Abstract

Rationale: Dynamic collapse of the tracheal lumen (tracheomalacia) occurs frequently in premature neonates, particularly in those with common comorbidities such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The tracheal collapse increases the effort necessary to breathe (work of breathing [WOB]). However, quantifying the increased WOB related to tracheomalacia has previously not been possible. Therefore, it is also not currently possible to separate the impact of tracheomalacia on patient symptoms from parenchymal abnormalities.

Objectives: To measure the increase in WOB due to airway motion in individual subjects with and without tracheomalacia and with different types of respiratory support.

Methods: Fourteen neonatal intensive care unit subjects not using invasive mechanical ventilation were recruited. In eight, tracheomalacia was diagnosed via clinical bronchoscopy, and six did not have tracheomalacia. Self-gated three-dimensional ultrashort-echo-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on each subject with clinically indicated respiratory support to obtain cine images of tracheal anatomy and motion during the respiratory cycle. The component of WOB due to resistance within the trachea was then calculated via computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations of airflow on the basis of the subject’s anatomy, motion, and respiratory airflow rates. A second CFD simulation was performed for each subject with the airway held static at its largest (i.e., most open) position to determine the increase in WOB due to airway motion and collapse.

Results: The tracheal-resistive component of WOB was increased because of airway motion by an average of 337% ± 295% in subjects with tracheomalacia and 24% ± 14% in subjects without tracheomalacia (P < 0.02). In the tracheomalacia group, subjects who were treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) using a RAM cannula expended less energy for breathing compared with the subjects who were breathing room air or on a high-flow nasal cannula.

Conclusions: Neonatal subjects with tracheomalacia have increased energy expenditure compared with neonates with normal airways, and CPAP may be able to attenuate the increase in respiratory work. Subjects with tracheomalacia expend more energy on the tracheal-resistive component of WOB alone than nontracheomalacia patients expend on the resistive WOB for the entire respiratory system, according to previously reported values. CFD may be able to provide an objective measure of treatment response for children with tracheomalacia.

Keywords: tracheomalacia, computational fluid dynamics, continuous positive airway pressure, work of breathing, ultrashort-echo-time magnetic resonance imaging

Tracheomalacia is a condition that often occurs in neonates born prematurely or with congenital respiratory defects and is characterized by collapse of the tracheal lumen, which increases the work of breathing (WOB). The incidence of pediatric tracheomalacia is approximately 1:2,100 and is higher in patients with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia (1–4). Although some children with tracheomalacia can be minimally symptomatic, others may have severe respiratory compromise and a prolonged need for invasive respiratory support due to increased respiratory effort (4, 5). It is difficult to quantify the clinical effects of tracheomalacia separately from lung parenchymal and cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with those comorbidities, and at present, there is no technique to quantify increases in the WOB related specifically to tracheomalacia. Previous studies have measured esophageal pressure as a surrogate for pleural pressure and calculated the total WOB (elastic and resistive WOB) on the basis of the Campbell diagram (6–8).

Bronchoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosing tracheomalacia but is not quantitative (9). Recent studies have shown that magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) can be used to assess tracheomalacia and agrees well with bronchoscopic evaluation in neonates (2, 10). Although MRI has been shown to quantify the motion of the trachea, imaging alone cannot predict how this motion contributes to the patient WOB. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a well-established method to simulate airflow dynamics in the respiratory system. Previous studies based on CFD simulations have calculated the WOB (11), airway resistance (12, 13), and the pressure acting on the airway surface (14–16)—measures that directly quantify airway function.

Most previous patient-specific CFD studies have been based on MRI or computed tomographic (CT) images of the airway, and simulations were based on rigid anatomical models that are unsuitable for dynamic conditions such as tracheomalacia (14, 15). Other studies have used idealized motion, which may not be physiological (17, 18). However, Bates and colleagues (19) have shown that real, physiological airway motion can be derived from rapid cine MRI or dynamic CT images.

Here, we present a technique both to quantify the patient-specific tracheal-resistive contribution to the WOB and to demonstrate the increase in the WOB due to tracheomalacia in neonatal patients. We have used self-gated, three-dimensional ultrashort-echo-time (UTE) MRI to generate high-resolution cine images that capture the patient’s actual airway motion during the entire respiratory cycle for use in CFD simulations (20, 21). We hypothesize that airway motion increases the tracheal-resistive component of the WOB (TR-WOB) and that this increase will be larger in neonatal subjects with clinically diagnosed tracheomalacia. To test this hypothesis, we compare the TR-WOB between two simulations of respiratory airflow in each of 14 neonatal subjects. The first simulation includes physiological airway motion obtained from self-gated cine MRI. The second simulation uses a virtual airway held static at approximately the largest size observed during the breathing cycle in that subject to provide each subject’s airway with its own control (static) airway. The increase in the TR-WOB due to airway motion between the simulations was calculated for each subject and compared with the clinical tracheomalacia diagnosis. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (22).

Methods

Study Subjects

This research cohort consisted of 14 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) subjects from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; all patients were imaged with approval from the institutional review board and informed parental consent. The inclusion criteria for this study were subjects either breathing room air or using noninvasive respiratory support at the time of MRI. Each subject was only imaged at one time point while on clinically indicated respiratory support as determined by the primary clinical team.

Subjects either had BPD, tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia, or bronchoesophageal fistula or were respiratory control subjects with no suspected lung or airway disease (Table 1). Eleven subjects underwent clinical bronchoscopy, and in eight of those subjects, tracheomalacia was diagnosed, whereas no tracheomalacia was diagnosed in three subjects. Three respiratory control subjects did not undergo clinical bronchoscopy because airway issues were not clinically suspected; these patients were designated as having no tracheomalacia for this study.

Table 1.

