Abstract

Objectives

In bipolar disorder (BD), dysregulation of mood may result from white matter abnormalities that disrupt fronto-subcortical circuits. In this study, we explore such abnormalities using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), an imaging technique capable of detecting subtle changes not visible with conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and voxel-based analysis.

Methods

Thirty-six patients with BD, all but two receiving antidepressants or mood stabilizers, and 28 healthy controls matched for age and gender were studied. Diffusion-weighted echoplanar images (DW-EPI) were obtained using a 1.5T scanner. Voxel-based analysis was performed using SPM 2. Differences between the groups in mean diffusivity and fractional anisotropy (FA) were explored.

Results

In the patient group, mean diffusivity was increased in the right posterior frontal and bilateral prefrontal white matter, while FA was decreased [corrected] in the inferior, middle temporal and middle occipital regions. The areas of increased mean diffusivity overlapped with those previously found to be abnormal using volumetric MRI and magnetization transfer imaging (MTI) in the same group of patients.

Conclusions

White matter abnormalities, predominantly in the fronto-temporal regions, can be detected in patients with BD using DTI. The neuropathology of these abnormalities is uncertain, but neuronal and axonal loss, myelin abnormalities and alterations in axonal packing density are likely to be relevant. The neuroprotective effects of some antidepressants and mood stabilizers make it unlikely that medication effects could explain the abnormalities described here, although minor effects cannot be excluded.

Changes in brain structure, both macro- and microscopic, are well established in bipolar disorder (BD) (1) and those in the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex have been particularly well documented. Thus, reduction in the number and density of glial cells (2, 3) and decreased synaptic markers (4) in the subgenual region of the anterior cingulate have been reported, together with decreased neuronal density in orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (5–7). Functional imaging studies have also shown abnormal activation of the subgenual prefrontal cortex during manic and depressive episodes (8) and volume reduction in the same area has been reported in chronic (9), first-episode familial BD patients (10) and in individuals at risk for BD (11–13). White matter abnormalities have also been described in BD, in particular, hyperintensities detected in T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (14–16). The presence of these hyperintense lesions appears to be age related (17), associated with a later disease onset (18, 19), and more common in those with treatment-resistant disease (19, 20) or cognitive impairment (21). Although the neuropathology of these white matter lesions remains uncertain, punctate lesions deep in the white matter may represent microvascular abnormalities, while those closer to the ventricles are more likely to reflect myelin changes (20). Ventricular enlargement described in early papers is also an indirect indication of possible white matter loss (22, 23), and some recent volumetric studies (24), but not others (25), have reported predominantly, but not exclusively, prefrontal white matter loss. Myelin abnormalities in mood disorders are suggested by reports (26) of decreased expression of genes involved in myelin synthesis and regulation, in particular the SOX10 gene encoding a transcription factor that regulates other myelin-related genes.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a modality of MRI that measures the rate and directionality of microscopic water diffusion (27), is capable of detecting subtle white matter abnormalities before volume loss becomes apparent, and in patients with multiple sclerosis DTI has proved capable of detecting changes in the normal-appearing white matter that are not visible in conventional MRI (28, 29). The pathological abnormalities underlying changes in diffusion are not fully understood, but are likely to reflect changes in fiber density, diameter and alignment, and myelin, which are the main barriers to water diffusion in the brain. Diffusion tensor imaging has been used to study patients with schizophrenia [see (30) for a review], and a few small studies have also investigated patients with BD. These studies have measured changes in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) or in fractional anisotropy (FA), an index that reflects the preferential diffusion of water along, rather than across, axons (i.e., anisotropic diffusion) in regions of interest (ROIs) placed within the white matter. In late-life depression, reduced FA has been reported in right superior frontal (31) and bilateral frontotemporal white matter correlated with the severity of symptoms (32) and with treatment response (33). In BD, focal reduction in FA, with normal ADC, in ROIs placed 25 mm and 30 mm above the anterior cingulate has been reported in a group of nine patients compared to controls (34). The reduced FA was interpreted as indicating changes in the coherence of white matter tracts, while the concomitant normal ADC was seen as indicating axonal preservation. The same group (35) later reported a similar finding in 11 medication-free adolescents during their first manic episode. Others (36), by contrast, have reported frontal and parietal increases in ADC in BD patients compared to neurological controls. Other investigators (37) have reported a simultaneous increase in anisotropy in the anterior frontal white matter and a reduction in the fronto-thalamic and fronto-pontine connections in the same group of BD patients.

