Abstract

We explored carers experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in England to identify long-term impacts and implications, and to suggest future support for caregivers.

Data were collected during COVID-19 rapid response studies (IDEAL-CDI; INCLUDE) from carers participating in a British longitudinal cohort study (IDEAL). Semi-structured interview data were compared to their accounts from previous interviews conducted during the first 18 months of the pandemic.

There was indication of some return to pre-pandemic lifestyles but without appropriate support carers risked reaching crisis point. Evidence points to a need for assessment and management of support needs to ensure well-being and sustainable dementia caregiving.

Keywords: COVID, qualitative, care services, quality of life

Introduction

Carers are individuals who provide care for individuals with a chronic illness or disability that is unpaid or informal. They are crucial for supporting people with dementia living in the community. Caring yields both positive and negative experiences (Lindeza et al, 2020; Quinn et al, 2019; Quinn and Toms, 2018). Several factors influence carers’ wellbeing, including their own experiences of caring and their psychological and physical health (Clare et al, 2019). Although carers are often resilient (Dias et al, 2016; Jones et al, 2019; Kalaitzaki et al, 2022) adverse external events or challenges can disrupt the caring equilibrium. The global COVID-19 pandemic (henceforth ‘the pandemic’) can be viewed as one such event.

Qualitative research from early in the pandemic reported carers experiencing difficult feelings of loneliness, isolation loss of control and uncertainty (Giebel et al, 2021; Hanna et al, 2021; Roach et al, 2021) and poorer health and wellbeing (Sriram et al, 2021). Evidence from surveys also found carers experienced stress (Cohen et al, 2020; Zucca et al, 2021); anxiety, depression, burden (Masterson-Algar et al, 2022; Tsapanou et al, 2021) fatigue (Bacsu et al, 2021) and role overload (Savla et al, 2021). Structured interviews collected from a large British cohort before and during the pandemic showed carers were lonelier, experienced less life satisfaction and felt more captive in their caring role during the pandemic (Quinn et al, 2022). Another longitudinal survey conducted in Portugal found carer burden increased during periods of social restriction when compared to data collected four months prior to the start of the pandemic (Borges-Machado et al, 2020). Other longitudinal surveys have compared responses under differing levels of social restriction in place at different stages during the pandemic (Koh et al, 2020; Lara et al, 2020; Panerai et al, 2020) indicating that increased difficulties in carers’ experiences were attributable to the social restrictions imposed. Where changes in carers’ wellbeing have been reported, suggested explanations have included disruption to usual support networks (Hanna et al, 2021; Savla et al, 2021) and reduced functional ability or increased behavioural and psychological symptoms of the care recipient (Cohen et al, 2020; Pongan et al, 2021). However, not all longitudinal surveys have found evidence of difficulties. For example, one study found that compared to pre-pandemic levels there was little impact on carers’ overall experience of caring and no impact on wellbeing and quality of life (Gamble et al, 2022). In another study there was no change in carers’ distress scores during social restrictions compared to eighteen months before the pandemic (Daley et al, 2022), consistent with other similar findings measuring change in quality of life (Carbone et al, 2021; Gamble et al, 2022).

Findings on carers’ coping also vary. While some studies reported that carers were coping well (Losada et al, 2022), others have highlighted individual variability in the capacity to cope (O’Rourke et al, 2021; Roach et al, 2021). One explanation may lie in carers’ appraisals of their own ability to cope, as suggested by Savla et al (2021) who used the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) to examine carers’ appraisals of how circumstances early in the pandemic affected their ability to cope. A large questionnaire-based study compared a matched group of carers assessed on two occasions before the pandemic with carers assessed on two occasions during the pandemic and found that, while coping remained stable over time when assessed before the pandemic, during the pandemic carers coped better over time (Gamble et al, 2022). These adaptations are perhaps attributable to an accommodation to circumstances over time and development of coping behaviours (Goodman-Casanova et al, 2020; Savla et al, 2021) or personal resilience (Altieri and Santangelo, 2021). Indeed, Moretti et al (2021) found depression, anxiety and stress scores varied according to the level of pandemic restrictions in place at the time, suggesting that carers adapted to the prevailing circumstances.

The longitudinal evidence highlights the importance of looking at how carers’ experiences and coping ability evolved over time to understand the longer-term impact. Much of the existing evidence was collected in the first year of the pandemic. There is a need, therefore, to understand how carers’ ability to cope might develop in the longer-term. The overall aim of this qualitative study was to explore carers’ experiences approximately two years into the pandemic and, where possible, to compare their accounts with those they gave when interviewed earlier in the pandemic (IDEAL CDI; INCLUDE). We conducted the interviews during a time when social restrictions had eased in England but mask-wearing and working from home were recommended due to the emergence of the Omicron variant, with the aim of identifying longer-term impacts and implications and determining how best to support carers in the future.

Methods

Design

The study reported here was part of the INCLUDE project (Clare et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2022) set up to explore the experiences of people with dementia and carers during COVID-19 by recruiting people who were participants in the British IDEAL cohort study (Clare et al., 2014; Silarova et al., 2018). Carers were eligible if they were caring for a person with mild-to-moderate dementia living in the community. A small number of IDEAL participants had been interviewed in depth early in the pandemic, in May and July 2020 (O’Rourke et al., 2021) as part of the IDEAL COVID-19 Dementia Initiative (IDEAL-CDI), and the INCLUDE study built on this approach. INCLUDE participants completed structured telephone or online interviews between September 2020 and April 2021 (Clare et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2022), and a sub-set was interviewed using qualitative semi-structured interviews at one of two time points nested within the INCLUDE study timeframe: November to December 2020 (Pentecost et al., 2022) or January to April 2021 (Stapley et al., 2022). Table 1 shows how the timeline of INCLUDE data collection relates to the timeframe of the pandemic and associated social restrictions in England. Here, we report findings from a further round of qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted between December 2021 and January 2022 with carers who had been interviewed previously as part of IDEAL-CDI or INCLUDE. The timeframe covered a period of the pandemic when many restrictions were being lifted; the national vaccination programme had been ongoing since its commencement in December 2020, but infection rates were still high, and the new Omicron variant was emerging.

