Abstract

Insights from comparative genomics, whereby the genomes of different species are compared, have the potential to address broad and fundamental questions at the intersection of genetics and evolution. However, species, genomes and genes cannot be considered as independent data points within statistical tests. Closely related species tend to be similar because they share genes by common descent, which must be accounted for in analyses. This problem of non-independence can be exacerbated when examining genomes or genes. The application of phylogeny-based methods to comparative genomics can address this problem. These methods must be considered an essential part of the comparative genomics toolkit, to prevent the accumulation of studies that produce incorrect conclusions. Here, we review how controlling for phylogeny can change the conclusions of comparative genomics studies. We address common questions about how to apply these methods and illustrate how they can be used to test causal hypotheses. The combination of rapidly expanding genomic datasets and phylogenetic comparative methods is set to revolutionize our understanding of biology.

[H1] Introduction

Since the beginning of the century, the number of sequenced genomes has increased to many hundreds of thousands, providing a full genetic record for thousands of species across the tree of life1–5. Comparing the genomes of different species can provide insight into which genes control particular phenotypic traits and how those traits evolved. For example, comparative genomics has identified bacterial genes that harm crops6,7, tracked antibiotic resistance through hospitals8,9, and unravelled how echolocation evolved independently in dolphins and bats10–12.

Comparative genomics datasets often contain biases that, unless fully accounted for, can lead to incorrect conclusions. Statistical tests assume that data points are ‘independent’ from one another. This means that each data point represents an individual replicate drawn from an underlying distribution, and the value of any one data point does not depend on or influence the value of any other data point. Even a slight lack of independence can lead to bias in statistical analyses and incorrect conclusions13–15.

A problem for biologists wanting to conduct any form of across-species comparative analyses is that species do not represent independent data points16–20 (Fig. 1a). Closely related species tend to be similar because they share traits by common descent rather than through independent evolution (Fig. 1b). To give an extreme example, passerine birds all have wings because they inherited the genes to produce them from a common ancestor, not because each species independently evolved to fly. In genomic datasets, data points can correspond to genomes or even individual genes, meaning the problem of species not being independent can be exacerbated by additional levels of non-independence, including genes within genomes, such as those carried on the same replicon, and genomes of the same or closely related species16,19,21–26. The problem of non-independence is complicated even further by how unrepresentative most genomic datasets are of natural communities, owing to biases in which species have been sequenced more frequently (Fig. 2)27–29.

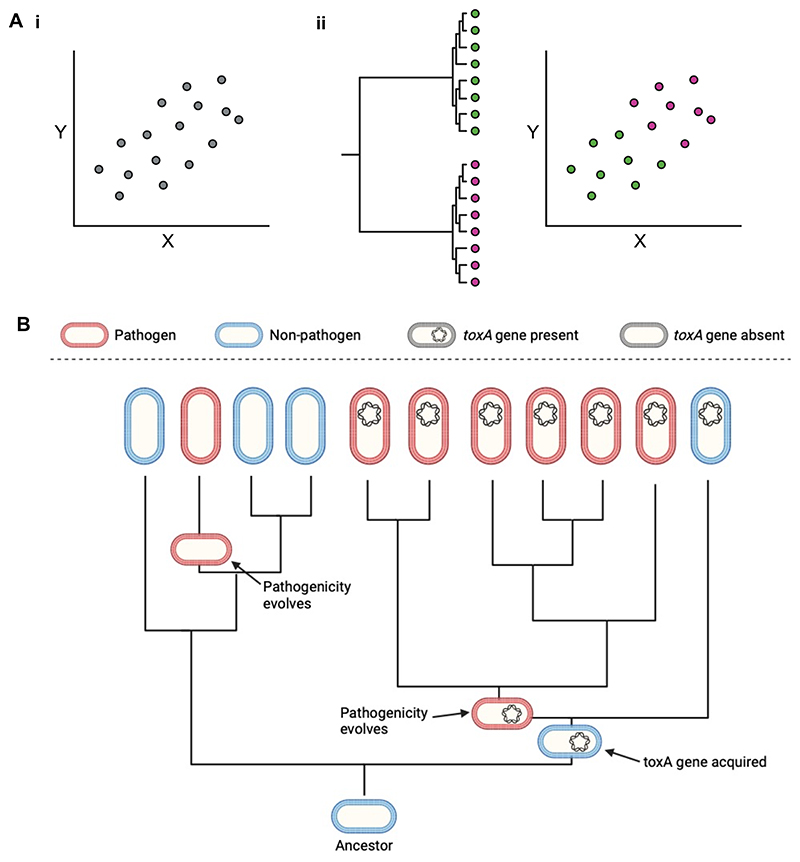

Figure 1. Species are not independent data points.

A.i. There seems to be a strong positive correlation between X and Y, where each dot is a species (n=16 species). ii. In an extreme scenario those species are from two separate, monophyletic lineages represented by green and pink dots. When mapped onto the original scatterplot, the two lineages form largely separate clusters. Within each of those clusters, there is no relationship between X and Y. The original correlation was just an artefact of the mean values of X and Y in the pink lineage being larger than the green lineage. Inspired by Figures 5-7 in Felsenstein, 198518. B. A simple hypothetical genomic example. Each tip is a bacterial species; red and blue cells correspond to pathogenic and non-pathogenic species, respectively, and species which carry toxA are indicated by cells with the gene present. Using the species at the tips of the tree as independent data points, we might spuriously conclude that toxA facilitates the evolution of pathogenicity: 85% of pathogenic species carry toxA (6/7 species), compared to only 25% of non-pathogenic species (1/4 species) (Chi-squared=4.05, p<0.05). However, this significant correlation is an artefact of shared evolutionary history. Pathogenicity only evolved twice in the phylogeny: once in a lineage with toxA and once in a lineage without toxA. Rather than independent data points, the cluster of pathogenic, toxA carrying species are analogous to technical pseudoreplicates in an empirical study.

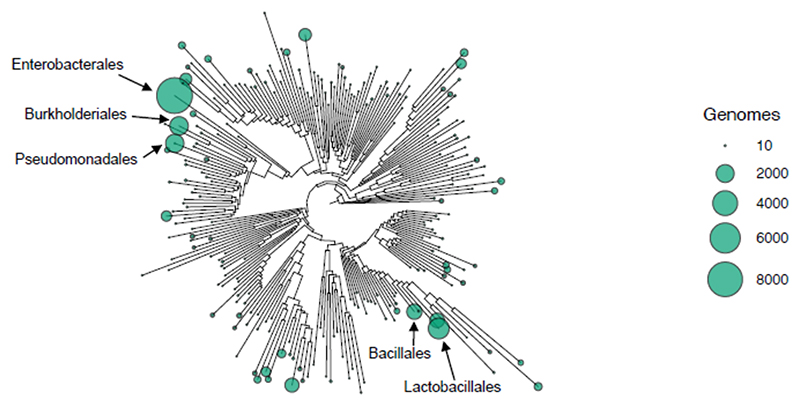

Figure 2. Phylogenetic bias of genome sequencing.

