Abstract

Several genetic disorders are associated with either a permanent deficit or a delay in central nervous system myelination. We investigated 24 unrelated families (25 individuals) with deficient myelination after clinical and radiological evaluation. A combinatorial approach of targeting and/or genomic testing was employed. Molecular diagnosis was achieved in 22 out of 24 families (92%). Four families (4/9, 44%) were diagnosed with targeted testing and 18 families (18/23, 78%) were diagnosed using broad genomic testing. Overall, 14 monogenic disorders were identified. Twenty disease-causing variants were identified in 14 genes including PLP1, GJC2, POLR1C, TUBB4A, UFM1, NKX6-2, DEGS1, RNASEH2C, HEXA, ATP7A, SETBP1, GRIN2B, OCLN, and ZBTB18. Among these, nine (45%) variants are novel. Fourteen families (82%, 14/17) were diagnosed using proband-only exome sequencing (ES) complemented with deep phenotyping, thus highlighting the utility of singleton ES as a valuable diagnostic tool for identifying these disorders in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: deficient myelination, genomics, myelin, neuroimaging

1. Introduction

Myelin is an extended and modified plasma membrane of oligodendrocytes, which forms a concentric lamellar structure around the axons of neurons (Czopka, Ffrench-Constant, and Lyons 2013; Geren and Raskind 1953). The formation of myelin sheath enables faster and more efficient propagation of signals through saltatory nerve conduction and also fulfills metabolic demands of the neurons (Philips and Rothstein 2017; Ritchie 1982). The process of central nervous system (CNS) myelination starts at the fifth fetal month and is usually completed by the age of 2 years (Branson 2013). Due to the crucial neurophysiological role of myelination, defects in this process result in varied degrees of neurological dysfunction (Bae et al. 2020).

Disorders of CNS with either permanent hypomyelination or delayed myelination are genetically and phenotypically diverse (Malik et al. 2020). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pattern recognition is a valuable tool for diagnosis of these disorders. Myelin deficit in CNS manifests as cerebral hyperintensities in T2-weighted images and iso-, hypo- or mild hyper-intensities in T1-weighted images in MRI (Schiffmann and van der Knaap 2009; Steenweg et al. 2010; Barkovich and Deon 2016). A combination of radiological and characteristic clinical findings makes several of these disorders clinically identifiable (Shukla et al. 2021).

The advent of genomic testing has significantly increased the diagnostic yield for these disorders up to 80%–90% (Ji et al. 2018). However, the spectrum of these disorders in several understudied populations and optimal testing strategies in resource-limited settings remain largely unknown. Herein, we delineate the genetic and phenotypic landscape of 24 families with deficient myelination in the Indian population and describe a sequential genetic testing approach to unveil the underlying genetic etiology of these disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Subject Recruitment

A total of 24 families (25 individuals with deficient myelination) were recruited from November 2019 to January 2024 (Table S1). Inclusion criteria included patients of any age with clinical manifestations and neuroimaging findings of deficient myelination. Written informed consent was obtained from the families. Approval of the institutional ethics committee at Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, India, as per the declaration of Helsinki was taken.

2.2. Genetic Testing

Families with a clinical diagnosis and those suspected of having disorders with known recurrent variants underwent targeted genetic testing, provided the targeted testing was available in-house. Targeted genetic testing consisted of Sanger sequencing of exonic and flanking intronic regions of disease-associated genes and/or probable founder variants, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (SALSA MLPA KIT P071; MRC Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands), and Gap-PCR. Gap-PCR for common 30 kb deletion in GALC was performed using GoTaq (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) with primers: forward primer—CCTATATGGAAAACAATGTGG, reverse primer 1—AAGGAGCAACATTTCAGGC, and reverse primer 2 for 30 kb deletion—TCAAGTCCTTGATGATCACC. Families with genetically heterogeneous disorders, undiagnosed disorders, or with a negative result on targeted genetic testing underwent broad spectrum genomic testing. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and Mendeliome were performed using Illumina NextSeq Platform (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). In-house pipeline based on bwa-mem2 (v2.1) (Md et al. 2019) and GATK (Genome Analysis Tool kit) best practices (v4.0) (Poplin et al. 2017) was used to detect the variants. Annotation was used by ANNOVAR and our in-house scripts (K. Wang, Li, and Hakonarson 2010). Allele frequencies, homozygous, and heterozygous counts were generated using gnomAD v.3, Genome Asia, and Singapore 10k pilot project (Chan et al. 2022). Customized scripts were used to generate allele frequencies from in-house WES data. The allele frequencies and counts were integrated while annotating sample VCF files. Further, gnomAD allele frequencies (< 1% considered for rare variants) were utilized while filtering genomic variants. In-house allele frequency of < 0.01% for heterozygous variants and homozygous count of less than 10 individuals was used. Since we have phenotype information for all individuals in our in-house data, we utilize this information along with predicted in silico scores to filter and prioritize genomic variants for analysis. Sanger sequencing was performed to segregate and validate the identified variants in all the families.

