEF1-Swip1 (deletion in the EF1 domain, amino acids 96–166) and ΔEF2-Swip1 (deletion at the EF2 domain, amino acids 134–159) were a gift from D. Mielenz (Division of Molecular Immunology, Nikolaus Fiebiger Centre, University of Erlangen–Nuremberg, Germany). The corresponding coding sequences were subcloned into the pEGFP-N1 backbone vector using the XhoI and EcoRI restriction sites. Full-length Swip1 was also subcloned by TOPO cloning into the Gateway vector pCR8/GW/Topo. Next, a LR clonase II reaction was performed to shuttle full-length Swip1 into pGEX-4T1; mScarlet-I–Swip1 was generated from the GFP-tagged construct by introducing the mScarlet-I sequence using the AgeI and MfeI restriction sites. To generate mScarlet–ΔEF1-Swip1, the ΔEF1-Swip1 fragment was PCR amplified from pEGFP–ΔEF1-Swip1 using the 5′-agatctcgaGATGGCCACGGACGAGTTGGC -3′ and 5′-cggtggatcCATCTTGAACGTGGACTGCAGCTCCTTAAAGG-3 ′ primers, which added amino- and carboxy-terminal sites for the XhoI and BamHI restriction enzymes, respectively (indicated by lowercase letters). This fragment was then ligated into the mScarlet-I–Swip1 vector backbone after both had been digested with XhoI and BamHI. HA–Arf1 and Arf1–GFP were obtained from Addgene (plasmids 79409 and 49578). IRSp53–mCherry and IRSp53–GFP were generated by the Genome Biology Unit, supported by HiLIFE and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, and Biocenter Finland. The pDEST-V1–Rab21 plasmid was generated by shuttling the human Rab21 sequence (pENTR201-hRab21, ORFeome Library; Genome Biology Unit, supported by HiLIFE and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, and Biocenter Finland) into the destination vector pDEST-V1-ORF (Addgene, plasmid 73635). The pDEST-Swip1-V2 plasmid was generated by performing a clonase reaction between pCR8/GW/Topo-Swip1 and pDEST-ORF-V2 (Addgene, 73638). Finally, pEF.DEST51-mVenus was obtained from Addgene (plasmid 154899).

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this work are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Generation of stable cell lines and SILAC cell culture treatment

To generate stable GFP–Rab21-expressing mammalian cell lines, a Flp recombination target (FRT)-entry site was first introduced into MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells using the Flp-In technology (Thermo Fisher). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with pFRT/lacZeo2 and stable clones were isolated using Zeocin as the selection marker (200 μg ml−1). The resulting MDA-MB-231-FRT cell line was then co-transfected with the pgLAP1-Rab21 plasmid and pOG44, and stable clones were selected in 500 μg ml−1 hygromycin-containing medium and tested for GFP–Rab21 expression. Stable MDA-MB-231-GFP–Rab21 cell lines were cultivated in heavy (Arg-10/Lys-8) or light SILAC-DMEM medium plus hygromycin (200 μg ml−1) for 12 d to ensure at least ten replication cycles for efficient labelling. Hygromycin supplementation was omitted for the last two days before the co-immunoprecipitation experiment.