Order level visualisation of the GTDB bacterial phylogeny (v.214)134; the size of dots corresponds to the number of complete bacterial genomes represented in both the RefSeq and the GTDB database from each taxonomic order. Labels correspond to the five orders with the most genome sequences.

The fact that species cannot be considered independent data points was first recognized in the 1970s by evolutionary biologists studying the evolution of life history traits such as sexual dimorphism and home range in primates16,18,30–32. This led to the development of numerous methods that take phylogeny into account and control for the non-independence of species16,18,19,33. These phylogeny-based comparative methods have revolutionized behavioural and evolutionary ecology research, including research into sexual selection, resource competition and social evolution34. However, the application of phylogeny-based comparative methods to genomic data has not been consistent, and has been limited in some areas such as microbial genomics. The potential problem of non-independence remains to be fully recognized across the entire field of comparative genomics. In contrast, many of those developing and using phylogeny-based methods focus on phenotypic, rather than genomic, traits. Consequently, some sections of these fields have developed separately, with little discourse, although the problems and solutions are very similar. It is crucial that these existing phylogenetic methods are now consistently applied to genomic data to prevent the accumulation of studies with spurious conclusions.

Here, we review how phylogeny-based comparative methods can be used to analyse genomic data to resolve two key problems: species are not independent, and using genes and genomes as data points can multiply the problem of non-independence. We provide illustrative case studies in which controlling for non-independence led to changes in the biological conclusions drawn from genomic data (Box 1). We address common questions that arise regarding when and how to control for phylogeny, and show how phylogeny-based methods can be used to test causal hypotheses. We focus on comparative genomic analyses across species, although comparative genomics can also be conducted within species; the questions and methods used are generally analogous, and problems encountered are similar to those we discuss here35–40. Of note, phylogenetic methods can be used to also address other questions, such as how features of the genome influence diversification41–43.

[H1] Control for phylogenetic relationships

The problem of species’ non-independence can be solved by taking the evolutionary history of species into account. A phylogeny is a tree that shows the evolutionary relationships between species, and many methods allow us to incorporate phylogenies into statistical models and tests. While each approach is different, they all ultimately account and control for phylogenetic non-independence. Here, we summarize the most used methods (Table 1).

Table 1. Current methods to identify and/or control for phylogenetic non-independence.

| Method | What it does | When to use it | How to use it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic | Adds a trait’s correlation with evolutionary history | Estimating correlation between two variables while controlling for phylogeny. | R packages ‘phylolm’, ‘ape’, ‘caper’. |

| regression19,44,45,129 (phylogenetic least squares, PGLS) |

as an additional term. | Can be generalised for response variables such as count data. Use phylogenetic logistic regression for binominal or binary response variables.45 Estimating phylogenetic signal. Continuous or discrete data. |

|

| Phylogenetic mixed model49,52,86,130,131 | Includes phylogenetic similarity as a random effect within a mixed model. | For multiple explanatory traits of interest. Bayesian and frequentist options. Continuous or discrete data. |

R packages ‘MCMCglmm’, ‘brms’, ‘phyr’. Computer package ‘BayesTraits’. |

| Independent contrasts18,37 | Tests correlation between traits across pairs of closely related species. Equivalent to phylogenetic regression. |

When phylogeny uncertain or dataset includes many closely related pairs of species with different trait values. Largely equivalent to phylogenetic regression.19 Continuous or discrete data. |

R packages ‘ape’, ‘caper’, ‘castor’. |

| Ancestral state reconstruction43,51,85–87,132 | Uses trait values of extant species to reconstruct likely trait values of ancestors. | To examine how many times a trait has evolved, and compare the ancestral states of multiple traits to examine evidence for correlated evolution. Continuous or discrete data. |

R packages ‘corHMM’, ‘MCMCglmm’ (as described in91,133). Computer package ‘BayesTraits’. |

| Correlated evolution models33,39,51,85 | Tests if two traits are correlated with one another more than expected due to phylogenetic history. | When both traits are binary, or when continuous traits can be expressed as binary (i.e. ‘high’ and ‘low’). Often includes ‘transition rate’ analysis, to examine how evolution occurs between states. Discrete data. |

R packages ‘ape’, ‘phytools’. Computer package ‘BayesTraits’, ‘RevBayes’. |

| Phylogenetic path analysis84,88,89 | Compares support for different causal hypotheses, while taking phylogeny into account. | Use if three or more variables/traits of interest, and goal is to test between different causal hypotheses. Continuous or discrete data. |

R package ‘phylopath’. |

[H2] Phylogenetic regressions and mixed models

One class of methods to control for phylogeny uses phylogenetic regressions19,44,45. These are like standard regression approaches but with an additional term to account for a trait’s correlation with species’ evolutionary history (‘phylogenetic signal’). Similar to other linear models, phylogenetic regressions can be generalized to allow for non-Gaussian response variables. These phylogenetic regressions can also be expanded to phylogenetic mixed models, to analyse the influence of multiple variables. As with standard mixed models, phylogenetic mixed models allow us to include all explanatory variables as either: a fixed effect, meaning one would like to test the effect on the response variable; or a random effect, meaning one would like to control for any effect on the response but not explicitly test it in the analysis. A phylogenetic mixed model includes the phylogeny as a random effect, often as a matrix corresponding to the structure of the phylogeny. This approach can examine whether any of the potential explanatory variables has a significant effect on the response variable, while controlling for the phylogenetic signal. In terms of controlling for phylogeny, using a phylogenetic regression or including the phylogeny as a random effect within a mixed model are largely analogous. Which method is most appropriate will depend on factors such as the type and distribution of the data and the number of variables of interest, and it is often useful to analyse the data multiple ways to confirm that results are robust.

There are many methods to run phylogenetic regressions and mixed models. Classic phylogenetic regressions can be run in R packages such as ‘phylolm’ and ‘ape’. More recently, Bayesian approaches have become popular, using R packages such as ‘MCMCglmm’ and ‘brms’, and the computer package ‘BayesTraits’ (Table 1)42,46–52. These different approaches all share the same underlying rationale: to account for phylogeny within statistical analyses. Which approach to use depends on the research question and the nature of the data42. In addition, as with any regression, the impact of any deviation from homogeneous variance should be considered53.

[H2] Rapidly evolving traits

The problem of species non-independence still arises when examining evolutionary labile traits that evolve very fast or are the product of very recent events. For example, mutation–selection balance, polymorphism at highly variable alleles, or the recent acquisition of genes by horizontal gene transfer. A total lack of phylogenetic signal is at one end of a spectrum and not a reason not to avoid phylogenetic comparative methods44,54–56. Even if a response variable shows low (or no) phylogenetic signal, an explanatory variable, known or unknown, could still be correlated with phylogeny. Phylogenetic comparative analyses provide a method to control for spurious results that could arise due to even unknown variables. It is rare that one can be sure that all biologically important variables are being considered, or that the unknown unknown variables are completely independent with respect to phylogeny. Bergeron et al. analysed how the fast-evolving trait of germline mutation rate varied across vertebrate species, while controlling for phylogenetic non-independence57. The key point here is that controlling for phylogeny is not simply controlling for phylogenetic signal or inertia (constraint) — it is about the philosophy of hypothesis testing and whether data points are independent.