Copy number variation (CNV) annotation was performed by eXome-Hidden Markov Model, ExomeDepth, and cn.mops pipelines (Fromer et al. 2012; Klambauer et al. 2012; Plagnol et al. 2012). Chromosomal microarray (CMA) was performed using the Illumina's Infinium Global Screening 650 K array (San Diego, California) and 750 K array (Santa Clara, California). Analysis of 650 K array CMA data was carried out using the KaryoStudio v1.4 and of the 750 K array data using the Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) v4.2 software. Individuals with no clinically relevant single-nucleotide variants after WES data analysis underwent CNV analysis. Further, CNVs were validated using quantitative PCR (qPCR). qPCR Mastermix SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) was used, and the relative quantity of DNA sequence was determined using comparative quantification Ct (ΔΔCt) method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

3. Results

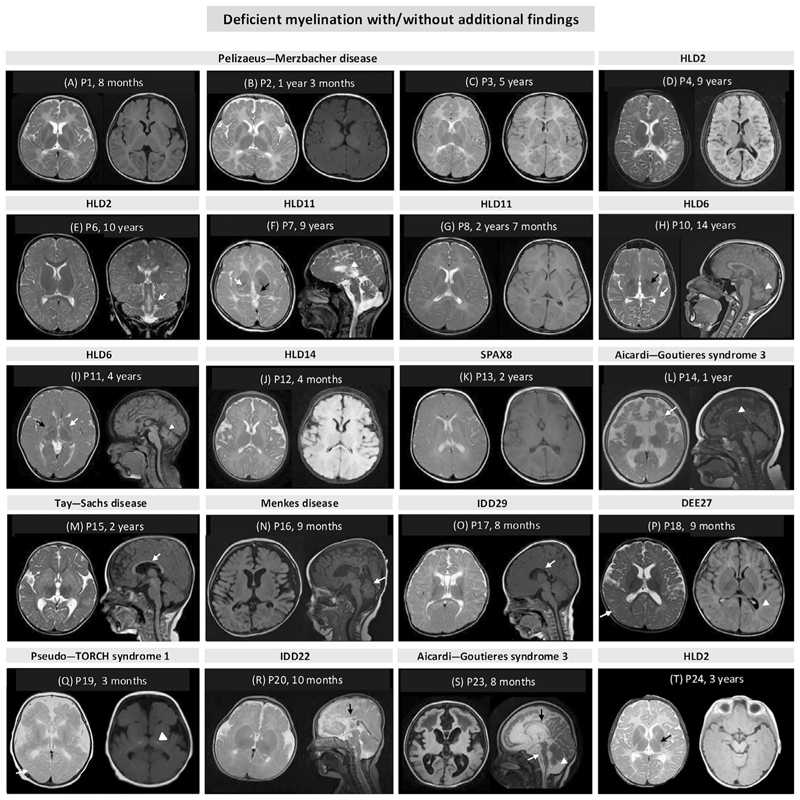

Our cohort comprises of 17 males (17/25, 68%) and 8 females (8/25, 32%) from 12 consanguineous (12/24, 50%) and 12 non-consanguineous (12/24, 50%) unrelated families. The age at examination ranged from infancy to 15 years with a median age of 2 years. Based on phenotype and neuroimaging findings, individuals (P1–P3, P6, P8, P14, P19, P21, and P24) from nine families (38%) could be clinically diagnosed. Of these, P1–P3, P6, P8, and P24 presented with diffuse cerebral hypomyelination and were clinically diagnosed with Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (PMD) or PMD-like disorder. On neuroimaging in individuals P14, P19, and P21, delayed myelination, intracranial calcification, cystic changes, white matter abnormalities, and thin corpus callosum were observed, suggestive of Aicardi–Goutières syndrome 3. Ten individuals P4, P7, P9–P12, P15, P22, P23, and P25 (42%) had a probable diagnosis and five families (20%) had no clinical diagnosis including individuals P13, P16–P18, and P20. The brain MRI findings for genetically diagnosed individuals are shown in Figure 1 (MRI was not available for publication for P22 and P25). Along with deficient myelination, other imaging findings consisted of thin corpus callosum, periventricular white matter changes, and cerebellar and basal ganglia abnormalities.

Figure 1. Brain MRI scans shows deficient myelination with/without additional findings.