Screening for Rab21 interaction partners by GFP-pulldown

Each mass-spectrometry experiment consisted of a mixture of a GFP-pulldown in active GFP–Rab21-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells (WT or active Rab21 Q76L mutant) cultured in heavy medium and a GFP-pulldown in control cells (expressing GFP or the inactive GFP–Rab21 T33N mutant) cultured in light medium (forward experiment). In the reverse experiment, the heavy and light media were exchanged (label-swap experiment). Briefly, co-immunoprecipitation samples were prepared as follows. Cells (two 15 cm dishes) were cultured until they reached 60–80% confluence, washed with ice-cold PBSM (PBS + 5 mM MgCl2), harvested in PBSM, pooled and washed again. The cell pellets were resuspended in 600 μl lysis buffer LB (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl, 1.3% n-beta-octyl-d-glucopyranoside, 10% glycerol, protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and 500 μM GppNHp for GFP-active Rab21-expressing cells or 500 μM GDP for GFP-inactive Rab21-expressing cells) and lysed by douncing 40× in a tissue grinder (dounce homogenizer) and incubating on ice for 20 min. The insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation at 18,000g and the supernatant was incubated with 20 μl GFP-Trap agarose beads (Chromotek) for 60 min at 4 °C by overhead rotation. The beads were then washed three times with 500 μl washing buffer WB (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 300 mM KCl and 10% glycerol), combining the heavy, GFP-active Rab21 immunoprecipitation with the light, GFP-inactive Rab21 immunoprecipitation (forward experiment) during the second wash step. Proteins were eluted from the beads in 100 μl of U/T buffer (6 M urea + 2 M thiourea in 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0) for 15 min with shaking in a bacterial shaker at room temperature and an agitation rate of 1,400 r.p.m. The eluted proteins were collected and the process was repeated to maximize the protein yield. The eluted proteins were precipitated by adding 70 μl of 2.5 M Na-acetate, pH 5.0, 1 μl GlycoBlue (Thermo Fisher) and 1,700 μl ethanol to the pooled elution fractions (200 μl) in a 2 ml tube. After an overnight incubation at 4 °C, the precipitation mixture was centrifuged for 50 min at 20,000g and the resulting pellet was dried for 15–20 min at 60–70 °C.

We followed standard procedures for in-solution protein digestion51. Briefly, the pellets were solubilized in U/T buffer, reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated with iodoacetamide and digested by sequential addition of LysC (Wako) and Trypsin (Promega) overnight at room temperature. The peptides were desalted and stored on STAGE tips until analysis using liquid chromatography with tandem mass-spectrometry analysis. The samples were analysed using 240 min acetonitrile gradients on a 20 cm long reversed phase column with an inner diameter of 75 μm, which was filled with 3 μm C18 beads (Dr. Maisch), using a Proxeon HPLC system (Thermo Fisher) coupled to the electrospray ion source of a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode with a full scan (AGC target, 3 × 106; mass resolution (R) = 70,000), followed by up to ten MS2 scans (R = 17,500; maximal injection time, 60 ms) and a dynamic exclusion for 30 s. Raw files were analysed using MaxQuant (version 1.5.2.8), using default parameters, and searched against a Uniprot human protein database (2014–2010).

For visualization purposes, all of the identified proteins from each experiment were plotted (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a–d), where each spot corresponds to a protein identified by mass spectrometry. Each plot is representative of two independent experiments (forward and reverse, x and y axis), where every experiment consists of two independent immunoprecipitations. The mean log2-transformed fold-change values from both experiments were plotted against the absolute protein intensities (intensity-based absolute quantification, iBAQ) and significance B was calculated according to Cox and Mann52. The error function was estimated using the erfc as is implemented in the pracma package53 (R package version 2.2.9). Abundance bins were defined by including 100 proteins in a subsequent order.

The proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE54 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016478. The log10-transformed ratios of the proteins identified by mass spectrometry are also available (Supplementary Table 1).

Immunoprecipitations, bimolecular complementation affinity purification and immunoblotting

MDA-MB-231 and HEK293 cells expressing GFP-tagged or split Venus-tagged (V1 or V2) proteins (one 10 cm dish per condition) were washed with cold PBS, harvested in PBS and pelleted. The cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μl IP-lysis buffer (40 mM HEPES–NaOH, 75 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40 and protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and incubated at +4 °C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation (10,000g for 10 min, +4 °C). A fraction of the supernatant (20 μl) was kept aside as the lysate control. The remainder of the supernatant was incubated with GFP-Trap beads (ChromoTek, gtak-20), which bind to both GFP and complemented Venus (V1 + V2), for 1 h at 4 °C. Finally, the immunoprecipitated complexes were washed three times with wash buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1% NP-40) and denatured for 5 min at 95 °C in reducing Laemmli buffer before SDS–PAGE analysis under denaturing conditions (4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels). The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) before blocking with blocking buffer (Thermo, StartingBlock (PBS) blocking, 37538) and PBS (1:1 ratio). The membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. The membranes were then washed three times with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (LI-COR), diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer, at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were scanned using an infra-red imaging system (Odyssey; LI-COR Biosciences).

