Abstract

A 65-year old man presented with 6-week history of bilateral knee pain and swelling, with difficulty mobilising. He had bilateral total knee arthroplasties in situ performed 5 years prior complicated by postoperative wound infection. Bilateral synovial fluid cultures were positive for Abiotrophia defectiva, and extensive investigations had not identified an extra-articular source of infection. Failing debridement antibiotic and implant retention procedure, the patient underwent a simultaneous bilateral 2-stage revision with articulated cement spacers impregnated with vancomycin and gentamycin. The patient received 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics after each stage. A. defectiva is a nutritiously fastidious organism, posing a challenge for clinical laboratories to isolate and perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing, yet prosthetic joint infections caused by A. defectiva are scarce in literature and present atypically with subacute signs of chronic infection. This poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, and two-stage revision is the only documented treatment that successfully eradicates the infection.

Keywords: infections, bone and joint infections, orthopaedics, prosthesis failure

Background

Bilateral simultaneous total knee revision surgery is a procedure rarely performed. We present the first case of bilateral total knee infection following Abiotrophia defectiva bacterial infection. A. defectiva is a gram-positive nutritionally variant Streptococcus (NVS) was first proposed by Kawamura et al in 1995 as a phylogenetically distinct genus from Streptococcus using 16S rRNA sequencing techniques.1 It displays characteristics of slow growth under laboratory conditions being nutritionally fastidious, and grows as satellite colonies around Staphylococcus epidermidis in blood agar. These characteristics make it a difficult organism to isolate and effectively treat with intravenous antibiotics. It exists as commensal flora in the oral, urogenital and intestinal tracts and is widely reported as an important pathogen in culture-negative endocarditis, endodontic infections and dental abscesses. Orthopaedic infections caused by Abiotrophia species are scarcely reported, and often displays characteristics of chronic subacute infections.2

Case presentation

A 65 year-old Caucasian man with bilateral total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) is admitted with a 6-week history of progressive knee pain and swelling bilaterally, but remains apyrexic with no signs of sepsis. No abnormalities were identified on physical examination, with active knee flexion to 100 degrees bilaterally; no disruption to skin integrity to allow entry for bacteraemia and no stigmata of endocarditis. Synovial fluid aspirates obtained by his general practitioner a week prior were turbid in nature, isolating A. defectiva bilaterally with no crystals on microscopy. His medical history includes type 2 diabetes mellitus (non-insulin dependent), hypertension, chronic kidney disease and hypercholesteraemia.

Further review of his medical records reveals wound complications 6 weeks following right total knee arthroplasty 5 years ago with purulent oozing at the wound edge which resolved with a course of oral antibiotics. Wound swab taken at the time yielded S. aureus sensitive to flucloxacillin, coamoxiclav and clarithromycin, while no growth was noted on blood cultures. He subsequently underwent a left TKA 2 years ago and re-presented 10 months later with knee swelling, no pain or joint line tenderness with an active range of movement 0–120° on examination. No signs of infection were detected and serum inflammatory markers returned normal. Swelling persisted with progressively increasing pain for the ensuing 9 months, with new flare-up of the contralateral right TKA. Bone scintigraphy detected no signs of infection; thus, no further procedures or antibiotics were commenced.

Investigations

Blood tests this admission indicated mildly raised inflammatory markers, white cell count (WCC) 10.3×109/L (normal range 4.0–11.0×109/L) and C-reactive protein (CRP) 54 mg/L (normal range <5 mg/L). Glycaemic control was suboptimal with HbA1c of 65 mmol/L. Three separate blood cultures were obtained on consecutive days across different sites, all three yielded A. defectiva, thus indicating bacteraemia instead of contamination. Unfortunately, we were unable to achieve sufficient growth for antibiotic sensitivity.

MRI of both knees revealed knee joint effusions with synovitis and inflammatory changes in the surrounding tendons and bones. Echocardiograms (transthoracic and transoesophageal) revealed a small patent foramen ovale, with normal heart valves and no evidence of endocarditis. CT of his chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no signs of occult infection or collection. Orthopantomogram and dental examination showed no signs of dental infection or abscess. Repeat bilateral knee arthrocentesis in theatre on admission, however, yielded no organisms on gram staining and extended cultures.

Differential diagnosis

By day 3 of admission, the patient had developed signs of sepsis with Abiotrophia bacteraemia. Despite multiple investigations, there was no evidence of an extra-articular source of infection leading to secondary prosthetic infections bilaterally, and was thus treated as primary prosthetic joint infections (PJIs).

Treatment

The patient was given intravenous vancomycin (1 g twice daily) and high-dose intravenous amoxicillin (2 g four times daily) after repeat aspirates were obtained. He returned to theatre 3 days later for open debridement of bilateral knee synovium and irrigation with 5 L saline and 500 mL betadine. Same-size polyethylene exchange was also performed and wounds were closed with drains inserted bilaterally.

Postoperatively, the patient developed intermittent episodes of fever lasting over a period of 2 weeks, with escalating inflammatory markers that did not decline despite remaining on intravenous antibiotics. On microbiologist’s advice, amoxicillin was switched to intraveneous tazobactam and piperacillin for coverage of potential pneumonia, despite no notable changes on postoperative chest radiograph. Repeat blood cultures at this point had exhibited no growth of any organisms.

