Summary

A fascinating conundrum in cell signaling is how stimulation of the same receptor tyrosine kinase with distinct ligands generates specific outcomes. To decipher the functional selectivity of EGF and TGF-α, which induce Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) degradation and recycling respectively, we devised an Integrated Multi-layered Proteomics Approach (IMPA). We analyzed dynamic changes in receptor interactome, ubiquitylome, phosphoproteome, and late proteome in response to both ligands in human cells by quantitative mass spectrometry and identified 67 proteins regulated at multiple levels. We identified Rab7 phosphorylation and RCP recruitment to EGFR as switches for EGF and TGF-α outputs, controlling receptor trafficking, signaling duration, proliferation and migration. By manipulating RCP levels or phosphorylation of Rab7 in EGFR-positive cancer cells we were able to switch a TGF-α-mediated response to an EGF-like response or vice versa as EGFR trafficking was rerouted. We propose IMPA as an approach to uncover fine-tuned regulatory mechanisms in cell signaling.

Introduction

Cells respond to extracellular signals through transmembrane receptors, such as Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs). However, how core signaling cascades are orchestrated by different RTKs to elicit distinct cellular responses is still debated. Signaling specificity can be modulated by rewiring overlapping protein networks1, protein-protein interactions2, and differences in signal duration3. The spatiotemporal distribution of RTKs in distinct subcellular compartments has also been associated with signaling specificity4,5. For instance, the tight control of the endosomal distribution of activated EGFR6 or the dichotomy between receptor degradation in lysosomes and receptor recycling to the plasma membrane have been shown to affect signaling outputs7–10. Differential endocytic sorting of RTKs is now considered a fundamental process regulating signaling duration and thus long-term responses11. Consequently, studying the molecular basis of RTK trafficking has implications for understanding diseases such as cancer that are caused by aberrant RTK signaling or derailed endocytosis12.

The concept of functional selectivity is well-established for G-protein coupled receptors13. This phenomenon has scarcely been explored in the context of RTKs, although a better knowledge of RTK selectivity could aid in designing improved therapeutic drugs14. Using quantitative proteomics, we recently reported that FGFR2b trafficking, signaling duration, and responses are dictated by the ligand9, but it remains to be determined whether this can be generalized to other ligand-RTK pairs. To systematically examine how ligands affect RTK signaling we focused on EGFR and its ligands EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) and TGF-α (Tumor Growth Factor alpha), which induce differential sorting of the internalized receptor16. Yet, to our knowledge, their cellular effects have not previously been compared.

As an alternative to multi-parametric image analysis or genetic screens combined with data-driven statistics17,18, we performed a time-resolved analysis of EGFR signaling using mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitative proteomics, a powerful technology for large-scale analysis of complex and dynamic signaling networks19–22. We developed IMPA, an Integrated Multi-layered Proteomics Approach that combines different layers of information on EGFR signaling (interactome, phosphoproteome, ubiquitylome, and late proteome) with functional assays to provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying EGFR responses. Thus, we analyzed the dynamic crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitylation, the most prominent Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) regulating receptor signaling, trafficking, and cellular outcomes23, in response to two distinct EGFR ligands. Our comprehensive analysis represents a powerful resource, which expands previous proteomics studies focusing on single aspects of the EGFR signaling enigma24–27. We also demonstrated the strength of this multidisciplinary approach for decoding functional selectivity and highlighting key regulatory protein hubs by identifying Rab7 tyrosine phosphorylation and Rab coupling protein (RCP) recruitment to EGFR as ligand-dependent molecular switches, which determine EGFR trafficking and outputs in human cancer cell lines.

Results

Integrated Multi-layered Proteomics dissects EGFR signaling

To study functional selectivity of RTKs, we focused on EGFR stimulated with 100 ng/mL EGF or TGF-α using the epithelial cervix carcinoma cell line HeLa, which expresses moderate levels of EGFR and is amenable for proteomics, signaling and trafficking studies. We choose this ligand concentration, because it triggered maximum receptor phosphorylation at 2 min (Supplementary Fig. 1a), which ensured that the observed differences between ligands were not due to partial EGFR activation. This concentration lies beyond physiological levels of EGF and TGF-α in different body fluids and organs28.

Analyzing EGFR trafficking by confocal microscopy8, we observed that HA-tagged EGFR accumulated in the cytoplasm of cells stimulated for 8 or 40 min and recycled back to the cell surface after 90 min (Fig. 1a-b). However, consistent with previous reports16,29, TGF-α induced 91% EGFR recycling, whereas EGF treatment only resulted in partial EGFR recycling (22%). These results were confirmed by co-localization studies with EEA1 or GFP-tagged versions of Rab5, Rab7, and RAB11, established markers of early, degradation or recycling endosomes, respectively8. Endogenous EGFR was present in RAB5- and EEA1-positive early endosomes upon 8 min stimulation with both ligands (Fig. 1c-d and Supplementary Fig. 1b). At this time point most of the receptor was active, as demonstrated by recognition by the anti-phosphorylated EGFR tyrosine 1068 (Y1068) antibody, a marker of EGFR activation6 (Supplementary Fig. 1c-d). At 40 min however, EGFR displayed preferential accumulation in RAB7- or in RAB11-positive compartments depending on EGF or TGF-α stimulation, respectively (Fig. 1c-d), indicating ligand-dependent differences in receptor degradation and recycling. EGFR remained phosphorylated on Y1068 at 40 min upon TGF-α, but not EGF stimulation, and we observed active EGFR at the plasma membrane also upon 90 min treatment with TGF-α (Supplementary Fig. 1c-d). Taken together, these findings suggest that in our experimental conditions TGF-α induced the internalization and recycling of active EGFR, whereas upon stimulation with EGF, EGFR was active in early endosomes, but disappeared between 40 and 90 min. Accordingly, we confirmed that TGF-α was a stronger mitogen than EGF30 (Fig. 1e-f).

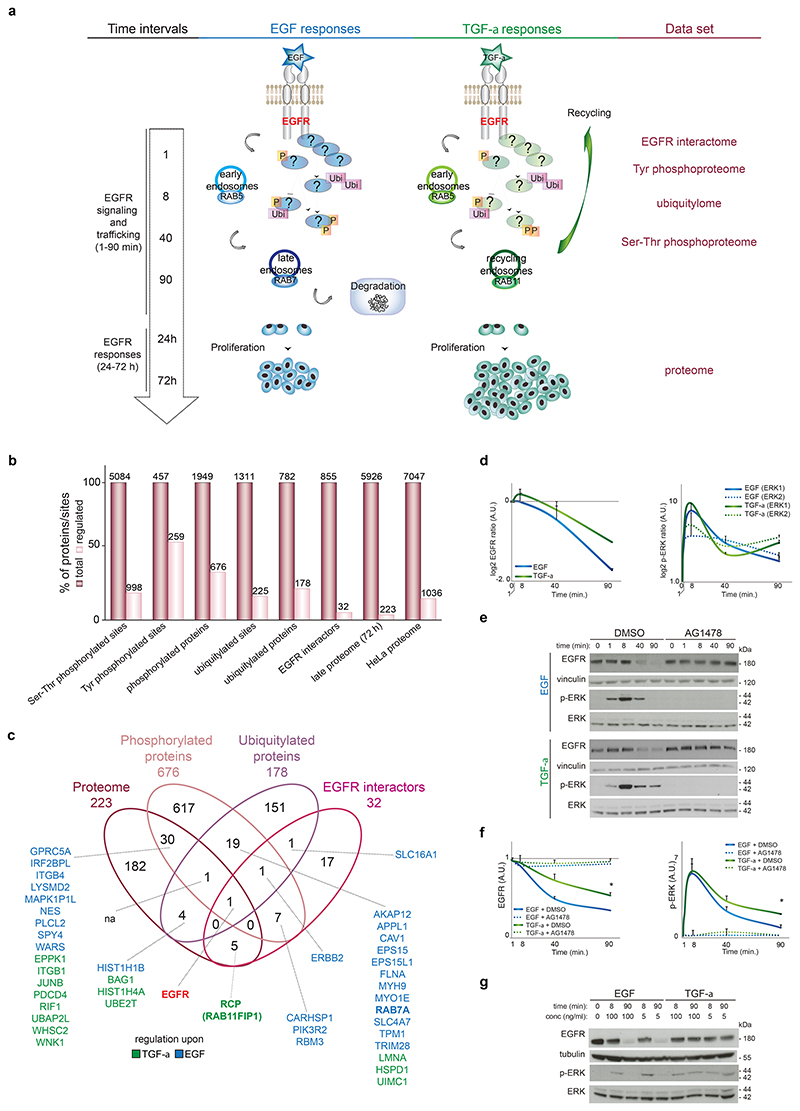

Figure 1. EGFR trafficking and responses depend on biased ligands.

