Abstract

We present the case of a 29-year-old woman who initially presented to her GP with a short history of non-pruritic annular skin lesions with central clearing. A month later, she developed signs and symptoms of bone marrow failure with bruising, epistaxis and fatigue. After urgent review of a blood film, she was diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML), which is a haematological emergency. Treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was commenced immediately and she was subsequently treated with arsenic trioxide (ATO). The annular rash was subsequently diagnosed as paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum (PEACE), which resolved with treatment. This case demonstrates the importance of the urgent diagnosis of APML and highlights PEACE as a rash that clinicians should be aware of, as it can be the initial manifestation of a number of both haematological and non-haematological malignancies.

Keywords: haematology (incl blood transfusion), dermatology, haematology (drugs and medicines)

Background

Acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML) is an uncommon subtype of acute myeloid leucaemia (AML) that is uniformly fatal without urgent treatment due to the accumulation of malignant promyelocytes, which trigger life-threatening disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). As a result, haemorrhage remains a major cause of early death in this patient cohort and as a result classifies suspected APML as a haematological emergency. It is therefore vital for clinicians to be aware of how APML can present.

As with other malignancies, APML can in rare instances present with a paraneoplastic rash. This case report describes a case of APML where the initial presenting symptom was a rash known as paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum (PEACE). Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a reactive erythema characterised by annular erythematous lesions. When associated with malignancy, it is referred to as PEACE. In some cases, the rash precedes the detection of the malignancy. Therefore, identification of the rash may unveil a previously undetected malignancy.1

Once the diagnosis of APML is suspected, the aim is to start urgent oral all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and correct coagulopathy before starting definitive, curative treatment. Although APML is initially life threatening, this disorder is an example of how advances in the understanding of APML pathophysiology has led to dramatic improvements in survival over the last 40 years, meaning that APML is now a highly curable subtype of AML.2

Case presentation

The patient was a previously fit and well 29-year-old Spanish woman, who presented to her general practitioner (GP) with a 2-week history of new bruising and intermittent epistaxis. There was no history of trauma or a known bleeding disorder. She denied any other sources of bleeding, did not report weight loss, night sweats or recurrent infections but had been more fatigued over the preceding few weeks.

She had a previous medical history of chronic plaque psoriasis treated with topical treatments intermittently since her teens. She had presented to her GP around a month earlier with new annular skin lesions which were not pruritic and not typical of psoriasis. The rash had not improved with a trial of topical emollients and coal tar and she was awaiting a dermatology outpatient appointment. Her only medications were topical treatments and she had never received any systemic immunosuppressive therapy for her psoriasis. She had no known allergies and no relevant family history. There was no history of alcohol excess, recreational drug use and she was a non-smoker. She was a student studying English, had lived in the UK for 6 years and had two young children at home who were both well. Systems’ review and recent travel history were unremarkable.

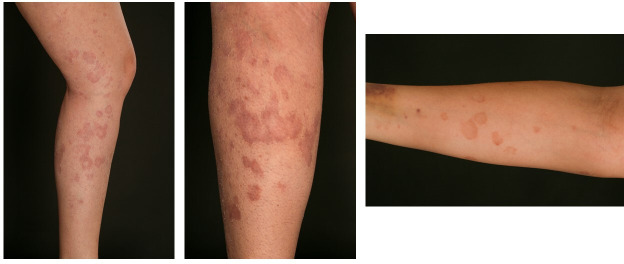

Examination on admission revealed an annular erythematous rash with central clearing and desquamation (figure 1). This affected the trunk, upper and lower limbs bilaterally with relative sparing of the extensor surfaces and the scalp. The lesions were asymmetrically distributed, non-uniform and in some areas had coalesced. There was no nail pitting. There were also several medium-sized superficial haematomas on the trunk and a petechial rash on the legs. The remaining systems’ examination was unremarkable with no hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1.

Images showing the patient’s rash on the arm and legs after presentation to hospital, consistent with paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum.

Due to the petechial rash, her GP referred her to the haematology department at her local hospital where she had urgent blood tests and was reviewed the same day.