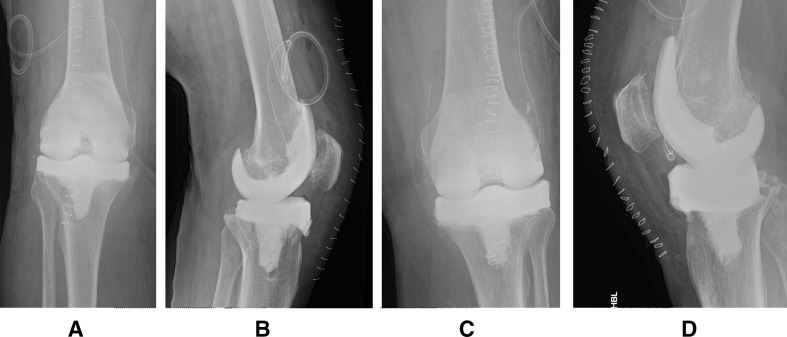

2 weeks later, the decision was then made to formally revise the bilateral TKAs simultaneously, and first stage bilateral TKA revision with radical synovectomy was performed. The infected prostheses were removed with minimal bone loss, joints washed with peroxide and articulated spacers (PALACOS vancomycin/gentamycin) inserted (figure 1). Bilateral pus and synovium tissue samples were taken intraoperatively, with no organisms detected for both initial and extended culture.

Figure 1.

First-stage knee revisions postoperative radiographs of right knee (A, B) and left knee (C, D), demonstrating moulded articulated cement spacers.

The patient experienced no further pyrexic episodes after first-stage revision surgery and inflammatory markers have declined and plateaued (CRP 10 mg/L). Drains were removed 48 hours postoperatively and the patient could mobilise full weight-bearing with articulated spacers in situ. Intravenous vancomycin was stopped 2 weeks postoperatively on microbiologist advice and he was discharged home with a 6-week course of oral amoxicillin and rifampicin, while awaiting second-stage revision surgery.

Weekly serum CRP monitoring remained low (<5 mg/L) and remained stable after oral antibiotics were stopped. 3 months after the initial first-stage revision, the patient was readmitted for simultaneous bilateral second-stage revision surgery. Bilateral knee aspirates were obtained 1 week prior to second-stage revision, yielding no growth on cultures. Total synovectomy was performed and cement spacers were removed, showing clean intra-articular tissue. Both femurs and tibias were resurfaced and reamed for insertion of new cemented prosthesis with femoral augmentation and tibial intramedullary stem extensions (Zimmer NexGen Complete Knee Solution; cement Heraeus COPAL G+V). Satisfactory alignment, offset and rotational stability were achieved bilaterally with normal patella tracking (figure 2). Joint capsule and wounds were closed with vicryl sutures with drains left in situ.

Figure 2.

Second-stage knee revisions postoperative radiographs of right knee (A, B) and left knee (C, D), demonstrating cemented prosthetic implant with femoral augmentation and intramedullary stems extensions.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, the patient remained apyrexic with stable declining serum inflammatory markers, while being started on intravenous vancomycin and meropenem. He had achieved full weight-bearing bilaterally with 0–90° range of movement bilaterally by 2 weeks postoperatively and was discharged home with a 6-week course of high-dose oral amoxicillin (1 g four times daily). Follow-up in clinic subsequently showed stable weekly inflammatory markers and good post-op recovery.

Discussion

A. defectiva is mainly associated with infective endocarditis, accounting for approximately 5%–6% of cases3; it is easily missed in early presentation due to negative blood cultures and subacute clinical picture. Despite being sensitive to antibiotic treatment, it is implicated in embolic complications and valvular destruction.

Orthopaedic, and indeed PJI associated with A. defectiva, are rare and scarcely reported in literature. A search on PubMed and Google Scholar yielded two reports of native joint infections,4 5 and four PJIs caused by A. defectiva.6–9

All cases of PJIs reported presented subacutely years after seemingly uncomplicated primary arthroplasties with progressive joint effusion and pain.6–9 All patients were reported to have presented apyrexic with no signs of sepsis, as with our patient. Mildly elevated serum CRP and normal WCCs were common characteristics, with culture-negative turbid synovial aspirates. Revision surgery was deemed the definitive treatment in these cases, using antibiotic-impregnated (typically vancomycin) temporary spacers, leading to good postoperative outcomes. Ince et al8 attempted radical open debridement and replacement of polyethylene components, in a debridement antibiotic and implant retention procedure, as per the initial management of our patient, but the infection quickly reoccurred within 2 months, leading to revision surgery.

