Abstract

Initial analyses showed that asteroid Ryugu’s composition is close to CI (Ivuna-like) carbonaceous chondrites –the chemically most primitive meteorites, characterized by near-solar abundances for most elements. However, some isotopic signatures (e.g., Ti, Cr) overlap with other carbonaceous chondrite (CC) groups, so the details of the link between Ryugu and the CI chondrites are not fully clear yet. Here we show that Ryugu and CI chondrites have the same zinc and copper isotopic composition. As the various chondrite groups have very distinct Zn and Cu isotopic signatures, our results point at a common genetic heritage between Ryugu and CI chondrites, ruling out any affinity with other CC groups. Since Ryugu’s pristine samples match the solar elemental composition for many elements, their Zn and Cu isotopic compositions likely represent the best estimates of the solar composition. Earth’s mass-independent Zn isotopic composition is intermediate between Ryugu/CC and non-carbonaceous chondrites, suggesting a contribution of Ryugu-like material to Earth’s budgets of Zn and other moderately volatile elements.

Keywords: Ryugu, Hayabusa2, Zn isotopes, Cu isotopes, volatile elements, CI chondrites

Introduction

Ivuna-type (CI) carbonaceous chondrites (CCs) have elemental abundances that are the closest to the composition of the solar photosphere (e.g., [1]) (the exceptions being H, C, N, O, Li and the noble gases). Thus, the CIs are key reference samples for investigating how early Solar System processes shaped the compositions of the planets and their building blocks. The return of the Hayabusa2 spacecraft in December 2020, after two successful touchdown and sampling events on the Cb-type asteroid (162173) Ryugu2,3, offers the unprecedented opportunity to study volatile element fractionation processes using samples unaffected by terrestrial alteration, in particular water incorporation. Initial studies on bulk chemical and isotopic compositions revealed similarities between Ryugu and CIs4–7. However, Ryugu samples exhibit slightly higher Δ17O than the average from other CI samples, Orgueil and Ivuna, which is interpreted in terms of original heterogeneity between small samples, or contamination of the meteorites by terrestrial water incorporated into the structure of the alteration minerals (e.g., phyllosilicates, sulfates, iron oxides and hydroxides), not adsorbed to the surfaces5. Similarly, although Ti and Cr isotope compositions show that asteroid Ryugu formed in the CC reservoir, it was not possible to establish a clear genetic link to just one of the CC groups because the Cr and Ti isotopic compositions of Ryugu overlap not only with Ivuna-like (CI) but also with the Bencubbin-like (CB)5, Renazzo-like (CR)5 and High-iron (CH) groups. However, the low volatile contents of these three groups of meteorites, as well as the metal-rich nature of the CB and CH chondrites, argue against any affinity with Ryugu5,6. Thus, because CI chondrites and Ryugu samples share the same Ti and Cr nucleosynthetic signatures, as well as similar mineralogical and elemental compositions5,6, it has been proposed that they formed contemporaneously from the same outer Solar System reservoir3,5–7.

Material akin to carbonaceous chondrites such as Ryugu and the parent body of the CIs could have delivered significant fractions of the moderately and highly volatile elements present in inner Solar System planets (e.g., 8-13). Because Ryugu samples have been handled carefully to avoid possible contamination, they are ideally suited to estimate the solar composition and assess the contribution of these outer Solar System objects to the inventory of volatile elements in the terrestrial planets. Highly volatile and moderately volatile elements are defined as elements with 50% condensation temperatures (Tc) <665 K and 665–1135 K, respectively, under canonical nebular gas conditions at 10–4 bar (e.g., 14). Zinc and Cu are ideal elements to investigate volatility-related processes, such as volatile element loss, during planetary accretion15, and are classified as moderately volatile elements (MVE) (with Tc of 726 K and 1037 K, respectively)14,16. Carbonaceous chondrite groups display distinct Zn and Cu isotopic mass fractionation effects (e.g., 17-21), defining a trend from CIs to CKs (CK = Karoonda-like), with the CIs being the most volatile-rich and isotopically heaviest (for both Zn and Cu) of the CC groups. We have measured the Zn and Cu isotopic compositions of Ryugu samples to (i) verify the link between Ryugu and CI chondrites for moderately volatile elements, and (ii) assess the contribution of Ryugu-like material to the inventory of moderately volatile elements in Earth.

Results

The Zn and Cu isotope compositions for four Ryugu samples (see Methods section), together with six CC samples [Alais (CI), Allende A and B (CV), Murchison (CM), Orgueil (CI), Tagish Lake (C2-ungrouped) and Tarda (C2-ungrouped)], were determined following the same analytical protocol, and on the same samples as in [5] (Table 1). Most of these CC samples have previously been characterized for their Zn and Cu isotopic composition17–19,21, except Tarda. The isotopic compositions are given as the permil deviations from the JMC-Lyon Zn and NIST SRM976 Cu standards:

| (1) |

where x = 66, 67 and 68.

| (2) |

Table 1. Zinc and copper stable isotope of Ryugu samples and carbonaceous chondrites.