Table 1. Timeframe of INCLUDE data collection in relation to UK Government measures to manage the COVID pandemic.

| Date | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 | Oct 20 | Nov 20 | Dec 20 | Jan 20 | Feb 21 | Mar 21 | Apr 21 | May 21 | Jun 21 | Jul 21 | Aug 21 | Sep 21 | Oct 21 | Nov 21 | Dec 21 | Jan 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government measures | Major national social restrictions | Local restrictions | Major national and local social restrictions | Easing of social restrictions | |||||||||||||||||||

| National vaccination programme | Omicron variant; Booster vaccinations | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Data collection | IDEAL-CDI Study1 | * | |||||||||||||||||||||

| INCLUDE Quantitative data collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| INCLUDE interviews2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| INCLUDE interviews3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| INCLUDE current study4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: Qualitative Semi-structured interviews with:

11 carers plus

follow up (2 carers)

13 carers

7 carers

10 carers

INCLUDE was approved by Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 as an amendment to IDEAL-2 for England and Wales (18/WS/0111 AM12) and an extension was approved for the current study (18/WA/0111/ AM14). IDEAL was approved by Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (13/WA/0405) and IDEAL-2 by Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (18/WS/0111) and Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (18/SS/0037). IDEAL and IDEAL-2 are registered with the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN), reference numbers 16593 and 37955. Consent was recorded electronically prior to the interview and a copy of the consent form later sent to the participant either via email or post.

Participants and procedures

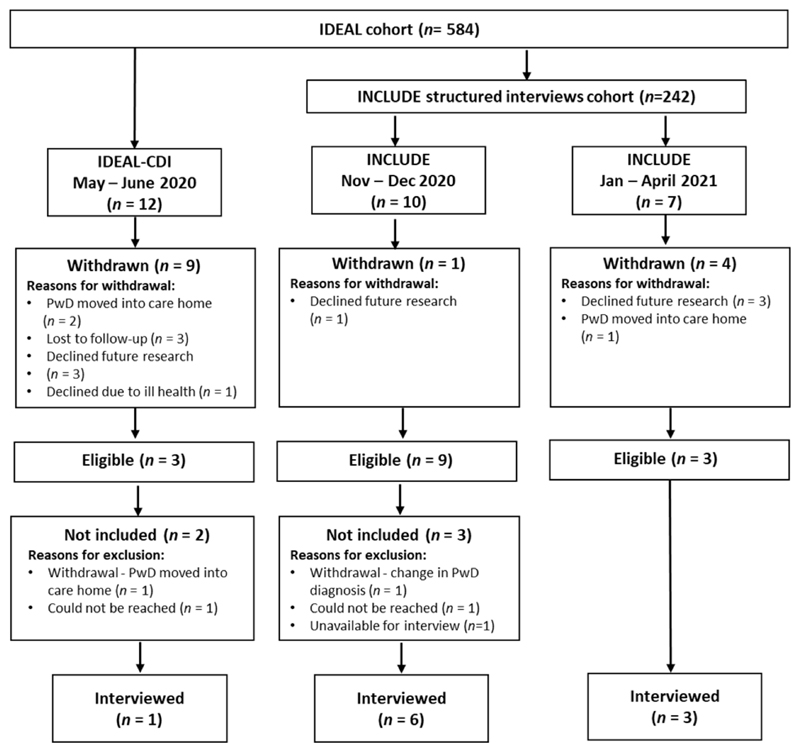

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of IDEAL cohort participants through the IDEAL-CDI and INCLUDE qualitative interview studies. We identified 29 carers who had previously taken part in IDEAL-CDI and INCLUDE qualitative semi-structured interviews; 15 met eligibility criteria and were contacted by telephone, and 10 agreed to participate.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing participation in the longitudinal interview study interviews.

Interviews were held remotely by telephone or Zoom according to preference and scheduled at a convenient time for the participant. A trained graduate research assistant (ED) conducted the interviews. The IDEAL advisory group, made up of people with dementia and carers (ALWAYs), contributed to the development of the INCLUDE study including the interview topic guides. These were developed to consider changes to routine and coping strategies, any benefits, and any support or health care suggestions. The topic guide for this set of interviews was based on the previous INCLUDE qualitative semi-structured interview topic guide and developed with input from our Patient and Public Involvement (ALWAYS) group (Litherland et al. 2018) but adapted to address the COVID-19 situation at the time. Questions were open-ended without a theoretical focus allowing for in-depth exploration of topics important to participants (see Supplementary Table 1). All interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data analysis was guided by the seven-stage framework analysis approach (Gale et al, 2013). The transcripts were supplemented by field notes containing observations and reflections made during and immediately after the interview (by RC). Further notes and key ideas from each participant’s previous IDEAL-CDI or INCLUDE interview were added, allowing initial comparisons between the previous and current interviews. Familiarization was undertaken by the data analysis team (RC, ED, CP, SS) and involved listening to the new audio recordings, reading the transcripts and annotating the transcripts and field notes. This process enabled the researchers to understand how individuals’ experiences at this stage of the pandemic compared with earlier interviews. Weekly discussions amongst the data analysis team supplemented the analysis process and were followed by wider discussions with members of the IDEAL programme team.

An initial coding framework was generated from the coding frameworks used in the previous INCLUDE qualitative studies (by RC) without a theoretical focus. This framework was deductively applied to four randomly selected transcripts which were inductively coded by RC using NVivo 12 (QSR International, 2020). Additional inductively identified codes from the data were added to the deductive framework to highlight new or different experiences or views. RC completed back and forth checking both within and between cases for consistency of coding and re-classified codes as required. RC and ED discussed and agreed the framework and code descriptors. Using the working analytical framework, RC continued to deductively and inductively code and index the remaining interviews whilst checking coding within and between cases. To ensure methodological rigour, SS checked the framework, code names and descriptions of three randomly selected transcripts.

The data analysis team discussed the proposed themes with co-authors and further members of the IDEAL programme team. Details of the development of codes and associated themes and sub-themes from the different time points are presented in Supplementary Table 2. We allowed overlapping of carers’ statements to provide a holistic account of varied experiences. The data analysis team reviewed the themes to identify changes between individual interviews over time or differences in carer experiences.

Results

Sample characteristics

Ten carers participated in interviews between 14 December 2021 and 24 January 2022. The interviews lasted between 28 and 60 minutes. The characteristics of the carers and care recipients are found in Table 2. Five females and five males were interviewed, all but one by telephone (carer 7). The age of the carers ranged from 57-85 years (mean = 71). Most were white and British (70%). Five were university educated. All participants lived in urban or suburban areas. Eight carers were spouses and lived with the person with dementia. The care recipients were 57-94 years old and half were female. Four were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and four with frontotemporal dementia, including two with the behavioural variant. One had vascular dementia and in one case the specific dementia diagnosis was unknown. Half of the people had young onset dementia. Time since diagnosis ranged from 3 to 12 years (mean = 6.9).