Patient demographic information

| Study Group | Subject | Sex | Clinical Diagnosis | PMA at MRI (wk) | Weight at MRI (kg) | Respiratory Support at MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No tracheomalacia | 01 | M | BEF | 40 | 3.7 | Room air |

| 02 | F | Respiratory control | 40.9 | 3.61 | Room air | |

| 03 | M | Respiratory control | 40.3 | 3.9 | Room air | |

| 04 | F | Respiratory control | 39.4 | 2.85 | Room air | |

| 05 | M | BPD | 43 | 3.6 | HFNC | |

| 06 | M | BPD | 38.7 | 3.07 | HFNC | |

| Tracheomalacia | 07 | F | TEF/EA | 40 | 3.18 | Room air |

| 08 | F | TEF/EA | 40.1 | 2.7 | Room air | |

| 09 | F | BPD | 43.1 | 4.13 | Room air | |

| 10 | M | BPD | 43.1 | 5.35 | Room air | |

| 11 | F | TEF/EA | 41.3 | 2.91 | HFNC | |

| 12 | F | BPD | 43 | 3.35 | HFNC | |

| 13 | M | BPD | 41 | 1.94 | RAM CPAP | |

| 14 | M | BPD | 39.6 | 4.2 | RAM CPAP |

Definition of abbreviations: BEF = bronchoesophageal fistula; BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC = high-flow nasal cannula; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PMA = postmenstrual age; TEF/EA = tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia.

Obtaining MRI of the Airway throughout the Breathing Cycle

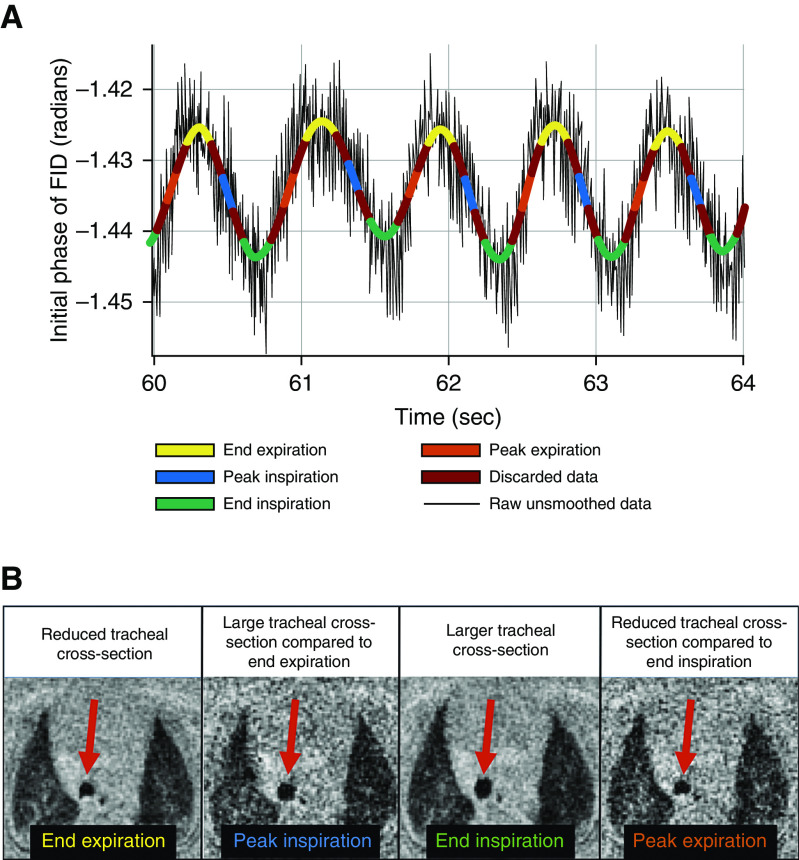

Neonates were imaged using self-gated, UTE MRI in a 1.5-T scanner with 18-cm bore size located within the NICU (initially an orthopedic scanner from ONI Medical Systems, which was repurposed for neonatal imaging and is currently running GE HDx software) (21, 23–26). Relevant MRI parameters were as follows: image resolution = 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 mm, echo time = 200 microseconds, repetition time = 5.2 milliseconds, flip angle = 5°, field of view = 18 cm, number of projections ≈ 200,000, and scan time = ∼16 minutes (20). The magnitude and phase of the initial point of each MR free induction decay (FID) was modulated by bulk motion and quiescent breathing of the neonate; this effect allowed periods of bulk motion to be discarded and allowed the respiratory waveform to be recorded (Figure 1A), as previously described (20).

Figure 1.

(A) Time course of the initial phase of each magnetic resonance radial acquisition (FID) (black line) and the smoothed respiratory waveform for each breath binned into four phases of respiration (yellow = end expiration; blue = peak inspiration; green = end inspiration; orange = peak expiration), over a representative snapshot of 4 seconds of acquisition. (B) Axial slice from respiratory-gated ultrashort-echo-time magnetic resonance imaging of the thorax showing the trachea of a tidal-breathing neonatal subject with tracheomalacia at different time points within the breathing cycle. Data from each respiratory bin were used to reconstruct an individual respiratory-gated image. (A) Note that the initial phase of the FID captures negative displacement of the diaphragm, explaining the inverted polarity of the resulting waveform. (B) The tracheal cross-section was smaller at end expiration and larger at end inspiration, with intermediate changes at peak inspiration and peak expiration. FID = free induction decay.

The respiratory waveform was separated into four bins (end expiration, peak inspiration, end inspiration, and peak expiration) on the basis of the amplitude of each respiratory cycle (Figure 1A). The phase or magnitude of the FID signal was chosen for data binning on the basis of the signal-to-noise ratio of the peak-to-peak respiratory signal (20). Image reconstruction with sampling-density compensation was performed, and data were then interpolated onto a Cartesian grid. Images were generated by the Fourier transformation of the regridded k space (21, 27, 28). Figure 1B shows axial respiratory-gated UTE MR image reconstructions of the tracheal cross-section of a subject with tracheomalacia at different time points of the breathing cycle.

Obtaining Airway Surfaces and Motion from MRI

To create virtual airway surfaces for CFD simulations, airways were semiautomatically segmented from gated UTE MR images at the four respiratory phases using ITK-SNAP (version 3.8.0; Penn Image Computing and Science Laboratory), using a three-dimensional active-contour segmentation technique (29). The initial intensity threshold was determined by taking the average of the intensity of the tissue surrounding the airway and the airway lumen (10). All airway geometries extended from the main bronchi to above the glottis and into the pharynx. Previous studies have shown that neglecting the upper airway does not affect flow distribution below the glottis (30, 31). The effect of the upper airway and tracheal shape and motion is captured by the dynamic MRI. A triangulated three-dimensional surface was produced, and surfaces were smoothed using Taubin smoothing (smoothing factors, λ = 0.6 and μ = −0.6, respectively; parameters chosen to prevent volume shrinkage) in MeshLab 2016 (Visual Computing Lab, The Institute of Information Science and Technologies-National Research Council, Italy (32, 33).