We present here a study of patients with BD using DTI and voxel-based analysis that allows whole-brain exploration and therefore avoids the limitations of ROI-based methodologies. This exploratory approach is particularly suited to the study of psychiatric disease, where it is often difficult to predict a priori the location of abnormalities. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using these techniques in BD. The subjects reported here had also participated in a study using volumetric MRI and magnetization transfer imaging (MTI) (38), and the results of this study are set in the context of our previous findings.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-six patients (13 males, 23 females) with BD and a mean age of 39 years (range 21–63 years) were included in the study. Twenty-five patients met a DSM-IV diagnosis for bipolar I disorder [(BDI) (10 males, 15 females; mean age 37.4)] and 11 for bipolar II disorder [(BDII) (3 males, 8 females; mean age 42.8)]. Patients were recruited from outpatient clinics in inner London psychiatric hospitals (n = 25) and from responders to an advertisement placed in the journal of the Manic-Depressive Fellowship (n = 11). Subjects with comorbid psychiatric conditions, history of neurological or systemic disease, head injury leading to unconsciousness or substance abuse were excluded.

Two patients were not receiving medication at the time of the study and information about medication was incomplete for four patients. The rest were receiving mood stabilizers (23 lithium, 3 sodium valproate, 4 carbamazepine, 3 lamotrigine) and/or antidepressants (11 patients) and neuroleptics (9 patients). Five patients had received electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the past.

A total of 28 imaging controls were chosen to match the patients in age and gender from a pool of healthy volunteers recruited at the Institute of Neurology. The study was approved by the relevant ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical assessment

All patients were interviewed by a trained psychiatrist (SB) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (39). Information was collected about developmental milestones, education and employment, substance misuse, medical history, duration of illness, number of hospital admissions, medication, exposure to ECT and family history of psychiatric illness. All patients met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder. The reported mean length of illness was 13.8 years (range 1–32 years) and the number of episodes of illness ranged from 1 to 35.

Image acquisition

All subjects were scanned on a GE Signa 1.5 Tesla scanner (General Electric Company, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a standard quadrature head coil. A sagittal localizing scan was acquired. Diffusion-weighted echo planar images (DW-EPI) were acquired in the axial plane (TE = 78 ms, 96 × 96 matrix, field of view 24 × 24 cm, slice thickness 5 mm). Gradients for diffusion sensitization were applied in seven non-collinear directions. Each direction was sampled using four gradient strengths corresponding to b values of 0−700 s/mm2 (where higher b values correspond to heavier diffusion weighting). Images were acquired in three sets of interleaved slices. Five acquisitions of each set were performed and averaged after magnitude reconstruction, improving signal to noise. Image acquisition was cardiac gated with a peripheral pulse oximeter.

All images were transferred to an independent workstation (Sun Sparcstation; Sun Microsystems Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Diffusion-weighted EPIs were first corrected for geometric distortion induced by eddy currents and for involuntary motion using affine co-registration (40). The diffusion tensor was estimated using a multivariate linear regression model (27), and mean diffusivity and FA maps were derived. The voxel-based analysis of these maps was performed in SPM2 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, version 2) (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). First, each subject’s b0 image (which is T2-weighted) was co-registered with the T2-weighted EPI template in SPM using a combination of linear and nonlinear functions (41), and the normalization parameters were applied to the corresponding FA maps. Next, all the co-registered FA images were averaged and smoothed with an 8-mm Gaussian kernel to create a customized FA template. Finally, each individual’s FA map was normalized onto the FA template. This iterative procedure was performed to improve the intersubject alignment of white matter structures, as FA maps are characterized by a better white-to-gray matter contrast than the b0 images. The same normalization parameters were retrospectively applied to the mean diffusivity maps and to the b0 images. The latter were then segmented to produce probability maps of white matter, gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in normalized space. Images of CSF were ‘modulated’ during normalization (i.e., every voxel intensity was multiplied by the jacobian of the transformation to compensate for nonlinear effects). Modulation was not used with FA and mean diffusivity images, as these are absolute quantities that we aimed to measure directly. Normalized images of FA, mean diffusivity and CSF probability (an index of CSF volume) were smoothed to 15 mm using a full-width half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter, which is of comparable size to the smoothing kernels used for the analysis of MTI and white matter density in our previous study (38).