| Sample | Type | na (Zn) | δ66Zn (‰) | 2SDb | δ67Zn (‰) | 2SDb | δ68Zn (‰) | 2SDb | ε66 Zn | 2SEb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryugu | ||||||||||

| C0108c | 8 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.09 | -0.21 | 0.17 | |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.10 | |

| C0107 | 8 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.11 | |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.11 | |

| Average site C | 20 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.06 | |

| A0106-A107 | 8 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.10 | |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.03 | |

| A0106 | 8 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.14 | |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.05 | |

| Average site A | 28 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.05 | |

| Average Ryugu | 48 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.04 | |

|

Carbonaceous

chondrites | ||||||||||

| Orgueil | CI1 | 8 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0.15 |

| Rpt | 8 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.14 | |

| Average Orgueil | 16 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.12 | |

| Alais | CI1 | 8 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.09 | |

| Average Alais | 14 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.11 | |

| Tagish Lake | C2- ung |

8 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.08 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.07 | |

| Average Tagish Lake | 14 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.06 | |

| Tarda | C2-ung | 8 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.12 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.08 | |

| Average Tarda | 14 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.08 | |

| Murchison | CM2 | 8 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.16 | |

| Average | ||||||||||

| Murchison | 14 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.10 | |

| Allende A | CV3 | 5 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.17 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.15 | |

| Average Allende A | 11 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.12 | |

| Allende B | CV3 | 8 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.12 |

| Rpt | 6 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.13 | |

| Average Allende B | 14 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.09 | |

|

Reference

materials | ||||||||||

| IRMM3702 | 7 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| BHVO2 | 12 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.10 | -0.07 | 0.15 | |

n is the number of measurements

2SD is 2 x standard deviation; 2SE is 2 x standard error

Value excluded from the averages for Ryugu

Numbers in italic represent averages for Ryugu and the carbonaceous chondrites for the Zn data

During the course of this study, the two standards gave δ66Zn of 0.00 ± 0.005 ‰ (2SE; n = 163; JMC-Lyon) and δ65Cu of 0.00 ± 0.02 ‰ (2SE; n = 54; NIST SRM976). Zinc isotope measurements are also corrected for mass-dependent fractionation using the exponential law22, with the normalizing ratio of 68Zn/64Zn of 0.385623. Zinc isotopic anomalies are quantified using the epsilon notation relative to the JMC Lyon standard, as follows:

| (3) |

where c is the normalizing ratio 68Zn/64Zn.