Investigations

A full blood count showed: haemoglobin 95 g/L, mean cellular volume (MCV) 89 fL, platelet count 23×109/L, white cell count 0.48×109/L, neutrophil count 0.1×109/L. Renal profile and liver function tests were normal. Coagulation screen showed: prothrombin time (PT) 13 s (reference range (RR) 10–12 s), activate partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 29 s (RR 25–37 s), fibrinogen 1.3 g/L (RR 1.5–4.0 g/L), suggestive of early DIC. In light of the annular rash, an autoimmune screen was sent that was negative. Virology testing including HIV testing was negative and a pregnancy test was negative.

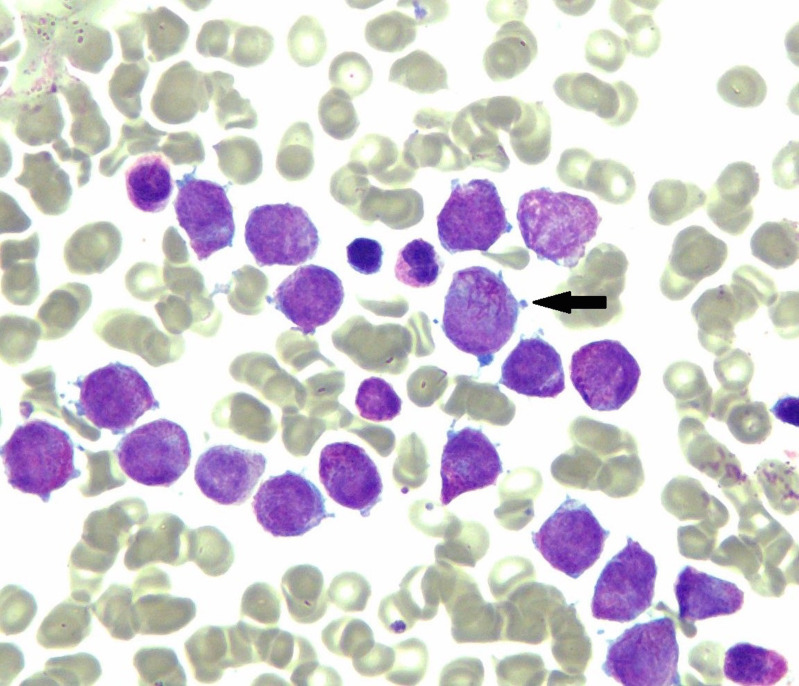

An urgent blood film confirmed pancytopenia. There were no schistocytes (red cell fragments) or any features of intravascular haemolysis. However, occasional abnormal bilobed promyelocytes with Auer rods were visible, which were highly suggestive of APML. A bone marrow aspirate showed effacement by highly granular promyelocytes with numerous Auer rods and faggot cells (a faggot is an old English term for a pile of sticks and describes the bundles of Auer rods seen in some malignant promyelocytes) (figure 2). There was granulocytic maturation arrest with minimal residual haematopoiesis.

Figure 2.

Bone marrow aspirate showing hypergranular promyelocytes with faggot cell (arrowed) showing multiple Auer rods (H&E staining; magnification ×100).

Flow cytometry revealed an abnormal population of cells with an immunophenotype suggestive of APML. The diagnosis was confirmed using an urgent fluorescent in-situ hybridisation dual colour PML/RARA (promyelocytic leukaemia/retinoic acid receptor alpha) probe which identified the PML–RARA fusion gene in 94 out of the 100 cells analysed after 1-hour hybridisation. All 10 G-banded metaphases analysed showed a female karyotype with a translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17.

The trephine subsequently showed a packed marrow (100% cellularity) with normal haematopoiesis almost entirely replaced by a sheet of blasts, many with an irregular nuclear outline.

Differential diagnosis

The patient presented with bruising and was found to be thrombocytopenic, with a prolonged PT and low fibrinogen, indicating early DIC. DIC can be caused by sepsis, mucin-producing adenocarcinomas and amniotic fluid embolism amongst others but there were no clinical features to suggest any of these diagnoses.3

The pancytopenia suggested bone marrow failure. The history was not consistent with a drug, autoimmune or infective cause. Given the relatively acute history, differentials for this therefore included aplastic anaemia, bone marrow infiltration due to haematological causes such as acute leukaemia or stage IV lymphoma (i.e., with bone marrow involvement), non-haematological causes of marrow infiltration by a non-haematological malignancy or severe haematinic deficiency, for example, due to vitamin B1212 or folate deficiency (noting however the normal MCV).4 The patient was from Spain, but there were no features to suggest visceral leishmaniasis (which can be associated with travel to the Mediterranean littoral countries including Spain) or tuberculosis, as both can cause pancytopenia.