Statistical analysis

T-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare demographic variables. A group comparison of BD patients and healthy control subjects was performed in SPM2 with the model ‘compare-populations: one scan/subject’. The analysis is based on the general linear model and the theory of Gaussian random fields (42), testing voxel-by-voxel the null hypothesis that the average mean diffusivity and FA are the same in patients and controls. This analysis is equivalent to a voxel-by-voxel two-sample t-test. The Gaussian random field’s theory provides a model for correcting for multiple comparisons (family-wise error correction) alternative to the Bonferroni correction.

Since mean diffusivity can be affected by partial volume with CSF, we performed a post hoc analysis of the areas, which were identified as significantly different from controls using SPM2. We measured the average mean diffusivity (or FA) and mean CSF probability obtained from the modulated images (range 0–1) for each cluster and then ran a multiple linear regression using the average mean diffusivity (or FA) as the dependent variable, and CSF probability and subject status (i.e., patient or control) as covariates. This analysis, which effectively investigates if the differences in DTI indices could simply be explained by local CSF distribution, was performed in STATA (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). Using the same package, we also investigated the association between the mean cluster mean diffusivity (or FA) and age, number of admissions, and disease duration.

Results

There were no significant age or gender differences between patients and control subjects.

Mean diffusivity

In BD patients, a significant increase in mean diffusivity was observed at cluster level (p < 0.05), after correction for multiple comparisons using family-wise error correction, in bilateral prefrontal white matter (peak coordinates [−20 30 60] and [18 28 8]) and in the right posterior frontal white matter (peak coordinates [16 −26 26]) (Fig. 1). The anatomical localization of the clusters was determined in SPM using the Talairach Space Utility tool (http://www.ihb.spb.ru/pet_lab/TSU/TSUMain.html). The bilateral prefrontal areas of increased mean diffusivity involved the anterior part of the fronto-occipital fasciculus, a bundle of association fibers projecting to the frontal and parietal lobes from occipital regions. The right posterior frontal area of increased mean diffusivity also involved the posterior segment of the fronto-occipital fasciculus and included part of the corpus callosum. The prefrontal areas of increased mean diffusivity overlap with those showing a decrease in white matter density previously reported using voxel-based morphometry in the same group of patients (38) (Fig. 2). There were no areas of increased mean diffusivity in controls when compared to bipolar patients.

