Abstract

PURPOSE

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a global impact, and Singapore has seen 33,000 confirmed cases. Patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers (HCWs) need to balance the challenges associated with COVID-19 while ensuring that cancer care is not compromised. This study aimed to evaluate the psychological effect of COVID-19 on these groups and the prevalence of burnout among HCWs.

METHODS

A cross-sectional survey of patients, caregivers, and HCWs at the National Cancer Centre Singapore was performed over 17 days during the lockdown. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Maslach Burnout Inventory were used to assess for anxiety and burnout, respectively. Self-reported fears related to COVID-19 were collected.

RESULTS

A total of 624 patients, 408 caregivers, and 421 HCWs participated in the study, with a response rate of 84%, 88%, and 92% respectively. Sixty-six percent of patients, 72.8% of caregivers, and 41.6% of HCWs reported a high level of fear from COVID-19. The top concern of patients was the wide community spread of COVID-19. Caregivers were primarily worried about patients dying alone. HCWs were most worried about the relatively mild symptoms of COVID-19. The prevalence of anxiety was 19.1%, 22.5%, and 14.0% for patients, caregivers, and HCWs, respectively. Patients who were nongraduates and married, and caregivers who were married were more anxious. The prevalence of burnout in HCWs was 43.5%, with more anxious and fearful HCWs reporting higher burnout rates.

CONCLUSION

Fears and anxiety related to COVID-19 are high. Burnout among HCWs is similar to rates reported prepandemic. An individualized approach to target the specific fears of each group will be crucial to maintain the well-being of these vulnerable groups and prevent burnout of HCWs.

INTRODUCTION

As of May 26, 2020, COVID-19 infected more than 5,000,000 individuals and resulted in more than 300,000 deaths occurring in at least 210 countries.1 In addition to grave public health repercussions, a consideration of the psychological effects of the pandemic is equally important. During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, its rapid nosocomial transmissions resulted in widespread fear among health care workers (HCWs).2 Examination of the mental health burden among HCWs during the SARS outbreak indicated that adverse emotional responses were common.3 The psychological effects of infectious disease outbreaks in the general population, infection survivors, and HCWs are well documented. However, literature about these psychological impacts on uninfected patient populations is scarce.4 Patients with cancer are a unique group of patients because they need to access health care regularly for life-sustaining cancer treatment. Delay in cancer treatment is detrimental to patients.5 Yet, patients with cancer are immunocompromised and may have poorer outcomes from COVID-19 should they get infected while seeking treatment.6 In view of these competing concerns, patients with cancer are forced to choose between seeking treatment and increasing the risk of contracting COVID-19 or postponing therapy and minimizing the risk of contracting COVID-19.7

CONTEXT

Key Objectives

The psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks in the uninfected patient population and their caregivers is not known. This study aimed to evaluate the psychological effects of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers (HCWs), and to evaluate the prevalence of burnout among HCWs.

Knowledge Generated

Sixty-six percent of patients, 72.8% of caregivers, and 41.6% of HCWs reported a high level of fear from COVID-19. The prevalence of anxiety was 19.1%, 22.5%, 14.0% for patients, caregivers, and HCWs, respectively. The prevalence of burnout in HCWs was 43.5%, with more anxious and fearful HCWs reporting higher burnout rates.

Relevance

An individualized approach that targets the specific fears and perceived risks of each group will be crucial to maintain the psychological well-being of these vulnerable groups and prevent burnout of HCWs.

The pandemic also presents another unique challenge to patients with cancer—the need to practice isolation to stem the spread of the virus while maintaining social connections to ensure psychological well-being.8 The diagnosis of cancer results in numerous psychological burdens for patients and their caregivers. Social support protects against psychological symptoms9 and is a protective factor against physical morbidity and mortality.10 Many patients with cancer fear dying alone, and the meaningful interpersonal relationships and physical presence of family members are essential to patients in their final hours.11 However, in this pandemic, a key policy to reduce the spread of COVID-19 is to encourage, and in many cases enforce, social distancing.12 Although the adverse effect of quarantine and social isolation on healthy individuals is well documented,13 little is known about how patients with cancer and their caregivers cope during social isolation.

To help patients and caregivers navigate through these challenges, oncology HCWs must deal with constant disruptions to cancer care and make ethically challenging decisions while managing their own fears of personal safety.14,15 This may lead to an increase in burnout rates.

This study aimed to better understand the psychological impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and HCWs. In addition, it aimed to assess the prevalence of burnout among oncology HCWs during this pandemic.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