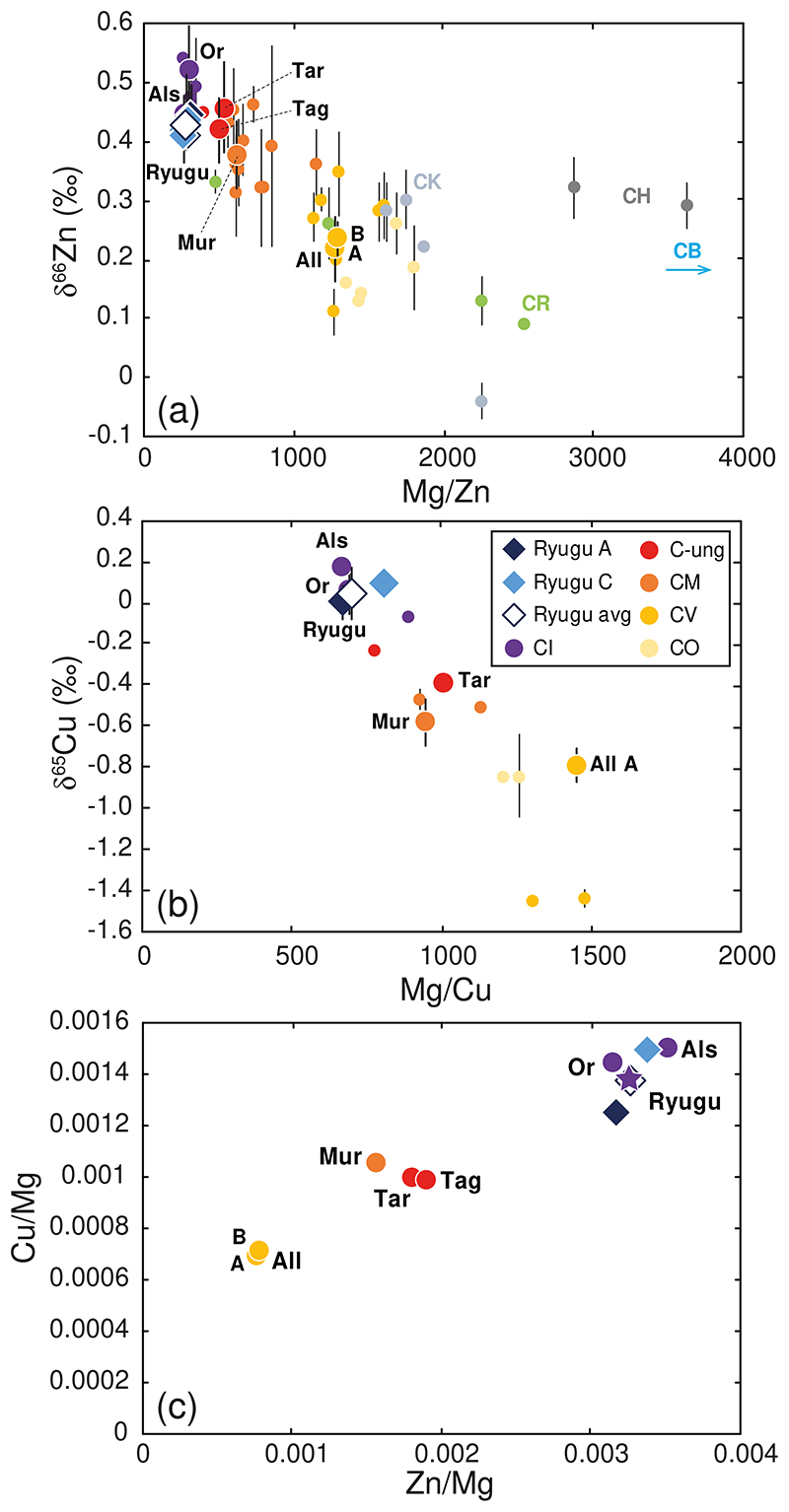

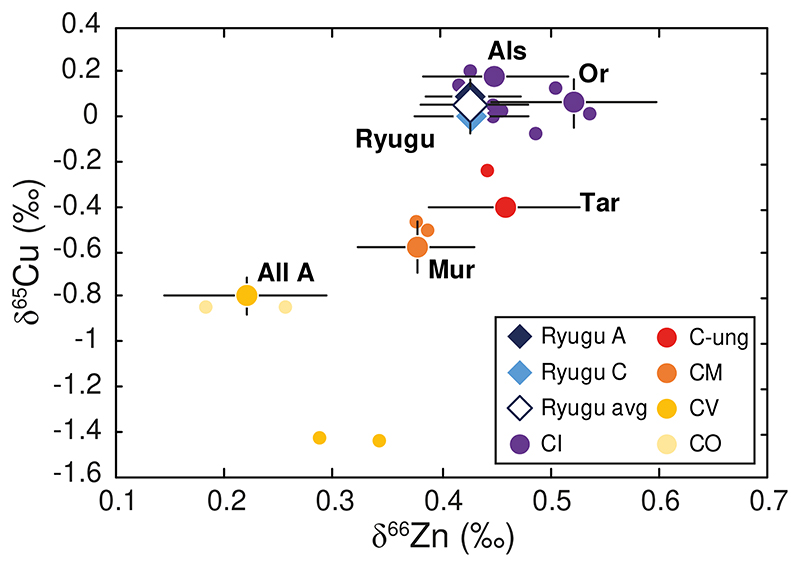

The Ryugu samples span a very limited range of mass-dependent Zn isotopic compositions with δ66Zn from +0.41 ± 0.06 ‰ to +0.45 ± 0.02 ‰ (2SD), with an average value of +0.43 ± 0.05 ‰ (2SD, n = 48) (Fig. 1a and Table 1). The δ65Cu values for Ryugu samples range from 0.00 ± 0.08 ‰ to +0.09 ± 0.05 ‰, (average value of +0.04 ± 0.11 ‰, n = 8, 2SD) (Fig. 1b and Table 1). Zinc and Cu abundances also span limited ranges from 338 ± 4 ppm to 383 ± 6 ppm (average 361 ± 40 ppm, n = 4, 2SD), and from 133 ± 2 ppm to 168 ± 1 ppm (average 147 ± 37 ppm, n = 4, 2SD), respectively (Table 2). These values are higher than the abundances reported for any CI chondrite, consistent with other element abundances for Ryugu samples relative to CIs (Fig. 1, Table 2), although Ryugu samples have lower H2O contents than CIs5. It is worth noting that the samples from both landing sites show identical δ66Zn values (Fig. 1a). In addition, the soluble organic matter (SOM) extractions of samples C0107 and A0106, which was done prior to purification of Zn and Cu, do not seem to have affected the Zn and Cu isotope compositions of the Ryugu samples (see Methods section). All the CCs measured in this study have δ66Zn and δ65Cu values, as well as Zn and Cu abundances, that are consistent with previous studies (e.g., [17–21]), except for the Cu isotopic composition for Allende A, which is more similar to CO chondrites (Figs. 1b and 2). We note, however, that until now only one other measurement of Allende has been reported in the literature19, and so the difference could represent heterogeneity in the different analyzed fractions of Allende in this study and in [19]. Similar sample heterogeneities for Cu isotopic compositions have been reported for several fragments of Orgueil21. The Ryugu samples exhibit Zn and Cu isotopic compositions that are similar to the Alais and Orgueil samples analyzed in this study (Figs. 1 and 2). This is consistent with previous work on the bulk elemental, isotopic, and mineralogical properties of these samples, which reveal a genetic link between the Ryugu samples and CI chondrites, implying formation from the same outer Solar System reservoir4–6.

Figure 1. Zinc and copper elemental and isotopic compositions for Ryugu and carbonaceous chondrites samples.

(a) δ66Zn vs Mg/Zn, (b) δ65Cu vs Mg/Cu and (c) Zn/Mg vs Cu/Mg that we measured for the Ryugu samples (diamonds) and carbonaceous chondrites (large circles with abbreviations: Or=Orgueil, Als=Alais, Tag=Tagish Lake, Tar=Tarda, Mur=Murchison, All=Allende). Small circles are from the literature [17–21] for Zn and Cu isotope compositions (and references therein for major and trace element compositions). The color identifies the type of chondrite as described in the legend. The purple star in panel c represents the CI chondrite composition from [1]. Data are presented as mean values with 2SD error bars, reported in Table 1.

Table 2. Major and trace element compositions of Ryugu samples and carbonaceous chondrites.

| Sample | Type | Zn (ppm) | 2SD | Cu (ppm) | 2SD | Mg (ppm) | 2SD | Mg/Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryugu | ||||||||

| C0108* | 352 | 4 | 156 | 2 | 104222 | 1153 | 296 | |

| C0107 | 383 | 6 | 168 | 1 | 98823 | 2890 | 258 | |

| Average site C | 368 | 45 | 162 | 17 | 101523 | 7635 | 277 | |

| A0106-A107* | 338 | 4 | 133 | 2 | 106866 | 1250 | 316 | |

| A0106 | 369 | 5 | 130 | 2 | 112899 | 3191 | 306 | |

| Average site A | 354 | 45 | 132 | 5 | 109883 | 8533 | 311 | |

| Average Ryugu | 361 | 40 | 147 | 37 | 101509 | 11700 | 294 | |

| Carbonaceous chondrites | ||||||||

| Orgueil | CI1 | 288 | 4 | 131 | 1 | 91158 | 2706 | 3.0 |

| Alais | CI1 | 298 | 3 | 127 | 1 | 84683 | 2489 | 2.9 |

| Tagish Lake | C2-ung | 204 | 5 | 105 | 3 | 107210 | 1275 | 1.2 |

| Tarda | C2-ung | 201 | 3 | 110 | 2 | 111296 | 2388 | 2.1 |

| Murchison | CM2 | 174 | 2 | 117 | 1 | 111130 | 1257 | 1.1 |

| Allende A | CV3 | 110 | 2 | 97 | 2 | 141784 | 2461 | 1.7 |

| Allende B | CV3 | 121 | 1 | 105 | 1 | 157609 | 4882 | 3.1 |

Abundances from [5]

