Abstract

The success of prime editing depends on the pegRNA design and target locus. Here, we developed machine learning models that reliably predict prime editing efficiency. PRIDICT2.0 assesses the performance of pegRNAs for all edit types up to 15 base pairs in mismatch repair-deficient and -proficient cell lines and in vivo in primary cells. With ePRIDICT, we further developed a model that quantifies how local chromatin environments impact prime editing rates.

The efficiency of prime editing can vary considerably across different target sites and is heavily influenced by the design of the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). Our team1 and other researchers2–4 have previously developed machine learning models trained on extensive prime editing datasets to predict pegRNA efficiencies. A shared limitation of these models is their specialization in predicting certain edit types: DeepPrime4 is limited to 1-3 bp edits, MinsePIE3 is confined to certain insertions, and PRIDICT1 primarily focuses on 1 bp replacements as well as short insertions and deletions (ExtFig1a). Furthermore, each of these models does not account for the potential influence of the local chromatin state on editing rates. In this study, we addressed these shortcomings by developing two complementary computational models. 'PRIDICT2.0' predicts prime editing efficiency across a wide spectrum of edit types, and 'ePRIDICT' (epigenetic-based PRIme editing efficiency preDICTion) assesses the influence of locus-specific chromatin features on prime editing.

To generate prime editing prediction models that can anticipate a wide range of edit types, we constructed a highly diverse target-matched pegRNA library (Library-Diverse), which includes 1-5 bp replacements, 1-15 bp insertions and deletions, and pairs of simultaneously encoded single base replacements at variable distances (ExtFig1b). Given that the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway influences prime editing rates5,6, we conducted our initial screens in both MMR-deficient (HEK293T)7 and MMR-proficient (K562)8 cells. Cells with stably integrated Library-Diverse were transfected with plasmids expressing the prime editor, followed by deep amplicon sequencing to analyze editing rates with different pegRNAs (Fig1a, ExtFig1c). Demonstrating the robustness of the generated datasets, we observed high correlations in editing efficiencies between replicates (Spearman (R)=0.97/Pearson (r)=0.99 for HEK293T and R=0.84/r=0.96 for K562; ExtFig1d,e). Next, we assessed differences in the efficiency of installing diverse edit types in HEK293T and K562 cells. In line with the hypothesis that MMR has a negative effect on short edits, we observed contrasting editing patterns between the two cellular contexts. In HEK293T, the efficiency of installing insertions gradually declined with increasing lengths (Fig1b), whereas in K562 cells, editing rates were most efficient for insertions with a length of 4-5bp (Fig1c). Likewise, the length of replacements had minimal impact on the editing efficiency in HEK293T cells (Fig1d), while in K562 cells, 3-5 bp long replacements were more efficiently installed than 1-2bp replacements (Fig1e). Interestingly, for installing deletions, we observed a similar pattern as for insertions in HEK293T cells, with an inverse correlation between the edit length and efficiency (Fig1f), whereas in K562 cells editing rates remained consistently low regardless of the length of the deletion (Fig1g). We then investigated whether incorporating additional 1bp replacements to the intended edit could reduce MMR recognition and thereby elevate editing rates, as suggested previously5. While in our initial analysis we did not observe a notable difference in editing rates between single- and double edits in both HEK293T and K562 cells (Fig1h,i), a position-specific analysis revealed that introducing a co-edit within the GG PAM sequence substantially improved the editing efficiency of 1bp replacements that are situated outside of the PAM (Fig1j,k). Notably, we also observed that double edits located further apart frequently lead to intermediate editing, where only one of the two edits is installed (Fig1h,i).

Fig. 1. Characterization and prediction of pegRNA efficiencies based on sequence context.

(a) Schematic overview of the screen with the target-matched pegRNA library 'Library Diverse'. (b-g) Editing efficiency for (b,c) insertions, for (d,e) 1-5bp replacements, and (f,g) 1-15 bp deletions in HEK293T and K562, respectively. (h,i) Editing efficiencies in HEK293T (h) or K562 (i) cells for double edits where 2 separated 1 bp replacements were installed. Intended editing means that both replacements were installed, whereas intermediate editing means that only 1 of the 2 replacements was installed. Distance of 0 corresponds to single 1 bp edits. (j,k) Editing efficiency of single and double 1 bp replacements with or without editing of at least 1 base within the GG PAM sequence in HEK293T (j) and K562 (k) cells. (d,e,h-k) Bars include only pegRNAs with 7, 10, or 15 bp RTT overhang to ensure similar RTT overhang distributions between conditions. (b-k) Bars show mean with error bar indicating mean +/- s.e.m. (l,m) Heatmap visualizing editing efficiency of pegRNAs (single base replacements) in Library-Diverse with different RTT overhang lengths and edit positions in HEK293T (l; n = 3,079) and K562 (m, n = 3,091). PAM position is highlighted with black dotted rectangle. (n) Schematic illustration of PRIDICT2.0, which is an ensemble model based on the prediction average of two models: (Model A), base trained on Library 11 and fine-tuned on Library-Diverse (HEK293T and K562), and (Model B), base trained on Library 11 and Library-ClinVar4 and again fine-tuned on Library-Diverse. The number of pegRNAs in each dataset is indicated above or below the datasets. (o,p) Performance of PRIDICT2.0 on Library-Diverse (5-fold cross-validation) for (o) HEK293T (n = 22,619) and (p) K562 (n = 22,752) cells. Color gradient from dark purple to yellow indicates increasing point density, per Gaussian KDE. The black line corresponds to the least-squares polynomial fit. (q) Spearman correlations of editing efficiency in Library-Diverse in different contexts (HEK293T, K562, K562-MLH1dn, and in vivo mouse liver), and with PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T and K562 prediction scores. (r,s) SHAP analysis on a Library-Diverse test dataset of an XGBoost model (top fifteen features). A high SHAP value associates with higher editing prediction. Feature values correspond to the values of each individual feature. Detailed list of all features is listed in Supplementary Table 1. The number of analyzed pegRNA-target combinations are as follows. b, n = 408, 519, 541, 446, 447, 416, 433, 446, 432, 424, 361, 373, 359, 332, 346. c, n = 410, 525, 546, 445, 448, 414, 434, 444, 434, 426, 364, 375, 360, 331, 346. d, n = 5,146, 834, 638, 538, 576. e, n = 5,158, 844, 644, 554, 575. f, n = 424, 475, 388, 367, 406, 420, 380, 418, 405, 408, 391, 375, 365, 340, 362. g, n = 420, 476, 394, 373, 409, 420, 385, 416, 411, 409, 391, 385, 370, 348, 366. h, n = 5,146, 834, 153, 71, 191, 136, 27, 141, 155, 26, 185. i, n = 5,158, 844, 150, 71, 186, 137, 31, 142, 162, 28, 193. j, n = 4,606, 474, 2,818, 820. k, n = 4,606, 474, 2,818, 820.

Next, we trained different machine learning models on the prime editing data generated with 'Library-Diverse' in HEK293T and K562 cells. Benchmarking their performance, we found that the attention-based bidirectional recurrent neural network (AttnBiRNN) model surpassed tree-based and linear regression models (ExtFig2a-d). To further increase the robustness of the model to other experimental settings, we next augmented the training data with additional datasets obtained from other target-matched pegRNA library screens ('Library 1'1, 'Library-ClinVar'4). The applied AttnBiRNN model extends on the architecture of our previous PRIDICT1 model, and uses a simultaneous training strategy to predict prime editing efficiencies in HEK293T and K562 cells after fine-tuning on the 'Library-Diverse' datasets (Fig1n, Supplementary Figure 1). The final model, termed PRIDICT2.0, was in total trained on over 400,000 pegRNAs and achieved a correlation of R=0.91/r=0.90 in HEK293T cells (Fig1o) and R=0.81/r=0.70 in K562 cells (Fig1p).

Given that optimal pegRNA designs can differ between MMR-proficient K562 cells and MMR-deficient HEK293T cells, we next investigated the performance of PRIDICT2.0 on prime editing datasets generated in i) K562 cells where the MMR pathway was suppressed by co-delivering a dominant negative MLH1 construct (MLH1dn – PE4 approach5), and ii) in vivo in mouse hepatocytes with functional MMR (ExtFig1f,g). In the latter experiment, we employed integrating AAV/Sleeping Beauty vectors to deliver Library-Diverse into the mouse liver (see methods for details) concurrently to treatment with an adenoviral vector expressing the prime editor under a hepatocyte-specific promoter9. It is important to note, however, that not all AAVs may have been integrated by the Sleeping Beauty transposase, and editing quantification may also include target sites on AAV episomes.

Editing patterns in K562-MLH1dn cells closely mirrored those observed in MMR-deficient HEK293T cells (ExtFig3a-f), as evidenced by the high correlation between both datasets (R=0.96; Fig1q). In line with these results, we also observed superior predictive accuracy of the PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T model compared to the PRIDICT2.0 K562 model on this dataset (R=0.88 vs. R=0.83, respectively).

While in vivo prime editing datasets showed higher variability between individual replicates, prime editing patterns more closely resembled the K562 dataset (ExtFig3g-l), and editing rates were better predicted by PRIDICT2.0 K562 (R=0.70 vs. R=0.62 for PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T). Based on these results, we advise to employ PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T for prime editing in MMR-deficient cells and PRIDICT2.0 K562 for prime editing in MMR-proficient cells.