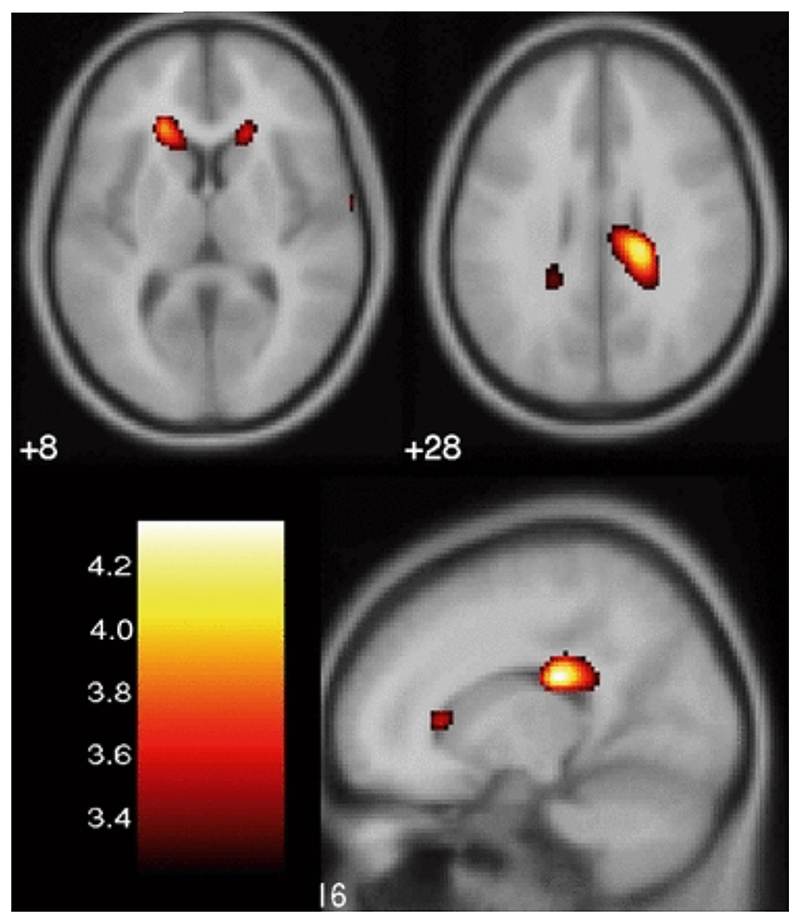

Figure 1.

Areas of increased mean diffusivity in bilateral prefrontal white matter, right posterior cingulate gyrus and subgyral white matter in bipolar disorder patients compared to healthy control subjects, projected on T1-weighted averaged images.

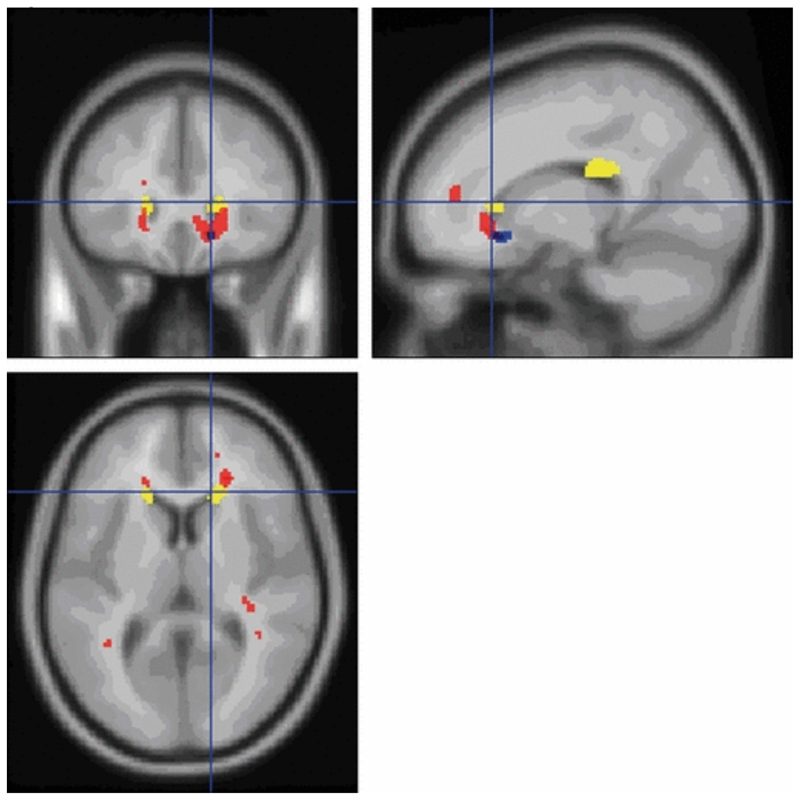

Figure 2.

Areas of structural brain change in bipolar disorder patients compared to healthy control subjects identified with mean diffusivity from diffusion tensor imaging (yellow), white matter density from voxel-based morphometry (red) and magnetization transfer imaging (blue), projected on T1-weighted averaged images.

Areas of increased mean diffusivity in bilateral prefrontal white matter, right posterior cingulate gyrus and subgyral white matter in bipolar disorder patients compared to healthy control subjects, projected on T1-weighted averaged images.

Fractional anisotropy

In the BD group, FA was significantly decreased at voxel level (p = 0.04, after familywise error correction for multiple comparisons) in an area with peak coordinates [42 −70 −2]. Using the same localization tool, this area was found to be located at the junction of the inferior and middle temporal gyri and to incorporate part of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus. The area of reduced FA is shown in Fig. 3. There were no areas of decreased FA in controls compared to bipolar patients.