Numbers in italic represent averages for Ryugu, and each of Ryugu sample site

Figure 2. δ66Zn vs δ65Cu for Ryugu samples and carbonaceous chondrites.

Literature data are from [17,19]. Same symbols as in Figure 1 for the samples analyzed in this study. Other chondrite groups from the literature are reported directly on the figure. Data are presented as mean values with 2SD error bars, reported in Table 1. For clarity, only the error bars of our measurements are displayed. Error bars for literature data are not shown.

Discussion

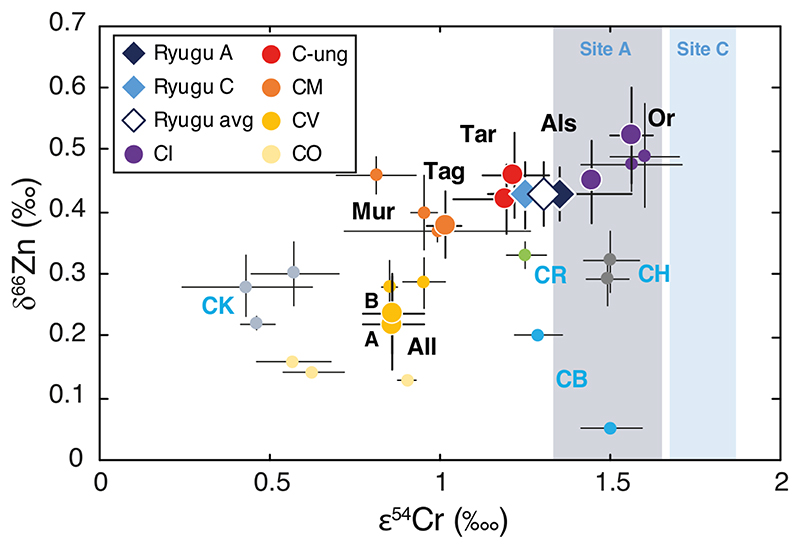

Earlier work has shown that bulk CC chondrites define negative correlations in plots of δ66Zn versus 1/Zn17,18 and δ65Cu versus 1/Cu19. The variable degree of volatile element depletion among the different CC groups reflect mixing of chemically and isotopically distinct reservoirs during their accretion (e.g., 17-19,24,25). The CI chondrites, along with Ryugu, are the least volatile depleted and isotopically heaviest (for both Zn and Cu) of the CC groups, while the most volatile depleted chondrites, the CVs, are the isotopically lightest (this study; [17–21]) (Figs. 1 and 2). The CC trend is interpreted as the result of mixing of volatile-rich material enriched in heavy Zn and Cu isotopes and volatile-poor material enriched in light Zn and Cu isotopes (e.g., [17–19]). Similar correlations are observed for other moderately volatile elements in CCs, such as Te25 and Rb26,27 and their associated isotope compositions, which is interpreted as mixing between matrix (volatile-rich) and chondrules (volatile-poor) (e.g., [17–19,24,26]). Such mixing between distinct CC reservoirs is also observed in the relationships between δ66Zn and nucleosynthetic isotope anomalies, such as ε54Cr (parts per ten thousand mass-independent variations of the 54Cr/52Cr ratio relative to a terrestrial standard) (Fig. 3) (e.g., [18]). Ryugu and the CIs have similar Cu and Zn mass-dependent isotopic compositions and differ markedly from the CBs and CHs (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). We can, therefore, exclude any genetic relationship to the CB or CH groups for the Ryugu samples. A shared nucleosynthetic heritage between Ryugu and CI chondrites has been established based on their identical Ti and Cr nucleosynthetic isotope anomalies5,6. Our Zn and Cu results show that this parentage extends to mass-dependent fractionation of moderately volatile elements, strengthening the link between CI chondrites and Ryugu (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). The near solar Zn and Cu relative abundances of the Ryugu samples, which are free of the potential ambiguities of terrestrial alteration, suggests that the Zn and Cu isotopic compositions measured for Ryugu and the CI chondrites most likely preserved the proto-Sun’s composition1 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 3. δ66Zn (this study) vs ε54Cr [5,30,53–55] for Ryugu samples and carbonaceous chondrites.

Literature data are from [17,18,20] for Zn isotope compositions, and from [56] for Cr isotope compositions. The dark and light blue shaded areas correspond to the ε54Cr ranges for site A and site C, respectively, from [6]. Same symbols as in Figure 1 for the samples analyzed in this study. Other chondrite groups from the literature are reported directly on the figure. Data are presented as mean values with 2SD error bars, reported in Table 1.