Closely related species share many features of their ecology and life history. Consequently, there is an almost unlimited number of unknown ‘third’ variables which might influence the trait of interest20. For example, closely related species could show similar mutation–selection balance or genetic variation at certain loci because of selection imposed by a similar feature of their ecology or some other trait58–60. It is unrealistic to assume that every possible confounding factor can be identified and controlled for, but phylogenetic methods offer a way to control for unknowns. Similar problems, and a need for phylogenetic methods, arise when using data from other omic methods, such as transcriptomics, metagenomics or metabolomics61–64.

[H1] Control for genomes and genes in a phylogenetic context

Analysing genes or genomes as if they were independent data points can be equivalent to having more technical (pseudo) replicates in an experiment, but then treating each as if they were a truly independent sample (biological replicate)22. For example, if examining whether a gene’s GC content is correlated with its length, we could analyse all 41 million genes across all 1,800 eukaryote genomes in the RefSeq database. However, multiple genomes from the same species are not independent – in the extreme, they may even have arisen via duplication. In addition, the number of genes per genome varies from 465 to 155,000 genes, which means that considering each gene as an independent data point would bias the data towards species with larger genomes.

This problem is made worse because genomic databases are biased towards taxonomic groups that have been sequenced more frequently27–29 (Fig. 2). For example, of 28,504 complete bacterial genomes in both the RefSeq and Genome Taxonomy Databases, 26% (7,376) are from 0.1% of species (Supplementary Table 1). By contrast, 73% of bacterial species have only one representative genome in the databases. Across all genomes in the newly curated AllTheBacteria database, the 10 most sequenced species make up 77% of the 1.9 million genomes5. More broadly, there is also a bias towards bacterial genomes relative to eukaryotes3. If all genomes were used as independent data points, this would increase the bias towards species that have been sequenced the most.

As with non-independence due to the phylogenetic history of species, non-independence of genes and genomes should be controlled for in statistical analyses to avoid incorrect conclusions. One possibility is to retain all the data in a mixed model — individual genomes could be included as data points, with species’ phylogeny and also species’ sample size as random effects22,23,49,65–67. Where possible and required for the question being asked, non-independence within the genome due to duplication should also be controlled for, such as by grouping genes into homologous groups.

Another simple solution is to calculate average values for all genes in a genome and/or all genomes in a species before controlling for species phylogeny22,26,65,68. This would control for genome and/or species-level phylogenetic non-independence without the additional confounding effect of sample size differences. Data could be weighted according to the number of genomes per species, because the average for species with more samples would have a lower error variance69. The ‘average value’ for a species could alternatively be some other statistic calculated from the genomes of that species, such as a correlation coefficient or an effect size65,67. For our GC content and gene length example given above, one could calculate a correlation coefficient between GC content and gene length for each genome or species.

In terms of sampling bias, phylogenetic methods will control for when taxa are overrepresented, so that better sampled taxa will not have a disproportionately large influence on analyses. It is, however, only possible to control for biases in representation of taxa currently present in a dataset. If taxa are missing, then their underrepresentation cannot of course be accounted for. Current and future efforts to sequence more taxa will be incredibly useful to tackle broad across-species questions3,4,70–74.

[H1] Testing causal hypotheses

Comparative genomic analyses usually test for correlations between traits. For example, recent genomic studies have examined correlations between factors such as pathogenicity and genome size, GC content and growth temperature, or the presence of certain genes and ecology37,67,75–83. However, these results are open to multiple causal explanations. For example, a correlation between pathogenicity and smaller genome size could arise because pathogenicity favours the evolution of a reduced genome size or because a smaller genome size facilitates the evolution of pathogenicity.

More recently developed methods allow analyses to go further and test competing causal hypotheses42,84. One approach is to use the characteristics present in extant species, together with a phylogeny, to reconstruct the characteristics of their ancestors (‘ancestral states’). These ancestral states can be used to examine whether the evolution of certain characteristics is correlated. For example, do two characteristics tend to vary together along the branches of the phylogeny? If yes, this could be because they are both independently correlated with phylogenetic history or another third trait, or at least one characteristic directly influences the evolution of the other. To distinguish which scenario is more likely, we could test whether an ancestral change in one trait consistently leads to the same change in the other trait, which would suggest the co-evolution is due to a causal link42,43,51,85–87 (Fig. 3).

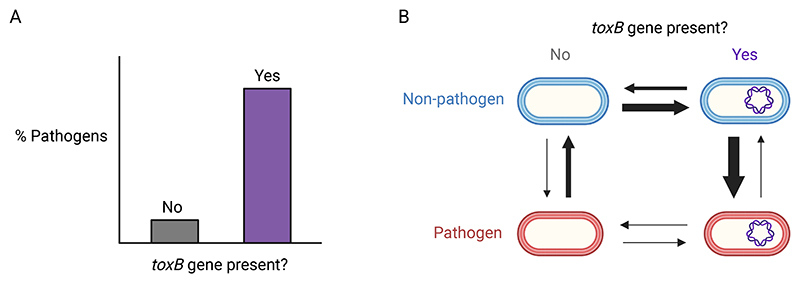

Figure 3. Testing causal hypotheses.

A. Imagine that bacterial species which carried the gene toxB were more likely to be pathogens. Can we test if causality is in that direction, with toxB favouring the transition to pathogenicity? B. Yes, we can use transition rate methods33,42,51,85. For the two binary traits pathogenicity and toxB presence, there are four possible states, each represented by a cell. The quantity of evolutionary transitions between these states across the phylogeny is indicated by arrows: larger arrows correspond to evolutionary changes which occur more frequently. We can see that almost all transitions to pathogenicity (blue → red) occur when the species already has the toxB gene. Most often, non-pathogens first acquire the toxB gene, and then evolve pathogenicity, suggesting that toxB does help pathogenicity to evolve.

What if there are more than two traits we are interested in? For example, there could be multiple traits that are correlated with one another. In this case, causal inference methods such as phylogenetic path analysis could be used to test causal hypotheses84,88,89. These methods are based on the fact that if correlation is not due to random chance, correlation must instead be due to some underlying causal relationship(s), and we can use information from correlations to examine which relationship(s) is most likely84,88. A general point here is that correlational results from observational data do not prove causation, but correlations can be used within comparative analyses to test causal hypotheses and examine evidence for causality42,90.