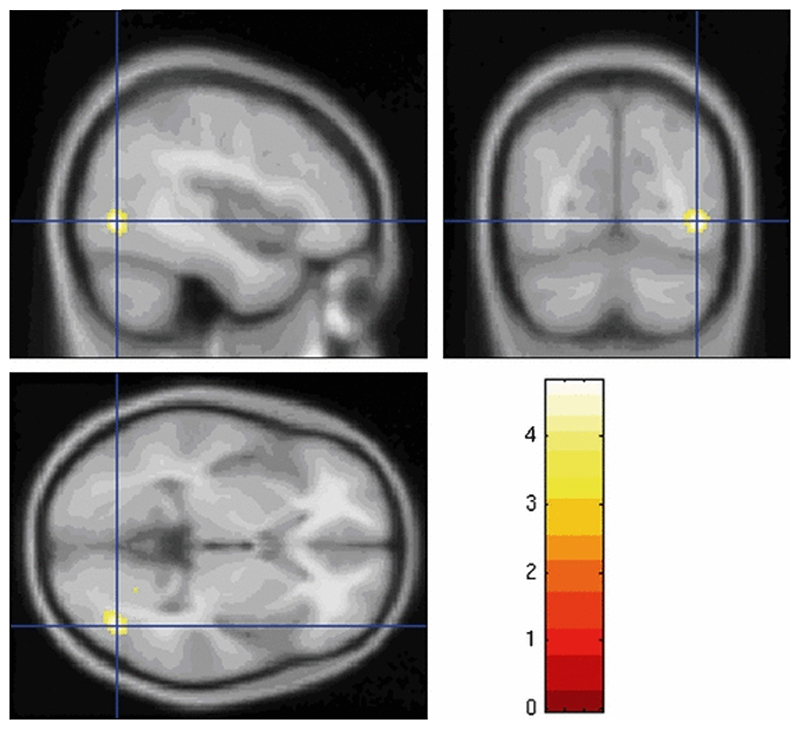

Figure 3.

Area of decreased fractional anisotropy extending over inferior and middle temporal gyri and middle occipital gyrus in bipolar disorder patients compared to healthy control subjects, projected on T1-weighted averaged images.

Post hoc analysis

A post hoc analysis was performed to explore the influence of each cluster mean CSF probability in explaining the group differences in mean diffusivity and FA. Mean diffusivity. In the right posterior frontal white matter [average mean diffusivity 1.38 (SD = 0.04) × 10−3 mm2/s for controls and 1.61 (SD = 0.04) × 10−3 mm2/s for patients] the cluster CSF probability was a significant covariate [coefficient 0.37, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.20–0.47] but subject status remained significant after adjusting for CSF volume (coefficient = 0.12, p = 0.005, 95% CI = 0.04–0.21). In the left prefrontal white matter the cluster CSF probability was not significantly associated (p = 0.178) with the average mean diffusivity [1.10 (SD = 0.02) × 10−3 mm2/s for controls and 1.25 (SD = 0.03) × 10−3 mm2/s for patients], while the subject status was (coefficient 0.16, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.08–0.25). The opposite was true for the right prefrontal white matter [average mean diffusivity = 1.04 (SD = 0.03) × 10−3 mm2/s for controls and 1.18 (SD = 0.03) × 10−3 mm2/s for patients], where the subject status was no longer significant (p = 0.39) when adjusting for CSF probability (coefficient = 0.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.28–0.40). Fractional anisotropy. In the temporo-occipital cluster [average FA 0.317 (SD = 0.03) for controls and 0.288 (SD = 0.02) for patients], CSF probability was not a significant covariate (p = 0.9) and subject status remained significant (p < 0.001) after adjusting for it.

There was no significant correlation between average mean diffusivity and age, number of admissions and disease duration. There was a significant inverse correlation (coefficient = − 0.35, p < 0.045) between average FA and age but not duration of illness or number of hospital admissions.