Diffuse cerebral hypomyelination in axial T2-weighted and T2-flair images of (A) P1 (Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease), (B) P2 (Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease), (C) P3 (Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease), and (D) P4 (leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 2, HLD2); (E) subcortical hypomyelination in axial T2-weighted image and brainstem hyperintensities (white arrow) in coronal in T2-weighted image of P6 (HLD2); (F) hypomyelination, anterolateral thalamus hyperintensity (black arrow), and hypointense globus pallidus (white arrow) in axial T2-weighted image and thin corpus callosum (white arrowhead) in sagittal T2-weighted image of P7 (HLD11); (G) diffuse cerebral hypomyelination in axial T2-weighted and T2-flair images of P8 (HLD11); (H) cerebral hypomyelination, hypointense globus pallidus (black arrow) and optic radiation (white arrow) in axial T1-weighted and cerebellar atrophy (white arrow head) in sagittal T1-weighted images of P10 (HLD6); (I) deficient myelination, hypointense globus pallidus (white arrow) and putamen atrophy (black arrow) in axial T2-weighted and cerebellar atrophy (white arrowhead) in sagittal T1-weighted image of P11 (HLD6); (J) diffuse cerebral hypomyelination in axial T2-weighted and T2-flair images of P12 (HLD14); (K) deficient myelination in axial T2-weighted and axial T2-flair images of P13 (spastic ataxia 8, autosomal recessive, with HLD, SPAX8); (L) deficient myelination, cystic abnormalities in the frontotemporal white matter (white arrow), focal hypointensities indicative of calcifications, diffuse cerebral atrophy in axial T2-weighted image and thin corpus callosum (white arrow head) in sagittal T1-weighted image of P14 (Aicardi–Goutières syndrome 3); (M) deficient myelination in axial T2-weighted image and thin corpus callosum (white arrow) in sagittal in T1-weighted image of P15 (Tay–Sachs disease); (N) cerebral atrophy and deficient myelination in axial T2-flair image and cerebellar atrophy (white arrow) in sagittal T1-weighted image of P16 (Menkes disease); (O) bilateral symmetric white volume loss with deficient myelination both in subcortical white matter and centrum semiovale in axial T2-weighted image and thin corpus callosum (white arrow) in sagittal T1-weighted image of P17 (intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 29, IDD29); (P) deficient myelination and dysmyelination around periventricular (white arrowhead) and subcortical areas (white arrow) in axial T2-weighted and T2-flair images of P18 (developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 27, DEE27); (Q) deficient myelination, pachygyria and bilateral dense calcification involving the subcortical areas (white arrow) and basal ganglia (white arrow head), polymicrogyria involving the temporal lobes and simplified gyration in the frontal and parietal cortex and cerebral atrophy in axial T2-weighted and axial T2-flair images of P19 (pseudo-TORCH syndrome 1); (R) deficient myelination, thickened fornisis, abnormal cortical gyration, polymicrogyria in axial T2-weighted image, and partial agenesis of corpus callosum (black arrow) in sagittal T2-weighted image of P20 (intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 22, IDD22); (S) leukoencephalopathy, deficient myelination, cystic changes in frontal lobe in axial T2-flair images and hypoplasia of corpus callosum (black arrow), brain stem atrophy (white arrow), and cerebellar vermian atrophy (white arrow head) in sagittal T2-weighted images of P23 (Aicardi–Goutières syndrome 3); (T) diffuse cerebral hypomyelination and hyperintensities in the posterior limb of internal capsule (black arrow) and dysmyelination in axial T2-weighted image and axial T2-flair images of P24 (HLD2). Age mentioned in figures is the age when MRI was performed for the proband.

The flowchart in Figure 2 shows the sequential testing strategy employed for evaluation of affected individuals. Among nine individuals (P1–P3, P6, P8, P14, P19, P21, and P24) in whom a clinical diagnosis was made based on clinical and neuroimaging findings, individuals P1–P3 and P14 could be diagnosed through targeted testing and remaining five individuals were diagnosed using broad spectrum genomic testing (Figure 2, Table 1). These five individuals were diagnosed with HLD2 (P6 and P24), HLD11 (P8), and pseudo-TORCH syndrome 1 (P19). Individual P21 remained genetically undiagnosed. Nine individuals P4, P7, P9–P12, P22, P23, and P25 had a probable diagnosis of hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (HLD) and diagnosis was confirmed by broad genomic testing. In individual P15, Krabbe was thought of a probable diagnosis based on early clinical findings of neuroregression, white matter involvement, and a thin corpus callosum. Gap-PCR was performed in this proband to rule out the most common variant in GALC, that is, 30-kb deletion causative of Krabbe disease which was nondiagnostic (Rafi et al. 1995). Further, solo exome sequencing (ES) was performed, which revealed genetic diagnosis of Tay–Sachs disease.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram to show the genetic testing strategy employed in 24 families.

MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; PLP1, proteolipid protein 1; qPCR, quantitative PCR; RNASEH2C, ribonuclease H2 subunit C.

Table 1. The table shows genotypic details in the diagnosed families having the disorders with deficient myelination.

| Family ID | Individual ID | Age of examination/Gender | Genetic diagnosis achieved by | Disorder (#MIM) | Inheritance pattern | Gene (NM ID) | Variant | Known or Novel | ACMG/ ClinGen Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | P1 | 9 months/M | MLPA | Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (312080) | XL | PLP1 (NM_000533.5) | g.(?_103776942)_ (103790556_?)dup | Known | P (ClinGen CNV score: 1.3) |

| F2 | P2 | 2 years/M | MLPA | ||||||

| F3 | P3 | 6 years/M | MLPA | ||||||

| F4 | P4 | 9 years/F | Solo ES | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 2 (608804) | AR | GJC2 (NM_020435.4) | c.472_481dup p.(Ala161GlyfsTer23) | Novel | P (PVS1, PM2, PP3, PP4) |

| P5 | 11 years/M | ||||||||

| F5 | P6 | 11 years/M | Solo ES | c.404G > A p.(Trp135Ter) | Novel | P (PVS1, PM2, PP3, PP4) | |||

| F23 | P24 | 3 years/F | Solo ES | c.104G > A p.(Arg35His) | Novel | VUS (PM2, PP3, PP4) | |||

| F6 | P7 | 10 years/M | Mendeliome | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 11 (616494) | AR | POLR1C (NM_203290.4) | c.[32G > A:908G > A] p.[(Arg11Asn):Arg303Asn] | Novel Known | VUS (PM2, PP2, PP3, PP4) LP (PS4_M, PM2, PP2, PP3, PP4, PP5) |

| F7 | P8 | 2 years/M | Solo ES | c.221A > G p.Asn74Ser | Known | P (PS3, PM2, PP2, PP3, PP4, PP5) | |||

| F9 | P10 | 15 years/M | Solo ES | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 6 (612438) | AD | TUBB4A (NM_006087.4) | c.1228G > A p.Glu410Lys | Known | LP (PM1, PM2, PM6, PP2, PP3, PP4, PP5) |