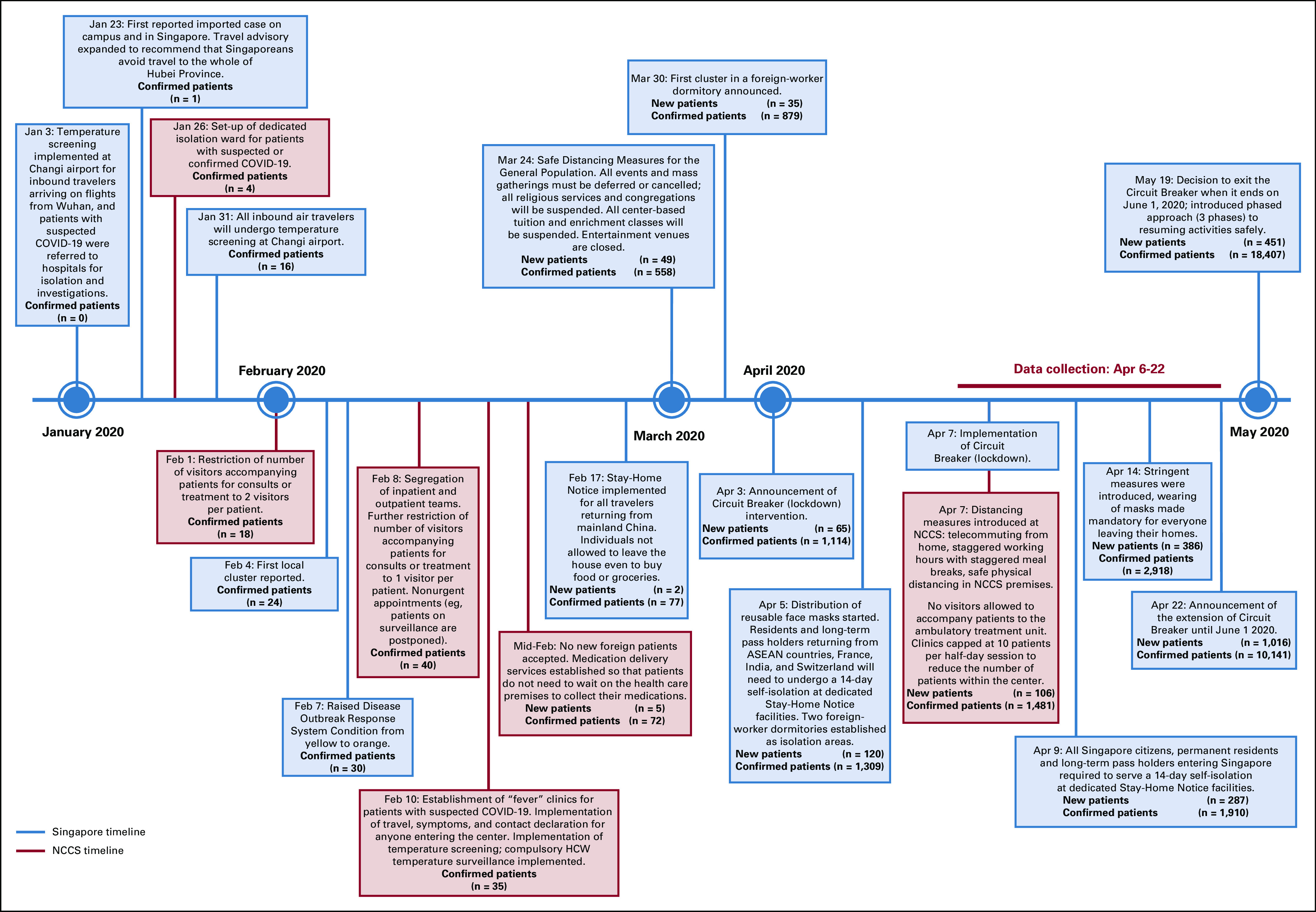

This was a cross-sectional study reported according to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. The study was conducted in Singapore, a multiethnic country composed of 5,703,569 people, with 3,500,940 of these residents made up of Chinese (76.0%), Malay (15.0%), Asian-Indian (7,5%), and other (1.5%) inhabitants.16 The National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) is one of the two public cancer specialty centers in Singapore and sees approximately 60%-70% of all public patients with cancer. As of the last day of data collection (April 22, 2020), Singapore had 10,141 confirmed COVID-19 infections, and 12 deaths.17 To manage the pandemic, the Singapore Government announced a lockdown on April 3 and instituted it on April 7, 202018 (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Timeline of events regarding the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore and National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS). ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations; HCW, health care worker.

Participants

Patients with cancer, caregivers, and HCWs from the NCCS were recruited to complete the questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were (1) English- or Chinese-speaking, (2) age ≥ 21 years, (3) with cancer or caring for someone with cancer (patients and caregivers). Convenient sampling was conducted over 3 weeks, from April 6-22, 2020. Research assistants were assigned to all clinics and ambulatory treatment units, and they recruited participants by handing out questionnaires. HCWs could complete the questionnaire using the hard copy or the REDCap online platform. Because this study was performed during the lockdown, sample size was dictated by the maximal number of participants who could be recruited within 3 weeks.

Questionnaire Instruments

For all participants, demographic and socioeconomic status information was collected. For patients and caregivers, information about the patient’s cancer was collected. For HCWs, data were collected on the type of profession, whether the nature of work had changed because of COVID-19, and whether the job involved direct patient contact. The questionnaire was designed on the basis of measures used in previous epidemics to measure fears,19 anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7]),20 confidence in HCWs,21 and risk perceptions.22 In addition, items based on themes brought up during in-depth interviews with patients and caregivers were included, for example, cancer-specific concerns and condemnation (findings of interviews not reported).