Antibody immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins were performed on MDA-MB-231 cell lysates (one 10 cm dish per condition). The cells were washed with PBS and harvested in 200 μl IP-lysis buffer. SureBeads protein G magnetic beads (Bio-Rad Laboratories, 161-4023) were thoroughly resuspended in their solution, and 100 μl (1 mg at 10 mg ml−1) were transferred to a 1.5 ml tube. The beads were then magnetized and the supernatant was discarded, after which the beads were washed three times with PBS-T (0.1% Tween). Next, 2 μg of antibody or isotype-matching IgG control (Supplementary Table 1) was added to the beads and kept at room temperature under rotation for 30 min, after which the beads were magnetized, the supernatant was discarded and the beads were washed three times with PBS-T. The cell lysate was then added to the beads and rotated for 1 h at room temperature. A fraction of the total lysate (25 μl) was set aside for use as a total lysate control. The beads were then magnetized, the supernatant was discarded and the beads were washed three times with TBST, after which the samples were centrifuged at 600g for several seconds. The beads were then magnetized and the residual buffer was aspirated off, followed by the addition of sample buffer, boiling (10 min at 95 °C) and separation using SDS–PAGE. Protein transfer and detection were performed as described earlier.

Protein purification

For the production of recombinant GST-tagged proteins (Rab21 16-225, Swip1 and GGA3), pGEX-4T1–Rab21 16-225, pGEX-4T1–Swip1 or pGEX6P1–GGA3-BL21 Escherichia coli Rosetta transformed cells were cultured and induced with 250 μM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5–0.8 at 22 °C in LB media overnight. The cells were then lysed and resuspended in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 300 mM NaCl and 3 mM DTT. The desired GST-tagged protein was purified from this suspension using a gravity GST-column. In the case of GST–Rab21, elution of the protein was followed by thrombin-cleavage and gel filtration in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl and 3 mM DTT buffer using a Superdex S75 16/60 column attached to a GST-column to bind the cleaved GST. Fractions containing the monomeric proteins were pooled, concentrated via ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra, 15 ml, 10,000 MWCO) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage at −80 °C.

For the production of His-fusion proteins (IRSp53, VASP and ARF1), E. coli BL21 Rosetta (DE3) cells picked from individual colonies were used to inoculate 200 ml of LB medium (containing ampicillin at 50 μg ml−1) and cultured overnight at 37 °C. Between 10 and 100 ml of the overnight culture was diluted in 1 l of LB and cultured in a bacterial shaker at an agitation rate of 240 r.p.m. at 37 °C until it reached an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.4–0.6. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (1 mM) was then added, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000g for 15 min at 4 °C after the induction and the pellets were used immediately or conserved at −80 °C after washing in PBS. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in His-lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10% glycerol); the samples were sonicated three times (30 s each) on ice and pelleted by centrifugation at 30,778g for 30 min at 4 °C using a JA 20 Beckman rotor or at 100,000g for 45 min at 4 °C using a 55.2 Ti Beckman rotor. A total of 600 μl of NiNTA beads (Qiagen), which had been washed three times with His-lysis buffer, was added to the supernatant and the samples were incubated 1–2 h at 4 °C with rocking. The beads were then washed twice in 20 mM imidazole, 600 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol and once in 40 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol (5 min, 4 °C). The beads were packed in Poly-Prep chromatography columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and eluted with 200 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol (500 μl fractions). The fractions, evaluated by Bradford assay and SDS–PAGE, were pooled and dialysed. The samples were aliquoted, flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol.