| F10 | P11 | 5 years/F | Solo ES | c.745G > A p.Asp249Asn | Known | P (PS3, PS4_M, PM1, PM2, PM6, PP2, PP3, PP4, PP5) | |||

| F11 | P12 | 1 year/F | Solo ES | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 14 (617899) | AR | UFM1 (NM_016617.4) | c.-155_-153delTCA | Known | P (PS3, PS4_M, PM2, PP5) |

| F21 | P22 | 2 years/F | Solo ES | ||||||

| F12 | P13 | 1 year/F | Solo ES | Spastic ataxia 8, autosomal recessive, with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (617560) | AR | NKX6-2 (NM_177400.3) | c.516C > G p.(Tyr172Ter) | Novel | P (PVS1, PM2, PP3, PP4) |

| F13 | P14 | 1 year/F | Sanger sequencing | Aicardi–Goutières syndrome 3 (610329) | AR | RNASEH2C (NM_032193.4) | c.205C > T p.Arg69Trp | Known | P (PS1, PS3, PM2, PP3, PP4, PP5) |

| F22 | P23 | 8 months/M | Solo ES | c.398G > A p.(Gly133Asp) | Novel | VUS (PM2, PP3, PP4) | |||

| F14 | P15 | 2 years/M | Solo ES | Tay–Sachs disease (272800) | AR | HEXA (NM_000520.6) | c.805 + 1G > C | Known | P (PVS1, PS3, PM2, PP3, PP5) |

| F15 | P16 | 2 years/M | Mendeliome | Menkes disease (309400) | XL | ATP7A (NM_000052.7) | c.2388G > A p.(Trp796Ter) | Novel | P (PVS1, PM2, PP3) |

| F16 | P17 | 2 years/M | Trio ES | Intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 29 (616078) | AD | SETBP1 (NM_015559.3) | c.2879 T > G p.Leu960Arg | Novel | LP (PS2, PM2, PP3, PP4) |

| F17 | P18 | 9 months/M | Solo ES | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 27 (616139) | AD | GRIN2B (NM_000834.5) | c.2065G > A p.Gly689Ser | Known | P (PS3, PS4_M, PM1, PM2, PM6, PP2, PP3, PP5) |

| F18 | P19 | 1 year/F | Solo ES | Pseudo-TORCH syndrome 1 (251290) | AR | OCLN (NM_001205254.2 | c.(50 + 1_51–1)_ (729 + 1_730–1) | Known | P (PVS1, PM2, PP4) |

| F19 | P20 | 10 months/M | Trio ES | Intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 22 (612337) | AD | ZBTB18 (NM_205768.3) | c.1378C > T p.His460Tyr | Novel | LP (PM2, PM6, PP2, PP3, PP4) |

| F24 | P25 | 2 years/M | Solo ES | Leukodystrophy, hypomyelinating, 18 (618404) | AR | DEGS1 (NM_003676.4) | c.565A > G p.Asn189Asp | Known | LP (PS4_M, PM2, PP2, PP3, PP4) |

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; ES, exome sequencing; F, female; LP, likely pathogenic; M, male; M, moderate; MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; P, pathogenic; VUS, variant of uncertain significance; XL, X-linked.

A total of 14 monogenic disorders were observed in the cohort (Table 1). Of those, eight were autosomal recessive, four were autosomal dominant, and two were X-linked disorders. The disease-causing variants were found in genes related to myelin-specific or associated protein function (n = 3) in seven families; cytoskeleton (n = 1) in two families; membrane trafficking (n = 4) in five families; gene expression including DNA replication, transcription, transcription regulation, and DNA repair genes (n = 4) in six families; and cellular metabolism genes (n = 2) in two families (Figure 3A). We observed 20 causative variants in 14 genes (Table 1). The variant occurrence and types of variants are shown in Figure 3B,C. The pathogenicity of the variants was interpreted according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, Association for Molecular Pathology, and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) standards and guidelines (Figure 3D, Table 1) (Brandt et al. 2020; Richards et al. 2015; Riggs et al. 2020). All the identified variants are submitted to ClinVar database (Landrum et al. 2014). The detailed clinical features, radiological findings, disorders, variant details, and their respective classification have been provided in Table S1.

Figure 3.

(A) Diagrammatic representation of genes, where disease-causing variants were identified in our cohort, classified based on their molecular functions; (B) variant occurrence; (C) type of variants; and (D) American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) classification. VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

4. Discussion

Disorders with deficits in the CNS myelin are categorized into those with either permanent hypomyelination or delayed myelination. Permanent hypomyelination refers to a substantial deficit in myelin deposition in the brain and remains unchanged on neuroimaging obtained at least 6 months apart, whereas if the myelination improves, it is referred to as delayed myelination (Schiffmann and van der Knaap 2009; Steenweg et al. 2010). Most of the disorders with permanent and significant lack of myelin have been designated as HLDs. However, disorders exhibiting delayed myelination have extremely variable degree of deficits of CNS myelin and the etiology is highly heterogeneous. Notably, the terms “hypomyelination” and “delayed myelination” have been used interchangeably in the literature. Hence, we herein use the term “deficient myelination” for disorders exhibiting myelin defects varying from complete lack of myelin to a mild delay.