The provisional working diagnosis of the rash was tinea corporis and the patient was therefore started on an empirical course of topical clotrimazole 1% cream. After a week of treatment, this had not improved. The dermatology team subsequently reviewed the rash, describing it as arcuate and serpiginous (due to the lesions being arc shaped, forming incomplete annular lesions with a snake-like appearance). This rash was described by the dermatology team as characteristic of PEACE since the lesions had central clearing and raised erythematous borders with a trailing scale.1 This was therefore not characteristic of tinea corporis which has a leading border of scale.5 This affected the trunk, upper and lower limbs bilaterally, and so the diagnosis was confirmed clinically. Differential diagnoses for this rash were tinea corporis, psoriasiform lesions, discoid lupus erythematosus, erythema gyratum, erythema chronicum migrans and erythema necroticans migrans.6 A skin biospy to investigate the annular rash was not performed as the underlysing APML diagnosis had been made, the rash was consistent clinically with PEACE and had not responded to a trial of topical anti-fungal treatment and there was a perceived risk of bleeding, particularly as she had already had prolonged low-volume bleeding from the bone marrow aspiration site.

Treatment

The patient was commenced immediately on oral ATRA. Once the diagnosis of APML was confirmed cytogenetically, she was given arsenic trioxide for low-risk APML (ie, total white cell count less than 10×109/L).7 During her admission, she received platelet transfusions, fresh frozen plasma and fibrinogen concentrate.

About 10 days after receiving treatment with ATRA and ATO, she developed weight gain with evidence of peripheral fluid overload, muscle pains and a rising white cell count, which peaked at 75×109/L (RR 3–10×109/L). This was diagnosed as differentiation syndrome, a well-recognised complication of treatment with ATRA. Its mechanism is not fully understood but is thought to be secondary to cytokine-mediated endothelial dysfunction causing capillary leak and microcirculatory occlusion.8 This was treated successfully with dexamethasone 10 mg two times per day which was subsequently weaned and she was discharged home 3 weeks after initial admission. The PEACE rash had mostly resolved by the time of discharge with only faint arcuate lesions remaining.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient remained well at home, but just over a month after discharge, she developed new unexplained left-sided tinnitus, headache and unsteadiness with normal clinical examination. CT head was unremarkable but an MRI brain was suspicious of cortical vein thrombosis. An MR venogram confirmed that the cortical veins overlying the left frontal and both parietal lobes did not show contrast filling and appeared hyperintense on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, consistent with thrombosis. There was normal opacification of the major intracranial (deep and dural) venous sinuses with no features of venous sinus thrombosis.

Due to APML-associated DIC, patients also have a risk of thrombosis in addition to high risk of bleeding initially. Although APML could have caused this, thrombosis is also listed as a rare side effect of ATRA.9 10 She was treated initially with treatment doses of subcutaneous enoxaparin, subsequently switched to apixaban.

Two months after the original APML diagnosis, she also developed numbness in her toes and her fingertips which subsequently spread proximally to involve her ankles and she developed a high-stepping gait with foot drop. Nerve conduction studies showed a mild-moderate length-dependent axonal generalised large-fibre peripheral neuropathy in keeping with a sensorimotor polyneuropathy. This was attributed to the arsenic.11 This was therefore stopped and she went on to receive a second course of consolidation with ATRA and mitoxantrone instead of arsenic.

The patient is now a year on after her initial diagnosis. Despite the treatment toxicities, she has had an excellent response to therapy with her most recent bone marrow aspiration and trephine demonstrating a cytogenetic and molecular remission. She remains on apixaban, continues to have stable peripheral sensorimotor symptoms and has not had any further treatment-related toxicities. The PEACE rash completely resolved after the first cycle of arsenic with no recurrence.