To further investigate the importance of different features for predicting pegRNA efficiencies, we performed Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis10 on XGBoost11 models trained on Library-Diverse datasets generated in HEK293T and K562 cells (Fig1r,s; Supplementary Figures 2,3). SHAP analysis quantitatively assesses the impact of each feature on the model’s predictions, offering a detailed understanding of how different features contribute to pegRNA editing efficiency. In HEK293T cells, the most relevant features included the type of edit (with replacements showing the highest efficiency), edit length (shorter edits being more efficient), presence of consecutive T bases (polyT) in the spacer/extension sequence, and the length of the RTT overhang (Fig1r). In contrast, in K562 cells, the most important features were edit position (editing was less efficient at positions distal of the nick), melting temperature, and GC content of the edited base(s) (the bases that are introduced by the edit).

Next, we benchmarked PRIDICT2.0 to our previously developed prime editing prediction model, PRIDICT1. Importantly, PRIDICT2.0 demonstrated superior performance over PRIDICT1 when tested on the 'Library-Diverse' datasets in both HEK293T and K562 cells (HEK293T – PRIDICT R=0.83, PRIDICT2.0 R=0.91; K562 – PRIDICT R=0.64, PRIDICT2.0 R=0.81; Fig2a). When analyzing edit types separately, PRIDICT2.0 showed the biggest improvements in K562 cells and for multi-base replacements and deletions (Fig2b,c, ExtFig2e,f). To further evaluate the factors contributing to the increase in model performance (e.g., optimization in model architecture, fine-tuning on 'Library-Diverse', or training on additional pegRNAs from Yu et al.4, see Fig1n), we also trained the AttnBiRNN model architecture of PRIDICT2.0 solely on Library 1 from Mathis et al.1, or solely on Library 1 plus Library-ClinVar from Yu et al.4 without fine-tuning on Library-Diverse. Confirming an improvement in the AttnBiRNN model architecture, we already observed slightly better performance in comparison to PRIDICT when the updated model architecture was only trained on Library 1. Additional training of the model on Library-ClinVar only marginally enhanced the performance, while fine-tuning on 'Library-Diverse' accounted for the largest increase in model performance (ExtFig2g).

Fig. 2. Validation of PRIDICT2.0 predictions in different contexts and in comparison to existing models.

(a-d) Performance of editing efficiency prediction by PRIDICT and PRIDICT2.0. PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T prediction is used for HEK293T, and K562 prediction is used for K562. (a) Overall performance in HEK293T (n=22,619) and K562 (n=22,752). (b) Performance split by different edit types and cell types (n from top to bottom: 5,957, 4,455, 6,283, 5,924, 5,969, 4,508, 6,302, 5,973). (c) Performance on insertions and deletions with different lengths. n for different edit lengths combined are as follows: HEK293T insertions: 6,283, HEK293T deletions: 5,924, K562 insertions: 6,302, K562 deletions: 5,973. (d) Performance on endogenous editing datasets1,12,13. n for Mathis et al. 20231 = 45, n for Anzalone et al.12 2019 = 181, n for Brooks et al. 202313 = 59. The tested dataset from Brooks et al. consists of all editing efficiencies from their “insertion set” and “correction set #1, #2a, #2b, and #3” combined. All Brooks et al. pegRNAs were used in a PE55 (PEmax + nicking guide + MLH1 inhibition) setting. (e) Overview of the capability to predict different edit types of the prime editing efficiency prediction models PRIDICT2.0, DeepPrime4, and MinsePIE3. Green = prediction possible, Bright-green = prediction possible with limitations, Red = prediction not possible. *1: PRIDICT2.0 was trained on insertions <= 15 bp. *2: MinsePIE3 prediction is restricted to insertions at the nick position, and the model was originally built to predict relative insertion efficiencies for different insertion sequences within a specific target with constant PBS/RTT overhang. (f) Prediction performance of PRIDICT2.0 (HEK293T and K562) on Library-Small4 filtered for NGG PAM in various editing contexts (n for each column from left to right: 2,181, 2,109, 1,637, 2,200, 2,161, 1,926, 2,133, 2,152, 2,182, 1,909, 1,972, 2,023, 2,208, 2,178, 2,066, 2,040, 2,181, 2,128). (g) Prediction performance of DeepPrime4 models on Library-Diverse (this study) filtered for edits <= 3bp (n for each column from left to right: 10,715, 10,761, 9,653, 8,609) (h,i) Comparison of different prediction models by predicting endogenous loci. DePr = DeepPrime. (h) Editing datasets in HEK293T. Mathis: Endogenous editing dataset (PE2) from Mathis et al.1, filtered for <= 3bp edits. Yu-1: Endogenous dataset (PE2max) from Figure S2E in Yu et al.4 Yu-2: Endogenous dataset from BRCA2 pegRNAs (PE2max) in Figure 6F,G from Yu et al. 4 Anza: Endogenous dataset with PE2 editing from Anzalone et al.12 n (for each column from left to right): 42, 39, 24, 181. (i) Editing datasets in K562 (Mathis et al. 2023, PE2, filtered for <=3 bp edits; n = 42) and HuH-7 cells. Brooks et al. dataset consists of all editing efficiencies from their “insertion set” and “correction set #1, #2a, #2b, and #3” combined (n = 59; PE5 setting).

For further validation of PRIDICT2.0, we next applied the model on previously established prime editing datasets, where different endogenous loci were edited (Fig2d). First, we tested the performance on a dataset from Mathis et al.1, where 15 endogenous loci were targeted with a total of 45 pegRNAs in HEK293T and K562 cells. As the majority of edits in this dataset were 1bp replacements, the performance of PRIDICT2.0 in HEK293T cells was similar to PRIDICT, with R/r values of 0.80/0.66 vs. R=0.81/r=0.691 (Fig2d, Supplementary Figure 4a-d). However, in K562 cells, PRIDICT2.0 outperformed PRIDICT, achieving an R=0.85/r=0.61 (Fig2d, Supplementary Figure 4e-h) compared to R=0.69/r=0.481. In addition, PRIDICT2.0 surpassed PRIDICT on a prime editing dataset generated in HEK293T cells by Anzalone et al.12 (PRIDICT2.0: R=0.69/r=0.63 vs. PRIDICT R=0.47/r=0.471; Fig2d, Supplementary Figure 4i-l), and on a prime editing dataset generated in HuH-7 cells with PE55 by Brooks et al.13 (PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T R=0.55/r=0.59, PRIDICT2.0 K562 R=0.73, 0.72, PRIDICT R=0.47, 0.45; Fig2d, Supplementary Figure 4m-r).

Yu et al.4 recently introduced DeepPrime, another machine learning model capable of predicting pegRNA efficiencies. In contrast to PRIDICT2.0, DeepPrime is capable of predicting pegRNAs targeting non-NGG PAM sequences, but is limited to edits up to 3bp in length (Fig2e). To compare DeepPrime and PRIDICT2.0, we tested the performance of both models on each other's datasets. First, we applied PRIDICT2.0 on Library-Small datasets from Yu et al., filtered for pegRNAs targeting NGG PAMs (54% of Library-Small). We observed robust performance in different cell lines, with Spearman correlations up to 0.78 for HEK293T cells and up to 0.76 for other cell lines (Fig2f). When we next applied the different DeepPrime models on the 'Library-Diverse' datasets, filtered for <= 3bp edits (47% of Library-Diverse), we also observed solid correlations in cell lines (up to R = 0.74 in the HEK293T; R = 0.65 in K562; and R = 0.72 in K562-MLH1dn), but slightly lower performance in the mouse liver (up to R = 0.54) (Fig2g). In line with these results, PRIDICT2.0 and DeepPrime showed similar performance on prime editing datasets at endogenous loci (Mathis et al.1, Yu et al.4, and Anzalone et al.12, filtered for <=3bp edits), with higher correlations on internally generated datasets (Fig2h,i). Of note, we also tried to benchmark PRIDICT2.0 to MinsePIE3, a machine-learning model built to predict the relative frequency of installing different insertions into specific sites. However, since the model was not trained on a large variety of target sites with differing PBS and RTT overhang lengths, its performance on the Library-Diverse and Library-Small datasets was limited (Supplementary Figure 5). In summary, our comparative analysis reveals a similar performance of PRIDICT2.0 and DeepPrime, with DeepPrime having the added capability of predicting non-NGG PAM sites and PRIDICT2.0 being able to also predict edit types above 3bp.