Diffuse and significant cerebral hypomyelination, which is a hallmark of HLDs, was observed in 14 families (P1–7, 9–12, 22, 24, 25) diagnosed with seven distinct disorders. Almost complete lack of CNS myelin, the hallmark of PMD and PMD-like disorders, was observed in P1–P4 and P24 (Figure 1A–D,T) (Barkovich and Deon 2016). HLD2 or PMD-like disease can be distinguished from PMD by the involvement of brainstem hyperintensities in T2-weighted images, which was evident in P6 (Figure 1E) (Barkovich and Deon 2016). Diffuse cerebral hypomyelination, along with hypointensities in the anterolateral nuclei of the thalamus, globus pallidus, pyramidal tracts at the level of the posterior limb of the internal capsule and optic radiations, cerebellar atrophy, and a thin corpus callosum in T2-weighted images are characteristic findings of POLR3-related leukodystrophies (Gauquelin et al. 2019; Steenweg et al. 2010). In our cohort, the MRI findings of P7 and P8 were consistent with HLD11 (Figure 1F,G). P10 and P11 manifesting HLD6 presented with characteristic findings of HLD6, that is, deficient myelination, hypointense globus pallidus, putamen atrophy, and cerebellar atrophy on T2 images (Figure 1H,I) (Joyal et al. 2019). Additionally, in P10, along with the characteristic findings of HLD6, the optic radiation involvement appears to be an atypical finding (Joyal et al. 2019; Van Der Knaap et al. 2007). Individuals with HLD14 also present with similar neuroimaging findings as individuals with HLD6 (Hamilton et al. 2017). However, P12 with HLD14 presented only with diffuse cerebral hypomyelination on neuroimaging (Figure 1J). P13 in our cohort with spastic ataxia 8 with HLD (SPAX8) showed only deficient myelination (Figure 1K). Most of the previously reported individuals with SPAX8 have been reported with permanent hypomyelination and cerebellar atrophy (Chelban et al. 2020). MRI findings in P14 and P23 (Aicardi–Goutières syndrome 3) (Figure 1L,S) and P15 (Tay–Sachs disease) (Figure 1M) are in concordance with the previously reported individuals in the literature (Ji et al. 2018; Lhamtsho et al. 2020; Steenweg et al. 2010). Although Menkes disease is typically associated with dysmyelination, cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, delayed myelination has also been documented (Manara et al. 2017). We observed predominantly deficient myelination in P16 affected with Menkes disease (Figure 1N). Deficient myelination was observed in P17 in our cohort which has been observed in two previously reported individuals with intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 29 (IDD29) (Figure 1O) (Jansen et al. 2021). Most individuals with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 27 (DEE27) do not have significant brain imaging findings (Sabo et al. 2023). However, delayed myelination has been associated with several DEEs (Platzer et al. 2017; X. Wang et al. 2023). Brain MRI in P18 with DEE27 revealed delayed myelination and dysmyelination, thus adding to the phenotypic spectrum of this disorder (Figure 1P). Delayed myelination as a novel finding was seen in one individual, that is, P19 (Figure 1Q) with pseudo-TORCH syndrome 1 caused due to the variants in OCLN. The other imaging findings in included calcifications in the white matter, polymicrogyria, simplified gyration, cortical atrophy, and cerebellar hypoplasia (O'Driscoll et al. 2010; Oner et al. 2021). The majority of the individuals with intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 22 (IDD22) are reported with abnormalities of corpus callosum (van der Schoot et al. 2018). Recently, one affected individual from a family of four is reported with delayed myelination (Li et al. 2023). In our cohort, individual P20 presented with delayed myelination and polymicrogyria in addition to partial agenesis of corpus callosum (Figure 1R). These findings expand the neuroimaging spectrum of IDD22.

There is a significant overlap in the clinical presentation of disorders with deficient myelination, especially those with permanent hypomyelination. A combination of brain imaging findings along with characteristic clinical features serve as a good handle for a clinical diagnosis. In our study, most of the individuals were either clinically diagnosed or had a probable diagnosis based on the neuroimaging findings. They were then evaluated by the testing strategy delineated in Figure 2. In our study, males (P1–P3, P6, and P8) with diffuse cerebral hypomyelination and in absence of any other significant differentiating feature PMD underwent MLPA for PLP1. Those who were nondiagnostic for these variants in PLP1 underwent ES. Individuals P6 and P8 were subsequently diagnosed with HLD2 and HLD11, respectively, which are close differentials of PMD through solo ES. Similarly in individuals P19 and P21, Sanger sequencing for RNASEH2C for founder variant p.Arg69Trp was performed, but on solo ES, P19 was diagnosed with pseudo-TORCH syndrome 3 while P21 remains undiagnosed. The variant p.Arg69Trp in RNASEH2C is a common variant in our population, which gives us the opportunity to utilize targeted testing where hypomyelination is observed in combination with intracranial calcifications (Hebbar et al. 2018). However, calcifications and cystic changes along with hypomyelination are present in other subtypes of Aicardi–Goutières syndrome and other monogenic disorders as well.