The GAD-7 is a 7-item validated questionnaire used to screen for GAD; a score of ≥ 10 suggests a possible diagnosis of GAD.20 In addition, the questionnaire for HCWs included the same questions as well as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).23 The 22-item MBI is designed to measure the three domains of burnout: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and professional accomplishment. Participants were identified as experiencing burnout if they had EE ≥ 27 and/or DP ≥ 10.23,24

Data Analysis

Demographic and survey responses were examined using frequency and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. The 95% CIs for anxiety and burnout rates were estimated using the Clopper-Pearson method. Differences between the three participant groups were examined in bivariable analyses using χ2 tests. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between participant characteristics and anxiety/burnout/fears. Association of HCWs’ survey responses with the presence of burnout were assessed (controlled for the demographic variables). For questions related to fears, exploratory factor analysis was performed for the combined patient and caregiver dataset, and this showed a two-factor structure: general COVID-19 fears and COVID-19 effect on cancer fears. These two factors showed good internal consistency, with a Cronbach α of .92 and .93, respectively. The responses of questions from each factor were summed and divided by the number of questions to reflect the level of general COVID-19 fears and COVID-19 effects on cancer fears. For HCWs, questions under the factor general COVID-19 fears were analyzed in the same way (α = .92). Point estimates were reported with corresponding CIs, which were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Proportions of missing data were reported. There was no prespecified statistical analysis plan; however, an a priori hypothesis was specified at the time of questionnaire development. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.3.25

Ethics

The study was approved by the Singapore Health Services Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB: 2020/2155). Because no identifiable data were collected, CIRB waived the need for written consent. Informed verbal consent was obtained by all participants who were recruited in person, whereas consent was presumed when participants completed the survey on the REDCap online platform.

RESULTS

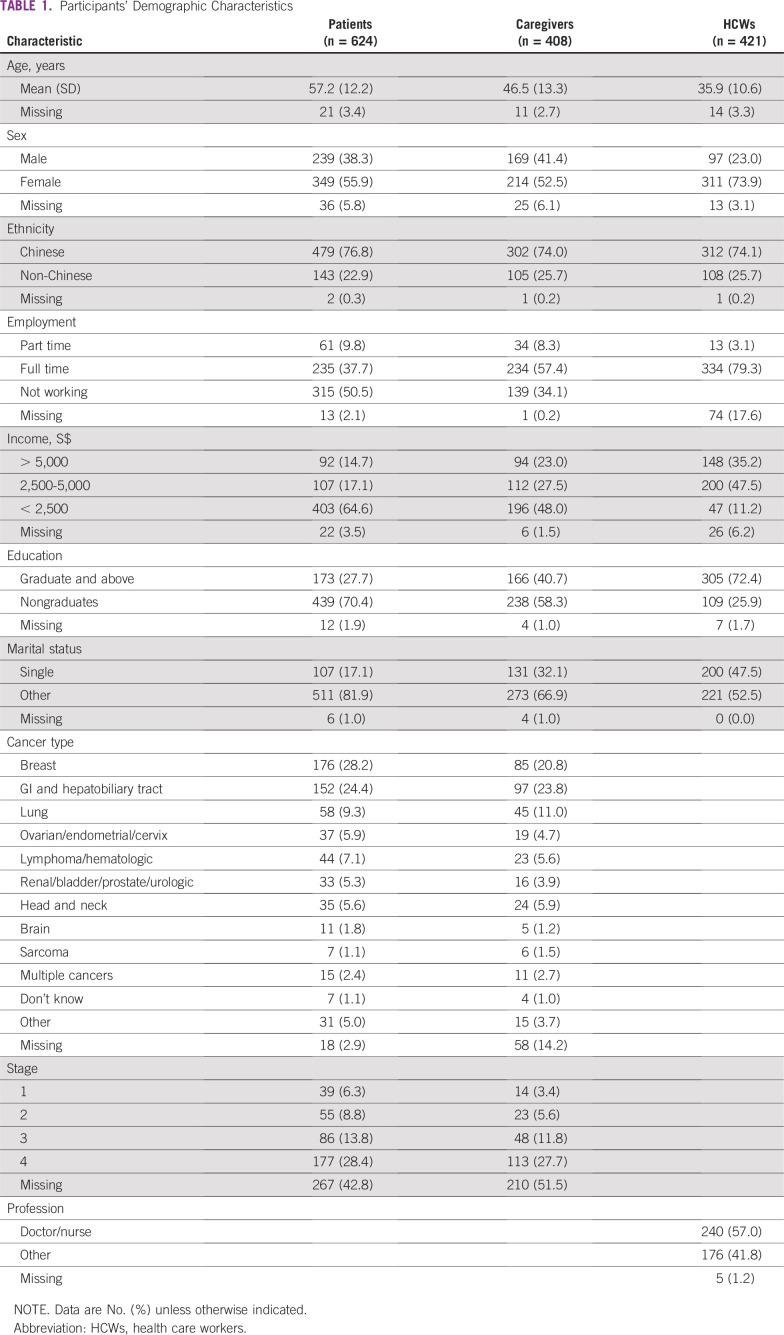

A total of 624 patients, 408 caregivers, and 421 HCWs participated in the study, with a response rate of 84%, 88%, 92%, respectively. Participants’ demographics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