Table 2. Characteristics of the carers and care recipients.

| Participant/Interview duration(min) | Carer | Person with dementia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous interview | Age | Sex | Ethnicity | Education | Location | Relationship | Living situation | Diagnosis type | Sex | Age | YOD1 | Years since diagnosis | |

| 1(34) | INCLUDE* | 75 | M | White British | University/professional qualification | Suburban | Spouse | Together | AD | F | 77 | - | 8 |

| 2(43) | INCLUDE* | 79 | F | White British | Vocational qualification | Urban - Town | Spouse | Together | FTD | M | 69 | - | 8 |

| 3(46) | INCLUDE* | 71 | M | White British | Vocational qualification | Urban - City | Partner | Separate | AD | F | 67 | Yes | 3 |

| 4(28) | INCLUDE† | 61 | M | White Other | University/professional qualification | Suburban | Spouse | Together | FTD2 | F | 59 | Yes | 4 |

| 5(37) | INCLUDE* | 73 | F | White British | University/professional qualification | Urban Town | Spouse | Together | FTD2 | M | 72 | Yes | 12 |

| 6(52) | IDEAL-CDI | 74 | F | White British | School leaving certificate at age 16 | Urban - Town | Spouse | Together | VaD | M | 77 | - | 10 |

| 7(49) | INCLUDE* | 62 | M | White British | University/professional qualification | Urban - Town | Spouse | Together | AD | F | 62 | Yes | 5 |

| 8(60) | INCLUDE† | 85 | F | White Other | University/professional qualification | Urban - Town | Partner | Separate | AD | M | 94 | - | 6 |

| 9(47) | INCLUDE* | 73 | F | White British | Vocational qualification | Urban - City | Spouse | Together | FTD | M | 76 | - | 6 |

| 10(37) | INCLUDE† | 57 | M | White NZ | School leaving certificate at age 16 | Urban - Town | Spouse | Together | Other3 | F | 57 | Yes | 7 |

Note: IDEAL-CDI (May-July 2020) (O’Rourke et al., 2021)

INCLUDE (November-December 2020) (Pentecost et al., 2022)

INCLUDE (January – April 2021) (Stapley et al., 2022)

Alzheimer’s disease, AD; vascular dementia, VaD; frontotemporal dementia, FTD

YOD –Young onset dementia refers to a diagnosis made before the age of 65 (Rossor et al., 2010)

Behavioural variant

Dementia caused by severe epilepsy & neurosurgery

Caregiver narratives

Carers provided individual, personal accounts illustrating positive and negative experiences of caregiving and their changing lives during the pandemic. We also identified potential lasting impacts of the pandemic on the carers, their caring role or on the care recipients with dementia. Consistency with or divergence from statements in previous interviews are illustrated for each carer in Supplementary Table 3.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis revealed variable experiences of carers of people with dementia approximately two years into the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis uncovered the fragile balance between carers doing well and not coping. Although changes in local pandemic and personal circumstances meant individual accounts of caring and coping also fluctuated, we identified three themes reflecting key areas of influence on the health and wellbeing of the carers and their ability to cope. These were ‘Reassessing ‘normal’ care’ with two subthemes (‘cautious optimism’ – getting back out there; a new normal but no going back); ‘Attitudes and roles of others in supporting carers’, with two subthemes (aiding the caring process; barriers to the caring process); and ‘caring under stress’. Illustrative quotes are provided below.

Theme 1: reassessing ‘normal’ care

This theme identifies views on not being able to return to pre-pandemic life, and the associated implications for their caring. Carers provided mixed accounts, ranging from positive re-evaluation and optimism to dissatisfaction with the changes in their lives. There was also reflection on their own definition of normality, emphasising the fluid nature of caring for somebody with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic with lack of certainty about current and future routines.

1.1. Cautious optimism – getting back out there

The easing of restrictions allowed some level of return to pre-pandemic ‘normality’, such as being able to meet up with family and friends and reinvigorating informal support networks. There were some reports of increased opportunities for returning to activities and interests outside the caring role. Some carers stated that dementia services (e.g. memory cafes, day care centres) had started to re-open. This benefitted both partners, providing some time apart and a return to social engagement for the person with dementia:

“She is meeting other people…with the best will in the world, if you are doing things at home all the time just with me, that’s quite wearing on both of us…So I think it’s a far better balance we have now; to both of our benefits.” (carer 7)

The return of dementia services offered carers opportunities to have their own space and respite. However, acknowledging uncertainty about whether services would remain open, carers were taking advantage in case they closed again. Some changes in routine, behaviour or coping strategies that had been established during the pandemic, such as online shopping or the use of online peer support groups, were being maintained as even with the lifting of restrictions these were still beneficial. This was because of the decline in the person with dementia, increased caring responsibilities, or enjoying the convenience.

1.2. A new normal but no going back

This subtheme identifies carers’ acknowledgment that the situation now is different from pre-pandemic life. Although some stated they thought life was returning to some level of stability, all carers spoke of an observed decline in functional ability, behaviour or changes in personality in the person with dementia during the course of the pandemic. Some also indicated that the decline had occurred since they had last been interviewed. This decline in condition was attributed to the natural progression of dementia, the effect of restrictions “because there was no structure, it speeded up his dementia” (carer 9), or a combination of both:

“He’s definitely different. But that’s, I think, more than the pandemic, well, as well as the pandemic. I mean, he’s got dementia, so he’s going to go downhill.” (carer 6)

This decline increased the level of caution regarding whether to return to pre-pandemic activities:

“It’s hard to decide, which is pandemic…or the fact my wife can’t do what she used to do is… is difficult in this… all I can think is, they’re split. But we’re still kind of wary of where we go, so…” (carer 4)

All carers stated they now spent more time caring and had needed to broaden the scope of what their caring role entailed. Several carers now compared their role to being a parent or commented on changes in their relationship with the care recipient. Overall, compared to previous interviews, there was less discussion about keeping the care recipient occupied and more about ensuring the person was content and happy.

Carers provided accounts of activities they had attended prior to the pandemic that were no longer suitable, due to the decline in the person with dementia. They either did not attend external dementia services in person or found an alternative means of support. One carer described how the care recipient, who had been diagnosed with young onset dementia, had previously attended young onset dementia services. However, due to the decline, the need for young onset specialist services was no longer considered necessary by the carer who found that generic dementia services more appropriate for an older clientele were now suitable.

“The group she attended pre-pandemic was geared towards early onset. So they were all people in their late 50s, early 60s. [You know], quite active and… but as the condition progresses, in some ways, she now… It doesn’t matter so much that it’s more of an elderly place; she, you know, she joins in quite happily.” (carer 7)

Three carers also reported that dementia care services that had closed at the beginning of the pandemic had permanently closed, some due to lack of funding. Some carers believed this would further accelerate the deterioration in the person with dementia as the opportunity to engage with others outside the home environment became less available:

“Well, she’s not going to get any better, it’s going to get worse. And because we don’t… they don’t… they’re not doing the dementia clubs anymore.” (carer 10)

Theme 2: attitudes and roles of others in supporting carers

The behaviour and role of others influenced the carers’ ability to care during social restrictions. The attitudes of others also influenced how carers felt about themselves. The attitude and roles of healthcare professionals and family, friends, neighbours or wider society, and the way in which support and information was provided, had positive or negative impacts on carers and their caring experience. Accounts identify how the actions of others changed at different stages of the pandemic and the short- and long-term implications of these.