The synthesis of myelin is tightly regulated by the interplay among neurons, myelinated axons, oligodendrocytes progenitor cells, myelinating oligodendrocytes, NG2-glial cells, astrocytes, and microglial cells (Van Der Knaap and Bugiani 2017). Deficiencies in CNS myelin arise from decreased myelin production and/or maintenance. There are three integral structural myelin proteins that forms the myelin sheath, namely myelin basic protein, 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide-3′ phosphodiesterase (CNP), and proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1) (Wolf, ffrench-Constant, and Van Der Knaap 2021). Defects in two of these three proteins, CNP and PLP1, have been associated with HLDs (Stadelmann et al. 2019; Wolf, ffrench-Constant, and Van Der Knaap 2021). However, the majority of the genetic defects underlying disorders with myelin deficits have been determined in genes involved in several basic cellular processes such as gene expression, translation, intracellular metabolism, cytoskeleton organization, and protein trafficking (Urbik et al. 2020; Wolf, ffrench-Constant, and Van Der Knaap 2021). The etiopathogenesis of how these defects lead to myelin defects remains poorly understood. We report novel disease-causing variants in GJC2, POLR1C, NKX6-2, RNASEH2C, ATP7A, SETBP1, and ZBTB18 in our cohort (Table 1), thereby expanding the genetic spectrum of these disorders. We also report the presence of two previously published founder variants in our cohort, that is, p.Arg69Trp in RNASEH2C (P14) described in the Asian population and another variant, c.-155_-153delTCA in UFM1 (P12 and P22), from the Roma population (Hamilton et al. 2017; Hebbar et al. 2018). In most of the cases, the variant classification aligned with the submissions in ClinVar, with two exceptions. In individual P7, compound heterozygous variants c.[32G > A:908G > A] in POLR1C were found. While the variant c.908G > A is reported as variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in ClinVar, however we have classified as likely pathogenic. Similarly, the variant c.565A > G in DEGS1 in P25 is reported as VUS, but we are reporting it as likely pathogenic. We have reclassified them as likely pathogenic based on PS4 as moderate criteria, as these variants were reported in multiple unrelated patients with the similar phenotype in the literature and ClinVar database (Pant et al. 2019). Therefore, we also highlight that we should perform independent variant classification to ensure the most accurate interpretation based on the latest evidence.

Several studies over last two decades have reported clinical, radiological, and genetic landscape of disorders with deficient myelination in various populations and ethnic groups (Arai-Ichinoi et al. 2016; Ji et al. 2018; Numata et al. 2014; Steenweg et al. 2010; Yan et al. 2021). The yield of genetic testing for disorders with deficient myelination may vary and depend on the level of clinical and radiological expertise and the availability of diverse testing methodologies. Diagnostic rates varying from 40% to 94% has been reported across studies using different genetic testing methods and strategies (Arai-Ichinoi et al. 2016; Di Bella et al. 2021; Ji et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2021). In a cohort of 26 infants with probable HLDs, Arai-Ichinoi et al. (2016) used a sequential testing strategy where all individuals underwent karyotyping followed by chromosomal array and WES, which resulted in an overall diagnostic yield of 58% (Arai-Ichinoi et al. 2016). In a cohort of 119 individuals from China, 82% individuals were diagnosed using targeted testing and 12% by targeted gene panels (Ji et al. 2018). We have taken a combinatorial testing strategy that involves deep phenotyping followed by appropriate genetic testing (Table S1) to optimize the use of available resources (Figure 2). We employed MLPA for individuals with suggestive findings of PMD as PLP1 duplications are the most common variation for the classical form of PMD (Hoffman-Zacharska et al. 2013; Khalaf et al. 2022). Sanger sequencing was used to test the founder variant (c.205C > T) in RNASEH2C based on the neuroimaging and clinical features (Hebbar et al. 2018). In our study, the clinical diagnosis using targeting testing was achieved in 44% (4/9) families. While targeted testing and gene panels offer efficiency in identifying known conditions, they may inadvertently hinder the discovery of novel disease-gene associations underlying myelin disorders. Consequently, broader genomic approaches such as WES or whole genome sequencing have emerged as efficient tools for diagnosis as well as discovery. Notably, the diagnostic rate of myelin-related disorders using broad spectrum genomic testing is significantly high as most of these disorders are well-delineated monogenic conditions (Shukla et al. 2021). However, targeted testing is very valuable in few scenarios, that is, those with common/founder variants, small sized genes, and testing for atypical variants such as CNVs which are frequently missed in NGS-based tests. In the current study, WES was performed for families with probable or no clinical diagnosis as well as a clinical diagnosis with genetic heterogeneity. In our cohort, the molecular diagnosis was achieved in two families (2/2, 100%) using Mendeliome and 14 families (14/17, 78%) using solo WES. Trio-ES was performed in two families diagnosed with novel de novo variants in SETBP1 and ZBTB18. Overall, the diagnostic yield in our cohort is 92% which is comparable to a recent cohort investigated by genomic testing in the Chinese population (112/119, 94%) (Ji et al. 2018).