Nucleotide loading and GST-pulldowns

To load Rab21 with either a non-hydrolysable form of GTP (GppNHp) or GDP, 200 μM of recombinant Rab21 or GST–Rab21 were incubated with 10 mM EDTA and a 25× excess of the nucleotide (5 mM GppNHp or GDP) in exchange buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl and 3 mM DTT) for 1 h at 25 °C. The EDTA-based exchange reaction was then stopped by the addition of 40 mM MgCl2 and incubation for 15 min on ice. The buffer was exchanged with measuring buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl and 3 mM DTT) to reach the desired protein concentration using 10 kDa ultrafiltration devices (Amicon). Equal amounts of nucleotide and protein were added to ensure complete loading of Rab21 with the desired nucleotide.

GST-pulldowns using purified GST fusion proteins and recombinant Rab21 bound to GppNHp, GDP or no nucleotide (in the presence of EDTA) were performed as follows. GST–Swip1 or GST–Appl1 (50 μg) were incubated with 200 μg of recombinant Rab21 for 30 min before incubation with Glutathione Sepharose beads for an additional 30 min. The bead-bound proteins were divided in two fractions and separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by either Coomassie staining or immunoblotting with anti-Rab21. The pulldowns were performed three times.

Overlay assay

Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated in TBST 0.1% Triton X-100 buffer and allowed to dry. Equal or increasing amounts of recombinant purified proteins were spotted on the membranes and allowed to dry. The membranes, previously blocked in TBST 0.1% Triton X-100 with 5% milk, were then incubated with the recombinant protein of interest, resuspended in TBST 0.1% Triton X-100 with 5% milk, for 1–2 h at 4 °C. After extensive washing in TBST 0.1% Triton X-100, the membranes were subjected to western blot analysis with the desired antibodies.

In vitro binding of GST–Swip1 to Arf1T31N or Arf1Q71L

Cell lysates from HEL293T cells transfected with HA-tagged Arf1T31N or Arf1Q71L (lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail) were incubated with equal amounts (2 μM) of GST–Swip1 or GST, as the control, for 1 h at 4 °C. The reactions were washed three times in lysis buffer. After washing, the beads were resuspended in 2×SDS–PAGE sample buffer (1:1 vol/vol), boiled for 10 min at 95 °C, centrifuged for 1 min and then loaded onto polyacrylamide gels.

SIM microscopy and co-localization analysis

Cells growing on uncoated glass or collagen I-coated dishes were fixed with 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, blocked with 10% horse serum and incubated with antibodies to the indicated endogenous proteins. This was followed by incubation with fluorophore-labelled secondary antibodies (AF568-, AF488- or AF647-labelled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit; Life Technologies). For visualization of Swip1-containing invaginations, cells expressing mScarlet-I–Swip1 were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min before fixation. The cells were imaged using an OMX DeltaVision system and spot co-localization analysis was performed in Z stacks of the cells using the plugin ComDet in ImageJ (https://imagej.net/Spots_colocalization_comdet), which allowed for improved detection of the invaginations as it ignores non-homogeneous cytoplasmic background. Using this plugin, we pinpointed the mScarlet-I–Swip1 spots (pixel size, >5) and analysed co-localization, based on proximity (pixel distance, 4), with spots from the second channel stained for the protein of interest. Next, the ratio of co-localization with mScarlet-I–Swip1 was calculated as a percentage of co-localized spots per cell. At least 30 cells per condition were imaged and analysed. The co-localization plots show the mean ± 95% CI. Statistical significance compared with the control condition was calculated. Representative rendered images of the invaginations (x–z plane) were visualized using the IMARIS software (Oxford Instruments, version 8.1.2).

PLA

MDA-MB-231 cells growing on coverslips were fixed, washed twice with PBS and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were stained using anti-Swip1 (1:100) and anti-Rab21 (1:50) primary antibodies diluted in 5% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature. Proximity ligation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Duolink in situ PLA, Sigma-Aldrich). Interactions between Swip1 and Rab21 in cells were detected using confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, ×63/1.4 Apo oil objective) and the number of PLA spots per 1,000 μm3 was determined using the IMARIS software. For the PLA between active β1-integrin (12G10) and IRSp53, MDA-MB-231 cells growing on glass-bottomed dishes (and for Fig. 4i, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing GFP or GFP–Swip1) were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min before fixation, after which they were washed and permeabilized as described above. The cells were stained using 12G10 (1:100) and anti-IRSp53 (1:300) primary antibodies diluted in 5% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature. The PLA was performed as described above and imaged using a 3i (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, 3i Inc) Marianas spinning disk confocal microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-W1 scanner and a back-illuminated 10 MHz EMCDD camera (Photometrics Evolve) with a ×63/1.4 oil objective, controlled by the Slidebook (version 6) software.