2.1. Aiding the caring process

Other people’s behaviours and actions were shown to influence how carers feel. Most carers relied on paid professionals to provide home care support or domestic tasks. However, where available, there was also a high reliance on local volunteers, friends or family. This dependence on others allowed the carers opportunities to partake in their own interests, undertake other responsibilities, or enjoy personal space. One participant described relying on her daughter so she could return to the choir for 90 minutes a week:

“I mean, all my hobbies have gone except my choir has started off again… I did used to take [person with dementia] before the pandemic, but I don’t take him anymore.” (carer 6)

However, other than occasional celebrations, this was only when her daughter was available and thus her only opportunity to have time away from her caring role.

Many carers also provided examples of the existence of fortuitous relationships with people who were able to provide advice, for example relatives who were healthcare professionals, and on whom they relied for information and guidance where official sources were lacking.

Carers also discussed their appreciation of the positive role individuals played, especially those “doing [it] off their own back” (carer 9), and one described her family doctor as “very sympathetic” (carer 2) regarding her caring role which helped her feel supported. One carer described how relationships with family and close friends had changed throughout the pandemic and communication was continuing via remote methods. This impacted on the ability to ask for help, and although the emphasis had shifted to relying on less familiar acquaintances, this would likely continue in the near future.

“I suppose, must get used to the fact that people at a distance are not… are not immediately available. Not in the way they used to be. But instead of which, I find that the community and local friends have come to the fore.” (carer 8)

2.2. Barriers to the caring process

Some attitudes or behaviours of others intentionally or inadvertently had a negative impact on carers. Although there was an overall indication of carers returning to activities outside the home, the presence of COVID-19 was still influencing their decision-making about re-joining groups, using public transport, socialising and keeping the person with dementia safe. Specifically, behaviours of others, such as not respecting personal space, was still causing concern and preventing some carers from fully returning to social interaction outside the home, as they “simply don’t care” or are “just idiots and don’t think about other people.” Indeed, even the change in the behaviour of friends at different stages of the pandemic and associated social interaction rules, such as the introduction and removal of ‘support bubbles’, had negative implications. Support bubbles were introduced by the UK Government between June 2020 and July 2021 to assist people living on their own by allowing two eligible households to socialise together:

“At the start of the whole thing one of my friends became in our bubble and so we saw quite a lot of her, but she’s… you know it’s eased off a bit now and I can’t do the things that I used to be able to do.” (carer 2)

As with the earlier interviews, there was a feeling that the government and wider society did not consider carers throughout the pandemic, for example by not providing specific guidance or help. This led to a continuation of carers thinking they were being treated “as if we were absolute nobodies” (carer 9) or considered “invisible” (carer 6) and that “nobody seems to care.” (carer 10). This led to continued feelings of abandonment and extended to healthcare professionals: “The professionals are the ones that sort of like let us down a bit more.” (Carer 9).

Indeed, if support was forthcoming, it was sometimes felt to be “perfunctory” (carer 4), “cursory” (carer 4) or due to someone having “been prompted by somebody else” (carer 9), rather than reflecting a genuine sense of care. When the carers were asked to provide advice about how healthcare professionals or volunteers could best help people in similar situations, most responses were about the need for a more positive attitude and a more proactive approach, for example “be prepared to listen” (carer 1) and “[present a] real feeling that someone’s taking an interest” (carer 1). They appreciated the healthcare professionals who showed concern and provided time:

“You just need that open question as to how things are, and have time to have a conversation… Put the pen down, sort of thing and, “How are you?”” (carer 7)

This need for proactive, interested individuals is heighted by the reliance of external dementia services on volunteers. Linking to the subtheme above ‘a new normal but no going back’, one carer highlighted how the lack of volunteers prevented dementia clubs from re-opening:

“They’re not doing the dementia clubs anymore, because they can’t get the volunteers.” (carer 10).

Theme 3: caring under stress

Carer narratives illustrated how the combination of the pandemic and the deterioration in the person with dementia, along with the extra challenges they were facing, created additional stress and influenced the balance between coping and not coping. Carers were generally open about how they were feeling about their ability to cope, with one carer describing their situation as “totally enveloping” (carer 4) and another saying the pandemic had left her feeling as if her “personal space really doesn’t exist now.” (carer 2).

One carer stated that his own perception of how they were coping was different from how others perceived the situation:

“I think I’m coping reasonably, but I’m being reminded by good friends and good daughters that I’m not coping as well as I think I am.” (carer 1)

There was also a belief that carers would benefit from specific carer training as they were “learning on the hoof” (carer 6), especially as the care recipient’s condition deteriorated. This was captured by one carer who highlighted his feelings of doubt around his caring role:

“There’s no [training] and it would be so simple to organise. You just think, ‘Well I’m doing all these things but actually, am I doing it right? … for folks like me that would be so useful…if you put a new member of staff into a [residential] care home or something, straight away, you would be put through some kind of training process, wouldn’t you?” (carer 7)

This carer then went on to discuss how beneficial it would be to have training on different aspects of dementia care, such as safely moving somebody or strategies for dealing with dementia-related behaviours. Furthermore, there was limited receipt of guidance and support from healthcare professionals and carer services during the pandemic. In one case, support received during the earlier stages of the pandemic had ceased by the time of the interview:

“I: And have you still been receiving phone calls from the [Dementia charity]?

P: No, that’s stopped now. That was obviously a temporary thing. But that’s now disappeared.” (carer 1)

If they did receive support, it was not always appropriate or available in a useable format: for example, for those without access to the internet. To replace formally organised support groups attended prior to the pandemic some carers had been pro-active and formed informal support groups among themselves. Some groups were initiated and delivered online earlier in the pandemic and were continuing in the same format; others were starting to meet in person with the lifting of social restrictions. However, these groups discussed a limited number of topics and the lack of professional input led to requests or questions unanswered. In addition, talking to healthcare professionals on the telephone rather than face-to-face made one carer feel he had not had the opportunity to fully express himself and was “drawn down a blind alley” (carer 1), left feeling he had not got across what he felt, and had missed an important opportunity.