Discussion

While PEACE has been attributed to a number of malignancies in the literature including AML, to our knowledge, this is the first documented case report of APML presenting initially with PEACE. EAC is a reactive erythema characterised initially by papules that subsequently enlarge and clear centrally. These then form annular, non-pruritic, centrifugal, erythematous lesions up to 10 cm in diameter. When related to an underlying malignancy, it is known as PEACE. In a case series of PEACE, 62.5% of cases were due to lymphoproliferative disorders and 37.5% due to solid organ malignancies.1 The proposed mechanisms for this are either cytokine-related and/or tumour-associated antigens from the underlying malignancy triggering the dermatosis. Given that PEACE may precede the malignancy, timely recognition of the rash may help in diagnosing the underlying cancer.

APML makes up to 10% of the total cases of AML12 and is most commonly due to the reciprocal translocation of chromosomes 15 and 17 (t(15;17)) producing a PML–RARA fusion oncoprotein.13

Treatment of EAC is symptom-focused and topical corticosteroids can be used, however, treatment of PEACE is achieved by treating the underlying malignancy.1

Modern day treatment for APML is unique compared with other subtypes of AML as is it is not generally treated with conventional induction chemotherapy. It is imperative that ATRA, a vitamin A derivative that induces differentiation of the abnormal promyelocytes, is commenced immediately, even if the diagnosis is only suspected based on the clinical presentation and review of the blood film. Even with appropriate treatment, the highest mortality is within the first 30 days of diagnosis, commonly from the associated DIC. While patients with APML have a good long-term prognosis (complete remission rates of over 90%),14 this case demonstrates possible complications of the disease itself (cortical vein thrombosis as a thrombotic complication) and of the treatments (differentiation syndrome, sensorimotor polyneuropathy).

Patients with PEACE as a feature of their malignancy should also be monitored for recurrence of the rash, as recurrence of the malignant disease has been accompanied by recrudescence of the rash in a subset of patients.1

Learning points.

Acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML) requires rapid diagnosis by review of a blood film and transfer to a centre which can provide oral all-trans retinoic acid as soon as possible, even before the diagnosis is confirmed by cytogenetic and molecular methods.

Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum (PEACE) is a rare presentation of APML. However, given the association of PEACE with a number of cancers, improved awareness of this rash by primary and secondary care clinicians may prompt earlier diagnosis of a wide range of malignancies, both haematological and non-haematological.

Due to the effect of APML on coagulation, patients are at risk of catastrophic haemorrhage which is the most common cause of early mortality. Thrombosis should also be borne in mind particularly if patients develop unexplained neurological symptoms.

Footnotes

Twitter: @rachaelpocock

Contributors: CS was involved in patient care, acquisition of information and images, design of case report, literature search, drafting and final approval of manuscript. SM was involved in patient care, acquisition of information and images, design of case report, literature search, drafting and final approval of manuscript. RP was involved in patient care, acquisition of information, drafting and final approval of manuscript. AJW was involved in patient care, design of case report, drafting and final approval of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption: peace. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012;13:239–46. 10.2165/11596580-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tallman MS, Altman JK. How I treat acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2009;114:5126–35. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-216457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levi M, Scully M. How I treat disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood 2018;131:845–54. 10.1182/blood-2017-10-804096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinzierl EP, Arber DA. The differential diagnosis and bone marrow evaluation of new-onset pancytopenia. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:9–29. 10.1309/AJCP50AEEYGREWUZ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch D. Erythema annulare centrifugum, 2020. Available: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/erythema-annulare-centrifugum/

- 6.Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Wiley-Blackwell, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsenic trioxide for treating acute promyelocytic leukaemia, 2018. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta526/chapter/1-Recommendations

- 8.Sanz MA, Montesinos P. How we prevent and treat differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2014;123:2777–82. 10.1182/blood-2013-10-512640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breen KA, Grimwade D, Hunt BJ. The pathogenesis and management of the coagulopathy of acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2012;156:24–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KR, Subrayan V, Win MM, et al. Atra-Induced cerebral sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2014;38:87–9. 10.1007/s11239-013-0988-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trisenox SPC 2017, 2017. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/trisenox-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- 12.Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) statistics Cancer research UK (2019). Available: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/leukaemia-aml/incidence#heading-Zero

- 13.Grignani F, Ferrucci PF, Testa U, et al. The acute promyelocytic leukemia-specific PML-RAR alpha fusion protein inhibits differentiation and promotes survival of myeloid precursor cells. Cell 1993;74:423–31. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80044-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz MA, Lo-Coco F, Sanz, F Lo-Coco MA. Modern approaches to treating acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:495–503. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]