Perceived Risk

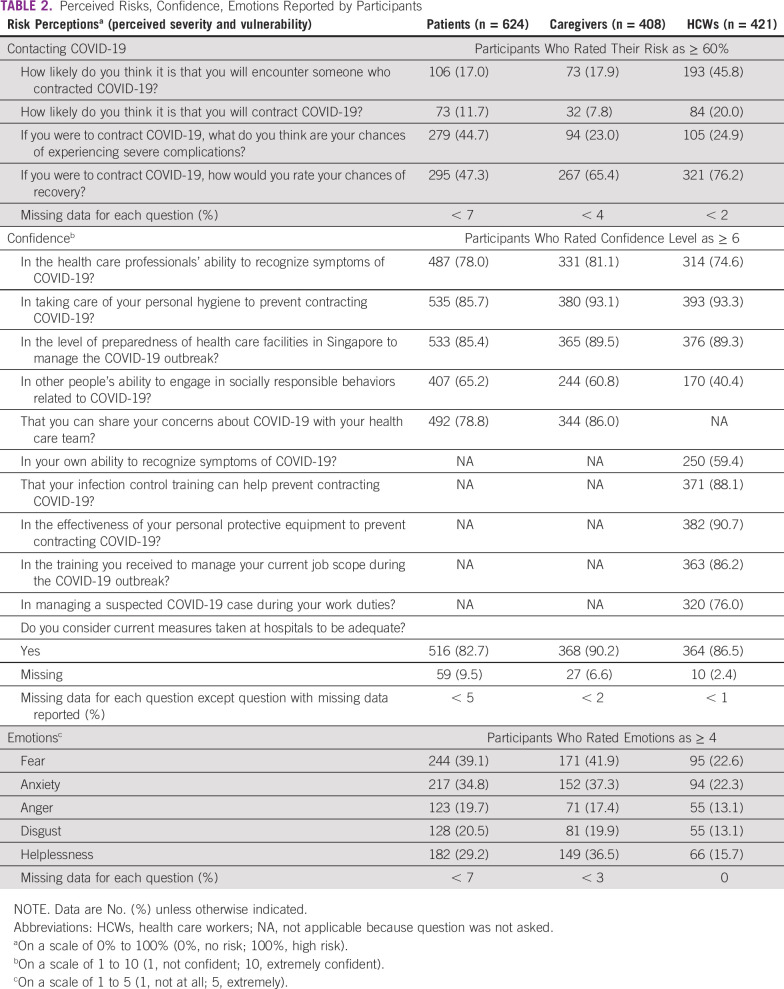

HCWs were more likely to respond affirmatively to the question, “How likely do you think it is that you will encounter someone who contracted COVID-19?” (HCWs, 45.8%; patients, 17.0%; caregivers, 17.9%; P < .001). HCWs reported a higher likelihood of actually contracting COVID-19 (HCWs, 20.0%; patients, 11.7%; caregivers, 7.8%; P < .001). However, patients reported a higher likelihood of experiencing severe complications as a result of COVID-19 infection (patients, 44.7%; caregivers, 23.0%; HCWs, 24.9%; P < .001) and a lower chance of recovery compared with caregivers and HCWs (patients, 47.3%; caregivers, 65.4%; HCWs, 76.2%; P < .001; Table 2)

TABLE 2.

Perceived Risks, Confidence, Emotions Reported by Participants

Anxiety and Other Negative Emotions

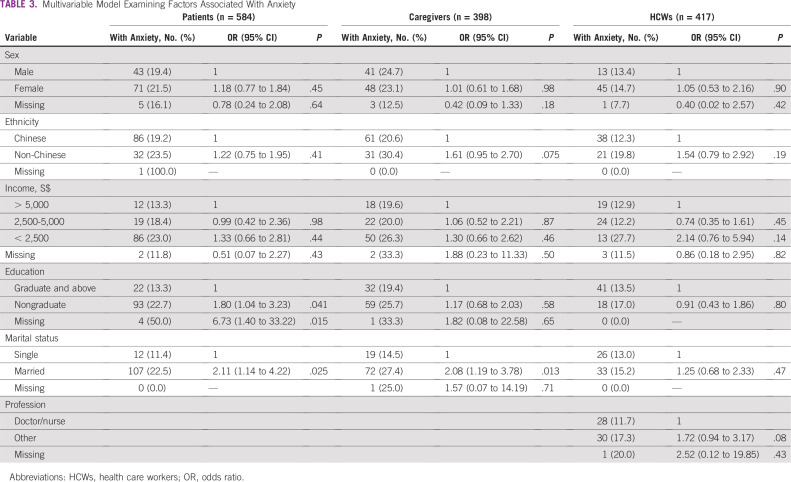

The prevalence of anxiety (ie, GAD-7 ≥ 10) was 19.1%, 22.5%, and 14.0% for patients, caregivers, and HCWs, respectively (P = .004). In the multivariable analysis, the prevalence of anxiety was significantly higher in patients with education lower than tertiary level compared with those with graduate education (odds ratio [OR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.04 to 3.15; P = .04) and higher in patients who were married (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.14 to 4.22; P = .025). Caregivers who were married were found to be more anxious in the multivariable analysis (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.19 to 3.78; P = .013). None of the parameters were associated with anxiety in the models for HCWs (Table 3). The top emotion reported was fear, followed by anxiety, among patients, caregivers, and HCWs (Table 2).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Model Examining Factors Associated With Anxiety