Recent studies have provided examples of the insights that can be made with this approach. For example, species of snapping shrimp that are more social tend to have larger genomes with more transposable elements; a phylogenetic path analysis and ancestral state reconstruction supported the hypothesis that the acquisition of more transposable elements leads to both larger genome size and higher rates of sociality68. As another example, bacterial species with more fluid pangenomes have both more variable lifestyles and larger effective population sizes; a phylogenetic path analysis supported the hypothesis that this was due to lifestyle traits together influencing gene gain and loss, and that effective population size did not have a casual influence on pangenome fluidity24. There are numerous other possible applications for this approach.

[H1] Common questions

Several questions commonly arise about when and how to control for phylogeny in across-species comparative studies.

[H2] Do we always need to control for phylogeny?

“Phylogenies are fundamental to comparative biology; there is no doing it without taking them into account.”18 There is no simple and robust alternative to controlling for phylogeny, and consequently, the best effort possible must be made to take phylogeny into account, to be able to detect real effects and avoid false positives. There are almost always approaches which can reduce, even if not completely remove, the risk of incorrect conclusions.

If there is uncertainty in the phylogeny, one solution is to include multiple trees with alternative structures in the analysis, to estimate the effect of phylogenetic uncertainty on any result (that is, to determine for how many alternative structures the results are robust)91. Another solution is to use datasets with a narrower range of genomes, so that phylogenetic relationships can be reconstructed. For example, Frigols et al. focused on a particular group of viruses, phages that infect staphylococcal bacteria, to reconstruct and control for phylogenetic relationships92. Different methods can also be used depending upon the information available38,66,93,94. Murray et al. examined how genome size correlated with pathogenicity in bacteria by comparing ‘phylogenetically independent’ pairs of pathogenic and non-pathogenic species within the same genera37. Similarly different methods can be used to investigate or account for factors such as different modes of evolution or changing evolutionary rates95–97.

New methods are required to examine phylogenetic relationships in cases where generating a meaningful phylogeny is hard or impossible, such as fast-evolving mobile genetic elements and viruses. For such cases, current approaches include using the phylogeny of the host genome, controlling for similarity using conserved regions such as plasmid relaxases, or similarity scores from network analyses22,23,65,77,98–100. There are pros and cons of these approaches. The phylogeny of the host genome can be useful for broad, across-species phyla datasets, where host range often acts as a meaningful barrier, but not between more closely related species. The extent to which similarity scores correspond to evolutionary history remains an open question. Results based on such methods will be tentative, and it can be useful to try different methods to test the robustness of conclusions. The usefulness of controlling for phylogenetic non-independence will also be dependent on the accuracy of the phylogeny, emphasising the advantage of new data and methods which allow more reliable phylogenies101.

The problem of non-independence is not solved by alternative methods such as grouping data by a higher taxonomic rank (for example, genera or family), or by sampling the same number of genomes from taxonomic groups to minimize oversampling (‘downsampling’)102,103. Grouping by an arbitrary taxonomic rank does not remove the problem of non-independence between the ranks19,104. Uniform sampling of genomes reduces bias in the dataset towards more sequenced species, but has no effect on the phylogenetic non-independence between those species. A related issue arises with methods that use a phylogeny to extract data from genomes such as orthologous or co-occurring genes93,105–107. Although a phylogeny has been used during the collection of such data, it is still important to control for any phylogenetic non-independence when analysing those data across genes, genomes and species93.

What about methods used in the fields of phylogenomics and evolutionary genomics? Researchers in these fields are developing tools to extract data from genomes such as orthologous or co-occuring genes, and to do this explicitly use a phylogeny93,95,105,106,108–110. However, just because a phylogeny has been used during the collection of any data, it is still important to control for any phylogenetic non-independence when analysing that data across genes, genomes and species93,111,112.

A possible exception arises for certain types of purely descriptive questions. For example, does the GC content of sequenced species vary between two orders of insects, such as Hymenoptera and Coleoptera113? While there is no evolutionary power to explain this variation (n=2 groups), one can still ask whether they differ. However, even with this kind of question, it could still be useful to determine an evolutionary average, which accounted for sampling across the phylogeny113. Furthermore, controlling for phylogeny would be required for other questions, such as does GC content correlate with chromosome size, or how can we explain variation in GC content113? Wording is key, to make clear what kind of question is being asked.

[H2] Does controlling for phylogeny reduce statistical power?

Statistical power refers to how well a dataset can detect real effects (that is, avoiding Type I errors or ‘false negatives’). Controlling for confounding variables such as phylogeny does not reduce statistical power, because such variables should be accounted for before making any estimates of power18,114,115. Instead, controlling for phylogeny can reduce the chance of detecting a significant result that is not real (Type II error or ‘false positive’)18,42. For example, when a result that is driven by a phylogenetically correlated confounding factor, or a bias in genome sampling (Fig. 1). The general point here is that prioritizing the ability to produce significant results ahead of controlling for potential confounding variables can lead to incorrect conclusions not actually supported by the data. Statistical power is based upon the ability to detect real effects, not just significant effects. Phylogenetic analyses could also make it more likely to detect a real effect, by controlling for a confounding variable.

[H2] Is collecting more data a solution?

More data is always preferable, but not all data are equal. Collecting many more data points from the same phylogenetic cluster could increase any bias due to phylogenetic non-independence (Fig. 1)16,18,20. If phylogeny is not controlled for, then increasing the number of data points in this way could make obtaining an spurious result more likely.

There can be trade-offs between data quantity and quality. It is important to sample across taxonomic breadth, especially where there have been changes (transitions) in key variables. Other possible factors to consider are the number of genomes per species, the quality of the genomes (for example, compare the large-scale database GenBank with the smaller, but higher-quality database RefSeq), the methods or tools used to assign gene function, or the assignment of species to a certain environment or lifestyle65,82,105,106,116,117. Applying higher thresholds towards any of these factors can lead to smaller but higher-quality datasets. The relative costs and benefits of different methods can depend upon the question being asked. For example, population genetic analyses have found it easier to detect signatures of selection in smaller but higher-quality data sets117,118.

[H2] Does statistical significance reflect biological importance?

Statistical significance does not necessarily reflect biological importance. Usually, the level of significance (the size of a P-value) will depend on the size of the effect and the number of data points, tested against a null hypothesis of exactly zero difference, or exactly zero correlation119–121. Hence, in the extreme, very large datasets will almost always produce significant P-values, even if the estimated effect size is relatively small122 (Fig. 4). Two groups are unlikely to ever have identical means, and a correlation of a finite number of data points is unlikely to ever be exactly zero. This can be a real problem for comparative genomic analyses, where datasets can be massive, made up of thousands of individual genes, replicons or genomes.