Previous research using SpCas9 has shown that genome editing rates are influenced not only by the sequence of the target locus but also by the chromatin environment14–18. To systematically explore a potential influence of chromatin on prime editing, we utilized the TRIP (Thousands of Reporters Integrated in Parallel) technology19 (Fig3a, b). A 640 bp TRIP reporter construct, which was shown to adopt the local chromatin environment14, was inserted into K562 cells using Piggy-Bac transposition and mapped by tagmentation PCR followed by NGS. Integration sites were widely distributed across all chromosomes (Fig3c) and most frequently mapped to genic regions (Fig3d). In the next step, we retrieved 455 publicly available ENCODE20 datasets for K562 cells, which include information on chromatin modification/accessibility and transcription factor binding (Fig3e). For each location, we averaged signals across different-sized windows from 100 to 5000 bp up- and downstream of each location (Fig3f). We then transfected the cell pool with plasmids expressing the prime editor together with a pegRNA targeting the integrated construct (1182 mapped locations). To assess potential differences in chromatin effects to other commonly used genome editing techniques, we separately treated cells with an adenine base editor (ABE8e; 1169 mapped locations), cytosine base editor (BE4max; 1194 mapped locations), and a conventional Cas9 nuclease (SpCas9; 1196 mapped locations). By first adjusting the experimental conditions, we ensured that the editing rates followed a bell-curved distribution, with mean values ranging from 40% to 70% (ExtFig4a-d). Confirming the robustness of the experimental setup, we observed a strong correlation in editing efficiencies between individual screening replicates, with a Pearson (r) correlation of >0.93 for PE, >0.85 for ABE8e, >0.95 for BE4max and >0.87 for Cas9 (ExtFig4e-h). Notably, comparing different genome editors also revealed a strong correlation of PE with ABE8e (R=0.69/r=0.76) and BE4max (R=0.72/r=0.78), but only a moderate correlation with Cas9 (R=0.4, r=0.44) (ExtFig4i,j).

Fig. 3. Characterization and prediction of prime editing efficiency based on chromatin context.

(a) Schematic illustration of the TRIP library integrated by PiggyBac. TR: Terminal Repeats. (b) Schematic illustration of the TRIP screen in K562 cells. (c) Overview of TRIP reporter insertion locations with mapped prime editing efficiencies in the K562 genome. n = 1,182. (d) Context of the TRIP reporter integration sites. (e) Schematic illustration of all ENCODE datasets of K562 used in this study. TF: Transcription Factors. The number of different features is indicated, with the total number of datasets (accounting for multiple ENCODE contributions per feature) given in brackets. Total number of datasets: 455. (f) Illustration of averaging windows (100, 1,000, 2,000, and 5,000 bp) around mapped integrations over which chromatin datasets (ENCODE) are averaged for further analysis. (g) Overall Pearson correlation of a selection of chromatin characteristics (25/455) to editing efficiency (PE/prime editing, ABE8e, BE4max, and Cas9) across the TRIP library. The averaging window with the highest absolute correlation value with PE editing is shown for each feature. (h) UMAP projection based on all 455 ENCODE datasets and averaging windows of the TRIP library. Prime editing efficiency is shown via color scale. n = 1,165. (i) KMeans clustering on UMAP projection to cluster integrations into 4 groups (A to D). n = 1,165. (j) Average editing efficiency of integrations in each KMeans cluster for PE, ABE8e, BE4max, and Cas9. n per cluster: 380 (A), 267 (B), 349 (C), 169 (D). (k) Comparison of machine learning model performances on editing efficiency prediction with ePRIDICT on the TRIP library in K562 cells. Bars show the mean of fivefold cross-validation, and each of the five cross-validations is visualized as individual data points (n=5). Error bar indicates the mean +/- s.d. (l) Visualization of ePRIDICT XGBoost model predictions on PE TRIP library dataset (n = 1,182). Predictions from 5 cross-validations were combined for visualization. Color gradient from dark purple to yellow indicates increasing point density, per Gaussian KDE. Dotted line: least-squares polynomial fit. (m) Validation of prime editing efficiency on endogenous loci with a high (>50) or low (<35) ePRIDICT score normalized to editing on the reporter sequence for 1bp replacements (in green; n-high: 9, n-low: 10), 4bp insertions (in blue; n-high: 9, n-low: 9) and 4bp deletions (in orange; n-high: 9, n-low: 10). Boxplots represent the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers extend to points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the quartiles. (n) Endogenous editing in K562 with a total of 146 pegRNAs (56 pegRNAs from m and 90 additional pegRNAs) compared to PRIDICT2.0 K562 score. Dotted line: least-squares polynomial fit. (o) Comparison of pegRNAs in n to combination (mean) of the PRIDICT2.0 K562 score and ePRIDICT score. Dotted line: least-squares polynomial fit. (p) Additional visualization of the prediction performance of PRIDICT2.0 alone or in combination with ePRIDICT (average of prediction values from both models) on 41 different endogenous loci with highly variable chromatin characteristics, targeted with 146 pegRNAs in K562 cells.

When we next analyzed the correlation between frequently studied chromatin features and editing efficiency, we observed that features correlating with open chromatin or active genes (such as ATAC-seq, HDAC1/2/3, or H3K4me1/2/3)21–23 positively correlated with editing rates (Fig3g). In contrast, repressive marks (H3K9me3, H3K27me3)24,25 were negatively correlated. For a more detailed analysis of different chromatin contexts, we performed UMAP projection26 using the extracted chromatin features of mapped genomic locations. When overlaying this projection with editing efficiency, we observed a low to high efficiency gradient, with locations resembling each other's chromatin landscape (closer in the UMAP) having similar efficiencies (Fig3h, ExtFig5a-c). Further analysis of locus characteristics of the UMAP projection by grouping locations into 4 clusters (K-means; Fig3i) showed a similar pattern for different editors (PE, ABE8e, BE4max, and Cas9), with cluster A having the highest efficiency and cluster D the lowest (Fig3j). Cluster A was enriched in the active marks H3K4me3, H3K4me2, and H3K27ac, while showing a reduction in the repressive mark H3K27me3. This profile resembled a promoter-like environment23 (ExtFig5d). Cluster B had elevated levels of H3K36me3 and POLR2A and was reduced in the active mark H3K4me3, suggesting characteristics of transcriptional elongation within gene bodies27 (ExtFig5e). Cluster C showed increased levels of repressive H3K27me3 and CTCF and was reduced in active marks H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, indicative of repressed or insulated chromatin24 (ExtFig5f). Cluster D, with the lowest editing efficiency, had a slight elevation in the repressive mark H3K9me3 and was notably depleted in both active and elongation-associated marks, pointing to a more heterochromatic or repressed state25 (ExtFig5g).

In a subsequent step, we trained an array of linear and tree-based machine learning models to predict the influence of chromatin characteristics on prime editing efficiency (Fig3k). The model showing the highest correlations between predicted and experimentally observed editing rates is based on the XGBoost framework (Fig3l, R = 0.67, r=0.75) and was termed 'ePRIDICT' for epigenetic-based PRIme editing efficiency pre-DICTion. To next optimize the model for enhanced computational efficiency, we developed ePRIDICT-light, which is again based on the XGBoost framework but trained exclusively on 6 ENCODE datasets that showed high feature importance in ePRIDICT (HDAC2, H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and DNase-seq). Despite requiring fewer computational resources, ePRIDICT-light performed with similar accuracy to ePRIDICT, achieving R = 0.65 and r = 0.73 (ExtFig5h). Of note, we also developed XGBoost models for base editing and Cas9-mediated genome editing. The base editor models performed similarly to ePRIDICT, with correlations of R = 0.69/r = 0.75 for ABE8e and R = 0.7/r = 0.75 for BE4max. In contrast, the performance of the Cas9 model was substantially lower (R = 0.33/r = 0.35) (ExtFig5i). This could be due to the higher activity of Cas9 cleavage, leading to a saturation of editing rates in our dataset (ExtFig4d), or due to the possibility that chromatin marks affecting Cas9 double-strand cleavage in our dataset are not adequately represented in ENCODE datasets.