(a) Quantification (see Online Methods) of total EGFR level (left panel), cell surface EGFR (middle panel) or internalized EGFR (right panel) upon EGF- or TGF-α-stimulation for different time intervals. Values in the graph represent the median ± SD of three independent biological experiments (about 100 cells counted in each experiment). (b) Representative images from (a), showing the internalization (cytoplasm) and recycling (plasma membrane) of EGF- or TGF-α-stimulated HA-EGFR (green) at different time intervals. Arrows indicate internalized receptor. Asterisks indicate cells with the receptor recycled to the cell surface. Bar, 5 μm. (c) Quantification (see Online Methods) of the presence of EGFR in endocytic markers-positive regions upon EGF- or TGF-α-stimulation. Values in the graph represent the means ± SD of three independent biological experiments, each done in three technical replicates and analyzing 10 fields for each of the three technical replicate. A.U., arbitrary units. *, p value<0.01 (Student´s two tailed t-test) (d) Representative images from (c), showing the presence of EGFR (green or red) in intracellular markers-positive regions in stimulated cells. Bar, 5 μm. Cell proliferation (e) and BrdU incorporation (f) of stimulated cells. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent biological experiments.. *, p value<0.05 compared to EGF (Student´s two tailed t-test). Black line represents control cells.

To analyze the molecular link between ligand-dependent early events (e.g. receptor trafficking) and long-term outcomes, we used a multi-layered and time-resolved quantitative proteomics approach (see Online Methods; Supplementary Fig. 2a) to analyze cell lysates following EGF or TGF-α stimulation for 1, 8, 40 or 90 min or 72h. We collected information on the EGFR interactome, tyrosine and serine-threonine phosphoproteome, ubiquitylome, and late proteome (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Tables 1-4). We assessed the quality of our MS data by the high degree of reproducibility between two biological replicates for all five datasets, and the identification of peptides with high mass accuracy and in the high intensity range (Supplementary Fig. 2b-d). Samples from cells stimulated with EGF or TGF-α for 1-90 min were analyzed for changes in phosphorylation and ubiquitin levels and we found 5541 phosphorylated and 1311 ubiquitylated sites mapping to 1949 and 782 proteins, respectively (class I sites; Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 2e, and Supplementary Tables 1-2). Of the 5541 phosphorylated sites, 457 (8%) were tyrosine-phosphorylated (Supplementary Fig. 2f), indicating an enrichment of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in our samples. Most of the PTM-modified peptides were singly phosphorylated or singly ubiquitylated (Supplementary Fig. 2g-h), in line with previous studies9,31. We deemed sites to be regulated if their SILAC ratios were more than two-fold in at least one experimental condition (see Online Methods). We found 1257 regulated phosphorylation sites (22.6%), 225 regulated ubiquitylated sites (17%) and more than half of all identified tyrosine-phosphorylated sites (259 over 457), supporting the crucial involvement of tyrosine phosphorylation in EGFR responses26 (Fig. 2b). For the receptor interactome analysis we performed immunoprecipitation of endogenous EGFR using lysates from the same cells described above and identified 855 proteins, of which 40 were dynamically recruited to EGFR in at least two time points (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figure 2a, and Supplementary Table 3; see Online Methods for the definition of ‘EGFR interactor’). To analyze the changes in the late proteome, we focused on the 72h time point and identified 5926 proteins, of which 223 showed substantial changes in abundance upon treatment (referred to as ‘regulated’) (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 4). By integrating the five data sets we covered 76.6% (7047 proteins) of the known proteome of HeLa cells32, of which 14.7% (1036 proteins) were regulated (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 2. Multi-layered proteomics of EGFR signaling shows ligand-specific EGFR regulation.

(a) Overview of the time scale for proteomics of EGFR signaling. (b) Number and percentage of identified and regulated sites and proteins. (c) Venn diagram indicating the number of proteins specifically regulated at different levels upon EGF (blue) or TGF-α (green) stimulation. na, none of the proteins were specifically regulated by either ligand. EGFR is highlighted in red. (d) Quantitation by MS of ERK1 and ERK2 Y202-T204-containing doubly phosphorylated peptide (right) and EGFR protein (left) upon EGF (blue) or TGF-α (green) stimulation. Values are the median ± range of two replicates (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). (e) The immunoblotting for EGFR, ERK and Vinculin is quantified in (f), where the values are the mean ± SD of three independent biological experiments. *, p value<0.05 (two-sample Student´s test on slopes). AG1478, EGFR inhibitor. (g) Lysates from stimulated cells with EGF or TGF-α at different concentration were immunoblotted as indicated. See also Supplementary Data Set 1 for uncropped gels.

We reasoned that central protein hubs in the EGF receptor network incorporate multi-level signals and would therefore be regulated on several levels. Thus, we prioritized proteins that were regulated in more than one dataset and short-listed 67 proteins, of which 30 were specifically regulated upon EGF and 15 upon TGF-α stimulation (Fig. 2c). Several proteins known to be involved in EGFR trafficking (EPS15, CAV1, RAB7)33 were regulated by both phosphorylation and ubiquitylation only in EGF-treated cells (Fig. 2c). Another protein involved in endocytosis, RCP (also known as Rab11FIP1)34, was not PTM-regulated, but TGF-α treatment increased both the abundance of this protein and its dynamic interaction with EGFR (Fig. 2c). These findings suggest that the two ligands control EGFR trafficking through different mechanisms.

EGFR was the only protein regulated in all the four datasets by both EGF and TGF-α (Fig. 2c). Confirming the MS-based quantitation of the total EGFR levels by Western Blot (WB), we observed that EGF treatment resulted in EGFR degradation between 40 and 90 min, whereas TGF-α induced receptor stabilization upon 90 min stimulation, in agreement with receptor recycling (Fig. 1, 2d-f and Supplementary Fig. 1b-d). We also found, both in the phosphoproteome and by quantitation of WB analysis that TGF-α stimulation led to sustained ERK signaling, contrary to the transient ERK phosphorylation in response to EGF (Fig. 2 d-f). ERK phosphorylation was not detectable in cells treated with the specific EGFR inhibitor AG1478, confirming that the response to both ligands was mediated by EGFR (Fig. 2e-f). The dose of ligands affected neither the level of EGFR nor the dynamics of ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2g). Collectively these data indicate that TGF-α-mediated stabilization of active EGFR influences signaling duration and that each ligand-EGFR pair uses specific mechanisms for the control of receptor endocytosis, resulting in distinct cellular outcomes.

Biased ligands specifically regulate PTMs

To obtain insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the differential responses generated by EGF and TGF-α, we analyzed the distribution of regulated sites and EGFR interactors over time. The number of regulated tyrosine phosphorylated sites was highest at 1 min, followed by regulated ubiquitylated sites at 8 min, and regulated Ser-Thr phosphorylation sites at 40 min. Similarly to the regulation of phosphorylated tyrosine, the highest number of proteins interacting with EGFR was found after one min upon both EGF and TGF-α stimulation (Fig. 3a). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed a clear separation of early and late time points and pointed to 8 min as the most divergent between EGF and TGF-α in all datasets (Fig. 3b), suggesting that signaling activated at 8 min is stimulus-specific.

Figure 3. Analysis of dynamic EGFR signaling indicates ligand-dependent regulation of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation.

(a) Number of sites and EGFR interactors regulated at each time point. (b) PCA of the log2-transformed ratios from the indicated datasets. Magenta line represents the separation of EGF and TGF-α responses at 8 min. (c) PCA of Tyr phosphoproteome from the indicated studies. (d) Sequence motif analysis of the ± 6 amino acid residues flanking the regulated phosphorylation site. (e) Immunoblotting for ERK and Vinculin upon prolonged stimulation quantified in (f), where values are the mean ± SD of three independent biological experiments.. *, p value<0.05 (two-sample Student´s test on slopes). See also Supplementary Data Set 1 for uncropped gels.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the six temporal profiles (clusters) based on fuzzy c-means clustering of 330 regulated phosphorylated and 52 regulated ubiquitylated sites revealed that biological processes, like proliferation, migration, and endocytosis, were enriched upon both EGF and TGF-α stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 3a-b). However, considering both the temporal pattern and the total amplitude of the PTM changes (defined by the similarity parameter S-score35), EGF and TGF-α regulated phosphorylation in a similar way, but ubiquitylation differentially (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Together with a difference in the number of ubiquitylated sites in cluster 6 (recycling responders) in favor of TGF-α, this finding suggests that TGF-α enhanced cellular ubiquitylation. Enriched GO terms of ubiquitylated sites included signaling and ubiquitin-mediated activity but also long-term cellular events, like DNA repair and protein folding (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Of the 66 enriched proteins (79 PTM sites) differentially regulated by the two ligands, 54 had more than one ubiquitylated sites and TGF-α specifically regulated 27 proteins (28 sites) (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Interestingly, we found that the ubiquitylation sites of 20 TGF-α-regulated proteins belonging to sustained temporal profiles (3 out of 6 clusters) were static upon EGF stimulation (cluster 0) (Supplementary Fig. 3a and d, Supplementary Table 2), thus strengthening the idea that TGF-α induced sustained ubiquitylation compared to EGF in our experimental conditions (Fig. 3a). TGF-α also regulated the chaperone protein BagAG1 and the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2T, involved in DNA repair36,37 in the proteome (Supplementary Fig. 3d, Fig. 2c), suggesting a previously unknown link between TGFα-induced ubiquitylation, sustained signaling and long-term responses.