There are a few limitations in the current cohort. A follow-up MRI could not be obtained of the individuals in our study for evaluation of myelin progression. Also, we could not investigate the undiagnosed cases with other diagnostic tools such as whole genome sequencing or any other omics techniques such as transcriptomics or proteomics. Nonetheless, our cohort represents an endeavor to describe an efficient approach for diagnosing individuals with deficient myelination. Currently, there are no definitive treatments available for these disorders. However, genetic diagnosis empowers families to make informed decisions for family planning and reproduction options. It also helps clinicians to anticipate and address potential complications, provide supportive care, and monitor disease progression. Moreover, the knowledge of genes involved in the pathogenesis of these disorders will guide us to formulate appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the family members of the patient for their participation in this study. We also thank the National Institutes of Health, USA, and DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance for funding the project titled “Genetic Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders in India” and DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance for funding the project titled “Centre for Rare Disease Diagnosis, Research and Training” (IA/CRC/20/1/600002).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, United States, for the study “Genetic Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders in India” and DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance for the study “Centre for Rare Disease Diagnosis, Research and Training” (IA/CRC/20/1/600002).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Namanpreet Kaur contributed to analysis of the exome sequencing data, variant interpretation, Sanger validation, compiling the data, and drafting the manuscript, figures, and tables. Michelle C. do Rosario, Purvi Majethia, Selinda Mascarenhas, and Lakshmi Priya Rao have contributed to analyzing the exome sequencing data and validation of the results. Karthik Vijay Nair, Adarsh Pooradan Prasannakumar, and Bhagesh Hunakunti contributed to operating and optimization of the in-house exome sequencing and copy number variant analysis pipeline. Rohit Naik contributed to the Sanger validation of the identified genomic variants. Dhanya Lakshmi Narayanan and Vivekananda Bhat have contributed to clinical assessment, analysis, interpretation of genomic data, and genetic counseling of the recruited families. Shalini S. Nayak has contributed to the analysis of chromosomal microarray data. Suvasini Sharma, Ramesh Bhat Y., B.L. Yatheesha, Rajesh Kulkarni, Siddaramappa J. Patil, and Sheela Nampoothiri have referred families and contributed to patient evaluation and genetic counseling. Shahyan Siddiqui has contributed to the analysis of neuroimaging of the patients. Katta Mohan Girisha has contributed to funding acquisition, patient evaluation, study recruitment, analysis, interpretation of the genomic testing, and genetic counseling to the families. Stephanie Bielas has contributed to funding acquisition and planning of additional wet lab experiments. Anju Shukla has contributed to funding acquisition, patient evaluation, study recruitment, conceptualizing the manuscript, review and editing of the manuscript, and overall supervision. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Consent