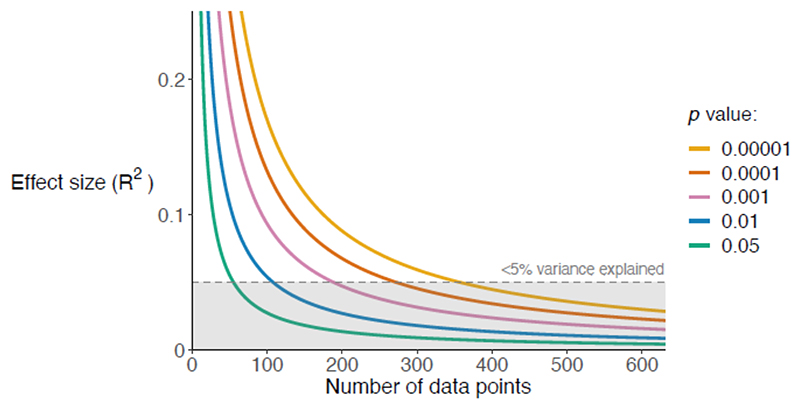

Figure 4. Statistical significance and biological importance.

The effect size (R2; proportion of variance explained) required to produce a statistically significant result decreases with the number of data points (sample size). For an unpaired t-test, the x-axis is the number of data points in each of the two groups compared within the t-test (N1=N2=N) and the y-axis is the minimum R2 value which could be significant to one of five p-values for a given N. The lines show the numerical relationship between the axes for each of five p-values, which are all considered statistically significant. The area corresponding to <5% of the variance explained is shaded in grey (R2<0.05). Larger datasets can detect smaller effects, but very large datasets will assign almost all effects as significant, even when they explain far less than 5% of the variance.

Consequently, it is crucial to consider the size of an effect, not just its significance122. Is an effect large enough to be biologically meaningful? One approach would be to examine the percentage of variance explained (R2). For example, do the explanatory variables explain at least 5–10% of variance in the response variable?123 The maximum possible variance that could be explained will depend on the extent of measurement error69. To consider a specific case, in Fig. 4, even for the very small P-value of P=1x10-4, datasets of ~350 data points or more will produce significant results when the R2 value of the effect is less than 5%. At n=10,000, a relationship explaining only 0.027% of the variance would be significant to P<0.05. A result can be statistically significant even when it is unlikely to be biologically important.

It can also be helpful to compare the size of an effect to those typically found in a research field. What is the average % explained? What % is explained by a successful study? Considering the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology, the average % of variance explained in an analysis is 3.6%123. Particularly successful areas, such as the evolution of sex ratios and cooperation, have produced comparative studies that can explain 20–40% of the variation in data across species124,125.

[H2] What can we conclude if there is little or no variation in an explanatory variable?

The usual purpose of a comparative study is to explain variation that has been observed in nature. If there is a characteristic or trait that exhibits variation, but the cause of this variation has yet to be explained, one can use comparative analyses to examine what might explain that variation.

Imagine a scenario where a response variable (Y) showed considerable variation across species, but one of the possible explanatory variables (X) did not vary appreciably across species (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Does this mean that the possible role of the explanatory variable X cannot be tested? On the one hand, if we were interested in understanding the consequences of variation in X, then this dataset would not allow us to test this, because X does not vary. On the other hand, if we were interested in what explains variation in Y, it is clear that variation in Y is not explained by variation in X. This doesn’t mean that X has no influence on Y, but rather that variation in X is not important for explaining the variation in Y that has been observed in nature. A lack of variation in a potential explanatory variable (X), while the response variable (Y) does vary, is an important result, not a failing of the dataset24.

In this case, the next step would be to look for other explanatory variables that could explain the variation in Y (Z etc.) (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Returning to the issue of data quality versus quantity, this also emphasises the benefit of trying to capture as much of the observed variation in nature as possible (for both response and explanatory variables).

[H1] Conclusions

Comparative analyses in the genomic age have the potential to answer broad and fundamental questions at the intersection of genetics and evolution. The explosion of genomic data during the first quarter of the 21st century calls for a rapid adoption of appropriate approaches and methods, or else risks an accumulation of spurious results and conclusions.

Methods are still being developed and debated for certain types of question, and there are cases where the lack of a good phylogeny will pose a problem112. In cases where complications arise it can be extremely useful to analyse the data with multiple methods to test the robustness of conclusions24,126. Nonetheless, there are many situations where relatively standard and accepted methods can be used. And testing different ways of controlling for phylogeny is better than not controlling for phylogeny (Box 1). It is also worth looking back historically — while there was initially resistance and misunderstanding about the application of phylogenetic methods to study adaptation at the organismal level, there is now no doubt that they have revolutionized the field20,34,42,127,128.

Box 1. Case studies.

Controlling for phylogenetic non-independence has led to different conclusions from the same or very similar datasets. In this box, we showcase three recent studies. Another example is provided by two studies which used the same multi-species dataset but found opposite results when testing whether gene connectivity differed for genes on plasmids compared to on chromosomes65,135.

[bH1] Plasmids and cooperation

The growth of many bacteria depends on the secretion of molecules that provide a benefit to the local group of cells, a form of cooperation (public goods)136. It had been hypothesised that genes for cooperation would be favoured if they could be horizontally transferred on mobile elements such as plasmids to non-cooperating cells137,138. Consistent with this hypothesis, two comparative studies found that genes for public goods were more likely to be carried on plasmids75,102. One study compared the proportion of genes for secreted proteins on chromosomes and plasmids from 5,397 genomes, and the other study examined the proportion of genes for secreted proteins in plasmid compared to chromosomal genes in the pangenomes of 24 single or multi-species ‘clades’ of bacteria75,102 (Fig. 4A.i.). These supplementary analyses assumed that species, genes and genomes represented independent data points. Inspired by these previous analyses, two recent studies carried out a phylogeny-based analysis across 51 and 146 species, respectively, which found that genes for the production of public goods were not more likely to be on plasmids22,23. Controlling for phylogeny changed the results from significant to non-significant, with the number of genomes per species and phylogeny able to explain 46% and 34% of the variation in the data, respectively. The significant results in the first two studies seem to be an artefact of these particular analyses being biased towards the most commonly sampled species22. Consequently, even when analysing similar datasets, the results depend on whether the number and non-independence of genomes is controlled for. Of note, recent theory has supported the conclusions of the phylogeny-based analyses, by predicting that cooperation is not appreciably favoured by horizontal gene transfer139.

[bH1] Constraints on carbon-fixing enzymes

During photosynthesis, the enzyme rubisco catalyses the fixation of atmospheric carbon dioxide into glucose. Although rubisco is the most abundant enzyme on earth, it is surprisingly inefficient as a catalyst as it also catalyses a wasteful oxygenation reaction alongside the desired carboxylation reaction25,26,140,141. One hypothesis for its inefficiency is that inherent catalytic trade-offs force the oxygenase and carboxylase functions of rubisco to be tightly linked140–142. Early quantitative support for this hypothesis came from a study which looked at rubisco kinetic traits across 27 species and found evidence for a strong trade-off between CO2 specificity and carboxylation turnover, suggesting that the more selective an enzyme is for carbon over oxygen, the slower it is at catalysing the carbon fixation reaction140. A later study examined the same question, with a much larger dataset across 304 diverse species and found further support for the trade-off hypothesis, with a strong, highly significant negative correlation between CO2 specificity and carboxylase turnover141.