Airway surfaces at the four consecutive points in the breathing cycle were registered together using the Medical Image Registration ToolKit (version 1.1, https://mirtk.github.io/; Department of Computing, Imperial College London) to determine the airway motion throughout a breath. This motion was then interpolated to produce the position of the airway throughout the respiratory cycle (19).

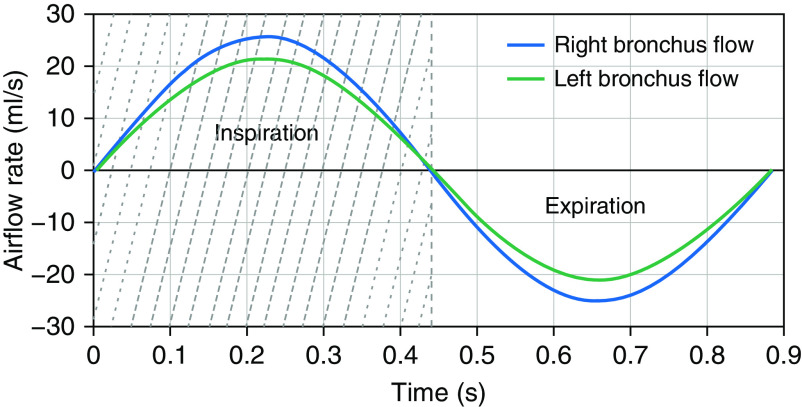

Obtaining Airflow Waveforms from Lung Volumes

From the many breaths recorded during the imaging period, a median waveform was determined for each subject from the MRI FID signal (see Obtaining Airway Surfaces and Motion from MRI in the Methods section), to represent a typical breath during the MRI examination. The airflow rates through the left and right bronchi were calculated from this median respiratory waveform, scaled by the left and right lung tidal volume, respectively (Figure 2). Left and right lung tidal volumes were measured separately from the difference in whole-lung segmentation volumes on MR images gated to end inspiration and end expiration (34).

Figure 2.

Left and right bronchial airflow rates of an example subject with tracheomalacia. The light-gray shaded area indicates inspiration, and the white area indicates expiration during the breathing cycle.

Modeling Respiratory Airflow Using CFD

CFD simulations of airflow in the airway were performed on the basis of the airway surface, motion, and airflow rates throughout a representative breath, as described in the previous sections. Airflow rates were applied to each bronchus while the inlet at the upper airway was held at atmospheric pressure. A commercial CFD package, STAR-CCM+ 11.06.011 (Siemens Product Lifecycle Management software) was used to solve the flow-governing Navier-Stokes equations with the large-eddy simulation turbulence model, in methods similar to those of previous studies (35, 36). CFD meshes had approximately two million cells with seven prism layers on the walls and polyhedral cells constructing the interior mesh. The simulation temporal resolution was 0.8 milliseconds. Air was considered incompressible and isothermal at 37°C throughout the respiratory cycle, and the no-slip condition was applied to the entire airway surface.

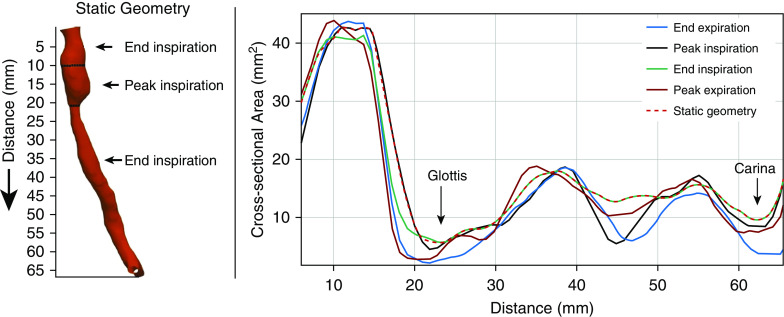

Generating Static Airway Geometry

For each subject, a second simulation was performed using the same MRI acquisition, but with a virtually enforced static airway surface to provide each subject’s airway with its own control airway. This static airway surface was generated as a representation of the airway at its approximate largest size during the breath. This airway is intended to be the anatomy that causes the least resistance to airflow and the lowest WOB during the breath for that subject.

Generally, the largest tracheal volume through the breathing cycle was found at end inspiration, as expected. Therefore, this surface was used for the static airway model. However, in some cases, the end inspiration geometry exhibited a narrowing somewhere along its length. As a result, a static geometry was created through combining geometries from end inspiration and from another time point that did not exhibit this narrowing. Figure 3 is an example of static geometry in a subject with tracheomalacia.

Figure 3.

Construction of the static airway from airway surfaces throughout the respiratory cycle. Here, as in nearly all cases, the end inspiration geometry is the largest throughout most of respiration (although the geometry at peak inspiration was used above the glottis).

Calculating the WOB from CFD Results

To calculate the TR-WOB from CFD results, power loss from the glottis to carina was calculated for the entire breathing cycle, as described by Bates and colleagues (11, 37). The area under the power-loss curve over the course of the breath gives the resistive WOB of the trachea.

A two-tailed unpaired t test with unequal variance was used to compare the TR-WOB of tracheomalacia and nontracheomalacia groups for both static and dynamic airways. A two-tailed paired t test with unequal variance was used to compare the TR-WOB between dynamic and static airways. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Information of Study Subjects

Subjects were imaged at approximate term-equivalent age (41.0 ± 1.5 wk postmenstrual age) (Table 1). The average weight and height of the subject cohort were 3.5 ± 0.8 kg and 49 ± 4 cm at MRI.