BiFC and TIRF microscopy

MDA-MB-231 cells growing in glass-bottomed dishes were co-transfected with split Venus constructs (pDEST-V1–Rab21 and pDEST-Swip1–V2) and imaged 30 h after transfection. Imaging was performed using a DeltaVision OMX v4 system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) fitted with an Olympus APO N ×60 oil TIRF objective lens, 1.49 numerical aperture (NA), used in TIRF illumination mode. The emitted light was collected on a front-illuminated pco.edge sCMOS (pixel size, 6.5 mm; readout speed, 95 MHz; PCO AG) controlled by SoftWorx. The TIRF angle for all channels was maintained at 83.5°. Images were taken every 500 ms for 2 min at 37 °C in presence of 5% CO2. Imaging of the above-mentioned BiFC constructs together with different endocytic vesicle markers was performed using a 3i (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, 3i Inc) Marianas spinning disk confocal microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-W1 scanner and a back-illuminated 10 MHz EMCDD camera (Photometrics Evolve) using a ×63/1.4 oil objective. The cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, blocked with 10% horse serum and incubated with antibodies to the indicated endogenous proteins. This was followed by incubation with fluorophore-labelled secondary antibodies (AF568-, AF488- or AF647-labelled anti-mouse, anti-rabbit or anti-goat; Life Technologies).

DNA-PAINT

For two-colour single-molecule localization microscopy (Extended Data Fig. 4a), we used DNA-PAINT24. Cells overexpressing GFP–Swip1 and HA–Arf1 were fixed and labelled using primary antibodies to GFP (Abcam, ab1218) and HA-tag (Cell Signaling, 3724), respectively. The cells were then stained with the appropriate secondary antibodies coupled to PAINT DNA handles (Ultivue). Imaging was performed using a DeltaVision OMX v4 system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) fitted with an Olympus APO N ×60 oil TIRF objective lens, 1.49 NA, used in TIRF illumination mode. Emitted light was collected on a front-illuminated pco.edge sCMOS (pixel size, 6.5 mm; readout speed, 95 MHz; PCO AG) controlled by SoftWorx. First, a TIRF image of GFP–Swip1 was acquired, followed by the DNA-PAINT acquisitions.

DNA-PAINT imaging was done sequentially, first for GFP–Swip1 (10,000 frames, 50 ms) and then Arf1 (10,000 frames, 100 ms) in PAINT buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 nM of the corresponding PAINT imager strands coupled to AF647 (GFP–Swip1) or AF568 (Arf1). For both conditions, full laser power was used and the beam concentrator was enabled. No cross-talk between the channels was observed. The ThunderSTORM55 ImageJ plugin56, with the Phasor-based localization two-dimensional method57, was used for the localization of single fluorophores. After filtering out localizations to reject photon counts that were too low, the translational shifts were corrected by autocorrelation. Image reconstructions were performed using the ThunderSTORM ImageJ plugin.

Endocytosis assays

MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468 and BT-20 cells were cultured on uncoated plastic dishes or glass coverslips, unless otherwise stated. For integrin endocytosis assays, surface integrins were labelled with an antibody that recognizes the active conformation of β1-integrins (12G10) at 4 °C, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, unless otherwise stated. The antibody remaining on the surface was washed away with acid (0.2 M acetic acid and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 2.5). The cells were subsequently fixed with 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin and incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody to visualize and quantify the amount of internalized integrins. Several fields were randomly imaged with identical microscope settings using a 3i (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, 3i Inc) Marianas spinning disk confocal microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-W1 scanner and a back-illuminated 10 MHz EMCDD camera (Photometrics Evolve) using a ×63/1.4 oil objective. Quantification of the endocytosed integrins was performed on three-dimensional projections of the cells using the IMARIS software with the ‘spots detection’ function. The sum of the intensities of all of the vesicles in a cell was divided by the volume of that cell. All of the intensity values were then normalized to the average of all cells in the control condition (siCTRL). A similar procedure was followed for the uptake of MHCI (Sigma, SAB4700637) and 9EG7 (active β1-integrin).