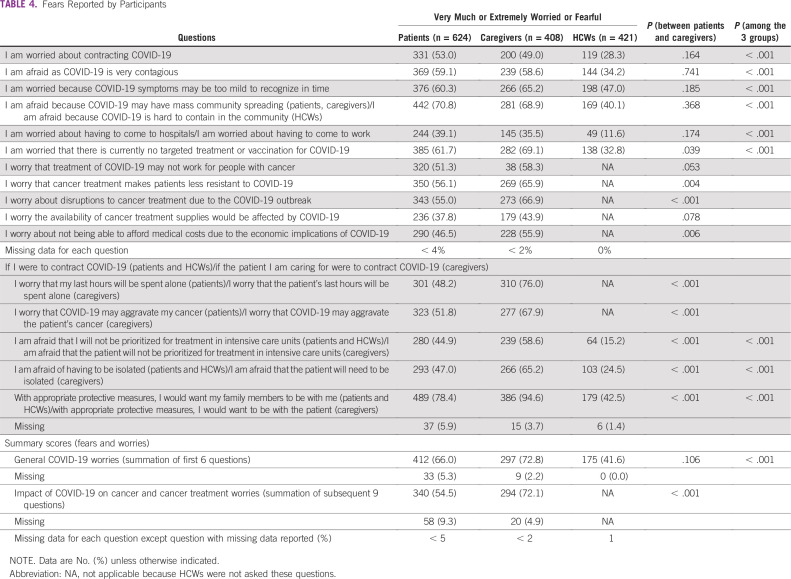

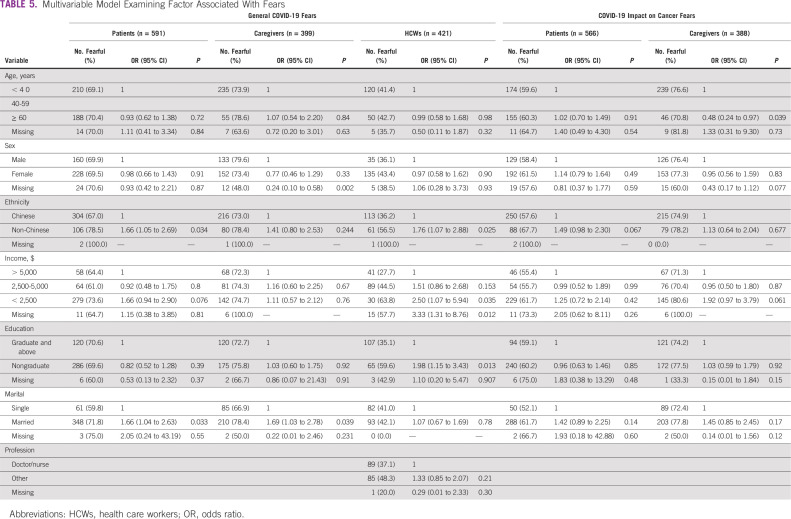

Fears

HCWs were less fearful of COVID-19 compared with patients and caregivers, with 66.0% of patients and 72.8% of caregivers feeling very much or extremely fearful about COVID-19 compared with 41.6% of HCWs (P < .001). Caregivers were more fearful than patients with respect to how COVID-19 may affect the patients’ cancer treatment (72.1% v 54.5%; P < .001; Table 4). On multivariable analysis, HCWs who were non-Chinese (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.07 to 2.88; P = .025), with a monthly income of < S$2,500 (OR, 2.50, 95% CI, 1.07 to 5.94; P = .035 compared with > S$5,000), and who were nongraduates (OR, 1.98, 95% CI, 1.15 to 3.43; P = .013) were more likely to be fearful about COVID-19. Patients who were non-Chinese (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.05 to 2.69; P = .034) and married (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.63; P = .033) and caregivers who were married (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.03 to 2.78; P = .039) had higher general COVID-19 fears. Older caregivers were less likely to have fears regarding the effect of COVID-19 on cancer management (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.97; P = .039; Table 5). The top COVID-19 fears of patients, caregivers, and HCWs were “COVID-19 may have mass community spread,” “I am afraid that the patient’s last hours will be spent alone,” and “COVID-19 symptoms may be too mild to recognize in time,” respectively. Almost all caregivers (94.6%) answered yes to the question, “With appropriate protective measures, I would want to be with the patient (if the patient has COVID-19)” compared with 78.4% of patients who reported yes to a similarly phrased question, “With appropriate protective measures, I would want my family members to be with me”(Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Fears Reported by Participants

TABLE 5.

Multivariable Model Examining Factor Associated With Fears

Confidence

Patients and caregivers reported high confidence in HCWs’ ability to recognize the symptoms of COVID-19, with 78.0% of patients and 81.1% of caregivers responding positively when asked, “How confident are you in HCWs’ ability to recognize symptoms of COVID-19?” However, only 74.6% of HCWs were confident when asked this question with reference to other HCWs’ ability, and only 59.4% felt confident in their own ability to recognize the symptoms of COVID-19. All groups reported high confidence in the level of preparedness of health care facilities in Singapore to manage the COVID-19 outbreak (patients, 85.4%; caregivers, 89.5%; and HCWs, 89.3%). These responses are summarized in Table 2.