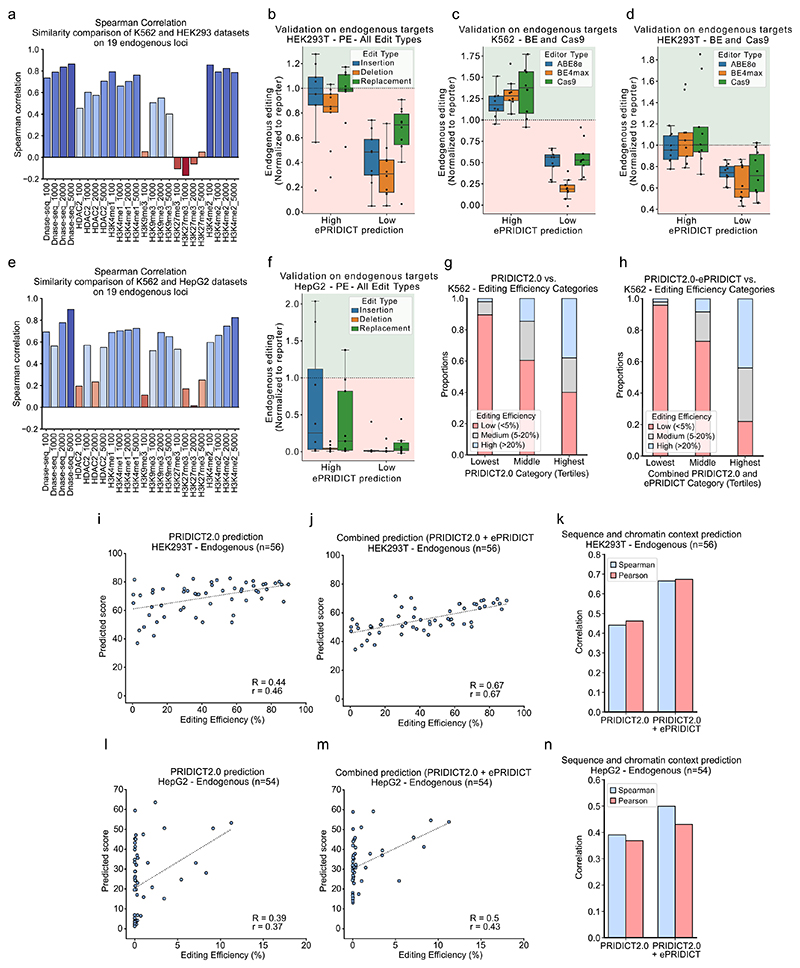

For further validation of ePRIDICT, we also applied the model on a recently generated independent prime editing dataset28. Similar to our study, Li et al.28 performed prime editing on a single target site that was integrated into different genomic loci in K562 cells. Despite introducing another edit type (insertion instead of transversion) and targeting a different sequence, ePRIDICT reached a correlation of R=0.53 and r=0.51 (ExtFig5j). Next, we validated ePRIDICT on endogenous loci by selecting 19 genomic sites with varying ePRIDICT values. We first integrated cassettes containing the targeted sequences into K562 cells via PiggyBac transposition (MOI > 1) and then treated these cell lines with the prime editor and locus-specific pegRNAs installing replacements, insertions and deletions. This allowed us to directly compare prime editing rates on endogenous loci vs. the identical sequences integrated randomly via PiggyBac transposition. Importantly, we found that loci with high ePRIDICT scores (>50) showed higher editing rates at endogenous loci compared to integrated cassettes, whereas loci with low ePRIDICT scores (<35) showed lower editing at endogenous loci (Fig3m). Next, we performed the same validation experiment in HEK293T and HepG2 cells, which both exhibit a similar chromatin landscape to K562 cells at the 19 targeted loci (ExtFig6a,e). We again observed higher relative editing rates at loci with high- vs. low ePRIDICT scores (ExtFig6b,f), suggesting that the influence of chromatin on the activity of genome editors is generalizable and that ePRIDICT could also be applied to other cell types in case chromatin characteristics at the targeted region are conserved. Additionally, we observed a similar pattern in editing rates between endogenous loci and integrated cassettes when K562 and HEK293T cell lines were treated with base editors or Cas9 (ExtFig6c,d).

Finally, we investigated whether ePRIDICT could elevate the performance of PRIDICT2.0 when loci with highly varying chromatin contexts are targeted. Therefore, we applied both models on a dataset where 41 loci with strong differences in chromatin marks were targeted by 146 pegRNAs in K562 cells (64 replacements, 42 insertions, 40 deletions). While PRIDICT2.0 alone only performed moderately on this dataset (R=0.41/r=0.44; Fig3n), prediction improved to R=0.66/r=0.59 when the model was combined with ePRIDICT (Fig3o,p), primarily due to more accurate predictions for loci with low accessibility (ExtFig6g,h). Similarly, when targeting 19 endogenous loci with varying chromatin contexts in HEK293T and HepG2 cells (with over 50 pegRNAs introducing replacements, insertions, deletions), ePRIDICT again elevated the performance of PRIDICT2.0 from R=0.44/r=0.46 to R=0.67/r=0.67 in HEK293T cells (ExtFig6i-k) and from R=0.39/r=0.37 (PRIDICT2.0 only) to R=0.5/r=0.43 (PRIDICT2.0 prediction with ePRIDICT) in HepG2 cells (ExtFig6l-n).

To summarize, we used target-matched library screening and TRIP19 to generate prime editing datasets, enabling us to examine the influence of pegRNA design and local chromatin context on prime editing rates. Our target-matched library featured a diverse and equally distributed array of edit types, including single- and multi-base replacements, as well as insertions and deletions of varying sizes. This diversity facilitated the development of PRIDICT2.0, a versatile model capable of accurately predicting edits up to 15 bp in length. The ability to predict multi-base replacements with high accuracy is also highly relevant for correcting point mutations, as the co-introduction of silent mutations frequently enhances editing rates, as assessed experimentally (Fig1j,k, and Chen et al.5) and in silico when pathogenic mutations were corrected individually or together with silent bystander mutations (Supplementary Figure 6). Since PRIDICT2.0 was trained on prime editing data generated in HEK293T and K562 cells, the model allows the prediction of pegRNA efficiency in MMR proficient- or deficient contexts. As a general guideline, we recommend users to employ the 'MMR-deficient' HEK293T PRIDICT2.0 model for cell lines known to be deficient in MMR, or when the PE45 approach with experimental MMR inhibition is applied. In contrast, the 'MMR-proficient' K562 PRIDICT2.0 model is recommended for cell lines with functional mismatch repair (MMR), which includes most cultured primary cells as well as cells in vivo in organisms. For users that want to apply PE312 or PE55 prime editing strategies, in which the non-edited strand is cut with an additional nicking guide RNA, we recommend first determining the most promising pegRNA with PRIDICT2.0 and then designing a compatible nicking guide RNA using Deep-SpCas929.

Previous reports suggested that not only the targeted sequence and pegRNA design, but also the chromatin status influences prime editing efficiencies30,31. Adapting TRIP14,18 in K562 cells for prime editing allowed us to systematically link chromatin characteristics with editing rates, leading to the generation of ePRIDICT, a computational model that provides a quantitative value for the editability of any specified locus. ePRIDICT is readily available for K562 cells but can also be applied to other cell lines in case chromatin features are available and conserved to K562 cells at the targeted locus. For designing prime editing experiments, we advise researchers to first identify the most efficient pegRNAs using PRIDICT2.0, and then employ ePRIDICT to evaluate the impact of the local chromatin context on the editing efficiency. This approach can be particularly useful for prime editing screening to target endogenous loci in a high-throughput manner, as recently shown by Cirincione and Simpson et al32. Of note, analysis of our TRIP data revealed that prime editing is generally more efficient in areas marked by chromatin features linked to promoter regions and actively transcribed genes, and less effective in areas related to suppressed chromatin and heterochromatin, similar to what has been observed for SpCas9 genome editing14,18. These insights could provide a reference for researchers aiming to apply prime editing in cell types for which chromatin features are not available.

In conclusion, we identified pegRNA and chromatin features that determine prime editing efficiency, and developed machine-learning models to guide researchers in designing their prime editing experiments. PRIDICT2.0 and ePRIDICT are both available via GitHub33,34 or at www.pridict.it.

Methods

Clonings

The TRIP plasmid library (pPTK-BC-IPR) utilized in the chromatin-context investigation has been described in Schep et al. 202114. Library-Diverse cloning was performed according to the protocol described by Mathis et al. 20231. For the validation of ePRIDICT on endogenous targets, pegRNAs were designed as follows. We selected 20 genomic locations from the TRIP screen results, where 10 exhibited high editing efficiency for prime editing, ABE8e, and BE4max, and the remaining 10 showed low editing efficiency. For each location, a 200 bp window both upstream and downstream was scanned to identify pegRNAs capable of introducing a 1 bp replacement edit, a 4 bp insertion edit, and a 4 bp deletion edit. The pegRNAs with the highest scores based on PRIDICT1 were selected. Additionally, protospacers that contained at least one "A" for ABE8e and "C" for BE4max within their respective editing windows were identified. The highest-scoring spacer based on BEHive36 was selected to ensure the chosen gRNAs were highly predicted, minimizing the influence of sequence context on editing outcomes. Independently from these 20 previously described genomic locations, we designed 90 additional pegRNAs (21 deletions, 24 insertions, and 45 1bp replacements) targeting intronic and intergenic regions of 17 different genomic loci. All pegRNAs were cloned using established methods1, but with the pU6-tevopreq1-GG-acceptor35 vector. sgRNAs were incorporated into the lentiGuide-Puro37 (Addgene no. 52963) plasmid at BsmBI sites through one-pot cloning. Specifically, 5 μM of each spacer oligonucleotide were mixed in 1x Buffer 3.1, supplemented with 0.3 μl of BsmBI enzyme, 0.5 μl of T4 DNA ligase, 500 μM ATP, and 50 ng of the lentiGuide-Puro vector. This 20 μl reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour before transformation. pegRNA and sgRNA plasmids were transformed into NEB Stable Competent E. coli. Resulting colonies were cultivated in LB (with 100 µg/ml carbenicillin) overnight. Plasmids were then extracted using the GeneJET Plasmid Mini-prep Kit (Thermo Fisher) and verified via Sanger sequencing. The following plasmids were used for in vivo library integration. AAV-library-diverse: AAV compatible backbone which encloses I) RORI and LILO fragments that are recognized by SB100x transposase, II) our library under the hU6 promoter, and III) a p3-eGFP expression cassette. AAV-SB: SB100x was PCR amplified from pCMV(CAT)T7-SB100 (Addgene no. 3487938) and cloned inside AAV compatible backbone together with a p3 promoter by Gibson assembly.

Viral vector production

Lentiviral production was performed as previously described1. To generate Pseudotyped AAV9 vectors (AAV2/9), packaging, capsid, and helper plasmids (Addgene no. 112865 and no. 112867, a gift from James M. Wilson) were co-transfected in HEK293T cells and incubated for six days until harvest. The vectors were then precipitated using PEG and NaCl and subjected to gradient centrifugation with OptiPrep (Sigma-Aldrich) for further purification. Subsequently, the concentrated vectors were obtained using Vivaspin® 20 centrifugal concentrators (VWR). Physical titers (vector genomes per milliliter, vg/mL) were determined using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). AAV2/9 viruses were stored at -80 °C until they were used. AdV5-PE2ΔRnH (Human adenoviral vector 5 containing unsplit PE2ΔRnH) was produced by ViraQuest9.