Carers also divulged some of the challenges and frustrations they had faced when applying for statutory carer support or undergoing financial assessments to reduce caring and financial burdens. Discussions around these topic areas were more prevalent in these interviews than in the interviews earlier in the pandemic. Applications were often delayed, as providers were likely to be dealing with staff shortages or a backlog of applications as a consequence of the pandemic. With waits of up to 6 months, this lag in support was an added layer of carer stress and burden.

“Social Services, I’ve struggled with them a little bit. Both making contact and getting what I need.” (carer 6)

For some, the delays or lack of statutory carer or financial support had far-reaching implications, leading to difficult choices. Financial concerns increased due to the impact of the pandemic on the cost of living, particularly for those on fixed incomes or state benefits:

“So you’re worried about if you’ve got enough to pay your heating bill and stuff like that, you know?” (Carer 10)

Carer 10 went on to discuss the impact of the closure of the free local dementia club that had offered musical activities that helped the care recipient, as it “seemed to mellow” her. Financial pressures meant the carer could not afford to replace this by buying their own musical instruments, despite the positive impact.

Since the previous interviews, extra pressures facing carers had arisen, such as a new need to provide care for another family member and the impact of that:

“My mother lives five miles away and is 81. She has now been diagnosed with dementia…So I’ve got that to consider as well… I’ve got two people that have got a call on me…my time is pretty pulled hither and thither.” (carer 4)

Furthermore, the impact of the pandemic has caused ongoing delays in referrals to healthcare and initiation of treatment. Many participants who had reported healthcare needs in earlier interviews were now at the point of needing urgent treatment; some, for example, were in constant pain or had mobility issues that affected their ability to care. When asked if he was saying that he felt burnt out with caring, one carer responded:

P: “Yes, absolutely, definitely. I will say though; I’m usually a very patient person, and I think if my health was better, I think I could, sort of, cope with it better. I think that doesn’t help because I’ve got chronic osteoarthritis, and even before the lockdown [restrictions], I was at the top of the emergency list…to have my knees replaced.” (carer 6)

Likewise, one participant felt “much more stressed” (carer 2) than before the pandemic and there was no indication that this level of stress was declining with the lifting of restrictions. This carer expressed the situation well:

“Carers have become very aware that the danger is that the carer can become the patient and the patient can become the carer.” (carer 8)

Discussion

Following from earlier reports (O’Rourke et al, 2021; Pentecost et al, 2022), this qualitative study explored the experiences of carers of people with dementia approximately two years into the COVID-19 pandemic in England during a time when restrictions were being eased. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only qualitative study to compare findings with previous accounts of carers’ experiences earlier in the pandemic. This provides a unique opportunity to study the ongoing impacts and experiences. The findings highlight variability in individual experiences with divergent narratives illustrating diverse personal challenges and circumstances. Regardless of the diversity, we identified common experiences with potentially lasting legacies. This is reflected in three main themes: ‘reassessing ‘normal’ care’; ‘attitudes and roles of others in supporting carers’, and ‘caring under stress’.

We found carers compared their experiences to the past and sought stability and normality where possible. The pandemic brought about sudden, extreme and numerous challenges to deal with, but even with eased restrictions, carers were not back to ‘normal’ in terms of their ability to mix; there were lasting changes to available support and the additional stress of dealing with noticeable decline in the person with dementia. Our data complements quantitative studies showing that a reduction in care recipient functioning or increased behavioural challenges have a detrimental impact on carer resilience (Altieri and Santangelo, 2021; Kalaitzaki et al, 2022; Stapley et al, 2022). Feelings of normality were improved however when restrictions eased, allowing opportunities for some to pursue their normal interests and return to support networks.

The transactional stress model has previously been applied to understand carers’ experience during the pandemic (Salva et al, 2021). The model suggests that in normal circumstances carers may demonstrate resilience and manage stress by appraising changes to their situation as they occur and respond by drawing on internal coping strategies and external resources (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) in the form of help, support and taking time for themselves. Indeed, carers who benefitted from both the reopening of formal dementia services (e.g. memory cafés, day support centres) and return of informal support experienced some lowering of burden and increased ability to cope (Savla et al, 2021). However, our findings showed an ongoing and long-lasting impact of external formal care services remaining closed and ongoing uncertainty as to when such services would re-open. The cumulative pressure of such uncertainty, alongside a lack of respite or assistance, increased the likelihood of harmful levels of stress, suggesting stress was not simply a challenge that could be overcome through positive reappraisal or a different response (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). In addition, carers experienced isolation due to continued caution around COVID-19 and/or the new normal of increased caring needs of the care recipient. Our evidence supports earlier findings predicting that the combination of advancing dementia with the evolving pandemic was likely to exacerbate carer stress, burden and feelings of isolation and abandonment (Bacsu et al, 2021; Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al, 2020; Cohen et al, 2020; Hanna et al, 2021; Zucca et al, 2021).

The carer experience was influenced by precarious dependence on the actions of others. Despite the fact that dementia carers often need more respite services than carers of people without dementia (Lee et al, 2022), our findings showed carers responded to the absence of formal respite by taking advantage of informal sources of support and information where possible. Although this was highly valued, there was a risk that stress could return when gains in networks and relationships during the pandemic were not available longer-term due to the return to pre-pandemic life for those people in newly developed support networks. A sense of abandonment and feeling of being left to cope alone had not improved from earlier stages of the pandemic (Giebel et al, 2021; Hanna et al, 2021; Pentecost et al, 2022; Zucca et al, 2021). Carers not receiving enough support appropriate to their need and situation, especially those caring for somebody with more advanced dementia, are likely to experience role overload, reduced health (Gaugler et al, 2003; Savla et al, 2021) or ‘burnout’ (Lilly et al, 2012). Indeed, a study conducted in New Zealand and Hong Kong identified personal characteristics similar to those of our cohort (being a spouse or partner, delivering more than 21 hours of care per week, and supporting those with basic daily care needs) as risk factors for burnout (Chan et al, 2021).

Even as restrictions had eased, in addition to increased caring demands, some carers also contended with challenges in meeting their own health, practical or financial needs caused by the delays, changes to, or closure of various usual services. Unfortunately, a shift from coping to not coping was evident in carers expressing doubt in their ability to care. Our data has indicated that stress accumulated and became unmanageable more quickly than may have been the case pre-pandemic.

Unfortunately, although at the time of our study restrictions had eased significantly, experiences of stress were similar to experiences of carers earlier in the pandemic, such as a decline in carer quality of life and wellbeing (Clare et al, 2022; Kürten et al, 2021), increased burden (Lethin et al, 2020; Lindt et al, 2020) and depression (Schoenmakers et al, 2010). We therefore echo the value of standardized needs assessments for carers to ensure effective support is provided quickly and efficiently and the risk of burnout is reduced (Chan et al, 2021).