For the AF568-labelled transferrin (Thermo Fisher, T23365) and 10 kDa dextran–TMR uptake experiments, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 1 mg ml−1 of transferrin, 10 kDa dextran–TMR (Invitrogen, D1816) or 10 kDa amino dextran (Molecular Probes) conjugated to FITC during the 15 min incubation at 37 °C. For the double-uptake experiments, the cells were previously labelled with 12G10–AF488 antibody (Abcam, ab202641) at 4 °C as described above. After the internalization step at 37 °C, the remaining fluorescently labelled molecules at the cell surface were removed with an acid wash, followed by fixation, labelling of the plasma membrane with WGA lectin and imaging as described above.

Surface biotinylation-based integrin trafficking assays were performed based on previously published methods58,59, with some modifications. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were prepared by coating Nunc MaxiSorb 96-well plates (Thermo Fischer, 44-2404-21) with 5 μg ml−1 anti-integrin in TBS (50 μl per well) overnight at +4 °C (see Supplementary Table 1 for the antibody details). The wells were blocked with 5% BSA in TBS for 2 h at 37 °C. MDA-MB-231 cells, silenced three days before the experiment, as described earlier, were cultured in 10% FCS-containing medium on 6 cm dishes to 80% confluency. The cells were placed on ice and washed once with cold PBS. Cell surface proteins were labelled with 0.13 mg ml−1 EZ-link cleavable sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Thermo Scientific, 21331) in serum-free DMEM medium for 30 min at +4 °C. The unbound biotin was washed away with cold medium and the cells were incubated for 15 min on ice in cold serum-free DMEM with or without 100 μM primaquine (Sigma, 160393). Pre-warmed serum-free DMEM (with or without primaquine) was added to the cells. The biotin-labelled surface proteins were allowed to internalize at +37 °C for the indicated time periods, after which the cells were quickly placed back on ice and rinsed with cold DMEM and cold cell surface reduction buffer (50 mm Tris–HCl, pH 8.6 and 100 mm NaCl). The remaining biotin at the cell surface after internalization was removed with 30 mg ml−1 MesNa (sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate; Fluka, 63705) in MesNa buffer for 20 min at 4 °C, followed by quenching with 100 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) for 15 min on ice. To determine the total amount of surface biotinylation, one of the cell dishes was left on ice after biotin labelling, followed by treatment without reducing MesNa. For the 0 min internalization, cells were maintained on ice in serum-free DMEM until cell surface reduction with MesNA. The cells were lysed by scraping in lysis buffer (1.5% octylglucoside, 1% NP-40, 0.5% BSA, 1 mM EDTA, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and incubation at +4 °C for 20 min. The cell extracts were cleared by centrifugation (16,000g, 10 min, 4 °C). To calculate the amount of internalized, biotinylated integrins, 50 μl volumes of the cell lysates were incubated in duplicate wells at +4 °C overnight, washed extensively with TBST, incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 1:1,000 horseradish peroxidase-coupled streptavidin (Fisher, 21130), washed and detected with antibody for ELISA detection.