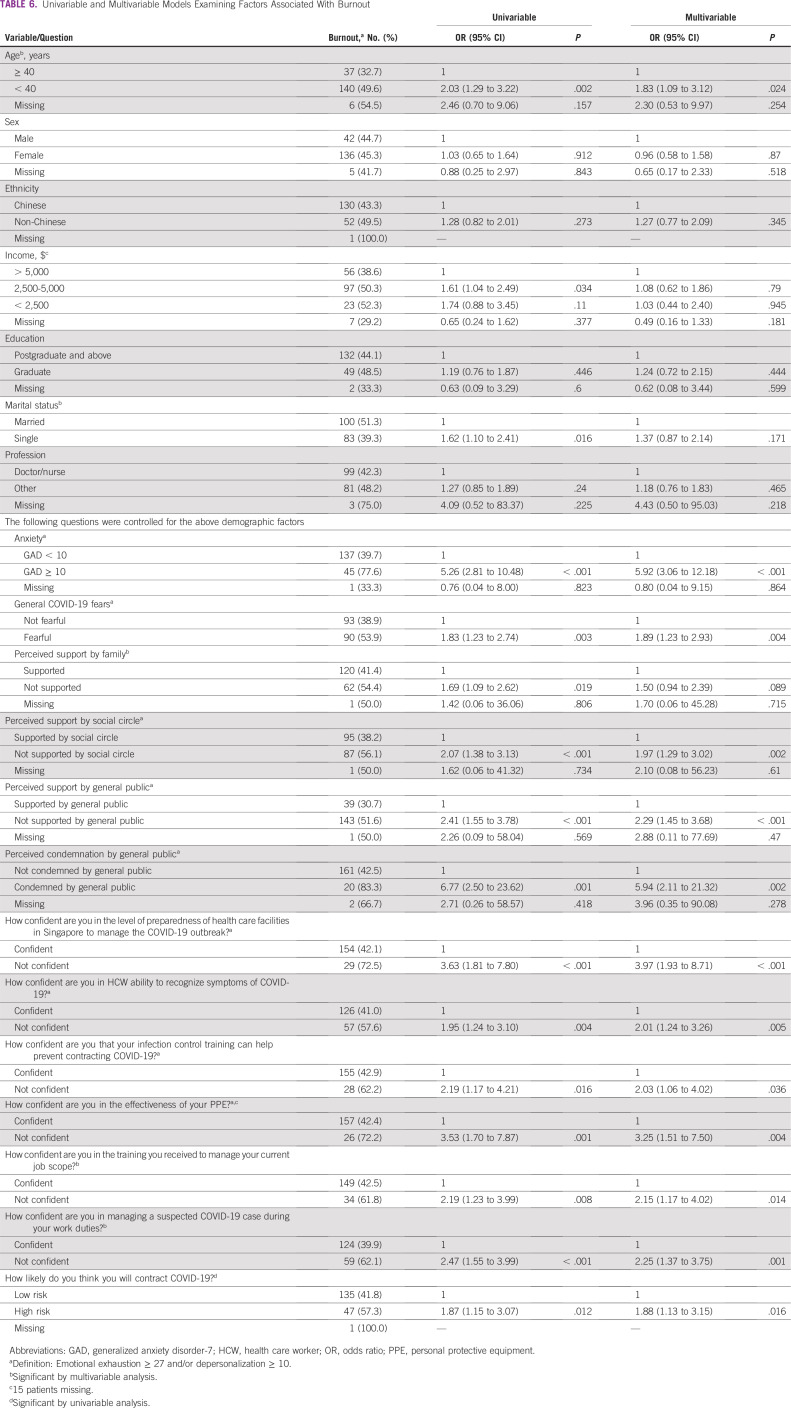

Burnout in HCWs

The prevalence of burnout in HCWs was 43.5%. In the univariable analysis, those who were more likely to experience burnout were: HCWs ≥ 40 years of age with a monthly income of S$2,500-S$5,000 (compared with > S$5,000), who were single, were anxious, were fearful, perceived support from family, perceived a lack of support from their social circle, perceived a lack of support from the general public, perceived condemnation by the general public, perceived a risk of contracting COVID-19, and had low confidence in the level of preparedness of health care facilities. In the multivariable analysis, younger HCWs (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.09 to 3.12; P = .024) and HCWs who were anxious (OR, 5.92; 95% CI, 3.06 to 12.18; P < .1) and fearful (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.23 to 2.93; P = .004) were more likely to experience burnout. In addition, HCWs with perceived lack of support from their social circle, perceived lack of support, perceived condemnation by the public, high perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and low confidence in the level of preparedness of health care facilities were associated with higher rates of burnout in the multivariable analysis (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Univariable and Multivariable Models Examining Factors Associated With Burnout

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional survey of patients with cancer, their caregivers, and HCWs, we found elevated levels of perceived risk, anxiety, and fears. Despite this, confidence in HCWs and health care facilities was high, and burnout among HCWs was not increased from pre-COVID-19 rates.

Perceived risk of encountering patients with COVID-19 and of contracting COVID-19 were high in all groups but lower among patients and caregivers compared with HCWs. Many patients with cancer and their caregivers already took precautionary measures even before the COVID-19 outbreak because of the immunocompromised status of the patients. This may contribute to the relatively lower perceived risk as well, compared with the population of patients with chronic disease described by Wolf et al.26 Patients, however, felt that they had a higher risk of having severe complications if they contracted COVID-19 and lower chances of recovery, again reflecting their understanding of their immunocompromised state.