Having access to certain health services provides some protection from carer burnout (Chan et al, 2021), and our study further supports the positive role dementia services bring to both the care recipient and carer (Hanna et al, 2021). However, our work indicated that the already fragmented receipt of post-diagnostic support for people with dementia and carers in England (van Horik et al., 2022) has likely become even more disparate during the pandemic, continuing to deteriorate after pandemic restrictions eased. Carers had few options in receiving externally delivered formal care services or home-delivered statutory care services. Although we did not set out to compare pre-pandemic and current experiences of formal services, carers’ accounts indicated they were finding the experience of using formal services very different. As seen in in our earlier interviews (O’Rourke et al., 2021; Pentecost et al., 2022), the offers of nurse visits or regular ‘checking in’ telephone calls that had started early in the pandemic from charities and volunteers became limited, or stopped. Therefore, opportunities to assess carers’ wellbeing were missed. Although volunteers are a valuable, cost-effective resource to help provide care for people with dementia (Malmedal et al, 2020; Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, 2015), the checking in services were a temporary measure at the start of the pandemic and were not sustainably funded. Our previous research recommended that with the absence of in-person health services, telephone contact would have been helpful (O’Rourke et al, 2021). The use of telephone consultations could be a valid alternative method of delivering proactive support for carers unable to see healthcare professionals in person (Waller et al, 2017) but evidence suggests more work is needed to ensure these are appropriate and well executed (Pentecost et al, 2022). Although telephone or online services can be beneficial they may not mitigate carer burnout for all, and it is important not to simply replace face-to-face services with telemedicine, as this can exacerbate inequalities in service provision (Tuijt et al, 2021). To improve support for carers of people with dementia, policymakers and service providers should recognise the longer term impact of the reduction in services and the need for appropriate funding

Limitations and strengths

This study has some limitations. Firstly, convenience sampling was employed using a relatively small pool of participants who had taken part in previous interviews reported in one of two studies (IDEAL-CDI or INCLUDE), limiting diversity in the sample. For example, the participants lived in suburban or urban settings and findings may not transfer straightforwardly to those living in rural areas. The pool was further restricted through attrition due to factors such as illness, not wanting to participate in further interviews or because the care recipient had moved into full time residential care, and this affected the availability of qualitative data at all previous timepoints for all participants. Secondly the extent of variability between and within individual experiences creates challenges for gaining a clear picture of change over time. We have attempted to identify some generalities and draw out implications that reflect the nature of the changing situation. Our previous quantitative data showed that, overall, carers believed they had coped very or fairly well during the pandemic (Quinn et al., 2022) and wellbeing and quality of life did not decline (Daley et al, 2022; Gamble et al, 2022). One reason may be that the quantitative measures used did not have sufficient discriminative capacity, or did not ask the right questions to identify subtle changes (Schoenmakers et al., 2010), thereby confirming the importance of also conducting qualitative interviews, especially over multiple time points, to tease out nuances in experience and provide a more contextualised picture. This is particularly relevant due to the evolving nature of the pandemic, with the recurring cycle of tightening and release from restrictions and local variation in restrictions due to infection rates.

These limitations are counterbalanced by the uniqueness of having a qualitative longitudinal aspect to explore carer experiences at different timeframes of the pandemic. We believe, to the best of our knowledge, this to be the only qualitative study that includes comparisons of carer experiences at different stages of the pandemic. Furthermore, we were able to compare and contrast findings from more in-depth interviews with quantitative data using the same cohort of participants. This created a valuable opportunity to understand the subtle experiences of carers of people with dementia.

Conclusions

This study has provided evidence about carer experiences approximately two years into the COVID-19 pandemic that could be compared with earlier qualitative interviews. As the UK population was being urged to ‘live with COVID-19’, this study highlights the position of carers, for whom the normal equilibrium of challenges and resources was unbalanced more quickly than would have been the case pre-pandemic. The lifting of restrictions and availability of a national vaccination programme approximately two years into the pandemic allowed for some return to pre-pandemic lifestyles but carers were still assessing ways to cope. Risks to coping primarily concerned the increased demands created by lack of support with the cognitive decline of the care recipient alongside reduced interaction with others due to ongoing COVID-19 fears, and changes to availability of formal care services and informal support networks. In addition, delays in the provision of practical, emotional, health or financial support for themselves compounded their ability to cope. Carer needs created by the pandemic were new, more extensive and ongoing, and there is thus a realistic danger of dementia carers reaching crisis point and burnout. To protect carers, and for caring in the community to be sustainable, carers would benefit from access to care advice, and to dementia groups and services and support suitable for different stages of the dementia journey. Carers would benefit from regular assessment of their individual support needs. This is not only essential for recovery post-pandemic but to protect the sustainability of carer support in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the IDEAL support of the following research networks: NIHR Dementias and Neurodegeneration Specialty (DeNDRoN) in England, the Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) and Health and Care Research Wales. We gratefully acknowledge the local principal investigators and researchers involved in IDEAL participant recruitment and assessment within these networks. We are grateful to the INCLUDE study participants for their participation in the study and to members of the ALWAYs group and the Project Advisory Group for their support throughout the study. LC and LA acknowledge support from the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South-West Peninsula.

Funding

‘Identifying and mitigating the individual and dyadic impact of COVID19 and life under physical distancing on people with dementia and carers (INCLUDE)’ was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through grant ES/V004964/1. Investigators: Clare, L., Victor, C., Matthews, F., Quinn, C., Hillman, A., Burns, A., Allan, L., Litherland, R., Martyr, A., Collins, P., & Pentecost, C. ESRC is part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life: living well with dementia. The IDEAL study’ was funded jointly by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) through grant ES/L001853/2. Investigators: L. Clare, I.R. Jones, C. Victor, J.V. Hindle, R.W. Jones, M. Knapp, M. Kopelman, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F.E. Matthews, R.G. Morris, S.M. Nelis, J.A. Pickett, C. Quinn, J. Rusted, J. Thom. ESRC is part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). ‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life: a longitudinal perspective on living well with dementia. The IDEAL-2 study’ is funded by Alzheimer’s Society, grant number 348, AS-PR2-16-001. Investigators: L. Clare, I.R. Jones, C. Victor, C. Ballard, A. Hillman, J.V. Hindle, J. Hughes, R.W. Jones, M. Knapp, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F.E. Matthews, R.G. Morris, S.M. Nelis, C. Quinn, J. Rusted. This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration South-West Peninsula. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the ESRC, UKRI, NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, the National Health Service, or Alzheimer’s Society. The support of ESRC, NIHR and Alzheimer’s Society is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Contributor Information

Rachel Collins, Email: R.A.Collins@exeter.ac.uk.