For the FACS-based EGFR endocytosis assay, adherent cells were labelled with 1:500 extracellular domain-binding EGFR antibody (UpState, 05-101) on ice for 30 min. The unbound antibody was washed away and the cells were chased in warm medium in the presence or absence of 10 ng ml−1 EGF. The cells were washed with cold PBS and carefully collected by scraping. Next, the cells were fixed for 10 min at 4 °C with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed and resuspended in PBS, followed by incubation with AF647-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min (1:300 dilution in PBS; Invitrogen), washed with PBS and analysed using a LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using the Flowing software (version 2; Cell Imaging Core of the Turku Bioscience Centre). The geometric mean of the fluorescence intensity from cells labelled with secondary antibody alone was used as the background and subtracted from the stained samples. For normalization, the background-corrected values were divided by the sum of all signals from one independent experiment. Representative raw flow cytometry data can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Hypo-isotonic shock

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with siCTRL, or siRNA1 or siRNA2 against Swip1 and used 96 h after silencing. The cells were maintained in either isotonic (100% incomplete DMEM medium) or hypotonic (50% incomplete DMEM and 50% sterile double distilled water) medium for 1 min, followed by pulse of various cargos in isotonic media for 1 min. The pulse contained the following cargos: anti-β1-integrin (12G10 conjugated to AF488; 2 μg ml−1), 1 mg ml−1 10 kDa dextran conjugated to tetra methyl rhodamine and 10 μg ml−1 transferrin conjugated to AF647. After the pulse, the surface-bound cargoes were stripped with 0.2 M acetic acid and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 2.5 for 3 min on ice and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then imaged using confocal microscopy as described earlier and the cell mean intensity of each cargo was quantified using manual segmentation with ImageJ.

Electron microscopy and APEX labelling

APEX labelling of GFP–Swip1 for electron microscopy was performed as previously described35. Briefly, mouse embryonic fibroblasts were transfected with GFP–Swip1 and GBP-APEX (Addgene, plasmid 67651) constructs using a Neon transfection system (as per the manufacturer’s instructions) and plated into 35 mm tissue culture dishes. After 24 h, the cells were incubated on ice for 30 min, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and washed three times in cacodylate buffer and once in 1 mg ml−1 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) solution in cacodylate for 5 min. The cells were then subjected to the DAB reaction in the presence of H2O2 for 30 min and stained with 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 min. The cells were processed in situ with serial dehydration in increasing percentages of ethanol, followed by serial infiltration with LX112 resin in a Pelco Biowave microwave before overnight polymerization at 60 °C. Ultra-thin (60 nm) sections were cut on a Leica UC6 microtome parallel to the culture dish and micrographs were acquired using a Jeol 1011 transmission electron microscope.

Vesicle tracking

For Rab21-vesicle tracking, MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing GFP–Rab21 were transfected with one of two different siRNA sequences to deplete Swip1. In the rescue experiment (Fig. 6i), control- and Swip1-silenced cells were transfected with GFP–Rab21 and either mScarlet-I–Swip1 or mScarlet-I–ΔEF1-Swip1. The movement of the Rab21 vesicles was followed for 2 min using TIRF microscopy (Visitron SD-TIRF Nikon Eclipse TiE with a ×60 Olympus TIRF oil objective, 1.49 NA, or DeltaVision OMX v4 as described in the ‘BiFC and TIRF microscopy’ section). For each cell, GFP–Rab21 vesicles were imaged every 500 ms, for 2 min. The TIRF angle was kept constant at 85.5°. The vesicles were detected and tracked using the ‘spots tracking’ function in the IMARIS software. The parameters used in the algorithm were an estimated diameter of spots/vesicles of 0.5 μm, background subtraction and Brownian motion for modelling the vesicle movement, with a maximum distance of 20 μm for the displacement length and a maximum gap size of 3 μm between spots. We used the mean speed of all vesicle tracks in one cell to then calculate the average speed of the vesicles for each cell. At least ten cells per condition were analysed and data from three independent experiments were quantified.

Focal adhesion analysis

Cells were plated on dishes coated with the indicated ECM component (collagen I, laminin-1 or fibronectin), fixed and immunostained with an antibody that recognizes the focal adhesion-component vinculin, present in mature adhesions. At least six cells per condition per experiment were imaged and analysed (18 cells per condition in total from three independent experiments). Vinculin-positive focal adhesions were detected from an image mask created using the ImageJ software following background subtraction and setting of a median Gaussian filter (3.0). The number of focal adhesions (detected particles) and the total cell area occupied by focal adhesions in each cell were quantified from the image mask.

Adhesion dynamics