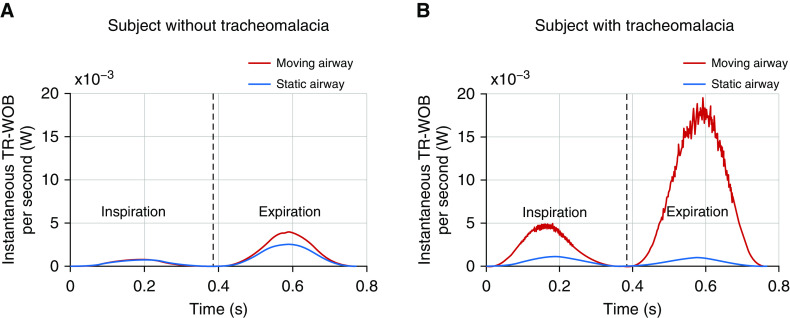

Calculation of Increase in the TR-WOB

Figure 4 shows the instantaneous TR-WOB/s over the course of a breath for simulations with a moving airway (red) and a static airway (blue) for two example subjects, one with tracheomalacia and one without tracheomalacia. The difference between the static and dynamic curves equals the increase in the TR-WOB due to airway motion at that moment in the breath. In the subject without tracheomalacia (Figure 4A), there is little difference in the TR-WOB due to motion during inspiration, but the TR-WOB is increased during expiration, likely because of minor dynamic collapse present even in normal airways. In the subject with tracheomalacia (Figure 4B), there is a marked difference in the static and dynamic TR-WOB during inspiration, with an even larger difference during expiration. The difference in the areas under the curve shows that the total increase in the WOB is considerably higher in the subject with tracheomalacia. The daily TR-WOB values in the subject without tracheomalacia (Figure 4A) were 84.9 J with airway motion and 62.2 J without airway motion (an increase of 36%). In the subject with tracheomalacia (Figure 4B), the daily TR-WOB values were 421.7 J with airway motion and 44.5 J without airway motion (an increase of 848%).

Figure 4.

The instantaneous TR-WOB/s due to airway motion in a realistically dynamic airway (red) and an airway held static (blue) for (A) a subject without tracheomalacia and (B) a subject with tracheomalacia. Black dashed lines represent the end inspiration. TR-WOB = tracheal-resistive component of the work of breathing.

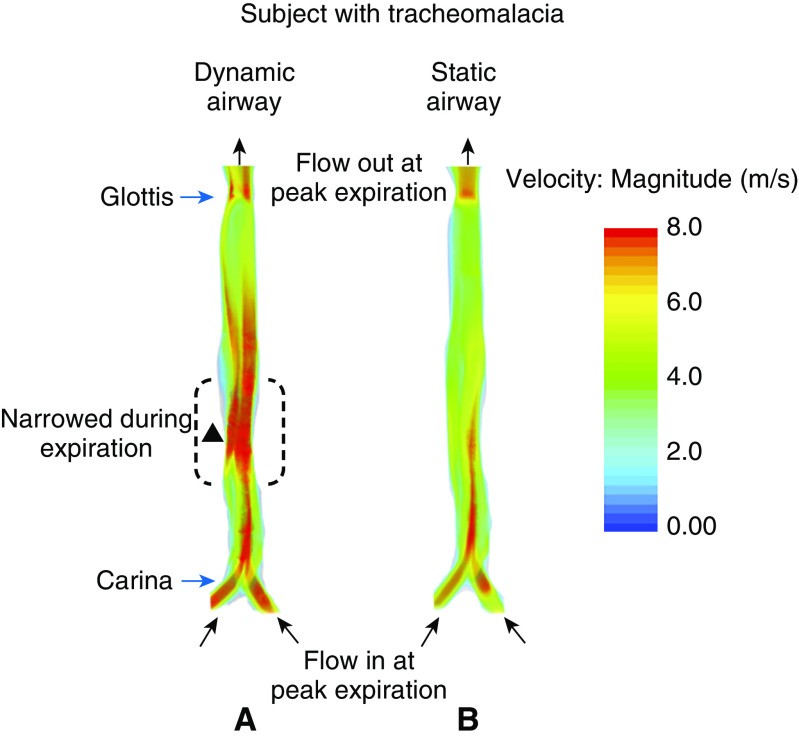

Velocity Distribution of the Airway at Peak Expiration

Figure 5 compares flow velocities for dynamic and static airway simulations revealing the source of the measured increase in the WOB due to airway motion in an example subject with tracheomalacia. The figure shows the distribution of airflow velocity in the simulation with and without motion at peak expiration. In the simulation with airway motion (Figure 5A), the trachea has narrowed during expiration (dotted lines marked with solid triangle at the narrowest point), causing the airflow to accelerate and form a high-velocity jet where the trachea returns to its normal width. This jet requires much more breathing effort at peak expiration due to losses associated with friction and jet breakdown. In the simulation without motion (Figure 5B), the airway remains patent, the flow is slower, a jet does not form, and thus breathing effort is much lower than when the airway dynamically collapses.

Figure 5.

Airflow velocity distribution of a subject with tracheomalacia during peak expiration in the computational fluid dynamics simulation (A) with airway motion and (B) without airway motion. The figure shows the coronal projection of the trachea in the two simulations. Note that the model’s geometry extends into the upper airway, but this was omitted from this figure for clarity.