Next, we analyzed the dynamic regulation of the phosphoproteome. Firstly, we compared the dynamic EGFR tyrosine phosphoproteome with the FGFR2b tyrosine phosphoproteome previously measured in the same cell line9. PCA separated the two tyrosine-phosphoproteomes (Fig. 3c), suggesting that each ligand-RTK pair affects signaling duration and specificity in a unique way. Secondly, to identify protein kinases activated downstream of EGFR we looked for enriched amino acid residues adjacent to the regulated phosphorylation sites. This disclosed that TGF-α favored a proline in the position immediately C-terminal to the phosphorylation site (Fig. 3d), a feature of many ERK substrates. We also observed that TGF-α, but not EGF, mediated prolonged activation of ERK up to 72h stimulation (Fig. 3e-f).

Finally, we studied the crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitylation upon EGFR activation by comparing the number of modified kinases, phosphatases, ubiquitin E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), representing the writers and erasers of these two PTMs38. Kinases (especially tyrosine kinases) and phosphatases were more phosphorylated than ligases and DUBs when compared to the expressed HeLa proteome32 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Tables 1-2). Although writers and erasers were in general mainly modified by the PTM they regulate, there was also an extensive crosstalk of the two PTM systems, with slightly higher spread of phosphorylation on ligases and DUBs compared to ubiquitylation on kinases and phosphatases (Fig. 4a). We found 260 proteins that were both phosphorylated and ubiquitylated and 25 of these were regulated at both PTMs level (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Tables 1-2). GO enrichment analysis of the regulated doubly versus singly modified proteins showed enrichment not only of signaling and endocytic processes (e.g. EGFR, EPS15, RAB7, ERBB2), but also of long-term responses like metabolism and proliferation (e.g. HSPD1, HUWE1, TRIM28, EIF3B) (Fig. 4 c-d, Table 1). This was consistent with a broader role of PTMs and in particular of ubiquitylation in cellular processes. We analyzed ligand-dependent regulation of these 25 doubly modified proteins, and found that EGF mainly induced phosphorylation at early time points (1-8 min), whereas TGF-α treatment resulted in sustained phosphorylation of the same proteins and in prolonged ubiquitylation of several of them (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, these data confirmed that phosphorylated and ubiquitylated proteins involved in signaling, trafficking and downstream processes have opposite temporal profiles in response to the two EGFR ligands.

Figure 4. Biased EGFR ligands differentially promote the crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitylation.

(a) Number of modified kinases, phosphatases, E3 ligases and DUBs identified in our dataset (left) and the same expressed as percentage of the total number of these enzyme categories identified in total in HeLa cells (right). *, p value<0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). (b) Number of total (left) and regulated (right) modified proteins. (c) GO term enrichment analysis of the 25 doubly modified proteins against proteins modified by one of the PTMs. (d) Functional network analysis of the 25 doubly modified proteins shown in Table 1, based on the STRING database and visualized using Cytoscape (ClusterONE plugin). Cluster 1, p value=7*10-6. Cluster 2, p value=0.049. EGFR and RAB7A are highlighted in orange and blue, respectively.

Table 1. List of the 25 doubly modified proteins.

Described in Figure 4. Regulated over total number of identified sites is shown.

| Number of regulated/total sites |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Names | Protein Names | Phosphorylated | Ubiquitylated |

| AKAP12 | A-kinase anchor protein 12 |

8/17 | 1/1 |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | 5/7 | 1/3 |

| APPL1 | DCC-interacting protein 13-alpha |

1/1 | 1/1 |

| CAV1 | Caveolin-1 | 1/3 | 5/6 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