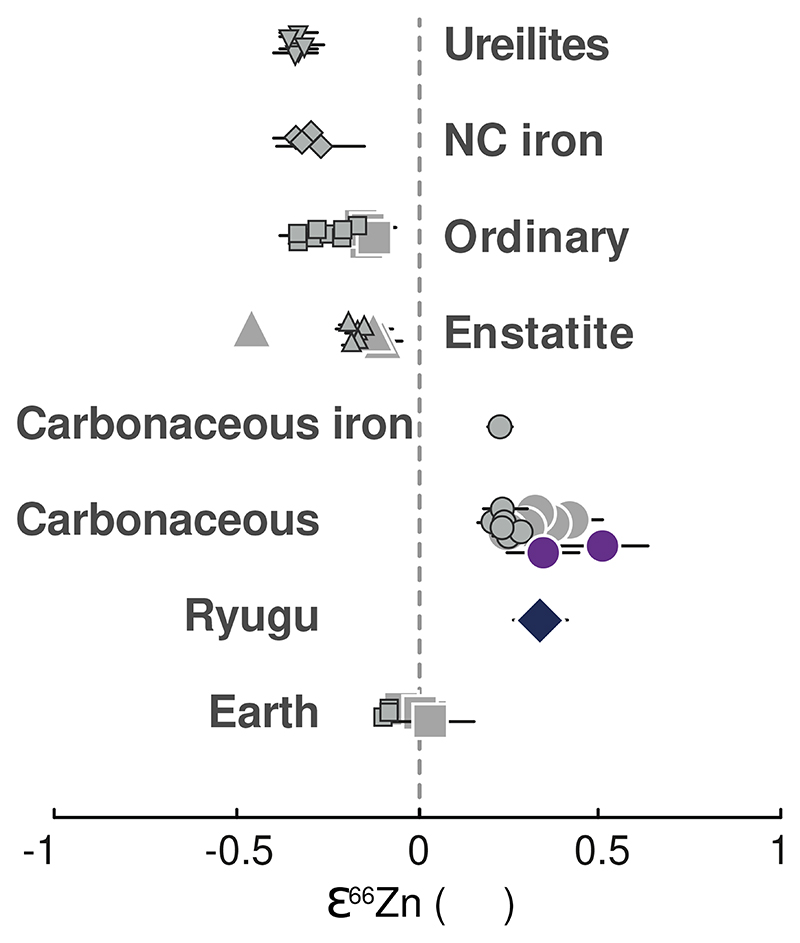

Our study also provides evidence for mass-independent Zn isotope variations (ε66Zn) in Ryugu samples (Fig. 4 and Table 1). These Zn isotopic anomalies are consistent with previous observations28,29. While non-carbonaceous chondrites (NCs) display negative ε66Zn (ordinary chondrites: –0.21 ± 0.04 ‱, 2SE, n = 12, [28,29]; enstatite chondrites: –0.19 ± 0.08 ‱, n = 8, [28,29]), the Ryugu samples and all CCs exhibit identical positive ε66Zn within error (+0.33 ± 0.04 ‱, 2SE, with n = 7 for Ryugu (Table 1) and +0.39 ± 0.07 ‱, n = 7 for CCs, respectively) with the value previously reported for CC of +0.28 ± 0.04 ‱ (2SE, n = 11) [28,29]. It is worth noting that the first replicate of sample C0108 (measured at 100 ppb Zn) has an ε66Zn of –0.21 ± 0.17 ‱, whereas the second C0108 replicate (measured at 250 ppb Zn) has an ε66Zn of +0.35 ± 0.10 ‱ similar to all other Ryugu samples (see Methods section): the first replicate is thus considered an outlier as it was analyzed at the lower concentration of 100 ppb and was excluded from the mean value reported here. The reference geological material BHVO-2 and the Zn standard solution IRMM 3702 measured during the first and second sessions have ε66Zn (–0.07 ± 0.15 ‱, 2SE, n = 12; +0.02 ± 0.11 ‱, 2SE, n = 7, respectively), consistent within error with estimates for bulk Earth (+0.015 ± 0.075 ‱, 2SE, n = 4 [28] and –0.07 ± 0.013 ‱, 2SE, n = 3 [29]). There are no known terrestrial processes which can mass-independently fractionate Zn isotopes. The positive ε66Zn values in the Ryugu samples, therefore, reinforce their genetic link with the CCs (Fig. 4). Thus, the difference between the CCs and NCs, originally identified O and Cr isotope compositions30, and later with Ti, Ni and Mo anomalies31–36, appears to also hold for Zn isotopes.

Figure 4. Variations of ε66Zn among different groups of meteorites.

For comparison purposes, only Ryugu (diamond) and CI (purple circles) samples measured in this study are represented here. Literature data for carbonaceous chondrites ([28] (large symbols), [29] (small symbols)), ordinary chondrites [28,29], enstatite chondrites [28,29], NC and CC iron chondrites [29], ureilites [29] are shown with gray symbols. Bulk Silicate Earth: +0.015 ± 0.075 ‱, 2SE, n = 4 [28] and –0.07 ± 0.013 ‱, 2SE, n = 3 [29]). Data are presented as mean values with 2SE error bars, reported in Table 1.