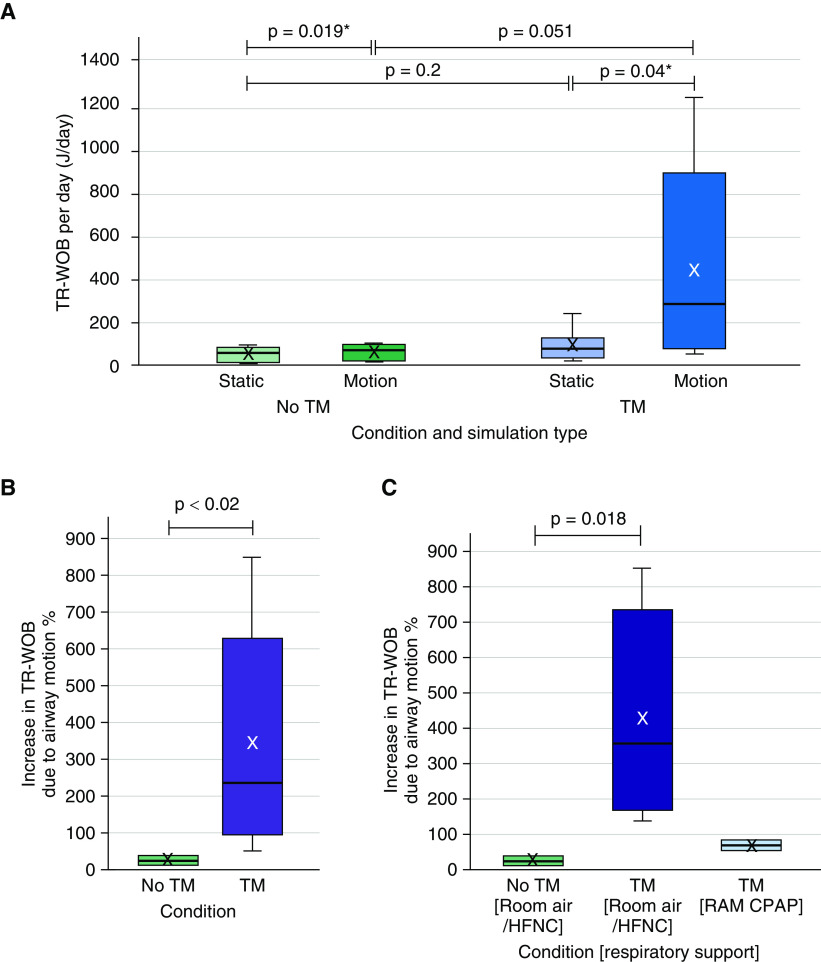

Analysis of the TR-WOB and the Effect of Respiratory Support

The increase in the TR-WOB due to airway motion for all subjects, calculated over 1 day, is shown in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6A, the average of the TR-WOB calculated over 1 day for the subjects without tracheomalacia was 51.0 ± 32.3 J in the static airway and 60.4 ± 35.7 J in the moving airway. However, for the subjects with tracheomalacia, the average was 89.9 ± 71.9 J in the static airway and 437.2 ± 454.1 J in the moving airway. Furthermore, the average increase in the TR-WOB due to airway motion was significantly different between the six subjects without tracheomalacia (24% ± 14%; range, 10–38%) and the eight subjects with tracheomalacia (337% ± 295%; range, 50–848%) (P < 0.02), with the effect of airway motion on the TR-WOB being far greater in subjects with tracheomalacia (Figure 6B). The average TR-WOB was higher for subjects with tracheomalacia compared with the subjects without tracheomalacia, even in the simulation without airway motion, although not significantly (P = 0.2). Similar results were found when the TR-WOB was normalized by the weight of each subject.

Figure 6.

(A) The tracheal-resistive component of the work of breathing (TR-WOB)/d of the subjects with and without tracheomalacia (TM), calculated via computational fluid dynamics simulations for static or moving airways. The increase in the TR-WOB as a (B) percentage compared with static airway for the subjects with and without TM and (C) on different respiratory support at the time of magnetic resonance imaging. (B) The average increase in the TR-WOB due to motion was 24% ± 14% (range, 10–38%) for the subjects without TM and that increase for the subjects with TM was 337% ± 295% (range, 50–848%). (C) The room-air/HFNC group demonstrated a higher increase in the TR-WOB than the RAM continuous-positive-airway-pressure (CPAP) group of the subjects with TM (P values were not calculated due to the lower number of subjects in the RAM CPAP group). The plot elements are as follows: average = cross; median = black line; interquartile range (IQR) = colored box; data within 1.5 times the IQR below 25% or above 75% = whiskers. *P values were calculated using a two-tailed paired t test. HFNC = high-flow nasal cannula.

To assess the effect of respiratory support, subjects were separated on the basis of their support during MRI into groups on room air/high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) using RAM cannula; subjects with and without tracheomalacia were on room air/HFNC (n = 6 and n = 6, respectively), whereas only subjects with tracheomalacia were on CPAP using RAM cannula (n = 2). As shown in Figure 6C, the average increase in the TR-WOB due to airway motion was 24% ± 14% in the subjects without tracheomalacia on room air/HFNC, 67% ± 23% in the subjects with tracheomalacia on RAM CPAP, and 428% ± 288% in the subjects with tracheomalacia on room air/HFNC. It is likely that respiratory support using RAM CPAP dropped the energy expenditure required for breathing compared with room air/HFNC in subjects with tracheomalacia.

Discussion

This study presents a novel method of calculating the TR-WOB in neonates with and without tracheomalacia using UTE MRI combined with CFD simulations. This technique also quantifies the increase in the TR-WOB due to the airway motion caused by tracheomalacia. These results demonstrate the clinical relevance of evaluating the TR-WOB of these vulnerable patients by revealing the reduction in energy expenditure that could be achieved by treating tracheomalacia. The major finding of this study was that the TR-WOB due to airway motion increased more in subjects with tracheomalacia than in subjects without tracheomalacia. Furthermore, in a small number of subjects with tracheomalacia who were treated with RAM CPAP, the TR-WOB was similar to that of patients without tracheomalacia, demonstrating the efficacy of this treatment option. Indeed, previous studies have shown that CPAP improves respiratory mechanics in neonates with tracheomalacia by increasing forced expiratory flow and raising lung volume (38, 39). Our results indicate that there may be high value in calculating the TR-WOB in future studies to evaluate clinical decision-making, such as whether ventilation support should be maintained in the NICU for longer periods to foster growth, rather than focusing on weaning.

The imaging technique used here was noninvasive, was nonionizing, and was performed during tidal breathing without requiring sedation. This method can be easily applied to neonatal, older pediatric, and adult populations. Although UTE MRI may not be clinically common at present, the availability of UTE MRI is increasing. All major MRI vendors offer a clinical UTE MRI sequence or are expected to have clinical versions available in the near future. Retrospective gating of the UTE MRI data allows for detection and removal of imaging data corrupted by motion and for several images to be reconstructed throughout the breathing cycle, revealing respiratory motion. Small modifications to UTE MRI protocols may be necessary to achieve respiratory gating. In future studies, respiratory-gated MRI would allow clinicians to visually evaluate the response of tracheomalacia to interventions such as CPAP with the airway in its natural state. Bronchoscopy has similarly been used to titrate CPAP; however, the presence of the bronchoscope alters respiratory mechanics and can generate autopositive end-expiratory pressure, which could affect airway collapse (40). Another limitation of bronchoscopy is that it requires sedation, and the impact of sedation on tracheal-wall motion is entirely unknown. Airway dynamics are also difficult to quantify objectively using bronchoscopy.