Given the high levels of perceived risk, it is not surprising that the prevalence of anxiety among patients, caregivers, and HCWs is high. This is concerning because it is many times higher than the prevalence of GAD in Singapore, which was at 1.6% in 2016.27 This epidemiologic study used the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview,28 an established instrument used in psychiatric epidemiologic studies. Despite the differences in instruments used, which precludes direct comparison, juxtaposing our results with the results by Chang et al27 provides an approximation of the impact of COVID-19 on anxiety levels in our participants. Lai et al 29 found that 12.3% of HCWs treating patients with COVID-19 in China were at least moderately anxious (GAD-7 ≥ 10). In another study of Italian HCWs, 19.8% of participants reported high levels of anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 15) compared with 4.8% in our study. Thomaier et al30 found that 62.0% of oncology HCWs in the United States were anxious, with perceptions of inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and practicing in a state with more patients with COVID-19 increasing anxiousness. The prevalence rates of anxiety among our HCWs were similar to levels found in China and lower than those found in the Western countries. There may be a possible role of ethnicity, given that both Singapore and China have a predominance of Chinese HCWs. Our study also showed that non-Chinese HCWs were more likely to report higher COVID-19 fears; however, this was not observed for burnout or anxiety. In addition, the lower rates of anxiety among HCWs in Singapore and China could be a result of the adequate supply of PPE provided to HCWs and the effective public health interventions implemented by these countries to manage the pandemics (Singapore and China have a lower number of confirmed patients with COVID-19 compared with the United States and Italy31). Furthermore, Singapore has a particularly low COVID-19 death rate of 0.05% (total deaths of 27 as of August 6, 2020), further reassuring the population.31

In addition to anxiety, participants also reported high levels of fear. To address these negative emotions, it will be helpful to understand the underlying reasons for fears. The top concern by caregivers was that their loved ones would die alone should they contract COVID-19, and many would sacrifice their own safety and be willing to be with their loved ones in these moments, with appropriate protective measures. Although there is a need to limit visitors to patients with COVID-19 to minimize the risk of transmission, this concern must be balanced against the distress caused by separation of caregivers from patients in such situations. As reports of asymptomatic carriers who are infectious are emerging,32 it is no surprise that HCWs’ top concern is that of COVID-19 symptoms being too mild to be recognized in time. This results in a lack of confidence in their own ability and other HCWs’ ability to diagnose COVID-19.

Despite the high level of perceived risks, anxiety, and fears, confidence in HCWs and facilities remained high at NCCS. This was achieved at two levels: institutional and national. At the institutional level, strict temperature screening and travel/contact declarations were required of all patients, caregivers, and HCWs as soon as the first few patients with COVID-19 were reported in Singapore (Fig 1). Adequate PPE was issued to all HCWs and refresher training provided. On the national level, constant updates through mobile phones, the Internet, and traditional media were provided. In addition, border restrictions and contact tracing were used to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the community. This finding is in contrast with the low confidence that patients in one US study had of their federal government response,26 and emphasizes the important role that HCWs and authorities play in allaying the fears that many patients and caregivers have.

Surprisingly, despite the immense pressure at the frontline, we found a low rate of burnout: 43.5% of all HCWs. This is lower than rates reported among US physicians (54.4%)33 and Chinese oncologists (51.0%) prepandemic.34 Younger HCWs, those with a lower income, and single HCWs were more likely to report burnout on univariable analysis. However, on multivariable analysis, only younger HCWs were associated with burnout. It is likely that those who are younger have a lower income and are also single. Previous studies have found that younger HCWs were more likely to experience greater psychological effects.29,30,35

Although it is reassuring that burnout rates are not elevated compared with prepandemic periods, they may possibly increase as the pandemic drags on. We found multiple modifiable factors associated with burnout that may be amendable to interventions. Perceived support from friends and the public was associated with a lower rate of burnout; perceived condemnation from the public was associated with a higher rate of burnout. There were multiple reports of HCWs being ostracized by family and the public in Singapore at the onset of the pandemic.36 However, the authorities were quick to speak out against this and led by example to appreciate HCWs. There has since been an outpouring of support from the public.37 This highlights the importance of public education to bolster support for HCWs to combat burnout. HCWs who are anxious and more fearful are at increased risk of burnout. With the prevalence of anxiety many times above the prepandemic rates, it is important to monitor the psychological health of this group of HCWs through psychological wellness and peer-support programs. Policies should be targeted at alleviating fears of HCWs by instituting strict gatekeeping policies to segregate patients at highest risk of COVID-19 from those with lower risk and ensuring adequate supplies of effective PPE. If insufficient attention is paid to supporting HCWs, we will lose our most prized resource in this pandemic.

This study has limitations. First, this study was conducted in a single institution; findings may have limited generalizability. However, we believe that the experiences faced by the study participants may reflect the experiences faced by patients with other chronic diseases that require regular visits to a health care facility. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study only allows for understanding current emotions, fears, and risk perceptions. Because the pandemic has evolved rapidly since the publication of these data, we were not able to study how those developments may have affected our study population. One of the strengths of our study is the large sample size, which allowed for a diverse population. In addition, with more studies reporting the negative impact of COVID-19 on cancer treatment (eg, delayed diagnosis and treatment),38 this study gives key insights into the psychological effect of the pandemic on patients, caregivers, and HCWs that can help shape policies at the institutional and national levels. This study was completed within 17 days during the most acute period in Singapore (during the lockdown) and allowed for an accurate depiction of the impact of these measures on the psychological well-being of our study population.