Because meteorites show a large variability of isotope anomalies37 and planetary accretion is stochastic38–39, it is likely that Earth’s composition does not reflect accretion from a single type of material, both in terms of isotopic and elemental compositions. Although enstatite chondrites are isotopically closest to the Earth40, their chemical signatures are extreme and deviate substantially from the bulk composition of Earth. Possible mixtures of primitive and thermally processed meteorites or their components (e.g., chondrules; [6, 41–43]) have been proposed to explain the chemical and isotope composition of the Earth32,37,44–48. In particular, the mass-independent isotopic composition of Zn of the Earth appears intermediate between CCs and NCs. Thus, our new data show that CC-like materials, potentially akin to Ryugu, have likely contributed to the delivery of Zn and more generally the volatile elements to the Earth. Thus, following the same approach as in [28,29], and using the average ε66Zn = +0.33 ± 0.04 ‱ for Ryugu, +0.35 ± 0.13 ‱ for CI [this study, 28, 29], –0.20 ± 0.04 ‱ (2SE, n = 20) for NC (ordinary, enstatite from [28,29]) and –0.02 ± 0.04 ‱ for the BSE (2SE, n = 7, [28,29]), the mass fraction of Ryugu- or CI-derived Zn in the BSE is estimated 33.5% or 32.2%, respectively. Thus, we find that ~30% of the terrestrial Zn derives from outer Solar System material, while the NC reservoir contributes to ~70% to the terrestrial Zn. Then, to account for the Zn abundances of the accreting materials by Earth, we estimate the mass fractions of NC and Ryugu-like or CI-like bodies accreted by Earth using the Zn abundance of the BSE of 53.5 ± 2.7 ppm [49], and the [Zn]Ryugu of 361 ± 40 ppm [this study] and [Zn]CI of 309 ± 43.8 ppm [this study, 17,18,21]. Thus, up to ~5% of Ryugu-like material (or ~6% of CI-like material) might be needed to account for Earth’s Zn isotopic composition, consistent with estimations from previous studies on Zn isotopic anomalies28,29 and representing a substantial contribution to the terrestrial budget of moderately volatile elements11,28,29.

Methods

Major and trace elements

Zinc and copper isotopic compositions were measured in four samples from the asteroid (162173) Ryugu [C0108, C0107, A0106-A0107 and A0106]. Fragments A0106-A0107 and A0106 are coming from the first touchdown site, and C0108 and C0107 from the second touchdown site4–6. Samples A0106-A0107 and C0108 were pristine samples, whereas A0106 and C0107 were treated for Soluble Organic Matter (SOM) extraction before chemical purification (see Supplementary Table 1). In addition, six CCs [Alais, Allende A, Allende B, Murchison, Orgueil, Tagish Lake and Tarda] were processed following the exact same protocol as the Ryugu samples and were analyzed as controls. For each sample, ~25 mg of powder of all the samples were dissolved at Tokyo Institute of Technology. Elemental abundances were determined using Inductively-Coupled-Plasma Mass-Spectrometry (ICP-MS): major and trace elements for A0106-A0107 and C0108 samples are from [5]. After chemical analysis, the same sample solutions were used to determine Zn and Cu isotopic compositions: Zn fractions were pre-separated, as well as 3% of the bulk rock dissolution for Cu purification which represent about 80-100 ng of Cu.

Zinc and copper purification

All the CC meteorites (except Tarda) have previously been measured for Cu and Zn isotopic compositions and were analyzed as controls. Further chemical purifications of Zn and Cu on the same sample aliquots were conducted at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, using the procedure described by [50] for Zn, and by [51,52] for Cu. For Zn, samples were loaded in 1.5 mol.L–1 HBr on 50 μL of AG1-X8 (200-400 mesh) anion exchange resin in home-made PTFE columns. Matrix elements were washed by further addition of 2 mL of 1.5 mol.L-1 HBr, and Zn was eluted using 2 mL of 0.5 mol.L–1 HNO3. The collected samples were then evaporated to dryness. For Cu, samples were loaded in 1 mL of 7 mol.L–1 HCl on home-made PTFE columns filled with 1.6 mL of AG-MP1 resin. After washing the resin with 8 mL of 7 mol.L–1 HCl, the Cu was collected with 16 mL of 7 mol.L–1 HCl. Both procedures were repeated twice to ensure clean Zn and Cu fraction. Procedural blank is < 0.3 ng of Zn, and 0.6 ng of Cu which is negligible relative to the amount of Zn and Cu in the sample mass analyzed for the Ryugu samples and the CCs.

Zinc and Cu measurements

Zinc and Cu isotope compositions were determined using a Neptune Plus Multi-Collector Inductively-Coupled-Plasma Mass-Spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at IPGP, using sample-standard bracketing for instrumental mass bias correction as in [50] for Zn and [51,52] for Cu. Each replicate was analyzed 6–8 times for Zn and 1–5 times for Cu depending on the amount of Cu available for each sample, and the reported errors are the two standard deviations (2SD) of these repeated measurements. For the Zn measurements, the samples were analyzed in two sessions with different sample solution concentrations: one at 100 ppb of Zn and a second one at 250 ppb of Zn, with an uptake of 100 μL.min-1. For the Cu measurements, the samples were analyzed in one session at the concentration of 30 ppb of Cu, with the same uptake. The high purity of the final Zn fraction is needed to remove isobaric and non-isobaric interferences from the signal. Interference on 64Zn by 64Ni is corrected by measuring the intensity of the 62Ni, assuming natural abundances of Ni isotopes (62Ni = 3.63%; 64Ni = 0.93%). No N2 was used during the measurements, as this results in high background on mass 68 from ArN2. No interference on mass 68.5 from Ba2+ was detected during the sessions. The reference geological material BHVO-2 and the Zn standard solution IRMM 3702 measured during the first and second sessions give values consistent with the literature (e.g., [18,20]). However, during the first session, the Zn fractions were measured at 100 ppb of Zn. All the Ryugu and CC samples had similar positive ε66Zn, except for the first replicate of sample C0108 which had a negative value. In other words, all the samples plot below the mass-dependent equilibrium fractionation line in a δ68Zn against δ66Zn plot, whereas the C0108 replicate falls above it (Supplementary Figure 1a). This motivated our second session of measurements on replicates at higher concentrations (250 ppb of Zn) to ensure that the observed ε66Zn were not analytical artifacts. The second replicate of sample C0108, analyzed at 250 ppb of Zn, shows the same isotopic signature as the rest of the Ryugu sample set and plots below the mass-dependent fractionation line with a positive ε66Zn (Supplementary Figure 1b). In the discussion and associated figures, only the second replicate of sample C0108 is considered and represented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the IPGP analytical platform PARI, Region Ile-de-France SESAME Grants no. 12015908, and DIM ACAV +, the ERC grant agreement No. 101001282 (METAL) (F.M.) the UnivEarthS Labex program (numbers: ANR-10-LABX-0023 and ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02) (F.M.), JSPS Kaken-hi grants (S.T., H.Y., T.Y.) and the CNES. We thank Katarina Lodders, Herbert Palme and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that helped improve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