The results indicate that subjects with tracheomalacia expend much more energy for breathing than subjects without tracheomalacia, mostly due to increased airway motion (Figure 5). Even when airway motion is removed, the TR-WOB of the subjects with tracheomalacia was nearly twice high as that of the subjects without tracheomalacia (Figure 6). Analysis of the airway eccentricity via MRI (using the method described by Bates and colleagues [10]) revealed that tracheas in patients with tracheomalacia are more eccentric than healthy tracheas even at inspiration, perhaps suggesting that the trachea does not fully open at any time during the respiratory cycle. There is no evidence of cardiovascular compression contributing to the increase in the static TR-WOB in the MR images. BPD was diagnosed in more than 50% of the subjects with tracheomalacia, and it may be that BPD has effects on the trachea in addition to those of tracheomalacia. In creating static airway models, the airway was not always largest throughout its length during inspiration. Airway narrowing during inspiration occurred in the extrathoracic trachea or near the thoracic inlet. In addition, narrowing on inspiration occurred in the upper airway, which is included in the CFD model to ensure realistic inflow to the trachea.

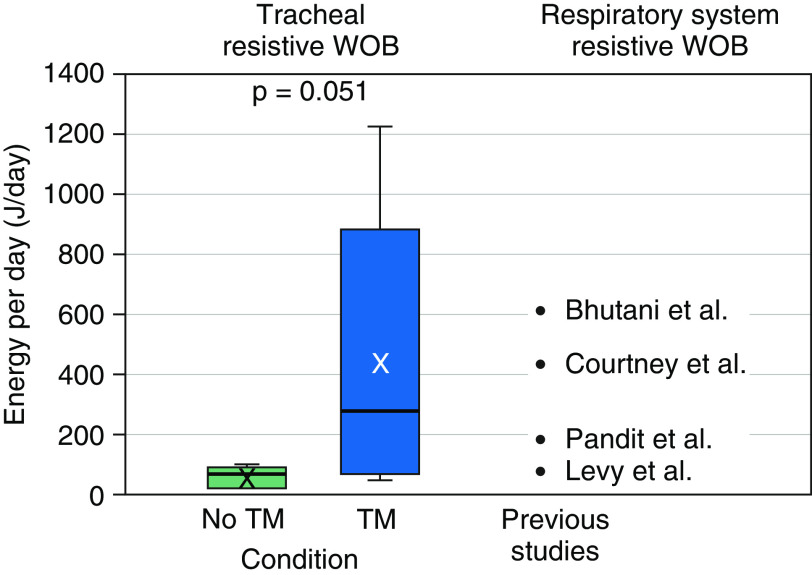

This study has shown how tracheomalacia affects the WOB; future work may be able to relate measurements of airway anatomy, which could be made clinically, to the likely resultant effect on the WOB. Although previous studies have calculated the entire (resistive and elastic) WOB for the respiratory system (41–44), this study shows a method to regionally calculate the resistive WOB, allowing for the contribution of airway disease at different levels of the airway to be separately evaluated. To put these values of the TR-WOB due to airway motion in context with previously reported values for the respiratory system–resistive WOB, these values were compared (Figure 7). Previous studies have calculated the respiratory system–resistive WOB in neonates with various lung diseases (Table 2). The data show that in subjects without tracheomalacia, the value of the TR-WOB represents a small fraction of the respiratory system–resistive WOB. However, in subjects with tracheomalacia who have a significantly increased TR-WOB, the value of the TR-WOB alone is as large or larger than the value of the respiratory system–resistive WOB expected in neonates who are healthy, are apneic, or have respiratory distress syndrome.

Figure 7.

Comparison between the tracheal-resistive component of the work of breathing (TR-WOB)/d of the present study and the respiratory system–resistive WOB of previous studies. The average TR-WOB for subjects without tracheomalacia (TM) was 60.4 ± 35.7 J/d and that value for subjects with TM was 437.2 ± 454.1 J/d. The plot elements are as follows: average = cross; median = black line; interquartile range (IQR) = colored box; data within 1.5 times the IQR below 25% or above 75% = whiskers.

Table 2.

Previous studies subject demographics and WOB values

| Study | Average Gestational Age (wk) | Average Age at Study (d) | Average Weight at Study (kg) | Clinical Diagnosis | Respiratory System–Resistive WOB (J/d) | Additional Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levy et al. (41) | 29.7 ± 2.1 | 33.6 ± 1.4 | 1.757 ± 0.248 | Healthy | 89.28 | Premature infants nearing discharge from the NICU |

| Pandit et al. (42) | 28 ± 1.7 | 14 ± 13 | 1.151 (0.664–1.461) | Apnea or mild respiratory distress | 188.64* | NCPAP at 0 cm H2O |

| Bhutani et al. (43) | 34.4 ± 1.3 | <2 | 2.129 ± 0.598 | Respiratory distress syndrome | 616.32 | — |

| Courtney et al. (44) | 27.9 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 4.3 | 1.092 ± 0.222 | Mild respiratory distress | 442.08 | NCPAP at 0 cm H2O |

Definition of abbreviations: NCPAP = nasal continuous positive airway pressure; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit; WOB = work of breathing.

Data are the mean ± standard deviation or the median (range).

Calculations are based on the median weight.

The average increase in the TR-WOB due to motion was 427.7% in the six subjects with tracheomalacia without RAM CPAP, indicating that neonates with tracheomalacia spend more than five times more energy for breathing than they would if their airway was held static (Figure 6C). Although the present study only measured the effects of tracheomalacia on the resistive WOB within the central airway, there may be increases in the WOB elsewhere that are attributable to tracheomalacia due to increased pressure forces; therefore, the total increase in the WOB due to tracheomalacia may be even higher than the values reported here.