Fears, perceived risk, and anxiety among patients, caregivers, and HCWs were significantly elevated as a result of the pandemic. Reassuringly, confidence in health care facilities remained high, and burnout rates among HCWs were similar to rates previously reported. An individualized approach to target the specific fears and perceived risk of each group will be crucial to maintain the psychological well-being of these vulnerable groups and prevent burnout of HCWs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank all patients, caregivers, and health care workers for participating in the study. We thank Shao Tzu Li for her help in translating the questionnaires.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore under its National Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Award (NMRC/CSA-INV/0017/2017) and administered by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council. In addition, this research is supported by the National Cancer Centre Cancer Fund.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kennedy Yao Yi Ng, Nur Diana Binte Ishak, Zack Zhong Sheng Goh, Zi Yang Chua, Jace Ming Xuan Chia, Rebecca Dent, Konstadina Griva, Joanne Ngeow

Financial support: Joanne Ngeow

Administrative support: Kennedy Yao Yi Ng, Jacklyn Kah Yeen Mok, Joanne Si Ying Lo, Konstadina Griva, Joanne Ngeow

Provision of study materials or patients: Kennedy Yao Yi Ng, Than Shwe, Joanne Ngeow

Collection and assembly of data: Kennedy Yao Yi Ng, Nur Diana Binte Ishak, Zi Yang Chua, Ee Ling Chew, Jacklyn Kah Yeen Mok, Shen Si Leong, Joanne Si Ying Lo, Zoe Li Ting Ang, Chanel Wei Jie Lam, Rebecca Dent, Jeffrey Tuan, Soon Thye Lim, Joanne Ngeow

Data analysis and interpretation: Kennedy Yao Yi Ng, Siqin Zhou, Sze Huey Tan, Nur Diana Binte Ishak, Zack Zhong Sheng Goh, Zi Yang Chua, Jace Ming Xuan Chia, Jo Lene Leow, Jin Wei Kwek, Rebecca Dent, William Ying Khee Hwang, Konstadina Griva, Joanne Ngeow

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Rebecca Dent

Honoraria: Genentech, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, MSD

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Pfizer, Merck, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Pfizer, Amgen, Merck

William Ying Khee Hwang

Honoraria: Johnson & Johnson, Novartis

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: PCT/SG2017/050409; Title: Substituted azole derivatives for generation, proliferation, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Abbvie

Joanne Ngeow

Honoraria: AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic, Worldometer, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2.Chang H-J, Huang N, Lee C-H, et al. The impact of the SARS epidemic on the utilization of medical services: SARS and the fear of SARS. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:562–564. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu TH, Chou YJ, Liou CS. Impact of SARS on healthcare utilization by disease categories: Implications for delivery of healthcare services. Health Policy. 2007;83:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(suppl 1):S92–S107. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5. Burki TK: Cancer guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol 21:P629-P630, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossage L. Coronavirus means difficult, life-changing decisions for me and my cancer patients. The Guardian; United Kingdom: 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/19/cancer-patients-coronavirus-outbreak-difficult-decisions [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SK, Herndon JE, Lyerly HK, et al. Correlates of quality of life-related outcomes in breast cancer patients participating in the Pathfinders pilot study. Psychooncology. 2011;20:559–564. doi: 10.1002/pon.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;75:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Authers DM: A sacred walk: Dispelling the fear of death and caring for the dying. Tampa, FL, A & A Publishing, 2008.

- 12. World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

- 13.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortiula F, Pettke A, Bartoletti M, et al. Managing COVID-19 in the oncology clinic and avoiding the distraction effect. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:553–555. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008. Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, et al: A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:e60-e65, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singapore Department of Statistics: Population Trends 2019. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/population/population2019.pdf.

- 17. Ministry of Health Singapore: 57 more cases discharged, 1,016 new cases of COVID-19 infection confirmed. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/57-more-cases-discharged-1-016-new-cases-of-covid-19-infection-confirmed.

- 18.Ministry of Health Singapore: Circuit breaker to minimise further spread of COVID-19 . Singapore. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman GB, Coups EJ. Emotions and preventive health behavior: Worry, regret, and influenza vaccination. Health Psychol. 2006;25:82–90. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung GM, Quah S, Ho LM, et al. A tale of two cities: Community psychobehavioral surveillance and related impact on outbreak control in Hong Kong and Singapore during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:1033–1041. doi: 10.1086/502340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai G, Suzuki T. Risk perception in Northeast Asia. Environ Monit Assess. 2009;157:151–167. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0524-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, et al. On the clinical validity of the Maslach burnout inventory and the burnout measure. Psychol Health. 2001;16:565–582. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maslach CM, Jackson SE, Leiter MP: Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Foundation: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- 26.Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. outbreak: A cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:100–109. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang S, Abdin E, Shafie S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of generalized anxiety disorder in Singapore: Results from the second Singapore Mental Health Study. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;66:102106. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc. 2009;18:23–33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242767. Thomaier L, Teoh D, Jewett P, et al: Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: Fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.11.20128702v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Worldometer 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus

- 32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, et al: Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med 382:2081-2090, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al: Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 90:1600-1613, 2015 [Erratum: Mayo Clin Proc 91:276, 2016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma S, Huang Y, Yang Y, et al. Prevalence of burnout and career satisfaction among oncologists in China: A national survey. Oncologist. 2019;24:e480–e489. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loh M. Nurses in S’pore wary of being ostracised by public, even as work takes its toll during coronavirus outbreak, Today. Singapore Press Holdings; Singapore: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim J. Covid-19 outbreak: Government to put up fund, online site for public to support healthcare workers, the vulnerable, Today. Singapore Press Holdings; Singapore: 2020. https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/covid-19-wuhan-coronavirus-outbreak-government-put-fund-online-site-public-support-healthcare-workers [Google Scholar]

- 38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5. Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al: Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol 21:750-751, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]