11/14 | 8/11 |

| EIF3B | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit B (eIF3b) |

1/5 | 1/2 |

| EPS15 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15 |

3/4 | 1/2 |

| EPS15L1 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15-like 1 |

2/4 | 2/4 |

| ERBB2 | Receptor tyrosine- protein kinase erbB-2 |

3/5 | 2/2 |

| FLNA | Filamin-A (FLN-A) | 1/6 | 1/4 |

| HSPD1 | 60 kDa Heat shock protein |

1/1 | 3/4 |

| HUWE1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HUWE1 |

4/13 | 1/8 |

| LMNA | Prelamin-A/C | 3/10 | 1/3 |

| MYH9 | Myosin-9 | 1/3 | 1/4 |

| MYO1E | Unconventional myosin-Ie |

4/4 | 2/2 |

| NAP1L1 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 |

1/3 | 1/2 |

| RAB7A | Ras-related protein RAB-7a |

1/1 | 1/1 |

| RAD18 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RAD18 |

1/3 | 1/8 |

| RD23B | UV excision repair protein RAD23 homolog B |

1/1 | 2/6 |

| SLC4A7 | Sodium bicarbonate cotransporter 3 |

1/2 | 1/1 |

| TOM1 | TOM1-like protein | 1/1 | 1/3 |

| TPM1 | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain |

1/1 | 1/1 |

| TRIM28 | Transcription intermediary factor 1- beta (TIF1-beta) (TRIM18) |

1/5 | 1/2 |

| UBA1 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1 (Protein A1S9) |

1/1 | 1/11 |

| UIMC1 | BRCA1-A complex subunit RAP80 |

1/5 | 1/1 |

EGFR degradation depends on RAB7 phosphorylation on Y183

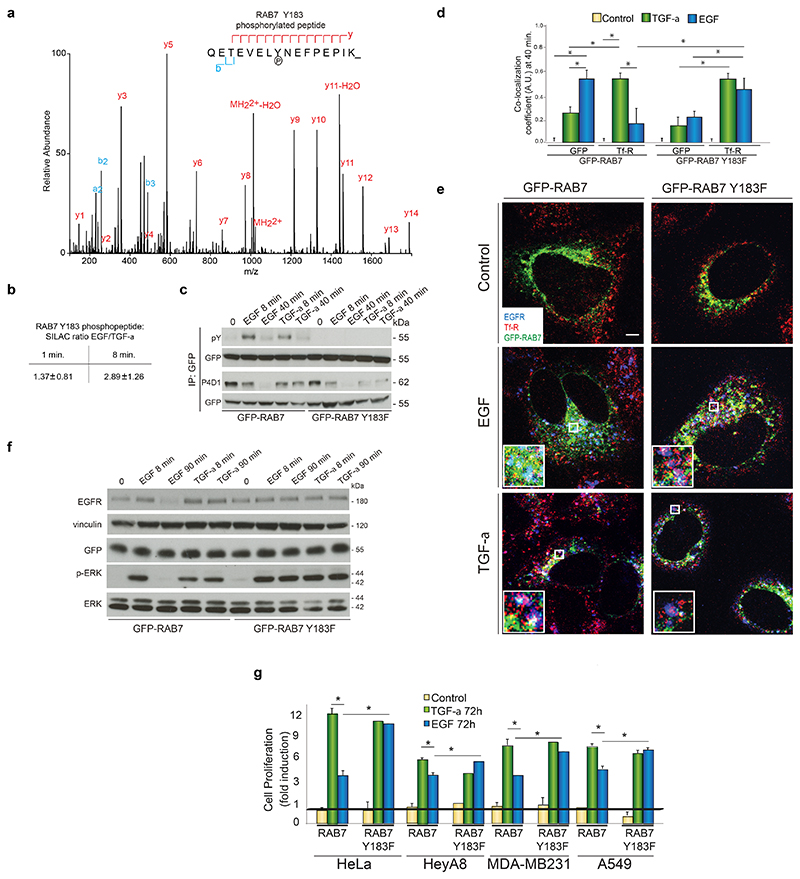

To assess the power of IMPA to uncover candidates mediating RTK functional selectivity, we focused on endocytic proteins regulated on multiple levels upon either EGF or TGF-α stimulation, as these two ligands induce opposite intracellular fate of EGFR (Fig. 1, 2c, Supplementary Fig. 1b-d). One such candidate indicated by IMPA was RAB7, a known marker of late endosomes deregulated in several diseases39,40. EGF doubly modified RAB7 at early time intervals, without affecting its total levels upon 72h stimulation (Fig. 2c). EGF promoted the phosphorylation of RAB7 on Y183 at 8 min (2.89±1.26 EGF/TGF-α SILAC ratio observed in three independent biological experiments; Fig. 5a-b, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 6). Upon transfection of cells with GFP-tagged wild type RAB7 (wild type) or RAB7 Y183F mutant, in which Y183 was changed to phenylalanine, we confirmed that EGF induced the phosphorylation of RAB7 on Y183 at 8 (but not 40 min) twice stronger than TGF-α (Fig. 5c). Changes in RAB7 phosphorylation might affect RAB7 ubiquitylation or its interaction partners. RAB7 mutant was equally ubiquitylated as wt in the absence of any stimulus with a slight downregulation upon stimulation and a more pronounced decrease at 40 min treatment with EGF (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table S2). We next stimulated cells transfected either with wt or mutant RAB7 with EGF for 8 min and GFP-tagged RAB7 was immunoprecipitated (Supplementary Fig. 6a). From two biological replicates showing good correlation (Supplementary Fig. 6b), we confirmed the similar ubiquitylation pattern on wt and mutant RAB7 at 8 min EGF stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 6c-e). These data point to a complex interplay between PTMs on RAB7. Furthermore, we found 15 endocytosis-related proteins interacting specifically with the RAB7 mutant compared to the wt (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Among these were signaling proteins, such as GRB2 and PI3K, members of the clathrin pit (CLTCL1, AP1B1, EPS15L1), the early endosome marker RAB5, and a protein associated to recycling (RABEP1)33. We therefore hypothesized that proteins binding to RAB7 Y183F but not to wt RAB7 may affect EGFR trafficking upon EGF stimulation. In cells stimulated with EGF for 40 min, EGFR was present in RAB7-positive compartments in wt cells, and in recycling- vesicles marked by Transferrin receptor (Tf-R)9 in RAB7 Y183F expressing cells (Fig. 5d and 5e). This finding suggests that in the presence of EGF the level of Y183 phosphorylation on RAB7 at 8 min acts as a molecular switch determining EGFR fate at later time points (40 min), probably by inducing the detachment of RAB7 from a specific set of endocytic proteins. This effect did not depend on a cellular de-localization of the RAB7 mutant compared to RAB7 wt (Fig. 5e) and was EGF-specific, as the majority of TGF-α-stimulated EGFR was still in Tf-R-positive vesicles both in wt and mutant RAB7 cells (Fig. 5d and 5e). These data also indicate that RAB7 Y183 phosphorylation did not affect TGF-α-dependent receptor recycling. Furthermore, EGF induced receptor stabilization and sustained ERK activation in the presence of RAB7 Y183F but not in wt cells, whereas TGF-α-dependent prolonged response was not affected by the mutant RAB7 (Fig. 2e, 5f) Collectively, these results indicate a link between ligand-dependent receptor recycling and signaling duration8,9,29.

Figure 5. RAB7 phosphorylation on Y183 is important for EGF-dependent EGFR degradation and outcomes.

(a) MS/MS spectrum of the phosphorylated Y183 peptide of RAB7. (b) SILAC ratio of the phosphorylated Y183 peptide of RAB7 upon stimulation for 1 or 8 min. (c) Lysates from stimulated cells transfected with RAB7-GFP or its mutant were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted as indicated. (d) Quantification (see Online Methods) of the presence of EGFR in RAB7-GFP-or Transferrin Receptor (Tf-R)-positive regions upon EGF- or TGF-α-stimulation for 40 min. Values in the graph represent the means ± SD. of independent biological experiments, each done in three technical replicates and analyzing 10 fields for each of the three technical replicate. A.U., arbitrary units. *, p value<0.05 (Student´s two tailed t-test). (e) Representative images from (d), showing EGFR (blue) in GFP-RAB7-(wt or its mutant, green) or Tf-R-(red) positive regions in 40 min-stimulated cells. Bar, 5 μm. (f) Lysates from stimulated cells transfected with RAB7-GFP or its mutant were immunoblotted as indicated. A representative image from three independent experiments is shown. (g) Cancer cell proliferation assay in stimulated cells upon transfection with RAB7 or its mutant. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent biological experiments..*, p value<0.05 compared to the indicated stimulus (Student´s two tailed t-test). Black line represents control cells. See also Supplementary Data Set 1 for uncropped gels.

Next, we verified the effect of RAB7 Y183 phosphorylation on cell proliferation in HeLa cells and other human cancer cell lines of different origin. In the presence of wt RAB7 all the tested cell lines proliferate less upon EGF than TGF-α stimulation (Fig. 1 e-f, 5g, Supplementary Fig. 6g). However, EGF and TGF-α stimulated proliferation to a similar extent in cells transfected with RAB7 Y183F (Fig. 5g), suggesting that EGF-mediated EGFR stabilization and recycling in the absence of RAB7 phosphorylation were crucial for the magnitude of the downstream response.

Overall, these data point to the higher extent of EGF-mediated phosphorylation of Y183 on RAB7 compared to TGF-α as a molecular switch priming EGFR for degradation, ultimately affecting signaling duration and long-term responses. EGF stimulation resulted in EGFR ubiquitylation and in the recruitment of the known E3 ligase CBL-B to the activated receptor (Supplementary Fig. 7a-c and Fig. 6a-b). This marks the receptor for degradation, as previously established33,41,42. Therefore, our data suggest that RAB7 phosphorylation is as important as EGFR ubiquitylation in controlling receptor degradation.

Figure 6. RCP promotes TGF-α-dependent EGFR recycling.

(a) Overview of the regulation of the MS-identified phosphorylation and ubiquitylation sites on EGFR. Each square indicates a time point and the color-scale represents the difference between EGF-over TGF-α−□□□□□□ □□□□□□□□□□□□□□. (b, d) Lysates from stimulated cells were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted as indicated. The inputs are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. One representative image from three independent experiments is shown. (c) Overview of the EGFR interactome based on the STRING database and color-code based on the difference between EGF over TGF-α□regulation. Each square indicates a time point. (e) Quantification (see Online Methods) of the presence of EGFR in RAB7-, RAB11-or RCP-positive regions upon EGF-or TGF-α stimulation for 40 min in cells depleted or not for RCP. Values in the graph represent the means ± SD. of three independent biological experiments, each done in three technical replicates and analyzing 10 fields for each of the three technical replicate. A.U., arbitrary units.*, p value<0.05 (Student´s two tailed t-test). (f) Representative images from (e), showing the presence of EGFR (red) in RAB7-or RAB11-positive regions in 40 min-stimulated cells depleted or not of RCP. Bar, 5 μm. (g) Lysates from stimulated cells where RCP expression was depleted by two different siRNA sequences or not were immunoblotted as indicated. (h) Lysates from stimulated cells transfected with GFP-RAB5 were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted as indicated. One representative image is shown from three independent experiments. See also Supplementary Data Set 1 for uncropped gels.

RCP mediates TGF-α responses

In our experimental conditions the ligand for EGFR recycling TGF-α induced sustained receptor ubiquitylation, and prolonged phosphorylation of the CBL family binding site Y1045 and of the GRB2 binding site Y1068 on EGFR42 (Supplementary Fig. 7a-c, Fig. 6a-b). Furthermore, EGFR showed the highest phosphorylation site occupancy (defined as the fraction of phosphorylation at a given site)43 for the peptide containing Y1045 and Y1068 upon stimulation with TGF-α as well as with EGF (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Finally, TGF-α promoted the recruitment of CBL-B, GRB2 and SHC to EGFR with different kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 7a-c, Fig. 6a-b). These data altogether indicate full receptor activation upon both stimuli. In contrast with EGF, TGF-α stimulation did not result in tyrosine phosphorylation of HRS (also known as HGS), another event required for EGF receptor degradation44 (Supplementary Fig. 7e, Supplementary Table 1). As TGF-α did not regulate RAB7 phosphorylation to the same extent as EGF (Fig. 5), we hypothesized that TGF-α-mediated EGFR trafficking occurred because TGF-α promoted the binding to the receptor of proteins belonging to the recycling pathway. Thus, we analyzed the interactome dataset for ligand-selective EGFR interactors (Supplementary Table 3; see also Online Methods). We found a strong network of proteins centered on EGFR, which could be divided into two groups. The first one encompassed 26 EGF-dependent interactors of EGFR including canonical RTK players (GRB2, CBL, SHC, VAV2, PI3K, SOS, PLCγ) (Fig. 6c). Some of these proteins were also found modified by PTMs and showed the same kinetics of regulation upon EGF treatment (Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and Supplementary Fig. 7f). The second group of EGFR interactors included 16 TGF-α enriched proteins comprising the cell cycle regulator CDC23, the adaptor DVL3, and proteins involved in vesicle transport (RCP, RAB6A) (Fig. 6c). Immunoprecipitation followed by WB analysis demonstrated that TGF-α, but not EGF induced the persistent formation of the EGFR_GRB2_RCP or of the EGFR_GRB2_DVL3 complexes (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig 7g-h). The sustained binding of GRB2 to the receptor was consistent with sustained phosphorylation of the GRB2 binding site Y1068 on EGFR upon TGF-α stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 7a, Fig 6a-b). These findings validated the interactome data and supported the idea that TGF-α facilitates the recruitment of unique proteins to EGFR. TGF-α promoted prolonged phosphorylation of most of the analyzed tyrosine sites on EGFR compared to EGF (Supplementary Fig. 7a, Fig. 6a). This kinetic was similar to that of GRB2, CBL-B, and RCP binding to EGFR (Fig. 6b-d), to the total EGFR levels, and to downstream ERK activation (Fig. 2e-g). Therefore, TGF-α stimulation triggers the activation of unique signaling proteins.