Oligo Library Design for Library-Diverse

Library-Diverse was built from two separate parts. First, 2,000 pathogenic ClinVar variants (1bp SNPs) were selected, and pegRNAs were designed to correct the sequence to wild-type (1). Next, a non-coding bystander mutation was determined for each variant, and two additional pegRNAs were designed, one with the correction edit and the bystander edit (2) and one with the bystander edit only (3). 942 pegRNAs were designed to have identical spacer sequences for all three pegRNAs (1-3) per target, while pegRNAs of the other targets had 2 or 3 different spacers (but identical correction edit). For this library, PBS length was kept constant at 13 bp and RTT overhang length at 10 bp.

For more flexibility in designing pegRNAs while preventing editing on endogenous sequences in the human genome, the second part of the library was designed based on the Emu (bird) genome. pegRNAs for 7,938 random deletions (1-15 bp), 7,941 random insertions (1-15 bp), 3,956 random multi-base changes (continuous 2-5 bp changes), and 3,968 random 1 bp changes were designed. PBS length was kept constant at 13 bp while RTT overhang varied (3, 7, 10, or 15 bp).

In total, the Library-Diverse was finally made up of 29,804 pegRNA-target combinations. The library was ordered from Twist Bioscience. Library oligos are listed in Supplementary Table 2, and amplification primers (cloning and NGS PCRs) are listed in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

Cell culture

HEK293T (ATCC CRL-3216) and HepG2 (ATCC HB-8065) were maintained in DMEM++ (DMEM plus GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific)) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for splitting HEK293T cells. Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for splitting HepG2 cells after washing them with PBS. K562 cells (ATCC CCL-243) were maintained in RPMI++ (RPMI 1640 Medium with GlutaMAX Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific)) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were maintained at confluency below 90% and were tested negative for Mycoplasma contamination.

Library-Diverse screen setups

HEK293T

HEK293T screening with Library-Diverse was performed as previously described (see "Library 1" in Mathis et al. 1). In short, we first produced lentivirus containing the library, then transduced HEK293T cells at an MOI < 0.3 and finally selected cells with 2.5 µg/µl puromycin for 7 days. After selection, cells were frozen and then thawed independently for each replicate. After thawing, cells were expanded and transfected (day 0) with PEI at a coverage of > 500x with pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR (Addgene no. 192508). One day later, cells were selected and maintained for 6 days with 750 ng/µl Zeocin (Invivogen) until harvest on day 7.

K562 and K562-MLH1dn

K562 cell library with Library-Diverse was created as previously described1. In short, we first produced lentivirus containing the library, then transduced K562 cells at an MOI < 1, and finally selected cells with 2.5 µg/µl puromycin for 10 days. After selection, cells were frozen and then thawed independently for each replicate. pCMV-PE2-BleoR plasmid was electroporated (1450 V, 10 ms, 3 pulses) in the cell pool using a Neon Transfection System (100 µl kit). For each replicate, a total of 150 million K562 cells were transfected, with 3 million K562 cells and the following amount of plasmids per individual electroporation (Day 0):

K562 setting: 10 µg of pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR (Addgene no. 192508)

K562-MLH1dn setting: 7.77 µg of pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR1 (Addgene no. 192508) together with 2.23 µg of pEF1a-hMLH1dn5 (Addgene no. 174824)

Controls were electroporated without DNA. One day after electroporation (Day 1), the medium was replaced with RPMI++ with 200 ng/µl Zeocin. Selection was continued until collection day (Day 7).

In vivo mouse liver screening with Library-Diverse is described below in the “Animal studies” section.

Animal studies

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the ‘Veterinäramt Kanton Zürich’ and in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations. C57BL/6J mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility at the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology of the University of Zurich. Mice were kept in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room (21 °C, 50% RH) on a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Newborn animals (P1, three mice, female) were injected with AAV-library-diverse (8 × 1010 vg), AAV-SB (8 × 1010 vg), and 2.4 × 1010 viral particles of human adenoviral vector 5 containing PE2ΔRnH (ViraQuest)9 via the temporal vein. Control animals (P1, two mice, female) received the AAV-library-diverse and AAV-SB with the same vector dose but without AdV5-PE2ΔRnH. Mice were euthanized 6 weeks after injection. Primary hepatocyte isolation was performed as previously described by Böck et al.9.

TRIP library screens

K562-TRIP cell library was generated with K562 cells (ATCC CCL-243), the piggyBac transposase (mPB-L3-ERT2.TatRRR-mCherry19), and a piggyBac plasmid library containing target sequence and barcode (pPTK-BC-IPR14). Subsequent electroporations with gene editors were performed using a Neon Transfection System (100 µl kit) with 7.5 µg of editor plasmid and 2.5 µg guide plasmid per electroporation (Day 0; 3 million cells per electroporation; 1450 V, pulse width 10 ms, 3 pulses). pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR (Addgene no. 1925081) was used for prime editing, p2T-CMV-BE4max-BlastR (Addgene no. 15299136) was used for cytosine base editing, pCMV-ABE8e-SpG-P2A-GFP (in-house cloned from Addgene no. 13848939 and 14000240) was used for adenine base editing and pCMV-T7-SpCas9-P2A-EGFP (Addgene no. 13998740) for Cas9 editing. Guide sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. One day after electroporation (Day 1), the medium was replaced with RPMI++ with either 200 ng/µl Zeocin (PE) or 2.5 ng/µl puromycin (BE4max, ABE8e, Cas9). Cas9 cells were harvested the next day (Day 2), while PE, BE4max, and ABE8e cells were further selected until harvest on Day 7.

Endogenous reporter validations

A reporter containing the genomic sequences of 10 highly scoring and 10 low scoring locations (see Cloning methods section) from the TRIP libraries was designed and ordered as 3 separate gene blocks from IDT (Supplementary Table 6). One high-scoring locus (chr10, position 17655923; hg38) was excluded from further analysis due to a sequence polymorphism in K562 cells to allow a consistent comparison between cell lines. Gibson assembly was performed to clone the reporter into a piggyBac-PuroR backbone. Next, HEK293T, K562, and HepG2 cells were transfected. 130,000 HEK293T, 100,000 K562, or 100,000 HepG2 cells were seeded into 48-well plate, 6h before transfection and then transfected with 225 ng of reporter plasmid and 25 ng of piggyBac helper plasmid and 1 µl Lipofectamine 2000. Three days after transfection, the medium was replaced with DMEM++ and 2.5 ng/µl puromycin (HEK293T and HepG2) or RPMI++ and 2.5 ng/µl puromycin (K562). Cells were selected for 10 more days to ensure the integration of the reporter construct.

HEK293T-reporter cells were then edited as follows. 130,000 cells were seeded per well in 48-well plate 6h before transfection (Day 0). Next, transfection was performed with 1 µl of Lipofectamine 2000 with:

PE: 750 ng of editor (pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR) and 250 ng of pegRNA

ABE8e, BE4max, Cas9: 500 ng of editor, 250 ng of sgRNA, 200 ng of pCMV-Tol2 (Addgene no. 31823) and 50 ng CMV-GFP. (ABE8e: p2T-CMV-ABE8e-SpCas9-BlastR, BE4max: p2T-CMV-BE4max-BlastR (Addgene no. 152991), Cas9: p2T-CMV-SpCas9-WT-BlastR)

On the next day (Day 1), HEK293T cells were split 1:2 into new 48-well plates, and the medium was replaced with DMEM++ and 750 ng/µl Zeocin (PE) or 20 ng/µl Blasticidin (ABE8e, BE4max and Cas9). Cas9 transfected cells were harvested one day later (Day 2). PE, ABE8e, and BE4max transfected cells were maintained under selection until harvest on Day 7. K562-reporter cells were handled similarly but with the following differences. 100,000 cells were seeded per well, and selection was performed with RPMI++ and 200 ng/µl Zeocin (PE) or 20 ng/µl Blasticidin (ABE8e, BE4max and Cas9). Editing with the 90 pegRNAs targeting 17 loci (intronic and intergenic) was performed as described above but in wild-type K562 cells.

HepG2-reporter cells were edited as follows. 80,000 cells were seeded per well in 48-well plate 24h before transfection (Day -1). On the next day (Day 0), transfection was performed with 1.5 µl of HepG2 reagent (GenJet) with 750 ng of prime editor (pCMV-PE2-tagRFP-BleoR) and 250 ng of pegRNA per well. One day later (Day 1), HepG2 cells were split 1:3 into new 48-well plates, and the medium was replaced with DMEM++ and 300 ng/µl Zeocin. HepG2 cells were maintained under selection until harvest on Day 7.

K562 and HEK293T experiments were performed on 2 different days with 1-2 replicates from the same day. Replicates from the same day were treated as technical replicates, and after sequencing, editing efficiencies of technical replicates were combined into one biological replicate. Experiments with HepG2 were performed on the same day with 3 replicates per pegRNA.

Guide sequences and editing results are listed in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8.