However, a re-analysis of the larger dataset using phylogenetic comparative methods reduced the strength of the significant negative correlation between CO2 specificity and carboxylation turnover from 37.4% to just 2.2% variance explained — much less than previously thought, and much less than phylogeny, which explained 56.1% of the variation across all kinetic traits26. Additionally, many proposed trade-offs between other kinetic traits that had support from previous studies disappeared when phylogeny was accounted for26. The authors concluded that the kinetic traits have evolved largely independently of one another, meaning adaptation of rubisco has only been weakly constrained by catalytic trade-offs25,26. This case study provides a clear example of how more data will not alleviate the problem that species cannot be considered as independent data points.

[bH1] Gene expression in orthologs and paralogs

The ‘ortholog conjecture’ states that genes which diverged via a speciation event (orthologs) should remain more similar compared to genes which diverged via a duplication event (paralogs)143. In support of this, one study found that the tissue specificity of ortholog gene expression was more similar than for paralogs across several datasets144.

However, another study re-analysed this data, examining gene expression data from six organs across eight animal species, using phylogenetic comparative methods145. This second study found that, when controlling for evolutionary history and the time since genes diverged, there was no difference between the similarity of genes which had diverged by speciation compared to duplication145. Instead, differences or similarities in gene expression were better explained by phylogenetic distance (i.e. how long since the genes had diverged), rather than whether they had diverged via speciation or duplication145.