The fastidious nature of A. defectiva makes isolating and antimicrobial susceptibility testing difficult for clinical laboratories,10 resulting in a challenge when rationalising long-course antibiotic regimes. There is variation in the reported susceptibility of A. defectiva in literature, mainly sensitive to vancomycin, amoxicillin, cephalosporin, clindamycin, meropenem and some resistance against erythromycin and penicillin.11 12

Difficulty isolating NVS from cultures causes a diagnostic dilemma as with cases of endocarditis. This dilemma is more evident in diagnosing NVS-related PJIs, as the typical ‘red, hot, swollen and stiff joint’ is not present, combined with unremarkable serum inflammatory markers and absence of signs of fever and sepsis. This combined with the difficulty in obtaining a joint aspirate given a prosthetic joint (requirement for aseptic theatre) make its detection far more challenging still.

Multidisciplinary approach with microbiology is vital at every step from collection of culture samples, time to incubation, culture methods and mediums, to allow maximal rates of detection. 16S rRNA gene sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry can be valuable in detecting NVS, as described by Rozemeijera et al9 and Tooley et al,6 respectively, but its cost effectiveness remains questionable due to the low prevalence of NVS-associated PJIs.

An extra-articular primary source of A. defectiva bacteraemia should be considered in all PJIs, more so with bilateral PJIs. Given no such source could be identified in our patient, it is hypothesised that the primary source was the right TKA wound infection 5 years previously, which persisted and remained latent after a short course of oral antibiotics due to its low-virulence nature. It subsequently seeded haematogeneously, as evidenced by the presence of A. bacteraemia on blood cultures, to the contralateral TKA 3 years later, causing chronic infection and intermittent symptoms of swelling and pain. This, however, remains a hypothesis, as no synovial fluid cultures were obtained 5 years ago and A. defectiva was not isolated on the wound swab or blood cultures.

Learning points.

Atraumatic nutritionally variant Streptococcus (NVS)-associated prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) remains a diagnostic challenge due to its atypical presentation and chronic onset. Intermittent flares may occur years after arthroplasty surgery, with typical markers of acute infection often absent. Prevalance of NVS-associated PJIs remains unknown given the scarcity of reported cases, perhaps due to under-reporting or difficulty isolating the pathogen from synovial samples.

Multidisciplinary approach with microbiology input is vital to maximise chances of isolating the organism. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is often difficult in these nutritionally fastidious organisms, posing a challenge for rationalising a long-term antibiotic regime for effective eradication.

Extra-articular sources of NVS-associated PJIs should be initially considered, necessitating prompt investigations, in particular heart valvular, dental, gastrointestinal and genitourinary sources. Due to the chronic nature of the infection, radical synovectomy and two-stage revision with long-term antibiotics seem to be the only curative approach. The authors feel a two-stage revision with an initial antibiotic impregnated spacer offers the best chance of achieving eradiation of the organism, although the evidence with reference to A. defectiva infection is limited, and lack of randomised control trials undoubtedly due to the ethical considerations of performing such studies in this cohort of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: The first author, JW, is primarily responsible for writing, drafting and literature review for the report. The second author, MPL, is responsible for data collection. The third author, PP, is responsible for reviewing and editing the report. The final author, AM, is responsible for supervising the writing of this case report and is the clinician with overall clinical responsibility for the treatment of the reported patient.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kawamura Y, Hou XG, Sultana F, et al. Transfer of Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus to Abiotrophia gen. nov. as Abiotrophia adiacens comb. nov. and Abiotrophia defectiva comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995;45:798–803. 10.1099/00207713-45-4-798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruoff KL. Nutritionally variant streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 1991;4:184–90. 10.1128/CMR.4.2.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet A. Human endocarditis due to nutritionally variant streptococci: Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus. Eur Heart J 1995;16 Suppl B:24–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_B.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilhelm N, Sire S, Le Coustumier A, et al. First case of multiple discitis and sacroiliitis due to Abiotrophia defectiva. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005;24:76–8. 10.1007/s10096-004-1265-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connor KM, Williams P, Pergam SA. An unusual case of knee pain: pseudogout and Abiotrophia defectiva infection. South Med J 2008;101:961–2. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817fe04c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tooley TR, Siljander MP, Hubers M. Development of a periprosthetic joint infection by Abiotrophia defectiva years after total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today 2019;5:49–51. 10.1016/j.artd.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassir N, Grillo J-C, Argenson J-N, et al. Abiotrophia defectiva knee prosthesis infection: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:438. 10.1186/1752-1947-5-438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ince A, Tiemer B, Gille J, et al. Total knee arthroplasty infection due to Abiotrophia defectiva. J Med Microbiol 2002;51:899–902. 10.1099/0022-1317-51-10-899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozemeijer W, Jiya TU, Rijnsburger M, et al. Abiotrophia defectiva infection of a total hip arthroplasty diagnosed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;70:142–4. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alberti MO, Hindler JA, Humphries RM. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Abiotrophia defectiva, Granulicatella adiacens, and Granulicatella elegans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016;60:1411–20. 10.1128/AAC.02645-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuohy MJ, Procop GW, Washington JA. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Abiotrophia adiacens and Abiotrophia defectiva. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;38:189–91. 10.1016/S0732-8893(00)00194-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasidthrathsint K, Fisher MA. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among a large, nationwide cohort of Abiotrophia and Granulicatella clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:1025–31. 10.1128/JCM.02054-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]