Genomic DNA isolation and HTS

Genomic DNA from Library-Diverse was isolated by Blood & Cell Culture DNA Maxi Kit (Qiagen; 30 million cells per condition). Genomic DNA from the TRIP library editing experiments was isolated by DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (4 million cells per condition). DNA from endogenous editing experiments was isolated by direct lysis using direct lysis buffer: 10 µl of 4× lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 2% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1% freshly added proteinase K) was added to cells resuspended in 30 µl of PBS and incubated at 60 °C for 60 min and 95 °C for 10 min. Genomic DNA for the TRIP tagmentation experiment was isolated by direct lysis followed by Phenol-Chloroform DNA purification and ethanol precipitation.

Target sites of library-diverse were amplified by NEBNext Ultra II Q5 Master Mix (NEB, 26 cycles; primers see Supplementary Table 3), and target sites from the TRIP library were amplified by GoTaq G2 Hot Start Green Master Mix (Promega, 26 cycles; primers see Supplementary Table 5). Amplicons were purified via gel extraction using a NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Mini kit (Macherey-Nagel). Illumina sequencing adapters were added with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB; seven cycles; primers see Supplementary Table 4) and purified by gel extraction. TRIP tagmentation library was prepared as described in the "Library analysis TRIP" methods section.

Endogenous target sites and reporter target sites for arrayed editing were amplified by GoTaq G2 Hot Start Green Master Mix (Promega, 30 cycles; primers see Supplementary Table 6) and were purified with Sera-Mag Select (Merck). Illumina sequencing adapters were added with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB; seven cycles; primers see Supplementary Table 4) and purified by gel extraction.

Final pools were quantified on a Qubit v.3.0 (Invitrogen). The average amplicon size of the TRIP tagmentation library was quantified on a TapeStation 4200 (Agilent). Library-Diverse and TRIP editing and tagmentation libraries were sequenced paired-end on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 using SP Reagent Kits (2×250 cycles for Library-Diverse, 2x 150 cycles for TRIP libraries; demultiplexing with Illumina NovaSeq Control software v1.7). Arrayed targets (endogenous and reporter) were sequenced paired-end (2 × 150) on an Illumina MiSeq using MiSeq Reagent Micro Kit v2 (demultiplexed with MiSeq Control software v3.1 and v4.0).

Library analysis of Library-Diverse

Editing levels were determined by initial trimming of sequencing reads with Cutadapt v. 3.141, followed by inhouse scripts. Each sequencing read was assigned to the corresponding target sequence based on the spacer sequence, extension sequence, tevopreQ1 motif35, and a barcode. Only reads with matches for all elements were used for the final analysis (filtering out ∼34% in HEK293T and K562 cells and ∼60% of sequencing reads for the library in mouse hepatocytes). To calculate the editing rate, we compared the read sequence (2 bp upstream of nick position until 5 bp downstream of edited flap end) with wild-type and edited sequence and assigned the labels 'unedited', 'edited', or 'nonmatch'. Editing efficiency was calculated as previously described1 with the formula:

Background intended edit frequencies were determined by analyzing the control library pool, which was not transfected with the prime editor. Target sequences were further filtered for having a minimum of 100 reads in every replicate (minimum of 50 reads for in vivo screen). Target sequences where the corresponding control had >20% unintended editing rate or >5% intended editing were also discarded. After averaging editing values from the different replicates, the values were clamped to be within 0 and 100%. This led to a total of 22,619 (HEK293T), 22,752 K562 (without MLH1dn), 20,477 (K562 with MLH1dn), and 17,775 sequences (in vivo mouse hepatocytes) that were used for further analysis. For each pegRNA in the HEK293T and K562 dataset, a selection of features was extracted to train statistical machine learning models and to complement deep learning models. These features included RTT-, PBS- and Correction-length, GC content, melting temperature, the maximum length of polyA/T/G/C sequence stretches, DeepSpCas9 score29, and minimum free energy (ViennaRNA Package v.2.042). A full overview of features used in training statistical and deep learning models is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Library analysis TRIP

The tagmentation reaction was executed using the following protocol. To ensure high tagmentation coverage of the TRIP pool, 15 parallel reactions were conducted. Primers adapt_A & adapt_A_invT were annealed in a controlled ramp-down cycle ranging from 95 °C to 4 °C. The transposome complex was assembled by mixing 1 μl of 1:2 diluted adapters with 1.5 μl of Tn5 transposon in 18.7 μl of Tn5 dilution buffer (20 mM HEPES, 500 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol) and incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C. Tagmentation was performed by combining 100 ng of genomic DNA with 1 μl of the pre-assembled transposome and 2x TD buffer pH 7.6 in a 20 μl final volume. The reaction mixture was incubated at 55 °C for 10 minutes and subsequently quenched with 0.2% SDS. Three distinct libraries ("For," "ForBC," and "Rev") were generated using linear PCR with For, ForBC, and Rev enrichment primers. The initial target enrichment involved 45 amplification cycles, using a mix that included tagmented DNA, primers, dNTPs, 5× Phusion HF Buffer, and Phusion HS Flex polymerase in a 20 µl final volume. For library preparation (PCR 1), 11 amplification cycles were conducted using Phusion HS Flex polymerase in a 25 µl final volume. N7xx adapters were introduced in PCR 2, consisting of 10 cycles of amplification using Phusion polymerase in a 22 µl final volume. Post-amplification, 5 µl of each reaction was assessed on a 1% agarose gel. The 15 parallel samples from the TRIP pool were combined. Libraries were bead-purified using CleanPCR beads at a 1:0.8 sample-to-bead ratio. Sequencing was done on a NovaSeq 6000 with 150 bp paired-end reads.

For sequencing analysis, the amplicons were trimmed by Cutadapt v. 3.141 and aligned to the human genome with bowtie2 v. 2.5.143 (hg38, mapq score >30). Only the ForBC mapping locations confirmed by both For and Rev amplicon mappings (with at least 10 mappings each), and those where locations of "For" and "Rev" locations were exactly 4bp from each other (TTAA integration motif of PiggyBac) were retained. Editing efficiencies of different editors and barcodes (= genomic insertions) were then analyzed by examining the target amplicon, which includes the target sequence and barcode. Following demultiplexing based on barcodes, editing efficiency for each barcode was computed using custom scripts. Control replicates were also evaluated, allowing for adjustments in the final editing rates to account for background editing/mutations.

For correlating editing rates with chromatin characteristics, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and DNase-seq were sourced from the ENCODE database20. All datasets are listed in Supplementary Tables 9-11. Average values for different sequence lengths at genomic locations in our dataset were then computed. We selected windows of 100, 1000, 2000, and 5000 bp both upstream and downstream of each location, and averaged chromatin values across these regions (as shown in Fig3f). UMAP projection26 was employed to visually represent the chromatin landscape of our integrated reporter locations. Finally, K-means clustering was used to segment the locations into four distinct groups for a more in-depth analysis. TRIP library editing results with genomic location and chromatin characteristics are listed in Supplementary Table 12.

Analysis of arrayed editing experiments

Arrayed experiments for validation on endogenous loci were analyzed using CRISPResso2 v. 2.2.1244 in batch mode. For prime editing samples, the original sequence (‘amplicon_seq’), the expected sequence after editing (‘expected_hdr_amplicon_seq’), and window of quantification (2 bp upstream of nick position until 5 bp downstream of edited flap end; ‘quantification_window_coordinates’) were used for batch analysis. For base editing and Cas9, the original sequence and guide sequence with default settings for base editing and a quantification window size of 3 for Cas9 were used. Editing efficiencies of 1-2 technical replicates (transfection in separate wells but on the same day) were averaged and used as one independent biological replicate for the following analysis. Control editing efficiencies were subtracted from each sample, and only samples with more than 500 reads were used in the analysis. Editing rates are listed in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8.

Machine learning of sequence- and chromatin-context-dependent editing efficiency

Machine learning models trained on Library-Diverse only (ExtFig2a-d) were developed based on 22,619 (HEK293T) and 22,752 (K562) pegRNAs. Training workflow for PRIDICT2.0 is depicted in a schematic illustration in Fig1n. Model A was built by base training with Library 1 (92,423 pegRNAs in HEK293T, from Mathis et al. 20231) and then fine-tuning on Library-Diverse (with both HEK293T and K562 editing efficiencies). Model B was built by base training on Library 1 and Library-ClinVar (288,793 pegRNAs in HEK293T, from Yu et al. 20234) and then fine-tuning on Library-Diverse. Finally, Model A and Model B were combined into an ensemble model, PRIDICT2.0, by combining prediction values of either HEK293T or K562 from both models in a 1:1 ratio. For all models, we followed a grouped fivefold cross-validation on Library-Diverse where pegRNAs for the same locus were kept in the same train- or test set. Each fold had 80% of the Library-Diverse pegRNAs for training and 20% for testing. A 10% grouped random split was taken from each fold's training sequences to create a validation set, which was then used for optimizing the model's hyperparameters. For the neural network model, we used a uniform random search strategy that randomly chose a set of hyperparameter configurations from the set of all possible configurations and trained45 corresponding models on a random fold. Subsequently, the best model hyperparameters were determined based on the performance of the models on the validation set of the respective fold. Finally, these hyperparameters were used for the final training and testing of each model on all five folds. For baseline models11,46 in ExtFig2a-d (XGBoost, Histogram-based Gradient Boosting, RandomForest Regressor, Lasso, ElasticNet, Ridge), we used a random search strategy over each model's specific hyperparameter space where the best hyperparameters were determined using twofold cross-validation on the combined training and validation set of each fold. Subsequently, the model achieving the best performance was retrained and tested (using the test set) on each corresponding fold of the five folds. We furthermore performed SHAP analysis10 to extract information about the importance of features on the XGBoost model (on a test fold; Fig1r,s).