Discussion

Our results suggest that white matter abnormalities are present in prefrontal, frontal and temporal white matter in patients with BD and that these abnormalities involve major intrahemispheric and interhemispheric association fibers. These results, in a sample larger than those previously reported, are in keeping with those of other studies that have analyzed DTI using ROI methodologies. Thus, FA has been found to be reduced in the prefrontal regions in BD patients and in superior frontal white matter tracts in medication-naïve adolescents in their first episode of mania (34, 35). Increased mean diffusivity has also been found in orbito-frontal white matter (43) and other investigators (36) described similar findings in severe, treatment-resistant BD patients with psychotic features. The white matter changes described here are likely to represent the anatomical abnormalities responsible for the disruption of fronto-subcortical circuits that modulate anterior limbic structures (44) and that result in mood dysregulation and cognitive changes, in particular deficits in executive function and memory previously described in the same group of patients (45). Our results are also in keeping with those of McDonald et al. (46), who found volume loss in the anterior corpus callosum, and bilateral frontal and tempo-parietal regions to be associated with increased risk for BD, while abnormalities in the left superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi represent a risk factor common to BD and schizophrenia.

In our previous study (38) using the same subjects, decreased white matter density was detected in the same posterior temporal areas of decreased FA. Studies using proton spectroscopy (47) and conventional MRI (48) have also reported changes in this location, and a functional imaging study (49) has suggested that reduced activation in higher-order visuoperceptual areas, including the superior temporal sulcus, and occipital cortex may indicate disturbances in affect-processing circuitry, leading to abnormalities of mood and social cognition.

Based on the pattern of DTI changes, some studies (34, 35) have tried to specify the most likely pathological process, but these attempts should be interpreted with caution. Using a voxel-based analysis, which allows the simultaneous exploration of all white matter regions, we also found dissociation between the areas with increased mean diffusivity (prefrontal and posterior cingulate gyrus) and those with reduced FA (inferior and middle temporal and occipital gyri). The loss of resolution for small structures, inherent to voxel-based methods, is the most likely explanation for this discrepancy, as subtle changes in mean diffusivity and FA may have been overlooked.

In our previous study of the same patient cohort (38), we found abnormalities in overlapping prefrontal areas using different imaging modalities (MTI and volumetric imaging), and this may give us some advantage over single-modality imaging studies in interpreting our DTI findings. Thus, although loss of brain volume contributes to DTI changes, especially in the right prefrontal region, it is also clear that DTI and MTI are capable of detecting abnormalities that had not resulted in brain atrophy. Neuronal and axonal loss and myelin abnormalities are known to increase mean diffusivity, while alterations in axonal packing density and coherence of fiber alignment can influence the directionality of diffusion as measured by FA (50). Changes in the magnetization transfer signal depend on macromolecular density of cell membranes and phospholipids, and MTR reductions in the white matter are likely to be due to changes in myelin and/or axonal density. The overlap between the abnormalities detected by these two imaging modalities suggests, therefore, that neuronal and dendritic changes, together with myelin abnormalities, are likely to coexist in BD. This is in keeping with the reported decreases in neuronal (5–7), glial (2, 3) and synaptic (4) markers and in myelin expression (26) in BD.

Despite the difficulties in interpreting DTI changes, the use of this technique has clear advantages over conventional imaging, as has already been demonstrated in multiple sclerosis (28, 29), where DTI changes are present in the normal-appearing white matter. The possible effects of medication on our results cannot be entirely discounted, although there is no evidence to suggest that antidepressants cause neuropathological abnormalities that could account for changes in water diffusion, and the same applies to ECT (51). In BD patients receiving lithium, increases in gray matter volume (52) and density (53) have been reported, together with increases in the neuronal marker N-acetyl-aspartate (54) in cortical areas relating to emotional control. Therefore, the potential neuroprotective effects of lithium and other mood stabilizers make it unlikely that the white matter abnormalities described here could be attributed to them.

It remains to be determined whether these white matter abnormalities are neurodevelopmental in origin and static and represent a genetic vulnerability for the disorder, or whether they are the result of ongoing pathological processes such as glutamatergic excitotoxicity related to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation (55). The lack of significant correlations between DTI abnormalities, age and indices of disease severity in our study may favor the first of these two possibilities.

The sequence used for the acquisition of DTI data in our study could be considered suboptimal compared to those currently available, and our study would have benefited from using thinner and higher-resolution images to minimize the risk of partial volume effects and to facilitate normalization to standard space. We tried to overcome these shortcomings by performing a post hoc analysis that confirmed that, in at least two of the abnormal areas identified by voxel-based analysis, the changes in mean diffusivity were not merely the result of ventricular enlargement.