F.M., M.P. and T.Y. designed the project. H.Y. and T.Y coordinated the isotopic analyses of the samples among members of the Hayabusa2-initial-analysis chemistry team. M.P. and T.Y. processed the samples and separated the Zn and Cu from the matrix. M.P. measured the Zn and Cu isotopic compositions. M.P. and F.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with contributions from T.Y., W. D., Y. H., Y. A., J. A., C. M. O'D. A., S. A., Y. A., K. B., M. B., A. B., R. W. C., M. C., B.-G. C., N. D., A. M. D., T. D. R., W. F., R. F., I. G., M. K. H., Y. H., H. Hi., H. Ho., P. H., G. R. H., K. I., T. I., T. R. I., A. I., M. I., S. I., N. K., N. T. K., K. K., T. K., S. K., A. N. K., M.-C. L., Y. M., K. D. McK., M. M., K. M., I. N., K. N., D. N., A. N. N., L. N., M. O., A. P., C. P, L. P., L. Q., S. S. R., N. S., M. S., L. T., H. T., K. T., Y. T., T. U., S. W, M. W., R. J. W., K. Y., Q.-Z. Y., S. Y., E. D. Y., H. Y., A.-C. Z., T. N., H. N., T. N., R. O., K. S., H. Y., M. A., A. M., A. N., M. N., T. O., T. Y., K. Y., S. N., T. S., S. Tan., F. T., Y. T., S.-I. W., M. Y., S. Tac. and H. Y.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

All data referred to in this article can be found in the tables or source data.