We focused on RCP because this RAB11 effector has previously been associated with integrin-mediated EGFR endocytosis34. In addition, TGF-α but not EGF, regulated RCP in both the interactome and proteome datasets (Fig. 2c). TGF-α-mediated EGFR trafficking and signaling duration changed in cells depleted of RCP by siRNA compared to cells transfected with control siRNA. EGFR was present in RAB11- and RCP-positive regions in wt cells stimulated with TGF-α for 40 min (Fig. 6e-f). However, the receptor was present in RAB7-positive compartments in the absence of RCP upon both EGF and TGF-α stimulation (Fig. 6e-f). Furthermore, in cells depleted for RCP and stimulated with TGF-α EGFR stability decreased resulting in transient ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 6g). These data suggest that RCP is a molecular switch for EGFR recycling and signaling in response to TGF-α. RCP bound to RAB11 and RAB5 upon TGF-α, but not EGF stimulation for 8 min (Fig. 6h), indicating that the fast recruitment of RCP to RAB5-positive early endosomes primes EGFR for recycling in our experimental conditions. These data also support the idea that the early time point 8 min is crucial for the regulation of trafficking and signaling upon each stimulus (Fig. 3b, 5, 6).

Next, we showed by WB that RCP protein levels were higher upon TGF-α than upon EGF treatment, whereas RAB7 levels were unaffected in lysates from HeLa cells and three other human cancer cell lines, confirming what we observed in the proteome dataset (Fig. 2c, 7a-b). As GO term analysis showed an enrichment of intracellular signaling and migration in TGF-α-stimulated cells for 72h (Fig. 7a), we addressed whether long-term ERK activation and cell migration depended on RCP. In cancer cell lines depleted of RCP and stimulated for 24-72h with TGF-α, ERK phosphorylation was absent and cell proliferation was reduced compared to wt cells (Fig. 7b-c). Furthermore, TGF-α did not induce cell migration in the absence of RCP (Fig. 7d). Conversely, EGF still activated ERK at 24h but not 72h stimulation and induced cell proliferation and migration in both RCP-depleted and in wt cells (Fig. 7b-d). RCP is therefore required for TGF-α-but not EGF-dependent long-term responses in several human cancer cells.

Figure 7. RCP mediates TGF-α-dependent cellular responses.

(a) Ratio vs. Intensity plot of the EGF (blue)- and TGF-α-induced differentially expressed proteins upon 72h stimulation. Insert, GO terms enrichment analysis. (b) Lysates from RCP-depleted and stimulated cells (HeLa or other cancer cells) were immunoblotted as indicated. One representative image from three independent experiments is shown. See also Supplementary Data Set 1 for uncropped gels. (c, d) Cancer cell proliferation (c) or migration (d) assays in stimulated cells upon RCP depletion. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent biological experiments. *, p value<0.05 compared to the indicated stimulus (Student´s two tailed t-test). Black line represents control cells. (e) Model of EGFR trafficking, signaling and responses based on this study. On the left, the early interaction between RCP, RAB5 and RAB11 (Fig. 6h) is represented. On the right, the orange arrow indicates the EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of RAB7.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive resource quantifying temporal changes in EGFR responses upon stimulation with two ligands inducing differential receptor trafficking (Fig. 7e). Sequential analysis of changes in the EGFR interactome, phosphoproteome, ubiquitylome and late proteome by MS-based quantitative proteomics, an approach here defined as IMPA, revealed EGF- and TGF-α-specific mechanisms for the regulation of EGFR endocytic routes, signaling, and long-term outputs.

Although thousands of modified sites and proteins can now be accurately and reproducibly identified and quantified routinely in large-scale MS-based proteomic studies, it still remains challenging to pinpoint the key drivers in the process of interest22. IMPA offers an original solution to this current dilemma. The integration of five different PTM-proteome layers of information allowed us to restrict the number of candidates regulated in an EGFR ligand-specific manner from 7053 identified proteins to 30 EGF- and 15 TGF-α-specific proteins that were regulated at multiple levels (Fig. 2). Our analysis might not reach the same depth in the number of identified proteins or modified sites as that obtained considering a single layer of information32,45,46. However, we covered close to 80% of the known HeLa proteome without using any biochemical trick for boosting the number of identifications, like treatment with phosphatase or proteasome inhibitors45,46. Furthermore, by manipulating RAB7 phosphorylation and RCP levels we were able to convert one specific ligand-response into the other one and vice versa, thus underscoring the power of our methodology. Therefore, including a multi-layered proteomics workflow in routine experimental design, in addition to the analysis of spatiotemporal regulation of signaling9 and of PTMs crosstalk38, will prove powerful to quantify differences in intracellular responses and solve cell signaling conundrums.

Our findings support the hypothesis that each ligand-RTK pair (i.e. TGF-α_EGFR) has developed its own regulatory mechanism for the control of receptor trafficking and downstream events. Therefore, findings on EGFR-dependent regulation of signaling cannot necessarily be generalized to all the other RTKs or even all ligands. For instance, FGF10 induces FGFR2b recycling by promoting the recruitment of SH3BP4 to the FGFR2b_PI3K complex9 and GGA3 binding to c-Met is necessary for receptor recycling10, whereas TGF-α-mediated EGFR recycling requires the binding of RCP to the receptor (Fig. 6). In contrast with data reporting enhanced pH sensitivity of TGF-α binding to EGFR, which promotes its early dissociation from receptor in early endosomal compartments16, we showed that EGFR is still active during TGF-α-mediated trafficking (Supplementary Fig. 1). Preserving a minimal kinase activity of EGFR after ligand dissociation might result in sufficient RCP binding necessary to drive receptor intracellular fate. Our data clearly indicate that RTK endocytic sorting for recycling depends on the recruitment of specific adaptors, ultimately affecting biological outputs, i.e. cell proliferation and migration7–10. Our findings suggest that recycling is not only an actively regulated process that affects long-term responses, but also that the manipulation of trafficking of certain RTKs might affect signaling outputs.

Our data also suggest that EGFR ubiquitylation is not the only determinant of receptor degradation via the ESCRT-0, -I, -II complexes48 because EGF-induced RAB7 phosphorylation on Y183 is key to degradation (Figure 5). Furthermore, EGFR is also ubiquitylated upon TGF-α stimulation, although TGF-α does not induce the phosphorylation of HRS, which is required for EGFR degradation44 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Curiously, TGF-α stimulation appears to induce more sustained Lysine 63 ubiquitylation of EGFR (Supplementary Fig. 7), which can signal lysosomal degradation, signaling, receptor trafficking or protein-protein interaction49. It is still unclear whether this increase in EGFR ubiquitylation in the presence of TGF-α correlates with higher grade of receptor recycling, as suggested for CCR750, or if recycling is a consequence of ubiquitylation (e.g. due to association with differentially-localized Lysine-63 specific DUBs). The intriguing hypothesis that EGFR trafficking - and possibly other biological processes - are regulated by a more complex and dynamic crosstalk between PTMs than anticipated is fascinating and requires further studies. For instance, whether EGF- and TGF-α-dependent RAB7 phosphorylation and RCP interaction with the receptor occur at low EGF concentrations (1-2 ng/mL), which was below the level of detection in our experimental conditions, will be highly valuable for understanding the EGFR system in tissues where EGFR ligand concentrations are low, and the receptor endocytosis is mediated by clathrin as opposed to conditions when EGFR endocytosis is clathrin-independent (high EGF concentrations)28. As perturbations of RTK trafficking machinery have been associated with cancer progression12, building an atlas of endocytic proteins specifically regulated by each ligand-RTK pair (e.g. via multi-layered proteomics) may pave the way for targeted intervention in human cancer. In the context of EGFR signaling, TGF-α deregulation has been associated to aggressive tumors, especially breast cancer, where its expression is controlled by estrogen30. Given that the TGF-α-dependent EGFR_RCP_GRB2 complex is central for sustained signaling activation and cell migration (Figures 6-7), a possible therapeutic scenario in breast and perhaps other cancers might be to selectively target this complex or TGF-α responses. This idea is supported by the facts that: (i) RCP is highly expressed in estrogen receptor-positive breast tumors and specifically controls breast cancer cell migration51; (ii) both TGF-α- and integrin, but not EGF-mediated migration depend on RCP and recycling in general (Fig. 7, 34); (iii) TGF-α signaling is sustained and signaling dynamics is now considered pharmacologically modifiable52; (iv) TGF-α induces a unique signature of ubiquitylated and phosphorylated proteins regulating not only signaling and endocytosis but also long-term processes, like transcription, DNA replication or damage, and proliferation. This finding suggests the possibility to fine-tune TGF-α signaling with surrogate ligands, as successfully done for EpoR53, in order to attenuate such cellular responses.