Finally, although comparative genomics can provide powerful insights, the success of comparative genomics relies on experiments and observations, both to generate hypotheses and data. Insights from comparative analyses can reveal broad patterns which can then explicitly be tested experimentally. If comparative analyses can increase the chance of choosing the correct target for laboratory work, then this could provide an efficiency benefit by preventing wasted experimental work. Vice versa, experimental insights can generate hypotheses which can then be examined in comparative analyses across species to look for generality. Both approaches have different pros and cons, and the greatest insights can often be made by their combination34.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Grafen, E. Rocha, J. Bouvier, P. Holland and S. Shimeld for useful comments on the manuscript; A. Griffin, J. Turner, L. Bell-Roberts, M. Brindle, M. Liu, R. Bonifacii, S. Kershenbaum and Z. Katz for helpful discussion; and three anonymous reviewers for their feedback. The authors thank the European Research Council (834164) and St John’s College, Oxford for funding.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Binnewies TT, et al. Ten years of bacterial genome sequencing: comparative-genomics-based discoveries. Funct Integr Genomics. 2006;6:165–185. doi: 10.1007/s10142-006-0027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Land M, et al. Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing. Funct Integr Genomics. 2015;15:141–161. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Leary NA, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D733–745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Darwin Tree of Life Project Consortium. Sequence locally, think globally: The Darwin Tree of Life Project. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119:e2115642118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2115642118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt M, Lima L, Shen W, Lees J, Iqbal Z. AllTheBacteria - all bacterial genomes assembled, available and searchable. 2024:2024.03.08.584059. doi: 10.1101/2024.03.08.584059. Preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David S, et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.León-Sampedro R, et al. Pervasive transmission of a carbapenem resistance plasmid in the gut microbiota of hospitalized patients. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:606–616. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00879-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xin X-F, Kvitko B, He SY. Pseudomonas syringae: what it takes to be a pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:316–328. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar SF, Gordon JS, Martin GB, Guttman DS. Comparative Genomics of Host-Specific Virulence in Pseudomonas syringae. Genetics. 2006;174:1041–1056. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Liu Z, Shi P, Zhang J. The hearing gene Prestin unites echolocating bats and whales. Current Biology. 2010;20:R55–R56. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, et al. Convergent sequence evolution between echolocating bats and dolphins. Current Biology. 2010;20:R53–R54. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan Y, et al. Comparative genomics provides insights into the aquatic adaptations of mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118:e2106080118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106080118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruskal W. Miracles and Statistics: The Casual Assumption of Independence. null. 1988;83:929–940. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ives AR, Zhu J. Statistics for correlated data: phylogenies, space, and time. Ecol Appl. 2006;16:20–32. doi: 10.1890/04-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitney KD, G T., Jr Did Genetic Drift Drive Increases in Genome Complexity? PLOS Genetics. 2010;6:e1001080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey PH, Pagel MD. The Comparative Method in Evolutionary Biology. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey PH, Purvis A. Comparative methods for explaining adaptations. Nature. 1991;351:619–624. doi: 10.1038/351619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the Comparative Method. The American Naturalist. 1985;125:1–15. doi: 10.1086/703055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grafen A. The phylogenetic regression. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1989;326:119–157. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1989.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridley M. Why not to use species in comparative tests. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1989;136:361–364. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardison RC. Comparative Genomics. PLOS Biology. 2003;1:e58. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewar AE, et al. Plasmids do not consistently stabilize cooperation across bacteria but may promote broad pathogen host-range. Nat Ecol Evol. 2021;5:1624–1636. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewar AE, Belcher LJ, Scott TW, West SA. Genes for cooperation are not more likely to be carried by plasmids. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2024;291:20232549. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2023.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dewar AE, Hao C, Belcher LJ, Ghoul M, West SA. Bacterial lifestyle shapes pangenomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2024;121:e2320170121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2320170121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouvier JW, Kelly S. Response to Tcherkez and Farquhar: Rubisco adaptation is more limited by phylogenetic constraint than by catalytic trade-off. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2023;287:154021. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2023.154021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouvier JW, et al. Rubisco Adaptation Is More Limited by Phylogenetic Constraint Than by Catalytic Trade-off. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38:2880–2896. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackwell GA, et al. Exploring bacterial diversity via a curated and searchable snapshot of archived DNA sequences. PLOS Biology. 2021;19:e3001421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng S, et al. Dense sampling of bird diversity increases power of comparative genomics. Nature. 2020;587:252–257. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2873-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Upham NS, Landis MJ. Genomics expands the mammalverse. Science. 2023;380:358–359. doi: 10.1126/science.add2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clutton-Brock TH, Harvey PH. Primate ecology and social organization. Journal of Zoology. 1977;183:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clutton-Brock TH, Harvey PH. Comparison and Adaptation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 1979;205:547–565. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridley M. The Explanation of Organic Diversity: The Comparative Method and Adaptations for Mating. Clarendon Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagel M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401:877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies NB, Krebs JR, West SA. An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loos RJF. 15 years of genome-wide association studies and no signs of slowing down. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5900. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19653-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tam V, et al. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:467–484. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray GGR, et al. Genome Reduction Is Associated with Bacterial Pathogenicity across Different Scales of Temporal and Ecological Divergence. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38:1570–1579. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beavan A, Domingo-Sananes MR, McInerney JO. Contingency, repeatability, and predictability in the evolution of a prokaryotic pangenome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2024;121:e2304934120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2304934120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godfroid M, et al. Evo-Scope: Fully automated assessment of correlated evolution on phylogenetic trees. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2024;15:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez J, Klasson L, Welch JJ, Jiggins FM. Life and Death of Selfish Genes: Comparative Genomics Reveals the Dynamic Evolution of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021;38:2–15. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nee S. Birth-Death Models in Macroevolution. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2006;37:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornwallis CK, Griffin AS. A Guided Tour of Phylogenetic Comparative Methods for Studying Trait Evolution. 2024 doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102221-050754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revell LJ, Harmon LJ. Phylogenetic Comparative Methods in R. Princeton University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Revell LJ. Phylogenetic signal and linear regression on species data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2010;1:319–329. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ives AR, Garland T. Phylogenetic logistic regression for binary dependent variables. Syst Biol. 2010;59:9–26. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paradis E, Schliep K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:526–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tung Ho L si, Ané C. A Linear-Time Algorithm for Gaussian and Non-Gaussian Trait Evolution Models. Systematic Biology. 2014;63:397–408. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orme D, et al. CAPER: comparative analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2013;3:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hadfield JD. MCMC Methods for Multi-Response Generalized Linear Mixed Models: The MCMCglmm R Package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pagel M, Meade A. Bayesian Analysis of Correlated Evolution of Discrete Characters by Reversible-Jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo. The American Naturalist. 2006;167:808–825. doi: 10.1086/503444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pagel M, Meade A, Barker D. Bayesian estimation of ancestral character states on phylogenies. Systematic biology. 2004;53:673–684. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bürkner P-C. brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software. 2017;80:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mundry R. Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology: Concepts and Practice. Springer; 2014. Chapter 6 ‘Statistical Issues and Assumptions of Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares’. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Losos JB. Seeing the Forest for the Trees: The Limitations of Phylogenies in Comparative Biology. The American Naturalist. 2011;177:709–727. doi: 10.1086/660020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blomberg SP, Garland T, Ives AR. Testing for Phylogenetic Signal in Comparative Data: Behavioral Traits Are More Labile. Evolution. 2003;57:717–745. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Revell LJ, Harmon LJ, Collar DC. Phylogenetic Signal, Evolutionary Process, and Rate. Systematic Biology. 2008;57:591–601. doi: 10.1080/10635150802302427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergeron LA, et al. Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates. Nature. 2023;615:285–291. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05752-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imrit MA, Dogantzis KA, Harpur BA, Zayed A. Eusociality influences the strength of negative selection on insect genomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2020;287:20201512. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubin BER. Social insect colony size is correlated with rates of molecular evolution. Insect Soc. 2022;69:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruis C, et al. Mutational spectra are associated with bacterial niche. Nat Commun. 2023;14:7091. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42916-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt CDR, et al. Social complexity, life-history and lineage influence the molecular basis of castes in vespid wasps. Nat Commun. 2023;14:1046. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raulo A, et al. Social and environmental transmission spread different sets of gut microbes in wild mice. Nat Ecol Evol. 2024;8:972–985. doi: 10.1038/s41559-024-02381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghoul M, Andersen SB, West SA. Sociomics: Using Omic Approaches to Understand Social Evolution. Trends in Genetics. 2017;33:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Downing T, Angelopoulos N. A primer on correlation-based dimension reduction methods for multi-omics analysis. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2023;20:20230344. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2023.0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hao C, Dewar AE, West SA, Ghoul M. Gene transferability and sociality do not correlate with gene connectivity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2022;289:20221819. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2022.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McNally L, Viana M, Brown SP. Cooperative secretions facilitate host range expansion in bacteria. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4594. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simonet C, McNally L. Kin selection explains the evolution of cooperation in the gut microbiota. PNAS. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016046118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chak STC, Harris SE, Hultgren KM, Jeffery NW, Rubenstein DR. Eusociality in snapping shrimps is associated with larger genomes and an accumulation of transposable elements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118:e2025051118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025051118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grafen A, Hails R, Grafen A, Hails R. Modern Statistics for the Life Sciences. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zoonomia Consortium. A comparative genomics multitool for scientific discovery and conservation. Nature. 2020;587:240–245. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2876-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lloyd-Price J, et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature. 2017;550:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature23889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duarte CM, et al. Sequencing effort dictates gene discovery in marine microbial metagenomes. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:4589–4603. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arikawa K, Hosokawa M. Uncultured prokaryotic genomes in the spotlight: An examination of publicly available data from metagenomics and single-cell genomics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:4508–4518. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2023.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rhie A, et al. Towards complete and error-free genome assemblies of all vertebrate species. Nature. 2021;592:737–746. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia-Garcera M, Rocha EPC. Community diversity and habitat structure shape the repertoire of extracellular proteins in bacteria. Nature Communications. 2020;11:758. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14572-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shaw LP, et al. Niche and local geography shape the pangenome of wastewater- and livestock-associated Enterobacteriaceae. Science Advances. 2021;7:eabe3868. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaw LP, Rocha EPC, MacLean RC. Restriction-modification systems have shaped the evolution and distribution of plasmids across bacteria. Nucleic Acids Research. 2023;51:6806–6818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hall RJ, et al. Gene-gene relationships in an Escherichia coli accessory genome are linked to function and mobility. Microbial Genomics. 2021;7:000650. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whelan FJ, Hall RJ, McInerney JO. Evidence for selection in the abundant accessory gene content of a prokaryote pangenome. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu E-Z, Lan X-R, Liu Z-L, Gao J, Niu D-K. A positive correlation between GC content and growth temperature in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:110. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haudiquet M, et al. Capsules and their traits shape phage susceptibility and plasmid conjugation efficiency. Nat Commun. 2024;15:2032. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rendueles O, de Sousa JAM, Bernheim A, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Genetic exchanges are more frequent in bacteria encoding capsules. PLOS Genetics. 2018;14:e1007862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rendueles O, Garcia-Garcerà M, Néron B, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Abundance and co-occurrence of extracellular capsules increase environmental breadth: Implications for the emergence of pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006525. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garamszegi LZ. Chapter 8 in Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology: Concepts and Practice. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pagel M. Detecting Correlated Evolution on Phylogenies: A General Method for the Comparative Analysis of Discrete Characters. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 1994;255:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boyko JD, Beaulieu JM. Generalized hidden Markov models for phylogenetic comparative datasets. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2021;12:468–478. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harmon LJ. Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Learning from Trees. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 88.van der Bijl W. phylopath: Easy phylogenetic path analysis in R. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4718. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.von Hardenberg A, Gonzalez-Voyer A. Disentangling Evolutionary Cause-Effect Relationships with Phylogenetic Confirmatory Path Analysis. Evolution. 2013;67:378–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cornwell W, Nakagawa S. Phylogenetic comparative methods. Curr Biol. 2017;27:R333–R336. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cornwallis CK, et al. Cooperation facilitates the colonization of harsh environments. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Frígols B, et al. Virus Satellites Drive Viral Evolution and Ecology. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11:e1005609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gavriilidou A, et al. Goldfinder: Unraveling Networks of Gene Co-occurrence and Avoidance in Bacterial Pangenomes. 2024:2024.04.29.591652. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.29.591652. Preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leeks A, Young PG, Turner PE, Wild G, West SA. Cheating leads to the evolution of multipartite viruses. PLOS Biology. 2023;21:e3002092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hu Z, Sackton TB, Edwards SV, Liu JS. Bayesian Detection of Convergent Rate Changes of Conserved Noncoding Elements on Phylogenetic Trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2019;36:1086–1100. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eastman JM, Alfaro ME, Joyce P, Hipp AL, Harmon LJ. A novel comparative method for identifying shifts in the rate of character evolution on trees. Evolution. 2011;65:3578–3589. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garamszegi LZ. Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology: Concepts and Practice. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coluzzi C, Garcillán-Barcia MP, de la Cruz F, Rocha EPC. Evolution of Plasmid Mobility: Origin and Fate of Conjugative and Nonconjugative Plasmids. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2022;39:msac115. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msac115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Acman M, van Dorp L, Santini JM, Balloux F. Large-scale network analysis captures biological features of bacterial plasmids. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2452. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16282-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Matlock W, et al. Genomic network analysis of environmental and livestock F-type plasmid populations. ISME J. 2021;15:2322–2335. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-00926-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adams R, et al. A tale of too many trees: a conundrum for phylogenetic regression. 2024:2024.02.16.580530. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaf032. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nogueira T, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Rapid Evolution of the Sequences and Gene Repertoires of Secreted Proteins in Bacteria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maddamsetti R, et al. Duplicated antibiotic resistance genes reveal ongoing selection and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1449. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pagel MD, Harvey PH. Recent Developments in the Analysis of Comparative Data. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 1988;63:413–440. doi: 10.1086/416027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biology. 2019;20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Whelan FJ, Rusilowicz M, McInerney JO. Coinfinder: detecting significant associations and dissociations in pangenomes. Microb Genom. 2020;6:e000338. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bernheim A, Bikard D, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Atypical organizations and epistatic interactions of CRISPRs and cas clusters in genomes and their mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020;48:748–760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kowalczyk A, et al. RERconverge: an R package for associating evolutionary rates with convergent traits. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4815–4817. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Read AF, Nee S. Inference from binary comparative data. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1995;173:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maddison WP, FitzJohn RG. The Unsolved Challenge to Phylogenetic Correlation Tests for Categorical Characters. Systematic Biology. 2015;64:127–136. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kyriacou RG, Mulhair PO, Holland PWH. GC Content Across Insect Genomes: Phylogenetic Patterns, Causes and Consequences. J Mol Evol. 2024;92:138–152. doi: 10.1007/s00239-024-10160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Boettiger C, Coop G, Ralph P. Is your phylogeny informative? Measuring the power of comparative methods. Evolution. 2012;66:2240–2251. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Uyeda JC, Zenil-Ferguson R, Pennell MW. Rethinking phylogenetic comparative methods. Systematic Biology. 2018;67:1091–1109. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gupta A, Kapil R, Dhakan DB, Sharma VK. MP3: A Software Tool for the Prediction of Pathogenic Proteins in Genomic and Metagenomic Data. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e93907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Belcher LJ, et al. SOCfinder: a genomic tool for identifying social genes in bacteria. Microbial Genomics. 2023;9:001171. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Belcher LJ, Dewar AE, Ghoul M, West SA. Kin selection for cooperation in natural bacterial populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119:e2119070119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119070119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Szucs D, Ioannidis JPA. When Null Hypothesis Significance Testing Is Unsuitable for Research: A Reassessment. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:390. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cohen J. The earth is round (p < .05) American Psychologist. 1994;49:997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tukey JW. The Philosophy of Multiple Comparisons. Statistical Science. 1991;6:100–116. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using Effect Size—or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:279–282. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jennions MD, Møller AP. A survey of the statistical power of research in behavioral ecology and animal behavior. Behavioral Ecology. 2003;14:438–445. [Google Scholar]