Informed consent was taken from the family for publishing their data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Arai-Ichinoi N, Uematsu M, Sato R, et al. Genetic Heterogeneity in 26 Infants With a Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy. Human Genetics. 2016;135(1):89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H-G, Kim TK, Suk HY, Jung S, Jo D-G. White Matter and Neurological Disorders. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2020;43(9):920–931. doi: 10.1007/s12272-020-01270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Deon S. Hypomyelinating Disorders: An MRI Approach. Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;87:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt T, Sack LM, Arjona D, et al. Adapting ACMG/AMP Sequence Variant Classification Guidelines for Single-Gene Copy Number Variants. Genetics in Medicine. 2020;22(2):336–344. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson HM. Normal Myelination. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2013;23(2):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SH, Bylstra Y, Teo JX, et al. Analysis of Clinically Relevant Variants From Ancestrally Diverse Asian Genomes. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):6694. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelban V, Alsagob M, Kloth K, et al. Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of NKX6-2-Related Spastic Ataxia and Hypomyelination. European Journal of Neurology. 2020;27(2):334–342. doi: 10.1111/ene.14082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czopka T, Ffrench-Constant C, Lyons DA. Individual Oligodendrocytes Have Only a Few Hours in Which to Generate New Myelin Sheaths In Vivo. Developmental Cell. 2013;25(6):599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bella D, Magri S, Benzoni C, et al. Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophies in Adults: Clinical and Genetic Features. European Journal of Neurology. 2021;28(3):934–944. doi: 10.1111/ene.14646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K, et al. Discovery and Statistical Genotyping of Copy-Number Variation From Whole-Exome Sequencing Depth. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2012;91(4):597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauquelin L, Cayami FK, Sztriha L, et al. Clinical Spectrum of POLR3-Related Leukodystrophy Caused by Biallelic POLR1C Pathogenic Variants. Neurology: Genetics. 2019;5(6):e369. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geren BB, Raskind J. Development of the Fine Structure of the Myelin Sheath in Sciatic Nerves of Chick Embryos. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1953;39(8):880–884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.39.8.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton EMC, Bertini E, Kalaydjieva L, et al. UFM1 Founder Mutation in the Roma Population Causes Recessive Variant of H-ABC. Neurology. 2017;89(17):1821–1828. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar M, Kanthi A, Shrikiran A, et al. p.Arg69Trp in RNASEH2C Is a Founder Variant in Three Indian Families With Aicardi–Goutières Syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2018;176(1):156–160. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman-Zacharska D, Mierzewska H, Szczepanik E, et al. The Spectrum of PLP1 Gene Mutations in Patients With the Classical Form of the Pelizaeus–Merzbacher Disease. Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego. 2013;17(4):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen NA, Braden RO, Srivastava S, et al. Clinical Delineation of SETBP1 Haploinsufficiency Disorder. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2021;29(8):1198–1205. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00888-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Li D, Wu Y, et al. Hypomyelinating Disorders in China: The Clinical and Genetic Heterogeneity in 119 Patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0188869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal KM, Michaud J, Van Der Knaap MS, Bugiani M, Venkateswaran S. Severe TUBB4A-Related Hypomyelination With Atrophy of the Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum: Novel Neuropathological Findings. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2019;78(1):3–9. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf G, Mattern C, Begou M, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Massaad C, Massaad-Massade L. Mutation of Proteolipid Protein 1 Gene: From Severe Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy to Inherited Spastic Paraplegia. Biomedicine. 2022;10(7):1709. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10071709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klambauer G, Schwarzbauer K, Mayr A, et al. cn.MOPS: Mixture of Poissons for Discovering Copy Number Variations in Next-Generation Sequencing Data With a Low False Discovery Rate. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(9):e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: Public Archive of Relationships Among Sequence Variation and Human Phenotype. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:D980–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhamtsho D, Rajesh U, Saxena A, Bhardwaj G, Sondhi V. Novel RNASEH2C Mutation in Multiple Members of a Large Family: Insights Into Phenotypic Spectrum of Aicardi–Goutières Syndrome. BMJ Neurology Open. 2020;2(1):e000018. doi: 10.1136/bmjno-2019-000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Kang H, Zou Y, et al. A Novel Heterozygous ZBTB18 Missense Mutation in a Family With Non-Syndromic Intellectual Disability. Neurogenetics. 2023;24(4):251–262. doi: 10.1007/s10048-023-00727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, California) 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik P, Muthusamy K, Mankad K, Shroff M, Sudhakar S. Solving the Hypomyelination Conundrum—Imaging Perspectives. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2020;27:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manara R, Rocco MC, et al. Neuroimaging Changes in Menkes Disease, Part 1. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2017;38(10):1850–1857. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Md V, Misra S, Li H, Aluru S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. 2019 doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.1907.12931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Numata Y, Gotoh L, Iwaki A, et al. Epidemiological, Clinical, and Genetic Landscapes of Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophies. Journal of Neurology. 2014;261(4):752–758. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll MC, Daly SB, Urquhart JE, et al. Recessive Mutations in the Gene Encoding the Tight Junction Protein Occludin Cause Band-Like Calcification With Simplified Gyration and Polymicrogyria. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;87(3):354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner TO, Unalp A, Hiz S, Bayram E, Kaytan I, Cingoz S. OCLN Gene Variants Identified in Three Patients With Severe Neurodevelopmental Disorder Associated With Epilepsy, Intellectual Disability and Malformation of Cortical Development. Epileptic Disorders. 2021;23(6):843–853. doi: 10.1684/epd.2021.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant DC, Dorboz I, Schluter A, et al. Loss of the Sphingolipid Desaturase DEGS1 Causes Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019;129(3):1240–1256. doi: 10.1172/JCI123959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T, Rothstein JD. Oligodendroglia: Metabolic Supporters of Neurons. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017;127(9):3271–3280. doi: 10.1172/JCI90610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, et al. A Robust Model for Read Count Data in Exome Sequencing Experiments and Implications for Copy Number Variant Calling. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2012;28(21):2747–2754. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platzer K, Yuan H, et al. GRIN2B Encephalopathy: Novel Findings on Phenotype, Variant Clustering, Functional Consequences and Treatment Aspects. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2017;54(7):460–470. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplin R, Ruano-Rubio V, DePristo MA, et al. Scaling Accurate Genetic Variant Discovery to Tens of Thousands of Samples. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/201178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafi MA, Luzi P, Chen YQ, Wenger DA. A Large Deletion Together With a Point Mutation in the GALC Gene Is a Common Mutant Allele in Patients With Infantile Krabbe Disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 1995;4(8):1285–1289. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, et al. Technical Standards for the Interpretation and Reporting of Constitutional Copy-Number Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Genetics in Medicine. 2020;22(2):245–257. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM. On the Relation Between Fibre Diameter and Conduction Velocity in Myelinated Nerve Fibres. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Biological Sciences. 1982;217(1206):29–35. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo SL, Lahr JM, Offer M, Weekes AL, Sceniak MP. GRIN2B-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder: Current Understanding of Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. 2023;14:1090865. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2022.1090865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann R, van der Knaap MS. Invited Article: An MRI-Based Approach to the Diagnosis of White Matter Disorders. Neurology. 2009;72(8):750–759. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343049.00540.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Kaur P, Narayanan DL, Rosario MCDo, Kadavigere R, Girisha KM. Genetic Disorders With Central Nervous System White Matter Abnormalities: An Update. Clinical Genetics. 2021;99(1):119–132. doi: 10.1111/cge.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann C, Timmler S, Barrantes-Freer A, Simons M. Myelin in the Central Nervous System: Structure, Function, and Pathology. Physiological Reviews. 2019;99(3):1381–1431. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenweg ME, Vanderver A, Blaser S, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Pattern Recognition in Hypomyelinating Disorders. Brain. 2010;133(10):2971–2982. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbik VM, Schmiedel M, Soderholm H, Bonkowsky JL. Expanded Phenotypic Definition Identifies Hundreds of Potential Causative Genes for Leukodystrophies and Leukoencephalopathies. Child Neurology Open. 2020;7:2329048X2093900. doi: 10.1177/2329048X20939003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Knaap MS, Bugiani M. Leukodystrophies: A Proposed Classification System Based on Pathological Changes and Pathogenetic Mechanisms. Acta Neuropathologica. 2017;134(3):351–382. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Knaap MS, Linnankivi T, Paetau A, et al. Hypomyelination With Atrophy of the Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum: Follow-Up and Pathology. Neurology. 2007;69(2):166–171. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265592.74483.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schoot V, de Munnik S, Venselaar H, et al. Toward Clinical and Molecular Understanding of Pathogenic Variants in the ZBTB18 Gene. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 2018;6(3):393–400. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional Annotation of Genetic Variants From High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mei D, Gou L, et al. Functional Evaluation of a Novel GRIN2B Missense Variant Associated With Epilepsy and Intellectual Disability. Neuroscience. 2023;526:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf NI, Ffrench-Constant C, Van Der Knaap MS. Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophies—Unravelling Myelin Biology. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2021;17(2):88–103. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Ji H, Kubisiak T, et al. Genetic Analysis of 20 Patients With Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy by Trio-Based Whole-Exome Sequencing. Journal of Human Genetics. 2021;66(8):761–768. doi: 10.1038/s10038-020-00896-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.