In conclusion, the multi-layered proteomics approach described here has the potential to improve our understanding of RTK functional selectivity54, offering a defined wealth of novel candidates for hypothesis generation. In a broader perspective, it might guide individualized medicine when integrated with data from other omics studies55.

Accession Codes

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange consortium56 via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD003523. Project name: Multi-layered proteomics of EGFR signaling. Project accession: PXD003523. Reviewer account details: reviewer63200@ebi.ac.uk. Password: TdBAodht.

The RAB7-GFP dataset has dataset identifier PXD001996. Project name: Multi-layered proteomics of EGFR signaling_RAB7 data. Project accession: PXD001996. Reviewer account details: reviewer53823@ebi.ac.uk. Password: R6JzF7Hh.

Online Methods

Reagents

The following commercial reagents were used: EGF and TGF-α (PrepoTech); DMSO and BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich); the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (Cell Signaling Technology); tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated transferrin (TRITC-Tf-R) (Invitrogen).

Antibodies (Supplementary Table 7): Rabbit anti-EGFR (Upstate) used in WB and immunoprecipitation analysis); mouse anti-EGFR (Calbiochem) used in immunofluorescence and immunoprecipitation analysis); mouse anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10) (EMD, Millipore); mouse anti-vinculin and mouse anti-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich); Rabbit anti-DVL3, Rabbit anti-RAB7, Rabbit anti-K48 and anti-K63, Rabbit anti-PI3K, Rabbit anti-phospho EGFR Y1045 and anti-phospho EGFR Y1068, mouse anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (E10) and Rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (137F5), mouse anti-phospho-tyrosine (P-Y100), Rabbit anti-SHC, Rabbit anti-HRS/HGS used for WB detection (Cell Signaling Technology); mouse anti-poly-ubiquitinylated conjugates (clone FK1) (Enzo Life Sciences); mouse anti-CBL-B (G-1), mouse anti-GFP (B-2), Rabbit anti-RAB5A (S-19), mouse anti-ubiquitin (P4D1), goat anti-EEA1 (Santa-Cruz Biotechnologies); mouse anti-GRB2 (BD Biosciences); Rabbit anti-RAB11 (Invitrogen); Rabbit anti-RAB11FIP1 (RCP) (Novus Biologicals); mouse anti-HA tag, used in immunofluorescence, (HA.11, Covance); Rabbit anti HRS/HGS for immunoprecipitation of HRS (Abcam).

Expression Vectors

The pcDNA3.0 vector encoding N-terminally HA-tagged EGFR was kindly provided by Y. Chen (Shanghai, China). The cDNA for RAB5-GFP was from M. Zerial (Dresden, Germany). The cDNA for RAB11-GFP was from F. Senic-Matuglia and B. Goud (Institute Curie, Paris, France). The cDNA for RAB7-GFP used in the immunofluorescence analysis shown in Figure 1a was from B. van Deurs (University of Copenhagen, Denmark). The GFP-tagged human RAB7 (GFPRAB7a) and its mutant containing phenylalanine (F) at position 183 (RAB7-Y183F) were synthesized by GeneArt (Invitrogen), cloned into the pCEP4 vector and used in all the other figures.

Cell Culture and SILAC labelling

Human epithelial cervix carcinoma HeLa cells, breast adenocarcinoma cells MDA-MB231, lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells were purchased from ATCC. Ovarian cancer cell line HeyA8 was kindly provided by Dr. U. Cavallaro (Milan, Italy). We have not performed specific authentication of the cell lines used in this study. The cell lines have been chosen on the basis of their endogenous expression of EGF receptor and the fact that they respond to EGF and TGF-alpha treatment. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), 100μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), at 37°C, in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All experiments were performed at 80% confluence. All cells were tested for mycoplasma with a PCR-based method every third week.

For quantitative mass spectrometry, HeLa cells were labeled in SILAC DMEM (PAA Laboratories) lacking arginine and lysine, as previously described9.

Transfection and RNA Interference

HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s instructions, and all the assays were performed 36 hours after transfection, as described8,9. Double-strand, validated Stealth siRNA oligonucleotides targeting human RAB11FIP1 (RCP) (sequences: 5’-GGUCCUCAAACAGAAGGAAACGAUA-3’; 5’-GAAGACUACAUUGACAACCUGCUUG-3´ and 5´-UCCGCAUCCCGACUCAGGGUUGGCAA-3´, called siRNA#1, siRNA#2 and siRNA#3, respectively) were purchased from Invitrogen. HeLa cells were transfected either with siRNA#1 and siRNA#2 (Figure 6) to test off-target effects or with a mixture of all RCP-targeting siRNAs (in all the other experiments), as previously described9. A Negative Control Med GC siRNA duplex was used as a negative control (Invitrogen, Cat. Number 12935300). Silencing of gene expression was monitored by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting of cell lysates with antibodies against RAB11FIP1 (RCP) (Figure 6).

Cell Lysis, Immunoprecipitation, and Western blots

Cells were cultured in complete medium, and then serum-starved overnight in serum-free medium. Cells were stimulated for the indicated time points with 100 ng/mL of EGF or TGF-α. Ligands have been replenished every 24 hours for long-term (24-72 h) stimulation. When needed, cells were pre-incubated for 2 hours with chemical inhibitors at the following concentrations: 500 nM AG1478. Control cells were pre-incubated with DMSO alone. After stimulation, cell extraction and immunoblotting were performed as described9. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with analogous results.

Immunoprecipitation of EGFR, GFP-tagged RAB5 or RAB7 and its mutant or GRB2 from cell extracts was performed as described9, using a mixture of anti-EGFR antibodies, anti-GFP (B-2), and anti-GRB2 antibodies, respectively. Immunoprecipitation of HRS was performed as above but using high-salt (up to 500 nM NaCl) in the lysis buffer for washes. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with analogous results.

Quantification of immunoblotting was performed using the ImageJ software and images were processed with Photoshop and Illustrator software (CS5 version; Adobe).

Original images of gels used in this study can be found in Supplementary Data Set 1.

Cell Proliferation Assays

HeLa cells transfected or not with RAB7-GFP and its mutant or depleted of RCP were seeded in quadruplicate on 24-well plates at 2x104cells/well, serum-starved overnight and treated for three days with 100ng/mL EGF or TGF-α, replenished every 24 hours. Viable cells were counted using the Trypan blue exclusion method and the ratio to unstimulated cells at time 0 was determined for each time point, as previously described9. Values represent the mean ± s.e.m. from at least three independent experiments. BrdU incorporation assay was performed as described9.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration was measured using a two-chamber Transwell system (5-mm pores; Boyden chamber; Costar), as described9. Migration was allowed for 24 hours at 37°C. Cells were then counted in 10 random fields per filter, using AxioImager A2 (Carl Zeiss) with a Plan NEOFLUAR 20X/0.5 NA objective, equipped with a Monocrome AxioCam camera and the analysis software AxioVision. Results represent the mean ± s.e.m of at least three independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described9. To detect HA-EGFR, cells were stained with AlexaFluor488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Coverslips were then mounted in mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories).

Quantification in Figure 1a-b

for each time point and each treatment, the presence (total) and the localization (cell surface vs. internalized) of HA-EGFR were assessed in seven randomly chosen fields. Approximately 100 cells per condition (both acid-washed and not) were analyzed from three independent experiments. The results are expressed as the percentage between the number of HA-EGFR-positive cells (green) and total cells (corresponding to DAPI-stained nuclei) and referred to the values obtained at time zero.

For co-localization experiments, cells were acid-washed, fixed, permeabilized with 0.02% saponin (Sigma), treated with a primary antibody against EGFR, phosphorylated Y1068, EEA1 or RCP for 60 min at 37°C, and stained with AlexaFluor488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse, CY3-conjugated goat anti-mouse or Alexa647-donkey anti-mouse; Alexa647-donkey anti-Rabbit; CY3-conjugated donkey anti-goat; Alexa647-donkey anti-mouse secondary antibodies, respectively. Samples treated with TRITC-Transferrin (to stain Transferrin Receptor, Tf-R), added to the medium at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL, were kept in the dark. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Coverslips were then mounted in mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories). All the images were acquired at room temperature with a confocal microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss) mounted on a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Axiovert 100M; Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.40 NA DIC M27 oil immersion objective using standard settings: DAPI and Alexa Fluor 488/GFP, Alexa Fluor 568, and Alexa Fluor 647 dyes were excited with 405-, 488-, 546-, and 633-nm laser lines, and emitted light was collected through band pass 420-480-, 505-530- and 560-615-nm and long pass 615-nm filters, respectively. Pinhole size was set to 1 airy unit or opened slightly for all wavelengths acquired if the signal intensity was otherwise too low. Zoom was 2.5X. Image acquisition, analysis and quantification were performed with the ZEN2010 software (Carl Zeiss). Raw images were exported as TIF files, and if adjustments in image contrast and brightness were applied, identical settings were used on all images of a given experiment.