For the chromatin context-based prediction of editing rates, we used the mapped editing efficiencies (1,182 for PE, 1,169 for ABE8e, 1,194 for BE4max, and 1,196 for Cas9) and ENCODE features from 455 datasets (ePRIDICT) or 6 datasets (ePRIDICT-light). We performed 5-fold cross-validation for PE prediction with linear regression-based models (Ridge, Lasso, ElasticNet) and tree-based models (HistGradientBoosting, RandomForest, XGBoost). Additionally, parameters for XGBoost ePRIDICT and ePRIDICT-light models were optimized via random search cross-validation (RandomSearchCV, Scikit-learn46). The same parameters were used for XGBoost models trained on ABE8e, BE4max, and Cas9 datasets. The performance of XGBoost models is shown by combining predictions from all individual folds and calculating correlations on the combined dataset. After benchmarking the model performances with cross-validation (Fig3k,l, and ExtFig5h), we retrained ePRIDICT and ePRIDICT-light on the full dataset (1,182 loci). For the predictions presented in Fig3m-p and ExtFig6, we trained an ePRIDICT model that excludes the loci featured in these figures from training to prevent training leakage.

Analysis of third-party datasets and models

Editing rates for Library-ClinVar were extracted from the supplementary material of Yu et al.4. We incorporated all 288,793 pegRNAs, spanning both the Training and Test set, into the training process of the PRIDICT2.0 model. Library-Small editing efficiencies (Fig2f, SuplFig5b,g) and endogenous efficiencies (Yu-1, Yu-2; Fig2h) were also extracted from the supplementary material of Yu et al4. The Python package GenET (0.12.0)47 was used to predict efficiencies with DeepPrime. Insertion efficiencies from Koeppel et al. were retrieved from GitHub48 (commit a70a049; files/input/screendata.csv). The same GitHub package48 was used to predict efficiencies with MinsePIE. To validate ePRIDICT, we utilized the dataset from Li et al.28, which includes 4144 integration locations and the corresponding prime editing efficiencies. Feature values were extracted from all averaging windows (100, 1000, 2000, and 5000 bp up and downstream) across 455 ENCODE datasets, following the same methodology applied to our TRIP library.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistics were performed using Python (v. 3.9.15 or 3.10.12) and SciPy (v.1.10.1, v.1.7.3, v.1.11.2). Machine learning models were developed with scikit-learn46 (1.0.1 for Library-Diverse, 1.0.2 for TRIP library), XGBoost (1.5.0 for Library-Diverse, 1.7.6 for TRIP library) and pytorch (1.9.0). For statistical machine learning models, TensorFlow49 (2.13.0) was used for DeepSpCas9 score29 predictions, and ViennaRNA Package v.2.042 was used for MFE calculations. Bowtie243 (2.5.1) was used for alignments during TRIP library mapping. pyBigWig50 (0.3.22) was used for processing bigwig files. UMAP-learn26 (0.5.3) was used for UMAP projections. Pearson (r) and Spearman (R) correlations were determined to evaluate the correlation of predicted and measured pegRNA editing rates. Editing experiments were performed at least in independent biological duplicates. Sample sizes, bars, box plots, and error bars are described in figure legends.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Library-Diverse characteristics.

(a) Edit type distribution in Library 1 from Mathis et al. 20231, which had a focus on 1bp replacements and short insertions and deletions. (b) Edit type distribution in 'Library-Diverse' screened in this study. (c) Self-targeting construct with the promoter (hU6) and different pegRNA domains (spacer, scaffold, reverse transcription template/RTT, primer binding sequence/PBS, tevopreQ1 motif35, and poly T stop signal), target sequence (including position of Protospacer), and primer location for NGS-PCR (forward (Fw) and reverse (Rv) primer). (d-g) Correlation of background-subtracted individual replicates of 'Library-Diverse' prime editing screens in (d) HEK293T (n = 22,619), (e) K562 (n = 22,752), (f) K562 cells with MMR inhibition through MLH1dn expression (n = 20,477), and (g) in vivo (mouse liver hepatocytes; n = 17,775). Color gradient from dark purple to yellow indicates increasing point density, per Gaussian KDE.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Machine learning metrics for training models on 'Library-Diverse'.

(a, b) Comparison of 7 different machine learning model performances on editing efficiency prediction in HEK293T (Spearman (a), Pearson (b)) and K562 (Spearman (c), Pearson (d)). Bars show the mean of fivefold cross-validation, and each of the five cross-validations is visualized as individual data points (n=5). Error bar indicates the mean +/- s.d. (e) Prediction Pearson correlations of PRIDICT1 and PRIDICT2.0, tested on different edit types and cell types. n for rows from top to bottom: 5,957, 4,455, 6,283, 5,924, 5,969, 4,508, 6,302, 5,973. (f) Prediction Pearson correlations of PRIDICT1 and PRIDICT2.0, tested on insertions and deletions of different lengths in HEK293T and K562 cells. n for different edit lengths combined are as follows: HEK293T insertions: 6,283, HEK293T deletions: 5,924, K562 insertions: 6,302, K562 deletions: 5,973. (g) Prediction Spearman correlations of PRIDICT1, the updated attention-based bi-directional RNN architecture trained on Library 11 only (see Fig1n), or on Library 11 and Library-ClinVar4, and PRIDICT2.0 (includes fine-tuning on Library-Diverse); tested on different edit and cell types. n for rows from top to bottom: 22,619, 5,957, 4,455, 6,283, 5,924, 22,752, 5,969, 4,508, 6,302, 5,973.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Editing characteristics in K562 with MMR inhibition (MLH1dn) and in vivo (mouse liver).

(a-f) Editing efficiencies of different edit/pegRNA features in K562 with MMR inhibition (MLH1dn5). (g-l) Editing efficiencies of different edit/pegRNA features in the in vivo (mouse liver) setting. Editing efficiency for different edit lengths of (a,g) insertions and (b,h) deletions. (c,i) Heatmap visualizing editing efficiency of pegRNAs (1bp replacements) in Library-Diverse with different RTT overhang lengths (3, 7, 10, 15 bp) and edit positions (1–15). PAM position is highlighted with black dotted rectangle. (d,j) Editing efficiency of replacements with edit lengths of 1 to 5 bp. (e,k) Editing efficiency of single and double 1 bp replacements with or without editing of at least 1 base within the GG PAM sequence. (f,l) Editing efficiencies for double edits where 2 separated 1 bp replacements were installed. Intended editing means that both replacements were installed, whereas intermediate editing means that only 1 of the 2 replacements was installed. Distance of 0 corresponds to single 1 bp edits. (a-l) Bars show mean with error bar indicating mean +/- s.e.m. The numbers of analyzed pegRNA-target combinations are as follows. a, n = 371, 492, 504, 409, 412, 382, 406, 405, 405, 397, 323, 340, 333, 295, 320. b, n = 384, 444, 365, 345, 370, 385, 347, 379, 379, 369, 354, 339, 318, 314, 320. c, n = 2,815. d, n = 4,520, 764, 588, 497, 526. e, n = 4,092, 428, 2,528, 761. f, n = 4,520, 764, 130, 65, 151, 117, 25, 119, 133, 25, 149. g, n = 315, 415, 439, 351, 338, 321, 339, 356, 340, 337, 277, 303, 286, 243, 277. h, n = 317, 367, 294, 275, 288, 308, 289, 324, 304, 302, 273, 285, 255, 259, 249. i, n = 2,362. j, n = 4,265, 653, 499, 408, 459. k, n = 3,889, 376, 2,289, 663. l, n = 4,265, 653, 134, 59, 155, 119, 24, 119, 138, 26, 159.

Extended Data Fig. 4. TRIP screen characteristics for different edit modalities.

(a-d) Distribution of editing efficiency across different TRIP reporter integrations for (a) PE, (b) ABE8e, (c) BE4max, and (d) SpCas9 genome editing. Dotted vertical line indicates mean editing efficiency. (e-h) Correlation (Pearson) of individual TRIP screening replicates for PE (n = 1,182) (e), ABE8e (n = 1,169) (f), BE4max (n = 1,194) (g), and SpCas9 (n = 1,196) (h) genome editing. (i,j) Correlation of replicate means between different edit modalities: Spearman (i), Pearson (j). Only barcode integrations available from all editors are used for analysis (n = 1,165).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Additional analysis of TRIP screens and predictive modeling of editing rates.