The results of this study demonstrate a markedly elevated WOB due to tracheomalacia. For infants with dynamic airway issues, energy that would otherwise be used for growth and development must be spent on simply breathing, and tracheomalacia may therefore have a greater impact on developmental progress in neonates. In the future, the method used here to calculate the WOB may guide clinical decision-making to reduce the WOB through improved respiratory support to mitigate airway collapse. These treatments may include CPAP, aortopexy, tracheopexy, and stent placement. Increasing caloric intake may also need to be considered. The ability to quantify the contribution of tracheomalacia to the WOB and respiratory symptoms may help determine when these treatments become beneficial and provide an objective, quantifiable measure of the response to various treatment options.

One of the limitations of this study was the relatively small number of subjects, which reflects the few NICU subjects with tracheomalacia who did not receive invasive ventilator support at the time of MRI. The presence of an endotracheal tube can bypass a malacic segment of the trachea. Therefore, subjects with endotracheal tubes were excluded from this study. Previous studies have demonstrated that tracheomalacia is strongly associated with respiratory failure requiring chronic mechanical ventilation in neonates (45). Thus, it is likely that patients with significant tracheomalacia were excluded because of the mechanical ventilation needed to support their respiratory work. Hence, our results may underestimate the true impact of tracheomalacia on respiratory work in the most severe subjects. Other limitations include the fact that respiratory CFD is not currently clinically available, although U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved CFD simulations are performed in cardiovascular medicine (46, 47). CFD simulations are time consuming and computationally expensive (the CFD run time was on order of 1,000 core-hours per second of breathing). The accuracy of the study was somewhat limited by the UTE MR image resolution (isotropic resolution of ∼0.7 mm), but only marginal improvements in resolution can be gained via computed tomography. Further improvements in UTE MR image quality and resolution are expected, as this is an active area of research.

This study is the first to demonstrate that tracheomalacia plays a significant role in the increased neonatal WOB, which may have important implications for patient care, growth, and nutrition. The ability to quantify the contribution of tracheomalacia to the WOB and respiratory symptoms may help determine when these treatments become beneficial and may be an objective measure of the response to interventions for tracheomalacia. The techniques used in this study also can be applied to model and quantify upper-airway obstructions, such as laryngomalacia, retrognathia, and bilateral vocal-cord paralysis.

Conclusions

CFD simulations combined with self-gated UTE MRI can measure the TR-WOB in neonates. This allows the impact of tracheal dynamics on the WOB to be considered independently from the rest of the respiratory system, which is particularly relevant when tracheomalacia presents with comorbid lung disease. The measurement of the WOB may be used to understand patients’ required respiratory support while in the NICU. Airway motion significantly increased the tracheal WOB, particularly in subjects with tracheomalacia, compared with the same airway held static in its largest shape; this finding may have important implications for patient care and growth. Future studies may model the whole airway and report the resistive WOB for the upper airway, trachea, and each generation of the bronchi separately. This would allow clinicians to identify the section of the airway tree contributing to specific quantitative increases in the resistive WOB. Combined with a calculation of the elastic WOB, this CFD and MRI–based technique provides clinicians with a detailed regional assessment of the neonatal respiratory system.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH; S.B.F.), grants from the NIH (R01 HL146689, K99 HL144822, and T32 HL007752), and the Cincinnati Children’s research foundation. S.B.F. was supported by grants from GE Healthcare outside of the submitted work.