The quantitation of the presence of EGFR in Rabs-GFP or Tf-R-positive region was performed blindly on 10 images for each condition in three independent experiments by setting the same intensity threshold for all the images and using the Pearson´s correlation coefficient, which provides information on the intensity distribution within the co-localization region (range -1/+1 where 0=pixels distributed in a cloud with no preferential direction). We also used object-based method to evaluate the co-localization of EGFR with GFP-tagged proteins57 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1b). After anisotropic diffusion filtering for noise removal, pixel intensities of each image were normalized to range between 0 and 1 and contrast was increased to remove background by histogram equalization using custom-developed Matlab 8.6 programming language. Green channel was subjected to the automatic threshold Otsu method thus producing a binary image. The latter was used to create masks over the red channel high lightening only endosomes region. Various co-localization parameters along with correlation values were computed within endosomes region between the green and the red channel. Co-localization performance was evaluated by Spearman´s correlation coefficient along with p-values for testing the hypothesis of no correlation. Mann-Whitney U test was used for the analysis of the entire dataset and Cohen´s distance was used to compare difference in co-localization between four replicates to avoid effect sizes.

Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

Sequential enrichment of Post Translational Modifications (PTMs)

HeLa cells from the three SILAC conditions were lysed at each time points in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 5 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) supplemented with 1 complete® protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) and N-ethylmaleimide to block cysteine-based proteases such as deubiquitylases (Sigma). As we were mainly interested in cytoplasmic/plasma membrane early signaling we performed cell lysis in mild conditions and discarded the chromatin pellet that is usually enriched in highly ubiquitylated proteins. Lysates were prepared as previously described9 before peptides purification using reversed-phase Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters) and elution with 50% acetonitrile. Ubiquitylated peptides were enriched as described previously58 and fractionated using microcolumn-based strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography as described previously59 and eluted at increasing pH. The supernatant from ubiquitylated-enriched immunoprecipitates was kept on ice for subsequent phosphorylated tyrosine peptide enrichment, performed as described60. The supernatant from tyrosine phosphorylated-enriched peptides was further enriched for phosphorylated serine and threonine-containing peptides, using titansphere chromatography as described previously60.

Pull-downs

After stimulation and lysis as described before, SILAC labeled HeLa cell lysates (10 mg for each SILAC condition) were pre-cleared with anti-Rabbit and mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with Protein G Sepharose beads (Invitrogen), and left on inversion rotation for at least 4 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 1000g for 5 min, cleared samples were incubated with anti-EGFR antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein G Sepharose beads were added for 1 h at 4°C and the immunoprecipitated proteins were washed 5 times with ice-cold lysis buffer. For the interactome analysis of RAB7, 5 mg of proteins for each SILAC condition were treated in parallel and subjected to pre-clearing steps as described above. Cleared samples were then incubated with GFP-trap beads (Invitrogen) for 2 h at 4°C.

Eluates were then combined and resolved on SDS-PAGE and in-gel digested with trypsin as described61.

Proteome analysis

SILAC-labelled cells were lysed at 4°C in modified RIPA buffer. 50 μg protein amounts from each SILAC condition were mixed prior to SDS-PAGE and in-gel digested with trypsin.

Liquid chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Peptides from all samples were concentrated and desalted on C18 StageTips as described previously62, and analyzed using an EASY-nLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to a Q Exactive, a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos (for samples shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a-d) or a Q-Exactive Plus (for RAB7 interactome analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. 4e-g) mass spectrometers (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific) through a nanoelectrospray ion source. Peptides were separated in a 15 cm analytical column (75 μm inner-diameter) in-house packed with 1.9 μm reversed-phase C18 beads (Reprosil-Pur AQ, Dr. Maisch) with 80 min (for ubiquitylated peptides, EGFR interactome, proteome analysis) or 135 min (for phosphorylated peptides analysis and RAB7 interactome analysis) gradients. The instruments were operated in data-dependent acquisition mode with settings as described63.

Raw MS Data Analysis

Raw data were analyzed by the MaxQuant software suite64, either version 1.0.14.7 using the MASCOT search engine (v. 2.3.02) (EGFR interactors analysis) or version 1.1.2.7 (analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. 4), 1.3.10.9 (ubiquitylated and phosphorylated peptides) and 1.4.1.4 (proteome and Rab7 interactome analysis) with the integrated Andromeda search engine65. Proteins were identified using parameters previously decribed9.

Data Analysis

For the analysis of ubiquitylated and phosphorylated peptides, only peptides with site localization probability of at least 0.75 (class I, shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 6)26 were included in the bioinformatics analyses. The ratios of identified and quantified modified sites were normalized to the ratio of EGFR at 1 min upon stimulation with EGF or TGF-α using the unmodified peptides to account for uneven efficiency during individual experiments performed in parallel. To identify regulated modification sites we compared the distributions of the ratio of all quantified modified peptides with all unmodified peptides that specify our technical variance and sites with a SILAC ratio higher than 2 or lower than 0.5 were considered regulated. Each time point was considered an independent experiment and we defined a site regulated if its SILAC ratio was higher than 2 or lower than 0.5 in at least one experimental condition (upon EGF or TGF-α stimulation for one of the time points in one of the replicates). We considered proteins to be TGF-α-dependent EGFR interactors if their TGF-α/EGF SILAC ratio at each time point was higher than 2. We considered proteins to be EGF-dependent EGFR interactors if their TGF-α/EGF SILAC ratio at 1-40 min (when EGFR was still present and not degraded) point was lower than 0.5. Therefore, our definition of regulated site (either up- or down-regulated) is quite broad. This allowed the best comparison of the two dynamic responses described here. The definition of ligand-specific EGFR interactor takes into account the total level of EGFR at each time point. Counting of different protein categories was based on this definition (Figures 2b-c, S1e-h, 3a, 4a-b, S3, 6b). To visualize the temporal regulation of modified sites (Figures S3 and S5a), heat maps of the log2 of the EGF or TGF-α ratios were created using the software R.

For unsupervised cluster analysis of the data the log2-ratios of all phosphorylation and ubiquitylation sites that showed a ratio at all the time points were z-scored (by subtracting the mean and dividing for the standard deviation) and subjected to clustering by the fuzzy c-means algorithm in GProX 1.1.12., by requesting six clusters with a fuzzification parameter of 2 and 100 algorithm iterations66. Subsequently, all Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms that occurred at least five times in a cluster were tested for enrichment in the cluster compared to the group of non-regulated sites (cluster 0, static sites) by Fisher’s exact test. GO terms that obtained a p-value below 0.05 after correction for multiple testing by the the Benjamini and Hochberg method was regarded as significantly enriched.

The S-score was calculated as described35. To identify the biological functions associated with different ranges of S-score the modified sites were divided into quintiles based on their attained S-score. Subsequently, Fisher’s exact test was used to extract for each quintile the GO biological process terms enriched compared to the sites in the remaining four quintiles. Only GO terms occurring at least three times in a quintile were included in the analysis and a p-value threshold of 0.05 after correction for multiple testing by the Benjamini and Hochberg method was used (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

The overview of proteins was manually curated based on either STRING database67 and visualized in Cytoscape (version 3.1). Clusters represented in Figure 4e were obtained using the Cytoscape plug-in ClusterONE. PCA was performed using the Perseus software (www.coxdocs.org). For identification of potential kinase motifs the sequence window of the regulated phosphorylation sites were compared to the non-regulated sites using the IceLogo resource68 with default parameters. For interactome and proteome data, protein sequence coverage of at least 5% was required. Proteins recruited to RAB7 and its mutant with SILAC ratios higher than 2-fold or lower than 0.5-fold in at least one condition were considered as ‘regulated’ interactors. In the EGFR dataset ratios of identified interactors were normalized to the ratio of EGFR upon 1 min stimulation with each ligand to account for uneven efficiency during individual pulldowns performed in parallel. From the 855 identified proteins all contaminants, ribosomal and proteasomal proteins have been filtered, resulting in 278 proteins. Proteins with a SILAC ratio quantified in at least two time points (dynamic interactors) are shown in Supplementary Table 3 (list of 41 proteins). The overview of these 41 EGFR dynamic interactome (shown in Fig.6) was based on the STRING database and color-code based on the difference in the regulation between the two stimuli. An interactor was defined as ‘stimulus-regulated’ whether it had either a TGF-α/EGF ratio >2-fold at 90 min stimulation, a TGF-α/EGF or EGF/ TGF-α/ratio >2-fold at one of the other time point. This criterion was based on the EGFR levels at the different time points.

For the analysis of late proteome, proteins showing significant changes in abundance (P<0.05, significance B test) were referred to as ‘regulated’ (Supplementary Table 4). The column “Significance B” and “Significance B - BH adjusted p-values” report values calculated by the Perseus software64 before and after correction for multiple testing by the Benjamini and Hochberg method, respectively. GO analysis shown in Figure 7a was performed using DAVID69. Significantly over-represented GO terms within the proteome data were represented in bar plots.