(a-c) UMAP projection based on chromatin characteristics of genomic locations in the TRIP library (n=1,165; corresponding to integrations with mappings to all editors), with editing efficiency overlay of (a) ABE8e, (b) BE4max, and (c) Cas9. (d-g) Visualization of chromatin characteristics of clusters defined in Fig3i. For each target/dataset type, we selected the averaging window with the largest deviation from the library mean. The relative difference to the library mean, calculated as the absolute difference between the cluster average and the library mean divided by the library mean is shown. (h) Evaluation of the ePRIDICT-light XGBoost model trained on a subset of 6 features. Predictions from 5 different cross-validation runs were combined. (n=1,182). (i) Spearman and Pearson correlation of XGBoost model prediction to editing efficiencies in TRIP library for prime editing, adenine base editing (ABE8e), cytosine base editing (BE4max), and SpCas9 genome editing. Bars show the mean of fivefold cross-validation, and each of the five cross-validations is visualized as individual data points (n=5). Error bar indicates the mean +/- s.d. (j) Validation of ePRIDICT on an independent dataset from Li et al.28, where one sequence was integrated and edited (CTT insertion) at 4,144 genomic locations. (h,j) Color gradient from dark purple to yellow indicates increasing point density, per Gaussian KDE.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Validation of ePRIDICT at endogenous loci in K562, HEK293T and HepG2 cells.

(a) Spearman correlation analysis of ENCODE feature values for 19 selected endogenous loci, comparing datasets from K562 and HEK293T cells. (b) Validation of prime editing efficiency in HEK293T cells on endogenous loci with high (>50) or low (<35) ePRIDICT scores, normalized to editing on the reporter sequence. 1bp replacements (n-high: 9, n-low: 10), 4bp insertions (n-high: 9, n-low: 9), and 4bp deletions (n-high: 9, n-low: 10). (c-d) Validation of genome editing efficiency on endogenous loci normalized to editing on integrated reporter in K562 (c) and HEK293T (d) with high (>50, n = 8 (K562) and 9 (HEK293T)) and low (<35 n = 9 (K562) and 10 (HEK293T)) ePRIDICT values for ABE8e, BE4max, and Cas9. (e) Spearman correlation analysis of ENCODE feature values for 19 selected endogenous loci, comparing datasets from K562 and HepG2 cells. (f) Validation in HepG2 cells as described in b. 1bp replacements (n-high: 9, n-low: 10), 4bp insertions (n-high: 8, n-low: 8), and 4bp deletions (n-high: 9, n-low: 10). (g, h) Binning editing efficiency and predicted score from Fig3n,o into 3 categories each. Editing efficiency is binned into “Low” (n=92), “Middle” (n=27), and “High” (n=27) categories based on the cutoffs <5%, 5-20%, and >20%. The prediction score is binned in three even-sized tertiles. (g) PRIDICT2.0 K562 value as prediction score. (h) Combined PRIDICT2.0 K562 and ePRIDICT value (average of both scores) as prediction score. (i,j) Performance of PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T (i) or PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T in combination with ePRIDICT (j) in predicting the editing efficiency of 56 pegRNAs targeting endogenous loci in HEK293T. (k) Additional visualization of the performance of PRIDICT2.0 HEK293T alone or in combination with ePRIDICT on 56 pegRNAs targeting endogenous loci in HEK293T, including highly and poorly accessible loci. (l-n) Performance of PRIDICT2.0 K562 or PRIDICT2.0 K562 in combination with ePRIDICT in HepG2 (54 pegRNAs), as described for i-k. (b-d, f) Boxplots represent the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers extend to points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the quartiles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Functional Genomics Center Zurich for their support in next-generation sequencing; the Science IT team at the University of Zurich for the computational infrastructure used for data analysis; the ENCODE consortium for providing the datasets used for the analysis of TRIP libraries; C. Leemans for consulting during the TRIP library analysis; G. Affentranger for assistance in figure design; and the members of the Schwank laboratory for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) grant numbers 185293, 214936, and 201184, URPPs (University Research Priority Programs) 'Human Reproduction Reloaded' and 'ITINERARE', the SERI financed ERC Consolidator Grant 'GeneREPAIR', an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (S.J.), and the Promedica Stiftung.

Footnotes

Author contributions

N.M. designed the study, performed experiments, and analyzed data. A.A. designed and generated attention-based bidirectional RNNs. Linear regression and tree-based machine learning models for Library-Diverse were built by A.A., and models for TRIP predictions were built by N.M.. E.B. and S.J. were involved in TRIP library screening. A.T. and T.D. performed editing experiments on endogenous loci. L.K. performed in vivo experiments with help from E.I.I.. R.S. and B.v.S. provided the TRIP plasmid library and performed tagmentation experiments of the cell pool. Z.B. contributed to the integration analysis of the TRIP library. L.S. and D.B. helped in NGS and cloning experiments. N.M. and G.S. wrote the manuscript with input from A.A. and R.S.. M.K. and G.S. designed and supervised the research. All authors revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

G.S. is a scientific advisor to Prime Medicine. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Measured editing rates used for analysis and creating figures in this study are provided in Supplementary Tables 2, 7, 8, and 12. DNA-sequencing data is available via the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA1025026)51. ENCODE datasets for K562, HEK293, and HepG2 are listed in Supplementary Tables 9-11 and are available from encodeproject.org.

Code availability

Scripts used in this study for data analysis or offline running of the prediction models (PRIDICT2.0, ePRIDICT) are provided on GitHub33,34. Online implementation of both models can be accessed via www.pridict.it. Additional information on the PRIDICT2.0 algorithm can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.

References

- 1.Mathis N, et al. Predicting prime editing efficiency and product purity by deep learning. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41:1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01613-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HK, et al. Predicting the efficiency of prime editing guide RNAs in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:198–206. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0677-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koeppel J, et al. Prediction of prime editing insertion efficiencies using sequence features and DNA repair determinants. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;2023:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01678-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu G, et al. Prediction of efficiencies for diverse prime editing systems in multiple cell types. Cell. 2023;186:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen PJ, et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell. 2021;184:5635–5652.:e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira da Silva J, et al. Prime editing efficiency and fidelity are enhanced in the absence of mismatch repair. Nat Commun. 2022;13:760. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trojan J, et al. Functional analysis of hMLH1 variants and HNPCC-related mutations using a human expression system. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:211–219. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matheson EC, Hall AG. Assessment of mismatch repair function in leukaemic cell lines and blasts from children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:31–38. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Böck D, et al. In vivo prime editing of a metabolic liver disease in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abl9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundberg SM, Lee SI. In: von Luxburg U, Guyon I, Bengio S, Wallach H, Fergus R, editors. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions; Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017. pp. 4766–4775. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost; Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; August 13; New York, NY, USA. 2016. pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anzalone AV, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. 2019;576:149–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks DL, et al. Efficient in vivo prime editing corrects the most frequent phenylketonuria variant, associated with high unmet medical need. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110:2003–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schep R, et al. Impact of chromatin context on Cas9-induced DNA double-strand break repair pathway balance. Mol Cell. 2021;81:2216–2230.:e10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen E, et al. Decorating chromatin for enhanced genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119:e2204259119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2204259119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daer RM, Cutts JP, Brafman DA, Haynes KA. The Impact of Chromatin Dynamics on Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Human Cells. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:428–438. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding X, et al. Improving CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Efficiency by Fusion with Chromatin-Modulating Peptides. CRISPR J. 2019;2:51–63. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2018.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pokusaeva VO, Diez AR, Espinar L, Pérez AT, Filion GJ. Strand asymmetry influences mismatch resolution during single-strand annealing. Genome Biol. 2022;23:93. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02665-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akhtar W, et al. Using TRIP for genome-wide position effect analysis in cultured cells. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(6):1255–1281. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.072. 2014 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, et al. New developments on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D882–D889. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buenrostro J, Wu B, Chang H, Greenleaf W. ATAC-seq: A Method for Assaying Chromatin Accessibility Genome-Wide. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015;109:21.29.1–21.29.9. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2129s109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide Mapping of HATs and HDACs Reveals Distinct Functions in Active and Inactive Genes. Cell. 2009;138:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heintzman ND, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonasio R, Tu S, Reinberg D. Molecular Signals of Epigenetic States. Science. 2010;330:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1191078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters AHFM, et al. Partitioning and Plasticity of Repressive Histone Methylation States in Mammalian Chromatin. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1577–1589. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInnes L, Healy J, Melville J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. 2020 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1802.03426. Preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannister AJ, et al. Spatial Distribution of Di- and Tri-methyl Lysine 36 of Histone H3 at Active Genes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17732–17736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, et al. Chromatin context-dependent regulation and epigenetic manipulation of prime editing. 2023:2023.04.12.536587. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.020. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HK, et al. SpCas9 activity prediction by DeepSpCas9, a deep learning–based model with high generalization performance. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaax9249. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S-J, et al. Targeted mutagenesis in mouse cells and embryos using an enhanced prime editor. Genome Biol. 2021;22:170. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02389-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu N, et al. HDAC inhibitors improve CRISPR/Cas9 mediated prime editing and base editing. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids. 2022;29:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2022.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cirincione A, et al. A benchmarked, high-efficiency prime editing platform for multiplexed dropout screening. 2024:2024.03.25.585978. doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02502-4. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathis N, Allam A. GitHub Code Repository for PRIDICT20. 2024. https://github.com/uzh-dqbm-cmi/PRIDICT2 .

- 34.Mathis N. GitHub Code Repository for ePRIDICT. 2024. https://github.com/Schwank-Lab/epridict .

- 35.Nelson JW, et al. Engineered pegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:402–410. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]