References

- 1.Lodders K. Relative atomic solar system abundances, mass fractions, and atomic masses of the elements and their isotopes, composition of the solar photosphere, and compositions of the major chondritic meteorite groups. Space Sci Rev. 2021;217(3):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morota T, et al. Sample collection from asteroid (162173) Ryugu by Hayabusa2: Implications for surface evolution. Science. 2020;368(6491):654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz6306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tachibana S, et al. Pebbles and sand on asteroid (162173) Ryugu: in situ observation and particles returned to Earth. Science. 2022;375(6584):1011–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yada T, et al. Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nat Astron. 2022;6(2):214–220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama T, et al. The first returned samples from a C-type asteroid show kinship to the chemically most primitive meteorites. Science. 2022 doi: 10.1126/science.abn7850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura E, et al. On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proc Japan Acad, Series B. 2022;98(6):227–282. doi: 10.2183/pjab.98.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito M, et al. A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nat Astron. 2022:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Becker H. Ratios of S, Se and Te in the silicate Earth require a volatile-rich late veneer. Nature. 2013;499(7458):328–331. doi: 10.1038/nature12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savage PS, et al. Copper isotope evidence for large-scale sulphide fractionation during Earth’s differentiation. Geochem Perspect Lett. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schönbächler M, Carlson RW, Horan MF, Mock TD, Hauri EH. Heterogeneous accretion and the moderately volatile element budget of Earth. Science. 2010;328(5980):884–887. doi: 10.1126/science.1186239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braukmüller N, Wombacher F, Funk C, Münker C. Earth’s volatile element depletion pattern inherited from a carbonaceous chondrite-like source. Nat Geo. 2019;12(7):564–568. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0375-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varas-Reus MI, König S, Yierpan A, Lorand JP, Schoenberg R. Selenium isotopes as tracers of a late volatile contribution to Earth from the outer Solar System. Nat Geo. 2019;12(9):779–782. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubik E, et al. Tracing Earth’s volatile delivery with tin. J Geophys Res: Solid Earth. 2021;126(10):e2021JB022026 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodders K. Solar system abundances and condensation temperatures of the elements. ApJ. 2003;1220;591(2) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day JM, Moynier F. Evaporative fractionation of volatile stable isotopes and their bearing on the origin of the Moon. Phil Trans R S A. 2014;372(2024):20130259. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2013.0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer L, Fegley B., Jr Chemistry of atmospheres formed during accretion of the Earth and other terrestrial planets. Icarus. 2010;208(1):438–448. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luck JM, Othman DB, Albarède F. Zn and Cu isotopic variations in chondrites and iron meteorites: early solar nebula reservoirs and parent-body processes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2005;69(22):5351–5363. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pringle EA, Moynier F, Beck P, Paniello R, Hezel DC. The origin of volatile element depletion in early solar system material: Clues from Zn isotopes in chondrules. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2017;468:62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luck JM, Othman DB, Barrat JA, Albarède F. Coupled 63Cu and 16O excesses in chondrites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2003;67(1):143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahan B, Moynier F, Beck P, Pringle EA, Siebert J. A history of violence: Insights into post-accretionary heating in carbonaceous chondrites from volatile element abundances, Zn isotopes and water contents. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2018;220:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrat JA, Zanda B, Moynier F, Bollinger C, Liorzou C, Bayon G. Geochemistry of CI chondrites: Major and trace elements, and Cu and Zn isotopes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2012;83:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosman KJR. A survey of the isotopic and elemental abundance of zinc. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1972;36(7):801–819. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell WA, Papanastassiou DA, Tombrello TA. Ca isotope fractionation on the Earth and other solar system materials. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1978;42(8):1075–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton RN, Mayeda TK. Oxygen isotope studies of carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1999;63(13-14):2089–2104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmann JL, Hopp T, Burkhardt C, Kleine T. Origin of volatile element depletion among carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2020;549:116508 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pringle EA, Moynier F. Rubidium isotopic composition of the Earth, meteorites, and the Moon: Evidence for the origin of volatile loss during planetary accretion. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2017;473:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nie NX, et al. Imprint of chondrule formation on the K and Rb isotopic compositions of carbonaceous meteorites. Sci Adv. 2021;7(49):eabl3929. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage PS, Moynier F, Boyet M. Zinc isotope anomalies in primitive meteorites identify the outer solar system as an important source of Earth’s volatile inventory. Icarus. 2022;386:115172 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steller T, Burkhardt C, Yang C, Kleine T. Nucleosynthetic zinc isotope anomalies reveal a dual origin of terrestrial volatiles. Icarus. 2022;386:115171 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinquier A, Birck JL, Allègre CJ. Widespread 54Cr heterogeneity in the inner solar system. ApJ. 2007;1179;655(2) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trinquier A, Elliott T, Ulfbeck D, Coath C, Krot AN, Bizzarro M. Origin of nucleosynthetic isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science. 2009;324(5925):374–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1168221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren PH. Stable-isotopic anomalies and the accretionary assemblage of the Earth and Mars: A subordinate role for carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2011;311(1-2):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budde G, Burkhardt C, Brennecka GA, Fischer-Gödde M, Kruijer TS, Kleine T. Molybdenum isotopic evidence for the origin of chondrules and a distinct genetic heritage of carbonaceous and non-carbonaceous meteorites. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2016;454:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruijer TS, Burkhardt C, Budde G, Kleine T. Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(26):6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704461114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burkhardt C, Dauphas N, Hans U, Bourdon B, Kleine T. Elemental and isotopic variability in solar system materials by mixing and processing of primordial disk reservoirs. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2019;261:145–170. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nanne JA, Nimmo F, Cuzzi JN, Kleine T. Origin of the non-carbonaceous–carbonaceous meteorite dichotomy. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2019;511:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dauphas N, Chen JH, Zhang J, Papanastassiou DA, Davis AM, Travaglio C. Calcium-48 isotopic anomalies in bulk chondrites and achondrites: Evidence for a uniform isotopic reservoir in the inner protoplanetary disk. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2014;407:96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers JE. Planetary accretion in the inner Solar System. E Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2004;223(3-4):241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh KJ, Morbidelli A, Raymond SN, O’Brien DP, Mandell AM. A low mass for Mars from Jupiter’s early gas-driven migration. Nature. 2011;475(7355):206–209. doi: 10.1038/nature10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Javoy M, et al. The chemical composition of the Earth: Enstatite chondrite models. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2010;293(3-4):259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morbidelli A, Libourel G, Palme H, Jacobson SA, Rubie DC. Subsolar Al/Si and Mg/Si ratios of non-carbonaceous chondrites reveal planetesimal formation during early condensation in the protoplanetary disk. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2020;538:116220 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frossard P, Guo Z, Spencer M, Boyet M, Bouvier A. Evidence from achondrites for a temporal change in Nd nucleosynthetic anomalies within the first 1.5 million years of the inner solar system formation. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2021;566:116968 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander CMD. An exploration of whether Earth can be built from chondritic components, not bulk chondrites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2022;318:428–451. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lodders K. An oxygen isotope mixing model for the accretion and composition of rocky planets. From dust to terrestrial planets. 2000:341–354. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiller M, Bizzarro M, Fernandes VA. Isotopic evolution of the protoplanetary disk and the building blocks of Earth and the Moon. Nature. 2018;555(7697):507–510. doi: 10.1038/nature25990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiller M, Bizzarro M, Siebert J. Iron isotope evidence for very rapid accretion and differentiation of the proto-Earth. Sci Adv. 2020;6(7):eaay7604. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mezger K, Maltese A, Vollstaedt H. Accretion and differentiation of early planetary bodies as recorded in the composition of the silicate Earth. Icarus. 2021;365:114497 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johansen A, et al. A pebble accretion model for the formation of the terrestrial planets in the Solar System. Sci Adv. 2021;7(8):eabc0444. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sossi PA, Nebel O, O’Neill HSC, Moynier F. Zinc isotope composition of the Earth and its behaviour during planetary accretion. Chem Geol. 2018;477:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Kooten E, Moynier F. Zinc isotope analyses of singularly small samples < 5 ng Zn): investigating chondrule-matrix complementarity in Leoville. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2019;261:248–268. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moynier F, Creech J, Dallas J, Le Borgne M. Serum and brain natural copper stable isotopes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47790-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moynier F, et al. Copper and zinc isotopic excursions in the human brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia: DADM. 2020;12(1):e12112. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petitat M, Birck JL, Luu TH, Gounelle M. The chromium isotopic composition of the ungrouped carbonaceous chondrite Tagish Lake. ApJ. 2011;736(1):23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schoenberg R, et al. The stable Cr isotopic compositions of chondrites and silicate planetary reservoirs. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2016;183:14–30. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dey S, Yin QZ, Zolensky M. Exploring the Planetary Genealogy of Tarda—A Unique New Carbonaceous Chondrite; 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference; 2021. Mar, p. 2517. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu K, et al. Chromium isotopic insights into the origin of chondrite parent bodies and the early terrestrial volatile depletion. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2021;301:158–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2021.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data referred to in this article can be found in the tables or source data.