For the Venn diagram shown in Figure 2c, we collected in Supplementary Table 5 the 7053 non-redundant accession keys found in the "Uniprot protein ID" columns in Supplementary Tables 1-4. All counts of regulated proteins were based on this gene-centric table.

We estimated the phosphorylation site occupancy based on regulated phosphopeptide SILAC ratios, as previously described43.

Statistical Analysis

The SILAC experiments have been performed in duplicates. All the other experiments have been performed in at least triplicates. Results shown are mean ± SD or ± s.e.m. and P value was calculated by Student´s two tailed t-test, Wilcoxon test with alpha 0.05, or Fisher´s exact test, as indicated. In Figure 2f P-values were calculated using a two-sample Student’s t-test on slopes calculated by the linear least squares regression model. Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple t-test comparisons. A statistically significant difference was concluded when P < 0.05, <0.02 or P < 0.01 as indicated by * in the figures and as reported in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all lab members for fruitful discussion, especially J. Daniel for critical input on the manuscript. Work at The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research (CPR) is funded in part by a generous donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant number NNF14CC0001). The proteomics technology developments applied was part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 686547 (J.V.O.). The work was supported by the 7th framework programs of the European Union (201648-PROSPECTS, 262067-PRIME-XS and 290257-UPStream to J.V.O.); the Danish Research Council (research career program FSS Sapere Aude to J.V.O.); the Junior Group Leader Fellowship by the Lundbeck Foundation (B.B.); the Marie Curie IEF and EMBO Long-Term post-doctoral fellowships (C.F.).

Footnotes

Author contribution

M.P. performed the experiments shown in Fig. 2e-f, 3e-f, 5f, 6b, 6h, and Supplementary Fig. 7 a, b, g, h,. K.T.G.R. contributed to data analysis shown in Figures 2c, 3a-d, 4, 6a, 6c, 7a and Supplementary Fig. 2, 3, 4. J.O.S. performed the proteome experiment described in Figures 2c, 7a and Supplementary Fig. 2a. G.C. prepared the RAB7 mutants construct. A.K.P. performed the experiments shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, 6a-b, and Fig. 2g. G.K. contributed to quantification of immunofluorescence experiments. B.B edited the manuscript and discussed the results. C.F. generated and analyzed the data shown in remaining figures. C.F. and J.V.O. designed the experiments, critically evaluated the results, supervised M.P. and J.O.S., and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kholodenko BN. Untangling the signalling wires. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:247–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb0307-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Y, et al. Temporal regulation of EGF signalling networks by the scaffold protein Shc1. Nature. 2013;499:166–71. doi: 10.1038/nature12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purvis JE, Lahav G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell. 2013;152:945–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sousa LP, et al. Suppression of EGFR endocytosis by dynamin depletion reveals that EGFR signaling occurs primarily at the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200164109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira AV, Lamaze C, Schmid SL. Control of EGF receptor signaling by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1996;274:2086–9. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villasenor R, Nonaka H, Del Conte-Zerial P, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M. Regulation of EGFR signal transduction by analogue-to-digital conversion in endosomes. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Donatis A, et al. Proliferation versus migration in platelet-derived growth factor signaling: the key role of endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19948–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francavilla C, et al. The binding of NCAM to FGFR1 induces a specific cellular response mediated by receptor trafficking. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1101–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francavilla C, et al. Functional proteomics defines the molecular switch underlying FGF receptor trafficking and cellular outputs. Mol Cell. 2013;51:707–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parachoniak CA, Luo Y, Abella JV, Keen JH, Park M. GGA3 functions as a switch to promote Met receptor recycling, essential for sustained ERK and cell migration. Dev Cell. 2011;20:751–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigismund S, et al. Endocytosis and signaling: cell logistics shape the eukaryotic cell plan. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:273–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellman I, Yarden Y. Endocytosis and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a016949. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:296–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riese DJ., 2nd Ligand-based receptor tyrosine kinase partial agonists: New paradigm for cancer drug discovery? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6:185–193. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.547468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceresa BP, Peterson JL. Cell and molecular biology of epidermal growth factor receptor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2014;313:145–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800177-6.00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roepstorff K, et al. Differential effects of EGFR ligands on endocytic sorting of the receptor. Traffic. 2009;10:1115–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collinet C, et al. Systems survey of endocytosis by multiparametric image analysis. Nature. 2010;464:243–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberali P, Snijder B, Pelkmans L. A hierarchical map of regulatory genetic interactions in membrane trafficking. Cell. 2014;157:1473–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altelaar AF, Munoz J, Heck AJ. Next-generation proteomics: towards an integrative view of proteome dynamics. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:35–48. doi: 10.1038/nrg3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosp F, et al. Quantitative interaction proteomics of neurodegenerative disease proteins. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larance M, Lamond AI. Multidimensional proteomics for cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:269–80. doi: 10.1038/nrm3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen JV, Mann M. Status of large-scale analysis of post-translational modifications by mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:3444–52. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.034181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen LK, Kolch W, Kholodenko BN. When ubiquitination meets phosphorylation: a systems biology perspective of EGFR/MAPK signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Argenzio E, et al. Proteomic snapshot of the EGF-induced ubiquitin network. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:462. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, et al. Perturbation of the mutated EGFR interactome identifies vulnerabilities and resistance mechanisms. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:705. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsen JV, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omerovic J, Hammond DE, Prior IA, Clague MJ. Global snapshot of the influence of endocytosis upon EGF receptor signaling output. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5157–66. doi: 10.1021/pr3007304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigismund S, et al. Clathrin-independent endocytosis of ubiquitinated cargos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2760–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409817102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigismund S, et al. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh B, Coffey RJ. From wavy hair to naked proteins: the role of transforming growth factor alpha in health and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;28:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satpathy S, et al. Systems-wide analysis of BCR signalosomes and downstream phosphorylation and ubiquitylation. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:810. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagaraj N, et al. Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:548. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorkin A, Goh LK. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of ErbBs. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:683–96. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caswell PT, et al. Rab-coupling protein coordinates recycling of alpha5beta1 integrin and EGFR1 to promote cell migration in 3D microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:143–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigbolt KT, et al. System-wide temporal characterization of the proteome and phosphoproteome of human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci Signal. 2011;4:rs3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alpi AF, Pace PE, Babu MM, Patel KJ. Mechanistic insight into site-restricted monoubiquitination of FANCD2 by Ube2t, FANCL, and FANCI. Mol Cell. 2008;32:767–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takayama S, et al. BAG-1 modulates the chaperone activity of Hsp70/Hsc70. EMBO J. 1997;16:4887–96. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol Cell. 2007;28:730–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ceresa BP, Bahr SJ. RabAB7 activity affects epidermal growth factor:epidermal growth factor receptor degradation by regulating endocytic trafficking from the late endosome. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1099–106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Chen L, Wang S, Wang T. RAB7: roles in membrane trafficking and disease. Biosci Rep. 2009;29:193–209. doi: 10.1042/BSR20090032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang F, Kirkpatrick D, Jiang X, Gygi S, Sorkin A. Differential regulation of EGF receptor internalization and degradation by multiubiquitination within the kinase domain. Mol Cell. 2006;21:737–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sigismund S, et al. Threshold-controlled ubiquitination of the EGFR directs receptor fate. EMBO J. 2013;32:2140–57. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen JV, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meijer IM, van Rotterdam W, van Zoelen EJ, van Leeuwen JE. Recycling of EGFR and ErbB2 is associated with impaired Hrs tyrosine phosphorylation and decreased deubiquitination by AMSH. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1981–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mertins P, et al. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat Methods. 2013;10:634–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma K, et al. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1583–94. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Ferguson KM. The EGFR family: not so prototypical receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a020768. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodman P. ESCRT proteins, endosome organization and mitogenic receptor down-regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:146–50. doi: 10.1042/BST0370146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komander D, Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:203–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaeuble K, et al. Ubiquitylation of the chemokine receptor CCR7 enables efficient receptor recycling and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4463–74. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, et al. RCP is a human breast cancer-promoting gene with Ras-activating function. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2171–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI37622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Behar M, Barken D, Werner SL, Hoffmann A. The dynamics of signaling as a pharmacological target. Cell. 2013;155:448–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moraga I, et al. Tuning Cytokine Receptor Signaling by Re-orienting Dimer Geometry with Surrogate Ligands. Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson KJ, Gilmore JL, Foley J, Lemmon MA, Riese DJ., 2nd Functional selectivity of EGF family peptide growth factors: implications for cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Topol EJ. Individualized medicine from prewomb to tomb. Cell. 2014;157:241–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vizcaino JA, et al. The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1063–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 57.Shvets E, Bitsikas V, Howard G, Hansen CG, Nichols BJ. Dynamic caveolae exclude bulk membrane proteins and are required for sorting of excess glycosphingolipids. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6867. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]