Another potential limitation of this study is the use of voxel-based analysis, which may have obscured the differences between patients and controls (56–59), although this methodology also offers the possibility of detecting abnormalities without an a priori hypothesis. On the other hand, we feel that our study has two main advantages over previous studies: first, it has a larger patient sample, and, second, it allows for the convergence of findings from three different structural imaging modalities (DTI, MTI and voxel-based morphometry), which adds credence to the presence of abnormalities in white matter tracts in BD likely to be relevant in the causation of affective symptoms and cognitive impairment. The use of this type of analysis for DTI data is controversial (58), particularly with respect to FA that is not likely to be normally distributed. This is particularly relevant to areas where partial volume effect is likely to occur. The abnormalities we found are mainly located at tissue boundaries, and we cannot completely exclude the possibility that our results may be an artifact. We tried to address this problem by performing a post hoc analysis, adjusting our results for local CSF volume. Our results need to be confirmed by future studies using recently introduced image analysis specifically designed for DTI data (60) and/or non-parametric statistical approaches.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the subjects who took part in the study and the members of the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Unit at the Institute of Neurology. SB was supported by the Brain Research Trust and MC by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Harrison PJ. The neuropathology of primary mood disorder. Brain. 2002;125:1428–1449. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ongur D, Drevets WC, Price JL. Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13290–13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster MJ, OÕGrady J, Kleinman JE, Weickert CS. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mRNA levels in the cingulate cortex of individuals with depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2005;133:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ. Synaptic pathology in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorders. A review and a Western blot study of synaptophysin, GAP-43 and the complexins. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouras C, Kovari E, Hof PR, Riederer BM, Giannakopoulos P. Anterior cingulate cortex pathology in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;102:373–379. doi: 10.1007/s004010100392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkowska G, Halaris A, Selemon LD. Reductions in neuronal and glial density characterize the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter D, Mackay D, Chana G, Beasley C, Landau S, Everall IP. Reduced neuronal size and glial cell density in area 9 of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in subjects with major depressive disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:386–394. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drevets WC. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:813–829. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR, Jr, et al. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–827. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirayasu Y, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. Subgenual cingulate cortex volume in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1091–1093. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickstein DP, Treland JE, Snow J, et al. Neuropsychological performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gourovitch ML, Torrey EF, Gold JM, Randolph C, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE. Neuropsychological performance of monozygotic twins discordant for bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:639–646. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keri S, Kelemen O, Benedek G, Janka Z. Different trait markers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a neuro-cognitive approach. Psychol Med. 2001;31:915–922. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupont RM, Jernigan TL, Gillin JC, Butters N, Delis DC, Hesselink JR. Subcortical signal hyperintensities in bipolar patients detected by MRI. Psychiatry Res. 1987;21:357–358. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(87)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn KH, Lyoo IK, Lee HK, et al. White matter hyperintensities in subjects with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:516–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Badri SM, Cousins DA, Parker S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in young euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:81–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sassi RB, Brambilla P, Nicoletti M, et al. White matter hyperintensities in bipolar and unipolar patients with relatively mild-to-moderate illness severity. J Affect Disord. 2003;77:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupont RM, Jernigan TL, Butters N, et al. Subcortical abnormalities detected in bipolar affective disorder using magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical and neuropsychological significance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:55–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810130057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickie I, Scott E, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Austin MP, Bennett B. Subcortical hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlates and prognostic significance in patients with severe depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore PB, Shepherd DJ, Eccleston D, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions in bipolar affective disorder: relationship to outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:172–176. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont RM, Butters N, Schafer K, Wilson T, Hesselink J, Gillin JC. Diagnostic specificity of focal white matter abnormalities in bipolar and unipolar mood disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:482–486. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00100-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkis H, Friedman L, Wise A, Meltzer HY. Meta-analysesof studies of ventricular enlargement and cortical sulcal prominence in mood disorders. Comparisons with controls or patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:735–746. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950210029008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Sax KW, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging of structural abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:254–260. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald C, Bullmore E, Sham P, et al. Regional volume deviations of brain structure in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder: computational morphometry study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:369–377. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Larson MP, DelBello MP, Zimmerman ME, Schwiers ML, Strakowski SM. Regional prefrontal gray and white matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aston C, Jiang L, Sokolov BP. Transcriptional profiling reveals evidence for signaling and oligodendroglial abnormalities in the temporal cortex from patients with major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:309–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werring DJ, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Diffusion tensor imaging of lesions and normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1999;52:1626–1632. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rovaris M, Filippi M. MR-based technology for in vivo detection, characterization, and quantification of pathol ogy of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39:243–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanaan RA, Kim JS, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD, Barker GJ, McGuire PK. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor WD, MacFall JR, Payne ME, et al. Late-life depression and microstructural abnormalities in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex white matter. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1293–1296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nobuhara G, Okugawa G, Sugimoto T, et al. Frontal white matter anisotropy and symptom severity of late-life depression: a magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:120–122. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.055129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Choi SJ, Murphy CF, Lim KO. Frontal white matter microstructure and treatment response of late-life depression: a preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1929–1932. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adler CM, Holland SK, Schmithorst V, et al. Abnormal frontal white matter tracts in bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler CM, Adams J, DelBello MP, et al. Evidence of white matter pathology in bipolar disorder adolescents experiencing their first episode of mania: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:322–324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Regenold WT, DÕAgostino CA, Ramesh N, Hasnain M, Roys S, Gullapalli RP. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of white matter in bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:188–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haznedar MM, Roversi F, Pallanti S, et al. Fronto-thalamo-striatal gray and white matter volumes and anisotropy of their connections in bipolar spectrum illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruno SD, Barker GJ, Cercignani M, Symms M, Ron MA. A study of bipolar disorder using magnetization transfer imaging and voxel-based morphometry. Brain. 2004;127:2433–2440. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RC, Williams JBW, Benja-min LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research version, patient edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods RP, Grafton ST, Holmes CJ, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: I. General methods and intrasubject, intramodality validation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:139–152. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashburner J, Neelin P, Collins DL, Evans A, Friston K. Incorporating prior knowledge into image registration. Neuroimage. 1997;6:344–352. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P. A 3-dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:900–918. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beyer JL, Taylor WD, MacFall JR, et al. Cortical white matter microstructural abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2225–2229. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:105–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Summers M, Papadopoulou K, Bruno S, Cipolotti L, Ron MA. Bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: cognition and emotion processing. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1799–1809. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald C, Bullmore ET, Sham PC, et al. Association of genetic risks for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with specific and generic brain structural endophenotypes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:974–984. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhagwagar Z, Wylezinska M, Jezzard P, et al. Reduction in occipital cortex gamma-aminobutyric acid concentrations Diffusion tensor imaging in bipolar disorder in medication-free recovered unipolar depressed and bipolar subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyoo IK, Sung YH, Dager SR, et al. Regional cerebral cortical thinning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pavuluri MN, OÕConnor MM, Harral E, Sweeney JA. Affective neural circuitry curing facial emotion processing in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system – a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:435–455. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nobler MS, Teneback CC, Nahas Z, et al. Structural and functional neuroimaging of electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12:144–156. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:3<144::AID-DA6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sassi RB, Brambilla P, Hatch JP, et al. Reduced left anterior cingulate volumes in untreated bipolar patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bearden CE, Thompson PM, Dalwani M, et al. Greater cortical gray matter density in lithium-treated patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore GJ, Bebchuk JM, Hasanat K, et al. Lithium increases N-acetyl-aspartate in the human brain: in vivo evidence in support of bcl-2Õs neurotrophic effects? Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown ES, Rush AJ, McEwen BS. Hippocampal remodeling and damage by corticosteroids: implications for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:474–484. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry – the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bookstein FL. ÔVoxel-based morphometryÕ should not be used with imperfectly registered images. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1454–1462. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salmond CH, Ashburner J, Vargha-Khadem F, Connelly A, Gadian DG, Friston KJ. Distributional assumptions in voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1027–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones DK, Symms MR, Cercignani M, Howard RJ. The effect of filter size on VBM analyses of DT-MRI data. Neuroimage. 2005;26:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith S, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]