Author Contributions: Concept and design: C.C.G., E.B.H., J.C.W., and A.J.B. Data analysis, manuscript drafting, editing, and approval: all authors.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Boogaard R, Huijsmans SH, Pijnenburg MWH, Tiddens HAWM, de Jongste JC, Merkus PJFM. Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: incidence and patient characteristics. Chest. 2005;128:3391–3397. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hysinger EB, Bates AJ, Higano NS, Benscoter D, Fleck RJ, Hart CK, et al. Ultrashort echo-time MRI for the assessment of tracheomalacia in neonates. Chest. 2020;157:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCubbin M, Frey EE, Wagener JS, Tribby R, Smith WL. Large airway collapse in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1989;114:304–307. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hysinger EB, Friedman NL, Padula MA, Shinohara RT, Zhang H, Panitch HB, et al. Children’s Hospitals Neonatal Consortium. Tracheobronchomalacia is associated with increased morbidity in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1428–1435. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-178OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNamara VM, Crabbe DCG. Tracheomalacia. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roussos C, Macklem PT, editors. The thorax. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hjalmarson O, Olsson T. IV. Work of breathing. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1974;63:49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mancebo J, Isabey D, Lorino H, Lofaso F, Lemaire F, Brochard L. Comparative effects of pressure support ventilation and intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB) in non-intubated healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1901–1909. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08111901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masters IB, Zimmerman PV, Pandeya N, Petsky HL, Wilson SB, Chang AB. Quantified tracheobronchomalacia disorders and their clinical profiles in children. Chest. 2008;133:461–467. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates AJ, Higano NS, Hysinger EB, Fleck RJ, Hahn AD, Fain SB, et al. Quantitative assessment of regional dynamic airway collapse in neonates via retrospectively respiratory-gated 1 H ultrashort echo time MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:659–667. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates AJ, Comerford A, Cetto R, Schroter RC, Tolley NS, Doorly DJ. Power loss mechanisms in pathological tracheas. J Biomech. 2016;49:2187–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Backer JW, Vos WG, Devolder A, Verhulst SL, Germonpré P, Wuyts FL, et al. Computational fluid dynamics can detect changes in airway resistance in asthmatics after acute bronchodilation. J Biomech. 2008;41:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Persak SC, Sin S, McDonough JM, Arens R, Wootton DM. Noninvasive estimation of pharyngeal airway resistance and compliance in children based on volume-gated dynamic MRI and computational fluid dynamics. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:1819–1827. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01230.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouns M, Jayaraju ST, Lacor C, De Mey J, Noppen M, Vincken W, et al. Tracheal stenosis: a flow dynamics study. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:1178–1184. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01063.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih T-C, Hsiao H-D, Chen P-Y, Tu C-Y, Tseng T-I, Ho Y-J. Study of pre- and post-stent implantation in the trachea using computational fluid dynamics. J Med Biol Eng. 2014;34:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu C, Sin S, McDonough JM, Udupa JK, Guez A, Arens R, et al. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of the upper airway of children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in steady flow. J Biomech. 2006;39:2043–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, Feng Y, Fromen CA. Glottis motion effects on the particle transport and deposition in a subject-specific mouth-to-trachea model: a CFPD study. Comput Biol Med. 2020;116:103532. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heenan AF, Matida E, Pollard A, Finlay WH. Experimental measurements and computational modeling of the flow field in an idealized human oropharynx. Exp Fluids. 2003;35:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates AJ, Schuh A, McConnell K, Williams BM, Lanier JM, Willmering MM, et al. A novel method to generate dynamic boundary conditions for airway CFD by mapping upper airway movement with non-rigid registration of dynamic and static MRI. Int J Numer Methods Biomed Eng. 2018;34:e3144. doi: 10.1002/cnm.3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higano NS, Hahn AD, Tkach JA, Cao X, Walkup LL, Thomen RP, et al. Retrospective respiratory self-gating and removal of bulk motion in pulmonary UTE MRI of neonates and adults. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:1284–1295. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn AD, Higano NS, Walkup LL, Thomen RP, Cao X, Merhar SL, et al. Pulmonary MRI of neonates in the intensive care unit using 3D ultrashort echo time and a small footprint MRI system. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:463–471. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunatilaka CC, Bates AJ, Higano NS, Hahn AD, Fain SB, Hysinger EB, et al. Elevated work of breathing in neonates with tracheomalacia using computational fluid dynamics [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:A4684. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tkach JA, Li Y, Pratt RG, Baroch KA, Loew W, Daniels BR, et al. Characterization of acoustic noise in a neonatal intensive care unit MRI system. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1011–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-2909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tkach JA, Merhar SL, Kline-Fath BM, Pratt RG, Loew WM, Daniels BR, et al. MRI in the neonatal ICU: initial experience using a small-footprint 1.5-T system. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:W95–W105. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tkach JA, Hillman NH, Jobe AH, Loew W, Pratt RG, Daniels BR, et al. An MRI system for imaging neonates in the NICU: initial feasibility study. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:1347–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higano NS, Spielberg DR, Fleck RJ, Schapiro AH, Walkup LL, Hahn AD, et al. Neonatal pulmonary magnetic resonance imaging of bronchopulmonary dysplasia predicts short-term clinical outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1302–1311. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pipe JG, Menon P. Sampling density compensation in MRI: rationale and an iterative numerical solution. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:179–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199901)41:1<179::aid-mrm25>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson JI, Meyer CH, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Selection of a convolution function for Fourier inversion using gridding [computerised tomography application] IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10:473–478. doi: 10.1109/42.97598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao Q, Cetto R, Doorly DJ, Bates AJ, Rose JN, McIntyre C, et al. Assessing changes in airflow and energy loss in a progressive tracheal compression before and after surgical correction. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48:822–833. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin CL, Tawhai MH, McLennan G, Hoffman EA. Characteristics of the turbulent laryngeal jet and its effect on airflow in the human intra-thoracic airways. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;157:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taubin G. ICCV ‘95 proceedings of the fifth International Conference on Computer Vision. Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society; 1995. Curve and surface smoothing without shrinkage; pp. 852–857. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cignoni P, Callieri M, Corsini M, Dellepiane M, Ganovelli F, Ranzuglia G. Sixth Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference: Salerno, Italy, July 2nd–4th, 2008. Aire-la-Ville, Switzerland: Eurographics Association; 2008. MeshLab: an open-source mesh processing tool; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoder LM, Higano NS, Schapiro AH, Fleck RJ, Hysinger EB, Bates AJ, et al. Elevated lung volumes in neonates with bronchopulmonary dysplasia measured via MRI. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54:1311–1318. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates AJ, Schuh A, Amine-Eddine G, McConnell K, Loew W, Fleck RJ, et al. Assessing the relationship between movement and airflow in the upper airway using computational fluid dynamics with motion determined from magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2019;66:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates AJ, Comerford A, Cetto R, Doorly DJ, Schroter RC, Tolley NS. Computational fluid dynamics benchmark dataset of airflow in tracheas. Data Brief. 2017;10:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.11.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates AJ, Cetto R, Doorly DJ, Schroter RC, Tolley NS, Comerford A. The effects of curvature and constriction on airflow and energy loss in pathological tracheas. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2016;234:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panitch HB, Allen JL, Alpert BE, Schidlow DV. Effects of CPAP on lung mechanics in infants with acquired tracheobronchomalacia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1341–1346. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis S, Jones M, Kisling J, Angelicchio C, Tepper RS. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on forced expiratory flows in infants with tracheomalacia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:148–152. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9711034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsia D, DiBlasi RM, Richardson P, Crotwell D, Debley J, Carter E. The effects of flexible bronchoscopy on mechanical ventilation in a pediatric lung model. Chest. 2009;135:33–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy J, Habib RH, Liptsen E, Singh R, Kahn D, Steele AM, et al. Prone versus supine positioning in the well preterm infant: effects on work of breathing and breathing patterns. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:754–758. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandit PB, Courtney SE, Pyon KH, Saslow JG, Habib RH. Work of breathing during constant- and variable-flow nasal continuous positive airway pressure in preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2001;108:682–685. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhutani VK, Sivieri EM, Abbasi S, Shaffer TH. Evaluation of neonatal pulmonary mechanics and energetics: a two factor least mean square analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1988;4:150–158. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950040306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Courtney SE, Aghai ZH, Saslow JG, Pyon KH, Habib RH. Changes in lung volume and work of breathing: a comparison of two variable-flow nasal continuous positive airway pressure devices in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:248–252. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okazaki J, Isono S, Hasegawa H, Sakai M, Nagase Y, Nishino T. Quantitative assessment of tracheal collapsibility in infants with tracheomalacia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:780–785. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1691OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko BS, Wong DTL, Nørgaard BL, Leong DP, Cameron JD, Gaur S, et al. Diagnostic performance of transluminal attenuation gradient and noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from 320-detector row CT angiography to diagnose hemodynamically significant coronary stenosis: an NXT substudy. Radiology. 2016;279:75–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2233–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.