- 124.West S. Sex Allocation. Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 125.West SA, Shuker DM, Sheldon BC. Sex-Ratio Adjustment When Relatives Interact: A Test of Constraints on Adaptation. Evolution. 2005;59:1211–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cornwallis CK, et al. Symbioses shape feeding niches and diversification across insects. Nat Ecol Evol. 2023;7:1022–1044. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02058-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Harvey PH, Read AF, Nee S. Why Ecologists Need to be Phylogenetically Challenged. The Journal of Ecology. 1995;83:535. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Harvey PH, Read AF, Nee S. Further Remarks on the Role of Phylogeny in Comparative Ecology. Journal of Ecology. 1995;83:733–734. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Garland T, Ives AR. Using the Past to Predict the Present: Confidence Intervals for Regression Equations in Phylogenetic Comparative Methods. Am Nat. 2000;155:346–364. doi: 10.1086/303327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nakagawa S, Johnson PCD, Schielzeth H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface. 2017;11 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ives AR. R$^{2}$s for Correlated Data: Phylogenetic Models, LMMs, and GLMMs. Systematic Biology. 2019;68:234–251. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Beaulieu JM, O’Meara BC, Donoghue MJ. Identifying Hidden Rate Changes in the Evolution of a Binary Morphological Character: The Evolution of Plant Habit in Campanulid Angiosperms. Systematic Biology. 2013;62:725–737. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bell-Roberts L, et al. Larger colony sizes favoured the evolution of more worker castes in ants. Nat Ecol Evol. 2024:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41559-024-02512-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Parks DH, et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Research. 2022;50:D785–D794. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Downing T, Rahm A. Bacterial plasmid-associated and chromosomal proteins have fundamentally different properties in protein interaction networks. Sci Rep. 2022;12:19203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A, Diggle SP. Social evolution theory for microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:597–607. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Smith J. The social evolution of bacterial pathogenesis. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2001;268:61–69. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mc Ginty SÉ, Lehmann L, Brown SP, Rankin DJ. The interplay between relatedness and horizontal gene transfer drives the evolution of plasmid-carried public goods. Proc R Soc B. 2013;280:20130400. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Scott TW, West SA, Dewar AE, Wild G. Is cooperation favored by horizontal gene transfer? Evolution Letters. 2023;7:113–120. doi: 10.1093/evlett/qrad003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T. Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:3475–3480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911663107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Flamholz AI, et al. Revisiting Trade-offs between Rubisco Kinetic Parameters. Biochemistry. 2019;58:3365–3376. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tcherkez GGB, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:7246–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Koonin EV. Orthologs, Paralogs, and Evolutionary Genomics. Annual Review of Genetics. 2005;39:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kryuchkova-Mostacci N, Robinson-Rechavi M. Tissue-Specificity of Gene Expression Diverges Slowly between Orthologs, and Rapidly between Paralogs. PLOS Computational Biology. 2016;12:e1005274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Dunn CW, Zapata F, Munro C, Siebert S, Hejnol A. Pairwise comparisons across species are problematic when analyzing functional genomic data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018;115:E409–E417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707515115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.