Eleanor Dawson, Email: E.Dawson@exeter.ac.uk.

Sally Stapley, Email: S.Stapley2@exeter.ac.uk.

Catherine Quinn, Email: c.quinn1@bradford.ac.uk.

Catherine Charlwood, Email: C.Charlwood@exeter.ac.uk.

Louise Allan, Email: L.Allan@exeter.ac.uk.

Christina Victor, Email: Christina.Victor@brunel.ac.uk.

Linda Clare, Email: l.clare@exeter.ac.uk.

Data access statement

IDEAL data were deposited with the UK data archive in April 2020. Details of how the data can be accessed after that date can be found here: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/854293

INCLUDE data were deposited with the UK data archive in June 2022 and will be available to access from July 2023. Details of how the data can be accessed after that date can be found here: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/855800/

References

- Altieri M, Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2021;29(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacsu JR, O’Connell ME, Webster C, Poole L, Wighton MB, Sivananthan S. A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2021;112(3):400–11. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00500-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Machado F, Barros D, Ribeiro Ó, Carvalho J. The effects of COVID-19 home confinement in dementia care: physical and cognitive decline, severe neuropsychiatric symptoms and increased caregiving burden. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2020;35 doi: 10.1177/1533317520976720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutoleau-Bretonnière C, Pouclet-Courtemanche H, Gillet A, Bernard A, Deruet AL, Gouraud I, Mazoue A, Lamy E, Rocher L, Kapogiannis D, El Haj M. The effects of confinement on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020;76:41–7. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Palumbo R, Di Domenico A, Vettor S, Pavan G, Borella E. Caring for people with dementia under COVID-19 restrictions: a pilot study on family caregivers. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2021;13:652833. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.652833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CY, Cheung G, Martinez-Ruiz A, Chau PYK, Wang K, Yeoh EK, Wong ELY. Caregiving burnout of community-dwelling people with dementia in Hong Kong and New Zealand: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02153-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Gamble LD, Martyr A, Sabatini S, Nelis SM, Quinn C, Pentecost C, Victor C, Jones RW, Jones IR, Knapp M, et al. ‘Living well’ trajectories among family caregivers of people with mild-to-moderate dementia in the IDEAL cohort. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2022;77(10):1852–1863. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Martyr A, Gamble LD, Pentecost C, Collins R, Dawson E, Hunt A, Parker S, Allan L, Burns A, Hillman A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on ‘Living Well’ with Mild-to-Moderate Dementia in the Community: Findings from the IDEAL Cohort. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2022;85(2):925–940. doi: 10.3233/JAD-215095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Wu Y-T, Quinn C, Jones IR, Victor CR, Nelis SM, Martyr A, Litherland R, Pickett JA, Hindle JV, Jones RW, et al. A comprehensive model of factors associated with capability to “Live Well” for family caregivers of people living with mild-to-moderate dementia: findings from the IDEAL study. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2019;33(1):29–35. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Russo MJ, Campos JA, Allegri RF. Living with dementia: increased level of caregiver stress in times of COVID-19. International Psychogeriatrics. 2020;32(11):1377–81. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley S, Farina N, Hughes L, Armsby E, Akarsu N, Pooley J, Towson G, Feeney Y, Tabet N, Fine B, Banerjee S. Covid-19 and the quality of life of people with dementia and their carers—the TFD-C19 study. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0262475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Simões-Neto JP, Santos RL, Sousa MFBd, Baptista MAT, Lacerda IB, Kimura NRS, Dourado MCN. Caregivers’ resilience is independent from the clinical symptoms of dementia. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. 2016;74:967–973. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20160162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble L, Parker S, Quinn C, Bennett H, Martyr S, Sabatini S, Pentecost C, Collins R, Dawson E, Hunt A, Allan L, et al. A comparison of well-being of carers of people with dementia and their ability to manage before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the IDEAL study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2022;88(2):679–692. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Jarrott SE, Zarit SH, Stephens M-AP, Townsend A, Greene R. Adult day service use and reductions in caregiving hours: effects on stress and psychological wellbeing for dementia caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;18(1):55–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel C, Cannon J, Hanna K, Butchard S, Eley R, Gaughan A, Komuravelli A, Shenton J, Callaghan S, Tetlow H, Limbert S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: a qualitative study. Aging and Mental Health. 2021;25(7):1281–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1822292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Casanova JM, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(5):e19434. doi: 10.2196/19434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna K, Giebel C, Tetlow H, Ward K, Shenton J, Cannon J, Komuravelli A, Gaughan A, Eley R, Rogers C, Rajagopal M, et al. Emotional and mental wellbeing following COVID-19 public health measures on people living with dementia and carers. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2021;35(3):344–352. doi: 10.1177/0891988721996816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Woodward M, Mioshi E. Social support and high resilient coping in carers of people with dementia. Geriatric Nursing. 2019;40(6):584–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki AE, Koukouli S, Panagiotakis S, Tziraki C. Resilience in a Greek sample of informal dementia caregivers: familism as a culture-Ssecific factor. The Journal of Frailty & Aging. 2022;11 doi: 10.14283/jfa.2022.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh ZY, Law F, Chew J, Ali N, Lim WS. Impact of coronavirus disease on persons with dementia and their caregivers: an audit study. Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research. 2020;24(4):316–20. doi: 10.4235/agmr.20.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kürten L, Dietzel N, Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Graessel E. Predictors of the one-year-change in depressiveness in informal caregivers of community-dwelling people with dementia. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara B, Carnes A, Dakterzada F, Benitez I, Piñol-Ripoll G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish patients with Alzheimer’s disease during the COVID-19 lockdown. European Journal of Neurology. 2020;27(9):1744–7. doi: 10.1111/ene.14339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Choi W, Park MS. Respite service use among dementia and nondementia caregivers: findings from the National Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 Survey. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2022;41(6):1557–67. doi: 10.1177/07334648221075620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethin C, Leino-Kilpi H, Bleijlevens MH, Stephan A, Martin MS, Nilsson K, Nilsson C, Zabalegui A, Karlsson S. Predicting caregiver burden in informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home – A follow-up cohort study. Dementia. 2020;19(3):640–60. doi: 10.1177/1471301218782502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MB, Robinson CA, Holtzman S, Bottorff JL. Can we move beyond burden and burnout to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia? Evidence from British Columbia, Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2012;20(1):103–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, Guerreiro M, Rosa MM. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care. 2020:bmjspcare-2020-002242. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindt N, van Berkel J, Mulder BC. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litherland R, Burton, Cheeseman M, Campbell D, Hawkins M, Hawkins T, Oliver K, Scott D, Ward J, Nelis SM, Quinn C, et al. Reflections on PPI from the ‘action on living well: Asking you’ advisory network of people with dementia and carers as part of the IDEAL study. Dementia. 2018;17(8):1035–1044. doi: 10.1177/1471301218789309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Vara-García C, Romero-Moreno R, Barrera-Caballero S, Pedroso-Chaparro MdS, Jiménez-Gonzalo L, Fernandes-Pires J, Cabrera I, Gallego-Alberto L, Huertas-Domingo C, Mérida-Herrera L, et al. Caring for relatives with dementia in times of COVID-19: impact on caregivers and care-recipients. Clinical Gerontologist. 2022;45(1):71–85. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2021.1928356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmedal W, Steinsheim G, Nordtug B, Blindheim K, Alnes RE, Moe A. How volunteers contribute to persons with dementia coping in everyday life. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2020;13:309–19. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S241246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson-Algar P, Allen MC, Hyde M, Keating N, Windle G. Exploring the impact of Covid-19 on the care and quality of life of people with dementia and their carers: A scoping review. Dementia. 2022;21(2):648–76. doi: 10.1177/14713012211053971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti R, Caruso P, Giuffré M, Tiribelli C. COVID-19 lockdown effect on not institutionalized patients with dementia and caregivers. Healthcare. 2021;9(7):893. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9070893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Services. NMoHaC; 2015. Demensplan 2020. Et mer demensvennlig samfunn, (The Norwegian Dementia Plan. A more dementia-friendly society) 2015. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/3bbec72c19a04af88fa78ffb02a203da/dementia_-plan_2020_long.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke G, Pentecost C, van den Heuvel E, Victor C, Quinn C, Hillman A, Litherland R, Clare L. Living with dementia under COVID-19 restrictions: coping and support needs among people with dementia and carers from the IDEAL cohort. Ageing and Society. 2021:1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21001719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panerai S, Prestianni G, Musso S, Muratore S, Tasca D, Catania V, Gelardi D, Ferri R. The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the neurobehavioral manifestations of people with Major Neurocognitive Disorder and on the level of burden of their caregivers. Life Span and Disability. 2020;23(2):303–20. http://www.lifespanjournal.it/Client/rivista/ENG102_Full%20Issue_Life%20Span%20and%20Disability_XXIII-2_2020.pdf#page=139 . [Google Scholar]

- Pentecost C, Collins R, Stapley S, Victor C, Quinn C, Hillman A, Litherland R, Allan L, Clare L. Effects of social restrictions on people with dementia and carers during the pre-vaccine phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of IDEAL cohort participants. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2022;30:e4594–e4604. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan A, Daly L, Byrne M, Dunne N. Exploring experiences of carers in the Covid 19 pandemic. Trinity Centre for Practice and Healthcare Innovation, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College; Dublin: 2022. pp. 1–135. https://www.tcd.ie/tcphi/assets/pdf/exploring-experiences-of-carers.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Pongan E, Dorey JM, Borg C, Getenet JC, Bachelet R, Lourioux C, Laurent B, Rey R, Rouch I. COVID-19: Association between increase of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia during lockdown and caregivers’ poor mental health. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021;80(4):1713–21. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Gamble LD, Parker S, Martyr A, Collins R, Victor C, Dawson E, Hunt A, Pentecost C, Allan L, Clare L. Impact of COVID-19 on carers of people with dementia in the community: Findings from the British IDEAL cohort. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2022;37(5) doi: 10.1002/gps.5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Nelis SM, Martyr A, Victor C, Morris RG, Clare L. Influence of positive and negative dimensions of dementia caregiving on caregiver well-being and satisfaction with life: findings from the IDEAL study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019;27(8):838–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Toms G. Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers’ well-being: a systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2018;59(5):e584–96. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach P, Zwiers A, Cox E, Fischer K, Charlton A, Josephson CB, Patten SB, Seitz D, Ismail Z, Smith EE. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being and virtual care for people living with dementia and care partners living in the community. Dementia. 2021;20(6):2007–23. doi: 10.1177/1471301220977639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(8):793–806. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S, Bennett HQ, Martyr A, Collins R, Gamble LD, Matthews FE, Pentecost C, Dawson E, Hunt A, Parker S, Allan L, et al. Minimal impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of people living with dementia: analysis of matched longitudinal data from the IDEAL study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.849808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla J, Roberto KA, Blieszner R, McCann BR, Hoyt E, Knight AL. Dementia caregiving during the “stay-at-home” phase of COVID-19 pandemic. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2021;76(4):e241–5. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, DeLepeleire J. Supporting the dementia family caregiver: The effect of home care intervention on general well-being. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(1):44–56. doi: 10.1080/13607860902845533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram V, Jenkinson C, Peters M. Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on carers of persons with dementia in the UK: a qualitative study. Age and Ageing. 2021;50(6):1876–85. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley S, Pentecost C, Collins R, Quinn C, Dawson E, Thom J, Clare L. ‘Caring beyond capacity’ during the coronavirus pandemic: resiliance and family carers of people with dementia from the IDEAL cohort. International Journal of Care and Caring. 2023:1–18. doi: 10.1332/239788221X16819328227036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A, Papatriantafyllou JD, Yiannopoulou K, Sali D, Kalligerou F, Ntanasi E, Zoi P, Margioti E, Kamtsadeli V, Hatzopoulou M, Koustimpi M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with mild cognitive impairment/dementia and on their caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2021;36(4):583–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuijt R, Rait G, Frost R, Wilcock J, Manthorpe J, Walters K. Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of people living with dementia and their carers. British Journal of General Practice. 2021;71(709):e574–82. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2020.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Horik JO, Collins R, Martyr A, Henderson C, Jones RW, Knapp M, Quinn C, Thom JM, Victor C, Clare L, on behalf of the IDEAL programme Limited receipt of support services among people with mild-to-moderate dementia: Findings from the IDEAL cohort. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2022;37(3) doi: 10.1002/gps.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller A, Dilworth S, Mansfield E, Sanson-Fisher R. Computer and telephone delivered interventions to support caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review of research output and quality. BMC Geriatrics. 2017;17(1):265. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0654-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucca M, Isella V, Lorenzo RD, Marra C, Cagnin A, Cupidi C, Bonanni L, Laganà V, Rubino E, Vanacore N, Agosta F, et al. Being the family caregiver of a patient with dementia during the Coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown [original research] Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2021;13 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.653533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

IDEAL data were deposited with the UK data archive in April 2020. Details of how the data can be accessed after that date can be found here: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/854293

INCLUDE data were deposited with the UK data archive in June 2022 and will be available to access from July 2023. Details of how the data can be accessed after that date can be found here: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/855800/